APPENDIX TWO

MOTIVES, TYPES AND THEORIES, METHODS FOR, AND CHALLENGES OF COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVES

Visiting another country/culture is quite like going to the zoo and looking at strange animals. People are delighted seeing something that is different from what they see in their own environment: They marvel at the different clothes and textile coloring, the taste of different foods, experiencing different habits and customs, but in the end, they can leave and just ponder the novelty of it all with curiosity satisfied. What is acquired when visiting another region or country is ordinary knowledge that often confirms existing stereotypes. That is, what people see, taste, and especially what they experience sooner confirms what they believe to know rather than elucidates and nuances, and perhaps even changes what they know. Visiting another country and its culture is also quite like watching TV. What people see and experience is not part of the day-to-day reality in which they live, it is just an escape from that reality. In other words, ordinary knowledge is not challenged or put to the test by visiting or watching some other place. Visiting another region or country or watching a program about it on TV inevitably invokes comparative observations, but these merely serve to satisfy a temporary, rather fleeting, curiosity.

Since Ancient Greece some people wrote down and published their travel impressions, which effort represents a more systematic type of reflection. Some of these travel diaries have proved invaluable for the formulation of ideas about politics (for instance, Thomas Jefferson Travels: Selected Writings, 1784–1789), about foreign societies and polities (for instance, Ibn Khald![]() n's Muqadimmah, 1366, or Alexis de Tocqueville's Journey to America, 1831–1832), and about the nature of the physical and biological world (think of Charles Darwin's The Voyage of the Beagle, 1839). Especially Darwin's observations are important in the context of this book not so much because they led him to redefine human understanding about the development of life on earth, but because his work is testimony to the benefit of a comparative perspective for organized knowledge.

n's Muqadimmah, 1366, or Alexis de Tocqueville's Journey to America, 1831–1832), and about the nature of the physical and biological world (think of Charles Darwin's The Voyage of the Beagle, 1839). Especially Darwin's observations are important in the context of this book not so much because they led him to redefine human understanding about the development of life on earth, but because his work is testimony to the benefit of a comparative perspective for organized knowledge.

What distinguishes ordinary knowledge from organized knowledge is that the latter is the product of scholarship. The knowledge created by scholarship is grounded in long, advanced, and systematic study of (aspects of) natural and social reality in the hope of expanding human understanding of that reality. Scholars are the source of organized, systematic knowledge, best captured in the German Wissenschaft and comparable concepts in the other Germanic languages (Raadschelders, 2011b, pp. 40–41). In the Romanic languages the similar concept is that of, for instance, the French science and still used in this pre-eighteenth-century meaning in all the Mediterranean countries. The Anglo-American concept of “science” refers to a more narrow understanding of organized knowledge in use since the eighteenth century, namely as knowledge that is created through the application of the scientific method.1

Comparative studies are one avenue through which knowledge is created, but as an approach it only exists in the social sciences and the humanities. It is not necessary in the natural sciences. Gravity and magnetism operate and are present in every time and context. Also, the language in which natural scientists communicate with one another is highly formalized (think of the periodic table of elements) and mathematized, and they do not need to speak the language of a colleague from another country. Scholars in the social sciences and the humanities do not have the luxury of a formal language, but they increasingly communicate in English, the lingua franca of the contemporary academic world. But beyond the question of the formal language in which scholars of the social sciences and the humanities communicate stands the aspiration to understand the meaning of our social and human life. Perhaps the utmost challenge in academic comparative efforts is to learn from other people/cultures/societies a generic truth about human nature and social life, beyond the language and other symptoms of one case. Comparative studies exist precisely because very different nations and cultures also share very similar policy problems and public administration challenges. In this appendix we explore several motives for comparative research. It is up to readers to decide which they find the most important. Next, what types of comparative research can be distinguished? Are there theories that concern comparative government as a whole? What methods are available to scholars interested in comparative knowledge? Finally, what are the challenges of pursuing comparative perspectives?

Motives for Comparison

Appendix 1 opened with the remark that people compare continuously in their day-to-day lives, whether they want to or not. Comparison is central to human behavior as a means to stratify, thus serving to establish a pecking order. Scholars use comparison for three, perhaps four reasons.

The most obvious and first set is theoretical and methodological motives. In the 1940s Dahl could still argue that comparative research was necessary in the search for at least general principles of wide validity (Dahl, 1947, p. 1). Although that motive of comparative research is mentioned less and less as the main goal, one could say that comparison is pursued in order to search for generalizations. In that sense Dahl's conclusion is still relevant:

No science of public administration is possible unless: [ . . . ] (3) there is a body of comparative studies from which it may be possible to discover principles and generalities that transcend national boundaries and peculiar historical experiences. (Dahl, 1947, p. 11)

Note how carefully Dahl phrases his objective. A science (narrowly defined) of public administration cannot be possible without comparison, but comparison only “may” lead to the discovery of principles and generalities. In other words, there is no guarantee. The authors of this book agree that understanding the role and position of contemporary government in society is no longer possible without a comparative perspective. Societies and their governments are more intertwined than ever before. Whether a science of public administration is possible is not the object of this volume, but we do think that comparative knowledge will help people to better understand the world in which they live. The origins and development of government as we know it, and of policies it pursues, have been traced in the various chapters throughout this book. We will find that some features of the structure and functioning of contemporary government transcend national boundaries, while other characteristics bear the traces of “peculiar historical experiences.” In other words, comparison is an analytical tool that may help us understand the potential and boundaries of knowledge dissemination among nations and administrative agencies.

It is not likely that social scientists will find universal laws regarding government, let alone for social phenomena in general, and so grand theory is more than ever a remote dream in the social sciences. What is possible through comparative studies is the development of, as Robert Merton called it, “middle-range theory,” a more modest objective that hopes for generalizations on the basis of empirical investigations of a specific phenomenon or of a related set of phenomena. Middle-range theories “lie between the minor but necessary working hypotheses evolved in abundance during day-to-day research and the all-inclusive systematic efforts to develop a unified theory that will explain all the observed uniformities of social behavior, social organization, and social change.” Social science theories since the Second World War are of the middle range, and comparison helps in the effort to develop and test theory.

A second set of motives for comparative research is utilitarian. Comparative research helps practitioners and scholars learn about how more or less comparable institutions have dealt differently with the same problem. Many are the instances where particular actions (organizational and territorial divisions, legislation, and so on) have been copied by one country from another (see Chapter 3). In Appendix 1 several examples were mentioned of civil servants traveling to other countries in hopes of learning from best practices elsewhere and assessing the extent to which these could be adopted in their own country. These exchanges of experiences and possible imitation are voluntary, but just as frequent have been the instances throughout history where the adoption and imitation of administrative practices have been imposed by a conqueror or colonizer or strongly advised by international actors such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank (see: Raadschelders and Bemelmans-Videc, 2015, p. 339; more on imitation in colonial administration in Chapters 3 and 4).

A possible third reason could be the legitimizing or sobering-up motive of comparative studies. This reason is closely related to utilitarian reasons. When citizens are asked whether they would desire to live in another country of their choice, most respond to have no such desire. The implicit and simple comparison, based on information from media outlets, generally comes out in favor of one's own country. Whereas the common psychological explanation of resistance to change (Watson, 1971) is applicable here, another explanation is the social construction of life for each and every one us, based on values, rules, and axioms that work in one society and not necessarily in others. This social construction of reality begins in one's early days of childhood and determines our mature life. The notion of “American exceptionalism” is a good example of an implicit comparison that serves to legitimize one's country. Initially the term referred to the United States being the first new nation (Lipset, 1979) as it was built upon a creed of liberty, egalitarianism, individualism, laissez-faire, and populism. In recent decades, though, its meaning appears to have narrowed to being a country beloved of God and in which people have high self-esteem. One commentator recently noted that perhaps “American narcissism” captures better what characterizes the United States today (Cohen, 2011). Cohen's commentary provides various comparative examples, as does Derek Bok's extensive analysis of several problems in the United States in comparison to other countries in his The State of the Nation (1996). In fact, both these authors use comparison to help sober up this inward-looking appreciation of all things American and show how in many respects (health care, incarceration, education levels, paternal leave, child support, poor relief, and so on and so forth) citizens in other countries are faring much better. We need to keep in mind, though, that differences in public policies are related to differences in political culture and institutional settings (Krause and Smith, 2015, p. 245). With that in mind, it is far more difficult to judge a domestic policy by the standards and contexts of other countries.

This leads into the fourth and possibly most important motive for pursuing understanding based on comparative inquiry: cultural motives. Comparative research will lead to both more appreciation as well as more founded criticism of the society in and political-administrative system with which one grew up. Comparison provides an antidote against the limited views that exist if one has only studied the national state and administrative system. Indeed, comparison serves to “counteract tendencies toward parochialism. . . .” (Fitzpatrick and others, 2011, p. 821). It will develop awareness that one system of government is not necessarily better than another, and that a comparison of whole countries makes little sense. Also, when people are open minded, comparison may very well lead to respect for and patience with how “things” are done elsewhere. Comparison, then, serves as a civilizing force. Comparative public administration is an important part of the administrative sciences, although it is less pursued than we would expect (Fitzpatrick and others, 2011).

The theoretical and methodological motives for comparison are often grounded in the notion of a value-free and morally neutral social science that strives for objectivity. The utilitarian motive is also based upon the idea that practices from elsewhere can be adopted in one's own country, although this generally does not happen without some degree of adaptation. The legitimizing or sobering-up motive moves us even further away from value and moral neutrality. We compare to establish rankings, and these in themselves are value laden. The most removed from the desire for objectivity is any comparison pursued to civilize, educate people. This motive for pursuing comparative understanding can only show the relativity of values, customs, and habits.

That said, comparative knowledge gained from articles and books, and developed in a classroom setting, is certainly a start, but is no substitute for “living the comparative perspective;” that is, spending a considerable amount of time in another country. Next to the inclusion of comparative perspectives in every public administration course, students should be encouraged to participate in international exchange programs.

Theories, Methods, and Types of Comparison

Above we noted that comparison can be pursued for a variety of reasons. In practice this might often be a mix of those mentioned. Whatever it is that practitioners and/or scholars compare, they do so in the context of a theoretical framework and a specific type of interest. The object of this section is to briefly highlight these theories and types of comparison.

Approaches to and Theories in Comparative Public Administration and Governance

While the natural sciences enjoy the pleasure of grand or (somewhat) unifying theories, the social sciences have many middle-range theories and no grand theory. A grand or unifying theory addresses a specific set of related natural phenomena, and any of the specializations within a discipline will operate within the framework of the grand or unifying theory. This is also referred to as nomological framework (d'Andrade, 1986) or paradigm (Kuhn, 1996). If there is a candidate for grand theory in the social sciences at large it must be that of structural-functionalism as developed by Talcott Parsons, who held that society as a whole is a function of its constituent elements. He tried to develop a general theory of society known as action theory. Parsons's approach would soon be regarded as too generalized and abstract, and Merton's more limited middle-range theory approach basically won the day.

The social sciences have many middle-range theories or second-order formal objects. The concept of formal object originates with Kant and refers to a set of theories and concepts that circumscribe the study of a material object. The material object—that is, reality as is—can only be accessed through rationality on the one hand and sensory (sight, hearing, touch, taste, smell) perception on the other hand. The natural sciences have formal objects that entirely encompass their discipline; for instance, the Standard Model in physics, the periodic table of elements in chemistry, and evolution theory in biology. This is then a paradigm or first-order formal object, because it demarcates a discipline as a whole. In the social sciences only second-order formal objects2 (that is, middle-range theory) can be identified since sets of theories and concepts concern at best specializations and/or specific topics within a discipline or study.

The material object of the study of public administration is government in its manifold relations with society. To date, there is no set of concepts and theories that clearly differentiate the study from other studies and disciplines. Instead, public administration scholars draw upon whatever knowledge sources (i.e., disciplines, but also experiential knowledge in governmental agencies, etc.) available without being beholden to any of them. Public administration is an umbrella study, the natural home where knowledge about government-in-society, as generated in many other disciplines and studies, is connected. The study of public administration has many second-order formal objects mainly situated in its various specializations such as human resource management, policy evaluation, organization theory, intergovernmental relations, budgeting and finance, and so on and so forth. Comparative government or administration could be regarded as a specialization in the study, but could also be seen as an approach relevant to any specialization in the study. With regard to the latter, and by way of example, there is a comparative study of taxation (Peters, 1991), comparative reflections upon human resource management (for instance, Beardwell and Holden, 1997), and several studies of comparative public bureaucracies (Peters, 1988; Farazmand, 1991; Page, 1992; Tummala, 2005). We prefer to consider comparative administration as an approach that enriches the understanding of the phenomena studied in the study's various specializations.

Theories of and/or relevant to comparative public administration and governance can be mapped in two ways. First, they can be characterized in terms of their dominant approach or method; second, they can be listed in terms of specific research object. With regard to dominant approach or method Hague and others (1992) distinguished between case studies, statistical analysis, and focused comparison. Lijphart listed the comparative method next to the experimental, the statistical, and the case study methods (1971, p. 682).

We can also look at two examples of conceptual maps of political science that are relevant to public administration. Gabriel Almond argued in the early 1980s that political science had split along methodological and ideological dimensions. In terms of methodology he distinguished between those who favored a “hard science” approach (that is, “quants,” mathematical modeling, econometrics, game and voting theories) and those who advocated a “soft,” more descriptive approach. With regard to ideology he contrasted left- and right-wing scholarship. He characterized left-wing scholarship as reliant most on a soft approach, using thick description and political-philosophical studies. Examples include critical theory and authors such as Johan Galtung and Emmanuel Wallerstein. Right-wing scholarship is more neoconservative and there we can find on the hard side someone like Herbert Simon, and on the soft dimension someone like Max Weber.

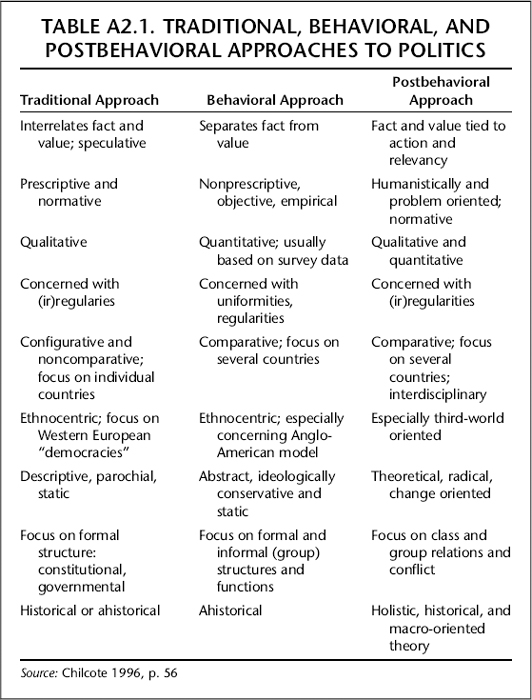

Another example is Chilcote's listing of three approaches to comparative politics that, like Almond's matrix, only concerns the twentieth century (see Table A2.1). The traditional approach seems to fit best the “stamps-flags-coins” approach mentioned in Appendix 1, but goes beyond in view of its prescriptive and normative aspirations. The attention for formal institutional arrangements is reminiscent of the nineteenth-century focus on law. Before the Second World War most comparative studies focused on countries in the Western world, but unlike what Chilcote claims, the focus was on both individual countries and several countries. Chilcote's behavioral approach compares best with the top row in Almond's matrix and befits the positivist stream in the social sciences. Interestingly, the postbehavioral column aligns best with the bottom row in Almond's matrix. The bottom left corner in Almond's matrix is echoed in Chilcote's change-oriented scholarship that operates upon notions of class conflict and relations. The bottom right corner of Almond's matrix returns in Chilcote's characterization as that postbehavioral research is holistic, historical, and macro-oriented. This suggests that Max Weber' s type of work is back in fashion.

A second way that theories relevant to and/or in comparative administration can be mapped is by their subject matter. Thus, there are theories about the emergence of the early state (Chapter 2), about the dissemination of the Western state system across the globe (Chapter 3), about state making and nation building (Chapter 4), about intergovernmental relations (Chapter 5), about bureaucracy (Chapter 6), about organization and management (Chapter 7), and about political-administrative relations and elite theories (Chapter 8). There are also many, many theories concerning the nature of and development in specific policy areas (Chapters 9 to 12); for instance, about the development of traditional government functions (Chapter 9), taxation (Chapter 10), industrialization (Chapter 11), and welfare functions (Chapter 12). These and many other theories will be mentioned, and sometimes discussed at some length, in the various chapters listed.

There is one specific set of theories relevant to comparative government as a whole, such as stage theories. Some theories mentioned above concerning specific topics of interest to comparative research are stage theories, such as, for instance, the emergence and development of the early state, state-making and nation-building theories, and theories about the development of political-administrative relations. Other stage theories include attention for the development of the Western legal system, of civil service systems, of local government, of politics, of warfare and state organization, and of industrial capitalism (see for these, Raadschelders, 1998, pp. 79–83). When relevant to the topic of a specific chapter, these too will be briefly discussed.

Three Basic Methods of Comparison

Vital to comparative research is the determination of what we are comparing, and all of the methods can be grouped into three main categories. Two of these were first distinguished by John Stuart Mill: the method of agreement and the method of difference (1930, p. 256). Both are methods of elimination that somehow must tackle the central problem of plurality of causes and intermixture of effects (Mill, 1930, p. 285). Mill argued that sociology (and we suggest, by extension, the social sciences) cannot be a science of positive predictions, but only one of tendencies. We can never be certain how a particular cause will operate in a particular context. In his words “we can seldom know, even approximately, all the agencies which may coexist with it, and still less calculate the collective result of so many combined elements.” (Mill, 1930, p. 585) Fritz Scharpf captured the problem of comparative research in similar terms: “For comparative policy research, this means that the potential number of different constellations of situational and institutional factors will be extremely large—so large, in fact, that it is rather unlikely that exactly the same factor combination will appear in many empirical cases.” (1997, p. 23; as quoted in Ostrom, 2005, p. 10) The third category is the so-called configurational method. We will discuss these three below. Before doing so one remark needs to be made, and that is that we have to be aware of the challenge of selecting the level and unit of analysis: people, professionals, citizens, policies, institutions, agencies, structure, nations, municipalities, etc. In this book we did not make that choice and instead opted to address the world of government in its entirety.

Many studies in public administration suffer from what Lijphart (1971, p. 686) calls the “many variables, small N” problem. The research question at hand results in a study in which just a few cases have to be examined on many aspects, so that afterward no conclusion can be drawn on (causal) relationships between those variables. When for example two governmental agencies differ in their growth and also in their organizational form, size, policy field, budget, and clientele, it is not possible in this design to attribute the growth difference to any of the other variables. To solve this problem, one should either increase the number of cases as much as possible or carefully choose a strategy to handle the variation. It is often not possible to increase the number of cases due to restrictions in time, money, and the availability of information. With respect to the strategy concerning the variation in relevant aspects, two basic designs can be distinguished: the most different systems design (MDSD) and the most similar systems design (MSSD) (for instance, Przeworski and Teune, 1970; Lijphart, 1975; Frendreis, 1983).

In a nutshell, the idea behind these two methods is to either create as much difference between cases as possible apart from a few well-chosen variables, or reduce such differences as far as possible except for a few variables. In the first strategy (MDSD) one should look for similarities between cases as these provide clues concerning relations between variables, while in the latter (MSSD) these clues can be found in the differences between cases: “The logic of each design is to isolate relationships between variables by eliminating ‘nuisance’ or extraneous variables, or in causal terms, to isolate causal factors by eliminating competing variables as possible causes.” (Frendreis, 1983, p. 260) In an MSSD study, the researcher maximizes the number of characteristics that the systems (cases) have in common and tries to minimize the number of characteristics on which these systems differ. In other words, systems are selected that are similar on as many independent variables as possible, with the exception of the phenomenon that is studied (either a dependent variable Y or a dependent relationship). The logic behind such a design is that while the cases are different regarding the dependent variable but are similar on any of the independent variables, differences in the dependent variable cannot be attributed to any of these controlled variables. It is slightly confusing, but the MSSD design is also known as Mill's (indirect) method of difference (Ragin, 1989, especially Chapter 3).

In an MDSD, cases are selected that do not differ in the phenomenon under examination (that is, the dependent variable Y), but are as different as possible on all other characteristics. As possible causes for the dependent variable, all those variables are eliminated on which the cases differ. Frendreis cites Przeworski and Teune (1970, p. 35) to clarify the logic behind it: “If rates of suicide are the same among the Zuni, the Swedes, and the Russians, those factors that distinguish these three societies are irrelevant for the explanation of suicide.” The MDSD design is also referred to as Mill's method of agreement (Ragin, 1989, Chapter 3).

For a comparative study, the researcher can make a deliberate choice for either the MSSD or the MDSD. Several considerations play a part in this choice, of which the research question at hand and thus the type of study is the most important. For an explorative study it is most fruitful when cases differ in the central phenomenon selected for study (as a dependent variable or a dependent relationship). Any concomitant variation in some independent variable could be an indication for a causal relationship, thereby providing an interesting starting point for further research. To be able to select such interesting variables, the differences between cases in the independent variables should be minimized. The basic strategy would thus be one in which similar systems are compared, hence an MSSD. (To be sure, covariation between two variables is never a proof for a causal relationship, only a necessary condition, and in an exploratory context merely an indication.) Should there be no variation in the central phenomenon, the search for concomitant variation in the set of independent variables in an exploratory study is useless.

In case of a study in which a clear hypothesis is formulated and tested, an MDSD is advisable. The hypothesis is tested in systems that are as different as possible, thereby using a test that is as severe as possible. The idea behind this is that when, for instance, it is argued that in general there is a relationship between two variables, we should check whether this relationship holds in all kinds of circumstances or systems as well as whether they hold across time. Therefore, the researcher selects cases that are the same with respect to the central phenomenon but differ in all other respects. One cannot falsify the hypothesis when the predicted relationship is found in all cases.

Other considerations that play a role in the choice between an MSSD and an MDSD are more pragmatic: Time, money, and the availability of data almost always have an influence on the research design (see the following). As an MSSD is often more flexible than an MDSD, and only a few studies are aimed at the explicit testing of a hypothesis, most researchers in one way or another choose an MSSD. The prime example is comparative research within a so-called “family of nations” approach (see Appendix 1). In a sense one could call MSSD and MDSD methodological ideal-types, used to clarify the logic behind comparative research. Moreover, the considerations mentioned so far are relevant in situations with few cases. When we have a large N, a quantitative-statistical approach is possible and advisable. Controlling for variations in either the independent or the dependent variables is done using techniques like multivariate regression analysis.

The configurative approach is most fitting for single-case or small-N comparative research. As it has been briefly characterized in Appendix 1 (see footnote 1), this need not be further elaborated in this chapter.

Types of Comparisons

There is yet another way that comparative research can be conceptualized and that is by looking at what is being compared, and how is the comparison made.

What is being compared? What we compare are seldom individuals and individual behaviors. We compare sociopolitico-economic-cultural systems or components of these. In the literature, comparative politics (political science), comparative public policy (both in political science and in public administration), and comparative government (mainly on bureaucracy and civil service systems and generally in the study of public administration) are often separated. As noted in Chapter 1, we find this an unfortunate circumstance since any separation of politics, policy, and bureaucracy (including management) only serves analytics and is, as far as understanding and describing reality are concerned, artificial and not very useful to practitioners who make policy in a bureaucratic organization that is embedded in a political system. That said, we do not seek to identify what is being compared on the basis of these three substantive and organizationally defined distinctions, but on four solely substantive differences.

These four substantive foci of comparative research have been highlighted by Peters who has distinguished between, in this order, cross-national, cross-time, cross-level, and cross-policy comparisons (1988, pp. 3–7). Each of these will be briefly discussed but in the order of their emergence in the study of public administration.

Cross-national research has dominated the study since the beginning and still does. It often includes what Heady called the classic systems: France, Germany, Great Britain, the United States, and (sometimes) Japan and Russia (2001, p. 89 and following pages). The politico-administrative systems of the first three countries have influenced other systems throughout the world through occupation, diffusion, and colonization (for more detail see Chapter 4 especially). Since Macridis published his study (1955) many more comparative studies have seen the light of day (Page, 1990, p. 440). However, leading comparativists such as Heady (1990, p. 29), Page (1990, p. 445), and Rose (2001, p. 453) have demonstrated that three-quarters of the cross-national journal articles really concern one country only. The number of comparative books is by far larger (Page, 1990, p. 445). Cross-national research will remain an important element in comparative research, especially in an internationalizing and globalizing world. Many policy problems have developed cross-national (or, perhaps better, international) proportions, in the sense that they cannot be solved by individual governments. Obvious examples are pollution and environmental policies, global warming, trade and currency, and so on (Rose, 1991, p. 461).

Cross-level analysis did not draw attention until the 1980s although various researchers repeatedly lamented this (Ashford, 1975, p. 90). Attention to it mounted in the context of increasing interdependencies between central and local governments (Dente and Kjellberg, 1988; Page, 1991; Page and Goldsmith, 1987; Rhodes and Wright, 1987; Toonen, 1987) and between national governments (including sometimes subnational governments) and supranational organizations (Toonen, 1990). Cross-level research also includes comparative cross-national studies of subnational government at the regional (for instance, Bullmann, 1994; Jones and Keating, 1995) and at the local levels (for instance, Hesse, 1990/91; Denters and Rose, 2005; Kuhlmann and Bogumil, 2007).

Much cross-time research can of course be found in the historical discipline, where researchers appear to favor the medieval and early modern periods. Cross-time analysis in public administration appeared to be on the rise from the second half of the 1980s onward (Raadschelders, 1993, 1994, 1997, 1998, 2010) and is mainly focused on the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. An excellent example of cross-time studies limited to the modern period is the Jahrbuch für Europäische Verwaltungsgeschichte that was published between 1989 and 2008 by publisher Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft in Baden-Baden. Each of the 20 volumes was dedicated to one specific topic of interest to historians, legal historians, political scientists, and public administrationists. This period has immediate relevance for understanding contemporary government, since it was from the French Revolution onward that the foundations for modern government were created (for more see Chapters 3 and 4). The idea that historical developments ought to be analyzed not only to understand current structure and functioning of administration but also to know the range within which solutions to problems can be pursued is captured in the fashionable concept of path-dependency (Krasner, 1984, 1988; also Raadschelders, 1998; Kay, 2005, Chapter 3, 2006).

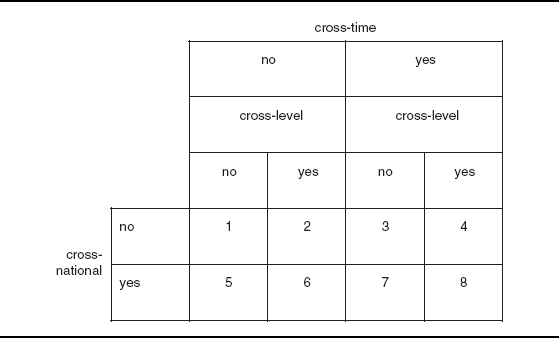

Finally, cross-policy comparison gained momentum in the context of the crisis of the welfare state and is therefore dominated by attention for policies characteristic of the welfare state (health, education, employment, social insurance, and so on; see, Ashford, 1992; Fried, 1975; Flora and Heidenheimer, 1990; Goodin and others, 1999). However, this type of comparison is of a somewhat different nature than the other three, as it does not so much characterize the nature of the comparison but rather the content of it. We therefore adapt Peters's classification. In our view, a study can be characterized on three dimensions of comparison: cross-national, cross-level, cross-time. Each dimension can be seen as a question: Is this study cross-national, is it cross-level, is it cross-time? Combined, these result in eight main types of comparison (Figure A2.1).

In a type 1 study the research concerns one moment, one level, and one case. An example would be a comparison of the public expenditures on transport with those of public education. Depending on the subject, it might also be a study that has no explicit comparative aim at all: The classical descriptive case-study might serve as an example. The other extreme is type 8. This would be rather complicated research in which all three classes of comparison can be found. This may be easier to do for a study of the comparative approach in public administration in general (and of which we believe this book is an example) than for an empirical work. With respect to the fourth category of Peters (cross-policy comparison), one could say that in the studies of public administration and political science, this is a dominant group of studies, but all cross-policy studies can be classified in terms of what is compared in one or more of the eight types listed in Figure A2.1. This book provides cross-national, cross-level, cross-time, and cross-policy comparisons.

FIGURE A2.1. MAIN TYPES OF COMPARISON

How is comparison pursued? Classifications of how comparisons are conducted are much less noticed. In an interesting article Skocpol and Somers (1980) distinguished among three types (see also Collier, 1991, pp. 11–12). In comparative research as a parallel demonstration of theory the researcher uses existing theory for new cases. It thus serves as an illustration of such a theory and does not validate theory. The example they mention is Eisenstadt's 1963 study of political systems over time. Comparative research can also be pursued to illustrate the unique features of each system. If that is the case, then the researcher is contrasting contexts. This type of analysis, however, does not lead to development of theory. The example given by Skocpol and Somers is Bendix's 1964 study of nation building. The third type they labeled macrocausal analysis. In this case the aim is to generate and test hypotheses through systematic examination of covariation among cases. The prime example, again according to Skocpol and Somers, of such a study is Barrington Moore's work on democracy and dictatorship (1966).

Challenges of Comparative Research

Some argue that comparative research is impossible since every country has its cultural idiosyncracies. In the view of the pessimist a comparative analysis is at best superficial, and that meaningful comparisons are not possible because of differences in how government functions in each country. However, it is exactly because those differences in functioning “play out” in the context of a structure that is fairly similar (see Chapters 4 to 8 on this) that advocates of comparative research argue that ample attention should be given to how the administrative heritage of a country influences government organization and functioning today (Heady, 2001, p. 153). Both groups of scholars agree that we need to be aware of problems of comparative research, and these can be grouped in four main types:

- conceptual, linguistic, and semantic problems;

- theoretical and methodological problems;

- research technical problems; and

- application problems.

We start with concepts, because neither problems of theory, model, or method, on the one hand, nor mere technical and application problems, on the other hand, can be discussed and developed without some clarity about what we investigate. This is particularly important in comparative perspectives and studies.

Conceptual, Linguistic, and Semantic Problems

In daily experience people tend to translate a word into another language without much thought about whether the actual meaning of a concept transfers as easily from one language to another. What appears trivial in day-to-day context turns out to be a trying test in research. Administrative scientists are faced with a trilemma of problems (Rutgers, 1994, 1996). First, administrative science is written in numerous natural languages. There is no equivalent for the English concept of “policy” in German, French, or Dutch. Second, administrative science deals with various cultures of governance. What appears to be one concept may hide various meanings. “Federalism” is an obvious example. In Germany federalism is mainly regarded as an administrative technique, while in France it is associated with the supra-nationalism of the European Union and sooner perceived as a threat to the national, unitary state. In the United States federalism is equated with centralism, where the federal, national state is positioned as overbearing vis-à-vis the states of the union. A civil servant in Great Britain is (supposedly) more of a generalist who is part of a merry-go-round career pattern, while in France and Germany they are specialists with fixed career paths. And finally, administrative science deals with various academic lingos. Countries may use different concepts for essentially the same phenomenon. Thus “decentralization” (as used on the European continent and North America) and “devolution” (as used in the United Kingdom) are synonymous in content. Another aspect to this phenomenon of different academic lingos is related to the fact that administrative science seeks to integrate knowledge and insights from various disciplines with respect to public institutions. The general conclusion from these three problems is that the administrative sciences (and the social sciences in general) lack a universal language, that we have to be aware of possible national biases in the theoretical framework developed for comparative research projects, and that we have to be aware of possible disciplinary biases in comparative research.

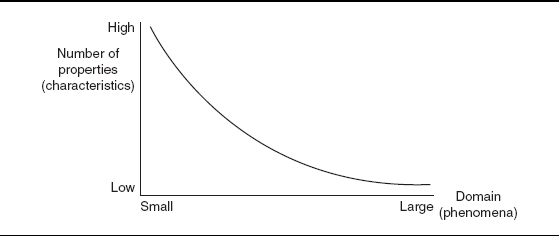

A different way of understanding the conceptual, linguistic, and semantic problems of comparative research is hidden in the distinction between the intension and extension of concepts (Sartori, 1970, p. 1041; Collier, 1991, p. 18; Nuchelmans, 1974, pp. 22 and 33–34). The intension of a concept (connotation) concerns the collection of properties constituting a concept or, in more popular terms, the contents. The extension of a concept (denotation) concerns the class of phenomena (i.e., totality of objects) to which a concept applies, hence the scope, the range of cases referred to.

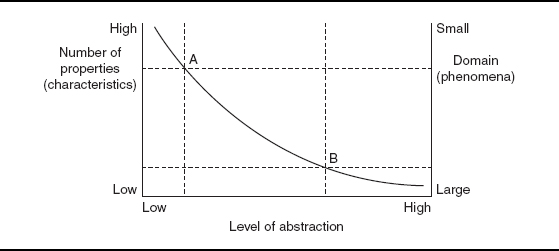

This may be illustrated by the chief executive and the president. Both denote the same office or person, but they connote different characteristics. The classic example in semantics is “the morning star” and “the evening star.” Both denote the planet Venus but have different connotations as they are applicable to different occasions (i.e., a phenomenon visible in the morning or in the evening) (Rutgers, 1996, p. 15). According to Sartori one can climb the level of abstraction in two ways. One can broaden the extension of a concept by reducing its properties (reducing the connotation) so that a more “general” concept is created without loss of precision. One can also increase the extension of a concept without diminishing the intension. This he labeled conceptual stretching. To clarify this, consider Figure A2.2 in which the relationship between the number of properties or characteristics and the domain is reflected.

FIGURE A2.2. NUMBER OF PROPERTIES AND PHENOMENA

FIGURE A2.3. LEVEL OF ABSTRACTION

The more characteristics are specified, the fewer cases it applies to. Conversely, the larger the domain (that is, set of objects), the fewer the number of characteristics. If, for example, we define politics in the Lasswellian sense as “who gets what, when and how,” we specify few characteristics, and hence this refers to a large set of phenomena. Should we, however, formulate a more strict concept, say: “Politics is the formal decision making in any authorized representative body such as a parliament or city council,” then this refers to a smaller set of objects as the number of characteristics is larger. In fact, the set of objects under the latter definition is a subset of the domain under the former (Figure A2.3). The relationship between the number of properties, the number of phenomena and the level of abstraction is depicted. The curve shows that a large number of properties corresponds to a rather concrete level of analysis and a small number of phenomena. Point A reflects such a definition. Vice versa, a large set of phenomena implies a high level of abstraction and a small number of properties. Point B is a definition of this type.

The first route that Sartori describes to climb (or descend) the ladder of abstraction basically means shifting positions on this curve. It makes one aware of a choice that must be made. The inappropriateness of the second strategy can now easily be seen: One cannot seek a higher level of abstraction, and thus a larger class of phenomena, while simultaneously leaving the number of phenomena unchanged. You can't make an omelet without breaking a few eggs, to put it domestically. When the extension of a concept is enlarged by reducing the number of properties (that is, characteristics) so that more phenomena can be included in a concept, the quality of the concept as an analytical tool is preserved. When, however, the extension of a concept is stretched without reducing the number of characteristics, one basically uses a concept as a garbage can. In that case the analytical qualities of the concept have been sacrificed. It will be clear that this is not acceptable from a scholarly point of view.

As is to be expected, the risk of conceptual stretching is especially large in comparative research that seeks to encompass both Western as well as non-Western countries. Based on an accepted dichotomy in philosophy Rutgers (1994) distinguishes authentic meaning from meaning ratio of concepts. This helps us to develop a more refined understanding of linguistic problems. The authentic meaning of a concept is related to a specific time and place. We will acquire knowledge of a particular local/national problem, but we will not be able to establish whether—in the case of comparative research—our premises for various cases are of the same order. Conclusions can hardly, if at all, be generalized. When we use meaning ratio as our point of departure for comparative research, we can arrive at generalizations, since we use one framework (such as an ideal type) to interpret and compare various cases.

Theoretical and Methodological Problems

Some of the conceptual, linguistic, and semantic problems spill over into being a theoretical and methodological challenge. Above, we already noted that a civil servant is a very different concept in France, in Germany, and in the United Kingdom. We also need to pay careful attention to what can be quantified, and even whether we do need to quantify.

The Meaning of Concepts Those who argue that the intension and authentic meaning of concepts are specific concur implicitly with Kuhn's idea of incommensurability, while those who defend extension of concepts and meaning ratios might feel more comfortable with Popper's “myth of the framework.” Kuhn and Feyerabend argued that concepts and theoretical frameworks developed for empirical research of a specific case and/or in a specific place may not so easily be transferred and used in a different context. Hence, when time and context obviously must differ from case to case and from place to place, each case or place requires a theoretical framework of its own. In other words: The concepts developed in a particular theoretical framework derive their meaning from that framework, and cannot be transferred to a different theoretical framework.3 This is closely related to some of the problems discussed above.

The other position has been voiced by Karl Popper, who defended the possibility of transferring concepts from one framework to another. He labeled the idea of incommensurability as a “myth of the framework.” In comparative research it is common that concepts developed for a particular research in a particular country/culture are used in later projects. Replication is an immanent criterion for science. It is a necessity in any empirical research that seeks extension of theory, findings, and implications. This is especially the case with research that seeks to replicate findings of earlier research. Public administration researchers position themselves, usually implicitly, in the Kuhn/Popper debate. In most cases, researchers do not include a formal statement on this subject, but rather show this position by the research design that is used. Therefore, a major problem (and challenge) of many comparative studies in our study is the allocation of a reasonable number of cases (much beyond the case-study orientation of many administrative problems) and the capability to look for variance in a particular variable/concept that is equally measured by others who conducted similar previous studies on the same problem.

From this it follows that it is important to explicitly choose a key concept or set of concepts from which the comparison is pursued. The researcher should select concepts that render meaning in different cultural contexts. Choosing the ideal typical method may be helpful, in the sense that an ideal type “hovers” above (or next to) reality. The development of a theoretically meaningful classification is imperative.

Problems of Statistical Research In comparative government research, experiments such as those conducted in, for instance, cognitive psychology cannot be done. Instead “we can use the experience of other nations to provide what may be regarded as ‘natural experiments’” on the basis of a most similar systems design (Castles, 2000, p. 13). When using statistical data, comparative researchers are confronted with several challenges. The first challenge concerns the representativeness of the sample. Research in comparative government is always limited in terms of the number of cases that can be investigated. Selecting 21 cases, Castles noted that sample-representativeness was a challenge given that probabilities generally rely on much larger samples (2000, p. 18).

The second challenge involves the choice between studying one or a few variables in many cases versus multiple variables in relatively few cases. The former amounts to a reduction of the complexity of reality, but allows for modeling. The latter provides a better reflection of reality, but will not allow for modeling.

A third challenge concerns the quantity and quality of the data collected. With regard to quantity, the question always is whether a sufficient and reliable set of indicators is available. However, what determines sufficiency is open to questioning. As for quality, in view of cross-national variations in conceptualizing social phenomena (for instance, civil service, bureaucracy, corruption, and so on), it is vital that a determination is made about how comparable the data really are so as to make sure that we are not comparing apples and oranges. This problem is especially present in research that employs secondary data that are collected by someone else or some other institution. For instance, the OECD, the IMF, the UN, and various survey organizations make data collections available to researchers, but the latter do not often explore the collection rationale of the dataset. It is thus desirable to develop one's own dataset, generating primary data. In either case, the challenge of avoiding a selection bias (that is, countries selected, type of data collected) is huge (Hague and others, 1992, p. 38).

A fourth challenge concerns the choice for a cross-sectional comparison of one moment in time versus a cross-time analysis. Most quantitative-statistical research is cross sectional by nature, even when researchers present data from different moments in time. For instance, Castles (2000) analyzed data about public policy functions from 1960, 1974, and the early 1990s, claiming to illustrate change over time. However, his data represent nothing more and nothing less than three cross-sectional slices of three different moments in time. Hence, his analysis is still static and cannot capture the dynamics of social change over time. True cross-time analysis of a quantitative-statistical bend requires concepts, and thus data, that “travel” over time. This has proven to be extremely difficult. Just consider the fact that politicians as we define them nowadays, namely as elected representatives of the people, simply did not exist before the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Indeed, a distinction between politicians and career civil servants did not exist until that time. Consequently, most quantitative cross-time research is limited to the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, as is evidenced, for instance, by the annual publication of the Yearbook of European Administrative History (published between 1989–2008). Qualitative (or configurational) research is not limited to the recent past.

Frendreis (1983, pp. 258–259) also discussed the challenges of quantitative research mentioned above, but specifically notes that it is a challenge not to violate the assumption of independence of events (Galton's problem). This problem has to do with the possibilities of generalizing research findings. In nineteenth-century social science research the search for universal laws dominated. The major challenge in establishing universality is to prove that the phenomenon under investigation in two or more cases developed independently from one another. This not only means that the development in one case must not have influenced a comparable development in another case, but also that the developments in both cases do not have a common root. This challenge is known as the Problem of Galton, named after the nineteenth-century British statistician Francis Galton (and cousin of Charles Darwin) (Gnarl, 1970, p. 975; Scheuch, 1990, p. 28; Sztompka, 1990, p. 53). To date, there is possibly one development that could be considered as originating in different parts of the world (though at different times) and emerging independently, namely the pristine states in Egypt, Mesopotamia, India, China, Meso-America, and the Andes.

Moreover there is the problem of variables validity and reliability over time and across cases. Providing support to the validity of variables becomes a problem when they are measured by various tools and methods, at different times and settings. The desire of researchers to compare is frequently contaminated by the sampling of too remote variables that do not always represent the studied phenomena and/or do not measure it in the most sensitive way. Finally, the cross-sectional orientation of many comparative studies is rooted in the difficulty of collecting evidence on the same phenomena/variable from various angles and sources. This involves the problem of common-source and common-method bias that is so crucial in quality social sciences of modern times.

In the social sciences researchers have dropped the wish to identify universal laws (grand theory), and so the structural-functionalist approach lost ground considerably. They certainly have been trying to develop middle-range theory, which is the reason why so many comparative (American) studies employ a quantitative-statistical approach in order to find correlations that hint at causal probabilities. The historical-diffusions approach gains momentum, though, and is based on the idea that developments in one case may well have influenced or were influenced by developments elsewhere. In this respect it is no surprise that the study of administrative history is on the rise (Raadschelders, 1998).

Research Technical Problems

In comparison to the problems discussed earlier in this appendix, research technical issues may appear trivial in the sense that they do not concern problems of a cognitive nature. They are, however, of great importance to the success or failure of any comparative inquiry. Research technical problems involve data, time, and places.

The (in)availability of data can make or break a research project. In the social sciences data are often used that have been collected by others. Problems with that were discussed above. It may be necessary that the available data for the various cases are recalculated (which is only possible when one is familiar with the collection rationale), resulting in a more reliable and valid comparison.

A researcher who is not satisfied with the available data in secondary sources may decide to collect data from primary sources such as archival records or interviews. This, however, is very time consuming. Time is sometimes neglected as a factor in comparative analysis. The researcher may be forced to rely upon data collected earlier by others, since the available resources may not allow for data collection. In the case of cross-national research this is certainly a major problem. Therefore comparative research is often conducted by a group of scholars (a) from one country each investigating one case according to a protocol, or (b) from several countries each investigating his/her own case/country, also according to a protocol.

The advantage of the first type (sometimes called the safarimodel of comparative research) is that one can be assured that all participants in the research project understand the concepts and theories used in the same manner, since they all share the same cultural background. The advantage of the second approach is that one can be sure that each participant is highly familiar with the case/country he or she is investigating for the research project. After all, an individual researcher cannot possibly claim familiarity with all relevant literature for all countries included in the research project. A good example of this is the comparative civil service systems project that was initiated in 1990 by the Departments of Public Administration at the Universities of Leiden and Rotterdam in the Netherlands and the School for Public and Environmental Affairs, Indiana University, which resulted in seven books and several articles (for overview of this project see: Raadschelders and others, 2007, pp. 1–2; the project is briefly discussed in Heady, 2001, p. 84).

Problems of Application

So what can be done with all this comparative knowledge about governments? There are scholars who argue that globalization leads to a world where the scholarly conceptual understanding of government is converging. Indeed, contemporary challenges of government and governance are phrased in terms that are remarkably similar, whether in Australia, Brazil, Canada, India, Nigeria, Russia, or Vanuatu. Citizens, practitioners, and scholars use the same words, such as bureaucracy, decentralization, civil service, performance, corruption, and so forth, without necessarily realizing the specific meaning in their own political, social, and cultural environment. It is true that, in terms of structure, governments are quite comparable, and this is illustrated in Chapters 2 to 8. In terms of functioning they are quite different; that is, they reflect the specific historical and geographical circumstances that shaped them, as will be illustrated in Chapters 9 to 12.

If governments are more or less comparable in terms of structure and are much less comparable in terms of functioning, it follows that we cannot simply assume that a best practice in one country can be adopted somewhere else. In the 1990s one of the authors of this book addressed a group of civil servants from a newly independent state in Asia about decentralization and civil service systems. Toward the end of that presentation one of the delegation members approached asking whether the Dutch civil service act of 1929 was available in English, since their president had determined that his country needed a civil service act. Can we really transplant legislation, regulation, best practices, particular policy instruments, and so on, to another societal and political-administrative context? More than 30 years ago the organization theory scholar Howard Aldrich warned that organizational “innovations have failed when introduced into societies with non-supportive cultural and institutional traditions.” (1979, p. 22) This is clearly a challenge in many of the newly independent states in Africa and Asia, struggling as they do with a heritage of colonial government while trying to develop a more indigenous system of government.

There is no doubt a globalization of structures of government and a globalization of concepts and terms used to describe governments and prescribe reforms. However, this structural convergence does not translate into functional similarity. That is, government and administration in any country has clear local features, heavily influenced by cultural heritage. In that sense, globalization is not expected to occur. If anything, the globalization prompted by increased intertwinement of economic markets and by communication devices has resulted in increased awareness of the cultural differences. The prime example of this is the European Union, where all member states operate in a particular institutional framework but fight to keep their national identity. That national identity can be an abstraction (for instance, flag, national anthem), but certainly includes the more mundane and tangible elements of, for instance, “national” foodstuffs. While European integration includes the standardization of many products (e.g., electrical outlets), the European Commission has yet to succeed in developing standards for food and drinks such as English ale, French brie, German bockwurst, and Italian spumante.

1 Even though there is no consensus about how exactly “science” should be defined (for seven different definitions see Bunge, 1996, p. 186), there is strong belief in the existence of a “scientific method” in the social sciences. Interestingly, a corresponding concept does not exist in the natural sciences (see Weinberg, 2001, p. 85).

2 For a discussion of material objects and of first- and second-order formal objects, see Raadschelders, 2011b, p. 10.

3 Keep in mind that Kuhn's analysis mainly concerned the natural sciences, and that both he and Feyerabend were very careful in pointing out that the applicability of their ideas in and for the social sciences was unclear, to say the least. Kuhn' s incommensurability thesis was criticized by Bunge (1996, p. 118) as being analytically and historically false. Analytically, because only theories that concern different domains are incommensurable; historically, because rival theories have coexisted. Furthermore, an older paradigm (for instance, Newtonian mechanics) is still valid in the context of a newer paradigm (for instance, quantum mechanics) but then under stricter ceteris paribus conditions.