![]()

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

E-HEALTH IMPACTS ON THE HEALTH CARE AND HEALTH SERVICES INDUSTRY

Surfing the Powerful Waves of E-Technologies

Joseph Tan, David C. Yen, Sharline Martin, Binshan Lin

III. E-Technologies in Various Health Care and Health Services Sectors

A. Hospitals and Physicians' Offices

B. Nursing Homes and Home Health Care Agencies

C. Pharmaceutical and Health Care Product Companies

D. Medical Insurance Companies

IV. The Power of E-Technologies

A. Reengineered Business Processes and Reduced Administrative and Clinical Costs

B. Increased Customer Empowerment and Satisfaction

C. Strengthened Patient-Provider-Insurer Relationships

D. Enhanced Quality of Care Services and Clinical Outcomes

V. Risks in Applying E-Technologies

A. Organizational, Cultural, and Societal Impacts

B. Security, Privacy, Standards, and Legal Issues

C. Mismanagement of E-Technologies

VI. Surfing the Waves of E-Technology

A. E-Health Delivery Strategies and Support Technologies

B. Managerial Challenges and Implications

X. E-Communities Case: Scalability Challenges in Information Management

Learning Objectives

- Characterize the functions and business processes of various sectors of the health care and health services industry

- Realize the positive impacts of applying e-technologies in various health care and health services sectors

- Recognize the risks associated with applying e-technologies in health care

- Articulate the various stages of e-health evolution

- Chart the future of e-technologies in health care

Introduction

A vision of better population health and human well-being has continually motivated those in the health care field to innovate and invent new ways of applying technology. E-technologies promise to revolutionize our society, and it is this trend that has brought about the e-health care era and has contributed to the e-health paradigm shift. E-technologies have already begun to enhance various aspects of health care—for example, the ability to communicate with individuals, groups, and communities through the use of e-health records, e-public health information systems, e-networks, and Web services (see Parts One and Two of this text); our access to media-rich e-health information and knowledge through the use of complex e-consultation and e-monitoring technologies and e-health intelligence software (see Part Three); and our ability to interconnect e-consumers, e-vendors, e-providers, and other e-business entities through e-health commerce applications (see Chapters Twelve through Fourteen). Put simply, e-technologies have already significantly affected many industries, ushering in the next generation of health care—that is, the e-health marketplace.

In the past, health care providers and consumers have been slow, even reluctant to embrace e-health care applications, primarily because of the limited power and newness of e-technologies. Many stakeholders have feared that e-health could not ensure the security of health care data in general and the privacy and confidentiality of sensitive patient information in particular (see Chapter Fourteen). With new advances in cryptography and firewalls, digital signatures and certificates, and wireless security protocols, security concerns faced by the health care industry have eased significantly, and an increasing number of mainstream health care business sectors are now considering moving into e-health care. E-consumers are adopting emerging e-health applications for their many potential benefits, including increased speed and accuracy of health information exchange, lower cost of services, convenient access to media-rich e-health information and knowledge, and more efficient and effective health care decision making. Many e-consumers, for example, are demanding increasingly rapid and ready access to multimedia information and in-depth knowledge of health care in order to help them make better choices and informed decisions.

Similarly, e-providers and e-health managers are looking toward e-technologies to bring about significant reductions in costs while preserving and maintaining high-quality health care. The proliferation of electronic mail systems, the Internet, the World Wide Web, and the emergence of organizational intranets and extranets as innovative extensions of local area networks and wide area networks, as well as the introduction of various forms of e-diagnostic systems, including linked and distributed databases, e-clinical decision support systems, e-medicine, e-home care services, and e-prescription systems, have resulted in a need to understand the impacts of emerging e-technologies and applications on various sectors of health care and health services, particularly among health administrators, practitioners, and patients (Tan, 2001; Tan with Sheps, 1998). Eoffering Corp, for example, has conducted a survey that indicates that the market for e-health care services is about to explode (Fell and Shepherd, 1998). While there are no predictable statistics available for the e-health care market, the indication has been that the e-health care marketplace, when combined with mainstream health care services, has now exceeded 14 percent of the gross national product (GNP) in the United States; in addition, the possibilities of extending services to a global marketplace are also expanding (see Chapters One and Two and Chapter Twelve).

In this chapter, we explore characteristics of various traditional health care and health services sectors and examine how emerging e-technologies are affecting them. Some benefits and risks created by e-technologies are also highlighted. To accomplish this, we first present an overview of the health care and health services industry, followed by a general discussion of the impacts of emerging e-technologies on various sectors. The major characteristics, tasks, functions, traditional approaches, and potential applications of e-technologies will be factors in the discussion. Next, we focus on some potential impacts and challenges of using e-technologies to evolve new e-health businesses. We explore the growth and development of e-technologies and the managerial strategies, directions, and implications of employing these technologies in health care and health services sectors. Finally, we conclude the chapter with a brief look at potential future innovations and trends in e-technologies.

E-Technologies in Various Health Care and Health Services Sectors

The mainstream health care and health services industry encompasses various sectors, including hospitals, physicians' offices, medical insurance companies, nursing homes, and home health care agencies, as well as pharmaceutical and health care product companies. Although the characteristics, tasks, and functions of each sector differ, all the sectors share the common goal of providing consumers with health care goods and services. Each of these sectors has also evolved to its own stage of the e-health revolution. In this section, we take a look at how emerging e-technologies gradually but surely affect each sector.

E-consumers' expectations of e-businesses, including health care businesses, are continually increasing. E-health consumers are demanding the same privileges they receive from other e-businesses. With the advent of e-technologies, e-consumers have access not only to media-rich e-health information and high-speed communications but also to direct purchase of e-health goods and services. In light of increased competition among e-health care providers and heightened awareness among e-consumers, many sectors of the health care and health services industry are now anxious to use emerging technologies to meet the challenges and needs of a new generation of e-consumers, e-providers, e-insurers, e-vendors, and other e-stakeholders.

For some traditional health care organizations, harnessing e-technologies may be the only way to solve their looming financial troubles; for others, it represents new and exciting opportunities to regroup, restructure, and even expand their share of the growing global market. Either scenario provides good reasons for examining the different sectors to determine how e-technologies will change the ways they conduct their businesses.

Hospitals and Physicians' Offices

Traditionally, hospitals provide acute and, in some cases, intermediate and longer-term health care services for the ill. Most hospitals have numerous departments, including admission and discharge, emergency and acute patient care units, laboratories, radiology, pharmacy, medical record archives, and ancillary departments. Seamless networking, collaboration, data exchange, and communication among departments are important to maintaining efficient and effective managerial and operational activities.

Typically, a patient is admitted either through the hospital emergency room or directly from a referring physician's office. Except for emergencies, every admission requires pre-certification from an insurance company. Traditional pre-certification involves multiple phone calls as well as detailed preparation of insurance company paperwork. Delays are often caused by the time required for physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and social workers to record and properly code the required information. Such medical records are also confidential and as such should be retrievable only by the health professionals directly responsible for patient care. Once discharged, a patient may need continuing therapy and prescription drugs for home treatment. Often, a physician prescribes medication either by supplying a written prescription or by calling a pharmacy of the patient's choice. Either of these procedures can be very time-consuming for both health care professionals and patients.

Unlike hospitals, which are often heavily subsidized by government funding, physicians' offices are private business units whose ultimate goal is to make profits. With the emergence of managed care and new restrictions on insurance reimbursements, patients with minor needs are now seen more and more in doctors' offices rather than in hospitals. Simple medical and surgical procedures once performed in hospitals, such as the administration of chemotherapy and minor biopsies, are now frequently performed in physicians' offices. The rising demand for these services is creating an increased need for medical products and equipment at physicians' offices.

Faced with increasing pressure to reduce expenses, along with changing health care consumer expectations for greater accountability and higher-quality care and services, hospitals as well as physicians' offices nowadays are trying to cut costs while maintaining quality of services. To manage their day-to-day business activities more efficiently and effectively, both groups are turning to emerging technologies for new and innovative ways of doing business. Strategic uses of e-technologies can help achieve the goals of reduced costs and more time for patient care. To this end, e-technologies such as intranets and extranets can prove to be effective. For example, e-technologies can be used for marketing, for providing on-line scheduling information to patients, and for the exchange of information between e-caregivers and e-patients and between users and insurance companies.

An increasing number of hospitals and physicians are using the Internet as a marketing tool. According to Fell and Shepherd, use of the Internet in hospital marketing has grown from 16.5 percent in 1995 to 32.2 percent in 1998 (Fell and Shepherd, 1998; Moynihan, 1999). Web access, external e-mail, physician referral services, research, employee recruitment, and education were the main Internet-related functions or tasks used by hospitals. In addition, the study points out that 56 percent of the surveyed hospitals not currently using Internet technologies plan to do so very soon (Fell and Shepherd, 1998; Meszaros, 1996).

In addition, the study argues that e-technologies such as the Internet can be applied to provide pre-admission and postdischarge information to patients. Providing preadmission information such as instructions on preparation for surgery over the Internet could reduce the paperwork and the number of telephone calls between health providers and patients. It could also alleviate patients' anxiety and help patients make informed decisions. Similarly, discharge instructions and prescriptions can also be made available through the Internet in cases where the physician is not immediately available to write the prescriptions. This could lead to reduced costs, less paperwork, and fewer phone calls between the physician and the pharmacist or between the physician and the patient.

E-technologies can also be employed as networking tools to facilitate collaboration in e-consultation and for e-clinical follow-up services. In addition to supporting quicker and more effective decisions, these tools can provide e-health care providers with rapid access to rich and appropriate e-patient medical information. Provided that information exchange and transmission activities can be kept secure, Web services and e-health data integration services (see Chapter Fourteen) can support health care professionals in coordinating activities among providers and in exchanging critical e-patient information in a cost-effective and user-friendly fashion.

Dr. Joseph Catalano, an orthopedic surgeon at Baptist Hospital East in Louisville, Kentucky, surmises that use of the Internet to access patient information not only reduces expenses but also saves time and eliminates paperwork. He likes being able to use the Internet to check laboratory results for his patients (Benmour, 1999). With this technology available, physicians and health care providers can make quick and at times life-saving decisions because they have direct and convenient on-line access to critical patient medical information. To safeguard the confidentiality of patient information, Dr. Catalano's hospital uses encryption software that scrambles data before transmitting them. Users (physicians and other health care professionals such as nurses and laboratory technicians) are required to enter user identification information and secret passwords before any medical data can be retrieved. As reported elsewhere, encryption software has proven effective in keeping patient medical information secure and confidential.

Other uses of e-technologies include rapid access to e-patient information from referral sources, e-prescription services, e-procurement of supplies, and e-registry of new patients. For example, many products used in hospitals and physicians' offices can be purchased directly over the Internet rather than dealing with salespeople. More competitive pricing and direct connection to suppliers are strong reasons for e-purchasing, which can also result in substantially greater control over expenses and long-term time savings. Extensive ordering paperwork, valuable time spent with sales agents, and lengthy shipment delays can be minimized or, in some cases, eliminated.

Nursing Homes and Home Health Care Agencies

Nursing homes are health care institutions for the elderly as well as for those who are debilitated and need longer-term health care services than hospitals can provide. As a result of new advances and breakthroughs in medical and other life-prolonging therapeutic technologies, these institutions have gained popularity in the latter part of the twentieth century, especially among those elderly people who want to maintain a more independent form of living. Home health care agencies also provide continuing health care services to patients who have been discharged from a hospital or hospice and who prefer to be cared for at home. The introduction of managed care systems and diagnostic related groups in the pursuit of decreasing health care costs from shorter hospital stays have created a booming industry for home health care. Chapter Nine of this text is devoted to the topic of e-home care services.

Owing to the extended length of stays at nursing homes as well as the extended time that patients spend in home health care, a large number of medical records have to be maintained by nursing homes and home health care agencies to support the collaboration between the nurses, pharmacists, physical therapists, and doctors who are providing patient care. Traditional means of communication among these health providers are telephone calls, faxes, or hard-copy memos. These types of communication often cannot be completed in a timely fashion, prohibiting quick decisions. These methods may also involve extensive amounts of paperwork.

Like other health care and health services sector businesses, both nursing homes and home health care services can make good use of e-technologies to increase efficiency and effectiveness. For example, the Internet or other e-technologies can be used to send e-mail messages and to directly link computer systems in order to transfer e-patient data. Nonetheless, use of e-technologies by these operations needs to be well planned, controlled, and monitored. A nursing home or a home health care agency operating under contract with the U.S. government is subject to the Privacy Act of 1974, which imposes limitations on the disclosure of medical information collected by government agencies. In addition, the Health Insurance Portability and Accessibility Act of 1996 places further restrictions on the disclosure of patient information (see Chapter Fourteen). Many Canadian provinces and U.S. states have additional laws regarding the distribution and disclosure of medical records and other health care information. Hence, nursing homes and home health care agencies not only face the challenges of complying with medical record security, privacy, and confidentiality requirements but risk losing federal and managed care revenues and may also incur fines if their e-security measures prove improper or inadequate.

The trend toward quality home health care is on the rise as a result of the increased cost of traditional health care and the higher life expectancy rate associated with medical and technological advances. Home health care professionals travel to patients' home settings to provide health care services. Removed from the traditional corporate infrastructure, a home health care provider faces unique challenges. In order to provide quality care, home health care providers must be able to conveniently access patient information when needed, capture admission assessments, and collaborate with other health care team professionals in a timely and effective manner. They must also be able to stay in touch with their supervisors or managers in order to ensure that appropriate actions are taken and the appropriate people are kept informed. E-technologies can provide effective solutions. According to Nugent (1999), “Internet-based technology will provide the necessary infrastructure for health care professionals to access data warehouses, data marts, HEDIS, reporting tools, and data mining systems.” In other words, home health care workers can take advantage of e-technologies to access critical patient data when needed, transmit patient information, and connect with supervisors or managers to identify best actions and practices for complex situations requiring immediate action.

Pharmaceutical and Health Care Product Companies

Pharmaceutical and health care product companies provide health care products to hospitals, physicians, and patients. The primary role of these companies involves new product research and product sales. Traditional business-to-business (B2B) and business-to-consumer (B2C) sales in the health care industry are done with telephones, paper, and faxes or in drugstores and through personal sales. Product advertisement and education of potential customers in regard to products is typically done through television, newspapers, and magazines.

E-technologies provide new sales solutions for pharmaceutical and medical product companies, many of which are detailed in Chapter Twelve. For instance, with a simple mouse click, patients and health care providers can obtain product information and purchase products on-line. Within the health care industry, B2B and B2C revenues due to on-line marketing and e-operations are predicted to rise significantly over the next several years due to revenues from e-operations.

While using e-technologies has distinct advantages for pharmaceutical companies, some disadvantages and unsafe practices are also associated with these applications. For example, Pill Box Pharmacy, a popular Internet pharmacy, allows visitors to order medications such as Viagra, Propecia, and homeopathic drugs on-line. Visitors connected to the Pill Box Pharmacy Web site can seek an on-line prescription by linking to Medical Center Net; a doctor employed by that Web site approves or declines a prescription based on the customer's answers to a preset questionnaire (Weber, 1999). This practice provides potent medication prescriptions without physically evaluating patients. Pamela Gemmel, a spokesperson for Pfizer, the manufacturer of Viagra, has stated that the company does not support such on-line prescription of medication (West, 1998).

Medical Insurance Companies

Medical insurance companies, which provide insurance coverage for health care consumers, are major stakeholders in the health care and health services industry. Insurance companies pre-certify a patient's eligibility for medical and clinical procedures. For example, they determine the length of stay that hospitals will be compensated for, compute payments to different parties, and dictate which health services particular patients are entitled to receive under their insurance plan. Because the major functions of medical insurance companies are to provide insurance coverage, decide on the length of stay for a given diagnosis, and compute reimbursement according to specific coverage plans, the medical claims filing and claims reimbursement process require a considerable amount of attention and validation. Traditional communications among the medical insurance company, the patient, and the health care provider involve phone calls, faxed information, and mailed correspondence. Manual paperwork can be very time-consuming, so these approaches usually result in longer response times than a direct electronic data interchange connection. E-technologies can provide on-line information about eligibility, benefit status, out-of-pocket expenses required, and procedure pre-certification. These resulting increased operational efficiencies will in turn translate into greater clinical effectiveness. Thus, use of these e-technologies can not only can significantly reduce costs and processing time but also simultaneously improve the quality of health care delivery.

Until recently, on-line transmission of Medicare claims was not legally permitted. In 1998, however, the Health Care Financing Administration provided directions to providers on how to maintain and transmit medical data electronically (Moynihan, 1999).

![]()

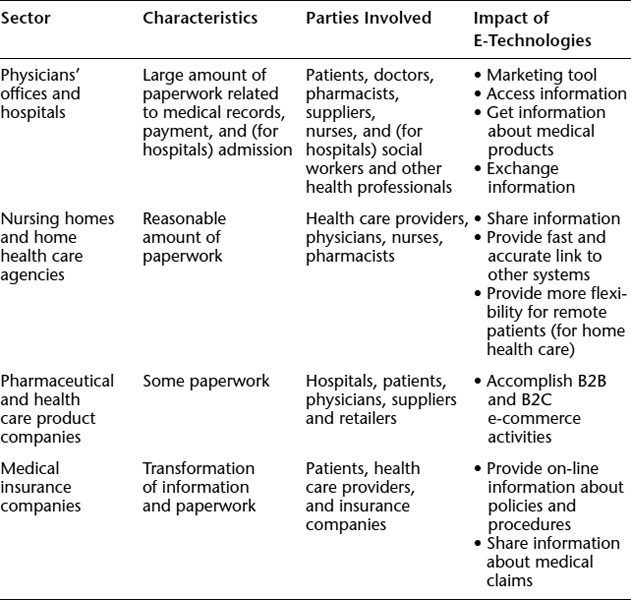

Table 15.1 details the major characteristics and stakeholders involved in the different health care and services sectors and outlines how e-technologies will affect these sectors.

Our discussion on the task characteristics and uses of Internet technologies across the various health care and health services sectors brings us to two key questions: (1) What impact will e-technologies have on traditional health care? (2) What are the challenges in applying e-technologies to health care? We begin with the impacts of e-technologies on health care.

The Power of E-Technologies

Strategic use of e-technologies creates a competitive advantage for health care organizations and providers by offering the potential to lower costs, improve consumer satisfaction, increase quality of care, and strengthen consumer-provider relationships. In addition, employers that apply e-technologies successfully can expect to improve efficiency, create new opportunities, and provide more effective programs for employees in terms of decreased absenteeism and increased productivity (Wilkins, 1999). Other advantages include faster and more convenient access to health care services for the disabled, for remote and isolated patients, for the elderly, and for underserved rural, urban, and inner-city populations.

TABLE 15.1. E-TECHNOLOGIES IN VARIOUS SECTORS OF THE HEALTH CARE INDUSTRY

We have seen that e-technologies such as e-medicine (Chapter Eight), e-home care services (Chapter Nine), e-diagnostic decision support (Chapter Ten) and e-health intelligence (Chapter Eleven) will enable e-health care consumers to participate much more in managing their own medical records and health needs. E-patients, regardless of their mobility status, will be able to access the finest health care systems and the best e-care providers in the world simply by traveling either physically or virtually to an e-medicine-enabled hospital or health research center.

The e-health paradigm shift is changing the concept of health care. Whereas in the past, patients had to travel and wait to see a care provider before health care services could be rendered, with the help of e-technologies, expert clinical information and knowledge from many sources can now be transferred to the patient either directly or through an intermediary (such as an on-line physician). For instance, emergency services can be rendered to a traveling patient in a different country with data captured in smart cards carried by the patient or extracted real-time from a relevant database stored in the patient's home country. This powerful concept promises to revolutionize the business functions and characteristics of the mainstream health care and health services industry. Already, e-consumers are providing their physicians with research information on their diagnosed illnesses, as well as alternative therapeutic solutions that they have learned about via the Internet and other e-technologies. Moreover, e-patients are shifting attention to preventive care and lifestyle changes rather than concentrating on curative treatments. Coile and Trusko (1999) predict that “Internet-accessible information may reduce the potential demand for health services by the baby boomers in decades ahead. It could also result in a dramatic decline in demand for acute care services, as a healthier lifestyle kicks in and life expectancy jumps unexpectedly.”

A number of generally positive apparent impacts of e-technologies on current health care services and business processes have been reported:

- Reengineered business processes and reduced administrative and clinical costs

- Increased customer empowerment and satisfaction

- Strengthening of patient-provider-insurer relationships

- Enhanced quality of care services and clinical outcomes

All sectors of the health care industry, including profit and nonprofit health care stake-holders, providers (for example, hospitals), payers (for example, insurance companies), employers, practitioners, public health officials, educators, system developers, consumers, and others must be prepared to face significant changes. Both health care and computer professionals, for example, must be aware of how changes in the use of e-technologies will affect them both as facilitators of the development of these applications and as health care consumers. As a facilitator, one must examine the design and development of applications in order to capture, organize, store, rationalize, and present health information in new ways; facilitate the replacement or integration of existing processes and systems with emerging technologies; and the manage new technologies and integrated systems. As a consumer, one must keep confidentiality, ethics, privacy, and security; usability; and political and societal impacts in mind. We will explore some of the more beneficial impacts of e-technology in the following sections.

Reengineered Business Processes and Reduced Administrative and Clinical Costs

At the very least, health care providers and other stakeholders can begin to reduce administrative and medical costs by improving work flows and significantly reengineering inefficient and costly business and administrative processes. This is an inexpensive and low-risk way to make good use of emerging e-technologies. For instance, the World Wide Web can be used to coordinate otherwise time-consuming and complex communications between e-consumers and e-providers in place of fragmented paper trails and time-consuming chains of phone messages. Many health care organizations are also allowing patients to do their own scheduling and appointments on the Internet. Intranets and extranets provide significant enterprisewide communications, including prior announcement and dissemination of intended changes in policies and processes that require substantive input and participation from employees. This method efficiently and effectively tests reactions and feedback without direct confrontation. Costs associated with postage, paper, long-distance telephone bills, meetings, personnel, and unnecessary processes can all be eliminated through the use of e-technologies to streamline administrative operations.

According to Healtheon CEO Steve Curd, time wasted on the phone in the health care system costs $200 to $300 billion annually (Delevett, 1999). Curd further estimates that a telephone call with a simple question costs an insurer $4 when overhead costs such as salary and rent are added, whereas the Internet can handle the same transaction for a small fraction of these costs. In a case example reported by Raghupathi and Tan (2002), an Internet-enabled patient record system installed by a practice with 26,000 patients in four clinics (Cabarrus Family Medicine in Concord, North Carolina) frees up time for the patients, residents, physicians, and their secretaries. Cabarrus doctors were spending about 40 percent of their time sifting through paper-based patient records. With the e-technology in place, physicians and residents can access medical records quickly, using standard browser technologies. Although we do not know how much storage space is being axed, the paperless system probably also resulted in a substantial cost savings on annual rental of physical space for storage of paper-based records.

On the medical side, e-medicine, videoconferencing and Web services can decrease the number of nurses' and nurse's aides' visits required in home health care settings, thus effectively reducing labor costs. Virtual visits can be prescheduled on a regular basis, for example, to ensure that the patient suffering from a chronic illness such as lower back pain will follow-up on instructions pertaining to pain medication and other therapeutic procedures (for example, regular stretching exercises and healthy lifestyle behaviors).

Medical cost savings can also be obtained by educating consumers about prevention and self-management of chronic diseases. Health care Web sites on the Internet and kiosks installed in public places can provide useful information and can educate patients about early symptoms, thus encouraging e-consumers to seek early medical attention and to use appropriate health care resources. The same technologies can also be applied to e-health promotional programming (see the case in Chapter Three). Some have pointed out that prevention and “early detection [are equivalent to] … less intensive, more appropriate treatment, [and which, in turn] … translates into lower costs” (Deckmyn, 1999; Wilkins, 1999).

Health care consumers can take an active role in the treatment process by making use of Internet-based self-care treatment plans. In this sense, patients can conveniently co-manage their own diseases on-line with health care professionals. It has been noted that through use of early and frequent e-mail communications, automated treatment reminders, and shared on-line resources patients can co-manage their own diseases on-line with health care professionals through early and frequent communication via e-mail, through automated treatment reminders and through sharing of online information (Shaffer, 1999; Wilkins, 1999). E-patients who have difficulty in using e-technologies can work with an intermediary. Today, many elderly patients have grandsons and granddaughters who will show them how they can learn to use the Internet and experience intergenerational programming (where the younger generations are working alongside the older generations in the use of Internet software), and through this, a better social link between these generations has emerged, as demonstrated in the case discussed in Chapter Three.

The use of new technologies often promises to increase the efficiency and productivity of workers. Although workers may feel stressed by the compressed time frames that result from electronic work techniques before they have a chance to adapt, many of them have been willing to learn the new trade with the understanding that the Internet is here to stay and computing skill is an essential for daily living. In other words, people are expected to do the same or more work as workers refuse to do more than they expect and ask for more money, with technologies serving as “substitute workers.” It is believed that over time, as people adapt to new technologies, new ways of doing things will further increase the limits of growth of e-technological applications. New procedures and new capabilities may also combine to evolve completely different forms of business. Chapter Twelve illustrates how many traditional brick-and-mortar organizations are moving into e-businesses and how this move creates hybrid models of e-commercialization in health care.

Increased Customer Empowerment and Satisfaction

Apart from affecting professional e-health care providers, e-technologies can empower e-consumers to access information about their illnesses and ways to treat themselves. In a related area, e-consumers can also obtain support from other non–health care professionals—for instance, others with the same illness. Patients with chronic diseases such as cancer, diabetes, and AIDS can draw support from other patients with similar illnesses through Web chats, on-line support groups, and newsgroups. Ultimately, this will enable and empower these e-patients to understand their illness, the associated symptoms, and the treatment alternatives. It will also allow the patients to view the physical and emotional effects of the disorder through the eyes of someone else going through a similar experience. It has been claimed that “among the most powerfully supportive experiences for patients and caretakers is the sharing with others who have already ‘been there’” (Wilkins, 1999).

Educating and empowering e-health care consumers through on-line information enable them to become active participants in their own health care, thus potentially resulting in higher satisfaction. Making information and networking tools available and conveniently accessible allows health care consumers to participate in planning their treatment regimen and to compare notes with others. This may further enhance their trust in e-health providers, perhaps enough to allow them to share previously hidden concerns with their practitioners. Moreover, reduction of emergency care, acute care admissions, and unnecessary visits to the doctor will save the health care system a significant amount of money.

Wilkins observes that “[i]t is becoming more common for patients to supply for their physicians with the latest disease research and treatment gathered over the Internet” (Wilkins, 1999). A new generation of educated consumers feels it is not only their right to discuss their health conditions with their physicians but also their responsibility to challenge their physicians to stay current regarding of new treatments and procedures. Thus, knowledge gained through proper use of e-technologies is enabling an evolving open dialogue between providers and patients. Over time, if such a dialogue results in positive interactions, not only will a stronger provider-patient relationship evolve, but both the patient and the provider will be able to feel comfortable that the patient is in control of his or her own health management. Again, this will result in higher patient satisfaction.

In addition, patients will be more satisfied when they can get answers to general health questions with a mouse click rather than having to travel, wait in line, and spend a copayment fee. Many e-consumers are already using on-line banking and e-bill payment and thus have mastered the skills they need to fill out e-claims for medical expenses and to e-schedule physician appointments. When patients can manage claim forms for themselves, not only are they empowered, but providers and insurers also realize huge cost savings.

Strengthened Patient-Provider-Insurer Relationships

Many examples that were previously mentioned will combine to promote and strengthen patient-provider, provider-insurer, and patient-insurer relationships. Hence, in this section we need only to briefly lay out a few typical examples. When a patient walks into a physician's office, the clerical or nursing personnel typically have to call the insurer to determine the patient's eligibility and which treatments are covered. Healtheon Corporation, a company based in Santa Clara, California, is marketing an Internet-enabled system that gives physician's offices immediate access to such information (Delevett, 1999), allowing verification procedures to be simpler and more efficient.

Once the physician has rendered a service, it usually takes weeks or even months to get insurance reimbursement because claim forms and procedures are designed for manual processing, which often takes a significant amount of time. By processing e-claims through secured e-technologies, e-providers will eventually speed up the payment process. The same applies to e-consumers who claim medical expenses incurred during travels or other emergency situations. The resulting efficiencies will enhance and strengthen patient-provider-insurer relationships. Indeed, the rapport among these stakeholders is key to the success of health care service providers. A key reason why consumers switch providers or health insurers is the lack of efficient and effective service on the part of the provider or insurer. The costs for the insurer or provider when a patient moves are enormous in the long term.

Providers, insurers, and patients can all be kept in close contact with one another through the use of e-technologies. For example, if a new screening procedure for colon cancer or a new treatment for hair loss is approved by an insurer, both providers and patients can be alerted and services quickly made available for appropriate patients. Posting these announcements and alerting the respective providers and patients effectively serves as a marketing effort for the insurer.

An insurer can use e-technologies to match patients with providers and encourage e-patients to provide feedback on their experience with those providers, allowing the insurer to develop data to help decide whether to renew a particular provider's contract when it comes due. Not only would such on-line evaluation enhance the patient-insurer relationship, but employers (who often pay a significant portion of the health care costs of their employees) would also benefit from a more productive and less dissatisfied workforce and fewer days lost to illness. E-technologies that can be used to strengthen patient-provider-insurer relationships include e-mail, on-line chats, postings on bulletin boards, organizational extranets, community networks, and mobile health care technologies such as wireless bedside PDAs.

Enhanced Quality of Care Services and Clinical Outcomes

Historically, information related to the development of a disease, as well as the risks and benefits of treatment, was not easily available or accessible to health care consumers. With advances in e-technologies, however, today's e-consumers can educate themselves about risks and benefits of alternative treatment options for particular illnesses.

An informed and educated consumer is likely to participate actively in his or her own treatment plan. As we have noted, this tends to create higher consumer satisfaction with regard to treatment outcomes. E-technologies also allow e-consumers and e-patients to choose their own physician or hospital and to check on the status of their insurance coverage on-line. Given what we know about the mind-body connection, autonomy in consumer decision making is likely to aid in achieving favorable medical outcomes for patients.

While any e-technology by itself cannot turn water into wine in terms of providing cures for sick patients, e-technology is a significant tool in the health care process. High-performing health organizations generally are managing these technologies better than other organizations (see Chapter Thirteen). This is why some patients prefer to be treated in one facility rather than another. Patients also seek physicians who use technologies appropriately and intelligently. Indeed, many chiropractors, physical and occupational therapists, and even acupuncturists are turning to the use of e-technologies to differentiate themselves from their competitors. How best to use e-technologies to achieve improved quality of care services and enhanced clinical outcomes is still a matter for further research and gaining further expertise, but at the very least, patients are impressed by the image of competence, efficiency, and responsiveness projected by e-health care providers and are spreading the word about their positive experiences.

Risks in Applying E-Technologies

Risks associated with applying e-technologies in health care and health services include the following:

- Organizational, cultural, and societal impacts

- Security, privacy, standards, and legal issues

- Mismanagement of e-technologies

Organizational, Cultural, and Societal Impacts

Some organizational, cultural, and societal impacts relate to potential job losses in traditional health services fields as a result of the changes needed to integrate e-technologies, including structural changes in the industry leading to closures of hospital beds and traditional health care organizations, changes in roles and responsibilities, redesign of mainstream health care systems leading to changes in funding and investment directions, and redesign of traditional work definitions.

Individuals, groups, organizations, communities, and society in general will respond differently to the introduction of new e-technologies, depending on their underlying culture and belief systems. For example, when hospital administrators are forced to cut their budgets, they most often believe that clerical personnel and middle managers should be laid off because clerical and administrative workload can better be reduced with the use of computers than can physician and specialist workload. If a corporate intranet is to be installed, nurses and nurses' aides will have to be trained to use it, but physician training may have to wait, although physician training is often a more sensitive issue than that of implementing a nursing training program. If physicians refuse to use the networks, it is often assumed that the interface provided for them is not good enough and that some other specialized technologies may have to be put in place. Hence, the social and cultural dimensions of professional acceptance or resistance are key factors in any e-health technology project.

Similarly, when a health care organization attempts to install an e-prescription system, pharmacists may fear that having physicians e-prescribe the appropriate drugs for their own patients may diminish the pharmacists' role, which may not be acceptable to the organization or to both the physician and pharmacist groups. Such changes touch on the social and cultural fabric of the organization because when physicians order manually, the organization can hold the pharmacists responsible for checking the appropriateness of the medication and ensuring that the correct dosage or medication is being ordered. Furthermore, even if such a change takes place, resistance may surface later, perhaps in the form of concerns over patient safety and quality of care, so that the change becomes difficult or impossible to implement. In contrast, it is easier to create a direct link between a pharmacy chain and a doctor's office, because the role of the pharmacist will not be affected.

The same notion of the cultural context for acceptance of e-technology applies in major corporations. For example, if a corporation wanted to make ordering prescriptions on-line mandatory for a group of retirees, major resistance and political lobbying might be encountered because some retirees would not be ready to go on-line. They would prefer to visit their local pharmacies, gaining assurance from those whom they have trusted for years and discussing dosages and alternative prescriptions face to face. Many elderly patients also do not like having to remember a series of passwords and policy identification numbers and fear being kicked out of the system for not doing it correctly. They are also fearful of security and privacy violations, because of the many horror stories that they have heard over the years. Conversely, if the system were to be presented to newly hired school teachers, the reaction might well be different, given the group's likely experience with the Internet and also their intense time management issues.

In general, the experiences of traditional business during the evolution of e-commerce and e-business initiatives are expected to repeat themselves in traditional health care services as they evolve into the e-health care era. Some suggestions on how to avoid the cultural pitfalls such as those that have been described include running parallel systems rather than an outright automation, having an evaluation component to study and guide the e-technology implementation process, and generous use of multiple consultants in the beginning stage to better managed the transition process. Some organizations will outsource many of the technologically advanced functions until the organization has built enough in-house expertise. However, barriers involving security, privacy, standards, and legal issues are expected to keep the e-health revolution from accelerating at this time.

Security, Privacy, Standards, and Legal Issues

As discussed previously, the many positive changes brought about by e-technologies have been accompanied in some cases by user resistance, fear, and anxiety; violations of security, confidentiality, and consent; issues regarding the legality of e-health practices; concerns about privacy and ethics; issues brought on by a lack of standards and standardization; issues of data validity and identity authentication; and concerns about potential misuse, misinterpretation, and mismanagement of electronic information sources.

Data security and patient information confidentiality, two of the most important concerns about applications of e-technologies in the health care and health services industry, are discussed in detail in Chapter Fourteen. According to the American Medical Association (AMA), individuals or agencies can legitimately access confidential medical data only with bona fide intent. To enhance digital and electronic data exchange for health care services, the AMA has developed guidelines for imposing stringent security procedures to prevent unauthorized access to computer-based patient records (Meszaros, 1996). Chapter Four also discusses these issues in regard to how they affect electronic health records. In this section, we briefly review some of the security requirements and solutions.

Electronic access is typically controlled through the use of passwords, software encryption of information, or other means such as scannable bar-coded badges. To use e-technologies for health care and health services effectively, it is important to define who will be granted access and what level of data the patients will be allowed to access. Although data security and confidentiality of patient information are the biggest challenges, software solutions have emerged to tackle these challenges. Encryption software uses complex mathematical algorithms, or keys, to encode a message, thereby ensuring that only a computer using the same keys will be able to read the message. An encrypted patient record sent via e-mail, for example, would appear to be gibberish to an unauthorized user who opens the e-mail. This safeguards the confidentiality of patient information and helps to ensure data security. In another approach, firewalls combine hardware and software to separate an internal computer system from the outside world. Firewalls usually require passwords or codes embedded in specific computers to grant access to the protected system.

Lack of standards also fuels user resistance to e-technologies. While the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, passed in 1996 (see Chapter Fourteen), made some progress in establishing standards, the difficulty of implementing common software without compatibility standards and the tedious process of achieving standardization among major stakeholders are obstacles to the effective adoption of e-technologies in health care.

Mismanagement of E-Technologies

Another major risk category in implementing e-health technologies has to do with mis-management of e-technologies. According to a survey by the Northeast Chapter of the AMA, “only 14 percent of physicians would recommend the Internet as a medical information resource for patients” (West, 1998). This attitude is attributed to the fact that physicians believe that consumers will be unable to distinguish high-quality information from poor-quality information on the Internet. Since virtually anyone can post information on the Internet, it is sometimes difficult to separate scientific medical information from not-so-scientific claims. Further, the potential for misuse of information (such as that in patient records) that is collected and then made available via the WEB is another major concern.

In Chapter Thirteen, we discussed the management of e-technologies as a key to organizational success in harnessing the power of these technologies. Among the difficulties encountered by organizations are lack of leadership to oversee the growth and development of appropriate e-technological applications within health organizations. Unfortunately, many traditional health care administrators are hesitant to invest in e-technologies because a number of major hospitals and corporations have suffered major implementation failures and losses in trying to move on-line (see Tan with Sheps, 1998). In addition, health care organizations often lack technological expertise because it is difficult to find people with the appropriate technical skills who are also familiar with health care systems. The history of health care computing in Chapter One testifies to the risks associated with new technologies.

Surfing the Waves of E-Technology

Despite all the risks of potential mismanagement of e-technologies, expected consequences in terms of moving toward new business models, a more efficient and productive workforce and greater consumer empowerment and satisfaction warrant our continuing attention to the growth and development of e-technologies in health care. Two important questions arise from our foregoing discussion about e-technologies:

- What key functions need to be computerized or transformed in order to best capitalize on the power of e-technologies?

- What stages must such a transformation undergo before it can be considered complete?

With respect to the first question, we feel that e-technologies can contribute most significantly to two major domains and applications: (1) organizational management functions and internal operations, and (2) e-consumer needs and e-provider roles and responsibilities.

The crucial functions to be automated for organizational management functions and internal operations include patient care management, patient records management, administrative and practice management, insurance claims processing, supply chain relationship improvement, medical applications and services integration, and better matching of service with marketing demands. A simple example is the use of electronic health records (see Chapter Four) in which clinical and financial information can be integrated via e-networks and other e-technologies (see Chapter Six) to help make strategic and operations planning and resource allocation decisions as well as to facilitate patient care management and insurance claims processing.

The market for health care services is generally determined by the participation of health care providers and consumers. With e-technologies, e-consumers (that is, customers) will become more aware of trends in health care and ways to evaluate the state of their health. They will have better means of preventing illness and will experience greater personal empowerment because they will have access to medical information and knowledge. E-technologies also promote many other possibilities, for example, self-care, sharing of remedial actions among e-communities, better use of available on-line resources, and greater competition in the health care marketplace.

In addition to educating e-health consumers, the aggregation of professional content will be on-line as a resource used to educate medical professionals such as doctors, nurses, and hospital administrators and will provide greater accountability among these practitioners in achieving the goals of evidence-based medicine. Ultimately, evidence-based medicine will improve the primary purpose of the on-line educational component and help delineate measures for benchmarking best practices, thereby leading to a more credible performance evaluation of e-providers. Thus, adopting e-technologies can enhance professional career development and development of new competencies through continuing education, job redesign (by working and collaborating on-line), new hiring opportunities as a result of new skill development, credential renewal and audit, and professional certification. E-technologies change the roles and responsibilities of the e-providers beyond just on-line or continuing education as a new system of health care services is being engendered.

With respect to the second question we raised, we believe that three stages of e-technology development occur during its implementation in health care: (1) the information-focused stage, (2) professional services–focused stage; and (3) marketing integration–focused stage.

The earliest form of e-health care, the information-focused stage, typically begins with automating such tasks as acquiring, regrouping, and consolidating relevant medical information based on the ability of e-technology to interconnect different communities of consumers and professionals who intend to share, obtain, access, and use the information. In this stage, health care sectors attempt to make use of the virtual information flow, aggregate similar information, redistribute the information in a different form, and construct a substantial infrastructure for the information. One goal is to generate revenues so that these applications can become self-sustaining or even become profitable. We call this stage of e-health evolution informating e-health care.

In the professional services–focused stage, the health care sectors leverage their existing base of customers, consumers, and skills through the use of e-technologies in order to offer a broader portfolio of e-medical services by integrating their products and services with other partnering e-health care providers. Experience with e-technologies in the first stage can evolve new strategies for engaging in partnerships with other e-businesses. This represents an expansion of traditional isolated services into a more comprehensive and aggregated health care management or service delivery mechanism. We call this stage of e-health evolution e-servicing e-health care.

In the final stage of evolution, the marketing integration–focused stage, we envision a number of health care sectors forming a market-oriented strategic alliance to gain a significant competitive advantage. Several sectors are improving insurance claims processing, on-line patient management, electronic patient record management, automated facility management, and hardware and software integration and development by linking private clinics, research centers, nursing homes, pharmaceutical companies, and hospitals together via e-technologies. E-technology allows the network of e-stakeholders to share resources and information. The Internet and the World Wide Web are ideal platforms for the communication and dissemination of useful and accurate information. These technologies can provide cost-effective, timely, and specific e-health information to users on a global scale. In this way, e-health services can become global and ubiquitous. We call this stage of e-health evolution globalizing e-health care.

Given the gradual evolution of e-health and the pervasive power of e-technologies, there is a need to understand managerial e-health delivery strategies and supporting technologies further in order to link e-technologies for isolated rural and inner-city users into the global electronic health village, despite learning, language, geographical, and cultural barriers.

E-Health Delivery Strategies and Supporting Technologies

A key e-health delivery strategy is to place greater emphasis on on-line health information education and training. We believe that the new generation of e-consumers will be more educated, aware, and interested in charting their own course of health. This trend reflects many factors, including dissatisfaction with the current medical system, advances in health computing technology, and a shift in emphasis from the traditional view of the health care provider as the authority on treatment decisions to the empowerment of the e-consumer as the informed decision maker.

This shift in authority from provider to consumer calls for a new type of partnership, one in which e-providers and e-patients learn to make mutually agreeable decisions. To ensure success, convenient access to relevant and high-quality e-health care information via e-learning is critical. Indeed, for e-consumers, greater access to high-quality e-health information is itself a form of medicine (sometimes referred to as information therapy). The goals of information therapy include increasing the health knowledge of e-consumers, providing assistance with self-care, and giving e-consumers the ability to manage their own health care. Each of the communication components of the Internet—including bulletin boards, e-mail, Internet chat groups, Web security and Web data aggregation services, and the World Wide Web—provides a solution for better delivery of e-health care information to e-consumers. The bottom line is that these technologies offer access to a wealth of media-rich e-health information in an affordable, accessible, private, and convenient manner.

E-commerce is also a major force in changing the e-health care system (see Chapter Twelve). For example, IBM, as a leader in electronic commerce and computing technology, is developing an Internet-based health network known as HealthVillage. HealthVillage is an on-line community composed of patients, clinicians, health management professionals, and health organizations. It uses Internet technology such as e-mail, moderated electronic chats and forums, and Web browser tools. HealthVillage aims to offer high-quality health information and services in a personalized, comfortable, and manageable way. Its appeal will be based on several virtual Internet applications, including the HealthVillage Library, the Time-Life Medical Center, the Village Square, the Mall, and Member Services.

The HealthVillage Library is a user-friendly virtual library where the consumer can access current health information news through periodicals, journals, and references. This Internet-based library will have the capacity to run global searches and link the consumer to existing public information databases around the world. The Time-Life Medical Center provides consumer-oriented information designed to educate the user on health issues ranging from childhood asthma to coronary artery disease, diabetes, and depression. As a part of HealthVillage, the center will offer comprehensive diagnostic information for new patients and family members.

The Village Square works like a newsgroup in that key events and village news can be posted, and the square provides a virtual meeting place for health consumers to engage in informal dialogues on topics of mutual interest. More formal discussions coordinated by a health professional can also take place. At the Mall, consumers can purchase health-related products, such as books, fitness equipment, health food, home health nursing, and nonprescription pharmacy products. Finally, Member Services offers consumers customized “offices” within HealthVillage that allow access to personal information such as their benefit plans and health status information. Physicians and health care organizations can communicate with individual health consumers via these virtual offices and introduce specific programs or services (solutions.ibm.com/healthcare).

Other e-technologies can include hybrid strategies (see Chapter Twelve); complete on-line courses on particular health-related topics, either run independently or as part of a total degree program; virtual meetings; and on-line seminars, workshops, and conferences. Virtual reality is also a particularly interesting means of letting users participate in e-health evolution and solutions. This topic is the subject of Chapter Sixteen.

Managerial Challenges and Implications

The evolution of e-technologies as part of the health solution for the future also faces some challenges. For example, these technologies have been shown to be more readily accessible to those in better social and economic conditions and thus may work against the concept of equitable and universal health care by further dividing the population into those who have access and those who do not (see Chapter Eight). A further concern is the quality of the e-health information being disseminated via some of these technologies, particularly the Internet, and the difficulties of regulating or validating information quality. Ultimately, the user (typically, the e-consumer) has the responsibility of separating high-quality and credible information from inaccurate and unreliable information.

Given the likely changes in future e-technologies in health care, one important question is how these changes will affect management challenges, the definition of new roles and responsibilities, and the overall implications for all of the targeted users, from clinicians and technical operators to technical executives, administrators, and managers to policymakers and consumers (patients). The clinicians and technicians will be concerned about changes in their workplaces and work responsibilities that may be brought about by the introduction and use of e-technologies. As a group, they are more inclined to adopt a technological perspective on information and communications technology (ICT) and change. Health executives, administrators, and managers will generally see e-technologies as a change agent for improving the effectiveness of decision making and organizational problem solving. Since they are more interested in fitting the technology to organizational needs, they tend to adopt an organizational perspective on ICT and change. Finally, policymakers and patients are more concerned with how e-technologies in general will be adopted and will evolve over time; these people will be motivated toward a sociotechnological perspective of ICT and change.

Although different terminology has been used, these three perspectives are clearly recognized in both health computing and information technology management literature. The impact of these differing perspectives on future managerial implications and challenges will be highlighted by again using the example of IBM's HealthVillage.

From a technological perspective, the application and use of HealthVillage technology could drastically change the way that health professionals and clinicians practice health care. By becoming a paid subscriber to this on-line service, a professional would be able to reach new clients and perform services without being impeded by geographical distance and time zone differences. In theory, a clinician could even do away with costly physical offices, a regular schedule, and much paperwork. Groups of professionals could form partnerships via a virtual referral network. All they would need would be a virtual storefront, from which they could provide efficient and coordinated services that would distinguish them from their local competitors.

From an organizational perspective, HealthVillage technology would allow organizational needs to be met in new ways via the use of e-technologies. Health executives and managers, to make this new form of health technology work for them, would need to make a paradigm shift to allow e-work, e-management routines, virtual meetings, and a new generation of e-workers who would behave very differently and have very different expectations from traditional workers. New means of partnership formation and collaborative ventures would also define new roles for e-health managers and e-health executives. Meeting organizational needs in such an environment would require a flexible, adaptable, and revolutionary management style that would go beyond traditional ways of negotiation, policymaking, casting of votes in person, analytical problem solving, individual attention to details, and decision making.

From a sociotechnological perspective, the application and use of HealthVillage technology would mean a movement toward an integrated, virtual, community-based e-health care. Maintaining the ideals of equitable and universal health care has been a particular challenge for policymakers, especially in a multi-tiered health care system such as the United States and HealthVillage technology promises to ease that challenge. Medical information and knowledge would proliferate and become accessible at a fraction of the cost of accessing the same information traditionally. Empowered consumers would be expected to play new roles in making decisions regarding their own health and well-being. Those who still had not learned to use the new information technology would feel pressure to do so, and those who had learned it would find enormous growth in the amounts of information, knowledge and expertise that could be gained or accessed.

Given the preceding analysis of the different perspectives on the use of e-technologies for different stakeholders in the health care system, it is important to recognize the emergence of the self-learning and intelligent organization to meet future challenges in health care (see Chapter Three). According to Burn and Caldwell (1990), an intelligent organization has the following characteristics: (1) it centers on learning, (2) it promotes advanced technologies for decision support, (3) it encourages collaborative efforts among individuals and groups, and (4) it is information literate. These characteristics effectively integrate the three perspectives, providing a balanced approach to the managerial challenges that are likely to be posed by future e-technologies.

Conclusion

E-technologies have transformed many lives in today's society. With a simple mouse click, many e-consumers and e-providers are now able to enjoy the efficiencies these technological breakthroughs can provide—for instance, the ability to obtain a wealth of information or facilitate easier and faster individual-to-individual contacts, individual-to-group or individual-to-organization communications, group-to-group networking, or even B2B and B2C information exchange through e-mails, listservs, and other on-line and e-commerce applications.

Today's e-health care consumer demands quality care at a low cost. As a result, various sectors of the health care and health services industry are embracing e-technologies to provide more efficient work flows and reduce time lags in services and administrative processes. Using paper, telephones, faxes, and mail to transfer patient medical data from one facility to another, make diagnostic information available to patients, and organize collaborative activities among various stakeholders such as hospitals, insurance companies, physicians' offices, and nursing homes normally results in time lags. In contrast, e-technologies efficiently and effectively support these tasks, eliminating many of the time lags. As we have seen, coordinating activities among e-health care professionals via e-mail, ordering medical products through e-procurement software, providing on-line prescriptions through e-prescription applications, and accessing patient data instantly via mobile handhelds are some of the ways that e-technologies can be used to change the landscape of health care and to benefit the various health care and health services sectors.

As a result of using e-technologies, many health care and health services sectors are beginning to acquire a competitive advantage. Recent developments in data security have provided an impetus for traditional health care to gradually embrace new technologies and for e-health care to flourish. The increasing benefits of adopting e-technologies opened the eyes of an increasing number of traditional brick-and-mortar health care institutions at the end of the last century, and further innovative applications of these technologies can be expected in the current century. The trend appears to be toward e-health, e-consumers, e-physicians, e-insurers, e-vendors, and e-clinical care services.

Chapter Questions

- Why is the power of e-technologies so pervasive? Give concrete examples of applications of e-technologies throughout the various sectors of the health care and health services industry.

- How do e-technologies affect traditional health care providers, including physicians, nurses, health administrators, and patients?

- What is meant by patient empowerment? Can the use of textbook knowledge rather than Internet knowledge empower patients? If so, why should patients use the Internet?

- Differentiate informating e-health care and globalizing e-health care, and articulate your vision of future developments of e-technologies in health care.

- Imagine you are asked to evaluate HealthVillage as a next-generation e-health system. What steps would you take? Create a list of criteria you would use to conduct this evaluation, and discuss what you expect to find.

References

Benmour, E. (1999). Hospital technology speeds information delivery. Business First–Louisville, 15(46), 38.

Burn J., & Caldwell, E. (1990). Management information systems technology. Oxford, England: Alfred Waller, 1990.

Coile, R., & Trusko, B. (1999). Healthcare 2020: The new rules of society. Health Management Technology, 20(8), 44–48.

Deckmyn, D. (1999, August 2). Internet health care to grow. Computerworld, 33(31), 25.

Delevett, P. (1999). Tech Rx. Business Journal Serving San Jose and Silicon Valley, 17(12), 29–31.

Fell, D., & Shepherd, D. (1998). Hospital marketing and the Internet Revisited. Marketing Health Services, 18(4), 44.

Meszaros, L. (1996). Patient confidentiality a big concern with Web access. Physician's Management, 36(7), 15.

Moynihan, J. (1999). New security guidelines will foster EDI use. Healthcare Financial Management, 53(1), 57.

Nugent, D. (1999). Providing solutions for the growing trend toward home healthcare. Health Management Technology, 20(8), 28.

Raghupathi, W., & Tan, J. (2002, December). Strategic IT applications in health care. Communications of the ACM, 45(12), 56–61.

Shaffer, R. A. (1999, September 27). The Internet may finally cure what ails America's health care system. Fortune, 140(6), 274.

Tan, J. (2001). Health management information systems: Methods and practical applications (2nd ed.). Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett.

Tan, J., with Sheps, S. (1998). Health decision support systems. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett.

Weber, D. (1999). Web sites of tomorrow: How the Internet will transform healthcare. Health Forum Journal, 42(3), 40–45.

West, D. (1998). On-line prescriptions have adverse reactions. Pharmaceutical Executive, 18(11), 28.

Wilkins, A. S. (1999). Expanding Internet access for health care consumers. Healthcare Management Review, 24(3), 30–41.

E-Communities Case: Scalability Challenges in Information Management

Harris Wu, Joseph Tan, Weiguo Fan

A dramatic number of e-health communities (or e-communities) have emerged to provide e-health information and allow patients and health care professionals to share their knowledge and experience. In 1998, 60 million adults sought health care information on the Web (Taylor, 1999). A Harris poll in August of 2000 showed that 98 million adults had used the Web to find health information or contribute their experiences (Harris Poll, 2000). E-communities have more benefits than just the ones experienced by patients. Internet technology can facilitate the distribution of important medical information and knowledge to the medical community (Detmer and Shortliffe, 1997). Web-based dissemination of medical evidence has helped evidence-based medicine, a new medical paradigm based on meta-analysis of medical evidence, to replace the traditional authority-based paradigm (Brownson, Baker, Leet, and Gillespie, 2003).

Federal and state agencies, health care organizations, local communities, and individuals have set up thousands of e-communities. Yahoo alone provides forty-three health subcategories linking to 19,000 sites (Rice and Katz, 2001). On-line health communities range from small groups of people who face similar medical problems to large professional and commercial sites that provide many services, including the opportunity to interact with other people.

Recently, there appears to be a tendency toward consolidation of such e-communities (E-Health Initiative, 2004). Smaller organizations have found that they do better by investing in intranet systems and extranet systems rather than content-intensive Web portals because of the expenses to create, monitor and maintain such e-communities which, in turn, requires a critical mass of participation in order to survive for the long run. Many Web communities have failed simply because not enough people participated in them (Preece, 2000). From the larger perspective of the field of e-health, consolidation of e-communities helps avoid duplicate investment in providing general medical information to the public and reduces costs in integrating heterogeneous information systems. Moreover, a large e-community can obtain a critical mass of participants, which produces network benefits and enables tasks such as statistical knowledge mining. Besides cost savings, large-scale e-communities present new opportunities for evidence-based medicine and medical knowledge discovery. Small e-communities will still exist, but most of them will center on specific diseases or specific regions.

Large e-communities such as drkoop.com and WebMD.com have millions of users and documents. In this case, we discuss some scalability challenges and promising directions for information management in large e-communities. We have placed these challenges and directions in three broad categories: information delivery, information organization, and knowledge mining.

Information Delivery

Information overload presents a formidable challenge to e-community users. In a large e-community, the problem usually is not insufficient information; rather, the problem is how to get the specific information needed. Decades of information retrieval research have dealt with information overload and medical information retrieval, yet e-communities present some new unique challenges, including information quality, handicapped information users, and personalized information delivery.

The quality of information is extremely critical in e-communities. Inaccurate information can cost lives. Traditional information retrieval research has focused mainly on two measures: precision rate (the percentage of results that are relevant) and recall rate (the percentage of relevant information that is retrieved). Accuracy and other quality measures have rarely been the focus of any studies.

One idea for addressing the quality of information in a huge repository is collaborative filtering. An e-community contains a huge amount of information, much of which is contributed by individual users; thus, it is impractical to examine each piece of information. Collaborative filtering is a technique that harnesses the power of multitude. Information can be filtered by collaborative efforts of e-community users, through mechanisms such as voting, ratings, and relevance feedback. Users in an e-community, as well as documents, can be evaluated according to the information they contribute. For example, the Hub/Authority approach (Kleinberg, 1998) builds on the premise that “good” people (people who are considered to be an “authority”) should contribute “good” information and identifies high-quality information (linked to source) in a system.