CHAPTER FIVE

POLITICAL-ADMINISTRATIVE SYSTEMS AND MULTILEVEL GOVERNMENT

We have seen that the world's lands are almost all circumscribed by territorial states, whose governments can be considered the only actors in society that have the authority to make binding decisions on behalf of the entire citizenry. States have been able to centralize and channel political and administrative power. The institutional superstructures of the political and administrative system are very similar everywhere. First, states can be categorized according to a variety of dimensions that are usually presented as dichotomies (Section 1). Second, we need to consider how a country's elite is embedded in the political system: Does it wield power through political parties or through bureaucracies (Section 2)? Third, and recognizable to any one person, is that political power is generally divided across three branches: the legislature, the executive, and the judiciary (Section 3). The administrative structure that operates upon the direction of the executive is generally known as the bureaucracy, and government functions are distributed across multiple departments that in turn are subdivided in multiple units (Section 4). In this chapter we will focus on the overall structural features of this political-administrative—that is, governmental—system. How bureaucracies function in terms of their organizational culture and how they are regarded in their respective societies will be the subject of Chapter 6. The functioning of the political-administrative system in terms of relations between elected and appointed officeholders and in terms of bureaucracy as a personnel system will be further explored in Chapter 8. There is one more element that befits the structural focus of this chapter. We have already seen that a state's territory is subdivided in at least two, and often more, territorial and layered subdivisions (Chapter 3), and we will have to discuss these again but now in terms of multilevel and multiactor government and governance (Section 4).

Basic Distinctions of Political Systems

As we discussed in Chapters 3 and 4, social stratification will inevitably develop in sedentary communities, and that includes distinctions between those who govern and those who are governed. This paragraph is divided into three subsections. In the first subsection, and following Blondel's categorization (1995), we will briefly discuss five main types of political systems. In this section some attention needs to be given to the type of political party system since it is related to the type of political system. However, and strictly speaking, the political party system is not part of the administrative/governmental system. The political party system mobilizes people to participate in the political process, by serving as platform for advocacy, by channeling people's desires and needs into policies and programs, and is (in most countries anyway; the United States is an exception) the body that selects candidates for public office from among its membership. After this excursion into something that is outside the structure of government, we continue characterizing the institutional superstructure of governments. In the second subsection of this section, we outline the distinctions between unitary and federal systems and pay attention to degrees of centralization and decentralization in each. The third subsection is devoted to the comparative typological analysis of democratic systems in general. We then zoom in on the expression of democracy in presidential and parliamentary systems in the fourth subsection.

Five Types of Political Systems in Relation to Political Party System

For most of history, political systems were to a smaller or larger degree based on traditional authority. There generally was one ruler who ruled with support of the social, economic, and political elite of the territory. The population at large had no political rights; hence most historical political systems were inegalitarian by nature. These traditional inegalitarian political systems, as Blondel called them (1995, p. 38), are thus basically “absolutist.” Historical examples would include almost all political regimes of sedentary communities across the globe in the past; early modern examples are the absolutist monarchies in Western Europe in the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries. Blondel labeled these systems as “traditional” because they preserve oligarchy and social inequality, while at the same time retain some degree of popular support. In the contemporary world, this type of regime has become very rare but is still found in the Arabian peninsula, in parts of southern Africa, and in the Himalayas.

Once popular support for a traditional regime is diminishing, a political system may become more authoritarian-inegalitarian (Blondel, 1995, p. 39). However, authoritarian-inegalitarian regimes may also emerge in response to problems in a liberal-democratic system (as in the cases of emerging fascism in Italy and national socialism in Germany after the First World War) or in response to failing populist regimes (as has happened in newly independent states in Africa, Asia, and Latin America after the Second World War). Populist political systems emerged especially in South America in the earlier nineteenth century and in Africa in the 1950s and 1960s. For such a system to succeed it is important to have strong and charismatic leadership.

Blondel's typology mentions two much more common systems, namely the egalitarian–authoritarian and the liberal democratic systems. Communist countries generally have egalitarian-authoritarian systems, and examples include the former Soviet Union, countries in Eastern Europe that were satellites of the USSR, China, North Korea, Mongolia, Vietnam, Cuba, Angola, Mozambique, and Ethiopia. The egalitarian-authoritarian label may seem paradoxical, but Blondel argues that popular unrest in Russia and Eastern Europe since the 1990s suggests that communist regimes were more egalitarian than those that replaced them (Blondel, 1995, pp. 37–38). North Korea has become more authoritarian as well.

Finally, there are the liberal democratic systems found in Australia, India, Israel, Japan, New Zealand, North America, several South American states, South Korea, Western European countries, and some countries in Africa and East Asia. We will pay a little more attention to these liberal democratic systems since they have been gaining ground steadily from the mid-nineteenth century on (see subsections following).

One feature of many contemporary political systems is that they have political parties. We will not discuss political party systems in detail, nor electoral systems, nor types of political parties (tribal, ethnic, religious, class-based, and so forth), since this lies outside the objective of this book. However, since it is part of the context in which governments operate, we will pay some attention to it.

In the earliest human communities, we assume that the bonds of band and tribe must have been strong enough to deal with interpersonal conflict and collective challenges. There is no archaeological evidence of formal political institutions in hunter-gatherer societies, let alone political parties. Most historical political systems had formal political institutions, but there were no political parties. Rulers came to power on the basis of hereditary right or military might. In such no-party systems the local community must have been strong enough to manage collective needs. Whether people felt any conflict with the center or had different opinions about the structure of the society at large, its organization, or its policies, we do not know. We do know, however, that sometimes they successfully rose in revolt, and the best examples are the American and French Revolutions. In the modern world there are very few no-party systems left (Blondel, 1995, p. 154). Most of these are found in the Arabian peninsula. The no-party systems in Afghanistan, Ethiopia, and Libya were replaced by single-party systems in the second half of the twentieth century. In the 1970s and 1980s, military regimes in African, Latin American, and Middle Eastern countries abolished political parties, but those regimes proved unstable, and they are in decline since the 1990s. With an eye on the Arab Spring since 2010, it seems that the legitimacy of one- or single-party systems is increasingly under siege. Rulers have been forced out in Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, and Yemen. There have been civil uprisings in Bahrain, and they are still (at the time of this writing) ongoing in Syria. Major civil unrest occurred in Algeria, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, and Sudan; minor civil unrest has been observed in Lebanon, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Djibouti, and the Western Sahara.

In earlier times there may have been prepolitical “parties,” and those are termed “factions.” One example are the factions in the Senate of the Roman Republic, some supporting the republican ideal, with others leaning more toward monarchy (especially in the swirling debates around what Julius Ceasar wanted: to be king or not). Another example is the seventeenth and eighteenth century Dutch Republic of the Seven United Provinces, where two factions strove to realize their view of the desired political system. The Orange Faction wanted a confederacy with a strong stadtholder in the person of the Prince of Orange-Nassau. The State Faction favored a confederacy where the highest-ranking confederate official/civil servant (that was the State-Pensionary) would be running the republic's business. (On a side note: Some political parties in the contemporary Dutch kingdom favor monarchy while others advance the notion of a republic.)

Political parties are unique to the modern world. They emerged in the nineteenth century, at the same time as or in the slipstream of the appearance of labor unions. The position of the people evolved and changed dramatically as well: from people as subjects to people as citizens with rights, and not merely obligations. Those citizens then turned into voters (Vigoda, 2002a). People as citizens (see Chapter 4) discovered the freedom of association and found strength in numbers. Political parties and labor unions also became a mechanism, and they networked to link citizens to local, regional, and national levels. It helped that, at the same time, newspapers became widely available to the public at large.

No-party and single-party systems are not particularly stable, for both may suppress discussion of conflict (the following based on Blondel, 1995, pp. 156–158). Single-party systems have been a feature of totalitarian governments under communist, fascist, or national-socialist regimes. Also, many single-party systems emerged in Africa after independence, but these were often toppled by military coups. There are/have been countries where one party is so dominant that it dwarfs the others (Egypt, Madagascar, Mexico, Nicaragua, Singapore, and Taiwan) (for more detail on single-party systems, see Blondel, pp. 159–163).

Two-party, two-and-a-half party, multiparty with dominant party, and multiparty without dominant party systems (the distinctions from Blondel, 1995, pp. 170–171; the brief discussion below also Blondel, 1995, pp. 171–179) generate competition among various groups, but it is impossible to characterize countries simply because “times they are a-changing.” For instance, until the 1970s Austria, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States had a two-party system. Looking at Britain only, in the 1970s the Liberal Party emerged, marginalized in the 1990s, and is currently (2013) the junior partner in the cabinet. The great disadvantage of a two-party system is the potential for severe politicization. This is no better illustrated than with the example of the United States. That the White House and Senate are in Democratic hands, and the House controlled by the Republicans since 2010, has resulted in serious gridlock. Another problem with the two-party system, also known as the first-past-the-post system, is that the winning party may well engage in “na-na boo-boo politics,” that is, a politics that generates an attitude of “now that I'm in power I'll reverse some of the previous administration's decisions.” That a two-party system can work is shown by, for instance, Germany since the Second World War and the United States in the 1960s and 1970s.

Two-party systems are also known as majoritarian systems, since one party has a majority in the legislature. Multiparty systems are referred to as consensual systems, since no party has or is expected to gain an absolute majority in the legislature. Examples of these include France, Israel, the Netherlands, and Nigeria. In these countries, ministerial cabinets are generally coalitions of parties. As an introduction to the next subsection we refer to Arend Lijphart's work, that established how consensus democracies generally “demonstrate [ . . . ] kinder and gentler qualities . . .” They are usually welfare states, incarcerate fewer people, are more generous with development aid, and are better at protecting the environment (1999, pp. 274–275).

Unitary and Federal Systems

We have seen in Chapter 3 how states came to define jurisdictions at the subnational level: first at the regional, and then at the local level. Hence, states can also be characterized in terms of the basic relations between the national and the subnational levels of government. In unitary states the authority of subnational levels of government is granted by the national level. The large majority of states in the world have a unitary basis. In federal states the national level of government generally shares sovereignty with (usually) the regional level of government. The local level in a federal state, though, derives its authority from the regional level, and is therefore in a unitary relation. Federal states are often large in terms of territory, and examples include Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Ethiopia, Germany, India, Iraq, Mexico, Pakistan, the Russian Federation, Spain, Venezuela, and the United States. There are, though, also smaller federations such as Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Comoros islands, St. Kitts and Nevis, and Palau (also known as Belau).

Within federal systems a distinction can be made between dual and cooperative federalism. In the case of dual federalism (also known as layer-cake federalism) authority and responsibilities of the federal level are clearly demarcated from those of the subnational levels. It has been argued that the United States in the nineteenth century was an example of this, but most scholars argue that it was theory rather than reality (Elazar, 1966; O'Toole, 2000; Wright, 1988, p. 67). The reality in the United States is one of cooperative federalism (also known as marble-cake federalism) where the different levels of government are together active with and responsible for policy making and service delivery. An excellent visual illustration of that is the intricate and expansive cooperative structure of early childhood education programs in Minnesota (Sandfort, 2010, p. 640).

Several types of federal systems have been distinguished in the literature (see Watts, 2008, pp. 10–11) but for the purposes of this book these need not be discussed, except for one. A confederal political system is where political power rests with the constituent parts. Historical examples include the United States (1774–1787) and the Dutch Republic (1581–1795); contemporary examples include the European Union, Serbia and Montenegro, and Switzerland.

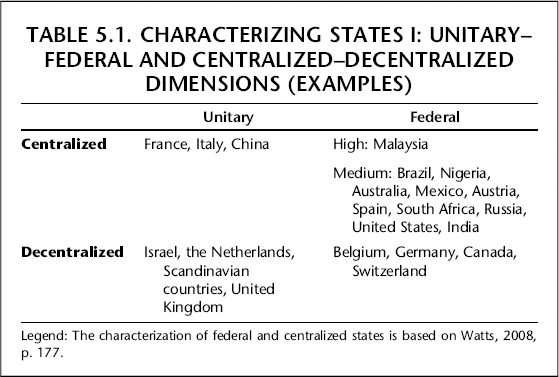

Having a unitary or federal overall structure is not a static situation. Countries have shifted between being a confederal, federal, and unitary political system (for instance, Argentina, Germany, Mexico). More important, though, is that unitary and federal states vary in the degree to which they are centralized or decentralized (see Table 5.1). Following Ronald Watts (2008, pp. 171–177), a single dimension does not exist upon which the degree of autonomy of subnational governments can be determined. Instead, we need to consider several: legislative, administrative, and financial decentralization; constitutional limitations; and the nature of federal decision making. For detail on each of these dimensions we refer to Watts, but we shall provide some examples. For instance, the Netherlands is characterized as a decentralized unitary state. Close to 90 percent of local government revenue is dependent upon transfers from national government, but in every other respect Dutch municipalities have considerable autonomy.

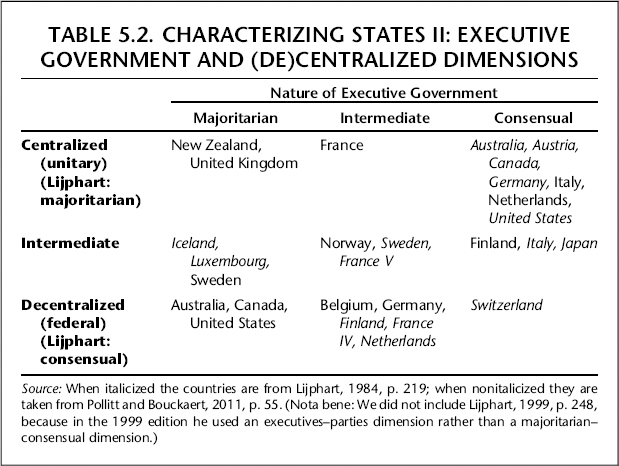

The distinctions between countries are not as clear-cut as may be suggested when looking at Table 5.1. For instance, since the Loi Deferre (1982), France has become more decentralized. Indeed, in any country the political-administrative system is to a larger or smaller degree always in flux. This can be illustrated by considering the reform capacity of various countries as Christopher Pollitt and Geert Bouckaert have done. The latter base their table loosely on Arend Lijphart's work (Lijphart, 1984, p. 219 and Lijphart, 1999, pp. 110–111 and 248), but look in Table 5.2 at the different positions of Australia, Canada, Finland, France, Germany, and Sweden when comparing Lijphart's characterization with that of Pollitt and Bouckaert. It is likely that there have been changes in the past 25 years, but there could be another explanation. Lijphart characterizes political party systems in terms of whether they are majoritarian, intermediate, or consensualist, and these characteristics occupy both the X- and Y-axes. Thus to Lijphart the most majoritarian countries are New Zealand and the United Kingdom, while the United States is listed as majoritarian-consensualist (the most consensualist is Switzerland). Pollitt and Bouckaert's X-axis holds the same three types of systems as Lijphart's matrix does, but their Y-axis emphasizes the degree of (de)centralization combined with the extent to which a country can be labeled as unitary or federal. In other words, Pollitt and Bouckaert actually developed a more insightful table by combining two dimensions (nature of executive government; unitary to federal system).

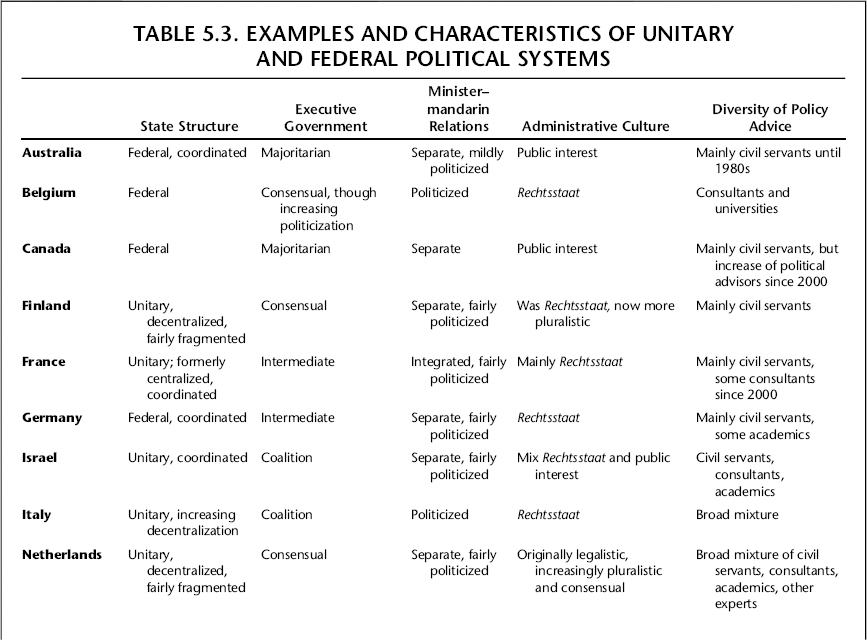

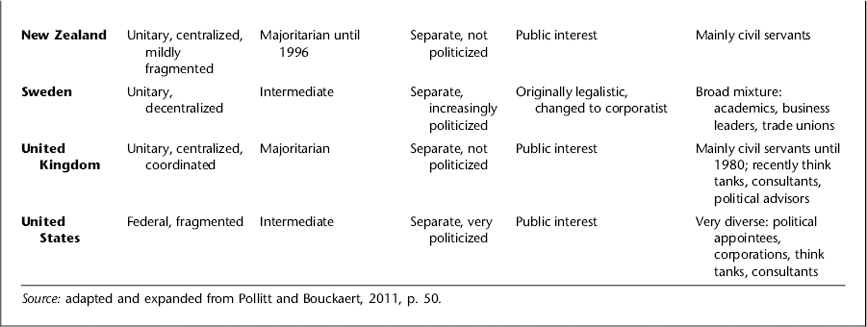

Political systems can also be categorized in terms of their ability to reform. Pollitt and Bouckaert distinguish five features of political-administrative systems: state structure, nature of executive government, political-administrative relations, dominant administrative culture, and degree of diversity of stakeholders who provide policy advice. In this chapter we focus on state structure and the nature of executive government. In Chapter 6 we address the administrative culture, while in Chapter 8 we will consider political-administrative relations and those who are involved in policy advice.

Pollitt and Bouckaert define state structure as the extent to which authority is shared between levels of government (the vertical dimension) and the degree to which policy is coordinated at the national level (the horizontal dimension) (2011, p. 51). In Table 5.3 you can see their characterization of each state as federal or unitary and as centralized or decentralized, but now including the degree to which they are coordinated. We have added Israel to this table and added “decentralized” to their assessment of the Netherlands. The second element of coordination concerns the extent to which one or two national government departments drive reforms. In that sense, for instance, the Netherlands is fairly coordinated (the Departments of Home Affairs and of Finance), but a variety of reforms have been spearheaded by the Council of State, top political and administrative executives, specially appointed state committees, and external actors (e.g., at the time of the French and German occupations, 1795–1813 and 1940–1945, respectively) (Van der Meer and Raadschelders, forthcoming). What is puzzling is that in their table Pollitt and Bouckeart label Germany as a coordinated system, but at the same time they argue (p. 54) that reform capacity is highly fragmented between a multitude of arenas and actors.

The second dimension Pollitt and Bouckaert discuss is the nature of the executive government, i.e., the cabinet, and they distinguish between four types:

- Single party, or minimal winning, or bare majority,

- Minimal-winning coalition where two or more parties have a little more than 50 percent of the legislative seats,

- Minority cabinets, and

- Oversized executives or grand coalitions.

This is in part related to the type of political party system. Majoritarian systems are generally two-party systems, while multiparty systems are by necessity more consensual. They find that speed and severity of management reforms decline when moving from the left to the right in Table 5.2. They also note that the scope of reform, which is defined as the amount of public-sector tasks and services that is affected by reform, declines when moving from the top to the bottom in Table 5.2. Itis thus that they conclude that deep and rapid structural reforms are less difficult in majoritarian countries. Also, the more centralized a political system is, the less difficult it is to pursue reform (Pollitt and Bouckaert, 2011, pp. 55–56). We need to keep in mind, though, that these conclusions only pertain to Western countries; it may well be that in centralized developing countries reforms are not so easy to pursue. And then, as they observe, there is variation among majoritarian countries as well. In the United Kingdom the prime minister has far more control over his party members in the legislature than the American president has (Pollitt and Bouckaert, 2011, p. 58).

Goran Hyden has also looked at the executive capacity or rationality of political systems but then in relation to their legality or rule conformity and situating entire world regions in his matrix. He characterizes Western Europe as strong in rationality/executive capacity and firm in legality; the United States as weak in rationality/executive capacity and firm in legality; Asia and Latin America as soft in legality but strong in rationality; and Africa and Eastern Europe as soft in legality and weak in rationality (Hyden, 2012, p. 605).

Typologies of Democratic Systems

Imagine living in a close-knit group and moving from one place to the next in the search for food. Such hunter-gatherer groups are, in a way, direct democracies. Everybody knows everybody else, and interpersonal conflict is settled within the group by noninvolved individuals. In sedentary societies, people quickly will no longer know everybody else, and it is then that institutions are created that help meet collective needs and adjudicate in the case of interpersonal conflict. While we discussed this already in Chapter 2, it is important to reiterate this. While for most of history the majority of people lived as mere subjects, it is in the last two centuries that they have become citizens who partake in indirect, representative democracy through passive and active voting rights. Since the Atlantic Revolutions people in democracies are considered equal in the eyes of the law. Obviously, they are unequal in a social sense and—chapeau Robert Michels—some will always be more powerful than the multitude. What is it that makes large-scale democracy work? Is it not amazing that in democratic societies with thousands, millions, and—sometimes—hundreds of millions of people, violation of private rights by government is actually quite limited? That is to say, it still happens but is considerably less than in earlier times or in nondemocratic states. Sure, superficially we could point to the existence of sanctioning systems, such as a police force and a judiciary; but no sanctioning arrangement can handle a society where everybody violates the law.

Hence, deeper down, there is something else about (liberal) democratic societies that actually makes them more fair and effective, and that is not an array of institutional arrangements but rather an individual attitude. And here it is fitting to quote Mill:

The only freedom which deserves the name, is that of pursuing our own good in our own way, so long as we do not attempt to deprive others of theirs, or impede their efforts to obtain it. [. . .] Mankind are greater gainers by suffering each other to live as seems good to themselves, than by compelling each to live as seems good to the rest.” (Mill, 1983, p. 72)

The reader may be more familiar with the following two quotations by Mill that can be found when googling the word “freedom.” The first: “I have learned to seek my happiness by limiting my desires, rather than attempting to satisfy them.” The second: “Your freedom to punch me ends where my nose begins.” (Nota bene: We tried to find the source of these quotes but were not successful.) Mill's observation is nothing else but a secular version of the Golden Rule: Democracy will thrive through self-restraint and is learned, not imposed. But how can societies get to that point?

Perhaps communal life within nomadic bands was/is relatively peaceful; the high degree of social control assuring that interpersonal conflicts will not get out of hand. But how can collective challenges be met and interpersonal conflicts settled when people start living together in ever-larger concentrations without knowing one another? The answer is that it is possible through the establishment of institutional arrangements that are structured around emergent and solidifying social stratification. The territorialization and bureaucratization of the world are top-down processes that work as long as people have not figured out how to create and maintain a large-scale self-governing system. From the extensive research done by Elinor Ostrom (1990) and many others in her orbit we know that people can govern themselves successfully, but only on a relatively small scale. The first large-scale experiment with democracy is that of the United States, certainly large in territory from its beginnings, and increasingly large in terms of population. The democratization of the world started in the late eighteenth century and has not stopped since. There were not many indirect and representative democracies in the early nineteenth century. By the early 1970s there were 39 democracies in a total of 150 countries (= 27.3 percent) (Diamond, 2002, p. 2; on p.58, Table 1, he lists 41 democracies). By 2002 this had increased to a total of 121 democracies among a total of 192 countries. This is as much a function of copying behavior, of multilateral donors desiring democratic reforms, as it is of normative diffusion through an underlying network of intergovernmental and international nongovernmental organizations (Torfason and Ingram, 2010).

That democracy has tripled by the early twenty-first century so that more than half of the world's countries can to a smaller or larger degree be labeled as a democracy is great, but these numbers do not tell the whole story. Even though the percentage of states rated as “free” by Freedom House increased from 29 percent in 1972 to more than 46 percent in 2002 (Torfason and Ingram, 2010, p. 59), the percentage of “illiberal democracies” has increased as well. Liberal democracies with fair, free, and frequent elections, with a rule of law, an independent judiciary, checks and balances of and upon (political) power, and with the protection of human freedoms accounted for a little more than 81 percent of all democracies in 1974, while only for almost 61 percent in 2002. In other words, “illiberal democracies” where human rights are not well protected, where there is corruption together with a variety of social and economic challenges, have increased (Torfason and Ingram, 2010, pp. 5 and 62).

Diamond (2002) mentions four possible reasons for the fact that democracy has become, in his words, shallower:

- deterioration of quality of governance and rule of law;

- diffusion of liberal democracy shows regional variation: complete in Western Europe and Anglo-American countries (100 percent), almost complete in East Central Europe and the Baltics (about 75 percent), a touch less than 50 percent in Latin America and the Caribbean, less than 30 percent in the Asia-Pacific region, a little more than 5 percent in Sub-Saharan Africa, and none in countries that used to be part of the Soviet Union (the Baltic states excepted). The Arab world has no true democracy, but we will have to wait and see what the outcome of the various uprisings will be;

- several political regimes that appeared to move toward democratic rule settled once more for a type of authoritarian rule (e.g., especially in African and former Soviet Union countries); and

- many of the democracies that were created after the fall of the Berlin Wall (1991) experience the same domestic (economic and political development) and international challenges (standing in the international community) as the newly independent states in Africa and Asia in the 1950s and '60s (Diamond, 2002, p. 4).

In light of Mill's insight, democratization is ultimately a bottom-up process. It is not possible to flip a switch in a population where the majority of people were subjects rather than citizens, or where people have only known totalitarianism and dictatorship, and tell individuals that “we have liberated you; as of today you live in a democracy.” In other words, the institutional arrangements for democracy that we briefly describe later stand or fall with the restraint of the individual. We will first focus on types of democratic systems in general, and then (in the next subsection) concentrate on the distinction between parliamentary and presidential systems.

A democracy can be established with or without a constitution. Many countries have a founding and compact document, but it is not necessary. A series of constituting documents will serve the same purpose; namely, that of grounding a country's government and citizenship in a set of fundamental laws. Two well-known examples are the United Kingdom and Israel (Lane, 1996, p. 7). Whatever the grounding document or documents, it is assumed that people in a democracy have a sense of homogeneity, of belonging together. In truly and sociologically homogeneous societies people share a language, a history, and an ethnicity. Now that many Western countries have experienced rapid immigration and have become less homogeneous, it is and should be in citizenship that we find a renewed, albeit more abstract, sense of homogeneity. Perhaps developing countries are less challenged in this respect and thus are still to a larger degree societally homogeneous. That may actually bode well for hopes of democratization. Now, to be sure, democracy can emerge in both homogeneous and heterogeneous societies, but that depends in the eyes of Gabriel Almond (1968, pp. 55–66) upon political culture and the differentiation of the political system. In his view, a homogeneous political culture is one where the citizenry agrees about the core political values and their priorities. He regards Anglo-American countries as the most stable because there are no serious cleavages in society and the political system is highly differentiated. While the political systems of Western Europe are as differentiated, they also have more fragmented political cultures. Cleavages can be based in religion (for instance, Catholics versus Protestants in the Netherlands and Germany; or religious versus secular Jews in Israel), ethnicity (for instance, African-Americans versus Caucasians), class (for instance, upper, middle, and lower classes in a society where social mobility is limited), and region (for instance, Flanders versus Wallonia in Belgium) (Lane and Ersson, 1989, ch. 2). Some countries have multiple cleavages (for instance, Belgium, Israel, Lebanon). As mentioned previously, we are inclined to think that Western countries have become less homogeneous as a consequence of immigration. This, though, does not have to be detrimental to democracy, and is not when political institutions are differentiated in a system of institutional arrangements that prohibits control of political power in the hands of one individual or body. The political system in Western countries is highly differentiated (see Section 3 later), while in preindustrial political systems—that is, before the late eighteenth century—and in totalitarian systems political power is concentrated in one person or institution.

It is natural that people associate with those with whom they feel affinity, with those with whom they have grown up. However, in societies that experience social cleavages as a consequence of immigration, it would behoove policy makers to advance policies that help people recognize and value what binds them together: citizenship. A sense of togetherness based in citizenship rather than other social ties is challenging and may even be under pressure as a function of growing income inequality in many Western and non-Western countries. Income inequality is increasing in many countries (Economist, 2012) with the United States leading the way. By way of example one can look at executive compensation in comparison to the wages of ordinary workers. In 1999, CEO compensation in the United States was 34 times that of employees; in the United Kingdom “only” 24 times; France, 15; Germany, 13; and Japan, 11 (Knoke, 2001, p. 264). Globalization, however, is reported to have influenced executive pay, in the sense that the difference between executive and employee pay has been steadily increasing.

It may seem that we have digressed from the theme of characterizing democratic systems, but one thing that practitioners and students of governments must be aware of is the extent to which democracy cannot be taken for granted. Michels' “iron law of oligarchy” may concern the concentration of political power only, but could be regarded as a specific example of a more general human condition: the instinct to protect oneself by whatever means and then potentially invade the freedom of others. Growing income inequality points to lenience toward greed and concentration of economic power as well as wealth. This is potentially dangerous to any democracy.

How democracies can deal with the potential of instability has been explored by Seymour Martin Lipset and Arend Lijphart. Lipset suggested that a society is more stable when its value system rewards individual effort and performance. He contrasts such achievement societies to ascription societies where people get ahead on the basis of birth or rank. Obviously, he regards the United States as an excellent example. However, and in light of our brief excursion into income inequality, we suggest that social mobility is much less possible today in the United States than in the past (Portero, 2012). Lipset also agrees with Gabriel Almond that social homogeneity fosters stability (1963, 1979). Lijphart convincingly argued that stability can be found in homogeneous and fragmented societies alike, but that it then is a function of elite behavior. In a deeply divided society as the Netherlands during the first six decades of the twentieth century, it was the elites who created consensus in the pursuit of political objectives, while people were segregated along religious lines. He suggested that his country was moving in the 1960s from being pillarized to becoming more like a cartel democracy (that is, a harmony model) where there are no political subcultures (1968, p. 229). In view of what we wrote in Chapter 4 about immigrant societies, we may well again see political subcultures, especially among those who cling to a sense of Dutch nationality versus those who seek to accommodate cultural differences.

Many democracies will have competing elites, but these will not threaten political stability as long as the elites recognize the need for consensus and compromise. Obviously, this is easier to achieve in consensual than in majoritarian systems, especially when elites have lost the art of consensus as appears to be increasingly the case in the United States.

Presidential and Parliamentary Systems

We can now extend our discussion previously about the executive capacity of political systems on the one hand and types of democracies on the other, to contrasting parliamentary and presidential systems, which are by far the two dominant arrangements in democracies. In a parliamentary democracy the functions of head of state and head of government are separated. The head of state is often a ceremonial function where monarch or elected president represents the country abroad. The real power rests with a prime minister who can either be elected directly by the people (Germany) or picked by the political party that has won the elections by number of seats (as in the Netherlands and in Israel). It is also the prime minister who forms a cabinet of ministers. In Westminster systems this is a cabinet based upon a majority in parliament (see Patapan and others, 2005); in consensus systems this is a cabinet where a coalition of political parties are represented since none can acquire an absolute majority in the legislature. By contrast, a presidential democracy is one where one elected official serves both as head of state as well as head of government. The United States is an example of a country with an extraordinarily powerful executive since the presidency not only combines head of state and head of government but also includes that of commander in chief (this is also the case in several Latin American countries). Lane and Ersson characterized France as a Westminster system, but that is because it is basically a two-party system where one party has a slim majority and holds the presidency as well as the prime ministership (1994, p. 72). France may actually be somewhat of a hybrid, a presidential-parliamentary democracy, since there is a directly elected president who then appoints a prime minister responsible for securing majority support in the legislature. The president also appoints the cabinet. The French Fifth Republic has also been called a semipresidential system since the cabinet can be forced to resign when a vote of no-confidence has passed the legislature. Another surprise could be Germany. It has an elected president, but it is a parliamentary system where the real political power is invested in the chancellor. An oddity in the contemporary world system is the fact that the British monarch is the head of state in 16 of the 54 states (most of which are former colonies) in the Commonwealth of Nations (nota bene: Elizabeth II is head of the Commonwealth). It is unclear how permanent this situation is, but the current (2013) prime minister of Jamaica, Ms. Portia Simpson Miller, has indicated a desire to find an indigenous head of state.

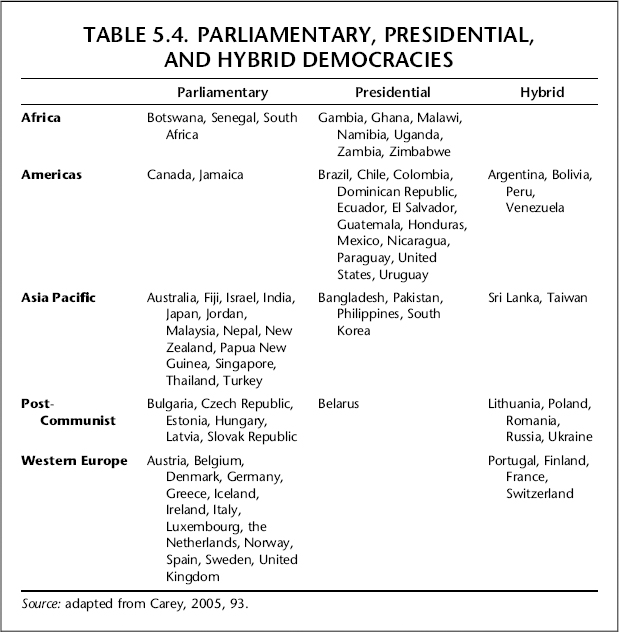

When counting the number of parliamentary and presidential systems listed in Wikipedia, the former seem to be a little more dominant, and this is visible in Table 5.4, even though it only contains 80 countries. It appears that in Asia and Western Europe a clear preference exists for a parliamentary system, while a presidential system is preferred in the Americas and Africa.

Party-Political and Bureaucratic-Prominent Systems

So far we have characterized political systems in fairly straightforward ways as unitary or federal, as majoritarian or consensual, as democracy or totalitarian, and as parliamentary or presidential. These dichotomous representations help as a first approximation of the nature of a political system but hide a much more complex reality that was ably categorized by Ferrell Heady in his distinction between party-prominent and bureaucratic-prominent political regimes. The following is based on Chapters 8 and 9 of his major study (2001) and we find that his subtypes of each greatly clarify why it is important that the study of public administration pays attention to the political context in which governments operate.

We will begin with the party-prominent systems. Heady distinguished between four of these. The first is the polyarchal competitive system. Essential to this model is political competition, and political change occurs without disrupting the system. This is characteristic for all those democratic systems discussed in the previous section and is found predominantly in Western Europe and the Anglo-American countries but would also include the Philippines and Sri Lanka. Polyarchic or democratic systems operate on either a parliamentary or presidential model, and most newly independent states in Africa simply adopted one of these two models from the former colonial ruler (Heady, 2001, p. 372). The second type is the dominant-party semicompetitive system, where one party has held a monopoly of power for a substantial period of time. However, other parties do exist and are legal. The dominant party is nondictatorial, and examples include India, Malaysia, and Mexico (Heady, 2001, p. 383). The dominant-party mobilization system is the third type, and in these there is less permissiveness in politics, actual or potential coercion is larger, and the dominant party is usually the only legal party. Examples include Egypt and Tanzania (Heady, 2001, p. 393). These first three types are quite common in developing countries (Heady, 2001, p. 371). Some African countries after independence experimented with communism, but it was not a great success. Finally, there are the communist totalitarian systems that have only one legal party, and a so-called parallel bureaucracy. This is the situation where the bureaucratic organization at each level of government is controlled and steered by its parallel level in the political hierarchy. This is also referred to as the Double Hierarchy Model (Mayntz, 1978, p. 77). Examples of these include China, Cuba, Laos, North Korea, the former Soviet Union, and Vietnam (Heady, 2001, p. 403).

The second major category Heady distinguished is that of bureaucratic-prominent systems where professional bureaucrats hold power directly or are indispensable to nonbureaucratic elites. Key policy-making positions are occupied by career government officials. A competitive party system never existed, is in jeopardy, or is superseded by bureaucracy (Heady, 2001, p. 313). This is the ultimate administrative state, one without political officeholders or where political officeholders and career civil servants have become blended (this is the pure hybrid of Image IV in Aberbach and others, 1981, pp. 4–16). In this type of system public officeholders are, as Hegel called it, the new guardians of democracy (for discussion of this see Raadschelders and others, 2015b, p. 367). As far as we know the true administrative state—that is, one without political officeholders—has never existed. The closest is nineteenth-century Norway where career civil servants governed but acknowledged the Swedish king as their head of state.

Heady identified six different types of bureaucratic-prominent systems. In traditional elite systems members of the political elites owe their position to the old social system. These are decreasing in number, and presently they are mainly found in the Near East and North Africa (mainly in Islamic countries) (Heady, 2001, p. 314). Heady distinguished two subtypes. The ortho-traditional system is largely traditional and aristocratic. The bureaucracy is relatively small and highly centralized. Its politics is geared toward system preservation. Examples include Iran before 1979 and Saudi Arabia (Heady, 2001, p. 315). At the beginning of the next chapter we shall see that this system is historically the most dominant. The second subtype is the neo-traditional system where traditional regimes change, but no effort is made to become a truly parliamentary or presidential system. This type of country has never been colonized, and bureaucracy survived and prevailed as a well-entrenched institution of power. This is a rare type of policy since the only example that comes to mind is that of Iran (Heady, 2001, pp. 316–321).

The second main type is the personalist bureaucratic elite system characteristic of the caudillo or strongman regimes in Latin America that were dominated by (mostly) military leadership (Heady, 2001, p. 321). We write in the past tense because, despite its “popularity” in the twentieth century, there are very few, if any, of these regimes left in Latin America. There have been some in Africa as well (for instance, Idi Amin in Uganda in the 1970s) (Heady, 2001, pp. 321–327). The caudillo regime is hierarchical by nature and thus differs from a junta, which is a collegial bureaucratic elite system—the third type—that used to be characteristic of many Central American countries, and of Greece between 1967 and 1974, Portugal 1974–1976, and Pakistan between 1977–1988 and 1999–2008. A junta is a collegial body of professional administrators, usually military officers, who exercise political leadership. They have often done so as an intermediate solution following a military strongman and preparing for civilian-military coalition bureaucratic regime (Heady, 2001, pp. 327–330). This type of regime has declined since the late 1990s and, as far as we know, the only two left are Fiji and North Korea.

The law-and-order regime, fourth, is a collegial military regime that is focused on the maintenance of political stability, and Indonesia is a good example of this type, at least until the late twentieth century. Since then Indonesia has been moving toward becoming a democratic system (Heady, 2001, pp. 330–335). The fifth type is where a change occurs from being a traditional elite to a collegial bureaucratic elite regime without an intervening colonial period. This is characteristic for what happened in Afghanistan (1973), Ethiopia (1974), and Thailand (1997) (Heady, 2001, pp. 335–341). There are, however, also examples of countries with this type of regime that had a colonial background and where continuity after independence was found in the administrative rather than in the political system (for instance, Ghana) (Heady, 2001, p. 341–346). Finally, sixth, there are the so-called pendulum systems of which the most significant feature of the political environment is that it swings between being a bureaucratic elite and polyarchal competitive regime. Examples include Brazil, Nigeria, and Turkey (Heady, 2001, pp. 346–358).

The Three Branches of Government and Core Features of Democratic Political Systems

So far we have written in this chapter about the major features of the political superstructure, and we will conclude in this section by briefly mentioning that the most common division of labor at the apex of the political-administrative system is that between legislature, executive, and judiciary (in that order), each of which is supported by bureaucracy. In this section we will briefly summarize the origins and features of this trias politica and will, next, in a little more detail discuss the main political features of how democratic systems function. The fact that political systems cannot function without bureaucracy, which has been called the fourth branch of power, warrants that we also consider the main features of bureaucracy (next section).

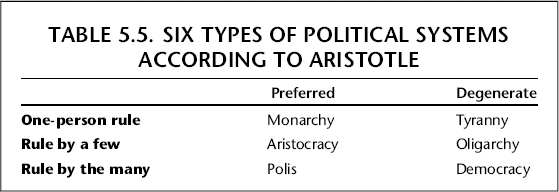

The various types of political systems described in Sections 2 and 3 earlier are descriptive of what can be found in the world today. The earliest categorization of political systems, however, dates back to Plato and Aristotle who suggested three types of systems, each with a preferred and a degenerate subtype (Table 5.5). To them, democracy was tantamount to rule by the masses or the mob. They would probably be surprised to find that, more than 2,000 years later, democracy is considered to be the most desirable type of rule and that it has, indeed, become the dominant one.

Democracy as we know it started to emerge in the United States and some Western European countries from the late eighteenth century on and diffused across the globe in the twentieth century. What Heady called “classic systems” of government and administration are those where democracy became the foundation upon which government-society relations were built (Heady, 2001, pp. 190–191), and examples include England, France, Germany, and the United States. In these classic systems a distinction between legislature, executive, and judiciary was enshrined in the Constitution or in comparable constitutional documents. This trias politica of political powers was first envisioned by Montesquieu, who built upon similar ideas of John Locke (Locke distinguished between legislature, executive, federative; the latter being concerned with foreign affairs). In this type of system, thought and intention (legislature), planning and action (executive), and evaluation of lawfulness (judiciary) rest in separate branches of one and the same state. Implicit in this three-way division of labor is that each of the branches has authority to check upon the other two. We need not discuss the varying degrees of such a check-and-balances system, but only need to be aware that in some countries it works out as overtly adversarial (and intentionally so) while in others it is more subtly embedded in the political system. Thus, in the United States, each of the three branches of political power holds constitutionally defined checks upon the other two. This is obvious for its legislature and executive, but perhaps less so for its judiciary. However, keep in mind that the justices of the U.S. Supreme Court have the authority of judicial review thus amending, correcting, or vetoing legislative action, and that judges in general can pass judgment on issues not addressed or even consciously left aside by the legislature. The power of judicial review also exists in Canada, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Germany, Hong Kong, Ireland, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Sweden, Switzerland, and Taiwan. This befits a political-administrative system with a common-law origin, which is a system where justice precedes law; that is, a system where jurisprudence is regarded as law. In many countries the highest court does not have such discretion; they are political systems with a Roman and/or statute law origin where law precedes justice; that is, where the legislature acts and sets the adjudicatory standards. Hence, in many countries it is the legislature that sets the boundaries (for instance, what is a civil and what is a criminal offense and what are the—usually—graduated sanctions?) within which the judiciary can adjudicate. To be sure, in practice statute law has come to dominate most states and their governments, irrespective of their common or Roman law origin. The United States is an excellent example of this development (Hurst, 1977). In many Western European countries and their colonies, statute law dominated much earlier.

At this point we emphasize, again, the importance of understanding the interplay between structure and functioning of governments. The structure of government is either categorized in terms of dichotomies or by means of typologies (see Sections 1 and 2 earlier). It is equally important, though, to know what actually makes them “tick,” and we shall rely once more on Heady (the following based on Heady, 2001, pp. 190–191). He listed five crucial elements of “classic” administrative systems. First, they have a highly differentiated system of government organization. The allocation of political roles is based on achievement rather than ascription, and they have a highly specialized bureaucracy. Second, these systems have procedures for making largely rational and secular political decisions. The power position of elites has eroded, and they operate upon an impersonal system of law. Third, there is ample evidence of extensive political and administrative activity in all major spheres of life. Fourth, political power is widely regarded as legitimate because the population at large identifies itself as belonging to and being part of the state. Thus, fifth, there is evidence of widespread popular involvement in the business of government.

None of these five elements or characteristics of functioning democracies would be possible without an alert, responsive, and responsible bureaucracy, and it is to their structure that we now turn. Again, we stress, that while the dominant focus in this chapter has been on political systems, since the early twentieth century no one can with reason omit the administrative system. This is why the first part of this chapter's title is “Political-Administrative Systems . . .”

The Structure of Government Departments

In the contemporary world no political system and its main branches can function adequately without bureaucracy (Vigoda-Gadot, 2009). In fact, this is the ongoing and puzzling paradox of democracy (as we know it) and bureaucracy (as we wish to have it). It is only since the late nineteenth/early twentieth century that bureaucracy is not simply a buttressing support to the political system, but has actually become vital to the survival of the political system. Heady (2001, pp. 190–191) distinguishes five features of bureaucracy in “classic systems.” First, bureaucracies are large-scale public services that develop and implement policies. Second, bureaucracies are highly specialized. That is, all governments have departments for clearly demarcated functions: defense, foreign affairs, treasury, home affairs, justice, and so on and so forth. Given the range and scope of government functions today, third, bureaucracies are also strongly professionalized. They employ people with widely diverging backgrounds, simply because they write law and pursue policy in a wide range of areas. They further seek people with high public-sector motivation (Perry and Wise, 1990) and those who are highly committed for public service, preferably for a long career. Governments initially employed people at the middle- and higher-level ranks when they had a law degree, but those days are long gone. We suspect that any degree that one can acquire at an institution of higher education is useful to some government function. Governments no longer only hire lawyers, but also theologians, musicians, philosophers, political scientists, sociologists, historians, physicists, chemists, geographers, engineers, agriculturalists, linguists, medical doctors, nurses, and so on and so forth. Fourth, bureaucratic officials (or, as we prefer to call them, career civil servants) play a fairly clear role in the political process. We will expand on that in Chapter 8, but here it suffices to say that the expert and experiential knowledge of civil servants has become indispensable to political officeholders. As a consequence, the difference between politics and administration has become blurred, to say the least. Finally, and fifth, bureaucracy in a classic democratic system is subject to effective policy control by political institutions and the elected officeholders who inhabit them. Sure, we know that career civil servants have exercised all sorts of tactics to trump political objectives deemed as untimely, costly, or “not done.” But we should also keep in mind that Max Weber's worry about democracy being overshadowed by bureaucracy has not come to pass. If anything, career civil servants in mature democracies have shown that they are able to set aside their personal interests for the common good. One cannot say the same of political officeholders!

If the previous statement holds truth, we should wonder why. Are career civil servants better at serving the common good than their elected supervisors? In general, this question cannot be answered, but there is at least one explanation for why the answer to this question may be affirmative. The answer lies in the fragmented nature of government bureaucracy itself. People tend to think of government as a monolith, a huge organization that, to a lesser or larger degree, oppresses the “natural” freedoms people have become accustomed to, and even believe themselves to be endowed with, but which only are part and parcel of humankind's understanding of politics since the late eighteenth century. It is no coincidence that “bureaucracy” as a concept came to be recognized (in the middle of the eighteenth century; see Albrow, 1970; Raadschelders, 2003, pp. 316–317) shortly before democracy came to be perceived as the desired political system. Bureaucracy was defined as a type of organizational system after the establishment of democracy (and we should add: in Western Europe; see next chapter). Bureaucracy in today's political-administrative systems is anything but a monolith.

Administrators and citizens alike know that “government” can be identified as the political party or political coalition in power but also as the set of bureaucratic departments that shore up the three branches of government. Generally speaking, people as citizens do not think of government bureaucracy as highly fragmented. And, it is in part because of that fragmentation of government bureaucracy that it has not superseded democracy. As it is, in most, and perhaps all, countries, government bureaucracies are compartmentalized in a variety of departments. Some appear to be generic, such as a Department of Defense, a Department of Justice, a Department of the Treasury, and a Department of Home Affairs. Nowadays, there are several other departments, often split off from the Department of Home Affairs, such as a Department of Education and a Department of Labor and Economics. Sometimes, government departments are established in response to a specific geographic condition, such as a Department of Water Management, or in response to an acknowledged and emerging need, such as a Department of the Environment. However, no matter what the origin and rationale of government departments, each country has several, if not many. We can look at these as if each one is part of that monolith, but that does not do justice to the extent to which governments have become specialized in response to various needs. Specialization in government structure is expressed through organizational differentiation; that is, through the various units that make up each department. While the three main branches of democratic governments usually operate as three collegial bodies, it is bureaucracy that is segmented according to task and function.

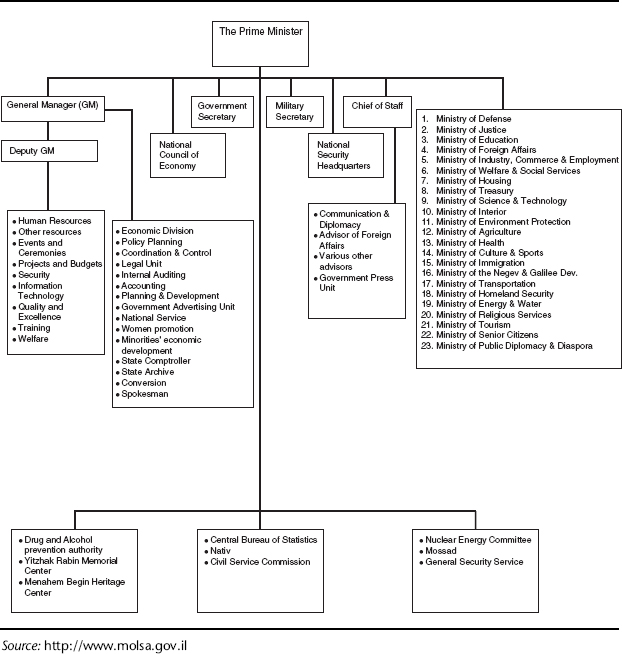

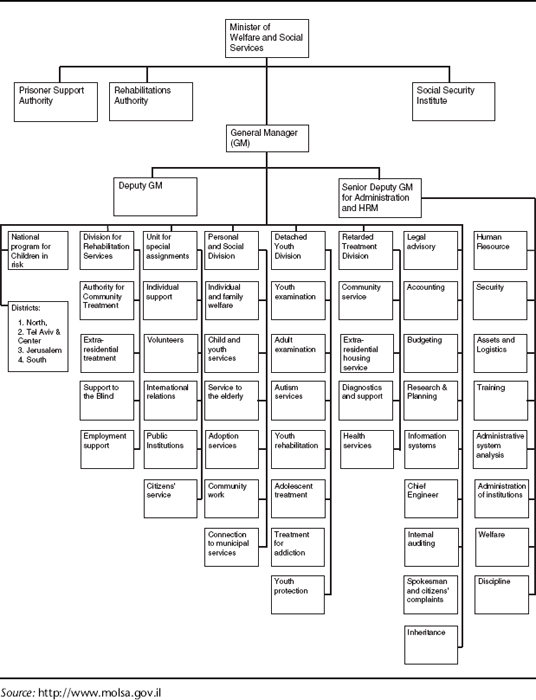

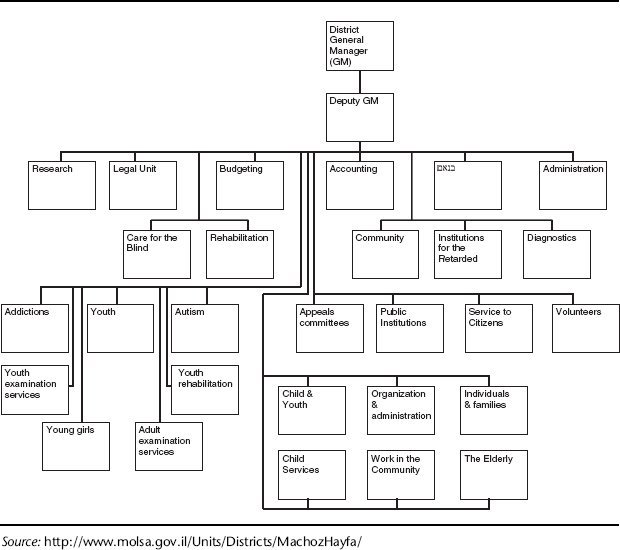

This segmentation of bureaucracy and its various subdivisions (i.e., departments and units within departments) is worldwide and cannot be better illustrated than by looking inside the organizational structure of a government's bureaucracy. Raadschelders (2011, pp. 83–92) showed how government bureaucracy breaks down into multiple units at each level of government in the United States. At the federal level, there are 15 government departments. For one of these, the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), he showed how it “broke down” into multiple subunits. He then showed how one of the subunits of DHHS, the Administration of Children and Families, is subdivided into multiple subunits itself. One of these subunits at the federal level, the Administration on Children, Youth, and Families, proved to be further fragmented into more subunits, while another of these federal subunits, the Region VI of DHHS, is also broken down into several subunits. The same pattern of organizational differentiation can be found at state and local levels in the United States. We expect that this pattern of organizational differentiation (i.e., of government bureaucracy consisting of thousands upon thousands of subunits) is found in most, perhaps even all, government organizations. By way of illustration, let us consider the state of Israel (see Figures 5.1, 5.2, and 5.3). As of 2012 this country had 24 government departments. We'll take the Department of Social Affairs and Social Services as an example (see later).

Previously we mentioned that the fragmentation of government bureaucracy is one of the explanations that help us understand why it has not superseded democracy. The answer now seems simple: Government bureaucracy is organizationally fragmented, and its career civil servants advance that part of a citizenry's interest that they are hired to protect. There is, we think, another reason, and that is that career civil servants have become, by and large (there are always exceptions), the new guardians of democracy to an extent that even Hegel could not have dreamed of. That, however, merits further consideration in Chapter 8. Meanwhile, there is one aspect of the political (-administrative) system that requires attention in the context of this chapter, and that is the fashionable notion of multilevel and multiactor government and governance.

Multilevel and Multiactor Government and Governance

In the previous section we showed how government bureaucracy is a multitiered or multilevel system with many different actors in each of them. That is, internally, government bureaucracies are multilevel systems. However, the concept of multilevel government (often abbreviated in the literature as MLG) and governance, with its many institutional and individual actors, emerged in the early 1990s (Marks, 1993), but is actually a phenomenon that has existed ever since governments established territorial levels (see Chapter 3). This happened historically because governments recognized this pattern as “an efficient response to the cost of communicating with a large number of people simultaneously. By sending a message to a limited number of persons, who each send the message on to a similar limited number of persons, and so on, a single person (or government) can communicate with a vast number of individuals in a few steps.” (Hooghe and Marks, 2009, pp. 228–229) There is, however, another important and more contemporary reason that multilevel governance has become a popular concept, and that is that it captures well the polycentricity of governance. While government is the only actor that has the authority to make decisions on behalf of the entire citizenry, it is not the only actor contributing to the governance of society. In other words, both the concepts of multilevel governance and multiactor government specifically acknowledge that policies are made and implemented in vast networks that include public-, nonprofit-, and private-sector actors (Van den Berg, 2011, p. 17; see for overview of the MLG literature, Enderlein and others, 2010). Multilevel government is a term that refers to central-local relations (in Europe) or intergovernmental relations (in the United States) and to relations between governments as sovereign actors and the multinational organizations to which they have declared membership. Indeed the concept emerged in the effort to describe the relations between the European Union and its member states.

FIGURE 5.1. THE STRUCTURE OF THE GOVERNMENT OF ISRAEL AND THE PRIME MINISTER OFFICE

FIGURE 5.2. THE ISRAELI MINISTRY OF WELFARE AND SOCIAL SERVICES

FIGURE 5.3. THE STRUCTURE OF THE NORTH DISTRICT OF WELFARE AND SOCIAL SERVICES

Liesbeth Hooghe and Gary Marks distinguish between two types of multilevel governance (2009, p. 234; see also Hooghe and Marks, 2003, pp. 236–239). Type I are general-purpose jurisdictions that combine problems with similar scale in one jurisdiction, are territorially nonintersecting, have a limited number of jurisdictions, and a fairly limited number of levels. Type II are task-specific jurisdictions that deal with separate nearly decomposable problems in discrete jurisdictions, are territorially intersecting, and can have unlimited numbers of jurisdictions. Examples include Chesapeake Bay Council, Dutch water boards, NATO, U.S. school districts, and the World Health Organization. Their types I and II of multilevel governance correspond to the distinction between general-purpose and specific-purpose governments, which we discussed in Chapter 3. Hooghe and Marks emphasize that in type I, citizens cannot but be members of the jurisdiction (the intrinsic community), while in type II membership is voluntary (the extrinsic community). Type I is characteristic for the unitary state, regions, metropolitan areas, empires, and international platform organizations (for instance, African Union, Catalonia, China, European Union, Flemish Community, Inca Empire, London, United States), while type II is more in line with federalism (see also Eaton, 2008). Related to federalism, there is a third reason that this concept is important: A federal structure of government is better at accommodating multination countries (see Bertrand and Laliberte, 2010). Excellent examples of this would include Belgium and Bosnia-Herzegovina. Finally, multilevel government is an apt concept in a world where administrative and fiscal decentralization have increased in the past 50 years or so (see Bird and Vaillancourt, 2008; Falleti, 2010).

However, how fitting the concept actually is has been contested. One criticism is that the concept is hierarchical, for it emphasizes levels of government. In that light it can be debated whether international bodies constitute a level of authority. More specifically, one author noted that the MLG concept and its two types reflect two very different entities. Type I truly represents multilevel government that is hierarchical by nature. Type II, however, emphasizes governance and is much more concerned with network (Faludi, 2012). A second criticism is that it is a more descriptive than an explanatory concept (Bache, 2008, p. 27). Finally, it is a concept that fits a neopluralist theory of the state that includes multiple competing interest groups; it is less fitting to describe the situations in authoritarian, clientelist, weak, and failed states (Stubbs, 2005, p. 73).

Concluding Remarks

In this chapter we described the overall political-administrative superstructure of governments across the globe. As Hooghe and Marks noted, “the evidence [ . . . ] reveals a surprising degree of universality in the territorial structure of government.” (2009, p. 238) However, the elements of this set of institutional arrangements are not static, for they are subject to change. The most dramatic changes in the past century have been those where populations demanded an end to totalitarian government and where their protests ushered in a more democratic system. This development is still ongoing (think of the Arab Spring). Democracy is a living and organic feature of modern societies that can only thrive when people show self-restraint and can act in the interests of the whole. However, in today's sedentary and densely populated polities, democracy cannot “live” without bureaucracy. And bureaucracy, too, is a living, organic element of the political-administrative system, always subject to change. Bureaucracy is a global phenomenon, but its features are specific to the societal culture in which it is embedded. The contents of Chapters 2 to 5 provide the foundation upon which we can probe more deeply into bureaucratic organization, culture, and functioning, and for that we turn to the next chapter.