History

In 1989, Nintendo was at the height of its fortune and fame, enjoying a near monopolistic hold of the videogame console industry. As we saw in Chapter 2.1, the Nintendo Entertainment System had overcome the skepticism of American retailers still reeling from the Great Videogame Crash. With a combination of hit games, cheap technology, and effective (if controversial) licensing policies, Nintendo had not only resurrected the moribund industry, but greatly expanded it, defining an entirely new generation of gamers. Competing with this behemoth would take great technology, slick marketing, and a lot of patience.

With Nintendo’s dominance firmly established, Sega ramped up the hyperbole in ads for the Genesis, emphasizing its graphics and edgier games. To brand the platform, Sega used its now-familiar “Sega!” shout along with the 16-bit era’s most memorable marketing tagline: “Genesis does what Nintendon’t,” shown here in a multipage ad from the June/July 1990 premiere issue of Sega Visions.

Sega had two of these qualities.

While it doesn’t reach quite as far back as Nintendo’s humble nineteenth-century beginnings, Sega’s history is no less storied. Although best known for their Japanese operations, the company that would later become Sega was born among the beautiful palm trees and beaches of Honolulu, Hawaii. In 1940, just a year before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, American businessmen Martin Bromley (originally Martin Jerome Bromberg), his father Irving Bromberg, and James Humpert started Standard Games to provide jukeboxes, slot machines, mechanical peep shows, and other coin-operated amusements specifically to the United States military. Irving Bromberg had been in the “penny arcade” business since the early 1930s, peddling his wares along the West Coast. Bromley and Humpert had found employment with the US Navy shipyard at Honolulu, providing both with invaluable contacts and marketing opportunities, particularly for their slot machines.

A federal “moral” ban on interstate shipment of slot machines in 1950, however, caused a sharp drop in the number of such devices operating within the United States and its territories.1 As a result, in 1952 the company began importing machines into the fledgling post-war Japanese market under a new company name, Nihon Goraku Bussan, which marketed its products under the Service Games banner.

Disney’s Aladdin running on the Fusion emulator.

Disney’s Aladdin (1993, Sega)

It’s not easy to make a compelling platform game based on a movie license. In many cases, they amount to little more than re-skinned versions of games that were mediocre to begin with. Virgin Games USA, however, raised the bar, not once, but three times, with McDonald’s Mick & Mack as the Global Gladiators (1992), and 7UP soda’s Cool Spot (1993). Not only did David Perry and his team of developers rise to the challenge with these games, they created two of the best platformers of their generation. However, Virgin Games USA would outdo itself with the third game when it teamed up with Disney’s actual animators for Disney’s Aladdin. The well-tested game engine, experienced development team, and Disney’s genuine interest in actively participating in the game’s creation all came together to create a true-to-the-movie 16-bit platforming experience quite unlike any other. The musical compositions of composer Donald S. Griffin even helped push the Genesis’ sound hardware to new heights! If you like this game, check out some of the Genesis’ other classics from its long list of licensed platform games, including World of Illusion Starring Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck (1992), with compelling cooperative gameplay between the title characters, and Taz Mania (1992), whose unforgiving difficulty is tempered by its enchanting cartoon-quality graphics and sound.

New York native, David Rosen, stationed in Japan during the Korean War, found similar opportunities there. After finishing his United States Air Force service term in 1952, Rosen remained in Japan, where, in 1954, he started Rosen Enterprise, Inc., to sell Japanese art to the American market, as well as create hundreds of Photorama photo studios for Japanese identification cards. In 1957, as the Japanese leisure market grew, Rosen changed strategy and began importing American coin-operated electro-mechanical amusement machines, placing them at his Photorama and additional retail locations.

In 1964, Rosen and Nihon Goraku Bussan began serious discussions about a merger, with the former bringing distribution and the latter bringing manufacturing expertise to the table. In 1965, the two companies merged under Sega Enterprises Ltd., an amalgam of the best known brand name between them, Service Games. Rosen became CEO of the new company.

As described in Chapter 1.1, Sega’s history of arcade innovation began shortly after the merger with the Rosen-designed electro-mechanical breakthrough Periscope in 1966, followed by several other innovative arcade games. In 1969, Rosen sold the company to Gulf+Western, remaining as CEO of the Sega division. In 1972, Sega Enterprises became a subsidiary of Gulf+Western and went public. In 1982, Gulf+Western sold the US assets of Sega Enterprises to Bally Manufacturing Corporation. Hayao Nakayama—who headed Sega’s Japanese operations after they acquired his former company, Esco Boueki—became the new CEO. Rosen led the US subsidiary.

By the early 1980s, after successfully licensing and developing their arcade games for various home systems, Sega tried their hand at a console of their own: the SG-1000. Similar to the ColecoVision, the SG-1000 was released in Japan on July 15, 1983, the same day as Nintendo’s Famicom. The SG-1000, the restyled SG-1000 II, and its computer variant, the SC-3000, sold reasonably well in its target Asian, Australian, and European markets. However, the platform never threatened the staggering sales figures of Nintendo’s legendary console. Only in the arcades did Sega truly shine.

Shown are several variations of Sega’s SG-3000 computers from different regions. The SG-3000 computers and SC-1000 consoles gave Sega valuable experience that they further honed with the Master System before putting it all together with the Genesis.

In March 1984, Japanese conglomerate CSK Holdings Corporation, led by Rosen and Hayao Nakayama, bought Sega’s Japanese assets. The company was renamed Sega Enterprises Ltd., and was publicly traded on the Tokyo Stock Exchange. Rosen’s friend and CSK chairman, Isao Okawa, became chairman of Sega. Rosen chose to remain in the United States and would later set up Sega’s US operations.

On October 20, 1985, Sega released the SG-1000’s backwards-compatible successor, the Mark III, which featured improved graphics hardware and more RAM. A redesigned version of the Mark III, with a revamped cartridge port and additional sound chip, the Yamaha YM2413, was released in North America in June 1986 as the Master System. This enhanced version of the system was released back to Japan with mostly cosmetic differences in October 1987.

Even though Sega of America, led by Rosen,2 was established in 1986 in Los Angeles as a wholly owned subsidiary of Sega Corporation of Japan, it didn’t make breaking into the US videogame market any easier. Following Nintendo’s example of partnering with a toy company to help them break into the American market, Sega made its bed with Tonka, best known for their toy trucks. Unfortunately, the Tonka partnership was not particularly successful. Like Nintendo, Sega decided in 1989 they’d be better off alone.

The Sega Master System was packed with features and expansion options, but failed to make much of a dent against the Nintendo Entertainment System in worldwide sales.

While the Master System was technologically more sophisticated than the Nintendo Entertainment System, Nintendo hoarded the best third-party software with its questionable exclusivity agreements. Sega had to be content with battling Atari for whatever scraps were left.3 Sega’s relative failure with the Master System did, however, allow them to beat Nintendo to the next generation with a 16-bit successor, a luxury Nintendo couldn’t afford. For Nintendo, it just didn’t make sense to cannibalize a platform with over 90 percent market share in the US, not to mention an incoming portable requiring considerable corporate attention (see Chapter 2.4).4

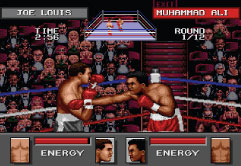

Greatest Heavyweights running on the Fusion emulator.

Greatest Heavyweights (1994, Sega)

Starting with their earliest arcade videogames in the 1970s, right through to the numerous creations into the 1990s for their home consoles, Sega has had a long love affair with the sport of boxing. Despite this storied history, it was only after refining the foundation of their 1992 hit, Evander Holyfield’s “Real Deal” Boxing, itself a port of an earlier computer game,5 that Sega properly returned the affection and captured the true essence of the sweet science. Greatest Heavyweights challenges players to create a boxer that can go toe-to-toe with 30 original boxers, as well as eight legends who act exactly as you’d expect them to in the ring. Michael Buffer announcing (“Let’s get ready to rumble!”), instant replays, and detailed punch stats all add to the incredible audiovisual presentation that’s almost as much fun for spectators as it is for players.

Released in Japan on October 29, 1988, where it was known as the Mega Drive, the Genesis wouldn’t see release in the US until August 14, 1989, with initial roll-outs restricted to the New York City and Los Angeles areas at a retail price of $189.99. NEC’s TurboGrafx-16 Entertainment SuperSystem, which had a similar initial roll-out period starting on August 19, 1989, retailed for $199.99. The Genesis would see wide release in North America one month later, on September 15, 1989. The 16-bit console generation was officially underway.

Although the TurboGrafx-16 could display more colors than the Sega Genesis thanks to its dual 16-bit graphics chipset, its overall design, complete with 8-bit microprocessor and two button controller, was meant to soundly beat the Nintendo Entertainment System, not go toe-to-toe with the Genesis, or, eventually, the Super NES. As a result, Sega pulled no punches when highlighting the TurboGrafx-16’s perceived deficiencies in its early advertising. NEC didn’t help the situation with its reluctance to export its best Japanese titles or its occasionally heavy-handed localization censorship when it did. As if all of these disadvantages weren’t enough, a series of controversial commercials—one with boiling goldfish, another with cats bouncing off the wall—aroused public indignation. As a result of all of this and lacking both Sega’s arcade catalog and still having to deal with Nintendo’s third-party exclusivity deals, it was difficult for NEC to compete effectively in the US with its paltry library. This despite incredible popularity in NEC’s home country, a territory where, along with Nintendo after the release of its Super Famicom (Super NES in North America) on November 21, 1990, it helped relegate the Genesis to a distant third place finish.

While the Genesis faced stiff competition in Japan from NEC, in North America and Europe it was top dog for several years before Nintendo’s Super NES finally began closing the gap a few years after its North American release on August 23, 1991. However, Nintendo’s plodding tortoise never did manage to overtake Sega’s hedgehog outside of Japan.

By 1993, even with the dominance of Nintendo’s Game Boy, Sega still commanded almost 40 percent of the US game industry, to Nintendo’s 51 percent.6 Worldwide, with dominance in other territories, like Europe and South America, those figures tilted even more in Sega’s favor, at close to 50 percent market share.7 In fact, despite the release of several newer and more powerful competing consoles along the way, Sega continued to sell its aging Genesis technology for several more years, despite muted responses to the Sega CD and 32X add-ons meant to extend the core console’s commercial relevance. It took several years past the late 1994 Japanese releases of Sega’s own Saturn and, critically, Sony’s PlayStation (see Chapter 3.2), before the market truly embraced a new generation of systems.

Technical Specifications and Models

Sega had enjoyed terrific success in the arcade, so that was an obvious source to go to for inspiration when developing the Genesis. While the Genesis was built on the foundations of its home predecessors, making sure the new console could match their Sega System 16 arcade technology positioned it well for the long haul. Worldwide arcade hits powered by the technology, like Action Fighter (1986), Alex Kidd: The Lost Stars (1986), Fantasy Zone (1986), Alien Syndrome (1987), Shinobi (1987), Altered Beast (1988), Wonder Boy III: Monster Lair (1988), E-Swat (1989), and Golden Axe (1989) meant there would be no shortage of games to bring over or draw inspiration from as the Genesis grew its own library of originals.

The Genesis is powered by a Motorola 68000 16-bit microprocessor running at 7.67 MHz, but also features an 8-bit Zilog Z80 as a secondary microprocessor running at 3.58 MHz. This secondary microprocessor also gives it backwards compatibility with the Master System through the use of a simple cartridge slot adapter.

The 68000 can access its own 64K of RAM, 64K of dedicated video memory, and 8K of work RAM from the Z80. The video is powered by a Yamaha YM7101 Video Display Processor (VDP), a descendent of the VDP found in the Master System, and, in its most common display modes, allows for 64 onscreen colors from a palette of 512 colors at typical resolutions of 320 × 224 or 256 × 224.

Sound on the Genesis is powered by one of two sound chips, controllable from either of its microprocessors. The first, a Yamaha YM2612 FM synthesizer chip, uses six FM channels with four operators each and runs at the same clock speed as the Motorola 68000. The second, the Texas Instruments SN76489 PSG chip, contains three square wave tone generators and one white noise generator, each of which can produce sounds at various frequencies and 16 different volume levels. Stereo sound is output through the headphone jack on model one Genesis systems, while model two Genesis systems eliminated the headphone jack and sent its stereo output through the AV out.

The front of the console features two nine-pin controller connectors, which are the same standard found on a wide variety of previous systems, including the Master System, Commodore Amiga, ColecoVision, and Atari 2600. The original Genesis controller features rounded corners, a digital directional pad, a start button (often used for pausing the action), and three action buttons: A, B, and C. To support newer games like Capcom’s Street Fighter II: Special Champion Edition, Sega released a slightly smaller six button controller in late 1993, which could be made to act like a three-button controller for better compatibility with some finicky older games.

Gunstar Heroes running on the Fusion emulator.

Gunstar Heroes (1993, Sega)

If there was any one game other than Sonic the Hedgehog that helped define the Genesis’ reputation as the system with “speed and attitude,” it was Gunstar Heroes. The perfect embodiment of the “run ’n’ gun” platforming genre, Gunstar Heroes let one or two players use 14 different weapon combinations to blast non-stop through its many action-packed, side-scrolling levels, which culminated in epic boss battles. Developer Treasure’s masterful programming allowed them to produce a large number of fast moving on-screen objects, creating an audiovisual experience unique to the platform. For more “run ’n’ gun” fun, be sure to check out Contra: Hard Corps (1994, Konami).

Besides the aforementioned headphone jack and accompanying dedicated volume slider, the top of the original console features an on/off switch and reset button. To the rear of the console is an expansion port (EXT) that was only used for the Japanese-exclusive Meganet modem add-on, as well as a channel select switch, RF out, DIN connector for composite and RGB video and audio, and the power connector. To the side was an expansion input port, somewhat similar to that found on the ColecoVision, and was what the CD add-on would later plug into. A later version of this console model added a regional lockout chip and an accompanying license screen that would appear for a few seconds before a game started. A still later version made cosmetic changes to the console’s exterior, removing the HIGH-DEFINITION GRAPHICS text, and eliminating the disused EXT port.

The first major revision to the Genesis came in 1994. Casually known as the “model two,” both the internal and exterior design were streamlined, requiring a new power supply and audio-video connectors. Gone were the headphone jack, channel select switch, and dedicated RF out.

The second and final revision came in 1998, with the Genesis 3, whose production was outsourced to Majesco. The internal and exterior design were once again streamlined, making the console even smaller, but also eliminating the expansion input port, which meant no support for the CD add-on. As with its lack of support for the 32X add-on, this was considered an acceptable loss as the only new product Majesco was producing for their budget system anyway was Genesis cartridges.8

Similarities to the Commodore Amiga’s architecture encouraged numerous ports between the two platforms, with popular computer games from top developers and publishers like Psygnosis, Accolade, and Electronic Arts helping fill out the early Genesis game library. Unfortunately, Sega’s later addition of its TradeMark Security System (TMSS) regional lockout chip on its consoles rendered several of the early such games unplayable without workarounds. Accolade decided to reverse engineer Sega’s copyrighted game code, a risky move that soon landed them in court with the console-maker. As Accolade’s Alan Miller put it in Steven Kent’s 2001 book The Legal Game, “One pays them between $10 and $15 per cartridge on top of the real hardware manufacturing costs, so it about doubles the cost of goods to the independent publisher.” These fees were in addition to Sega’s much-loathed exclusivity deal, which they’d formed along the same lines as Nintendo. The Ninth Circuit ruled that Accolade’s use of reverse engineering to publish Genesis titles was protected under fair use, and that its alleged violation of Sega trademarks was the fault of Sega. The case is still frequently cited in matters involving reverse engineering and fair use under copyright law. Nevertheless, after many years of litigation, both companies settled on April 30, 1993, with Accolade finally becoming an official licensee.

Even without the onus of legal action, eventually most Sega developers became official licensees and released their games without compatibility concerns. Electronic Arts, for instance, wanted a reduction in Sega’s fees, so they used their early unlicensed titles as leverage in negotiations, no doubt making use of the potential added threat of being able to share their reverse engineering technology with other companies. Whatever the details, it’s safe to say that when Electronic Arts became an official licensee, the success of both companies in the 16-bit era was assured.

Electronic Arts was able to bring its expertise from its prolific, but not so profitable, 16-bit computer releases to full fruition on the Genesis. Of its many classics, like Abrams Battle Tank (1988), Battle Squadron (1989), James Pond: Underwater Agent (1990), Road Rash (1991), Crüe Ball (1992), Haunting Starring Polterguy (1993), and General Chaos (1994), Electronic Arts proved most clever when plugging into the American love of sports. Only hinted at with popular NES games like Tecmo Bowl (1989, Tecmo) and Baseball Simulator 1.000 (1989, Culture Brain), Electronic Arts tapped into the collective competitive spirit of armchair sports fans like no other company before it. Not only did games like Lakers vs. Celtics and the NBA Playoffs (1989), John Madden Football (1990), PGA Tour Golf (1990), NHL Hockey (1991), and FIFA International Soccer (1993) kick off popular franchises that continue to this day, but Electronic Arts made gamers come to expect nothing less than real teams and players, forever changing the way such games were made. It didn’t hurt, of course, that this expectation also meant that each of these games could be released annually with only minor improvements and updated rosters to consistently blockbuster sales.

Even though the Genesis’ graphics and sound specifications were superior to most computers of the day, Sega’s system would have more competition in those areas on the console side. The TurboGrafx-16 featured superior color processing, with up to 481 on-screen colors from a pallet of 512, and Nintendo’s NES successor would feature both superior colors and sound (see Chapter 2.5). While its competitor’s advantages were not always clear, particularly in regards to the Super NES’s comparative sound clarity, it could be an obvious differentiator on multiplat-form titles.

While the Genesis could demonstrate few clear technical advantages over its console rivals, it did boast a faster processor, which was put to good use in the blockbuster Sonic the Hedgehog (1991) and its numerous sequels. Even though “blast processing” was as much marketing hyperbole as the words “HIGH DEFINITION GRAPHICS” plastered above the original console’s cartridge port, Sonic the Hedgehog did indeed represent a shot of adrenaline to an incredibly crowded, increasingly stale genre.9 While most platform games encouraged careful exploration and pixel-perfect timing, Sonic the Hedgehog reveled in its speed and spin dashes. While a skilled player might still want to explore every stage’s nooks and crannies, Sonic’s ability to rush full bore through levels laden with springs, slopes, high drops, tunnels, and loop-the-loops was irresistible. Ultimately, while the Super NES may have had better graphics and sound, the Genesis’ swifter processor still had it well positioned for success well into the “Go-Go 90s.”

Lunar: Eternal Blue running on the Fusion emulator.

Lunar: Eternal Blue (1995, Working Designs)

Lunar: Eternal Blue, the sequel to the superb Lunar: The Silver Star (1993), was one of the most ambitious of the RPGs available on a platform known for its strong selection of such games. As was their standard, Working Designs translated and improved upon the Japanese original for its North American release. While the gameplay, which involved stopping a great evil that threatens all of creation, falls into the usual Japanese RPG conventions of preset characters, linear gameplay, and random battles, the advantages in scope afforded by the Sega CD hardware are extraordinary. With more than 50 minutes of movie content and over an hour of spoken dialog from its 15 voice actors, Lunar: Eternal Blue is as technologically epic as its ultimate mission. A clever save system, which requires magic experience points equal to a multiple of the main character’s level, adds to the challenge. For a more atypical RPG experience, be sure to check out Core Design’s Heimdall (1994, JVC), which is steeped in Norse mythology and offers an unusual interface and isometric perspective.

Besides its sports games and the in-your-face attitude of its mascot cementing the Genesis’ status as the “cool” system to own, Sega’s more lenient censorship policy was also key to the console’s popularity. Nintendo had long lauded its “family friendly” nature, scrubbing out even the subtlest references to sex and gore in their American games. While such policies may have been a hit with concerned parents, older kids (and, increasingly, adult console gamers) were ready for something more mature—and Sega was ready to deliver. Perhaps no two games made that statement more clearly than Night Trap and Mortal Kombat.

Night Trap was a 1992 release for the Sega CD from Digital Pictures, published by Sega. A type of survival horror adventure game, full motion video clips are used to tell the story of a group of young women having a sleepover at a seemingly normal house for the night. The player takes control of security cameras in cooperation with an embedded undercover agent as a plot involving vampire-like creatures unfolds. Although not a particularly great game, its voyeuristic nature and scantily clad house guests caused a furor in the mass media. Ill-informed hosts (who’d likely never played or even seen the game) launched into tirade after tirade, all in a tireless effort to whip up moral indignation at an “out of control” videogame industry.

Mutant League Football running on the Fusion emulator.

Mutant League Football (1993, Electronic Arts)

Once the Madden series started tackling the sales charts, most other sports games responded in kind, licensing both league and player names in an attempt to create the best digital representation of reality. Nevertheless, even in the face of this overwhelming competitive peer pressure, a few games here and there were still able to challenge convention by putting fun before fidelity. Ironically, one of the best such titles, Mutant League Football, came from the very same company responsible for the creatively limiting expectation of reality in the first place. Mutant League Football (1993), based on the solid John Madden Football ’93 (1992) game engine, features teams of aliens, monsters, and other creatures playing on fields filled with landmines, pits, and other hazards. Crazy power-ups and tricks like jet packs, exploding balls, and bribable referees who need to be killed to stop their onslaught of dirty calls, all add up to one comically mean game of football. For more monster-mashing fun, check out Mutant League Hockey (1994), although unfortunately the game puts a few too many demands on the otherwise superlative NHL ’94 (1993) game engine, resulting in choppier gameplay.10 Sadly, development on a third game in the series, Mutant League Basketball—likely based on the NBA Live 95 (1994) game engine—was never completed, as publishing efforts shifted away from the Genesis to the next generation of platforms.11

Mortal Kombat was a 1992 arcade fighting game from Midway infamous for its blood and gore. Of particular note were its “fatalities,” grotesque finishing moves such as Sub-Zero’s “Spine Rip,” with which skilled players could graphically execute their opponents. Naturally, the game was a huge hit with teens and pre-teens, who quickly learned and memorized all of these moves. For “Mortal Monday,” on September 13, 1993, Acclaim Entertainment released home ports for the Sega Genesis and Game Gear, as well as the Super NES and Game Boy. While the versions for Nintendo’s systems were severely censored, replacing blood with sweat, and simply removing many of the gorier fatalities, the versions for Sega’s systems were left mostly intact—particularly after a simple “cheat code” was entered. Although arguably better-looking and more faithful gameplay-wise, the Super NES version sold far fewer copies, causing Nintendo to lighten up a bit on its censorship policy for future releases.

What really earned Night Trap and Mortal Kombat their place in the history books were the infamous 1993 US Senate hearings on videogame violence, which caused the former game to be pulled from the market for a time (helping its initial run to sell out in the process), and the latter game’s fatalities making regular appearances on the nightly news. In response, Sega formed the Videogame Rating Council (VRC) to voluntarily rate its own games. In September 1994, Sega’s efforts and those of other companies were combined into an industry standard ratings system under the Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB), still in use today.

Besides Sega’s more progressive stance on censorship, the Genesis differed in other ways from Nintendo’s approach with the Super NES. Going back to the NES days, Nintendo would make sure they put out a competent core console, but leave it open to enhancements on a game-by-game basis with the inclusion of special in-cartridge chips. Sega, on the other hand, focused primarily on add-ons with new capabilities, but they did try a short-lived experiment with the Sega Virtua Processor. While the chip was more capable than Nintendo’s vaunted Super FX, it was simply not cost effective. It did, however, do an impressive job bringing Sega’s own Virtua Racing arcade game home in 1997—maintaining much of its 3D glory. With Virtua Racing’s original retail price set at $100, it proved the first and last usage of the chip, with future 3D-centric games set for the 32X add-on.

Virtua Racing, shown here on the Fusion emulator, was an impressive first use of Sega’s Virtua Processor, but the add-in’s high cost meant the chip had no future.

The Add-Ons and Accessories

Continuing the tradition of predecessors from the likes of Nintendo, Coleco, Mattel, and Atari, the Genesis features an impressive range of add-ons and accessories. One such early Genesis add-on was the Power Base Converter, which allowed it to run nearly all of the Master System’s 300+ game cartridges and game cards. Master System controllers and even the platform’s famous SegaScope 3D glasses worked just like they should with the converter.

The Menacer, released in 1992, was Sega’s take on the light gun, similar to Nintendo’s Super Scope for the Super NES. The Menacer’s three sections can be dissembled for use in various configurations, including as its original bazooka-like design and a pistol. While only a little more than a half dozen games were released for The Menacer, it worked particularly well with popular full motion video shooting games for the Sega CD from American Laser Games like Mad Dog McCree (1993) and Who Shot Johnny Rock? (1994). Other games, like Lethal Enforcers (1993, Konami) came with their own, incompatible light guns.

An original Sega Genesis sporting the Power Base Converter.

While the Genesis only sported two controller ports, Sega, with their Team Player, and Electronic Arts, with their 4 Way Play, let up to four players play together in supported games. Codemasters went one step further and created games with their J-Cart system, which put two extra joystick ports right on the cartridge.

Besides the usual cheat cartridges like the Game Genie and Pro Action Replay, which had pass-through ports to allow other cartridges to connect to them, Sega developed a similar concept of its own, known as Lock-On Technology. Used in Sonic & Knuckles (1994), any of the three prior Sonic the Hedgehog games can be inserted to change the way each of the various titles play.

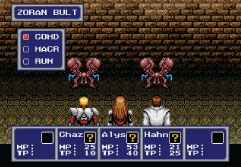

Phantasy Star IV running on the Fusion emulator.

Phantasy Star IV (1995, Sega)

As the Phantasy Star IV cartridge proved, epic RPGs were not the sole domain of the Sega CD. Continuing the fine tradition started way back on the Sega Master System with one of the largest console games of its time, Phantasy Star (1988), the final game in the original series, staked a similar claim on the Genesis, complete with matching price tag. While Phantasy Star IV concluded the ongoing storyline from the previous two games (Phantasy Star III: Generations of Doom featured a separate continuity) and played in a similar manner (just with more of everything), the series finale was also far less linear than its predecessors, with numerous side quests, and definitive moments of genuine pathos. Cover art by famed fantasy artist Boris Vallejo was the proverbial cherry on top for one of the finest 16-bit RPGs ever crafted. For a similarly themed, but more action-oriented science fiction fantasy role playing title, be sure to also check out BlueSky Software’s Shadowrun (1994, Sega), based on the famous pen-and-paper game from FASA.

One of the more unusual Genesis add-ons was the Sega Activator, which was an octagonal controller placed on the floor. After a player stepped in the ring and a body part, like an arm or leg, was detected by one the Activator’s infrared beams, it would translate to an in-game movement. Unfortunately, despite Sega promoting fighting games like its own Eternal Champions (1993) as an ideal companion for the contraption, no games were ever exclusively designed for the device.

Although NEC got to market first with their CD add-on (April 1988 in Japan, August 1990 in the US), it was Sega who would once again garner the most interest. The Sega CD, known as the Mega CD for its December 1991 release in Japan, wouldn’t be released in North America until October 1992. The first model, designed to match the styling of the original Genesis, sat under the console and featured a front loading, motorized disc tray. The second model, designed to match the styling of the model two Genesis, sat to the side and featured a manual top-loading disc tray.

Sega’s black Mega Mouse sits in front of Sega’s oversized, but modular Menacer light gun, as Konami’s light blue The Justifier light gun rests on the box for Sega’s Activator.

While the Sega CD featured the addition of a faster processor, more colors, and more RAM than the Genesis, the most typical use for the add-on was simply running larger games with full motion video. 64K memory was allocated for backup and save game data, but an optional CD Back Up RAM Cart could increase available storage to 1MB.

Several top computer adventure games from Sierra and LucasArts were successfully ported, and the occasional stand-out title, like Sonic CD (1993) and most of the role-playing games that were released, made the add-on tempting, but only approximately 6 million CD add-ons were sold worldwide. This low number was thanks in part to a large portion of the CD game library not offering much value over their cartridge-based counterparts, like the Sega CD version of the underwater action adventure classic Ecco the Dolphin (1993). This “new” version of the game merely featured a few additional levels and an enhanced soundtrack, hardly justifying the extra cost.

Pioneer released the LaserActive laserdisc player in the US in September 1993, at a retail price of close to $1000. Besides playing laserdisc videos, it could accept modules that added various new features, including the Sega PAC, which let it play existing Sega Genesis and CD games, as well as special laserdisc games that overlaid Genesis graphics on top of laserdisc video. Unfortunately, like the NEC PAC, which did the same for TurboGrafx-16 software, the price of the add-on was an additional $600 on top of the already sky high price of entry.

In 1994, JVC released the X’Eye in North America, which was a full-sized all-in-one officially licensed combination of the Genesis and Sega CD with improved audio and built-in karaoke capabilities. Unfortunately, it was priced higher than buying a Sega Genesis and Sega CD individually and offered few tangible gaming benefits.

Shining Force II running on the Fusion emulator.

Shining Force II (1994, Sega)

With the rising popularity of RPGs on consoles—and the associated glut of releases—it was no surprise that developers started to experiment with interesting variations on the genre. One of the best such hybrids was Shining Force II, which combined traditional RPG exploration with strategic, cinematic battle sequences. The player assumes the role of Shining Force leader, Bowie, as he leads a 12-member strike force from a selection of over 20 characters in an attempt to stop a great evil. While the bright graphics and cartoon styling may be a turn-off for some, the incredibly polished tactical gameplay is well worth overlooking any issues with Shining Force II’s aesthetics. Unfortunately, the next game in the series, Shining Force III for the ill-fated Sega Saturn, wouldn’t appear until 1998 in North America, with only the first of the three self-contained scenarios releasing outside of Japan.

Sega itself attempted to make its CD add-on more appealing for consumers in 1994 by releasing the CDX, a small combination Genesis and Sega CD that also doubled as a portable CD player. It was impressive technology, but consumers balked at the $399.99 retail price.

Also in 1994, Sega released the Mega Mouse, which was meant to make controlling supported adventure and role-playing games easier, as well make creativity programs practical. Little more than a dozen cartridge and CD programs were compatible with the mouse controller.

A Sega Genesis with its CD attachment and 32X was the proverbial elephant in the room. Shown here are the second models of the Genesis and Sega CD connected together. The extender to the left of the console is removable and allows the original, longer model of the Sega Genesis to rest comfortably next to the Sega CD.

Not content with the already dizzying array of options for the Genesis, Sega chose to develop and release the 32X, which was designed to add sophisticated 3D capabilities to the console and provide consumers a low-cost bridge to the forthcoming Saturn. Not only did the 32X contain a VDP capable of pushing 50,000 polygons per second and producing 32,768 onscreen colors, but it also contained two 32-bit RISC processors that could work up to 40 times faster than the Genesis alone, as well as additional memory and pulse-width modulation sound source.

The 32X looked great on paper, but, as with the Sega CD—which it also supported—only a handful of software took advantage of its greater capabilities. With the short window between the release of the 32X and the next generation of consoles, it’s not particularly surprising the add-on failed to gain traction. The planned release for a combination Sega Genesis and 32X called the Neptune was canceled.

Virtua Fighter on the 32X, shown here running on the Fusion emulator, was one of just a handful of games to take good advantage of the 32X’s enhancements.

On October 13, 1995, Sega took one last leap of faith with its Genesis technology and released the handheld Nomad system. Since it was region-free, the Nomad could play most both Genesis and Mega Drive cartridges on its 3.25-inch color LCD screen. Featuring six full action buttons and a port for a second controller, the Nomad’s video could also be output to a television, making it a proper portable console. Unfortunately, the unit’s bulky size, approximately two-hour battery life, and relatively high $180 retail price doomed it to failure, eventually selling just 1 million units worldwide.

Streets of Rage 2 running on the Fusion emulator.

Streets of Rage 2 (1992, Sega)

At the time, side-scrolling beat-’em-ups were second only to side-scrolling platforming games in their ubiquity on the era’s consoles, which made standing out a difficult proposition. Sega’s Streets of Rage 2 was one of the few such games that did exactly that, however, improving on its already excellent predecessor with more of everything that made the original so great. More moves, more weapons to pick up, more appropriate special attacks, more enemies, and more levels made the sequel a definitive release on the Genesis. Even the soundtrack was a stand-out, with memorable club-style music from the legendary Yuzo Koshiro, with additional contributions from Motohiro Kawashima. Though its relatively late release dulled some of its impact, the final game in the series,12 Streets of Rage 3 (1994), also proved a superior beat-’em-up.

Despite executing so well with the Sega Genesis, and in contrast to the relatively conservative Nintendo, it was clear Sega’s missteps with its various add-ons proved costly. After fumbling both the launch and early support for the Sega Saturn, Sega would only start to get back its mojo with the release of the Dreamcast. As detailed in Chapter 3.4, even the mighty Dreamcast proved too little to erase enough of Sega’s past ambitious missteps to save the company’s financial fortunes.

The Sega Genesis Community Then and Now

Thanks to its strong arcade roots, the Sega brand was always defined by great games. Of its home platforms, the most successful was easily the Sega Genesis, despite the lack of similar success with its Sega CD and 32X add-ons. That combination of great Sega games married to a great Sega platform was a difficult combination for the company to replicate, even though the Saturn and Dreamcast (Chapter 3.4) have more than their fair share of fans. As a result, it’s easy to find great places online to meet Sega Genesis and Mega Drive enthusiasts, and there’s no shortage of old and new product available to get your 16-bit fix. Some of the better Sega-specific websites include www.sega-16.com and Sega’s own forums at www.sega.com.

While new licensed games continued to be released into the 2000s in Brazil, for the most part, by the late 1990s, the best chance at getting new Sega Genesis games came from the homebrew community. The most popular such creations have been English translations from Super Fighter Team of various role-playing games released exclusively in Asian territories in the mid- to late-1990s, including Beggar Prince (2006), Legend of Wukong (2008), and Star Odyssey (2011). WaterMelon Co. went one step further with an original role-playing game creation in 2010, Pier Solar and the Great Architects.13 All of these releases quickly sold out of multiple runs, numbering between 300 and 1500 copies, which speaks to the continued popularity of the platform, since the usual maximum for homebrew creations on most other systems is generally between 50 and 250 copies.

Left: The original incredible Pier Solar and the Great Architects homebrew package from Watermelo Co., whose included Sega CD works in conjunction with the cartridge to provide extra audio content. Right: Super Fighter Team’s western release of Star Odyssey, also shown running below on a Sega Nomad with replacement LCD screen.

Collecting Sega Genesis Systems

Because of the number of Sega Genesis consoles and compatibles sold, finding an original system is relatively easy and inexpensive. The more fragile nature of the CD add-ons makes them harder to find in good working condition. The all-in-one Sega CDX and particularly the JVC X’Eye, are easily the most sought after systems for collectors.

The Amazing Spider-Man vs. the Kingpin running on the Fusion emulator.

The Amazing Spider-Man vs. the Kingpin (1993, Sega)

This enhanced Sega CD version of the 1991 Genesis original is considered one of the best Spider-Man games of all time, and with good reason. As the titular hero, the player is tasked with battling classic villains like Sandman and Hobgoblin in an attempt to obtain the keys needed to disarm a nuclear bomb Kingpin has framed Spider-Man for stealing, and will detonate within 24 hours. The perfectly tuned side-scrolling platforming action of the original blockbuster is enhanced by the Sega CD version’s additions, which included animated cutscenes, extra levels and moves, an original musical score, and less linear gameplay. For even more web-slinging fun, check out The Amazing Spider-Man: Web of Fire (1996) on the 32X. While not a particularly distinguished game for Sega’s underutilized add-on, its rarity makes it a great collectible.

For portable fun, many Sega Genesis cartridge enthusiasts enjoy the Sega Nomad. A popular upgrade for the Nomad is replacing its LCD screen with a modern panel, which eliminates most of the motion blur found on the original.

A range of flash cartridges are available, including two popular options from Krikzz, the Everdrive MD v3 and Mega Everdrive. With these cartridges, it’s simply a matter of placing game images on an SD card and then inserting it into a Genesis or clone, giving you the ability to play most of the games in the Genesis/Mega Drive, 32X, and Master System library.

ToeJam & Earl running on the Fusion emulator.

ToeJam & Earl (1991, Sega)

It’s not surprising that a game as original as ToeJam & Earl had an earlier inspiration. What is surprising is the game that did the inspiring for developer Johnson Voorsanger Productions was Rogue. The legendary 1980 dungeon crawling computer role playing game with text-based graphics is probably the last title you’d think of when first playing ToeJam & Earl, but the inspiration is clear once you consider both games’ random levels and item drops. Whatever its derivation, there’s no denying that ToeJam & Earl is unique, tasking players with getting the titular funky aliens off Earth by collecting the pieces of their crashed spacecraft against a backdrop of comedic pop culture references and urban culture parodies. While a single player can take control of either alien, ToeJam & Earl excels in its two-player cooperative mode, which features additional character interactions and a dynamic split screen when players get too far apart. Like the first sequels to Nintendo’s Super Mario Bros. (in the US) and The Legend of Zelda, the sequel to ToeJam & Earl—ToeJam & Earl in Panic on Funkotron (1993)—radically deviated from the original’s formula at the behest of publisher Sega, resulting in a decent, but ultimately uninspiring side-scrolling platform game. A final sequel, ToeJam & Earl III: Mission to Earth, was originally intended for the Sega Dreamcast, but was later released only for the Microsoft Xbox in 2002. Despite switching to a third-person, 3D perspective and adding a third playable character, it was truer to the original, but still failed to capture the same magic.

Thanks to its popularity and well understood architecture, there are a wide variety of emulators available for the Sega Genesis platform on nearly every capable system. Perhaps the most popular and versatile is Fusion for Windows-, Macintosh-, and Linux-based computers, which places emphasis on the accuracy of its emulation. In addition to emulating the Sega Genesis/Mega Drive, Fusion also emulates the Sega CD/Mega CD, 32X, Game Gear, Master System, and SG-1000/SC-3000.

Sonic the Hedgehog running on the Fusion emulator.

Today, Sega’s Genesis library has among the best officially licensed distribution among classic console games. You can find official Genesis game collections from Sega on everything from PC and console optical media and download services to Android and iOS smartphones and tablets. This distribution extends to dedicated systems, as well, such as AtGames’ Sega Arcade Classic console, which, in addition to its built-in games, accepts real cartridges, and their Sega Arcade Ultimate Portable handheld, which, in addition to its own set of built-in games, accepts an SD card that a user can load with their own game ROMs. In short, the Sega Genesis is by far the most accessible of the classic consoles to legally experience today.

1 “US Ban Cuts Operation of Slot Machines,” Sarasota Herald-Tribune, November 3, 1952.

2 Rosen would retire at age 66 from his storied career at Sega in 1996, with his final position as a director for both Sega’s Japanese and US operations.

3 Although a comparatively small market at the time, Sega achieved its greatest success with the Master System in Europe, where it was the top selling console for a number of years. One reason for Sega’s success was that Nintendo’s exclusivity agreements did not extend to that territory, creating a more level playing field.

4 www.stanford.edu/group/htgg/cgi-bin/drupal/sites/default/files2/ewu_2002_1.pdf.

5 The more sophisticated 1991 hit for the PC DOS and Commodore Amiga platforms, ABC Wide World of Sports Boxing (aka TV Sports Boxing). In 1993, Philips released its own game based off the same core engine for their CD-i platform, Caesars World of Boxing. While each title has its advantages, Greatest Heavyweights arguably features the best action.

7 Sega’s Dream Machine,” Business Week, September 12, 1999.

8 Majesco also rereleased the Game Gear and some new games for a short time starting in 2000. This revision of the Game Gear was incompatible with the TV tuner add-on and some Master System cartridge adapters.

9 Perhaps most importantly, unlike every other Nintendo competitor who attempted to come up with a charismatic mascot of their own to go head-to-head with Mario, Sega’s Sonic had genuine staying power and is still one of the world’s most recognizable characters.

10 Many fans consider NHL ’94, which was also ported to the Sega CD and Super NES, the pinnacle of the series. Electronic Arts even included a version of the game in NHL 06 (2005) for the Sony PlayStation 2, though it was stripped of its official player rosters, as well as a special “NHL ’94 anniversary mode” in NHL 14 (2013) for Sony’s PlayStation 3 and Microsoft’s Xbox 360, which included updated graphics and rosters.

11 Despite rumors of aborted attempts at next generation revivals, and a cult following that remains to this day, Electronic Arts seems content to have let the Mutant League series die in deference to its popular lineup of licensed sports titles. Reality may have won out, but at what cost to gamers?

12 Sega commissioned Core Design to develop Streets of Rage 4 as a 3D beat-’em-up for the Sega Saturn. Unfortunately, a disagreement over developing ports for rival platforms meant that version was never published. Core Design did eventually release the game as Fighting Force on the Sony PlayStation and PC Windows platforms in 1997, as well as Fighting Force 64 on the Nintendo 64 in 1999. The games received mixed reviews.

13 In late 2012, WaterMelon Co. ran a successful Kickstarter campaign for Pier Solar HD, for the Sega Dreamcast, Microsoft Xbox 360, Android/Ouya, and Nintendo Wii U, as well as for computers running Windows, Macintosh, or Linux operating systems. The fourth print run for the Sega Genesis version was also announced!