Understanding and Managing Individual Personality

Personality is a completed puzzle picture of an individual behavior

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

realize what the major elements of “self” concept are,

understand personality and individual patterns of behavior,

understand various factors of the biological contribution to personality.

understand sociocultural and ecological contributions to the formation and development of personality,

describe the nature of individual differences in organizations,

describe personality types and traits that affect organizations,

analyze managerial styles on the basis of the sociocultural, psychological, and behavioral characteristics of a manager, and

discuss how managers should cope with individual differences.

Today, organizations are becoming borderless global institutions through the free flow of information. In-person communication is not the only way to associate with others. The association can be through e-image, e-mails, or e-commerce. Accordingly, individuals possess two types of behavior: (1) live and (2) imaginary behaviors.

Organizations can be classified according to two dimensions. First, organizations differ in the extent to which they are domestically oriented and culturally homogeneous. This concept is being used here to refer to the behavioral setting within a company. Theoretically, culturally homogeneous organizations are made up of personalities who are more or less working toward the same organizational identification regardless of each individual’s ethnicity, race, color, religion, and so on. Second, organizations can be classified as to the extent to which they differ in being internationally oriented and multiculturally heterogeneous. These organizations vary according to ecological, sociocultural, psychological, and behavioral value systems. The only dilemma of organizational constituencies is individual character or personality.

Several criteria have been used to compare organizational cultural behaviors. For instance, through an anthropological view, organizational cultures have been classified according to whether they are “simple,” or “complex” (Freeman and Winch, 1957: 461–466); or, through the view of marketing, organizations could be perceived through market size and product positions, global, multinational, bilateral, transnational, and international. Also, the heterogeneous view indicates that organizations can be classified into three categories: “near,” “intermediate,” or “far” from the core culture of the corporate’s headquarter (Furnham and Bochner, 1986: 20). In addition, organizations can be classified through other dimensions such as geographic territory, political ideology, and financial ownership. They can be classified as home/host, domestic/foreign, joint ventures/alliances, and profit-making/ not-for-profit organizations. All these characteristics are related to personal variable characteristics of decision makers and operators. Individuals are a combination of many factors, of which genetic, demographic, psychic, social, cultural, and behavioral dimensions emerge from their personalities. Accordingly, organizational behavior will exhibit different cultural characteristics. People possess a multitude of characteristics which function together to represent personalities. Organizational members do not function independently of their environment or the situation in which they find themselves. Situational factors and physiological characteristics can affect how organizational members respond in a variety of ways.

Today, managers are faced with the synergistic challenge to motivate and lead subordinates to achieve specific objectives. Perhaps we can define personality as the overall synergetic potential of an individual. So the more managers understand individual synergies, the better they can lead subordinates.

In this chapter, the concepts of individual differences, along with personalities, values, skills, beliefs, visions, desires, abilities, and lifestyles of people, are explored. The first section of this chapter defines and clarifies the analytical concept of personality. The next section is devoted to the development of personality along with discussion concerning some well-known theories of individual differences. The third section identifies determinants of individual personality within the framework of familial, sociocultural, and psychoanalytic aspects of ecological, situational, and conditional categories. In the fourth section, personhood will be discussed on the basis of the four major dimensions of personalogy: ideographic/nomothetic, types, and trait theories of personality. The final section of this chapter addresses the relationship between personality and the workplace and cultural political behavior of organizational personalities.

Analytical Views on Personalogy

Personalogy is the study of personality structure, dynamics, and development in the individual (Zimbardo, 1992: 567). It is related to actual and practical biographical and past performance data. Personalogy is an analysis of the real past performance of an individual. It is based upon the data from biographies, case studies, letters, writings, and general behavioral observation. It is related to real characteristics and the end results of an individual’s life events. One of the proponents of this technique is called “personalogy of neurotic managerial behavior.” Finally, personalogy is the study of the type and patterns of behaviors of people.

What is Personality?

Personality is a social manifestation of an individual’s behavioral characteristics in accordance with the integration of intelligence and feelings. It is a holistic behavioral representation of “self-concept.” The self-concept of an individual is similar in some ways to and in other ways different from others. The term personality can be traced to the Latin word persona, which translates as “to speak through.” This Latin term was used to denote the masks worn by actors in ancient Greece and Rome. Common usage of the word emphasizes the role that the person (actor) displays to the public (Luthans, 1985: 97).

Personality represents the total characteristics of an individual. It is a critical component of individual differences. It is defined as the ecological, psychological, sociocultural, and behavioral traits and characteristics that distinguish one individual from another.

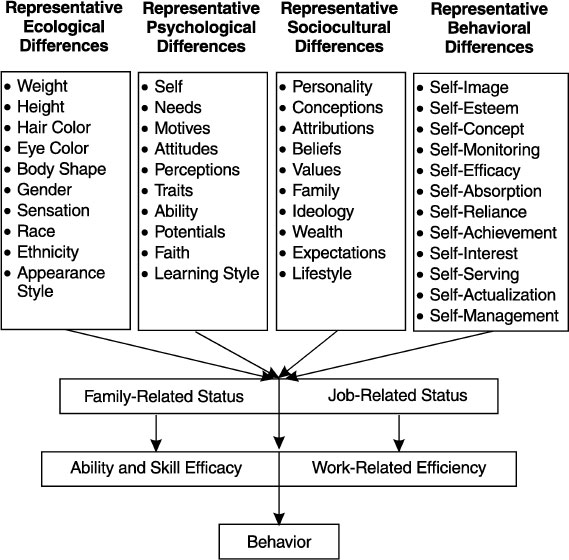

Personality is important to managers because it reflects all the behavioral characteristics of an employee’s work. Numerous observers have pointed out the importance of personality in the probable outcomes of organizational performance. Personal characteristics that most often affect personality fall into four clusters: relevant ecological, psychological, sociocultural, and behavioral characteristics.

As shown in Figure 7.1, the first cluster includes variables for expressing “self.” This cluster includes variables that reflect the heredity and/or genetic identity of an individual. It manifests the physiological heredity characteristics such as weight, height, hair color, eye color, body shape, gender, sensation, race, ethnicity, and appearance style.

Figure 7.1. Variable Influencing an Individual’s Behavior

The second cluster includes psychological variables that reflect past experiences that somehow prepare the individual cognitively and emotionally for perceiving “self.” This cluster concerns psychological factors such as feelings, needs, motives, attitudes, perceptions, traits, ability, potentials, faith, and learning style. Also, this cluster represents feelings of competence, trust, confidence, abilities, and intellectual potential.

The third cluster includes sociocultural variables, which are related to the level of valuable socialization and past dynamic group learning experiences. This cluster demonstrates the type of personality, conceptions, attributions, beliefs, values, family, ideology, wealth, expectations, and lifestyle.

The fourth cluster concerns behavior. This cluster identifies types of behaviors, such as self-image, self-esteem, self-concept, self-monitoring, self-efficacy, self-absorption, self-reliance, self-interest, self-serving, self-actualization, self-achievement, and self-management.

In order to understand personality, we need to analyze two major views: the common or laypeople’s view and the scientific or intellectual view.

Laypeople’s Views on Personality

The laypeople’s or common view tends to relate personality with ecological characteristics and usually perceives it with a single dominant attribution (e.g., polite, rude, strong, weak, shy, persistent). This unique view of personality attributes some general characteristics repeatedly to the behavior of an individual. It represents the total cultural understanding of characteristics of that person. Usually, when laypeople express their opinions about the personalities of others, they perceive a general pattern of behavior across different situations and over time. Then, accordingly, they label the type of an individual’s personality. For example, when a manager in all conditions shows emotion and a passionate exaggeration in praising some special people with the same degree of interest, common people perceive such a manager as having an “emotional and/or warm personality.”

Scientific Views on Personality

The scientific or intellectual view, on the other hand, tends to relate personality to the holistic description of ecological, psychological, sociocultural, and behavioral synergistic factors. Although laypeople emphasize the behavioral role, which an individual displays to the public, scientific people emphasize the individual’s intrinsic and extrinsic traits and conditions. Probably the most viable approach would include all characteristics.

The intellectual view focuses on specific processes that are similar in all people. These processes include neural transmission, conception, perception, conditioning, and attributions. Therefore, the heredity traits, psychological cognitive potentials, sociocultural values, and patterns of behavior are four basic determinants for understanding an individual’s personality. These factors separately and collectively can influence the processes of emotional, sensational, rational, and decisional behavior of an individual.

From another point of view, it is not just that individuals behave and respond differently to the same stimulus in a common condition, there also seems to be inherent aspects that give coherence and order to behaviors. We know this core concept for each of us as our “selves.” For the clarity of this complex issue, it is necessary to study the nature of “personhood.”

Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck (1961: 215) made the best statement about personhood: “To some extent, a person’s personality is like other people’s, like some other people’s, and like no other people’s.” Personality manifests a holistic pattern of an individual’s behavior in consistent ways in a variety of situations.

Personality is defined as the complex set of unique and consistent characteristics that influence an individual’s pattern of behavior across different situations and over time. Personality represents “self” identity in relation to the extrinsic appearance and behavior, intrinsic awareness as a permanent dynamic force, and specific pattern of holistic assessment of “self.” Therefore, personhood is a synergistic organization of selves (e.g., id, ego, and superego) that represents a general combination of sensational, emotional, rational, and intellectual characteristics to be measured and judged by “self” and others (Ruch, 1963:353).

Through a cross-cultural perspective, personality is the self-conceptualization of an individual’s inherent and societal learned identity. This means that individuals represent (positively or negatively) their behavior to others and others collectively understand and judge themselves as well as their societal measurable traits in relations to others.

Determinants of Individual Differences

Ecological, psychological, behavioral, and sociocultural characteristics are the four major determinants of an individual’s identity. Differences among people depend primarily upon four major groups of characteristics:

Ecological and/or physical appearances: facial features, facial gestures, ethnicity, height, weight, size, and other physical aspects

Psychological traits: intellect, extroversion, impulsiveness, flexibility, and so on

Behavioral traits: courteous, vulgar, aggressive, friendly, moral, ethical, and so on

Sociocultural orientations and influences: family-oriented, religion-oriented, educated, wealthy, poor, and so on

In addition, discovering and judging an individual’s personality determinants could be based upon the essence of five different sources of data: (1) self-report judgments, (2) observer-report judgments, (3) incidental behavioral-event report judgments, (4) biographical life-event report judgments, and (5) physiological modes of appearance-report judgments. All these types of judgmental determinants can be interpreted through using two psychocultural approaches: (1) ideographic approach, and (2) nomothetic approach (Zimbardo, 1992).

The Psychocultural Ideographic Approach of Personhood

The psychocultural-ideographic approach is a holistic and synergistic approach. It is a person-centered analysis that focuses on outstanding and unique psychophysiological traits of an individual’s characteristics from an integrated behavioral whole. The primary research methodologies of ideographic approach are the case study and the aggregate case study.

The Cultural Case Study

A cultural case study, used to analyze and judge the type of an individual’s personality, is specifically selected from targeted incidents, manners, and traits of the biographical data of a single individual in a culture. After the careful consideration of the collected data and the discovery of a general pattern of behavior, the judgment about personality will be made. For example, Weiss (1987) discovered in a study on manufacturing, sales, and service employees that the self-esteem of recruits moderated the degree to which successful and competent supervisors served as role models in the recruits’ learning of their organizations’ cultures. Thus, individuals with low selfesteem tend to reduce the efficacy of their organizational goal achievement.

The Cultural Aggregated Case Study

The cultural aggregated case study is a comparison of ideographic information about an individual in different cultures by different observers. After careful consideration of the collected data from different sources, the end result of outcomes of the judgment will be made on the pattern of correlated findings in different cultures by different observers. This is a very complex and challenging method. For example, one study found that Japanese-American managers’ behavior, while working in Japanese-run plants in Fremont, California, had nearly the same behavioral attitudes as Japanese managers in Japan. In addition, most American managers’ attitudes in Japanese plants in Japan resembled the attitudes of American managers in the United States. These results indicate that managerial behavior is a differentiation of cultural value-oriented systems, not subject to drastic change according to new places. It takes generations to adapt behavior to new places. Other evidence indicates that cultural differences persist among immigrants despite acculturation over time to U.S. culture.

The Cultural Nomothetic Approach of Personhood

The cultural nomothetic approach is variable and relatively centered to contingent and situational cultural and behavioral conditions. People and cultures simply differ in the degree to which they inherit, change, and develop their personalities. The cultural nomothetic approach focuses on an individual’s personality within the general contextual traits of a homogeneous encultured population. This approach, in determining the type of personality, is based upon assimilative methods of socialization, correlative methods of ideologies, beliefs, and religious faiths. However, this approach can be more related to the legal pattern of behavioral approach. This type of personality is centered around the civic culture. For example, when multinational managers wish to study how the civic culture of a community can change the direction of the home-host negotiations, they use the cultural nomothetic approach to understand personalities of negotiators.

Five Categories of Personality

Personality is an adaptive stabilized physiological, psychological, behavioral, and sociocultural characteristic that makes an individual unique. Five major scientific categories of personality include the type theories, trait theories, psychodynamic theories, humanistic theories, and the integrative theories.

The Type Theories of Personality

The type theories presume that there are separate, discontinuous categories into which people fit. The criteria that these theories use are physiological appearance and sociocultural and/or psychological characteristics. The first element which represents a person is the physical body—outside and inside. Within the contextual boundary of the type theories of personality, we review twelve types of theories. These theories are: (1) somatotype, (2) type A, (3) type B, (4) type T, (5) extroverted type, (6) introverted type, (7) the Myers-Briggs sixteen types, (8) the five types of Parsons-Shils sociocultural, (9) the four types of Keene’s pair theories, (10) the maturity type, (11) the immaturity type, and (12) the neurotic types of personalities.

The Somatotype Theories of Personality

Early researchers perceived personality to specify a concordance between a simple, highly visible, or easily determined characteristic and some invisible characteristics that can easily determine the type of personality. William Sheldon (1942), a medical doctor, through his research of interrelated physics to temperament, categorized people into three types of personalities based on their somatotype or physical body builds: (1) endomorphic, (2) mesomorphic, and (3) ectomorphic:

Endomorphic personalities represent those types of people who are fat, soft, and round. They are relaxed, fond of eating, and enjoy social interactions. These personalities consume their lives.

Mesomorphic personalities represent those types of people who are muscular, rectangular, and strong. They are filled with energy, courage, and expansive tendencies. These people challenge their lives.

Ectomorphic personalities represent those types of people who are thin, long, and fragile. They are brainy, artistic, and introverted. These people think through their lives.

It should be noted that Sheldon’s views of body-mind personality are intriguing but do not have substantial and reliable research foundation.

Type A and Type B Theories of Personalities

Friedman and Rosenman (1974: 87) did empirical research on the use of personality type labels and their related behavior patterns in order to predict heart attacks. They introduced type A and opposing type B personalities. They defined type A personality as “an action-emotion complex that can be observed in any person who is aggressively involved in a chronic, incessant struggle to achieve more and more in less and less time, and required to do so, against the opposing efforts of other things or other persons.” Type A personalities have an underlying “need for control” and strive to gain control over their environments.

In contrast, the type B personality is not concerned about time and tends to have less need for control, plus does not work as hard to gain control over events. For example, since Christian populations around the world number about 1.5 billion and Moslems number about 1.2 billion out of 6 billion, it is appropriate to compare general religious characteristics of these two faiths concerning the personalities of types A and B. Table 7.1 briefly summarizes the religious cultural value profiles of type A and type B personalities.

Table 7.1. Comparative Type A and Type B Personalities Through Religious Faiths

Christians: Type A |

Moslems: Type B |

|---|---|

They believe in self-efforts; free from pain, from fear, and from desire. |

They believe in destiny; Islam means individuals are submissive to God’s will—Ansha-Allah. |

They work aggressively to achieve individual satisfaction. |

They work patiently to serve God’s satisfaction. |

Work is viewed as a means to transform productivity gains into additional output rather than into additional leisure. |

Work is viewed as a means to comfort and salvation—to serve self and others. They believe that hasty behavior is undesirable, patient behavior is Godly virtue (Koran). |

Talk rapidly and briefly, point by point to get to the objectives. |

Talk descriptively; assess and judge holistically. |

Do many things at once. |

Do things one by one. |

Less emphasis on leisure time. |

More emphasis on relaxation. |

Make deadlines for all activities. |

No deadline for living activities (God’s will). |

They are obsessed with statistical figures. |

They are more tuned with miracles, and God’s will. |

They are pro-legally oriented toward life. |

They are pro-naturally oriented toward life. |

They are always dynamic in their minds. |

They are always praying in their hearts. |

They are very competitive. |

They are very cooperative. |

They reverse their promises on the basis of contingency situations. |

They stay with their promises by all means and ends. |

They play to win. |

They play to have fun. |

They like to work individually and gain personal benefits (capital gain). |

They like to work together and share their bene fits with others (zakat). |

They are more multiculturally oriented. |

They are more co-faith internationally oriented (brotherhood). |

They are more individualistically oriented for achievement (not necessarily for making profit). |

They are more family oriented toward spheres of social orientation for their happiness. |

They are expressive in their feelings. |

They hide and control their feelings. |

First, they fall in love and then marry. |

First, they marry and then fall in love. |

Believe in and practice monogamy. |

Believe in and practice polygamy. |

Believe in having a formal spouse at one time and divorce spouses very rapidly. Men may sometimes have affairs and take mistresses. |

Believe in and practice with one to four formal wives and as many temporary wives for certain period of time. |

Divorced spouses or widowed women marry several times in lifetime. |

Widowed women do not marry again. Widows remain single as a sign of loyalty to their late husbands. |

Source: Adapted in part from Weber, Max (1969). “The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism,” and Kember Fullerton, “Calvinism and Capitalism.” Both in Webber, R. A. (Ed.), Culture and Management. Homewood, IL: Richard D. Irwin, pp. 91–112.

Rosenman and Friedman (1971) concluded in their research that type A people are more prone to the worst outcome concerning stress. Type A people experience heart attacks twice as often as type B personalities. Researchers found four type A personalities: (1) time urgency, (2) competitiveness, (3) polyphasic behavior, and (4) hostility. The four types of A characteristics are a direct result of a need to control self (Sturbe and Werner, 1985; Smith and Rhodewalt (1986).

Type T Theory of Personality

Psychologist Frank Farely (1990: 29), through his research, has defined another type of personality. He identifies a type T personality as one that lives for thrills. The type T personality is also called the hard personality. These people have a drive for life risk-taking, stimulation, and excitement seeking. Farely describes type T personalities as: “You may have not heard of this personality, but I will wager that you know some people who show the pattern of characteristics I have listed… I believe type T is at the basis of both the most positive and constructive forces in our nation (T plus creativity) and the most negative and destructive forces (T minus delinquency, vandalism, crime, drug and alcohol abuse, drinking and driving, etc.).” Most normal people fall between the high-risk, thrill- and stimulation-seeking types and those people who actively avoid any risk or thrill.

Extroverted and Introverted Personalities

Swiss psychologist Carl Jung (1971) focused his research on the assumption that people are fundamentally different, but also fundamentally alike. His classic work, Psychological Type, suggested that the population is made up of two basic types: extroverted and introverted personalities. Extroverted personalities have strong tendencies toward socialization and emphasize perceptual judgments. Introverted personalities have weak tendencies toward socialization and prefer to be quiet. These types of personalities are more tuned to be more imaginative and usually they are listeners.

Jung based his theory on two fundamental types of phenomena: perception (sensing and intuiting) and judgment (thinking and feeling). He greatly expanded the conception of unconsciousness. The unconsciousness concept was the essence of an individual’s unique holistic life experience but was also filled with fundamental psychological truth shared by the whole human race. Jung stated that unconsiousness is responsible for our intuitive understanding of primitive myths, art forms, and symbols and to perceive the universal balancing pattern of existence.

Jung saw the healthy, integrated personality as balancing forces between perception and conception (cognitive judgment). Perception (how we gather information) and conception (how we make decisions) represent the best evidence of our holistic self—personality. For example, Jung assumed that the collective conscious personality of a family is the balance between husband and wife, or the balance between masculine aggressiveness and feminine sensitivity. This view of personality as a constellation of compensating internal forces in dynamic balance is called analytic psychology. Therefore, Jung suggested that human similarities and differences could be understood by combining preferences. It is the matter of choice that we are not exclusively one way or another; rather, we have a preference for extroversion or introversion. Also, he argued that extroverted or introverted personalities are neither different nor better than others. Differences in needs need to be analyzed, celebrated, and appreciated.

Myers-Briggs’ Sixteen Types of Personalities

The Myers-Briggs type theory is based on Carl Jung’s typology of personality. Myers and Briggs became fascinated with individual differences among people and developed the Myers-Briggs type indicators (MBTI) to put Jung’s “type theory” into practical use. They assigned people into one of sixteen categories or types. They used MBTI to find “an orderly reason for personality differences” in the ways people perceive their world and make judgments about it (Myers, 1962, 1976, 1985).

Myers-Briggs type theory of personality assumes that basic differences in perception and cognitive judgment are the result of four fundamental differences in behavior. These four differences include direct sensing (S), unconscious intuition (I), judging by thinking (T), and feeling (F) (see Table 7.2).

Table 7.2. The Type Theory Preferences and Descriptions

Extroversion |

Introversion |

Outgoing |

Quiet |

Interactive |

Concentrating |

Speaks, then thinks |

Thinks, then speaks |

Sensing |

Intuiting |

Practical |

General |

Specific |

Abstract |

Concrete |

Theoretical |

Thinking |

Feeling |

Analytical |

Subjective |

Head |

Heart |

Justice |

Mercy |

Judging |

Perceiving |

Structured |

Flexible |

Decisive |

Exploring |

Organized |

Spontaneous |

Source: Adapted from O. Kroeger and J. Thuesen (1981). Typewatching Training Workshop. Fairfax, VA: Otto Kroeger Association. In Nelson, D. L. and Quick, J. C. (1999). Organizational Behavior: Foundations, Realities, and Challenges. Minneapolis-St. Paul, MN: West Publishing Company, p. 86.

Both perceptions and cognitive judgments are divided into dual ways of perceiving with two possible choices for each. The third factor added to the Myers-Briggs test was a preference for extroversion (E) or introversion (I) which focuses on either the inner or outer worlds. The combination of these preferences makes up an individual’s psychological style of behavior. Sixteen types of personalities have emerged from the combination of these preferences, such as extrovert personalities who demonstrate thinking with intuition or introverts who show sensing with feeling.

The Parsons-Shils Five Sociocultural Pair Types

Talcott Parsons and Edward Shils (1951) have powerfully influenced the efficacy of sociocultural values on shaping personality by describing five different pairs of personalities. These are:

Universalism/Particularism: Am I a universalist or a specialist? Should I deal with others in terms of their particular relationships with me or on the basis of universal criteria of human rights?

Performance/Quality: Is any action to be judged by looking at how it is carried out or by whom it is carried out?

Affective Neutrality/Affective: Am I an affective neutralist or affective? Do I emphasize objectivity or affective involvement in the appropriated attitudes?

Specificity/Diffuseness: Am I a specifist or diffusionist? Are my commitments and obligations specific or are they diffuse?

Self-Orientation/Collective Orientation: Am I an individualist or collectivist? Can I appropriately pursue my own objectives and desires without fear of societal retaliation or should the objectives of the collective be governing in my society?

Fallding (1965) states that these types of sociocultural behaviors are not values in themselves, but refer to the consideration involved in electing values by different types of personalities.

Parsons emphasizes that an individual’s personality possesses multiplicity of sociocultural role definitions and institutional norms. For example, there would be little disagreement in a multinational corporation with the idea that a manager-employee relationship should be universalistic, performance oriented, affective neutral, specific, and self-oriented; whereas their relationships with their children as a father/mother and son/daughter should be particular, quality oriented, infused with affective, diffuse, and collective orientations. However, in defining the type of personality through a professional perspective, some blurring of distinctions can be found not only in behavioral fact, but probably also in the sociocultural values and norms themselves. For example, a physician and/or a professor is supposed to be collectively oriented and effectively neutral but at the same time, some degree of self-orientation is expected and permitted. For a physician, a patient’s bedside, or, for a professor, a student’s mentoring manner that expresses some affect is expected.

Keene’s Four Types of Religious and Neurotic Personalities

James Keene (1967) undertook a complicated task to study the relationships between personality and religion. Although his research’s random sampling was not based on a scientific methodology, Keene was able to match fifty people from five major religions, such as Jewish, Catholic, Protestant, Baha’i, and nonaffiliated groups on the basis of age, sex, education, and socioeconomic status. Keene concluded that observed relationships are due to the religion-personality interaction and not due to uncontrolled variation in other variables. The results are too complex to report in detail. However, the main finding of Keene’s observation is useful in identifying four types of personalities:

Catholics who score low in religious participation (Irrelevant) and in beliefs in the afterlife, the soul, and God (Secular) tend to be at once Neurotic, Self-accommodating, and Ethnocentric. On the other hand, a high rating on the Salient and Spiritual factors predicts Adaptive, Group-accommodating, and Worldminded behavior. (p. 150)

There are significant personality-religion interactions. Group means and variances are significantly different. We know something of Keene’s scores on the four personality factors: (1) neurotic/adaptive, (2) spontaneous/ inhibited, (3) worldminded/ethnocentric, and (4) self-accommodating/group accommodating. More important, various interactions among the dimensions appeared. For example, participation in religion is correlated with worldmindedness in the Baha’i group and with ethnocentrism in the Jewish group (Keene, 1967) (see Table 7.3).

Table 7.3. Keene’s Four Personality Factors

Source: Keene, J. (1967). “Religious Behavior and Neuroticism, Spontaneity, and Worldmindedness.” Sociometry. Vol. 30, p. 147.

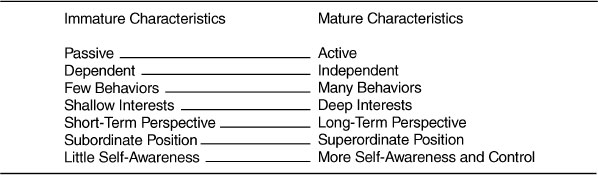

The Maturity and Immaturity Traits

In addition to the above types and theories of personality, there is another approach to identifying personality formation development within an organizational behavior context. Although there are some genetic physiological and psychological blueprints for identifying the type of personality, there are some cultural variations in categorization of personalities. Chris Argyris (1957) has proposed a model of the workplace personality that integrates the stage and trait approaches. His model is summarized in Figure 7.2. This model focuses appropriately on people in organizational structures and settings. Argyris applies the psychological patterns of formation and traits of personality according to the inner promotion and refinement of an individual’s characteristics through experience. He believes that people at any age can have their degree of development plotted according to the seven dimensions. According to him, managers and employees develop their personalities from immaturity to maturity along seven basic dimensions. Argyris suggests that maturation refers to the process of growth in all usual organizational traits.

Figure 7.2. Then Immaturity and Maturity Model

Source: Adapted from Argyris (1957), Personality and Organization: The Conflict Between the System and the Individual. New York: Harper-Collins, p. 50.

In order to obtain full expression of employees’ personalities, the formal organization should allow for activity rather than passivity, independence, rather than dependence, long-term rather than short-term perspectives, occupation of a position higher than that of peers, and expression of deep, important abilities (Argyris, 1957: 51–53).

Argyris suggests that employees gain knowledge, experience, and self-confidence in their jobs. They try to move from the immature end to the mature end of each dimension.

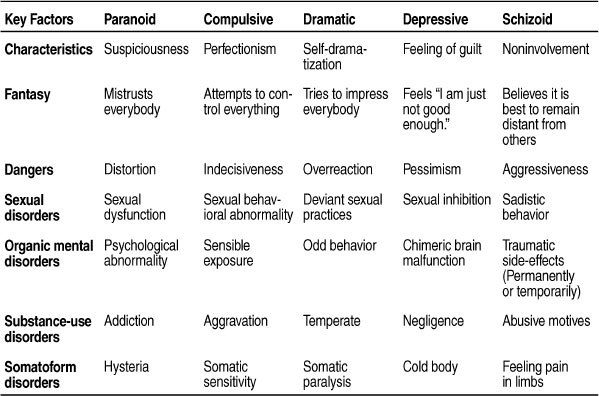

The Neurotic Managerial Styles of Personality

Not much has been known about neurotic behavioral patterns of managers, dysfunctional organizational climates, disturbing peer interrelations, and rigidity in managerial defense mechanisms. Yet we virtually never notice these issues in modern organizational behavior textbooks. The only news we hear concerns managerial neurotic styles in the time of grievance and/or in litigations.

There are always a number of ways of conceptualizing, categorizing, and analyzing managerial neurotic behavior. Kets de Vries and Miller (1984) applied psychometric, psychodynamic, and psychoanalytic tools to study the style, the type, and the pattern of managerial neurotic behaviors. These researchers, through their findings, identified five neurotic styles that relate to the five most common types of top managers. They called these personality styles paranoid, compulsive, dramatic, depressive, and schizoid. Researchers applied seven dimensions for their deliberation. These dimensions are: (1) neurotic personality types, (2) dysfunctional group processes, (3) transferential pattern of subordinates or superiors, (4) improper modes by binding, abandoning, and proxies, (5) life-cycle-related crises during a manager’s career, (6) psychodynamic defense mechanisms and resistance, and (7) disappointment and resistance caused by loss of status, security, or power (see Table 7.4).

Table 7.4. Summary of the Five Neurotic Behavioral Styles

Source: Adapted partially from Kets de Vries, M. F. R. and Miller, D. (1984). The Neurotic Organization, San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 24–25.

In this chapter, we have dealt with personality types and traits. Attention has been paid to individual behavior in an organization. Furthermore, there is little attempt to explain the top managerial personalities. In this section, we are studying the type of managerial personality through psychoanalytic literature. They are used to understand, predict, and classify common managerial personalities.

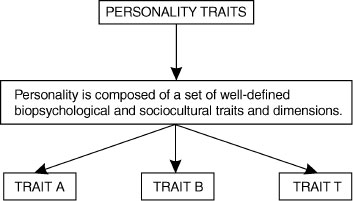

Trait Theories of Personalities

Trait theories of personality try to identify a holistic configuration of positive and negative characteristics of people.

An individual possesses instinct, sensation, emotion, imagination, intellect, genetics characteristics, information, knowledge, and problem-solving abilities. Therefore, we easily gain the impression that individuals are so complex in their own structure and activity that they cannot analyze as just one sort of being, distinctive and different from other living beings. Therefore, an individual is a whole and unified entity who has an extraordinary variety of behavior.

The type theories of personality presume that there are separate, discontinuous categories into which people fit. By contrast, the trait theories propose hypothetical continuous dimensions of an individual’s mind-body relations. Thousands of traits have been identified over the years. Traits are generalized by the coherent relations between body-mind tendencies that people possess in various degrees. Accordingly, they combine these traits into several group forms in which an individual’s personality can be recognized. Traits lend coherence to an individual’s behavior in different situations and over time. For example, you may demonstrate honesty one day by a moral obligation to tell the truth to your manager while you are judging your peers, and on another day by not covering up deficiencies of peers who are your friends (see Figure 7.3).

Figure 7.3. imensions of the Personality Traits

Allport’s Three Traits Theories

Allport (1937, 1961, and 1966) was one of the most influential personality trait theorists. He viewed traits as the building blocks of personality and the main source of individuality. He saw traits as broad, general guides that lend consistency to behavior. According to his views, traits produce coherence in behavior because they are enduring attributes and are general in scope. Allport identifies three kinds of traits: (1) cardinal traits, which organize an individual’s life; (2) central traits, which represent major characteristics of an individual, such as honesty; and (3) secondary traits, which specify personal features that help us predict the individual’s behavior, such as food, grooming, and dress preferences.

Cattell’s Sixteen Bipolar Traits Theories

Cattell (1963 and 1973), another prominent trait theorist, took a different approach from that of Allport. Cattell has identified sixteen bipolar adjective combinations of traits and sources of traits. First, he determined thirty-five bipolar surface traits and then he narrowed them down into sixteen bipolar adjective combinations such as affectothymia (good-natured and trustfulness) versus sizothymia (critical and suspicious attitudes), ego strength (maturity and realism) versus emotionality and neuroticism (immaturity and evasiveness), dominance versus desurgency (depressed and subdued feelings). He finally found clusters of traits that correlated, such as affectionate-cold, socia- ble-seclusive, honest-dishonest, and wise-foolish. He described source traits in bipolar adjective combinations such as self-assured-apprehensive, re-served-outgoing, and submissive-dominant.

The Big Five Personality Trait

More recently, psychologists and human resource management researchers have condensed all traits into a list of five major personality traits, known as the “Big Five” (Norman, 1963; Digman, 1990; Costa and McCrae, 1985). The five traits include extroversion/introversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and openness to experience. Description of the “Big Five” are shown in the Table 7.5. These traits are very general and broad. They need to be tested scientifically in all cultures in order to validate this theory.

Table 7.5. The “Big Five” Personality Traits

Sources: Adapted from P. T. Costa and R. R. McCrae (1985). The NEO Personality Inventory Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; J. F. Salgado (1997). “The Five Factor Model of Personality and Job Performance in the European Community.” Journal of Applied Psychology. Vol. 82, pp. 30–43; M. R. Barrick and M. K. Mount (1991). The Five Big Personality Dimensions and Job Performance: A Meta-Analysis.” Personnel Psychology, 44(1), Spring, pp. 1–76; J. A. Digman (1990). “Personality Structure: Emergence of the Five-Factor Model.” Annual Review of Psychology. Vol. 41, pp. 417–440; W. T. Norman (1963). “Toward an Adequate Taxonomy of Personality Attributes: Replicated Factor Structure in Peer Nomination Personality Ratings.” Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. Vol. 66, pp. 547–583.

Psychodynamics Theory of Personality

Discussion on psychoanalytic theory of personality is traced back to the views of Sigmund Freud (1856–1939). His ideas concerning psychodynamic theory of personality involve unconscious motivation and the development and structure of personality. Freud’s treatment technique is called psychoanalysis. He emphasized the unconscious determinants of behavior. Freud viewed personality as the interactional processes among three elements of personality: the id, ego, and superego. He conceived the id as the primitive and unconscious part of personality (the unleashed, raw, institutional drive struggling for gratification and pleasure)—the storehouse of personality. The ego represents reality; it rationally attempts to keep the impulsive id and the conscious of the superego in check, and represents an individual’s personal view of physical and social reality (the conscious, logical portion that associates with reality). The superego is the storehouse of values, including moral attitudes learned from society (the conscience that provides the norms that enable the ego to determine what is right and what is wrong). There is an ongoing conflict between the id and superego. The ego serves as a compromiser creating a balance between the id and the superego. However, when id and superego pressures intensify, it becomes more difficult for the ego to work out optimal compromises.

Humanistic Theory of Personality

Humanistic or self theory of personality contends that the self-concept is the most important part of an individual’s personality. Carl Rogers (1959) believed that the central motivational force in an individual is the innate need to grow and actualize one’s highest potentials. The “I” is the personal self, the self that one believes oneself to be and strives to be. The “me “ represents the social self. The “me” is the way a person appears to the self and the way the person thinks he or she appears to others.

This theory focuses on morality, ethics, ritual religious faith, and other distinguished traits such as philosophy, aesthetics, creativity, and innovativeness. These traits appear gradually and continually in human personality through transitory and recurrent configurations in physical objectivity and events, and in overt behavior and covert experiences. It is the natural flow of appropriate experiencing through application of self-motivated power (Parhizgar, 1995). Therefore, the humanistic theory of trait personality focuses on continuity of an individual’s sociopsychological growth and improvement.

Integrative Theory of Personality

Recently, some researchers have found a correlation between personality and cultural characteristics of individuals. This view has given a broader impact to formation, growth, and development of personality. Brislin (1981) conducted intensive research among different cultures in order to discover whether a behavior found in one culture also occurs in other cultures. He applied the cross-cultural method to compare diverse sexual patterns and perceptual differences in reactions to illusions. Triandis (1990) conducted research among 100 cross-cultural studies concerning basic distinctive traits throughout the world. He addressed two basic personal characteristics: individualistic and collectivistic. He found that individualistic societies stress the individual as the most important unit; they value competition, individual achievement, and personal fulfillment. In contrast, collectivist societies place the greatest value on social group, family, community, or tribe. In general, all of the cultural characteristics influence in growth and development of peoples’ personalities in all cultures. In addition, Hofstede (1980b) used the cross-cultural method to compare diverse sexual patterns and cultural factors that influence productivity. This theory has found a correlation among personality dispositions, which includes emotions, cognizance, attitudes, expectancies, and fantasies (Buda and Elsayed-Elkhouly, 1998).

The psychosociological types, traits, and models of personality just discussed in this chapter are crucial factors in the field of multicultural management. They highlight the complexities of employee-employer relations as well as understanding individual behavioral differences. There are two dimensional views of the effects of personality in the workplace: (1) individual characteristics and (2) group cultural-political characteristics.

Individual Characteristics

If we consider humans as living beings, we would say their general characteristic functions are growth, metabolism, and reproduction. Also, if we consider that human beings are living beings, they possess specific features of individual characteristics such as intelligence. Intelligence makes an individual rational. To live well as a human being is to live a life of reason and the good use of reason. However, individuals possess other learned or cultural characteristics that change their behavior to other characteristics such as emotional and sensational behaviors.

The most possible direct application of the individual characteristics identifies an individual’s beliefs in terms of self-behaviorism. Six of these characteristics are egocentrism, authoritarianism, Machiavellianism, racism, bureaucratism, and nepotism and favoritism.

Egocentrism is the extent to which a person believes only in themselves. The employee and/or employer can imagine a world from only one perspective—the egocentric point of view. This egocentric view is evident during the individual’s conversations and concessions with others. Egocentrism refers to an individual’s inability to take the perspective of other persons’ rights and privileges into his or her judgmental perception. Egocentric employees and/or employers always try by all means and ends to get all credits and privileges for themselves.

Authoritarian Behavior

Authoritarianism is the extent to which a manager believes that power is the only tool to be used to manage other people. The question why prejudice exerts a strong influence over certain individuals but plays a relatively minor role for others is addressed by the theory of the authoritarian personality. The major factor in such a behavior is that a personality type exists that is prone to prejudicial thought. Adorno and his associates (1950) found evidence to support the notion of prejudice and extremist thoughts and behaviors in authoritarian managers. Such authoritarian managers are conformist, disciplinarian, cynical, intolerant, and preoccupied with power. The stronger the belief in power, the more prejudiced behavior the manager is said to exhibit.

Researchers found that highly authoritarian people are more likely to obey orders from someone with authority without raising any serious objections, even if they recognize potential dangers and pitfalls (Psychology Today, 1989: 66–70).

Machiavellian Behavior

Some managers believe that “the ends justify the means.” This type of behavioral philosophy is rooted in a historical ideology by Niccolo Machiavelli, who was a sixteenth-century Italian statesman. He wrote The Prince, a guide for acquiring and exercising power (Bull, 1961). Machiavelli asserted how the nobility could more easily gain and use power to manipulate people. A Machiavellian personality, then, is one willing to do whatever it takes to achieve one’s own objective. Researchers assert that Machiavellianism is a type of behavior that varies from person to person, time to time, and place to place. Individuals who are high on Machiavellianism personality believe and act by the notion that “it is better to be feared than loved.” High Machiavellian personalities put little weight on loyalty and friendship and enjoy succeeding in their objectives by all means and ends. Low Machiavellian personalities, in contrast, value loyalty and relationship, with emphasis on self-achievement. The best expression for Machiavellian behavior is “to change the position in accordance with the wind direction to safeguard personal interests by all means and ends.”

Racist Behavior

Racism is a sociocultural belief and behavior or political ideological agenda that is structured around four basic ideas (Marger, 1985):

People should be classified by their physical appearances.

Physical appearances represent intrinsic characteristics.

Physical characteristics such as gender, race, ethnicity, and color make some groups superior to others regardless of individual inherent characteristics.

The failures of a group at the bottom of the social hierarchy are assumed to be a natural outcome of genetic inheritance, rather than social disadvantage.

One of the byproducts of racism is the narcissistic personality. It is the development of a grandiose sense of self-importance, preoccupation with fantasies of success or power, and a need for constant attention or admiration. Narcissistic personalities often respond inappropriately to criticism or minor defeat, either by displaying an apparent indifference to criticism or by markedly overreacting (Zimbardo, 1992: 629).

Racist behavior in some societies is used as an important determinant for practicing societal privileges. In these cultures, the elite political groups classify people into majority and minority on the basis of ethnicity, race, color, and origin of birth. Ethnic groups are identified by race, gender, colors, and ethnicity to be rewarded. For example, in Kuwait, there are two groups of people: (1) Kuwaitians, whose race is traced to a tribe that practiced inbreeding, and (2) those people who are known as working-class people, whose origin of birth is not Kuwaitian, even though those people were born in Kuwait.

In contrast, in multicultural societies, there is no consideration of ethnic, racial, color, and gender classification. Accordingly, people are classified by their efforts. In multicultural organizations, recruitment, promotion, transfer, and separation will not be based upon racial appearances but by the merit system.

Bureaucratic Behavior

Organizations produce very formatted structures through continuous trial-and-error processes. Clearly, organizational structure, processes, and policies are critical determinants of the overall success of an institution. The pervasiveness of bureaucratic structure and behavioral expectations of an organization and the resiliency of Max Weber’s ideal bureaucracy clearly suggest that they contain powerful effects on managers’ behavior. Unfortunately, many weaknesses of bureaucratic organizations display managerial misbehavior.

Many bureaucratic managers become too rigid and inflexible, and they are not able to respond positively to the progressive trends of the changing environment. In a highly bureaucratic system, managers become obsessive about implementing rules and regulations without paying attention to the organizational causes. The end result of such an organizational philosophy is creating “impersonal behavior among organizational members.” This type of behavior results in “self-alienation” and destroys cooperation between superiors and subordinates. The bureaucratic personality becomes more concerned about enforcing rules than about actually achieving intended results (Schoderbek, Cosier, and Aplin, 1991).

McFarland (1991) indicates that the spread of bureaucratic behavior in management is usually said to be part of government development—providing experience, norms, and capabilities for state structures. However, bureaucratization of people is an obstacle to democratization. Since bureaucratized managerial systems are not highly productive, innovation cannot be manifested by centralized decision-making processes. Consequently, managers trap themselves with their own rules.

Nepotism and Favoritism

Nepotism managerial behavior is a kind of family and/or friendly “patronage,” which shows sympathy to relatives and friends at the time of managerial decision-making processes. Sometimes such a behavior is based upon “kickback” responses to the previous favors by patrons and alliances. This type of managerial behavior is financially oriented. A patronage system supports its patrons through controlling appointments to the public service or other political favors. When a patron receives a favor from supporters, in a traditional cultural value system, he or she should be loyal to the supporters’ will and serve them by all means and ends. In addition, a patron who receives income from supporters needs to respond to the favor of those who have made his or her income possible. There are three types of people who are involved in a patronage system: (1) masters who have financial and/or sociopolitical power, (2) brokers who play the role of mediators and receive a financial and/or sociocultural percentage of favors, and (3) patrons who receive direct favors. Patrons who receive favors will be obligated and should be obedient to the will of their masters.

The practice of nepotism and favoritism depends on the cultural value system in a nation. For example, in most Arab countries and in some Hispanic communities nepotism and patronage behavior is prevalent and morally accepted; in some other cultures, such as Germany and Japan, nepotism and favoritism behavior is considered improper and illegal.

Managerial nepotism and favoritism behavior is based either upon the homogeneity group’s expectations and/or “giving and receiving” deals— “tit for tat.” This type of managerial behavior forces organizations to be unproductive. However, nepotism or any form of favoritism in a corporate culture that does not seem to reward via merit will negatively affect employee morale and performance. Multinational corporations whose leaders are basically tuned with productivity and innovation avoid nepotism and favoritism. They need to act on the basis of meritocracy not bureaucracy. As communities become more industrialized, the tendency toward meritocracy becomes more prevalent. In contrast, as a community or a corporation becomes more conservatively oriented with the inbreeding patronage personalities, nepotism and favoritism are more popular.

Cultural-Political Characteristics

A concept closely related to personality is politics, or political personalogy. Political behavior is the generalized objective-orientation by which people attempt to obtain and use power. A political figure is one who is more concerned with winning favor or retaining power than maintaining principles. There are two types of general skills in political cultures: (1) political skills and (2) statesman’s skills. Both types of people differ particularly in their connotations. A politician’s behavior is more often “derogatory.” He or she suggests the schemes and devices of one who engages in politics for the benefit of the party’s objectives and/or own personal advantages. A statesman’s behavior is more often “eminent.” He or she seeks conspicuous and noteworthy suggestions along with unselfish devotion to the interests of his or her country.

Since the primary concern of this discussion is organizational behavior, we will focus on different types of beliefs and ideologies across organizational political cultures. Nevertheless, we can note a few ideas about differences and similarities in organizational politics at the general corporate levels. Political cultures vary across organizations. Employees in companies based in the United States, Germany, India, and Egypt are likely to have different attitudes and behavioral patterns in politics. General political thinking and behavior is likely to be widespread and pervasive within a cultural cluster. However, some managers behave differently in different cultural environments.

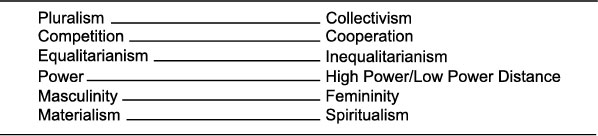

In all organizations, there are several types of perceptual cultural-political behaviors. Figure 7.4 highlights some of the important dimensions along with organizational political behaviors, which vary. These dimensions are pluralism/collectivism, competition/cooperation, equalitarinism/inequalitarinism, high power distance/low power distance, materialism/spiritualism, and masculinity/femininity.

Figure 7.4. Cultural-Political Personalogy Dimensions

Source: Adapted from Argyris (1957), Personality and Organization: The Conflict Between the System and the Individual. New York: Harper-Collins, p. 50.

Pluralistic/Collectivistic Behavior

A pluralistic organization is one that has many autonomous groups through which power is diffused. No one group has power over others, and each may have direct or indirect impact over others. For example, colleges, universities, and teaching hospitals are among these types of organizations. In short, behavioral relationships in these institutions are the result of a professional code of ethical conduct, moral characteristics, and conditions that encourage faculty members, student body, administrative authorities, and the community at large to maintain the boundaries of their groups independently while they are working together.

Pluralistic behavior is a type of professional value system in which individuals behave freely and autonomously within the boundaries of their own legitimate power. For example, it has been observed that Hawaii is an example of a successfully integrated multiracial society (Daws, 1968). Various ethnic groups maintain their distinct identities and cultures. Yet within a general framework of culture, U.S. civic culture binds them together. Within this cultural cluster, in principle, Hawaii maintains equal opportunities and mutual tolerance for all citizens. While each culture, with its own sphere of influence, functions in that society differently, they are sharing similarities in their civic culture.

Organizational pluralism is never an absolute separation of groups. It is an interconnectivity which binds the groups together. The role of a manager in these types of organizations is perceived to be the problem solver. For example, in societies which are characterized by corporate pluralism, ethnic groups are mainly heterogeneous, territorially concentrated, and have long historic roots in their native area (Marger, 1985: p. 81).

In contrast, collectivistic behavior emphasizes group similarities, harmony, and coalition. Collectivistic thinking and behavior is tightly integrated in social patterns with group decisions and actions (family, tribe, or community). Triandis (1990) believes that the lower economic productivity of organizational collective cultures is offset by evidence of healthier quality of life. Collectivistic behavior puts a high value on self-discipline, accepting one’s employment in life, honoring organizational authorities, preserving one’s image, and working toward long-term objectives that benefit the organization as whole. Unions are examples of groups in which members’ unity and loyalty are paramount.

Competitive/Cooperative Behavior

A competitive organizational value system is one in which its sole objective is either rewarding efficiency and effectiveness or punishing inefficient and ineffective constituencies. Competitive cultural value systems create the free market economy. In addition, competitive strategies by business organizations make capitalistic ideology work. Competition in a free market economy causes resources to be controlled and allocated with consideration of:

what and how much should be produced in order to respond to the market demand

how it should be produced with what cost-benefit analysis

for whom it should be produced to be consumed

with what price commodities should it be sold to maintain the corporation’s stability, survival, and profitability

Competitive experiences can provide appropriate opportunities to assess a corporation’s product marketability through trial and error. Also, successful business operational experiences maintain and stabilize the corporation’s market size and product positions (see Figure 7.5).

Figure 7.5. Competition versus Cooperation

A cooperative organizational value system is a joint intentional and behavioral combination of people for purposes of successful production toward joint benefits. Cooperative organizational behavior is a joint conscious and consensus effort of employer-employee togetherness to produce a result that has a survival value for all parties. Cooperative behavior is based on trust and reliance on one another to succeed in mutual goals. It facilitates achievements in a coordinative dynamic operation to reach proper harmonious outcomes of production (see Figure 7.5).

Equalitarian/Inequalitarian Behavior

Equality is the idea that all people should have “an equal place at the starting point of their life.” Equality, traditionally, meant the elimination of inequalities among organizational members with respect to opportunities for social, political, and economic access. Managers provide equal employment opportunities on the basis of ability and character of employees. Some organizations provide equal opportunities at the beginning and gradually diminish it through prejudice. In such a situation, the manager behaves at the starting line with equal opportunity processes, and further down the road it ends up with some political interests with unequal results.

Technically, in multicultural organizations, if equality exists, then there will be no dominant-minority relations among organizational members in nature. Equalitarian behavior promotes balance and cooperation among different employees within the framework of the largest set of agreed-upon principles. However, in such organizations, the competitive differences will not be diminished. This type of managerial behavior promotes a reasonable platform for higher productivity within the consensual rules of the organizational members.

In contrast, inequilitarian managerial behavior recognizes processes and outcomes of an organization on the basis of the severity of job scarcity, the employee’s acute employment needs, and the political ideology of the group interest. The end result of such a managerial system is promotion of the ideological majority culture of the interest group and exploitation of minority groups. Coercive behavior, threats, and intimidation of minority employees by managers can cause high turnover and absenteeism.

High Power Distance/Low Power Distance Behavior

Cultural heterogeneity has been viewed as a power index in nations. Hofstede’s (1980a) power distance index represents seven beliefs (wealth, economic growth, geographic latitude, population size, population growth, population density, and Hermes: (Greek god of commerce) in an organizational innovativeness.

Due to organizational political differences, researcher Hofstede has focused his attention to respond to this question: “Do cultures translate into differences in work-related attitudes?” He and his colleagues surveyed 160,000 managers and employees of IBM who were represented in sixty countries (Hofstede, 1980b). He used the result of his research to develop five cultural dimensions described and defined in Table 7.6. Hofstede’s research is very important because it shows that national culture explains more differences in workplace attitudes than do gender, age, profession, and or positions in organizations.

Table 7.6. Hofstede’s Five Cultural Dimensions

Power Distance |

The extent to which people accept unequal distribution of power. In high power distance cultures, there is a wider gap between the powerful and the powerless. |

Uncertainty Avoidance |

The extent to which the culture tolerates ambiguity and uncertainty. High uncertainty avoidance leads to low tolerance for uncertainty and to a search for absolute truths. |

Individualism |

The extent to which individuals or closely knit social structures such as the extended family (collectivism) are the basis for social systems. Individualism leads to reliance on self and focus on individual achievement. |

Masculinity |

The extent to which assertiveness and independence from others is valued. High masculinity leads to high sex-role differentiation, focus on independence, ambition, and material goods. |

Long-Term Orientation |

The extent to which people focus on past, present, or future. Present orientation leads to a focus on short-term performance. |

Sources: Hofstede, Geert (1980a). Cultures’ Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Hofstede, Geert (1993). “Cultural Constraints in Management Theories.” Academy of Management Executive, 7(1), pp. 81–94.

Power distance refers to members of a group or culture who maintain the special group’s interest among one another (Parhizgar, 1984: 110). Power distance is a tool to be used in different organizations in order to manage inequality among employees. Power distance functions in a multitude of dimensions: high, moderate, and low. Rigby (1985) indicates that power distance has been viewed in different ways: directive, paternal, and autocratic. In democratized power distance (DPD) societies, such as the United States, citizens accept the directive power distance. It is a principle that power functions in multitudinous institutional and organizational orientation to the societal power equalization (decentralization). In DPD organizations, power has been distributed unequally to maintain checks and balances. Managers and employees see one another as similar. The power distance is the result of legitimate authority and expertise.

In contrast, in autocratic countries the power distance scores are high, such as Iran, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, Russia, and others. The elite groups tend to exercise power authoritatively and/or patemalistically (centralized power). In organizations with high power distance, managers are afforded excessive power simply because they are managers. Managers are protected and entitled to their privileges, and employees are considered to have very low or no power. Naturally, the distribution of political power and wealth in all of these countries depends upon the political ideological infrastructure of the cultural power distance. In the low distance power organizations, elite ruling people and experts frequently bypass the managerial hierarchical power to get work done. Denmark and Austria are among countries with a low power distance (Hofstede, 1980a).

Materialistic/Spiritualistic Behavior

Some cultural patterns of beliefs strongly value the principle of survival of the fittest at work in political and economic development. People in these cultures are striving to increase their possessions and use of material goods and services for making their financial position very strong. This “social Darwinism” value system has been a prime influence in the modern organizational cultures for productivity, efficiency, the spirit of competition, innovation, and growth. There are many countries and organizations specifically in the industrialized world that believe in pleasure. These cultures perceive that the essence of life is pleasure. Pleasure comes from the power of material wealth. These cultures believe that materialism perfects an individual’s life. Materialism facilitates goodness when it leads at once to present pleasure and to remote pleasure. Therefore, according to the political belief of materialism, motivation to acquire more material goods and services is good, as it facilitates the desire for leisure, or for a satisfying job even though it may pay a lot more with a stressful performance and for adventures that yield a more comfortable economic life.

In materialistic cultures, the desire for pleasure is closely associated with material wealth and political power. Within the materialistic culture, there are always tendencies toward depravation, dependency, cruelty, and exploitation. For example, Japanese culture has been viewed as a materialistic culture. In October 1999, members of the Diet, the Japanese parliament, called for regulating inhumane demands by debt collection methods of the banking and loan industry. The loan default rate in Japan is extremely low. Nichiei, a Japanese consumer finance company, allegedly asked a loan guarantor to raise money by selling body parts to pay back the loan for Y5.7m. Japanese, culturally, are ashamed to admit bankruptcy. Eisuke Arai, a 25-year-old collection officer of Nichiei Company’s, offered a 62-year-old debtor Y3m ($29,000) for his kidney and Y1m for his eye to help him to finance a loan he had guaranteed to a now-bankrupt company. Arai reportedly said to the debtor: “You have two, don’t you? Many of our borrowers have only one kidney…. I want you to sell your heart as well, but if you do that you’ll die. So I’ll bear with you if you sell everything up to that.” Traditional Japanese banks are shrinking their loan portfolios and leaving many individuals and small businesses with nowhere else to turn. Japanese consumer finance companies enjoy huge margins, benefiting from a cost of funding of about 2.3 percent and an ability to charge interest rates of up to 40 percent for loans without collateral (Abrahams, 1999: 1).

In contrast, spirituality depends upon a deep sense of the cultural value and worth for human freedom and independence. Spiritualism views the good life is to be “happy and live happily.” In these cultures, there is no literal individual satisfaction. These cultures believe that the happiness of individuals and the greatest happiness for all people should be the essence of the existence. Within spiritual cultures altruism must come before egotism. However, it should be noted that egotism and altruism are complementary in modern life. This means, for example, that in order to appreciate the desire to possess property, one must appreciate the property rights of others. In such a culture, individuals will wish to control their pleasure in order to provide happiness for all. For example, in Togoland, West Africa, on the Gulf of Guinea, people do not believe in physical collateral because they believe that the spirit of the borrower is present in the repossessed physical collateral properties and could come and haunt the new owner at any time. Therefore, in Togoland, bankers and lenders do not accept any physical entities such as a house or other properties as collateral for a loan because people strongly believe in spiritual power. Instead, they require that debtors have guarantors. Guarantors are people who vouch that the borrower will pay back the loan. Bankers and lenders require borrowers to provide them with legitimate guarantors to ensure that the borrower will pay them back.

Masculine/Feminine Behavior

Gender identity and role are characterized not only by different physical characteristics, but also they often are identified by cultural patterns of expected behavior in societies. Although the differences between males and females are linked to biology, many are the result of cultural socialization. Cross-gender behavioral patterns vary from culture to culture. Cross-gender behavior is linked to daily activities and the amount of tolerance by the opposite gender. There are two different sociocultural patterns of behavior: masculinity and femininity. Much of what we consider masculine or feminine is formed by our cultural perceptions.

The masculine/feminine dimensions measure the value that a culture bestows on qualities for each gender. By nature, women are communicative, intuitive, nurturing, sensitive, supportive, and pervasive (Schwartz, 1989). Researchers found that most women place a higher sense of importance on long-term relationships (Covey, 1993). Traditionally, when European and/or American women considered an advancement in their careers, they would elevate personal career over family concerns; such a trend is not acceptable in the most Asian and Middle Eastern cultures (Coser, 1975).

In contrast, men are aggressive, very competitive, risk-takers, self-reliant, and their behaviors are predictable by women (Parhizgar, 1994). Men tend to have a management mind-set, are objective oriented, and focus primarily on control and efficiency. Men exert rational power to turn people into work, while women exert their social power to respond to the needs of all organizational constituencies.

Historically, most organizations have been managed by men. In Johnson’s (1976) gender congruency theory of power, he views that the gender-role stereotype influences perception of power within an organization. Masculine societies define male-female roles more rigidly than do feminine societies. Cultures that are characterized by femininity emphasize relationships with others for more socialization. For example, the Scandinavian countries, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Finland, are considered strongly feminine, while Japan, Austria, Saudi Arabia, and most Latin American countries are considered masculine (Hofstede, 1993).

Coping with Individual Differences

As it was mentioned earlier in this chapter, there is general consensus that individual differences affect organizational behavior and vice versa, organizational behavior can affect an individual’s lifestyle. It is important for a manager to manage subordinates first by recognizing that they are different and accordingly to act to motivate them differently too. In sum, managers should make a few assumptions about the types, traits, and characteristics of subordinates’ personalities and understand them as the individuals they are.

While multicultural organizations can draw many implications from the research and theories on personality, especially important messages emerge.

An expatriate manager whose mission is to travel abroad and contact members of other cultures is facing multiple ranges of micro and macro behavioral problems. Cross-cultural relations can begin to be tackled only when a manager explicitly acknowledges that individuals and groups differ in their ecological, psychological, sociocultural, and behavioral orientations. When culturally disparate groups of employees-employers come into contact with each other, they first need to recognize that such differences exist and then act accordingly. This means that they will have an impact on one another’s behavior. In general, expatriate managers, migrant workers, and both home and host authorities should simplify their relations as much as possible.

Managers should never underestimate the differences among subordinates. They should constantly analyze, monitor, and understand their behaviors and revise their assumptions, judgments, perceptions, and attributions about their associates and try to treat each individual as a unique person in a unique place and time.

Although our starting point in this chapter was about the effect of personality on organizational behavior, our ultimate aim was to review different scientific theories and approaches to develop a general understanding about the nature of people. Individual differences make people unique. We are all alike in some ways, and we are different in other ways. Managers need to apply scientific tools and techniques to draw some conclusions that will apply to all organizational constituencies. However, they always need to keep in mind that individual differences and unique characteristics make managers’ ability to understand people important.

One important difference among organizational members is personality. Personality is defined as the complex set of unique consistent characteristics that influences an individual’s pattern of behavior across different situations and over time. Personality structure and behavioral mechanisms can be viewed from the standpoint of determinants, types, stages, traits, and analysis approaches. Finally, management means to analyze, understand, and turn organizational members into workers.

Chapter Questions for Discussion

Define personality in your own words.

Comparatively analyze differences among personality types, traits, and approaches.

How does political ideology influence personality?

How does religion influence the formation of an individual’s personality?

What is the scientific definition of personality?

Give brief examples of each of the major elements of personality.

What are the various factors in the ecological, sociocultural, and behavioral contributions to personality?

How do psychoanalytic theories differ from trait theories?

What are the major Freudian concepts of the “self?”

Why is personality important in organizational behavior?

Why are personality types so relevant to managerial styles?

Learning About Yourself Exercise #7

How Do You Judge Your Own Personality?