History

As the 1980s drew to a close, Nintendo was at the top of its game, easily dominating both the console and the new handheld market thanks to its Game Boy. While the Game Boy easily fended off all comers, the NES was feeling its age. Nintendo was losing ground in both Japan and America to NEC’s PC Engine series and Sega’s Genesis, respectively. The company was naturally reluctant to threaten its well-established NES with a new, non-compatible console. However, when Nintendo finally struck with the Super Famicom on November 21, 1990, it never looked back: 8-bit was dead.

The Super Famicom was designed by master Famicom creator Masayuki Uemura, who was brought back from retirement to direct its creation. It was an instant success, selling out of its initial shipment of 300,000 units in just a few hours. The company had released it on a Wednesday evening, and tried other secretive measures to avoid unwanted attention from the Yakuza (a transnational organized crime syndicate).1 However, the public disturbance was so great that the Japanese government formally requested that all future videogame console releases take place on a weekend.2

The Super Famicom, or Super Nintendo Entertainment System (Super NES or SNES), as it would be known after its release in North America (August 23, 1991, retailing for $199.99) and Europe (April 11, 1992), gave Nintendo its first crack at updating its popular franchises, enhancing favorites such as Mario and Zelda for the “next generation.” In this regard, the Super NES delivered. These new games were more than just audiovisual facelifts of stale classics, however. They were indeed “Super,” as their titles suggested, taking full advantage of the new hardware to offer gamers a richer, more in-depth experience than ever before. More importantly, they allowed Nintendo to shift console sales momentum back in their favor.

A still from one of the earliest Super Nintendo commercials in 1991, showing a simple addition to the NES’s famous slogan, “Now you’re playing with power.” www.youtube.com/watch?v=BrI-A94aLfo

Super Mario World, which was the pack-in game for North American consoles, was a brilliant addition to the Mario platforming dynasty (and first introduction to new series favorite, Yoshi), and showed that producer Shigeru Miyamoto was just as good with 16-bits as he was with 8-bits. F-Zero was a genre-defining futuristic racing game that showed off the new system’s inherent scaling and rotation effects, much like casual flight simulator Pilotwings.

The software at the Japanese launch was anemic at best. Only Super Mario World and F-Zero were available to showcase the new hardware. Nintendo waited nearly a year to launch the system in North America, which allowed developers to add Pilotwings, SimCity, and Gradius III to the lineup.

Chrono Trigger on the ZSNES emulator.

Chrono Trigger (1995, Squaresoft)

Even against the NES and Sega Genesis before it, and the Sony PlayStation after it, it’s been argued that the Super NES featured the greatest selection of original role-playing games ever produced for a console. With releases like Chrono Trigger, it’s easy to see why. While Chrono Trigger tasks the player with controlling the usual group of adventurers through the standard types of forests, towns, and dungeons in an attempt to prevent an obviously world-shattering catastrophe, the game presents several interesting twists to the usual genre conventions. These twists include seamless enemy encounters that are visible on and take place on the same map used for exploration; time travel, where actions that occur in the past have an impact on future events; and not just one, but 13 unique endings. The game also further refines the “Active Time Battle” system first implemented in the 1991 classic Final Fantasy II (known as Final Fantasy IV in Japan), where the player has to input character orders in real-time during battles. Detailed, colorful graphics, and a masterful soundtrack round out Chrono Trigger’s appealing total package.

SimCity had been an absolute mega-hit on the PC, but it was unclear if the city-building game’s complex interface and gameplay mechanics would translate well to consoles. The resulting game could either make or break the platform’s reputation. Therefore, Nintendo took on the responsibility of porting the game itself. Although their port suffered from noticeable slow-down with large cities, it demonstrated that complex computer simulations were not major hurdles for the new console. The developers even added their own flourishes, including replacing the Godzilla-like monster from the original game with Bowser, Mario’s nemesis.

The only third-party title at the launch, Gradius III, was a competent, if somewhat mundane port of Konami’s own side-scrolling arcade space shooter. The lack of third-party support didn’t bode well for the system, particularly now that the company was facing stronger competition. It had also allowed many of its infamous exclusivity agreements with major publishers to expire. Nevertheless, third-party software support for the Super Nintendo quickly gained momentum. Some third parties continued to deal exclusively with Nintendo, obtaining both licenses and cartridges, but most others would simply purchase the required security chips and manufacture their own cartridges. This option left them free to support the Genesis and other systems. Of course, to get the required license and accompanying security chip, third parties still had to agree to produce at least three Super NES titles a year.3 It wasn’t a popular clause with publishers, but old habits die hard.

Technical Specifications

The Super NES featured a boxy grey exterior accented with purple and grey features. On the top of the console was a cartridge port with a noticeably different shape than its Japanese counterpart. This shape, combined with an internal lockout chip, means the North American Super Nintendo could only play cartridges made for its region without the use of special adapters. Below the cartridge port, from left to right, were a purple power button, grey eject button for removing cartridges after power off, and a reset switch.

Donkey Kong Country 2: Diddy’s Kong Quest on the ZSNES emulator.

Donkey Kong Country 2: Diddy’s Kong Quest (1995, Nintendo)

As sequels go, Donkey Kong Country 2: Diddy’s Kong Quest had one of the tougher acts to follow. No longer afforded the luxury of surprising gamers with the original game’s audiovisual “wow factor,” developer Rare succeeded by simply focusing on improving nearly every aspect of Donkey Kong Country’s already winning formula, from even better graphics fidelity to larger, more varied stages. One or two simultaneous players take on the role of Diddy, or his girlfriend Dixie, as they try to rescue Donkey Kong from Kaptain K. Kool through Crocodile Isle’s eight unique environments. Hidden bonus stages with collectible tokens add to the returning ability to “ride” various animal buddies with unique abilities, including Squitter the Spider, Glimmer the Anglerfish, and Squawks the Parrot. David Wise’s compositions, which were also released separately on CD, provide a fitting soundtrack to Diddy Kong’s continued adventures. The last sequel to appear on the Super NES was Donkey Kong Country 3: Dixie Kong’s Double Trouble! (1996), which, while combining some of the best elements from the first two games, had the unfortunate distinction of releasing shortly after the launch of the Nintendo 64, lessening some of its potential impact.

To the front of the console were two controller ports. Included with each Super Nintendo console were two eight button controllers with a color scheme that matched the console. Unlike the rectangular NES controllers, the Super NES controllers were rounded and slightly larger, which made them far more comfortable for extended use. From left to right on the front of each controller were a digital direction pad, select button, start button, and Y, X, B, and A action buttons. Left and right digital triggers were at the top of the controller.

Street Fighter II running on the ZSNES emulator. Although the controller didn’t have a traditional layout, its six action buttons in combination with the console’s quality graphics and sound made the Super NES one of the era’s best platforms for fighting games.

Although not in a traditional arcade layout, the fact that the Super Nintendo’s controllers supported six action buttons by default (counting the two shoulder triggers) made the system a natural for fighting game conversions. Combined with its impressive audiovisual capabilities, games like Street Fighter II (1992, Capcom), Super Street Fighter II: The New Challengers (1994, Capcom), Killer Instinct (1995, Rare), and Ultimate Mortal Kombat 3 (Midway, 1996), shined whether using the stock controller or dedicated arcade stick.

On the right rear of the console were, from left to right, a multi out, RF out and CH 3–CH 4 switch, and AC adapter input (DC 10V). The versatile multi out audiovideo output connector, which would also later be found on the Nintendo 64 (Chapter 3.3) and GameCube (Chapter 3.7), allowed for composite, S-Video, and RGB signals, as well as RF with an external RF modulator.

On the bottom of the console was an EXT expansion port, covered by a removable slot cover. Only two Japanese exclusives made use of this port: the Satellaview modem and an exercise bike. If the planned CD add-on ever saw release, it too would have made use of this port. Since it saw so little use, the expansion port, dedicated RF output, and related channel select switch weren’t included in the later Super Nintendo model, the SNS-101, released in 1997 at a budget-friendly $99.99 retail price.

The Super NES contains a custom Ricoh 5A22 CPU, which was based on the Western Design Center (WDC) 65816, which itself was the 16-bit successor to the 8-bit WDC 65C02 class of CPUs found in systems like the NEC TurboGrafx-16, Atari Lynx, and Apple IIe Enhanced/IIC+ (Chapter 1.2). The Rico 5A22 CPU ran at 3.58 MHz, faster than the 2.8 MHz from the similar CPU found in the Apple IIGS, which was often used as an early development system for the Super NES. While Nintendo’s choice of CPU and related clock speed was somewhat underwhelming in terms of raw performance, critics were impressed with the system’s ability to pass processing demands onto other parts of its architecture, like its video and audio subsystems.

The Picture Processing Unit (PPU) was made up of two IC packages that act as a single unit. The versatile PPU contained 64K of SRAM for storing video data, 544 bytes of Object Attribute Memory (OAM) for storing sprite data, and a 256 × 15-bit Color Generator RAM (CGRAM) for storing palette data. This translated to a common output resolution of 256 × 224 pixels, with up to 256 colors on-screen at one time from a palette of 32,768.

The system’s background layers were made up of 32 × 32 to 128 × 128 tiles on one of two foreground or background planes, with eight different color palettes. Each of these layers could be scrolled horizontally and vertically, allowing for some impressive effects. The Super NES featured eight such graphics modes, numbered 0–7, but the most famous was Mode 7. In this mode, one layer of 128 × 128 tiles from a set of 256 could be rotated and scaled using matrix transformations, with HDMA used to generate perspective effects. Put simply, background images could be rotated and scaled freely to simulate 3D environments without any performance hits to other processing activities. While the Atari Lynx and Sega CD had similar capabilities in hardware, it was the Super NES that made the most consistent and innovative use of the feature, defining the unique aesthetics of Super Mario World, Pilotwings, F-Zero, Super Mario Kart, and Kirby Super Star. The remarkable scaling and rotation effects in games like these made “Mode 7” one of the unlikeliest household phrases ever.

EarthBound on the ZSNES emulator.

EarthBound (1995, Nintendo)

Known in Japan as Mother 2 (1994), EarthBound was the first game released in the series in the US after Nintendo chose not to release the Famicom original Mother (1989), as Earth Bound in 1991 for the NES, despite being fully translated and ready to go. Luckily, bad timing didn’t affect the sequel’s release, and North American gamers were able to experience this unique, bizarre take on console role-playing. Ostensibly a parody of overused fantasy role-playing tropes, EarthBound also ruthlessly skewered American culture. The player is tasked with controlling 13-year-old Ness, who is gifted with psychic abilities, and other strange characters in the town of Onett, where one night a meteor landed, unleashing an evil alien named Giygas, who, of course, wants to take over the world. All activities take place from a single seamless 2D gameworld, including the turn-based battles. While poor sales meant no other sequels would be released outside of Japan, EarthBound is deserving of its cult classic status, well worth downloading on the Wii U’s eShop if a boxed original copy of this highly collectible game (complete with included player’s guide!) is out of your price range.

While the Super NES’s graphics capabilities deservedly received a lot of attention, the audio subsystem is arguably even more impressive sounding than its colorful PPU looked. An 8-bit Sony SPC700 and a 16-bit DSP shared 64KB of SRAM and a clock speed of 24.576 MHz. In combination, these two processors generated a 16-bit waveform at 32 kHz by mixing input from eight independent voices and an eight-tap FIR filter. Each of the eight voices could play its sound sample at a variable rate, with Gaussian interpolation, stereo panning, and ADSR, linear, non-linear, or direct volume envelope adjustment. All of these features combined to create some of the cleanest and richest sound output of its era, which could be further augmented by passing stereo audio data from a cartridge, expansion port, or both, before sending the combined output to a television or audio receiver.

Besides the memory found in its video and audio subsystems, the console itself used a separate 128KB of DRAM. As with all of its other features, the base memory of the system could be expanded with chips in game cartridges, an innovation Nintendo had leveraged in the NES. While the NES was known for its in-cartridge game enhancer chips, the Super NES took the concept to the next level.

Two of the most popular such cartridge add-ins were the DSP- and Super FX-series chips, although they certainly weren’t the only ones. The DSP chips were a series of fixed-point digital signal processor chips that allowed for fast vector-based calculations, bitmap conversion, 2D and 3D coordinate transformation, and other enhancements. These were often used as in-cartridge math co-processors to provide faster floating point and trigonometric calculations needed by 3D math algorithms in games like Pilotwings or Super Mario Kart.

The Super FX chips were a series of RISC CPUs primarily used for creating the type of 3D game worlds consisting of the types of polygons, texture mapping, and light source shading that the Super NES by itself could never hope to reproduce. In some cases, these chips also enhanced the elements of regular 2D games.

The first game to make use of the Super FX chip was the third-person space shooter Star Fox. Star Fox used scaling bitmaps for lasers, asteroids, and other obstacles, but the ships and other objects were rendered with hundreds of polygons, creating the game’s unique look. Other games that made use of the Super FX chip included racing games Stunt Race FX (1994, Nintendo) and Dirt Trax FX (1995, Acclaim), and 3D shooter, Vortex (1994, Electro Brain), which featured a transforming robot.

Star Fox, shown here running on the ZSNES emulator, was the first game to use the Super FX chip to render 3D polygonal graphics on the Super NES.

The Super FX 2, which was an enhancement of the original chip designed for larger games, was featured in three releases: Doom (1996, Williams), Super Mario World 2: Yoshi’s Island (1995, Nintendo), and Winter Gold (1996, Nintendo), the latter of which was a European exclusive. The chips helped make these games critically and commercially successful, but their high cost and late availability limited their impact.4

Doom, shown here running on the ZSNES emulator, was one of a handful of games to use the Super FX 2 chip. Although the game ran in a window and with a relatively low frame rate, its faithfulness to the PC original is still an impressive demonstration of the versatility of the Super NES’s architecture.

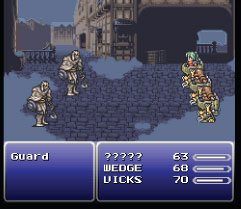

Final Fantasy III on the ZSNES emulator.

Final Fantasy III (1994, Squaresoft)

Released as Final Fantasy VI in Japan, it was the third game in the series released in the US, thus the confusing disparity in numbering that would take until 1997—and a completely different platform—to eventually sync up across all regions. Whatever it’s referred to as, the fact remains that this cartridge is considered not just among the greatest ever console role-playing games, but among the greatest ever console games period. While it put the usual industrial spin on classic fantasy elements that the series was already known for, Final Fantasy III featured a large cast of characters who have to deal with serious dramatic issues (e.g., teen pregnancy and suicide) as they develop over the course of the game. Final Fantasy III would be a triumph based on its scope alone—which even included a tragic opera—but it was also successfully married to extremely polished gameplay. The game’s greatness was such that it received several later ports that became classics in their own rights, including to the Game Boy Advance and Sony PlayStation, although, fittingly, little needed to be changed from the original.

The Super NES had nowhere near the volume of add-ons enjoyed by the Sega Genesis or the NES, but there were still fun accessories available. While the Super NES came with great controllers, there were a wide variety of third-party replacements, as well as Nintendo’s own Super Advantage arcade-style joystick with adjustable turbo settings.

The Super Nintendo also received an official bazooka-shaped light gun, the Super Scope. Only a dozen games were released with support for the light gun, including Super Scope 6, a bundled collection of mini-games, and T2: The Arcade Game (1995, LJN), a quality port of the popular arcade game.

Like the Genesis and NES before it, the Super NES also featured a variety of multitaps, including Hudson Soft’s Super Multitap, which featured four controller ports and came bundled with the hectic multiplayer classic Super Bomberman as the Super Bomberman Party Pak (1993). While up to two multitaps could be connected to the console, giving a theoretical limit of eight players, the maximum that was ever supported in an original retail game was five.

To the left is the Super Scope surrounded by a few of its games. The Super NES mouse sits next to the Super Game Boy cartridge. At the top right of the photo is the Victormaxx Stuntmaster virtual reality helmet, which was really nothing more than a low resolution LCD screen in a bulky headset.

In 1992, Nintendo released the Super NES Mouse in a bundle with a plastic mouse pad and Mario Paint, a clever drawing, animation, and music composition cartridge. While support wasn’t exactly universal, the Super NES Mouse faired far better than its Genesis counterpart, since it was usable with several dozen games, including obvious targets like strategy games Utopia: The Creation of a Nation (1993, Jaleco) and Sid Meier’s Civilization (1994, Koei), as well as role-playing games such as Might and Magic III: Isles of Terra (1995, FCI) and casino games such as Super Caesars Palace (1993, Virgin Games).

As mentioned in Chapter 2.4, while Nintendo never released a compatibility option for NES games for the Super Nintendo, they did release one for the original Game Boy. The Super Game Boy cartridge let all original Game Boy games (as well as black Game Boy Color cartridges and the Game Boy Camera in monochrome compatibility modes) run on a TV, mapping the four shades of green to various other colors. It also could display special graphical borders and other enhancements in games that provided special support for those features. Two games that showcased these extra features were Donkey Kong (1994, Nintendo), a wonderful fusion of the original arcade game and puzzle elements with more than 100 stages that added custom music and voice samples in addition to a colorful arcade machine border, and Kirby’s Dream Land 2 (1995, Nintendo), a platform game that came with a custom color scheme, special game border, and additional sound effects.

Secret of Mana on the ZSNES emulator.

Secret of Mana (1993, Squaresoft)

Thanks to the Super NES’s multitap accessory, up to three players can control the three protagonists, a warrior boy, a magic user girl, and an amnesiatic con artist orphan sprite in this innovative action role-playing game.5 While employing the traditional top-down perspective of other console role-playing games, Secret of Mana utilizes a real-time battle system and “Ring Command” menu system, which pauses the game and allows for a wide range of actions to be quickly performed without switching out from the main screen. The second or third players could drop out from the game at any time, where they would be immediately replaced by a customizable artificial intelligence, keeping the cooperative gameplay elements intact. The usual colorful Super NES graphics and excellent musical score from composer Hiroki Kikuta round out Secret of Mana’s compelling package.

Cartridges like the Pro Action Replay and Game Genie not only allowed in-game cheats, but could also be used for other useful functions like playing games intended for other regions. As is typical for add-ons like these, any Super Nintendo cartridges with special chips tend not to work.

Of course, arguably the most famous add-on for the Super NES was something that was never even released. Sony Engineer Ken Kutaragi had developed the SPC700 chip that helped power the Famicom’s audio subsystem, which led to Nintendo signing a deal in 1988 with Sony for development of a CD-ROM add-on and Sony-branded combination Super Famicom and CD-ROM console.

At the June 1991 Consumer Electronics Show, Sony unveiled the Play Station, which played both Super NES cartridges and new SNES-CD titles. Despite demonstrating a viable prototype, Nintendo corporate became uncomfortable with the idea of a Sony developed and controlled CD format, and instead announced an alliance with Philips to produce their own CD add-on the very next day. Despite a new deal being reached in 1992 where Sony could once again produce Super NES-compatible hardware, the damage from the surprise announcement was already done and the company instead focused its corporate might on a new console of its own, the PlayStation, described in Chapter 3.2.

The infamous Philips CD-i games and muted reception to its properties that appeared on PC and Macintosh computers probably contributed to Nintendo’s decision to end future sublicensing experiments.

Unfortunately for Nintendo, their partnership with Philips didn’t turn out any better. Philips released a handful of mostly mediocre (Hotel Mario) and infamous (Link: The Faces of Evil) games for their ill-fated CD-i multimedia platform,6 but never a CD add-on for the Super NES. Partnerships with computer software publishers, Interplay and Software Toolworks, to release DOS, Windows, and Macintosh Nintendo-themed edutainment and casual entertainment titles like Mario Teaches Typing (1992) and Mario’s Game Gallery (1995) produced similarly uninspired results.

With no CD-ROM add-on forthcoming, Nintendo instead doubled down on maximizing their console’s potential. Games like Rare’s Donkey Kong Country (1994), which made revolutionary use of pre-rendered 3D graphics from Silicon Graphics workstations, breathed new life into the Super Nintendo, helping the system remain competitive against a growing lineup of next generation consoles. Those same Silicon Graphics workstations would provide similar inspiration for and help bridge the gap to the release of Nintendo’s next console in 1996, the Nintendo 64, described in Chapter 3.3.

Ultimately, the Super NES sold close to 50 million units worldwide, almost 10 million more than the rival Genesis.7 The last Super Nintendo system rolled off the production line in 1999, while the last Super Famicom was September 2003, almost a full 13 years after its original Japanese launch.

Super Mario All-Stars on the ZSNES emulator.

Super Mario All-Stars (1993, Nintendo)

Once the decision was made during the Super NES’s development to give up on the idea of backwards-compatibility with its predecessor, it seemed that platforming fans without an NES would have to miss out on some truly legendary Super Mario Bros.-series games. Original Super NES pack-in Super Mario World was of course a brilliant new take on the legendary series, as was the later, Super Mario World 2: Yoshi’s Island, which, among its other distinctions were its unusual graphics that looked hand-drawn, but neither game really offered quite the same experience as the originals. That all changed in 1993 when Nintendo released Super Mario All-Stars, which contained audiovisually enhanced versions of Super Mario Bros., Super Mario Bros.: The Lost Levels (the Japanese Super Mario Bros. 2), Super Mario Bros. 2, and Super Mario Bros. 3. The games were lovingly presented behind an animated startup screen and menu system that gave the titles their proper historical due, which was further enhanced with the welcome addition of a modern save game feature. In 1994, the game package was made even better with a version of the cartridge that also contained Super Mario World and included as a pack-in game with new Super NES systems. No wonder the Super NES started catching up in sales to Sega’s Genesis! Fans with a Wii or Wii U would do well to check out Super Mario All-Stars: Limited Edition (2010), which was released to celebrate the 25th anniversary of Super Mario Bros. and is an authentic recreation of the Super NES original. While it’s missing Super Mario World, the package does include the addition of a nice soundtrack CD and history booklet.

The Nintendo Super NES Community Then and Now

Nintendo fans have never suffered a shortage of support. Nintendo’s own Nintendo Power magazine was just one among many publications that supplied fans with news about their favorite 16-bit system. Almost every site dedicated to classic gaming today has continued this support with discussion forums dedicated to the Super Nintendo, including Nintendo’s own website (http://nintendo.com).

While there have been only a handful of homebrew games released for the Super Nintendo to date, the list is growing all the time. One of the most high profile homebrew releases to date has been the Kickstarter-driven Super 4 in 1 Multicart, which was funded on May 5, 2013, and features puzzler Mazezam, platformer UWOL—Quest for Money, cooperative multiplayer platformer Skipp and Friends: Unexpected Journey, and the up-to-eight-player fighting game N-WARP Daisakusen, as well as fifth bonus action game, Balloon Attack. Another popular homebrew title that has gained some attention is Nightmare Busters (2013) from Super Fighter Team, an enhanced version of a previously unreleased game from Nichibutzu.

Super Mario Kart on the ZSNES emulator.

Super Mario Kart (1992, Nintendo)

Super Mario Kart’s release marked one of gaming’s rare defining moments. Not only was it the first time Nintendo truly leveraged the combined power of its roster of characters, becoming a staple feature in future Nintendo game franchises, it also single handedly established the subgenre of kart racing. Like many Nintendo originals, Super Mario Kart was released fully formed, incredibly polished and highly playable. From the balanced roster to the imaginative tracks and now iconic power-ups, right through to the competitive battle modes, there was little to criticize about the game. Bright cartoon-style visuals, split screen multiplayer, and well implemented Mode 7 graphics rounded out its complete package. Besides Super Mario Kart’s many excellent sequels on later Nintendo platforms, for more racing thrills, check out the earlier F-Zero (1990), a faster, futuristic racing game that also put Mode 7 to the test. For more kart racing action, be sure to check out Street Racer (1994, Ubisoft), which lacks Super Mario Kart’s personality, but makes up for it with fun competitive game modes, like Rumble, where you try to force your opponents from the arena, and Soccer, where you try to knock the ball into your opponent’s goal. Although ported to a number of other platforms over the years, the Super NES original is by far the best, even supporting four-player simultaneous split screen with a multitap!

Collecting Nintendo Super NES Systems

Super Nintendo systems and games are easy to find and inexpensive on online auction sites, although, as is usually the case, complete, boxed items hold considerably more value. Of Nintendo’s Super NES consoles, the SNS-101 version has somewhat limited appeal to collectors since its audio-video output is restricted to composite. However, once modified to restore the missing multi out functionality, the system’s appeal jumps considerably. The fact remains, however, that there are enough original Super Nintendo models available to make the purchase of an SNS-101 generally more trouble than it’s worth. Fortunately, the SNS-101’s companion controller only differs from the original cosmetically, with slightly darker buttons and different logo placement. Finally, like many older systems with light colored casings, it’s not uncommon for the grey plastic on Super NES items to become discolored over time with an unattractive yellow tint.

A large aftermarket of Super NES clone consoles and handhelds has sprung up, though these vary wildly in terms of quality and compatibility. Hyperkin’s SupaBoy is one of the more popular such options, letting you plug in both Super Nintendo and Super Famicom cartridges into the handheld’s top slot and play them on its built-in 3.5-inch color screen. In addition to working like a portable Super Nintendo, the SupaBoy’s two front facing controller ports let you plug in original controllers and play your games on the TV like a regular console.

Hyperkin’s SupaBoy is a versatile clone system that can work both as a handheld and console.

Several flash cartridges are available for the Super Nintendo and Super Famicom that let you play many of the platform’s games region-free on any compatible console. Two of the most popular such options are the SNES PowerPak from Retrozone, which works with compact flash cards, and Krikzz’s Super Everdrive, which works with SD cards.

A deluxe version of the Krikzz Super Everdrive from reseller Stone Age Gamer. Most NTSC and PAL games are directly supported, save for those requiring special chips.

Super Mario RPG: Legend of the Seven Stars (1996, Nintendo)

On a platform overflowing with legendary role-playing games, it’s only fitting that Mario and company would join in on the fun. A collaborative production between Square and Nintendo—led by Shigeru Miyamoto himself—this action role-playing game combines the story and game mechanics from the Super Mario Bros. games with conventions found in the likes of the Final Fantasy series. Players control Mario and a small group of teammates as they take on Smithy, who has stolen the seven star pieces of Star Road. Combat is turn-based, but has the innovation of correctly timed button presses that amplify an attack, special move, defense, or item usage. Filled with humor and lovingly rendered in an isometric perspective, Super Mario RPG was a fitting final appearance for Mario and Square on the Super NES. Because Square would not return to Nintendo platforms again until the 2002 Japanese release of puzzler, Chocobo Land: A Game of Dice, for the Game Boy Advance, Nintendo’s next Mario-themed RPG was more of a spiritual successor than a direct sequel—Paper Mario—which came out in 2001 in the US for the Nintendo 64.

The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past on the ZSNES emulator.

The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past (1992, Nintendo)

The third game in the series and a return to the original game’s top-down perspective, The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past proved once and for all that Nintendo would have no trouble bringing improved versions of non-Mario NES classics to its future generations of consoles. Players take the role of Link who must rescue Princess Zelda from an evil wizard who wants to unleash main series antagonist, the sorcerer Ganon. Under the direction of mentor Sahasrahla, players must guide Link between parallel Light (normal) and Dark (evil) versions of the land of Hyrule. With increased mobility, power-ups, new items to discover, and special attacks to unleash, A Link to the Past took all that was great about the first game and made it even more epic, setting the standard for the series to achieve ever greater heights going forward. This game was rereleased in 2002 for the Game Boy Advance as The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past & Four Swords, which added additional sound effects and a new multiplayer adventure that can interact with the main game.

Emulating the Nintendo Super NES

The Super Nintendo is one of the most popular platforms to emulate, with emulators available for nearly every type of capable computer, console, and handheld imaginable. Two of the most popular are Snes9x, which runs on an impressive range of platforms, and ZSNES, which runs on Linux, PC DOS and Windows, and Macintosh computers, and even has an unofficial port for modded Xboxes. Simple USB adapters can even let you use original controllers with these emulators.

Of course, the best official way to play great Super Nintendo classics is via Nintendo’s own Virtual Console service for the Wii, 3DS, and Wii U. A growing collection of games—some never released outside their home territories—make the Virtual Console the perfect destination for those wanting to check out Nintendo’s classics, Super Nintendo or otherwise.

Configuring options in the ZSNES emulator to run the original pack-in game, Super Mario World.

Zombies Ate My Neighbors

(1993, Konami)

Developed by Konami and LucasArts (back when its games didn’t always feature a Star Wars tie-in), Zombies Ate My Neighbors is a one- or two-player cooperative “run-’n’-gun” shooting game that can be seen as a precursor to modern-day classics like Dead Rising (2006, Capcom) for the Xbox 360. Unlike Dead Rising, however, Zombies Ate My Neighbors is overflowing with humor and horror movie satire, and is far less burdened with advancing the in-game plot. Players take the role of either Zeke or Julie, as the teenagers try to rescue their titular neighbors from all kinds of monsters through 55 levels of mayhem. Imaginative weapons like squirt guns and weed whackers join power-ups like secret potions and clown decoys to add to the gory fun. While there have been several sequels and offshoots of the core gameplay found in Zombies Ate My Neighbors, including its direct follow-up Ghoul Patrol (1994), none have managed to recapture the fun of the fondly remembered original.

1 David David, Game Over: How Nintendo Zapped an American Industry, Captured Your Dollars, and Enslaved Your Children, New York: Random House, 1993.

2 Steven L. Kent, The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World, Prima Publishing, 2001.

3 David Sheff, Game Over: How Nintendo Zapped an American Industry, Captured Your Dollars, and Enslaved Your Children, Random House, 1993.

4 One casualty was Star Fox 2, which, while completed and intended for a 1995 release, was shelved in favor of focusing on the Nintendo 64’s launch. Ironically, the Nintendo 64’s intended release date was missed by over a year, which would have provided an ample window for Star Fox 2 to succeed at retail.

5 Interestingly, Free Fall Associates’ 1989 release for the Commodore Amiga, Swords of Twilight, had a somewhat similar gameplay structure and simultaneous three-player mode. Only some rough edges and being limited to a platform where console-like role-playing games were not looked upon favorably kept this title from having wider influence. Why publisher Electronic Arts never bothered to port or rework the title for later use on console platforms like the Sega Genesis remains a mystery considering how well-regarded Secret of Mana later became.

6 One CD-i game from the partnership, Super Mario’s Wacky Worlds, developed in 1993, never saw release. While never quite finished, the game was shaping up to be a promising sequel to Super Mario World.