15 The Information

Technology–Organizational

Design Relationship

Information technology and new

organizational forms

Throughout the 1980s there was a tremendous emphasis on business strategy. Many organizations developed sophisticated strategies with scant attention given to their ability and capability to deliver these strategies. Over the past few years a tremendous amount has been written about the organization of the 1990s, its characteristics and the key enabling role of information technology. While this presents us with a destination in general terms, little attention is given in how to get there. This chapter addresses this concern, beginning by reviewing six perspectives which best represent current thinking on new ways of organizing and outlines their characteristics. Having identified their key characteristics, three key issues which now dominate the management agenda are proposed. The vision: where do we want to be in terms of our organizational form? Gap analysis and planning: how do we get there? and Managing the migration: how do we manage this process of reaching our destination? Extending the traditional information systems/information technology strategic planning model, a framework is presented which addresses these concerns. This framework is structured around the triumvirate of vision, planning and delivery with considerable iteration between planning and delivery to ensure the required form is met.

Introduction

Academics, consultants and managers continually debate the most effective organizational form. (Organizational form includes structure, systems, management style, cultures, roles, responsibilities, skills, etc.) If there is agreement it is that there is no one best way to develop organizations to achieve the best mix of structure, systems, management style, culture, roles, responsibilities and skills. One lesson is clear and it is that organizations must adopt a form that is appropriate to their strategy and the competitive position within which they find themselves. Recently there has been a spate of papers challenging traditional ways of organizing and their underlying assumptions and proposing alternative approaches. Many of these approaches are dependent on opportunities provided by information technology (IT).

Clearly the situation within which organizations find themselves today is radically different than from earlier times. As we saw earlier, the 1990s have been characterized by globalization of markets, intensification of competition, acceleration of product life cycles, and growing complexity with suppliers, buyers, governments and other stakeholder organizations. Rapidly changing and more powerful technology provides new opportunities. To be competitive in these conditions requires different organizational forms than in more stable times. It is well recognized that responsiveness, flexibility and innovation will be key corporate attributes for successful organizations. Information plays a critical role in improving these within today's organization. However, traditional organizational forms have significant limitations in supporting the information-based organization.

Information technology must share responsibility for much of the rigidity and inflexibility in organizations. By automating tasks IT cemented hierarchy with reporting systems, and rigidified behaviour through standardization. Indeed, often technology has not resulted in fundamental changes in how work is performed: rather it has allowed it to be done more efficiently. The irony is that IT can also help us break out of traditional modes of organizing and facilitate new organizational forms which previously would have been impossible. The challenge therefore is not only to consider new organizational forms but also to identify the critical issues that must be managed to allow this transformation to begin.

It is our intention to map out some of the themes relating to new ways of organizing which have been emerging over the past decade. We also want to clear up the confusion which is often encountered when reading such literature where similar ideas are often shrouded with new names. In particular, we explore the role of IT in facilitating new ways of organizing.

In order to place this chapter in perspective, we begin by briefly tracing developments in organization theory. This review is not intended to be exhaustive, but to give a flavour of just some of the main themes which have emerged over the years. We then explore some of the perspectives that have been proposed in the recent management literature, identify the main themes of each, the critical management issues and combine these into a framework which we believe is useful in giving direction to managing the transformation process.

Historical viewpoint

Whenever people have come together to accomplish some task, organizations have existed. The family, the church, the military are examples of early organizations. Each had their own structure, hierarchy, tasks, role and authority. The modern business organization, however, is a relatively recent phenomenon whose evolution can be traced to two important historical inferences: the industrial revolution and changes in the law.

The industrial revolution, which occurred largely in England during the 1770s, saw the substitution of machine power for human work and marked the beginning of the factory system of work. It spawned a new way of producing goods and offered opportunities which saw business increase to a scale never previously possible. The early Company Acts provided limited liability for individuals who came together for business purposes. Both these events led to the emergence of the professional manager, i.e. someone who managed the business but who did not own it. The increase in scale of organizations required a management structure and organizational form.

Early attempts to formulate appropriate organization form focused on determining the anatomy of formal organization. This so-called classical approach was built around four key pillars: division of labour, functional processes, structure, and span of control (Scott, 1961). Included here is the scientific management approach pioneered by Frederick Taylor (1911) which proposed one best way of accomplishing tasks. The objective was to increase productivity by standardizing and structuring jobs performed by humans. It spawned mass production with its emphasis on economies of scale. Although initially the concept applied to factory-floor workers, its application spread progressively in most organizational activity. Harrington Emerson took Taylor's ideas and applied them to the organizational structure with an emphasis on the organization's objectives. He emphasized, in a set of organizational ‘principles’ he developed, the use of experts in organizations to improve organizational efficiency (Emerson, 1917).

This mechanistic view was subsequently challenged by an emerging view stressing the human and social factors in work. Drawing on industrial psychology and social theory, the behavioural school argued that the human element was just as important. Themes such as motivation and leadership dominated the writings of subscribers to this view (e.g. Maslow, 1943, 1954; Mayo, 1971; McClelland, 1976).

Over the past 40 years organizational theorists have been concerned with the formal structure of organization and the implications these structures have on decision-making and performance. Weber (1947), for example, argued that hierarchy, formal rules, formal procedures, and professional managerial authority would increase efficiency.

Ever since Adam Smith (1910) articulated the importance of division of labour in a developing economy this notion has become ingrained in the design of organizations. Functionalism due to specialization is a salient feature of most organizations. Too often, however, this had led to an ineffective organization with each functional unit pursuing its own objectives. To overcome inherent weaknesses in this view, both the systems approach and the strategy thesis seek to integrate diverse functional unit objectives.

The systems movement originated from attempts to develop a general theory of systems that would be common to all disciplines (Bertalanfy, 1956). Challenging the reductionist approach of physics and chemistry the focus was on the whole being greater than the sum of the parts. Organizations were conceptualized as systems composed of subsystems which were linked and related to each other. Indeed, the systems approach is the dominant philosophy in designing organizational information systems. Systems theory also made the distinction between closed systems, i.e. those that focus primarily on their internal operations, and open systems which are affected by their interaction with their external environment. Early organizational theories tended to adopt a closed systems view. However, by adopting a more open approach it was clear that environmental issues were equally important.

The strategy movement which originated from Harvard Business School in the 1950s highlighted the importance of having an overall corporate strategy to integrate these various functional areas and how the organization can best impact its environment. The argument was that without an overall corporate strategy, each functional unit would pursue its own goals very often to the detriment of the organization as a whole. The decade of the 1970s saw many formalized, analytical approaches to strategic planning being proposed such as the Boston Consulting Group's planning portfolio (Henderson, 1979) and Ansoff's product portfolio matrix (Ansoff, 1979). Competitor analysis and the search for competitive advantage was the dominant theme of the 1980s, greatly influenced by the work of Porter (1980, 1985).

Chandler (1962), in his seminal study of US industries, saw structure following strategy. His thesis was that different strategies required different organizational structures to support them. Organizations that seek innovation demand flexible structures. Organizations that attempt to be low cost operators must maximize efficiency and the mechanistic structure helps achieve this. However, theorists such as Mintzberg (1979) and Thompson (1961) have emphasized the systemic aspect of structure, showing how structure can influence strategy and decision-making while hindering adaptation to the external environment.

The contingency theorists argued that the form an organization took is a function of the environment (Lawrence and Lorsch, 1970). Mintzberg, Miller and others talk about organizational configurations that bring strategy, structure, and context into natural co-alignment (Miller, 1986, 1987; Miller and Mintzberg, 1984). They argue that key forces or imperatives explain and give rise to many common configurations. The form an organization would take would reflect its dominant imperative.

We are not arguing that these forms or perspectives were inappropriate. In their time they represented the best forms that supported contemporary management thinking. For instance, despite its neglect of human aspects, scientific management yielded vast increases in productivity. However, the dynamic element which precipitated many of these approaches has also rendered them ineffective. Where are many of the excellent companies which Peters and Waterman (1982) wrote about 10 years ago? Perhaps they stuck to the knitting and ran out of wool. Perhaps the competition started using knitting machines or, indeed, the market now no longer has the need for wool products.

Recently Mintzberg (1991) has refined his thinking on organizational form and considered another view of organizational effectiveness, in which organizations do not slot themselves into established images so much as continually to build their own unique solutions to problems.

Given today's competitive conditions it is clear that one of the challenges facing management in the 1990s is to develop more dynamic organizations harnessing the power and capability of IT. What form such organizations will take is yet unclear. However, a picture of what this form will look like and how to initiate its development is beginning to emerge.

New perspectives

Over the past few years there have been a number of papers calling for the reappraisal of the form taken by organizations and for the widely accepted assumptions governing organizations to be re-evaluated. Fortune, International Management and Business Week have recently run articles looking at the organization of the 21st century indicating clearly that this topic is on the general management agenda as well as a focus of academic studies. In our research we have identified six perspectives which we feel represent current thinking on new ways of organizing. These are: network organizations; task focused teams; networked group; horizontal organizations; learning organizations; and matrix management.

In the sections that follow, we examine these perspectives briefly, with reference to key articles and research findings, and we identify salient themes. We then synthesize these themes into a framework which presents the key issues to be considered in the transformation process to a new organizational form.

Network organization

In their early work Miles and Snow (1978) discuss how market forces could be injected into traditional organizational structures to make them more efficient and responsive. In so doing they exhibit characteristics of delayering, downsizing, and operating through a network of market-sensitive business units. The driving force towards such an organization form are competitive pressures demanding both efficiency and effectiveness and the increasing speed necessary to adopt to market pressures and competitors’ innovations. In essence, the network organization is in response to market forces. Included in this perspective are outsourcing, value adding partnerships, strategic alliances and business network design.

With a network structure, one firm may research and design a product, another may engineer and manufacture it, distribution may be handled by another, and so on. A firm focuses on what it does well, outsourcing to other firms for resources that are required in addition (Figure 15.1). However, care must be exercised in outsourcing: Bettis et al. (1992) report that improper use of outsourcing can destroy the future of a business.

Three specific types of network organization are discussed by Snow et al. (1992):

• Internal network, typically arises to capture entrepreneurial and market benefits without having the company engage in much outsourcing. The basis logic is that internal units have to operate with prices set by the market instead of artificial transfer prices. They will constantly seek to innovate and increase performance.

• Stable network, typically employs partial outsourcing and is a way of injecting flexibility into the overall value chain.

• Dynamic network, provides both specialization and flexibility, with outsourcing expected.

Recent changes in the UK National Health Service (NHS) have seen the development of an internal market for health care as shown by General Practitioner Fund holders and the competitive role of NHS Trusts. The distinction between purchaser and provider organization represents the emergence of the networked organization. District Health Authorities now purchase health services based on the health needs assessment of the community from a variety of sources. Provider organizations need to be more cost and quality conscious.

Figure 15.1 Illustration of a network structure

In order for networks to exist, close relationships must be built with both suppliers and buyers along what Porter (1985) refers to as the value system. Johnson and Lawrence (1988) have coined the term value-adding partnerships (VAPs) to describe such relationships, which are more than just conventional electronic data interchange (EDI) links. They depend largely on the attitudes and practices of the participating managers. Asda Superstores and Procter and Gamble (P&G) now cooperate with each other beyond sending just orders and invoices via EDI. For instance Asda now provide forecasting information to P&G in an open way that was not previously management practice. In return, P&G are more responsive in meeting replenishment requirements. General Motors has renamed its purchasing department the ‘supplier development’ department.

For a network organization to exist it requires the capability of IT to facilitate communication and co-ordination among the various units. This is especially so when firms are operating in global markets. Further, IT facilitates VAPs; it does not create them.

Strategic alliances

Strategic alliances with both competitors and others in the industry value system are key strategies adopted by many organizations in the late 1980s (Hamel et al., 1989; Nakomoto, 1992; Ohmae, 1989). McKinsey's estimate that the rate of joint venture formation between US companies and international partners has been growing by 27 per cent since 1985 (Ernst and Bleeke, 1993).

Collaboration may be considered a low cost route for new companies to gain technology and market access (Hamel et al., 1989). Many European companies have developed pan-European alliances to help rationalize operations and share costs. Banks and other financial institutions use each others’ communication networks for ATM transactions. Corning, the $3 billion-a-year glass and ceramics maker, is renowned for making partnerships. Among Corning's bedfellows are Dow Chemicals, Siemens (Germany's electronics conglomerate) and Vitro (Mexico's biggest glass maker). Alliances are so central to Corning's strategy that the corporation now defines itself as a ‘network of organizations’. The multi-layered structure of today's computer industry and the large number of firms it now contains, means that any single firm, no matter how powerful, must work closely with many others. Often, this is in order to obtain access to technology or management expertise. A web of many joint ventures, cross-equity holdings and marketing pacts now entangles every firm in the industry.

Outsourcing

There is an argument that organizations should focus on core competencies and outsource all other activities. This has been a successful strategy followed by many companies. For example, Nike and Reebok have both prospered by concentrating on their strengths in designing and marketing high-tech fashionable sports footwear. Nike owns one small factory. Virtually all footwear production is contracted to suppliers in Taiwan, South Korea and other Asian countries. Dell Computers prospers by concentrating on two aspects of the computer business where the virtually integrated companies are vulnerable: marketing and service. Dell owns no plants and leases two small factories to assemble computers from outsourced parts. Figure 15.2 illustrates the relative success of electronics companies who outsource as against the vertically integrated companies.

Japanese financial-industrial groups are an advanced manifestation of a dynamic network. Called keiretsu, they are able to make long-term investments in technology and manufacturing, command the supply chain from components and capital equipment to end products and coordinate their strategic approaches to block foreign competition and penetrate world markets. There are also close relations between the banks and group companies, often cemented by banks holding company shares. It is interesting to note that many German companies have similar relations with their banks and very often bankers sit on the board of directors. Business Week (1992) recently reported that Ford has been making plans for what it would do with a bank if and when US legislation permits it to own one.

Figure 15.2 Outsourcing versus integration in electronics companies (Source:Fortune, 8 February 1993)

Business network redesign

The concept of business network redesign (BNR) has become increasingly popular where organizations seek to address major changes in the way they interface and do business with external entities. BNR represents using IT for ‘designing the nature of exchange among multiple participants in a business network’ (Venkatraman, 1991, p.140). The underlying assumption is that the sources of competitive advantage lie partly within a given organization and partly in the larger business network. Using IT, suppliers, buyers and competitors, are linked together via a strategy of electronic integration (Venkatraman, 1991).

BNR needs to be distinguished from EDI, which refers to the technical features, and inter-organizational systems (IOS), which refers to the characteristics of a specific system.

Redesigning an industry network is something akin to the dynamic structure of Snow et al. (1992) where an active relationship is cultivated between members of the network. Terms such as strategic alliance and value-adding partnerships are equally relevant here as they are with dynamic networks. Extending the industry network by introducing outsourcing is also feasible.

Task focused teams

Reich (1987) argues that a ‘collective entrepreneurship’ with few middle-level managers and only modest differences between senior management and junior staff is developing in some organizations. Drucker (1988) concurs and contends the organization of the future will be more information-based, flatter, more task oriented, driven more by professional specialists, and more dependent upon clearly focused issues. He proposes that such an organization will resemble a hospital or symphony orchestra rather than a typical manufacturing firm. For example, in a hospital much of the work is done in teams as required by an individual patient's diagnosis and condition. Drucker argues that these ad hoc decision-making structures will provide the basis for a permanent organizational form.

The emphasis on the team is a common theme which is emerging from the other perspectives on organizations. The team is seen as being the building block of the new organization and not the individual as has traditionally been the case. Katzenbach and Smith (1992) define a team as a ‘small number of people with complementary skills who are committed to a common purpose, performance goals and approach for which they hold themselves mutually accountable’. They suggest that there is a common link between teams, individual behaviour change and high performance.

High performance teams play a crucial role within Asea Brown Boveri (ABB), the Swedish–Swiss conglomerate. Here, their T50 programme is seeking to reduce cycle time by 50 per cent. These teams were as a result of a major change of attitude in the organization. Management by directives was replaced by management by goals and trust; individual piece-rate payment changed to group bonuses; controlling staffs moved to support teams; and there was one union agreement for all employees.

Drucker's notion of teams echoes Burns and Stalker's (1961) organic organization as opposed to the more mechanistic type of organization. Table 15.1 contrasts these views and presents their distinguishing organizational characteristics.

Increasingly, firms are using teams to coordinate development across functional areas and thus reduce product development times (Krachenberg et al., 1988; Lyons et al., 1990). For example, if we look at pharmaceuticals and telecommunications, the traditional sequential flow of research, development, manufacturing and marketing is being replaced by synchrony: specialists from all these functions working together as a team. Terms such as ‘concurrent engineering’, ‘design for manufacturability’, ‘simultaneous engineering’, ‘design-integrated manufacturing’ and ‘design-to-process’ are being used increasingly in organizations to incorporate cross-functional teams and methodologies to integrate engineering and design with manufacturing process (Dean and Susman, 1989; Griffin et al., 1991).

Since 1990 British Aerospace (BAe) has been actively promoting simultaneous engineering in its engineering division, having examined a number of initiatives. They saw the total quality management (TQM) message being difficult to get across and not very relevant to engineering. While process review was appealing it was limited in scope if only done inside engineering. For BAe, multifunctional teams are key to the success of their programmes. There is a clear focus on goals, the top level plan is robust to change, dependencies are less critical as they are dealt with by the team, members develop mutual role acknowledgement generating an achievement culture.

However, the notion of teams is nothing new. Value analysis and value engineering have been popular in many manufacturing firms since the 1950s. Although employees from various disciplines were brought together, the focus was on products; the new conceptualization is much broader. What is new about Drucker's vision is the role that IT will play. IT greatly facilitates task-based teams especially in enabling geographically dispersed groups to improve the coordination of their activities through enhanced electronic communication. Rockart and Short (1989) see self-governing units as being one of the impacts of IT.

Table 15.1 Mechanistic versus organic organizations

Element |

Mechanistic organization |

Organic organization |

Channel of communication |

Highly structured Controlled information flow |

Open; free flow of information |

Operating style |

Must be uniform and restricted |

Allowed to vary freely |

Authority for decisions |

Based on formal line-management position |

Based on expertise of the individual |

Adaptability |

Reluctant, with the insistence holding fast to tried and tested principles in spite of changes in circumstances |

Free, in response to changing circumstances |

Work emphasis |

On formal, laid down procedures |

On getting things done unconstrained by formality |

Control |

Tight, through sophisticated control systems |

Loose and informal, with emphasis on cooperation |

Behaviour |

Constrained, and required to conform to job description |

Flexible and shaped the individual to meet the needs of the situation and personality |

Participation |

Superiors make decisions with minimum consultation and minimum involvement of subordinates |

Participation and group consensus frequently used |

Source: D. P. Slevin and J. G. Colvin (1990).

The networked group

According to Charan (1991) a network is a recognized group of managers assembled by the CEO and the senior executive team. The membership is drawn from across company functional areas, business units, from different levels in the hierachy and from different locations. Such a network brings together a mix of managers whose business skills, personal motivations, and functional expertise allow them to drive a large company like a small company. The foundation of a network is its social architecture, which differs in important ways from structure. As such, it differs from Miles and Snow's (1987) concept of network in that it is internally focused.

• networks differ from teams, cross-functional task forces or other assemblages designed to break hierarchy

• networks are not temporary; teams generally disband when the reason they were assembled is accomplished

• networks are dynamic; they do not merely solve problems that have been defined for them

• networks make demands on senior management.

In most organizations, information flows upwards and is thus prone to distortion and manipulation. In a network, especially a global network that extends across borders, information must be visible and simultaneous. Members of the network receive the same information at the same time. Not only must hard information be presented, but also more qualitative information, not just external information but members’ experiences, successes, views and problems.

The single most important level for reinforcing behaviour in networks is evaluation. Every manager, regardless of position or seniority, responds to the criteria by which he or she is evaluated, who conducts the review, and how it is conducted. For a network to survive top management must focus on behaviour and horizontal leadership: Does a manager share information willingly and openly? Does he or she ask for and offer help? Is he or she emotionally committed to the business? Does the manager exercise informal leadership to energize the work of sub-networks?

Horizontal organizations

Questioning the validity of the vertical orientation of organizations a number of writers have proposed what they call the horizontal organization. Such organizations have clearly defined customer facing divisions and processes to improve performance.

Ostrof and Smith (1992) contend that performance improvements will be difficult to achieve for companies organized in a traditional vertical fashion. While the advantage of vertical organizations may be functional excellence it suffers from the problem of coordination. With many of today's competitive demands requiring coordination rather than functional specialization, traditional vertical organizations have a hard time responding to the challenges of the 1990s.

In the horizontal organization, work is primarily structured around a small number of business processes or work flows which link the activities of employees to the needs and capabilities of suppliers and customers in a way that improves the performance of all three.

Ostrof and Smith (1992) list ten principles at the heart of horizontal organizations which are listed in Table 15.2. Although not arguing for the replacement of vertical organizations they recommend that each company must seek its own unique balance between the horizontal and vertical features needed to deliver performance.

Table 15.2 Blueprint for a horizontal organization

• Organize around process not task |

• Flatten hierarchy by minimizing the subdivision of work flows and non-value-added activities |

• Assign ownership of processes and process performance |

• Link performance objectives and evaluation to customer satisfaction |

• Make teams, not individuals, the principal building blocks of organization performance and design |

• Combine managerial and non-managerial activities as often as possible |

• Treat multiple competencies as the rule, not the exception |

• Inform and train people on a ‘just-in-time to perform’ basis not on a ‘need to know’ basis |

• Maximize supplier and customer contact |

• Reward individual skill development and team performance, not individual performance |

Source: Ostrof and Smith (1992).

BT was one of the early companies to recognize the ineffectiveness of the traditional vertical organization. Through project Sovereign and its process management initiatives, BT has reorganized itself into customer facing divisions and has embarked on significant performance improvement activity. Senior managers are now process owners with responsibility for service delivery as opposed to being functional heads. In a recent interview, BT's chairman revealed that AT&T, MCI and Deutsche Telecom have all restructured themselves following the BT model, setting up distinct business and personal communication divisions and separating network management from customer facing elements (Lorenz, 1993).

The horizontal design is seen as a key enabler to organizational flexibility and responsiveness. Time is critical in today's fast changing business environment (Stalk, 1988). Organizations need to be able to respond to customer demands with little delay and just-in-time (JIT) is just one manifestation of this. Kotler and Stonich (1991) have coined the term ‘turbo marketing’ to describe this requirement to make and deliver goods and services faster than competitors.

Multinational corporations face additional challenges making horizontal organizations work. As a result of their research Poynter and White (1990) have identified five activities needed to create and maintain a horizontal organization spanning a number of countries:

1 Create shared values. Collaborative decision making is not possible unless an organization has shared decision premises, a common culture or set of business values.

2 Enabling the horizontal network. To counteract the tendency for an organization to (re)assert vertical relationships, initiatives, such as giving headquarters’ executives dual responsibilities, should be put in place.

3 Redefine managers’ roles. The skills, abilities and approaches required for the horizontal organization are different than those from conventional vertical organizations. Fundamentally, senior managers must create, maintain and define an organization context that promotes lateral decision making oriented towards the achievement of competitive advantage world-wide.

4 Assessing results. Assignment of performance responsibility and availability for results within horizontal organizations is problematic. The people involved in horizontal collaborative efforts change over time and their individual contributions are difficult to measure.

5 Evaluating people. Evaluating executives in terms of their acceptance and application of a common set of beliefs is particularly appropriate for international management because of the shortcomings of orthodox vertical measures of evaluating people.

Business process redesign

This focus on process has become an important management focus over the past few years, with business process redesign (BPR) figuring highly on many corporate agendas (Dumaine, 1989; Butler Cox Foundation, 1991; Heygate and Breback, 1991; Kaplan and Murdock, 1991). BPR first entered the management nomenclature as a result of research conducted at MIT (Davenport and Short, 1990; Scott Morton, 1991). In their ‘Management in the 1990s’ research project they identified BPR as an evolutionary way of exploiting the capabilities of IT for more than just efficiency gains (Scott Morton, 1991).

Consider how IT is currently implemented in organizations: localized exploitation – typically to improve the efficiency of a particular task; and internal integration – integration of key internal applications to establish a common IT platform for the business.

With an internal focus, both of the above overlay on the existing tasks and activities thus retaining existing organization structures. This is what Hammer (1990) has referred to as ‘paving the cow path’. Most IT systems design methodologies reinforce this view. BPR, however, questions the validity of existing ways of organizing work and is concerned with redesigning the organization around fundamental business processes.

BPR is the analysis and design of work flows and processes within organizations. It has also been called business re-engineering, process re-engineering, process innovation and core process redesign. The crucial element is the concentration on process rather than events or activities. A business process can be defined as a set of related activities that cuts across functional boundaries or specializations in order to realize a business objective. A set of processes is a business system.* Processes are seen to have two important characteristics: (i) they have customers, that is, processes have defined business outcomes and there are recipients of outcomes (customers can be either internal or external); (ii) they cross functional boundaries, i.e. they normally occur across or between organizational functional units. Examples include research and development, mortgage application appraisal, developing a budget, ordering from suppliers, creating a marketing plan, new product development, customer order fulfilment, flow of materials (purchasing, receiving, manufacturing).

Most companies still operate with thousands of specialists who are judged and rewarded by how well they perform their separate functions – with little knowledge or concern about how these fit into the complex process of turning raw material, capital and labour into a product or service. Activities and events are thus snap shots of a larger process. The Japanese realized that focusing on individual activities in the value chain was not sufficient. Superior performance was gained by focusing on the total process. So while Western managers focused on managing inventories, the Japanese saw that eliminating delays in the production process was the key to reducing instability, decreased cost, increased productivity and service.

However, BPR is not a new concept: its origins can be found in work study organization and methods (O&M) of the 1960s. It also has its roots in the quality revolution where the stress is on improving quality by identifying, studying, and improving the processes that make and deliver a product or service. The scope of quality management is often narrow, however, with responsibility lying in functional areas and thus not as rigorous as process redesign. The emphasis of BPR is on how different processes are carried out. The objective is to re-evaluate these processes and to redesign them so that they are aligned more closely to business objectives.

The philosophy of BPR is fundamentally different from the systems approach with which it might be confused. The systems approach is a theoretical framework which recognizes the interdependence of functional units and seeks to integrate them by integrating information flows. With BPR the emphasis is on processes which transcend functional units. It seeks to challenge existing assumptions relating to how the organization operates. It emphasizes a top down customer focused approach often using IT as the mechanism for coordination and control.

The benefits of taking a process approach is to reduce costs, increase quality, while increasing responsiveness and flexibility. IT is often the essential ingredient by which the process concept can be turned into a practical proposition. Processes can also be redesigned to take account of the latest developments in technology.

Learning organizations

There has been renewed interest over the past few years in the learning organization (Garvin, 1993; Hayes et al., 1988; Kochan and Useem, 1992; Stata, 1989; Senge, 1990a, 1990b, 1991; Quinn Mills and Friesen, 1992). The argument is that current patterns of behaviour in large organizations are typically ‘hard wired’ in structure, in information systems, incentive schemes, hiring and promotion practice, working practices, and so on. To break down such behaviour, organizations need the capability to harness the learning capabilities of their members. The learning organization is able to sustain consistent internal innovation or ‘learning’ with the immediate goals of improving quality, enhancing customer or supplier relationships, or more effectively executing business strategy (Quinn Mills and Friesen, 1992). This notion has similarities to the work of Argyris (1976, 1982).

Argyris identified two types of learning that can occur in organizations: adaptive learning and generative learning. Typically, organizations engage in adaptive or ‘single-loop’ learning and thus cope with situations within which they find themselves. For example, comparing budgeted against actual figures and taking appropriate action. Generative or double-loop learning, however, requires new ways of looking at the world, challenging assumptions, goals, and norms.

Implementing executive information systems (EIS) typically requires users to first adapt to using technology to obtain their required information, i.e. adaptive learning. However, to exploit the potential of EIS fully, systems users must proactively develop and test models of the use of EIS in the management process, i.e. double-loop learning. Zuboff's (1988) work refers to the criticality of line managers developing spatial models to exploit fully the potential of information systems available to them.

Mintzberg (1973) claims that the way executives use information that they collect is to develop mental images – models of how the organization and its environment function. Hedberg and Jonsson (1978) assert that to be able to operate at all, managers look at the world and intuitively create a myth or theory of what is happening in the world. With this in mind, they create a strategy to react to this myth so that they can form defence networks against information overflows from other myths and map information into definitions of their situations. They then test the strategy out on the world and evaluate its success.

Mason and Mitroff (1981) suggest that assumptions are the basic elements of a strategist's frame of reference or world view. Since assumptions form the basis of strategies, it is important that they be consistent with the information available to strategists (Schwenk, 1988). However, most decision-makers are unaware of the particular set of assumptions they hold and of methods that can help them in examining and assessing the strength of their assumptions (Mason and Mitroff, 1981; Mitroff and Linstone, 1993). The accuracy of these assumptions may be affected by their cognitive heuristics and biases. DeGeus (1988) suggests that planning is learning. However, planning is based on assumptions that should be constantly challenged.

Organization learning theory suggests that learning often cannot begin until unlearning has taken place (Burgelman, 1983). This requires a realization of the current position. Senge (1990a) talks about creative tension where a vision (picture of what might be) of the future pulls the organization from its current reality position. This is more than adaptation and is very much proactive.

Quinn Mills and Friesen (1992) list three key characteristics of a learning organization: (i) It must make a commitment to knowledge. This includes promoting mechanisms to encourage the collection and dissemination of knowledge and ideas throughout the organization. This may include research, discussion groups, seminars, hiring practices. (ii) It must have a mechanism for renewal. A learning organization must promote an environment where knowledge is incorporated into practices, processes and procedures. (iii) It must possess an openness to the outside world. The organization must be responsive to what is occurring outside of it.

Many organizations have implemented information systems in an attempt to improve organizational learning. For example, groupware products such as Lotus Notes or IBM's TeamFocus facilitate the sharing of ideas and expertise within an organization.

At Price Waterhouse they have 9000 employees linked together using Lotus Notes. Auditors in offices all over the world can keep up to date on relevant topics; anyone with an interest in a subject can read information and add their own contribution. By using groupware, Boeing has cut the time needed to complete a wide range of products by an average of 90 per cent or to one-tenth of what similar work took in the past.

Over the long run, superior performance depends on superior learning. The key message is that the learning organization requires new leadership skills and capabilities. The essence of the learning organization is that it is not just the top that does the thinking; rather it must occur at every level. Hayes et al. (1988) argue that in effect the organization of the 1990s will be a learning organization, one in which workers teach themselves how to analyse and solve problems.

Matrix management

Bartlett and Ghoshal (1990) argue that strategic thinking has far outdistanced organizational capabilities which are incapable of carrying out sophisticated strategies. In their search for a more effective form they argue that companies that have been most successful at developing multi-dimensional organizations first attend to the culture of the organization; then change the systems and relationships which facilitate the flow of information. Finally, they realign the organizational structure towards the new focus.

They call this matrix management although it is different from the 1970s concept of matrix management. They argue that while the notion of matrix management had appeal, it proved unmanageable – especially in an international context. Matrix management tended to pull people in several directions at once. Management needs to manage complexity rather than minimize it.

They contend that the most successful companies are those where top executives recognize the need to manage the new environmental and competitive demands by focusing less on the quest for an ideal structure and more on developing the abilities, behaviour and performance of individual managers. This has echoes of Peters and Waterman's (1982) bias for action.

People are the key to managing complex strategies and organizations. The ‘organizational psychology’ needs to be changed in order to reshape the understanding, identification, and commitment of its employees. Three principal characteristics common to those that managed the task most effectively are identified:

• Build a shared vision. Break down traditional mindsets by developing and communicating a clear sense of corporate purpose that extends into every corner of the company and gives context and meaning to each manager's particular roles and responsibilities.

• Develop human resources. Turn individual manager's perceptions, capabilities, and relationships into the building blocks of the organization.

• Co-opting management efforts. Get individuals and organizational groups into the broader vision by inviting them to contribute to the corporate agenda and then giving them direct responsibility for implementation.

While matrix management as a structural objective (the 1970s conceptualization) may not be possible, the essence can still be achieved. Management needs to develop a matrix of flexible perspectives and relationships in their mind.

A framework

Each of the perspectives presented above challenges traditional views of organizations. The arguments are based around a total re-evaluation of the assumptions which underlie organizational form, i.e. the best mix of structure, systems, management style, culture, roles, responsibilities and skills. From the different viewpoints presented we can get a glimpse of the characteristics of the 21st century organization. Key characteristics of these organizations are:

• constantly challenging traditional organizational assumptions

• evolution through learning at all levels

• multi-disciplinary self-managing teams with mutual role acknowledgement

• a reward structure based on team performance

• increased flexibility and responsiveness

• an achievement rather than blame culture

• an organizational wide and industry wide vision

• a vision of what kind of organizational form is required

• process driven with a customer focus

• fast response with time compression

• information based

• IT enabled.

This list of characteristics is perhaps not surprising. They have been advocated in both the academic and general management literature over recent years. Of course we cannot categorically say that organizations structured in a traditional way will not survive, although it is hard to see them thriving. We do suggest, however, that an organization critically reviews its form to determine whether it should incorporate some of these characteristics and the extent to which these should be adopted.

While we do have a destination in general terms there are three key issues which we feel need to be addressed in practice:

• The vision. The precise destination for a particular organization, i.e. where do we need to be? This is very much the visioning process where organizational requirements are determined. The precise final form will be unique to each organization depending on the organization itself and the context within which it exists. While form will depend on the strategy of the business many organizations fail to consider the organization's ability to deliver this strategy. This must go beyond defining structure and incorporate culture, reward systems, human resource requirements, etc. These in some sense could be seen as representing the organization form's critical success factors (CSFs).

• Gap analysis. A critical understanding of where the organization is now in relation to this organization vision should be established. The role which IT will play in the new organization should also be assessed. In short, we are attempting to describe the nature of the journey that needs to be undertaken. The concern here is with planning the business transformation.

• Managing the migration. How do we manage the migration from the existing organization form to a new form? The concern here is with the change management process which seeks to ensure the successful transition from the old form to the new form. A particularly difficult area to tackle here is an organization's ability to incorporate information systems/information technology (IS/IT) developments successfully where these involve significant business change.

A recurring problem faced by any organization engaging in redesign is determining an appropriate approach. Perhaps it is too ambitious to expect an existing method to be comprehensive enough to deal with all the issues involved. All organizations are different and changing an organization's form is more complex than simply identifying core processes and leveraging IT as many of the articles imply. The critical issue is to address broader themes such as culture, management development, IS/IT development, skills, reward systems, etc. These notions are complex, however, and do not subscribe to neat techniques but need to be managed carefully.

Traditionally, we have aligned IT with the business strategy, without much consideration to people issues or the organizational capability to deliver (Galliers, 1991). Macdonald (1991, 1993) provides a useful model highlighting interrelationships between the business strategy, IS/IT and organizational processes. While checking for alignment of these variables and identifying issues, he outlines the topography but fails to provide any help in reaching the required destination.

It is much easier to embellish the characteristics of the organization of the 1990s than to define clear frameworks to achieve these characteristics. What we do not have is a road map to translate these aspirations into a workable design. Additionally, the road map needs to identify potential hazards and obstacles that are likely to be encountered en route and how these are to be dealt with.

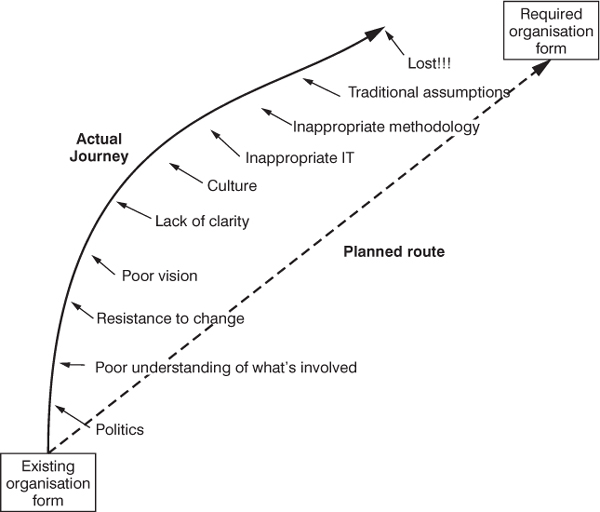

Figure 15.3 illustrates some of the problems faced by an organization attempting to move from a current form to a new one. There are many forces which will drive it off course and it is essential that these are managed in order successfully to achieve the desired goal.

A key point is that, even when we identify the destination, the challenge is to negotiate the journey. Any route planning needs to explicitly address these issues. Questioning an organization's fundamental approach to the way that it does business can be risky and may confront too many entrenched interests among managers and employees to be worth doing unless an organization is in dire trouble. By then a complete overhaul is often too late to be of much use. It is often difficult to put across the idea that a successful organization should radically reconsider how it does business, however.

The issues can be fundamental and might include inappropriate IS/IT, management myopia, resistance, poor vision, etc. The stakes are high as is the need to manage them well particularly as many of them are central to people's value systems, such as power, politics and rewards. The characteristics of the new organization form, as described earlier, have a significantly different emphasis than those required by traditional forms, e.g. flexibility, process oriented, fast cycle response. In planning the migration we believe a fundamentally different paradigm should be used for managing this transition.

Figure 15.3 Roadblocks and obstacles to a new organization

We have continually failed to provide an integrating framework to help in coordinating change and uncertainty. This uncertainty requires continual learning on the part of the organization both in terms of its destination and how to get there. A new multifaceted approach which integrates business strategy, IS/IT, organization design and human resources is needed.

In Figure 15.4 we present a framework for business transformation which we have found useful when approaching issues associated with the migration towards a new organizational form. This framework expands on the model of IS/IT strategy formulation popularized by Earl (1989), Galliers (1991) and Ward et al. (1990) and incorporates organizational and implementation issues. It is structured around the triumvirate of vision, planning and delivery with considerable iteration between planning and delivery to ensure that the required form is being met.

Figure 15.4 Business transformation framework

The underlying premise of this framework questions the traditional sequential IS/IT planning model where business strategy drives IS strategy which determines the organization's IT strategy. It incorporates an organization's ability to deliver fundamental business change, recognizing that increasingly this change is being enabled by IT.

Vision

The requirement for a clear business vision is well known and espoused by many scholars on strategy. However, equally important is a vision of the organization form that is necessary to deliver and support the achievement of that strategy. This organizational vision needs to be more than the traditional structural perspective of centralization, differentiation and formalization. Rather, it should define the organizational form CSFs in relation to culture, teamwork, empowerment, skills, reward systems and management style.

We define two types of visioning: business vision and organization vision. While business vision remains as currently practised by many organizations, the organization vision identifies the attributes and characteristics of the organization to achieve this business vision. Grand Metropolitan, for example, has an organization vision based on organizational competencies which are crucial to deliver its strategies. They believe that managerial and organizational competencies are more enduring and difficult to emulate than, what they call, ‘the traditional structural strategies’ of a conglomerate such as product portfolio, production sites and acquisition strategies. Having looked at the organizational CSFs for home banking, Midland Bank decided that their existing organization was not an appropriate vehicle for a home banking/telebanking organization, hence First Direct was set up. Acting ‘independently’ of the parent it articulated an organization vision of what was required organizationally to deliver this new service.

Business transformation planning

Business transformation planning demands two key activities: planning the organization strategy and developing an information systems strategy which facilitates this strategy but which is also closely aligned to business requirements. The conventional IS/IT planning framework does not explicitly consider the organization's ability and capability to deliver the business strategy.

A key concern of business transformation planning is a critical evaluation and understanding of the existing organization's characteristics and capabilities of how the current IS/IT strategy is being used to support them. The gap between existing and required can then be determined. It is important to emphasize that the relationship between both the organizing strategy and the IS strategy is bi-directional.

Organization strategy

An organization strategy involves more than simply considering the arrangement of people and tasks: what we typically call structure. It incorporates all the characteristics of organizational form which are encapsulated in the CSFs articulated in the organization vision. This will include what is needed in terms of skills, styles, procedures, values and reward systems. The organization strategy operationalizes these notions and will become the blueprint for the change management process.

A number of approaches to understand and evaluate aspects of organizational form have been proposed by many authors. For example, Johnson (1992) presents the cultural web as a means of assessing existing organization culture. The strategic alignment process of Macdonald is also useful in reviewing the alignment of strategy, organizational processes and IT.

It is important also at this stage to consider the opportunities which IT offers in relation to organizing work. Groupware, for example, greatly enhances team work and can lead to greater productivity. IT facilitates more customer-oriented service as the systems provide more comprehensive information. BT now has one point of contact with both business and personal customers. Queries can be dealt with more efficiently and work routed to the appropriate area where necessary. First Direct is only possible due to IT, which allows the telephone clerks to give almost immediate response to requests.

Distance effects are also minimized due to IT. People from diverse geographical locations can now work together in the same team creating the boundary-less corporation. Multinational corporations can adopt a more efficient horizontal structure. Technology is also blurring the distinction between organizations. With technology, business processes can now transcend traditional organizational boundaries. Strategic alliances and value added partnerships are becoming key strategies for many organizations and IT has a major role to play in facilitating the communication and coordination necessary to make these pay off.

Changing the way things are done will usually require investment in human resource initiatives in order to enhance team skills, customer service skills, information sharing and organization wide values. These can become critical barriers and deflect an organization in migrating to the new form.

IS strategy

Although the organization of the 1990s will be information-based, we believe that designing systems solely around information flows is flawed. The emphasis will not be on how tasks are performed (faster, cheaper, better) but rather in how firms organize the flow of goods and services through value-added chains and systems. Organizing around business processes permits greater focus on what the organization is trying to achieve and not on operationalizing objectives around existing activities.

IT has, for too long, been seen as a tool for improving efficiency and effectiveness. The new organizational shapes are dependent on the capability of information and communication technologies. EIS, for example, permit senior managers to delegate and decentralize while still maintaining overall control.

As mentioned above, aligning IS strategy with business strategy is only half the story. The IS strategy must also be compatible with how the business is organized to meet the business strategy. As a result of their research, Hayes and Jaikumar (1988) contend that acquiring any advanced manufacturing system is more like replacing an old car with a helicopter. By failing to understand and prepare for the revolutionary capabilities of these systems, they will become as much an inconvenience as a benefit – and a lot more expensive.

During the business transformation planning phase, the existing organization form and the existing IS/IT strategy will be reviewed and the transformation plans developed. The change strategy will be mapped out in terms of approaches to be used, the rate of change, how it is to be achieved, milestones and how the road-blocks and obstacles are to be negotiated. Of critical concern, is a clear statement of the final destination.

Change management process

Migration to the new form is a change process which implements the plans in the most appropriate way.

Organizational redesign

Organization redesign involves managing the migration to the new organizational infrastructure. In particular:

• the change from function to process orientation

• developing and implementing new ways of working

• redefining roles and responsibilities in line with the migration.

These must be closely aligned with human resource (HR) initiatives and IS/IT development.

Human resource initiatives

Central to the successful management change are the HR initiatives which are put in place. Many organizations try to accomplish strategic change by merely changing the system and structure of their organization. This is a recipe for failure. HR initiatives will be incorporated within the organization's overall HR strategy and will include education, management development programmes, training and reward structures. Probably one of the greatest barriers to the management of change is the assumption that it simply happens or that people must simply change because it is necessary to do so (Peppard and Steward, 1993).

HR development has a crucial challenging role to play in successfully ‘orchestrating’ strategic culture change (Burack, 1991). US Labor Secretary Robert Reich recently urged American companies to treat their workers as assets to be developed rather than as costs to be cut.

Many barriers to change are not tangible, and although are propagated by organizations, they exist in the mind of the manager. Indeed, such an initiative would also contribute towards the learning capability of organizations, although there is a distinction between learning as an individual phenomenon and an organization's capability to learn by the systematization of knowledge.

Management needs to be taught new skills, particularly interpersonal skills and how to work in teams. New organizational forms also require managers to carry out new tasks and roles. The informate phenomenon identified by Zuboff (1988) increasingly requires empowerment and wider responsibility for decision-making to be given to organization members.

Changing technology places additional strains on management. Education for new technology is important for two reasons: (i) strategically, to give a strategic view of IT; and (ii) organizationally – it is arguable that the chief contribution of managers to the competitive nature of organizations will be thinking creatively about organizational change.

Motorola spends $120 million every year on education, equivalent to 3.6 per cent of payroll. It calculates that every $1 it spends on training delivers $30 in productivity gains within three years. Since 1987, the company has cut costs by $3.3 billion – not by the normal expedient of firing workers, but by training them to simplify processes and reduce waste. For example, the purchasing department at the automotive and industrial electronics group set up a team called ET/VT = 1 because it wanted to ensure that all ‘elapsed time’ (the hours it took to handle a requisition) was ‘value time’ (the hours when an employee is doing something necessary and worthwhile). The team managed to cut from seventeen to six the number of steps in handling a requisition. Team members squeezed average elapsed time from thirty hours to three, enabling the purchasing department to handle 45 per cent more requests without adding workers (Henkoff, 1993).

Scott Morton (1991) contends that one of the challenges for an organization in the 1990s is understanding one's culture and knowing that an innovative culture is a key first step in a move towards an adaptive organization. Managers have a core set of beliefs and assumptions which are specific and relevant to the organization in which they work and are learned over time. The culture of the organization propagates many of the traditional assumptions which underlie organizations and also makes it extremely difficult to change. This is not something that is unique to organizations but is firmly based in a society which fosters individuality. Everyone tends to be pigeonholed from an early age and it is only to be expected that it be carried to working life. Management education itself promotes specialization by teaching functional courses.

Hirschhorn and Gilmore (1992) have identified four psychological boundaries which managers must pay attention to in flexible organizations: authority boundary, task boundary, political boundary, and identity boundary. Let us briefly explore each of these.

• Authority. In more flexible organizations, issuing and following orders is no longer good enough. The individual with formal authority is not necessarily the one with the most up-to-date information about a business problem or a customer need. Subordinates must challenge in order to follow while superiors must listen in order to lead.

• Task. In a team environment, people must focus not only on their own work, but also on what others do.

• Political. In an organization, interest groups sometimes conflict and managers must know how to negotiate productively.

• Identity. In a workplace where performance depends on commitment, organizations must connect with the values of their employees.

An innovative HR policy that supports organizational members as they learn to cope with a more complex and changing world is required. New criteria to measure performance are also needed. It is no use fostering cross-functional teams if evaluation and reward are based on individual criteria. Every manager, regardless of position or seniority, responds to the criteria by which he or she is evaluated, who conducts the review, and how it is conducted.

IS/IT development

The approach to IS/IT development needs to take cognizance of the business objective as described in the IS and organization strategies. Most of the perspectives discussed above depend on harnessing the power of IT to make it all possible. However, it is important that the overall business applications of which IT developments are part are owned by business management. This is because their key involvement in requirements definition, data conversion, new working practices, implementation and realizing the benefits.

IS/IT developments are not all the same and the approach adopted needs to be related to business objectives. Ward et al. (1990) propose the use of the applications portfolio which indicates appropriate management strategies, particularly in relation to financial justification, IS/IT management style, the use of packages, outsourcing, contractors and consultants. This portfolio approach makes more effective the use of the IT resource in relation to business requirements.

Delivering the IS strategy is traditionally seen as a purely technological issue. However, of key concern are the changes which accompany any IT implementation (Galliers, 1991). People issues are key reasons why many IT investments fail to realize benefits (Scott Morton, 1991). Involvement and ownership in the design and implementation are seen as critical for the success of any IT development. The training needs required for the new technology must be integrated when appropriate with the HR initiatives.

Conclusions

The traditional organization has been criticized by many writers on organization. Alternatives have been proposed but these merely represent a destination without a clear road map setting the direction rather than presenting a map and route to negotiate the obstacles to be encountered along the way.

In this chapter we have presented a framework to help organizations in planning and implementing their journey. This framework is constructed around the triumvirate of vision, planning and delivery with considerable iteration between all stages. This helps with the management of uncertainty and reconfirms the destination.

Crucial in the visioning stage are the critical success factors of the new organizational form which define the requirements of critical issues such as culture, teamwork, people, skills, structure, reward systems and information needs. This provided the basis for the gap analysis highlighting the nature of the journey to be undertaken and the subsequent delivery initiatives of HR, organization design and IS/IT. Central to our framework are the interactions between HR, organization design and IS/IT in a way that enables the delivery of the new organization form with its CSFs.

Fundamentally, we believe that managing the migration to the new organization form will require a significant amount of senior management time, energy and initiative. If this is not forthcoming because management is ‘too busy’, the likelihood of success is minimal. This must be the first paradigm to be broken.

References

Ansoff, H. I. (1979) Strategic Management, Macmillan, London.

Argyris, C. (1976) Single-loop and double-loop models in research on decision-making. Admin. Sci. Quarterly, 21, 363–375.

Argyris, C. (1982) Reasoning, Learning and Action: Individual and Organization, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco.

Bartlett, C. A. and Ghoshal, S. (1990) Matrix management: not a structure, a frame of mind. Harvard Bus. Rev., July–August, 138–145.

Bertalanfy, L. von (1956) General systems theory. General Systems, I, 1–10.

Bettis, R. A., Bradley, S. P. and Hamel, G. (1992) Outsourcing and industrial decline. Acad. Manage. Exec., 6(1) 7–16.

Burack, E. H. (1991) Changing the company culture – the role of human resource development. Long Range Planning, 24(1), 88–95.

Burgelman, R. A. (1983) A process model of internal corporate venturing in a diversified major firm. Admin. Sci. Quarterly, 28(2), 223–244.

Burns, T. and Stalker, G. M. (1961) The Management of Innovation, Tavistock Publications, London.

Business Week (1992) Learning from Japan. Business Week, 27 January, 38–44.

Butler Cox (1991) The role of information technology in transforming the business. Research Report 79, Butler Cox Foundation, January.

Chandler, A. D. (1962) Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the American Industrial Enterprise, The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Charan, R. (1991) How networks reshape organizations – for results. Harvard Bus. Rev., September–October, 104–115.

Davenport, T. H. and Short, J. E. (1990) The new industrial engineering: information technology and business process redesign. Sloan Manage. Rev., Summer, 11–27.

Dean, J. W. and Susman, G. I. (1989) Organizing for manufacturable design. Harvard Bus. Rev., January–February, 28–36.

deGeus, A. P. (1988) Planning as learning. Harvard Bus. Rev., March–April, 70–74.

Drucker, P. F. (1988) The coming of the new organization. Harvard Bus. Rev., January–February, 45–53.

Dumaine, B. (1989) What the leaders of tomorrow see. Fortune, 3 July, 24–34.

Earl, M. J. (1989) Management Strategies for Information Technology, Prentice-Hall, Hemel Hempstead, UK.

Emerson, H. (1917) The twelve principles of efficiency. Eng. Mag., xviii.

Ernst, D. and Bleeke, J. (eds) (1993) Collaborating to Compete: Using Strategic Alliances and Acquisitions in the Global Marketplace, John Wiley, New York.

Galliers, R. D. (1991) Strategic information systems planning: myths, reality and guidelines for successful implementation. Europ. J. Inf. Sys., 1(1), 55–64.

Garvin, D. A. (1993) Building a learning organisation. Harvard Bus. Rev., July–August, 78–91.

Griffin, J., Beardsley, S. and Kugel, R. (1991) Commonality: marrying design with process. The McKinsey Quarterly, Summer, 56–70.

Hamel, G., Doz, Y. L. and Prahalad, C. K. (1989) Collaborate with your competitors and win. Harvard Bus. Rev., January–February, 143–154.

Hammer, M. (1990) Reengineering work: don't automate, obliterate. Harvard Bus. Rev., July–August, 104–112.

Hayes, R. H. and Jaikumar, R. (1988) Manufacturing's crisis: new technologies, obsolete organisations. Harvard Bus. Rev., September– October, 77–85.

Hayes, R. H., Wheelwright, S. C. and Clark, K. B. (1988) Dynamic Manufacturing: Creating the Learning Organization, The Free Press, New York.

Hedberg, B. and Jonsson, S. (1978) Designing semi-confusing information systems for organizations in changing environments. Accounting, Organizations, and Society, 3(1), 47–64.

Henderson, B. D. (1979) Henderson on Corporate Strategy, Abt Books, Cambridge, MA.

Henkoff, R. (1993) Companies that train best. Fortune, 22 March, 40–46.

Heygate, R. and Brebach, G. (1991) Corporate reengineering. The McKinsey Quarterly, Summer, 44–55.

Hirschhorn, L. and Gilmore, T. (1992) The new boundaries of the ‘boundaryless’ company. Harvard Bus. Rev., May–June, 104–115.

Johnson, G. (1992) Managing strategic change – strategy, culture and action. Long Range Planning, 25(1), 29–36.

Johnson, R. and Lawrence, P. R. (1988) Beyond vertical integration – the rise of the value-adding partnership. Harvard Bus. Rev., July–August, 94–101.

Kaplan, R. B. and Murdock, L. (1991) Core process redesign. The McKinsey Quarterly, Summer, 27–43.

Katzenbach, J. R. and Smith, D. K. (1992) Why teams matter. The McKinsey Quarterly, Autumn, 3–27.

Kochan, T. A. and Useem, M. (eds) (1992) Transforming Organizations, Oxford University Press, New York.

Kotler, P. and Stonich, P. J. (1991) Turbo marketing through time compression. J. Bus. Strategy, September–October, 24–29.

Krachenberg, A. R., Henke, J. W. and Lyons, T. F. (1988) An organizational structure response to competition. In Advances in Systems Research and Cybernetics (ed. G. E. Lasker), International Institute for Advanced Studies in Systems Research and Cybernetics, University of Windsor, Windsor, Ontario, 320–326.

Lawrence, P. and Lorsch, J. (1970) Studies in Organization Design, Richard D. Irwin, Homewood, IL.

Lorenz, A. (1993) BT versus the world. The Sunday Times, 16 May.

Lyons, T. F. Krachenberg, A. R. and Henke, J. W. (1990) Mixed motive marriages: what's next for buyer – supplier relationships? Sloan Manage. Rev., Spring, 29–36.

Macdonald, K. H. (1991) Strategic alignment process. In The Corporation of the 1990s: Information Technology and Organisational Transformation (ed. M. S. Scott Morton), Oxford University Press, New York.

Macdonald, K. H. (1993) Future alignment realities. Unpublished paper.

Maslow, A. H. (1943) A theory of human motivation. Psychology Rev., 50, 370–396.

Maslow, A. H. (1954) Motivation and Personality, Harper, New York.

Mason, R. O. and Mitroff, I. I. (1981) Challenging Strategic Planning Assumptions: Theory, Cases and Techniques, Wiley, New York.

Mayo, E. (1971) Hawthorne and the Western Electric Company. In Organisation Theory (ed. D. S. Pugh), Penguin, Middlesex.

McClelland, D. (1976) Power as the great motivator. Harvard Bus. Rev., May–June, 100–110.

Miles, R. and Snow, C. (1978) Organization Strategy, Structure, and Process, McGraw-Hill, New York.

Miles, R. and Snow, C. (1987) Network organizations: new concepts for new forms. California Manage. Rev., Spring.

Miller, D. (1986) Configuration of strategy and structure: towards a synthesis. Strategic Manage. J., 7, 233–249.

Miller, D. (1987) The genesis of configuration. Acad. Manage. Rev., 12(4), 686–701.

Miller, D. and Mintzberg, H. (1984) The case for configuration. In Organizations: A Quantum View (eds D. Miller and P. H. Friesen), Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Mintzberg, H. (1973) The Nature of Managerial Work, Harper and Row, New York.

Mintzberg, H. (1979) The Structuring of Organizations, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Mintzberg, H. (1991) The effective organization: forces and forms. Sloan Manage. Rev., Winter, 54–67.

Mitroff, I. I. and Linstone, A. (1993) The Unbounded Mind: Breaking the Chains of Traditional Business Thinking, Oxford University Press, New York.

Nakamoto, M. (1992) Plugging into each other's strengths. Financial Times, 27 March.

Ohmae, K. (1989) The global logic of strategic alliances. Harvard Bus. Rev., March–April, 143–154.

Ostrof, F. and Smith, D. (1992) The horizontal organization. The McKinsey Quarterly, 1, 149–168.

Peppard, J. W. and Steward, K. (1993) Managing change in IS/IT implementation. In IT Strategy For Business (ed. J. W. Peppard), Pitman, London, 269–291.

Peters, T. and Waterman, R. H. (1982) In Search of Excellence, Harper and Row, New York.

Porter, M. E. (1980) Competitive Strategy, Free Press, New York.

Porter, M. E. (1985) Competitive Advantage, Free Press, New York.

Poynter, T. A. and White, R. E. (1990) Making the horizontal organisation work. Bus. Quarterly (Canada), Winter, 73–77.

Quinn Mills, D. and Friesen, B. (1992) The learning organization. Europ. Manage. J., 10(2), 146–156.

Reich, R. B. (1987) Entrepreneurship reconsidered: the team as hero. Harvard Bus. Rev., May–June, 77–83.

Rockart, J. F. and Short, J. E. (1989) IT in the 1990s: managing organization interdependencies. Sloan Manage. Rev., 30(2), 7–17.

Schwenk, C. R. (1988) A cognitive perspective on strategic decision-making. J. Manage. Studies, 25(1), 41–55.

Scott, W. G. (1961) Organization theory: an overview and an appraisal. Acad. Manage. Rev., April, 7–26.

Scott Morton, M. S. (ed.) (1991) The Corporation of the 1990s: Information Technology and Organization Transformation, Oxford University Press, New York.

Senge, P. M. (1990a) The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization, Doubleday/Currency, New York.

Senge, P. M. (1990b) The leaders’ new work: building learning organizations. Sloan Manage. Rev., Fall, 7–23.

Senge, P. M. (1991) Team learning. The McKinsey Quarterly, Summer, 82–93.

Slevin, D. P. and Colvin, J. G. (1990) Juggling entrepreneurial style and organization structure: how to get your act together. Sloan Manage. Rev., 31(2), Winter, 43–53.

Smith, A. (1910) The Wealth of Nations, Dent, London.

Snow, C. C., Miles, R. E. and Coleman, H. J. Jr (1992) Managing 21st century network organizations. Organization Dynamics, Winter, 5–20.

Stalk, G. Jr (1988) Time – the next source of competitive advantage. Harvard Bus. Rev., July–August, 41–51.

Stata, R. (1989) Organizational learning – the key to management innovation. Sloan Manage. Rev., Spring, 63–73.

Taylor, F. W. (1911) Scientific Management, Harper, New York.

Thompson, V. (1961) Modern Organizations, Knopf, New York.