CHAPTER FOUR

STATE MAKING, NATION BUILDING, AND CITIZENSHIP

National or territorial states have become an almost universal phenomenon. As we saw in the previous chapter, the entire globe is carved up in territorial states that are generally smaller than empires and larger than city-states (of which there are not many left). But while states may have structured their territories in comparable ways (see previous chapters), they are very different in how they function, and this becomes especially apparent in Chapters 9 to 12 of this book. Meanwhile, it is actually possible to “see” differences between states even when only visible as “lines in the sand.” In their recent study on the influence of the interplay between political and economic institutions upon nations (we would say: nations and states), Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson described the contrast between Nogales, Arizona, and Nogales, Sonora. The description (2012, p. 7) and the first two photographs in the middle of the book provide a startling contrast. What is one community of people, Nogales, with many sharing ties of kinship, is divided by the Mexican-American border. On the south side of the border poverty is visible in housing and infrastructure; on the north side people are clearly better off. Why? The authors theorize that in the United States people live and work in a society built upon inclusive political and economic institutions; that is, people can participate in the public realm and can pursue their own entrepreneurial interests. In less inclusive (that is, exclusive) societies, political and economic institutions are merely used by the elites to extract resources from the population in support of what they deem to be a lifestyle appropriate to their status (we will discuss later that this analysis is too simple and does not capture the extent to which certain categories of people are excluded from political and economic participation in inclusive communities). Indeed, territory as circumscribed by borders and jurisdictions makes a difference. It even can make a difference within a country, especially when certain (poorer) areas at the local level can be excised from a municipality, as is possible in the United States (Burns, 1994). As far as we know, in other Western countries local governments cannot remove the poorer areas from their jurisdiction.

The concept of state is often defined in terms of population or people, territory or land, with a clear monopoly over the use of violence. This includes both the maintenance of public order and safety (internal) and the defense of the territory against foreign aggressors (external). These internal and external elements hark back to understanding the state as a political system whose sovereignty is somewhat protected by international law since the 1648 Peace of Westphalia: Today one can generally neither invade the territory of nor meddle in the internal affairs of a recognized sovereign state. This view or definition of the state is rather top-down by nature, placing government at its center. It is rather different from the Hobbesian philosophy of the seventeenth century highlighting a social contract, which builds a bidirectional relationship between rulers and citizens. This approach allocates enough power in the hands of the people to prevent misuse of government authority. This view to perceiving the state implies that it is the only societal actor left that binds people together, and then specifically in their role as citizens. It is in this role that people are truly equal before and in the eyes of the law. In this view the state and its government are more situated amidst the citizenry it serves.

Traditionally, state making and nation building are topics studied in political science, but there is every reason to believe that understanding the origins, the development, and the current role and position of the state are important to understanding contemporary government (see, for instance, Vigoda-Gadot, 2009). In other words, the study of public administration needs to prepare its (future) career civil servants, military personnel, and political officeholders as well as citizens at large for the political and societal context within which government officials operate. In this chapter we will start with defining state and nation, with special attention paid to different conceptions of state and how these may influence our perception of government. We then proceed to outline the processes of political and administrative centralization, because these have occurred everywhere even if to varying degrees of centralization (Section 2). In this section we will also discuss such concepts as weak, strong, and failed states that are quite popular but not so useful for describing reality today. One important aspect of state making is that it is a process where state and government slowly, sometimes faster, but always surely differentiate themselves from other societal organizations. Of all society's overarching institutions, it is state and organized religion (church, synagogue, mosque, temple, and so forth) that have been very much intertwined for most of history. High-ranked state officials often held high positions in organized religion (for instance, Egypt's pharaohs, the English monarch since Henry VIII). Therefore, separate attention will be given to the relation between organized religion and state, the rationale for its separation over time (Section 3), and why this separation has been important for the emergence of the nation-state.

State making is related to nation building (Section 4), which is the process of forging together a population on the basis of shared history, culture, language, and so forth, even when most people cannot and never will know one another on a personal basis (see Chapter 2). In some cases nation building preceded state making (as in the cases of, for instance, Germany, Israel, and the United States), while in others it followed (as in the cases of, for instance, England, France, and the Netherlands). There is no real pattern other than that state and nation become more closely intertwined at some point in any country's history. Even in the case that a state was artificially created and the boundaries of which crossed and separated tribal areas, as has been the case in large parts of Africa and Latin America, there may be a sense of being a Nigerian or a Brazilian next to identifying with a specific tribe. Whether preceded or followed by state making, nation building in the past 150 years or so occurs in the context of defining citizenship. Being a citizen, as noted previously, is the only role that all people have in common in modern society. Losing one's citizenship means detachment from a state and in many cases also from territory and people. The fact that we identify as citizens and, perhaps more important, that the expression of citizenship varies with level of government requires a comparative discussion of the nature of today's multilayered citizenship (Section 5), and that provides a nice stepping-stone into the discussion of multilevel government in Chapter 5.

Defining State and Nation

People always try to define the circumstances they are in and dominate their existence. They seldom consider the origins of the terms state and nation, nor the reality that such terms circumscribe in the present. As individuals, people will always respond to present challenges in a manner that befits their own era, customs, examples, and elders. In the present time, actually since the late eighteenth century, people have been allowed—in some places sooner than others—to respond to life's circumstances as citizens. It is in that role, as citizens, that people can understand the contingencies confronting them when considering the context within which they live, because that context transcends the experiences of the nuclear family, the extended family, or even the band, tribe, or nation they grew up in. Part of that larger, somewhat, or much more alien, context is that of the state. Another part of that, somewhat less alien, context is that of band, tribe, or nation. In this section we shall first explore the concept of state and then proceed to discuss what is perceived as nation.

In the world today people are members, willingly or not, of a state. There are no people on this earth who are not part, as citizens, of a state (unless citizenship has been stripped because of crime). Today, every child born is born in a state, and her or his name is registered within days or weeks of birth. And that child will be, once registered, a citizen of that state until death. Exceptions only include the change of citizenship from one state to another, or dual citizenship. And even that is not really an exception. We may be born “free” but are soon citizens, yet we surely will die being a citizen somewhere. In today's world, as much as people may in a sociological sense identify with a specific region or tribe (or whatever), they are part of a state. And this is no clearer than when people need to get a passport in order to travel abroad to other states. In a legal sense all people are citizens of a state. Hence, quite obviously, the terms citizens, citizenship, states, and nations are strongly bound together and curry profound meanings and implications, especially from a global and comparative viewpoint.

The current understanding of the concept of state dates back to the late Middle Ages, when it was regarded as a geographically circumscribed area ruled by divine right and/or military might by a strong individual or family. In the course of the seventeenth century, the state concept was no longer tied to a specific individual. It merely was a territory in whose internal affairs other such clearly demarcated territories could not and should not interfere. This conception of state found its first international (Western European) agreement in the Peace of Westphalia mentioned previously and was solidified in Weber's formal definition of state as an entity characterized by:

- control over a well-defined, usually continuous territory;

- a relatively centralized administration;

- differentiation from other societal associations through the development of permanent and society-overarching institutions; and

- a monopoly over the use of coercion, assuring that it could pass justice in the name of all (Tilly, 1975, p. 27; Dyson, 1980).

This is a twentieth century understanding of state, that is, a political entity defined in terms that are (1) territorial, (2) top-down and centralized, (3) autonomous, and (4) sovereign, and was as such confirmed at the Montevideo Conference of Rights and Duties of States (1933), the participant countries of which were all located in the Western hemisphere, but its notion of an internationally recognized sovereignty was adopted across the globe. It is important to recognize that this is a truly twentieth century definition of state, for it assumes that military power is subject to political power, and that is a situation most unusual in history (Mann, 1986a, p. 11; Mosca, 1972).

Now, in the second decade of the twenty-first century, this definition of state dominates juridical understanding and so international law. After all, a state is not expected to invade another without expecting others, such as allies, to come to the latter's need. A state's internal affairs should not be tampered with unless under circumstances of severe duress (however defined: genocide, economic crisis, medical crisis such as Auto Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS), and so forth). We emphasize this juridical or legal definition of state because it dominated twentieth century thought about state. The authors of this volume grew up unaware of any other than this legal definition of state. However, growing up, the authors of this volume also encountered doubts about this Weberian definition of state. These doubts were not inspired by pristine or rather philosophical thoughts about state (as in contrasting to nation, or contrasting to the earlier medieval notion of “status in life”); instead they were inspired by a more sociological sense of state. In a legal sense it is quite clear what constitutes a state. In a sociological and psychological sense the meaning of state varies with country and with perspective, attitude, and behavior.

Where legal perspectives tend to present cases in terms of black or white, that is, a territory is a state or not, a sociological or psychological perspective (troubling to some) presents reality in terms of shades of grey. Just considering and scanning literature on state in the twentieth century we find that a legal or juridical definition of it dominates until the 1960s. It is then that many new states enter the world stage and that is when, as John Nettl noted, the link between state and nation—so taken for granted—was snapped (1968, p. 560). In the wake of decolonization, and then with the dissolution of the Soviet Union, it became clear that some newly independent countries were successful in meeting the domestic and international expectations that came with being a state while others were not. Hence, people and scholars (in whichever order) have—slowly—warmed up to the idea that the state as a juridical concept is no longer sufficient when characterizing reality.

Scholars do not often distinguish a juridical from a sociological or psychological definition and understanding of state. The juridical one is that which is given earlier; it is Weberian, and part of international law. The sociopsychological perspective is one that does not really define a state but, rather, one that designates it, positions it, in the past, at the present, and even an (undetermined) future within the society it circumscribes. Why is defining and/or understanding that role and position of the state so important in the effort of understanding government's role and position in society today? The answer is quite simple. State and government today are hand-in-glove to a degree they never were before. State was a territorial circumscription—that is, property—of an individual ruler or elite, until it became an abstraction—that is, divorced from a living being—and became the entity of a people in one country with an elected representative body. The state today is sovereign, irrespective of who is divined, inherited, or elected as its ruler. Clearly, in terms of international law the 1648 agreement still reigns supreme, and there is then only one type of state. In a socio-psychological perspective, however, there are different types of states and different types of citizens who populate them.

The most well-known distinction is that between strong and weak states. For example, Vigoda-Gadot (2009, p. 8) suggests that if one were asked to divide the world into strong and weak nations, there is little doubt what the resulting list would be. Most probably, a majority of the respondents would put the developed world of wealthy, Western states and some of the richest Asian countries in the column of strong nations, while the poorest countries in the developing world would be defined as weak nations. There would probably be little debate about the political, economic, and military power of each state. Still, one wonders what makes some nations strong, regardless of their military power, natural resources, capital, and geopolitical situation, and other nations weak, even when they hold several assets of the kind mentioned previously. It is puzzling that states with few resources are viewed both by public opinion and according to objective measures as “stronger” or as “weaker.” What is the secret of building strong states, and how can we penetrate this enigma to help governments build stronger nations? In a more conventional view a strong state is one that provides security to its people and protects them from foreign aggression, for which there is the military; as well as from internal dangers, for which there are, for instance, police and fire departments. It is also one where government is accepted as the adjudicator in disputes; where citizens can participate in the political process without fear; where people can expect provisions for medical and health care, for education, and for navigable physical infrastructures (roads, railways, harbors); where there is a reliable banking and insurance system; where people can pursue their own dreams; and where civil society is promoted as an important good (Rotberg, 2003, p. 3). Weak states perform less well on several or many of these features of a strong state. They may be weak because of environmental constraints, because of economic problems (e.g., lack of natural resources), or because there are significant social cleavages (along, for instance, ethnic, religious, or linguistic lines). Weak states also often experience higher or rising crime rates, and they are often ruled by despots (Rotberg, 2003, p. 4). When a weak state performs poorly on most features it may be on its way to become a failing state and even a failed state (Chomsky, 2006) that can no longer control its borders and where most institutions disintegrate save the executive arm of government that is controlled by a small power elite. The most extreme type of failed state is the collapsed state, which “exhibits a vacuum of authority . . . [that is] is a mere geographical expression, a black hole into which a failed polity has fallen.” (Rotberg, 2003, p. 9) These designations of states are not static. Countries have moved from being fairly strong to failing, or from being collapsed to simply weak (for examples see Rotberg, 2003; also Hanlon, 2011).

The designations of strong, weak, and failing states are usually applied to countries at a specific moment in time. For instance, Richard Stillman defined periods in the history of his country in terms of different designations. What makes his analysis interesting is that it shows how much a specific perspective upon the state actually has clear consequences for the nature of its administration.

The no-state (or negative state, or laissez-faire state) is one with a limited government, mainly responsible for traditional public services (defense, police, justice, taxation). It is the kind of government advocated by the Jeffersonians in the late eighteenth century and by monetarists and public choice theorists since the 1970s. It is also a government with a very clear distinction between elected officeholders and career civil servants. The latter simply carry out the directives of the former. In its internal functioning it is a highly decentralized government (Stillman, 1999, 175–185, 226–227).

The bold-state or (positive state) is pretty much the opposite of the no-state, and is characterized by an expansive government providing a wide range of services. It is also a much more fragmented state with several public, nonprofit, and private actors taking action at national, regional, and local levels (Stillman, 1999, pp. 185–197). The prestate (or halfway-state) sits smack in the middle between the no-state and the bold-state, and its advocates are less definite about the role of the state (Stillman, 1999, pp. 197–205). Most important, they point to the existence of a so-called “unwritten constitution,” which Don Price describes as “. . . a reflection of the basic political philosophy of the people, of their traditional prejudices and attitudes, often incoherent and not explicitly formulated as important.” (Price, 1983, p. 9) This is considered as important as the formal institutional superstructure established by the Founding Fathers. This prestate or halfway-state is somewhat reminiscent of what Huntington labeled a Tudor polity, a political system where power is both horizontally and vertically dispersed across a variety of institutions and where, e.g., legislative and judicial functions are fused in some respects (e.g., consider the role of jurisprudence) (Huntington, 1973, pp. 173, 183, and 190). We will get back to this point later, about the United States being a Tudor polity. Finally, the prostate (or professional technocracy) is one where government is run by experts, the ultimate administrative state where expert elites in the career civil service know which decisions are best for society. It is, thus, the most antidemocratic of the four types (Stillman, 1999, pp. 205–213).

Earlier in his book Stillman discusses, as he calls it, the “peculiar ‘stateless’ origins of American Public Administration Theory” (Stillman, 1999, pp. 19–41). He finds, as so many authors before him (for instance, Nettl, 1968, p. 561), that at the time of its creation the United States embarked upon a unique experiment, designing a polity with a very small bureaucracy and with strong suspicion of anything that resembled “state,” understood as a top-down, highly centralized polity that acted irrespective of the desires of its population. The Founding Fathers wanted to create a state very different from that of the English, which simply imposed taxes upon the colonies without consultation. This notion of “statelessness” has been very pervasive and also affirmed in Nelson's superb 1982 article where he argued that “the establishment of democratic political institutions preceded the establishment of administrative ones.” (1982, p. 775) Indeed, in Europe, state and its bureaucracy had existed prior, and sometimes even centuries prior, to the creation of democratic political institutions through, for instance, the expansion of the franchise. While one can argue that England was the prime example of a stateless society (Nettl, 1968, p. 562) from which the United States adopted many features (for instance, the Tudor polity mentioned earlier), it is important to remember that the term “stateless” is sooner obfuscating than enlightening. After all, the territoriality that is captured in the state concept was reality throughout history. Were there truly “weak” states in the sense that they were strong enough to survive yet did so with only a skeleton bureaucracy? When clinging to Weber's definition of state, the American early state was weak in comparison to European states, but it has been strong from the beginning in terms of the extent to which American government was able to shape civil society. Novak unmasked the “weak” American state as a myth, pointing out the fact that state power is hidden; that is, widely distributed across a multitude of institutions at all levels of government (Novak, 2008). Classic state theory assumes strong state power at the center; it does not consider the possibility of political power as being dispersed, and not only limited to public organizations but including nonprofit and private organizations as actively involved in governance.

To bolster his argument, Novak calls upon the distinction Michael Mann (Mann, 1986b, p. 115) made between two types of state power: despotic and infrastructural power. Despotic power is exercised by a small power elite that can do whatever it likes and whose actions go unchecked by other societal institutions. In democracies despotic power is weak, while infrastructural power—the capacity of the state to shape civil society and successfully pursue policies throughout the territory—is strong (hence, also a strong bureaucracy). In feudal societies both despotic and infrastructural power are low (for example, medieval Europe), while both are high in authoritarian polities (Nazi Germany, former Soviet Union, People's Republic of North Korea). In imperial (or patrimonial) systems despotic power is high, but the penetration of society is low (which holds for most empires to varying degrees, such as, for instance, ancient China). In modern democracies, clearly, the possibility of despotic power is severely curbed but the ability of the state to shape its society is high. By all accounts, once the United States had shed the Confederacy, it became a strong state given its growing capacity to penetrate society. This type of strong state survives because the political and economic institutions allow full participation and development of its citizenry; it is as Acemoglu and Robinson named it: an inclusive state. We agree with Michael Mann that true stateless societies were primitive (1986b, p. 119); that is, they existed before the creation of formal political institutions. In other words, the concept of “weak state” is not really helpful in describing the current situation in which any state finds itself.

When using designations such as strong, weak, or failing states, etc., we should therefore adopt a sociopsychological perspective that really asks: in whose eyes and by what criteria? Clearly the Western conception of state dominates when the political, social, economic, and cultural situation in non-Western states is evaluated. And, equally clear, the situation in non-Western countries has been evaluated in terms irrelevant to it. Pierre Englebert and Denis Tull convincingly argued with regard to Africa that assessments of the plight of non-Western countries are flawed because they assume that Western state institutions can be successfully transferred, that Western donors and African leaders are cooperating, and that donors can marshal the resources for long-term state reconstruction (2008, pp. 110–111).

Meanwhile, the juridical notion of state has come under fire in the Western world for at least two reasons. First, the concept of governance, as it emerged from the 1980s on, emphasizes that the state is not the only actor responsible for governing of society. There are, in fact, multiple actors in the nonprofit and private spheres that contribute significantly to the steering of society. Indeed, nonstate actors are increasingly involved in the delivery of social services, a trend captured in the concept of the hollow state (Milward and Provan, 2000). Second, while the state in the international arena is formally still the only actor that can make binding decisions for its population as a whole, in practice it cannot but accept the increasing involvement of subnational and supranational actors in defining domestic and global policies. This is perhaps most clear in the European Union, but has really happened everywhere.

Is the strong or active state a thing of the past? Perhaps this question cannot be answered unless we can show that the strong or active state, defined as one where government provides the bulk of services, actually existed. We suggest that a democratic strong or active state never really existed, in the sense that states and their governments have always shared power to a smaller or larger degree with other social institutions (most prominently with organized religion, but one could add in the past 170 years labor unions and voluntary associations). Sharing power with citizens in a democratic state is also known as the bureaucracy-democracy paradox and is widely discussed in extensive literature (for instance, Gawthrop, 1998; Goodsell, 1983; Vigoda-Gadot, 2009). If anything, the democratic state has been an enabling state where government allows to a smaller or larger degree service provision by other actors (for instance, voluntary, private, semipublic, regional/local government, and arms-length agencies) (see for discussion Page and Wright, 2007, pp. 3–5). The state, however, not only enables other actors to partake in the governance of society; it most certainly supervises the activities of other actors and provides a legal framework within which government, nonprofit, and private actors can and have to act. Placing the responsibility for the delivery of public services in the hands of other actors increases the need for accountability and centralized rulemaking, thus for an enabling framework state (Raadschelders and others, 2007, p. 310). The institutional framework within which governance manifests itself is in a legal sense still decided by those who have been designated to design the state; that is, those whom the people have elected into legislative office. So, the enabling framework state is also an ensuring state (Schuppert, 2003) that guarantees the delivery of public or collective services even when private actors are responsible for providing them (through contracting out, public-private partnerships, or collaborative governance).

States and their governments are regarded as legitimate when the population accepts their actions. While some policies target specific groups within a given population, there are many policies that concern the people as a whole. No matter how differentiated in an ethnic, linguistic, and cultural sense, a population is frequently treated as if it is one nation, a concept that initially denoted a homogeneous community of people with a shared language and history and close kinship ties. The concept of nation-state, then, denotes a close relation between a people and its territory; that is, assumes that at least 95 percent of its population shares a common ancestry. There have been, however, very few such nation-states in the history of humankind. City-states may have been fairly homogeneous, but empires certainly were not. One example of a true contemporary nation-state is that of Iceland, where the large majority of the population can actually trace its ancestry back to the tenth century of the Common Era. Almost all other states in the world are at best territorial states because their populations consist of people from various backgrounds. Especially in the Western world, population diversity has been increasing since the 1960s with the immigration of political and, more important in terms of numbers, economic refugees (Arnold, 2010). In the non-Western world, populations are as diverse, but then often as a consequence of having been “thrown” together by colonial powers carving up territories in foreign lands without knowing anything about existing or previously existing indigenous tribal boundaries or polities (Davidson, 1992) and unaware of its urban past (Davidson, 1987). The story of state making is in the case of Europe indigenous; in the case of much of the rest of the world, at first sight it appears simply imposed.

State Making: Models and Explanations

It is not so long ago that the world was littered with thousands of polities in various stages of institutionalization but always with some sense of boundaries. In the more “primitive” societies these boundaries may have been somewhat fluid, but they generally were respected and mainly defined by kinship ties (Diamond, 2012). In other words, even a band can be considered a polity. Some such “primitive” societies still exist today (for instance, the !Kung in the Kalahari Desert). However, in many parts of the world and as people increasingly became sedentary, more complex polities emerged: chiefdoms, city-states, federations, kingdoms, empires, and theocracies. The territorial state (we prefer this term instead of nation-state) is the dominating polity in today's world and is of fairly recent origin and has its roots in Europe. Let us first look at the numbers. Charles Tilly describes how in the year 1200 CE the Italian peninsula alone was carved in 200 to 300 city-states; the entirety of Europe was fragmented into hundreds of principalities, bishoprics, city-states, counties, duchies, and so forth. Around 1490 there were about 500 would-be states, statelets, and statelike organizations (1990, pp. 40–42). Since then the number of states first declined until the early nineteenth century, only to increase from then on.

From the late Middle Ages the territorial states slowly but surely increased their authority upon the cities, especially in Poland, Russia, and Sweden (Pounds, 1990, p. 206). By the early nineteenth century there were some 25 territorial states in the world, most of which were in Europe, and several new states were being established during the independence movement (the first decolonization) in Latin America. In 1914 there were 55 territorial states; 59 in 1919; and 69 in 1950. Because of the second decolonization period, starting in Asia right after the Second World War and spreading to Africa within a decade, this jumped to 90 in 1960. In 2002 there were 192 territorial states (Rotberg, 2003, p. 2). The long trend has been one of diminishing types and numbers of polities, while the territory circumscribed by the territorial state has significantly increased (Chase-Dunn and Hall, 1997, p. 207). There are numerous explanations for why this happened, but it is not our intention to summarize scholarly debates, so here it is worthwhile to mention at least one explanation that is less common than other explanations. In a recent article Andreas Wimmer and Yuval Feinstein provided an overview of the literature concerning why the nation-state (as they call it) proliferated across the globe. While so far we assumed that this happened because of colonization, that is, one of the traditional explanations, they find that the nation-state spread across the globe because of contagion: nation-state development in one area spilled over to adjacent areas (2010, p. 770). It is thus that they conclude upon careful quantitative analyses of various factors that “the almost universal adoption of the nation-state form . . . emerges from local and regional processes that are not coordinated or causally produced by global social forces.” (Wimmer and Feinstein, 2010, p. 785) We find this conclusion all the more important in light of the argument we made in Chapter 2.

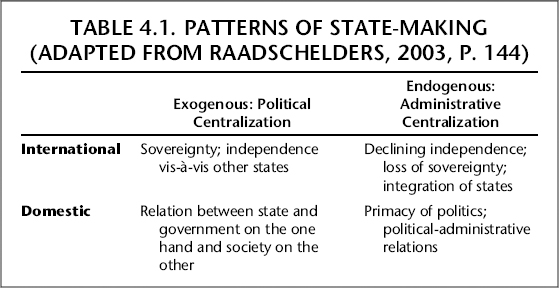

We can infer from the discussion in Section 2 that state making is a process that has international and domestic dimensions. State making is also a process with exogenous and endogenous dimensions (see Table 4.1).

Exogenous models of state making concern political centralization, the process whereby the political power within one territory is concentrated in the hands of one person and/or one body (such as governing institutions). Power in society is initially exogenous to government, and the process of concentrating that power into the hands and offices of actors clearly defined as governmental is slow but inescapable. Consider the case of medieval France. The king as overlord had little political power over the regional dukes. They had political power in their own right. Once the French kings succeeded in subordinating the regional political powers under their crown, we can say that political power has centralized. The international dimension is that the political institutions of the territory of that state are acknowledged as authoritative by peers. When political actors of a state are not regarded as authoritative, which is usually because of crimes against humanity or extreme despotism, then the international community may look for another set of actors. Domestically a state must be accepted as the only actor that can make binding decisions on behalf of all people living in its borders, and that includes expatriates (those working in the foreign service) as well as people with a foreign nationality (e.g., resident aliens, for instance, in the United States).

There are two types of exogenous models. The English-French pattern is characterized by early unification of the territory under one ruler whose authority is slowly expanded from one center outward. Political centralization is easier when the territory is well defined in terms of physical boundaries such as seas or mountain ranges. The German pattern is one of late unification, mainly because of great diversity of landscape and societies. The German lands had been ruled by hundreds of states since the Middle Ages, but because of conquest, marriage, and consolidation, there were about 300 left in 1800, loosely held together by the Holy Roman Empire. At the Vienna Conference in 1815 that empire was dissolved and replaced by a German Confederacy of 39 states. Fifty-six years later the German Empire was created out of 27 constituent territories. Earlier we saw that this pattern is also characteristic for Italy.

Endogenous models are focused on administrative centralization, the process through which all administrative activity is subjected to the political authority of one person or body. We call these models endogenous because administration in government is subjected to institutional and/or individual actors who are invested with political power. Thus, administration is internal to government. The core domestic feature of endogenous models is that of the primacy of politics over administration. The international dimension is somewhat awkward, in that increased intertwinement of states results in loss of independence and sovereignty to some degree. Also, even though political officeholders still are “on top,” in the international arena expert civil servants increasingly participate in policy and decision making. This is especially clear in the European Union.

As with the exogenous models, there are two types of endogenous models. In the English model state making proceeds on the basis of a unified yet decentralized structure that operates on the basis of a strong and cooperative local government. It also features a tradition of amateur government, which is a government that is run by gentlemen and does not require many experts. Given the fairly substantial autonomy of subnational jurisdictions, most of these amateurs are recruited from among the local or regional landed elites. This pattern is also found in the Dutch Republic up to the late eighteenth century. A tradition of amateur government in England actually lasted until the 1960s, given the Oxbridge background (history, philosophy, languages) that Whitehall civil servants were expected to have. We find a tradition of amateur government also in the United States up to the late nineteenth century. However, this characterization is somewhat stereotypical and depends too much on the contrast between the English and American experience on the one hand and the French and German experience on the other. English administrators were not that amateurish, and neither were their American brethren (Fischer and Lundgreen, 1975, p. 460; Cook, 2012). The German-French pattern is one with a unified and centralized administrative structure, a subordinate subnational government, and a class of civil servants trained in specific administrative skills. This model emerged in the second half of the seventeenth century, and the publication of the first handbooks of public administration and the creation of university chairs in public administration illustrate this development. In fact, public administration as a pursuit and study becomes more and more secular in orientation and clearly linked to the state. To understand how this came about we need a brief excursion into the separation of church and state.

The Separation of Organized Religion and the State: A Recent Phenomenon?

In 1983 the American anthropologist Edward Hall noted, “The novelist and the poet reflect the principal preoccupations of people and their times.” In that spirit we defer to Victor Hugo's Les Misérables. Victor Hugo's masterpiece became a TV movie in 1978 and a musical in 1985. A big-screen musical version was released in 2012. Obviously, the TV movie does not have all the detail of the book, but there is one scene where the meaning of the French Revolution is captured better than in the book. Toward the end, Jean Valjean and Inspector Javert meet again in the sewers in Paris. This time, Valjean holds a gun in his hand and Javert tells Valjean to shoot him. The latter responds that he cannot, remembering that once his life was bought for God. Valjean, of course, is thinking of the bishop who had given him shelter after his flight from the galleys, and from whom he had stolen some silver tableware and candleholders. Caught by the police, he was taken to the bishop's house to inquire whether, indeed, the bishop had given the silverware to Valjean. The bishop, looking intently at Valjean, confirmed the latter's story, noting that Valjean needed it more than himself. Javert is unaware of Valjean's motives and answers, “There is no God. There is only the Law. Good and evil do not exist outside the law.” A few hours later Javert commits suicide.

This dramatic exchange captures beautifully one of the main events in the aftermath of the French Revolution: the de iure separation of church and state relegating the church and spirituality to the private realm, while the state in its secular appearance occupies the public realm. It also underlines the extent to which the tables are turned: The state dominates the public realm, the church, no longer. Looking back, it is really amazing how much some people are in tune with their own time. Consider the following observation by Catherine the Great, czar of Russia, uttered somewhere in the later part of the eighteenth century: “Me, I shall be an autocrat: that is my trade; and The Good God will forgive me: that is His.” This remark would have been inconceivable, even only decades earlier. After all, monarchs ruled by divine right and were crowned by the church. The contrast between Charlemagne's coronation as emperor by the Pope in the year 800 and Napoleon crowning himself emperor in 1804 could not be starker.

To be sure, as much as we can say that the changes at the time of the Atlantic Revolutions provided the foundation for the modern role and position of government in society, there was—as De Tocqueville remarked— much continuity as well. With regard to the topic of church and state, their de iure separation was enshrined in the first constitutions, those of the United States in 1787, France in 1789, and the Batavian (Dutch) Republic in 1798, but really concluded a process that originated in the eleventh century whereby church and state de facto started to demarcate their own spheres of influence. With the advantage of hindsight and in light of history, this drifting apart was both unusual as well as fitting.

That organized religion and state started to drift apart in Europe was unusual because until then they were generally closely intertwined everywhere. In antiquity most, and perhaps even all, rulers played various roles: head of state, head of the army, high priest, high judge, and so forth. From late antiquity on, these roles differentiated, but rulers did govern by a mandate from the divine. The relation between religion and government at the time is perhaps described best by Pope Gelasius I (492–496 CE) in his Two Swords Theory: The church represented the spiritual-eternal world and was superior to the state that embodied the temporal-secular sphere of power. Almost 600 years later, in 1075, Pope Gregory VII invoked this theory to shore up his argument that the appointment of clergy was solely the prerogative of the Church of Rome and not of kings and princes. His papal decree started a conflict that lasted almost half a century and is known as the Investiture Struggle. It culminated in the 1122 Concordat of Worms that gave the church its coveted control over ecclesiastical appointments. However, from that time on, the state slowly and surely asserted itself in the secular realm, with the church learning that its clergy and flock were increasingly reluctant to side with papal supremacy. Indeed, the people increasingly identified with the state.

Today, state and church are clearly separated in most of the Western world, in much of Latin America, in most African and Asian countries as well as in Australia, and this is illustrated by the fact that most countries have no state religion. This is a recent phenomenon in terms of how widespread this has become across the globe. History is messy, though, and there never really is a clear path from one pattern to another. For example, back in sixth century Byzantium, emperor Justinian was head of state and of church, with the latter being subordinate to the former. And there are still countries with an official state religion, such as in most Islamic countries (except Indonesia); in Denmark, Iceland, and Norway; as well as a number of small (city-) states such as Vatican City and to a certain degree in England. And only in 2000 did Sweden declare the Lutheran Church to be the state religion no longer.

So the separation of church and state was unusual in the sense that hitherto powerful roles and positions in society were often combined in one person, but the separation was also fitting in the sense that territoriality and dominance hierarchies were the two major features of social life in many species, as Richard Dawkins pointed out in his 1976 The Selfish Gene. Indeed, human beings are in some respects not so different from other animals.

Territoriality is usually conceptualized in terms of geographical space, but it is clear in this presentation that it can also be defined in terms of authority. And this is not just about who has the right to appoint officeholders, but also about who controls public services. During the Middle Ages, the growing separation of church and state was mainly evident in appointments, and the growing dominance of the state was visible in its levying taxes over clergy. In the early sixteenth century, though, and in the wake of the Protestant Reformation, various services transferred from the church to the state. That is to say, the countries that turned Protestant had a tradition of strong local self-government that had not been disturbed by Roman occupation. It was there, generally, that services in the areas of education and health voluntarily changed hands, with local governments taking over responsibilities from the church. Especially education was an area where church and state interests clashed. In France and Russia it was not until the nineteenth century that church-controlled schools were seized by public authorities. In countries such as Denmark, England, and the Netherlands, governments set up a system of nondenominational and vocational schools. With regard to hospitals, during the Reformation in northern Europe they simply were seized as part of the effort to take church property. In countries such as Spain and Italy it was only in the nineteenth century that, under pressure, ownership transferred to the state. In France, legislation since the 1880s assured that hospitals provided care to all and not just to those who were of the right denomination. Protestants in Catholic hospitals faced constant pressure to convert, especially in the face of death; there were forced baptisms; Protestants could even be denied a minister tending to their spiritual needs; and it was rumored that care might be denied if one turned to a hospital of the “wrong” denomination (Azimi, 2002; Dhont, 2002).

While separated by law, in practice state-church relations tend to vary. In Catholic countries, state and church recognize common tasks as in Austria, Belgium, Italy, Portugal, and Spain. In several Catholic and Protestant countries governments support religious organizations, for instance, through the construction of buildings of worship. Examples are France, the Netherlands, and the UK. In mostly Protestant countries, a general religious tax is levied and each citizen can indicate to which denomination her/his money should go, as in Austria, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Norway, and Switzerland. Then there are countries where church and state are strictly separated, as in France. We remember the Islamic scarf controversy in France that drew worldwide attention in the mid-1990s. In the foreign press, the French have often been reviled for their strict adherence to the law of 1905 that served as the capstone legislation of all laws since the 1880s concerning the separation of church and state in all areas, health care and education included. This is where knowledge of history is useful, to say the least, because people who are not French are not familiar with the extent to which Roman Catholic clergy used to proselytize Protestants against their will (Dhont, 2002).

History unfolds and is neither the product of slow, incremental change, nor the product of a process of punctuated equilibrium. Instead, time goes by, some things change, others not, and never in a predictable manner. It is as the historian Trygve Tholfsen wrote: “The cardinal features of historical thinking, then, reflect an interest in the dimension of time in human life. The historian approaches the past through categories of diversity, change, and continuity.” (1967, p. 6) This is as true for the tumultuous years leading up to and following the French Revolution as it is for the seemingly calmer Victorian age. And yet, it was at the time of the Atlantic Revolutions that multiple processes unfolding over centuries culminated and coalesced into a new foundation for government in society. The separation of church and state is as important a cornerstone to Western systems of governance as are the separation of politics and administration and of office and officeholder. And it is fortunate that where positive law reigns supreme, rulers can be and are held accountable to the people.

Nation Building: From Subjects to Citizens

Without doubt the Age of the Atlantic Revolutions represents a watershed in the development of government, and then especially in terms of the development of a new institutional superstructure. People, however, do not change as fast. Major institutional changes such as independence from a colonial power or the change from dictatorship to democracy may seem to happen in the blink of an eye, but people adapt more slowly. The biggest change that was wrought because of the Atlantic Revolutions is that people no longer were subjects and became citizens instead. For centuries, nay millennia, people simply were subjects, with as much as 95 percent of the population without any political power and without any hope of improving their lot. From the late eighteenth century on, though, they increasingly became equal in the eyes of the law.

In all fairness, the notion of a universal community of people dates back to the Stoic philosophy of Zeno (334–262 BCE), who argued that it was impossible to govern sizeable and pluralistic societies without some rational order defined by an encompassing common law (Niebuhr, 1959, pp. 73–75). This idea was put into practice when Roman Emperor Caracalla granted citizenship to all freemen in the empire (212 CE, the Constitutio Antoniana), which meant that citizens of Rome or Italy were no longer regarded as superior. The Stoic desire of a universal community of people found its strongest support in St. Paul's letter to the Galatians, in which he pointed out that Jews and non-Jews could sit and share a meal at the same table. The ethics of goodwill and loyalty to those within the covenant was replaced by an ethic of goodwill and loyalty to all (Dodd, 1954, p. 294). Clearly, this did not mean that equality of all was established. Indeed, throughout the world equality before the law would not be spoken of until the late eighteenth century, and would only be realized to some degree from the mid-nineteenth century and well into the twentieth century.

Zeno's vision of a community of people is echoed in the American Declaration of Independence of 1776 (Gawthrop, 1998, p. 70). It is probably the first government-related document in history that proclaimed that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights . . .” and that “to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.” Thirteen years later, the first article of the French Declaration of the Rights of Man also opened with “Men are born and remain free and equal in rights.” It is difficult to imagine the importance of these words today, but with one stroke of a pen people were not just regarded as equal, but—in the case of the American document—actually as sovereign. While sovereignty for time immemorial had rested with a ruler or with a ruling elite, and where governments had existed to serve those in power, sovereignty since the late eighteenth/early nineteenth century was now vested in the people as is expressed in the fact that governments now derived powers from the consent of the governed. Obviously, one sentence did not flip a switch in people, shedding their identity as subjects and remaking them citizens. It would take most of the nineteenth century to turn Americans and Europeans into citizens and into members of their nations.

Nation building is a process that happens in various ways. A country can be built around a specific ethnic core, just as happened in Iceland. In many countries, though, there are other “nations” next to this ethnic core (for instance, the Frisians next to the Hollanders in the Netherlands). This is certainly the case in territories that were occupied by colonizing powers and where the immigrant population became the dominant one (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States). In African countries it is much more common that the immigrant population remained small, and that there was an ethnic group prior to the creation of the state. In fact, African states often have multiple ethnic groups. Nation building is a bottom-up process that happens when people identify with and codify a particular past, language, and customs as distinguishable from that of other people. This happened in England in the course of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. In France it did not happen until the eighteenth century (Greenfeld, 1992, pp. 30–87 and 154–177). In the contemporary world, nation building is more often a top-down effort to assure that people from different backgrounds identify with the state and its government. In the case of top-down nation building, nationalism is a powerful instrument on the part of governments to help tie people together as citizens.

The process where people identify with a country does not happen overnight. Liah Greenfeld may have said that France became a nation in the course of the eighteenth century, but she specifically referred to the final subjugation of territorial lords (such as the dukes of Burgundy and of Brittany) to the monarchy. Hence, by the eighteenth century France had become a state where all political power was concentrated in one body. What about the common French? In a phenomenal book Eugen Weber analyzed how peasants slowly turned into Frenchmen, but that did not happen until the later nineteenth century (1976) and then only as a consequence of various centralizing forces, such as the emergence of railroads, universal military conscription, and the creation of a uniform school system and curriculum throughout the territory. (Nota bene: The idea of a grade-based school system originated with Napoleon Bonaparte and was implemented in France between 1802 and 1808, and has since then spread across the globe.) The same process of slowly becoming a nation unfolded in the Netherlands. Created a unitary state in 1798, the Netherlands did not become a nation until the second half of the nineteenth century (Knippenberg and De Pater, 1988). Regional differences, though, had not disappeared (the old provinces of the Republic). In most European countries, the state comes to express itself through unifying symbols such as a flag and a national anthem in the course of the nineteenth century (Fisch, 2008). Also, states embellish or emphasize certain parts of the historical past that citizens can be proud of by, for instance, creating monuments celebrating famous events or people. Upon independence, all states create such symbols of unity. That people identify with a state through very abstract symbols is thus of very recent origin. Finally, a continuum of the evolving change in the role of citizens in modern nations/states is suggested by Vigoda (2002a). Simultaneously, the relationship between citizens and nations/states is transforming and putting heavier obligation on all the involved parties.

Citizenship as Layered Phenomenon

Equally recent is the idea that citizenship is related to the abstraction of the state rather than to a specific physical-geographical area. Nowadays, citizenship is a multifaceted and layered concept that includes both very concrete as well as very abstract identifications.

First, and concerning concrete aspects of citizenship, itis defined by being an inhabitant of a particular area (city, town, region) by birth. Citizenship is, thus, experienced in a geographical context, and for much of history the physical environment people identified with is local and, at best, regional. If localities “belonged” to a ruler far away, as was the case in empires, people were not likely to have identified as citizens of that empire. In fact, for most of history people could not fathom a world beyond a 20- to 40-mile radius around their place of residence (Diamond, 2012). In the past two centuries, though, people have been increasingly able to experience citizenship at multiple levels. That is, citizenship is no longer limited to contact with one's neighbors and townsmen; it may now easily include contact with fellow countrymen (i.e., all citizens within a state) and with like-minded spirits in other countries (Heater, 1990, pp. 318 and 323). Indeed, it is through the power of the social media (Facebook, Twitter) that citizens have come to connect with each other across regions and borders despite efforts of the regimes in power to subdue the uprisings that are collectively known as the Arab Spring (2010-present). Finally, there are numerous challenges that are truly global by nature and that cannot be addressed successfully by individual territorial states. Just consider global warming and climate change, economic inequalities and poverty, the financial power of multinational corporations, air and water pollution (for instance, the Pacific Trash Vortex that is suspected to be twice the size of the United States; see sprinterlife.com 2012), the international trafficking of women, and so on.

Another way of imaging the multifaceted nature of citizenship is that it can be seen as operating on individual and collective levels (that is, levels of analysis) as well as on organizational and communal/national levels (that is, settings of citizenry action). Microcitizenship concerns employee behavior in the workplace. Midcitizenship emerges out of the action of an organizational group and includes team-building strategies, quality circles, and so forth. Macrocitizenship refers to altruistic behaviors of individuals in national and communal settings. Finally, metacitizenship regards collective action of citizens in the larger society (e.g., voluntary associations) (Vigoda and Golembiewski, 2001, pp. 283–286).

One might expect that a strong sense of citizenship develops when people feel that they are treated well by their public authorities and, more specifically, are satisfied with the quality of public services. However, research has shown that when people are content, their inclination to engage in active political participation and community involvement declines (Vigoda, 2002c, p. 266). Apparently, when all goes well, citizens do not see the need to be involved.

A second, more abstract notion of citizenship is that it presumes a set of duties and rights that can be respectively expected and enjoyed by those who live in a country. As is clear from earlier, for most of history the majority of people only had duties. However, once they came to be recognized as citizens in a legal sense (i.e., equality before the law), this had to be translated into specific citizen rights. Thomas Marshall (1965, pp. 78–91) distinguished three types of citizen rights. The first to be established were the civil rights that included freedom of speech, freedom of association, and the right to start a business without fear of nationalization. These rights were monitored by the court system. In the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries people also acquired political rights, such as the right to vote and the right to be voted into office, and this was pursued and supervised by legislatures at the national and subnational levels. Finally, people also were given social rights such as universal health care and education. It is access to education that has especially shored up the notion of citizenship, because through it individuals have been socialized into being citizens. Civics classes and courses in national history and government were aimed at helping people transcend their individual identities (especially elements of identity that were/are grounded in religion, region, language, history, and customs) (Heater, 1990, p. 88).

People still identify with a specific region and country, and they can do so in two ways. They can identify on the basis of territory, as is the case with the French; that is, state-centered ideas of citizenship, building upon centuries of state making and followed relatively late by a sense of nation. Or they can ground citizenship in a sense of nationhood, as is characteristic for the German lands, where nation (i.e., an organic, cultural, linguistic, and racial community) preceded state by at least two centuries. Either sense of citizenship comes under pressure when original populations clash with mushrooming immigrant populations. This takes us into the third, most abstract notion of citizenship. The education for citizenship briefly described in the previous paragraph is intended to make people open-minded, tolerant, and respectful of others. In a situation where the majority of the population is homogenous, such education is fairly successful. When nationality and state are closely aligned, immigrants can easily be absorbed into the original population provided their numbers are small. In that situation, citizenship is internally inclusive and externally exclusive (Brubaker, 1992, p. 21).

When internally inclusive it is egalitarian, for providing most inhabitants with the same civil rights while, at the same time, it excludes foreigners. In that case citizenship is a mechanism for closure, for it assumes and provides for a self-perpetuating community of people. Marshall's three categories of rights, mentioned earlier, are internally oriented. With increasing international migration since the Second World War, and especially with migration from developing countries to Western countries (Arnold, 2010), many countries have been moving toward a concept of postnational citizenship, where civil and social rights are extended to foreign nationals living in the country. In this case, generally, political rights are not included. This category of citizens is known in the literature as denizens (in the United States: resident aliens). Finally, there is multicultural citizenship, which sets specific groups of immigrants apart as a protected ethnie (these three types of citizenship—closure, postnational, multicultural—are from Gibney and Hansen, 2005, pp. 86–90).

The traditional meaning of citizenship as one that can be equated with national identity is under stress. A variety of countries seek to manage immigration through policies that emphasize the obligation to not only learn the language but also develop a sense of loyalty and belonging to the new country (Kofman, 2005). And several countries pursue integration policies that are presented as inclusive but are intended to achieve exclusion (Goodman, 2009, pp. 183–184). While state may be a rather static phenomenon when territorially defined, nation is sooner culturally defined, and with growing population diversity in countries governments cannot but support cultural pluralism. After all,

Culture and cultures are always in flux, and [ . . . ] individuals normally relate to culture through the acknowledgement of multiple affiliations and allegiances, and through participation in diverse practices, customs, and activities, rather than through association with some fixed and determinate culture. [Thus] . . . states should be maximally accommodating [ . . . ] the cultural variety that free individuals inevitably exhibit.”

(Scheffler, 2007, pp. 105–106)

This is easier said than done. The Netherlands is one of those countries where since the mid-1990s assimilation instead of multicultural policies has been pursued. Citizenship policy today should be targeting the development of a public political culture, where people identify with the state and do not feel forced to abdicate their own culture.

A Future for State, Nation, and Citizenship?

No matter how we look at it, the territorial state is still the dominant type of polity. It is true that other actors are increasingly visible as participants in the provision of collective services. This is generally referred to as governance, and then often presented as if a new phenomenon. We argue that it is anything but. Formal government organizations have throughout history worked with other societal organizations such as organized religion and (in Europe) trade and craft guilds. If the state is hollow in the range of services it provides itself, it is still very much a key actor in defining public policy. We have to reiterate here that the state is the only actor left that can act with authority (and thus legitimacy) on behalf of the citizenry at large. It may not be anything more than that, but it certainly is not less.

In the past century state has been coupled with nation, but this may be born more from nostalgia for a community that never existed than from the realities on the ground. The true nation-state hardly ever existed, simply because most territories that were defined as a polity had multiple nations, i.e., culturally distinct groups of people, living within their jurisdictions. However, as one of the authors of this book remarked before, once state making and nation building complemented each other, the welfare state, which basically defines and provides social rights, could be born (Raadschelders, 1998b, p. 254). And it is that welfare state that is under siege at the same time as that citizenship has become problematic.

If only territorially and politically defined, citizenship should not be an issue to most people, for it simply extends civil and social rights to the entire population. Citizenship becomes a challenge, though, once minorities acquire sufficient numbers so as to legitimately claim political rights as well. In various Western European countries, second- and third-generation immigrants now hold elective office at the local, regional (provincial), and national levels. Beyond this, concerns about citizenship appear to be mostly driven by the inflated notion that “national identity” is in jeopardy because of large numbers of citizens of foreign descent. In that view citizenship becomes an object of narrow-minded nationalism, and, while we think the state is here to stay for a while, that nation when equated with postnational citizenship is here to stay as well; we can no longer afford to perceive citizenship as national identity. Considering the extent that people can travel nowadays, and the extent to which they seek economic opportunity wherever their skills may take them, governments cannot but pursue a policy of multicultural citizenship. Anything less will result in a division between first- and second-class citizens, and would be an affront to anyone who adheres to fundamental equality before the law.