8 The Information Systems

Planning Process

Meeting the challenges of

information systems planning

Introduction

Strategic information systems planning (SISP) is a critical issue facing today's businesses. Because SISP can identify the most appropriate targets for computerization, it can make a huge contribution to businesses and to other organizations. Effective SISP can help organizations use information systems to implement business strategies and reach business goals. It can also enable organizations to use information systems to create new business strategies. Recent research has shown that the quality of the planning process significantly influences the contribution which information systems can make to an organization's performance.1 Moreover, the failure to carry out SISP carefully can result in lost opportunities and wasted resources.2

To perform effective SISP, organizations conventionally apply one of several methodologies. However, carrying out such a process is a key problem facing management.3

SISP also presents many complex technical questions. These deal with computer hardware, software, databases, and telecommunications technologies. In many organizations, as a result of this complexity, there is a tendency to let the computer experts handle SISP.

However, SISP is too important to delegate to technicians. Business planners are increasingly recognizing the potential impact of information technology, learning more about it, and participating in SISP studies despite their lack of technical experience.

This chapter defines and explains SISP. It illustrates four popular SISP methodologies. Then, based on a survey of 80 organizations, we discuss the problems of carrying out SISP. We also suggest some potential actions which business planners can take to deal with the problems.

What is SISP?

Information systems planning has evolved over the last 15 years. In the late 1970s, its primary objectives were to improve communication between computer users and MIS departments, increase top management support for computing, better forecast and allocate information system resource requirements, determine opportunities for improving the MIS department and identify new and higher payback computer applications.4

More recently, two new objectives have emerged. They are the identification of strategic information systems applications5– those that can give the organization a competitive edge – and the development of an organization-wide information architecture.6

While the importance of identifying strategic information systems applications is obvious, the importance of the organization-wide information architecture of information systems that share common data and communicate easily with each other is highly desirable. Just as new business ventures must mesh with the organization's existing endeavours, new systems applications must fit with the existing information architecture.

Unfortunately, an organization's commitment to construct an organization-wide information architecture vastly complicates SISP. Thus organizations have often failed to build such an architecture. Instead, their piecemeal approach has resulted in disjointed systems that temporarily solved minor problems in isolated areas of the organization. This has caused redundant efforts and exorbitant costs.

Thus, this chapter embraces two distinct yet usually simultaneously performed approaches to SISP. On one hand, SISP entails the search for high-impact applications with the ability to create an advantage over competitors.7 Thus, SISP helps organizations use information systems in innovative ways to build barriers against new entrants, change the basis of competition, generate new products, build in switching costs, or change the balance of power in supplier relationships.8 As such, SISP promotes innovation and creativity. It might employ idea generating techniques such as brainstorming,9 value chain analysis,10 or the customer resource life cycle.

On the other hand SISP is the process of identifying a portfolio of computer-based applications to assist an organization in executing its current business plans and thus realizing its existing business goals. SISP may mean the selection of rather prosaic applications, almost as if from a predefined list that would best fit the current and projected needs of the organization. These applications would guide the creation of the organization-wide information architecture of large databases and systems of computer programs. The distinction between the two approaches results in the former being referred to as attempting to impact organizational strategies and the latter as attempting to align MIS objectives with organizational goals.

Carrying out SISP

To carry out SISP, an organization usually selects an existing methodology and then embarks on a major, intensive study. The organization forms teams of business planners and computer users with MIS specialists as members or as advisors. It is likely to use the SISP vendor's educational support to train the teams and consulting support to guide and audit the study. It carries out a multi-step procedure over several weeks or months. The duration depends on the scope of the study. In addition to identifying the portfolio of applications, it prioritizes them. It defines databases, data elements, and a network of computers and communications equipment to support the applications. It also prepares a schedule for developing and installing them.

Organizations usually apply one of several methodologies to carry out this process. Four popular ones are Business Systems Planning11 PROplanner,12 Information Engineering,13 and Method/1.14 These will be described briefly as contemporary, illustrative methodologies although the four undergo continuous change and improvement. They were selected because, together, they accounted for over half the responses to the survey described later.

Business Systems Planning (BSP), developed by IBM, involves top-down planning with bottom-up implementation. From the top-down, the study team first recognizes its firm's business mission, objectives and functions, and how these determine the business processes. It analyses the processes for their data needs. From the bottom-up, it then identifies the data currently required to perform the processes. The final BSP plan describes an overall information systems architecture comprised of databases and applications as well as the installation schedule of individual systems. Table 8.1 details the steps in a BSP study.

BSP places heavy emphasis on top management commitment and involvement. Top executive sponsorship is seen as critical. MIS analyses might serve primarily in an advisory capacity.

PROplanner, by Holland Systems Corp. in Ann Arbor, Michigan, helps planners analyse major functional areas within the organization. They then define a Business Function Model. They derive a Data Architecture from the Business Function Model by combining the organization's information requirements into generic data entities and broad databases. They then identify an Information Systems Architecture of specific new applications and an implementation schedule.

Table 8.1 Description of BSP study steps

Enterprise Analysis The team documents the strategic business planning process and how the organization carries it out. It presents this information in a matrix for the executive sponsor to validate. |

Enterprise Modelling The team identifies the organization's business processes, using a technique known as value chain analysis, and then presents them in a matrix showing each's relationship to each business strategy (from the Enterprise Analysis). The team identifies the organization's entities (such as product, customer, vendor, order, part) and presents them in a matrix showing how each is tied to each process. |

Executive Interviews The team asks key executives about potential information opportunities needed to support their enterprise strategy (from the Enterprise Analysis), the processes (from the Enterprise Modelling) they are responsible for, and the entities (from the Enterprise Modelling) they manage. Each executive identifies a value and priority ranking for each information opportunity. |

Information Opportunity Analysis The team groups the opportunities by processes and entitles to separate ‘quick fix’ opportunities. It then analyses the remaining information opportunities, develops support recommendations, and prioritizes them. |

I/S Strategies and Recommendations The team assesses the organization's information management in terms of its information systems/enterprise alignment, ongoing information planning, tactical information planning, data management, and application development. It then defines new strategies and recommends them to executive management. |

Data Architecture Design The team prepares a high level design of proposed databases by diagramming how the organization uses its entities in support of its processes (entities and processes were defined during Enterprise Modelling) and identifying critical pieces of information describing the entities. |

Process Architecture Design The team prepares a plan for developing high priority applications and for integrating all proposed applications. It does this by tying business processes to their proposed applications. |

Existing Systems Review The team reviews existing applications to evaluate their technical and functional quality by interviewing users and information systems specialists. |

Implementation Planning The team considers the quality of existing systems (from the Existing Systems Review) and the proposed applications (from the Process Architecture Design) and develops a plan identifying those to discard, keep, enhance, or re-develop. |

Information Management Recommendations The team develops and presents a series of recommendations to help it carry out the plans that it prepared in Implementation Planning. |

PROplanner offers automated storage, manipulation, and presentation of the data collected during SISP. PROplanner software produces reports in various formats and levels of detail. Affinity reports show the frequencies of accesses to data. Clustering reports guide database design. Menus direct the planner through on-line data collection during the process. A data dictionary (a computerized list of all data on the database) permits planners to share PRO planner data with an existing data dictionary or other automated design tools.

Information Engineering (IE), by Knowledge Ware in Atlanta, provides techniques for building Enterprise Models, Data Models, and Process Models. These make up a comprehensive knowledge base that developers later use to create and maintain information systems.

In conjunction with IE, every general manager may participate in a critical success factors (CSF) inquiry, the popular technique for identifying issues that business executives view as the most vital for their organization's success. The resulting factors will then guide the strategic information planning endeavour by helping identify future management control systems.

IE provides several software packages for facilitating the strategic information planning effort. However, IE differs from some other methodologies by providing automated tools to link its output to subsequent systems development efforts. For example, integrated with IE is an application generator to produce computer programs written in the COBOL programming language without handcoding.

Method/1, the methodology of Andersen Consulting (a division of Arthur Andersen & Co.), consists of ten phases of work segments that an organization completes to create its strategic plan. The first five formulate information strategy. The final five further formulate the information strategy but also develop action plans. A break between the first and final five provides a top management checkpoint and an opportunity to adjust and revise. By design, however, a typical organization using Method/1 need not complete all the work segments at the same level of detail. Instead, planners evaluate each work segment in terms of the organization's objectives.

Method/1 focuses heavily on the assessment of the current business organization, its objectives, and its competitive environment. It also stresses the tactics required for changing the organization when it implements the plan.

Method/1 follows a layered approach. The top layer is the methodology itself. A middle layer of techniques supports the methodology and a bottom layer of tools supports the techniques. Examples of the many techniques are focus groups, Delphi studies, matrix analysis, dataflow diagramming and functional decomposition. FOUNDATION, Andersen Consulting's computer-aided software engineering tool set, includes computer programs that support Method/1.

Besides BSP, PRO planner, IE and Method/1, firms might choose Information Quality Analysis,15 Business Information Analysis and Integration Technique,16 Business Information Characterization Study,17 CSF, Ends/Means Analysis,18 Nolan Norton Methodology,19 Portfolio Management,20 Strategy Set Transformation,21 Value Chain Analysis, or the Customer Resource Life Cycle. Also, firms often select features of these methodologies and then, possibly with outside assistance, tailor their own in-house approach.22

Problems with the methodologies

Planners have long recognized that SISP is an intricate and complex activity fraught with problems.23 Several authors have described these problems based on field surveys, cases, and conceptual studies. An exhaustive review of their most significant articles served as the basis of a comprehensive list of the problems for our research.

To organize the problems, we classified them as tied to resources, process, or output. Resource-related problems address issues of time, money, personnel, and top management support for the initiation of the study. Process-related problems involve the limitations of the analysis. Output-related problems deal with the comprehensive and appropriateness of the final plan. We derived these categories from a similar scheme used to define the components of IS planning. (Research Appendix 1 lists the problems studied in the surveys, cases and conceptual studies. The problems have been paraphrased, simplified, and classified.)

A survey of strategic information systems planners

To understand better the problems of SISP, we developed a questionnaire with two main parts. In the first part, respondents identified the methodology they had used during an SISP study. They also rated the extent to which they had encountered each of the aforementioned problems as ‘not a problem’, ‘an insignificant problem’, ‘a minor problem’, ‘a major problem’, or ‘an extreme problem’. Similar studies have used this scale.

The second part asked about the implementation of plans. Planners indicated the extent to which different outputs of the plan had been affected. This conforms to the recommendation that a criterion for evaluating a planning system is the extent to which the final plan actually guides the strategic direction of an organization. In this part, the subjects also answered questions about their satisfaction with various aspects of the SISP experience.

We mailed the questionnaire to 251 organizations in two groups. The first included systems planners who were members of the Strategic Data Planning Institute, a Rockville, Maryland group under the auspices of Barnett Data Systems. The second was another group of systems planners.24

While 163 firms returned completed surveys, 80 (or 32 per cent) had carried out an SISP study and they provided usable data. Considering the length and complexity of the questionnaire, this is a high response rate.

Evidence of SISP problems: carrying out plans

In general, the respondents were fairly satisfied with their SISP experience. Their average rating for overall satisfaction with the SISP methodology was 3.55 where a neutral score would have been 3.00 (on the scale of zero to six in which zero was ‘extremely dissatisfied’ and six was ‘extremely satisfied’). Satisfaction scores for the different dimensions of SISP were also only slightly favourable. Satisfaction was 3.68 with the SISP process, 3.38 with the SISP output, and 3.02 with the SISP resource requirements.

However, satisfaction with the carrying out of final SISP plans was lower (2.53). In fact, only 32 per cent of respondents were satisfied with the extent of carrying them out while 53 per cent were dissatisfied. Table 8.2 summarizes the respondents’ satisfaction with these aspects of the SISP.

Table 8.2 Overall satisfaction with SISP

|

Average |

Satisfied |

Neutral |

Dissatisfied |

The methodology |

3.55 |

54% |

23% |

23% |

The resources |

3.02 |

38% |

24% |

38% |

The process |

3.68 |

48% |

7% |

5% |

The output |

3.38 |

55% |

17% |

28% |

Carrying out the plan |

2.53 |

32% |

15% |

53% |

Further evidence focusing on the plan implementation problem stems from the contrast between the elapsed planning horizon and the degree of completion of SISP recommended projects. The average planning horizon of the SISP studies was 3.73 years while an average of 2.1 years had passed since the studies’ completion. Thus, 56 per cent of the planning horizons had elapsed. However, out of an average of 23.4 projects recommended in the SISP studies, only 5.7 (24 per cent) had been started. Hence, it appears that firms were failing to start projects as rapidly as necessary in order to complete them during the planning horizon. There may have been insufficient project start-ups in order to realize the plan.

In addition to not starting projects in the plan, organizations instead had begun projects that were not part of their SISP plan. These latter projects were about 38 per cent of all projects started during the 2.1 years after the study.

Actions for planners

Below are the 18 most severe problems – which at least 25 per cent of the respondents described as an ‘extreme’ or ‘major’ problem. Because each can be seen as closely tied to Leadership, Implementation, or Resource issues, they are categorized into those three groups. They are then ordered within the groups by their severity. (Research Appendix 2 ranks all of the reported problems. The ‘Extreme or Major Problem’ column in the table shows the percentage of subjects rating the problem as such. The ‘Minor Problem’ displays the similar percentage. Subjects could also rate each as ‘Insignificant’ or ‘Not a Problem’.)

We offer an interpretation of each problem and suggestions to both top management and other business planners considering an SISP study. Many of the suggestions are based on the successful SISP experiences of Raychem Corp., a world-wide materials sciences company based in Menlo Park, California with over 10 000 employees in 41 countries. Raychem conducted SISP studies in 1978 and 1990.25 The company thus had the chance to carry out and implement an SISP study, and to learn from the experience.

The interpretations and suggestions provide a checklist for debate and discussion, and eventually, for improved SISP.

Leadership issues

It is Difficult to Secure Top Management Commitment for Implementing the Plan (No. 1 – the Most Serious – of the 18)

Over half the respondents called this an extreme or major problem. It means that once their study was completed and in writing, they struggled to convince top management to authorize the development of the recommended applications. This is consistent with the percentages in the previous section.

Such a finding suggests that top management might not understand the plan or might lack confidence in the MIS department's ability to carry it out. It thus suggests that top management carefully consider its commitment to implementing a plan even before authorizing the time and money needed to prepare the plan.

Likewise, planners proposing an SISP study should assess in advance the likelihood that their top management will refuse to fund the newly recommended projects. They may also want to determine tactics to improve the likelihood of funding. In Raychem's 1978 study, the CEO served as sponsor and hence the likelihood of implementing its findings was substantially improved.

The Success of the Methodology is Greatly Dependent on the Team Leader (No. 3)

If the team leader cannot convince top management to support the study or cannot obtain a top management mandate to convince functional area management and MIS management to participate, the study is probably doomed. The team leader motivates team members and pulls the project along. The team leader must be a respected veteran in the organization's business and a dynamic leader comfortable with current technology.

Organizations should reduce their dependency on their team leader. One way to do so is by using a well-structured and well-defined methodology to simplify the team leader's job. Likewise, by obtaining as much visible, top management support as possible, the organization will depend less on the team leader's personal ties to top management. In Raychem's case, dependency on the team leader was reduced because the team consisted of members with broad, corporate rather than parochial, departmental views. Such members can enable the team leader to serve as a project manager rather than force the individual to be a project champion.

It is Difficult to Find a Team Leader who Meets the Criteria Specified by the Methodology (No. 4)

As with the previous item, management will have to look hard to find a business-wise and technology-savvy leader. Such people are scarce. Management must choose that person carefully.

It is Difficult to Convince Top Management to Approve the Methodology (No. 8)

It is not only difficult to convince top management to implement the final plan (as in the first item above) but also difficult to convince top management to even fund the initial SISP study. SISP is slow and costly. Meanwhile, many top managers want working systems immediately, not plans for an uncertain future. Thus, advocates of SISP should prepare convincing arguments to authorize the funding of the study.

In Raychem's case, four executives – including two vice presidents – from different areas of the firm met several times with the CEO in 1978. Because he felt that information technology was expensive but was not sufficiently providing him with the information required to run the company, the executives were able to convince him to approve the SISP study and be its sponsor.

Implementation issues

Implementing the Projects and the Data Architecture Identified in the Plan Requires Substantial Further Analysis (No. 2)

Nearly half the respondents found this an extreme or major problem. SISP often fell short of providing the analysis needed to start the design and programming of the individual computer applications. The methodology did not provide the specifications necessary to begin the design of the recommended projects. This meant duplicating the investigation initially needed to make the recommendations.

This result suggests that prospective strategic information systems planners should seek a methodology that provides features to guide them into implementation. Some vendors offer such methodologies. Otherwise, planners should be prepared for the frustrations of delays and duplicated effort before seeing their plans reach fruition.

In Raychem's case, the planners drew up a matrix showing business processes and classes of data. The matrix reduced the need for further analysis somewhat by helping the firm decide the applications to standardize on a corporate basis and those to implement in regional offices. As another means of reducing the need for more analysis, Raychem set up model databases for all corporate applications to access.

The Methodology Fails to Take into Account Issues Related to Plan Implementation (No. 7)

The exercise may produce an excellent plan. It may produce a list of significant, high-impact applications.

However, as in earlier items, the planning study may fail to include the actions that will bring the plan to fruition. For example, the study might ignore the development of a strategy to ensure the final decisions to proceed with specific applications. It might fail to address the resistance of those managers who oppose the plan.

Again, planners need to pay careful attention to ensure that the plan is actually followed and not prematurely discarded.

The Documentation does not Adequately Describe the Steps that Should be Followed for Implementing the Methodology (No. 12)

The documentation describing some proprietary SISP methodologies is inadequate. It gives insufficient guidance to planners. Some of it may be erroneous, ambiguous, or contradictory.

Planners who purchase a proprietary methodology should read its documentation carefully before signing the contract. Planners who develop their own methodology should be prepared to devote significant energy to its documentation.

In Raychem's case, it chose BSP in 1978 simply because there were no other methodologies at the time. For its 1990 study, Raychem planners interviewed a number of consulting companies with proprietory methodologies before choosing the Index Group from Boston. Raychem then used extensive training to compensate for any potential deficiencies in the documentation.

The Strategic Information Systems Plan Fails to Provide Priorities for Developing Specific Databases (No. 13)

Both top management and functional area management must agree with the plan's priorities. For example, they must concur on whether the organization builds a marketing database, a financial database, or a production database. They must agree on what to do first and what to delay.

Without top management agreement on the priorities of the targeted databases, the plan will never be executed. Without functional area management concurrence, battles to change the priorities will rage. Such changes can result in temporarily halting ongoing projects while starting others. One risk is preeminent: Everything is started but nothing is finished.

Planners should be certain that the plan stipulates priorities and that top management and functional area management sincerely accept them.

Raychem approached this problem by culling 10 agreed upon, broad initiatives from 35 proposals in the 1990 study. Instead of choosing to establish database priorities during the study, it later established priorities for the numerous projects spawned by the initiatives.

The Strategic Information Systems Plan Fails to Determine an Overall Data Architecture for the Organization (No. 14)

Although the major objective of many SISP methodologies is to determine an overall data architecture, many respondents were disappointed with their success in doing so. They were disappointed with the identification of the architecture's specific databases and with the linkages between them. To many respondents, despite the huge effort, the portfolio of applications may appear piecemeal and disjointed.

Although these may appear to be technical issues, planners should still understand major data architecture issues and should check to be sure that their SISP will provide such an overall, integrated architecture, and not just a list of applications.

The Strategic Information Systems Plan Fails to Sufficiently Address the Need for Data Administration in the Organization (No. 18)

Because long-range plans usually call for the expansion of databases, the need for more data administration personnel – people whose sole role is ensuring that databases are up and working – is often necessary. In many organizations, the data administration function has grown dramatically in recent years. It may continue to expand and the implications of this necessary growth can be easy to ignore. Planners should thus be sure that their long-range plan includes the role of data administration in the organization's future. In Raychem's case, a data administration function was established as a result of its 1978 study.

Resource issues

The Methodology Lacks Sufficient Computer Support (No. 5)

SISP can produce reams of reports, charts, matrices and diagrams. Planners cannot manage that volume of data efficiently and effectively without automated support.

When planners buy an existing methodology, they should carefully scrutinize the vendor's computer support. They should examine the screens and reports. On the other hand, if they customize their own methodology, they must be certain not to underestimate the need for such support. In some organizations, the expense of developing computer support in-house might compel the organization to then buy an existing methodology rather than tailor its own.

The Planning Exercise Takes Very Long (No. 6)

The study takes weeks or even months. This may be well beyond the span of attention of many organizations. Too many business managers expect results almost immediately and lose interest if the study drags on. Moreover, many organizations undergo major changes even during the planning period.

Most importantly, an overrun during the planning exercise may reduce top management's confidence in the organization's ability to carry out the final plan. Hence planners should strive to keep the duration of the planning study as short as possible.

Raychem's 1978 study required three months but its 1990 study required nine. In 1990, planners chose to risk the consequences of a longer study because it enabled them to involve more senior level executives albeit on a part-time basis. Planners could have completed a briefer study with lower level executives on a full-time basis. However, the planners felt the study under such circumstances would have been less credible. They clearly felt that the potential problem of insufficient top management commitment described above was more serious than the problem of a lengthy study!

The Strategic Information Plan Fails to Include an Overall Personnel and Training Plan for the MIS Department (No. 8)

Many MIS departments lack the necessary skills to carry out the innovative and complex projects recommended by an SISP study. A strategic information systems plan thus needs to consider new personnel to add to the MIS Department. The SISP study will probably recommend additions to existing positions, permanent information systems planners, and a variety of such new positions as expert systems specialists, local area and wide area network specialists, desktop-publishers, and many others. An SISP study also often recommends training current MIS staff in today's personal computer, network, and database technologies.

Planners will need to be certain that their study accurately assesses current MIS department skills and staffing. They will also need to allocate the time and resources to ensure the presence of critical new personnel and the training of existing personnel. Raychem included a statement supporting such training in its 1990 study.

It is Difficult to Find Team Members who Meet the Criteria Specified by the Methodology (No. 10)

Qualified team members, in addition to team leaders (as in an earlier item above), are scarce. Team members from functional area departments must feel comfortable with information technology while computer specialists need to understand the business. Both need excellent communication skills and must have the time to participate. Hence, management should check the credentials of their team members carefully and be certain that their schedules allow them to participate fully in the planning process.

To find qualified team members, Raychem's planners in its 1990 study first drew up lists of business unit functions and geographical locations. They used it to identify a mix of team members from a variety of units in various locations. World-wide, senior managers helped identify team members who would be seen as leaders with objective views and diverse backgrounds. Such team members made the final study more credible.

The Strategic Information Systems Plan Fails to Include an Overall Financial Plan for the MIS Department (No. 11)

Responsible top management frequently demands financial justification for new projects. Because computer projects appear different from other capital projects, planners might treat them differently. Because top management will scrutinize and probably challenge costs and benefits in the long-range plan, planners must be sure that any costs and benefits are defensible.

In 1990, Raychem did not provide specific cost and benefit figures because of its concern that technological change would render them inaccurate later on. However, the firm did use various financial tests to reduce its initially suggested initiatives from 35 to 10. Moreover, planners did cost justify individual projects as they were spawned from the initiatives.

The Planning Exercise is Very Expensive (No. 15)

The planning exercise demands an exorbitant number of hours from top management, functional area management, and the MIS department. These are often the organization's busiest, most productive, and highest paid managers, precisely the people who lack the time to devote to the study.

Hence, management must be convinced that the planning study is both essential and well worth the time demanded of its top people.

The Strategic Information Systems Plan Fails Sufficiently to Address the Role of a Permanent MIS Planning Group (No. 16)

Like general business planning, strategic systems planning is not a one-time endeavour. It is an ongoing process where planners periodically review the plan and the issues behind it. Many information systems planners feel that a permanent planning group devoted solely to the information systems is essential, but that their planning endeavours failed to establish one.

As with many other planning efforts, planners should view the SISP exercise as an initial effort in an ongoing process. They should also consider the need for a permanent planning function devoted to SISP. In Raychem's 1978 study, the company formed a planning committee of executives from around the company. In their 1990 study, the management refined their procedures to ensure that planning committee members would serve as sponsors of each of the 10 initiatives and that they also report progress on them to the CEO.

Many Support Personnel are Required for Data Gathering and Analysis During the Study (No. 17)

To understand the current business processes and information systems support, many staff members must collect and collate data about the organization. Planners are concerned about their time and expense.

Planners should be sceptical if the vendor of a methodology suggests that staff support will be negligible. Moreover, planners may want to budget for some surplus staff support. Raychem controlled the cost of data gathering and analysis by having team members gather and analyse the data in the business units with which they were familiar.

Implications

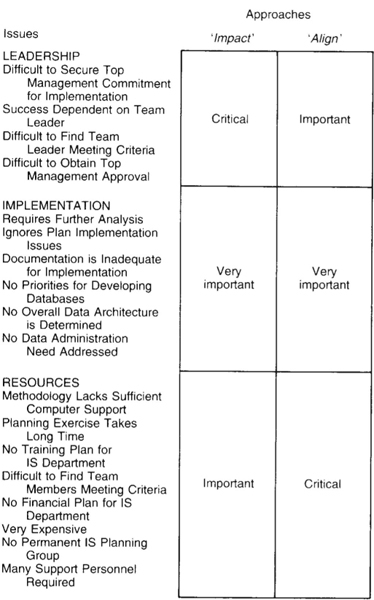

There are two broad approaches to SISP. The impact approach entails the identification of a small number of information systems applications that can give the organization a competitive edge. It involves innovation and creativity in using information systems to create new business strategies by building barriers against new entrants, changing the basis of competition, generating new products, building in switching costs, or changing the balance of power in supplier relationships.

The align approach entails the development of an organization-wide information architecture of applications to guide the creation of large databases and computer systems to support current business strategies. It typically involves identifying a larger number of carefully integrated conventional applications that support these strategies.

Some organizations may attempt to follow both approaches equally while others may follow one more so than the other. Thus the two approaches suggest that perhaps the different groups of problems may carry different weights during the SISP process. The matrix in Figure 8.1 shows the approaches, categories with summarized problem statements, and weights in each cell.

For example, when seeking new and unconventional applications under the impact approach, leadership may play a more critical role. Without experienced, articulate and technology savvy leadership in the SISP study, it may be difficult to convince top management to gamble on radical innovation. This does not suggest that leadership is unimportant when attempting to plan applications for alignment but rather that it may be more critical under the impact approach.

Because the align approach typically affects larger numbers of lower-level employees, the potential for resource problems is perhaps greater. The possible widespread effects increase the complexity of the align approach. Thus resource issues are probably of more critical concern in this approach.

Finally, regardless of whether the approach is ‘impact’ or ‘alignment’, implementation is still often perceived as the key to successful SISP. Thus whether an organization is attempting to identify a few high-impact applications or many integrated and conventional ones, implementation issues remain equally important.

Figure 8.1 Where information systems planning fails

Conclusion

Effective SISP is a major challenge facing business executives today. It is an essential activity for unlocking the significant potential that information technology offers to organizations. This chapter has examined the challenges of SISP.

In summary, strategic information systems planners are not particularly satisfied with SISP. After all, it requires extensive resources. Top management commitment is often difficult to obtain. When the SISP study is complete, further analysis may be required before the plan can be executed. The execution of the plan might not be very extensive. Thus, while SISP offers a great deal – the potential to use information technology to realize current business strategies and to create new ones – too often it is not satisfactorily done.

In fact, despite its complex information technology ingredient, SISP is very similar to many other business planning endeavours. For this reason alone, the involvement of top management and business planners has become increasingly indispensable.

References

1 G. Premkumar and W. R. King. Assessing strategic information systems planning. Long Range Planning. October (1991).

2 W. R. King. How effective is your information systems planning? Long Range Planning. 21(5), 103–112 (1988).

3 A. L. Lederer and A. L. Mendelow. Issues in information systems planning. Information and Management. pp. 245–254. May (1986); A. L. Lederer and V. Sethi. The implementation of strategic information systems planning methodologies. MIS Quarterly. 12(3), 445–461. September (1988); and S. W. Sinclair. The three domains of information systems planning. Journal of Information Systems Management. 3(2), 8–16. Spring (1986).

4 E. R. McLean and J. V. Soden. Strategic Planning for MIS. John Wiley and Sons. Inc. (1977).

5 PRISM. Information systems planning in the contemporary environment final report. December (1986). Index Systems. Inc. Cambridge, MA and M. R. Vitale, B. Ives and C. M. Beath. Linking information technology and corporate strategy an organizational view. Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Information Systems. pp. 265–276. San Diego. CA. 15–17 December (1986).

6 R. Moskowitz. Strategic systems planning shifts to data-oriented approach. Computerworld. pp. 109–119, 12 May (1986).

7 E. K. Clemons. Information systems for sustainable competitive advantage. Information and Management. 1(3), 131–136. October (1986). B. Ives and G. Learmonth. The information system as a competitive weapon. Communications of the ACM. 27(12), 1193–1201. December (1985). F. W. McFarlan. Information technology changes the way you compete. Harvard Business Review. 62(3), 98–103. May–June (1984). G. L. Parsons. Information technology: a new competitive weapon. Sloan Management Review. 25(1), 3–14. Fall (1983): and C. Wiseman. Strategy and Computer Information Systems as Competitive Weapons. Dow Jones-Irwin, Homewood. IL (1985).

8 M. E. Porter. Competitive Advantage Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance. New York, Free Press (1985).

9 N. Rackoff, C. Wiseman and W. A. Ulrich. Information systems for competitive advantage and implementation of planning process. MIS Quarterly. 9(4), 285–294. December (1985).

10 M. E. Porter. Competitive Advantage Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance. Free Press, New York (1985).

11 IBM Corporation. Business Systems Planning – Information Systems Planning Guide, Publication No GE20 0527–4 (1975).

12 Holland Systems Coporation. 4FRONT strategy Method Guide. Ann Arbor. MI (1989).

13 J. Martin. Strategic Information Planning Methodologies. Prentice-Hall Inc. Englewood Cliffs. NJ (1989).

14 Andersen Consulting. Foundation Method/1 Information Planning. Version 8.0. Chicago. IL (1987).

15 J. R. Vacca. IBM's information quality analysis. Computerworld. 10 December (1984).

16 W. M. Carlson. Business information analysis and integration technique (BIAIT) a new horizon. Data Base. 3–9. Spring (1979).

17 D. V. Kerner. Business information characterization study. Data Base. 10–17, Spring (1979).

18 J. C. Wetherbe and G. B. Davis. Strategic Planning through Ends/Means Analysis. MISRC Working Paper. 1982. University of Minnesota.

19 R. Moskowitz. Strategic systems planning shifts to data-oriented approach. Computerworld. pp. 109–119, 12 May (1986).

20 F. W. McFarlan. Portfolio approach to information systems. Harvard Business Review. 59(5), 142–150, September–October (1981).

21 W. R. King. Strategic planning for management information systems. MIS Quarterly. pp. 27–37, March (1978).

22 C. H. Sullivan Jr. An evolutionary new logic redefines strategic systems planning. Information Strategy. The Executive's Journal. 3(2), 13–19. Winter (1986).

23 F. W. McFarlan. Problems in planning the information system. Harvard Business Review. 49(2), 75–89, March–April (1971).

24 J. R. Vacca. BSP How is it working? Computerworld. March (1983).

25 Interviews with Paul Osborn, an executive at Raychem, who provided details about the firm's SISP experiences.

Related reading

M. Hosoda, CIM at Nippon Seiko Co. Long Range Planning. 23(5), 10–21 (1990).

G. K. Janssens and L. Cuyvers. EDI – A strategic weapon in international trade. Long Range Planning. 24(2), 46–53 (1991).

Research Appendix 1: SISP survey items: resources, processes and output

Resources

1 The size of the planning team is very large.

2 It is difficult to find a team leader who meets the criteria specified by the methodology.

3 It is difficult to find team members who meet the criteria specified by the methodology.

4 The success of the methodology is greatly dependent on the team leader.

5 Many support personnel are required for data gathering and analysis during the study.

6 The planning exercise takes very long.

7 The planning exercise is very expensive.

8 The documentation does not adequately describe the steps that should be followed for implementing the methodology.

9 The methodology lacks sufficient computer support.

10 Adequate external consultant support is not available for implementing the methodology.

11 The methodology is not based on any theoretical framework.

12 The planning horizon considered by the methodology is inappropriate.

13 It is difficult to convince top management to approve the methodology.

14 The methodology makes inappropriate assumptions about organization structure.

15 The methodology makes inappropriate assumptions about organization size.

Process

The Methodology

1 fails to take into account organizational goals and strategies;

2 fails to assess the current information systems applications portfolio;

3 fails to analyse the current strengths and weaknesses of the IS department;

4 fails to take into account legal and environmental issues;

5 fails to assess the external technological environment;

6 fails to assess the organization's competitive environment;

7 fails to take into account issues related to plan implementation;

8 fails to take into account changes in the organization during SISP;

9 does not sufficiently involve users;

10 managers find it difficult to answer questions specified by the methodology;

11 requires too much top management involvement;

12 requires too much user involvement;

13 the planning procedure is rigid; and

14 does not sufficiently involve top management.

SISP Output:

1 fails to provide a statement of organizational objectives for the IS department;

2 fails to designate specific new steering committees;

3 fails to identify specific new products;

4 fails to determine a uniform basis for priorities projects;

5 fails to determine an overall data architecture for the organization;

6 fails to provide priorities for developing specific databases;

7 fails to sufficiently address the need for Data Administration in the organization;

8 fails to include an overall organizational hardware plan;

9 fails to include an overall organizational data communications plan;

10 fails to outline changes in the reporting relationships in the IS department;

11 fails to include an overall personnel and training plan for the IS department;

12 fails to include an overall financial plan for the IS department;

13 fails to sufficiently address the role of a permanent IS planning group;

14 plans are not flexible enough to take into account unanticipated changes in the organization and its environment;

15 is not in accordance with the expectations of top management;

16 implementing the projects and the data architecture identified in the SISP output requires substantial further analysis;

17 it is difficult to secure top management commitment for implementing the plan;

18 the experiences from implementing the methodology are not sufficiently transferable across divisions;

19 the final output document is not very useful; and

20 the SISP output does not capture all the information that was developed during the study.

Research Appendix 2: Extent of SISP problems

Abbreviated problem statement

Reproduced from Lederer, A. L. and Sethi, V. (1992) Meeting the challenges of information systems planning. Long Range Planning, 25(2), 60–80. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier Science. Copyright 1992 by Pergamon Press Ltd.

Questions for discussion

1 How might the appropriate planning process vary according to the context of IT and to the stage of growth (c.f. Chapter 2)?

2 Do you agree that the ‘quality of the planning process significantly influences the contribution which IS can make to an organization's performance’?

3 The authors state that ‘an organization's commitment to construct an organization-wide information architecture vastly complicates SISP. Thus, organizations have often failed to build such an architecture’. What are other factors, aside from commitment, that affect whether an organization has constructed an organization-wide information architecture?

4 Of the two major goals of SISP – impact (the search for high-impact applications and the creation of competitive advantage) and alignment (the identification of a portfolio of computer-based applications to assist an organization in executing business plans) – which do you recommend? Should the SISP also vary according to the stage of growth? Is it possible consciously to plan for strategic IS (i.e. the ‘impact’ goal)?

5 The authors state that ‘advocates of SISP should prepare convincing arguments to authorize the funding of the study’. What are some convincing arguments for why SISP should be carried out?

6 What would be the role of a permanent planning group? How might such a group overcome some of the major problems of SISP raised by the authors?