10 Measuring the Information

Systems–Business Strategy

Relationship

Factors that influence the social

dimension of alignment between

business and information

technology objectives

The establishment of strong alignment between information technology (IT) and organizational objectives has consistently been reported as one of the key concerns of information systems managers. This chapter presents findings from a study which investigated the influence of several factors on the social dimension of alignment within ten business units in the Canadian life insurance industry. The social dimension of alignment refers to the state in which business and IT executives understand and are committed to the business and IT mission, objectives and plans.

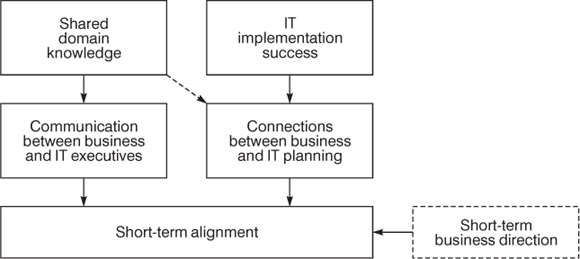

The research model included four factors that would potentially influence alignment: (1) shared domain knowledge between business and IT executives, (2) IT implementation success, (3) communication between business and IT executives, and (4) connections between business and IT planning processes. The outcome, alignment, was operationalized in two ways: the degree of mutual understanding of current objectives (short-term alignment) and the congruence of IT vision (long-term alignment) between business and IT executives.

A total of 57 semi-structured interviews were held with 45 informants. Written business and IT strategic plans, minutes from IT steering committee meetings, and other strategy documents were collected and analyzed from each of the ten business units.

All four factors in the model (shared domain knowledge, IT implementation success, communication between business and IT executives, and connections between business and IT planning) were found to influence short-term alignment. Only shared domain knowledge was found to influence long-term alignment. A new factor, strategic business plans, was found to influence both short- and long-term alignment.

The findings suggest that both practitioners and researchers should direct significant effort toward understanding shared domain knowledge, the factor which had the strongest influence on the alignment between IT and business executives, There is also a call for further research into the creation of an IT vision.

Introduction

In the last decade, the alignment of information technology plans with organizational objectives has consistently been among the top concerns reported in surveys of information systems managers and business executives (Brancheau et al., 1996; Business Week, 1994; Computerworld, 1994; Galliers et al., 1994; Neiderman et al., 1991; Rodgers, 1997). Academics have also devoted attention to the issue of alignment for a long time (Davis and Olson 1985; Henderson and Venkatraman, 1992; King, 1978). Several researchers have investigated the means of attaining alignment and its impact on organizational outcomes (e.g. Baets, 1996; Chan et al., 1997; Das et al., 1991; Kearns and Lederer, 1997; Nelson and Cooprider, 1996; Subramani et al., 1999). Although there has been much attention paid to alignment, no comprehensive model of this construct is commonly used. In this study, we add to the body of knowledge by focusing on the antecedents that influence alignment.

In the broadest sense, information technology (IT) management can be conceptualized as a problem of aligning the relationship between the business and IT infrastructure domain in order to take advantage of IT opportunities and capabilities (Sambamurthy and Zmud, 1992). In the research literature, there seem to be two approaches to the subject of alignment. The first concentrates on examining the strategies, structure, and planning methodologies in organizations (e.g. Chan et al., 1997; Henderson and Sifonis, 1988; Tallon and Kraemer, 1998; Zviran, 1990). The second investigates the actors in organizations, examining their values, communications with each other, and ultimately their understanding of each other's domains (Dougherty, 1992; Nelson and Cooprider, 1996; Subramani et al., 1999).

Support for this duality of approach is found in Horovitz (1984), who suggested that there were two dimensions to strategy creation: the intellectual dimension and the social dimension. Research into the intellectual dimension is more likely to concentrate on the content of plans and on planning methodologies. Research into the social dimension is more likely to focus on the people involved in the creation of alignment.

An earlier paper defined alignment as the degree to which the information technology mission, objectives, and plans support and are supported by the business mission, objectives and plans (Reich and Benbasat, 1996). In this definition alignment is conceptualized as a state or an outcome* (Broadbent and Weill, 1991; Chan et al., 1997). Determinants of alignment are likely to be processes, for example, communication and planning.

Combining the Horovitz duality with the notion that alignment is an outcome, the intellectual dimension of alignment is defined as ‘the state in which a high-quality set of interrelated IT and business plans exists.’ The social dimension of alignment is defined as ‘the state in which business and IT executives within an organizational unit understand and are committed to the business and IT mission, objectives and plans’ (Reich and Benbasat, 1996).

Although it is believed that both dimensions are important to study and are necessary for an organization to achieve high levels of alignment, the focus of the research reported here is solely on understanding the social dimension of alignment and the factors that influence it. This dimension of alignment has not been accorded the same degree of attention by IT researchers, even though the creation and maintenance of organizational understanding and commitment may be more problematic than developing IT and business plans in the first place.

There is support in the literature for studying the social dimension. For example, as Taylor-Cummings (1998) notes, the ‘culture gap’ between IT and business people has been identified as a major cause of system development failures. Mintzberg (1993) notes that formal planning is not the only way to create strategy. He suggests that relying on the strategic vision and strategic learning approaches, the latter based on integrating the views and visions of a number of actors, is a better means to cope with uncertain environments. Boynton and Zmud (1987) state that the current planning literature is based mainly on a rational model of organizational decision making. They note, however, that other models such as the political behavioral model or the resource dependency model also provide robust descriptions of the IT planning processes. In particular, the resource dependency model views these decision-making processes as ‘an organized anarchy where actors, their solutions, problems, and resources are intertwined to create an organizational structure where unpredictable outcomes regularly emerge’ (p. 69).

Another theoretical perspective supporting the concept of the social dimension of alignment is the social construction of reality (Berger and Luckmann, 1967). This view would suggest that, in addition to studying artifacts (such as plans and structures) to predict the presence or absence of alignment, one should investigate the contents of the players’ minds: their beliefs, attitudes, and understanding of these artifacts. This research attempts to measure the executives’ understanding of IT and business plans.

Other studies have also investigated the social dimension of alignment (e.g., Nelson and Cooprider, 1996; Subramani et al., 1999). The approach in those studies was to use statistical methods on a large sample in order to measure relationships between independent variables and alignment. A more interpretive approach (Klein and Myers, 1999) is taken here to discover how certain critical factors interact to create conditions that enable or inhibit alignment. While initially identifying a set of factors that have the potential to influence alignment, we are aware that there is no well accepted theory of the social aspects of alignment. Therefore, the research was exploratory. The approach to data collection and interpretation was open to revealing new factors and processes that might emerge as influential in affecting alignment. The units in the sample were examined in a holistic fashion, focusing on more than just the variables initially identified from previous literature, in order to understand the full context within which the various outcomes emerged.

The overall research goal was to (1) define the alignment construct, (2) develop measures for alignment, and (3) investigate the organizational factors and events that influence alignment. This chapter is primarily concerned with the third topic (the first two are described in Reich and Benbasat, 1994, 1996). The research reported herein is an in-depth investigation of the factors influencing alignment within ten business units of three Canadian life insurance companies.

The next section of this chapter presents the theoretical framework of the study and the propositions derived. The third section outlines the research methodology and measurement issues, and the fourth presents the findings. The final section discusses the major outcomes and provides some suggestions for research and practice.

The research model and propositions

A review of prior research (reported in Reich and Benbasat 1994) did not find a commonly accepted model to investigate the social dimension of alignment. Several categories of factors were identified that, according to the theoretical and empirical literatures, have the potential to influence alignment: external influences, IT characteristics, connections between IT and business planning systems, communication between IT and business executives, and implementation of previous IT plans. For the purposes of this research, to the extent possible, ‘external influences’ were controlled by collecting data from organizations in the same industry (life and health insurance). ‘IT characteristics’ were controlled by sampling from companies in which IT was accorded high strategic value, as measured by the IT budget and the proximity of the CIO to the CEO.

In addition, the concept of one of the subfactors, called ‘IT-knowledgeable line managers,’ was expanded and made a factor. The result was a factor called ‘shared domain knowledge,’ which refers both to IT-knowledgeable business managers and business-knowledgeable IT managers.

Using relationships reported in prior literature, factors were organized into the research model shown in Figure 10.1, which contains five constructs at three levels. Shared domain knowledge and IT implementation success are expected to affect both the communication between IT and business executives and the connections between business and IT planning, which in turn will influence (the social dimension of) alignment. In theory, the model in Figure 10.1 should be valid for any organizational unit in which the IT and business executives have the autonomy to develop their own strategic plans. A limitation of the model is that there is likely to be recursive causality between factors in complex organizations (Jang, 1989). While acknowledging this limitation, the model was used to guide the research. Also expected was that other relationships and constructs might emerge during the investigation.

Interestingly, the model is supported by one developed independently by Rockart et al. (1996) who, based on their observations and their adaptation of a framework by Earl and Feeny (1994), propose a set of relationships that parallel the ones in Figure 10.1. In their model, ‘increased business knowledge’ and ‘IT performance track record’ influence ‘IT/business executive relationships,’ which in turn influence a ‘focus on business imperatives.’ These variables parallel ‘shared knowledge,’ ‘IT implementation success,’ ‘communication between business and IT executives,’ and ‘alignment’ respectively in the current model. However, while the model by Rockart et al. has its focus on the IT side of the business (being a model of the key attributes of effective CIOs), the current model considers both the IT and business side, given that the definition of alignment used here refers to IT supporting, and being supported by, business.

It is important to compare the current model to prior research efforts in order to identify its unique contributions to the literature. Two other studies examined the social dimensions of alignment. Nelson and Cooprider (1996) found that mutual trust and mutual interest between IT and business people influence their shared knowledge, which in turn affects IT performance. Subramani et al. (1999) defined a ‘user gap’ as the difference between the user group's perspective on issues and the IT group's assessment of the user group's perspective. ‘IT gaps’ were defined in a similar way. They found that both the IT and user gaps were inversely related to the operational as well as service performance of IT; however, the IT related gaps had a stronger effect on IT performance than the user gaps.

Figure 10.1 Research model

These studies differ from the current one in that their focus is mainly on the relationship between alignment and IT performance (Chan et al., 1997; Subramani et al., 1999), or between shared knowledge and IT performance (Nelson and Cooprider, 1996). In contrast, the main interest of the current study is on identifying the factors that create or inhibit alignment. Another difference is that Nelson and Cooprider investigate the factors (mutual trust and interest) that lead to shared knowledge, whereas the current model does not investigate the antecedents of shared knowledge.

The following subsections discuss each of the potentially influential constructs in Figure 10.1. Each construct is introduced and propositions are generated to show the expected relationships between the constructs. Measurement approaches for each construct are discussed in the section on research methodology.

Communication between business and IT executives

There is ample evidence in the literature that communication leads to mutual understanding or alignment. Boynton et al. (1994) suggest that the effective application of IT depends on the interactions and exchanges that bind IT and line managers. Rogers (1986, p. 199) states that

participants create and share information with each other to reach a mutual understanding. Such information sharing over time leads the individuals to converge or diverge from each other in their mutual understanding of a certain topic.

Clark and Fujimoto (1987) note that successful linking depends on ‘direct personal contacts across functions, liaison roles at each unit, cross-functional task forces, [and] cross-functional protect teams. Littlejohn (1996) notes that as communication increases it is more likely that group members will share common ideas. Rockart et al. (1996) suggest that communication ensures that business and IT capabilities are integrated into the business effectively. Empirical support for the connection between communication frequency and convergence in understanding was reported in Lind and Zmud (1991). Luftman (1997) reported that the degree of personal relationship between IT and non-IT executives is a major factor influencing alignment.

Proposition 1: The level of communication between business and IT executives will positively influence the level of alignment.

Connections between business and IT planning

Much of the literature on alignment implicitly or explicitly assumes that the IT planning process is the crucial time during which alignment is forged. Partial support for this hypothesis was reported in a study showing that IT executives who participate more in business planning believe they have a better understanding of top management's objectives than those who participate less (Lederer and Burky, 1989). Support for the importance of connections in planning is also found in Zmud (1988), who argues that structural mechanisms (e.g., steering committees, technology transfer groups) associated with communications and management systems (e.g., planning and control mechanisms) are needed to build IT-line partnerships for the successful introduction of new technologies.

Proposition 2: The level of connection between business and IT planning processes will positively influence the level of alignment.

Shared domain knowledge between business and IT executives

Shared domain knowledge is defined here as the ability of IT and business executives, at a deep level, to understand and be able to participate in the others’ key processes and to respect each other's unique contribution and challenges. Nelson and Cooprider's (1996, p. 411) shared knowledge construct, developed concurrently, (i.e., an understanding and appreciation among IT and line managers for the technologies and processes that affect their mutual performance) is very similar, although their operationalization differed.

There is evidence in the organizational behavior literature about the importance of shared knowledge. Cohen and Levinthal (1990) note that common knowledge improves communication. Dougherty (1992) posited a relationship between ‘shared understanding’ and innovation. The shared domain knowledge construct has also been of interest to IT academics for more than a decade. Vitale et al. (1986) suggested ways to develop IT-knowledgeable line managers. There is empirical evidence on the importance of shared knowledge for IT-line partnerships (Henderson 1990), for IT performance (Nelson and Cooprider, 1996) and for IT use (Boynton et al., 1994). Rockart et al. (1996) indicate that increased business knowledge influences (and is influenced by) IT/business executive relationships.

Proposition 3: The level of shared domain knowledge within a business unit will positively influence communication between business and IT executives and connections between business and IT planning processes.

IT implementation success

There is evidence to indicate that past failures reduce the credibility of IT departments and the confidence line managers have in the competence of IT departments (Lucas, 1975). Failures also pose a threat to the working relationships between IT and business executives by lowering trust, cooperation, and support from users and management (Brown, 1991; Senn, 1978). On the other hand, a successful history of IT contribution is expected to increase the interest of business executives to communicate with IT executives and to have IT considered more fully and carefully in business planning because of the high value expected from IT utilization. Rockart et al. (1996) note that a successful IT track record improves business relationships at all levels.

Proposition 4: The level of IT implementation success will positively influence the level of communication between business and IT executives and the connections between business and IT planning processes.

Research methodology

Sample, informants, and data gathered

The sample for this project consisted of business units within three large Canadian-based insurance companies. These organizations offered similar products, primarily individual and group life, term, and health insurance. Their US divisions were not investigated. Their asset bases respectively were Canadian $1, $10, and $20 billion and all had a large national network of agents and brokers. Although budgets are not easily comparable, all three companies spent more than 15% of their operating expenses on IT. In the two companies that had IT steering committees, they were chaired by the CEO. This selection of organizations was made to reflect Yin's (1989) strategy of ‘literal replication’ in which all cases are theoretically the same.

Within these three companies, ten business units were studied, with four taken from each of the two larger companies and two from the smaller company. Each business unit had responsibility for setting its own strategic goals and plans, and each had an IT department contained within it which designed and built its information systems. All of these IT units were supported by a corporate IT unit with responsibility for developing standards, technology infrastructure, and the communications network. Although not all of the IT units had been stable in size during the last few years, all senior IT executives had at least ten years of experience and all had worked for most of their career in the insurance industry. Table 10.1 contains the demographic characteristics of the business units studied, the number of executives interviewed, and the written documents gathered.

Informants having the following roles within the business unit were interviewed: senior vice presidents of the business unit; vice presidents of marketing, administration, and new business; IT vice presidents and assistant vice presidents, and directors of systems development or IT planning. Also interviewed were members from all of the IT steering committees, and heads of the IT research function. Although each person interviewed was asked a core set of questions concerning the factors and alignment, each role was expected to produce unique data on the site and ‘role questions’ were included in the interview. For example, IT executives were asked to talk about the formation of the IT plan. The senior IT executives were interviewed several times, since they were the people most knowledgeable about the IT implementation success within the organization.

In total, 45 long (two to three hours) interviews with 37 informants were conducted. In addition, a wealth of written material was collected from each site, including annual reports, the most recent one and five year business and IT plans, minutes of IT and management committee meetings, and IT strategy papers (see Table 10.1).

Measurement of constructs

An earlier measurement paper (Reich and Benbasat, 1996) identified two aspects of the social dimension of alignment, namely short-term and long-term alignment. While short-term alignment refers to shared understanding of short-term goals, long-term alignment refers to shared understanding of IT vision. These two dimensions were found to be distinct because some organizations had achieved high levels of one while rating low on the other.

Table 10.1 Business unit (BU) characteristics and data gathered

BU |

# of IT |

Line of business |

Executives interviewed |

Written data gathered-reports and |

1 |

100 |

Individual insurance |

3 BU Executives 2 IT Executives |

Five year business strategy, five year operating plan, annual plan, minutes from BU planning meetings; draft IT strategy. |

2 |

100 |

Group insurance |

3 BU Executives 2 IT Executives |

Five year business strategy, annual plan; annual IT plan, four IT strategy reports. |

3 |

45 |

Retirement Assets |

3 BU Executives 2 IT Executives |

Draft five year business strategy, annual plan; two years of annual IT plans. |

4 |

29 |

Investment |

1 BU Executive 1 IT Executive |

Draft annual business plan, previous year's business plan; two annual IT plans, previous IT strategy. |

5 |

17 |

Individual insurance |

2 BU Executives 1 IT Executive |

Annual business plan; IT project plan. |

6 |

26 |

Group insurance |

2 BU Executives 1 IT Executive |

Annual business plan; annual IT plan. |

7 |

40 |

Individual insurance |

2 BU Executives 1 IT Executive |

Five year business strategy, annual plan; five year IT plan, annual IT strategy and project plan, six months of IT steering committee minutes. |

8 |

24 |

Group insurance |

2 BU Executives 1 IT Executive |

Five year business strategy, annual plan; annual IT plan, five months of IT steering committee minutes. |

9 |

15 |

Retirement Assets |

3 BU Executives 1 IT Executive |

Two five year strategic business plans, annual plan; annual IT plan, three months of IT steering committee minutes, IT directions document. |

10 |

9 |

Reinsurance |

2 BU Executives 2 IT Executives |

Five year business strategy, annual plan; two months of IT steering committee minutes, IT strategy. |

Short-term alignment is defined as the state in which business and IT executives understand and are committed to* each other's short-term (one to two year) plans and objectives. This aspect was operationalized by interviewing senior business and IT executives, asking them to identify both current business and IT objectives/plans, and measuring the level of understanding that IT executives have of current business plans and business executives have of current IT plans.†

Long-term alignment is defined as the state in which business and IT executives share a common vision of the way(s) in which IT will contribute to the success of the business unit. This aspect of alignment was operationalized by asking business and IT executives to articulate their visions for IT and the authors measured the degree of congruence between these visions.

Examples of alignment ratings have been placed in Appendix A, since they repeat material in the previous chapter.

Measuring communication between business and IT executives

Galbraith's (1977) typology of seven techniques, thought to increase communication between two separate units, can be used to capture many of the ways in which IT and business executives interact. The six most pertinent techniques are listed below, in order of the degree (according to Galbraith) to which they contribute to connecting the objectives of two organizations:

1 Direct communication (e.g., communication between business and IT executives, such as regular or ad hoc meetings, electronic mail or written memos).

2 Liaison roles (e.g., a named person as liaison between IT and a line function).

3 Temporary task forces (e.g., IT project team, new product development team).

4 Permanent teams/committees (e.g., IT steering committee)

5 Integrating roles (e.g., IT person leads the business quality team).

6 Managerial linking roles (e.g., product management role).

The typology was used in this study to formulate interview questions identifying the type and number of these techniques employed in any one business unit. Data were collected from individuals in interviews and corroborated with written documents (e.g., minutes from meetings). These strategies allowed identification of much of the recurring business communication between business and IT executives. These data were used to identify business units with ‘low,’ ‘moderate’ or ‘high’ levels of communication between business and IT executives.

Measuring the connections between business and IT planning

Several descriptive and prescriptive typologies (Galliers, 1987; Henderson and Venkatraman, 1992; Jang, 1989; Kottemann and Konsynski, 1984) have converged on five generic types of IT planning. From these, a five-level scale of planning styles (shown in Table 10.2) was developed based on the degree of connection between business and IT planning processes. Each level is progressively higher in its ‘level of connection’ between business and IT objectives and its potential to create alignment.

Each informant in the business unit was asked to describe the steps in the most recent IT and business planning processes. Using their descriptions, we classified the connection between business and IT planning processes, based on the typology shown in Table 10.2. Level 1 was characterized as being ‘low,’ levels 2 and 3 as being ‘moderate,’ and levels 4 and 5 as being ‘high’ levels of connection.

Table 10.2 Scale of connection between business and IT business planning processes

Connrating |

Level |

Name |

Dominant characteristics |

Low |

1 |

Isolated |

IT and business plans are developed separately, or not at all, |

Mod. |

2 |

Architected |

IT plans are developed from data and application architectures. |

Mod. |

3 |

Derived |

IT plans are developed during a top-down analysis beginning with business objectives. |

High |

4 |

Integrated |

IT plans are developed and ratified at the same time as other business objectives are. Business and IT executives are both present in the planning. |

High |

5 |

Proactive |

IT objectives precede the formulation of business objectives and are used as input to their development. IT is considered to be significant in changing the basis of competition. |

Measuring shared domain knowledge

Shared domain knowledge was operationalized as work experience and measured by assessing the actual amount of IT experience among the business executives and the actual amount of business experience among the IT executives.

Business knowledge was conceptualized as the aggregate of two dimensions: (1) experience in the insurance industry and (2) experience as a line supervisor or manager. It was felt that both dimensions were important to one's ability to participate in strategic decisions within a line insurance unit. IT knowledge was also conceptualized as having two core dimensions: (1) familiarity with new technology and (2) experience in implementing IT projects. If a line manager possessed both of these dimensions, the feeling was that he/she could identify opportunities for the utilization of new IT and could implement agreed-upon projects within the business unit.

Each interviewee's entire education and work history was elicited and shared knowledge was rated using the scales shown in Table 10.3. The years used to separate the rating categories had been reviewed and validated by a focus group of IT executives.

Table 10.3 Measuring the shared domain knowledge (SDK) factor

Type of SDK |

Variables |

High level |

Moderate level |

Low level |

Business knowledge |

Insurance Experience |

>10 years in line roles |

Between 5 and 10 years |

Under 5 years |

|

Line Management Experience |

>5 years |

Between 3 and 5 years |

Under 3 years |

IT knowledge |

IT Management Experience |

>2 years in IT management |

Management of a large IT project |

User level involvement only |

|

Awareness of new information technologies |

Frequent reader of IT periodicals and experimenter with IT |

Occasional reader or experimenter with IT |

Seldom reads IT periodicals or experiments with IT |

The first two variables were aggregated to indicate the level of ‘business knowledge’ of each IT executive, and the last two, taken together, indicated the level of ‘IT knowledge’ of the business executive. Because the objective was to represent the entire business unit executive group with this rating, interviewees were asked their opinions of other executives who were not interviewed. Then, an aggregate rating of ‘high,’ ‘moderate,’ or ‘low’ was assigned to the business unit which represented the level of shared domain knowledge among the executives. If both business and IT executives rated highly, the business unit would rate ‘high.’ If neither rated highly, the business unit was rated ‘low.’ If there were mixed levels of knowledge, the unit was rated ‘moderate.’

Measuring IT implementation success

To assess the previous IT implementation success, each interviewee was asked several questions about IT activities during the last two years, including.

1 Name the major projects started in the past two years.

2 How successful were each of the major projects?

3 Overall, how well were the IT plans implemented?

In addition, open ended questions about the general IT history within the business unit were asked. Major IT decisions were discussed to determine whether they were characterized as successes or failures. These questions resulted in a rich understanding of the details of past projects and the various opinions about IT implementation success up to a decade before the interviews. The remarks of the interviewees in each business unit were analyzed and aggregated, and the overall level of success in IT implementation was assigned a ‘high,’ ‘moderate’ or ‘low’ rating.

Data collection and analysis

Data collection and analysis took approximately 12 months, full-time, for the first author. Within-unit analysis accounted for seven months of this time and across-unit analysis for four months.

Within-unit analysis

The data collection and analysis process for each business unit consisted of two major phases: (1) preparation of the site report and (2) verification of the site report. The preparation of the site report phase consisted of the following steps:

• perusal of written documents and customization of interview guides with local ‘jargon,’

• conducting interviews and creating field notes,

• analysis of transcribed interview tapes, field notes, and written documents to prepare a site report.

The site reports, single spaced, were between 15 and 35 pages long. The first author prepared the site reports, each of which contained the following sections: business background, IT background, alignment measures, factor measures, and interpretive causal analysis. The intent was too look for explanations, based on data originating either from the informants or inferred by the researchers, that would link constructs together in plausible ways.

Steps were taken to ensure that the interview data collected, especially those dealing with the more factual aspects of the organization's history, could be verified to the extent possible. Based on an analysis of written documents; important events, including major decisions and projects, were identified. These were used in the interviews to investigate in more detail the actions of the interviewees, and others in the organization, with respect to these events. Specific details of behavior (e.g., the number of meetings attended or names of committees one served on) were requested to ascertain whether the data collected were accurate and reliable.

Data for the causal analysis were gathered during interviews, as informants proffered explanations for or were asked about situations that seemed unusual. For example, in BU 7, business executives were asked to explain why the IT executive participated in so many non-IT task forces. In BU 9 the head of the unit was asked to explain why he could not recall any of the IT objectives. These questions and the informants’ natural tendency to explain and interpret their actions resulted in many causal statements (e.g., ‘moving closer to the business people has made a lot of difference to our communication . . . We see them at coffee and in the hallway’). These data were included in the site report when they were in line with prior expectations, when they were novel but plausible, or when they were mentioned by more than one informant. The first author also ‘created’ causal chains based on the data and her interpretations of it (e.g., the IT director has no insurance experience AND attends no meetings with the business executives, therefore cannot explain the business objectives).

The second phase, verification of site reports, consisted of an analysis of the site report by the second author, who questioned the credibility of the conclusions and probed for missing data. Each report contained quotes from interviews, quotes from written documents, and interpretive comments in order to expose the second author to as much raw data as possible (Sviokla, 1986; Yin, 1989) so that he could follow the line of reasoning and thus check the credibility of the conclusions reached. Transcripts of the audio interviews were also made available to the second author. In a few cases, the second author requested a re-analysis and this was done.

After this step, the site report was amended by removing direct quotes and other data which would breach the anonymity of individual informants, and then sent to the senior IT executive, who was asked to check the reports for factual errors and to comment on the causal analysis. Realizing that wider organizational review would have been optimal, this was left to the IT executive to arrange if he/she so desired. Eight informants annotated and returned their write-ups and two of the ten sites were debriefed verbally. One site requested changes based on missing information. A follow-up phone interview and meeting were held to correct the site report.

Across-unit analysis

The next phase was the analysis across business units. There were three steps: (1) a re-examination of the ratings for each factor, (2) a within-company analysis, and (3) an evaluation of the influence of each factor on alignment.

First, each factor, including alignment, was examined across all sites to ensure that the scales had been applied consistently. Approximately three months were spent in re-examining the raw data and re-rating the sites. This effort resulted in a few adjustments in the ratings, some recalibration of scales (reported in the following section) and increased reliability of the interpretive analysis.

Second, a within-company analysis was performed to identify any company-level factors which might have influenced either the short or long-term alignment ratings. Within each of the three companies (BUs 1 through 4, 5 and 6, and 7 through 10 belonged to the three companies respectively), there was little consistency in the short-term alignment ratings. Each of the large companies had at least one business unit which rated high, moderate, and low on short-term alignment. The smaller company (BUs 5 and 6) had only moderate ratings. It was thus concluded that company characteristics did not influence short-term alignment.

Two of the companies exhibited wide variance in the long-term alignment ratings for their business units. However, in the third, there was some consistency in the long-term alignment ratings. The four business units in this company (BUs 7 through 10) reported low, low, moderate and no IT vision, respectively. There may be some connection between the consistency of results and the overall performance of this company. Although it had enjoyed many decades of superior performance, the last two years had been difficult. Poor investments and a bad experience with US health care products had weakened the company to the point where its parent company had begun looking for a buyer. While no one in any of the interviews alluded to this fact, it may have undermined their confidence for the future and may have influenced our low long-term alignment findings.

Figure 10.2 Ratings on the two dimensions of alignment (short-term), understanding of current objectives and (long-term), shared vision for IT

Third, the ratings on alignment were used to create four groups of business units. These were the high or low performers on short and long-term alignment, respectively. Data on the factors and on the history of each business unit were interpreted to create ‘lines of reasoning’ (Yin, 1989). Resulting explanatory models of short and long-term alignment were constructed. No statistical analysis was done due to the exploratory, interpretive, and qualitative nature of these investigations (Miles and Huberman, 1994).

Results

In Figure 10.2, each circle represents a business unit in the study and its rating on long- and short-term alignment*

To understand more about factors that may have influenced these alignment ratings, business units were separated into four groups for analysis. The groups represented the extreme cases, that is, the business units which achieved either a high or a low rating on short or long-term alignment. Causal analysis was used to determine if the constructs in the model could be used to explain alignment. Results are presented next with detailed data from two of the business units BU 1 and BU4, used throughout the presentation to illustrate the analysis. Findings associated with short-term alignment are discussed first, followed by findings on long-term alignment.

Short-term alignment

Three business units (1, 9, and 10), were rated as having a high level of short-term alignment; three business units (3, 4, and 8) were rated low or low/moderate. Data on the constructs in the research model are shown in Table 10.4. High values are shown without shading, moderate values are bold and italicized, and low values are bold, italicized, and have heavy borders.

Data across the business units shown in Table 10.4 seemed to show general support for the research model. Each business unit was examined to see if there was evidence to allow causal inferences to be drawn. In the next sections, data from the most extreme cases, BU 1 and BU 4, will be used to illustrate how these factors can interrelate and influence short-term alignment. BUs 9, 10, and 3, which showed only partial support for the model, will then be discussed and conclusions drawn. BU 8 is not discussed since it adds little to our understanding of the phenomena.

Causal analysis of Business Unit 1

Business Unit 1 sells life and health insurance to individuals in North America through independent life insurance agents. The 700 agents in Canada are managed out of twenty agency offices. There are five vice presidents below the senior vice president in BU 1, one in charge of new business, three in charge of the agency offices, and one in charge of both client services (administration) and systems. Therefore, the senior person in charge of systems is also in charge of administering the inforcement of insurance policies, and providing service to the policyholders. This organizational structure gives the VP of IT more positional power than any other head of IT in the study sample. There are over 100 professionals within the systems department, grouped into agency systems and administrative systems areas.

Within BU 1, the level of shared domain knowledge and IT Implementation success were extremely high. Interview data revealed a decade of effort to produce these results and strong indications that they had influenced communication and short-term alignment.

An abbreviated history of BU 1 is shown in Table 10.5.

A spiral whereby one success leads to another can be seen in BU 1. First, early implementation success and business knowledge in the head of systems led to high levels of communication. Second, deliberate creation of shared knowledge within IT led to more success in implementation. Consequently, IT people were welcomed onto cross-functional teams and into remote sales branches. This also increased the level of communication, which then led to higher levels of understanding between IT and business executives.

Table 10.4 Factors for BUs with high or low ratings on short-term alignment (high values are shown in normal font, moderate values in bold italics, and low values in bold italics inside heavy borders).

Alignment, BU |

Communication |

Connections in planning |

Shared domain knowledge |

IT implementation success |

HIGH BU 1 |

Two days of executive meetings per month, two other crossfunctional teams. IT visits to each of 20 sales branches several times per year. |

All projects, including IT, are discussed and voted on at the same meeting. |

IT VP has 10 years line experience. Five administrative managers are ex-IT people. |

Leader in use of IT in Sales, stable administrative backbone in place. |

HIGH BU 9 |

IT executives sit on several permanent cross-functional teams. |

BU objectives drive all planning; IT and line projects are integrated. |

Line executives have some IT experience. IT executives have years of line experience. |

BU is trying to catch up after several flawed implementations Partial progress. |

HIGH BU 10 |

Two cross functional teams. High level of direct contact between IT manager and executives. |

IT plan is created after business plan is drafted. |

Low level of cross-functional experience. |

Successful IT implementations, innovative PC systems. |

LOW-MOD BU 3 |

Six frequently-meeting permanent teams include both IT and line managers. |

IT director is in charge of business planning. Tight connections between all areas. |

Most line executives have managed IT projects. One IT executive has line experience. |

This young BU has mixed success to date. |

LOW BU 8 |

One permanent management team, meets weekly. Otherwise infrequent contact between IT and line managers. |

IT plans are derived from SVP's overview plan. No integrated planning. |

Line executives have no IT experience. IT executive has line experience but in another unit. |

Mixed success with IT implementation. |

LOW BU 4 |

No regular meetings of executives and IT director. |

Each executive makes his/her own plan, submits only budgets for discussion. |

IT manager is a career IT person; no line person has direct IT experience. |

EIS was discontinued, large strategic IT project is 2 years late and 500% over budget. |

Table 10.5 Processes and events influencing short-term alignment within BU 1

Time |

Processes and events within BU 1 |

Interpretation |

1954–1982 |

Career path of head of systems for BU 1: 10 years in policyholder services; eight years of liaison between his unit and IT; 10 years in corporate IT. |

Result: IT head acquires both business and IT knowledge before joining BU 1. |

1979–1982 |

BU 1 successfully implements a large database system to support policy administration. As soon as it is installed, BU 1 is one of the first companies in Canada to give agents PCs and access to policy data. |

Result: IT group has high credibility in BU 1. |

1983 |

IT group is decentralized into Individual business units from corporate IT. The new head of systems has several duties. ‘When I moved over to Individual [from corporate IT], the SVP thought the best way to insure that there was good integration between systems and the line was to give me responsibility for the business planning function, I also wanted some involvement with a line function. So when I moved over, I was responsible for line of business planning, sales compensation, and systems.’ |

Reason: Cross-functional responsibilities resulted from his high level of business knowledge and the successful IT implementations. |

1982–1992 |

Head of systems promotes shared domain knowledge by encouraging IT people to do the FLMI program (10 insurance courses). To date, 90% of senior IT people have it. He also hires line people into IT positions. ‘We don't let somebody work on a project if they don't understand the business purpose of the project.’ |

Result: Level of shared domain knowledge was systematically increased within BU 1. |

1987 |

Head of systems is promoted to being VP, client services and systems. |

Reason: Promotion is due in part to his shared domain knowledge. |

VP of systems institutes a practice whereby IT people visit each of 20 sales branches at least once a year and the director of sales systems goes to sales conferences four times a year. The SVP told us how unusual this practice was: ‘ I asked the question [to 20 heads of IT from the top individual life carriers in North America], how many people have been in an agency office in the last year? And [my head of Systems] was the only one that held up his hand.’ |

Reason: IT people are welcomed into branches because they have some business knowledge. |

|

By 1992 |

Business and IT planning processes are indivisible. One meeting is held at which all projects (including IT, marketing, new products, etc.) are considered and voted on. |

Result All units hear about and discuss the Sales system which represents their long-term vision. |

By 1992 |

IT implementation success is high; Certainly on the administrative side, we've grown very substantially while we were holding staff pretty well level. Where I would also say we've done an excellent job, well ahead of the industry in Canada, is on support for the sales process . . . agents are pretty enthusiastic about what we've done . . . we have one of the best retention rates. |

Reason: IT people are widely respected for their business knowledge. This increases the likelihood of mutual support and therefore success during the IT implementation process. |

By 1992 |

Very high level of mutual understanding of objectives (short-term alignment) between IT and line executives. |

Reasons: Short-term alignment is due to multiple channels of communication and integrated planning processes. |

Causal analysis of Business Unit 4

Insurance companies rely on investment profits to cover the gap between the cost of selling insurance policies and the revenue that this business generates. BU 4 is responsible for investing the monies that are generated by the life and health insurance product lines. In the year of the interviews, this business unit generated $2 billion in net investment income, an increase of 9% over the previous year's results. They were a successful unit.

The business unit is structured so that the various types of investments are headed up by four vice presidents and the service functions of accounting and systems report to the senior vice president. The director of systems manages an IT staff of 25 employees.

Within BU 4, we rated the level of short-term alignment as low. The director of systems rated alignment as:

Lower than low. Right off the scale. I've been the guy with complete control over the budget, its priorities and what exactly we work on, other than the most recent fire. And it scares the hell out of me, because it's absolutely wrong. It smacks of having no tie to the business direction.

A line vice president concurred, rating alignment as:

Low, because the systems people are working in a vacuum, they have no sponsorship, no business input, they are spending a lot of money, and there is no acceptance of line management responsibility.

The history of IT within BU 4 was traced back five years and some evidence was found that the lack of shared domain knowledge and a lack of IT implementation success had played an influential role. An abbreviated history of BU 4 is shown in Table 10.6

In BU 4, a situation exists in which an experienced IT manager joins the business unit as head of systems. He has no real access to business unit management, because he does not sit on the senior committees. He does not understand core investment work, which is focused on decision support, access to data, and desktop tools. He has no line experience and no insurance courses and his counterparts, the line executives, have very little experience with IT projects. The first new IT project, an executive information system, fails. The second project is a disaster in terms of budget and time. Line management takes no responsibility. According to the business executive:

There's a built-in bias here when the group closes ranks. Because there's no one [i.e. no IT person] at the meetings to scream, ‘There's no business input in this . . . project,’ everyone says, ‘Those systems people screwed up again. And you can just shift the whole blame off to the other guy. He's not even in the meeting, so you can really beat him about the head. And everybody feels so much better after they've done that.

Table 10.6 Processes and events influencing short-term alignment within BU 4

Time |

Processes and events within BU 4 |

Interpretation |

1969–1987 |

Career path of head of systems for BU 4: 18 years in corporate IT. For 7 years before he joined the BU, he developed mainframe systems for BU 4. |

Result: IT head has a good knowledge of mainframe investment systems, but has no line experience. |

1982–1987 |

BU 4 executives are not involved in the IT projects, spend some time in developing PC-based systems for analysis of investment options. |

Result: BU 4 executives are more conversant with PC technology, have little large systems experience. |

1987 |

IT group is decentralized into investment business unit from corporate IT. First IT event is a demonstration of new mainframe transactions and algorithms. Not much interest is shown in this. |

Result: Executives see no reason to talk to IT people, no channels are created. Head of systems does not sit on the management team. |

1988–1990 |

Two IT Initiatives are commenced: a giant asset-matching mainframe system and an Executive IS. The EIS had mixed support and was cancelled when the champion was transferred. The mainframe system was starved of resources and made little progress. |

Reason: Executives have no experience in championing large projects. IT director has no access to executives, no real understanding of the workings of the BU. |

1990–1992 |

During the project, IT cannot communicate with line managers. As a line VP remembers: ‘we hear a lot about it [the big systems project], we don't see very much. We know it's been delayed, we know it's overrun on costs, we don't know what the problems are, we've had people try to explain them to us, and never understood it all. Most times, when systems people come in to explain something, the tendency is to lapse into the jargon and it just . . . whew! . . . right over our heads. And you tend to fall asleep in the process. So you say, well, it must be working, somebody says it's going to come together, and I guess . . . we'll find out. |

Reason: No shared language has been established; no trust exists between the line and IT. |

By 1992 |

Very low level of mutual understanding of objectives (short-term alignment). ‘ Right now, the responsibility is all on him [the head of systems] to do a mind read of everybody, do it in a way that somehow sees something that the other guy doesn't even know exists, and comes up with the right answer. Impossible. But we sit back as management and say, ‘You systems people, boy.’ It's kind of a no-win situation.’ |

Reason: Low levels of shared knowledge has led to low levels of IT implementation success and low levels of alignment. |

When interviewed, the executives exhibited very low levels of mutual understanding of objectives.

BU 4 also exhibits very low connections between IT and business planning. This could be interpreted as a result of the low level of shared domain knowledge or the lack of IT success. However, a wider appraisal of BU 4 planning practices reveals that very few strategy meetings of any type are held in BU 4. Budgets are discussed, strategies are not. Therefore, what initially looks like strong confirmation of the model is an artifact of the absence of a planning culture within BU 4.

The strongest influences in this business unit seem to be from the lack of shared knowledge between the IT and the business managers. They cannot speak each other's language and, as a result, leadership is abdicated and IT projects fall. IT managers are kept out of the decision-making loop with the result that no shared understanding is created.

Business Units 9 and 10: contingent findings

BUs 9 and 10 exhibited mixed support for the model and were investigated further to try to determine the causalities within them.

In BU 9, the interest was in what impact a low level of IT implementation success had on an otherwise successful organization, since the model suggested that such a lack might inhibit alignment. The analysis revealed that the very high level of shared domain knowledge among executives had resulted in opening up many channels of communication between them. The vice president was committed to information technology (IT is the competitive advantage in our business . . . I am a complete believer that technology can radically change the cost structure and the way we do work). Even though the recent implementations had been only partially successful, their mutual respect and belief in IT had led them to a redoubling of efforts rather than a pulling away from IT or a deterioration in communication. When interviewed, BU 9 executives exhibited a high level of mutual understanding of objectives. The conclusion was that the high level of shared domain knowledge had mitigated the expected influence of poor IT implementation success. This finding is shown on Figure 10.3 with a dotted line.

BU 10 was an opposite case (low shared domain knowledge, high IT success, high level of mutual understanding of objectives), and an investigation was undertaken to determine the effect of his low shared domain knowledge. The peculiarity of this case was in the nature of its IT history. Within this small business unit, both business managers and IT people had worked for the last five years to implement PC-based technology in direct contravention of corporate IT policy. They had the first local area network in this large organization and used it very successfully for production systems and low-cost local e-mail. This and other accomplishments seemed to have bound the IT and line people together into a highly cohesive team. Unfortunately, the method of rating shared domain knowledge as cross-functional experience used in this study seemed to be too restrictive for this business unit because their very close cooperation on projects over a long period of time had imbued both the head of the business unit and the IT manager with a deep understanding of each others’ domain. A more holistic scale for shared domain knowledge might have resulted in a different score. Therefore, the finding from this business unit was that the scale for shared domain knowledge should reflect long-term working relationships as well as job transfers.

Figure 10.3 Explanatory model for short-term alignment

Business Unit 3: a lack of business direction

The previous discussion developed the argument that a high level of shared domain knowledge or a high level of IT implementation success would lead business units to high levels of communication and, through this mechanism, to high levels of short-term alignment. BU 3 is an anomaly to this argument, in that it displays high or moderate levels of the preconditions, but low levels of short-term alignment.

BU 3 was a newly created business unit and was just in the process of formulating a set of one to two year objectives. When questioned, executives could not articulate these, thereby achieving a low rating on short-term alignment. Consideration was given to eliminating BU 3 from the data set because it was younger than the other business units and therefore might contaminate the findings. However, the belief is that there are more reasons than age that could create the situation of unarticulated short-term business plans (for example, a recent industry ‘shock’ or a recent negative shift in organizational fortunes). In these cases, the business units might be of mature age but not exhibit any short-term alignment because of a lack of short-term objectives. The existence of a short-term business direction was therefore added to the model (see Figure 10.3). This direction would consist of a set of one to two year objectives, either found in written plans or articulated by management. This is believed to be a necessary precondition for short-term alignment.

Conclusions: short-term alignment

When the data were analyzed within each business unit shown in Table 10.4, the strongest resulting explanatory model contained five influential elements: shared domain knowledge, IT implementation success, communication, connections in planning and short-term business direction. The relationships suggested by the data are shown in Figure 10.3.

Apart from the prerequisite factor of a short-term business direction, the biggest distinction found between business units with high and low levels of short-term alignment was the frequency of structured and unstructured communication between IT and line executives. The conclusion was that, over time, executives in a business unit create the kind of communications environment that is comfortable for them. Those who are respected are able to get involved in activities that are well outside their sphere of influence. Those who are not respected tend to get left out, either by not being invited onto senior committees or by not being involved in discussions about important business issues.

How do IT people gain admission to cross-functional committees and informal discussions? From BUs 1 and 4, it can be seen that two factors, shared domain knowledge and IT implementation success, can interact to produce high or low levels of communication. From BU 9 and 10, the conclusion is that having both a high level of IT implementation success and a high level of shared domain knowledge may not be necessary for high levels of communication. It seems that high levels of either can result in high levels of communication, and through this mechanism, lead to high levels of short-term alignment. Further, it seems that very high levels of shared domain knowledge can compensate for the expected influence of a low level of IT implementation success.

The connections in the planning construct had a moderate influence on short-term alignment, but no strong evidence could be found that planning practices were influenced by shared domain knowledge or IT implementation success. Contrary to communication patterns, which resulted from a mix of organizational and individual preferences, connections in planning seemed to reflect only organizational practices. In other words, if a shared planning process existed between IT and the line, one would also expect to find shared planning between most other units in the organization. If no planning process was found in IT, most likely there would be little planning done in the business units. The problems encountered in measuring and gauging the influence of this construct will be further discussed in the long-term alignment section.

Long-term alignment

Three business units (1, 3, and 5), were rated as having a high and three (4, 6, and 10) as having a very low level of long-term alignment (i.e. no vision). Data on the constructs in the research model are shown in Table 10.7. High values are unshaded, moderate values are bold and italicized, and low values are bold, italicized, and have heavy borders.

As can be seen from an examination of the data, there is some general support for the model, but only the shared domain knowledge construct unambiguously distinguishes the high achievers from low achievers in creating a shared vision for IT. The data from each business unit were examined to look for evidence of causality.

Since the history of BU 1 and BU 4 was discussed earlier in the context of short-term alignment, only aspects that relate directly to long-term alignment will be examined here. BUs 5 and 6, which showed only partial support for the model, will then be discussed and conclusions drawn. BUs 3 and 10 are not discussed since their stories support the model.

Before beginning the discussion about long-term alignment, it should be noted that the respondents in business units with a high level of long-term alignment were not aware of or could not communicate exactly when their IT vision had been formed, it seemed to be just an accepted fact that they would spend most of their IT development resources in one part of their business. No insight was found about a particular time, either during a planning session or a senior management meeting, when the strategy was created.

Causal analysis of Business Unit 1

BU 1’s long-term vision for IT was to concentrate on empowering the salespeople with information analysis tools, and the ability to complete transactions at the customer's site. Implementation of this sales system would make the company a world leader in individual life sales processes. An interesting aspect of this goal is that it focused on only the major parts of the organization (sales; new business) of which the VP of IT was not in charge (he was also the VP of administration).

Table 10.7 Factors for BUs with ‘High’ or ‘No Vision’ Ratings on Long-term Alignment (high values are shown in normal font, moderate values in bold italics, and low values in bold italics inside heavy borders.)

Alignment, BU |

Communication |

Connections in planning |

Shared domain knowledge |

IT implementation success |

HIGH BU 1 |

Two days of executive meetings per month, two other crossfunctional teams. IT visits to each of 20 sales branches several times per year. |

All projects, including IT, are discussed and voted on at the same meeting. |

IT VP has 10 years line experience. Five administrative managers are ex-IT people. |

Leader in use of IT in Sales, stable administrative backbone in place. |

HIGH BU 3 |

Six frequently-held-meetings permanent teams include both IT and line managers. |

IT director is in charge of business planning. Tight connections between all areas. |

Most line executives have managed IT projects. One IT executive has line experience. |

This young BU has mixed success to date. |

HIGH BU 5 |

One permanent team with IT and line executives. Lots of direct contact between SVP and IT executives. |

IT plans are derived from business plans. No integrated planning or review. |

SVP has Master's in Computer Science; IT manager has line experience. |

Implementation success has been very mixed, mainly negative. |

NO Vision BU 6 |

Frequent contact between IT manager and SVP. IT executive is also in charge of administration (similar to BU 1). |

Agents have input into the type and the priority of IT projects. Offsite planning includes IT manager. |

One executive has a high level of IT experience. IT manager is also in charge of administration. |

Although BU6 was successful in the mid-1980s, their recent IT projects have not been successful. |

NO Vision BU 10 |

Two cross-functional teams. High level of direct contact between IT manager and executives. |

IT plan is created after business plan is drafted. |

Low level of cross-functional experience. |

Successful IT implementations, Innovative PC systems. |

NO Vision BU 4 |

No regular meetings of executives and IT director. |

Each executive makes his/her own plan, submits only budgets for discussion. |

IT manager is a career IT person; no line person has direct IT experience. |

EIS was discontinued, large strategic IT project is 2 years late and 500% over budget. |

No evidence was found to suggest that the planning meetings within BU 1 were the critical times at which the IT vision was formulated. In fact, there were no separate IT planning meetings. At the business planning meetings, although the sales system project was thoroughly discussed and endorsed, vision did not appear to originate there.

The construct that helped in understanding how they could have forged this vision was communications. Because the IT people were regularly visiting the sales offices (unlike IT people in most other insurance organizations in North America) there seemed to have been a deep understanding formed within IT that this area offered the most leverage to the business. A dialogue had ensued with business executives about the exact nature of the support that was required. Over time, the ideas become more focused and clear and resulted in a sales support vision that was taken to the planning meetings. It has already been explained how the shared domain knowledge within IT and a high level of IT implementation success influenced the communications process, so they too must be seen to influence long-term alignment, albeit indirectly.

Therefore, for BU 1, all constructs in the model played a part, but the ongoing communications between IT people and agency people generated and sustained the shared IT vision, our measure for long-term alignment.

Causal analysis of Business Unit 4

Within BU 4 there were silos, in which each line executive was working in isolation and the IT director had no strong connection with any of them. The IT director's previous experience was centered on the mainframe, whereas the line executives primarily used PC systems to analyze trading and investment data. The IT and business executives were worlds apart. The most recent IT strategic plan, formulated three years before the interviews, was never circulated to management and only one of the four projects suggested in it was actually pursued. They had not identified a long-term business direction, so a consultant had been hired to create one.

It was no surprise to find a lack of vision about how IT might leverage the business. The findings suggested that executives within BU 4 were quite uninformed about how IT could be used to improve their results. Their current strategic business planning initiative did not include IT. The conclusion reached was that this attitude, at least in part, was the result of a very low level of shared domain knowledge and low levels of communication between IT and line management. They had no way to get internal advice about IT and no respect for an IT director who did not understand their business.

Business Unit 5: an unusual leader

Two other units, BU 5 and BU 6, are interesting in that they seem to refute most of the assumptions inherent in the model. In BU 5, most of the factors are rated only moderate; however, the business unit was rated as having a high level of long-term alignment. In BU 6, most of the factors were rated as being high or moderate, however, the business unit was rated as having no vision. The analysis centered on two questions: (1) were any constructs in the original model instrumental in explaining the results and (2) were there other constructs that might help in understanding the apparent anomalies?

In BU 5, there was a high level of agreement among executives about the role that IT could play in their future. They needed better access to internal data to support marketing decisions such as pricing and product features. However, the rating of the model elements (moderate levels of IT success, communication, and connections in planning) make this high level of IT vision interesting. In analyzing the causal links within BU 5, it was found that the influence of the head of the business unit was stronger than the more ‘institutional’ factors represented in the model.

This senior vice president had a Master's degree in Computer Science and was, by far, the most IT-experienced senior executive within the sample of ten business units. Because of his strong computing background, he (unlike virtually all of his peers in the business units) was willing to set a direction for the IT part of the business and was very clear about how IT should be used. Because of the power of his position in the organization and the level of his expertise, his views prevailed and required few formal communication channels or planning processes to entrench them as the dominant vision. Therefore, an unusual level of shared domain knowledge (primarily in the senior line manager, although it was also present in the IT manager) seemed to be the most important construct in explaining long-term alignment in BU 5.

Business Unit 6: no long-term business direction

In BU 6, there was no agreement whatsoever about the future direction for IT. This was especially interesting because IT had made this business unit a market leader in the early 1980s. They had created an IT system to support their insurance product and this system had helped them capture over 60% of the Canadian market. Unfortunately, the makeup of the industry had changed since then and several very strong competitors had copied the software, given better price breaks to the customers, and taken away half of the market. Their attempt to regain competitive advantage through improved software had floundered because of a combination of poor project management and a low level of customer adoption.

When the BU 6 executives were interviewed, they were suffering a crisis of confidence. Not only had their market share been slashed by competitors but their strategic weapon, information technology, had also failed to provide the promise of recovery.

So, although BU 6 had created strong communication links between IT and senior line managers, and their IT and business planning was highly integrated, these management processes had not yet shown them a way out of their strategic dilemma. The analysis concluded that low levels of success in their IT implementation, coupled with a lack of long-term business direction, were the constructs which most strongly influenced their lack of IT vision.

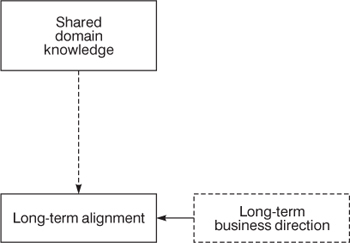

Conclusion: long-term alignment

When the data were analyzed for each business unit within Table 10.7, the strongest resulting explanatory model contained one influential element from the model: shared domain knowledge. In addition, long-term business direction was added to the model as a necessary antecedent for long-term alignment. Although communication was seen to be influential in BU 1, 3 and 4, there was less support for it in other business units and it was not included in the model.

In Figure 10.4, a heavy dotted line has been drawn between shared domain knowledge and long-term alignment. The thickness of the line represents the strength of the relationship, the dotted format represents the indirect nature of the relationship. Although the belief is that there are intervening factors between these two constructs, they were not discovered in this research. There is no strong evidence that a vision for IT is created through the communication events tracked. In addition, no evidence could be found that planning processes actually contributed to the creation of an IT vision. The planning processes seemed to be useful only for validation and funding once the vision had been created.

Figure 10.4 Explanatory model for long-term alignment

Conclusions

Overall, substantial parts of the research model were corroborated for short-term alignment, one element proved to be influential in creating long-term alignment, and one new construct, existence of a business direction, emerged from the data. In the next section, the findings are related back to previous research and new propositions are suggested. A discussion of the limitations of the study and implications for future research follows. The chapter concludes with recommendations for practitioners.

Summary of results regarding short- and long-term alignment

In general, it was relatively easy to discover the influence of constructs on the creation of short-term alignment. Organizational stories, minutes from meetings, respondents’ explanations, and the researchers’ interpretations often converged to create plausible causal explanations. The origin of the short-term business or IT objectives could be traced and the meetings at which they were discussed by IT and business executive identified. How the level of shared domain knowledge had influenced communication and the understanding that IT and business executives displayed toward each other's objectives, could also be explained.

Such linkages were not apparent when it came to explaining the presence or absence of long-term alignment. The one construct that seemed to predict long-term alignment was shared domain knowledge, but a causal explanation for its influence was not found. One significant issue was that how or when IT visions were created could not be found. Actions by individuals seemed to strongly influence the creation and dissemination of vision, and vision itself was difficult for respondents to articulate, and difficult to measure. Apart from measurement problems, it is possible that creation of a shared, long-term vision for IT would be better explained with process analysis rather than factor models. The suspicion is that there are several paths to a shared IT vision and that a longitudinal, ethnographic study is required to illuminate the antecedents of this construct.

The relationships between findings and prior empirical work are shown in Table 10.8.

One observation was that IT implementation success cannot be used to predict the level of communication or connections in planning without taking into account the level of shared domain knowledge. A high level of shared domain knowledge may moderate the expected negative influence of a low level of IT implementation success on the other two factors.

In simpler language, managers within a business unit with high levels of shared domain knowledge understand and respect each others’ contribution and trust that each is giving their best effort. Even in the presence of a seriously derailed major IT project, these units may exhibit high levels of communication and short-term alignment. In units without high levels of shared domain knowledge, failed or failing IT projects result in finger-pointing, reduced levels of communication, and low levels of short-term alignment.

Another conclusion was that planning practices are not predicted by intraunit factors, such as shared domain knowledge or IT implementation success. They seem to be influenced by macro organizational level policies and, in some cases by senior individuals within business units. Business and IT planning processes seem to be events at which business direction is set, IT plans are discussed, and budgets are ratified. While these events influence short-term alignment by getting the short-term objectives understood by all, and funded, they do not seem to play a role in the creation of an IT vision. Although a high level of shared domain knowledge in organizations with long-term alignment was expected, there may be other, as yet unknown, factors that influence this outcome. When we as researchers understand more clearly how IT visions are created, these other factors could likely be identified.

Limitations and ideas for future research

There were several measurement problems associated with this study, the most notable being the measurement of connections in planning and IT vision. These issues are discussed below as well as the issue of generalizability and future research investigating shared domain knowledge. In addition, future researchers should investigate the notions of ‘trust’ and ‘commitment’ that this study was unable to pursue.

Connections between business and IT planning