ELEVEN

Evaluating and Selecting Ideas

The generation of ideas is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition of innovation. Creativity involves more than producing ideas for resolving a challenge. The ideas somehow must be reduced in number, assessed, and further narrowed down so that one or more potential solutions can be implemented. This applies to individuals as well as to groups and organizations. When innovation challenges are involved, there typically is a group of judges (for competitive idea campaigns) or at least a group of stakeholder decision makers. Therefore, this discussion will assume that at least one group will be involved in evaluating and selecting ideas.

In this chapter, a conceptual distinction will be made between the processes of evaluation and selection. Then some basic guidelines will be presented for managing these processes. Finally, several evaluation and selection techniques will be described and discussed briefly.

EVALUATION VS. SELECTION

The process of idea evaluation precedes that of idea selection. Before you can make a choice, you first must develop some basis for the choice. Then, once you have applied this basis, the selection process will fall into place, with very little difficulty involved in how final choices are made—at least, this is what should happen.

What often happens is that ideas are selected with little consideration given to the basis for the choice. People often select ideas without any conscious awareness of what criteria they used to guide their selections. Although such intuitive decision making can work out quite well for many types of challenges, it can be a severe liability when high-quality solutions are sought—that is, solutions with the greatest probability of resolving a problem. To increase the odds of choosing high-quality solutions, everyone involved in the decision-making process should be aware of the specific criteria being used.

In most group decision situations (as well as in individual situations), criteria used to guide idea selection will be implicit, explicit, or some combination of the two. The use of implicit criteria occurs when ideas are assessed for their potential to resolve a challenge without formally acknowledging the specific criteria used to assess each idea. In groups, this means each member individually applies his or her own criteria without sharing criteria with other members. Frequently, this lack of sharing occurs when members have not agreed on a need to share criteria or when individual members are not aware of the criteria they are using. When explicit criteria are used, the group members must formally acknowledge and agree on the standards they will use to evaluate each idea. It also is possible that criteria may be both implicit and explicit. For example, a group may agree to use certain criteria, but individual members may consciously or unconsciously apply their own criteria in conjunction with the agreed-upon criteria.

Because creative approaches typically are used when unique, high-quality solutions are desired, the use of explicit criteria is an absolute necessity. However, there will be instances in which criteria cannot be fully explored and developed. For example, if time is a critical factor, voting procedures—which use no formal, explicit criteria—may be required. This consideration and others will be discussed further in the next two sections. Nevertheless, explicit criteria should be used whenever possible.

BASIC GUIDELINES

As with most of the other problem-solving modules, idea evaluation selection proceeds more smoothly when basic guidelines are available to help structure the processes involved. These guidelines are especially important when high-quality solutions are needed. If careful attention is not given to idea evaluation and selection, the odds are diminished for transforming any ideas into workable problem solutions. The best ideas in the world will be of little value if they are not first screened and evaluated, so that the cream of the crop can be selected for possible implementation.

The use of guidelines also involves another advantage. By helping structure a process that often involves little structure, guidelines increase greatly the group members’ commitment to the ideas. Even though formal techniques may be used, the outcome is more likely to result in high member satisfaction with the process when a systematic process is followed.

Although not chiseled in stone, the guidelines that follow should help groups approach the evaluation and selection process with more confidence and enthusiasm. Many people view idea generation as the most interesting and stimulating aspect of the creative problem-solving process. And it may be that it is; however, idea evaluation and selection can at least be interesting if a group approaches its task in an orderly fashion, such as using the steps that follow.

1. Assess Participation Needs

There will be times when it may be better to evaluate and select ideas alone instead of involving others; in some situations, it may be better for one or more groups to participate; and in other situations, both individual and group decision making may be better. In order of importance, the major variables that need to be assessed when making such decisions are:

a.Amount of time available

b.Importance of selecting a high-quality solution

c.Need for group members to accept the solution selected

d.Need for group members to experience the evaluation and selection process for their own personal and professional development

You should select ideas alone when there is little time available because the importance of selecting a high-quality solution is relatively low, and a group does not need to accept the solution or experience the process. Conversely, a group should participate when time is available, a high-quality solution is important, successful implementation of a solution depends on group member acceptance of the solution, and group members would benefit from experiencing the process.

However, many participation decisions cannot be made in an either/or manner. In some situations, it may be necessary for you to make some selection decisions alone and allow team members to make the remaining decisions. For example, if time is in relatively short supply, but not enough to justify excluding a group, you might select a final pool of ideas, turn these ideas over to the group, and have the group develop a final solution. Such a procedure would be especially useful when it is important for the members to accept a solution.

2. Agree on a Procedure to Use

As long as others are involved, you need to agree on a procedure for evaluation and selection. You might decide to follow the guidelines presented here, use some other procedure, or go directly to the evaluation and selection techniques. If you are working with others and they decide to ignore the guidelines described here, you still should stress the need to develop explicit evaluation criteria. You also need to decide how to narrow down the pool of generated ideas to a more manageable number. The important concern when others are involved is to agree on some procedure and avoid the temptation to proceed haphazardly.

3. Preselect Ideas

If you have a fairly large number of ideas to evaluate—for example, fifty or more—you need to reduce them to a more workable number. Some of the techniques described in the next section can be used for this purpose, or other methods may be available to you.

Whatever method is used, two major variables to consider are the amount of time available and the importance of the problem. If there is plenty of time and the problem is important—that is, the consequences will be serious if not resolved—you should devote considerable effort to this activity, assuming you are motivated to do so. If there is little time, the problem is not very important, and motivation is low, some shortcuts are needed.

An initial step you can take to narrow down an idea is to examine all the ideas with the goal of developing combinations, which are commonly referred to as affinity groups. When similar ideas are joined together, the overall number is reduced. You also might consider combining dissimilar ideas. Such combinations can often lead to higher-quality solutions than can be obtained from implementing two individual ideas separately.

If a group has developed all possible combinations, you should check for understanding on the part of all members. Decide whether all group members understand the logic, meaning, and purpose of the ideas. Then poll the group members to see whether they are comfortable with the list of ideas. (Examination of an idea pool will often stimulate new ideas that might be added to the list or combined with others. If this occurs, add the new ideas to the pool.)

After you select a final list, you need to decide how to reduce the number of ideas further. If time is inadequate for a thorough evaluation of each idea, two actions can be taken, either alone or in sequence. The group can organize all the ideas into logical categories according to some criterion such as problem type or potential effect. Then it can eliminate those categories of ideas that appear to have the potential as high-quality solutions. A second action is to give group members a certain number of votes. For example, if there are one hundred ideas, members could be given ten votes (10 percent of the idea pool). This is especially useful in brainstorming retreats where ideas need to be narrowed down rather quickly. An even better procedure might be to use idea categories and votes together. This can be done by voting on categories or by voting on ideas within categories. Of course, if you are using idea management software, voting procedures are likely to be built in.

These procedures can also be used if time is not a major concern. However, if the problem is very important, the group can use a slightly different method of reducing the ideas, either by itself or in combination with categories and voting. This procedure involves establishing a minimally acceptable criterion and then eliminating every idea that fails to satisfy this criterion. For example, the group might decide to eliminate every idea that would cost more than a certain sum of money to implement. (If time permits, more than one criterion could be used.)

A decision to use this approach, however, must be made with some caution. If an inappropriate or relatively trivial criterion is selected, many potentially valuable ideas could be eliminated prematurely. Moreover, what appears to be an obstacle to implementing an idea often can be overcome with a little additional problem solving. For instance, it may appear that an idea will cost too much to implement, but minor modifications may make it more workable.

Regardless of which approach a group uses to narrow down the number of ideas, it must come up with a final list of ideas that are ready for evaluation and selection. The group can consider this list tentative, depending on the particular technique or techniques used for final selection. It may be, for example, that the group finds itself with too many ideas to screen, even after preselecting ideas from the initial pool. Or, the amount of available time may decrease suddenly—a frequent occurrence in most organizations. In such cases, the group could recycle the list of ideas through the preselection phase and produce a shorter list.

Share with the group the final list to be used for final evaluation and selection. Ask group members to provide feedback concerning clarity and understanding of the meaning and logic underlying all the ideas. When a group understands and accepts the list, it can start the next step in the process.

4. Develop and Select Evaluation Criteria

Although many of the evaluation and selection methods described in this chapter use explicit evaluation criteria, there are some that do not. As discussed earlier, the quality of ideas selected without explicit criteria may be lower than that of those selected with such criteria. As a result, a group should attempt to make explicit all the criteria it will be using, whether or not a technique requires such explicitness. For example, a voting procedure relying on implicit criteria can be used to greater advantage if the group takes some time to discuss and agree on criteria that might be used to assign votes.

In developing criteria, a group should try to generate as many criteria as possible. As with idea generation, quantity is likely to result in quality. The more criteria a group thinks of, the greater will be the odds that the group will select a high-quality solution. And just as it is important to defer judgment when generating ideas, it is important to defer judgment when generating criteria. Encourage group members to stretch their minds and think of as many criteria as possible without regard to their initial value or relevance.

After a group has generated a list of criteria, it must select the criteria to use for evaluating and selecting ideas. The actual number of criteria selected will depend on the same variables used in preselecting ideas: available time and importance of the problem. When time is available and the problem is important, the group should select as many criteria as possible to use in evaluating ideas. When little time is available and the problem is not perceived as being important, the group can select a minimal number of criteria. However, if only a few criteria are used, it is imperative that the group choose relevant, important criteria that will be most likely to yield a high-quality solution.

5. Choose Techniques

The choice of evaluation and selection techniques can be as easy or as difficult and complex as you want. As with choosing idea generation techniques, many variables can be considered when choosing evaluation and selection techniques. However, in this instance, the choice really narrows down to one among voting procedures, evaluation procedures, and some combination of each. Beyond these considerations, the only other real issue is the amount of time available. Voting obviously will consume less time than group evaluation, even if the group agrees on voting criteria prior to actual voting.

The techniques in this chapter use “pure” voting methods, a criteria-based evaluation procedure that results in the selection of an idea without the need for voting, or “pure” evaluation procedures with no built-in voting mechanism or explicit criteria. There are four major criteria that can be used when selecting from among these techniques:

1.Ability of a technique to screen a large number of ideas

2.Provision for use of explicit evaluation criteria

3.Use of weightings for each of these criteria

4.Relative time requirements for using each technique

6. Evaluate and Select Ideas

At this point in the process, a group should apply one or more techniques to help it evaluate and select the ideas. It should select one or more ideas for possible implementation based on the number of ideas being evaluated, the amount of time available, and the perceived importance of the problem.

If a group selects more than one idea, it should examine possible ways to combine the ideas to produce a higher-quality solution. If the ideas cannot be combined easily (or logically) and the ideas are judged to be equal in quality, the group should consider implementing all the ideas, either in sequence or all at the same time. If the group decides there are too many ideas to implement, it can assign implementation priorities to the ideas and implement as many as possible in the time available. Or, it can screen the ideas again by using an evaluation and selection technique, but with more stringent criteria this time, in order to reduce the idea total. Regardless of what procedure the group chooses for dealing with the remaining ideas, it should constantly be aware of its ultimate objective of selecting a high-quality solution.

The group will, of course, determine the quality of the ideas before it selects any ideas for implementation. In judging idea quality, note that rating of the ideas, as used in many of the selection techniques, will result in a quality evaluation for each idea. Thus, quality will already have been considered at this point in the process. The group will need to evaluate again any ideas that survive these ratings, however, to ensure that it has selected the idea with the greatest probability of resolving the challenge. The group may have overlooked important criteria, or new information may have become available that could affect the previously determined quality ratings of the ideas.

Thus, the last step in the evaluation and selection process is to conduct a final check on ideas that survived the screening process. To do this, each group member could rate each idea (on a 7-point scale) with respect to its likelihood of resolving the problem. The group then could average the ratings or discuss them, with the purpose of achieving consensus. If the group judges none of these ideas to be of high quality, it could re-review ideas that initially failed to survive the screening process but were rated high, and evaluate them with respect to their quality.

TECHNIQUE DESCRIPTIONS

Each technique description in this section includes a step-by-step procedure for using the technique as well as any relevant information about a technique’s strengths and weaknesses. As with all such techniques, modifications should be made to suit a group’s particular preferences or needs.

Advantage-Disadvantage

There are several variations of the advantage-disadvantage technique, but only two will be described here. The first variation relies on implicit criteria and uses a listing of each idea’s advantages and disadvantages. The second variation uses explicit, unweighted criteria that serve as direct measures of advantages and disadvantages.

Follow these steps to implement the first variation:

1.For each idea, develop separate lists of its advantages and disadvantages.

2.Select the ideas that have the most advantages and the fewest disadvantages.

The second variation uses these steps:

1.Develop a list of criteria to use in evaluating the ideas.

2.Write the criteria across the top of a sheet of paper.

3.To the left of the criteria, list the ideas in a single column down the side of the paper.

4.For each idea, make a check beside each criterion that is an advantage.

5.Add up the number of check marks for each idea and select the ideas with the most check marks.

These two variations can be illustrated using a problem on how to improve communications between two departments in an organization. For this problem, suppose that a few of the ideas generated are to do the following:

•Install instant messaging (IM) application on the computers in each department.

•Hold weekly meetings to discuss job-related problems.

•Assign one person the role of interdepartmental project coordinator.

•Have members of both departments attend a workshop on improving communication skills.

•Have both departments meet to identify specific communication problems and to generate possible solutions.

For the first variation of the advantage-disadvantage technique, you can evaluate these ideas using the format that follows. For purposes of illustration, only two ideas will be used. This example is shown in Figure 11-1.

On the basis of the advantages and disadvantages, the idea of using weekly meetings to discuss job-related problems might be selected because it has four advantages and three disadvantages. The first idea, using regular IM, might not be selected because although it has four advantages it also has six disadvantages. This could be due to bias on the part of the rater or knowledge of the options or the ability to think of them. Note, however, that had all the ideas been considered together, it is possible that several of the ideas would have been selected.

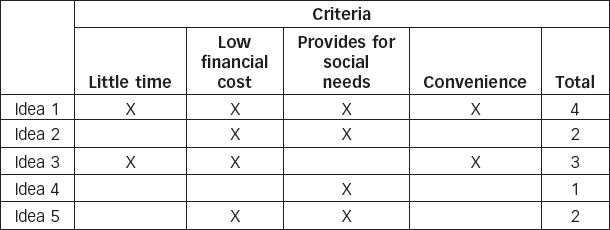

Using the same problem, but with all the ideas listed previously, the second variation could be set up using criteria to rate the five ideas. This analysis is shown in Figure 11-2. On the basis of the results of this analysis, IM would be selected because this idea has the most advantages.

FIGURE 11-1. Comparison of two ideas using the advantage-disadvantage technique.

Idea 1: Install IM application on the computers in each department.

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

• Provides rapid communication. |

• Some people prefer face-to-face communication. |

• Easy to store and retrieve conversations. |

• Might reduce productivity. |

• Convenient. |

• Could be used to avoid confronting other people regarding important issues. |

• Fun for people who like using computers. |

• Miscommunications might occur. |

|

• Could be used to look as if someone is working when he or she may be surfing the Web for personal reasons. |

|

• The network connection might malfunction. |

Idea 2: Hold weekly meetings to discuss job-related problems.

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

• Provides for social interaction needs. |

• Time-consuming. |

• Allows people to better understand the motives of others. |

• Conflict may arise and make some people uncomfortable. |

• Problems can be dealt with by everyone involved. |

• Some individuals may dominate the discussions. |

• Other people’s ideas can be built on to improve solution quality. |

|

Both of these variations have their own advantages and disadvantages. The first variation considers advantages and disadvantages that may be unique to each idea. However, it is relatively time-consuming to use, makes comparisons difficult due to the lack of standard criteria, does not use weighted criteria, and is subject to manipulation by its users. That is, it would be quite easy to adjust the outcomes so that one idea would be a clear winner over another. The second variation has strengths in its ability to screen a larger number of ideas in less time than the first variation, in its use of standardized criteria, and in the fact that its outcomes are less subject to manipulation when compared with the first variation. However, the second variation has disadvantages as well because it requires that an either/or decision be made in evaluating each idea and, like the first variation, it lacks a provision for weighted criteria.

FIGURE 11-2. Example of the second variation of the advantage-disadvantage technique.

In choosing between these two variations, you may want to use the first one when you are concerned primarily with conducting a thorough evaluation of each idea and you have the time to do so. The second variation would be more suitable when you have relatively little time and/or you wish to narrow down a large number of ideas for preselection purposes. It would be appropriate for making final selections, but it is limited by the lack of rating range and especially by considering all criteria as equal in importance. Using both variations would be another alternative to consider, which would be acceptable as long as the weaknesses of each are taken into account.

Battelle Method

Developed at the Battelle Institute in Columbus, Ohio, for screening business development opportunities, the Battelle method uses three levels of screens to evaluate ideas. Each level uses criteria that are progressively higher in cost. In the Battelle method, cost refers to the resource investments required to obtain information needed to evaluate an idea. Thus, ideas are evaluated first using information that is relatively easy to obtain, then using information that is more difficult to obtain, and finally information that is the most difficult to obtain. The funnel effect produced by using such screens makes it possible to reduce a moderate amount of ideas to only a few. The major steps for using the Battelle method are the following:

1.Develop lost-cost screens (or culling criteria) phrased in questions that can be answered with a yes or a no.

2.Establish a minimally acceptable passing score.

3.Develop medium-cost screens (rating criteria) phrased as questions that can be answered with a yes or a no.

4.Establish a minimally acceptable passing score.

5.Develop high-cost screens (scoring criteria) presented in the form of different value ranges—for example, poor, fair, or good.

6.Assign a weight to each criterion.

7.Establish a minimally acceptable passing score.

8.Compare each idea with each of the culling criteria questions.

9.Eliminate any idea that receives a no response.

10.Using the remaining ideas, compare each one with each of the rating criteria questions.

11.Eliminate any idea that falls below the minimally acceptable passing score for the rating criteria.

12.Using the ideas that survive, numerically rate each one against each scoring criterion and multiply that rating by the weight established for the criterion.

13.Add up the products obtained in step 12, and compare each one with the minimally acceptable passing score for the scoring criteria.

14.Eliminate the ideas that fall below the minimally acceptable passing score.

15.If more than one idea remains, attempt to combine some of the ideas or subject them to more intensive analysis.

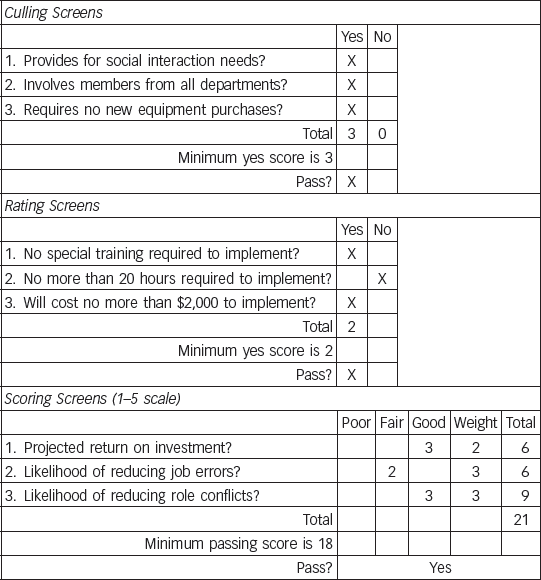

This procedure can be understood better by looking at the challenge of improving interdepartmental communications. Using the idea of holding weekly meetings to discuss job-related problems, the Battelle method can be set up as shown in Figure 11-3. (This example uses a 3-point weighting scale, although a greater range of weights would also have been appropriate.)

According to the outcome illustrated, this idea survives all the screens and could be selected for implementation, combined with other surviving ideas, or retained for additional analysis. Note that the idea of using IM also would have been accepted by the culling screens. One positive feature of this approach, however, occurs when an idea is rejected by the culling screens. Early rejection in this manner can be a strength because it makes idea screening more efficient. Some ideas are quickly eliminated at the outset, so the group can use its time more wisely for evaluating the remaining ideas. However, early rejection of ideas also could be a weakness. Answering questions with a yes or a no at the first stage can result in overlooking ways to circumvent any apparent obstacles. Thus, the wording of the questions must be considered carefully.

FIGURE 11-3. Example of the Battelle method.

Perhaps the most important consideration is how the criteria are grouped together. What constitutes a low- or high-cost screen, for example, can be difficult to determine, especially when the criteria are highly subjective. To overcome this weakness, you can group the criteria into cost-homogeneous units within screens. That is, the criteria would be grouped according to similar costs of obtaining information about them. Of course, the number of criteria has to be large enough to do this. Another alternative is to use relatively low minimal passing scores, at least during the first pass through the screens. Should a large number of ideas survive all three screens on their first pass, minimal passing scores could then be raised in small increments and successive passes conducted through the screens until the desired number of ideas is achieved.

On the positive side, the Battelle method provides a relatively efficient means for screening ideas systematically. The involvement of a group in developing criteria for the screens also should increase group commitment to the final ideas selected. Finally, the use of weighted criteria in the scoring screens ensures that all criteria are not assumed to be of equal importance.

Electronic Voting

For groups that can afford it and like to jazz things up a little bit, electronic voting—especially via wireless keypads—may be an attractive choice. It may not be for all groups, but when time is short or a group has already spent time on evaluating ideas, electronic voting can be used quite appropriately. Note that this is different from using idea management software in which voting occurs online and participants may be in different locations; the electronic voting described here is intended for face-to-face groups.

A number of systems are available for a variety of price ranges. The major steps for this technique may vary depending on the system. Here is one approach:

1.Give each group member a seven- or nine-button remote and set up a projector and screen visible to all group members. With some systems, you might instruct the group members to rate each idea by pushing the button that corresponds to the value they would place on the idea. For example, if there are seven buttons, the first button would be used to signify little or no value to the idea, while the seventh button would be used to signify a very high value (the remaining buttons would be used to rate ideas in between those two extremes).

2.Have the group look at the vote tallies for each idea displayed on the screen.

3.Ask group members to examine the vote tallies and comment on any apparent inconsistencies. For instance, the group may note that an idea has been given a score of 7 points by three members and a score of 1 point by four members. In such cases, the inconsistency should be analyzed to help clarify why it occurred.

4.After discussing and clarifying all inconsistencies, have the group vote again and note the vote tallies that result. If no inconsistencies are observed with the second round of voting, terminate the process by selecting the highest-rated idea (or ideas); if inconsistencies are observed, repeat the procedure of clarifying and voting until no inconsistencies appear or a preestablished time limit has been reached.

The electronic voting method is very similar to the nominal group technique (NGT) described in Chapter 9. However, electronic voting has three major advantages over NGT’s voting procedure. First, votes can be tabulated almost instantaneously with electronic voting; considerable time can be consumed doing the same thing with NGT. Thus, quick feedback is provided to the group members. Second, the speed with which voting is conducted and the results tabulated make it possible to process a large number of ideas more efficiently. Third, using a memory bank with electronic voting permits rapid retrieval of vote tallies should a future examination of the votes be required.

Idea Advocate

In contrast to electronic voting, the idea advocate method, as described by creativity consultant Horst Geschka, emphasizes evaluation over selection. The group carefully analyzes the positive aspects of each idea to ensure that no potential solutions are overlooked. The group then selects the ideas on the basis of the outcome of these analyses. Four steps are involved in using this method:

1.Give each group member a list of previously generated ideas.

2.Assign each group member to play the role of advocate for one or more of the ideas. These assignments can be made according to whether or not a group member would be responsible for implementing an idea, was the original person who proposed the idea, or simply has a strong preference for an idea.

3.Read the first idea aloud and have that idea’s advocate discuss why it would be the best choice. Repeat this procedure for the remaining ideas.

4.When all the ideas have been discussed, have the group review the ideas and select the idea (or combination of ideas) that seems most capable of resolving the problem.

An obvious disadvantage of this technique is that it is not suitable for screening a large number of ideas. It will simply be too time-consuming for most groups to use for processing a large pool of ideas. The technique also may not work well if status differences exist within a group or if there are dominant personalities. Under such circumstances, all ideas are not likely to receive a fair hearing. Furthermore, the technique’s focus on only the positive features of an idea may result in a distorted picture of an idea’s value. If time permits, it may prove useful to incorporate some negative comments to provide a more balanced picture.

In spite of these disadvantages, the idea advocate technique can be appropriate when used in conjunction with more structured selection procedures. And it is especially appropriate when a large pool of ideas has been narrowed down to a more manageable number—for example, no more than two or three ideas for each member of a group. When only a few ideas are dealt with, each one is more likely to receive a fair hearing and a more in-depth analysis (assuming, of course, that status differences among the group members are minimal or can be controlled and that dominant personalities are not a factor).

Matrix Weighting

In contrast to the advantage-disadvantage technique, which assumes all criteria are equal in weight, the matrix weighting technique uses criteria that have been weighted according to their relative importance. As a result, the quality of ideas selected is likely to be higher. Matrix weighting is identical to the scoring screens used in the Battelle method (see Figure 11-3). Only the basic format used in setting up the technique is different. The steps are:

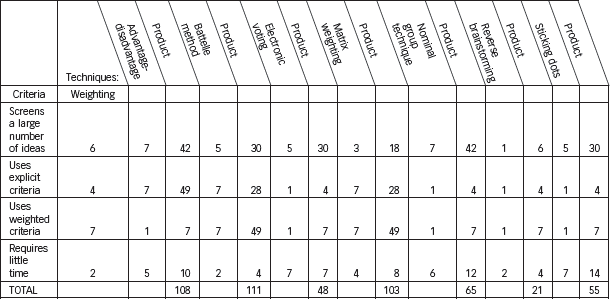

1.Construct a matrix table as shown in Figure 11-4. List the criteria down the left side of the matrix and the options being evaluated across the top. (Note that in Figure 11-2, the evaluation and selection techniques are used as examples of ideas to be weighted and evaluated.) In the column next to each option, create a Product column to record the mathematical product of multiplying a criterion importance rating by the rating for each option.

2.Using a 7-point scale (with 1 being low importance and 7 being high importance), rate the importance of each criterion. Use the criterion weightings column to do this. For instance, Figure 11-4 shows that “Screens a large number of ideas” is rated a 6 out of 7 in importance.

FIGURE 11-4. Example of the matrix weighting technique.

3.Using the same rating scale, rate each option (independent of the others) against each criterion. Record these ratings beneath each option. In Figure 11-4, for example, the advantage-disadvantage method is rated a 7 on its ability to screen a large number of ideas, a very favorable rating.

4.Multiply the weighting for each criterion by the rating given to each option on that criterion. Write the product in the appropriate column. For example, the criterion “Uses explicit criteria” was assigned an importance weighting of 4 and the option of the Battelle method was rated a 7 on this criterion. Thus, the product would be 28, as shown in Figure 11-4.

5.Add up all the products for each option and write the sum in the boxes in the Total column at the bottom of the matrix.

6.Select the idea with the highest total score and then decide if your choice reflects what might be expected. If it doesn’t, reevaluate the criteria importance ratings, the need to consider additional criteria, and the ratings given to each option.

For this example, screening a large number of ideas was viewed as being important (6), using explicit criteria was seen as moderately important (4), using weighted criteria was perceived as very important (7), and the requirement of little time was rated low in importance (2). These ratings are hypothetical, subjective, and could vary considerably depending on who is doing the ratings.

There are several cautions to observe when using the matrix weighting procedure. First, it can be a moderately time-consuming technique. It is more useful after a large number of ideas have been preselected. Second, the idea receiving the highest score may not always “feel” right to the group members. In some cases, group members may express dissatisfaction with the highest-rated idea but be unable to provide a rationale. When this occurs, additional criteria might be sought and the process repeated, or the ratings themselves might be examined to see whether any changes should be made. Finally, disagreement may arise among the group members over the ratings to be used. When disagreement occurs and cannot be resolved within the time available, voting can be used and the averages used for the ratings. Or if you have the authority, you could make the final ratings after considering the preferences of the group members.

On the whole, the matrix weighting technique is a popular procedure with many groups because of its systematic way of processing ideas for selection. In addition, the discussions about the criteria and ratings can help to clarify each group member’s understanding about the ideas and what is required to ensure development of a high-quality solution. Consequently, group members are often more likely to accept the idea selected and be committed to its implementation.

Nominal Group Technique

The steps involved in using NGT have already been discussed in Chapter 9. The voting procedure is described again here because it contains the steps that deal with the selection process. NGT uses the following steps to vote on ideas:

1.Discuss each idea in turn to clarify the logic and meaning behind it. During this time, make it clear to the group members that the purpose of this step is to clarify their understanding of ideas and not to debate the merits of the ideas. In this regard, you should pace the discussion to avoid spending too much time on any one idea and to avoid heated debates.

2.Conduct a preliminary vote on the importance of each idea.

a.Have each group member select a few of the best ideas out of the total. (The group leader should determine the number of ideas to be chosen—for example, 10 percent of the total. A number of ideas between five and nine usually works well.)

b.Instruct the group members to write each idea on a separate 3- by 5-inch card or sticky note and to record the number of the idea in the upper left-hand corner of the card.

c.Have the group members silently read the ideas they have selected and rank them by assigning a 5 (assuming five ideas were selected) to the best idea, a 1 to the worst idea, and so forth, until all the ideas have been ranked. Then have them rank each idea by writing the rank in the lower right-hand corner of each card and underlining it three times (to prevent confusion with the idea number).

d.Collect the cards, shuffle them, and construct a ballot sheet. Record the idea number in a column on the left side of the sheet, and record the rank numbers given to each idea next to the idea numbers. For example, if idea #1 was given rank votes of 5, 2, and 3, this would be recorded as 5-2-3.

e.Count the vote tallies and note which idea received the most votes (the highest total score).

f.Terminate the selection process if a clear preference has emerged. If no clear preference is evident, go on to the next step.

3.Discuss the results of the preliminary vote by examining inconsistencies and then rediscussing ideas seen as receiving too many or too few votes. For instance, if an idea received four votes of 5 and three votes of 1, the meaning behind the idea might be discussed to see whether there were differences in how the idea was perceived. Emphasize that the purpose of this discussion is to clarify perceptions and not to persuade any member to alter his or her original vote.

4.Conduct a final vote using the procedures outlined for the preliminary vote (step 2).

The idea selection portion of the NGT procedure has major strengths in ensuring equality of participation and in eliminating status differences and the harmful effects of a dominant personality. The procedure also provides a highly efficient means for processing a large number of ideas. Furthermore, NGT voting concentrates disagreements on ideas instead of individuals.

On the minus side, NGT does not use explicit evaluation criteria. The rankings are produced by group members using their own criteria, which might or might not be shared by other group members. For this reason, the NGT voting procedure might be improved by asking group members to consider a general set of criteria for all to use in ranking their ideas. If this procedure is added, there may be fewer inconsistencies in the final vote tally and less need to repeatedly discuss ideas for clarification.

Reverse Brainstorming

The classical brainstorming technique described in Chapter 9 is designed to generate a large number of ideas. Reverse brainstorming is also concerned with generating ideas but not for solving a problem. Instead, the ideas are couched in terms of criticisms of previously generated ideas. Thus, this technique uses a procedure opposite that of the idea advocate method: Negative rather than positive features of ideas are sought. The major steps of reverse brainstorming are:

1.Give each group member a list of previously generated ideas (or write the ideas on a chalkboard or flip chart).

2.Ask the group members to raise their hands if they have a criticism of the first idea (or each member can be systematically given a chance to offer a criticism).

3.When all the criticisms for the first idea have been brought out, ask the group to criticize the second idea. Continue this activity until all the ideas have been criticized.

4.Instruct the group to develop possible solutions for overcoming the weaknesses of each idea.

5.Select the idea (or ideas) with the fewest weaknesses that cannot be overcome or circumvented.

As with the idea advocate method, reverse brainstorming can be extremely time-consuming if a large number of ideas are being processed. As a result, it is best to use this technique when the original idea pool has been narrowed down some. Perhaps the major weakness of this technique, however, is its emphasis on the negative. Stressing what is wrong with every idea may lead to a negative climate not conducive to creativity. Although a climate conducive to creativity is more important during idea generation, the lack of such a climate during evaluation can make it difficult for the group to combine or elaborate on ideas (in a positive manner) before making the final selection.

The major strengths of reverse brainstorming are the amount of discussion devoted to each idea and the provision for developing ways of overcoming idea weaknesses. While analyzing each idea, possible implementation obstacles may be suggested and dealt with, which can ensure more successful implementation. Looking at ways to overcome idea weaknesses may reduce the negative atmosphere that often develops in a group after it spends so much time criticizing the ideas. Furthermore, looking at ways to overcome weaknesses should also increase the probability of implementation success.

Although reverse brainstorming does have advantages, it probably could be used more effectively in combination with the idea advocate technique. This would provide a more balanced evaluation of each idea and not be as likely to result in a negative climate. Of course, the decision to add another technique has to be weighed against the increased amount of time that will be required.

Sticking Dots

Sticking dots is one of the simplest, most time-efficient voting methods available. Members each receive a fixed number of self-sticking, colored paper dots with which they can indicate their idea preferences with minimal time and effort. The steps involved are:

1.Display a previously generated list of ideas on a flip chart or on sticky notes attached to a bulletin board.

2.Give each group member a sheet of self-sticking colored dots. Each member should receive a different color, and the number of dots should equal about 10 percent of the ideas to be evaluated.

3.Ask the group members to vote for ideas by placing dots next to ideas they prefer. They may allocate their dots in any way they wish. Thus, all of one member’s dots may be placed next to one idea, only one may be placed next to one idea, half the dots may be placed on one idea and the other half on another idea, and so forth.

4.Count the votes received by each idea, and select the ideas with the most votes.

Variations include the following:

1.Restrict participants to voting with no more than two or three dots for any one idea. This might help keep certain ideas in the running and prevent people from engaging in block voting.

2.Give participants three different colors of dots and have them vote using each color in succession based on ideas previously receiving votes. For instance, if twenty out of fifty ideas receive at least two votes with red dots, give the participants 10 percent of that number (two) and have them vote only on the red dot ideas using green dots. The same process then might be followed using yellow dots.

In addition to the relatively small amount of time required to use this method, there is the advantage of the sense of equal participation that it affords group members. Placing dots next to ideas is an activity in which all members have an opportunity to participate on an equal basis. Furthermore, should questions arise about the voting distribution, the color coding of the dots makes it relatively easy to ask people why they voted the way they did. And it provides an opportunity for additional discussions about specific ideas.

There are, however, several disadvantages associated with this technique. First, and perhaps most significant, the lack of anonymity may result in a certain degree of voting conformity. By seeing how the vote clusters develop, some members may feel pressured to vote in a similar manner. Second, no discussion is conducted on criteria to use in making voting decisions. Finally, there is no built-in mechanism for clarifying the meaning and logic underlying the ideas and for examining voting inconsistencies. This technique could be improved by conducting a discussion on the criteria to be used and providing time to clarify ideas and to examine inconsistencies in the voting patterns. However, the problem of voting conformity would remain.