CHAPTER OUTLINE

Acting as a Human Capital Treasurer

Help Employees Formulate Career Plans and Choose the Best Learning Modes

Create a Constellation of Learning Contacts

Help People Travel Multidirectional Career Paths

Providing Direct Development

Coach Effectively

Believe in People's Ability to Develop

Goal Setting and Performance Feedback

Build Self—Efficacy Through FAMIC Goal Setting

Reinforce FAMIC Goals with FITEMA Performance Feedback

In a televised speech on April 18, 1977, U.S. president Jimmy Carter delivered what he called "an unpleasant talk" about the energy crisis that he said threatened the country. He urged American citizens to view the effort required to overcome the problem as "the moral equivalent of war."[189] In so doing, the president was using a metaphor to dramatize the problem, convince Americans of its gravity, and galvanize them to action. Metaphors like this draw their power from the object of comparison. By referring to war, the president evoked images of sacrifice, hardship, effort, solidarity, and, ultimately, victory. These entailments enrich metaphors and make them coherent within the context of our knowledge and experience.[190]

Drawing on these same principles, we suggest that human capital treasurer is an apt metaphor for the role managers play in employee development. It brings a broad and instructive array of entailments. Like financial treasury, human capital treasury focuses on a valuable asset (not money, but rather employee knowledge, skills, talents, and behaviors). Like a corporate treasurer, a human capital treasurer has responsibility for custodianship and growth of those assets, not through cash and investment management but instead through insightful, individualized learning strategies. Most important, like a company treasurer, a manager grows and guides the investment of an asset he does not own, much as a company's treasurer husbands financial assets that belong to the organization's shareholders.

We frequently hear how, in these turbulent times, organizations expect their people to define and pursue their own human capital growth strategies. The tagline: employee self-development. The translation: don't expect our help in building your competencies. Employees have gotten the message. Almost three-quarters of the respondents to our 2010 global workforce study said that they, not their employers, hold the primary responsibility for career management. But only 55 percent said they feel comfortable taking on this responsibility. Moreover, employees consistently confirm that career development is a key driver of engagement and of the decision to remain with an organization over the long term.[191] The importance employees place on learning and development, coupled with inconsistent support and investment from organizations, creates an importance/performance gap. This breach yields an opportunity—a necessity, we would say—for managers to step in and play a key role in employee growth.

Indeed, we expect the manager's responsibility for employee development not to atrophy under the weight of economic pressure or corporate indifference, but rather to grow deeper and broader. We pose this challenge to managers: make growth of human capital assets a core part of your responsibility and an essential element of every employee's job. If learning isn't woven into the fabric of each employee's work experience, then that experience is incomplete.

Randy MacDonald, senior vice president of Human Resources at IBM, takes issue with the notion that organizations should adopt a laissez-faire attitude toward employee development. "I heard an HR person once say, 'your career is your responsibility.' Let me tell you something, the CFO, when he gives one of our line guys $3 billion to go build a new plant, he doesn't say, 'Go build the plant and do what you want with it.' No, that CFO and that line person are going to manage that asset."[192] We agree with McDonald's notion that, like the financial assets of a company, human capital deserves significant attention from managers and organizations.

To define the exemplary manager, and to determine where employee development should fall among that manager's priorities, salesforce.com, a leading cloud computing company, put this question on an employee survey: "If you were to imagine your ideal manager, in what areas would you want that manager to be most capable?" From a list of seventeen factors, employees chose "Help with career advancement" as the most important item on the ideal manager's to-do list. The second most important factor was "Giving you regular feedback on your performance." "Coaching you in ways that help you do your job better" and "Giving you autonomy to decide how best to do your work" were fourth and fifth on the list. Yes, employees said, they want the organization to invest more in learning and development programs. But they also said that they expect managers to work with them directly to help them advance on the strength of their competencies and their ability to function independently.[193]

Let's first consider how managers work at the contextual level, helping people find and exploit the organization's learning and career development resources.

Like a good treasurer, a manager must have a plan for asset growth. Looking ahead to the employee's next opportunities, identifying the learning required to take those steps, and suggesting the path forward—these form the core of manager responsibility for human capital development planning. Of course, all ways of learning are not created equal; some learning modes work better than others for certain purposes. To avoid misguided investments and wasted effort, managers must help employees match the mode with the type of learning needed. For instance, they need to know that:

Mentoring works well when people need to grasp the nuances of organizational culture, brainstorm career direction, or navigate internal politics. A mentor has less to offer, however, when the employee needs to acquire a specific skill rather than a bit of more general organizational wisdom.

Coaching can help with skill improvement, insofar as a coach can give targeted advice to help improve a particular aspect of performance.

Classroom training works well for picking up aspects of knowledge that don't require same-day application and for topics that call for little one-on-one contact between teacher and learner.

Just-in-time training, especially delivered electronically, can provide an efficient dose of knowledge on a specific topic.

On-the-job training (OJT) works in cases where hands-on application can accelerate learning and where the targeted skill can be acquired and used quickly. However, OJT requires supervisors and peers who have the time, inclination, and skill to pass on what they know.

Using projects for learning has a dual benefit—the project effort produces results and the individual gains practical skills and knowledge in the process. Employee and manager must jointly assess the individual's learning need, find a suitable project, set goals for learning and project output, monitor progress, and retrospectively assess the acquisition of skills and knowledge. They must also choose the next project with all this in mind.

As we saw in Chapter Five, work that combines abundant job resources with challenging expectations for performance promotes the growth of human capital. Managers can do a lot to ensure that jobs like these provide the maximum opportunity for employees to expand their skills and knowledge. Managers can also encourage contact with other workers who have useful information or solutions to problems. This informal transfer of insights works well when employees need to know about the short cuts, rules of thumb, inside sources of information, and common-sense applications that make things work. People can get it precisely when it's most valuable, from peers and managers they trust, through the learning style they prefer, and in the quantity they need and can absorb.[194]

Transfer to other functions—a special kind of on-the-job learning—requires that both employee and manager have the right goals in mind when contemplating the move. Spending time in another part of the organization can help people learn new techniques, enlarge their technical vocabularies, understand issues from other units' perspectives, and build personal networks. But the time spent traveling through the organization may also detract from a deeper focus on learning about one's primary functional area.

Communities of practice, the informal, emergent groups that tend to coalesce spontaneously around disciplines and areas of common interest, are great ways for people to confer, collaborate, share information, and teach each other. The price of admission is intellectual contribution; the payoff is the knowledge and insight available from a network of colleagues. Social media offer a way to accelerate community connections, with some users contributing to and becoming part of the content, and other users consuming it.

Counseling employees about how to select from this portfolio of options is becoming a needed-to-play competency for managers who aspire to act as effective human capital treasurers. Indeed, there is a relationship between employee engagement and preferred information sources for career advice. Table 6.1 shows those sources for a broad population of U.S. workers.

Highly engaged people turn to their supervisors for career planning help, and they look elsewhere almost as frequently, including to the network of contacts we discuss shortly. People who say their engagement is low will spend far more time searching the Internet or seeking career counsel from contacts outside the organization (perhaps because they know that's where they will soon find themselves).

Table 6.1. Highly Engaged Employees Seek Career Advice from People, not Tools

Source of Career Advice | High Engagement (%) | Low Engagement (%) |

|---|---|---|

Source: Driving Business Results Through Continuous Engagement: 2008/2009 WorkUSA Survey Report, Watson Wyatt Worldwide, 15. | ||

Immediate supervisor | 23 | 8 |

20 | 8 | |

Employee's research on the Internet or other sources | 19 | 44 |

External network of contacts | 14 | 21 |

Company-provided resources or tools | 13 | 4 |

People in the employee's work group | 11 | 14 |

Good managers, like good treasurers, will call on many sources to help with asset management and development. Working offstage, however, an effective manager need not always be the central player in delivering day-to-day development experiences.

The more we study how learning takes place in organizations, the more we understand that employees benefit from having access to multiple sources of advice, counsel, and knowledge. It's helpful from time to time to seek out a confidant, a peer, or a manager (other than the direct boss) to get off-the-record advice or have the occasional mea culpa conversation. A growing body of research suggests that having a constellation of developmental relationships benefits people far more than relying on a single source for coaching and mentoring. In a study of attorneys at prestigious New York law firms, researchers Monica Higgins and David Thomas from the Harvard Business School found that having an array of developmental contacts within the organization did more for young lawyers striving for partnership than did having a single, even senior and effective, mentoring contact. They concluded, "Our results show that while the quality of an individual's primary developmental relationship does affect short-term career outcomes such as work satisfaction and intentions to remain [with the firm], it is the composition of one's entire constellation of developers that accounts for longer term career outcomes such as organizational retention and career advancement."[195]

The research also made a point about the particular importance of a network of contacts in the current work environment: "In an era of organizational restructuring and globalization, it will become increasingly difficult for individuals to develop and maintain single sources of mentoring support. Both mentors' as well as protégés' careers are likely to be in flux.... Individuals will need to search for alternative sources of help as they navigate their careers."[196]

We can think of the constellation of development sources as a network of relationships with the primary manager as the central point (the pole star, if you will). The manager, in turn, helps create the constellation by making his contacts available to trusted employees. In the words of two researchers who have studied workplace networks, "The outcomes of this process for members [of managers' networks] ... are positive ... they are able to establish relationships similar to their leaders', resulting in the trust and respect of important contacts in the organization."[197] The social capital represented by these relationships constitutes an important class of job resources. We know from the job structure model in Chapter Four that such resources help people cope with a variety of job-related stresses that could affect an individual's work attitudes, performance, and career progress.

The late lamented vertical career path has gone the way of the dinosaur, the dodo, and the dollar cup of coffee. Some organizations still offer an upward, linear career path, but many of those have flattened the organizational hierarchy so much that career ladders have far fewer rungs than they once did. In place of the ladder, we have the multidirectional career configuration. Whereas the phrase "at a crossroads" once meant a potentially troubling career crisis, it's now a commonplace event in the lives of people for whom positive career movement can be up, sideways, or (temporarily) down. Managers stand at the intersections of those pathways, like cops directing traffic and helping employees choose the right direction.

If you're Cisco Systems, your matrix structure must influence how you envision individual development and career progression. Why would a networked company in the network business not view individual learning and career movement as an interconnected set of lattices and ladders? As far back as 2001, Cisco was putting in place the early forms of the matrix that now channels development energy for company products and individual careers alike. In that year's soft economy, the organization focused relentlessly on taking advantage of the downward trend in technology markets to exercise what John Chambers called a "breakaway strategy." The committees and cross-functional teams necessary to connect centralized functional units began to take shape.[198] But the organization also knew that engineers with customer familiarity and multiproduct engineering know-how would represent the most powerful coordinating mechanism the organization could have. Given the company's strategy, increasing the speed and effectiveness of internal employee movement took on a high strategic priority. It was not just a nice thing to do to appease restless people.

Nearly a decade later, the company has expanded its structural matrix, as we saw in Chapter Five. Organizational architectures like this lend themselves to a complementary career matrix. A multidirectional career approach is intended to build an organization's human capital by giving people flexibility in how they construct their long-term working lives. Employees map and pursue individualized learning experiences and career options along four dimensions:

Pace. How quickly an employee progresses to increasing levels of responsibility and authority

Workload. How much work is expected of an employee, typically measured in hours or days per week, month, or even year

Location and schedule. Where work gets done and when

Role. What capacity encompasses the individual's work, from individual contributor to senior leader[199]

As described by Cathleen Benko and Anne Weisberg, authors of Mass Career Customization, the how-to manual for constructing lattice-and-ladder career paths, "Employees and their managers partner to customize careers by selecting the option along each of the four dimensions that most closely matches the employee's career objectives, keeping in mind their life circumstances and the needs of the business at any given point in time."[200] Benko and Weisberg say that "MCC [mass career customization] requires a significant amount of time on the part of both managers and employees to engage in meaningful career conversations. MCC provides the structure, but managers need to buy into the business case and be appropriately recognized by leadership for taking the time required to execute MCC effectively. Trust is equally important in this process."[201]

Besides carving out time and building trust, helping an employee navigate a lattice-and-ladder career structure requires managers to:

Display sophisticated understanding of the production function and project/unit contribution to strategy. They must apply systems thinking to their project management, understanding how inputs and outputs interact. They must hold projects and processes together as people cycle onto and off of project work and into and out of career phases.

Span boundaries and establish their own networks in the organization. Managers must be able to navigate the organization, locating development resources and helping each employee find the right next opportunity.

Be creative in helping people craft individualized career strategies. Managers must be a direct source of development for employees, and also know when to focus development locally and when to guide them in looking elsewhere.

Show sensitivity to fairness across employees in the unit. With people crafting customized careers, managers must ensure that job and career elements fit the person and are equitable (though not necessarily identical) across the group.

Develop a command of organizational tools. Managers must be able to guide people to advanced organizational tools that help employees plot career paths. Genentech, for example, has created a catalogue of scientific disciplines, from antibody engineering to structural biology, and put it on the company Web site. Readers can peruse the biographies of researchers in each discipline at Genentech, learn about what they are currently working on and understand what inspires them, and find out what kind of people they are looking to recruit.

Evolving internal transfer approaches to teamwork, job mobility, and career movement have two goals: to make human capital growth an organization-wide effort, not a unit-specific one; and to afford employees the opportunity to have diverse, multicontact experiences that accelerate learning. Even in organizations that don't have matrix structures, such approaches can give employees a degree of career self-determination that is often absent in more conventional (and increasingly rare) vertical approaches to career progression. Cisco's Susan Monaghan, vice president of employee engagement, describes the organization's philosophy of career progression:

We want managers to think of our employees as Cisco talent, not their talent. Managers need to be willing to let good people move on in order to expand their careers and grow their skills. This will require us to see people beyond who they are in their current job and recognize them for past experiences and unique towering strengths. People are a sum total of all of this, and an individual's personal vision should not be bound by the current job description. The manager's job is to translate and connect what's good for the person with what's good for the company. Playing this role will require managers to step back from today's job and think about how to build sustainable talent for Cisco.[202]

Back in 2001, a Cisco career services manager described an incident that captured perfectly the desired manager behavior. "This week, a manager e-mailed the new manager about a person who was considering a transfer. He said, 'This guy is my absolute number one employee—his performance ratings have been consistently stellar. He can truly make a contribution to your team. I don't want to lose him, but I know this move is in his best interest, so call me if you have any questions.' When every manager in our company acts that way, then I know we'll be providing end-to-end career support."[203]

In a world where organizational focus on employee development has been compromised and learning investments threatened, managers' direct efforts to help people build their human capital take on increased urgency. An astute manager has a wide array of approaches at his disposal for engaging in direct human capital-building efforts with employees. These include:

Coaching. Providing hands-on skills-improvement advice and instruction by putting learning and action close together; encouraging performance, nurturing, and reinforcing success

Teaching. Imparting knowledge; learning and action may be separated by time and space

Informing. Providing information on specific job functions and broader organizational and strategic context

Mentoring. Giving the employee career guidance, general development counseling and advice, sponsorship, and support

Exemplifying. Displaying the desired attitudes and actions[204]

Managers may engage in any or all of these actions more or less constantly and without clear delineation of when one form of direct development stops and another begins. We will focus chiefly on coaching, the term we hear most often from our colleagues in Human Resources.

Plenty has been written about how managers should act as employee coaches. Indeed, when asked about the roles of managers, Human Resources people most often say that they expect their company's managers to coach employees. Participants in the Randstad World of Work survey chose "Being able to share my knowledge with others" as the number one reason for considering a managerial role.[205]

Social scientists who observe hunter-gatherer groups know that group leaders achieve and hold positions of power partly because they help individuals, and the group at large, to become more successful. They develop others' ability to find the best water hole rather than just leading people to it. Modern organizations expect the same from their managers. They call it coaching or training but rarely define what it means. Still, it's a rich idea, one that goes back to how learning occurs in environments where the next generation's ability to learn what the last generation knows is critical to the survival of the band.

We can imagine, for example, how the skilled leader of a hunting party might develop the knowledge and skills of less-experienced companions. To begin with, the learning would take place in the camp, as novices listen to hours of stories about foraging activities, and on the job, as they join hunts and learn from the coaching of experienced hunters and from their own mistakes.[206] Development would focus on critical skills: identifying animal prints; finding game; pursuing animals; shooting arrows or throwing spears; and making the kill. The manager-coach would:

Explain the importance of a successful hunt, providing basic information about the band's need for protein

Create practice opportunities, perhaps through spear-throwing or arrow-shooting contests, giving young hunters a chance to hone their skills before it really counted

Use the moment of performance to offer immediate advice (demonstrating the right way to throw a spear)

Give the novice hunter some autonomy in choosing how to go about the hunt, thereby improving decision making as well as motivation

Assess performance immediately, constantly, and objectively through a continuous dialogue about strategies, techniques, and results

Reinforce success through specific praise, commenting favorably on a good throw, even though the thrower might not have hit the target

Offer a near-term opportunity to improve (urging the hunter to find and pursue another antelope, after missing the last one)

Make the rewards for good performance and the downside of poor performance equally clear (bringing down the antelope provides dinner, not to mention praise and glory for the successful hunter; missing it means everyone goes hungry)

Our continuing theme of managing with a light touch pertains as well to these coaching elements. Employees want the ability to determine the moment of coaching, the amount they will receive, and the approaches used. Intrusive or heavy-handed efforts to compel learning produce more resentment than results.

Many managers say they don't have time to spend working with individuals and teams in this highly focused, attention-demanding process. For them, the kind of role restructuring discussed in Chapter Four could reshuffle the elements of the manager's job (for instance, permitting a larger allocation of time to people focus, perhaps supported by a reduced span of control) and provide the hours needed for effective direct (and indirect) employee development.

Such factors as inadequate time or insufficient ability certainly detract from the manager's capacity to coach effectively. But there may also be a simpler, more insidious obstacle: manager attitude. Some managers believe that it's possible to develop fundamental individual abilities, whereas others don't. Stanford psychology Professor Carol Dweck, who has studied the beliefs people hold about the changeability of personal characteristics, labels the two opposite attitudes entity, or fixed ability theory, and incremental, or malleable ability theory. Those who hold an entity theory believe that employees' most basic attributes are hardwired and largely resistant to change. Those who subscribe to the notion of malleability have a different attitude. They consider even basic qualities to be amenable to improvement.[207] In essence, Dweck says, between the immutable elements of an individual's portfolio of attributes (physical characteristics like color blindness, for instance) and the highly flexible ones (for example, the widespread ability to learn to ride a bicycle) lie what she calls "the levels in between."[208] These in-between attributes, which include a wide range of abilities and even personality characteristics, represent the disputed territory for holders of entity and incremental beliefs.

The differences play out in how managers evaluate employee performance and decide how and whether to invest effort in coaching. Studies by a team of researchers from Southern Methodist University (SMU) and the University of Toronto showed, for example, that managers who subscribe to the fixed-ability theory tend to resist adjusting their opinions about employees over time. They hold tight to their beliefs that employee ability is enduring and static, even if the individuals' actual performance improves or declines noticeably. In other words, their first impressions of people are "sticky." Because they don't really think people can change, they tend to ignore or discount evidence of performance adjustments.[209] In contrast, managers who believe in the efficacy of development show a much higher inclination to acknowledge performance changes. Beliefs about the probability of real change affect managers' willingness to invest effort in coaching employees. The stronger the belief in the plasticity and malleability of individual skills and attributes, the stronger the manager's inclination to put time and energy into building employees' skills and knowledge.[210]

So then, a key question: when managers believe their efforts will provide a meaningful boost to employee performance, what kind of coaching do they provide? Research and observation by Carol Dweck and others indicate that they tend to:

Observe employee work closely, and praise process, strategy, and effort first, results second, and talent not at all

Both challenge and nurture; they don't reassure people that they are "fine as they are," but instead dare them to do better

Tell people the truth about their performance and then give them the means to improve

Give people autonomy in how they want to develop their abilities[211]

Not only do these behaviors pay off in terms of performance, but they also tend to turn employees themselves into incremental theorists. In Dweck's words, referring to experiments with students, "When students are praised for their intelligence, they move toward a fixed theory. Far from raising self-esteem, this praise makes them challenge-avoidant and vulnerable, such that when they hit obstacles their confidence, enjoyment, and performance decline. When students are praised for their effort or strategies (their process) [italics in original], they instead take on a more malleable theory—they are eager to learn and highly resilient in the face of difficulty. Thus self-theories play an important (and causal) role in challenge seeking, self-regulation, and resilience, and changing self-theories appears to result in important real-word changes in how people function."[212]

Building people's belief in their ability to grow and adapt can have impressive results. One experiment, designed to test ways of increasing the resilience and self-confidence of minority college students, used a set of simple but powerful techniques. First, the students were taught that doubts about fitting in at college are common at first, but short-lived. They were presented with survey statistics and personal testimonies from upperclassmen to reinforce this idea. They wrote a speech, which they videotaped, explaining why people's perceptions of acceptance might change over time. Compared with a control group, African American students in the experimental group took more challenging courses, retained their motivation in the face of adversity, reached out to faculty members three times as often, and spent significantly more time studying each day. Students in the experimental group improved their grades in the semester following the intervention, whereas students in the control group saw their grades fall.[213]

Belief in the ability of individuals to learn and grow—or skepticism about that ability—can become a deeply embedded trait of organizational culture. Few organizations, however, have made development, especially the forms delivered by first-line managers, as critical a pivot point of organizational culture as has Yum! Brands. Yum! is the corporate umbrella for some of the most recognizable quick-service restaurant chains on earth. The company's operations include KFC, Pizza Hut, Taco Bell, and Long John Silver's. If you haven't eaten at one of these restaurants lately, then perhaps you haven't been to the mall recently. Or maybe you don't have teenage children.

In 1997, when the company launched itself following its spin-off from PepsiCo, it set about to change some of the cultural elements that had characterized the PepsiCo mother ship. Among other changes, Yum! inverted the organizational power pyramid. At PepsiCo, business took place in the restaurants, but true influence resided at the corporate headquarters. At the newly launched company, however, the RGM (Restaurant General Manager) was touted as "our #1 Leader ... not senior management." Corporate headquarters was rechristened the "Restaurant Support Center," to signify that the restaurants represented the operating center of the organization. Most significantly, the entire above-restaurant management team underwent title changes. Area managers became "area coaches," operations directors became "market coaches," and division vice presidents morphed into "head coaches."[214]

Changing titles was a nice symbolic step, but it would have meant little without operational backup. At Yum!, the process part began with a boot camp for the entire operations group. Managers went through a training regimen during which they relearned the basics of making and selling their food products. They had to pass a test and have their competence certified. While this was taking place, the company's organization development team created job maps and descriptions of the roles, responsibilities, behaviors, and expected outcomes of coaching actions. Finally, the company developed a simple model for coaching employees in a fast-paced, high-turnover business. It had three basic components: Exploring (observe what's going on, ask questions, and listen to the answers); Analyzing (look at the facts, figure out whether problems are isolated or systemic, find the root causes); and Responding (provide feedback, teach new skills, offer support, and gain commitment).[215]

Change efforts like these don't succeed without the energetic support of company executives. David Novak, chairman, president, and CEO of Yum! Brands, falls into that passionate supporter category. To begin with, he equates great leadership with great coaching. Second, he subscribes to an incrementalist development philosophy: "What I think a great leader does, a great coach does, is understand what kind of talent you have and then you help people leverage that talent so that people can achieve what they never thought they were capable of." Novak also believes in focusing development efforts on one person at a time: "The best leaders I've known really take an active interest in a person. And once that person demonstrates they have skill and capability, they try to help them achieve their potential. That's always been my thinking about management. If you have someone who's smart, talented, aggressive, and wants to learn, then your job is to help them become all they can be." He also seems to know that past performance is relevant chiefly as a springboard to future success: "I hate Monday-morning quarterbacks. So I try to focus my meetings on building and sharing know-how that will help us win going forward. I focus my meetings on beating last year."[216]

At Yum!, coaching by managers—all managers—has taken on a central role in the organization's quest for a competitive edge. Granted, operations like Yum! Brands restaurants succeed or fail for a variety of reasons. At Pizza Hut, for example, sales are heavily influenced by new product launches. But ultimately, efficient, cost-controlled operations and consistent product quality will carry the day in a crowded competitive field. And, though corporate operating manuals and policy guidelines can help a restaurant run efficiently, the most important determinant of performance will be the way a restaurant manager works with her staff to minimize waste, maintain product consistency, and keep customers happy.

For Yum!, the local focus seems to be working. During the first four years following the culture change effort, Pizza Hut experienced record results in same-store sales and historic lows in restaurant manager turnover.[217] In fiscal 2009, Yum! announced its eighth consecutive year of annual earnings-per-share growth of at least 10 percent.[218]

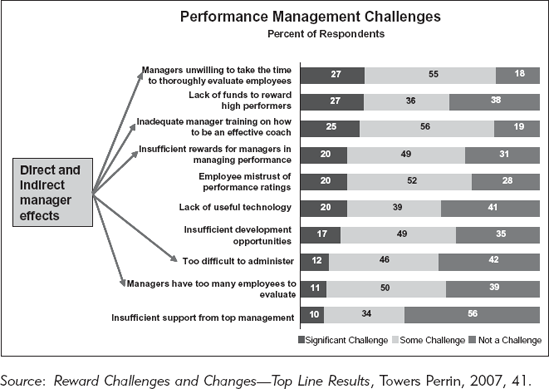

Among the many processes that managers implement and oversee, few produce as much frustration as goal setting and performance evaluation. Organizations lump these processes under the heading of "performance management." They speak of "managing" performance as if it involved following a simple recipe: start with a pinch of goal setting, add a splash of performance ratings, throw in a dash of rewards, don't forget just a soupçon of training, and voilà, a high-performing person. But people aren't cakes, and human performance is far too complex to be approached with a formula. Although setting goals and providing performance feedback build the foundation for development strategies and tactics, organizations continue to think of them as mechanical programs chiefly consisting of forms, schedules, rating schemes, and computerized systems. Among the participants in our Reward Challenges and Changes (RCC) survey, 43 percent said that their approaches to performance management are only somewhat effective or not at all effective. When asked about the principal challenges to effective performance assessment and improvement, survey respondents said that managers represent the most significant obstacle to success. Figure 6.1 shows that three of the top frustrations fall on the shoulders of managers.

The echoes of the manager role structure discussion of Chapter Four come through loud and clear. Managers don't have, or aren't willing to take, sufficient time to dispassionately assess employee performance, in part because they have too many other diverse tasks to perform and oversee. Sometimes, they also lack the human capital management abilities required to coach effectively. And notice the ninth factor in Figure 6.1—the familiar span of control bugaboo. More than 60 percent of the respondents to the RCC survey said having too many employees to evaluate is at least somewhat of a challenge for managers.

Employees also express frustration about managers' and companies' performance assessment and improvement efforts. In Towers Perrin's 2007 global workforce study, only half of the employee respondents said their managers provide performance goals that are challenging but achievable. Employees consistently tell us they want to have a continuous, informal dialogue about performance with their managers. Yet few organizations approach performance assessment this way. Among the RCC respondents, only 5 percent said their managers provide ongoing performance feedback. More than half make performance assessment an annual event.[219]

Further complicating the assessment and improvement process is the asymmetry of emotion to which people are prone. We experience negative emotions far more strongly than we experience positive ones. As a result, negative feedback, however constructive or well intended, produces an emotional reaction that interferes with the hoped-for self-improvement response. Emotional asymmetry thus works against one of the assumptions most fundamental to the performance management construct: that pointing out unmet goals should increase motivation and effort to close the gap between goals and performance. In the words of psychologist Nigel Nicholson, "The rationality of performance management systems means in practice a cool emphasis on areas of deviation from standard. The ideal of learning from failure is seldom achieved, not least because of the asymmetry of emotional reactions to positive and negative stimuli—the power of aversion is much greater than the power of reinforcement."[220]

Real performance improvement occurs only when managers undertake a performance assessment and improvement process that links past performance, self-efficacy, goal setting, and future performance. The keystone in this performance architecture is self-efficacy.

Think of self-efficacy as self-confidence with a thermonuclear boost. Stanford psychologist Albert Bandura defines self-efficacy this way: "Perceived self-efficacy refers to beliefs in one's capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce given attainments."[225] As to the importance of this cognitive construct, Bandura lays it out plainly: "Those who have a high sense of efficacy view situations as presenting realizable opportunities. They visualize success scenarios that provide positive guides for performance.... A high sense of efficacy fosters cognitive constructions of effective courses of action, and cognitive enactments of efficacious actions, in turn, strengthen efficacy beliefs."[226] We saw this effect with jobs that provide challenges and support resources, leading to success that increases confidence to execute and ownership of results.

The mutual reinforcement of performance and self-efficacy gives it much of its power and makes it relevant in the context of performance assessment and planning. The process works like this:

Effective performance—that is, achievement of personally meaningful goals—boosts self-efficacy to accomplish specific tasks.

Higher self-efficacy influences the next stage of goal setting, raising the targets, and sharpening the identification of future performance strategies.

These strategies produce even better future performance, sending self-efficacy still higher, further raising goals and enhancing performance strategies, which increases accomplishment by yet another increment.

The linkage of positive performance and self-efficacy creates a powerful force for individual, team, and organizational achievement. It puts a pinpoint focus on the manager's responsibility: use the goal-setting and evaluation process to put power behind self-efficacy.

The critical first element in this chain reaction is the setting of initial performance goals. Substantial evidence, both academic and practical, suggests that explicit, challenging goals enhance individual motivation. The higher a person's expectation that a certain behavior will achieve desired outcomes, the greater the motivation to perform the activity.[227] Conversely, goals that seem out of reach have little motivating power. Organizations often use "stretch" goals as a way to motivate people to accelerate their effort and therefore their achievement. Stretch goals seem like a handy shortcut, a way to get people to jump several performance levels at once. Their success depends on two underlying notions: first, that challenging objectives motivate; and second, that even if people fall short of achieving the goal, they will still feel a sense of accomplishment at having come close. The first premise is correct; the second, more dubious. In fact, motivation can't last without what Bandura calls "affirming accomplishments." Negative feedback, when it works at all, engenders performance motivation only when the discrepancy between past goals and past performance is relatively small. Supervisors and organizations alike should take the longer view, letting the combination of challenging but achievable goals and self-efficacy work to increase performance incrementally and steadily.

Many organizations train managers and employees to establish goals that follow the acronym SMART: specific, measurable, agreed-on (or attainable), realistic, and time-bound. These elements are fine as far as they go, but several other important criteria are missing. To make the most of the not inconsiderable energy that does, or should, go into setting goals and assessing progress, other criteria come into play. Effective goals—that is, goals that move both individual and organization up the ladder of improved performance—must not only be SMART but also FAMIC:

Few in number and focused. Too many goals produce confusion and contradiction. It's better to focus attention on a few important objectives than to dilute effort across many elements.

Aligned internally and organizationally. Goals shouldn't contradict each other or force employees to make impossible and conflicting choices. Many goal-setting exercises contain an unstated assumption: any goal that supports the organization's best interest must ipso facto confer a benefit on the individual. But is this always the case? An approach called empathy box analysis can help identify misalignment between organization and individual benefit and suggest how to establish a mutually advantageous target. Table 6.2 shows an example.

In this situation, the organization derives a clear benefit from increased sales volume and the greater revenue it produces. The organization assumes that the resulting higher commission for the sales representative will bring individual and company interests into alignment (cell 1). By the same token, a sales representative who sells less than her target will earn a lower commission, perceive herself out of sync with the organization's goals, and work hard to correct the shortfall (cell 3). But look at cells 2 and 4. In cell 2, selling more produces a clear downside for the individual. The company may shrink a lucrative territory or raise sales quotas. Either change would make it harder for the sales rep to hit future sales goals. And, as cell 4 suggests, selling less isn't entirely negative, at least in the short run. Quotas presumably remain the same, or may even drop, and the familiar sales territory will likely remain intact. The message of all this is: aligning individual and organizational benefits is both important and more difficult than it sometimes seems. To establish mutually reinforcing goals, managers must pay close attention to the subliminal twists and turns of employee interests.

Table 6.2. Individual and Organizational Goals Don't Automatically Align

Goal

Outcome for the Organization

Possible Outcomes for the Individual

Source: Adapted from Heslin, P. A., Carson, J. B., and VandeWalle, D., Practical Applications of Goal-Setting Theory to Performance Management, pheslin.cox.smu.edu, 93–95. Forthcoming in J. W. Smither (Ed.), Performance Management: Putting Research into Practice, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Sell more

Positive—higher revenue

1

Higher commission Feel rewarded

2

Increased sales quota Reduction of territory or reassignment to another territory Feel unappreciated, stressed

Sell less

Negative—lower revenue

3

Lower commission Feel pressure to work harder, more effectively

4

Status quo (if the sales shortfall isn't too great)Feel relieved

Mastery building. Gaining mastery over a craft is one of life's greatest sources of engagement and self-actualization. Goal setting contributes to mastery when tasks and the related expectations are broken down into incremental steps that become progressively more challenging. According to Albert Bandura, "People gain their satisfaction from progressive mastery of an activity rather than suspending any sense of success in their endeavors until the superordinate goal is attained."[228] Especially early in an individual's learning process, goals should be expressed in terms of skill development and knowledge acquisition ("learn to do x, become expert in y") rather than performance alone. As expertise improves and performance gets better along with it, challenging, high-expectation performance goals become appropriate. When fulfilling jobs incorporate mastery building, autonomy and competence can work like riders on a tandem bicycle, together powering intrinsic motivation.

Incremental. Taking maximum advantage of an individual's self-efficacy to raise aspirations and performance requires a manager to work with employees to set challenging but feasible goals. Goals should be expressed in workable increments and reviewed frequently. Small wins build big momentum. It's also easier for employees and managers alike to respond to minor setbacks before they become big ones.

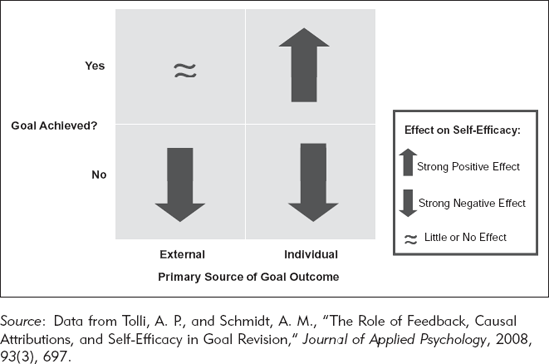

Controllable. In a complex organizational environment, achievement of goals will often depend on an array of factors, some within an individual's control, some at least partly outside the range of personal influence. Exhibit 6.1 shows how goal achievement (the vertical axis) and perceived control over achievement (the horizontal axis) interact to influence self-efficacy.

Self-efficacy reaches its highest level (the upper right-hand box) when an individual achieves his goals and perceives that those goals were largely under his individual control. Achievement of goals subject to substantial external influence (a strong economic environment, a competitor's failure, a lucky break) has little effect on individual self-efficacy. Failure to achieve the agreed-on goals, whether attributable to personal shortcomings or to external factors ("The sun got in my eyes, coach. That's why I dropped the ball.") tends to reduce self-efficacy. The upper right-hand quadrant is also where an individual is most likely to respond to a manager's performance feedback by increasing future goals and performance intentions.

Once goals are set, of course, they have little meaning without skillfully given feedback. As with goal setting, effective feedback requires adherence to a few key provisos. To reinforce self-efficacy and overcome the negative emotional reaction that bad news and perceived criticism often provoke, manager feedback on goal performance must be FITEMA:

Fairly determined. People must understand performance standards and have an opportunity to influence their determination. Employees must have confidence that the manager has knowledge of the employee's work, understands work-related goals, and knows why they were set where they were. Moreover, people must believe that the same performance standards apply to all employees in the group, receive a thorough explanation of evaluation results, and have a mechanism for challenging conclusions with which they disagree.

Individual, not comparative. People react best when they receive feedback framed against their individual performance in the context of goals, past achievements, or rate of improvement. Comparing one person to another elicits an ego-protection impulse that interferes with attention to improvement strategies.

Task-focused, not person-focused. Feedback carries the greatest cognitive power, and the lowest emotional drag, when concentrated on job performance and outcomes achieved, not on the character or the personality of the employee.

Error-tolerant. It is axiomatic that people can learn from their mistakes, but only when managers treat mistakes as opportunities to improve and not as signs of personal flaws. Our research shows that supervisors in high-performing organizations encourage people to learn from their shortfalls. This attitude is particularly important when novices are learning new skills. Managers can minimize harm to the organization by focusing employee efforts on incremental goals, so that errors are small and easily corrected in the next performance period.

Matched with the cadence of work. Feedback should come at the completion of a discrete unit of work: a week's production, a project completed, a month's worth of sales, or a year's output of new product research. This isn't to say that a good manager shouldn't monitor work constantly and engage in a continuous dialogue with employees. But a manager must tread a fine line between overobserving (second cousin to micromanagement) and remaining too distant. Employees working autonomously want to be left alone to do their jobs. Matching feedback with the rhythm of work gives the individual a chance to produce an output undistracted by over-the-shoulder oversight. By the same token, assessment of work products as those products are completed means that feedback comes with a proximate opportunity to put improvement advice to use in the next production cycle.

Action-oriented. Feedback has little meaning without plans for improvement. Pointing the feedback discussion toward concrete actions enhances goal achievement. Focusing on future improvement also gives the discussion a positive spin. This increases the likelihood an employee will walk out of the feedback session with a sense of optimism and a renewed energy to get it done the next time.[229]

Goal setting and results assessment that follow these principles give managers a platform for handling what many believe is their toughest challenge—dealing with poor performers. With specific, unambiguous, controllable goals, manager and employee should be able to agree on the causes of any performance shortfall. They can proceed to determine whether the issue lies with actual performance or with goals that, despite everyone's best efforts, were somehow unrealistic. With consistent dialogue and a focus on performance discrepancies as they arise, it should be possible to determine what needs to be addressed—employee competence, job demands and resources, external factors—to rectify performance concerns. This is not to suggest, however, that even an objective, fact-based assessment of performance deficiency will permit managers to avoid entirely the effects of emotional asymmetry. People simply react too strongly to bad news for that to be practical. However, by following the FAMIC and FITEMA precepts, managers give themselves and their employees the best possible chance to minimize the negative emotional effect.

We admit it—FAMIC and FITEMA may seem like a lot to handle. Still, we think it's worth the effort for managers to set goals and assess performance according to these guidelines. If this serving of acronym soup seems a bit too rich, then just keep in mind the words of psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. He says that maximum focused engagement in achieving goals (a state he calls "flow") "tends to occur when a person's skills [are] fully involved in overcoming a challenge that is just about manageable."[230] The message to managers, then, is this: spend the time to develop employees' skills, set goals that are within the individual's grasp but not too easy, increase them over time in manageable increments, and make sure that people control the resources and circumstances to achieve what they've agreed to do. Coordinating these efforts with development strategies and career path mapping yields a powerful and integrated process for building high-performance people and competitively strong organizations.

Brook Manville, consultant and former chief learning officer and customer evangelist of Saba Software, sees two main schools of thought on what managers can do to build human capital: "The first is a sort of engineering approach, the idea that managers can put in place tools, systems, processes, and infrastructure that can move the organization to predictable and measurable goals. The second is a sort of gardening approach, the idea that managers at most are creating context, environment, and nourishment for people to do the right thing, but that the outcomes are much less predictable and can only be influenced so far by managers." He thinks the evolution of the manager's role as human capital treasurer will take us to a point between the extremes: "As always, I think the next truth will lie somewhere in the middle. We will increasingly see both managerial intervention—new tools, new infrastructure, new systems—and at the same time a greater embrace within those new contexts of self-organizing, individual-empowering, culture- and values-driven approaches.... We will see an ongoing synthesis between engineering and gardening."[231]

Manville's manager-as-gardener image captures the dichotomy of caring and support without total control. A gardener weeds, fertilizes, and protects the plants from pests, but the plant ultimately grows on its own. Likewise, a manager helps an employee assess his or her needs, introduces learning sources, and nurtures the development of each individual's particular talents, skills, and knowledge. To evoke a less elegant metaphor, we can say the manager functions as an individual's developmental GPS, suggesting a direction, plotting a development course through the organization's geography, and guiding but not compelling a particular route to human capital growth.

The manager's development responsibilities take on different shadings depending on an organization's competitive focus. In a product-and-service differentiation strategy, managers must ensure that competency growth is fast and nimble, to keep up with a shifting competitive world. If operating efficiently forms the centerpiece of strategy, learning will often take place close to the job and emphasize finding better ways to do things. When customer attention dominates an organization's competitive intent, learning must help employees interpret and respond to customer requirements. Regardless of which strategy an organization pursues, however, our data indicate that a strong contribution by managers to employee development is a hallmark of high-performing companies (that is, organizations scoring in the top ranks of our global survey database for both financial performance and employee engagement). Among high-performing companies that have a differentiation strategy, 70 percent or more of employees agree or agree strongly with this statement: "My supervisor develops people's ability." By contrast, lower-performing companies get manager scores in the 50–60 percent range for this item. We see similar results among the groups that emphasize operating efficiency and customer focus, with scores approaching 80 percent for managers' development efforts among high-performing organizations, and scores 10 to 25 percent points lower for their poorer-performing competitors.[232]

Making employee growth and development into a contributor to competitive strategy requires managers to go beyond the typical definitions of coaching and advising. Strongly performing managers whose development efforts make a difference to competitive success will:

Not assume people's skills and attributes are largely fixed, but rather adopt the perspective that some dimensions of growth are feasible for most employees

Not merely show people how to do their jobs better or connect them with training courses, but instead work with employees to form imaginative development plans and create a wide network of internal and external learning contacts

Help people discover and travel diverse career paths, rather than merely discouraging them by saying that upward-sloping career vectors are unavailable

Not just coach people to improve skills, but rather coach in a way that reinforces autonomy and self-efficacy

Create an environment that nurtures human capital, rather than trying to engineer its growth

Not stop at SMART goals or manipulate with stretch objectives, but instead make sure that employees have FAMIC goals and receive FITEMA feedback with incrementally challenging performance targets

Perhaps more than any other role change, increasing a manager's allocation of time and energy to building employees' human capital alters not only the structure but also the main intent of the manager's job. The shift of attention to human capital treasury reinforces the emphasis on employee and team output and reduces the primacy of individual managerial production. Elevating the focus on building employees' intangible assets also lifts the manager's eyes from a myopic focus on today's performance and requires her to think as well about future production—because today's human capital is the intellectual foundation for tomorrow's competitive success. Here is how Cisco's Susan Monaghan expresses this idea, reflecting the employee perspective: "Managers should coach people to determine what's possible in the future, not just in how to do today's job. Managers must help people dream. We don't just want managers to help people go from point A to point B. We want managers to act almost as life coaches. This requires a one-to-one relationship with every employee and a one-to-one view. A career should be like a mini-tapestry, with threads running in multiple directions but creating an overall pattern."[233]