Understanding Global Environments and Cultural Value Systems

The unexamined cultural value system of a society does not serve the means and ends of civilized people.

When you have read this chapter you should be able to:

understand the concepts of a society,

indicate why people behave in different ways,

define culture,

know how knowledge can help us better understand other cultures, and

understand how society at large orients human beings toward continuity in their lives.

The theme of this chapter concentrates on people around the world who have different grouping structures and how these structures have bearing on people’s cultural orientation and behavior. More specifically, in the following pages, key components are defined that make up a community and its cultures, a dozen or more structural design forms of cultural behavior are presented, distinctive cultural components that make a society different from others are identified, and the different effects of cultural orientation on international business are considered.

The Culture and Global Environments

There are holistic perceptions about periodic views on questions such as: What is human? What is life? What is the potential of people’s cultural context? How can a culture enhance or retard people’s social behavior? Contemplating these and other questions has caused many philosophers, artists, scientists, and technologists to revisit these phenomena through different angles.

Through culture, we have learned and practiced how to conquer nature: tame the wilderness, make war on pests and vermin, control land, make dams on the rivers, and finally, battle against the elements where only the fittest survive and where whole species of life-forms that got in our way are exterminated. In most cultures, people are taught to see nature apart from themselves as the enemy to be pushed around in a world composed of separate entities, unrelated to each other, each on its own journey to infinity (Finkel, 1994: 80).

Much that is puzzling in other cultures can be understood only when they are considered evolved as a nation. Technologists, enamored by the persistence of their own gadgetry, reassure us that a better world is within our grasp. The critical-thinking synergy of technological explorers is the result of many generations who have developed their research capabilities to relate their cultural, creative, and artistic expressions in mechanisms of combination of synergistic thoughts and actions. It is true that all people are products of natural law, but they are also creators of their own cultures. Culture is free of, or apart from, natural law only to the extent that human thoughts can be apart from natural laws (Gilford, 1960: 341).

Many unprecedented innovations are taking place in people’s cultures. Innovations do not just happen. Individuals within their lifetime and the boundaries of their cultural orientation and personal curiosity make innovative ideas and methods happen. Cultural innovations are subject to people’s conceptions, perceptions, imaginations, beliefs, wills, goals, and choices. Within the contextual boundaries of people’s awareness and cultural synergy, people have been viewed as innovators of their own cultural times because of their capability to think abstractly and move in practice from the historical trends of technological eras (e.g., from teleolithic, eolithic, paleolithic, and neolithic technologies to electronic robotics and nano technologies). All these achievements have come from pluralistic efforts among multicultural contacts.

All societies have been changed as a result of cultural borrowing from one another. Peter Drucker (1995: 12) suggested that the greatest change in the way cultural business is conducted is the accelerating growth of relationships based not on ownership but partnership. In the five-year period from 1990 to 1995, the number of domestic and international knowledge-based technological alliances has grown by more than 25 percent annually (Bleek and Ernest, 1995: 97).

Cross-cultural understanding through contacts between individuals and groups is as old as recorded history. People in all generations and times have traveled to other lands to trade, teach, learn, settle, exchange ideas, convert, or conquer others. They changed their lifestyles due to economic conditions, technological developments, and sociocultural status. In the prejet age, people were much more centered in their interests and goals. Today, because of scientific advancement and technological breakthroughs in transportation and communication, scholars, explorers, travelers, adventurers, refugees, traders, missionaries, and tourists are exposed to and communicating with other cultures directly through multidimensional informational virtual reality. This is the real face of today’s human civilization.

The Basic Conceptual Model of a Society

People by their very nature are not self-sufficient. They need to cooperate with one another to fulfil their needs. If they are to survive over time, they must develop social relations and maintain social order. Socialization is a continuous process throughout life. Socialization involves the process by which people develop and acquire a set of customs and procedures for making and enforcing decisions, resolving disputes, and regulating the behavior of themselves and others. Every society must maintain pluralistic decisions on the basis of the enormously wide range of behavioral potentiality which could be open to them starting at birth through their biological, cultural, and family influences. These are customary and acceptable according to the standards of, initially, the family and, later, social groups and affiliated organizations (Mussen, 1963: 60–61).

As used in this book, the term society encompasses all tangible and intangible concepts and things related to a lively group of human beings. Society generally means a nation and/or a professional group of people. This concept of society includes people with ideas, beliefs, attitudes, ideologies, expectations, values, perceptions, and material things. These concepts are arranged in scales of values or performance systems. These help individuals and organizations to set and seek common ends. For example, in American society the institution of law clearly reflects and affects major civic values. I have mentioned this here because of the importance of the concept of law to our implementation of the so-called free market. When we begin discussing how different countries approach free markets, an understanding of moral, ethical, and legal behaviors will be crucial.

Society is dynamic because all individuals and organizations are constantly in motion and interacting to make changes. Therefore, the term society from a sociopolitical perspective means, essentially, to conceive when one speaks of a lively dynamic nation and/or civilization. Inherent to this concept are eight fundamental interrelated parts that make up the abstract of a dynamic society. These are (1) people, (2) culture, (3) institutions, (4) material objects, (5) knowledge and technology, (6) religion, (7) intellectual potency, and (8) governments (see Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1. Component Parts of a Dynamic Society

The People

Marger (1985: 16) defines: “Societies comprising numerous racial, religious, and cultural groups can be described simply as multiethnic.” People can be defined as groups who come into contact for a purpose and are dependent on one another to achieve their societal objectives. Human beings who gather for the purpose of satisfying needs are called people. There are two major groups of people in a society: (1) primary groups of people and (2) secondary groups of people. Primary groups of people are composed of family members: nuclear, single parent, extended, mixed, and homogeneous families. Secondary groups of people are societal formal and informal citizens and residents of a nation who congregate and live together with political, cultural, economical, emotional, or similar objectives. Formal citizens or residents of a nation can comprise different groups of people such as task groups, command groups, work groups, professional groups, friendship groups, ethnic groups, and others. Each group of people displays a unique set of cultural subtraits and patterns of expected behavior. People within a culture display a sense of commonality of community among themselves.

The citizens and/or residents of a nation of large groups create a sense of “peoplehood.” This sense of oneness derives from an understanding of a shared ancestry, cultural heritage, and/or a common cause for their unity (Gordon, 1964). Sometimes people live together in a particular area on the basis of their ethnocentric identity, geographical territory, culturally ascribed denomination, or commonality in their religious faith and similarities in their political ideologies.

The Concept of Culture

Historically, people tried to put diverse or disparate concepts and elements together and capitalize on similarities for meeting their societal needs. The objective of such integration is to increase effectiveness by sharing perceptions, insights, aspirations, and knowledge. Thus, human culture is the way of living together, of developing and transmitting values, beliefs, and knowledge, of struggling to manage uncertainties, and of creating an artificial (versus natural) degree of social life precision.

People in a society generally develop cultural values that tell them what is important, how it got that way, and how things should be. Such perceptual concepts form the substance of a culture. More specifically, a culture is the integration of human group ideas, attitudes, customs, and traditions in a unified pluralistic system. In general terms, that unified system of socialization is accepted in a somewhat established standard of perceptual and behavioral modes toward an attempt to meet the people’s needs. Culture copes in overt and covert ways to make group behavior unique by adapting people’s perceptions to their physical and ecological surroundings.

Culture Is Defined

Culture is a means to cope with surrounding uncertainties by providing predictable ways of expressing and affirming pluralistic values, beliefs, and norms of understanding and behaving toward an end. When cultural anthropologists tried to define culture, they included all aspects of human societal life as parts of a culture. Two prominent cultural anthropologists, Kroeber and Kluckhohn (1952: 181), after cataloging more than 160 different definitions of the term culture, offered one of the most comprehensive and generally accepted definitions, which follows:

Culture consists of patterns, explicit and implicit of and behavior acquired and transmitted by symbols, constituting the distinctive achievement of human groups, including their embodiment in artifacts; the essential core of culture consists of traditional (i.e., historically derived and selected) ideas and especially their attached values; culture systems may, on the one hand be considered as products of action, on the other as conditioning elements of future action.

Hofstede (1994: 4) states: “Culture is the collective programming of the mind which distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from those of another.” Culture, therefore, makes people’s lives very smooth and allows them to get on with the necessities of living (Trice and Beyer, 1993). Brown (1976: 15), in his research in defining culture, indicates a culture is:

(1) Something that is shared by all or almost all members of some social groups(s), (2) something that the older members of the group(s) try to pass on to the younger members, and (3) something (as in the case of morals, laws and customs) that shapes behavior, or … structures one’s perception of the world.

Although there is no complete agreement on the underlying theories of cultural definition, cultural anthropologists agree on certain characteristics. Hofstede (1980: 25) defines culture as: “The interactive aggregate of common characteristics that influence a human group’s response to its environment.” Downs (1971: 35) states that: “Culture is a mental map which guides us in our relations to our surroundings and to other people.” And perhaps most succinctly as “the way of life of people” (Hatch, 1985: 178).

Spradley (1979: 5) defines a culture as: “The acquired knowledge that people use to interpret experience and generate social behavior.” Symington (1983: 1) defines culture as: “That complex whole which includes knowledge, beliefs, art, law, morals, customs, and any capabilities and habits acquired by a man (or woman) as a member of society.”

Moran and Harris (1982: 108) define culture as: “The way of living developed and transmitted by a group of human beings, consciously or unconsciously, to subsequent generations. More precisely, ideas, habits, attitudes, customs, and traditions become accepted and somewhat standardized in a particular group as an attempt to meet continuing needs.”

In sum, all scientists capture the essence of what makes a person’s culture similar: it is the general agreement that a culture is collective, dynamic, learned, shared, transgenerated, symbolic, patterned, and adaptive. All attributes will be described briefly here and revisited many times throughout future discussions.

Culture Is Learned

Cultures are not genetic or biological, they are relatively perceived as permanent changes in behavior or potential behavior resulting from understanding and experiencing our life events. During the first half of the twentieth century, psychologists and other social scientists tended to explain people’s behavior in terms of various instincts or genetically based propensities. Today, this instinctive interpretation of human behavior is no longer held (Ferraro, 1994: 19). However, we cannot deny the effects of biological and genetic characteristics on human socialization. For such reasons, most social scientists agree that human beings are social creatures. The most widely studied determinants of human socialization are biological, social, and cultural. Biology influences personality in a number of ways. Our genes help determine many physical characteristics, and these may in turn affect personality. Genetic factors may also directly affect personality, because we inherit some of our emotional and sensational traits from our parents and/or ancestors. It is very difficult to separate “nature” from “nurture”—social and cultural (Van Fleet, 1991: 35). The term “nature” denotes all genetic characteristics that people acquire from their parents and environments through their physical identity (e.g., color, feature, race, and ethnicity). The term “nurture” means all social behavior and psychological characteristics that people learn from their associates and surroundings (values, attitudes, motives, ideologies, ideas, beliefs, and faiths).

Culture is learning to change. People who have been accultured or encultured are changed. Although learning does not necessarily imply a positive or negative change, you may learn, for example, through your cultural orientation to be a “straight-faced liar” or a “pathological liar.” The changes resulting from cultural learning are usually long lasting.

Culture is the essence of reproductive efforts of human intellectuality through learning and experiencing. However, people interact with their surroundings through their learning traits from past generations and communicate with future generations in complex ways. They interact with their social and biological traits. Therefore, cultures should be learned through understanding and experiencing.

Culture Is Pluralistic

Culture manifests pluralistic intellectual and emotional traits reflected on the social mirror of a group of people in a society. Culture is the general identity of individuals’ interactions, interdependence, and interrelatedness of concepts and behaviors in terms of their collective lifestyles. Cultures are both the individual’s depositories and repositories of what a society agrees about their pluralistic lifestyles. A pluralistic culture is one in which many cultural traits and institutions exist through which power is diffused. The invisible dynamic forces manifested on both individuals and groups about how to interact with and counteract constraining forces in their environments is called culture. Steiner and Steiner (1997: 60) identify several features of American culture that contribute to its pluralistic nature:

It is infused with democratic values.

It encompasses a large population spread over a wide geography and engaged in diverse occupations.

The Constitution creates a government that encourages pluralism.

A pluralistic culture functions within a free market society and imposes immediate, concrete, and close boundaries on the discretionary exercise of cultural power.

Culture Is Shared

People in a nation become bonded together by sharing views of their concepts and world events. They socially bond with one another with ethical, moral, and legal commitments. A culture is not a special manner for a single individual; it is a collective identity of a group of people who share similar characteristics. People look to other members of their culture for support and confirmation of their shared meanings and expected actions. They also expect approval and disapproval of their own and others’ behaviors from other people.

People depend on one another for emotional and practical support, which facilitates cultural prosperity and synergy. They share their ideas and values and depend on other members of their culture to help them get through life’s uncertainties and difficulties. Members in one culture build their cohesive ties by sharing information and piling up positive rewards and avoiding pain, which increases their cohesiveness. Terpstra and David (1991: 106) state that: “Coordinated action among humans is possible only when understandings of reality are shared and can be communicated to others.” The cultural management theorist Webber (1969: 10) describes the nature of cultural sharing by making an analogy with the sea: “We are immersed in a sea. It is warm, comfortable, supportive, and protecting. Most of us float below the surface; some bob about, catching glimpses of land from time to time; a few emerge from the water entirely. The sea is our (shared) culture.”

Culture Is Dynamic

Cultures are not static, they are dynamic. Cultures are collective dynamic efforts to cope with change and agents of change. No matter the speed by which cultures change, one fact is evident: no cultures remain completely static year after year. Cultures are evolved and evolving. While cultures create continuity and persistency of values between generations, they are reproductive. Snow (1959) created a stir by asserting that there are two different and sometimes conflicting cultures in human civilization: science and humanities. He cited that the most important revelation is a difference in mode of dynamic thinking. Culture is the artistic production of human beings’ conception. Verbal, logical, and cause-effect thinking first takes place in the culture of the humanities, especially in the works of artists, while a dynamic combination of visual and spatial thinking is a major requirement of technology and most of the sciences. This dynamic mode of thinking offers the answer to the relationship of arts with technology and science, because art, even more than technology or sciences, depends upon spatial thinking. There is a synergistic factor that connects three modes of cultural thinking and places them within what Snow (1959) sought to call a “single culture” or what I call “dynamic and organic cultures.”

Culture Is Adaptive

Each society consists of two interacting systems: a cultural system (which prescribes the structural operational patterns and the way in which people should behave) and the individual’s character (which defines the personality of individuals). Hence, optimal outputs can be obtained when the two systems are joined. Evans-Pritchard (1954: 54) indicates that:

The function of culture as a whole is to unite individual human beings into more or less stable social structure, i.e., stable systems of groups determining and regulating the relation of those individuals to one another, and providing such external adaptation to the physical environment, and such internal adaptation between the component individuals or groups, as to make possible an ordered social life.

Theories of personality are abundant. Evolutionary, dialectical, cyclical, and biological analogies of the birth and death of civilizations are among the sweeping yet often exciting interpretations of changes in human cultures and behavior. Social change is the process of dynamic movement of a social system from one relatively homeostatic structural cultural character balanced toward another. Homeostatic structural character denotes describing a structural organism in physiological equilibrium maintained by coordinated functioning of the brain, heart, nervous system, etc. Shifts in the structure of behavior interaction of individuals are not social changes unless they are sufficiently powerful and prolonged to cause modification in the culture and in the motivations and values of individuals.

Cultural adaptations are not to be confused with social changes of which they are a part. Shifts in individual drives, needs, and tendencies are less likely to be confused with cultural changes than are structural and functional shifts. They are nevertheless part of the total. However, cultural patterns and the adaptive tendencies and motives of individuals to cope with the sociocultural changes in a society are inevitable: Cultural changes lead to individual character changes; individual character changes lead to cultural and social changes; and finally, cultural and social changes lead to structural changes in a society. Then, the total result of all these changes is cultural adaptation to the new changes. This is definitely not to say that an individual citizen’s personality and characteristics are unimportant in cultural change processes. The timing of adaptive change patterns can vary. There is no doubt that after World War II, for example, the Confucian and Shinto value systems combined in Japanese culture to support structural development. Japanese culture emphasized “familial” loyalty, obedience, frugality, and hard work to adapt their traditional rigid culture (as Samurai Culture) into a supportive and assimilative culture of modernization by elite dedicated leaders and their subordinates (Bellah, 1957: 35).

Culture Is Integrative

At one time many American anthropologists, sociologists, and social psychologists believed American culture was a “melting pot.” Harvey and Allard (1995: 3) argued that there is diversity of opinion about this; there are those who argue that the “melting pot” only existed outside the organization gates while inside the white male culture dominated. Still others argue that there never was a melting pot at all. Therstrom (1982: 3) states that: “There never was a melting pot; there is not now a melting pot;… and if there ever was, it would be such a tasteless soup that we would have to go back and start all over.”

American culture is diverse and resembles a “salad bar.” All subcultures maintain their integrity but are in harmony with other subcultures, much like a beautifully colorful plate of food. Petracca and Sorapure (1995: 3) indicate that: “Although we may place ourselves in specific folk or high cultures, subcultures or countercultures, we are aware of, perhaps even immersed in, the broader popular culture simply by virtue of living in society.” Such a connectivity is called multiculturalism.

Ferraro (1994: 34) indicates that: “Cultures should be thought of as integrated wholes—that is, cultures are coherent and not logical systems, the parts of which to a degree are interrelated.” Harvey and Allard (1995: 3) state that: “Culture envelopes us so completely that often we do not realize that there are other ways of dealing with the world, that others may have a different outlook on life, a different logic, a different way of responding to people and situations.”

Culture Is Transgenerational

The historical perspective of cultural heritage indicates that culture is cumulative in its development and is passed down from one generation to the next. Emile Durkheim (1858–1917) often stressed the need for causal analysis in addition to functional analysis, suggesting that culture is rooted in human history. Similar to philosophers August Comte (a positivist) and Herbert Spencer (an empiricist), Durkheim borrowed his methodology to study culture from the natural sciences: distinguishing between causes, functions, and structures. Durkheim (1938) noted the importance of causation, which is a manifestation of ideas from cumulative development of reasons through historical experiences that have been passed down from generation to generation.

Terpstra and David (1991) indicate that the interrelation of cultural symbols and meanings is not mechanical, as in the parts of a machine; it is an interrelation of contrasts that makes a difference to persons in society. The interrelation of symbols and their meanings has consequences: a change in one element will change in relation to other elements. Each society practices its own traditional value system. For example, owning a car in American culture is a symbol of mobility, but in a third-world country, it represents a symbol of wealth and the importance of the social class of a family. Therefore, culture is symbolic, because a citizen of a developed country may not understand the meaning of poverty without understanding the meaning of wealth.

Culture Is Socialization

Social learning is part of an individual’s socialization. Cultural socialization means getting into, breaking in, learning in, settling in, perceiving in, and practicing in a culture—whether the culture is corporate, national, regional, international, and/or global. There are three component parts in socialization: (1) learning, (2) behaving, and (3) evolving.

Learning indicates to a person what principles, facts, philosophies, and techniques have adapted in his or her behavior and how he or she has learned all the customs and traditions in a specific culture.

Behavior involves cognitive and behavioral changes that occur in a learner’s performance, from learned habits and experiences.

Evolving involves the results which occurred in such areas as reduced individual frustration, deficiency, and fatigue in the modes of perceptual and behavioral reductions, in grievances, and in improvement in quality of life.

The Concept of Institutions

All social organizations are institutionalized in terms of written and unwritten rules and regulations to which people in a society must conform to maintain legitimacy in such a society. Institutions are those more or less formalized and acculturalized entities by which society tries to bring order and discipline. They are orderly forms, conditions, procedures, and methods of grouping people and their activities. Societal institutions are systems of command, communication, cooperation, coordination, and control (the five Cs). As Wheelen and Hunger (1986: 294) have indicated, all institutions and/or organizations can be grouped into four basic categories.

Private for profit: These institutions operate their activities on the basis of the market economy for generating their means of survival (profit). Examples of these institutions range from small businesses to major corporations.

Private not for profit: These institutions are created by law and given limited monopolies to provide particular goods and/or services to a population at large or a subgroup (e.g., Department of Defense, courts, and public utilities).

Private nonprofit: These organizations operate through philanthropic, humanitarian, religious, and goodwill contributions. The major sources of these institutions are provided by donations, contributions, endowments, religious levies, and other charitable organizations (e.g., The United Way, churches).

Public agencies: These organizations operate on the basis of constituted laws and authorities to collect taxes and assess penalties while providing public services for all people in a community.

If a society is desiring and willing to be prevailed upon, then institutions can provide people with the basic cultural philosophical knowledge, cultural experiences, and political ideological practices.

The Concept of Material Things

The fourth element in a society encompasses tangible material things, such as stocks of resources, capital, labor, land, minerals, and all manufactured goods and products. These resources help a nation to shape society, and they are partly products of the nation’s institutions, ideas, and beliefs. Economic institutions, together with the quantity of stock of resources, determine in a large part the type and quantity of a nation’s material things. As material things change, the nation’s ideas and beliefs also change. In the manufacturing and service industries, three factors have traditionally been identified as major instruments: (1) Capital, which is subject to interest; (2) Land, which is subject to ownership, rent, and/or lease; and (3) Labor, which is subject to legal, ethical, and moral contractual bindings.

For the past 100 years in industrialized nations, both neoclassical and neo-Marxist political economies have, to a large extent, distanced themselves from classical political economy, which emphasized land, capital, and labor. Instead, they emphasized the two-factor models, which aggregate land with rent and/or lease and capital with interest. The appropriateness of neoclassical labor-capital models in a capitalistic society is denoted in those economies where land, not capital, is dominated by landowners. Such a perception has not changed. Nevertheless, the terms of rent and lease are not explicitly recognized. Recently, attempts have been made to rebuild neoclassical economics to accommodate institutional behavior These initiatives are now reversing to the grassroots systems of special historic rights, but, again, without defining property rights in any way immediately useful to the interests of labor (Smiley, 1995: 290). However, it should be indicated that nowadays, the emergence of technological patents, trademarks, and copyrights have provided skillful and specialized labor privileges for obtaining some bargaining power and advantages from manufacturing and/or service operations.

Some cultures are highly materialistic, some to such an extent that the ruling class views their subordinated classes of people as soulless commodities to be bought and/or sold (e.g., communist countries, slavery, and Islamic theocracy). These cultures are usually regarded as the first formalistic believers that universal principles are necessary to constitute existing things as the presence of matter. Atomists view that all things are made of molecules—basically water. The Greek philosopher Anaximander believed that all things in the universe are formed from an original chaos or gas. Thus, on the basis of such a cultural belief, Anaximander foreshadowed modern nebular theories of the origin of the universe in the nineteenth century (Weber, 1960: 163).

In some cultures, material things are means and ends of the social order and competition. Having access to material things divides people from one another. Instead of all people sharing and living in harmony and peace, possession of material things divides a society into classes of people. The owners of material things are viewed as the means of production on one side and the tenants as workers on the other. For example, in communist and authoritarian countries, societies are divided in two basic classes of people: very rich and powerful and very poor and powerless. The states, laws, courts, police, schools, churches, and media are all controlled either by the political elite ruling class, by plutocrats, or by both. The end result is exploitation of human resources. Exploitation of human resources is the alienation of the lower classes of people to the full benefit of the elite ruling class. In primitive societies, classes of citizens have been categorized only by material ownership, not by intellectuality. The consequential results could be called, in a general term, exploitation and alienation of human resources through wage slavery. Materialistic cultures cannot exist without the exploitation of material things, including people.

The Concept of Knowledge and Technoculture

The fourth element in a society encompasses its scientific, artistic, and technological capabilities. An individual is a highly systemized and integrated creature. For the discovery of their environment, individuals use three tools: sciences, technologies, and arts. They take in data through their biological perceptual senses from surroundings. Then they start processing the data through experimenting and distinctive judging. Finally, they express themselves through intuitive declarations of findings. Thinking is a type of intuitive process that is based not only on individual intelligence, but on rationality as well. Experience refers to the reflective behavioral thinking of habitual order of past actions in practice and conveying these memories to the present. Sensations refer to those processes in which individuals take in information via their senses. In contrast, intuition refers to those final decision-making processes which typically absorb information by means of imagination—by viewing the whole assessment of causes and effects. Individuals are teleological purposeful creatures through their own experimental preferences. Human beings are multidimensional purposive creatures viewed as sophists, scientists, technologists, and artists: (1) A sophist views the whole reasoning of causes and effects of existence. He or she theorizes reasons for continuity of survival and finalized life. (2) A scientist applies his or her intellectual capabilities to generalize scientific theorized problem solving. (3) A technologist conveys scientific pragmatic intuitions into material things and innovates and invents software and hardware. (4) An artist creates sensational and emotional expressions through manifestation of his or her own modes of feelings and desires.

Perhaps the most important cultural implication of technology is the growing social role of knowledge. Societies are learning that people need to attend not only to the importance of science and technology alone, but also to knowledge and the institutions of knowledge in general. Acquisition of knowledge refers to those individuals’ perceptual capabilities that typically take in information via scientific methodology. They are most comfortable when they are containing the details of all possible and feasible situations, and are more quantified, concrete, and understand specified facts. Technology has its own characteristics:

It multiplies material or physical possibilities.

It changes its physical features.

It removes some previous options.

It creates new opportunities.

It diversifies capabilities.

It explores human efforts.

It forms social changes.

It creates new values.

It has powerful means to urge itself into adoption and widespread use of diversified resources and tools.

Throughout history, scientists and technologists have developed new techniques and resources such as machines, computers, and data and information processing systems. All of these resources, such as software and hardware, disseminate information and the results become integral parts of societal cultures. Technological experiments brought significant changes in individuals and societal value systems. One important feature necessary for the success of all industries is ethical and moral intelligence gathering. Shani and Sena (1994: 247) state that:

Previous research has come up with what is called a social ethical subsystem, which considers every organization to be made up of a social subsystem and a technical subsystem to produce something valued by the environmental subsystem.

This takes into account the fact that today’s cultures are becoming more automated in every aspect of discoveries. Moreover, automation and technology have become a target in those societies that are pursuing higher productivity.

The result of the integration of sciences and technologies is very fascinating. It has created a new form of multicultural knowledge. Kodama (1992: 70) states that it will have a great impact within the biological and chemical industries, which will create a fourth generation of material. He claims that: “The fourth generation will allow engineers to custom design new materials by manipulating atoms and electrons.” One product that is being considered as qualifying for this category is carbon fibers, which are being used to make airframes for airplanes; the next in biotechnology is cloning.

Today, the use of videotape, teleconference, and computer media has become a vital part of our multicultures. With these technological facilities, people around the world can communicate with one another in seconds.

In the ever-changing world of technology, cultures now face increased competition. This forces some nations to open their sociopolitical doors and others to react and go with the multicultural flow. Many nations have been able to adapt to this change with flexible automation and many of these sophisticated technologies can help nations tremendously. It can save nations time and money through the use of networks, e-mail, groupware, “chat” systems, videoconferencing, and multimedia. Businesses can also reduce the cost of operations and labor. A groupware information system categorizes integrated knowledge of individuals into departments, departments into divisions, and divisions into the total organizational knowledge. Organizational groupware information systems provide both vertical and horizontal linkages to all positions. Nevertheless, there is an inherent tension between vertical and horizontal groupware information systems. Whereas vertical linkages are designed primarily for commanding and controlling the information flow, horizontal linkages are designed for coordination, cooperation, and collaboration to minimize the tension among organizational groups.

Telecommunication systems in organizations increase profits tremendously. In the education industry, for example, it saves time and effort not only for the student but for professors as well. The use of networks provides that extra edge in obtaining information from the mainframe of resources. In the medical industry, it allows doctors and nurses to look up information about a rare disease or even to see what serious side effects a medication can have on patients. As McAteer (1994: 61) states:

New technologies provide information on demand, build banks of shared knowledge, and enable real-time, structured learning events to transcend boundaries of time and space. The technologies become tools that we use to build our solutions.

Everyday technology is becoming more advanced, giving marketers a helping hand. In the early part of the 1980s, the Corning Glass Corporation, for example, invested heavily in the research of waveguides—glass fibers created to replace traditional phone lines. Such breakthrough technology revolutionized human civilization, specifically the communication industry. It provided telecommunications by light instead of electricity, boosting information capacity hundreds of thousands of times. One hair-thin glass fiber— a waveguide—can carry 6,000 telephone calls—as much as a four-inch-thick bundle of copper wires. This new product carried more capacity in less space (Magaziner and Patinkin, 1990: 266).

The Concept of Religion

The sixth element in society is religion. What is religion? Defining religion is a tool and to some degree it is arbitrary. Religion is an abstract of beliefs. We need not undertake a history or catalog of definitions. A hundred or more can be gathered in the space of a few hours; for our purposes, as Yinger (1970: 4) states: “Three kinds of definitions will suffice. One type expresses valuation; … what religion ‘really’ or ‘basically’ is in terms of what, … (1) It ‘ought’ to be … Other definitions are (2) ‘descriptive’ or (3) ‘substantive.’ They designate certain kinds of beliefs and practices as religion but do not evaluate them… .” For some years, a number of writers have expressed the view that Tylor’s (1924) definition of religion: “belief in Spiritual Beings,” was essentially sound (Goody, 1961: 142–164; Horton, 1960: 201–226). On the other hand, some may prefer to define religion in terms of value or in terms of essence.

Religion should not be viewed as only a cultural fact; it should be viewed also as a manifestation of behavioristic character of an individual and as one aspect of a group of people. Also, religion could be defined as that with which we are concerned ultimately. Bellah (1964: 358) asserts that: “Religion is a set of symbolic forms and acts which relate men to the ultimate condition of his [or her] existence.” Briefly, as Geertz (1966: 4) defines,

A religion is: (1) a system of symbols which acts to (2) establish powerful, pervasive, and long-lasting moods and motivations in men by (3) formulating conception of a general order of existence and (4) clothing these conceptions with such an aura of actuality that (5) the moods and motivations seem uniquely realistic.

Since the above definition is highly abstract, in an adequate view, it would seem, we must recognize that an individual has potentialities both for social life and hostility as well as for the self-centered pursuit of values. How do societies manage to keep the latter at a minimum (or at least aimed in a direction not likely to injure the social order) while strengthening the potentialities for social life? One may assert that those societies that did not learn to do this were simply torn apart and disappeared.

The Concept of Intellectual Potency

The seventh element in a society is intellectual potency. Artificial potency, compared with people’s intellectual potency, however, can be considered a new part of society. The instrument of this new type of potency — mental potency — is the computer. In essence, our resources are controlled by information. This dimension may be the most important part of industrialized society. Although resources have contributed to our welfare, our use of them can bring about constructive social consequences too; but misapplication of technology or information raises serious doubts and inspires fear. Our educational and academic challenge is to harness the power of mental potency to the benefit of the human race—not to the destruction of humanity.

The Concept of Government

The eighth element in society is government. The social system and the laws of public policies governing citizens’ rights and duties are major considerations for the concept of government. There is today no aspect of societal operations that government cannot and will not regulate if the occasion to do sound popular or legislative support exists. There are three major philosophical foundations for the establishment of a government: utilitarian, egalitarian, and universalism.

Government is found in serving:

The greatest good for the greatest number and the greatest misery for the smallest number (utilitarianism)

The greatest good for the smallest advantaged or disadvantaged number, and the greatest misery for the greatest number (egalitarianism)

A balancing of various principles of fairness for all (universalism)

McCollum (1998: A28) states that: “Jeremy Bentham, English philosopher, is often thought as the founder of utilitarianism, the school of philosophy that holds that the purpose of government is to foster the happiness of the individual, and that the greatest happiness of the most people should be the goal of human existence.” This type of philosophy can be found in representative democracy.

Egalitarians base their philosophical views on the position that all human beings are equal in some fundamental respect. Each individual should have an equal access to a society’s resources including products and services. They believe that resources should be allocated in equal portions regardless of people’s individual natural and historical cultural differences. Egalitarianism holds that the maximal role of government is to maintain justice in duty and rights among individuals. Inequality is justified only if its existence causes all individuals (especially the favored advantaged or disadvantaged classes of people) to be treated equally for the benefit of the society. This type of philosophy can be found in authoritarian governments.

The third philosophy is the universalization of the role of the government, which can also be called intuitionism. That role of the government is not to promote happiness for either majority or minority groups of people, but for all. The role of government cannot contradict the happiness of another group of people within a nation. The government’s role is commanded to do what is right for all, not for a part. Intuitionism government is perceived as the accommodation of several multiprinciples of justice, including liberty, property rights, and equal human rights for all. All people are free to choose the kinds of opportunities they want to take, or the kinds of contributions they want to make. They have a universal humanitarian responsibility to own and dispense their properties, including intellectual ones, as they choose. Human beings are considered not as means (majority or minority groups), they are considered themselves as agents to be ends in themselves, free to act according to their humane purposes. This type of philosophy can be found in participatory democracy.

Political considerations define the political ideology and legal parameters in which the social institutions must or may wish to be considered. All nations around the world, in the course of political ideology, have a general theme of political viewpoints or perspectives about themselves, their social lifestyles, and their political environments. These points of views vary in the degree to which they are visionary, conscious, and codified. In this matter, we use the term “formal doctrine” to represent complex combinations of viewpoints that are visionary.

Political ideology or a visionary theorization of other societal order could serve as well, although it tends not to emphasize the conscious and codified aspects. The political doctrine includes an elaborated system of concepts, spelling out the entire structure of political means and ends, without specified institutional arrangements. Sometimes, in analyzing the social reality of a political doctrine, it becomes clearer by stepping back from the concrete images of day-to-day activities and events and analyzing the larger historical context of a political doctrine.

In the conceptualization of a political doctrine in a nation, apart from its substantive content, several cultural dimensions seem significant. They include the degree of formalization, the degree of abstractness, the degree of consistency, and the degree of effectiveness.

The degree of formalization: A formal political doctrine which could be called “a manifest function” contains the sole statement of political goals and objectives for which a nation strives. Also, it contains subgoals to be approached “on the way” toward the more general and ultimate objectives. Similarly, it contains specific means—that is, alternative actions of social structure and procedures—that holds a high probability of attaining the political goals. In effect, it is a comprehensive, integrated, and correlated political plan—a guide for all individual citizens and groups of a nation to enjoy equal protection.

The degree of abstractness: Political doctrines may vary also in the degree to which they are abstract or concrete. As citizens use a doctrinal language system, it is an abstract and provides legitimate rights and duties. The problem is in variability of concrete interpretations. For instance, in the political doctrines of some nations we find “equal opportunity in education.” But in implementation of this phrase we find interpretations and operational practices, which differ from their political doctrines.

The degree of consistency: The degree to which the content of a formal doctrine is consistent or integrated with the national objectives seems another dimension worthy of further cultural understanding. In this analytical domain, we should find out how a doctrine is organized, with what degree of variation it has been formalized — simple as opposed to being complex or complicated—and, related to the complexity, the doctrine’s pervasiveness or the scope—that is, how much of societal life of the individual citizen’s is covered by that political doctrine.

The degree of political effectiveness: A doctrine could be analyzed, irrespective of its content, in terms of the degree to which it does have effectiveness or emotional qualities. In this matter, we should distinguish a difference between the doctrine’s goals and objectives, which necessarily committed the individuals and social organizations, to its implicit value systems. A doctrine in our judgment is ultimately acting a cultural faith in effectively endorsing certain ends in societal life and the degree to which it is phrased on irrelevant or highly tenuous grounds.

In political environmental analysis the existence and exercise of power are other matters which we should carefully review. “Power” is one of those value-laden words about whose definition there is general agreement. Nevertheless, there is a wide disagreement on its meaning in an operational setting. Fundamentally, power is the ability of an individual, group, or organization to influence or determine the behavior, expectations, and actions of other individuals, groups, or organizations to conform to one’s own wishes, or in a political context, to a doctrine’s objectives. Power is always related to authority and influence. Authority may be viewed as the right to exercise power. Coercion can be either a form or a component of power. Dominance or domination is a form of power. Consequently, power is a set of dynamic functional forces used to implement the desirable items of an ideology or a doctrine among people.

Sociopolitical and economic forces are forms or tools of power. Both material gains and prestige are consequential results of political power. In our society, there are some strongly held views about power, strength, right, jurisdiction, control, command, domination, and authority—often interchangeably used words. Without elaborating on their different meanings, they all project physical might, mental ability, or moral efficacy.

The modern concepts of power look more toward the functions performed by a power holder than did earlier concepts. The modern concept of political power is conceived as a force to resolve societal problems (see Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2. Societal Power Envelope

In a pluralistic society there are many semiautonomous and autonomous groups or institutions through which power is diffused. No one group has overwhelming power over all others, and each has direct or indirect impact on all others. The political doctrine and constitution combine a unified set of beliefs that citizens must respect them. This combination sets up social institutions, establishes hierarchies, and allocates societal power. Legitimized power should be implemented in organizations through hierarchical authorities in order to deploy different resources for achieving social goals and objectives.

Finally, bases of power refers to the sources which are available to power holders as they exercise either authority or influence. Several bases of power are available in a society. These depend on the sources and the types of power, such as: coercive, remunerative, normative, traditional, charismatic, and knowledge-based power.

People by their very nature are not self-sufficient. They need to work together to fulfill their needs. Socialization is a continuous process throughout life. It involves the process by which people develop and acquire a set of customs and procedures for making decisions, resolving disputes, and regulating their behavior. The term society encompasses all tangible and intangible concepts and things related to a lively group of human beings. It is a nation and/or a professional group of people. Inherent to this concept, there are eight fundamental interrelated parts that make up the abstract of a dynamic society. These are people, culture, institutions, material things, knowledge and technology, religion, intellectual potency, and governments. All individuals who gather for the purpose of satisfying their needs are called people. Culture is a means to cope with surrounding uncertainties by providing predictable ways of expressing and affirming values, beliefs, norms, and expectations toward an end. It is a collective programming of the minds and behaviors of people to make their societal lives very smooth. Culture needs to be learned, shared, and transferred. Culture is learning, behaving, and evolving. Institutions provide those basic cultural philosophies and political ideologies in which a society desires and is willing to be promoted. Material things such as stocks of resources, capital, labor, land, minerals, and all manufacturing goods and products are viewed as necessities of human life. Religion is an abstract of human beliefs. Religion is believing in spiritual being(s). It valuates what the belief ought to be. Intellectual potency means mental synergy. The government is a social system which regulates citizens’ behavior.

Chapter Questions for Discussion

How do you define the concept of a society?

How do you define people in a society?

How do you perceive the concept of culture?

How do you label a culture?

How do you perceive material cultures?

How do you apply the concept of knowledge and technoculture?

How do you perceive the concept of intellectual potency?

How do you define the concept of government?

How do you understand the concept of religion?

Learning About Yourself Exercise #3

How Do You Understand Your Culture?

Following are fifteen items for rating how important each one is to you on a scale of 0 (I don’t believe) to 100 (I strongly believe). Write the number 0–100 on the line to the left of each item.

How do you perceive the following statements about your national culture?

_____ |

1. |

My national culture is very conservative and I like it. |

_____ |

2. |

My culture is a part of the national political ideology. |

_____ |

3. |

My culture is futuristic and promotes change. |

_____ |

4. |

My culture is rooted from denominated historical cultural groups’ political-religious ideologies. |

_____ |

5. |

My national culture is resistance to change. |

_____ |

6. |

My national culture promotes civic commitments. |

_____ |

7. |

My national political leaders are ethical and moral. |

_____ |

8. |

I trust people. |

_____ |

9. |

My national culture should be universal. |

_____ |

10. |

My government is truly defending our national interest. |

_____ |

11. |

The national judiciary system of my country strives for justice. |

_____ |

12. |

Our religious leaders are very spiritual. |

_____ |

13. |

I trust mass media. |

_____ |

14. |

In my culture, most corporate managers are cheating the government and people. |

_____ |

15. |

Bribery is a popular form for doing business in my country. |

Turn to next page for scoring directions and key.

Scoring Directions and Key for Exercise #3

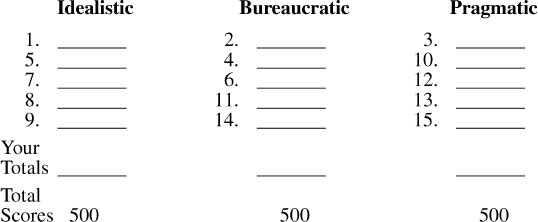

Transfer the numbers for each of the fifteen items to the appropriate column, then add up the five numbers in each column.

The higher the total in any dimension, the higher the importance you place on that set. The closer the numbers in the three dimensions, the more aware you are of your society.

Make up a categorical scale of your findings on the basis of more weight for the values of each category.

For example:

1. 400 Idealistic | |

2. 375 Bureaucratic | |

3. 200 Pragmatic | |

Your Totals |

875 |

Total Scores |

1,500 |

After you have tabulated your scores, compare them with others on your team or in your class. You will find different judgmental patterns among people with diverse scores for the national cultural understanding.

Case Study: The Whistle-Blowers: Smithkline Beecham PLC

Whistle-blowing can be considered a morally, ethically, and legally neutral act by an employee and/or an informant making public some wrongdoings of a firm’s internal operation, practice, or policies that affect the public interest. Bribing government authorities and cheating the public are illegal in the United States and in many other countries. This case is about a “Labscam” investigation conducted by the Department of Justice in a multinational corporation in the United States.

SmithKline Beecham PLC was incorporated on January 24, 1989, under the name Goldslot PLC. On April 11, 1989, SmithKline entered an agreement for the merger of Beecham Group PLC and SmithKline Beckman Corp. excluding Allergan Inc., Beckman Instruments Inc., and their respective subsidiaries. This transaction was implemented on July 26, 1989, through an exchange of securities. In 1992, the company acquired the Corsodyl business from ICI Pharmaceuticals. During 1992, SmithKline Beecham PLC (SKBPLC) disposed of the Manetti Roberts Toiletries business in Italy, and the Personal Care Products business in North America, List Pharmaceuticals in Germany, and the Collistar cosmetics business in Italy. During 1992, SKBPLC also acquired the Clinical Trials Division of Winchester Research Laboratories and many other companies.

SKBPLC continuously produces innovative medicine and consumer health care products. The company specializes in the development and manufacture of pharmaceuticals, vaccines, over-the-counter medicines and consumer health care services. In addition, SKBPLC is better known for its clinical laboratory testing and disease management. Some of the testing services they offer include blood, urine, and tissue testing for use in screening and diagnosis. They also serve as a central laboratory testing location for clinical trials for pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies in Europe and North America. SKBPLC offers emergency twenty-four-hour toxicology tests and substance abuse testing which is certified by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

SmithKline Beecham PLC has its main headquarters in New Horizons Court, Brentford, Middlesex, United Kingdom. This company has several subsidiaries all over the world, some of which are located in France, Germany, Argentina, China, India, Italy, Mexico, Japan, Austria, Panama, and many other countries. This company runs its operation with a total of 52,400 employees. It also has 119,136 stockholders.

Sometime during 1997, through a nationwide “Labscam” investigation done by the Justice Department of the United States with the help of three whistle-blowers (Robert J. Merena, Charles W. Robinson Jr., and Glenn Grossenbacher), SmithKline Beecham Clinical Laboratories Inc., a strategic business unit (SBU) of SmithKline Beecham PLC, was found to be involved in Medicare fraud. The company was accused of paying kickbacks to doctors while billing the U.S. government for laboratory tests not performed, along with other numerous violations. Although the company has denied the allegations, stating that the violations were unintentional as a result of confusion with regulations and guidelines, through a court hearing process, it agreed to pay the U.S. government $325 million in 1997.

Another issue of such a settlement was the problem of payments for the three whistle-blowers. The Justice Department had resisted paying the three men the 15 to 25 percent share of the SKBPLC’s settlement specified for the whistle-blowers by the federal False Claim Act. The Justice Department argued that most of the $325 million settlement had been obtained through its nationwide “Labscam” investigations which had nothing to do with the three men. Nonetheless, U.S. District Court Judge Donald W. VanArtsdalen ruled that the three whistle-blowers made a major contribution to the government’s case and that they helped bring in nearly all the settlement.

In relation to this case, SmithKline Beecham PLC acted unethically, immorally, illegally, and inhumanely toward U.S. society and specifically to elderly American patients. They betrayed the medical profession by paying kickbacks to medical doctors. They misled the government by billing them for Medicare patients’ test fees that were never performed, and provided false laboratory results for elderly patients to be kept in their medical record files.

Finally, Judge VanArtsdalen said the three whistle-blowers accounted for all but about $15 million of that total. The U.S. government agreed to pay the three whistle-blowers a minimum of $9.7 million but only if they dropped claims to a larger portion. However, the Justice Department did not prosecute SKBPLC’s fraud which provided doctors and patients with false laboratory results. The Justice Department ignored its accountability to those patients who were mistreated and suffered from side effects of the consequential results of misdiagnosis and mistreatment by false laboratory results. The government’s concern was only the financial side of the case. The case was closed.

Sources: The Wall Street Journal (1998). “U.S. Judge Says Whistle-Blowers to Get $42.3 Million.” April 10, p. 1; Moody’s International Manual (1998). Zoholi Jr., D. A., Publisher. New York: Moody’s Investors Service, Inc., pp. 10777–10779.