20 Information Technology and

Organizational Performance

Beyond the IT productivity

paradox

Despite the massive investments in Information Technology in the developed economies, the IT impact on productivity and business performance continues to be questioned. This chapter critically reviews this IT productivity paradox debate and finds that an important part, but by no means all, of the uncertainty about the IT payoff relates to weaknesses in measurement and evaluation practice. Based on extensive research by the authors and others, an integrated systems lifecycle approach is put forward as a long term way of improving evaluation practice in work organizations. The approach shows how to link business and IT/IS strategies with prioritizing investments in IT, and by setting up a set of interlinking measures, how IT costs and benefits may be evaluated and managed across the systems lifecycle, including consideration of potential uses of the external IT services market. An emphasis on a cultural change in evaluation from ‘control through numbers’ to a focus on quality improvement offers one of the better routes out of the productivity paradox. Improved evaluation practice serves to demystify the paradox, but also links with and helps to stimulate improved planning for management and use of IT, thus also reducing the paradox in practical terms – through the creation of greater business value.

Introduction

The history of numerous failed and disappointing Information Technology (IT) investments in work organizations has been richly documented. (Here IT refers to the convergence of computers, telecommunications and electronics, and the resulting technologies and techniques.) The 1993 abandonment of a five year project like Taurus in the UK London financial markets, in this case at a cost of £80 million to the Stock Exchange, and possibly £400 million to City institutions, provides only high profile endorsement of underlying disquiet on the issue. Earlier survey and case research by the present authors established IT investment as a high risk, hidden cost business, with a variety of factors, including size and complexity of the project, the ‘newness’ of the technology, the degree of ‘structuredness’ in the project, and major human, political and cultural factors compounding the risks (Willcocks and Griffiths, 1994; Willcocks and Lester, 1996). Alongside, indeed we would argue contributing to the performance issues surrounding IT, is accumulated evidence of problems in evaluation together with a history of general indifferent organizational practice in the area (Farbey et al., 1992; Strassman, 1990). In this chapter we focus firstly on the relationship between IT performance and its evaluation as it is expressed in the debate around what has been called the ‘IT productivity paradox’. A key finding is that assessment issues are not straightforward, and that some, though by no means all, of the confusion over IT performance can be removed if limitations in evaluation practice and measurement become better understood. From this base we then provide an overall conceptualization, with some detail, about how evaluation practice itself can be advanced, thus allowing some loosening of the Gordian knot represented by the IT productivity paradox.

‘What gets measured gets managed’ – the way forward?

The evaluation and management of IT investments is shot through with difficulties. Increasingly, as IT expenditure has risen and as the use of IT has penetrated to the core of organizations, the search has been directed towards not just improving evaluation techniques and processes, and searching for new ones, but also towards the management and ‘flushing out’ of benefits. But these evaluation and management efforts regularly run into difficulties of three generic types. First, many organizations find themselves in a Catch 22 situation. For competitive reasons they cannot afford not to invest in IT, but economically they cannot find sufficient justification, and evaluation practice cannot provide enough underpinning, for making the investment. Second, for many of the more advanced and intensive users of IT, as the IT infrastructure becomes an inextricable part of the organization's processes and structures, it becomes increasingly difficult to separate out the impact of IT from that of other assets and activities. Third, despite the high levels of expenditure, there is widespread lack of understanding of IT and Information Systems (IS – organizational applications, increasingly IT-based, that deliver on the information needs of the organization's stakeholders) as major capital assets. While senior managers regularly give detailed attention to the annual expenditure on IT/IS, there is little awareness of the size of the capital asset that has been bought over the years (Keen, 1991; Willcocks, 1994). Failure to appreciate the size of this investment leads to IT/IS being under-managed, a lack of serious attention being given to IS evaluation and control, and also a lack of concern for discovering ways of utilizing this IS asset base to its full potential.

Solutions to these difficulties have most often been sought through variants on the mantra: ‘what gets measured gets managed’. As a dominant guiding principle more – and more accurate – measurement has been advanced as the panacea to evaluation difficulties. In a large body of literature, while some consideration is given to the difficulties inherent in quantifying IT impacts, a range of other difficulties are downplayed, or even ignored. These include, for example:

• the fact that measurement systems are prone to decay

• the goal displacement effects of measurement

• the downside that only that which is measured gets managed

• the behavioural implications of measurement and related reward systems, and

• the politics inherent in any organizational evaluation activity.

In practice, counter evidence against a narrow focus on quantification for IT/IS evaluation has been gathering. Thus some recent studies point to how measurement can be improved, but also to the limitations of measurement, and areas where sets of measures may be needed because of the lack of a single reliable measure (Farbey et al., 1995). They also point to the key role of stakeholder judgement throughout any IT/IS evaluation process. Furthermore some published research studies point to the political-rational as opposed to the straightforwardly rational aspects of IT measurement in organizations. For example Lacity and Hirschheim (1996) provide an important insight into how measurement, in this case benchmarking IT performance against external comparators, can be used in political ways to influence senior management judgement. Currie (1989) detailed the political uses of measurement in a paper entitled ‘The art of justifying new technology to top management’. Additionally, there are signs that the problems with over-focusing on measurement are being recognized, albeit slowly, with moves toward emphasizing the demonstration of the value of IS/IT, not merely its measurement. Elsewhere we have argued for the need to move measurement itself from a focus on the price of IT to a concern for its value; and for a concomitant shift in emphasis in the measurement regime from control to quality improvement (Willcocks and Lester, 1996).

These difficulties and limitations in evaluation practice have become bound up in a widespread debate about what has been called the IT productivity paradox – the notion that despite large investments in IT over many years, it has been difficult to discover where the IT payoffs have occurred, if indeed there have been many. In this chapter we will address critically the overall sense that many have that despite huge investments in IS/IT so far, these have been producing disappointing returns. We will find that while much of the sense of disappointment may be justified, at the same time it is fed by limitations in evaluation techniques and processes, and by misunderstandings of the contribution IT can and does make to organizations, as much as by actual experience of poorly performing information systems. The focus then moves to how organizations may seek to improve their IT/IS evaluation procedures and processes. Taking into account the many limitations in evaluation practice continuing to be identified by a range of the more recent research studies, a high level framework is advanced for how evaluation can and needs to be applied across the systems lifecycle. The chapter also suggests that processes of evaluation, and the involvement of stakeholders, may be as, if not more, important than refining techniques and producing measurement of a greater, but possibly no less spurious, accuracy.

The IT ‘productivity paradox’ revisited

Alongside the seemingly inexorable rise of IS/IT investment in the last 15 years, there has been considerable uncertainty and concern about the productivity impact of IT being experienced in work organizations. This has been reinforced by several high profile studies at the levels of both the national economy and industrial sector suggesting in fact that if there has been an IS/IT payoff it has been minimal, and hardly justifies the vast financial outlays incurred. Two early influential studies embodying this theme were by Roach (1986) and Loveman (1988). A key, overarching point needs to be made immediately. It is clear from reviews of the many research studies conducted at national, sectoral and organization specific levels that the failure to identify IS/IT benefits and productivity says as much about the deficiencies in assessment methods and measurement, and the rigour with which they are applied, as about mismanagement of the development and use of information-based technologies. It is useful to chase this hare of ‘the IT productivity paradox’ further, because the issue goes to the heart of the subject of this chapter.

Interestingly, the IT productivity paradox is rarely related in the literature to manufacturing sectors for which, in fact, there are a number of studies from the early 1980s showing rising IT expenditure correlating with sectoral and firm-specific productivity rises (see Brynjolfsson and Hitt, 1993; Loveman, 1988). The high profile studies raising concern also tend to base their work mainly on statistics gathered in the US context. Their major focus, in fact, tends to be limited to the service sector in the US. Recently a number of studies question the data on which such studies were based, suggesting that the data is sufficiently flawed to make simple conclusions misleading (Brynjolfsson, 1993). It has been pointed out, for example that in the cases of Loveman (1988) and Roach (1986) neither personally collected the data that they analysed, thus their observations describe numbers rather than actual business experiences (Nievelt, 1992).

Still others argue that the productivity payoff may have been delayed but, by the mid-1990s, recession and global competition have forced companies to finally use the technologies they put in place over the last decade, with corresponding productivity leaps. Moreover, productivity figures always failed to measure the cost avoidance and savings on opportunity costs that IS/IT can help to achieve (Gillin, 1994).

Others also argue that the real payoffs occur when IS/IT development and use is linked with the business reengineering (BPR) efforts coming onstream in the 1990s (Hammer and Champy, 1993). However, recent UK evidence develops this debate by finding that few organizations were actually getting ‘breakthrough’ results through IT-enabled BPR. Organizations were ‘aiming low and hitting low’ and generally not going for the radical, high-risk reengineering approaches advocated by many commentators. Moreover there was no strong correlation between size of IT expenditure on reengineering projects, and resulting productivity impacts. In business process reengineering, as elsewhere (see below), it is the management of IT, and what it is used for, rather than the size of IT spend that counts (Willcocks, 1996b).

Bakos and Jager (1995) provide interesting further insight, as they argue that computers are not boosting productivity, but the fault lies not with the technology but with its management and how computer use is overseen. They question the reliability of the productivity studies, and, supporting the positive IT productivity findings in the study by Brynjolfsson and Hitt (1993), posit a new productivity paradox: ‘how can computers be so productive?’

In the face of such disputation Brynjolfsson (1993) makes salutary reading. He suggests four explanations for the seeming IT productivity paradox. The first is measurement errors. In practice the measurement problems appear particularly acute in the service sector and with white collar worker productivity – the main areas investigated by those pointing to a minimal productivity impact from IT use in the 1980s and early 1990s. Brynjolfsson concludes from a close examination of the data behind the studies of IT performance at national and sectoral levels that mismeasurement is at the core of the IT productivity paradox. A second explanation is timing lags due to learning and adjustment. Benefits from IT can take several years to show through in significant financial terms, a point also made by Strassman (1990) in arguing for newer ways of evaluating IS/IT performance at the organizational level. While Brynjolfsson largely discounts this explanation, there is evidence to suggest he is somewhat over-optimistic about the ability of managers to account rationally for such lags and include them in their IS/IT evaluation system (Willcocks, 1996a).

A third possible explanation is that of redistribution. IT may be beneficial to individual firms but unproductive from the standpoint of the industry, or the economy, as a whole. IT rearranges the share of the pie, with the bigger share going to those heavily investing in IT, without making the pie bigger. Brynjolfsson suggests, however, that the redistribution hypothesis would not explain any shortfall in IT productivity at the firm level. To add to his analysis one can note that in several sectors, for example banking and financial services, firms seemingly compete by larger spending on IT-based systems that are, in practice, increasingly becoming minimum entry requirements for the sector, and commodities rather than differentiators of competitive performance. As a result in some sectors, for example the oil industry, organizations are increasingly seeking to reduce such IS/IT costs by accepting that some systems are industry standard and can be developed together.

A fourth explanation is that IS/IT is not really productive at the firm level. Brynjolfsson (1993) posits that despite the neoclassical view of the firm as a profit maximizer, it may well be that decision-makers are, for whatever reason, often not acting in the interests of the firm: ‘instead they are increasing their slack, building inefficient systems, or simply using outdated criteria for decision-making’ (p.75). The implication of Brynjolfsson's argument is that political interests and/or poor evaluation practice may contribute to failure to make real, observable gains from IS/IT investments. However, Brynjolfsson appears to discount these possibilities citing a lack of evidence either way, though here he seems to be restricting himself to the economics literature. Against his argument however, there are in fact frequent study findings showing patchy strategizing and implementation practice where IS is concerned (for an overview see Willcocks et al., 1996). Furthermore, recent evidence in the IT evaluation literature suggests more evidence showing poor evaluation practice than Brynjolfsson has been willing to credit (see Ballantine et al., 1996; Willcocks and Lester, 1996).

It is on this point that the real debate on the apparent ‘IT productivity paradox’ needs to hinge. Studies at the aggregate levels of the economy or industrial sector conceal important questions and data about variations in business experiences at the organizational and intra-organizational levels. In practice, organizations seem to vary greatly in their ability to harness IS/IT for organizational purpose. In an early study Cron and Sobol (1983) pointed to what has since been called the ‘amplifier’ effect of IT. Its use reinforces existing management approaches dividing firms into very high or very low performers. This analysis has been supported by later work by Strassman (1990), who also found no correlation between size of IT expenditure and firms’ return on investment. Subsequently, a 1994 analysis of the information productivity of 782 US companies found that the top 10 spent a smaller percentage (1.3 per cent compared to 3 per cent for the bottom 100) of their revenue on IS, increased their IS budget more slowly (4.3 per cent in 1993–4 – the comparator was the bottom 110 averaging 10.2 per cent), thus leaving a greater amount of finance available for non-IS spending (Gillin, 1994).

Not only did the the top performers seem to spend less proportionately on their IT; they also tended to keep certain new investments as high as business conditions permitted while holding back on infrastructure growth. Thus, on average, hardware investments were only 15 per cent of the IS budget while new development took more than 50 per cent, with 41 per cent of systems development spending incurred on client/server investment (Sullivan-Trainor, 1994). Clearly the implication of this analysis is that top performers spend relatively less money on IS/IT, but focus their spending on areas where the expenditure will make more difference in terms of business value. An important aspect of their ability to do this must lie with their evaluation techniques and processes. Nievelt (1992) adds to this picture. Analysing database information on over 300 organizations he found empirically that IT as a coordinating, communicating and leveraging technology was capable of enhancing customer satisfaction, flattening organizational pyramids and supporting knowledge workers in the management arena. At the same time many organizations did not direct their IT expenditure into appropriate areas at the right time, partly because of inability to carry out evaluation of where they were with their IT expenditure and IT performance relative to business needs in a particular competitive and market context.

Following on from this, it is clear that significant aspects of the IT productivity paradox, as perceived and experienced at organizational level, can be addressed through developments in evaluation and management practice. In particular the distorting effects of poor evaluation methods and processes need close examination and profiling; alternative methods, and an assessment of their appropriateness for specific purposes and conditions need to be advanced; and how these methods can be integrated together and into management practice needs to be addressed.

Investing in information systems

In the rest of this chapter we will focus not on assessing IT/IS performance at national or industry levels, but on the conduct of IT/IS evaluation within work organizations. As already suggested, IT/IS expenditure in such organizations is high and rising. The United States leads the way, with government statistics suggesting that, by 1994, computers and other information technology made up nearly half of all business spending on equipment – not including the billions spent on software and programmers each year. Globally, computer and telecommunications investments now amount to a half or more of most large firms’ annual capital expenditures. In an advanced industrialized economy like the United Kingdom, IS/IT expenditure by business and public sector organizations was estimated at £33.6 billion for 1995, and expected to rise at 8.2 per cent, 7 per cent and 6.5 per cent in subsequent years, representing an average of over 2 per cent of turnover, or in local and central government an average IT spend of £3546 per employee. Organizational IS/IT expenditure in developing economies is noticeably lower, nevertheless those economies may well leapfrog several stages of technology, with China, Russia, India and Brazil, for example, set to invest in telecommunications an estimated 53.3, 23.3, 13.7, and 10.2 billion dollars (US) respectively in the 1993–2000 period (Engardio, 1994).

There were many indications by 1995, of managerial concern to slow the growth in organizational IS/IT expenditure. Estimates of future expenditure based on respondent surveys in several countries tended to indicate this pattern (see for example Price Waterhouse, 1995). The emphasis seemed to fall on running the organization leaner, wringing more productivity out of IS/IT use, attempting to reap the benefits from changes in price/performance ratios, while at the same time recognizing the seemingly inexorable rise in information and IT intensity implied by the need to remain operational and competitive. In particular, there is wide recognition of the additional challenge of bringing new technologies into productive use. The main areas being targetted for new corporate investment seemed to be client/server computing, document image processing and groupware, together with ‘here-and-now’ technologies such as advanced telecom services available from ‘intelligent networks’, mobile voice and digital cellular systems (Taylor, 1995). It is in the context of these many concerns and technical developments that evaluation techniques and processes need to be positioned.

Evaluation: a systems lifecycle approach

At the heart of one way forward for organizations is the notion of an IT/IS evaluation and management cycle. A simplified diagrammatic representation of this is provided in Figure 20.1. Earlier research found that few organizations actually operated evaluation and management practice in an integrated manner across systems lifecycles (Willcocks, 1996a). The evaluation cycle attempts to bring together a rich and diverse set of ideas, methods, and practices that are to be found in the evaluation literature to date, and point them in the direction of an integrated approach across systems lifetime. Such an approach would consist of several interrelated activities:

1 Identifying net benefits through strategic alignment and prioritization.

2 Identifying types of generic benefit, and matching these to assessment techniques.

3 Developing a family of measures based on financial, service, delivery, learning and technical criteria.

Figure 20.1 IT/IS evaluation and management cycle

4 Linking these measures to particular measures needed for development, implementation and post-implementation phases.

5 Ensuring each set of measures run from the strategic to the operational level.

6 Establishing responsibility for tracking these measures, and regularly reviewing results.

7 Regularly reviewing the existing portfolio, and relating this to business direction and performance objectives.

A key element in making the evaluation cycle dynamic and effective is the involvement of motivated, salient stakeholders in processes that operationalize – breathe life into, adapt over time, and act upon – the evaluation criteria and techniques. Let us look in more detail at the rationale for, and shape of such an approach. In an earlier review of front-end evaluation Willcocks (1994) pointed out how lack of alignment between business, information systems and human resource/organizational strategies inevitably compromised the value of all subsequent IS/IT evaluation effort, to the point of rendering it of marginal utility and, in some cases, even counter-productive. In this respect he reflected the concerns of many authors on the subject. A range of already available techniques were pointed to for establishing strategic alignment, and linking strategy with assessing the feasibility of any IS/IT investment, and these will not be repeated here (for a review see Willcocks, 1994). At the same time the importance of recognizing evaluation as a process imbued with inherent political characteristics and ramifications was emphasized, reflecting a common finding amongst empirical studies.

The notion of a systems portfolio implies that IT/IS investment can have a variety of objectives. The practical problem becomes one of prioritization – of resource allocation amongst the many objectives and projects that are put forward. Several classificatory schemes for achieving this appear in the extant literature. Thus Willcocks (1994) and others have suggested classificatory schemes that match business objectives with types of IS/IT project. Thus, on one schema, projects could be divided into six types – efficiency, effectiveness, must-do, architecture, competitive edge, and research and development. The type of project could then be matched to one of the more appropriate evaluation methods available, a critical factor being the degree of tangibility of the costs and benefits being assessed. Costs and benefits need to be sub-classified into ‘for example’ hard/soft, or tangible/intangible, or direct/indirect/inferred, and the more appropriate assessment techniques for each type adopted (see Willcocks, 1994 for a detailed discussion). Norris (1996) has provided a useful categorization of types of investments and main aids to evaluation, and a summary is shown in Table 20.1.

After alignment and prioritization assessment, the feasibility of each IS/IT investment then needs to be examined. All the research studies show that the main weakness here have been the over-reliance on and/or misuse of traditional, finance-based cost-benefit analysis. The contingency approach outlined above and in Table 20.1 helps to deal with this, but such approaches need to be allied with active involvement of a wider group of stakeholders than those at the moment being identified in the research studies. A fundamental factor to remember at this stage is the importance of a business case being made for an IT/IS investment, rather than any strict following of specific sets of measures. As a matter of experience where detailed measurement has to be carried out to differentiate between specific proposals, it may well be that there is little advantage to be had not just between each, but from any. Measurement contributes to the business case for or against a specific investment but cannot substitute for a more fundamental managerial assessment as to whether the investment is strategic and critical for the business, or will merely result in yet another useful IT application.

Table 20.1 Types of investment and aids to evaluating IT

Type of investment |

Business benefit |

Main formal aids to investment evaluation |

Importance of management judgement |

Main aspects of management judgement |

Mandatory investments as a result of: |

|

|

|

|

Regulatory requirements |

Satisfy minimum legal requirement |

Analysis of costs |

Low |

Fitness of the system for the purpose |

Organizational requirements |

Facilitate business operations |

Analysis of costs |

Low |

Fitness of the system for the purpose. Best option for variable organizational requirements |

Competitive pressure |

Keep up with the competition |

Analysis of costs to achieve parity with the competition. Marginal cost to differentiate from the competition, providing the opportunity for competitive advantage |

Crucial |

Competitive need to introduce the system at all. Effect of introducing the system into the marketplace. Commercial risk. Ability to sustain competitive advantage |

Investments to improve performance |

Reduce costs |

Cost/benefit analysis |

Medium |

Validity of the assumptions behind the case |

|

Increase revenues |

Cost/benefit analyses. Assessment of hard-to-quantify benefits. Pilots for high risk investment |

High |

Validity of the assumptions behind the case. Real value of hard-to-quantify benefits. Risk involved |

Investments to achieve competitive advantage |

Achieve a competitive leap |

Analysis of costs and risks |

Crucial |

Competitive aim of the system. Impact on the market and the organization. Risk involved |

Infrastructure investment |

Enable the benefits of other applications to be realized |

Setting of performance standards. Analysis of costs |

Crucial |

Corporate need and benefit, both short and long term |

Investment in research |

Be prepared for the future |

Setting objectives within cost limits |

High |

Long-term corporate benefit. Amount of money to be allocated |

Source: Norris (1996).

Following this, Figure 20.1 suggests that evaluation needs to be conducted in a linked manner across systems development and into systems implementation and operational use. The evaluation cycle posits the development of a series of interlinked measures that reflect various aspects of IS/IT performance, and that are applied across systems lifetime. These are tied to processes and people responsible for monitoring performance, improving the evaluation system and also helping to ‘flush out’ and manage the benefits from the investment. Figure 20.1 suggests, in line with prevailing academic and practitioner thinking by the mid-1990s, that evaluation cannot be based solely or even mainly on technical efficiency criteria. For other criteria there may be debate on how they are to be measured, and this will depend on the specific organizational circumstances.

However there is no shortage of suggestions here. Taking one of the more difficult, Keen (1991) discusses measuring the cost avoidance impacts of IT/IS. For him these are best tracked in terms of business volumes increases compared to number of employees. The assumption here is that IT/IS can increase business volumes without increases in personnel. At the strategy level he also suggests that the most meaningful way of tracking IT/IS performance over time is in terms of business performance per employee, for example revenue per employee, profit per employee, or at a lower level, as one example – transactions per employee.

Kaplan and Norton (1992) were highly useful for popularizing the need for a number of perspectives on evaluation of business performance. Willcocks (1994) showed how the Kaplan and Norton balanced scorecard approach could be adapted fairly easily for the case of assessing IT/IS investments. To add to that picture, most recent research suggests the need for six sets of measures. These would cover the corporate financial perspective (e.g. profit per employee); the systems project (e.g. time, quality, cost); business process (e.g. purchase invoices per employee); the customer/user perspective (e.g. on-time delivery rate); an innovation/learning perspective (e.g. rate of cost reduction for IT services); and a technical perspective (e.g. development efficiency, capacity utilization). Each set of measures would run from strategic to operational levels, each measure being broken down into increasing detail as it is applied to actual organizational performance. For each set of measures the business objectives for IT/IS would be set. Each objective would then be broken down into more detailed measurable components, with a financial value assigned where practicable. An illustration of such a hierarchy, based on work by Norris (1996), is shown in Figure 20.2.

Responsibility for tracking these measures, together with regular reviews that relate performance to objectives and targets are highly important elements in delivering benefits from the various IS investments. It should be noted that such measures are seen as helping to inform stakeholder judgements, and not as a substitute for such judgements in the evaluation process.

Figure 20.2 Measurable components of business objectives for IT/IS. (Adapted from Norris, 1996)

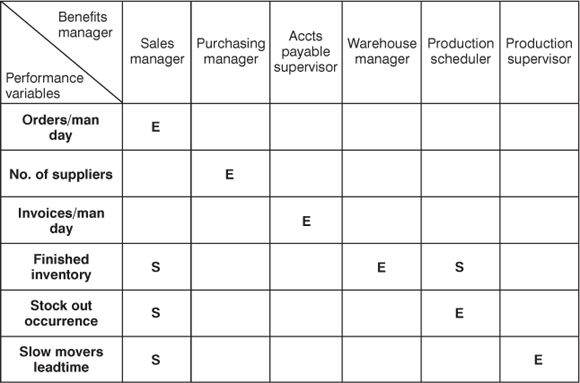

Some detail can be provided on how to put metrics in place, monitor them and ensure benefits are delivered. The following schema is derived from work by Peters (1996) and Willcocks and Lester (1996). Projects were found to be managed well, and often over-performed their original appraisal, where a steering group was set up early in a project, was managed by a senior user manager, and represented the key operating functions impacted by the IT/IS. The steering group followed the project to a late stage of implementation with members frequently taking responsibility for delivering benefits from parts of the IT/IS implementation. Project benefits need to be incorporated into business area budgets, and individuals identified for monitoring performance and delivering benefits. Variables impacted by the IT/IS investment were identified and decomposed into a hierarchy based on key operating parameters necessary to deliver the benefit. A framework needs to be established for clearly identifying responsibilities for benefits (Figure 20.3). Peters (1996) suggests that the information on responsibilities should be published, and known to relevant parties, and that measures should be developed to monitor benefits at the lowest level of unit performance. We would add that links also need to be made between the individual's performance in the assessment role and his/her own appraisal and reward.

Figure 20.3 Assigning responsibility for delivering benefits of IT/IS implementation (E = executive responsibility; S = support). (Based on peters, 1996)

The steering group should regularly review the benefits gained, for example every three months, and also report less frequently to the IT/IS strategy steering group, with flushing out of IT/IS benefits seen as an essential extension of the strategic review process, not least in its capacity to facilitate more effective IT/IS implementation. What is clear in this scheme is that measurement that is business – not solely technical efficiency – focused plays an important part in evaluation but only in the context of appropriate processes in place operated by a wide range of motivated stakeholders.

Completing the cycle: existing and future investments

One all too often routinized phase of review is that of post-implementation (see Figure 20.1). Our own research suggests that this is one of the most neglected, yet one of the more important areas as far as IS evaluation is concerned. An advantage of the above schema, in practice, is that post-implementation evaluation arises naturally out of implementation assessment on an ongoing basis, with an already existing set of evaluators in place. This avoids the ritualistic, separated review that usually takes place in the name of post-implementation review (Kumar, 1990 – detailed discussion on how to perform an effective post-implementation review cannot be provided here, but see Norris, 1996).

There remains the matter of assessing the ongoing systems portfolio on a regular basis. Notoriously, when it comes to evaluating the existing IS investment, organizations are not good at drop decisions. There may be several related ramifications. The IT inheritance of ‘legacy systems’ can deter investment in new systems – it can, for example, be all too difficult to take on new work when IT/IS staff are awash in a rising tide of maintenance arising from the existing investment. Existing IT/IS-related activity can also devour the majority of the financial resources available for IS investment. All too often such failures derive from not having in place, or not operationalizing, a robust assessment approach that enables timely decisions on systems and service divestment, outsourcing, replacement, enhancement, and/or maintenance. Such decisions need to be based on at least two criteria – the technical quality of the system/service, and its business contribution – as well as being related back to the overall strategic direction and objectives of the organization (see Figure 20.1).

A further element in assessment of the ongoing systems portfolio is the relevance of external comparators. External benchmarking firms – for example RDC and Compass – have already been operating for several years, and offer a range of services that can be drawn upon, but mainly for technical aspects of IT performance. The assessment of data centre performance is now well established amongst the better benchmarking firms. Depending on the benchmarking database available, a data centre can be assessed against other firms in the same sector, or of the same generic size in computing terms, and also against outsourcing vendor performance. Benchmarking firms are continually attempting to extend their services, and can provide a useful assessment, if mainly only on the technical efficiency of existing systems. There is, however, a growing demand for extending external benchmarking services more widely to include business, and other, performance measures – many of which could include elements of IT contribution (see above). Indeed Strassman (1990) and Nievelt (1992) are but two of the more well known of a growing number of providers of diagnostic benchmarking methodologies that help to locate and reposition IT contribution relative to actual and required business performance. It is worth remarking that external IT benchmarking – like all measures – can serve a range of purposes within an organization. Lacity and Hirschheim (1996) detail from their research how benchmarking services were used to demonstrate to senior executives the usefulness of the IT department. In some cases external benchmarking subsequently led to the rejection of outsourcing proposals from external vendors.

This leads into the final point. An increasingly important part of assessing the existing and any future IT/IS investment is the degree to which the external IT services market can provide better business technical and economic options for an organization. In practice, recent survey and case research by the authors and others found few organizations taking a strategic approach to IT/IS sourcing decisions, though many derived economic and other benefits from incremental, selective, low risk, as opposed to high risk ‘total’ approaches to outsourcing (Lacity and Hirscheim, 1995). The Yankee Group estimated the 1994 global IT outsourcing market as exceeding $US49.5 billion with an annual 15 per cent growth rate. As at 1995 the US market was the biggest, estimated to exceed $18.2 billion. The UK remained the largest European market in 1994 exceeding £1 billion, with an annual growth rate exceeding 10 per cent on average across sectors. Over 50 per cent of UK organizations outsourced some aspect of IT in 1994, and outsourcing represented on average 24 per cent of their IT budgets (Lacity and Hirscheim, 1995; Willcocks and Fitzgerald, 1994).

Given these figures, it is clear that evaluation of IT/IS sourcing options, together with assessment of on-going vendor performance in any outsourced part of the IT/IS service, needs to be integrally imbedded into the systems lifecycle approach detailed above. Not least because an external vendor bid, if carefully analysed against one's own detailed in-house assessment of IT performance, can be a highly informative form of benchmarking. Figure 20.1 gives an indication of where sourcing assessments fit within the lifecycle approach, but recent research can give more detail on the criteria that govern successful and less successful sourcing decisions.

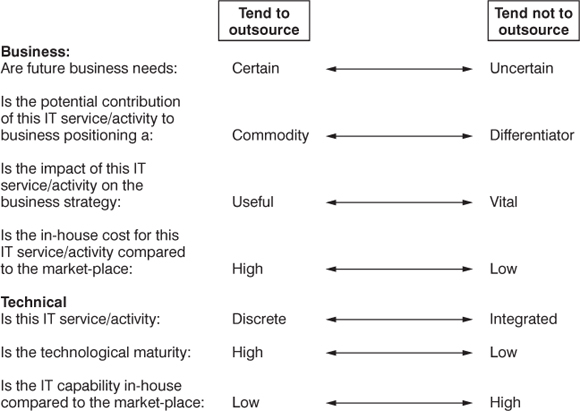

In case and survey research Willcocks and Fitzgerald (1994) found six key factors (see Figure 20.4). Three are essentially business related. Firstly, IT can contribute to differentiating a business from its competitors, thus providing competitive advantage. Alternatively an IT activity/service may be a commodity, not distinguishing the business from a competitor in business offering and performance terms.

Second, the IT may be strategic in underpinning the firm's achievement of goals, and critical to its present and future strategic direction, or merely useful. Third, the degree of uncertainty about future business environment and needs impacts upon longer term IT needs. High uncertainty suggests inhouse sourcing as a better option. As Figure 20.4 suggests the preferred option where possible, is to outsource useful commodities in conditions of certainty about business requirements across the length of the contract. Three technical considerations are also important. It is unwise for an organization to outsource in a situation of low technology maturity. This exists where a technology is new and unstable, and/or where there is an existing technology but being applied in a radically new way, and/or where there is little relevant in-house experience with the technology. Next, the level of IT integration must influence the sourcing decision. Generally we found it preferable not to outsource systems/activities that are highly integrated with other parts of the technical platform, and/or that interface in complex ways with many business users who will be impacted significantly by the service. Finally, where inhouse capability is equivalent to or better than that available on the external market, there would seem to be a less pressing need to outsource the IT service/activity.

Figure 20.4 Criteria for making sourcing decisions

Making sourcing decisions, in practice, involves making trade-offs among the preferences suggested by these factors. In addition, we note six reality checks that need to be borne in mind before deciding on a specific sourcing option:

• Does the decision make economic sense?

• How does the decision fit with the rate of technological change?

• Are there issues around ownership when transferring people and assets?

• Is a suitable vendor available?

• Does the organization have the management capability to deliver on the decision?

Will significant human resource issues arise – during the change process, and subsequently for in-house and vendor staff ?

Outsourcing is defined as the commissioning of third party management of IT assets/activities to required result. This does not exclude another way of using the market, of course, namely ‘insourcing’ – where external resources are utilized in an organization under in-house management. There is also an option to have long or short term contracts with suppliers. In situations of high business uncertainty and/or rapid technological change shorter term contract are to be preferred. We also found, together with Lacity and Hirschheim (1995), that selective rather than total outsourcing (80 per cent or more of IT budget spent on outsourcing), tended to be the lower risk, and more successful option to take.

In more detailed work, we found outsourcing requiring a considerable cultural change on evaluation. Before outsourcing any IT, the more successful organizations measured everything in a three to six month baseline period. This enabled them to compare more accurately the in-house performance against a vendor bid. It also prefigured the setting up of a tighter evaluation regime with more detailed and accurate performance measures and service level agreements. In cases where an in-house vendor bid won, we found that the threat of the vendor bid actually galvanized the in-house staff into identifying new ways of improving on IS/IT performance, and into maintaining the improvement through putting in place, and acting on the output from, enhanced evaluation criteria and measures. This brings us full circle. Even where an organization does not outsource IT, our case evidence is that increasingly it is good practice to assess in-house performance against what a potential vendor bid might be, even if, as is increasingly the case, this means paying a vendor for the assessment. By the same token, benchmarking IT/IS performance against external comparators can also be highly useful, in providing insight not only into in-house IT/IS performance, but also into the efficacy of internal evaluation criteria, processes and the availability or otherwise of detailed, appropriate assessment information.

Conclusion

There are several ways out of the IT productivity paradox. Several of the more critical relate to improved ways of planning for, managing and using IT/IS. However, part of the IT productivity paradox has been configured out of difficulties and limitations in measuring and accounting for IT/IS performance. Bringing the so-called paradox into the more manageable and assessable organizational realm, it is clear that there is still, as at 1996, much indifferent IT/IS evaluation practice to be found in work organizations. In detailing an integrated lifecycle approach to IT/IS evaluation we have utilized the research findings of ourselves and others to suggest one way forward. The ‘cradle to grave’ framework is holistic and dynamic and relies on a judicious mixture of ‘the business case’, appropriate criteria and metrics, managerial and stakeholder judgement and processes, together with motivated evaluators. Above all it signals a move from ‘control through numbers’ assessment culture to one focused on quality improvement. This would seem to offer one of the better routes out of the productivity paradox, not least in its ability to link up evaluation to improving approaches to planning for, managing and using IT. As such it may also serve to begin to demystify the ‘IT productivity paradox’, and reveal that it is as much about human as technology issues – and better cast anyway as the IT-management productivity paradox, perhaps?

References

Bakos, Y. and Jager, P. de (1995) Are computers boosting productivity? Computerworld, 27 March, 128–130.

Ballantine, J., Galliers, R. D. and Stray, S. J. (1996) Information systems/technology evaluation practices: evidence from UK organizations. Journal of Information Technology, 11(2), 129–141.

Brynjolfsson, E. (1993) The productivity paradox of information technology. Communications of the ACM, 36(12), 67–77.

Brynjolfsson, E. and Hitt, L. (1993) Is information systems spending productive? Proceedings of the International Conference in Information Systems, Orlando, December.

Cron, W. and Sobol, M. (1983) The relationship between computerization and performance: a strategy for maximizing the economic benefits of computerization. Journal of Information Management, 6, 171–181.

Currie, W. (1989) The art of justifying new technology to top management. Omega, 17(5), 409–418.

Engardio, P. (1994) Third World leapfrog. Business Week, 13 June, 46–47.

Farbey, B., Land, F. and Targett, D. (1992) Evaluating investments in IT. Journal of Information Technology, 7(2), 100–112.

Farbey, B., Targett, D. and Land, F. (eds) (1995) Hard Money, Soft Outcomes, Alfred Waller/Unicom, Henley, UK.

Gillin, P. (ed.) (1994) The productivity payoff: the 100 most effective users of information technology. Computerworld, 19 September, 4–55.

Hammer, M. and Champy, J. (1993) Reengineering The Corporation: A Manifesto For Business Revolution, Nicholas Brealey, London.

Kaplan, R. and Norton, D. (1992) The balanced scorecard: measures that drive performance. Harvard Business Review, January–February, 71–79.

Keen, P. (1991) Shaping the Future: Business Design Through Information Technology, Harvard Business Press, Boston.

Kumar, K. (1990). Post-implementation evaluation of computer-based information systems: current practices. Communications of the ACM, 33(2), 203–212.

Lacity, M. and Hirschheim, R. (1995) Beyond the Information Systems Outsourcing Bandwagon, Wiley, Chichester.

Lacity, M. and Hirschheim, R. (1996) The role of benchmarking in demonstrating IS performance. In Investing in Information Systems: Evaluation and Management (ed. L. Willcocks), Chapman and Hall, London.

Lacity, M. Willcocks, L. and Feeny, D. (1995) IT outsourcing: maximize flexibility and control. Harvard Business Review, May–June, 84–93.

Loveman, G. (1988) An assessment of the productivity impact of information technologies. MIT management in the nineties. Working Paper 88–054. Massachussetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge.

Nievelt, M. van (1992) Managing with information technology – a decade of wasted money? Compact, Summer, 15–24.

Norris, G. (1996) Post-investment appraisal. In Investing in Information Systems: Evaluation and Management (ed. L. Willcocks), Chapman and Hall, London.

Peters, G. (1996) From strategy to implementation: identifying and managing benefits of IT investments. In Investing in Information Systems: Evaluation and Management (ed. L. Willcocks), Chapman and Hall, London.

Price Waterhouse (1995) Information Technology Review 1994/5, Price Waterhouse, London.

Roach, S. (1986) Macrorealities of the Information Economy, National Academy of Sciences, New York.

Strassman, P. (1990) The Business Value of Computers, Information Economic Press, New Canaan, CT.

Sullivan-Trainor, M. (1994) Best of breed. In The Productivity Payoff: The 100 Most Effective Users of Information Technology (ed. P. Gillin), Computerworld, 19 September, 8–9.

Taylor, P. (1995) Business solutions on every side. Financial Times Review: Information Technology, 1 March, 1.

Willcocks, L. (ed.) (1994) Information Management: Evaluation of Information Systems Investments, Chapman and Hall, London.

Willcocks, L. (ed.) (1996a) Investing in Information Systems: Evaluation and Management, Chapman and Hall, London.

Willcocks, L. (1996b) Does IT-enabled BPR pay off? Recent findings on economics and impacts. In Investing In Information Systems: Evaluation and Management, Chapman and Hall, London.

Willcocks, L. and Fitzgerald, G. (1994) A business guide to IT outsourcing. Business Intelligence, London.

Willcocks, L. and Griffiths, C. (1994) Predicting risk of failure in large-scale information technology projects. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 47(2), 205–228.

Willcocks, L. and Lester, S. (1996) The evaluation and management of information systems investments: from feasibility to routine operations. In (1996). Investing In Information Systems: Evaluation and Management (ed. L. Willcocks), Chapman and Hall, London.

Willcocks, L., Currie, W. and Mason, D. (1996) Information Systems at Work: People Politics and Technology, McGraw-Hill, Maidenhead, UK.

Reproduced from Willcocks, L. and Lester, S. (1996) Beyond the IT productivity paradox. European Management Journal, 14(3), June, 279–290. Reprinted by permission of Elsevier Science.

Questions for discussion

1 What is the IT productivity paradox? Does it actually exist in your view, and if so, to what extent is it sectorally based? Do you believe it will remain a problem in, say, 5 years’ time?

2 Why is the evaluation and management of IT investment ‘shot through with difficulties’? And what's wrong with the maxim ‘what gets measured gets managed’?

3 Critically evaluate the IT/IS evaluation and management cycle introduced in this chapter. How might it be adapted so as to be integrated in an ongoing IS planning process?

4 Reflect on the question of the evolution and management of different types of IT investments mentioned in this chapter, and the ‘stages of growth’ concept introduced in Chapter 2. How might evaluation and management of IT evolve from one stage to another?

5 Managing benefits are highlighted as a critical success factor by the authors. Reflect on the differing roles an IT steering committee, individual executives and managers might take in dealing with stock-outs for example.

6 The authors introduce the issue of sourcing IT services. Why might outsourcing IT services require ‘a considerable cultural change on evaluation’? Reflect on issues introduced in Chapter 16 when considering this question.