CHAPTER TWO

THE ROOTS AND DEVELOPMENT OF GOVERNANCE, GOVERNMENT, AND PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION

The Envelopment of Local Communities in Upper-Local Polities over Time

Human life, and thus history, is about association. Theories about rent-seeking and self-maximizing individuals and institutional theories concerning imagined communities do not capture human behavior and desires entirely. Much economic theory assumes individuals to be selfish, but that breaks down in the face of the fact that all human beings associate with some people. In Fukuyama's words “there was never a period in human evolution when human beings existed as isolated individuals” (2011, 30; emphasis in original). Historical and anthropological theories assume that individuals are defined by the institutional context in which they are socialized and in which they will stay, but that falls flat when realizing that there is ample evidence of human agency breaking the mold and of people moving away from where they were born. Indeed, according to rabbinical exegesis the divine created people free and thus brought a basic element of uncertainty and choice into the world (Bereshit Rabba 9:4; referenced in Gardet and others, 1976, p. 156).

The earliest human association is nomadic, local, and informal. That is, there are no institutional arrangements beyond kinship and friendship structures. However, we shall see in this chapter that thousands of years before human beings started to record their activities, they became sedentary and created governance structures that could facilitate higher population densities. For much of history, and throughout the globe, political-institutional arrangements oscillated between city-state and empire levels. Furthermore, until the eighteenth century structures of governance and government not only waxed and waned (for example, “the rise and fall of . . .”), but also the relation between local and upper-local levels of governance and government was equally unsettled. The supremacy of upper-local governing arrangements was not guaranteed, and local communities were often the last resort when upper-local polities collapsed. It is only in the past two centuries, and across the globe, that local communities, both formal and informal, have been more or less permanently enveloped by and embedded in upper-local polities better known as national or territorial states.

In this chapter we discuss types of societal associations and their governance systems as can be found around the globe (Section 1), then turn to the emergence and development of local (Section 2) and upper-local governing arrangements (Section 3). Upon the basis of these sections we present a model of global government development (Section 4). Thus far, the content of this chapter is descriptive, but some attention has to be given to explanations for the emergence and development of government (Section 5). This will demonstrate that a single explanation and/or understanding of one of the most pervasive social phenomena in our time, that is, an intertwined government and society, is quite a challenge. Understanding how different governments are today from those as little as two centuries ago provides the foundation for our discussion of the emergence of thinking about government in ancient Greece, which then was mainly political theory about the relation between ruler and ruled. In the course of time, that is when governments slowly but surely established themselves as actors central to any society; this was complemented with attention to government in the study of public administration (Section 6). In the concluding section we will briefly reflect upon how upper-local governments buttressed their claim of authority by means of structuring territorial and bureaucratic organization, a theme developed at length in the next chapter.

A brief set of definitions is necessary before diving into the chapter. First it is important to distinguish governance from government. Governance refers to all institutional arrangements in society that are created to address challenges that individual effort and capacity cannot resolve. Hence, governance includes a variety of institutional arrangements as further discussed in Section 1. Government refers to all organizations that operate within an institutional superstructure in which sovereignty is invested and where its officials have the authority to make binding decisions of all people living in that sovereignty. By contrast, churches, labor unions, sports clubs, guilds, and so on, are institutional arrangements that contribute to the governance of society, but they are not part of government. Our definition of government is akin to Max Weber's definition of state that emphasizes the state as the only actor that has the authority to use coercion or violence in the administration of the sovereignty. Finally, public administration is the term we reserve when referring to the study of government and governance.

Another comment is necessary and that concerns the subtitle of this chapter. The development of government is generally described from top-down and up-time perspectives. The top-down perspective is the one that considers the upper-local, highest level institutions and the elites who populate them. The local level is then regarded as merely an appendage and as fairly insignificant. The up-time perspective concerns the fact that history is reconstructed, thus written in the perspective of the present. This means that only those parts of the past are presented that reinforce particular political, social, and economic arrangements in the present. A good example of up-time reconstruction is the creation and imposition of a sense of national identity and culture in the nineteenth century (Fisch, 2008); indeed, people can even invent traditions and especially do so at times of major social upheaval (Hobsbawm, 1983). In contrast, communal engagement grows bottom-up and history unfolds down-time. In this comparative voyage of governments in the past and today, we emphasize the interplay between local and upper-local levels of governance and government as a theme that has been with people from the moment that city-states became states and empires, that is, since approximately 3,000 years before the common era (BCE).

Types of Governing Associations

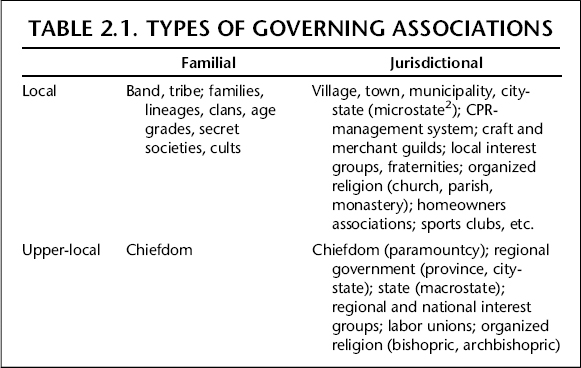

People have always lived together in communities, some smaller, some larger. Really small communities will not have formal associations beyond the kinship group that ties its members together. The term local community refers to two quite different but related phenomena. First, it is a group of people who share language, customs, and history. If small in size, say not much more then 20/30 to 70/100 people (Corning and Hines, 1988, p. 146; Hallpike, 1986, p. 5; Mann, 1986a, p. 42; Masters, 1983, p. 161; Service, 1967, p. 111), such local communities are referred to as bands. Up to roughly 10,000 BCE the band was the dominant type of organization among the nomadic hunter-gatherers (Flannery, 1972, p. 401). Bands may contain various kinship structures (families, lineages, clans: in that order) and other sub-groups (such as secret societies, cults) (Liverani, 2006). They can be part of a larger, culturally determined whole, but generally living independently (see below: cf. Dunbar, 1993). The !Kung of the Kalahari desert are a good example. Bands generally do not have political institutions that are authorized and/or legitimized by a higher authority. They do have, though, institutions of their own. When bigger in size, say, beyond 150–500 people (Mann, 1986a, p. 143), the term tribe is considered more appropriate. These are generally governed by a rudimentary political arrangement such as a council of elders. Tribes can become part of a larger whole, a chiefdom (or paramountcy), yet may live their lives pretty much separately.

Once the population in these local communities grows beyond the size where face-to-face interaction between all members is no longer feasible, and thus has become an imagined community (Anderson, 2006; compare Anderson's concept with that of Bertrand Russell's “artificially created societies,” 1962, p. 203), local communities tend to formalize their associational life in order to establish accepted modes of interaction for settling collective problems (see Table 2.1). In this second sense, local communities encompass an entire town population (for instance, municipality, city-state) while specific sections of that population may have associations of their own as well (for example, a church denomination, a craft or merchant guild, farmers managing an irrigation system, fisherman sharing fishing rights). It is also possible that the local institutional arrangement merely concerns the management of the natural resource upon which the population depends for its livelihood. In that case the local association is a pure common pool resource management (CPR) system. At some point they can be enveloped by larger political entities, yet remain more or less independent (as was the case with Dutch water boards until the late eighteenth century). Whether specific-purpose local associations actually developed into general-purpose political communities that provided and/or managed more than one service or natural resource is a matter that requires further research.1

Local associations can become part of a more formalized chiefdom without limiting the autonomy of the local units (Spencer, 1990, p. 7) or they can become a city-state with 1,000 up to 100,000 people (in a few cases more) where villages lose their political autonomy to a unifying political structure (Sanderson, 2001, p. 312). At that point the local political community and the various associations serve as the backbone of an upper-local (regional, and possibly even supraregional) political regime and become the default option when the upper-local polity is in decline.

People nowadays tend to think of local communities as formalized local governments that have jurisdictional boundaries and are part of a larger political regime and sovereignty upon which they are dependent to a smaller or larger degree. These local governments are the backbone of upper-local regimes because their populations supply the financial, natural, and human resources needed to support upper-local regimes. How important they are is illustrated by the fact that an upper-local (can be city-state/microstate, or regional, or supraregional/macrostate) government that fails to incorporate the local community or governance structures is often destined to disintegrate as shown by the fate of various Mesopotamian polities and, more recently, of African colonies that were governed through indirect rule, of the former Yugoslavia, and the former Soviet Union. If and when an upper-local political regime dissolves, the local associations are left to run their own affairs, at least for a time.

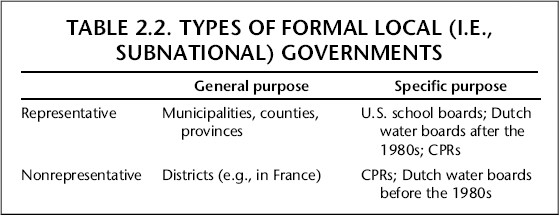

It is clear that several types of formal local government can be distinguished based on the range of their services, on the extent to which their political institutions are representative of the population, and on the extent to which citizen initiative is allowed and respectively encouraged. General-purpose local governments, such as municipalities, provide a wide range of services, while specific-purpose local governments offer one service or manage one resource only. In many countries, general-purpose governments are the most common and, generally, more numerous than specific-purpose governments. The United States is an exception with its approximately 40,000 specific-purpose governments and 40,000 general-purpose governments (Ostrom et al., 1988), representing a dramatic reduction of both general- and specific-purpose governments in the past 50–100 years. In some Western countries specific-purpose governments are returning (for instance, garbage-collection regions in the Netherlands). Some of these general- and specific-purpose governments represent the local population at large, while others only represent a portion of the population (see Table 2.2).

To understand the role and position of local associations in the emergence and evolution of upper-local political regimes, it is necessary to look beyond the formal local, subnational government units and include local communities, such as bands, tribes, and chiefdoms, that encompass the entire membership as well as those local associations that share governance with the formal local government in the sense that they provide a rule structure for a subcategory of the local community. These subcategories include (see Table 2.1) common pool resource (CPR) management systems, craft and merchant guilds, organized religion, and any other type of local associations.

All Government and Governance Started Local

The literature that engages the question of the meaning of associations in the development of humanity can be grouped into two main categories: political theory on the one hand and evolutionary biology, sociobiology, and anthropology on the other.

Starting with the political theory literature, as far as we know the first author to consider the meaning of local associational life was Alexis de Tocqueville writing about New England townships. In his view these were not so much created as they were born of themselves, “almost secretly in the bosom of a half-barbaric society. . . . The institutions of a township are to freedom what primary schools are to science; they put it within reach of the people; they make them taste its peaceful employ and habituate them to making use of it.” (Tocqueville, 2000, p. 57) In the same spirit John Stuart Mill observed that local government was the school for democracy, the level where people first receive their political and civic education (Mill, 1984, p. 378). De Tocqueville was also the first to write that “In democratic countries the science of association is the mother science; the progress of all the others depends on the progress of that one.” (de Tocqueville, 2000, p. 492; emphasis added)

The views of De Tocqueville and Mill are reinforced in the twentieth century. Arthur Bentley's idea that the interactions of groups form the basis of political life (1908) proved to be quite influential in the pluralist perspective upon politics in political science. In 1962 George Stigler wrote that “An eminent and powerful structure of local government is a basic ingredient of a society which seeks to give the individual the fullest possible freedom and responsibility.” (as quoted V. Ostrom, 1974, p. 120). Vincent Ostrom's notion of democratic administration stresses self-governance and polycentricity. He revived De Tocqueville's notion of public administration as a science of association. In his footsteps, Guerrero Ramos (1981, pp. 24–43) called for a substantive theory of human associational life, and Curt Ventriss (1991, p. 7) urged to move toward democratic self-governance. Today we witness increased attention to the meaning of local citizenship and community involvement, again, as the grassroots for nation-level democracy and new types of citizenship (for instance, Clary and Snyder, 2002; Vigoda and Golembiewski, 2001)

Local associations are purposive associations “in which individuals recognize themselves as united or bound together for the joint pursuit of some coherent set of substantive purposes or ends.” (Spicer, 2004, p. 355) The concept of purposive association was coined by the British historian and philosopher of history Michael Oakeshott as referring to the idea of the state, but, as Spicer points out, it can refer to any form of human association.

The political theory concerning the role and meaning of local associations not only acknowledges that such local self-governance arrangements existed but that they are actually vital to the health of the larger polity. Consider the following quote from a study by the historians John McNeil and William McNeil: “we . . . need face-to-face, primary communities for long-range survival: communities like those our predecessors belonged to, within which shared meanings, shared values, and shared goals made life worth living for everyone . . . perhaps the most critical question for the human future is how cell-like primary communities can survive and flourish with the global cosmopolitan flows . . .” (2003, p. 326; emphasis added.)

From a different point of view, studies of groups in evolutionary biology, sociobiology, and anthropology are of direct importance to the understanding of local associations. David Wilson and others (2008, p. 7) observe that the group is making its comeback as a unit of analysis; David Wilson and Edward Wilson write at the end of their article that “Selfishness beats altruism within groups. Altruistic groups beat selfish groups. Everything else is commentary.” (2007, p. 348) Groups are vital to individuals. Without them the likelihood of survival is significantly reduced. Within any primate group there is status differentiation through the establishment of rank, and this works best with a small group size (De Waal, 1982). When group size increases, primates have the tendency to split into two or more units, and larger groups can only be created through a hierarchical clustering of smaller groups (Dunbar, 1992, p. 485). This finding is also tested and confirmed for human associations. Interestingly, these various groups can be and often are interconnected. Even small hunter-gatherer groups today “live in complexly structured social universes that involve several different levels of grouping.” (Dunbar, 1993, p. 685) That is, they live in small groups of 30 to 50 individuals (like an overnight camp) that are somewhat embedded in an intermediate level of 100 to 200 people (such as a more permanent village or a clan or lineage group culturally defined), which, in turn, is part of a large population unit with 500 to 2,500 members and can be called a tribe (Dunbar, 1993, p. 686).

This social order is the result of a bottom-up effort to coordinate actions for survival, such as avoiding potential conflict (Leeson, 2008, p. 69) or searching for food and shelter. After Friedrich Hayek, economists came to call this “spontaneous order” or coordination without command (see also Tullock, 1994) which seems to be one solution to the tragedy of the commons. Intriguingly, it is then assumed that such spontaneous orders cannot easily, if at all, be replaced by the deliberate creation of some upper-local authority. In fact, efforts to subordinate individuals and their spontaneous order will destroy local coordination (Polanyi, 1951, pp. 35–36, p. 112). Matthew Lange distinguished four ideal types of coordination structures: bureaucratic, associational, market, and clientelist (2005, p. 50). The first is most associated with the national or territorial state and facilitates large-scale coordination. He regards the second as illustrative of voluntary groups. The latter two are coordination mechanisms but less relevant to the central concerns of this book.

So what is the difference between the bureaucratic and associational approaches? Political theorists prescribe the necessity of local associational life, while evolutionary biologists, sociobiologists, and anthropologists describe and explain it. For centuries, and in the slipstream of Thomas Hobbes, it was believed that the only choice people had was that between an absolute state or anarchy. However, local associational life existed throughout the millennia and has been simply overlooked as a basic and foundational set of institutional arrangements important not only for the survival of human groups but also for the endurance of the larger polity. Their centrality and contribution to our understanding of public administration as a study was further recognized with the Nobel-Prize-winning work of Elinor Ostrom on the economic and social features of self-governing associational systems (Ostrom, 2009).

When, how, and why did these local associations and—later—political communities emerge? The first question, when, is fairly easily answered: From about 10000 BCE humankind changed from living in small-scale, egalitarian societies to complex stratified states at extreme rapid speed (Corning, 1983; Hallpike, 1985, p. 136; Roscoe, 1993, p. 111; Massey, 2007, pp. 2–4). The transition from hunter-gatherer and nomadic to agricultural and sedentary society is often referred to as the neolithic revolution and involved the domestication of plants and animals, allowing people to settle down and produce a surplus. This encouraged population growth and paved the way for urbanization. Hamlets became villages, and some villages became towns, or small cities, or even city-states. The latter has been defined as: a central state with a surrounding, dependent hinterland within a day's walk from the central town/city (Hansen, 2000a, p. 19). The formation of ever larger political entities is a universal process, since states emerged independently, though at different times, in at least six different regions in the world: Mesopotamia, Egypt, India, China, Mesoamerica, and South America.3 These are referred to as the pristine states.

Theories about how this happened are, so far, characterized by a focus on processes of increased societal complexity, increased functional differentiation of the political and economic communities, and centralization of political power. Until the early 1980s these processes were explained mainly in terms of unilinear stage models.

Stage models are based on the assumption that the size of political regimes increases over time.4 The most well-known is the one developed by Elmer Service (1962; 1967, pp. 111–144) who describes political development as proceeding from band, via tribe and chiefdom, to state.5 While his studies do not focus on the state, it does not stop him from noting that state bureaucracies play a cardinal role in the solution to social problems as well as in the dissolution of political regimes (Service, 1975, pp. 320–321). The bands and tribes mentioned in Table 2.1 are basically undifferentiated political regimes, mainly because their population size is small, their headmen have little formal authority, and they lack an organizational apparatus to help uphold their authority. The state (or empire) is the end-stage in this stage model, and the chiefdom is the bridge between the more or less acephalous bands and tribes and the bureaucratic state (Earle, 1987, p. 279). Writing at about the same time, Robert Fried described social-political development as one moving from egalitarian (such as band, tribe), to ranked (for instance, chiefdom), to stratified (such as state) societies (1967). Colin Renfrew focused on the chiefdom, a polity characterized as transitional, having a permanent chief who fulfills various functions (military leader, legislator, priest, judge), having fairly clear territorial boundaries, and some degree of redistribution of resources (1973, p. 543; 1974, p. 78). Group-oriented chiefdoms have a relatively low level of technology, some craft specialization, and periodic distribution of resources (usually food) on special occasions. Individualizing chiefdoms have identified princes (for instance, the Celtic chiefdoms, see Arnold and Gibson, 1995; or the Polynesian chiefdoms, see Service, 1975, p. 150) and a somewhat institutionalized redistributive system (Service, 1975, pp. 74 and 79), but do not have an internally specialized government apparatus (Yoffee, 2005, p. 25; Wright, 2006).

While attractive in their simplicity, stage models suffer from several problems. Jonathan Haas observed that Service, Fried, and Renfrew presented their anthropological stage models as fact, even though they are not supported by the ethnographic and archaeological record (1982, p. 12; see also Claessen and Van de Velde, 1987, p. 3). Christopher Hallpike pointed out that social evolution could not be fruitfully described in stages because social reality manifests itself in multiple configurations, and advocated instead an analysis based on principles or generalizations addressing society's increased complexity.6

A second type of critique concerned the centralization bias of stage models, which emphasized exclusionary (i.e., individualizing) strategies in the pursuit of political power and paid too little attention to corporate (that is, group-oriented) strategies (Blanton and others, 1996, p. 2; Haas, 2001b, p. 242). Exclusionary strategies for the acquisition of power are usually wealth-based, while corporate or collective strategies in the pursuit of power are most often knowledge-based (McIntosh, 1999, p. 17). Tribal societies and their governing arrangements in contemporary Africa, Latin America, Australia, the Middle East, and Oceania, even when embedded in territorial states (see next chapter), are excellent examples of such a corporate or collective orientation. Insofar as tribal societies have multiple centers of power, as is, for instance, the case in Africa (McIntosh, 1999, p. 22), they can be labeled polycentric. Good examples include the Andrantsay in the southwest central highlands of late eighteenth century Madagascar, the Baganda in mid-nineteenth century Eastern Africa, and the Imerina in the central highlands of Madagascar in the late eighteenth century (for these three, see Wright, 2006). But they also include the tribal societies in the mountainous regions of Southeast Asia up to the middle of the twentieth century (Scott, 2009), in the Middle East and the Indian subcontinent (including Pakistan and Afghanistan), and aboriginal groups in Australia to this day. CPR-management systems provide yet another example of knowledge-based, collective communities. However, polycentrism can also exist under exclusionary strategies, of which the feudal European Middle Ages are an example.

A third line of critique is that a linear representation of political development implicitly assumes that smaller units dissolve into larger ones: bands into tribes, tribes into chiefdoms, and chiefdoms into states. However, throughout history smaller units have become part of but did not always, possibly even not often, dissolve into a larger entity. State and tribes not only coexist but they may actually sustain one another, as the cases of Transjordan tribal populations during the Hashemite regime (early twentieth century) (Alon, 2005) and, more recently, of tribal communities in Afghanistan have shown. Acknowledgment of tribal sovereignties in Australia, Africa, and North America in the later part of the twentieth century has strengthened, rather than undermined, the overall claim to sovereignty by the territorial and national state. Also, territorial or national states have started to help settle leadership disputes between tribes and/or acknowledged tribal sovereignty. An example of the former is the 2003 Traditional Leadership and Framework Act of South Africa;7 an example of the latter is the status of Native-American tribes as sovereign in their own right.

A fourth line of critique concerns the fact that most research has focused on the elites (Brumfiel, 1992, p. 555) and, we add, on the top level of government. Obviously, the activities of local officials are recorded much less than those of their upper-local chiefs and kings, and thus there is much less information available about local associations in general (including historical CPRs) and, more specifically when these existed, of local government bureaucracies. There are some exceptions (Foster, 1982; Wright and others, 1969; Walters, 1970) and there may be more, but we will not know until the many clay tablets still awaiting transcription have become available.

Given the focus on top government levels and their elites, political change has often been conceptualized as a “rise and fall of . . .” (fill in the blank) with little, if any, attention to the fate of the various local communities and associations. Perhaps they were in turmoil once the upper-local regime folded, but perhaps they were not. So complete is the focus upon the rise and fall of upper-local political regimes that the continuity provided by the local communities and associations is overlooked. Indeed, there is evidence throughout history that local communities and associations were vital to society. For instance, in ancient Sumer the governing body of a village (for instance, the abba ašaga or field fathers) continued to function when the assembly of city rulers (unken) chaired by a “big man” (lugal) responsible for adjudicating disputes between city-states and for deciding on peace and war, disintegrated because of some natural or man-made disaster (Westenholz, 2002, p. 27). There is no reason to assume that it was different elsewhere. Archaeological research has shown that the notion of a “dark age”8 in Ancient Greece between the twelfth and eighth centuries BCE and in Europe between the fall of the Roman Empire and the flash of the Carolingian empire is much overstated. Also, no matter how upsetting events during the French Revolution or the Third Reich were, there was much continuity not just in terms of elites continuing in office, but also at the local associational level. It is upon the latter's continuity that upper-local political regimes could rise and fall. To be more precise, a local regime could grow its sphere of influence via conquest, amalgamation, or otherwise and become, temporarily, the center of an upper-local polity at regional (chiefdom) or a supraregional polity at an even higher level (state, empire).

The Emergence of Territorial States as Upper-Local Polities

It makes sense to conceptualize political development as a process where (a) local regimes temporarily achieve paramountcy or even kingship status over neighboring local regimes, (b) that sometimes became semipermanent, because they successfully incorporated local officials in the administration of the larger realm and managed to tie local populations to the center through, for instance, redistributive policies and rituals. Logically, upper-local regimes generally do not come out of the blue. In fact, very few upper-local political regimes started at the upper-local level (among the few exceptions: Scandinavia during the Viking Age, and early Anglo-Saxon England). Most political regimes, and the changes in them, started locally, whether as a territorial polity or as a political movement. For much of history, political regime change also involved the change of the territorial center and the political superstructure. It is only in the past 200 years or so that political regime change generally does not involve changes of the political superstructure, changes in the circumscription of the sovereignty, or changes in the location of the center of power. An exception to this rule can be made for political regimes whose institutional superstructure was imposed by outside forces (for instance, colonial government; Germany and Japan after the Second World War) or was changed by internal regime change (for instance, from dictatorship to democracy). No matter how vehemently executive and legislative elections are contested in democracies, in the light of history regime change today is relatively peaceful.9

Many singular explanations for the establishment of a sedentary lifestyle and for the emergence of the state have been suggested. The archaeologist Vere Gordon Childe argued that urban and technological development accounted for this (1942). The historian and sinologist Karl Wittfogel suggested that irrigation prompted the development of states (1957). The demographer Esther Boserup believed demographic development (such as population size and density) to be a prime mover (1965). Others emphasized the domestication of agriculture and animals. Several scholars emphasized conflict and expansionist warfare (for instance, Carneiro, 1970) such as in the warring city-states of Mesopotamia, while others stressed the need for defense (Gat, 2002, pp. 127 and 131; pointing especially to pre-colonial Africa and early Mesopotamia). Yet others have suggested trade and even the integrative power of religion and art (Flannery, 1972, pp. 404–407).10

All these explanations suffer from incompleteness and single-mindedness, and as the stage models were left behind, scholars increasingly turned to the importance of multivariate explanations that could tackle the variation in governance structures in relation to the local physical circumstances (V. Ostrom in Toonen, 2010), that, thus, conceptualized social evolution as multilevel, configural, and interactive (Corning, 1983, p. 13; Corning and Hines, 1988, p. 147; Elias, 1987), recognizing that cultural diversity is a function of distinctive social environments and subsistence patterns (Yoffee, 1979, p. 8). Instead of simplifying social reality through stage models and singular explanations, emphasis shifted since the 1980s to capturing the institutional diversity that has characterized humankind's government and governance since the beginning of history.

This is a daunting task for several reasons. First, Weber was one of the earliest scholars to point to the impossibility of singular explanations: “how can causal explanation of an individual fact be possible . . . the number and nature of causes that contributed to an individual event is always infinite.” (Weber, 1985a, p. 177; author translation) Almost a century later Fritz Scharpf pondered the same: “the potential number of different constellations of situational and institutional factors will be extremely large—so large, in fact, that it is rather unlikely that exactly the same factor combination will appear in many empirical cases.” (as quoted in E. Ostrom, 2005, p. 10) Second, to complicate matters further, the variation is not just between different societies and/or political regimes but also within. The use of orderly flowcharts and formal organizational structures implies that society is a well-integrated, adaptive, and not so complex system. Instead it is “a continually shifting patchwork of internally differentiated communities bound together by interacting contradictions and mediations.” (Brumfiel, 1992, p. 558) And this institutional diversity can only be explained by combinations of variables (Wright, 1977; Claessen and Skalnik, 1978, p. 625). Third, research into the emergence and development of the state suffers from having both too many as well as too few sources of information. We have an enormous amount of information about the past eight to 10 centuries in Europe, thanks to the meticulous conservation of printed matter in archives. There is much less information about the millennia before. At the same time, the potential for information about the ancient past is large. Henry Wright and others noted that about 16,000 economic texts from Ur III had been published, but that many more are stored in museums around the world (1969, p. 99). John Brinkman reported in 1972 that about 900 Kassite tables had been published, but that more than 11,000 still waited transcription (p. 271). Several years later Robert Wenke wrote that decades of intensive research would be required to tackle the “physical scale of the archaeological record.” (1981, p. 118) In fact, archaeologists continue to complain about the lack of time for assessing and coding available sources (Wright, 2006, p. 1). Nevertheless, enough has been translated and discovered that examples can be provided to substantiate the claims made previously.

A Global Model of Government Development

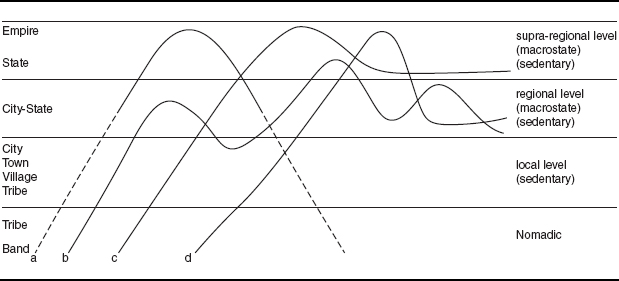

As noticed earlier, the dominant model of political evolution has been linear, either emphasizing a process of continuous growth of territorial and population size in the abstract (see Ibn Khald![]() n; Service), or focusing on the rise and fall of political regimes (for instance, Gibbons' The Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire). When looking, though, at the historical record, several patterns of political evolution can be distinguished (see Figure 2.1). The traditional focus on “rise and fall” is pictured in Figure 2.1 as (a), where the focus on the state/empire stage allows less attention to the “rise” (therefore a dotted line) and assumes a “void” after its “fall” (another dotted line). More common for much of history is a trajectory (b) where bands form a tribe, where tribes settle, and where at some point such a settlement becomes a city. Some of these cities may start to dominate their immediate surrounding areas and become city-states, at least for a while. Such a city-state may lose its authority to another. Especially up to the early modern age, it is quite common that city-states wax and wane, hence the “wavy” line. City-states and city-state cultures can evolve into full-fledged macrostates, the last “bump” in (b), and there are several examples of these. The situation pictured as (c) represents the unbroken development from a small political community to empire, which represents the traditional linear theory of state development. Sometimes these empires fragment into states almost immediately (think of the Carolingian Empire) or after a while (think of the Roman Empire, the Ottoman Empire, the Soviet Union). Equally common is the situation of evolution toward a state or an empire and fragmentation of these into states or city-states, which is pictured as (d). Other trajectories are conceivable.

n; Service), or focusing on the rise and fall of political regimes (for instance, Gibbons' The Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire). When looking, though, at the historical record, several patterns of political evolution can be distinguished (see Figure 2.1). The traditional focus on “rise and fall” is pictured in Figure 2.1 as (a), where the focus on the state/empire stage allows less attention to the “rise” (therefore a dotted line) and assumes a “void” after its “fall” (another dotted line). More common for much of history is a trajectory (b) where bands form a tribe, where tribes settle, and where at some point such a settlement becomes a city. Some of these cities may start to dominate their immediate surrounding areas and become city-states, at least for a while. Such a city-state may lose its authority to another. Especially up to the early modern age, it is quite common that city-states wax and wane, hence the “wavy” line. City-states and city-state cultures can evolve into full-fledged macrostates, the last “bump” in (b), and there are several examples of these. The situation pictured as (c) represents the unbroken development from a small political community to empire, which represents the traditional linear theory of state development. Sometimes these empires fragment into states almost immediately (think of the Carolingian Empire) or after a while (think of the Roman Empire, the Ottoman Empire, the Soviet Union). Equally common is the situation of evolution toward a state or an empire and fragmentation of these into states or city-states, which is pictured as (d). Other trajectories are conceivable.

FIGURE 2.1. A MODEL OF POLITICAL EVOLUTION FROM A BOTTOM-UP PERSPECTIVE11

This graphic representation only visualizes political development; it is not and cannot be an explanation. Perhaps the use of linear models prompted the search for prime movers of social, cultural, and political development. However, as stated previously, social evolution is a function of human agency in response to environmental circumstances and change, so that descriptions of social evolution can only be multilevel, interactive, and configurational. Looking at a periodization of the past that takes the interplay between local and upper-local levels of government and governance into consideration, there really are only three phases in the development of government and the state:

- Pre-8000 BCE: the hunter-gatherer phase with nomadic, small bands. This is the period that Scott (2009, p. 324) called the stateless era.

- From 8000 BCE to 1800 common era (CE): the experimental phase with associational arrangements at the local level oscillating between and/or mixing special-purpose associations and general-purpose organizations, and with varying relations between local associations and governments on the one hand, and with varying relations between local associations and government with upper-local levels of governance on the other hand. These horizontal and vertical types of relations and interactions varied over time in terms of intensity and extent. Scott (2009) distinguishes two periods: One represents an era of small-scale states encircled by vast and easily reached stateless peripheries, and the second is one where the localities and peripheries are permanently encroached upon by the expansion of state power. The latter happened earlier in Western Europe than anywhere else, and the process whereby virtually the entire territory was securely enveloped by and embedded in the territorial and bureaucratic framework of the state was not completed in parts of Southeast Asia and central Africa until after the Second World War.

- Since 1800 CE: the centralized governance phase where general-purpose subnational governments and national, regional, and local single-purpose associations are closely intertwined within a jurisdiction that is circumscribed by the central level. Scott (2009) notes that this is the period when almost the entire globe is “administered space” and where the periphery is reduced to being a folkloric remnant. Perhaps we should consider a fourth phase because since the Second World War decentralization of tasks and services has been widespread, while at the same time governments and societal associations increasingly rely on international organizations (e.g., United Nations [UN], International Monetary Fund [IMF], European Union [EU], North American Free Trade Association [NAFTA], North Atlantic Treaty Organization [NATO], and so forth) for specific services.

Mapping the role and position of the government and associations of local communities in the history of associational life in their interaction with and relation to upper-local political and associational arrangements is very ambitious and may never be complete. Intuitively, human societies are, on the one hand, multivaried in their functioning and in their relation to the physical and sociocultural environment but, on the other hand, quite basic and simple in how they are structured in terms of demarcations of labor/office, of territory, and of single respectively compound functions (see for this Chapter 3).12

We can only find examples of the rudimentary theory presented previously when we step away from the notion that the development of government has to be characterized as a process that (a) was linear, (b) involved continued centralization, and (c) required continued refinement/elaboration of organizational and societal hierarchy. In the light of history all three assumptions are wrong.

The existence of the centralized state is, as Yuwa Wong observed (1994, p. 5), neither “natural” nor easily explained. That is, the dominance of centralized states in the world today, including loosely coupled federations, is hard to understand when considering the inherent desire of people for some degree of autonomy and certainly for belonging to a face-to-face community. People need self-government (see de Tocqueville, 2000; Mill, 1984), polycentricity (V. Ostrom, 1991), and autogestion (Lefebvre; see Brenner and Elden, 2009) at the grassroots level. Sustained centralization has generally been a feature of the past two centuries, and the loosely coupled empires of old have disappeared. However, there have been centralized systems in the ancient world such as during various periods and dynasties of ancient Egypt (Blanton, 1998, p. 147) (with regard to Egypt: think of the intermediate periods during 2150–1980, 1630–1520, 1070–715 BCE) and for most of China's history. Totalitarian regimes are hypercentralized as well, but even there the intensity of centralization waxed and waned during the time of their existence.

With respect to organizational structure, when confronted with a growing workforce, organizations have to differentiate horizontally (in terms of number of units) and vertically (in terms of tiers of hierarchy) to lower the span-of-control while maintaining a clear line of authority with unity of command (Raadschelders, 1997). In the past 150 years or so people are inclined to think in terms of fairly clearly delineated job functions where overlap is avoided. Before the 1800s collegial organization was quite normal in most general-purpose governments from the middle management level up, and job functions were not clearly demarcated. Nowadays, any collegial type of organization in formal governments, i.e., a body of people fulfilling one function together, has been limited to the top level (i.e., that of elected officeholders in the legislatures and executives). In many local associations, though, management is likely to be organized on a collegial rather than a hierarchical basis.

The linear thinking visible in the notion that bands were superseded by tribes, tribes by chiefdoms, and chiefdoms by states is, as mentioned earlier, not supported by facts. As it is, bands, tribes, chiefdoms, and states can and have coexisted (see previous examples). Another example of “hierarchical” thinking is Walter Christaller's central place theory (1966) that identifies a hierarchy of hamlets, villages, towns, and cities based on their economic catchment area, that is, their zonal influence (how much are they a motor for the regional economy?) and their nodal influence (how attractive are they to the surrounding area?). However, such a presentation inhibits the recognition that settlements may have very different functions, and that one town/city may be a second-tier political center but a first-tier religious center, while another is a first-tier craft production center but only a fourth-tier political center (Marcus and Feinman, 1998, p. 11). In addition to this, Mogens Hansen observed that the urban studies literature suffers from lack of attention to the political aspect of urbanization (2000b, p. 606). Perhaps contemporary societies and their governments can be conceptualized as hierarchies in themselves (local, regional, national) and in relation to each other (first, second, third world), but up to the premodern world (say, around the 1500s in a European biased chronology) a combination of hierarchy and heterarchy captures reality far better (Crumley, 1995, p. 3).

Now we can turn to the question, what happened with local associations when the upper-local political regime collapsed in which they were embedded? First, this question can be answered by pointing out that it only rarely happens that a local community vanishes without leaving a trace of what contributed to their demise and to where they went. The fate of the Maya city-states can only be guessed, and it is rare that subsequent civilizations have no memory of what happened. We know what happened to Carthage, but complete destruction of a local community is fairly rare as well. More common is that local communities and their associations continue to survive, or relocate when under threat. When the people of Aquileia in northern Italy felt threatened by the Lombard invasion in 568 CE, they fled south and settled on Torcello, a low-lying offshore island in the northern Adriatic. In time, it would become the independent and very powerful city-state of Venice. The city of Lagash in ancient Mesopotomia was sometimes an independent city-state, while at other times it was subordinate to other city-states (e.g., Kish, Akkad, Ur) (Flannery, 1998, p. 20). Indeed, the history of local governments and their associations, such as the lowland Maya, the central Mexican states, the Andean states, the Mesopotamian (city-) states, and the ancient Aegean polities, has been described as a repetitive cycle of consolidation, expansion, and dissolution (Marcus, 1998, pp. 60, 62, 68, 73, 75, 80, 88, and 90). Specifically with regard to city-states, Hansen (2000b, p. 611; 2002, p. 8) pointed to three different patterns:

- city-state cultures that emerge only once in history, such as Hellas (750–550 BCE), northern China (780–480 BCE), Nigeria (fifteenth to nineteenth century CE), and Nepal (1482–1768/9 CE);

- in some regions city-states disappeared and reappeared with a “dark ages” in-between, such as the Syrian city-state cultures (3500–500 BCE), the Palestinian city-state cultures (2900–1200 BCE), and the Hittite city-state culture (1200–700 BCE);

- in some other regions two periods of city-state culture were separated by the formation of a macrostate. The Sumerian city-states (3500–2300 BCE) were followed by the Old Babylonian Kingdom (1800–1600 BCE) and the Kassite monarchy (1600–1200 BCE). When the latter disintegrated, the Neo-Babylonian city-states reemerged (1200–800 BCE); the Etruscan/Italian city-states (ninth to fourth century BCE) were enveloped in the Roman Republic and Empire (fourth century BCE to fourth century CE), which disintegrated under the threat of the German migrations. Another example is that of the Maya city-states separated by the Mayapan state 1150–1450 CE).

The latter two scenarios are especially interesting because they indicate sufficient local community vitality, and thus invite exploration of the sources of this vitality.

In a dynamic model of political development, the demise of one particular regime does not necessarily coincide with the decline of a culture. Consider that the notion of “the rise and fall of the Roman empire” implies that political dissolution and cultural dissolution were concomitant. However, that Rome lost control over most of its territories did not mean that all of its accomplishments went down with its political control. The best illustration is that the Roman church, whose Christianity became the state religion upon Emperor Constantine's decision in 312 CE, used the existing Roman municipal and provincial jurisdictions to define the boundaries of its parishes and bishoprics (Raadschelders, 2002, p. 10), and they also took over the provision of services such as health care (the Roman military hospitals) and water supply (aqueducts). Both the areas of Mesopotamia and of Christendom are excellent examples of the fact that political boundaries do not always, and certainly not before the premodern period, coincide with cultural or even economic boundaries.

The Development of Thinking about Government: From Political Theory to Public Administration

The topic of political and jurisdictional boundaries in relation to the cultural and economic boundaries across the globe will be discussed further in Chapter 3. In this chapter the theme of territorial states as enveloping local governments and associations requires attention for how people thought about government during that process of increasing intertwinement with society. After all, at some point—sometimes sooner, sometimes after a while—some people will start musing about a phenomenon that had been emerging but they had not yet become aware of. We can pretty much safely assume that at the time of the Neolithic Revolution people had little if any conception of the momentous change involved with substituting nomadic for sedentary life. We can also assume that in the early days when villages and towns were enveloped by city-states or even empires, people did not conceptualize and theorize about political development. Living in larger, imagined communities made some people realize that some type of order was necessary to substitute for the social control assured by relations of kinship and friendship. Hence it was that Egyptian, Mesopotamian, and Chinese rulers issued laws, and these were embedded in a more encompassing, if not always explicit, theory of state and of state-ruler relations such as the Chinese Mandate of Heaven (since the Zhou dynasty of the tenth to the third centuries BCE). Some rulers and their aides restructured the territory they governed, but did so without an overarching theory of state and of state-ruler relations.

The first documented theories about state and state-ruler relations can be traced back to the studies of Plato and Aristotle in Greece and of Kautilya in India. They came to theorize about government and its relations with the population at a time that government had become a well-established, if not stable, phenomenon in—what they regarded as—the civilized world. Their theories had two components. One element concerned the ideal structuring of the state, including and most literally what the ideal city and ideal territorial organization would look like. The second element concerned the ideal relation between those who govern and the governed.

Greek ideas about the ideal city amounted to designing the living space as a grid, carefully outlining the streets and neighborhoods around the center with its market square, temples, and other public buildings. Each neighborhood had a water pump. The works of Plato and Aristotle on the design of cities would continue to influence later thinkers, such as Simon Stevin in the Dutch Republic. Another example is the grid-like design of the American landscape beyond Ohio in the 1785 Northwest Ordinance. Other than that, they did not have a conception of territorial organization beyond the city-state. Aristotle's study of “constitutions” in the Mediterranean area, though, amounted to nothing less than a first consideration of the foundations of any society. Kautilya, writing in the third century BCE and during a time that the Mauryan Empire was established in India, did spend time on designing an ideal overall structure and placed the various kingdoms in it, describing in detail a layering of governing structures from the local up to the kingdom level.

Both the Greeks and Kautilya, though, were primarily interested in the ideal nature of the relationship between ruler and ruled. To Plato the ideal ruler was a philosopher-king, a wise person, educated over decades, having held various lower public offices before being called to the highest office. They were patricians, the guardians of society. This type of literature also found its followers, the most cynical or realistic of whom, perhaps, was Niccolo Machiavelli. Well into the European early modern age, thinking about government was, thus, sometimes about planning and zoning and mostly about the ideal ruler who was the embodiment of government. Hence, we argue, that thinking about government was political theory well into the seventeenth century.

The first book that went beyond describing the relation between ruler and ruled and the ideal living space was written by Veit Ludwig von Seckendorf in 1656. In his Teutscher Fürstenstat (i.e., German Princely State) he laid down in detail the various tasks, services, and activities of governments. Some 70 years later Nicolas De la Mare published his Science de la Police. The study of public administration was born in the slipstream of an expanding state where the ruler no longer personified state and government, and was thus standing above the law and was the source of law, but was “merely” a servant of the state. The development of the study of public administration in the context of increasing awareness of Raison d'État since the sixteenth century, of Rechtsstaat since the nineteenth century, and of administrative state since the twentieth century, has been described in some detail elsewhere (see Raadschelders, 2011b, pp. 12–19). The central point, though, is that the study of public administration as we know it emerged when the state slowly but surely expanded its activities beyond the traditional focus on defense, law and order, and taxation (see Appendix 1). The late seventeenth and eighteenth century public administration was above all a practical study that not only considered various policy areas, but also included attention to archiving, types of correspondence, and so forth. In the nineteenth century, the study of public administration was—in retrospect, temporarily—subsumed in the study of law and/or of political science. With the emergence of welfare state policies in response to the “triple whammy” of industrialization, urbanization, and population growth, the study of public administration once again came into its own and would develop into the vast field of study it is nowadays.

Comparing Government Models: Concluding Remarks

Clearly this book is not the place to describe in detail the origins and development of the study of public administration, but people did start to theorize about government once it had become the substitute for a societal life that had been characterized by and governed through small groups. The structure and functioning of today's governments have no historical precedent. While the people who work for government and sometimes even “run” government today suffer from the same human conditions as their ancestors (take your pick: desire to do good, desire for power, greed, corruption, etc.), they work in a government that is fundamentally different from that even 150 years ago. It cannot be said enough that government is the only actor left that can make binding decisions on behalf of the entire population. In the course of history, it took at least six millennia to settle on a particular type of governance for imagined communities: a state generally larger than a city-state but smaller than an empire, that has internationally recognized boundaries, that has an elected government with supporting bureaucracies, and that has territorially defined subdivisions from the local up to the national level. In that process of state making, the local level, so vital to the immediate needs of all people, was absorbed into a national polity. We will not say that the local level has been somewhat permanently absorbed into a well-defined upper-regional polity whose sovereignty is recognized in terms of international law. But, for the moment, the fact remains that the entire globe, excepting Antarctica, is part of a state. The territorialization and bureaucratization that made the state the most dominant type of polity in the world will be discussed further in the next chapter.

1 One example that comes to mind is the institutional arrangements for water management in the Low Countries that preceded the emergence of villages, towns, and municipalities.

2 The distinction between microstates (i.e., city-states) and macrostates (that is, territorial or national states; see Trigger, 2003) is from Hansen (2000a, pp. 15–16).

3 On a side note, the British statistician Francis Galton, a cousin of Charles Darwin, posited that universal social laws could only be those that concerned phenomena that emerge independently; that is, whose emergence cannot be explained by a similar development elsewhere. The configuration of domestication, urbanization, and state formation appears to be an excellent example and is, to our knowledge, the only example. Galton's observation hinges on human agency as the source for copying behaviors and social arrangements. That states emerged in various parts of the world without there being any evidence of copying behavior could very well be explained by similarity in environmental changes that were global in scope. The end of the last ice age and the subsequently more favorable conditions for agriculture are an excellent example of that kind of global environmental change.

4 As far as we know there are no stage models specific to CPR-management systems or other local associational systems; therefore, the following only concerns state and city-state systems.

5 In all fairness, Service was not the first to describe political development in those terms. That honor must go to Ibn Khald![]() n who published in 1377 a history of the world. See ibid. (2005/1967), The Muqaddimah. An Introduction to History (translated and introduced by Fran Rosenthal). Princeton/Oxford: Princeton University Press, pp. 91–128.

n who published in 1377 a history of the world. See ibid. (2005/1967), The Muqaddimah. An Introduction to History (translated and introduced by Fran Rosenthal). Princeton/Oxford: Princeton University Press, pp. 91–128.

6 Hallpike, 1986, p. 29. The six principles or generalizations of Hallpike (1986, p. 6) are: increased social network size; social order via simplification of social relations and representations; increased differentiation and specialization of relations and principles of order; people socialized into accepting core principles and inescapable features of their society; selection of certain aspects of the world in terms of these core principles; and capacity for change relative to the creative synthesis of preexisting but unrelated elements.

7 Upon this act, the South-African government is authorized to settle disputes about tribal leadership. This was done, for instance, recently for the Bapedi tribe. The Bapedi was a paramountcy since the sixteenth century that had become a kingdom in the 1790–1820 period; because several lineages claim the leadership, the state had to mediate.

8 The “dark ages” concept generally refers to a period in which few, if any, literary sources are left testifying to human activity.

9 In a situation of colonization or of civil unrest (think of the Arab spring 2011–2013), regime change is obviously not regarded as peaceful by the indigenous population.

10 Excavations at Göbekli Tepe, a temple complex dating back to 9500 BCE in southeastern Turkey, have prompted the lead excavator, archaeologist Klaus Schmidt, to suggest that the need for worship brought people together, and that religion is a cause rather than a product of culture (Newsweek, March 1, 2010).

11 This figure was inspired by the dynamic model of Kent Flannery (1998, pp. 62–90), who focuses on increasing and decreasing polity size, and the model by Ingolf Thuesen (2000, p. 65) of cycles in political development of city-states in ancient Western Syria (distinguishing town/village A, city-state B, city-state empire C, and foreign control/empire D).

12 A systematic case-study approach that builds upon examples of local associational and government development from all continents is likely to substantiate the thesis that the associations and governments of local communities are the backbone for and default of upper-local/regional and supraregional political regimes.