CHAPTER EIGHT

BUREAUCRACY AS PERSONNEL SYSTEM AND POLITICAL-ADMINISTRATIVE RELATIONS

In Chapter 6 we made the case that for most of history bureaucracy was the instrument that supported those in power; seldom did mandarin-bureaucrats work for the people. We argued that in some parts of the world this has changed in the past 200 years or so. Bureaucracies have shown they can work for the people while supporting the political leadership elected into office. Bureaucracy is the most efficient of the organizational structures we know, but that does not mean that it adequately constrains the potential for maladministration by individuals (Tiihonen, 2003). Bureaucracies are networks of people, and not everyone is reliable, competent, citizen oriented, collegial, and altruistic. Every bureaucratic organization will have some incompetent, self-oriented, unreliable, and even corrupt employees (see also Chapter 6). Plenty of evidence for this can be found worldwide in public organizations, in multinational corporations, businesses, churches, sports associations, scouting troops, and so forth. This is not specific to bureaucratic organization, even though some have argued that it dehumanizes people (for instance, Merton, 1940; Hummel, 1977). Corruption, maladministration, selfishness, and so forth are simply part of the human condition. However, the extent to which bureaucracies can be used for selfish purposes varies greatly from country to country, and it seems especially to depend upon whether it is embedded in a pluralistic democratic system. The chance that bureaucracy can and will be used for evil or for purposes of exploitation are most limited in the polyarchal competitive system described in Chapter 5. In the other party-prominent systems the chances are greater that bureaucracy serves those in power, while they are greatest in bureaucratic-prominent regimes. This is best illustrated by looking at the corruption index that is published annually by Transaction International (Section 1). States can move from being extractive to becoming a service delivery state when the criteria for employment in its organizations and agencies are professional rather than personal. Thus we will discuss bureaucracy as a personnel system by means of Weber's ideal type (Section 2; the part of this ideal type that concerns bureaucracy as organization has been discussed in Chapter 6). It is important to understand that Weber's formal definition of bureaucracy as a personnel system regards public servants from a juridical perspective. However, several types of civil servants can be distinguished when applying a more sociological perspective (Section 3). Next we will look at the personnel size of the civil service, both in terms of its absolute numbers and as a percentage of the workforce (Section 4). Career civil servants by far outnumber political officeholders, but we already noted in Chapter 6 that in pluralist democracies this has not proven to be a problem. A professional civil service system is somewhat autonomous from the political leadership, and that requires attention for political-administrative relations and for the role career civil servants play in advising political officeholders (Section 5). Earlier we described momentous changes in the superstructure of governments from the late eighteenth century on (Chapter 3), and in this chapter we will discuss how those changes influenced the development of personnel management in the Western world (Section 6). In the conclusion we will briefly reflect on the importance of career civil servants for policy making and implementation.

The Importance of the Personnel Function for Responsive Government

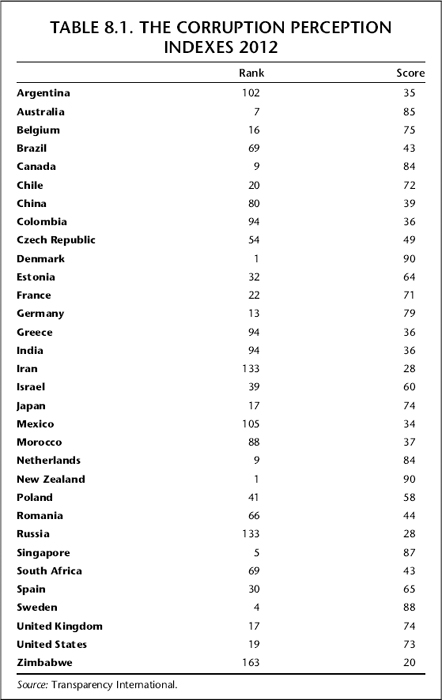

In a way bureaucracies are abstractions because we cannot really “see” them. The behavior of public servants, though, is significantly shaped by the institutional arrangements in which they are embedded. Indeed, while the big donor countries focused their development aid initially on the development of infrastructure and heavy industry (1950s and 1960s), then on providing basic needs (1970s and 1980s), they finally considered institutional development to be the most important factor in the effort to enhance a country's overall economic prosperity. Bi- and multilateral donors increasingly demand administrative reforms, and one of these concerns the human resource function. How do governments across the globe compare when it comes to the professionalism of their bureaucracies? There is quite a bit of research available into recent developments in civil service systems in Africa (Adamolekun, 2007), Anglo-American countries (Halligan, 2004), Asia (Burns and Bowornwathana, 2001), Central and Eastern Europe (Verheijen, 1999), and Western Europe (Van der Meer, 2011). One of the important features where governments significantly differ is the extent to which its public officials are perceived as corrupt. Since 1995 the Berlin-based nongovernmental organization Transparency International annually publishes a corruption perception index. This index suffers from many methodological problems, but for lack of alternative data we used it. No country is corruption free. Corruption is measured on a scale from 0 (highly corrupt) to 100 (not corrupt) and is based on expert opinion. Denmark, New Zealand, and Finland are ranked first with a corruption index of 90. All developed industrial countries are much less corrupt than developing countries. Somalia is ranked one hundred seventy-fourth with a corruption index of 8. In Table 8.1 the corruption ranks and indices are provided for the 32 countries of which a policy area is discussed in Chapters 9 to 12.

Both the market and the state influence the social order, and in the effort to establish a more just society, a balance must be struck between the two. To what extent should societies rely on the self-regulating control of the market? The answer to that question determines the extent to which the state is needed to intervene and correct some of the inequalities and externalities that are created by the market. We noted in Chapters 2 and 3 that state intervention for most of history was very limited, that states and their governments were small in comparison to today in terms of personnel size, and that they did not really provide many services for their subjects. Today's welfare states offer a wide range of services to citizens, and these are not enough as demands and expectations keep rising; public bureaucracies are no longer only exploitative and extractive. Based on the World Values Survey, Patrick Flavin and others (2011) investigated the relationship between size of the state (as measured in tax revenue as percentage of gross domestic product [GDP]; government consumption of GDP; unemployment benefits; and social welfare expenditures as a percentage of GDP) and self-reported life satisfaction. They focused on 15 industrialized democracies (Australia, Canada, Finland, France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United States) and found a strong positive relationship between state intervention in the economy and subjective well-being, and that was not limited to those of whom one can expect that they are more affected such as lower-income and lower-status citizens and pro-state liberal-left citizens (for non-American readers: Liberal in the United States refers to the left of the political spectrum, while in Europe it refers to the right of the political spectrum). In general, state interventions that compensate for market deficiencies appear to produce greater levels of human happiness (Flavin and others, 2011, p. 264).

Obviously, leaders of less-than-democratic political systems intervene in society as well, but their bureaucracies operate like the premodern bureaucracies upon which the stereotype of bureaucracy is based that we described in Chapter 6. A modern civil service system assures professionalism and is able to deal with instances of corruption.

Defining Bureaucracy as Personnel System: Max Weber's Juridical Perspective

Wherever organizations are populated by people on the basis of kinship and friendship, and where public office can be inherited, traded, or even sold, the chances that the organization is used for personal rather than public interests are substantial. We cannot point out enough how momentous the changes in the structure and functioning of governments were during the 1780–1820 period. Next to the separation of church and state, of politics and administration, and of collegial and bureaucratic administration, the changes relevant to the topic of this chapter concern the separation of office and officeholder, and a new basis for the relationship between elected and appointed officeholders. Indeed, so different was the nineteenth century career civil servant from his historical predecessor (the mandarin-bureaucrat) that as early as the 1820s W.F. Hegel noted that career civil servants were the new guardians of democracy, indispensable to democratization (1991). It is their professionalism and expertise upon which elected officeholders rely when outlining policy. In fact, more often than not elected officeholders will adopt policy formulations developed by career civil servants.

Hegel captures the new role of civil servants vis-à-vis political officeholders as one that is actively developing and advising about policy. He trusts career civil servants, and his is a sociological perspective that concerns how career civil servants can and should function in the real world. This contrasts sharply with Weber's formal and juridical definition of bureaucracy as a personnel system (seen in the following list). Befitting the principle of a clear division of labor, the first dimension is a departure from historical practice where one office could be held by multiple people (for instance, in a collegial organization), and this is still the case with any of the political institutions (especially legislatures; often also judiciaries). Dimensions 10 to 13 identify the nature of their relationship with elected officeholders and the reasons why someone should be appointed in a career position. Especially dimension 12 should serve as a safeguard against nepotism. Dimensions 14 to 20 concern the work conditions: Civil servants are protected from the vicissitudes of working in a political environment to which career officeholders are subjected in exchange for their loyal support of whichever political party (or parties in a coalition) is in power. As mentioned before, this is a definition of bureaucracy that fits a polyarchical and democratic system of government. It is also a definition that does not differentiate between rank or status: A municipal employee collecting garbage is as much a career civil servant as a director-general in a national government department.

Bureaucracy as a Personnel System1

9. Office held by individual functionaries,

10. who are subordinate, and

11. appointed, and

12. knowledgeable, who have expertise, and are

13. assigned by contractual agreement

14. in a tenured (secure) position, and

15. who fulfill their office as their main or only job, and

16. work in a career system, are

17. rewarded with a regular salary and pension in money,

18. rewarded according to rank, and

19. promoted according seniority, and

20. work under formal protection of their office.

Weber's contemporaries on both sides of the Atlantic noticed that the role and position of governments were changing in response to rapid changes in the social environment (industrialization, urbanization, population growth). How to evaluate these changes was difficult since there was no historical precedent. This ambiguity in the assessment of bureaucracy and of bureaucratization is visible in the words of the (German-born) American journalist H.L. Mencken. On the one hand, he was very much aware of the harm that spoils and nepotism in the public sector had done to American society, and he favored a rational, efficient, and honest government. He also clearly distinguished the historical from the modern bureaucracy: “The extortions and oppressions of government [. . .] will come to an end when the victims begin to differentiate clearly between government as a necessary device for maintaining order in the world and government as a device for maintaining the authority and prosperity of predatory rascals and swindlers.” (quoted in Nolte, 1968, p. 118) At the same time, on the other hand, he was weary of the “reach” of government, noticing how “government has now gone far beyond anything ever dreamed of in Jefferson's day. It has taken on a vast mass of new duties and responsibilities; it has spread out its powers until they penetrate to every act of the citizen, however secret; it has begun to throw around its operations with the high dignity and impeccability of a state religion; its agents become a separate and superior caste.” (quoted in DuBasky, 1990, p. 377)

A century after Mencken wrote this, governments in industrialized, developed countries have grown to an extent that even Mencken could not have dreamed of, but have its “agents” become a separate and superior caste? The answer possibly depends upon national culture. While Weber defines bureaucracy in a manner that allows for comparison to existing bureaucratic organizations, he was well aware of the fact that the functioning of bureaucracy was embedded in and constrained by national traditions and culture (Widner, 2007). American culture is one where civil servants do not enjoy high social status, suspicious as Americans are of anything that reeks of big government (Wills, 1999). In France, Germany, and in the Scandinavian countries civil servants are highly regarded, especially those employed at the national level. Historically, Chinese mandarins enjoyed high social status because it took many years to complete the studies required for such positions. Germany and France were the two countries where the first university-level professorships, curricula, and handbooks emerged in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, respectively.

Categories of Public Servants in a Sociological Perspective

In a legal or juridical perspective anyone appointed in a public sector position with a career track is a civil servant, from the garbage man to the director-general. In a sociological perspective, though, there are different categories of public officials, and the better concept to capture all of them is that of public servant. There are two main groups of public servants. On the one hand there are elected officeholders, political appointees, and citizen officeholders; on the other hand there are career civil servants of which there are several types. In this section we will discuss the various types of public servants and provide information about their changing size over time (in the next section we will compare present sizes of civil service systems across the globe). The types of public servants and their changing size over time are drawn from Raadschelders's (1994a) work on changing size and composition of the workforce in four Dutch municipalities between the years 1600 and 1980. Obviously, we have to be careful about making generalized statements regarding size and composition of the civil service over time when it is based on research limited to four Dutch municipalities. However, there are no data elsewhere as far as we know, and we do think that some statements can be made that people in most countries will recognize.

Political officeholders are generally elected into public office. That is especially the case with legislators at the national, regional, and local levels. Executive officials at these levels of government are generally elected as well (president, governor, mayor). In many countries around the world the number of people elected into public office is generally limited to the top political positions. As far as we know, the United States is an exception because a variety of public officials at state and local levels are elected rather than appointed (for instance, state superintendent for education, secretary of state, attorney general, county commissioners, sheriffs, coroners, judges, and so forth). This reflects the American distrust of “unelected bureaucrats.” Political officeholders used to be a substantial category of public servants, almost 25 percent of the total public workforce in the year 1600 in those four Dutch towns. We suspect that those who we nowadays would label as political officeholders constituted a sizeable percentage of public servants anywhere in the premodern world, simply because the number of people employed in a position that we today would characterize as career civil service was very small. We find the same in the early United States (White, 1965, p. 256). Today, in most developed countries political officeholders occupy between 1 and 2.5 percent of public sector positions (for the United States see Milakovich and Gordon, 2004, p. 19).

The second category of public servants is those who are neither elected nor appointed to a career position, and there are two subtypes of them. First, political appointees who serve at the pleasure of elected officeholders. The best-known example in the world is that of the American president who has the authority to appoint individuals to high-level positions in federal departments and agencies (and for some of these, congressional approval is required). We have no comparative data on the size of political appointees over time. Prior to the modern era we assume that the number of political-appointee (or patronage) positions was substantial (certainly in the United States, see Raadschelders and Lee, 2005), simply because those who acquired government jobs were often somehow related to those who had the authority to give out jobs. There are political-appointee positions in many countries, but there are clear differences. First, there is a substantial difference between developed and developing countries. In the former the number of political appointees is generally limited to the top levels in public organizations, but there is interesting variation. The United States has probably more political appointees than any of the other developed countries; at the federal level alone there are at least 7,300 (and of these 10 percent are recruited from among the Senior Executive Service; see Stillman, 2004, p. 131). There are hardly any purely political appointments in Germany. In France this type of position is limited to ministerial advisers, but their numbers are constrained by budget. Hence, and except for the United States, most appointments in the career civil service are merit based. In many developing countries political affiliation (as well as kinship and friendship) is still the primary selection criterion for positions in public organizations, but the trend is toward a system based on merit (World Bank, 2013).

The second subtype of nonelected and noncareer civil service officials are citizen functionaries who work in government but on a voluntary basis and without salary. Examples include citizens who serve on boards and advisory committees, and many of those can be found at the local level (for instance, library board, planning and zoning board, parks and recreation board, and so on). We suspect these have been very important in premodern government. In the four Dutch municipalities, they constituted 18 to 29 percent of the public workforce between 1600 and 1950. After that, their numbers declined, to disappear pretty much in the 1960s. As far as we know, there has been little research on the role and size of citizen functionaries in other countries. From unpublished research Raadschelders did in the city of Norman, Oklahoma, we know that citizen functionaries constituted about 25 percent of the local workforce around the year 2000. At the local level, citizen functionaries may become more important again, as Bovaird and others report for various countries (2014). We can find citizen functionaries also at regional and national levels of government, for instance as members of special advisory committees to the executive.

The second main group of public servants is that of career civil servants. They include anyone who works for a salary and is appointed on the basis of merit (that is, a combination of educational background and practical experience), and there are five subtypes. The first is that of administrative officials or civil servants in a sociological sense. They are the white-collar workers who help to develop and implement policy and who draft regulations, ordinances, and laws. They are desk workers and include managers and supervisors as well as clerical and administrative support personnel. Their work mainly requires intellectual capacity and very little physical effort. Before the modern era there were not many civil servants: in the four Dutch municipalities less than 6 percent of the total public workforce in 1600. However, by 1980 they amounted to more than 30 percent of the local workforce. At national-government levels this subcategory of civil servants has grown even faster and by far dominates those in elected or politically appointed positions, and this is mainly because national governments have decentralized, contracted out, and even privatized various tasks and services that require physical, manual effort. The extent varies from country to country, but there is a worldwide trend of bureaucratization; that is, national public organizations are becoming more and more truly knowledge-based organizations with predominantly white-collar workers. This is less strong a tendency at the local level because local government provides a range of services that require laborers (see later).

The second subtype of career civil servant is that of technical and professional personnel. They usually occupy lower-ranking positions and wear a uniform so that the line of authority is clear and cannot be disputed. In fact, in most countries where public sector jobs involve the possibility of physical harm or even death, the workforce is uniformed. Examples include police, correctional, firefighting, and military personnel. Their jobs are a mixture of intellectual and physical labor. Higher-ranking officials in these types of organizations are really civil servants, desk workers, even though they are uniformed (for instance, police chief, fire chief, general officer). Relying upon their numbers over time in the four Dutch municipalities, in relative terms this subcategory of career civil servants has declined, but in absolute numbers they have actually increased. This is a function of the fact that this type of work belongs to traditional public services that concern the protection of the territory and the maintenance of public order and safety.

The laborer or blue-collar worker is the third type of career civil servant, and they perform tasks that mainly require manual, physical labor. Their numbers used to be substantial (more than 27 percent in 1600 in the four Dutch municipalities), and they included street sweepers, market personnel, cleaning personnel, and (in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries) also laborers in public gas and electricity factories, laborers in public works and in the parks and recreation departments, and mechanics (for the maintenance of a fleet of cars). In developed countries their numbers have declined in both absolute as well as in relative terms, and especially at the national and regional levels because of technological changes that made certain jobs obsolete as well as because of contracting out and privatization. At local levels blue-collar workers can still be found, then, for instance, in parks and recreation departments, the local sanitation departments (for garbage collection, among other things), and local water plants. In developing countries their numbers can be significantly higher. For instance, 80 to 86 percent of local personnel in Tunisia are characterized as blue collar, while this ranges from 52 to 57 percent in Morocco. White-collar workers comprise 7 percent (Tunisia) and 27 percent (Morocco) of local public personnel (UCLG, 2008). These data can be found in country profiles that have been compiled upon the initiative of the World Bank and an international forum organization called United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG). They provide country profiles of many countries on all continents, but the information on size and composition of the local public workforce varies a great deal.

Uniformed medical personnel is the fourth subcategory of career civil servants. We suspect that their numbers have always been below 10 percent of the workforce. In the four Dutch municipalities during almost four centuries it was not more than 5 percent of the workforce; in the United States in 2001 health care professionals amount to 8.3 percent of the total public workforce at federal, state, and local levels combined (U.S. Census Bureau, 2003, Table 468, p. 312). We can distinguish from white-collar workers since their work not only requires extensive education but is also very physical by nature (consider nurses lifting patients; surgeons in the operating theater for hours). It is the level of education that separates them also from professional and technical personnel as well as from blue-collar workers as defined above.

The final subcategory of career civil servants is that of educational personnel. As a percentage of the public workforce their numbers were small in premodern times, but they have grown rapidly from the nineteenth century on. In the four Dutch municipalities in 1980 more than a quarter of all public personnel worked in education. The size of the educational workforce varies quite significantly from country to country. For instance, in the Netherlands about half of all educational personnel work in private (denominational) schools. In the United States and Israel, on the other hand, almost 90 percent of all educational personnel work in the public sector. Out of a total of more than 21 million public servants in the United States, 9.9 million are in education and almost three-quarters work in kindergarten, elementary, and secondary education (U.S. Census Bureau, 2003, Table 438, p. 280).

In the developed countries many of these career civil servants have frequent contact with citizens and can then be called street-level bureaucrats (Lipsky, 1980), and they amount to about 70 percent of the public workforce. The other 30 percent can be called policy bureaucrats, for they are the designers of policy and the writers of anything that has the rule of law (Page and Jenkins, 2005). The size and composition of the public workforce will vary with level of government and with the range of publicly provided services. In many decentralized, developed countries local government is truly big government since most public sector personnel are employed at that level. Also, most decentralized and developed countries offer a wide range of services, well beyond the traditional services that governments provided since antiquity. It is to the size of government in the present age that we now turn.

Variation in the Size of the Civil Service

In absolute terms public sector personnel size has grown enormously in the twentieth century.

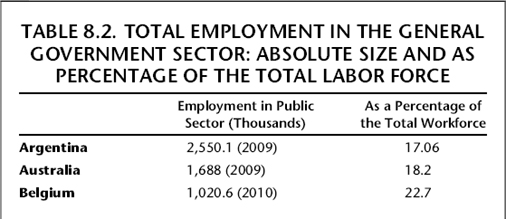

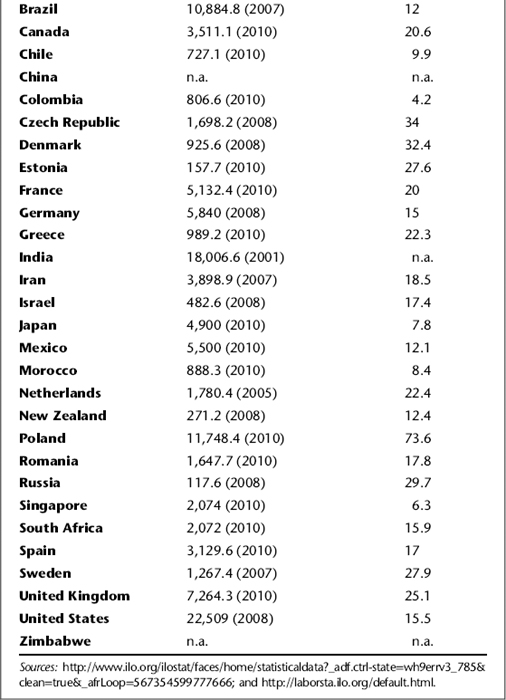

This is both a function of urbanization as well as of governments meeting increasing citizen demand for services. In Table 8.2 the total public sector size (local up to national level) is provided in absolute numbers and as a percentage of the total labor force for 30 of the 32 countries of which a policy is discussed in Chapters 9 to 12. There is clearly variation. With more than 32 percent of the total labor force, Denmark has the most sizeable, while Colombia with only 4.2 percent has the smallest public-sector personnel size. In an Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) publication the four Nordic countries have the largest public sectors (OECD, 2011) with Finland at about 25 percent and Norway at 30 percent.

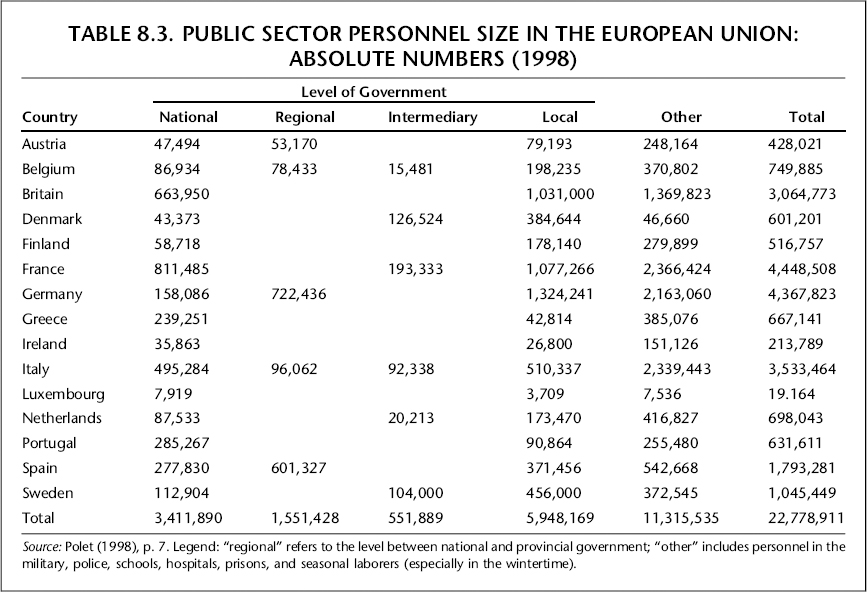

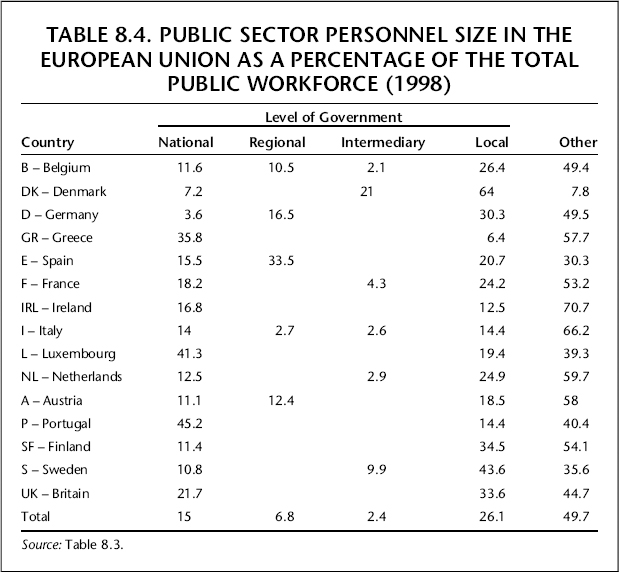

While Table 8.2 provides information about public sector personnel size at all government levels, we can get some idea of the variation across levels of government. The data in Table 8.3 are 15 years old (at the time of writing this chapter) and concern only the European Union with 15 members back then. We can see that in the countries occupied by the Roman Empire (see Chapters 2 and 3) the national and regional government levels are important (France) or even far more important (Greece, Italy, Portugal, Spain). In the Nordic countries, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, local government is clearly an important hub of service delivery. The figure that stands out most, though, is that of the category of “other” personnel that accounts for almost half of all public personnel in the 15 EU countries. In the article from which these data are drawn, the author (Polet, 1998) does not provide an explanation for the significant variation between countries with regard to this category. In Table 8.4 we have translated the numbers of Table 8.3 into percentages, making it easier to see the differences between countries.

In a more recent OECD publication Elsa Pilichowski and Edouard Turkisch provide insight in the proportion of government employment at the federal/national level in comparison to the subnational levels (2008, pp. 26–28). Again, we can see significant variation, with Australia having about 12 percent of all public sector employees at the federal/national level, while Turkey has almost 90 percent at the national level. The United States is around 14 percent, while the Netherlands appears to be at 27 percent. That last number is higher than what is provided in Table 8.2, but we must keep in mind that data are collected according to different rationales. For instance, the data in the OECD 2008 study refer to “General Government” and include not only the core ministries, departments, and agencies but also personnel at publicly owned hospitals, public schools, social security organizations, and so forth. Hence, while it is difficult to collect truly comparative data on public sector personnel size, we do get a sense of the variation across the globe.

Political-Administrative Relations: Intertwinement, Politicization, and Consultation

The size and composition of the public sector workforce is in no way comparable to that of 150 years ago, and certainly not to that of the early modern period. Earlier we referenced some data concerning local government personnel in four Dutch municipalities for a period of 380 years. We also know that on New Year's Eve of 1789 the U.S. Treasury Department had a total of 39 employees, but it is not clear how many of these were political appointees and how many occupied a career civil service position (White, 1965, p. 256). As the demand for public services increased in the second half of the nineteenth century, so did the demand for professionally trained personnel. After all, elected officials were no longer able to monitor all the ins and outs of a rapidly increasing range of public services. In 1900 Frank Goodnow could write the following: “Politics has to do with policies or expressions of the state will. Administration has to do with the execution of these policies.” (1900, p. 18) While Goodnow is often remembered for advocating strict separation of politics from administration, careful reading of his book quickly shows he is much more nuanced. He writes: “The organ of government whose main function is the execution of the will of the state is often, and indeed usually, entrusted with the expression of the will in its details . . . [and that] the execution of law, the expressed will of the state, depends in large degree upon the active initiative of the administrative authorities.” (Goodnow, 1900, pp. 15 and 44; emphasis added) This observation points to growing interdependence of elected officeholders and career civil servants. More than 40 years later Leys observed the same:

We can no longer pretend that executives merely fill gaps that have inadvertently been left in statute and constitution. Legislators admit that they can do little more with such subjects as factory sanitation, international relations, and public education than to lay down a general public policy within which administrators will make detailed rules and plans of action. (1943, p. 10, emphasis added)

Today, more than a decade into the twenty-first century, it is clear that many of the regulations that govern people's lives are enacted by career civil servants as secondary legislation and upon delegated authority (Furlong, 2003; Page, 2001). And so it is that historian and economist Scott Gordon observed:

Legislators pass general laws, leaving it to the appropriate executive departments to construct the specific regulations by which the law is actually implemented. Citizens who find themselves afoul of the taxing authority [. . .] may ask to be shown by what authority they are being charged, but they will then be referred not to a statute, but to a small passage in a large volume of regulations written by civil servants. [. . .] Protection of the people's liberties from arbitrary exercise of official authority requires as much, or more, attention to the pedestrian activities of minor officials than to the majestic proceedings of a Parliament or Congress. (1999, p. 52)

The above observations pertain specifically to political-party-dominated systems, and then especially to the polyarchies. To anyone familiar with public sector personnel in developed countries it is clear that elected and appointed officeholders are very much intertwined, consult each other frequently, and thus are subject to varying degrees of politicization. Information in this and the next section concerns developed countries only, but can be used by career civil servants elsewhere to assess the situation in their own country.

The nature of political-administrative relations requires us to look at the interactions between elected and appointed officeholders at the higher levels of government, the so-called “summit” (unless indicated otherwise: information in this section is drawn from Raadschelders and Van der Meer, 1998, pp. 28–33). Until the first half of the nineteenth century in Europe and until the early twentieth century in the United States, top-level positions in government were occupied by society's socioeconomic-political elites. Political and administrative positions were not very differentiated, and officials were selected on the basis of kinship or friendship (Canada, Finland, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain) or on the basis of spoils (United States).

In the second half of the nineteenth century political parties emerged, and politics and administration became more visibly separated. Sometimes this went so far as to dismiss civil servants when they had declared partisanship, as was the case in Canada (Kernaghan, 1998, p. 102). More important, though, for the awareness that political-administrative relations were changing was the rapid growth of public services. Political officeholders increasingly recognized the need for more professional support and thus hired civil servants with a particular technical expertise (engineers, agriculturalists, architects, statisticians). Government not only grew in numbers but also increased the qualitative range of services provided and policies developed. In return for professional backing, political officeholders granted protection of tenure to career civil servants through enacting Civil Service Acts (for instance, United States 1883, Canada 1918, the Netherlands 1929, France 1946; the earliest known are Bavaria 1806 and Sweden 1809).

Meanwhile, this growth of administrative personnel prompted elected officeholders to strengthen their political control and they did so, for instance, through the creation or strengthening of the office of prime minister (Belgium 1920, the Netherlands 1937, Sweden 1936). Another, more invasive measure was to politicize the top career civil service positions from the late nineteenth/early twentieth centuries on. Even though career civil servants were indispensable to policy making, the top-ranked positions were increasingly subjected to politicization. In most countries the upper ranks of the civil service are to some degree politicized. Exceptions include New Zealand and the United Kingdom. Of the 13 countries in Table 5.3 (Chapter 5), the United States is the only one characterized as very politicized, and this is because there are a substantial number of political appointees wedged between elected officeholders and career civil servants. While they can be found at all levels of American government, they are predominant at the federal level. This is not altogether desirable. On average they serve for only 22 months and thus have a short-term perspective. Furthermore, they mainly interact with other political appointees and elected officeholders and thus do not cultivate relations with the career civil service (Stillman, 2004, p. 132; Ingraham, 2005; Heclo, 1977; Maranto, 2005). In a 2004 report the National Academy of Public Administration (NAPA) noted that political appointees often lack the skills, agency experience, and networks that are vital to the operations of public organizations (NAPA, 2004, p. 66).

As can be expected, politicization has had consequences for the role and position of career civil servants vis-à-vis elected officeholders. Again, in Table 5.3 we can see how in most of the 13 countries civil servants provide policy advice, and in some cases next to consultants, university professors, and political advisers. Indeed, in most advanced democracies civil servants draft policy and legal texts, and then often in collaboration with major societal stakeholders such as labor unions, employer associations, and interest groups. The American case is once again different. Legislators make little effort to broker agreements through negotiations among stakeholders and seldom allow career civil servants to draft legislation (Bok, 2001, pp. 105, 133, and 163). They informally consult civil servants but are not obliged to do so. It is even known that they sometimes have been even explicitly excluded from attending meetings that they used to participate in on a regular basis (Golden, 2000). More than their colleagues in other developed countries they must walk a very fine line between protecting the general interest and advancing the elected official's goals (Ashworth, 2001, p. 9).

Aberbach et al. (1981) distinguish between four images of political administrative relations with image 1 being perfect separation, images 2 and 3 mixes, and image 4 a perfect blend into an administrative state. In general, in the developed world politicians and administrators operate very much according to image 3 (Aberbach and others, 1981). The rigorous separation of politics from administration (image 1) is seldom, if ever, reality. That elected officials articulate and mobilize the interests and values while civil servants provide facts and neutral expertise (image 2) is also unlikely, simply because civil servants have the longevity in office, expertise, and organizational memory. More relevant to contemporary political-administrative relations is image 3, where politicians provide the energy and passion with civil servants serving with pragmatism and caution. We cannot say to what extent the overview here relates to developing countries, but suspect that political-administrative relations are more politicized as a function of appointments being more kinship and/or friendship based. Also, most comparative research into political-administrative relations has been limited to developed countries, so there is much work left to be done regarding the developing world.

Development of the Personnel Function in Developed Countries

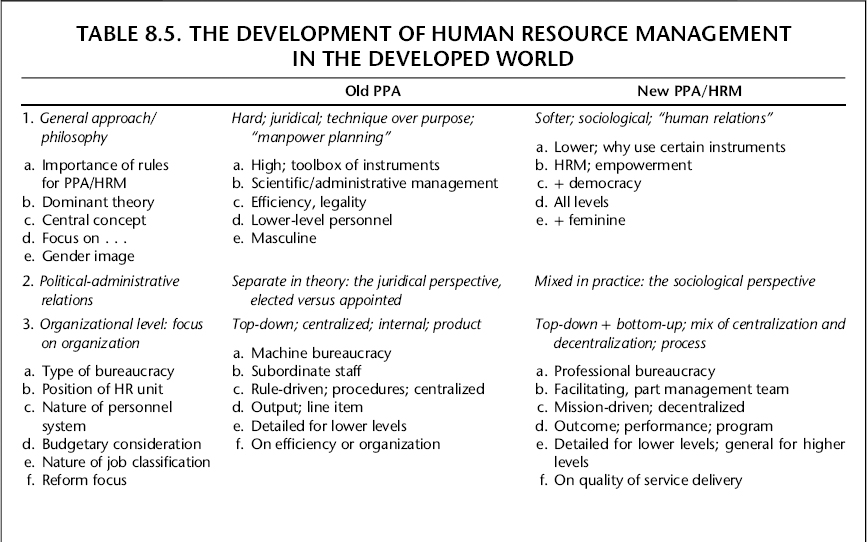

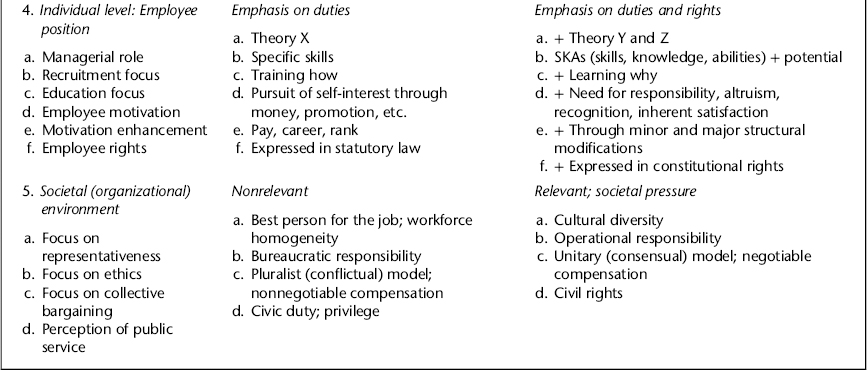

As the political-administrative dynamic evolved in the developed world, so did the public personnel administration (PPA) or human resource management (HRM) function. In this section we will develop a dynamic ideal type of PPA/HRM based on the substance and nature of personnel administration in Western Europe and North America of the twentieth century. It distinguishes between general approach/philosophy and political-administrative relations, how these translated in personnel policy at the organizational level and at the individual level, and how this was influenced by developments in the societal environment (see Table 8.5).

Weber's ideal type of bureaucracy is an elaboration of one element of his more encompassing set of ideal types of authority. The ideal type of bureaucracy is the organizational expression of the ideal type of legal authority (Weber never used the term legal-rational authority; see Raadschelders and Stillman, 2007). Without legal authority bureaucracy can exist, but it cannot come to its fullest expression, and that is because it then serves under traditional or charismatic authority, which is geared to supporting the ruling elite (see Chapter 6). Legal authority thus provides the best possible foundation for a bureaucracy that is somewhat autonomous from the political leadership and serves the citizenry at large on the one hand, yet does not overshadow the political system on the other.

Western society in the third quarter of the nineteenth century was on the verge of change. Industrialization, urbanization, demographic growth, and political emancipation of ever-larger portions of the population together called for a more responsive and professional government. Both in Western Europe and North America the change from an agricultural-rural to an industrial-urban society prompted a swift response from governments, especially in the areas of urban housing, water supply, sewage systems, public transport, road pavement, and so forth. The rapidly expanding public services (both in terms of quality and quantity), especially at local and regional levels, also required a public workforce recruited on the basis of relevant training and skills and professionalism rather than on the basis of patronage.

Personnel management across the Atlantic had been given a more legal foundation from the early nineteenth century on. Personnel management reforms since the 1880s converged on both sides of the Atlantic up to a point. The need to reform and professionalize the public service was expressed in the United States in the emergence of (civil service) reform leagues (for instance, the New York Civil Service Reform Association, 1877; the National Civil Service Reform League, 1881; professional associations; the New York Bureau of Municipal Research, 1906) and the creation of university chairs in political science. In Western Europe it was expressed in the development of “hands-on” curricula by local administrators for local administrators, the creation of professional associations, and the creation of university chairs. The difference between Western Europe and the United States is that in the former politics had been legally severed from administration from the early nineteenth century on and had thus resulted in earlier development of rules for recruitment, selection, appointment, and promotion. Another difference is that in the United States the demarcation of politics and administration was expressed in much stronger terms than in Europe, but the outcome was the same: What the French Revolution had done for European civil servants is what Garfield's assassination did for their U.S. colleagues. It legitimized a separation between popularly elected and expertly appointed public servants.

From the 1880s on, the development in Western Europe and in the United States is remarkably similar, since it is prompted by similar societal changes. On both sides it was during the 1880–1920 period that job classifications were elaborated from which detailed job descriptions were derived. On both sides efficiency became a major concern in the face of a rapidly increasing public responsibility for hitherto “private” concerns. This was expressed in the emergence of research as well as of more systematic teaching of public administration at large and personnel management specifically.

As a consequence personnel management in the United States adopted an impersonal, masculine approach. It became “harder,” searching for and establishing more objective criteria for the recruitment and the selection of civil servants. The same happened in Western Europe but with a difference. Personnel management in Western Europe was approached as a matter of law, while in the United States it was approached as a matter of sound administration built upon the principles of business (think of efficiency). Personnel management in the United States thus found its legitimation in the organizational ideology of scientific management. To be sure, the general approach to PPA on both sides of the Atlantic was initially juridical, since personnel management was especially focused on developing rules and standardized procedures for routing lower and middle level personnel from recruitment to retirement. PPA was a toolbox of instruments, inspiring Sayre to warn against the “triumph of techniques over purpose.” (1948) The foundation may have differed (law or business), but the results were the same: personnel management on the basis of objectifiable and measurable criteria. Personnel managers developed quantitatively oriented and detailed job descriptions, productivity measurements, training programs, efficiency ratings and so forth. Not the individual employee but the organizational mission came first. In both regions this organizational mission was one of improving quantity and quality of public service delivery.

As time went by the concept of personnel management became associated with a traditional and somewhat obsolete approach. Especially after the Second World War the tone turned softer, more feminine, with an eye for human relations and more attention to the nature of the interaction between manager and subordinate. Rules and procedures continued to be important, but the new concept of HRM captured that the attention to organizational mission and individual employee had become more balanced. The new HRM attempted to better balance the demands of efficiency and legality with those of democracy. And finally, personnel management not only concerned lower- and middle-ranked employees. Increasingly, it encompassed all levels in the organization. Popular concepts such as employee empowerment, Total Quality Management (TQM), Management by Objectives (MBO), and strategic management are indicative of a quite different understanding of PPA.

Already briefly touched upon above is that civil service reform was also a response to changes in the perceived nature of political-administrative relations. In Western Europe the separation of politics from administration came in the aftermath of the French Revolution. In the United States the separation of these two spheres was increasingly advocated from the 1850s on. Of course, in a juridical sense they were separated (because they recruited on the basis of either election or appointment) while in a sociological sense they continued to be as intertwined as ever. As a consequence of legally uncoupling politics and administration, personnel management was considered an administrative function. After World War II, scholars and practitioners increasingly emphasized a sociological perspective on the relation between both: They are mixed in practice. Personnel management is thus perceived as operating in a politicized arena. In fact, many of the changes in HRM in recent decades have been brought about because of environmental pressure for better representation of the population (in the United States, for instance of, African-, Hispanic-, and Asian-American people; women; disabled people; senior citizens, gays). Increasing workforce diversity indicates that HRM is influenced by politics and by citizen desires. (By way of side note: In later subsections we will focus on the development of the personnel function in the United States but believe that it is to quite some degree comparable to that of other developed countries.)

The Organizational Level: Personnel Management Focused on the Organization

The old PPA fit in a context where organizations were centrally managed, where a clear unity of command existed, and where the organizational focus was on the service and the product. Old PPA was tailored to meet the requirements of a machine bureaucracy (see Chapter 6) and thus focused on streamlining and standardizing processes of personnel management. As already mentioned, the personnel system was rule driven and emphasized procedures. Staff in the bureaucracy was subordinate to line management and merely provided functions asked for by the line managers. From a budgetary perspective the human resource was a line item; in general the focus in the budgetary process was on output. If reform was considered, it was to improve the efficiency of the organization. Hence in the earlier parts of the twentieth century the employee was regarded as a position, a job. In one of the earliest handbooks of personnel administration it was said thus:

The job is the molecule of industry; and what molecular study has done for physics and chemistry, job study with the aid of every possible instrument of precision can begin to do for industry. (Tead and Metcalf, 1920, p. 255)

Frederick Taylor's time and motion studies had attempted to do just that. What actions with respect to PPA were taken given these changes? The city manager became the local head of the bureaucracy; most appointments fell to his authority. In 1912 the city of Chicago established a job classification system (although in rudimentary form it had already started in other places in the 1850s), shortly afterward followed by the State of Illinois. The 1923 Classification Act provided job classifications for the federal civil service.

Civil service reform was initially undertaken to enhance the efficiency of the organization, but in the course of the 1930s attention shifted to a more proactive public sector in response to the Great Depression. The public sector, for instance, was increasingly seen as a means to alleviate the pressures of massive unemployment. While efficiency continued to be an important consideration, it was management that became the more important principle. The 1937 Brownlow Committee marked the beginning of the “administrative management period” (1937–1955). There was still hope that principles of management (for instance, Gulick's POSDCORB: planning, organizing, staffing, directing, coordinating, recording, and budgeting) and principles of organization (such as Gulick's typology of foundations of organization: goal, area, process, clientele) would be discovered. The following quotation is taken from Mosher's analysis of the Brownlow Committee report and captures the beginning of a new style PPA:

Personnel was seen as a principal, if not major, tool of management. [It] should be organized as a staff aid integral to the operating organization, not as a semi-independent agency. [. . .] it should operate primarily as a service to managers up and down the line, not as a watchdog and controller over management [. . .] At the top level [personnel management] should be concerned with the development of standards and policies. Personnel operations [. . .] should be decentralized and delegated to bring them into more immediate relationship with the middle and lower managers whom they serve. Personal and interpersonal considerations should be reintroduced into personnel administration, even if they cost some degree of objectivity and of scientific technique. (Mosher, 1968, p. 82; emphasis added)

By the time that the second Hoover Commission presented its report entitled Personnel and the Civil Service (February 1955), personnel administration was firmly a part of management functions. As a consequence the focus on personnel management at the organizational level combined top-down and bottom-up perspectives and advocated a functional mixing of centralization and decentralization. Personnel managers served an increasingly professional bureaucracy and acted more and more as an integral part in developing and achieving the organizational mission. “Outcome,” “performance,” and “quality” became keywords underlining this mission-driven orientation. This had also very tangible consequences for personnel management. Job descriptions now were extended to include the higher positions in the organization. They became more and more detailed for lower- and middle-level positions and more general at higher-level positions. In the decades that Mosher labeled the “professional period” (1955–1970), the diversity of the public workforce increased rapidly in terms of educational background. Henceforth HRM had to take into account that it provided services not only to blue-collar positions and lawyers, but also to scientists, social scientists, educators, economists, medical doctors, nurses, and political and administrative science graduates, all working in policy-making positions.

Especially in Anglo-American countries we have seen attention to management resurface in the form of new public management (NPM). Many people believe that a focus on performance will improve the quality of public services, and so a variety of reforms were attempted, including civil service reforms. This involved the effort to make public managers more responsible for outputs specified in annual performance contracts and was, for instance, implemented in New Zealand. There is attention for improving management through civil service reforms in other countries as well, but the results have been mixed. On the European continent NPM has been much less influential simply because of a political-administrative culture that is very different from that of Anglo-American countries (see Chapter 6). Civil service reforms in the NPM mode were not regarded as beneficial in developing countries, simply because a tradition of formal contracts and mechanisms to enforce them was missing (Schick, 1998). Indeed, in Mongolia, for instance, New Zealand-style reforms failed for various reasons (difficulty in assigning a cost to outputs; lack of time; difficulty in assessing quality; lack of incentives) (Hausman, 2010, p. 9).

The Individual Level: The Employee as a Person with Rights, Needs, and Feelings

Under old PPA the theory about manager-employee relations was dominated by what Douglas McGregor called “theory X.”' (1960). The employee had to be supervised because he was essentially lazy. The general idea was that the employee was motivated by salary and promotion. In the labor relationship the emphasis was on duty. The employer “bought” your time between 9 and 5, which meant that as soon as you walked in your office you ought to have left domestic worries behind. Of course, in reality it was not like this, but it did have very practical consequences for personnel management. Given the emphasis on duties, given clearly defined tasks, and given fairly detailed job descriptions, the educational focus, for instance, was on training for specific skills. The focus of recruitment was on specific skills. Legislative activity relevant to work conditions mainly concerned statutory law that regulated job description and classification, pay, hours, and benefits. The 1883 Pendleton Act, the 1923 Classification Act, and the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act are good examples.

From the 1960s on, the emphasis shifted to a combination of duties and rights. Manager-employee relations were now interpreted as theory Y without forgetting the “teeth” of theory X (free after Aristotle: “laws must have teeth”). The employee was internally motivated to do the job and derived satisfaction from more than just the pecuniary rewards. The new employee allegedly desired responsibility and recognition. Again, this is theory but with practical consequences. The recruitment focus turned to a combination of acquired SKAs (skills, knowledge, and abilities) and potential for the future. The educational focus turned to a combination of training and learning. That regular universities developed advanced programs for professional categories is a feature of only the past six decades. Motivation enhancement beyond financial compensation was not really an issue before World War II. After that war, though, a variety of minor structural modifications to the work situation (for instance, job rotation, work modules, project and task forces) were introduced. From the 1970s on, work conditions as well as the manager-employee relation became the object of major structural modifications (job enrichment, shorter workweek, flex-time, employee empowerment, TQM, MBO, and so forth). Together, temporary or more lasting minor and major structural modifications have served to enhance morale and to strengthen loyalty to the organization.

Legislative activity reflects the fact that the employee is not a “job” or a “position” but an individual who needs to be protected from unsavory work conditions and whose constitutional rights have to be observed. The American Presidents Kennedy, Nixon, and Clinton have used the executive order (i.e., regulatory law) to slowly expand public employees' rights to collective bargaining. As important as these regulatory actions are, all the legislation passed by the American Congress aims at protecting the constitutional rights of the employee both in the public and the private sectors. Many of these acts are concerned with protecting people against discrimination (on the bases of gender, race, age, physical ability, sexual orientation, and so forth). The oldest act of that type of legislation was the Equal Pay Act of 1963. This act and many since emphasize that as citizens we are all equal not only in the eyes of the law but in terms of opportunity in employment. The impact that this had on personnel management is clear. Workforce diversity is no longer only an issue of professional background (employees with different educational backgrounds) but one of representative bureaucracy (at least in terms of the composition of the population). The personnel manager will proactively develop plans to hire people who are labeled a minority through Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act (affirmative action, equal employment opportunity). Managing workforce diversity is considered one of the greatest challenges of modern HRM. Increased sensitivity to the demographic makeup of society is, prior to recruitment, visible in various ways. Equal employment opportunity and affirmative action programs assure some proactive enhancement of representativeness. The Professional and Administrative Career Examination (PACE) system that was used between 1974 and 1982 was terminated because of cultural bias. Also, some public organizations (such as the U.S. Air Force) no longer require photographs of applicants, and they have taken out the part on the application form where the applicant had to indicate race. And of course, during employment the protection of employee rights and sensitivity to diversity is apparent in the sexual harassment case law, the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978, and the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993.

The Societal Environment: Public Pressure for Change

By way of generalization one could argue that changes in organizations at large and in personnel management as organizational function specifically have been first and foremost motivated by the dominant theory on political-administrative relations. Another generalization could be that changes in work conditions and manager-employee relations have been first and foremost motivated by an individual focus on HRM and by pressure from the societal environment (Section 5).

Before the Second World War the societal environment was not really relevant in the perception of public managers. Representativeness was a nonissue. You simply hired the best person for the job. More important, workforce homogeneity required little sensitivity to representativeness. Given that the organization had to do the most efficient job possible, employee needs were subordinate to that end. Morale and ethics were interpreted at the level of bureaucratic responsibility, or what John Rohr (1989, p. 60 and following pages) called the low road (codes of ethics, ethics legislation). The organization did not care too much for outside pressure such as from labor unions. The freedom of association was not considered applicable to those who worked in the public sector. The focus on collective bargaining was thus that of a pluralist (conflictual) model. And certainly in the public sector wages, hours, and fringe benefits were nonnegotiable, for that fell to the authority of the Civil Service Commission. And finally, the public generally had some respect for people in the public service, possibly more so in Western Europe than in the United States. Certainly in Western Europe the idea that working for the government was a privilege was strong until the late 1950s. Beyond the major reforms governments instigated around the turn of the twentieth century, the public at large did not appear to have much interest in the structure and functioning of their government.

It becomes repetitive, but all this changed from the 1960s on. Public opinion strongly desired a more representative bureaucracy. In society at large the focus on morale and ethics has come to include the level of operational ethics (also known as procedural ethics or professional ethics) that combined the earlier sense of bureaucratic responsibility with an appreciation of “third-level ethics,” to use Bruce's phrase. The consequence for the employee and for personnel management is that it elevates the “employing, empowering, supervising, retaining and terminating of workers to the realm of ethical discussion.” (Bruce, 1995, p. 115) We could call this the ethics of managerial or operational responsibility.

Public opinion since the late 1970s also desired a smaller government. In general, some cutbacks have been achieved, especially at the level of blue-collar jobs and middle-management positions. Privatization and contracting out have resulted in a more bureaucratized workforce at the federal/national levels of government in the sense that the relative number of white-collar workers has increased. The consequence of this in terms of personnel management is that collective bargaining is more perceived in light of a unitary (consensual) model. Disagreements between management and employees can be solved through one-on-one interaction or through mediation. Furthermore, the higher white-collar employee in government is generally well educated and able to take care of himself. At higher positions financial and other types of compensation are negotiable up to a point, something that would have been inconceivable even 30 years ago. Also, developments of public sector pay generally lag behind those in the private sector, not to mention the fact that public sector pay for higher-educated and experienced professionals is on average lower than in the private sector. After all, public sector pay is taxpayers' money. Hence, in this sense too, the pressure of the environment has consequences for personnel management. Finally, government jobs are no longer fulfilled on the grounds of civic duty or privilege. Rather, public sector jobs are a right, based on merit (the best person for the job), on notions of equality of opportunity, as reparation for past injustice, and/or of “patronage” (certainly for political appointees).

As in the previous section, we suffer from lack of systematic, comparative information about the development of personnel management in developing countries. Furthermore, even though the description in this section is based on the American development, we do think that by and large comparable developments can be found in the rest of the developed world. As for developing countries, many bi- and multilateral donors increasingly consider HRM reforms as vital to successful change.

Concluding Comments

Bureaucracies have become very important everywhere to the overall development of society, and its career civil servants have become by far the largest category of public servants in the developed world, especially at the national level. We have seen that in some developing countries, laborers are still quite important, but we cannot say much about the composition of the career civil service in the developing world for lack of systematic research. In developed countries the role and position of government in society has changed enormously in the past 200-plus years, and this left its mark on those who work in government. First, the overall size of the public workforce increased significantly. Second, to assure professionalism within the career civil service, politics and administration came to be regarded as separate functions (at least in a legal sense). That in practice, in a sociological perspective, they are intertwined has not influenced appointments in the career civil service as a whole. Only at the higher and highest career civil service ranks have appointments become politicized, although to varying degree. Third, professionalism in the career civil service has also been enhanced by means of standardizing the personnel function as much as possible (job description, job interviews, rules for promotion, performance management and measurement, and so on). All this has, fourth, resulted in a much less corrupt career civil service than ever before. How this vast personnel system functions internally is important to personnel or human resource managers; what it actually does externally is important and much more visible to the population at large. While Chapters 2 to 8 provided a comparative perspective into the contemporary structure of government (territory, bureaucracy, state, political system, civil service), Chapters 9 to 12 will show the range of different activities and policies governments today are involved in.