History

Sega was the competition that Nintendo needed and deserved. The brand had risen to prominence with the Genesis, whose powerful technology and provocative advertisements allowed Sonic the Hedgehog to stand proudly next to his friendly rival, Mario. Although fans of both platforms like to emphasize their differences, in reality, Sega and Nintendo had much in common. Sure, Sonic was less polite than his plumbing counterpart, but he wasn’t about to start shooting cops and smacking bitches, either. The two companies played nice with the public, the media, and, for the most part, each other, keeping each other on their toes and moving the industry along at a pace they were both comfortable with.

Historically, Nintendo had relied on the popularity of its key franchises, Mario and Zelda, to move its systems. These games were popular for a reason: they were designed by Shigeru Miyamoto, a perfectionist with an uncanny skill for matching ambitious new game designs with marvelously intuitive controls. Sega, on the other hand, had based most of its appeal on its hightech image, tirelessly pointing out the alleged technical superiority of its systems and gadgets. After the Genesis, rather than waiting to release a completely new system, Sega had hedged its bets (and baffled consumers) with a bevy of add-ons, including the Sega CD and the Sega 32X. This experimentation might have been harmless enough; Nintendo was legendary for its lengthy hardware development cycles. However, when Sega learned that Sony was set to release their PlayStation, they panicked. Convinced that their new 2D-optimized console would compare unfavorably to the 3D-optimized PlayStation, they hastily rushed the Saturn into production before anyone—including their own engineers and developers—were ready for it. All that mattered was getting something, anything, onto the shelf before the PlayStation hit. The result, predictably, was a catastrophic failure, selling only 2 million units in North America before Sega threw in the towel just three years later.1 The PlayStation had won this round.

Sega regrouped, knowing they only had one last, desperate shot to stay in the console manufacturing game. The past series of failures had hurt them financially, but there was still hope they could make things right with a new console. Unfortunately, even with help from Microsoft, the Dreamcast would not be Sega’s salvation, but rather their tombstone.

The story of the Dreamcast begins in 1996, a year after the Saturn’s North American launch, when Bernie Stolar took over as CEO of Sega of America. Stolar had been the president of Atari’s home division, and he’d also oversaw the PlayStation’s development as executive vice-president of Sony Computer Entertainment America. He immediately saw that the originally 2D-oriented Saturn, despite its dual CPUs and 3D-capable graphics processors, could not compete with the PlayStation or Nintendo 64, which were both optimized for 3D gaming. The Saturn was capable of impressive results, but the system was just too complex for most developers to handle. For Stolar, Sega only had one option: kill the Saturn.

ChuChu Rocket!

ChuChu Rocket! (2000, Sega)

Despite its modest audiovisuals, Yuji Naka’s quirky puzzle game was still a technical achievement—it was the first online-enabled Dreamcast title. The object of the game is to guide one or more ChuChus (mice) on a level into one or more goals, while avoiding the roaming KapuKapus (cats). The ChuChus and KapuKapus move in predictable patterns and can be redirected with strategically placed arrows. Various play modes were available for up to four simultaneous gamers, which is where the fun factor really kicks in. As a nice value-add, a level editor allowed players to create their own puzzle levels to share with others online. Sega released ports of the game for the Game Boy Advance in 2001, iOS devices in 2010, and Android devices in 2011. As with any good puzzle game, several unofficial ports have also been released for a variety of additional platforms, though the Dreamcast original is arguably still the best. Forget about that bowling game; next time you have your non-gaming friends over, fire up ChuChu Rocket!

Aborting the Saturn stopped the financial hemorrhaging, but it also left Sega without an actively supported console on the market for over a year. It was a painful period, but Stolar knew that there was no other way to ensure there would be sufficient resources left for their last stand. The Saturn had been a costly mistake, but if the Dreamcast were to have any chance of success, Sega must keep looking forward, not back.

Earlier, Stolar had set the plan in conjunction with Sega of Japan CEO Hayao Nakayama. In contrast to earlier regimes, where American opinion on key company decisions held little value (see Chapter 3.3), Nakayama agreed to let Stolar shape the direction of the new platform and help restructure Sega.

Sega established two different teams to develop the Saturn’s successor. The American project, called Katana, was led by IBM’s Tatsuo Yamamoto. It was centered on the 3Dfx Voodoo graphics chipset, which had been a hit with PC gamers. The Japanese project, Dural, was led by Genesis designer Hideki Sato, and based on Hitachi and NEC technology. While NEC’s PowerVR graphics chipset didn’t have the same cachet as 3Dfx, its potential was just as strong. The competition was on, and the stakes had never been higher. Yamamoto and Sato knew that, whatever the outcome, the fate of the company was in their hands.

The best available technology won out. NEC’s PowerVR would not only lay the foundation for Sega’s next console, but also their next arcade board, NAOMI. In earlier days, Sega’s arcade technology had inspired related developments on the Genesis. Now it would be NAOMI’s turn to influence games on the Dreamcast. In fact, the arcade and home technology were closer than ever, especially with the NAOMI’s interchangeable games and economical, powerful hardware. It translated almost perfectly to the Dreamcast’s design.

Grandia II.

Grandia II (2000, Ubisoft)

While not as deep as the role-playing game library found on its 16-bit predecessor, Sega’s Dreamcast still featured several genre-defining stand-outs. Arguably the best of the bunch was Game Arts’ Grandia II. The sequel to the Japanese-only Sega Saturn original, Grandia (1997, 1999 for PlayStation), Grandia II was a more mature and technically advanced entry in the series. The plot follows a young mercenary, Ryudo, and his talking bird, Skye, as they protect a church songstress, Elena, and uncover the true history of their world, which was nearly destroyed a thousand years before by the gods. Featuring fully 3D graphics, the game sports a unique hybrid turn-based battle system that allowed for real-time actions, including moving into a better position to strike opponents or blocking at just the right time to mitigate damage. Later ports to the PlayStation 2 and Windows were technically inferior and bug-ridden, so the Dreamcast original remains the best. If you like this game, be sure to also check out Skies of Arcadia (2000, Sega), which, despite an excess of random battles, is another brilliant Dreamcast RPG classic that also makes a compelling case for best-in-class.

Stolar had a few more tricks up his sleeve. First, he convinced his Japanese colleagues that the new console should be bundled with a modem. This idea was clearly ahead of its time; online gaming had only just starting catching on with PC gamers. Next, he turned his focus to shifting developer resources to Dreamcast projects, including giving Sonic back to Yuji Naka’s Sonic Team. This time, the blue blur would get the chance to shine in a way denied him on the Saturn.

Unfortunately, all of this planning and effort didn’t help the Japanese launch on November 27, 1998. There were only four games available—the cutesy racer Pen Pen Trilcelon, city destroyer Godzilla Generations, adventure game July, and a poorly done arcade port Virtua Fighter 3tb—and none were any good. The Dreamcast had made its first impression, and it was a bad one. The publication of Sonic Adventure shortly thereafter better demonstrated the system’s capabilities, but it still left many Japanese gamers uncertain why Sega had abandoned the Saturn so quickly. Unlike their American counterparts, Japanese gamers had been much more forgiving of the Saturn’s flaws, and the Saturn fans there felt neglected, or even betrayed. So far, they’d seen little on the Dreamcast that justified abandoning the platform.

In the end, however, great games trump everything else, and Japanese fans finally had a Dreamcast game they could rally around: Seaman. Released on July 29, 1999, the bizarre virtual pet game was bundled with the official Dreamcast microphone for voice commands. It was the fledgling console’s first hit and was, if nothing else, unique. The gameplay had players helping to evolve a fish with a human face (that of its designer, Yoot Saito) from “Mushroomer” to “Frogman,” mostly by talking to it. Best described as a Monty Python-esque virtual pet “conversation” game, Seaman had players listening to trivia, trading insults, and witnessing some downright creepy facial expressions. It’s not clear (to us, anyway) why the game was so popular in Japan, but, like so many things, it did not translate well to other countries. Even after recruiting the great Leonard Nimoy of Star Trek fame to narrate it, Seaman’s North American release on August 9, 2000 had more gamers asking “What the hell?” than “How much?”

In the meantime, Sega was preparing for the Dreamcast’s North American debut. A soft launch in July 1999 at Hollywood Video retail chains gave gamers a chance to rent the console, but the full launch was targeted to September. The delay gave Sega a chance to get both its marketing and launch lineups in order.

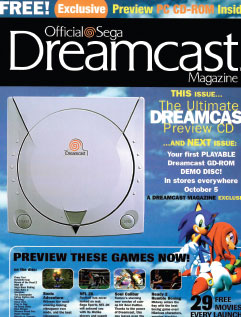

Sega’s Dreamcast received lots of pre-release hype, including from its Official Dreamcast Magazine, which came with a PC CD-ROM preview disc to help potential owners know what they’d be getting at launch. Shown here is a promotional cardboard insert.

The Genesis’ strong sales in the United States were due in no small part to its excellent sports titles. By contrast, the Saturn’s sports selection was miserable in comparison to the PlayStation’s. Stolar was determined to recapture the sports crowd with a mix of superior first and third-party games. He first purchased Visual Concepts, who had earlier attempted to develop a debut Madden title for Electronic Arts on Sony’s PlayStation. Although the game was never released, Stolar, who had architected the publishing deal, had liked what he saw. Visual Concepts was immediately put to work on a next generation football title. Stolar now turned his attention to the undisputed champion of sports gaming: Electronic Arts (EA).

When Stolar first knocked on their doors, he was told that EA wanted exclusive rights to develop sports games on the Dreamcast. Obviously, this request came at a bad time. The ink was still wet on the Visual Concepts deal, and there had long been plans to bring Sega’s arcade sports games to the Dreamcast. Therefore, Stolar had little choice but to refuse EA’s terms. Stung by the rejection, EA’s vice-president, Bing Gordon, angrily told Stolar, “You can’t succeed without us.” When Stolar still refused to sign, EA retaliated by refusing to release a single game on the Dreamcast. Stolar probably knew deep down that Gordon was right—without EA’s support, the Dreamcast was more than likely doomed. But he still refused to sign.

Dreamcast fans have little love for EA.

Jet Grind Radio (2000, Sega)

Called Jet Set Radio everywhere except North America, Jet Grind Radio featured one of the early uses of cel-shading, which outlined polygon graphics in such a way to make them look like cartoons. These innovative graphics were combined with an inspired street style that perfectly matched the funky soundtrack. Players take the role of a member of The GGs, a gang “fighting” to gain control of Tokyo-to while “battling” rival gangs and the police. Instead of using weapons, the player’s avatar rides on inline skates to jump, slide on rails, and skitch on the back of cars, while performing tasks like spraying graffiti over rival gangs’ work. A similar playing sequel, Jet Set Radio Future, appeared in 2002 for Microsoft’s Xbox, while an isometric reimagining of the Dreamcast original appeared on the Game Boy Advance in 2003, courtesy of THQ. A high definition update of the original also appeared on the respective digital stores for PlayStation 3, Windows, and Xbox 360 in September 2012. If you like the cel-shaded art style of Jet Grind Radio, be sure to also check out Wacky Races (2000, Infogrames), which takes the somewhat obscure Hanna-Barbera cartoon license and places it into a polished kart racer for the Dreamcast, brought down only by an unforgiving difficultly level later on in the game.

Legacy of Kain: Soul Reaver.

Legacy of Kain: Soul Reaver (2000, Eidos)

While released earlier for the Sony PlayStation and Windows computers, action adventure Legacy of Kain: Soul Reaver looked best on the Dreamcast, which is high praise for what was already a stellar looking game. While its predecessor, Blood Omen: Legacy of Kain, never appeared on the Dreamcast, Soul Reaver takes place 1500 years after the first game’s events, so no prior experience is necessary. Players take the role of vampire-turned-wraith Raziel, lieutenant to vampire lord Kain. Raziel is murdered by Kain, but is revived by the Elder God to become the titular Soul Reaver, which is also the name for the sword he acquires during the game and uses to help exact his revenge. The third-person gameplay consists of a combination of hack and slash fighting, switching between the material and spectral planes at will, and puzzle solving. While sometimes criticized for leaving its player wondering where to go next, the fact remains that Soul Reaver is one of the best third-person action adventures of its generation. For a more action-oriented third person game, be sure to check out BioWare’s MDK2 (2000), which features three very different playable characters.

When Stolar returned with the bitter news about EA, the team at Visual Concepts stepped up to the challenge. The burden was on them to prove that the Dreamcast didn’t need EA to bring the sports—and they delivered. Sega Sports’ launch title, NFL 2K, outclassed anything Electronic Arts would come out with for several years. In fact, after the Dreamcast launched in North America, NFL 2K was joined by a full and diverse lineup of titles that included AeroWings, AirForce Delta, Blue Stinger, Expendable, Flag to Flag, Hydro Thunder, Monaco Grand Prix, Mortal Kombat Gold, NFL Blitz 2000, Pen Pen Trilcelon, Power Stone, Ready 2 Rumble Boxing, Sonic Adventure, Soulcalibur, The House of the Dead 2, TNN Motorsports Hardcore Heat, Tokyo Xtreme Racer, and TrickStyle. Clearly, Sega had learned from their mistakes with the Japanese launch, this time offering a truly representative selection of games that demonstrated the Dreamcast’s technical superiority over the PlayStation and Nintendo 64.

Luckily for Sega, US gamers responded well to the launch. The 300,000 pre-orders set a new record, and 500,000 of the $199.99 consoles went home in just two weeks. Amazingly, 225,132 Dreamcasts were sold in the first 24 hours alone.2 Needless to say, the champagne was flowing at Sega headquarters. The long nightmare was over; Sega was saved.

Tragically, the momentum was short-lived. Despite strong North American and European sales (where it launched on October 14, 1999), sales remained tepid in Japan, contributing to large consecutive annual losses for the company. As described in Chapter 3.5, after the PlayStation 2’s launch in Japan on March 4, 2000, interest in the Dreamcast waned even further. Six of the PlayStation 2’s launch titles were EA’s, including sports juggernauts Madden NFL 2001 and NHL 2001. Back at his Sega headquarters, Stolar watched miserably as the sales reports grew bleaker. The Dreamcast was a great system, but it was just too little, too late. Perhaps things would have gone differently if he’d signed with EA, perhaps if he’d killed the Saturn sooner or perhaps let it live a bit longer, or perhaps if people weren’t still laughing about the fish game—maybe then the Dreamcast would have made it. But now the dream was over, and perhaps wasn’t going to help move the furniture out of the building.

Sega officially discontinued Dreamcast production on March 30, 2001. The last North American release was, fittingly, NHL 2K2 in February 2002, which again proved itself one of the best sports games on the market. Interestingly, Sega supported the Dreamcast longest in Japan, where it had been the least successful. Sega of Japan continued selling refurbished systems and releasing new software until 2007, when the company finally stopped producing the Dreamcast’s GD-ROM optical discs. Many of the final titles were ports from Sega NAOMI arcade hardware, which was still a thriving business in the region.

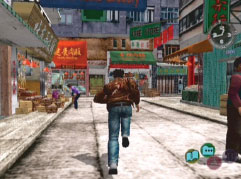

Free roaming adventure game Shenmue (1999 in Japan, 2000 in North America), was one of the most ambitious and costly titles ever produced, with a budget of $47 million. Combined with its sequel, development cost Sega an estimated $70 million. Disappointing relative sales for the titles did Sega’s financial situation no favors.

Power Stone 2 (2000, Capcom)

Released in 1999, Power Stone was a remarkably innovative Naomi-based arcade and Dreamcast fighting game. The sequel, released for the same two platforms in 2000, took the best features from its predecessor and added more options. Up to four players can duke it out in different arenas using in-level melee and projectile items, like tables, chairs, rocks, guns, flamethrowers, hammers, bear traps, and more. There’s also an interesting adventure mode, which plays similarly to the main battle modes, but with an ongoing item and money inventory that can be traded for and mixed in an item shop, extending the game’s longevity far beyond that of typical brawlers. As a bonus, there’s a VMU application called the Mini-Book, which lets players inspect their inventory and trade items with other players. Whether played alone or with three other friends, Power Stone 2 won’t disappoint. In 2006, Capcom ported the two games to Sony’s PlayStation Portable as the Power Stone Collection.

While hardly a smashing success in its short life, the Dreamcast still sold over 10 million consoles worldwide, with over 2 million in Japan, 4 million in North America, just under 2 million in Europe and Australia, and just over 2 million everywhere else.3 Afterward, Sega abandoned console manufacturing and became a third-party software developer.

Despite its tragic flaws, the Dreamcast, thanks to its unusual hardware and strong games library, is worthy of an honored place in the annals of gaming history. And if reading this chapter has made you sad, we know a fish you can talk to.

Technical Specifications

The Dreamcast had a powerful and versatile internal architecture. The CPU was a 32-bit SH-4 running at 200 MHz, but enhanced by an on-die 128-bit vector graphics engine. Its graphics hardware was the PowerVR2 CLX2 chipset, capable of a peak performance of 7 million polygons per second with trilinear filtering—and a variety of built-in hardware effects to boot. Resolution was 640x480 interlaced or progressive scan, with up to 16.78 million colors. Sound hardware was equally impressive. The Yamaha AICA Sound Processor had a 32-bit ARM7 RISC CPU operating at 45 MHz, and a 64 channel PCM/ADPCM sampler with 4:1 compression, XG MIDI support, and a 128 step DSP. Suffice it to say, this box could bring the bump.

The Dreamcast had 16 MB of main RAM, 8 MB of dedicated video RAM, 2 MBs for system ROM, 128KB of flash memory, and 2 MB just for sound. The proprietary optical GD-ROM drive (Gigabyte Disc Read-Only Memory) was capable of reading discs up to 1.2 GB in capacity. The GD-ROM drive was also compatible with standard CD-ROMs, including music CDs, which the Dreamcast can also play. It could not, however, play DVD movies like the PS2 or Xbox.

On the top of the console was a power button and an open button, which opened the GD-ROM door. To the rear of the console, from left to right, was the line in for the detachable 56 kbit/s dial-up modem, AV out, serial port, and AC in, for the power cable.

The Dreamcast’s controller had two expansion slots, or dock connectors, often used for the VMU and Jump Pack.

Like the Nintendo 64 before it, the Dreamcast not only had four controller ports, found on the front of the console, but also further expanded upon the idea of expandable controllers with not one, but two expansion slots, or dock connectors. The controller features an analog stick, digital direction pad, triangular start button, two analog triggers, and four action buttons, which include a yellow X button on the left, a red A button on the bottom, a blue B button on the right, and a green Y button on top. To the frustration of some gamers, instead of the controller’s connection cord coming from the top of the controller, it comes out the bottom.

While the VMU had a low resolution LCD display, the screen’s contrast was still sharp.

Typically, the controller’s two dock connectors were filled with some combination of memory card or Jump Pack (haptic feedback rumble pack), first- or third-party, and a Visual Memory Unit (VMU). The VMU could be snapped into the controller’s first dock connector so that its screen showed through the opening. This allowed the VMU’s low resolution LCD screen to be used as an auxiliary display—a cool innovation with a lot of potential, only some of which was realized in the Dreamcast’s brief lifespan.

Of course, the VMU was more than just a secondary display. Without batteries, the VMU still functioned as a memory card and auxiliary display, but when powered by two CR-2032 lithium batteries, it can also work independently from the Dreamcast. In this mode, it could play simple downloadable games and facilitate transfers (or even multiplayer gaming) when plugged into another VMU. Helping the VMU with this extra functionality were a front-facing digital direction pad and four buttons, including small sleep and mode buttons, and large A and B action buttons. A built-in speaker allowed sound from its simple 1-channel PWM sound source. The VMU has 128KB of flash memory for storing saved games and other data, although 28KB of space was reserved for system use.

Finally, no discussion of the Dreamcast’s technical features would be complete without mentioning the operating system. There is no built-in operating system; instead, it’s always loaded from a disc. The advantage to this was that developers could ship their games with the latest version of the operating system, complete with all the newest features and performance enhancements. There was, therefore, no anxiety about their games suddenly breaking after an official update from Sega. Microsoft wanted their Windows CE, which supported DirectX, as the primary operating system for the Dreamcast, but Sega decided to go with a two-pronged approach instead: developers could choose to use Windows CE or Sega’s own custom operating system. Most games were developed using Sega’s operating system, which had better performance, but the Windows CE option made it easier to bring over a fair number of ports. Unfortunately for both companies, the potential benefits of the Windows CE option was never fully realized in the Dreamcast, but it clearly whet Microsoft’s appetite for greater investment into the console business (see Chapter 3.6).

Resident Evil Code: Veronica (2000, Capcom)

While the first three Resident Evil games debuted on the Sony PlayStation, Resident Evil Code: Veronica was the first new entry in the survival horror series to debut on a rival platform. Sony’s loss was Sega’s gain, as Capcom pulled out all the stops to make this the best Resident Evil game yet, and arguably, the best for many sequels yet to come. Resident Evil Code: Veronica kept the series’ tank-like character controls, but the pre-rendered backgrounds were now in true 3D, allowing for real-time lighting and limited camera movement. It also added two new weapons that could be fired from a unique first person perspective. Further improvements abound, including brilliant new cut scenes made possible by the Dreamcast’s more powerful hardware, various dual-wielding pistols, which allowed targeting two enemies at the same time, and more finely tuned difficulty, allowing players to retry failed scenes and quickly pick up and use healing herbs even if the character’s inventory is full. Several updates of the game were released, including Code: Veronica X for the Dreamcast (2001, Japan only), PlayStation 2 (2002) and Nintendo GameCube (2003), which featured new and updated cutscenes, as well as minor graphical changes to the main game. If you like this game, be sure to check out Capcom’s Dino Crisis (2000), which was their take on “Jurassic Park-meets-Resident Evil.” While a port of the PlayStation original and not as well implemented as Resident Evil: Code Veronica, it’s a nice change of pace from traditional survival horror themes.

SoulCalibur.

SoulCalibur (1999, Namco)

Namco’s SoulCalibur, the sequel to Soul Edge (1996), started life as a Namco System 12 arcade game in 1998. For its 1999 Dreamcast port, Namco greatly enhanced the audiovisual quality and added in new features, creating one of the finest fighting games ever made in the process. A one-one-one 3D weapons-based fighting game, SoulCalibur’s greatest innovation was its unprecedented freedom of movement. Beyond simple sidesteps or rolls, SoulCalibur let players maneuver in any direction, creating deeper strategic gameplay possibilities than almost any other fighter of its era. What’s perhaps most amazing, however, is that this was one of the Dreamcast’s launch titles, so the remarkable degree of polish and audiovisual mastery of the console’s hardware by the developers is a true tour de force. Fighting game fans owe it to themselves to play this masterpiece, which many Dreamcast fans consider the best game on the console. While not quite as dazzling, Tecmo’s Dead or Alive 2 (2000) is also worth checking out for fans of the genre.

While there were online or connected experiments for everything from the Atari 2600 and Mattel Intellivision to the Sega Genesis, Super Nintendo, and Sega Saturn, the Dreamcast was the first console to offer a truly modern, unified experience. Even with a relatively primitive implementation, the Dreamcast’s built-in online capabilities cannot be overstated, and it’s what later allowed Microsoft’s Xbox Live to dominate the console world. The important thing was that every Dreamcast had access to the online component, not just ones who sprang for an add-on. That guaranteed that developers would be much more likely to support the functionality.

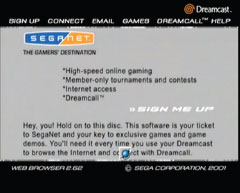

Using its built-in dial-up modem, players could connect with their own ISP or sign up for Sega’s Seganet service. While the configuration process was a bit of a hassle, it had the virtue of actually working as advertised. The included PlanetWeb Browser went through several revisions, each of which added functionality or improved compatibility. Later, Sega offered a broadband adapter (BBA) as a one-to-one replacement for the dial-up modem, though this saw limited release. It would take the competition years to catch up.

Space Channel 5.

Space Channel 5 (2000, Sega)

A rhythm game following the quirky exploits of charismatic space reporter Ulala, players must copy the sequence of movements performed by her onscreen opponents, synchronized to the music. As with any good rhythm game, the music and atmosphere make it or break it, and Space Channel 5 has both in abundance. If you like your rhythm games eccentric, Space Channel 5 delivers. For example, keep an eye out for a cameo from Michael Jackson later in the game as Space Michael. HEE HEE! If you want to spice up your rhythm gaming, be sure to grab some maraca controllers and check out a copy of Samba de Amigo.

Naturally, there was more to do with the Dreamcast’s modem than browse the web. Several dozen games were released that either allowed for competitive online play (Bomberman Online), online rankings (Crazy Taxi 2), or provided access to extra content (Floigan Bros.). While all of the official servers have long gone offline, multiple unofficial servers are still active that provide support to those gamers who still want to get online with their Dreamcast. That should tell you something about the quality of the Dreamcast’s online experience.

The start screen for version 2.62 of the PlanetWeb Browser.

The Accessories

The Dreamcast supported a proprietary keyboard and mouse, which was useful for the web browser, as well as select games, like first-person shooter, Quake 3 (2000, id), or MMORPG Phantasy Star Online (2001, Sega). Several third-party options and adapters were also available.

The official Dreamcast keyboard shown above the box for the official mouse. The Fishing Controller is shown next to a pair of third-party maracas.

Beyond the usual third-party controllers, arcade sticks, and light guns, the Dreamcast featured two rather unusual controllers in its lineup: the Fishing Controller and the Samba de Amigo Maracas Controller. The motion sensitive Fishing Controller lent a “reel-alistic” haptic dimension to games such as Sega Bass Fishing (1999) and Reel Fishing Wild (2001, Natsume). The Samba de Amigo Maracas Controller and its third-party alternatives consisted of a plastic mat that players stood on and two wired maracas that connected to a sensor bar. There might be someone out there who wouldn’t enjoy playing the wacky and hilarious rhythm game Samba de Amigo with these controllers—if such a person is found, please feel free to apply the maracas in a different manner.

One of the more popular accessories is the VGA adapter (or third-party equivalents), which allowed Dreamcast games to be played on high resolution monitors or HDTVs in the console’s highest resolution, 480p. While this is a significant improvement over standard RF, composite, or even S-VIDEO output, not every game supports VGA. As a result, many VGA adapters also have composite and S-VIDEO outputs for maximum compatibility. Of particular note is that VGA is what the Dreamcast outputs natively.

The Typing of the Dead (2001, Sega)

The best use of a Dreamcast keyboard is not in fact, the web browser, but instead is this unusual shooting game. Loosely based on The House of the Dead 2 (1998) light gun-based arcade game, The Typing of the Dead had you blasting zombies by typing the words that appear above their heads as quickly as possible. It’s funny, strange, and a challenge for even the best typists, as well as a classic example of Sega’s willingness to experiment. If you like the zombie typing fun, be sure to grab a light gun and check out the regular Dreamcast ports of the arcade House of the Dead games, which are a literal blast to play.

Two link cables, which connected to the SERIAL port, were released for the Dreamcast. One, the Vs Link Cable, connected two Dreamcasts together for head-to-head play and was supported by just a half dozen games, including robot battler, Virtual On: Oratorio Tangram (2000, Sega). The other was the Dreamcast to Neo Geo Pocket Color link cable from SNK, which connected SNK’s failed Game Boy competitor, the Neo Geo Pocket Color, to the Dreamcast and allowed for data transfer between the small selection of compatible games, including fighting game, Capcom vs. SNK: Millenium Fight 2000 (2000, Capcom).

Virtua Tennis.

Virtua Tennis (2000, Sega)

On a system filled with so many great sports games (although oddly, never a good interpretation of baseball), it’s surprising that a tennis title would make the list. With no particular dependence upon having the latest and greatest rosters, and gameplay that has arguably not been improved upon since, Virtua Tennis was actually an easy choice to make. With a quick learning curve, wide variety of fun training mini-games, and choice of several game modes, this modern update of Pong will have you making a racket. Who cares if you’re not into tennis? The only major downside is the lack of female athletes—you’ll need to play the 2001 sequel for that.

The Sega Dreamcast Community Then and Now

Although the Dreamcast was short-lived, its fan community was not. Indeed, now is the best time ever to own a Dreamcast. The homebrew selection alone is worth buying a system for.

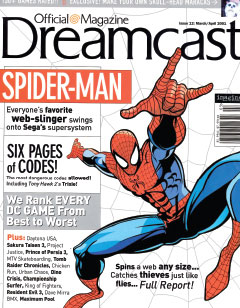

Official Dreamcast Magazine’s inspired content provided a wonderful resource for fans of Sega’s underdog console to rally around. http://archive.org/details/Official_Dreamcast_Magazine_The_Issue_01_1999-09_Imagine_Publishing_US.

All of the general gaming magazines of the day provided excellent coverage of the Dreamcast. No magazine did a better job, though, than the Official Dreamcast Magazine, whose first issue was September/October 1999. It ran for 12 issues, with its last being the March/April 2001 edition. Almost every issue was bundled with an impressive GD-ROM disc filled with demos. The editorial style was fun, witty, and informative. Many of its best design elements were recycled for the Official Xbox Magazine.

Unlike the majority of disc-based consoles, copy protection is usually not an issue with the Dreamcast. Depending upon the exact model of Dreamcast, both games from other regions and burned CD-R discs can usually be played on the console with no fuss, though sometimes a special boot disc, like Utopia, is required. That, too, however, can easily be burned onto a regular CD-R disc.

Because of its flexibility, not only can the Dreamcast play backups of commercial games, but also a diverse array of emulators. A Dreamcast SD card adapter even allows software to be run without any further intervention from the GD-ROM drive. Did we mention that now is the best time ever to own a Dreamcast?

A selection of boxed original Dreamcast games, as well as three modern homebrews: Inhabitants, Maquipai, and Cool Herders.

Homebrew software is particularly robust, with not only the aforementioned emulators and ports from other systems, but plenty of original games as well. As a favorite of hardcore gamers, shoot-’em-ups are particularly well represented on the Dreamcast, with games like Last Hope (2007, RedSpotGames), DUX (2009, HUCAST.Net & KonTechs Ltd.), and Sturmwind (2013, RedSpotGames) giving many commercial releases a run for their money. Of course, if shooting stuff is not your thing, other releases, like multiplayer collect-’em-all Cool Herders (2002, HarmlessLion Games), rhythm game Feet of Fury (2003, GSP), and puzzle game Wind and Water: Puzzle Battles (2009, RedSpotGames), will surely fit the bill. Better yet, playing all these fun homebrew titles might well inspire you to take a stab at creating your own!

Collecting and Emulating Sega Dreamcast Systems

Finding a working Sega Dreamcast console is not a costly proposition, though you do need to pay attention to how well the GD-ROM works, which is a typical point of failure. Most software is still easy to find, although there are the usual selection of rarities for which demand exceeds supply.

Released September 9, 2000, the Sega Sports Pack included a black console (pictured), black controller and VMU, and copies of the Sega Sports titles NBA 2K and NFL 2K. Photo courtesy of Evan-Amos, Vanamo Media.

The two major North American console colors were the standard light grey and black, which was originally available in the Sega Sports Pack bundle with NBA 2K and NFL 2K, as well as matching controller. Other, more limited special editions with minor cosmetic variations were released by select retailers or for special events. Many aftermarket colored shells were also sold, which were relatively easy to apply to the system to change its coloring.

The Chankast emulator running the popular comic sports game Ready 2 Rumble Boxing.

Although the Dreamcast can be a challenge to emulate for today’s systems, there are presently two worth noting that do a commendable job: Chankast and nullDC. The former supports Windows computers, while the latter supports both Windows and Linux.

1 Sega continued selling the system until 2000 in Japan.

2 www.g4tv.com/gamemakers/episodes/1259/Sega_Dreamcast.html.

3 Blake Snow, “The 10 Worst-Selling Consoles of All Time,” GamePro, May 4, 2005.