History

From the 1970s into the 1990s, the home videogame industry had been dominated by three companies: Atari, Nintendo, and Sega. Nintendo had managed to buck Atari from the top spot, a feat made easier thanks to the Great Videogame Crash. Atari’s failed Jaguar (launched on November 15, 1993) was the last time the former giant’s brand would grace a console. With Atari out of the picture, Nintendo and Sega settled in for what would hopefully be a long and relatively unchallenged rivalry for control of the console market.

When Sony announced its new PlayStation console, the executives at both companies had little reason to panic. The PlayStation seemed like only the latest in a line of failed CD-based systems. Why should they take Sony seriously when Commodore, Philips, and Panasonic had all tried a similar tactic and failed miserably? Even if no one else believed they had a shot, Sony was ready to go big or go home—a fact attested by the minimum $500 million they invested in the new device.1 Ready or not, Mario and Sonic were about to meet their match.

Crash Bandicoot on the ePSXe emulator.

Crash Bandicoot (1996, Universal Interactive Studios)

Prior to Crash Bandicoot, Naughty Dog (nee Jam Software) was perhaps best known for their mediocre photo-realistic fighting game for the 3DO, Way of the Warrior (1995),2 one of many such titles that failed to match Mortal Kombat. It’s surprising, then, that Naughty Dog was the first to create a 3D platform game with the approachability and accessibility of the best traditional 2D side-scrollers. Even when the perspective changed between stages to mix up the challenge, there was no camera control to fight with, as the linear setup allowed Naughty Dog to always provide a clear view through the lushly illustrated levels. The game’s vibrant aesthetics and charming personality helped propel its titular character to mascot status. The success of Crash Bandicoot 2: Cortex Strikes Back (1997) and Crash Bandicoot: Warped (1998) proved the first hit was no fluke. Crash Team Racing (1999) was yet another hit, and one of the few successful attempts at mimicking Super Mario Kart from Nintendo’s Super NES. If you’re looking for a less linear 3D platformer, try Spyro: Year of the Dragon (1998, Universal Interactive Studios), from Insomniac Games, which kicked off another franchise.

On the back of a successful Japanese launch in December 1994, Sony unleashed its PlayStation on the US market on September 9, 1995. The timing couldn’t have been better. The Atari Jaguar and 3DO Interactive Multiplayer (launched on October 4, 1993) had joined the Sega Genesis and Nintendo Super NES on their respective deathwatches, hoping to eke out a few last orders before the inevitable next generation consoles rendered them all obsolete. Gamers were ready for something new, and not many were willing to wait patiently for Nintendo or Sega to rise to the occasion.

Sega was the first to respond to Sony’s threat, hurriedly releasing their own next generation console called the Saturn on May 11, 1995. They’d rushed it to production well ahead of schedule, and succeeded in beating everyone else to the punch. Unfortunately, the truncated production cycle had left them with a poor selection of buggy launch titles. It was difficult even for some Sega diehards to get excited about the system. Adding further insult to injury, the Saturn’s retail price was $399, while Sony promised their PlayStation’s would only cost $299—a promise they were willing and able to keep. Sega clearly had good reason to worry about what Sony was up to. However, their decision to prematurely launch the Saturn was a poor one with disastrous consequences for the company’s future (see Chapter 3.4).

Still, what did Sony really know about videogames? While the company was well regarded for the high quality of their electronics—especially the Sony Walkman—they were neophytes in the world of videogames. Their previous videogame experience consisted mostly of mediocre titles for the Genesis, Sega CD, and Super NES. Meanwhile, the PlayStation’s bizarre-looking controller suggested that the company just didn’t grasp gaming.

An early two-page ad in the August 1995 NEXT Generation magazine for the Sony PlayStation featuring the short-lived “Polygon Man” mascot. The game featured in the ad, Battle Arena Toshinden, was a mediocre fighting game, but its 3D graphics dazzled and helped make it a hit when the PlayStation was officially released.

With so much skepticism growing among consumers, Sony clearly needed a tight and effective marketing campaign. Unfortunately, their early efforts were clumsy and potentially ruinous. Intended as a sarcastic, literally edgy, mascot, “Polygon Man” appeared in pre-launch ads featuring upcoming PlayStation games. While striking in appearance, the disembodied head had all the charm and charisma of… a disembodied head. Among the unimpressed was Ken Kutaragi (see Chapter 2.5), the global head of the PlayStation brand. As recounted by Phil Harrison, former head of Sony’s European publishing business, Kutaragi was furious about wasting their limited resources developing an alternative brand. What really incensed him, however, was that the design of the character was flat shaded, not Gourad shaded.3 This was a significant misstep because the advanced Play-Station technology featured the noticeably smoother and better lit polygons that Gourad shading offered; flat-shading was obsolete. By the US launch, Polygon Man was phased out in favor of actual in-game characters, although the basic style of the ads remained the same.

Fear Effect 2: Retro Helix (2001, Eidos)

Fear Effect 2: Retro Helix may be best known for its puerile advertising campaign, which featured protagonists Hana Tsu-Vachel and Rain Qin romping around together in a sexually suggestive manner. However, the actual game featured an unusually mature and sophisticated storyline for its era. The relationship between the two of the four main characters was indeed romantic and at times gratuitous (in one scene, Hana and Rain make out in an elevator to distract some male guards), but with just a few such exceptions, this action-adventure broke new ground with its rich character development. This puzzle-driven game was also notable for its striking visuals, which used cel-shaded 3D character models on top of 3D backgrounds that were themselves overlaid with looping full-motion video clips. The player alternated between four different characters as the story progressed, providing a dynamic, multilayered narrative. The vibrant visuals and complex story, spanning four discs, made this game a unique entry in the survival horror genre. Unfortunately, a planned PlayStation 2 sequel was canned when publisher Eidos ran into serious financial problems, which also doomed plans for a movie.

Despite the rocky lead-up to launch, the console’s debut went smoothly. While the launch fanfare paled in comparison to Windows 95 (see Chapter 3.1), gamers lined up in front of retailers like Electronic Boutique, eager to get their hands on Sony’s product. Sony owed this momentum to a solid launch lineup that was both diverse and effective at showing off the PlayStation’s impressive 3D capabilities. These titles included Air Combat (Namco), Aquanaut’s Holiday (Sony), Battle Arena Toshinden (Sony), ESPN Extreme Games (Sony), Jumping Flash! (Sony), Kileak—The DNA Imperative (Sony), NBA Jam TE (Acclaim), Power Serve 3D Tennis (Ocean), Rayman (Ubisoft), Ridge Racer (Namco), Street Fighter: The Movie (Acclaim), The Raiden Project (Sony), Total Eclipse Turbo (Crystal Dynamics), and Zero Divide (Time Warner Interactive). There was something for nearly every taste, thanks in part to Harrison’s uncanny ability to attract talented developers and publishers like Namco and Ubisoft.

The “Dino” tech demo from the PlayStation Developer’s Demo disc. While the dinosaur looked great and was fully interactive, 3D models in actual games were necessarily lower in quality because of the extra demands on the console.

Sony also rejected convention by omitting a pack-in game. Instead, they bundled a pack-in sampler disc, PlayStation Picks. No doubt, some gamers were appalled by what looked like a miserly move on Sony’s part. However, the sampler disc contained lots of fun, playable game demos. Some retailers even tossed in the PlayStation Developer’s Demo, which was a pre-release audio CD with a special track, only playable on a PlayStation, which featured amazing tech demos. If Sony had faltered before, they were making up for it now, and soon gamers all over the world were buzzing about the PlayStation.

A scene from the “Movie” tech demo from the PlayStation Developer’s Demo disc, an excellent example of the improved colors and motion video quality possible on the PlayStation. While nowhere near the near DVD-level video quality of the next generation of systems, it was a marked improvement over what the previous generation of CD-based systems was capable of.

Sega’s Saturn was a competent system, but the PlayStation’s inherent 3D capabilities put it in another class. The competition stiffened after Nintendo finally released the Nintendo 64 in the US on September 29, 1996—over a year later. Nintendo hadn’t squandered the time, though. Super Mario 64 was a masterpiece of 3D game design, perfectly matched to an innovative new controller. Sony may have clobbered Sega, but Nintendo seemed more than capable of dealing with the upstart Sony head-on. In fact, if not for Nintendo’s decision to stick with cartridges instead of moving on to optical discs, they might well have succeeded. Instead, Sony’s decision to embrace optical discs made them extremely popular with developers, many of whom switched sides to support the newcomer.

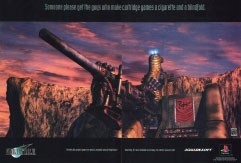

The infamous Final Fantasy VII ad that drove a dagger through the hearts of Nintendo’s fans and helped establish PlayStation’s dominance once and for all.

Among these renegades was Squaresoft, who delighted Sony (and mortified Nintendo) by making their masterpiece, Final Fantasy VII, exclusive to the PlayStation. For legions of role-playing gamers, this title alone was worth the price of admission. Supported by an ambitious marketing campaign and the technical wizardry to back it up, Final Fantasy VII (published by Sony in 1997) made Nintendo’s decision to cling to cartridges look foolish, and set the tone for the remainder of the generation. There had been plenty of epic Japanese role-playing games before it, but Final Fantasy VII’s three CDs worth of content took the genre to the next level. It sold close to 10 million copies worldwide, placing it third in total platform sales—just behind Sony’s remarkably detailed (and obsessive) racing simulations Gran Turismo (1998) and Gran Turismo 2 (1999).4

By March 31, 2005, Sony had shipped a total of 102.49 million PlayStation consoles,5 becoming the first videogame console to move so many systems. Sony would repeat this stunning feat with the PlayStation 2 (Chapter 3.5). “Playing Atari” and “playing Nintendo” were once common parlance for playing videogames. Now gamers were “playing PlayStation.”

Final Fantasy Tactics on the ePSXe emulator.

Final Fantasy Tactics (1998, Squaresoft)

Despite leveraging themes from previous games in the Final Fantasy series, Final Fantasy Tactics was still a risky new venture for Squaresoft that, ultimately, paid off handsomely. Not only were they trying a new concept with the idea of a tactical role-playing game, they also introduced a new game world and engine, which used a fully 3D, isometric, rotatable playing field, complemented by detailed character sprites. Set in a fantasy kingdom called Ivalice, the game’s story followed Ramza Beoulve, a highborn cadet who finds himself thrust into the middle of the Lion War, where two opposing noble factions are fighting over their respective claims to the kingdom’s throne. Players recruited generic player characters and customized them using the Job system made famous in the original Final Fantasy role-playing series (whose characters made appropriate cameos). Composers Hitoshi Sakimoto and Masaharu Iwata teamed up to create more than 70 stirring orchestral scores. While the localization of this Japanese original was not without issues, enough of its brilliance shown through to establish it as the first entry in a popular new franchise.

Technical Specifications

A look inside the PlayStation reveals the progressive attitude of its designers. Unlike Nintendo, who favored value over performance, Sony was all about the cutting edge. The PlayStation contained an LSI LR333x0-based Core, which consisted of a 32-bit MIPS Computer Systems R3000A-compatible RISC chip running at 33.8688 MHz and 2MB of RAM. Inside the main CPU chip was a geometry transformation engine, which provided additional vector math instruction processing that enabled 66 MIPS of operating performance. That translates to 360,000 polygons per second, or 180,000 that are texture mapped and light-sourced. An MDEC was responsible for decompressing images and full-motion video.

The PlayStation’s GPU processed 2D graphics separately from the main 3D engine. This allowed for resolutions from 256 × 224 to 640 × 480 (320 × 240 being the most common), with a maximum of 16.7 million colors. There was 1 MB of Video RAM (VRAM). The Sound Processing Unit (SPU) supported ADPCM sources with up to 24 channels, as well as a sampling rate of up to 44.1 kHz. There was 512 kB of memory dedicated to sound processing.

The internal CD-ROM drive ran at 2x speed, with a maximum data throughput of 300 kB/s. Besides PlayStation CDs, the CD-ROM drive could also play audio CDs with a built-in player program.

The original PlayStation console model, the SCPH-1001, had three buttons on top. To the right of the CD lid was the button that flipped it open. To the left of the CD lid was a power button placed just above an LED indicator. Above the power button was a small reset button.

Two controller ports, each with a memory card slot above them, were on the front of the console. The optional memory cards, which had an initial capacity of 128 kB, were used to store saves and other game data. Using the built-in utility, owners could manage the data on the memory cards, including copying the information to other cards.

Klonoa on the ePSXe emulator.

Klonoa: Door to Phantomile (1998, Namco)

In this uniquely styled platforming adventure, players took control of the titular anthropomorphic cat creature and a “spirit” encapsulated in his ring, Huepow. A crashed airship, foretold in one of Klonoa’s dreams, set the two friends off on an epic, branching adventure. While the game was rendered in three dimensions, all action took place on a 2D plane, which allowed for the type of precise maneuvering and enemy-bashing jumps reserved for the best games in the genre. For more platforming fun, check out Tomba! 2: The Evil Swine Return (1999, Sony), which, while played from a more traditional side-scrolling perspective, featured an even wackier theme.

To the rear of the console, from left to right, was a parallel I/O, serial I/O, audio out (stereo R and L connectors), RFU DC out (for an RF modulator), video out (composite), AV multi out (up to S VIDEO), and AC in (for the power plug). The parallel I/O was primarily used for unofficial cheat/region free cartridges, while the serial I/O enabled two PlayStation consoles to be connected via the PlayStation Link Cable. A few dozen or so games supported this feature, which required two PlayStation consoles, two TVs, and usually two copies of the game. While seldom supported and hardly a major selling point, the feature marked a significant improvement over split screen multiplayer.

Three cosmetically similar major revisions were introduced after the SCPH-1001. The first revision was the SCPH-5001, which dropped the dedicated audio out, RFU DC out, and video out ports. The second revision was the SCPH-7001, which came standard with the DualShock controller and introduced SoundScope, which was a graphical light show representation of the music that was playing when an audio CD was inserted. The buttons on the controller could change between 24 patterns and other effects, which could be saved to a memory card. The third revision was the SCPH-9001, which also dropped the parallel I/O.

While several model variations were introduced before and after the three major revisions, in 2000, Sony released a completely new design to go along with the PlayStation 2’s launch. The PSone as it was called, which for a time outsold the PlayStation 2, was considerably smaller than any of the previous PlayStation consoles. Besides the obvious cosmetic differences, the PSone also dropped the SERIAL I/O port and utilized an external power supply. This would be the last PlayStation model produced, with production officially ending in March 2006, over 11 years after its original Japanese launch in December 1994.6 Freeing up production (and focus) helped Sony launch the PlayStation 3 in November 2006.

Sony had made the right move by focusing on 3D gaming. Whereas most of the previous competition had lesser capabilities (3DO) or tacked on support (Sega Saturn), the Play-Station was designed with 3D games firmly in mind. Still, one area where they stumbled was in the design of their original controller, which mimicked designs from 2D consoles.

The original PlayStation shown with its first (left) and revised DualShock controller (right).

Metal Gear Solid on the ePSXe emulator.

Metal Gear Solid (1998, Konami)

While the concept of a stealth-driven action-adventure was nothing new, console gamers had yet to experience the anxiety-provoking gameplay of masterpieces like Castle Wolfenstein (1981) or Thief: The Dark Project (1998). That changed with the release of Hideo Kojima’s Metal Gear Solid for the PlayStation. While previous games in the Metal Gear series were brought to the NES, they were pale, heavily modified imitations of the classic MSX computer original. With Metal Gear Solid, console gamers finally had a definitive, no compromise stealth game of their own. The sequel to Kojima’s previous masterpiece, Metal Gear 2: Solid Snake (1990), for MSX2 computers, Metal Gear Solid took the series into a bold new third-person 3D direction. Featuring cinematic cutscenes rendered with the powerful in-game graphics engine and full voice acting, Kojima and his team leveraged the full power of the PlayStation’s hardware. Players took the role of soldier Solid Snake, who must infiltrate a nuclear weapons facility to both liberate hostages and neutralize a terrorist threat from renegade special forces unit, FOXHOUND. While there’s plenty of action, players must often resort to using Solid Snake’s stealthier capabilities to remain undetected, including crawling under objects, ducking behind walls, and making noises to distract an enemy’s attention. With such masterful execution, it’s no wonder that all future titles in the series would expand upon its foundation. If you like this game, be sure to also check out Activision’s Tenchu 2: Birth of the Stealth Assassins (2000), which featured similarly stealthy gameplay, but also let players design their own missions, including level layouts, usable characters, and mission objectives.

On the front of the controller, from left to right, was a digital directional pad, select button, start button, and circular action buttons that featured a green triangle (top), a red circle (right), a blue X (bottom), and a pink square (left). These geometric shapes would soon become iconic and be incorporated in PlayStation branding. On the top of the controller were two pairs of shoulder buttons. Since the middle fingers were used to press the bottom shoulder buttons, there were elongated grip handles for better balance. Crucially, the controller was missing an analog joystick.

Early PlayStation games, such as the innovative first person platformer, Jumping Flash! (1995, Sony), and the legendary third-person action adventure, Tomb Raider (1996, Eidos), were easy enough to control. However, Super Mario 64 (1996) on the Nintendo 64 (Chapter 3.3), which took full advantage of that console’s analog controls, revealed the inherent flaws in the PlayStation controller’s design.

Fortunately, Sony developed a superb series of retrofits in 1997, starting with the Dual Analog Controller, which had dual analog sticks. The design culminated in the classic DualShock, which further refined the Dual Analog Controller’s design and added rumble effects. An additional analog button turned the feature on or off for greater compatibility with past titles. The addition of dual analog sticks finally made a PlayStation controller ideal for nuanced movement and camera control in the newest generation of 3D games, like Tomb Raider III—Adventures of Lara Croft (1998, Eidos) and third-person platformer, Ape Escape (1999, Sony). In short, the DualShock was just the controller the PlayStation needed to secure its place in videogame history.

The Accessories

Besides the various Sony gamepad controllers, a variety of other add-ons and accessories were made for the PlayStation. Naturally, the most common accessories were various third-party controllers, including arcade sticks. Sony released two additional first party controllers that are worth mentioning: the Analog Joystick and PlayStation Mouse.

At the top of the photo is the Hori Fighting Stick PS; a Game-Enhancer from modchips.com, which plugs into the console’s PARALLEL I/O port, rests on top. Nyko’s Classic Trackball and Sony’s PlayStation Mouse and mouse pad are at the bottom of the photo.

The Analog Joystick featured two large button-laden flight sticks mounted on a base along with all eight of the standard action buttons, as well as select and start. A mode switch made the Analog Joystick function like a regular digital gamepad, with both sticks functioning as the directional pad. A thumb-operated hat switch on the right joystick functioned as a standard directional pad when in analog mode. About a dozen games, listed as “Analog Joystick Compatible,” were released, including appropriate titles like flight simulator, Ace Combat 2 (1997, Namco), and mech simulator, MechWarrior 2: 31st Century Combat—Arcade Combat Edition (1997, Activision).

Oddworld: Abe’s Exoddus (1998, GT Interactive)

Developed by Oddworld Inhabitants, Oddworld: Abe’s Exoddus was platform gaming as twisted as its spelling. Hearkening back to a time when platformers didn’t scroll, Abe’s Exoddus is broken up into discrete screens, which include challenging puzzles that must be solved using the titular character’s unique abilities to directly and indirectly control various objects. Abe discovers that the Glukkons are enslaving his fellow Mudokons to produce Soulstorm Brew, a drink that uses their bones and tears as ingredients. Naturally, you must put a stop to this. As well received as its equally atmospheric and eccentric predecessor, Oddworld: Abe’s Oddyssee (1997), Abe’s Exoddus added the crucial ability to save your progress at any point, resulting in far less frustration. Future installments in the Oddworld series entered the third dimension and were released on a wider variety of platforms, but many fans feel that these games were at the height of their charm on the PlayStation.

The PlayStation Mouse was a two-button ambidextrous mouse that came with a PlayStation-themed mouse mat. A few dozen or so titles supported the mouse, including adventure games, Broken Sword: The Shadow of the Templars (1998, THQ) and Discworld (1995, Psygnosis), and strategy games Dune 2000 (1999, Westwood Studios) and X-COM: UFO Defense (1995, MicroProse).

Light guns were also plentiful on the PlayStation. Besides Konami’s The Justifier, which only worked with a few games, there was Namco’s Guncon, which other companies shamelessly cloned. Guncon compatible games include Namco’s popular arcade conversions of Time Crisis (1997) and Point Blank (1998), as well as Working Design’s Elemental Gearbolt (1998) and Fox’s Die Hard Trilogy 2: Viva Las Vegas (2000), which featured third-person shooting, action driving, and light gun game modes.

Namco also released two specialty steering wheel controllers: neGcon and Jogcon. These were soon joined by an avalanche of other, more traditional steering wheel controllers that purported compatibility. The neGcon was a standard gamepad design with its right and left halves connected by a swivel joint, which registered analog movements. The Jogcon, which was initially bundled with R4: Ridge Racer Type 4 (1999), took a slightly more traditional approach and placed a force feedback dial at the bottom of the front of a standard gamepad design.

The PlayStation Multitap and its clones let up to four controllers and four memory cards connect to a single controller port on the console. While supported only by a few dozen games or so, most of the titles that would have benefited from its use supported it, including arcade sports classic NBA Jam TE (1995, Acclaim), competitive racer Rally Cross (1997, Sony), and combat racer Twisted Metal III (1998, 989 Studios).

Konami’s popular arcade dancing game Dance Dance Revolution was brought home to North American gamers in 2001, along with the Dance Dance Revolution controller, a plastic dance mat. Additional rhythm games from Konami and others followed, as did other types of dance mats, including more rigid designs that better mimicked the arcade experience.

The compact PSone with its optional 5-inch diagonal LCD screen attachment. The actual console is approximately the same width as the standard controller. Courtesy of Evan-Amos, Vanamo Media.

The small size of the PSone encouraged its own line of add-ons, including carrying cases and power adapters for use in a car. The most popular add-ons were LCD screens, with Sony themselves coming out with the best, a seamless 5-inch diagonal attachment that was also offered in a bundle with the console itself.

The Sony PlayStation Community Then and Now

Because it came from Sony and had an earlier Japanese launch to help provide context, the Play-Station received a good deal of attention from the gaming press in North America well before its release. NEXT Generation magazine in particular provided substantial coverage, which began in their first issue dated January 1995. Other popular magazines, such as Electronic Gaming Monthly and GameFan, also contributed to the buzz.

PaRappa the Rapper on the ePSXe emulator.

PaRappa the Rapper (1997, Sony)

Even though rhythm gaming has become a staple of casual gamers, the pioneering PaRappa the Rapper still stands out with its unique visuals, catchy soundtrack, and quirky plot. Players controlled the titular character—whose motto is, “I gotta believe!”—as he tries to win the heart of flower-girl Sunny Funny through six crazy stages. While really nothing more than a challenging game of “Simon Says,” PaRappa the Rapper’s seemingly endless charm will keep you coming back for more. Also be sure to check out the PlayStation Portable port released in 2007, the 2002 sequel for the PlayStation 2, as well as the PlayStation’s own follow-up, UmJammer Lammy (1999), which plays similarly, but instead features the sweet story of a shy lamb rock guitarist.

As the PlayStation’s popularity grew, it became feasible for publishers to launch dedicated magazines for fans to rally around. Magazines like Dimension PS-X, whose first issue appeared in November 1995, and PSM, which followed in September 1997, provided extensive PlayStation coverage for the steadily growing fan community, which was starting to rival that of Nintendo’s and exceeding that of a downward-trending Sega’s.

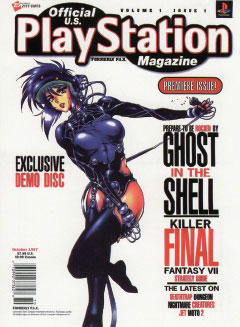

Of course, the magazine with the greatest impact was Official US PlayStation Magazine, whose first issue was dated October 1997. What set this magazine apart from its rivals was its bundled discs full of playable demos. Month-after-month, eager PlayStation gamers could sample exciting new games and see preview videos for future releases, building anticipation and free word-of-mouth advertising. The success of this model was clear to Sega and Microsoft, who bundled discs with their official magazines for Dreamcast and Xbox, respectively. Only Nintendo refused to jump on the demo disc bandwagon.

Official US PlayStation Magazine served the community for almost ten years, from its first issue dated October 1997, cover shown here, to its final issue dated January 2007. Every issue of the magazine came with a disc full of playable demos. PlayStation-specific demos lasted until issue 54, after which all further demo discs were targeted exclusively to the PlayStation 2.

Sony was also a pioneer in promoting indie game development. Sony released the Net Yaroze development kit for the PlayStation in Japanese, North American, and European/Australian variations in 1997. For less than $800, users could get a package containing a special black-colored PlayStation debugging console with two controllers, documentation, software, and no region lockout. Using a PC Windows- or Macintosh-based computer (as well as NEC PC-9801 in Japan), users could write code, compile it, and send the program to the debugging console for testing. Although purposely limited in comparison to the official PlayStation Software Developers Kit used by Sony’s commercial licensees, with the right skillset, commercial quality games could still be developed. In fact, one such game, puzzler Devil Dice (1998, Shift), was one of a handful of retail releases that started life as a Net Yaroze title.

While there has not been a lot of activity in PlayStation homebrew software outside of Net Yaroze projects, there is one homebrew hardware item of particular note. The PSIO, although still undergoing a great deal of additional development and revision, allows ISO images of PlayStation CDs to run from an SD card. Not only does this allow commercial software to run from an SD card, but should also help spur further homebrew software development.

Resident Evil: Director’s Cut (1997, Capcom)

Resident Evil: Director’s Cut was the special edition of the original, genre-defining survival horror classic from 1996 that spawned a multimedia empire. This version changes item and enemy placements and tweaks certain gameplay elements. As a bonus, the original version of the game was also included, along with an easier beginner’s mode, which less dexterous players will appreciate. Although it still has the original’s infamously campy voice acting and somewhat crude visuals, this game still has an amazing ability to scare, and is a fun glimpse into the genesis of the historically important game series. Also be sure to look out for the updated release of this game, labeled as the “Dual Shock Ver.,” featuring support for the DualShock controller’s analog joysticks and vibration, as well as a new symphonic soundtrack by Mamoru Samuragoch, replacing the original soundtrack by Makoto Tomozawa, Akari Kaida, and Masami Ueda.

Silent Hill on the ePSXe emulator.

Silent Hill (1999, Konami)

It’s hardly surprising that eventually a new series would give Resident Evil a run for survival horror fans’ money. More shocking was the fact that it only took about three years to release a solid alternative—not a mere clone, but a unique and equally compelling take on the genre. Silent Hill relied on the third-person perspective of Resident Evil, but added real-time 3D environments with liberal use of eerie fog and shadow. These techniques made the game much more frightening, but also much less demanding on the PlayStation hardware. Instead of playing a tough combat expert, players assumed the role of an everyman, Harry Mason, as he searches for his missing adopted daughter in the fictional American town of Silent Hill. Eventually, players stumble upon a cult conducting a ritual to revive a deity it worships, and in the process discover the true origins of Mason’s daughter. Depending upon the player’s in-game actions, there were five possible endings, including one intended as a joke.

Collecting and Emulating Sony PlayStation Systems

The earliest PlayStation games came in oversized cardboard or plastic game cases, the latter being the same type that Sega used for its Saturn games. After a few years, all Play-Station software came on standard CD jewel cases, including rereleases of some of the earlier titles. This makes the original long boxes more collectible, although not necessarily rare.

Early PlayStation games came in long cardboard or plastic cases, before eventually moving to standard CD jewel cases.

The earliest PlayStation model (with the audio out ports) has been compared to high-end CD players. As Jeff Day breathlessly described in an April 2007 review on www.sixmoons.com,

The Sony Playstation 1 SCPH-1001 is another giant killer that’s a darling of the audio underground. If you’re looking for audio sonic fireworks, the PS1 might not be your cup of tea but if you’re looking for an outstandingly musical digital front end that can play music better than just about every multi-kilobuck digital source, look no further—way recommended.7

While there’s considerable debate over the true fidelity of its sound output, the hype does tend to make the SCPH-1001 more collectible than the later models.

Syphon Filter on the ePSXe emulator.

Syphon Filter (1999, 989 Studios)

A third-person shooter, Syphon Filter did away with most of Metal Gear Solid’s stealth trappings to deliver an action game filled with a variety of hazards and puzzles spread over 13 missions. Players took on the role of Gabriel Logan and three other operatives, neutralizing terrorists and destroying a biological weapon before it threatens Washington, DC. Each operative contributed a different set of skills that must be properly leveraged to complete the high concept mission. The game’s concluding scene foreshadowed future games in the series, which, like many great PlayStation originals, continues to this day.

If you’re looking for maximum portability, however, the PSone’s combination of compatibility and low cost on the various auction sites makes it ones of the easier systems to acquire, though its value is much higher when bundled in its original combo package with the LCD screen. Third-party LCD screens are generally lower quality and as a result hold less value than Sony’s official offering. Net Yaroze systems are available for only slightly less than their original retail prices, and not always complete.

Of course, as described in Chapter 3.5, most of the early models of PlayStation 2 did a great job of playing PlayStation games, so that opens up even more possibilities. Perhaps the ultimate such console, though, are the original CECHBxx (20 GB) and CECHBAxx (60 GB) models of the PlayStation 3, which not only play PlayStation 3 discs, but also PlayStation 2 and PlayStation discs, all in hardware. Many PlayStation games are also available via software emulation on Sony’s PlayStation Portable, PlayStation 3, PlayStation Vita, and PlayStation 4 platforms via purchase from their respective digital stores. PlayStation Certified Android tablets and smartphones offer similar options. All of Sony’s offerings in this area also provide various configuration settings that allow the low resolution PlayStation games to look better on the higher resolution devices they’re being played on.

The ePSXe emulator showing the original Tomb Raider.

Besides Sony’s official offerings, two of the more popular unofficial emulators are pSX and ePSXe, both of which work with Windows-and Linux-based computers. A variety of other unofficial emulators are available for those and other platforms, including Android, with overall compatibility improving all the time.

1 “PlayStation,” NEXT Generation, Issue 1, January 1995, p. 42.

2 To be fair, they were also responsible for solid Apple IIGS adventure games Dream Zone (1988) and Keef the Thief (1989), but overall, their track record was mixed and certainly didn’t suggest their future greatness.

3 www.edge-online.com/features/making-playstation/5.

4 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_best-selling_PlayStation_video_games.

5 http://web.archive.org/web/20120609161621/http://scei.co.jp/corporate/data/bizdataps_e.html.

6 www.gamespot.com/news/sony-stops-making-original-ps-6146549.