CHAPTER SIX

BUREAUCRATIC ORGANIZATION AND CULTURE

In July 1917 the French pianist Erik Satie wrote Sonatine bureaucratique, a four-minute piece that parodies Sonatina in C Major op. 36, no. 1 by Muzio Clementi (1752–1832). Just listening to the music, it is clear that it is about busyness without substance. Satie supplied his own narrative alongside the music, describing a bureaucrat going to work, loving his office, but doing little. He wrote this possibly in part with an eye on conservatism in art, targeting and mocking those who would not embrace fresh ideas; and he certainly wrote it as an accusation of traditional formal procedures (in music as well as anywhere) (Hare, 2005, pp. 63, 82, and 87). Satie's Sonatine is just one example of how bureaucracy is stereotyped in the arts. Two other examples are Franz Kafka's novels The Trial and The Castle. The arts reflect the stereotypical understanding of bureaucracy among people at large. A sample of these stereotypes include that bureaucracy is too big and suffering from “elephant disease,” (Eisermann, 1976, p. 50), that bureaucrats multiply like rabbits (Zehm, 1976, p. 52), that they are more concerned with the offices they hold—cf. Satie—than with its duties (DuBasky, 1990, p. 337), that they are mediocre and merely shuffle papers (Von Mohl in Kaltenbrunner, 1976, p. 7), that they are “drunk with power,” (remark by U.S. Senator Ashurst, as quoted in Rosenbloom, 2003, p. 169), that they are officious, and that they are impersonal and dehumanized. With regard to this last characterization, they once were even described as having substituted “technical performance in sexual intercourse” for lovemaking (Hummel, 1977, p. 51; nota bene, Hummel told one of the authors of this volume once how, following criticism, he removed that particular quote from subsequent editions of his book).

Stereotyping, of course, is a shortcut to understanding and circumvents real thinking about the nature of something. To our knowledge, no composer, novelist, or any artist for that matter, has ever attempted to capture the real nature of bureaucracy. Scholars can define and have described bureaucracy in terms of its structural features (Section 1), and we have already seen how bureaucracy has become the predominant organizational model across the globe (Chapter 3). It has been around since prehistory, but until the late eighteenth/mid-nineteenth century its role and position in society was very different from what it is today (Section 2). As it is, the bureaucratic stereotype has much more to do with that lingering, historical legacy than with the actual performance of bureaucracies today.

While bureaucracy as organizational structure can be found everywhere, how it functions varies with the societal culture in which it is embedded. Understanding that starts with the societal level of culture (Section 3), where it becomes clear that there are significant differences between and even within cultures. These differences have impact upon organizational culture (Section 4); that is, how people perceive the organization. This, in turn, influences the individual level of culture (Section 5). In each of these sections we shall briefly describe the stereotypical and the actual conception of bureaucracy. In the final section we will revisit the role and position of bureaucracy in contemporary societies: Can we live with it, can we live without it?

Defining Bureaucracy: The Influence of Max Weber and His Fears

To understand the role and position of bureaucracy in contemporary society, it is necessary to compare it from three perspectives: two contemporary and one historical. The most familiar contemporary perspective is the stereotypical view many people have of bureaucrats (we prefer the term civil servants), and we have already had a taste of that in the introduction to this chapter. The second contemporary perspective is a formal definition of bureaucracy as developed by Max Weber in the early twentieth century. The historical perspective, how and why it came about, will actually help to explain why the stereotype of bureaucracy emerged and why it is especially identified with government.

Weber may be partially blamed (if that's the right word) for that, for he regarded bureaucracy as part of the state that surrounded us like an “iron cage.” (Baehr, 2001). To him and many of his contemporaries the seemingly sudden proliferation of bureaucratic organization in the context of rapid industrialization was baffling, even threatening, to the individual as well as to society at large. Individually, people felt alienated from the natural world they had known for millennia, and tried hard to salvage some sense of normalcy. It may appear strange in the mind-set of those living in the twenty-first century, but naturism was one of the ways—at least in Germany—that people felt they might reconnect with nature. Nude hiking and sunbathing were popular for a while (Hau, 2003). Since 1906, Weber used to sit at noon on his balcony for an hour, smoking his pipe, in Adam's costume (Radkau, 2009, p. 377). In society, Weber felt, the advent of bureaucracy was particularly and potentially harmful to democracy, sighing that the future was to bureaucracy and wondering whether democracy would not be overshadowed completely just as easily as human values and feelings could be overpowered by it.

Perhaps the following sounds naïve or displays an ignorant optimism, but would Weber change his verdict had he had a chance to talk with, for instance, Patrick Dunleavy? The latter showed that bureaucracy has been very able to restrain itself, and able to pursue reforms and budget and personnel cuts of its own accord (1991). There is more, however, that might persuade Weber to nuance his assessments. Today, bureaucracy is all around us. Any organization, public, nonprofit, and private alike, of a certain size is structured and operates as a bureaucracy. Governments all over the world are organized as multiple bureaucracies. However, any multinational, any sizeable business is a bureaucracy. Obviously, many, if not all, businesses start small. With Paul Allen and Bill Gates in jeans, Microsoft started small (although with ample funding sources from Gates's parents), but became a giant, and it is a bureaucracy. Any oil company that made it big after the first gusher could not avoid structuring itself as a bureaucracy. Big nonprofits such as Greenpeace, Habitat for Humanity, and the Red Cross would not be able to do their good works were it not for being organized as a bureaucracy. Hence, bureaucracy is not only an “iron cage” or prison, it is also “an essential scaffolding of thought” (Crowther-Heyck, 2005, p. 117), a prerequisite structure wherein an entire body of thought can develop, and that even can be a playground where the various climbing, swinging, and teetering toys and so forth will structure play but do not determine how the play is conducted or pursued (Klagge, 1997). Obviously, bureaucracy can be an iron cage or prison, especially for those who overstep the boundaries of what is considered acceptable behavior. That it is also a scaffold or prerequisite structure for thought is perhaps best exemplified in a body of law. And it certainly is a playground, for it provides its occupants with the means to do what an individual cannot do. It enables behavior and action that transcends individual capabilities.

The metaphor of the “iron cage” confirms the stereotypical perception of bureaucracy; the metaphor of the playground is more benign, suggesting even that it is not dehumanizing. We will come back to this latter point, but shall now look at Weber's definition. In his view bureaucracy can be regarded as an organizational structure and as a personnel system (Chapter 8). The eight dimensions of bureaucracy as an organizational structure are easy to recognize.

Eight Dimensions of Bureaucracy as Organization1

- continuous administrative activity,

- formal rules and procedures,

- clear and specialized offices,

- hierarchical organization of offices,

- use of written documents,

- adequate supply of means (desk, paper, office, and so on),

- nonownership of office (separation of office from officeholder),

- procedures of rational discipline and control.

In incompetent or even wrong hands, it is easy to see how each of these dimensions can degenerate into an overbearing presence of the state, as is the case in totalitarian systems and which is so beautifully captured in the image of the always-turned-on TV screen in people's living rooms in Orwell's 1984 (dimension 1); into laziness, officiousness, and formalism (dimensions 2 and 8); into “turf fights” about the authority invested in an office (dimension 3); into rigid adherence to lines of command (dimension 4); into red tape, especially when documents appear to be full of “legalese” (dimension 5); and into theft of public property (dimension 6). In those cases bureaucracy (as the “good” type of organization) slides into bureaumania or bureaucratism (compare to the three types of political systems in Chapter 5). The one dimension that seems more difficult to be manipulated by the human condition (that is, by the sins of envy, gluttony, greed, lust, pride, sloth, and wrath) is dimension 7. However, while people may no longer be able to sell or inherit their public office as they could and did in the past, they may well succumb to envying someone else's position or take pride in the office they hold. In any of these cases, the public interest has been superseded by individual desire. It is important to note that Weber never said that bureaucracy was efficient, only that it was more efficient than other known types of organization. What is implicit in his writing, as Gyorgy Gajduschek pointed out, is that bureaucracy caters to “uncertainty reduction” because it enables political officeholders, civil servants, researchers, and citizens to reconstruct past outputs and procedures from written records and it helps them to plan for the future (policy making and implementation) through its predictability and calculability (Gajduschek, 2006, p. 716).

Earlier we suggested that bureaucracy is subject to manipulation and abuse. The first to suggest that bureaucracy's rationality and efficiency can potentially turn into irrationality and inefficiency was Robert Merton in his landmark 1940 essay “Bureaucratic Structure and Personality” (1952). What if the impersonal application of rules is exaggerated to the point that they become a goal in themselves, serving the procedures of the organization rather than the needs of citizens? What if bureaucracies measure their own performance in various ways and stop sharing best practices for fear of losing their ranking? What should come first, organizational performance or a citizen in need? The popularity of performance measurement in the United States has been spreading to other countries, and it seems that Merton had a point when saying that people in bureaucracies may focus more on proper application of rules and on measuring their own performance than on the objectives for which it exists today: to help citizens. In the extreme, bureaucracy has been used as an instrument of evil (Adams and Balfour, 2004; Adams and others, 2006) and not only in the recent past. It will be used so again, but that is because of the human condition. (With a nod to the ongoing American debate about gun control, this may sound similar to the argument that guns do not kill people, but that people kill people. However, this reasoning by analogy does not work because bureaucracy cannot be bought and sold by individuals. Furthermore, nowadays people do not need guns in their homes. It made sense to have weapons when living in sparsely populated areas where help in dire circumstances might not be readily available. In the densely populated, highly urbanized communities of the modern world guns should be in the hands of law enforcement officials only.)

There is a third reason why in democratic societies, bureaucratic organization does not fall prey easily to the human condition. When asked: “What do you think about government?” people often resort to the stereotype of it being too big, too little transparent, too costly, too incompetent, and so forth. When asked, however, what they think of specific government services they have had experience with, the assessment is very different, even more so when asked about the quality of service from a specific public servant (for instance, school teacher, police officer, judge, social worker). The empirical evidence since the 1960s is consistent about the extent to which citizens are content and satisfied with the performance of individual bureaucracies and their civil servants (for instance, police precinct, elementary school, fire department) (Goodsell, 2004). The two authors of this volume know quite a few career civil servants, just as any reader will. And, yes, they have known some who were “not up to snuff” and should never have been appointed to public office. Again, any reader will be able to come up with some examples of her/his own. Everyone knows that “a few rotten apples will spoil the barrel.” If there is truth to this proverb, we can assume that the large majority of career civil servants are decent people who try to do the best they can with the limited resources given to them. Unlike their counterparts in the private sector, they cannot raise revenue (that is, taxes) indiscriminately, for that decision rests with political officeholders and, in turn, with an electorate that recognizes the wisdom of Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes: “I like to pay taxes. With them, I buy civilization.” We can also assume that in the fishbowl that bureaucracy ultimately is, those who do not live up to expectations will be reprimanded and may even lose their jobs.

It may seem that we have transgressed from presenting a formal and neutral definition of bureaucracy into a defense of its existence, but we had a very good reason to do so. With his formal and ideal-typical definition of bureaucracy, Weber accomplished, inadvertently, two objectives in one stroke. First, he identified the elements of an organizational structure that he saw spreading like wildfire. Like his contemporaries he had neither knowledge about nor experience with this type of large-scale, hierarchical organization, and he wanted to warn his fellow humans against the possible dangers. Second, he defined an organizational structure for which no historical precedent existed. We will substantiate this statement in the next section. Meanwhile, Weber's definition of bureaucracy has become so common that it is almost difficult to imagine that it only characterizes the complexity of the organization of government from the late eighteenth century on (Morony, 1987, p. 7). That raises the question: When and why did bureaucracy appear in human history, and how did that bureaucracy in the past differ from its contemporary manifestation?

Bureaucracy in the Evolution of Human Communities: The Origin of the Stereotype?

The geoarchaeologist Fekri Hassan suggested that population growth occurred before the emergence of the state (1983), and that the first stages of expanded social cooperation were primarily economic or technological rather than militaristic and expansionist by nature (Masters, 1986, p. 161). In other words, conflict or war was not the primary cause for the emergence of the state.

Perhaps the earliest bureaucracies were those where people recorded transactions of goods. Indeed, the earliest known examples of writing are records of trade. We can safely assume that bureaucracies emerged at least 10.000 years ago in sedentary communities for both biological and power-political reasons.

The biological reason is perhaps indirect, but nonetheless real. Survival of the species depends upon cooperation and upon the ability to assure that genes are passed on to the next generation. At the end of the Paleolithic period and the beginning of the Agricultural Revolution some 10,000 years ago, the number of people who roamed Earth has been calculated to be about 10 to 15 million, about one per square mile (Corning, 1983, p. 304). It is easy to see that the globe back then was relatively empty, with small hunter-gatherer bands of 30–50 members living far apart from each other. We assume that these societies were almost completely egalitarian, and that cooperation came “naturally” since most members must have been related by kinship. Once people settled down and discovered the ability to produce agricultural surplus, their numbers quickly increased to about 50 million at the time that the first states appeared about 5,000+ years ago. In another 3,000 years there would be about 300 million people (Hassan, 1997, p. 6). Such rapid growth in population size requires institutional arrangements that secure that people are to some degree protected from one another (we cannot assume that all people will restrain their behavior so that others are free [see Chapter 5]) and from outside aggressors.

It has been long debated in anthropology whether the state emerged because of a need for intragroup cooperation or because of intergroup conflict (Masters, 1983, pp. 177 and 185). It might actually well be both, but for the purposes of this chapter and book, we need not address this question. What is important, though, is to note that within the group selfish behavior may occur, while conflict between groups increases chances of altruistic behavior within the group. Selfish behavior is visible within groups when, for instance, people strive for advancement in social status and for emphasis upon status differentiation. As we argued in Chapter 2, social stratification will occur in societies where people no longer know everyone else. However, the group will operate as one when threatened by the outside world, each member recognizing that altruistic behavior will protect the group. In fact, altruistic behavior is needed when pursuing territorial expansion. In that effort, some individuals may lose their life, but the continued existence of the group is assured.

The power-political reason for the emergence of bureaucracies is that in socially stratified communities those in power will not be able to monitor the behavior of all members. In order to maintain some degree of control they need a support structure, a bureaucracy with people who do their bidding. These premodern bureaucracies are extractive organizations; they basically exploit the natural resources (produce, labor) of their populations to benefit the ruler(s) and the ruling class. Premodern bureaucracies are generally not service providers in the way that modern bureaucracies are. They serve as a “loyal and personally ascribed cadre of supporters” of the ruler or the ruling class, not as servants of the people (Yoffee, 2005, p. 140).

The more complex of these premodern bureaucracies were problem creators rather than problem solvers (Paynter, 1989). That is, the adaptive capability of any political-administrative system comes under stress once the political leadership, through a top-heavy bureaucracy, makes impossible demands upon the productive sector (Butzer, 1980). Indeed, civilizations declined because their governments became too demanding. In early modern Europe, discontent with government was generally fueled by unreasonable and extraordinary taxes, leading to tax riots and—sometimes—revolution (such as the American and French Revolutions).

Millennia of experience with a ruler-oriented bureaucracy fed the characterization that bureaucrats are only interested in advancing their own power, security, and comforts as long as that happens within the orbit of the ruler. In other words, those working in bureaucracy created selective benefits for themselves (Masters, 1986, p. 156). In the middle of the nineteenth century, Countess Bettina von Arnim (1785–1859), a politically active author in Prussia, wrote that high-level court advisers and ministers shielded the king from hearing about the plights of the people, and advised that government bureaucracy and corruption could only be countered by a people's monarch (Hallihan, 2005, pp. 58 and 94).

It is premodern bureaucratic behavior that is reflected in the stereotypes that people still hold and that is found in novels of administrative fiction. An early example of a discussion about public servants in English novels is provided by Humbert Wolfe (1885–1940; a poet, and a civil servant who rose to high rank in the Ministry of Labor), who describes Charles Dickens's portrayal of those working in “The Circumlocution Office” in Little Dorrit as so cartoonesque that “whether he was misinformed or not, he has presented a picture of red tape, of callous indifference to justice and honour, of ignorance, of nepotism, of sheer overwhelming machine-like stupidity that has not been erased from the canvas of the Civil Service in the sixty odd years since it was written.” (Wolfe, 1924, p. 44) Can it be that, no matter how well civil servants today do their work, it is simply very hard to shake off the image of bureaucracy handed down from the past and that became a stereotype? It does not take much for the stereotype to be confirmed. Wolfe concludes that two main types can be found in fictional work: the “mandarin-parasite” (such as the one Von Arnim described) and the “slave” who is destined to servitude for life (Wolfe, 1924, p. 41; see also Goodsell and Murray, 1995, p. 8; Samier, 2007, p. 8). To be sure, the mandarin-bureaucrat was always a member of the societal elites, the patricians, who regarded the populace as plebeians. From among these plebeians the bureaucrat-slaves were recruited to perform lowly tasks and functions with no access to policy and decision making. Bureaucrat-mandarins and bureaucrat-slaves can be found in numerous countries, but in democracies with highly professionalized bureaucracies they are less likely to abound. Unfortunately, we will find people in any organization, whether public, nonprofit, or private, who pursue their own goals rather than serve the public and organization's interest and who violate the intent of one or more of the dimensions of Weber's ideal type. No type of organization or set of rules can be developed that will constrain the few tempted to abuse the system. We suggest that modern public bureaucracies in Western societies have come closest to constraining the chance that individual interests trump those of the public at large. With regard to bureaucracies in the private sector, it has proven to be more difficult to constrain individual interests and then especially at the higher levels in companies and corporations (Khurana, 2007). Sadly, there are plenty of examples in the United States alone (see “After Enron, the Deluge.”).

It is in the course of the nineteenth century that bureaucracies no longer only serve a ruler or a ruling class, but serve a citizenry and their government. Also, government bureaucracies no longer only extract resources from the population, they also provide many services. Bureaucracy today is very different from its historical counterpart. It will continue to do its work, irrespective of the political party or parties elected into executive office. And it can continue to do its work because, in a democracy, it is almost impossible that one or a few career civil servants can acquire the power of a dictator with the exception perhaps of those in a military capacity. We reiterate that in democracy it is more difficult for those in power to use bureaucracy toward their own ends; in other words, bureaucracy is the “scaffold” that makes democracy work.

It has been suggested that democracy has biological, organic roots as well. Just like apes, people accept subordination when it is the only available alternative to being isolated from the group. But democracy is different. Consider the following: “If everyone really would like to be omnipotent and therefore the one dominant individual, and if really no one can be omnipotent, then people would rather compromise by being equal than by being subordinate. If the opposite were true—if people and/or monkeys preferred to be subordinate than to be equal—then there would be no more fights for top or middle positions.” (Davies, 1986, p. 360; emphasis in original) The desire for democratic government is based on the premise that all people are created equal, and that it emerges when other and higher-priority needs can be satisfied without accepting subordination to a ruler. This intertwinement of democracy and bureaucracy is characteristic for modern societal culture, and we saw already in Chapter 5 and shall see again later that bureaucracy has more exploitative features when it is operated in a less or nondemocratic environment.

Societal Culture

In any study of comparative government it is extremely important to consider the societal culture in which government and its organizations are embedded. It has been popular to simply characterize administrative cultures in terms of groups or families of countries. For instance, Martin Painter and Guy Peters (2010, p. 19) distinguished between nine traditions: Anglo-American, Napoleonic, Germanic, Scandinavian, Latin American, Postcolonial South Asian and African, East Asian, Soviet, and Islamic. However, this type of categorization is a bit of a hodgepodge, mixing geographical, historical, and cultural features without explaining why this administrative tradition is there in the first place. It is far better to characterize culture in terms of specific features. In this section we look at specific features of societies at large, using the work of the American anthropologist Edward Hall, the Dutch sociologist Geert Hofstede, and the Swedish political scientist Jon Pierre.

In a study about the nature of time in different societies E. Hall suggested that governments and businesses in the Western world are characterized by monochromic time. In such M-time cultures, as he called them, time is strictly regimented. People carefully schedule their activities and can plan a specific amount of time, days, weeks, even months ahead in an agenda. How it is possible to know what amount of time is needed for a certain discussion is not clear, but start and end time of a meeting are scheduled. All sorts of language and phrases indicate how valuable time is considered to be: It can be “wasted,” it can be “saved,” it can be “spent,” it can be “made up,” and it even can be “lost.” Clearly, none of these are literally possible, but it is how people in countries such as Germany and the Netherlands think. In polychromic time societies (P-time) people are not very strict with scheduling, they may do different things simultaneously, and they have certainly a much more relaxed sense of time. The difference between M-time and P-time societies also translates into the extent to which people need trust before they can interact in a meaningful way.

Hall suggests that P-time cultures are high-context cultures where people first need to get to know each other and establish trust before they can work together and/or do any business. By contrast, low-context cultures do not require such deep interpersonal knowledge, and personal life and work are very segregated. As a consequence, detailed background information is necessary, and is even formalized as in, for instance, Charles Lindblom's “partisan analysis.” In P-time cultures people are also more patient than those in M-time cultures (Hall, 1983, p. 45–47; Hall and Hall, 1990, p. 9). Policy evaluation is less important to public servants in P-time cultures, because it is considered not in sync with the sense of harmony between people. They rely more on intuitive understanding, while their M-time counterparts pursue policy evaluation and do so upon fact-based analyzed reasoning. Norway and Sweden are considered P-time cultures, while the United States is basically an M-time culture (Christensen and others, 2003, pp. 57–58). Germany and the Netherlands are also more M-time cultures, while Mediterranean countries (perhaps with the exception of Israel) and many developing countries can be more easily characterized as P-time cultures.

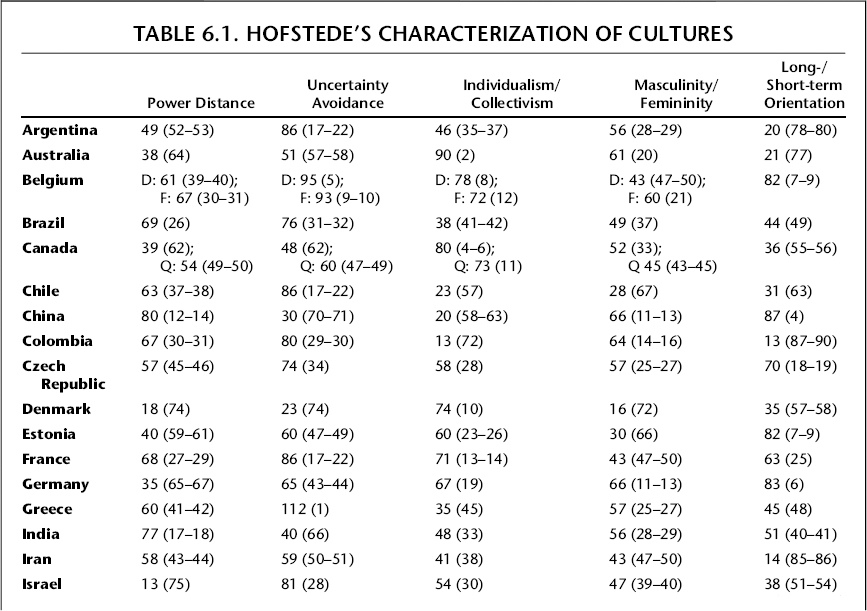

Hofstede's work is an excellent example of how a societal culture can be captured in dimensions and subsequently measured. The dimensions he developed out of a large survey of IBM employees in the late 1960s are illustrated in various settings (family, school, state, and workplace). We shall briefly discuss each of his five dimensions with examples of the role and position of the state.

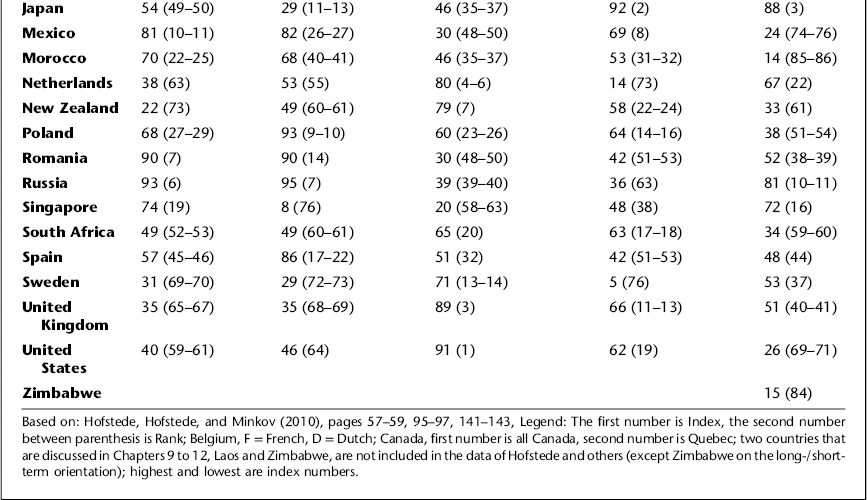

The first dimension, large or small power distance, refers to the extent that supervisors and subordinates are separated. In countries with a low power distance index (PDI), the relationship between boss and employee is one of interdependence and consultation, and authority is based on expert knowledge and formal position rather than on kinship, friendship, and charisma. In large power distance countries governments are often more oligarchic or autocratic. Northwestern Europe and North America are prime examples of areas with a small power distance where hierarchy exists but basically because it is convenient. Open displays of power and status symbols are “not done.” Organizations with small power distance tend to emphasize decentralization. The number of managerial levels is less than in large power distance countries. With regard to government, small power distance countries tend to change their political system more commonly in an evolutionary rather than a revolutionary way. There is more discussion and much less violence in politics; and they tend to have pluralist governments based on majority voting. Finally, countries with a small power distance are also among the wealthier in the world and with a strong and large middle class. Generally, in most low power distance countries income differentials are relatively small, tempered by a progressive tax system. The United States, though, is different, since income differences are very large, and the tax system not very progressive. Examples of low PDI countries include Austria, Germany, the Nordic countries, the Netherlands, and Anglo-American countries. In large power distance countries, the situation is quite different. Officials show their status; organizations are much more top-down structured with clear boundaries between supervisors and subordinates. The political system is much less easy to change unless through revolutionary force. Politics in general tends to be more violent, and political party competition is more limited. This is a situation more characteristic of developing countries (Hofstede and others, 2010, p. 83). Asian, Eastern European, and Latin American countries have high PDI. In Table 6.1 we have listed the PDI and the rankings of the countries discussed in Chapters 9 to 12.

A second dimension of organizational and societal culture is the degree of uncertainty avoidance, which is defined as the extent to which members of society feel threatened by ambiguous or unknown situations (Hofstede and others, 2010, pp. 191 and 223). Do people experience job stress, do they rely on organizational rules rather than on each other in case of conflict, and do people stay with one company throughout their career (Hofstede and others, 2010, pp. 190)? In countries where uncertainty avoidance is high, the workplace is generally populated by people with long tenures, while in countries with low uncertainty avoidance turnover or attrition is much higher. With regard to government, high uncertainty avoidance countries such as Greece, Portugal, Latin American countries, and Japan have a bias in favor of precision and punctuality and thus, for instance, emphasize detailed laws. Many civil servants have a law degree. In low uncertainty avoidance governmental cultures civil servants have wide-ranging educational backgrounds, and examples include Israel, the Netherlands, the Nordic countries, and Anglo-American countries.

It is also observed that high uncertainty avoidance countries generally have a negative attitude toward political and administrative officials and the legal system. That being said, how can it be that the United States is characterized as a low uncertainty avoidance country while having a very high distrust of government? The answer is simple. We must keep in mind that these dimensions of culture are generalizations. The ranking of countries in each of these dimensions suggests a rigidity that in reality does not exist.

The third dimension is that of individualist and collectivist cultures, where the designation “individualist” denotes a society where the ties between individuals are loose, where people are expected to take care of themselves (ibid., p. 92). It will not come as a surprise that the United States was ranked highest on individualism. Individualist societies pay more attention to the task at hand than to the relationships between employees and between employees and supervisors. The nature of the subordinate-manager relationship is one based on a labor contract, and it is certainly not perceived like an extended family as is the case in more collectivist countries. In individualist countries, government is supposed to play a restricted role in the economy. Government also is expected to treat everybody as equal under the law, while at the same time individual freedom is regarded higher than the ideology of equality of condition. Nearly all wealthy countries score high in individualism. However, it is suggested that pure individualist and pure collectivist societies do not exist.

In collectivist countries the individual is not as important as the cohesive in-group or as the society at large. Government is also less inhibited and adopts an interventionist role for the good of the whole. It is irrefutable that the United States has developed significant elements of a collectivist society. The policy and service reforms of the 1930s with regard to social security and employment and the 1960s changes concerning civil rights are illustrative of this. The welfare states of Western Europe are more collectivist than the United States, yet they do protect individual freedoms to a considerable extent. Japan is like a Western welfare state but considerably more collectivist than Western European countries are. While industrialized countries tend be more individualist, there is no strict link between the two. Indeed, despite industrialization East Asian countries such as Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore, and South Korea are still quite collectivist. Less democratic developing countries are generally leaning more toward collectivism. Overall, collectivist societies outnumber individualist societies (Hofstede and others, 2010, p. 94). One characteristic of organizational culture and climate in the public sector is that at the middle and higher levels in most countries it is not very representative of the composition of the population. While governments in the Western world have led by example and consciously pursued efforts at increasing the representativeness of women and of minorities, this is still far from realized. This issue relates to the degree to which organizations and countries have masculine or feminine cultures (Hofstede and others, 2010, p. 180). In a masculine organizational culture gender roles are clearly defined: The male holds the main job, holds a position of authority in the family, and is expected to be more assertive; the female may hold a clerical job requiring her to serve others or may simply be expected to be an at-home mom, and she is also expected to be more caring and tender.

In feminine organizational cultures, gender lines are blurred or even nonexistent, and males and females can both perform the same functions. Hofstede's research placed the United States among other masculine countries such as Japan, Germany, Great Britain, and Poland, while the Scandinavian countries and the Netherlands are highly feminine countries. To be sure, this means that men also change diapers and do the laundry, while women may change the tires and paint the house. With regard to government, masculine societies support the strong competitor, are more focused on correcting behavior, and embrace an adversarial political-administrative system. Public-sector organizational culture in the United States has features of a marketplace where only the strong survive, and its bureaucracies have overlapping competencies and must compete for the budget.

One final dimension of societal culture is its short- or long-term orientation. Short-term cultures seek immediate gratification of needs, demand measurable value for money, and subject organizations that implement policies to extensive performance measurement. The electoral cycle may focus on the short term and, in that case, elected officials will not be inclined to think too much beyond surviving the next elections. With respect to electoral cycle, the United States is among the shortest in Western countries. What impact does a short-term orientation have upon policy? One example can clarify this. In countries with a short-term orientation, the purpose of punishment is expressed in the degree to which people and their governments tend to lock their criminals up and keep them apart from society. In individualist countries, the criminal is sooner considered a problem because of personal behavioral deviancy than because of societal circumstances. Among Western countries the United States ranks first by far with regard to violent crimes such as homicide, rape, and robbery, and its incarceration rates are also considerably higher than in any other country. Private organizations in short-term orientation countries tend to focus more on the bottom line and on this year's profit. Politics and administration focus more on promises that can be achieved in a short span of time. However, some of the largest government projects in the United States have taken decades to unfold, so it is not as if short-term orientations automatically prohibit long-term policy and projects (Light, 2002). It is necessary to point out that we have defined short- and long-term differently. Hofstede defines short-term orientation as focused on fostering virtues oriented to future rewards (through perseverance and thrift), while long-term orientation fosters virtues that are related to the past and the present (such as respect for tradition, preservation of face, and fulfilling social obligations Hofstede and others, 2010, p. 239). China, South Korea, and other East Asian countries as well as Puerto Rico score high on long-term orientation, while Colombia, Iran, and Argentina score low (see Table 6.1).

It is important to keep in mind that how these dimensions manifest themselves over time is subject to change. A group of scholars replicated Hofstede's survey of the late 1960s 25 years later and found that the United States had simultaneously become more feminine as well as much stronger on uncertainty avoidance, while rankings for power distance and individualism had not changed much (Fernandez and others, 1997). It is equally important to emphasize that the value dimensions, and thus administrative cultures, vary from country to country; every government nowadays operates through sizeable bureaucracies (that is, structure), but how these bureaucracies function internally (their culture) is much more determined by features of bureaucracy as a personnel system than as an organization (see Chapter 8).

The third characterization of societal culture is represented by the distinction Jon Pierre made between the public interest and the Rechtsstaat models of the political-administrative system (1995). In the public-interest model the emphasis is on pragmatic and flexible decision making; it also allows for radical reforms that stress managerial change. In this model the role of the state is less extensive than that in countries with more of a Rechtsstaat model system. Public-interest states are more performance driven and market oriented, and examples include Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States (Pollitt and Bouckaert, 2011, p. 73). The Rechtsstaat model is one where legislative authority is the primary mechanism upon which government works. Any effort at managerial reforms must fit the legal framework, and so these systems are slower to reform (Pollitt and Bouckaert, 2011, p. 63).

In this section we have characterized societies as a whole and noted that these characterizations are not static. Organizations are embedded in their society, and their functioning and culture is generally in sync with that of their society. However, there are distinct differences between organizational cultures.

Organizational Culture

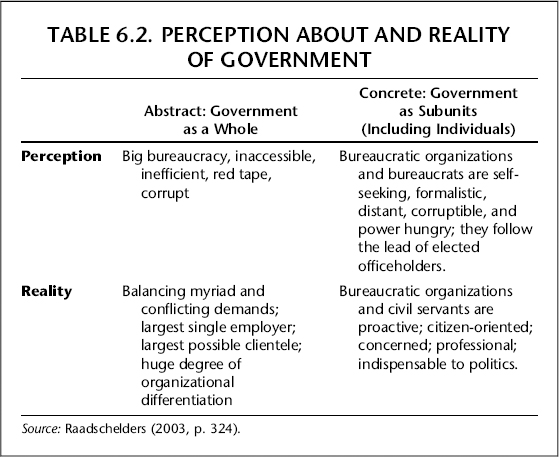

In terms of structure, most sizeable and large-scale organizations are bureaucracies; in terms of their functioning, they are very different. For instance, most organizations where employees are expected to be in uniform during office hours (military, police, firefighters) are much more hierarchical than nonuniformed organizations such as a social work unit, a school, or the Department of Home Affairs. Obviously, every bureaucratic organization operates as a hierarchy, but the extent to which that hierarchy is invoked varies. The differences between how organizations function notwithstanding, the stereotype of bureaucracy has prevailed (see Table 6.2). In Section 2 we suggested that the stereotype regards a bureaucracy that no longer exists: a bureaucracy that exploits subjects. In Western democracies bureaucracy generally is a service provider, hence the contrast between perception as visible in the stereotype and the reality of government organizations. In Chapter 5 we have seen how fragmented government is and that it is expected to meet multiple and often conflicting demands. Historically, bureaucracy was populated by “mandarins” and “slaves” who only served the political regime in power. Contemporary bureaucracy is highly fragmented, providing a large range of goods and services; is populated by civil servants who are highly educated; is generally citizen-oriented; and is indispensable to political officeholders.

An excellent example of how the functioning of bureaucracy varies with national culture is provided by Hofstede and others (2010, p. 243–245). They describe how an American professor, O.J. Stevens, teaching at the INSEAD business school in Fontainebleau, France, assigned a case study about a conflict between two department heads. In the exam the students were to outline how this conflict could be resolved. The class had students from various countries, but those from England, France, and Germany were in the majority. Stevens noted how the students came up with very different answers. The French generally felt that the two parties involved should take their problem to their immediate superior who would then settle the matter and thus provide guidance for how comparable problems in the future should be dealt with. In Stevens's interpretation, the French regarded bureaucracy as a “pyramid of people” with the CEO on top and each level in clearly defined relation to the other. German students perceived the conflict as evidence of lack of structure, and they advised establishing clear procedures for settling daily problems. In Stevens's words, Germans regarded bureaucracy as a “well-oiled machine.” Finally, the English defined the conflict as one where the situation, not the hierarchy or the rules, ought to determine the course of action. In Stevens's parlance, the English perceive an organization as a “village market.”

Hofstede and his coauthors linked this to the dimensions of organizational culture and to the University of Aston studies on how different organizations are structured (Hofstede and others, 2010, p. 305). With regard to the latter, the Aston researchers found that organizations vary in how authority is concentrated and how their activities are structured. The French students have grown up in a society with large power distance and strong uncertainty avoidance, hence why they advocated actions that further concentrated authority and structured activities. Growing up in a society with small power distance but strong uncertainty avoidance, German students favored structuring activities without concentrating authority. English students have been raised in a culture with small power distance and weak uncertainty avoidance, and so they supported neither further concentration of authority nor further structuring of activities.

Clearly, a pyramid of people relates to organizations with substantial power difference, because it is through the hierarchical structure that conflict is resolved. The village market organization has much smaller power distance; it is not the hierarchy but the people themselves who matter. And in machine-type bureaucracies a tendency toward fairly high uncertainty avoidance exists (Hofstede and others, 2010). Expanding these metaphors, in discussions with Asian colleagues, Hofstede identified an organizational type where the organization is regarded as an extended family, where the manager or owner is like a father or grandfather who is the ultimate authority and the employees are often highly loyal to the organization and stay for a long time (Hofstede and others, 2010, pp. 243–246). What the identification of the extended-family metaphor alludes to is the fact that many theories about and conceptions of government have a fairly strong Western bias. Itis true, and we have touched upon this in Chapters 2 to 5, that Western governments have exported a range of administrative traditions and theories across the globe through colonization and through development aid. Some people argued that this would ultimately result in a homogenization of administrative practices and ideas. Others have pointed out that this is too simplistic a conclusion. While there are bureaucracies everywhere, they do operate in different societal contexts and are thus different in how they function. Furthermore, efforts to introduce Western-style reforms in developing countries generally have not paid close attention to the degree to which the indigenous societal context and institutional traditions will support such foreign-based reforms.

There is one element of organizational culture where governments across the globe are similar, and that concerns the visual appearance of government organization. We already noted that governments and their bureaucracies are imaged in various arts such as poetry and novels, but also in paintings, architecture, and so forth (Heyen, 1994). The scholar who studied how government is visualized in architecture is Charles Goodsell in his research on the appearance and layout of American statehouses, city council chambers, and bureaucratic buildings. His descriptions and findings are relevant to any other country.

In his study of the statehouse, he noted how they are often set in parklike grounds emphasizing the relatively open, accessible nature of American state government. The state capitol articulates authority, and its most visible feature is the dome that exhibits three levels of meaning:

- low or instrumental meaning: It draws attention from afar;

- medium or status meaning: It identifies as state capitol; and

- its high or cosmological meaning: It resembles a giant head of authority (Goodsell, 2001, p. 25; see also Rapoport, 1990).

The front of the statehouse is frequently raised above the ground and is reached by steps, providing a space from which to look at the world below. The steps are often surrounded by podium arms, reminiscent of the arms of a sphinx and suggesting energy. In the rotunda, visitors may see a chandelier hanging from the ceiling, reflecting an ancient idea about sacred space: the egg of creation floating in the world. Statehouses are built with stone, and that is remarkable since many structures in the United States are constructed with less durable materials such as a wood for the frame of a building. This means that government is here to stay. Next, the interior of the statehouse testifies to the fact that it is a building where decisions are made that affect us all, and this is further underlined by displays of the state seal, a state's founding document, and the mace as ancient and traditional symbol of authority.

Not only do statehouses exude authority, power, and prestige, they also show evidence of important moments in a state's history through murals, paintings, and sculptures of crucial events and renowned citizens, politicians, and legislative and executive officeholders. Another element that expresses government culture is the floor plan of a statehouse. Goodsell's book shows how in bicameral legislatures both houses are situated on the same floor and occupy roughly the same amount of space. Legislative chambers are often quite compact with the legislators seated at the same level, stressing that its members operate as a collegial body rather than as individuals. While the judiciary in all states (and in many countries) operates as a collegial body, the members of the bench are often seated on a raised platform, which emphasizes their authority. The nature of the relation between legislature and executive is also spatially expressed. Until the 1920s the governor's office was usually situated in the floor below that of the legislature, suggesting subordination of the former to the latter. In the 1920s and 1930s the governor's and lieutenant governor's offices in several states were moved to the same floor as that of the legislature, suggesting equality of power.

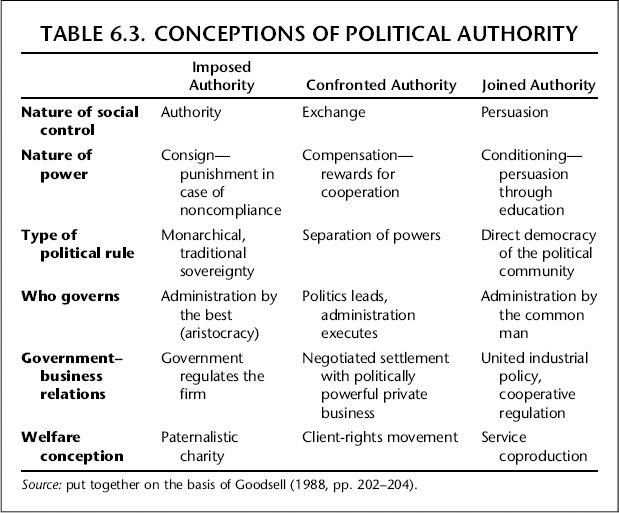

Goodsell also studied how political authority is imaged at local government level, focusing on city council chambers. He argued that type of authority is expressed in spatial arrangements and distinguished three types: imposed, confronted, and joined authority (see Table 6.3).

In the traditional city council chamber, the council members face the presiding officer (mayor) who is seated on an elevated bench. There is limited seating for the public, and the room expresses authority through elaborate entrances, large windows, and private doors for the council members. This arrangement expresses imposed authority where superiors (council members) exercise power over inferiors (citizens). This is a government run by the best, those who are called to govern by virtue of birth, and is a situation found in most of history. The second type of council chamber is related to confronted authority where the power of superiors is more balanced with that of the inferiors. There is much more space for citizens, and all council members face the public as a collegial body. Nowadays, council chambers are representative of joined authority, the third type, which conveys a sense of power sharing and a more subtle assertion of power. Additionally, the seating space for interested citizens is larger than in the other two types (Goodsell, 1988).

Bureaucracy also has its physical expressions, as Goodsell showed in an article analyzing the buildings of state agencies. He distinguished between three appropriate and three inappropriate types of public buildings. Of the three appropriate types, the best known is that of the traditional temple, often with a neoclassical and columned portico. It clearly evokes being a “public” building, with a clear entrance, and instilling a sense of pride (Goodsell, 1997, pp. 408–410). The local curiosity is also clearly a governmental building, but its architecture visibly displays a connection to the local region or community. It is a building that can be regarded as “ours,” just as the traditional temple, but then showing more individuality and character. The postmodern delight is even more individual. The early seventeenth-century English author and diplomat Sir Henry Wotton suggested that architecture should display commodity, firmness, and delight (as referenced in Goodsell, 1997, p. 414). This type of public building then responds to color, light, convenience, spontaneity, and playfulness. These types are labeled appropriate because they invite people and thus underline the accessibility of democracy (see also Goodsell, 1988, pp. 10–13).

Inappropriate buildings are not inviting. The bureaucratic box looks just like any office building, public or private, with glass, steel, and concrete. The image is one of a blocklike mass, undifferentiated from other buildings and exuding a sterile impersonality. The governmental fortress comes across as massive and discourages access. Finally, the consumer city is a public building where public spaces are mixed with other spaces such as shops, restaurants, convention centers, and so forth. These are complex buildings, with multiple entrances, small “cities” with freely moving residents of employees and citizens alike. They display no clear statement of “publicness.” The reader will find examples of these architectural images of public organizations anywhere, but briefly describing them is not the same as looking at the photographs in Goodsell's publications.

Bureaucratic organizations operate within a societal culture and express themselves architecturally in quite similar ways, but how they function varies. This variation in functioning is partly a consequence of specific tasks (i.e., uniformed services versus nonuniformed services), but also partly of differences in how individuals are perceived.

Perceptions of Public Individuals

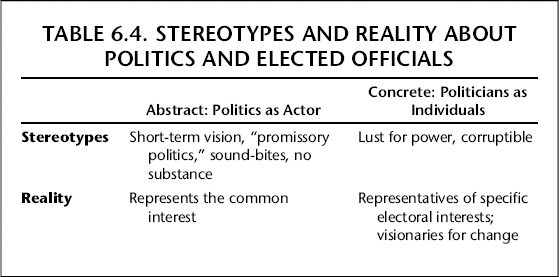

In the public sector three categories of individuals can be distinguished: the political officeholder, the civil servant, and the citizen. How individuals working in public organizations are perceived varies with societal culture. Again, we have to consider stereotypes. In the previous section we opened with stereotypes about bureaucratic organizations and civil servants. In this section we consider these civil servants again, but now in comparison to stereotypes about political officeholders and citizens.

Political officeholders do not fare very well in public perception; the reality is more often than not superseded by the stereotype (see Table 6.4). The extent to which this is the case varies, but stereotypes about political officeholders in the United States may appear to be closer to reality (consider: promissory politics; short-term focus) than in, for instance, the Germanic and Nordic countries, France, and Israel. In many developing countries it may be that reality is comparable to what can be regarded as stereotypical in Western countries.

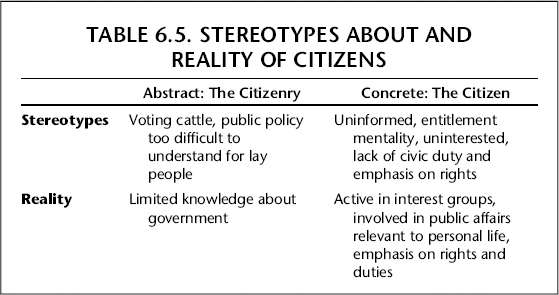

Political officeholders and civil servants cannot but have stereotypical images of citizens, but here the difference between stereotype and reality does not appear so large (see Table 6.5).

Given the subject of this chapter we will focus on stereotypes of civil servants, and one of the oldest is that which was published in a New York newspaper in October 18, 1787:

In so extensive a republic, the great officers of government would soon become above the control of the people, and abuse their power to the purpose of aggrandizing themselves, and oppressing them. (Ketcham, 1986, p. 279)

This quote by “Brutus” in the Anti-Federalist Papers clearly describes the “mandarin-bureaucrat.” At the time that this characterization of bureaucrats was printed, it was fitting. People knew that bureaucrats served those in power. However, just as the stereotype of bureaucracy has lingered, so has the stereotype of bureaucrats. Anthony Downs (1966) suggested that bureaucracies grow because their employees want to increase their power, prestige, income, and security. He was not very consistent since he also wrote in the same book, “The major causes of growth, decline, and other large-scale changes in bureaus are exogenous factors in their environment, rather than any purely internal developments.” (1966, note 50, p. 263) Nonetheless, William Niskanen pursued Downs's initial stereotype and suggested that bureaucrats merely seek to maximize personal utility by acquiring bigger budgets and more perks (1971, 1973). We believe that this is a human condition rather than something specific for bureaucrats, but we also know that bureaucrats are more frugal than what the stereotype suggests (see Dunleavy, 1991).

Many scholars have attempted to go beyond this stereotyping of civil servants as being of one homogenous type, and we will mention two examples. Downs distinguished between five types of bureaucratic personalities (1966, pp. 92–111). The climber is ambitious and on a fast career track. The conserver desires to maintain security and does not take risks. Zealots have narrow interests and usually are deficient general administrators. Advocates have substantial responsibilities and a significant overview of policies. Finally, statesmen are loyal to government and society as a whole. Hummel notes that the climbers, conservers, and zealots are the most bureaucratic (1977, p. 131).

Based on research in Israeli government, David Nachmias and David Rosenbloom (1978, pp. 31–32) describe four types of civil servants. The politicos are convinced that it is important to have political connections in order to acquire bureaucratic positions, and they are not very interested in the common good. Service bureaucrats take their cue from the public at large and seek ways for bureaucracy to improve how it allocates tasks to individual civil servants. The job bureaucrat is focused on the internal demands of modern government organizations. Finally, the statesman is truly oriented toward society and believes in achievement, education, and talent rather than in political and personal connections. Nachmias and Rosenbloom also categorized citizens according to their perception of bureaucrats. Bureauphiles expect to be treated as equals before the law, consider government to be fairly uncomplicated, and believe that bureaucracy is generally intelligent and fair. Bureautolerants come in two kinds: Some believe government is complicated, others do not. Some expect to be treated as equals, others do not. Bureautolerants often have a moderately positive perspective about government structure and its processes. Finally, the bureautics believe that they will not receive equal treatment and that government is infinitely complex and impenetrable. They are, in fact, repelled by bureaucracy.

Civil servants are the embodiment of bureaucratic organization. No one has “seen” a bureaucratic organization other than in symbols expressed through, for instance, architecture (see the previous section). What citizens across the globe regard as bureaucratic is very much influenced by the experiences they have with individual civil servants as well as by the stereotypical image that was handed down by the past and continues to survive despite the fact that contemporary bureaucracy is very different from its historical predecessor. It is time that people reconsider the stereotypes of old times and wonder whether government today is one that none would want to do without.

Sucking Water from Straws or Opening the Tap in the Kitchen

In the 1980 movie The Gods Must be Crazy we can see a member of a !Kung band in the Kalahari Desert sucking up water through a reed that he stuck into the sand. For most of our history, and certainly until some 12,000 years ago, people simply took from the land whatever they needed for immediate survival. And most of what they took from their environment, they shared (except, of course, the water sucked up through the reed; that is a truly individual good). Today, we still share what we take from our environments, but when we do, we do so because we are forced to share. What forces people to share scarce resources are governments and their bureaucracies. We can open the tap in the kitchen and expect drinkable water. This is not so everywhere in the world, but it is certainly a global desire. In the modern world where many people live in urban environments, government and their bureaucracies are indispensable because people no longer know all of their neighbors. In today's imagined communities, governments' “scaffold of thought”—that is, the law—and their myriad bureaucratic organizations are a necessity. Bureaucracy is no longer only the handmaiden of those in power, at least not when we believe in the democratic theory that the people as a whole are ultimately sovereign. It is possible, and even vital, to believe in that democratic theory, for in a cynical mood people might succumb to the idea that power always coagulates into the hands of a power elite. But then, citizens know that bureaucracy is larger than politics; that political officeholders come and go, at the pleasure of the people; and that civil servants (who are citizens themselves) will be around, no matter what, to help and protect the people.

Today, bureaucratic organizations are populated by people we know; they are educated, they are professional, and their interest is that of the public and not only of those who were elected into office. Bureaucracy in history was the instrument, a predator, in the hands of a ruler and a ruling class; today it is an instrument still, but then in the hands of mostly competent people with a calling for public service. Since the American and French Revolutions people know that it is possible to overthrow an unresponsive government. There is no country today that does not have a bureaucratic set of organizations. Bureaucracy is here to stay; Weber was right about that. In some countries it is well established and generally reliable; in many countries it is established but not (yet) reliable. We believe that democratization and bureaucratization are processes that cannot be reversed, save major natural disasters (such as what happened in the movie Waterworld with Kevin Costner in the lead role). In fact, democratization was possible because of bureaucratization, and that is even the case in the one country where democracy allegedly preceded bureaucracy (the United States).

We will never know whether Erik Satie would have written a different score had he been born a century later. He was Max Weber's contemporary, born two years later, dying five years later. His image of bureaucracy was not unlike that of Weber. They both imagined bureaucracy in its worst possible manifestation. They both were children of their own time, seeing but lacking the advantage of hindsight. And how could we blame them for casting what they thought, in their own time, to be true? In this chapter we described how bureaucracy has been perceived and how it has been defined. We have seen how bureaucracy in the past was very different from its counterpart in the present, and that this is mainly because it is no longer an instrument in the hands of the few, and that is what Weber captured in his ideal typical definition. In the next chapter we shall see how bureaucracies in the present manage their day-to-day affairs.

1 Van Braam, 1986; Raadschelders and Rutgers, 1996, 92.