7 Approaches to Information

Systems Planning

Experiences in strategic

information systems planning*

Strategic information systems planning (SISP) remains a top concern of many organizations. Accordingly, researchers have investigated SISP practice and proposed both formal methods and principles of good practice. SISP cannot be understood by considering formal methods alone. The processes of planning and the implementation of plans are equally important. However, there have been very few field investigations of these phenomena. This study examines SISP experience in 27 companies and, unusually, relies on interviews not only with IS managers but also with general managers and line managers. By adopting this broader perspective, the investigation reveals companies were using five different SISP approaches: Business-Led, Method-Driven, Administrative, Technological, and Organizational. Each approach has different characteristics and, therefore, a different likelihood of success. The results show that the Organizational Approach appears to be most effective. The taxonomy of the five approaches potentially provides a diagnostic tool for analyzing and evaluating an organization's experience with SISP.

Introduction

For many IS executives, strategic information systems planning (SISP) continues to be a critical issue.1 It is also reportedly the top IS concern of chief executives (Moynihan, 1990). At the same time, it is almost axiomatic that information systems management be based on SISP (Synott and Gruber, 1982). Furthermore, as investment in information technology has been promoted to both support business strategy or create strategic options (Earl, 1988; Henderson and Venkatraman, 1989), an ‘industry’ of SISP has grown as IT manufacturers and management consultants have developed methodologies and techniques. Thus, SISP appears to be a rich and important activity for researchers. So far, researchers have provided surveys of practice and problems, models and frameworks for theory-building, and propositions and methods to put into action.2

The literature recommends that SISP target the following areas:

• aligning investment in IS with business goals

• exploiting IT for competitive advantage

• directing efficient and effective management of IS resources

• developing technology policies and architectures

It has been suggested (Earl, 1989) that the first two areas are concerned with information systems strategy, the third with information management strategy, and the fourth with information technology strategy. In survey-based research to date, it is usually the first two areas that dominate. Indeed, SISP has been defined in this light (Lederer and Sethi, 1988) as ‘the process of deciding the objectives for organizational computing and identifying potential computer applications which the organization should implement’ (p. 445). This definition was used in our investigation of SISP activity in 27 United Kingdom-based companies.

Calls have been made recently for better understanding of strategic planning in general, including SISP, and especially for studies of actual planning behavior in organizations (Boynton and Zmud, 1987; Henderson and Sifonis, 1988). As doubts continue to be raised about the pay-off of IT, it does seem important to examine the reality of generally accepted IS management practices such as SISP. Thus, in this investigation we used field studies to capture the experiences of large companies that had attempted some degree of formal IS planning.3

We were also interested as to whether any particular SISP techniques were more effective than others. This question proved difficult to answer, as discussed below, and is perhaps even irrelevant. Techniques were found to be only one element of SISP, with process and implementation being equally important. Therefore, a more descriptive construct embodying these three elements – the SISP approach – was examined. Five different approaches were identified; the experience of the organizations studied suggests that one approach may be more effective than the others.

Methodology

In 1988–89, a two-stage survey was conducted to discover the intents, outcomes, and experiences of SISP efforts. First, case studies captured the history of six companies previously studied by the author. These retrospective case histories were based on accounts of the IS director and/or IS strategic planner and on internal documentation of these companies. The cases suggested or confirmed questions to ask in the second stage. Undoubtedly, these cases influenced the perspective of the researcher.

In the second stage, 21 different UK companies were investigated through field studies. All were large companies that were among the leaders in the banking, insurance, transport, retailing, electronics, IT, automobile, aerospace, oil, chemical, services, and food and drink industries. Annual revenues averaged £4.5 billion. They were all headquartered in the UK or had significant national or regional IS functions within multi-national companies headquartered elsewhere. Their experience with formal SISP activities ranged from one to 20 years.4 The scope of SISP could be either at the business unit level, the corporate level, or both. The results from this second stage are reported in this chapter.

Within each firm, the author carried out in-depth interviews, typically lasting two to four hours, with three ‘stakeholders’. A total of 63 executives were interviewed. The IS director or IS strategic planner was interviewed first, followed by the CEO or a general manager, and finally a senior line or user manager. Management prescriptions often state that SISP requires a combination or coalition of line managers contributing application ideas or making system requests, general managers setting direction and priorities, and IS professionals suggesting what can be achieved technically. Additionally, interviewing these three stakeholders provides some triangulation, both as a check on the views of the IS function and as a useful, but not perfect, cross-section of corporate memory.

Because the IS director selected the interviewees, there could have been some sample bias. However, parameters were laid down on how to select interviewees, and the responses did not indicate any prior collusion in aligning opinions. Respondents were supposed to be the IS executives most involved with SISP (which may or may not be the CIO), the CEO or general manager most involved in strategic decisions on IS, and a ‘typical’ user line manager who had contributed to SISP activities.

Interviews were conducted using questionnaires to ensure completeness and replicability, but a mix of unstructured, semi-structured, and structured interrogation was employed.5 Typically, a simple question was posed in an open manner (often requiring enlargement to overcome differences in organizational language), and raw responses were recorded. The same question was then asked in a closed manner, requesting quantitative responses using scores, ranking, and Likert-type scales. Particular attention was paid to anecdotes, tangents, and ‘asides’. In this way, it was hoped to collect data sets for both qualitative and quantitative analysis. Interviews focused on intents, outcomes, and experiences of SISP.

It was also attempted to record experiences with particular SISP methodologies and relate their use to success, benefits and problems. However, this aim proved to be inappropriate (because firms often had employed a variety of techniques and procedures over time), and later was jettisoned in favor of recording the variety and richness of planning behavior the respondents recalled. This study is therefore exploratory, with a focus on theory development.6

Interests, methods, and outcomes

Data were collected on the stimuli, aims, benefits, success factors, problems, procedures, and methods of SISP. These data have been statistically examined, but only a minimum of results is presented here as a necessary context to the principal findings of the study.7

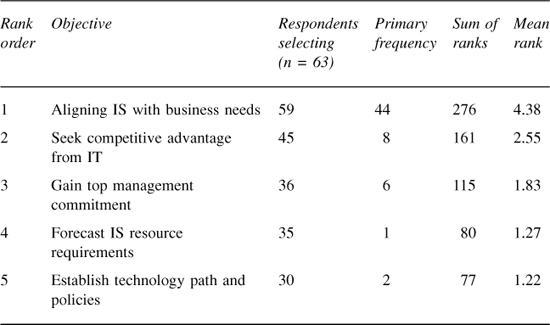

Respondents were asked to state their firms’ current objectives for SISP. The dominant objective was alignment of IS with business needs, with 69.8 percent of respondents ranking it as most important and 93.7 percent ranking it in their top five objectives (Table 7.1). Interview comments reinforced the importance of this objective. The search for competitive advantage applications was ranked second, reflecting the increased strategic awareness of IT in the late 1980s. Gaining top management commitment was third. The only difference among the stakeholders was that IS directors placed top management commitment above the competitive advantage goal, perhaps reflecting a desire for functional sponsorship and a clear mandate.

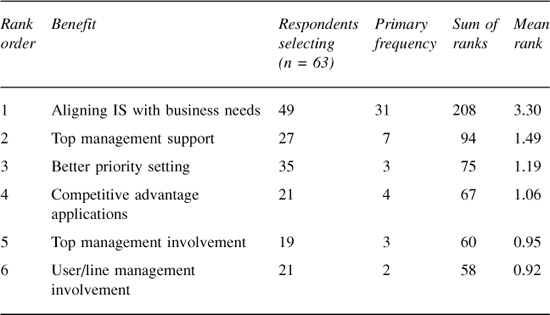

Table 7.1 suggests that companies have more than one objective for SISP; narrative responses usually identified two or three objectives spontaneously. Not surprisingly, the respondents’ views on benefits were similar and also indicated a multidimensional picture (Table 7.2). All respondents were able to select confidently from a structured list. Alignment of IS again stood out, with 49 percent ranking it first and 78 percent ranking it in the top five benefits. Top management support, better priority setting, competitive advantage applications, top management involvement, and user-management involvement were the other prime benefits reported.

Respondents also evaluated their firm's success with SISP. Success measures have been discussed elsewhere (Raghunathan and King, 1988). Most have relied upon satisfaction scores (Galliers, 1987), absence of problems (Lederer and Sethi, 1988), or audit checklists (King, 1988). Respondents were given no criterion of success but were given scale anchors to help them record a score from 1 (low) to 5 (high), as shown in Appendix B.

Ten percent of all respondents claimed their SISP had been ‘highly successful’, 59 percent reported it had been ‘successful but there was room for improvement’, and 69 percent rated SISP as worthwhile or better. Thirty-one percent were dissatisfied with their firm's SISP. There were differences between stakeholders; whereas 76 percent of IS directors gave a score above 3, only 67 percent of general managers and 57 percent of user mangers were as content. Because the mean score by company was 3.73, and the modal company score was 4, the typical experience can be described as worthwhile but in need of some improvement.

A complementary question revealed a somewhat different picture. Interviewees were asked in what ways SISP had been unsuccessful. Sixty-five different types of disappointment were recorded. In such a long list none was dominant. Nevertheless, Table 7.3 summarizes the five most commonly mentioned features contributing to dissatisfaction. We will henceforth refer to these as ‘concerns’.

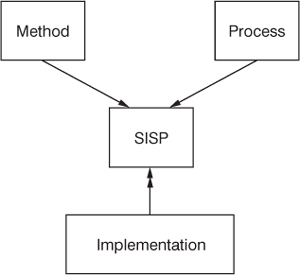

It is apparent that concerns extend beyond technique or methodology, the focus of several researchers, and the horizon of most suppliers. Accordingly we examined the 65 different concerns looking for a pattern. This inductive and subjective clustering produced an interesting classification. The cited concerns could be grouped almost equally into three distinct categories (assuming equal weighting to each concern): method, process, and implementation, as shown in Table 7.4. The full list of concerns is reproduced in Appendix C.

Method concerns centered on the SISP technique, procedure, or methodology employed. Firms commonly had used proprietary methods, such as Method 1, BSP, or Information Engineering, or applied generally available techniques, such as critical success factors or value chain analysis. Others had invented their own methods, often customizing well-known techniques. Among the stated concerns were lack of strategic thinking, excessive internal focus, too much or too little attention to architecture, excessive time and resource requirements, and ineffective resource allocation mechanisms. General managers especially emphasized these concerns, perhaps because they have high expectations but find IS strategy making difficult.

Table 7.3 Unsuccessful features of SISP

Rank order |

Unsuccessful features |

1 |

Resource constraints |

2 |

Not fully implemented |

3 |

Lack of top management acceptance |

4 |

Length of time involved |

5 |

Poor user-IS relationships |

Table 7.4 SISP concerns by stakeholder

Implementation was a common concern. Even where SISP was judged to have been successful, the resultant strategies or plans were not always followed up or fully implemented. Even though clear directions might be set and commitments made to develop new applications, projects often were not initiated and systems development did not proceed. This discovery supports the findings of earlier work (Lederer and Sethi, 1988). Evidence from the interviews suggests that typically resources were not made available, management was hesitant, technological constraints arose, or organizational resistance emerged. Where plans were implemented, other concerns arose, including technical quality, the time and cost involved, or the lack of benefits realized. Implementation concerns were raised most by IS directors, perhaps because they are charged with delivery or because they hoped SISP would provide hitherto elusive strategic direction of their function. Of course, it can be claimed that a strategy that is not implemented or poorly implemented is no strategy at all – a tendency not unknown in business strategy making (Mintzberg, 1987). Indeed, implementation has been proposed as a measure of success in SISP (Lederer and Sethi, 1988).

Process concerns included lack of line management participation, poor IS-user relationships, inadequate user awareness and education, and low management ownership of the philosophy and practice of SISP. Line managers were particularly vocal about the management and enactment of SISP methods and procedures and whether they fit the organizational context.

Figure 7.1 Necessary conditions for successful SISP

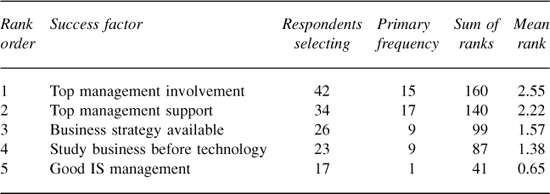

Analysis of the reported concerns therefore suggests that method, process, and implementation are all necessary conditions for successful SISP (Figure 7.1). Indeed, when respondents volunteered success factors for SISP based on their organization's experience, they conveyed this multiple perspective (see Table 7.5). The highest ranked factors of ‘top management involvement’, and ‘top management support’ can be seen as process factors, while ‘business strategy available’ and ‘study the business before technology’ have more to do with method. ‘Good IS management’ partly relates to implementation. Past research has identified similar concerns (Lederer and Mendelow, 1987), and the more prescriptive literature has suggested some of these success factors (Synott and Gruber, 1982). However, the experience of organizations in this study indicates that no single factor is likely to lead to universal success in SISP. Instead, successful SISP is more probable when organizations realize that method, process, and implementation are all necessary issue sets to be managed.

In particular, consultants, managers, and researchers would seem well advised to look beyond method alone in practising SISP. Furthermore, researchers cannot assume that SISP requires selection and use of just one method or one special planning exercise. Typically, it seems that firms use several methods over time. An average of 2.3 methods (both proprietary and in-house) had been employed by the 21 companies studied. Nine of them had tried three or more. Retrospectively isolating and identifying the effect of a method therefore becomes difficult for researchers. It may also be misleading because, as discovered in these interviews, firms engage in a variety of strategic planning activities and behavior. This became apparent when respondents were asked the open-ended question, ‘Please summarize the approach you have adopted in developing your IS strategy (or identifying which IT applications to develop in the long run)’. In reply they usually recounted a rich history of initiatives, events, crises, techniques, organizational changes, successes, and failures all interwoven in a context of how IS resources had been managed.

Table 7.5 Success factors in SISP

Prompted both by the list of concerns and narrative histories of planning-related events, the focus of this study therefore shifted. The object of analysis became the SISP approach. This we viewed as the interaction of method, process, and implementation, as well as the variety of activities and behaviors upon which the respondents had reflected. The accounts of interviewees, the ‘untutored’ responses to the semi-structured questions, the documents supplied, and the ‘asides’ followed up by the interviewer all produced descriptive data on each company's approach. Once the salient features of SISP were compared across the 21 companies, five distinct approaches were identified. These were then used retrospectively to classify the experiences of the six case study firms.

SISP approaches

An approach is not a technique per se. Nor is it necessarily an explicit study or formal, codified routine so often implied in past accounts and studies of SISP. As in most forms of business planning, it cannot often be captured by one event, a single procedure, or a particular technique. An approach may comprise a mix of procedures, techniques, user-IS interactions, special analyses, and random discoveries. There are likely to be some formal activities and some informal behavior. Sometimes IS planning is a special endeavor and sometimes it is part of business planning at large. However, when members of the organization describe how decisions on IS strategy are initiated and made, a coherent picture is gradually painted where the underpinning philosophy, emphasis, and influences stand out. These are the principal distinguishing features of an approach. The elements of an approach can be seen as the nature and place of method, the attention to and style of process, and the focus on and probability of implementation.

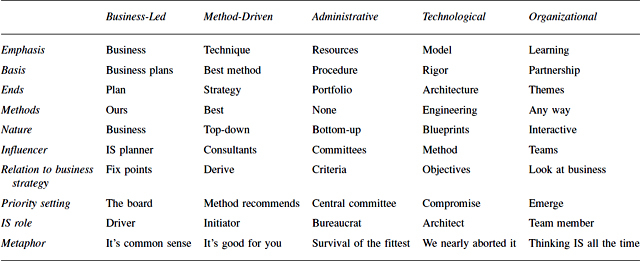

The five approaches are labelled as Business-Led, Method-Driven, Administrative, Technological, and Organizational. They are delineated as ideal types in Table 7.6. Several distinctors are apparent in each approach. Each represents a particular philosophy (either explicit or implicit), displays its own dynamics, and has different strengths and weaknesses. Whereas some factors for success are suggested by each approach, not all approaches seem to be equally effective.

Business-led approach

The Business-led Approach was adopted by four companies and two of the case study firms. The underpinning ‘assumption’ of this approach is that current business direction or plans are the only basis upon which IS plans can be built and that, therefore, business planning should drive SISP. The emphasis is on the business leading IS and not the other way around. Business plans or strategies are analyzed to identify where information systems are most required. Often this linkage is an annual endeavor and is the responsibility of the IS director or IS strategic planner (or team). The IS strategic plan is later presented to the board for questioning, approval, and priority-setting.

General managers see this approach as simple, ‘business-like’, and a matter of common sense. IS executives often see this form of SISP as their most critical task and welcome the long overdue mandate from senior management. However, they soon discover that business strategies are neither clear nor detailed enough to specify IS needs. Thus, interpretation and further analysis become necessary. Documents have to be studied, managers interviewed, meetings convened, working papers written, and tentative proposals on the IS implications of business plans put forward. ‘Home-spun’ procedures are developed on a trial and error basis to discover and propose the IT implications of business plans. It may be especially difficult to promote the notion that IT itself may offer some new strategic options. The IS planners often feel that they have to ‘take the lead’ to make any progress or indeed to engage the business in the exercise. They also discover that some top executives may be more forceful in their views and expectations than others.

Users and line managers are likely to be involved very little. The emphasis on top-level input and business plans reduces the potential contribution of users and the visibility of local requirements. Users, perceiving SISP as remote, complain of inadequate involvement. Because the IS strategy becomes the product of the IS function, user support is not guaranteed. Top management, having substantially delegated SISP to the specialists, may be unsure of the recommendations and be hesitant to commit resources, thus impairing implementation.

Nevertheless, some advantages can accrue. Information systems are seen as a strategic resource, and the IS function receives greater legitimacy. Important strategic thrusts that require IT support can be identified, and if the business strategy is clearly and fully presented, the IS strategy can be well-aligned. Indeed, in one of the prior case study companies that adopted this approach, a clear business plan for survival led to IT applications that were admired by many industry watchers. However, despite this achievement, the IS function is still perceived by all three sets of stakeholders as poorly integrated into the business as a whole.

Method-driven approach

The Method-Driven Approach was present in two companies and two of the case study firms. Adherents of this approach appear to assume that SISP is enhanced by, or depends on, use of a formal technique or method. The IS director may believe that management will not think about IS needs and opportunities without the use of a formal method or the intervention of consultants. Indeed, recognition or anticipation of some of the frustrations typical of the Business-Led Approach may prompt the desire for method. However, any method will not do. There is typically a search for the ‘best method’, or at least one better than the last method adopted.

Once again, business strategies may be found to be deficient for the purpose of SISP. The introduction of a formal method rarely provides a remedy, however, because it is unlikely to be a strong enough business strategy technique. Also, the method's practitioners are unlikely to be skilled or credible at such work. Furthermore, as formal methods are usually sponsored by the IS department, they may fail to win the support or involvement of the business at large. Thus, a second or third method may be attempted while the IS department tries to elicit or verify the business strategy and to encourage a wider set of stakeholders to participate. Often, a vendor or consultant plays a significant role. As the challenges unfold, stakeholders determine the ‘best’ method, often as a result of the qualities of the consultants as much as the techniques themselves. The consultants often become the drivers of the SISP exercise and therefore have substantial influence on the recommendations.

Users may judge Method-Driven exercises as ‘unreal’ and ‘high level’ and as having excluded the managers who matter, namely themselves. General managers can see the studies as ‘business strategy making in disguise’ and thus become somewhat resistant and not easily persuaded of the priorities or options suggested by the application of the method. IS strategic plans may then lose their credibility and never be fully initiated. The exercises and recommendations may be forgotten. Often they are labelled the ‘xyz’ strategy, where ‘xyz’ is the name of the consulting firm employed; in other words, these strategies are rarely ‘owned’ by the business.

Formal methods do not always fail completely. Although a succession of methods achieved little in the companies studied, managers judged that each method had been good in some unanticipated way for the business or the IS department.8 For example, in one firm it showed the need for business strategies, and in another it informed IS management about business imperatives. In the former firm, IS directors were heard to say the experience had been ‘good for the company, showing up the gaps in strategic thinking!’ Nevertheless, formal strategy studies could leave behind embryonic strategic thrusts, ideas waiting for the right time, or new thinking that could be exploited or built upon later in unforeseen ways.

Administrative approach

The Administrative Approach was found in five companies. The emphasis here is on resource planning. The wider management planning and control procedures were expected to achieve the aims of SISP through formal procedures for allocating IS resources. Typically, IS development proposals were submitted by business units or departments to committees who examined project viability, common system possibilities, and resource consequences. In some cases, resource planners did the staff work as proposals ascended the annual hierarchical approval procedure. The Administrative Approach was the parallel of, or could be attached to, the firm's normal financial planning or capital budgeting routine. The outcome of the approach was a one-year or multi-year development portfolio of approved projects. Typically no application is developed until it is on the plan. A planning investment or steering committee makes all decisions and agrees on any changes.

Respondents identified significant down sides to the Administrative Approach. It was seen as not strategic, as being ‘bottom-up’ rather than ‘topdown’. Ideas for radical change were not identified, strategic thinking was absent, inertia and ‘business as usual’ dominated, and enterprise-level applications remained in the background. More emotional were the claims about conflicts, dramas, and game playing – all perhaps inevitable in an essentially resource allocation procedure. The emphasis on resource planning sometimes led to a resource-constrained outcome. For example, spending limits were often applied, and boards and CEOs were accused of applying cuts to the IS budget, assuming that in doing so no damage was being done to the business as a whole.

Some benefits of this approach were identified. Everybody knew about the procedure; it was visible, and all users and units had the opportunity to submit proposals. Indeed, an SISP procedure and timetable for SISP were commonly published as part of the company policy and procedures manual. Users, who were encouraged to make application development requests, did produce some ideas for building competitive advantage. Also, it seemed that radical, transformational IT applications could arise in these companies despite the apparently bottom-up, cautious procedure. The most radical applications emerged when the CEO or finance director broke the administrative rules and informally proposed and sanctioned an IS investment.

By emphasizing viability, project approval, and resource planning, the administrative approach produced application development portfolios that were eventually implemented. Not only financial criteria guided these choices. New strategic guidelines, such as customer service or quality improvement, were also influential. Finally, the Administrative Approach often fitted the planning and control style of the company. IS was managed in congruence with other activities, which permitted complemetary resources to be allocated in parallel. Indeed, unless the IS function complied with procedures, no resources were forthcoming.

Technological approach

The Technological Approach was adopted by four companies and two of the case study firms. This approach is based on the assumption that an information systems-oriented model of the business is a necessary outcome of SISP and, therefore, that analytical modelling methods are appropriate. This approach is different from the Method-Driven Approach in two principal characteristics. First, the end product is a business model (or series of models). Second, a formal method is applied based on mapping the activities, processes, and data flows of the business. The emphasis is on deriving architectures or blueprints for IT and IS, and often Information Engineering terminology is used. Architectures for data, computing, communications, and applications might be produced, and computer-aided software engineering (CASE) might be among the tools employed. A proprietary technology-oriented method might be used or adapted in-house. Both IS directors and general mangers tend to emphasize the objectives of rigorous analysis and of building a robust infrastructure.

This approach is demanding in terms of both effort and resource requirements. These also tend to be high-profile activities. Stakeholders commented on the length of time involved in the analysis and/or the implementation. User managers reacted negatively to the complexity of the analysis and the outputs and reported a tendency for technical dependencies to displace business priorities. In one case, management was unsure of the validity and meaning of the blueprints generated and could not determine what proposals mattered most. A second study of the same type, but using a different technological method, was commissioned. This produced a different but equally unconvincing set of blueprints.

These characteristics could lead to declining top management support or even user rebellion. In one firm, the users called for an enterprise modelling exercise to be aborted. In one of the case study firms, development of the blueprint applications was axed by top management three and a half years after initiation. In another, two generations of IS management departed after organizational conflict concerning the validity of the technological model proposed.

Some success was claimed for the Technological Approach. Benefits were salvaged by factoring down the approach into smaller exercises. In one case this produced a database definition, and in another it led to an IT architecture for the finance function. Some IS directors claimed these outcomes were valuable in building better IT infrastructures.

Organizational approach

The Organizational Approach was used in six companies and one of the case study firms. The underpinning assumption here is quite different. It is that SISP is not a special or neat and tidy endeavor but is based on IS decisions being made through continuous integration between the IS function and the organization. The way IT applications are identified and selected is described in much more multi-dimensional and subtle language. The approach is not without method, but methods are employed as required and to fit a particular purpose. For example, value analysis may be used, workshops arranged, business investigation projects set up, and vendor visits organized. The emphasis, however, is on process, especially management understanding and involvement. For some of these companies, a major SISP method had been applied in the past, but in retrospect it was seen to have been as much a process enabler as an analytical investigation. Executive teamwork and an understanding of how IT might contribute to the business were often left behind by the method rather than specific recommendations for IS investment. Organizational learning was important and evident in at least three ways.

First, IS development concentrated on only one or two themes growing in scope over several years as the organization began to appreciate the potential benefits. Examples of such themes included a food company concentrating on providing high service levels to customers, an insurance company conentrating on low-cost administration, and a chemical company concentrating on product development performance. Second, special studies were important. Often multidisciplinary senior executive project teams or full-time task forces were assigned to tackle a business problem from which a major IS initiative would later emerge. The presence of an IS executive in the multidisciplinary team was felt to be important to the emergence of a strategic theme because this person could suggest why, where, and how IT could help. Teamwork was the principal influence in IS strategy making. Third, there was a focus on implementation. Themes were broken down into identifiable and frequent deliverables. Conversely, occasional project cost and time overruns were acceptable if they allowed evolving ideas to be incorporated. In some ways, IS strategies were discovered through implementation. These three learning characteristics can be seen collectively as a preference for incremental strategy making.

The approach is therefore organizational because:

1 Collective learning across the organization is evident.

2 Organizational devices or instruments (teams, task forces, workshops, etc.) are used to tackle business problems or pursue initiatives.

3 The IS function works in close partnership with the rest of the organization, especially through having IS managers on management teams or placing IS executives on task forces.

4 Devolution of some IS capability is common, not only to divisions, but also to functions, factories, and departments.

5 In some companies SISP is neither special nor abnormal. It is part of the normal business planning of the organization.

6 IS strategies often emerge from ongoing organizational activities, such as trial and error changes to business practices, continuous and incremental enhancement of existing applications, and occasional system initiatives and experiments within the business.

In one of the companies, planning was ‘counter-cultural’. Nevertheless, in the character described above, planning still happened. In another company there were no IS plans, just business plans. In another, IS was enjoying a year or more of low profile until the company discovered the next theme. In most of these firms, IS decisions were being made all the time and at any time.

Respondents reported some disadvantages of this approach. Some IS directors worried about how the next theme would be generated. Also, because the approach is somewhat fuzzy or soft, they were not always confident that it could be transplanted to another part of the business. Indeed, a new CEO, management team, or management style could erode the process without the effect being apparent for some time. One IS director believed the incrementalism of the Organizational Approach led to creation of inferior infrastructures.

The five approaches appear to be different in scope, character, and outcome. Table 7.7 differentiates them using the three characteristics that seem to help other organizations position themselves. Also, slogans are offered to capture the essence of each approach. Strengths and weaknesses of each approach are contained in Table 7.8.

It is also possible to indicate the apparent differences of each approach in terms of the three factors suggested in Figure 7.1 as necessary for success: method, process, and implementation. Table 7.9 attempts a summary.

In the Business-Led Approach, method scores low because no formal technique is used; process is rated low because the exercise is commonly IS dominated; but implementation is medium because the boards tend to at least approve some projects. In the Method-Driven Approach, method is high by definition, but process is largely ignored and implementation barely or rarely initiated. In the Administrative Approach, only a procedure exists as method. However, its dependence on user inputs suggests a medium rating on process. Because of its resource allocation emphasis, approved projects are generally implemented. The Technological Approach is generally method-intensive and insensitive to process. It can, however, lead to some specific implementation of an infrastructure. The Organizational Approach uses any method or devices that fit the need; it explicitly invests in process and emphasizes implementation.

Preliminary evaluations

The five approaches were identified by comparing the events, experiences, and lessons described by the interviewees. As the investigation proved to be exploratory, the classification of approaches is descriptive and was derived by inductive interpretation of organizational experiences. Table 7.6, therefore, should be seen as an ideal model that caricatures the approaches in order to aid theory development. One way of ‘validating’ the model is to compare it with prior research in both IS and general management to assess whether the approaches ‘ring true’.

Table 7.7 Five approaches summarized

Table 7.8 Strengths and weaknesses of SISP approaches

Table 7.9 SISP approaches vs. three conditions for success

Related theories

Difficulties encountered in the Business-Led Approach have been noted by others. The availability of formal business strategies for SISP cannot be assumed (Bowman et al., 1983; Lederer and Mendelow, 1986). Nor can we assume that business strategies are communicated to the organization at large, are clear and stable, or are valuable in identifying IS needs (Earl, 1989; Lederer and Mendelow, 1989). Indeed, the quality of the process of business planning itself may often be suspect (Lederer and Sethi, 1988). In other words, while the Business-Led Approach may be especially appealing to general managers, the challenges are likely to be significant.

There is considerable literature on the top-down, more business-strategyoriented SISP methods implied by the Method-Driven Approach, but most of it is conjectural or normative. Vendors can be very persuasive about the need for a methodology that explicitly connects IS to business thinking (Bowman et al., 1983). Other researchers have argued that sometimes the business strategy must be explicated first (King, 1978; Lederer and Mendelow, 1987). This was a belief of the IS directors in the Method-Driven companies, but one general manager complained that this was ‘business strategy making in disguise’. The Administrative Approach reflects the prescriptions and practices of bureaucratic models of planning and control. We must turn to the general management literature for insights into this approach. Quinn (1977) has pointed out the strategy-making limitations of bottom-up planning procedures. He argues that big change rarely originates in this way and that, furthermore, annual planning processes rarely foster innovation. Both the political behavior stimulated by hierarchical resource allocation mechanisms and the business-as-usual inertia of budgetary planning have been well-documented elsewhere (Bowers, 1970; Danziger, 1978).

The Technological Approach may be the extreme case of how the IT industry and its professionals tend to apply computer science thinking to planning. The deficiencies of these methods have been noted in accounts of the more extensive IS planning methods and, in particular, of Information Engineering techniques. For instance, managers are often unhappy with the time and cost involved (Goodhue et al., 1988; Moynihan, 1990). Others note that IS priorities are by definition dependent on the sequence required for architecture building (Hackathorn and Karimi, 1988; Inmon, 1986). The voluminous data generated by this class of method has also been reported (Bowman et al., 1983; Inmon, 1986).

The Organizational Approach does not fit easily with the technical and prescriptive IS literature, but similar patterns have been observed by the more behavioral studies of business strategy making. It is now known that organizations rarely use the rational-analytical approaches touted in the planning literature when they make significant changes in strategy (Quinn, 1978). Rather, strategies often evolve from fragmented, incremental, and largely intuitive processes. Quinn believed this was the quite natural, proper way to cope with the unknowable – proceeding flexibly and experimentally from broad concepts to specific commitments.

Mintzberg's (1983) view of strategy making is similar. It emphasizes small project-based multiskilled teams, cross-functional liaison devices, and selective decentralization. Indeed, Mintzberg's view succinctly summarizes the Organizational Approach. He argues that often strategy is formed, rather than formulated, as actions converge into patterns and as analysis and implementation merge into a fluid process of learning. Furthermore, Mintzberg sees strategy making in reality as a mixture of the formal and informal and the analytical and emergent. Top managers, he argues, should create a context in which strategic thinking and discovery mingle, and then they should intervene where necessary to shape and support new ways forward.

In IS research, Henderson (1989) may have implicitly argued for the Organizational Approach when he called for an iterative, ongoing IS planning process to build and sustain partnership. He suggested partnership mechanisms such as task forces, cross-functional teams, multi-tiered and cross-functional networks, and collaborative planning without planners. Henderson and Sifonis (1988) identify the importance of learning in SISP, and de Geus (1988) sees all planning as learning and teamwork as central to organizational learning. Goodhue et al. (1988) and Moynihan (1990) argue that SISP needs to deliver good enough applications rather than optimal models. These propositions could be seen as recognition of the need to learn by doing and to deliver benefits. There is therefore a literature to support the Organizational Approach.

Data assessment

The field data itself can be used to assess the suggested taxonomy of approaches. Questions that arise are: do the approaches actually exist, and is it possible to clearly differentiate between them? Analysis of variance tests on reported success scores indicated that differences between approaches are significant, but differences between stakeholder sets are not.9 This is one indication that approach is a distinct and meaningful way of analyzing SISP in action.

A second obvious question is whether any approaches are more effective than others. It is perhaps premature to ask this question of a taxonomy suggested by the data. Caution would advise further validation of the framework first, followed by carefully designed measurement tests. However, this study provides an opportunity for an early, if tentative, evaluation of this sort.

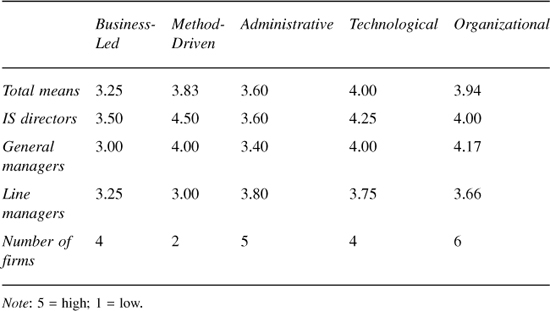

For example, as shown in Table 7.10, success scores can be correlated with SISP approach. Overall mean scores are shown, as well as scores for each stakeholder set. No approach differed widely from the mean score (3.73) across all companies. However, the most intensive approach in terms of technique (Technological) earned the highest score, perhaps because it represents what respondents thought an IS planning methodology should look like. Conversely, the Business-Led Approach, which lacks formal methodologies, earned the lowest scores. There are, of course, legitimate doubts about the meaning or reliability of these success scores because respondents were so keen to discuss the unsuccessful features.

Table 7.10 Mean success scores by approach

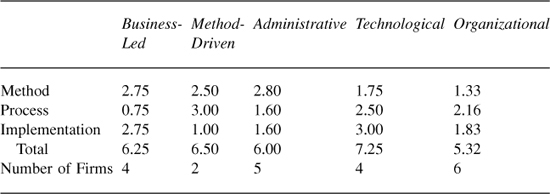

Accordingly, another available measure is to analyze the frequency of concerns reported by firm, assuming each carries equal weight. Table 7.11 breaks out these data by method, process, and implementation concerns. The Organizational Approach has the least concerns attributed to it in total. The Business-Led Approach was characterized by high dissatisfaction with method and implementation. The Method-Driven Approach was perceived to be unsuccessful on process and, ironically, on method, while opinion was less harsh on implementation, perhaps because implementation experience itself is low. The Administrative Approach, as might be predicted, is not well-regarded on method. These data are not widely divergent from the qualitative analysis in Table 7.9.

Table 7.11 SISP concerns per firm

Another measure is the potential of each approach for generating competitive advantage applications. Respondents were asked to identify and describe such applications and trace their histories. No attempt was made by the researcher to check the competitive advantage claimed or to assess whether the applications deserved the label. Although only 14 percent of all such applications were reported to have been generated by a formal SISP study, it is interesting to compare achievement rates of the firms in each approach (Table 7.12). Method-Driven and Technological Approaches do not appear promising. Little is ever initiated in the Method-Driven Approach, while competitiveness is rarely the focus of the Technological Approach. The Administrative Approach appears to be more conducive, perhaps because user ideas receive a hearing. Forty-two percent of competitive advantage applications discovered in all the firms originated from user requests. In the Business-Led Approach, some obviously necessary applications are actioned. In the Organizational Approach, most of the themes pursued were perceived to have produced a competitive advantage.

Table 7.12 Competitive advantage propensity

Approach |

Competitive advantage application frequency |

Business-Led |

4.0 applications per firm |

Method-Driven |

1.5 applications per firm |

Administrative |

3.6 applications per firm |

Technological |

2.5 applications per firm |

Organizational |

4.8 applications per firm |

These three qualitative measures can be combined to produce a multidimensional score. Other scholars have suggested that a number of performance measures are required to measure the effectiveness of SISP (Raghunathan and King, 1988). Table 7.13 ranks each approach according to the three measures discussed above (where 1 = top and 5 = bottom). In summing the ranks, the Organizational Approach appears to be substantially superior. Furthermore, all the other approaches score relatively low on this basis.

Table 7.13 Multidimensional ranking of SISP approaches

Thus, both qualitative and quantitative evidence suggest that the Organizational Approach is likely to be the best SISP approach to use and, thus, a candidate for further study. The Organizational Approach is perhaps the least formal and structured. It also differs significantly from conventional prescriptions in the literature and practice.

Implications for research

Many prior studies of SISP have been based on the views of IS managers alone. A novel aspect of this study was that the attitudes and experiences of general managers and users were also examined. In reporting back the results to the respondents in the survey companies, an interesting reaction occurred. The stakeholders were asked to select which approach best described their experience with SISP. If only IS professionals were present, their conclusions often differed from the final interpretative results. However, when all three stakeholders were present, a lively discussion ensued and, eventually, unprompted, the group's views moved toward an interpretation consistent with both the data presented and the approach attributed to the firm. This is another soft form of validation. More important, it indicates that approach is not only a multi-dimensional construct but also captures a multi-stakeholder perspective. This suggests that studies of IS management practice can be enriched if they look beyond the boundaries of the IS department.

Another characteristic of prior work on SISP is the assumption that formal methods are used and in principle are appropriate (Lederer and Sethi, 1988; 1991). A systematic linkage to the organization's business planning procedures is also commonly assumed (Boynton and Zmud, 1987; Karimi, 1988). The findings of this study suggest that these may be false assumptions and that, besides studying formal methods, researchers should continue to investigate matters of process while also paying attention to implementation. Indeed, in the field of business strategy, it was studies of the process of strategy making that led to the ‘alternative’ theories of the strategic management of the firm developed by Quinn (1978) and Mintzberg (1987).

The Organizational Approach to SISP suggested by this study might also be seen as an ‘alternative’ school of thought. This particular approach, therefore, should be investigated further to understand it in more detail, to assess its effectiveness more rigorously, and to discover how to make it work.

Finally, additional studies are required to further validate and then perhaps develop these findings. Some of the parameters suggested here to distinguish the approaches could be taken as variables and investigated on larger samples to verify the classification. Researchers could also explore whether different approaches fit, or work better in, different contexts. Candidate situational factors include information intensity of the sector, environmental uncertainty, the organization's management planning and control style, and the maturity of the organization's IS management experience.

Implications for practice

For practitioners, this study provides two general lessons. First, SISP requires a holistic or interdependent view. Methods may be necessary, but they could fail if the process factors receive no attention. It is also important to explicitly and positively incorporate implementation plans and decisions in the strategic planning cycle.

Second, successful SISP seems to require users and line managers working in partnership with the IS function. This may not only generate relevant application ideas, but it will tend to create ownership of both process and outcomes. The taxonomy of SISP approaches emerging from this study might be interpreted for practice in at least four different ways. First, it can be used as a diagnostic tool to position a firm's current SISP efforts. The strengths and weaknesses identified in the research then could suggest how the current approach could be improved. We have found that frameworks used in this way are likely to be more helpful if users and general managers as well as IS professionals join together in the diagnosis.

Second, the taxonomy can be used to design a situation-specific (customized) approach on a ‘mix-and-match’ basis. It may be possible to design a potentially more effective hybrid. The author is aware of one company experimenting at building a combination of the Organizational and Technological Approaches. One of the study companies that had adopted the Organizational Approach to derive its IS strategy also sought some of the espoused benefits of the Technological Approach by continuously formulating a shadow blueprint for IT architecture. This may be one way of reconciling the apparent contradictions of the Organizational and Technological Approaches.

Third, based on our current understanding it appears that the Organizational Approach is more effective than others. Therefore, firms might seriously consider adopting it. This could involve setting up mechanisms and responsibility structures to encourage IS-user partnerships, devolving IS planning and development capability, ensuring IS managers are members of all permanent and ad hoc teams, recognizing IS strategic thinking as a continuous and periodic activity, identifying and pursuing business themes, and accepting ‘good enough’ solutions and building on them. Above all, firms might encourage any mechanisms that promote organizational learning about the scope of IT.

Another interpretation is that the Organizational Approach describes how most IS strategies actually are developed, despite the more formal and rational endeavors of IS managers or management at large. The reality may be a continuous interaction of formal methods and informal behavior and of intended and unintended strategies. If so, SISP in practice should be eclectic, selecting and trying methods and process initiatives to fit the needs of the time. One consequence of this view might be recognition and acceptance that planning need not always generate plans and that plans may arise without a formal planning process.

Finally, it can be revealing for an organization to recall the period when IS appeared to be contributing most effectively to the business and to describe the SISP approach in use (whether by design or not) at the time. This may then indicate which approach is most likely to succeed for that organization. Often when a particularly successful IS project is recalled, its history is seen to resemble the Organizational Approach.

Conclusions

This study evolved into a broad, behavioral exploration of experiences in large organizations. The breadth of perspective led to the proposition that SISP is more than method or technique alone. In addition, process issues and the question of implementation appear to be important. These interdependent elements combine to form an approach. Five different SISP approaches were identified, and one, the Organizational Approach, appears superior.

For practitioners, the taxonomy of SISP approaches provides a diagnostic tool to use in evaluating the effectiveness of their SISP efforts and in learning from their own experiences. Whether rethinking SISP or introducing it for the first time, firms may want to consider adopting the Organizational Approach. Two reasons led to this recommendation. First, among the companies explored, it seemed the most effective approach. Second, this study casts doubt on several of the by now ‘traditional’ SISP practices that have been advocated and developed in recent years.

The ‘approach’ construct presented in this chapter, the taxonomy of SISP approaches derived, and the indication that the least formal and least analytical approach seems to be most effective all offer new directions for SISP research and theory development.

Notes

1 See, for example, surveys by Dickson et al. (1984), Hartog and Herbert (1986), Brancheau and Wetherbe (1987), and Niederman et al. (1991).

2 Propositions and methods include Zani's (1970) early top-down proposal, King's (1978) more sophisticated linkage of the organization's IS strategy set to the business strategy set, and focused techniques such as critical success factors (Bullen and Rockart, 1981) and value chain analysis (Porter and Millar, 1985). These are supplemented by product literature such as Andersen's (1983) Method 1 or IBM's (1975) Business System Planning. The models and frameworks for developing a theory of SISP include Boynton and Zmud (1987), Henderson and Sifonis (1988), and Henderson and Venkatraman (1989). Empirical works include a survey of practice by Galliers (1987), analysis of methods by Sullivan (1985), investigation of problems by Lederer and Sethi (1988), assessment of success by Lederer and Mendelow (1987) and Raghunathan and King (1988), and evaluation of particular techniques such as strategic data planning (Goodhue et al., 1992).

3 Prior work has tended to use mail questionnaires targeted at IS executives. However, researchers have called for broader studies and for surveys of the experiences and perspectives of top managers, corporate planners, and users (Lederer and Mendelow, 1989; Lederer and Sethi, 1988; Raghunathan and King, 1988).

4 Characteristics of the sample companies are summarized in Appendix A.

5 Extracts from the interview questionnaires are shown in Appendix B.

6 This exploration through field studies was in the spirit of ‘grounded theory’ (Glaser and Strauss, 1967).

7 Fuller descriptive statistics can be seen in an early research report (Earl, 1990).

8 Methods employed included proprietary, generic, and customized techniques.

9 Differences between approaches are significant at the 10 percent level (f = 0.056). Differences between stakeholder sets are not significant (f = 0.126). No interaction was discovered between the two classifications.

References

Arthur Andersen & Co. (1983) Method/1: Information Systems Methodology: An Introduction, The Company, Chicago, IL.

Bowers, J. L. (1970) Managing the Resource Allocation Process: A Study of Corporate Planning and Investment, Division of Research, Graduate School of Business Administration, Harvard University, Boston, MA.

Bowman B., Davis, G. and Wetherbe, J. (1983) Three stage model of MIS planning. Information and Management, 6(1), August, 11–25.

Boynton, A. C. and Zmud, R. W. (1987) Information technology planning in the 1990’s: directions for practice and research. MIS Quarterly 11(1), March, 59–71.

Brancheau, J. C. and Wetherbe, J. C. (1987) Key issues in information systems management. MIS Quarterly, 11(1), March, 23–45.

Bullen, C. V. and Rockart, J. F. (1981) A primer on critical success factors. CISR Working Paper No. 69, Center for Information Systems Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, June.

Danziger, J. N. (1978) Making Budgets: Public Resource Allocation, Sage Publications, Beverly Hills, CA.

de Geus, A. P. (1988) Planning as learning. Harvard Business Review, 66(2), March-April, 70–74.

Dickson, G. W., Leitheiser, R. L., Wetherbe, J. C. and Nechis, M. (1984) Key information systems issues for the 1980’s. MIS Quarterly, 10(3), September, 135–159.

Earl, M. J. (ed.) (1988) Information Management: The Strategic Dimension, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Earl, M. J. (1989) Management Strategies for Information Technology, Prentice Hall, London.

Earl, M. J. (1990) Strategic information systems planning in UK Companies early results of a field study. Oxford Institute of Information Management Research and Discussion Paper 90/1, Templeton College, Oxford.

Galliers, R. D. (1987) Information Systems Planning in Britain and Australia in the Mid-1980’s: Key Success Factors, unpublished doctoral dissertation, London School of Economics, University of London.

Glaser, B. G. and Strauss, A. L. (1967) The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research, Aldine Publishing Company, Chicago, IL.

Goodhue, D. L., Quillard. J. A. and Rockart, J. F. (1988) Managing the data resource: a contingency perspective. MIS Quarterly, 12(3), September, 373–391.

Goodhue, D. L., Kirsch, L. J., Quillard, J. A. and Wybo, M. D. (1992) Strategic data planning: lessons from the field. MIS Quarterly, 16(1), March, 11–34.

Hackathorn, R. D. and Karimi, J. (1988) A framework for comparing information engineering methods. MIS Quarterly, 12(2), June, 203–220.

Hartog, C. and Herbert, M. (1986) 1985 opinion survey of MIS managers: key issues. MIS Quarterly, 10(4), December, 351–361.

Henderson, J. C. (1989) Building and sustaining partnership between line and I/S managers. CISR Working Paper No. 195. Center for Information Systems Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, September.

Henderson, J. C. and Sifonis, J. G. (1988) The value of strategic IS planning: understanding consistency, validity, and IS markets. MIS Quarterly, 12(2), June, 187–200.

Henderson, J. C. and Venkatraman, N. (1989) Strategic alignment: a framework for strategic information technology management. CISR Working Paper No. 190, Center for Information Systems Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, August.

IBM Corporation (1975) Business Systems Planning – Information Systems Planning Guide, Publication #GE20–0527–4, White Plains, NY.

Inmon, W. H. (1986) Information Systems Architecture, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Karimi, J. (1988) Strategic planning for information systems: requirements and information engineering methods. Journal of Management Information Systems, 4(4), Spring, 5–24.

King, W. R. (1978) Strategic planning for management information systems. MIS Quarterly, 2(1), March, 22–37.

King, W. R. (1988) How effective is your information systems planning? Long Range Planning, 1(1), October, 7–12.

Lederer, A. L. and Mendelow, A. L. (1986) Issues in information systems planning. Information and Management, 10(5), May, 245–254.

Lederer, A. L. and Mendelow, A. L. (1987) Information resource planning: overcoming difficulties in identifying top management's objectives. MIS Quarterly, 11(3), September, 389–399.

Lederer, A. L. and Mendelow, A. L. (1989) Co-ordination of information systems plans with business plans. Journal of Management Information Systems, 6(2), Fall, 5–19.

Lederer, A. L. and Sethi, V. (1988) The implementation of strategic information systems planning methodologies. MIS Quarterly, 12(3), September, 445–461.

Lederer, A. L. and Sethi, V. (1991) Critical dimensions of strategic information systems planning. Decision Sciences, 22(1), Winter, 104–119.

Mintzberg, H. (1983) Structure in Fives: Designing Effective Organizations, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Mintzberg, H. (1987) Crafting strategy. Harvard Business Review, 66(4), July-August, 66–75.

Moynihan, T. (1990) What chief executives and senior managers want from their IT departments. MIS Quarterly, 14(1), March, 15–26.

Niederman, F., Brancheau, J. C. and Wetherbe, J. C. (1991) Information systems management issues for the 1990s. MIS Quarterly, 15(4), December, 475–500.

Porter, M. E. and Millar, V. E. (1985) How information gives you competitive advantage. Harvard Business Review, 66(4), July-August, 149–160.

Quinn, J. B. (1977) Strategic goals: plans and politics. Sloan Management Review, 19(1), Fall, 21–37.

Quinn, J. B. (1978) Strategic change: logical incrementalism. Sloan Management Review, 20(1), Fall, 7–21.

Raghunathan, T. S. and King. W. R. (1988) The impact of information systems planning on the organization. OMEGA, 16(2), 85–93.

Sullivan, C. H., Jr. (1985) Systems planning in the information age. Sloan Management Review, 26(2), Winter, 3–11.

Synott, W. R. and Gruber, W. H. (1982) Information Resource Management: Opportunities and Strategies for the 1980’s, J. Wiley and Sons, New York.

Zani, W. M. (1970) Blueprint for MIS. Harvard Business Review, 48(6), November–December, 95–100.

Appendix A: Field study companies

Descriptive statistics for field study companies

Company |

Annual revenue (£B) |

Annual IS expenditure (£M) |

Years of SISP experience |

1 Banking |

1.7* |

450 |

4 |

2 Banking |

1.9* |

275 |

2 |

3 Retailing |

4.2 |

80 |

4 |

4 Retailing |

0.56 |

8 |

4 |

5 Insurance |

2.8† |

30 |

11 |

6 Insurance |

0.9† |

15 |

15 |

7 Travel |

0.75 |

8 |

4 |

8 Electronics |

1.35 |

25 |

3 |

9 Aerospace |

4.1 |

120 |

17 |

10 Aerospace |

2.1 |

54 |

20 |

11 IT |

3.9 |

77 |

21 |

12 IT |

0.6 |

18 |

11 |

13 Telecommunications |

0.9 |

50 |

6 |

14 Automobile |

0.5 |

14 |

9 |

15 Food |

4.5 |

40 |

1 |

16 Oil |

55.0 |

1000 |

6 |

17 Chemicals |

2.18 |

5 |

10 |

18 Food |

1.4 |

20 |

8 |

19 Accountancy/Consultancy |

0.55 |

1 |

5 |

20 Brewing |

1.7 |

23 |

9 |

21 Food/Consumer |

2.5 |

27 |

1 |

* Operating costs.

† premium income.

Appendix B: Interview questionnaire

Structured (closed) questions

1 |

What prompted you to develop an IS/IT strategy? |

(RO) |

3 |

What were the objectives in developing an IS/IT strategy? |

(RO) |

4a |

What are the outputs of your IS/IT strategy development? |

(MC) |

4b |

What are the content headings of your IS strategic plan or strategy? |

(MC) |

5 |

What methods have you used in developing your IS strategy; when; why? |

(MC) |

7 |

What have been the benefits of strategic information systems planning? |

(RO) |

8 |

How successful has SISP been? |

(LS) |

9 |

What have you found to be key success factors in SISP? |

(RO) |

10 |

How is your SISP connected to other business planning processes? |

(MC) |

11 |

How do you review your IS strategies? |

(MC) |

12 |

What are the major problems you have encountered in SISP? |

(RO) |

All these questions were asked using multiple-choice lists (MC), Likert-type scale (LS), or rank-order lists (RO).

Example rank-order questions

3 What were the objectives in developing an IS/IT strategy?

Tick |

|

Rank |

...... |

Align IS development with business needs |

...... |

...... |

Revamp the IS/IT function |

...... |

...... |

Seek competitive advantage from IT |

...... |

...... |

Establish technology path and policies |

...... |

...... |

Forecast IS requirements |

...... |

...... |

Gain top management commitment |

...... |

...... |

Other (specify) |

...... |

Example multiple-choice questions

5 What methods have you used in developing your IS strategy; when, why?

When |

Method |

Why |

...... |

Critical success factors |

...... |

...... |

Stages of growth |

...... |

...... |

Business systems planning |

...... |

...... |

Enterprise modelling |

...... |

...... |

Information engineering |

...... |

...... |

Method 1 |

...... |

...... |

Other proprietary (specify) |

...... |

...... |

In-house IS strategy |

...... |

...... |

In-house business strategy |

...... |

...... |

In-house application search techniques |

...... |

...... |

Informal |

...... |

...... |

Other (specify) |

...... |

Example Likert-type scale question

8a How successful has SISP been on the following scale?

Semi-structured (open) questions

2a |

Please summarize the approach you have adopted in developing your IS strategy (or in identifying and deciding which IT applications to develop in the long run). |

2b |

What are the key elements of your IS strategy? |

6a |

Have you developed any applications that have given competitive advantage in recent years? If so, what? |

6b |

How was each of these applications identified and developed? |

8b |

In what ways has SISP been unsuccessful? |

13 |

Can you describe any key turning points in your SISP experience, such as changes in aims, approach, method, benefits, success factors or problems? |

Appendix C: Concerns or unsuccessful features of SISP

Method concerns

1 It did not lead to management identifying applications supportable at a cost

2 No regeneration or review

3 Failed to discover our competitors’ moves or understand their improvements

4 Not enough planning; too much emphasis on development and projects

5 It was not connected to business planning

6 It was too internally focused

7 Sensibly allocating resources to needs was a problem

8 Business needs were ignored or not identified

9 Not flexible or reactive enough

10 Not coordinated

11 Not enough consideration of architecture

12 Priority-setting and resource allocation were questionable

13 The plans were soon out of date

14 Business direction and plans were inadequate

15 Not enough strategic thinking

16 The thinking was too functional and applications-oriented and not process-based

17 It was too technical and not business-based

18 It was overtheoretical and too complicated

19 It could have been done quicker; it took too long

20 It developed a bureaucracy of its own

21 We have not solved identification of corporate-wide needs

22 The architecture was questionable; people were not convinced by it

23 We still don't know how to incorporate and meet short-term needs

24 We did not complete the company-entity model

25 We found it difficult justifying the benefits

26 It was too much about automating today's operations

27 It was too ad hoc; insufficient method

28 Many of the recommendations did not meet user aspirations

Process concerns

1 Some businesses were less good at, and less committed to, planning than others

2 The exercise was abrogated to the IS department

3 Inadequate understanding across all management

4 Line management involvement was unsatisfactory

5 Lack of senior management involvement

6 No top management buy-in

7 The strategy was not sold or communicated enough

8 We still have poor user-IS relationships

9 Too many IS people have not worked outside of IS

10 Poor IT understanding of customer and business needs

11 Line management buy-in was low

12 Little cross-divisional learning

13 IS management quality was below par

14 Senior executives were not made aware of the scale of change required

15 Users lacked understanding of IT and its methods

16 It was too user-driven in one period

17 We are still learning how to do planning studies

18 Planning almost never works; there are too many ‘dramas’

19 The culture has not changed enough

20 We oversold the plan

21 Too much conflict between organizational units

Implementation concerns

1 We have not broken the resource constraints

2 We have not implemented as much as we should

3 It was not carried through into resource planning

4 The necessary technology planning was not done

5 We have not achieved the system benefits

6 We made technical mistakes

7 Some of the needs are still unsatisfied

8 Appropriate hardware or software was not available

9 Cost and time budget returns

10 We were not good at specifying the detailed requirements

11 Defining staffing needs was a problem

12 We have not gotten anything off the ground yet

13 We had insufficient skilled development resources

14 Regulatory impediments

15 We were overambitious and tried to change too much

16 We still have to catch up technically

Reproduced from Earl, M. J. (1993) Approaches to information systems planning. MIS Quarterly, 17(1), March, 1–24. Copyright 1993 by the Management Information Systems Research Center (MIRSC) of the University of Minnesota and the Society for Information Management (SIM). Reprinted by permission.

Questions for discussion

1 Consider the success factors listed in Table 7.5 – is it worth undertaking SISP without top management involvement?

2 Compare the author's concept of SISP to that of information strategy from Smits et al. (in Chapter 3).

3 Debate the strengths and weaknesses of the approaches to SISP. Assuming time constraints prevent an ‘everything goes’ approach, which approach:

– might help improve IS credibility?

– might do the most to align IT with business strategy?

– might do the most to enable the competitive uses of IT?

– might do the most to achieve organization-wide vision?

– might be more appropriate at the different stages of growth?

– might best deal with management of change issues?

4 The author states that ‘successful SISP seems to require users and line managers working in partnership with the IS function’. Who should be involved in SISP and how should those involved be determined?

5 Given the alternative approaches identified in this chapter, think of a possible hybrid approach (keeping in mind time, resource and people constraints).

* An earlier version of this chapter was published in Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems, Copenhagen, Denmark, December 1990.