19 Information Technology and

Customer Service

Redesigning the customer

support process for the

electronic economy: insights

from storage dimensions

O. A. El Sawy and G. Bowles

This chapter provides insights for redesigning IT-enabled customer support processes to meet the demanding requirements of the emerging electronic economy in which fast response, shared knowledge creation, and internetworked technologies are the dynamic enables of success. The chapter describes the implementation of the TechConnect support system at Storage Dimensions, a manufacturer of high-availability computer storage system products. TechConnect is a unique IT infrastructure for problem resolution that includes a customer support knowledge base whose structure is dynamically updated based on adaptive learning through customer interactions. The chapter assesses the impacts of TechConnect and its value in creating a learning organization. It then draws insights for redesigning knowledge-creating customer support processes for the business conditions of the electronic economy.

Effective customer support in the electronic economy

Effective customer support and service has become a strategic imperative. Whether a company is in manufacturing or in services, what is increasingly making a competitive difference is the customer support and service that is built into and around the product, rather than just the quality of the product (cf. Henkoff, 1994). Customer intimacy is becoming an increasingly acknowledged strategic posture (Treacy and Wiersema, 1995) and the traditional distinction between products and services is becoming increasingly irrelevant (Haeckel, 1994). Companies are moving closer to their customers, expending more effort in finding new ways to create value for their customers, and transforming the customer relationship into one of solution finding and partnering rather than one of selling and order taking. Customer support and service comprises the way that a product is delivered, bundled, explained, billed, installed, repaired, renewed – and redesigned. As a growing envelope that can manage and grow successful long-term customer relationships, customer support and service is becoming one of the most critical core business processes.

The emphasis on customer support and service needs are driving IS priorities more than ever before. There has been research work on measures of service quality for information system effectiveness (Pitt et al., 1995). Furthermore, results of the annual surveys of critical issues of IS management conducted by systems integrator Computer Sciences Corporation show that ‘connecting to customers and suppliers’ has jumped from sixteenth place in 1994 to seventh place in 1995 and 1996 (Savola, 1996). The 1996 survey also revealed that the corporate goal with which IS is aligning itself most is learning about and fulfilling customer needs more effectively, and that applications to support customer service is the number one focus of current systems development efforts (60% of 350 IS executive respondents). Similarly, a 1995 survey by Information Week (Evans, 1996) to identify the top criteria by which organizations evaluate the performance of IS professionals showed that two of the top five criteria centered around customer support and service. The two criteria were the ability to use IT effectively to improve customer service (76% of respondents) and how well they deployed IT to meets the needs of customers outside the organization (67% of all respondents).

However, there is more to this than just bringing more IT to customer support and service. The increased focus on customer support is taking place in a business environment that is characterized by unprecedented speed, rapid knowledge creation, increasing complexity, and spreading electronic networks: we are experiencing the emergence of the electronic economy. This new business environment breeds many more complex products with shorter life-cycles, and these products are used in customer contexts that are also complex and fast-moving. Customer support in such environments is much more demanding – especially in business-to-business situations – and that requires:

• Much faster response to resolving customer queries and problems as the business tempo escalates

• Smarter and faster ways of creating, capturing, synthesizing, sharing, and accessing knowledge about complex products and services

• More dynamic support for – and faster learning about – products that are frequently morphed due to rapid product innovation and dramatically shorter product life-cycles

• More collaborative problem-solving with other (possibly competing) companies as products from multiple vendors increasingly have to work in concert

• Taking advantage of new electronic channels and open networks for communicating and collaborating with customers and

• More fail-safe customer support as it becomes most critical to the customer.

Given these stringent requirements, how can customer support processes be transformed and IT-enabled to be effective in this new electronic economy? That is the challenge this chapter addresses.

The evolution of customer support for complex products

Customer support traces its origins to the 1850s when the Singer Sewing Machine company set up a program that used trained women to teach buyers how to use the sewing machine (Lele and Sheth, 1987). Traditionally, customer support has referred to after-sales support, which consists of all the activities that help increase customer satisfaction after they have purchased a product and started to use it. The marketing literature (cf. Lele and Sheth, 1987) has differentiated between specific support services and feedback and restitution. Support services refer to activities such as parts and service, warranty claims, customer assistance and training, technician training, and occasionally trading-in of older equipment. Feedback and restitution refers to activities such as complaint handing, returns and refunds, and dispute resolution. As manufacturers started to compete by bundling services with products (cf. Chase and Garvin, 1989; Shostack, 1977) the scope of customer service and support for products has expanded cross-functionally to include expert help from the manufacturing, engineering, and R&D functions. More recently, as long term customer relationships and partnering with customers have become very important (cf. Henkoff, 1994) the notion of customer support has expanded beyond ‘after-sales’ and has colored the whole way that customer service is provided. While, the terms service and support are loosely used interchangeably in some contexts, they are not the same. Customer support has a long term partnering flavor that signifies that the supplier wants to help the customer do their job effectively, and in this age of interdependence and alliances it seems to be a more apt term for the bundle of activities that comprise it.

Customer support is more critical and difficult for high technology complex products, especially with the breakneck speed in new product development for those products. Many customer support innovations and strategies in the last decade have originated from the computer and telecommunications industry. These include automated help desks, toll-free hot-lines, computer bulletin board systems, 7×24 service, remote online troubleshooting, and, most recently, the use of the Internet. As organizations have become critically dependent on information technologies and telecommunication networks for the operations of their business, so has the criticality of response time in supporting those products and services – and it has risen to unprecedented levels. The cost of providing effective customer support has also risen more than proportionately. The high technology industry has sought solutions that may provide ideas for other industries.

In order to improve overall service levels and reduce overall costs, the information technology industry has adopted a hybrid model for customer support (Entex, 1994). This includes having personnel on-site at major customer accounts (what IBM has been traditionally known for), using third party resellers or other vendors who can provide localized customer support for smaller accounts and consumers, and providing high-tech long-distance remote support through a centralized pool of talent whether in-house or through an external service (very common in commodity and low margin items such as PC hardware and software). Each of these options has a different cost structure and service advantage. Direct on-site support is expensive but provides superior service. Going through resellers requires heavy investments in training and qualification to assure good service. Remote high-tech support is a challenge for complex products and can be very impersonal if not very carefully managed. Different vendors in different market segments have different hybrid blends depending on their support strategy.

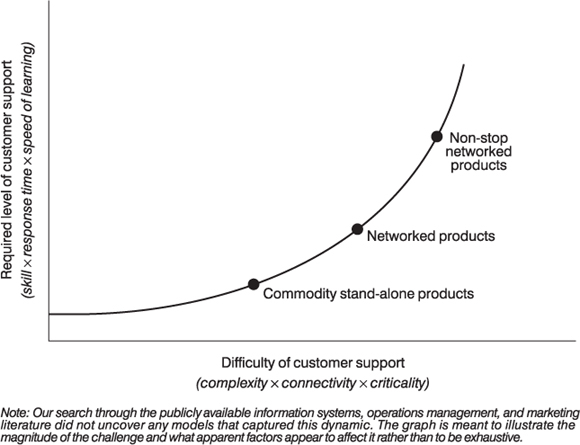

These options are further challenged when products interact with other vendor products, response time is critical, and the stakes in downtime are very high. Figure 19.1 illustrates how the required customer support level rises very quickly when there is an increase in the combination of complexity and connectivity of the product and its criticality to customer operations. For high-end products that are in non-stop heterogeneous networked environments where down-time is prohibitively expensive for the customer, the requisite level of customer support rises exponentially. It requires very fast response time, highly skilled personnel, and an ability for customer support personnel to learn very quickly about product innovations and quirks in their own products and those of other vendors’ (that their product interacts with). That quick learning requires a radical rethinking about how learning occurs during the customer support process. The challenge is to find a way to very quickly capture and disseminate new learning around the customer support process through all the participants that come into contact with it in a simple and cost effective way.

This challenge was examined in the context of the customer support process at Storage Dimensions, a manufacturer of high-availability computer storage system products. Moreover, we believe that the lessons of this experience provide insights for rethinking the customer support process in all industries as the electronic economy makes such customer support levels more the rule than the exception.

Figure 19.1 Rising customer support levels for complex products

The customer support challenge at Storage Dimensions

Storage Dimensions is a vendor of high-availability disk and tape storage for client/server environments. It was founded in 1985 in the heart of Silicon Valley in Milpitas, California, and went public in March 1997. Its 1996 sales were $72 million. The company designs, manufactures, markets, and support hardware/software products that provide open systems storage solutions for mission-critical enterprise applications. Its high-end storage solutions are targeted to organizations with enterprise-wide client/server networks that must keep mission-critical data protected and available 24 hours a day. The company's customer base is mainly Fortune 1000 companies in information-intensive industries that live and die by their data. These include airlines, banking, finance, insurance, retail, utilities, and government agencies. Storage Dimensions products are sold through distributors and resellers in the USA, Europe, and the Pacific Rim. The company also has a direct sales force to more effectively serve its key vertical market customers. More detailed information about the company and its products can be found at www.storagedimensions.com.

Storage Dimensions’ products fall into three main categories: high-availability RAID disk storage systems, high capacity tape backup systems, and network storage management software for multi-server networks. RAID (Redundant Array of Independent Disks) is a fault-tolerant disk subsystem architecture that provides protection against data loss and system interruption and also provides improved data transfer/access rates for large databases. This protection ranges from simply mirroring data on duplicate drives to breaking data into pieces and ‘striping’ it across an array of three or more disks; if one drive goes down, the controller instantly reconstructs the lost data and rebuilds it on a spare drive. Other features include a combination of redundant hot-swap hot-spare power supplies, fans, and disk drive components to ensure non-stop operation and continuous access to data.

Following a 1992 buyout from Maxtor, company management refocused Storage Dimensions to become a higher-end and faster-response industry player. It was clear that exceptional customer support would be essential to success, and a customer-support-focused corporate strategy was put in place. The customer support process was reexamined and it was apparent that it was becoming inadequate for the growing customer base and expanding product line. Furthermore, with increased globalization the customers were dispersed geographically and in different time zones. The customer support process was too slow (as much as two to three hours to return a phone call in some circumstances), too haphazard (no organized online knowledge base for repeat problem solutions), too expensive (repeat problems frequently escalated to development engineers, long training periods), and very stressful to both support personnel (overloaded) and managers (little visibility for the what, who, why, when). Top management saw the need for a radical solution.

Given the mission-critical nature of its customers’ network environments, the company expended much effort in providing exceptional customer support. It differentiated itself in the market by helping customers minimize their total life-cycle cost of ownership for network storage in the context of mission-critical applications. A storage system's total life-cycle cost-ofownership is much more than the purchase price. Service, support, and downtime for RAID storage systems account for 80% of the total cost over the life of the system as per a Gartner Group study – and downtime is especially critical to customers. A Computer Reseller News/Gallup Organization 1994 study found that hourly losses due to network downtime in Fortune 1000 companies were $3,000 to $5,000 per hour (median), could often be $10,000, and sometimes $100,000 or more (6% of companies). Storage Dimensions instituted several customer support programs and innovations to enhance this lower total life-cycle cost-of-ownership customer support strategy. [For additional information on Storage Dimensions, see Chabrow, 1995.] One key element of that strategy was TechConnect, an online technical support system. The development of TechConnect is described in the next section.

The development of the TechConnect support system

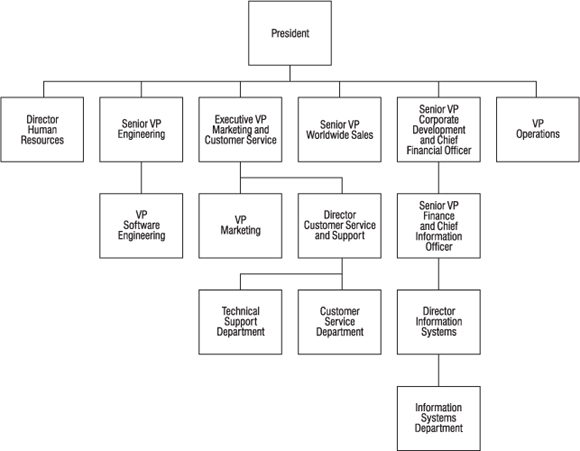

As the customer support process was being reexamined in mid-1992, it became apparent to the management team that an IT-enabled solution with an artificial intelligence component had to be part of the remedy. They put their commitment behind it and a project was initiated. The core management team for the project consisted of the executive VP for marketing and customer service (who was also the project sponsor), the director of customer service and support, and the director of information systems (Figure 19.2 shows the organization chart). In addition, a cross-functional task force was formed consisting of three people: one from the customer support group, one from the IS group, and one from engineering. Together, and with input from both customers and others in the company, the management team and the task force came up with a list of the top operational objectives (see Table 19.1) and key technical usability requirements (see Table 19.2) for what they generically referred to then as the customer support management system. They then searched the market for software packages that could help meet those requirements.

Figure 19.2 Organization chart for Storage Dimensions

Table 19.1 Top 10 operational objectives of customer support management system in mid-1992

1 |

Provide consistent, accurate responses to customer inquiries |

2 |

Document and track all known problems and proven solutions |

3 |

Create centralized sources of information about customers, known problems, solutions |

4 |

Assist in developing solutions to new problems |

5 |

Create a closed loop escalation process |

6 |

Promote cross-training of support staff |

7 |

Provide remote access for customers of problem solutions |

8 |

Improve call tracking and problem reporting |

9 |

Improve accountability and responsibility with clear audit trails |

10 |

Improve productivity of customer support staff |

Table 19.2 Technical usability requirements of customer support management system in mid-1992

IT Infrastructural/compatibility requirements |

|

1 |

Multi-user, runs off current Ethernet network lines |

2 |

Works under Microsoft Windows with a GUI interface |

3 |

Dial-in capability for remote user access |

4 |

Provides initial access for 25 users, expandable to 50 within one year |

5 |

Must interface with cc:Mail for notification purposes |

6 |

Must have data import/export capability |

Usability Requirements |

|

1 |

Call tracking capability |

2 |

Problem/solution tracking capability |

3 |

Keyword search for problems/solutions |

4 |

Must have a method for assisting technical support staff with answering calls (Al or other) |

5 |

Must have a report generator with user-definable reports without generating programming code or a script |

6 |

Ability to create and define call queues |

7 |

Have at least five user-definable fields |

8 |

Have automated call escalation process |

9 |

Must have a closed loop problem solving process |

10 |

Provides call audit trail |

11 |

Tracks and reports customer configuration data |

The search included various types of artificial intelligence shells, database managers, call management packages, and help desk software – most of which were not the least bit suitable and were quickly eliminated. Only four packages in the help desk software category came close, and these were evaluated in detail. These help desk software packages were not an off-theshelf fit to the application context. First, the approaches of the packages and vendors were geared mostly to internal help desks rather than external customer support with different customer types. Second, the knowledge capture/update and keyword search capabilities (if any) were too primitive for complex products that changed quickly and had interactions with other vendors’ products. Third, Storage Dimensions had a fairly sophisticated client/server network, and it wanted to link the customer support system to its e-mail and to its internal information systems and databases in other functional areas. As the help desk software vendors themselves acknowledged at the time, this would be a stretch.

The comparative analysis among the four help desk software packages was made based on how the software features fit the operational requirements. The Apriori GT help desk software from Answer Systems (since 1995 a part of Platinum Technology Inc.) was selected mainly based on its unique ‘bubbleup’ technique that could prioritize likely problem solutions (discussed in more detail later in this section), its good incident management capabilities, its good reporting capabilities, and its technical compatibility with Storage Dimensions’ client/server network infrastructure and the Windows graphical user interface. Other Apriori GT capabilities at the time included call tracking, incident escalation, various search and retrieval features, custom notification and routing, e-mail and fax integration, accountability features, and tailorability for application integration.

While no programming changes would be made to the source code, there was much work to be done in structuring Apriori GT to fit the complexity of the Storage Dimensions environment and linking it (through Perl scripts and macros) to the internal information system infrastructure and e-mail. For the next 90 days the task force worked together with the software vendor to install, customize, script, and test the customer support application. Simultaneously, the customer support process and the way it was managed was being reengineered to take advantage of this new technology. Much input was sought and enthusiastically received at that stage from various parts of the company, and a pilot was run with selected customers. Fortunately, implementation was successful both technically and organizationally. Tech-Connect was online in late 1992.

The TechConnect system was set up on a Sun Sparc 670 MP server and cost $160,000 for hardware and software. It costs $15,000 to maintain per year.

The cost justification for TechConnect was not difficult based on out-ofpocket expenses. In the first year alone the reduced call-backs (due to higher problem resolution rate on first customer call) saved about $70,000 in long distance phone bills. In addition, the productivity gains obviated the need to hire more technical support engineers to handle the growing customer support load, saving another estimated $150,000.

The new IT-enabled customer support process

TechConnect enabled the redesign of the customer support process such that it could be more effective and better managed. Some key aspects of how this new online customer support process was managed follow.

• Improved escalation paths for problem management: A simplified diagram of the three-level escalation sequence is shown in Figure 19.3. After dispatch, the customer call goes to a level 1 technical support engineer. He/she tries to resolve the problem through an on-line TechConnect solution document. If it includes a request for material authorization, then an appropriate customer service representative is notified through TechConnect. If the problem is not resolved at level 1, it is automatically escalated and queued (path depends on the operating system used by the customer's client/server network hardware) to a level 2 applications engineer who is more skilled and who investigates it thoroughly. If the applications engineer is unable to resolve it, then it is automatically escalated to the problem tracking request (PTR) manager who verifies the problem and must decide whether to escalate it to a development engineer.

Figure 19.3 Escalation sequence in customer support process

• Closed loop problem resolution: As the incident moves along the escalation path, both the caller and the customer support staff (and manager) always know who has the incident and what its status is. The process also ensures that the customer is informed in a timely manner. TechConnect keeps track of all the information related to the incident and stores it in the TechConnect database.

• Analysis and reporting capabilities: TechConnect provides a multitude of management and activity reports that help manage the customer support process and identify bottlenecks. It is possible to automatically flag unusual events and for customer support staff to spend more time on proactive rather than reactive customer support.

• Automatic cross-triggering capabilities: TechConnect is integrated into the Storage Dimensions network of information systems to automatically flag other business areas or information systems via e-mail based on problem incidents. This facilitates cross-functional coordination between customer support and other departments.

• Amplified shared knowledge creation: The intensity of shared knowledge creation through customer interactions around the customer support process is greatly amplified through TechConnect. The continuous production of online solution documents steadily creates a valuable knowledge base that is accessible to all: everyone can be an expert, and everyone can contribute to the learning. That transforms the way that the customer support process is carried out and managed, as does its knowledge-creating capacity. That critical aspect is discussed in more detail in the next section of the chapter.

With the use of the TechConnect system and a transformed customer support process, the customer support department has remained at the same size despite increasing sales volume. The group consists of eight technical support engineers, three applications engineers, and one manager. They work a basic 11-hour shift between them and also have a 24 hour on-call system.

TechConnect as an adaptive learning IT infrastructure

The TechConnect system is based on a knowledge base software architecture that adaptively learns through its interactions with users. It is based on a unique software-based problem resolution architecture (patented in 1995 by Answer Systems) that links problems, symptoms, and solutions in a document database. All problems or issues are analyzed through incident reports, and resolutions are fed back into the online knowledge base in the form of solution documents. The software is able to link one master solution or solution-inprogress with variants of multiple symptoms. This unique many-to-one relationship allows the help desk to update the solution in a single place in the knowledge base and communicate meaningful updates to users automatically.

The way that the TechConnect knowledge base learns is through the very well-structured dynamic feedback loops that are managed by the problem resolution architecture. As problems are analyzed and resolved by technical support specialists, development engineers, and customers, the results are integrated into the knowledge base as solution documents, and new knowledge is created and synthesized (see Figure 19.4). As a result, solutions are consistent and readily available to support specialists and customers alike. Solutions are ‘fresh’ (up-to-date), accurate, and based on the latest experience of customers (200 new data points per week). At this writing, support specialists and customers have access to information from over 35,000 relevant incidents. In total, 1,700 solution documents are currently available electronically. Because 80% of incoming calls are repeat problems, existing solution documents often provide resolutions within minutes.

Another key feature of the TechConnect system is the Bubble-Up solution management technology (see box below) that enables the TechConnect knowledge base to adaptively learn through its interaction with users. It automatically prioritizes solution documents based on ‘usefulness/frequency of use’ in resolving specific problems, and the higher priority ones rise to the top of the list. This helps less experienced inquirers to see the most useful solutions and speeds up problem resolution. The Bubble-Up process also adaptively changes the structure of the knowledge base and adapts it continuously to new knowledge.

Figure 19.4 TechConnect's dynamic feedback loop for knowledge creation

In combination, the problem resolution architecture and the Bubble-Up software make it possible for the knowledge base to change its structure dynamically ‘on-the-fly’ as it gains new knowledge from those who interact with it. TechConnect can learn quickly from anyone who interacts with it: customer support specialists, development engineers, and customers. Furthermore, the knowledge is always fresh and usefully organized for rapid problem resolution for less-experienced users.

The TechConnect support system allows self-help by customers. It can be directly accessed by customers 24 hours a day through e-mail or through the Internet via the Storage Dimensions Website (http:storagedimensions/support/techsupport/). To access the knowledge base via the Internet self-help route or e-mail, customers complete a TechConnect search request form that includes symptom identifiers. Within two minutes, TechConnect automatically sends back a related list of solution documents from which to choose. Thus, through an e-mail or web page request, TechConnect is able to search for solutions in the knowledge base, select and rank order them based on usefulness, and post them back to the web page. While technically possible, the structure of the knowledge base is not updated on-the-fly through the self-help route in order to protect the integrity of the database from spurious information. New knowledge from self-help incidents are first checked by technical support specialists before being submitted as updates.

What is Bubble-Up™?

Bubble-Up is a patented problem resolution technology that is embedded in the Apriori product. It enables an indexing scheme and intelligent filter that causes the most-used solution documents to rise to the surface of the volume of solution documents that are stored in a problem resolution knowledge base. The index structure of the knowledge base has multiple roots and is not strictly hierarchical. Moreover, it uses a proprietary algorithm to automatically modify the structure of the knowledge tree based on ‘most-used’ knowledge elements in the tree. ‘Mostused’ is based on a statistical weighting of both the actual usefulness and popularity of a solution document in solving a problem rather than just access (i.e., incorporates a voting heuristic). It can do this at any level of the index structure thus enabling selective filtering. A flowchart illustrating how the Bubble procedure works internally is shown in Figure 19.5. How it affects TechConnect from a user perspective is explained through an example in the next section of the chapter.

As new solution documents are created and/or their usefulness in solving problems changes (through user voting when accessed) the knowledge base is able to adaptively learn and automatically change its structure without any programming, and in a way that is transparent to the user. It is thus able to self-modify through use and learn as new problems, solutions-in-process, or solutions are added.

Bubble-Up was patented by Answer Systems in 1994. It won the 1995 Harold Short Jr. Innovations in Service Awards that recognizes tools and services that have a far reaching effect on service delivery.

Figure 19.5 Flowchart of Bubble-Up procedure. (Adapted from Answer Systems)

The TechConnect knowledge base provides detailed information on installation, compatibility, troubleshooting, and support for Storage Dimensions’ systems, as well as related products from other vendors (servers or operating systems or backup software). The customer support web page also has hot links to those vendors. Of course, for such a system to work effectively, it must be integrated into a very well-structured organizational customer support process that is well-managed. That was a crucial consideration in the redesign of the customer support process at Storage Dimensions. The tightness of integration between the use of TechConnect and management of the customer support process is perhaps best shown through an example, presented in the next section.

How TechConnect drives the knowledge-creating customer support process

When a customer calls on the phone for support, a Storage Dimensions frontline technical support engineer sitting at a TechConnect screen asks questions about system configuration (enclosure type, operating system, type of drive, etc.) and an incident is created. Based on the customer's reported problem, the technical support engineer uses symptom words to search for an existing problem/solution document. Each solution document has symptom words associated with it that are assigned when the solution document is created or modified, and they are added to the master symptom list. On the TechConnect screen captured in Figure 19.6, the word ‘hang’ is selected (note asterisk next to it) from the master symptom list as one of the symptom words. An ‘Auto Search’ will look for any solution documents that are linked to the symptom words. A ‘Manual Search’ will do the same but will also prompt the user to iteratively reduce the number of symptom words, if no documents are found in the initial search with all the symptom words.

Figure 19.6 TechConnect screen for symptom search

Figure 19.7 TechConnect screen with list of possible problem/solution documents

If the simple indexed search does not locate any solution documents, then a natural language text retrieval search for the symptom words is attempted for all documents in the knowledge base, even documents not contained within the Apriori database (through icon circled in Figure 19.7). This type of search takes more machine time than an indexed symptom word search.

Based on the symptom words selected, a listing of problem/solution documents will be listed (see Figure 19.7) and then the technical support engineer can view them to see if any of them apply.

If a solution document cannot be found based on symptom words, the technical support engineer will then try to search the index structure of documents using TechConnect's Bubble-Up feature. By clicking on the Bubble-Up icon (circled under ‘Reports’ in Figure 19.8 the technical support engineer will see a hierarchical index structure as shown in the top half of the screen in Figure 19.8. The bottom half of the screen shows the top 12 solution documents for all of the available indexes based (and rank-ordered) on the effectiveness of each solution document. By clicking on any of the index buttons (BBS, Software, Hardware, etc.) the user drills down deeper into the index. For example, clicking on the ‘Hardware’ button will reveal the next index level (Computers, Drives, Tape Drives, etc.), and the top 12 documents for those index buttons will be listed. He/she can then start examining each solution document from the top of the list and clicking on the document they think is most relevant (this is a support system that supports the user's thinking, rather than replaces judgement).

As documents are read, the technical support engineer is prompted to vote on the usefulness of the document. They are requested to select between ‘not useful,’ ‘useful,’ and ‘solved incident.’ If either ‘useful’ or ‘solved incident’ is selected, then the document is moved up higher in the Bubble-Up list. If ‘solved incident’ is selected, then the customer's TechConnect account number becomes associated with the solution document so that any updates or modifications to the document will generate an automated notification to the customer.

If none of the documents provide a solution to the customer's issue, the technical support engineer will complete a ‘new problem’ report (by clicking on the ‘new problem’ icon circled under ‘Go To’ in Figure 19.8). The new problem report is generated whether the problem is resolved or not. If the problem was resolved, then the report will also describe the solution. If there is no resolution, then recommendations for a solution will be given (update manual, debug software, change hardware, etc.). If a specific index is not specified, then the new problem report will be assigned to the last index visited during the Bubble-Up search. The owner of that index (the applications engineer) will then be notified that a new problem has been submitted.

Figure 19.8 TechConnect Bubble-Up solution document listing

The applications engineer will then review the new problem and check that no problem/solution document or pending problem exists, that all information is present to replicate the issue if needed, and that all basic trouble shooting steps have been performed. If a solution was provided, the applications engineer will then verify the validity of the new problem report and edit it for clarity and effectiveness. It is at this time that the symptom words are assigned to the document. The document will then be marked with a status of ‘marketing review’ and the appropriate marketing product manager's e-mail address will be assigned to the document and they will be automatically notified that a new document has been created and is awaiting their review. Any comments or corrections are then forwarded back to the applications engineer to incorporate into the document. At that time, the document is set to the status of ‘Closed.’

If no solution was included with the problem report, the applications engineer will then try to resolve the issue by interfacing with engineering, or other departments as needed, or by replicating the problem by duplicating the installation as close as possible. If the problem is resolved by the applications engineer, the document will be set to a status of ‘marketing review’ and follow the process explained above. If the applications engineer is unable to resolve the issue or is able to verify a hardware or software issue that requires engineering or another department's effort or resources to resolve, the document is set to a status of (‘PTR (Open).’ PTR stands for Problem Tracking Report and means that an issue was not able to be resolved by the technical support department and requires resources from another department in the company. After an appropriate person is identified to follow through with resolving the PTR, their e-mail address is assigned to the PTR and they are automatically notified on a weekly basis until the PTR is resolved. They can submit comments back to the submitting applications engineer for incorporation into the comments area of the document. The information in the comments area on PTR documents are compiled on a weekly basis and posted for company-wide review. Once the PTR has been resolved, the applications engineer will complete the documentation and then set the document status to ‘marketing review’ and follow that process as described above.

There is also a procedure for solution document update. If a technical support engineer finds a document that is incorrect or outdated, or new information is discovered, he or she can attach comments to the document. The document owner will be automatically notified via e-mail that new comments have been posted for that particular document. The applications engineer will then review the comments to see if they are appropriate to be included into the document. After the comments have been added, the document goes through the same ‘marketing review’ process as described earlier. After the comments have been posted, any customer or technical support person on that document's ‘list’ will be automatically notified via e-mail that the document has been updated.

Assessing the impacts and value of the TechConnect system

The TechConnect customer support system has paid for itself many times over. As mentioned before, it paid for itself in its first year by virtue of cost savings alone. More importantly, it has driven the transformation of the customer support process, has enabled the integration of valuable customer input into other areas of the business, and has revealed the enormous potential of an innovative type of IT infrastructure that enhances quick organizational learning as the environment changes. The TechConnect knowledge base and the process routes around it are now a growing part of Storage Dimensions’ intellectual capital. It is not an overstatement to say that the TechConnect system has had strategic impacts on Storage Dimensions and has been instrumental in advantageously positioning the company for the electronic economy.

For purposes of exposition and assessment, the impacts have been divided into three categories: first order direct impacts on transforming the customer support process itself, second order impacts related to integrating customer input into other business areas, and third order indirect impacts related to building an IT infrastructure for the electronic economy.

First order direct impacts: transforming the customer support process

• Faster customer response: Average time to respond to a customer problem report is now 15 minutes, after being as much as two to three hours in some cases prior to TechConnect. Problem resolution time has dropped from an estimated four-hour average to a measured 50-minute average: 60% of all problems are resolved within 30 minutes and 70% within an hour. Also, about 20% of incidents are now handled by the self-help route through 7×24 Internet/e-mail with instant response to queries; 80% of these self-help incidents are resolved on the first try through online solution documents.

• Accurate, consistent, and accountable problem resolution: Due to the real-time currency of the TechConnect knowledge base and rank ordering of solution documents, repetitive problems are solved correctly and at the first level every time, no matter what the skill level of the technical support engineer. If escalation occurs on a difficult new problem, then both the customer and Storage Dimensions know the progress of the resolution at all times. It is impossible to be unaccountable.

• Cost-effective problem resolution: Due to orderly TechConnect escalation processes, valuable development engineer time is conserved. Currently, 67% of technical failure incidents are resolved at level 1, also conserving the time of application engineers. The remaining 33% are handled by level 2 applications engineers who thoroughly research the problem and solve it about 80% of the time. The remaining 20% (7% of the total) are escalated through the customer support manager to a development engineer. While a 33% escalation ratio may appear high in comparison to traditional internal help desks, it is actually low given the complexity of products and given that related server technology changes every 90 days (paced by Intel's synchronized 90-day release schedule for microprocessors).

• Leadership in cross-vendor troubleshooting: Most of the difficult technical problems in client/server environments are related to compatibility issues and integration across storage and server products made by different vendors. Storage Dimensions’ capability for cross-vendor troubleshooting has been greatly amplified through TechConnect and has eliminated many hours of finger-pointing. There is no quantitative data, but there are anecdotes about how Storage Dimensions was able to provide a solution document to another vendor's compatibility problem and verify it before the other vendor's technical support person even arrived to the customer site. Such incidents have helped establish a reputation for the company as a customer support leader.

• Vigilant and proactive management of customer support process: TechConnect collects much data related to problem reports, activity levels, and customers. It easily provides ad hoc management reports for spotting process problems. It flags problems that require quick management attention and alerts of longer term capacity and service-level issues. The customer support process now has a greater proactive component based on such flagging. A telling (but unscientific) measure of this impact is the director of customer support's likening the discovery of TechConnect's management capabilities to uncovering the Holy Grail – even giving the system the nickname ‘Galahad.’

• More learningful customer support staff: The word ‘learningful’ is concocted, but it aptly captures the spirit of what is being articulated. TechConnect enables staff to be more learningful in that they build on each other's knowledge and on that of more experienced senior colleagues and smart customers. Each and every customer support staff person has access to expert problem solutions through TechConnect – no matter what his or her current expertise level is. Similarly, each customer support person contributes to the knowledge base. The systematic structure through which TechConnect directs the problem resolution process has also sharpened problem solving skills and diagnostic logic. This has upped the general skill level of the group as well as helped new hires ramp up their skills more quickly.

• More learningful customer support process: TechConnect has analysis capabilities that have enabled staff to uncover patterns and take proactive action for further prevention. This information is also fed back to other areas of the company depending on where the action is needed to be taken. It has ranged from changing a confusing paragraph on a page in an installation manual to a major redesign of a product component. Over three years, the number of incidents has dropped from 7,283 incidents per quarter in early 1993 to 1,715 incidents per quarter in early 1996 (see Figure 19.9). Even as a percentage of installed base, incidents have dropped from 1.45% to 0.49%.

In combination, these direct impacts and a qualitatively transformed customer support process translate to more satisfied customers. They also translate to more satisfied customer support staff. The staff (especially the junior staff) appreciate the positive feedback from being able to resolve problems quickly and the clear systematic guidance for the process that TechConnect provides. The turnover rate has dropped by about 50% in the last four years.

Second order impacts: integrating customer input into other business areas

The changes in the customer support process have also had impacts beyond its own confines in that customer input has been integrated into other business areas of the company. This has often been facilitated by TechConnect's ‘trigger’ feature that automatically triggers e-mail to other departments in the company depending on how questions are answered in a problem report. Examples of such second order impacts include:

• Product improvements: The number of incidents has decreased (see Figure 19.9) partly because of product improvements triggered through TechConnect. This has also provided valuable information to better track new products as they are introduced and on more than one occasion has helped to catch repetitive problems quickly. Proactive tracking of evaluation units at customer sites is now routinely done and the conversion rate (the conversion of a unit from evaluation to a sale) has increased by 30% since the use of TechConnect for that activity. This has fostered an appreciation of TechConnect by engineering.

• Sales lead triggers and marketing support: As TechConnect keeps a record of the nature of customer inquiries, through the ‘trigger’ feature it has become automatic to pass on any sale leads as well as provide new knowledge for marketing strategy.

Figure 19.9 Change in number of incidents on a quarterly basis

• Global expansion strategy support: TechConnect allows customer support to be easily administered online from one centralized location in Milpitas. As Storage Dimensions continues its global expansion, that will make it possible for it to provide customer support in any remote location around the world without substantially increasing costs or sacrificing the level of support.

• Discovering the potential of customer support as a revenue-generating business process: The company has not yet fully examined how to convert their customer support savvy into a direct source of revenue, although their expertise with solving other vendors’ compatibility problems is a source of know-how that could generate revenue. The challenge lies in taking advantage of it without jeopardizing the collaborative cross-vendor problem-solving that Storage Dimensions has sought to nurture.

Third order indirect impacts: building an IT infrastructure for the electronic economy

TechConnect has also had some broader indirect effects on the organizational vision of the company as a whole and its positioning for the emerging electronic economy. While perhaps more difficult to measure, these impacts may be the most profound for Storage Dimensions in the long run and are shaping the challenge that lies ahead.

• Finding an IT infrastructure that learns quickly: Somewhat serendipitously, Storage Dimensions has discovered an adaptive learning IT infrastructure that could be applied to the company as a whole. Management has now discovered a concrete, practical way to build a knowledge-creating company that learns quickly from its customers and partners. It is a somewhat unexpected revelation that perhaps a large portion of the ‘fresh’ intellectual capital of the company is being grown around and driven by the TechConnect support system. It is being extended to other parts of the company such as contracts and sales and some areas of engineering. It is becoming a possible foundation of an enterprise-wide IT platform suitable for the electronic economy where the capacity to learn faster, create knowledge quicker, and be nimbler is critical.

• Shaping the vision for use of Internet platforms: The TechConnect experience has illustrated early how useful the internet can be for self-help in customer support. Storage Dimensions is expanding internet use for tracking customer incidents in addition to telephone call tracking. It has also been developing software that monitors remote network storage at customer sites through the Internet (an extranet of sorts) and is tied to Storage Dimensions’ VantagePoint product. VantagePoint software monitors the condition and performance of disk storage systems across a multi-server network, collects the performance data, and reports it to a single management console. It currently has alerting capabilities that are tied to both pagers and e-mail. The new Internet monitoring capability allows for global monitoring of customer network storage by Storage Dimensions. The performance characteristics transmitted through the Internet are matched through the software to a database with site configurations (host bus, type of network adapters, type of server, etc.). With the help of VantagePoint, it comes up with an error code that provides diagnosis and early warning to the customer support personnel through e-mail – allowing them to take pre-emptive action. The augmented database with its automatic and continuous performance data capture allows Storage Dimensions to have robust failure predictions based on learning from its own database and to take necessary corrective or preventive action earlier. This capability is expected to be fully available for customers in late 1997.

• Developing customer-facing intranet applications: The success of the Internet interface as a standard ubiquitous accessible way to communicate with customers has prompted Storage Dimensions to develop Internet applications for other functions that interact frequently with customers. The company is currently implementing an intranet system with a standard browser coupled to a customized search engine for salespeople. Through this new application the approximately 25 Storage Dimensions salespeople will be able to gain access while on the road to the latest versions of sales-related documents (such as competitive information, benchmarking data, newsletters).

The challenge ahead

The project, like any successful IT-enabled organizational change effort, has had its share of typical technical, organizational, and managerial problems – and there were bumps and much learning along the way. However, none of those issues was major or unique enough to warrant the interest of readers. Nor can any advice be offered in that respect that is different from what is recommended in successful organizational change efforts that involve new information technologies. There are, however, some aspects related to the challenge ahead that are worth articulating.

First and foremost is the importance of realizing the imminence of the electronic economy and the business conditions that it progressively brings with it for fast response and shared knowledge creation. Second, when Storage Dimensions embarked on its customer-support-focused strategy in 1992, it started out with a passion for exceptional customer support, a strong belief that there had to be an IT-enabled solution, an understanding that this could only succeed if it was a company-wide effort, and an unwavering management commitment to make that happen. There is no functional management hero in this story, be it a customer service executive, or an IS executive, or a marketing executive. Rather, this is a company-wide cross-functional effort that required getting all the parts to work together in collaboration at all levels while continuously learning through customers. In the electronic economy, everyone fully participates in making IT-enabled solutions work and that will undoubtedly create new challenges and opportunities for the CIO and the IS function.

Third, we must point out that it is not just the TechConnect technology that has made the difference, but rather how the company has been able to stretch it, adapt it, and use it intelligently to better respond to the challenges of the present and simultaneously better prepare for the opportunities of the future. The customer support process has been transformed to be faster, smarter, cheaper, more learningful, and highly appreciated by its customers, partners, and industry – and even its competitors. What insights can be drawn that can be useful for others in redesigning IT-enabled knowledge-creating customer support processes that are suitable for the business conditions of the electronic economy?

Insights for redesign of knowledge-creating customer support processes in the electronic economy

Storage Dimensions is a small company with a grand total of 240 employees and limited resources. Many Fortune 1000 companies have more people than that solely in their IS departments. The company is also in the frenetically paced information technology Industry. Furthermore, because of the nature of Storage Dimensions customers’ mission-critical applications and product complexity, the customer support requirements are extremely demanding. However, we strongly believe that the lessons learned and the insights gained from the Storage Dimensions experience are applicable in any industry to companies of any size that want to have effective customer support and service process in the electronic economy. It is just that the trying conditions in which Storage Dimensions operates have driven it to actively search for (and fortunately find) an innovative IT-enabled response to the customer support challenge earlier than other companies may have needed to. The future is already here; it is just unevenly distributed.

The insights gained and articulated below are based on four sets of inputs. First, and most influential, is the Storage Dimensions TechConnect experience. Second, our collective experience about customer support and service has been incorporated into technology-based companies. Third, we have drawn on the state-of-the-art in what is known about IT-enabled business process reengineering (cf. Bennis and Mische, 1996; Davenport, 1993; El Sawy, 1998). Fourth, we have attempted to integrate what practitioners and researchers of fast learning and knowledge management through problem resolution systems have reported and suggested (cf. Kirkbride and Deppe, 1995; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995). These four sets of inputs are synthesized to produce a generic set of insights for redesigning IT-enabled knowledge-creating customer support processes and the issues around them. Presented below are the top seven insights that ‘bubbled up’ at this stage of our learning.

Insight #1: IT's biggest leverage in knowledge-creating customer support processes is in enabling ubiquitous problem resolution, not in providing complex problem routing.

We have learned that it is better to use IT to make new knowledge accessible to everyone at the front line than to route different problems to different specialists. The biggest payoff from using IT in knowledge-creating customer support processes does not come from call tracking technologies for increasing the speed or automating the complexity by which customer inquiries are routed, queued, or escalated. The biggest payoff comes from IT-based problem resolution systems that enable front line employees to answer any known question consistently and accurately. The TechConnect system at Storage Dimensions with its solution bubble-up feature enabled people without advanced expertise (whether a customer support person or a customer) to resolve any problem for which there was already an online solution. Using this philosophy had high payoff.

The nature of knowledge work is different from operational work and requires different reengineering strategies (cf. Davenport et al., 1996). It requires ways of capturing relevant knowledge from everyone who interacts with the business process. It is aided by questioning that helps elicit tacit knowledge and converts it into explicit shareable knowledge that is synthesized such that it is usable by all (Nonaka and Takeuchi 1995). It also requires different coordination strategles (Rathnam et al. 1995). In high knowledge-creation customer support environments it is not as useful to focus on escalating the problem up to the expert or the right person. The high payoff challenge is to make sure that everybody is the right person.

Insight #2: Problem resolution technologies with adaptive learning capabilities are much more suitable than traditional expert systems as IT infrastructures for speeding, up learning and creating new knowledge around customer support processes in rapidly changing environments.

The TechConnect experience showed how an IT infrastructure based on adaptive learning problem resolution technology can help create new knowledge ‘on the fly’ through customer dialogues without lag time between discovery of a solution and its availability to all in an intelligently accessible form. Storage Dimensions considered an alternative IT infrastructure based on expert systems, but decided against it. Traditional expert systems, whether rule-based expert systems, case-based reasoning systems, or decision trees, do not work well in situations where conditions change rapidly and a large number of cases or rules must be maintained. They require much up-front development work to develop cases or rules, need skilled knowledge engineers to make changes, and are not suited to contexts that have fluid structures with solutions-in-progress.

As an example, Storage Dimensions has an almost endless number of product permutations because of the way storage systems must work with a variety of other products (something like 10 models × 5 to 10 storage capacities × 5 operating systems × 3 to 4 revision levels × ∼100 configurations [memory, network interface card, peripherals]). The number of rules would be extraordinarily high. Furthermore, server technology changes every 90 days paced by Intel's microprocessor release schedule. Designing expert systems for creating knowledge in such a context would mean that by the time we finished redesigning it, its knowledge structure would have to be redesigned again. An excellent comparison of the robustness of adaptive learning systems as compared to traditional expert systems is available (Kirkbride and Deppe 1995). Key features of comparison are captured in Table 14.3

Table 19.3 Key features of comparison

|

Traditional expert systems |

Adaptive learning systems |

Knowledge Capture |

Time spent building workable rules and cases is prohibitive. |

On-the-fly knowledge capture such that knowledge base learns quickly and easily. |

Knowledge Retrieval |

Unsuited to solutions-in-progress. Requires large number of cases to provide problem-solving accuracy. |

Accommodates changing solutions and solutions that have fuzzy and incomplete knowledge. |

Knowledge Base Maintenance |

Very high effort to maintain changing rules with large numbers of cases. |

Self-organizing adaptive knowledge structure. |

Skill of Knowledge Engineer |

Requires skilled knowledge engineers to translate knowledge to rules and develop expert system. |

Problem/solution/symptom word structure is Intuitive and requires no special skill. |

Insight #3: The World Wide Web's strength as a contact route to a knowledge-creating customer support process is that it can provide powerful remote computational functionality for casual users (customers) through a standardized familiar interface.

The power of the World Wide Web for customer support is not in that it provides world wide e-mail, fancy multimedia, or brochure-ware capabilities. It is more than a pretty face: it provides a standard customer interface through web browsers that is ideal for capturing input from the casual user. In addition, it allows a user to submit a request for a complex computational task remotely and receive a response. For example, the TechConnect web access route allows a customer to submit problem symptoms to TechConnect that will then go search its knowledge base, make some computations that go beyond key-word search, and return with a list of probable solution documents. As Java-like capabilities are becoming more readily available, it is increasingly feasible to have more computational functionality for customer support interactions through the web. Already, we are beginning to see some vendors such as Netscape change the name of their browser software category from ‘browser’ to ‘client’ (cf. Muller, 1996 for an analysis of how help desk functionality is being expanded through the World Wide Web).

Insight #4: Use IT to enable as many different types of customer self-help routes as you can to a knowledge-creating customer support process, provided that you understand the prerequisite conditions for success.

In 1994, Storage Dimensions tried to give its resellers direct access to TechConnect from their remote computers by making it possible for them to appear to be a virtual TechConnect client complete with full GUI features. The technical implementation was superb, but they never used it. Apparently, for the casual user trying to play the role of technical support engineer, the functionality and richness of features of TechConnect were beyond what a casual user was willing to remember. On the other hand, the TechConnect e-mail and Internet connection are very successful, as previously discussed, and Storage Dimensions is steadily expanding the capabilities of those routes. The difference between the two situations is that Storage Dimensions has now understood the prerequisites for successful self-help routes. First, the route must fill a need that provides incentive for self-help (such as 24-hour access). Second, the functionality should not be more than a casual user can assimilate (currently TechConnect self-help does not allow direct knowledge base access). Third, there must be alternate routes with live customer support staff as self-help is not successful for all types of queries. Thus, self-help should only be attempted after a support staff is in place. Fourth, while the customer should be encouraged to provide new knowledge for the customer support knowledge base, care must be taken to protect its integrity.

Insight #5: There will be an increasing need in business organizations in the electronic economy to have a common interconnected ‘fresh’ knowledge warehouse that captures in near-real-time the knowledge created around all critical interdependent business processes, including the customer support process.

Data warehouses have become increasingly popular with business organizations in the last few years because businesses have become acutely aware of the criticality of joining data from the various interdependent parts of the organization and yet are able to serve each constituency in a customized way. There is a knowledge warehouse analogy to that for the electronic economy that would center around knowledge-in-action captured through various business processes (cf. Kalakota and Whinston, 1996). The key differences are inferred in Table 19.4.

It is envisaged that such knowledge warehouses would be built around knowledge creation processes rather than data, and there would be a much higher percentage of ‘fresh’ solutions-in-progress (or fuzzy data). A comparison of IT would probably have a higher percentage of interorganizational knowledge-creating routes than today's warehouse has interorganizational data feeds. As insight #7 suggests, the customer support process may be a promising space to start. However, it would also include knowledge created around other interdependent processes.

Table 19.4 The shift to knowledge warehouses

Knowledge warehouse |

|

Stable database structure |

Emergent database structure |

Does not learn from user access behavior |

Learns from user access behavior |

Passive; user retrieves information |

Active; system may initiate discourse |

Attribute search |

Attribute search and pattern matching search |

Scrubbed clean data |

Fuzzy incomplete knowledge |

Historical data |

Fresh knowledge |

Constrained interorganizational data feeds |

Rich intranet/extranet knowledge-creation routes |

Insight #6: Methodologies for redesigning IT-enabled knowledge-creating customer support processes in the electronic economy will need to cater to both learning changes and process workflow changes.

Business process reengineering methodologies for IT-enabled business processes have typically focused on changing the structure of workflow and the information around it. With customer support processes that have a large knowledge-creation component given the rapidly changing environment, there is an intimate interdependence between the mode of learning and knowledge creation (cf. Sampler and Short, 1994). Business process redesign methodologies will thus have to move to a higher order of analysis in which the way that the process learns (and becomes more learningful) is redesigned.

Insight #7: IT Infrastructures and knowledge bases built around adaptive learning problem resolution architectures linked to customer support processes can provide the first step toward building the faster-learning knowledge-creating organization of the electronic economy.

The Storage Dimensions experience has shown that using problem resolution architectures based on adaptive learning is one of the most systematic and natural ways that one can structure the way we learn and create knowledge. It can have very well-defined dynamic feedback loops that, when utilized properly, can both speed up the learning process and amplify the shared knowledge creation capability of a network of people. It has built-in knowledge consistency checks through constant interaction. It minimizes the time between the creation of new knowledge and its incorporation into the knowledge base in intelligently accessible form. It accommodates different levels of expertise by assuring that novices are not penalized for their lack of expertise and that experts are not burdened by unnecessary steps. It is a very smart way of creating new knowledge around business processes in action and appears to be one of the most promising paradigms for building IT-based learning organizations. Perhaps, after more than 20 years of trying, artificial intelligence has finally produced an appropriately targeted paradigm that will be of critical and widespread business use.

Furthermore, the customer support process is an excellent context around which to do this knowledge creation because it is the natural meeting space around which the organization, its customers, its partners – and often its competitors – exchange dialogue about current issues of importance to all of them (cf. Savage, 1996). It is the swiftest and most obvious context around which to capture shared knowledge creation in action and systematically incorporate it into a corporate knowledge base. Furthermore, the usual lack of physical proximity among different participants and parties makes the use of IT network-mediated exchanges all the more natural.

There is evidence to believe, based on the TechConnect experience, that the combination of using adaptive learning problem resolution IT architectures and the customer support process context provides the most promising first step in building a faster-learning, knowledge-creating organization. It is a context and IT architecture in which the mode of combining both the exploration and exploitation aspects of organization learning (March, 1991) promises to be effective for both the short run and the long run. Other areas of the business can be more easily linked through the customer support process than any other critical business process we know of because of its simultaneous critical intersection with many knowledge sources and its built-in time pressures that can drive participants to augment learning quickly. It appears to be the best and fastest space from which to start building the structural intellectual capital of an organization (cf. Quinn, 1992; Stewart, 1994). It is an excellent arena for building a learning relationship with customers (Pine et al., 1995).

Conclusion

This chapter began by showing how customer support and service needs are driving IS priorities more than they ever have before. It also pointed out that this is happening in the business environment of an emerging electronic economy in which fast response, shared knowledge creation, and internetworked technologies are increasingly critical. The chapter has shown that there are new IT infrastructures and knowledge creation architectures that can make a difference and that perhaps the way that the customer support process is changing will trigger enterprise-wide change in redesigning IT-enabled knowledge-creating business processes. This also heralds new opportunities and new responsibilities for the ever-changing role of the CIO.

The number of business organizations that are fully participating in the electronic economy will soon reach a critical mass. Having robust internetworked IT-enabled knowledge-creating processes that learn quickly from customers (and employees, partners, and competitors) will not be a strategic choice: it will become a strategic necessity for success in the electronic economy. We hope that this chapter has provided a compelling example to show how that can be done and that it will stimulate both practitioners and academics to find new ways of using information technologies to expand the knowledge-creating capacity of business processes.

Acknowledgements

We would especially like to thank and acknowledge Bill Kirkwood, who was part of this. Todd Schakerl kindly provided detailed information about the TechConnect System. We would also like to thank Dick Chase, Ann Majchrzak, the reviewers, associate editor, SIM Paper Competition committee, and especially the Editor-in-Chief Bob Zmud for their helpful feedback and suggestions.

References

Bennis, W. and Mische, M. ‘Reinventing through Reengineering: A Methodology for Enterprisewide Transformation,’ Information Systems Management (13:3), Summer 1996, 58–65.

Chabrow, E. ‘First Aid for Slipped Disks: RAID Vendor Storage Dimensions Builds the Virtual Help Desk,’ Information Week, June 12, 1995, 54–56.

Chase, R. B. and Garvin, D. ‘The Service Factory,’ Harvard Business Review, July-August 1989, 61–69.

Child, J. ‘Information Technology, Organizations, and the Response to Strategic Challenges,’ California Managment Review (30:1), 33–50.

Davenport, T. Process Innovation: Reengineering Work Through Information Technology, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, 1993.

Davenport, T., Jarvenpaa, S., and Beers, M. ‘Improving Knowledge Work Processes,’ Sloan Management Review, Summer 1996, 53–65.

El Sawy, O. A. Minding Your Own Business Processes: The BPR LearningBook, McGraw-Hill, New York, forthcoming 1998.

Entex White Paper. ‘Vendor Relationships: Trends, Options, Issues,’ Entex Information Services, New York, 1994.

Evans, B. ‘Numbering Success,’ Information Week, 12 February 1996, 6.

Haeckel, S. ‘Managing the Information-Intensive Firm of 2001,’ in The Marketing Information Revolution, R. C. Blattberg, R. Glazer, and J. D. C. Little (eds.), Harvard Business School Press, Boston, 1994.

Henkoff, R. ‘Service is Everybody's Business,’ Fortune (132:26), 27 June 1994, 48–60.

Kalakota, R. and Whinston, A. Frontiers of Electronic Commerce, Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA, 1996.

Kirkbride, L. and Deppe, S. M. ‘Evaluating Problem Resolution Technologies for the Help Desk,’ White Paper, Answer Systems Inc, 1995.

Lele, M. and Sheth, J. The Customer is Key, Wiley Books, New York, 1987.

March, J. ‘Exploration and Exploitation in Organizational Learning,’ Organization Science (2:1), March 1991, 71–87.

Muller, N. J. ‘Expanding the Help Desk Through the World Wide Web,’ Information Systems Management (13:3), Summer 1996, 37–44.

Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H. The Knowledge Creating Company, Oxford University Press, New York, 1995.

Pine, III, J., Peppers, D. and Rogers, M. ‘Do You Want to Keep Your Customers Forever? Harvard Business Review (73:2), March-April, 1995, 103–114.

Pitt, L., Watson, R. and Kavan, B. ‘Service Quality: A Measure of Information Systems Effectiveness,’ MIS Quarterly (19:2), June 1995, 173–187.

Quinn, J. B. Intelligent Enterprise: A Knowledge and Service-Based Paradigm for Industry, Free Press, New York, 1992.

Rathnam, S., Mahajan, V. and Whinston, A. ‘Facilitating Coordination in Customer Support Teams: A Framework and its Implications for the Design of Information Technology,’ Management Science (41:12), December 1995, 1900–1921.

Sampler, J. and Short, J. ‘An Examination of Information Technology's Impact on the Value of Information and Expertise: Implications for Organizational Change,’ Journal of Management Information Systems (11:2), Fall 1994, 59–73.

Savage, C. 5th Generation Management: Co-Creating Through Virtual Enterprising, Dynamic Teaming, and Knowledge Networking, 2nd edn., Butterworth-Heinemann, Stoneham, MA, 1996.

Savoia, R. ‘Custom Tailoring,’ CIO (9:17), June 15, 1996, 12.

Shostack, L. ‘Breaking Free from Product Marketing,’ Journal of Marketing (41:4), April 1977, 73–80.

Stewart, T. ‘Your Company's Most Valuable Asset: Intellectual Capital,’ Fortune (133:7), October 3, 1994, 68–75.

Treacy, M. and Wiersema, F. The Discipline of Market Leaders, Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA, 1995.

Reproduced from El Sawy, O. A. and Bowles G. (1997). Redesigning the customer support process for the electronic economy: Insights from Storage Dimensions. MIS Quarterly, 21 (4), December, 457–483. Copyright 1997 by the Management Information System Research Center (MIRSC) of the University of Minnesota and The Society for Information Management (SIM). Reprinted by permission.

Questions for discussion

1 Reconsider Question 6 at the end of Chapter 18 in the light of the Storage Dimensions case discussed in this chapter. How might the lessons to be drawn from the TechnConnect system be applied more generally?

2 Evaluate TechnConnect in the light of (i) Chapters 9 and 14, and (ii) Chapter 18. What recommendations would you make to Storage Dimensions as a result?

3 This chapter raises the important issue of improving customer support. What lessons do you take from this when considering information systems strategy and planning?

4 Relate the conclusions to be drawn from this chapter to those made by Porter in Chapter 13.

5 ‘Knowledge capture is one thing; knowledge creation is quite another.’ Discuss this statement in the light of the Storage Dimensions case.