APPENDIX ONE

STRUCTURAL SIMILARITIES—CULTURAL DIFFERENCES

The Need for and Development of Comparative Government Studies

It is in the nature of people to compare. Us—them, here—there, have—have-not, more—less. The daily and implicit comparisons we all make often spring from self-centered concerns or from stereotypical judgments. Elevating comparison beyond individual concerns and judgments is, among others, what scholars do and, as far as the study of public administration is concerned, is necessary for improving the understanding of government's role and position in society. Such comparisons have to be systematic and explicit about concepts, theories, methods, and even personal experiences that inspired us. Comparisons are also civilizing, for they help people to appreciate both others and other systems. Finally, comparison is humbling as well as elevating. It is humbling since it makes people aware that there is no objective yardstick with which, for instance, universal stages of the development of government or rankings of less and of more advanced democracies can be established. Social reality is simply subject to interpretation. It is elevating when people sense that comparison will get them closer to unraveling the global, structural patterns in the development of government in contrast to the differences in the processes of governing between various cultures.

In this appendix we will discuss the importance of comparative studies in a world that is globalizing. This approach is very different from existing comparative studies. Some authors focused on comparing bureaucratic and political structures (for instance, Heady, 2001; Bouckaert and Peters, 2010). Many concentrated on comparing public policies (for instance, Castles, 1998; Adolino and Blake, 2011; Krause and Smith, 2015) or public sector reform and change (for instance, Pollitt, and Bouckaert, 2000; Pierre and Ingraham, 2010; Kuhlmann and Wollmann, 2014). These types of studies are mainly empirical by nature and focus on the recent past and present, and compare individual countries. We know of at least one study that attempted to provide a conceptual map of comparative public administration and policy (Jreisat, 2002).

In this appendix we will first discuss the role and nature of comparisons in the social sciences (Section 2), followed by a section on the comparative aspect of the study of public administration. A separate section (4) is devoted to an overview of the development of comparative public administration from the beginning of the nineteenth century to the present.

The Function of Comparison in Society and in the Social Sciences

Often social scientists regard comparison as a method for developing generalizations about the social reality in which we live. Practitioners regard comparison as a method that helps improve their own activities, policies, instruments, and techniques by learning from “best practices” elsewhere. While the natural sciences are focused on universal “laws” (e.g., gravity, magnetism), the social sciences have to balance attention for that which is general and that which is unique. Hence, the natural sciences do not have a comparative element or approach, while the social sciences really cannot do without. This is certainly the case for the study of public administration. For instance, government and bureaucracy are global phenomena in terms of their overall structure, but how they function will vary with culture (see, for instance, Hofstede and others, 2010).

The nature and object of comparison in the social sciences has been debated often, and the intricacies of it have been nicely outlined by Czudnowski. His six observations about the use of comparative research clearly demonstrate the variety of opinions (1976, ch. 1). First, comparison can be regarded as a specific method alongside, for instance, the experimental, statistical, and case-study design (see also Lijphart, 1971, p. 682; Page, 1990, p. 439). Smelser pointed out that these four methods differ in their explanatory power (1976):

- the methods vary according to the degree to which the researcher actually exercised empirical control on the sources of variation in the variables at hand; related to this,

- the methods vary in the ease with which empirical control can be established by some sort of measurement; and

- the number of cases and variables may vary. That is, when studying only a few cases, many variables can be considered, resulting in “thick description.” When considering only a few variables, a large number of cases can be analyzed (large N).

All this relates to the second point Czudnowski made, which is that there are several methods of comparison that substantially differ from one another. This implies that general statements on comparison cannot be made. It follows, third, that there is no special method of comparison. In fact, each method is based on comparison. Research implies comparison. Scholars develop and use concepts for similar phenomena, and they often look for the extent to which these phenomena are similar or different. One of the fundamental requirements of research projects undertaken in the positivist mode is replicabilitiy, and that implies comparison. Fourth, Czudnowski also argues that comparison in the social sciences is often quantitative and represents as such a behavioristic approach. Statistical methods are then the most systemized type of comparison. It can be argued, though, that there are a lot of comparative studies that use qualitative methods. Fifth, some social scientists hold that a comparative method for a research project can substitute an experiment, although the outcomes are believed to be less precise than those of an experimental design. A final, sixth opinion about comparison that he lists is that it is impossible in the social sciences. Each system is unique, has its own culture, and interprets reality in its own way. This view is held by phenomenologists. We can also find, though, advocates of this idea among the constructivists. This view differs fundamentally from the other five since it rejects the possibility that the social sciences are able to provide general empirical knowledge.

Comparison as part of the pursuit of knowledge is of a very specific nature. More than a century ago the English scholar Edward E. Freeman argued in a series of lectures, published as Comparative Politics (1873), that the comparative method was the greatest intellectual achievement of his time (as referenced in Richter, 1968/69, p. 134). The promise of discovering universal laws through global and longitudinal comparison was hard to ignore in a time when “grand theories”' (Comte, 1830–1842; Darwin, 1859; Marx, 1859; Spencer, 1850) thrived. The challenge for the social sciences was to discover universal laws of society just as the natural sciences had done for the natural world. The idea that comparison in the social sciences was a necessary step if they were to emulate the natural sciences prevailed throughout the first half of the twentieth century.

In the second half of the twentieth century scholarly attention turned more toward finding regularities and co-opted quantitative-statistical methods and mathematical modeling in that pursuit. However, qualitative studies did not disappear. In fact, they seemed to gain in importance from the 1980s on, if only to get a better understanding of how policies “played out” in different national and subnational settings. Esping-Andersen's book is an excellent example of a qualitative study that provides understanding of differences between types of welfare regimes, useful to both practitioners and scholars. Match that with Goodin and others' more quantitative study on different worlds of welfare capitalism, and we get a more complete understanding of this uniquely twentieth-century phenomenon.

Comparison appears to be firmly rooted in the social sciences as is illustrated by such journals as Cross-Cultural Research: The Journal of Comparative Social Science (since 1973), Comparative Social Research (since 1983), and The Journal of Comparative Politics (since 1969); as well as by such organizations as the Comparative Research Network led by scholars from Finland, Germany, the Netherlands, and Poland; and the Interdisciplinary Centre for Comparative Research in the Social Sciences based in Vienna, Austria; and by comparative research projects such as that on comparative local government systems in Europe led by professors Sabine Kuhlmann and Geert Bouckaert. What is the status of comparative studies in the study of public administration?

The Importance of Comparison in the Study of Public Administration

People have compared throughout the ages and so have their governments. For instance, civil servants copied from each other particular administrative techniques such as double-entry bookkeeping and particular organizational structures to facilitate a division of labor in government departments. While the study of law and of political science both had a tradition in comparative studies, such was largely missing in the study of public administration. Indeed, Robert Dahl observed: “The comparative aspects of public administration have largely been ignored.” (1947, p. 8)

Are we in better shape more than 60 years later? Not if we are to believe one of the grand old men in comparative studies, Jean Blondel, who wrote: “If comparative government is valuable and indeed inevitable, why is the subject so little advanced and why does it raise so many difficulties and controversies? Is it only that so many aspects are insufficiently explored? Or is it also that there are inherent theoretical difficulties—some even claim that the goal of a truly comparative analysis of government is impossible?” (1990, p. 5) Befitting the positivist and behaviorist approach to social science, Blondel's goal is the establishment of generalizations and regularities in the studies of politics and government. After all, politics and government are universal phenomena and activities (Blondel, 1990, pp. 3–4). There is, of course, a major difference between a “universal law” and a “regularity.” Universal generalizations were the ultimate goal until the 1950s-1960s. Today scholars tend to settle for middle-range theories, although the hope for more general theories is not left behind. In the words of Blondel: “Middle range analysis can provide a basis for the development of comparative government, despite the fact that there is still no general theory of the relationship between norms, structures and behavior, of legitimacy, and of institutional development.” (1990, p. 359)

Since public administration in the Anglo-American world has often been part of political science, separate definitions of comparative public administration do not really exist in those countries. Macridis argued that comparative public administration and comparative politics are the same. Both are focused on political action, state and state agencies, civil service systems, legislation, the executive, the judiciary, civic culture, and infrastructure of the political world (1968/69, pp. 80, 82–83). It is a view still popular as is evident in one of the few articles that specifically addresses comparative public administration (Page 1995, p. 138).

Such an approach to comparative public administration is not very satisfactory in countries where public administration has strong roots in the study of (state and administrative) law, as is the case in most of the continental European countries. In the continental European tradition there is much more interest for bureaucracy as the expression of legal-rational government (Weber, 1980; Pierre, 1995). Since the study of public administration is concerned with structure (particularly organization), functioning (particularly processes), and functionaries (Van Braam, 1986, p. 4), and since public administration has both descriptive as well as normative pretensions, comparative public administration can be defined as the study of structures and processes in and ideas about

- governments as they exist around the globe,

- relations between societies and their governments, and

- the actual and ideal role and position of functionaries in these structures, processes, and relations.

Clearly the amount of comparative research has increased since the 1950s. The number of comparative books, however, is far larger than the number of comparative articles (Page, 1990, p. 445; Rose, 1991, p. 453). It is important to realize that some alleged comparative studies are not so much comparative as they are comparable. Comparable (often edited) studies present analysis of one phenomenon by several authors (for instance Page and Goldsmith, 1987; Dente and Kjellberg, 1987; Hesse, 1990/91; Rhodes and Wright, 1986). Single case studies in such journals as Governance or the International Review of Administrative Sciences also qualify as being comparable rather than comparative. Truly comparative studies are more often written by one or two authors.

What is the state of comparative research in the study of public administration? Looking at the quantity one could argue it is doing alright. Looking at the quality of many comparative publications, it is fine. But overall, comparative research suffers from being very fragmented in a geographical, substantive, epistemological, and methodological sense.

Geographical Fragmentation of Comparative Research and Understanding

Comparative research is geographically fragmented. Many small-N comparative studies are really single-case studies. Truly comparative small-N studies are often limited to a group of countries that are historically and geographically related, sometimes referred to as a “family of nations.” With regard to the Western world scholars often limit themselves to, as Ferrel Heady called them, the “classic” systems of France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, with the United States and Japan added. In this book we have discussed why these classic systems are often included.

Meanwhile, a good example of a “family of nations” approach is the study by Castles and others (1993) of Western democracies where he distinguished between an Anglo-American family (Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States), the German family (Austria, Germany, and Switzerland), the Latin family (France, Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain), and the Scandinavian family (Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden). Painter and Peters include the same four, but then in a larger classification that spans the globe: Anglo-American, Napoleonic, Germanic, Scandinavian, Latin American, Postcolonial South Asian and African, East Asian, Soviet, and Islamic groups of countries (2010, pp. 17–19). Let these two classifications sink in a little, because at first glance they make sense. Closer inspection and consideration, however, reveal several shortcomings.

First, geographic proximity, linguistic similarity, and cultural comparability are lumped together rather indiscriminately. The Castles et al. classification is basically one of geographic and/or linguistic proximity. Intuitively it feels right that the Anglo-American countries are lumped together because English is the dominant language, but that is where it ends (see the following). The Latin group has in common that its languages are Romanic (except Greece), that its countries were occupied by Napoleon (except Greece), and that they border the Mediterranean (except Portugal). The Germanic family is obviously both geographically and linguistically linked, although it is unclear where the French- and Italian-speaking parts of Switzerland should be placed. Surprising is the positioning of the Netherlands in the Scandinavian group. Perhaps the Scandinavian and Germanic countries should be grouped together because of geographical proximity and the fact that they all speak Germanic languages (except some parts of Switzerland) and are all in Northwest Europe. However, with regard to the Netherlands, the so-called Napoleonic tradition of centralized government has left as much influence as the Germanic Rechtsstaat tradition (Raadschelders and Van der Meer, 1995). So, does the Netherlands fit better the Napoleonic/Latin tradition or the Germanic tradition? With regard to the Latin tradition, Ongaro found that labeling these as “Napoleonic” is not very useful since “the expression does not entail that there is any kind of ‘Napoleonic’ heritage affecting the broader form of the state.” (2009, p. 7) Indeed, perhaps comparison should be focused on crafting carefully edited historical narratives that describe how the present came to be (Rouban, 2008). The reader will find more on this in Appendix 2.

Second, grouping countries as “families of nations” suggests a degree of comparativeness that at closer inspection does not exist. After all, culturally Canadians and Americans, for instance, are quite different people, as are Swedes and Norwegians. Another example is that one could study countries in the so-called Westminster tradition, but will then find that the development in various former British colonies has moved away from the initial British imprint and in quite a variety of directions (for instance, Patapan and others, 2010). In other words, at closer inspection the notion of “tradition” evaporates; it is a stereotypical shortcut to understanding, oblivious of national peculiarities, and certainly of subnational differences. In Germany, the state of Bavaria is quite different (Catholic) from that of Lower Saxony (Protestant); in the United States the Northeastern states that were settled by the British have a political-administrative tradition that is very different from that of the Southern and Southwestern parts that were settled by the French and Spanish, respectively (Elazar, 1966).

Third, and somewhat from a nationalistic point of view, the “family of nations” label is often modeled after one national example: the British and their Westminster system, the German Rechtsstaat system, and the French Napoleonic system. It just so happens that these three systems can be reasonably selected as “classic systems” (see Heady) but the reason why cannot be clear when the notion of “tradition” or “family of nations” looks at the contemporary world only.

This leads into the fourth problem with conceiving the political-administrative and cultural world in terms of “families” or “traditions.” They provide a rather static representation of the world, lacking a historical perspective that helps understand why we find, intuitively, both the conceptions of “families” and “traditions” appealing. To really understand the world of today, we have to trace its roots into the past. The “why” of today's world will never make sense without such a temporal perspective. Furthermore, what may be a tradition now can be less relevant 20 years from now. How long do we expect that we can speak about the Soviet tradition? A couple of decades? We certainly no longer speak about the Roman tradition (i.e., the part of Europe occupied by the Roman Empire), or the Catholic tradition (generally Southern Europe), or the Protestant tradition (generally Northwestern Europe), even though the influence of these “traditions” is much larger in today's world than generally realized (for more on this see Chapters 2 and 3).

The fifth problem is that any classification of nations based on geography, language, and culture emphasizes singular and, more often, a mix of features. Geographic proximity and linguistic similarity are somewhat clear as selection criteria, but why do Painter and Peters include a Soviet and an Islamic category? The first is a political category encompassing a hodgepodge of countries whose connection is that they once were part of the Soviet Union. Does that mean that the three Baltic states are in the same category as the Kyrghyz Republic? We must ask this because culturally and economically the Baltic states have been much more oriented toward Germany, Sweden, and Finland. Now that we're on this, in which category would Central European countries (for instance, Poland and Hungary) and Eastern European countries (for instance, Bulgaria and Romania) be placed, or former Yugoslavia and Albania? The latter two were not part of the Soviet Union but they were communist. Perhaps we should have a category titled Communist countries, but that would include China, which, from a cultural of point of view, fits better with a category of Confucian countries (Burns, 2007). We are not even going to try and reason that out. The Islamic category is obviously based on a religious criterion, while culturally the differences are quite significant. Indonesia, the largest Muslim country in the world, hardly compares to Iran with its more fundamentalist system of politics.

The sixth problem with this type of classification is that it leaves out much. As far as we know, all classifications of this sort are based on geographic, linguistic, and/or cultural features. Why is there no categorization from an economic point of view? In light of the globalizing economy, that would make sense. We suppose that the distinction between Western capitalist and non-Western, developmental could be one; industrial and agricultural could be another. But, then that would leave out the emerging and rapidly growing economies of, say, Brazil and India. The distinction between First, Second, and Third World is certainly no longer appetizing. Left out in the Painter/Peters grouping is the Middle East. In a geographic and linguistic sense they are one, but where does Israel fit? In which category are we going to place the small island states of the Pacific Ocean—that is, Micronesia—given the fact that some have been influenced by the British, others by the French, yet others by the Spanish or the Portuguese traditions?

Seventh, the notion of “tradition” or “family” actually highlights that there are regional pockets of comparative research that do not often connect with research in other parts of the world. There is, for instance, a lot of comparative work done in the Nordic countries, as there is in sub-Saharan African and in Latin American countries. Especially, scholars in the latter part of the world seem to be disconnected from their colleagues elsewhere (see also next subsection). Exchange of information and research is more often dependent upon relationships between individual scholars than upon a substantive basis. This takes us to a second source of fragmentation with regard to comparative research.

Substantive Fragmentation of Comparative Research and Understanding

There are several ways in which comparative perspectives are fragmented along substantive and topical lines: Western versus non-Western comparative studies, comparative studies within the specializations of public administration, comparative knowledge about governments across the social sciences, and ethnocentric and linguistic barriers to comparative understanding.

First, there is clearly a difference between Western comparative administration and non-Western development administration. Naturally, it is believed that we can learn from one another, but it does seem that when it comes to comparative research, it appears that development administration is perceived as learning from Western comparative administration rather than the other way around. In a really cynical mood one could say that there are very few Nigerian, Thai, or Argentinian consultants actively helping the European Union or NAFTA with some of its challenges. But Western consultants, as academics, as representatives and members of think tanks, and as civil servants, are frequently invited to reflect upon, discuss, and outline solutions for specific, often wicked, problems in developing world countries.

There are at least three reasons that exchange of comparative understanding is mostly a one-way street. First, former colonies in Africa and Asia received substantial development aid from their “mother” countries (Bivin-Raadschelders, 1995), including advice in institution building (for instance, how to incorporate indigenous governance traditions in a colonial system) (for more on this see Chapter 3). Therefore, there is something of a tradition with regard to exchange of information and experience. Second, members of the Comparative Administration Group (see more on them in the next section) wanted to study both Western and non-Western countries, but the Ford Foundation only provided funding for, as they called it, “development administration.” (Riggs, 1976, p. 649) Especially, American scholars swarmed out over the globe, to help rebuild European and Asian countries after the Second World War, and to help fledgling new states after decolonization (Africa, southern Asia) and independence (Central and Eastern European countries) (perhaps we could label the latter process as one of de-Russification). Third, especially in the past 20, perhaps 30 years, multinational donors such as the International Monetary Fund and World Bank have been more and more insistent that developing countries should adopt Western-style reforms if they desire financial aid (Adamolekun, 1999; Farazmand, 1999). While understandable perhaps at some level (for instance: assuring that financial aid truly reaches the intended populations), at another level it is much less understandable. Thus, and from quite an unexpected corner, the organizational theorist Howard Aldrich observed decades ago that “innovations have failed when introduced into societies with nonsupportive cultural and institutional traditions.” (1979, p. 22) We suspect that many a consultant will concur, but this insight does not seem to trickle upward to actually help redefine policy.

Is it so outlandish to consider the possibility that Western countries can actually learn from non-Western countries? One of the authors of this volume recalls reading Merilee Grindle's comparative volume about implementation in Latin America. Being “raised” in a Western, linear perception of policy making (from problem identification and definition, via identification of alternative solutions, selection of most satisfying alternative, decision, planning, implementation, and evaluation), it was eye-opening to read about the extent to which implementation is much more central to the policy-making process than in most Western countries (1980, pp. 5–7) and that, consequently, the policy focus is much more on the output stage than on the input stage of the policy process (Grindle, 1980, p. 15). In view of the fact that several scholars have pointed out the limitations of linear conceptions of policy making, and suggesting that cyclical approaches may approximate reality better, it does seem that we can learn from experiences in the developing world.

A second reason for the substantive and topical fragmentation of comparative studies is basically reflective of the topical fragmentation in the study of public administration. This problem is significant in the United States where the study is generally presented as a string of specializations. In the more European and Asian traditions of the study it is more common to present comprehensive perspectives or frameworks (Raadschelders, 2011b). Ask the question though: How many specialists in budgeting, finance, and taxation have read Peters's 1991 comparative study of taxation, and how many have read Webber and Wildavsky's cross-time study of the same (1986)? Would specialists in human resource management (HRM) have the time and/or desire to read on comparative taxation? We can also ask: As central as HRM is to any political-administrative system, how many truly comparative studies exist that present differences and similarities of HRM practices across the globe? The closest we get are studies published under the auspices of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Yet another question: How many specialists in HRM are interested in delving into the extensive comparative literature on administrative reform, or civil service systems, or new public management trends, or performance management and measurement? And how many specialists in defense policy would be interested in comparative health care (Altenstetter and Björkman, 1997)? If scholars operate in compartmentalized worlds of knowledge, there is no reason to believe that practitioners are any different (Raadschelders, 2011b, especially Chapter 3). While we know that in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries American, European, and Japanese civil servants traveled to other parts of the world to learn about best practices, and while we know that such travel is still fairly normal for upper-level administrative officeholders, are these public officials aware of comparative studies relevant to their trip, i.e., to be read before their trip? Other questions are conceivable, but the point we try to get across is clear: Comparative studies are hindered by substantive and topical fragmentation.

A third source of fragmentation is that comparative knowledge about governments exists across the social sciences, but again, that knowledge is mainly accessed as a function of a particular interest. Thus, a public policy scholar interested in trends in economic policy may find some neo-institutional economists inspiring (for instance, Douglas North, Oliver Williamson), while an HRM scholar might find more of interest in organizational sociology or in behavioral psychology.

A fourth and final source of substantive fragmentation is found in ethnocentric and linguistic barriers. Countries with which the authors of this volume are familiar (mainly Western Europe, North America, Southeast Asia, Western countries including Israel) often have a clearly defined national study of public administration (certainly in Western Europe and North America) or—at least—a study that is seeking to become more aligned to national, indigenous traditions. With respect to the latter situation (think of former colonies and the former Soviet countries), the case of the South Korean study of public administration is a good illustration. Many South Korean scholars received their education in the United States, and obviously, the Republic of South Korea was the recipient of much American aid in the aftermath of the Korean War (1952–1954). The South Korean study of public administration became something of a carbon copy of its American example, both in terms of substantive interest as well as in terms of favored methodological approach. It is only in the past 10 years or so that South Korean scholars have suggested that their study should be indigenized (Chung, 2007; Jung, 2001; Jung, 2014), and indeed, there is every reason to believe that the South Korean study can and should position itself intellectually and culturally as a system of Confucian governance (Liu, 1959, p. 213; Burns, 2007, pp. 72–73).

Another element or aspect of this ethnocentricity has to do with the domination of American literature in the study of public administration. This is not something that American scholars can or should be “blamed” for. After all, they are not translating their own hand- and textbooks in Chinese, Korean, French, or Spanish, just to name a few languages in which American hand- and textbooks have been translated. But, why has a Chinese textbook or one of the excellent Dutch, German, or French textbooks not been translated in English? (Raadschelders, 2009, p. 14) Could it be that such textbooks would not be used in, say, the English-speaking world because public administration scholars might find them not applicable in, for instance, the United Kingdom or the United States? If so, why are American textbooks considered relevant for understanding Chinese administration and its long and rich heritage of more than 2,000 years? (Balasz, 1957, 1959) Naturally, people, organizations, and institutions will never stop learning, but again, it is odd—to say the least—that American literature is so influential in other countries. It is especially odd because the American literature has very few references to non-American and non-English sources (Candler and others, 2010, p. 840), but this could be a function of the fact that American scholars generally will know their own system best and do not presume to be qualified using literature from other countries without understanding the cultural context in which it was generated (Raadschelders, 2011a, p. 148).

American influence in the study worldwide is partially a function of its effort and desire to help bring or revive democracy. American experience and scholarship introduced a system of judicial review in Germany and Japan in the late 1940s, created a federal system in Germany, and more recently, American experience with decentralization served as example for comparable efforts in South Korea (Jung, 2005, p. 421). Americans also imparted a specific outlook on and approach to scholarship in many countries (for more on this, see the next subsection), preferring empiricism, rationality, efficiency, quantitative-statistical analyses, and mathematical modeling.

Again, English-speaking (especially American) scholarship cannot really be charged with guilt when it comes to dominance. Up to four centuries ago the only scholarly language was Latin. In the course of the nineteenth century anyone who desired to study, for instance, physics or chemistry better become fluent in German, while someone interested in history, anthropology, or archaeology better be conversant in both French and German. To this day, several Italian scholars of public administration have mastered English, French, German, and Spanish, if only because they cannot otherwise become familiar with developments elsewhere. Until well into the 1960s, Dutch children in the nonvocational secondary schools at least learned English, French, and German, while several would also pick up five to six years of Latin and Greek. Several Israeli and Arabic scholars can easily access sources in each other's languages. Such multilingualism may be disappearing since, after the Second World War, the English language has become the lingua franca of the academic world. Thus, linguistically public administration scholarship written in languages other than English is not accessible unless a scholar takes the time to learn another language. Not all is lost, though. There are PhD programs and topics that require students to develop proficiency in one or more foreign languages, especially when that is regarded as an indispensable element of the toolkit a student needs to have in order to successfully complete a study of development aid (lots of French literature), a comparative study of policy making, or a comparative study of indigenization of civil service systems in Africa, just to name a few examples. And that leads us to the third main reason that comparative research and understanding is fragmented.

Methodological and Epistemological Fragmentation of Comparative Research and Understanding

Comparative studies are also fragmented along methodological and epistemological lines. With regard to methodology there is a big gap between quantitative-statistical and qualitative or figurational approaches (see the following). The large N-studies are done on the basis of quantitative-statistical analysis of extensive data sets, hoping that the data are coherent and consistent. Less attention in such studies is given (a) to the societal environment in which an organization operates and/or a policy unfolds, (b) the collection rationale for data from different countries, (c) the concepts that underlie these statistical tools and techniques (Desai, 2008), and (d) the variety of interpretations to the study concepts and methods that various people from various cultures sustain. Reviewing the first two issues of the Administrative Science Quarterly, the economist Kenneth Boulding observed that “the principal danger of the [quantitative-statistical] method is that the investigator is so absorbed in analyzing data that he forgets entirely the situation out of which the data are abstracted.” (1958, p. 16) He called this “data fixation,” and half a century later it seems that this is even more of problem.

Qualitative or figurational studies pay close attention to the societal and historical environment and thus can provide in-depth and detailed understanding of elements/aspects of a political-administrative system. As mentioned above, much research of the qualitative bend concerns often one country, or a few related countries. There are several reasons for this. First, while quantitative studies can be done without knowledge of other languages, “thick description” is not possible without accessing sources in another language. Second, many public administration scholars will be most familiar with their own political-administrative system and even see them as better or superior to others in an (un)conscious manner of ethnocentrism. How many scholars are there who can claim to have the in-depth knowledge of and experience in (that is, “living the comparative perspective”) another country than their own? Third, qualitative work takes time and money. It takes time to get to understand a particular system (that is, organization, policy, functionaries, and so on) before we can start research. It takes money to go and settle somewhere long enough so that research can be done that is of the same quality as that which one did in the home country. Perhaps, though, the fourth reason is most important, and that is that comparative research by definition deals with huge numbers of different constellations of situational and institutional factors (Ostrom, 2005, p. 10).1

It seems to us that combinations of quantitative and qualitative work are not very common, but would most definitely be important for comparative studies. That this is possible is illustrated by the work on common pool resources management systems by Elinor Ostrom and many associates all over the globe.

The methodological gap between quantitative and figurational studies is in part fed by a conceptual difference between “science” and Wissenschaft that has epistemological consequences (Raadschelders, 2011b, 40–42; see also Almond, 1990; Blyth, 2011; Popper, 1973). For centuries Wissenschaft2 was defined as an organized body of knowledge. In the course of the eighteenth century, and under the influence of David Hume's distinction between fact and value, the concept of “science” came to be more narrowly defined as a body of organized knowledge that is established according to specific methods and approaches and that focused on “facts” and assumed an objective reality that can be observed independent from the researcher's biases. This more narrow definition of science reflects and is relevant to the nomological frameworks and paradigms that exist in the natural sciences. Following the breathtaking breakthroughs in the natural sciences, various scholars came to believe that universal laws must exist for social phenomena as well, and so the call for a more scientific social science gained quite a following during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This is especially reflected in a preference for and use of quantitative-statistical methods and mathematical modeling when analyzing social processes in the belief that this is more scientific than, for instance, various postmodern approaches.

In the past two, perhaps three decades, scholars in various social sciences have come to question this limited approach to and definition of scholarly knowledge since it does not acknowledge that reality, and the perception of it, is socially constructed and that scholars do influence what they investigate (as, by the way, physicists by and large have accepted following “Schrödinger's cat,” one of the famous thought experiments in the 1920s and 1930s). Presently it seems that scholarship is either created on the basis of “science” narrowly defined, or upon a broader definition of science. Is it inconceivable that comparative research and understanding would benefit from work that actually combines both, and that departs from the notion that we can know parts of reality more or less objectively, while we also acknowledge that reality is socially constructed to varying degrees? In other words, do scholars really have to make a choice for either extreme on the continuum of knowledge?

One more interesting and puzzling aspect of scholarship narrowly defined is that it seeks to establish epistemological boundaries. The current division of studies in the academy dates back to the middle of the nineteenth century when several German universities determined that bodies of knowledge had to be organized in disciplines. That worked quite well for a while, but it is interesting that natural scientists since the 1930s have increasingly moved toward interdisciplinarity (that is, many of the big questions in the natural sciences can only be answered on the basis of interdisciplinary research), while the social sciences seem to be moving more to disciplinarity even though their bodies of knowledge can less easily be demarcated from one another (see on this Raadschelders, 2011b) than is the case in the natural sciences. Public administration is by definition an umbrella study, serving as the natural home for all that research and knowledge about government that is generated in the various social sciences. One could then call it an interdisciplinary study (Raadschelders, 2011b), but a case can actually be made that the study of public administration, and so its comparative component, cannot help but include an a-disciplinary source of knowledge.

Inter- and a-disciplinary comparative study will also help to reconnect practitioners and academics. The most important and challenging problems in the social world that confront practitioners are “wicked problems.” Traditional disciplinary approaches cannot be expected to provide an answer to these, simply by virtue of the fact that they seek to simplify a problem to a clearly demarcated, manageable, and thus analyzable level. Complex, “wicked” problems are multifaceted and therefore require an approach that draws upon multiple disciplinary knowledge sources, but also upon the input and experience from involved practitioners, citizens, etc. Complex social problems can be fruitfully addressed through an interdisciplinary approach (see Balint and others, 2011).

The Development of Comparative Public Administration

Comparison has always been regarded as important. In antiquity philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle, as well as the historian Herodotus, drew upon their comparative knowledge of the world as they knew it (Richter, 1968/69, p. 131). The same was the case with Ibn Khald![]() n and his Muqadimmah published in 1366 (2005), and more generally with the Fürstenspiegel published during the late Middle Ages and Renaissance (for instance, Machiavelli's The Prince). More systematic comparative research of political and administrative systems emerged during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. This occurred especially in France and the German principalities, since these were systems where the state had become a “consolidated state,” to use Tilly's phrase. Comparison was necessary in the late Middle Ages and the early modern times, since in many European countries Roman law existed along with customary law (Richter, 1968/69, p. 141). Jean Bodin compared on a massive scale, and Hugo Grotius, Von Pufendorf, Althusius, and Montesquieu all acknowledged their debt to Bodin's work (Richter, 1968/69, p. 144). Comparison was thus pursued both from a juridical/legal and an administrative science angle, and mainly for utilitarian reasons. For much of history comparison was pursued with an eye for usable knowledge of a very practical nature.

n and his Muqadimmah published in 1366 (2005), and more generally with the Fürstenspiegel published during the late Middle Ages and Renaissance (for instance, Machiavelli's The Prince). More systematic comparative research of political and administrative systems emerged during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. This occurred especially in France and the German principalities, since these were systems where the state had become a “consolidated state,” to use Tilly's phrase. Comparison was necessary in the late Middle Ages and the early modern times, since in many European countries Roman law existed along with customary law (Richter, 1968/69, p. 141). Jean Bodin compared on a massive scale, and Hugo Grotius, Von Pufendorf, Althusius, and Montesquieu all acknowledged their debt to Bodin's work (Richter, 1968/69, p. 144). Comparison was thus pursued both from a juridical/legal and an administrative science angle, and mainly for utilitarian reasons. For much of history comparison was pursued with an eye for usable knowledge of a very practical nature.

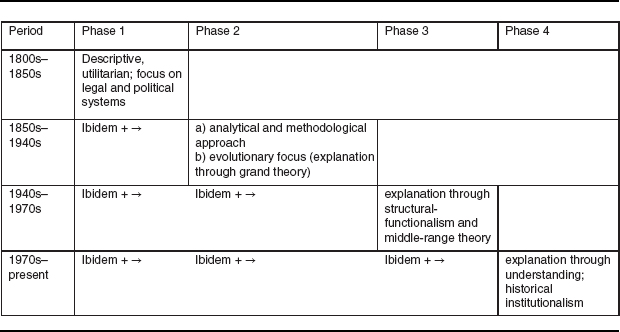

It is not until the ages of rationalism, Enlightenment, and the Atlantic Revolutions that comparison became driven by a need to unravel the assumed regularities of social change, following—in that pursuit—the leaps that the natural sciences had made and would continue to make with regard to universal laws in nature, much to the chagrin of some social scientists. Since the 1800s the development of systematic comparative study can be summarized in four accumulative phases (see Figure A1.1).

During the first phase, the 1800s to the 1850s, comparisons were mainly descriptive and utilitarian, and predominantly focused on law and political systems. The comparative notes in The Federalist can serve as an example, as can the early nineteenth-century studies of legal systems in Western Europe and of legal and political institutions in the United States. Upon the demise of absolutism and with the advent of attention for law and civil rights, attention shifted at the end of the eighteenth century to the analysis of constitutional structures and constitutional arrangements (Raadschelders, 1994, p. 117). The “rule of law” (Rechtsstaat) became an important subject of study and—as can be expected—especially so in the continental European states with their Roman law tradition. The study of public administration, which had been independent (think of Cameralism), now became part of the study of state and administrative law. Especially in France and Germany, there was much attention for legal arrangements in adjacent countries.

FIGURE A1.1. DEVELOPMENT OF SYSTEMATIC COMPARATIVE RESEARCH IN PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION

In the second phase, between the 1850s and 1940s, two somewhat separate streams of research emerged, one with an analytic-methodological and another with a social-evolutionary angle. The object of study was still that of legal and political systems. Examples of work with a more methodological and analytic focus are those of John Stuart Mill on methods of comparison and of Max Weber on, for instance, the use of ideal types. Weber's method of ideal types and theories about rationalization received much attention from the beginning of the third phase; Mill's methods of agreement and of difference did not really make it into mainstream social scientific comparison until the fourth phase. The flavor of late nineteenth-century comparative scholarship is best appreciated in one author's own words:

Our own institutions can be understood and appreciated only by those who know somewhat familiarly other systems of government and the main facts of general institutional history. By the use of a thorough comparative and historical method, moreover, a general clarification of views may be obtained. (Wilson, 1892, p. xxxv)

Woodrow Wilson was hardly interested in studying the evolution of American state and local government in the manner popular at Johns Hopkins in the 1880s (Hoffman, 2002). He was more captivated by “the grand excursions amongst imperial policies . . .” (as quoted in Hofstadter, 1974, p. 319). His 1892 study (initially 1889) shows that he did not mince words and that he looked for the unique elements of American government as well as for some of its roots in England, in medieval Europe, and in antiquity. In its time his work was methodologically rigorous and explicit in outlining a theoretical and normative framework. Unlike so many in the nineteenth century, Wilson used comparison to enhance understanding, not to add his own evolutionary theory to those that had been developed earlier.

Evolutionary theory was much more popular, though, and driven by the expectation that it would be only a matter of time (think of E.A. Freeman in 1873) before scholars expected to have discovered universal social laws. Global and longitudinal comparisons, being the greatest intellectual achievement, were considered the best vehicle to arrive at that point. With respect to social evolutionary studies we can think of, for instance, Auguste Comte's theory about the stages of intellectual development as indication for social change (from theological, to metaphysical, to positive stage) and Karl Marx's theory on the deprivation of the masses and the inexorable march toward socialist society. Especially the evolutionary approach to social change, teleological by nature and embracing a unilinear view of history, aimed at uncovering the major stages in the history of civilization and the presentation and selection of information, was guided by “grand theory.”

Characteristic for nineteenth-century comparative research was a stamp-flag-coin approach (Peters, 1988, p. 7), also known as the itemistic method in which comparison of institutional details is pursued item-by-item (Lasswell, 1968/69, p. 8). Cross-national comparisons dominated (see Appendix 2) and focused mainly on national levels of government. The comparison was not only performed for theoretical reasons. Indeed, practitioners actively pursued information about “best practices” elsewhere.

Often information was collected elsewhere with a view on assessing its usefulness for the national administrative system. The civil service report written by Dorman Eaton (1881) for the U.S. government is an example. He spent time in London to study the Northcote-Trevelyan report of 1854 and its impact upon the British civil service. (On a side-note: He funded the trip himself.) Upon return he adapted their ideas to the American context (Raadschelders and Rutgers, 1996, pp. 84 and 87). Trips abroad to learn about best practices were common. Quite a few American practitioners traveled to Europe to learn about the extent and structure of service delivery in an age where people demanded more government involvement (Saunier, 2003). Furthermore, many an American academic had received his doctoral training in Europe (Hoffmann, 2002). Japanese practitioners traveled all over Europe, copying elements of the British postal system, the French judicial system, the American primary school system, and the French and German army systems; the Bank of Japan was modeled after the Belgian example (Westney, 1987, p. 13). Not only did Japanese civil servants copy what they thought to be best practices, they also hired 2,400 foreigners from 23 different countries in Western Europe and the United States.

To our knowledge, middle- and higher-level civil servants still actively exchange practices and experiences with one another. Higher-ranking line officials (at the rank of director general, director) will be more interested in how particular policies are organized, structured, and implemented elsewhere, or in the extent to which a particular type of reform fits in their own national context. Middle- and higher-ranking policy bureaucrats are likely to pay more attention to the “fit” of a particular policy in their own national context.

Whether for intellectual or utilitarian reasons, the stamp-flag-coin approach is still important. Any comparative research project will have to “map” the topic in these descriptive terms. Nowadays much basic information is available through databanks and through the statistical yearbooks of various countries. Also, one can look for cross-national comparisons made by international organizations such as the OECD (Public Management: OECD Country Profiles) and by newspapers such as The Economist.

In the first half of the twentieth century comparative research was mainly limited to the study of state and administrative law. Public administration hardly existed as an independent study. In some countries, though, the study experienced a revival as a consequence of the growth of local government. This was especially the case in Germany, the United States, and the Netherlands. These local government studies laid the groundwork for what was to become modern public administration. And it was in local government studies that a comparative approach was again adopted (in The Netherlands for instance: J. In ‘t Veld, 1929).

The Second World War represented a watershed in the development of public administration. What increasingly bothered scholars in the twentieth century was that the methodological challenges to empirically falsify the grand theories of nineteenth century were monumental, if not impossible, to overcome. This motivated the development of “middle-range studies,” the third phase. In the decades of the 1940s-1970s a more modest middle-range theory was pursued. This type of theorizing was rooted in carefully explicated structural-functionalist conceptualizations. Prime examples of comparative work in that approach are the studies by, for instance, Shmuel Eisenstadt (1957, 1963) and by, more recently, Samuel Finer (1997). On both sides of the Atlantic the rather formal and mechanistic approach to public administration was left for more attention for the behavior of actors and of institutions. It was also acknowledged that constitutionalism was mainly limited to the Atlantic area, and that many countries were governed on a nonconstitutional (that is, nondemocratic) basis. The idea arose that government is a “system” and that the various institutions in that system are related to one another in terms of the functions they fulfill. In order to come to understanding, scholars now started to pursue grand taxonomies: a systematic classification of phenomena through defining concepts and the relations between concepts. The focus turned to the analysis of political-administrative systems both of the Western and the non-Western world (Eisenstadt, 1963; Wittfogel, 1957; Riggs, 1964; Heady, 1991). Comparative public administration dealt with political-administrative systems and, thus, with the “authoritative allocation of values;” hence the scholarly attention for policy making and implementation both in terms of its material (distribution and allocation of goods) as well as its moral dimensions (decisions about what is and what is not allowed). The emphasis was on institutions such as parliaments, political parties, and interest groups and so was mainly comparative political science.

In the 1960s and early 1970s a growing number of researchers became discontented with taxonomies since they resulted in rather static and descriptive studies. In these decades, the social sciences (especially in the United States) adopted a more quantitative approach, using all kinds of statistical techniques. The rapidly growing availability of computers was an important factor in this development, as this made it possible to handle large amounts of data in a quick and rather simple manner. Statistical procedures were used to approximate an experiment in situations where variations between cases could not be controlled empirically for practical or ethical reasons (Lijphart, 1971, p. 684). This quantitative approach was also used in methodological debates as an argument to strengthen the scientific claim of the social sciences.

The search for regularities continues into our own time. Since the 1970s it appears scholars are less concerned with developing social laws or law-like generalizations, but instead are much more focused on deep understanding. A more dynamic and exploratory approach is now embraced. From various angles scholars attempt to understand administrative and political life from its underlying social and economic dynamics at the national and international level.

In this phase, there was also growing attention for the concept of “development,” especially with respect to the less developed world, as well as more attention for behavior and for informal rules. In the 1970s the early public administration was considered to be too ethnocentric. Scholars such as Riggs argued that Western models and concepts were not applicable to developing countries. Under the influence of the “Comparative Administration Group” (CAG), comparative public administration in the United States came to limit itself more and more to development administration (Van Wart and Cayer, 1990, p. 239). On the European continent comparisons remained within political science, while public administration mainly focused on national administrations. It was in that national context that institutional analysis experienced a revival in the 1980s. In the attention for development and change, for dynamics and statics in relation to the environment, scholars returned to their initial focus on political institutions and the state. This renewed interest in institutions has become known as neo-institutionalism. Neo-institutionalism continued into the 1990s.

While traditional comparative research focused on cross-national comparisons, since the 1970s other types of comparisons—such as cross-policy, cross-level, and cross-time analysis—became popular as well (see Appendix 2). Since the 1970s, and more so in the 1980s, comparative research of a quantitative-statistical bent was increasingly augmented by work of a more qualitative-interpretative nature (Collier, 1991, p. 8; Page, 1990, p. 440; Benoît & Ragin, 2009; Mahoney & Rueschemeyer, 2003), reminiscent of the dominant approach during the first two postwar decades.

1 The concept of qualitative research does not quite capture its content as well as that of quantitative research. The concept of figuration was introduced by Norbert Elias in the late 1930s and refers to the fact that we can only understand social reality in terms of the planned and unplanned forces that emanate from the “ways in which people [are] bound together and by pressures that they place [. . .] on one another . . .” (Elias, 1987, p. 166; Linklater and Mennell, 2010, p. 388).

2 The German word Wissenschaft is best translated as branch of knowledge.