![]()

CHAPTER TWO

E-HEALTH VISION

Drivers of and Barriers to E-Health Care

Joseph Tan

III. The E-Health Paradigm Shift

B. E-Health Versus E-Commerce, E-Marketing, E-Medicine, and E-Home Care

IV E-Health Drivers and Barriers

B. E-Health Barriers and Challenges

IX. Cyber-Angel: The E-Robin Hood Case

Learning Objectives

- Realize how the e-health paradigm shift has resulted in thinking, business models, and practices that differ from traditional health care

- Conceptualize e-health in the context of other related health care systems and environments

- Identify the primary goals and benefits of e-health systems

- Articulate the range of potential barriers and challenges to implementing e-health applications

Introduction

Over the last several years, the belief that our current health care systems in the United States and Canada, as well as many other countries, need major restructuring has been strengthening in the minds of a growing number of Canadians and Americans, including the insured, the underserved, and the underinsured; unionized workers as well as nonunion workers; and employees of major corporations, universities, nonprofit organizations, and federal, state, and municipal governments. Seminars, forums, working groups, special task forces, and major conferences have been organized at local, regional, national, and international levels to discuss this topic. Most people are now convinced that something must be done quickly to stop the spiraling costs of health care. Given the wide availability of the Internet and the ubiquity of wireless technologies, one promising approach is to investigate how access to quality health care services and products can be achieved in a more economical and equitable fashion using e-health concepts, infrastructures, technologies, interfaces, and strategies.

Indeed, based on figures released by the National Science Foundation on survey data aggregated between 1985 and 1999 and reported in Blendon and others (2001), I assert that the United States has now passed the first major stage of a technological revolution that is transforming the lives of Americans. The percentage of Americans who use a computer at work or at home more than doubled over those years, growing from 30 percent in 1985 to 70 percent by the end of the last century. More striking is the increase in home computer ownership, which quadrupled from 15 percent to 60 percent of Americans between 1985 and 1999. During an approximately five-year span in the mid-1990s, the number of Americans who had used the Internet at some point in their lives jumped from fewer than one in 5 (18 percent) to almost two-thirds (64 percent) of those surveyed. Moreover, in 1995, only 14 percent of Americans sampled in the survey reported that they had gone on-line to send or receive e-mail or to access the Internet; by 1997, this figure had reached 36 percent and by 2001 had risen to 54 percent. In addition, 92 percent of those surveyed who reported having used a computer were younger than 60. Among those, 75 percent have used the Internet and 67 percent have sent an e-mail message. Finally, most Americans feel that the computer's impact on society has been largely positive. More than half surveyed indicated that the computer has given them greater control over their lives. Given these statistics, it is anticipated that the diffusion of e-health care is imminent.

In the previous chapter, we reviewed the three general themes encapsulating the evolution of the e-health field: foundations and benefits of e-health, domains and applications of e-health, and e-health strategies and impacts. We noted that new experience and knowledge are transcending the mainstream disciplinary boundaries of information technology (IT). Advances in information, telecommunication, and network technologies and their applications in e-commerce have led the way to new forms of health care delivery, specifically, e-health.

In contrast to traditional health care systems, e-health has developed to become a niche industry with the potential of providing, in one way or another, greater access to a growing range of health care products and services. Access can be increased in rural, inner-city, and remote areas; in underdeveloped as well as developing countries that lack the medical expertise or technology to protect and promote the health and well-being of their populations; and in areas that are difficult to reach, such as prisons, military bases, or aircraft, cruise ships, and space shuttles. As long as emerging e-technologies can be applied successfully, there is potential for e-health systems to evolve, survive, and thrive.

In this chapter, we conceptualize e-health as it relates to other existing health care systems and environments. Indeed, some health care hierarchies could be considered parents or grandparents or conversely, sons and daughters of the e-health care system. We need to recognize some of the interrelationships among these systems at different hierarchical levels. Our primary focus, therefore, will be to describe the overarching vision of the e-health paradigm shift, providing the reader with an understanding of the primary role of e-health systems, their goals and benefits, and why they should exist and be promoted in the face of increasing complexities and environmental uncertainties. We will look carefully at the drivers of and barriers to e-health systems—that is, (1) what drives the e-health revolution and (2) what challenges e-health systems must overcome in order to thrive and grow. As we lay down the tracks for the e-health train to move forward, we must ask ourselves what impediments we must be aware of and how we should respond to these impediments.

The E-Health Paradigm Shift

Many of us are familiar with the concept of a paradigm shift, a revolution of thoughts and actions that often results in a complete turnaround of earlier generational or traditional thinking and models in a field or even an era. For example, Einstein's theory of relativity was a paradigm shift in physics from Newton's law of gravity. Similarly, the industrial revolution, which began in England in the middle of the eighteenth century, was a paradigm shift, transforming society as machines began to replace animals and human workers.

In a similar vein, the technological revolution discussed at the beginning of this chapter is a paradigm shift that in turn is ushering in the e-health revolution that we are witnessing today. E-health can be conceived as a paradigm shift away from traditional approaches to health care and service delivery. In traditional health care systems, the focus is on caring for the sick rather than promoting wellness; in e-health systems, the focus is on preventive care and ubiquitous health care services. The traditional health care system transports the sick and those in need of treatment and healing to the doctors and specialists; the e-health care system moves or transmits key data, information, knowledge, and even products and services to the e-consumers and anyone who needs the data, information, knowledge, products, or services, including paramedics, nurses, and general practitioners.

In essence, transforming the way in which health care information, data, knowledge elements, products, or services are transmitted from a physical mode to a digital mode completely changes the way health care business can be conducted. At least in theory, e-consumers or their intermediaries (for example paramedics) will be able to access evidence-based medicine. Evidence-based medicine is the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients (see Case section of Chapter Fifteen). This will help seek out the best experts in any medical specialty field at the click of a mouse; specialists, doctors, psychologists, and nurses will be able to connect directly with e-patients and e-consumers or other intermediaries without being limited by time, space, or geographical location. And data could be shared among general physicians and specialists without face-to-face meetings.

Marvelous as this paradigm shift may sound, in order to realize its benefits, we must be able to articulate a clear vision of e-health that encompasses a comprehensive understanding of its general purpose, goals, and benefits.

Vision

From a practical perspective, the e-health vision must begin with a national strategy to create a common platform to do business. Extending this idea to a global perspective would translate into international agendas for (1) information and technological standards, (2) public health information infrastructures and highways, (3) electronic and digital networks to connect different health care professionals from all over the globe, and (4) a philosophy that good health care should be ubiquitous.

From an ideological perspective, e-health must go beyond the fear that universal health care may result in long waiting lines and a socialist or communist state paying for the poor and unproductive. It is argued that the vision of e-health is to promote general health care as a public good and to fight for greater public accountability on public investments in health care. It is a vision of more available, accessible, and affordable health care for everyone.

From a philosophical perspective, the e-health vision takes a positivist, evidence-based view, which leads to more secure and improved sharing of health care data and records for efficient and effective health care delivery and the promotion of citizens' well-being.

As we shall see, this vision applies to all areas of health care, including preventive health and health promotion, occupational and environmental health, population and public health, maternal and child health, emergency and non-emergency health care, and health education and training.

In the domain of preventive health and health promotion, e-health agendas could focus on smoking cessation, responsible driving, workplace accident prevention, healthy lifestyle behaviors, diet and nutrition, or walking and exercise. New opportunities could be created through the use of e-interventions and e-technologies. A network strategy, for example, could be employed to permit a sharable platform, perhaps using XML (see Chapter One) and on-line analytic processing (OLAP) to analyze and process data on a real-time basis. Initially, the network might serve a small number of connected, powerful servers, and the incoming data stream might be directed into a data warehouse for periodic cleaning, organizing, and mining. As the system grows, the network could be made accessible through the Internet, and data acquisition, cleaning, and analysis could be completed in real time. Such a system would provide the necessary infrastructure to support a national or even international information network that could track the health status of individuals, groups, communities, societies, and populations. Various data mining techniques could be applied, not just to monitor the effects of unhealthy behaviors or circumstances but also to track positive outcomes. The vision of such a system is to promote the health and well being of the population linked to this network. Indeed, such automated results of analysis might also prove useful for export to less developed nations (see Chapter Eight).

In the domain of public health care, for example, Yasnoff, Overhage, Humphreys, and LaVenture (2001), see a demand for a continual stream of information to be transmitted electronically “from a wide variety of sources regarding the health status of every community, to be collected, analyzed, and disseminated.” Through the use of intelligent electronic health records, they argue, “automated reminders could be presented to clinicians for individually tailored preventive services, immediate feedback on community incidence of disease could be available, and public health officials could activate specific surveillance protocols on demand. Furthermore, customized, individualized prevention reminders could be delivered directly to the general public.” Such a proposal could easily be extended to an international level, whether in public health or other areas, such as occupational and environmental health. Similarly, a surveillance system at a national level could be created to guard against major bioterrorism threats or pandemic and epidemic disasters caused by viruses such as HIV/AIDS, SARS, avian flu, West Nile virus, chicken pox, and monkey pox.

Applying this sort of thinking at an international level, therefore, our vision of e-health will specifically involve creating a real-time, on-line global disease surveillance network to maintain and promote the health of populations living in different communities across different countries, all of which would sponsor, support, or contribute data to this network. Any potentially threatening patterns of infectious diseases could be quickly detected and reported. The information could immediately be disseminated to all public health authorities and agencies subscribing to the global network. Such efficiency would be extremely beneficial because time is a vital factor in this kind of disease surveillance, monitoring, and prevention.

In the domain of maternal and child health, a similar national or international health information strategy could be instituted. Pregnant women could be teleeducated about (1) the positive effects of breast-feeding, proper diet and nutrition, and use of vitamins and supplements; (2) the negative effects of smoking, excessive drinking, and other behaviors; and (3) the identification of risk factors throughout the various stages of pregnancy and labor. Midwifery teletraining and education modules could also be developed to provide midwives with critical knowledge on how to prevent or overcome conditions that lead to maternal or child death or injury. Training modules on family planning, use of contraceptives, and the risks of sexually transmitted diseases could also be provided. Key to success is the will of the government and the people of a country to support the diffusion of e-technologies. Of course, strong leadership from the top is critical, especially in developing and less developed countries, to making the e-health vision a reality.

E-Health Versus E-Commerce, E-Marketing, E-Medicine, and E-Home Care

Conceptually, e-health is the umbrella term for applying existing and emerging e-technologies in combination with innovative or improved processes to transform mainstream health care business practices. Business processes require innovation and improvement because, in many instances, the delivery of e-health information, products, and services requires a different way of doing business. Whereas traditional health care information exchange, product retailing, and service delivery focus primarily on empowering health providers and professionals, the vision of e-health focuses on empowering users, typically laypersons or consumers, without limiting its potential to empower other stakeholders, including health professionals. Several key e-health domains have already diffused and are becoming popular and even profitable—for example, e-marketing (telemarketing), e-medicine (telemedicine), telehealth, and e-home care (telecare). (The term e-marketing is used here because telemarketing has been overused and connotes the use of telephones more than the use of the Internet or other digital media.)

E-health (sometimes referred to as telehealth) is one of the most broadly defined terms in this text (see Chapter Eight for more on definitions). It encompasses e-commerce and e-marketing and all forms of e-medicine (or telemedicine), decision support, e-business intelligence in health care, and e-home care applications. It can be defined as the use of existing and emerging e-technologies to provide and support health care delivery that transcends physical, temporal, social, political, cultural, and geographical boundaries. Examples of services include but are not limited to e-marketing, e-medicine, e-consulting, e-learning, e-diagnosis, e-imaging, e-home care and emergency support, and transactional transmissions.

E-commerce is another very comprehensive term referring generally to the application of e-technologies in order to realize business transactions. E-health includes e-commerce information exchange and transactional activities; in recent years, three important classes of e-commerce have grown in popularity. One of these is business-to-business (B2B) transactions. The business entities on either side of a B2B transaction can include e-vendors, e-caregivers, e-payers, and e-regulatory agencies. Another class of e-commerce is business-to-consumer (B2C) transactions. Consumer-to-consumer (C2C) transactions, a more recent development, contribute to the creation of virtual health networks and e-learning communities (e-communities). B2C applications are most closely related to our vision of e-health because they focus on delivery of data, information, knowledge, products, and services directly to e-consumers.

E-marketing (or telemarketing) systems are B2C applications, selling goods and services on-line to increase market share and profitability and also working to create a brand name over time. For example, www.WebMD.com offers Internet health care that connects e-physicians and e-consumers and allows e-consumers to choose physicians, schedule appointments, check claims' status, and view laboratory results. In addition, the site promotes a brand name (WebMD) to differentiate its e-physicians from mainstream physicians. ViagraPurchase (www.ViagraPurchase.com) offers on-line consultations for e-patients seeking Viagra through the Web, with guaranteed forty-eight-hour delivery of the Viagra. Brand names such as Johnson & Johnson skin care and baby products, OneTouch's ultrasoft automatic blood sampler and other medical devices and McNeil's Tylenol and other pharmaceutical products have all become known through traditional advertising and retailing. E-marketing promises to do the same for emerging Internet-based businesses, providing both retail potential and image advertising.

Many health insurers, HMOs, and e-health groups are also using e-marketing not only to create brand names but also to project a professional public image. The time may indeed have come for these entities to present themselves as being on the leading edge and fully able to deliver goods and services through the Internet, community health information networks, third-party portals and Web services, or the private networks of multinational health insurer and provider organizations. These systems are also used (1) to sell health information or provide e-consultation to e-consumers and e-providers on specific topics, (2) to fulfill e-prescription orders, and (3) to dispense over-the-counter health care products, medical devices, books, and associated services. For instance, MedSite (www.Medsite.com) e-markets products such as medical books and “doctor's bag” equipment from its on-line health care specialty store.

E-medicine (or telemedicine) is the deployment of information and telecommunication technologies to allow remote sharing of relevant information or medical expertise, regardless of the patient's location. Broadly speaking, e-medicine is a subclass of technological innovations that have been evolving to bring affordable medicine to the masses as well as to remote places. A key feature that distinguishes e-medicine applications from simple videoconferencing systems is the use of associated peripheral devices that enable e-clinicians to better approximate an on-site examination. These include electronic versions of standard examination tools, as well as other sensitive electronic instruments such as close-up cameras, microscopes, and dermascopes. These tools are not readily available at this point in time as they require large communication bandwidths, powerful servers and sophisticated Al-based systems. We expect most e-medicine applications to provide mostly e-monitoring of patients' vital signals through remotely controlled equipment.

E-home care (or telecare) is the application of e-technologies to assist patients who choose to be located at home rather than at a health care facility (see Chapter Nine). Many patients who have chronic illnesses such as diabetes; broken limbs; or mental illnesses are aided through electronic monitoring devices and other e-care services, such as e-transmission of blood test results picked up through sensors in the home. The latest developments in telecare have been moving toward integrating expertise from specialists such as psychologists, architects, computer scientists, clinicians and specialists, and builders and contractors trained in “smart homes” for the disabled, homebound patients, and seniors.

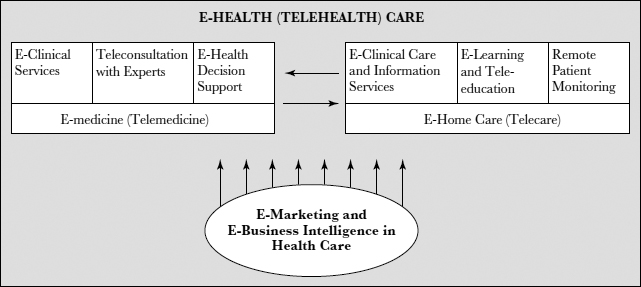

Figure 2.1 illustrates how various e-health care concepts relate to one another. The figure shows that the e-health care system is complex and its environment multifaceted. This may partly explain why IT in health care tends to fall behind IT applications in business (as is discussed in the next section).

FIGURE 2.1. E-HEALTH CARE SYSTEMS AND SUBSYSTEMS

For many years, mainstream health care has been driven largely by primary health (acute) care needs, with attention shifting under special circumstances to secondary and tertiary care (referrals to rehabilitation and home care). While traditional health care provision may be the best form of acute and emergency care, most needs today have to do with non-emergency, secondary, or tertiary care areas—for example, chronic pain, management of cancer or heart problems, malnutrition, mental illness, excessive fatigue and stress, lifestyle and social behavioral problems, poor immune systems, and palliative care. E-health services are appropriate for these types of care. Hence, e-health care may be seen as a transforming health care agent because of its focus on preventive health and wellness, health promotion, non-emergency health care, selfcare, health information therapy, and more directed self-care such as checking blood glucose and taking medications as prescribed.

We will now turn to the specific goals and benefits of e-health systems that will drive the future growth and development of e-health.

E-Health Drivers and Barriers

If the vision of the e-health system is to achieve better health and well-being for the general population through the application of e-technologies, the key goals must be to improve and enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of the existing system by making products and services more available, accessible, affordable, and accountable. We therefore begin by looking at system goals and benefits as underlying drivers for the paradigm shift. (See Chapter Twelve for more on challenges of e-health.)

System Goals and Benefits

As noted, the drivers of e-health are trends that should lead to achieving more comprehensive, reasonably inexpensive, and easy-to-access health care products and services for everyone. Yet the level or standard of e-health care in any given environment or system will likely be the minimum standard expected within that environment or system. Therefore, standards may vary significantly from one country or jurisdiction to another. For example, pursuing the goals and associated benefits of e-health care in the United States or most other developed countries could lead to expectations that all citizens could access health-promoting information, products, and services anywhere and anytime at a reasonably low cost, partly because of the huge amount of public investment that is made in health care on a yearly basis. If the same goals were pursued in developing areas such as sub-Saharan Africa (see Chapter Eight), the expectations would be vastly reduced because of the smaller economic means and lower health care standards there.

For these goals and benefits to be achievable, new legislation and policies will need to be implemented that are conducive to promoting e-health practices. Without supporting policies, all of the possibilities in this book will be totally theoretical, and we will be a long way from implementing and realizing e-health care.

As these policies and new legislations become implemented, e-health care can yield the following benefits:

- Availability and accessibility of health care knowledge and expertise, especially for the underserved and underinsured

- Availability and accessibility of quality health care on a more equitable basis to underserved rural and urban areas

- Comprehensive availability of e-clinical services, regardless of time, specialty, and geographical location

- Availability of e-health services for new and alternative (non-invasive) medical procedures

- Savings for e-providers and e-patients in procedural, travel, and claims processing costs

- Educational service networks for isolated health professionals, residents, and nonexperts

- Empowerment of e-consumers and e-providers

- Reduced use of traditional emergency services

- Improved non-emergency services

- Decreased waiting time for non-emergency services

- Greater awareness of services among rural and remote residents and caregivers

- Availability and timely accessibility of critical information in the event of emergencies

If these benefits are to be realized, a gradual shifting from the traditional health care delivery system and environment to virtual forms of health care delivery systems and arrangements is needed. Thus, the evolution of e-health concepts, infrastructures, technologies, applications, interfaces, and strategies all contribute to the paradigm shift. For example, e-health concepts and strategies are vital for health care reform and new ways of thinking about health care delivery; e-health technologies and applications provide alternative means of delivering health care products and services; and e-health infrastructures and interfaces offer convenient mechanisms for transmitting medical and clinical knowledge to residents, non-experts, and health care workers. Moreover, e-health methods and strategies encourage innovations in non-invasive medical interventions, a focus on preventive measures, and greater emphasis on self-care and rural medicine.

In addition, e-health can aid in realizing rapid changes in a nation's health care infrastructures, financing, administration, management, and care delivery systems and procedures such as reduced administration costs and eliminating “inappropriate and unnecessary” emergency services. These goals and benefits, to the degree that they are realized, will further propel the growth and development of e-health in years to come.

Modern technologies are now pervasive in many societies. Citizens of developed countries, including the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom, have significant access to consumer-oriented e-health information, albeit of variable quality. Entering a general word or phrase like health care into an Internet search engine will result in an overwhelming amount of information. Using the specific term e-health results in a number of relevant searches. This indicates a social trend in changing customer's attitudes toward e-health. More informed and better-educated consumers are also driving the e-health paradigm shift. Moreover, reduced administrative and medical costs due to more efficient information flow and more effective workflows will further reduce the cost of products and services, thereby adding to the growth of e-health. For instance, Web technology can replace fragmented paper trails and incomplete telephone messages with archived notes and electronically posted messages to coordinate time-consuming and complex communications between e-consumers and e-caregivers. Virtual private networks eliminate low quality, limited time-space connection while enabling secured transmission of large amounts of data among connected parties that are geographically apart. Costs associated with postage, paper, and long-distance phone calls can also be minimized.

Growing public awareness of the use of the Internet and its associated technologies and services also drive the growth and development of the e-health market-place. E-consumers are able to search out relevant and useful information and work toward gaining continuing support from e-care professionals. Making information and tools available to e-consumers for planning their own treatment regimens and comparing notes with others will further enhance their trust in the e-health care system. It will also encourage them to share their many hidden concerns with e-caregivers, who can provide the virtual presence of someone who cares. People who suffer from chronic illnesses such as cancer, diabetes, fibromyalgia, and AIDS already draw support from other patients with similar challenges through Web chats, on-line support groups, e-mail messages, and newsgroups. (Trade-offs in regard to support groups will be pointed out later in this chapter.) Educating and empowering e-consumers on-line will enable them to become active participants in self-care, thus potentially resulting in greater satisfaction.

Today, when a patient walks into a physician's office, office personnel frequently use the phone to verify the scope of the patient's insurance. An e-health system can give physician's offices immediate access to such information. Once a service is rendered, on-line claims can be initiated and completed in just a few days, as opposed to the current weeks or even months it takes to get a reimbursement from an insurance company with manual form processing. Moreover, time and cost savings can quickly add up to hundreds of millions of dollars, including savings for the insured (who do not have to worry about a delay in verifying treatment eligibility or complete claim forms to find out that claims have been denied), the providers (who are spared delays in reimbursements and nonpayment for their services) and the insurers (who need less personnel for manual claims and experience fewer processing inefficiencies, such as keyboarding mistakes or illegible writing). The total savings on paper alone can sometimes be overwhelming: Hewlett Packard electronically stores ten terabytes of information per month, equivalent to a stack of paper three hundred miles high. Employees and consumers will also be able to access the information they desire precisely. This enhances the “pull” as opposed to “push” nature of the communication among insurers, providers, and patients. Global health corporations can facilitate instantaneous communication between e-providers and e-consumers, allowing them to have discussions that would not have previously been possible.

All of this has also created an expectation that future health services should eventually subscribe to the e-health vision. People, in general, expect the same level of services from an e-health care system as from the traditional health care system.

This brings us to a discussion of the barriers to reaching the e-health vision described in the beginning of this chapter.

E-Health Barriers and Challenges

Perhaps the most essential ingredient for vibrant e-health development is assurance for citizens and e-health care professionals that an e-health care system will in fact lead to improved health as opposed to fraud, medical misinformation, abuse of consumer data, marketing of products and services that are of little or questionable value, or e-care services that fail to satisfy their needs. In other words, evaluation of the existing e-health care system is important to ensure that the goals and benefits can be and are being achieved. Policies and mechanisms must be created to oversee the development and growth of e-health, including legislation against fraud and unethical practices and for protection of patient privacy and confidentiality of e-patient data.

Unfortunately, e-health is far less developed than traditional health care, which has been established over the last several centuries, or even e-business ventures, despite the similar transactional processes involved. Much skepticism has been expressed about the proliferation and diffusion of e-health, primarily because of fear of change, resistance from health care professionals, consumer concerns over privacy and security issues, competing interests among innovations for venture capitalists and funding sources, and continuing environmental and political uncertainties. Venture capitalists and investors are also wary of putting money into a health care system that is financially at risk, that lacks coherence and cost control, and that has byzantine requirements for computing costs and returns on investments. For example, even with state-of-the-art information systems in many health provider institutions, it is difficult, if not impossible, to give the precise cost of any specific medical procedure. For example, the cost of a hip replacement surgery depends on the condition of the patient, the seniority and prestige of the surgeon, the cost of the specific materials used, the length of the patient's stay, the facility in which the procedure is to be undertaken, and many other factors.

The lack of standards or at least a coalescing consensus on standards can be detrimental to building e-health infrastructures and highways for rapid transmission of e-health information, products, and services. System chaos can result when there are too many different platforms, software standards, security procedures, and programming languages, each attempting to stake out a niche in the billion-dollar e-health technology marketplace. The complexity of implementing common shareware without compatible standards creates undue or unnecessary delays in collaborative projects. Lack of standards also presents the risk of strengthened user resistance, especially from health professionals. Not only can the installation of a proper infrastructure assist in managing multiway communications among e-stakeholders, but it can also motivate e-workers to share information and participate in discussions as to best practices and evidence-based medicine. Of course, the federal government or a multinational corporation like IBM or Microsoft will be expected to provide the strong consensus-based leadership needed to champion and oversee the process of achieving standardization among major e-stakeholders.

Another area of challenge is e-work design. In many instances, consumers, providers, and insurers are not prepared for the changes in their respective information management roles. The transition to e-consumer empowerment means that e-provider corporations will become information disseminators rather than information gatekeepers. Recognizing this change in business functioning is critical to the success of e-health operations. Workers must be trained differently and companies must begin to learn how to manage e-work. Information system analysts and Web developers may also feel threatened as e-consumers and e-providers dictate specific information management functions and requirements instead of relying on the “experts.” Poor and inadequate e-technologies and interfaces will not be tolerated and will fall by the wayside. All of these changes will lead to new work processes for everyone in the system. Trial and error is inevitable, but continual quality improvement and well-designed evaluations are equally important.

Data security and confidentiality of patient information are two of the most important concerns in the application of e-health technologies. Security access is a major concern as e-health technologies become available to a huge number of users spread across literally boundless geography. Appropriate firewall protection, data encryption, and password access can all be employed to manage security issues; however, computing viruses are getting more sophisticated as security technology increases. The American Medical Association has developed stringent security procedures to prevent unauthorized access to computerized patient records, including an indication that individuals or agencies can only access confidential medical data with bona fide intent. In order to use e-technologies effectively, it is important to define to whom access will be granted and what level of patient data may be shared. At Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, the five-hospital patient record network has a 512-bit key encryption, a level of encryption that is standard in many contemporary e-business applications. This ensures a secure transaction which is capable of running on multiple platforms. Audit trails and separation of duties can also be used to beef up data security.

Here is a brief illustration of one e-health challenge. As many as 20 to 30 percent of the world's people may have literacy problems. In addition, many U.S. citizens are monolingual, and large numbers of European, Asian, African and Latin American people speak limited or no English. The variety of languages and cultural assumptions of potential e-health users present a natural barrier to sharing information. While automatic translators could conceivably be installed to reformat Web sites in English into other languages, and user responses in various languages could also be translated back to English, many medical terms are difficult to translate, and hidden connotations in one language may result in missed concepts or information when remarks are translated. In addition, use of certain symbols, colors, and layouts may convey different meanings to people of different cultures. For example, any attempt to teleconsult by e-providers who do not speak the same language will always be a challenge.

Medicolegal Considerations

Because the present technology appears to be capable of handling the demands of e-health care in most applications, the question arises as to why it is not used more often. Liability concerns are one major reason (Daley, 2000). According to Kleinke (2000), “IT executives have long blamed physicians” and their resistance to computers for the lack of widespread IT adoption in health care, while those same IT executives were perpetuating the real impediment. In the training manuals and other documentation of all health care IT products, one finds a vendor's legal disclaimer for any negative clinical consequences, typically on the very first page.

The liability issue is not new, nor is it unique to e-health care. The part that is unique is the need to determine laws and standards of care that govern e-health practice. It has been much debated whether a patient's location should govern the issue of liability, to prevent physicians from “forum shopping”—that is, practicing in states or countries with the most favorable liability laws. Presently, there is little legislation or judicial precedent regarding e-health care services. Physicians hesitate to get involved when there is not a well-defined legal framework or standard of care. Many e-health Web sites simply cater to whoever would like to purchase products and services, without carefully considering the medicolegal implications of the transactions.

Another major obstacle to the growth of e-health care is the problem of reimbursement for services. E-health products that are sold as business goods can use existing electronic payment systems, but a broad system for reimbursement for e-health care services is still unavailable. From April 1999 through December 2000, only 235 instances of telehealth services (valued at $15,082) were paid for under Medicare. During the same period, the total amount paid by Medicare was $4,030,103,894 (Wachter, 2000). It is also unclear whether e-health care is an eligible and legally insured service under federally funded capitated payment or health maintenance organization programs.

Another hindrance to the diffusion of e-health care is the fact that physicians and licensed practitioners are legally required to have separate medical licenses to practice in each state. E-health care allows health care services to cross state boundaries, but some states have laws designed to keep out health professionals who are not licensed in that state.

Before the practice of e-health can diffuse and become widely accepted in the United States and other developed countries, their respective governments must enact policies regarding the appropriate use of the Internet for direct patient-provider e-consultations, e-clinical care, and e-prescribing. Ideally, there would also be limitations on practitioners' liability as a result of providing e-health care services. For e-consumers, there must be assurance that privacy and confidentiality will be protected in the transmission of sensitive information and e-storage of their personal records. The next part of this book provides a brief glimpse of some potential developments and breakthroughs that are shaping the future of e-networking.

Conclusion

This section has attempted to demonstrate, despite a lack of both theoretical and empirical published research, that the implementation of e-health in hospitals and healthcare organizations is a challenge that has to be overcome from many angles if e-health is to succeed. As we have seen, one major hindrance in deploying e-health applications is the lack of a legal infrastructure that can administer and manage them. We believe that there is huge potential for e-health to improve human health services and to achieve the vision set out earlier in this chapter, if humans can make appropriate and ethical use of electronic technologies. E-health is beginning to permeate all aspects of the health care industry. Many of these technologies are no longer new, and it is up to humans to implement them now.

Chapter Questions

- What is meant by the phrase the e-health paradigm shift? Provide some examples of trends toward this paradigm shift.

- What do you envision as the purpose of the e-health care system? What is the significance of this vision in the development of global health care?

- Who would be primarily responsible for successful implementation of the e-health care system? What challenges must be overcome for e-health to survive and thrive?

References

Blendon, R., Benson, J., Brodie, M., Altman, D., Rosenbaum, M., Flournoy, R., & Kim, M. (2001). Whom to protect and how? The public, the government, and the Internet revolution. In The Brookings Review (pp. 44–48). Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, Winter 2001, Vol. 19 No 1.

Daley, H. (2000). Telemedicine: The invisible legal barriers to the health care of the future. Annual Health L, 9, 73.

DICOM Standards Committee and Working Groups. (1998, December). DICOM committee procedures. Retrieved May 15, 2001, from Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine Web site: http://medical.nema.org/dicom/wgs.html

Kleinke, J. (2000, November–December). Vaporware.com: The failed promise of the health care Internet; Why the Internet will be the next thing not to fix the U.S. health care system. Health Affairs.

Wachter, G. (2000, March 26). Two years of Medicare reimbursement of telemedicine: A post-mortem. Retrieved May 15, 2001, from http://tie.telemed.org/legal/issues/reimburse_summary.asp

Yasnoff, W., Overhage, J. M., Humphreys, B., & LaVenture, M. (2001). A national agenda for public health informatics: Summarized recommendations from the 2001 AMIA spring congress. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 2001, 8(6), 535–545.

Cyber-Angel: The E-Robin Hood Case

Joseph Tan, Joshia Tan

Cyber-Angel is an e-health system sponsored by a few local Detroit radio and television networks and partly funded by nonprofit organizations and foundations, including the Detroit FreeCare Enterprise, Total HealthCare Union, and Michael Livingston Foundation. Cyber-Angel was created by a group of volunteer social workers, e-physicians, e-health practitioners, e-health care activists, and e-nurses. During a local e-health care conference, these volunteers decided to spearhead Cyber-Angel with the hope of providing long-lasting empowerment for the underserved and underinsured through low-cost e-health information and knowledge diffusion. In listening to a keynote speech, these volunteers were convinced of the inadequacy of the current U.S. health care system, especially in Detroit, to meet the needs of America's poorest and least educated people, some of whom were living in rural areas as well as in inner-city areas in cities like Detroit.

Cyber-Angel Operations

To make Cyber-Angel accessible, secured kiosks using touchscreen technology were installed in public places such as railway stations and group homes. Essentially, Cyber-Angel is an innovative Web site that allows needy e-consumers to obtain e-health services without having to pay regular insurance co-payments. In most cases, users only pay a quarter, which allows them to operate the system for about twenty minutes. About sixty kiosks have been installed throughout the inner city, and more are being planned. Plans have also been made to incorporate voice recognition technology in order to reach more people. In an attempt to reach out to the elderly, some volunteers are contemplating installing systems on desktops placed in seniors' homes and providing free access IDs and passwords. Presently, Cyber-Angel volunteers and donors can get free access to the Web site via the Internet through the use of their IDs and a secure password; other e-consumers who want to access Cyber-Angel must use one of the installed kiosks. The possibility of providing a subscription capability for registered users who want to pay a regular fee for the service has been discussed, but nothing concrete has been decided.

Friends of Cyber-Angel

Cyber-Angel acts like an E-Robin Hood, taking resources from those who are wealthy and able and giving them to the poor and needy. The Web site therefore invites donations from anyone who would like to contribute time, money, or effort to aid fellow Americans who carry no medical insurance coverage. Cyber-Angel has managed to attract a large network of volunteers, including lawyers, social workers, physicians, psychologists, nurses, and students. Each donor or volunteer is automatically assigned an ID and asked to select a secure password.

Here are several examples of how the volunteer system works: Mary is a trained nurse who registered to provide volunteer e-nursing service (providing nursing advice on an e-consultation basis) on two weekend night shifts from her home PC. Meanwhile, John raises funds for Cyber-Angel by e-mailing the list of potential donors from time to time, tracking and monitoring pledges and fulfillment on his desktop computer. Heidi is a well-trained medical resident with extensive training in naturopathy. She seeks to pass on some of her medical training and to share her knowledge of naturopathy. During her volunteer hours, Heidi contacted a number of clients through Cyber-Angel, which she installed on her portable handheld. One such client, Steven, who now volunteers for Cyber-Angel, ceased smoking under Heidi's care and got in the habit of performing stretching exercises on a daily basis as directed by Heidi. Soon, Steven moved out of his group home, altering his diet and daily habits. He found a job at the local supermarket and told Heidi that he would volunteer his time to help others like himself benefit from Cyber-Angel. He was encouraged to register as a fundraising volunteer in order to keep Cyber-Angel active and to perform tasks similar to John's. Steven even became a health activist in his old neighborhood, raising awareness of the adverse effects of smoking among the smokers he had been living with at the group home.

Each year, the sponsoring radio and television networks run a joint campaign for fundraising, featuring Cyber-Angel in order to raise awareness among the Detroit public. These campaigns have generally been very successful, with the mayor of Detroit or the governor of Michigan present to kick off the events. Names of donors are automatically entered into Cyber-Angel's system and displayed in a section of the Web site, along with information on the level of donations and the types of volunteer services that the donors are supplying. Donors are automatically assigned an ID, then choose a password for Cyber-Angel and enter the amount they would like deducted from their bank account or credit card. In return, donors at all levels receive access to Cyber-Angel free of charge for their donation year. The average donor gives about $43 or an hour per month of their time, which is the recommended time commitment for volunteers.

Lessons from Cyber-Angel

Cyber-Angel's kiosks are currently available in three counties in and around Detroit, but more counties will soon have kiosks installed. E-health activists and professionals from other American cities are aware of this system. Some have traveled to Detroit to observe how the system works and have also initiated or welcomed similar concepts. Conferences are being planned to demonstrate some of these systems and to share information about the core value propositions, the infrastructure and e-technologies used, and the effects of these systems on users as well as on e-providers.

A recent analysis of Cyber-Angel reveals a number of core value propositions:

• Cyber-Angel is readily available and easy to operate, especially for those who need non-emergency health care services and cannot afford to see a doctor or a health practitioner. (Most users want to ask for medical advice and need someone to talk to about getting back their health and getting themselves out of their bad habits, services which do not require physical visits.)

• The system builds rapport between e-consumers and e-caregivers because Cyber-Angel services are not rendered based on monetary rewards for the caregivers but for the purpose of assisting users in need. Caregivers get satisfaction from resolving nonemergency health problems that could become serious if neglected. In addition, over time, e-caregivers get to know their clients, and e-consumers are welcome to e-mail their e-caregivers directly anytime. E-caregivers have the choice of replying to e-mails only at the times that they are scheduled to work.

• The Cyber-Angel system accumulates and houses important information in a data warehouse for future mining. Researchers are convinced that data analysis will unveil critical needs of the underserved, based on the types of questions and interactions that are being analyzed. Analysis of these data will almost certainly lead eventually to a better version of the Cyber-Angel software, as well as improved information for policymaking, particularly in the areas of public health and individual health care for the underserved and underinsured.

• Finally, the Cyber-Angel system promises to alleviate some of the demands on emergency care provided by local hospitals, because people, especially those who do not require immediate health care attention and cannot afford to pay, can be directed to use Cyber-Angel instead.

Conclusion

Despite its many advantages, Cyber-Angel faces many challenges and ethical questions. The City of Detroit recently ordered a review of the legality of the medical advice being provided. At the same time, some HMOs and other established insurers are threatening to place a court order to stop Cyber-Angel from further operation. The creators of Mv Cyber-Angel have hired legal experts to look into the ethical and legal implications of its operations. The future of Cyber-Angel is now in question.

Case Questions

- What features of Cyber-Angel distinguish it from traditional health care systems?

- How would you envision the infrastructure that supports the functionality of Cyber-Angel? What types of e-health services are most likely to be appropriate for use in Cyber-Angel?

- Do you agree that Cyber-Angel is an e-health system whose time has come? Why or why not?

- Think about the ethical and legal issues of operating a program such as Cyber-Angel. What are the most significant challenges and barriers in operating Cyber-Angel?

This case is hypothetical, to be used for discussion purposes only.