4.1 INTRODUCTION

The financial crisis which started in mid-2007 took financial institutions and supervisors by surprise because it followed a long period of time characterized by ample liquidity, compressed spreads and low volatility. The wave of deregulation, coupled by increasing globalization and the development of increasingly complex derivatives products, led to risk-prone behaviours and weakened the resilience of the financial system to the shock that originated in the core business of the banking system, the asset–liability maturities' mismatch.

Since the most relevant shocks to financial markets over the previous years had been produced by excessive exposures to market factors or counterparty risk, the Basel II framework aimed at addressing mainly these issues rather than focusing on liquidity risk. As a consequence, this kind of risk was widely downplayed or ignored by academics and practitioners, while the backdrop of financial innovation quickly made both current banks' liquidity risk management practices and supervisory standards irrelevant.

The impact on global liquidity recorded during the crisis was largely affected by two main trends: increased recourse by capital markets to funding and augmented reliance on short-term maturity funding instruments. They were reinforced by the concurrent buildup of many forms of contingent liquidity claims (e.g., those linked to off-balance-sheet vehicles) and increasingly frequent margin requirements that were rating related (e.g., from derivatives transactions).

The financial crisis showed how quickly a bank could be affected by liquidity tensions if it was not well equipped with sound liquidity practices: in these cases the capital requirements defined by Basel II were little more than useless at preventing a liquidity crisis, despite the fact that well-capitalized banks should be facilitated, ceteris paribus, to raise funds on the interbank or capital markets. Indeed, capital ratios aim at warranting the solvency of banks, but they are not able to prevent their illiquidity.

In addition to the regulatory framework aimed at addressing the supervision and resolution of SIFIs, regulators have developed in recent years an international liquidity risk framework to improve banks' resilience to liquidity shocks led by market-related or idiosyncratic scenarios, and at the same time increase market confidence in banks' liquidity positions. Nevertheless, in some cases regulatory and supervisory regimes continue to be nationally based and substantially differentiated, pointing up the significant differences that do not allow a level playing field and, in some circumstances, could produce regulatory arbitrages, as well as reducing the effectiveness of supervisory actions.

4.2 SOME BASIC LIQUIDITY RISK MEASURES

Since 1992, according to the overall supervisory approach, the BCBS (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision) have made efforts to define a framework for measuring and managing liquidity, but it failed to deliver methodologies or incentives for the bank industry to develop or improve consistent and sound liquidity management practices. In its first document issued on 1992 it only suggested that supervisors differentiate their approaches to large international banks and domestic ones, while listing some methodologies based alternatively on maturity ladder or scenario analysis in order to implement effective liquidity management. Eight years later, it simply provided some definitions of liquidity risk and illustrated some developments in liquidity management and supervision, but progress on this topic was slow and inadequate to manage increasing financial innovation. In 2006 the financial industry still continued to adopt significantly differentiated risk management practices for facing liquidity risk and supervisors also persisted in adopting divergent and heterogeneous models in order to assess the liquidity profiles of financial institutions.

The financial turmoil which began in 2007 showed how the banking sector was clearly not properly equipped to manage liquidity shocks: the models adopted by banks to predict liquidity crises were demonstrated to be ineffective; contingent liquidity plans were not always successful in avoiding liquidity tensions and failed to consider extreme market events, which actually occurred; moreover, the models used by supervisors were demonstrated to be excessively optimistic. Until then, managing and measuring liquidity risk was rarely considered to be one of the top priorities by the majority of financial institutions. The financial community and the available literature did not even agree on the proper measurement of liquidity: therefore, a widely adopted integrated measurement tool capable of covering all the dimensions of liquidity risk was mere Utopia.

Among the liquidity risk metrics in use, some had adopted analytical approaches, such as VaR, which are focused on assessing potential effects on profitability, while others had developed liquidity risk models and measures aimed at accessing cash flow projections of assets and liabilities, or the inability to conduct business as a going concern as a result of a reduction of unencumbered liquid assets and of the capacity to attract additional funding. The different approaches to measuring liquidity risk were based on stock ratios, cash flow analysis, and a maturity mismatch framework.

Stock-based approaches consider liquidity as a stock and are used to compare and classify all balance-sheet items according to their “monetization”, in order to define the bank's ability to reimburse its payment obligations.

An example is represented by the long-term funding ratio, which is based on the cash flow profile arising from on and off-balance-sheet items, and indicates the share of assets that have a specific maturity or longer, funded through liabilities of the same maturity.

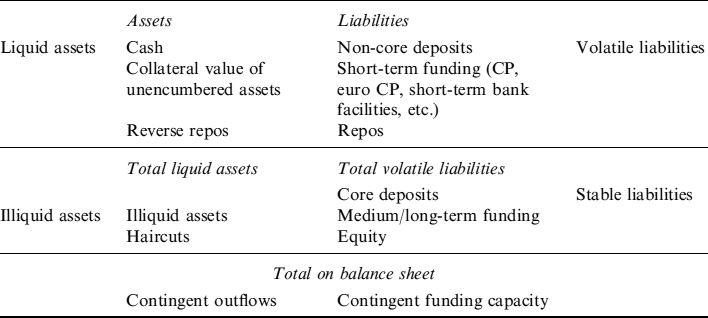

Another stock approach is provided by the cash capital position [86], which aims at keeping an asset/liability structure fairly balanced under the profile of “monetization”: illiquid assets funded by stable liabilities and marketable assets funded by volatile liabilities, as shown by the stylized reclassification of a simplified balance sheet in Table 4.1.

According to Moody's approach, which initially aimed at estimating the ability of a bank to continue its going concern activity on a fully collateralized basis, assuming that access to unsecured funding is likely to be lost after some severe short-term rating's downgrading, the cash capital position is represented by the difference between the collateral value of unencumbered assets and the sum of the volume of short-term funding and the non-core part of non-interbank deposits.

Table 4.1. Reclassified balance sheet to show the cash capital position in a stock-based approach

The above simplified reclassification of the balance sheet also shows us the reverse of this measure by focusing on the less liquid part of the balance sheet (i.e., the difference between the sum of core deposits, medium and long-term funding, capital and the sum of illiquid assets and the haircuts applied to liquid assets), where “contingent outflows” and “contingent funding capacity” represent the only flow component that can increase or reduce the measure according to its sign.

The main drawback of this measure derives from classifying balance sheet items as liquid and illiquid, without asking when exactly some positions can be liquidated or become due. This binary approach, which is a feature of all stock-based approaches, is obviously unsatisfactory as it is unable to properly qualify the variety of liquidity degree. Furthermore, stock-based approaches are not forward looking.

Cash flow–based approaches aim at keeping the bank's ability to meet its payment obligations by calculating and limiting maturity transformation risk in some way, based on the measurement of liquidity-at-risk figures. The main risk management tool is represented by the maturity ladder that is used to compare cash inflows and outflows on a daily basis as well as over a series of specified time periods (e.g., daily tenors up to 1 month and monthly buckets thereafter).

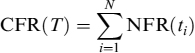

Cash flows are related to all assets, liabilities and off-balance-sheet items. In its simplest structure such analysis is not supported by any explicit assumption on the future behaviour of cash flows (new-business scenario or stressed scenario): consequently, on the basis of the grid that shows the “cash flow mismatch” or the “liquidity gap” for each time bucket, a calculation of the cumulative net excess or shortfall over the time frame (T) for liquidity assessment is easily performed:

Box 4.1. The main rules

The main liquidity adequacy rules are provided by BIPRU 12.2.1 and 12.2.3 (see [9]). According to the former: “A firm must at all times maintain liquidity resources which are adequate, both as to amount and quality to ensure that there is no significant risk that its liabilities cannot be met as they fall due.” The latter requires that “A firm must ensure that it maintains at all times liquidity resources sufficient to withstand a range of severe stress events which could impair its ability to meet its liabilities.”

where CFR(T) is the cumulative funding requirement over the chosen time horizon ending in T, and NFR(ti) is the net funding requirement at time ti, with tN = T.

The granularity of time horizons must be carefully considered. An extremely detailed breakdown provides some valuable information, but can also generate a certain amount of confusion in interpretation, especially if in a very dynamic environment where cash flows expected in 2 or 3 weeks can substantially change.

The optimal level of granularity should be chosen in accordance with the experience of the user (more granular for treasurers, less for management). Finally, the maturity ladder can assume a multiplicity of structures and cash flow composition according to the different objectives, time horizons and business units involved, with the main purpose represented by simulating the path of short-term treasury liquidity gaps, based on neutral assumptions on balance sheet items' future growth.

The maturity mismatch framework is a hybrid approach that combines elements of cash flow matching and of the liquid assets approach. As every financial institution is exposed to unexpected cash inflows and outflows, which may occur at any time in the future because of unusual deviations in the timing or magnitude, so requiring a considerably larger quantity of cash than initially forecast for business, it tries to match expected cash flows and unexpected outflows in each time bucket against a mix of contractual cash inflows, plus additional inflows that can be generated through assets sale or secured borrowing.

Therefore, unencumbered liquid assets have to be positioned in the shortest time buckets, while less liquid assets are mapped in later time buckets. In this framework, a bank is expected to hold an adequate cushion of unencumbered assets or, more generally, to develop an appropriate counterbalancing capacity in order to reduce net cumulative outflows.

The maturity ladder and, more generally, the term structure of liquidity will be analysed in detail in Chapter 6. In Chapters 7 and 8 we will study how to monitor and manage maturity mismatch by means of an adequate liquidity buffer.

4.3 THE FIRST MOVER

The UK regulator was the first to react to the 2007 financial crisis by developing a binding framework to measure and manage the liquidity risk of all financial entities active in the UK. The bank run that hit Northern Rock and the liquidity crisis experienced by the RBS stressed the urgency to develop some stricter rules in order to safeguard the stability of the UK banking system and to reassure the world's investors about the soundness of London's financial sector, which represents one of the core assets of the British economy.

Over 2009 the UK Financial Service Authority (FSA) issued some binding liquidity proposals that contemplate a major overhaul of the previous regime for all FSA-regulated firms subject to the FSA's BIPRU (Prudential Sourcebook for Banks, Building Societies and Investment Firms), UK branches of the EEA (European Economic Area) and third-country banks: liquidity regulation and supervision should have been recognized as of equal importance to capital regulation.

Each entity covered has to assess its liquidity self-sufficiency through a systems and control questionnaire that monitors the Individual Liquidity Adequacy Standard (ILAS). Basically, the bank runs a periodic assessment of its own liquidity risk measurement system by providing for figures required as a result of a stress-testing and contingency-funding plan. This assessment concerns both the risk management framework (in terms of risk appetite, systems and controls, stress analysis under multiple firm-driven scenarios and the reverse stress-testing, contingency funding plan) and liquidity adequacy (in terms of quantification of a liquid assets buffer that has to be an effective liquidity cushion under three prescribed stress tests driven by ten different risk factors), which has to be covered appropriately in all aspects.

The FSA, according to its Supervisory Liquidity Review Process (SLRP), reviews the Individual Liquidity Adequacy Assessment (ILAA) of the firm in terms of backstop purposes (the percentage of the ILAA stress scenario that the firm can currently meet and the percentage of an individualized scenario, within benchmark ranges, that the firm can currently meet) and gives individual liquidity guidance (ILG) to manage a tightening glide path, by increasing the percentage of individualized stress scenarios that need to be met over time and by recalibrating the standard stress scenario.

The ILG letter defines the prudent funding profile required of the firm, by providing short-term net type A wholesale gap limits (unsecured and secured) and the structural funding ratio. Eventually, this is followed up by checks. The figures are collected by the seven main reports described in Table 4.2.

The assessment has to be performed under some severe stress scenarios, which produce both idiosyncratic and market-wide impacts. Under idiosyncratic stress, during the first two weeks of stress, it is supposed there is

- An inability to roll over wholesale funding that is unsecured from credit-sensitive depositors or not secured on the most liquid securities (with a sustained leakage of funding lasting out to three months).

- A sizeable retail outflow (with a sustained outflow out to three months).

- A reduction in the amount of intraday credit provided to a customer by its settlement bank.

- An increase in payments withheld from a direct participant by its counterparties.

- An increase in the need for all firms (both direct and indirect participants) to make payments.

- The closure of FX markets (it is worth noting that the FSA at the moment is the only regulator that requires such an abrupt dislocation of the FX market to be assumed!).

Table 4.2. The seven reports that UK banks must produce to comply with the FSA's liquidity regulation

Report Description FSA047: daily flows Collects daily contractual cash flows out to 3 months FSA048: enhanced mismatch report Collects contractual cash flows across the full maturity spectrum FSA050: liquidity buffer qualifying securities Captures firms' largest liquid asset holdings FSA051: funding concentration Captures firms' funding from wholesale and repo counterparties FSA052: pricing data Average transaction prices and transacted volumes for wholesale liabilities FSA053: retail, SME and large enterprise funding Firms' retail, SME and corporate funding profiles FSA054: currency analysis Analysis of foreign exchange exposures - The repayment of all intragroup deposits at maturity without rolling over, and the treatment of intragroup loans as evergreen (in so doing, the mismatch to be managed by the central treasury becomes very challenging!).

- A severe downgrade of long-term rating, with a proportional impact on all other downgrade triggers.

Under the market-wide stressed scenario the firm has to face

- Rising uncertainty about the accuracy of the valuation of its assets and those of its counterparties.

- The inability to realize or only at excessive cost some particular classes of assets.

- Risk aversion among participants in the markets on which the firm relies for funding.

- Uncertainty over whether many firms will be able to meet liabilities as they fall due.

ILAA should not be considered just a list of documents required to be compliant with regulation: the ultimate goal is to show how firms can manage the liquidity risk. It is a firm-specific process with both quantitative and qualitative information continuously revised and updated. The FSA framework is a very tough regime and for that reason not easily accepted by practitioners, but so far it has been successful at addressing the liquidity problems experienced by the UK's financial sector as a result of the 2007–08 crisis.

One of the main criticisms relates to the lack of coordination with other regulators, with some requirements not fully consistent with the Basel III liquidity framework. One classic example is represented by the asset classes eligible as liquidity buffer: according to Basel III, corporate and covered bonds, with some specific limitations, are included, whereas the FSA does not admit them. In these cases regulated entities of the EEA with UK branches in whole-firm modification mode, with ILAA waived, could be compliant with their home country regulation (Basel III) but not with FSA rules, though they are required to submit periodically the above-described reports to the FSA as well in order to warrant the activity of their branches in the UK.

Box 4.2. “Dear Treasurer”

In a letter sent to all treasurers [11], the FSA highlighted the importance of consistent fund transfer pricing (FTP) practices as part of the preparation for ILAA. It required “an evidential provision for firms accurately to quantify the liquidity costs, benefits and risks in relation to all significant business activities—whether or not they are accounted for on-balance sheet—and to incorporate them in their (i) product pricing; (ii) performance measurement; and (iii) approval process for new products. The quantification of costs, benefits and risks should include consideration of how liquidity would be affected under stressed conditions … Firms should ensure that the costs, benefits and risks identified are explicitly and clearly attributed to business lines and are understood by business line management.”

FTP thus becomes a regulatory requirement and an important tool in the management of firms' balance sheet structure, and in the measurement of risk-adjusted profitability and liquidity and ALM risk. Failure to apply appropriate FTP processes can lead to misaligning the risk-taking incentives of individual business lines and misallocating finite liquidity resource and capital within the firm as a whole.

This can manifest itself in the conduct of loss-making business or in business where rewards are not commensurate with the risk taken, and thereby ultimately undermines sustainable business models. Some answers provided by firms surveyed are publicly criticized because of reference to the weighted average cost of funding either already on the balance sheet or projected in an annual budget process: according to the FSA this framework lacks sufficient flexibility to incentivize or discourage business behaviour and appropriately charge for the duration of risk.

Examples are represented by some cases in 2007 with the buildup of large inventory positions in certain asset classes, where returns were not commensurate with the risk taken, and in the onset of volatile conditions where marginal costs rose sharply and the FTP regime did not appropriately reflect the market conditions for business lines. By criticizing the use of the projected weighted average cost of funding in other cases as reference to the marginal cost of funding, the FSA ultimately seems to support the “matched funding” principle and the marginal cost of funding as the most appropriate references for an effective FTP framework.

4.4 BASEL III: THE NEW FRAMEWORK FOR LIQUIDITY RISK MEASUREMENT AND MONITORING

While the FSA was reviewing and introducing its new binding liquidity regime, Europe was some steps behind due to the heterogeneous mix of requirements and rules defined by local regulators. With regard to the level of application, some countries applied the same supervisory requirements to all entities covered independently of their size and category, whereas in other jurisdictions different rules were implemented for different types of banks (e.g., the supervisory framework admitted a more sophisticated approach for certain banks, with more flexibility to use internal modelling methods), while a more prescriptive approach was basically defined for smaller banks.

Box 4.3. The BCBS' principles

The BCBS' principles seek to promote a true culture of sound management and supervision practices for liquidity risk, based on a specific liquidity risk tolerance defined by top management according to their business strategy, and an articulate framework for risk management, product pricing and performance measurement to warrant full consistency between risk-taking incentives for business lines and related liquidity risk exposures for the bank as a whole.

They outline the role played by a “cushion” of unencumbered, high-liquidity assets to withstand a range of stress events that can affect the bank's liquidity position on the very short term and even on an intraday basis. They suggest a funding strategy that provides effective diversification in the sources and tenors of funding. Also, the funding strategy and contingency plans are to be adjusted timely and properly according to stress tests performed on a regular basis, for a variety of firm-specific and market-wide stress scenarios (both individually and in combination!) to identify sources of potential liquidity strain, and to ensure that current exposures remain in accordance with a bank's established liquidity risk tolerance.

Across jurisdictions, there were diverse approaches to liquidity supervision within some countries: the “proportional approach” was widely diffused, with an increasing intensity of supervision for larger and more systematically important firms, in proportion to the assumed increase in risk.

Following the BCBS' principles issued in September 2008 about the management and supervision of liquidity risk, in December 2010 the Basel Committee issued a document titled International Framework for Liquidity Risk Measurement, Standards and Monitoring [100] with the goal of promoting a more resilient banking sector to absorb shocks arising from liquidity stress, thus reducing the risk of spillover from the financial sector to the real economy, as has occurred since 2007. This document was later amended (January 2013) with the publication of the document Basel III: The Liquidity Coverage Ratio and Liquidity Risk Monitoring Tools (see [103]).

In order to translate these principles in some technical measures, this document proposes specific liquidity tests that, although similar in many respects to tests historically applied by banks and regulators for management and supervisory purposes, going forward will be required by regulation to improve a bank's liquidity management and to promote the short-term resilience of a bank's liquidity profile. The so-called “liquidity proposal” provided by the Basel Committee is based on three key elements:

Box 4.4. The importance of being unencumbered

Both the liquidity proposals of the Basel Committee and the Guidelines on Liquidity Buffers provided by the CEBS stress that all assets, used as a liquidity buffer to be converted into cash at any time to fill funding gaps between cash inflows and outflows during stressed periods, must be unencumbered. “Unencumbered” means not pledged (either explicitly or implicitly) to secure, collateralize or credit-enhance any transaction. However, assets received in reverse repo and securities financing transactions—which are held at the bank, have not been rehypothecated, and are legally and contractually available for the bank's use—can be considered as stock. In addition, assets which qualify as the stock of high-quality liquid assets that have been pledged to the central bank or a public sector entity (PSI), but are not used, may be included as stock.

The stock of liquid assets should not be commingled with or used as hedges on trading positions, be designated as collateral, be designated as credit enhancements in structured transactions or be designated to cover operational costs (such as rents and salaries), but should be managed with the clear and sole intent for use as a source of contingent funds.

Last but not least, this stock should be under the control of the specific function charged with managing the liquidity risk of the bank (typically the treasurer). A bank should periodically monetize a proportion of the assets in the stock through repo or outright sale to the market in order to test its access to the market, the effectiveness of its processes for monetization and the usability of the assets, as well as to minimizing the risk of negative signalling during a period of stress.

- a liquidity coverage ratio (LCR), designed to ensure that a bank maintains an adequate level of unencumbered, high-quality assets that can be converted into cash to meet its liquidity needs for a 30-day time horizon under an acute liquidity stress scenario specified by supervisors;

- a net stable funding ratio (NSFR), designed to promote more medium and long-term funding of the assets and activities of banks over a 1-year time horizon in order to tackle banks' longer term structural liquidity mismatches;

- a set of common metrics—often referred to as monitoring tools—that the Basel Committee indicates should be considered the minimum types of information that banks should report to supervisors, as applicable, and supervisors should use in monitoring the liquidity risk profiles of supervised entities.

Compliance with the two ratios and monitoring tools will be mandatory for all international active banks. Nevertheless, it is expected that they will be used for other banks and for any subset of subsidiaries of internationally active banks identified by supervisors.

4.4.1 The liquidity coverage ratio

The LCR is defined as the ratio of a bank's stock of high-quality liquid assets divided by a measure of its net cash outflows over a 30-day time period. The standard requires that the ratio be no lower than 100%. Both the numerator and denominator are defined in a way intended to ensure that sufficient liquid assets are available to meet any unexpected cash flow gaps throughout a 30-day period following an acute liquidity stress scenario that entails

- a significant downgrade (three-notch) in the bank's public rating;

- runoff of a proportion of retail deposits;

- a loss of unsecured wholesale funding capacity and reductions of potential sources of secured funding on a term basis;

- loss of secured, short-term financing transactions for all but high-quality liquid assets;

- increases in market volatilities that impact the quality of collateral or potential future exposures of derivative positions and thus require larger collateral haircuts or additional collateral;

- unscheduled draws on all the bank's committed but unused credit and liquidity facilities;

- the need for the bank to fund balance sheet growth arising from non-contractual obligations honoured in the interest of mitigating reputational risk.

High-quality liquid assets for purposes of the numerator are intended to meet four fundamental characteristics (low credit and market risk, ease and certainty of valuation, low correlation with risky assets, and listed on a developed and recognized exchange market) and four market-related characteristics (active and sizeable market, presence of committed marketmakers, low market concentration, “flight to quality” considerations).

According to the first draft of the Basel Committee's document [101] the only assets to meet these characteristics were cash; central bank reserves (to the extent that they can be drawn down in times of stress); marketable securities representing claims on or claims guaranteed by sovereigns, central banks, non-central government public sector entities, the BIS, the IMF, the EC, and certain multilateral development banks which meet specified criteria; and, last, government or central bank debt issued in domestic currencies by the country in which the liquidity risk is being taken or the bank's home country.

There are few conditions on sovereign debt that can be used as part of the pool of Level 1 assets: a bank can hold any sovereign bond issued in domestic currency in its home country, as well as any sovereign debt in foreign currency, so long as it matches the currency needs of the bank in that country.

However, it can also stock up on the debt of any other country that is assigned a 0% risk weight under the Basel II standardized approach. Under the increasing pressure ignited by the ongoing eurozone sovereign debt crisis, this requirement is now under scrutiny to be fine-tuned to include a rating component. Obviously, this plan has received a frosty reception from some market participants, already worried about the role that rating agencies should play. Moreover, introducing some kind of liquidity rating approach to the use of sovereign bonds and other assets as a liquidity buffer could be dangerously procyclical because it forces banks to replace assets that are no longer deemed eligible for this purpose. By selling them into the market, this would amplify stress effects and make it even more difficult for issuers to sell their debt at a time when they are already likely to be under pressure from the markets. Luckily, the last version of the document issued in January 2013 [103] did not introduce any significant modification about this topic, by de facto rejecting all proposals that were credit rating oriented.

After gathering data on the liquidity of corporate and covered bonds, the Basel Committee indicated that banks are allowed to consider as a liquidity buffer (so-called Level 2A) a portion of lower rated sovereign, central bank and PSE bonds, qualifying for a 20% risk weighting and high-quality covered bonds, with a minimum credit rating equal to AA−, subject however to some haircuts. An 85% factor has to be applied and multiplied against its total amount.

The reference to a minimum rating of AA− for eligibility as a liquidity buffer, instead of some link to the assets' marketability, is questionable for the same reasons mentioned above about the dependence on rating agencies and the procyclical impacts of their decisions. An alternative to the rating could be represented by some combination of the following parameters to map the assets' marketability: daily traded volumes, bid/offer spreads, outstanding amounts, sizes of deals, active public market and repo haircuts.

In any case all financial bonds are correctly excluded to avoid evident “wrong-way risk”: more questionable was the exclusion of equities quoted in most worldwide liquid indices, which have remained very liquid even in the most acute times of stress following Lehman's default. Daily traded volumes over recent years for the most liquid and less volatile stocks with low correlation to the financial sector strongly supports the call for their inclusion in Level 2 of the liquidity buffer.

Eventually, the recent draft issued by the BCBS in January 2013 has introduced some attempts aiming to prevent some potential shortage of liquidity buffers with detrimental effects on lending activity. Under mounting pressure from the financial community, who strongly suggested expanding in some ways the list of eligible asset classes for the liquidity buffer, the BCBS introduced Level 2B assets, composed of RMBS, corporate bonds and commercial paper, common equity shares, which satisfy certain specific conditions.

RMBS must: be rated AA at least; not be issued by, or the underlying assets not originated by, the bank itself; be “full recourse” in nature (i.e., in the case of foreclosure, the mortgage owner remains liable for any shortfall in sales proceeds from the property); must comply with risk retention requirements; must respect an average LTV (Loan To Value) at issuance of the underlying mortgage pool not exceeding 80%; must have recorded a maximum decline in price less than 20%, or an increase in the haircut over a 30-day period not exceeding 20 percentage points (they ultimately will be subject to a 25% haircut). Due to the sovereign caps in effect on the rating for many European jurisdictions, the minimum AA rating resulted in only UK and Dutch RMBS bonds being actually eligible.

The document seems to imply that just a single rating by an agency may be required and central bank repo eligibility may not be necessary, since there is no mention of it: if this is the case, then some Italian RMBS may be eligible as well, for example. However, we doubt that ultimately just one rating will be required for RMBS: this is because almost all of the recent regulations (including CB eligibility criteria) have moved towards requiring two ratings. Specifying LTV levels as a proxy to determine high credit quality is questionable, because LTV is only one of the many drivers behind a borrower's default. Even a well-performing sector across Europe like that of the Netherlands is not able to match the current average original LTV requirement (currently its level is equal to 95.3%). Hence, with this rule, currently only UK RMBS bonds will benefit from inclusion in the LCR.

Corporate bonds and commercial paper will be subject to a 50% haircut. They do not have to be issued by a financial institution, must have a minimum rating of BBB− and match the same rule defined for RMBS about the proven record of being a reliable source of liquidity in the markets.

Equities will be subject to a 50% haircut: they do not have to be issued by financial institutions, must be exchange-traded and centrally cleared; and must be a constituent of the major stock index in the jurisdiction where liquidity risk is being taken. They must have recorded a maximum decline in price less than 40%, or an increase in the haircut over a 30-day period not exceeding 40 percentage points, in order to represent a reliable liquidity source.

In the final analysis, equities have been accepted by the BCBS as a reliable liquidity source, but the haircut and the limit related to the liquidity risk centre are likely to reduce the potential benefits of this inclusion. First, a 50% haircut is too onerous and certainly higher than haircuts commonly found in tri-party funding programs or through stock lending activity; second, the limitation to equities only, which make up the index of the jurisdiction where the liquidity risk lies, will bring about Balkanization of this funding source, similar to the differentiation already defined for government bonds linked to the liquidity centre in order to be accepted without matching risk-weighted criteria.

Moreover, in order to mitigate the cliff effects that could arise if an eligible liquid asset became ineligible (i.e., due to a rating downgrade), a bank is permitted to keep such assets in its stock of liquid assets for an additional 30 calendar days: this would provide the bank additional time to adjust its stock as needed or replace the asset. Another mitigating rule is represented by the provision, assigned by local jurisdictions, to allow banks to apply local rating scales to Level 2 assets, meaning that bonds, which would have been affected by sovereign ceilings, may be considered eligible when there is insufficient supply of eligible assets.

High-quality liquid assets are classified in two different classes (Level 1 and Level 2, with two sublevels: 2A and 2B) on the basis of their liquidability. The proposal fixes a cap for assets included in the Level 2 class: they can only comprise 40% of the pool of high-quality liquid assets. Within Level 2 assets, so-called Level 2B assets should comprise no more than 15% of the total stock of high-quality liquid assets (HQLA). To avoid any arbitrage it is therefore necessary:

![]()

where

- LA is the amount of liquid assets;

- L1, L2A and L2B are, respectively, the amount of Level 1, Level 2A and Level 2B assets;

- AdjL1A (adjusted Level 1 assets) is the amount of Level 1 assets that would result if all short-term secured funding involving the exchange of any Level 1 assets for any non-Level 1 assets were unwound;

- AdjL2A (adjusted Level 2 assets) is the amount of Level 2 assets that would result if all short-term secured funding involving the exchange of any Level 2 assets for any non-Level 2 assets were unwound.

- adjL2B (adjusted Level 2B assets) is the amount of Level 2B assets that would result if all short-term secured funding involving the exchange of any Level 2B assets for any non Level 2 assets were unwound.

Factors of 100 and 85% are defined, respectively, for Level 1 and Level 2 assets.

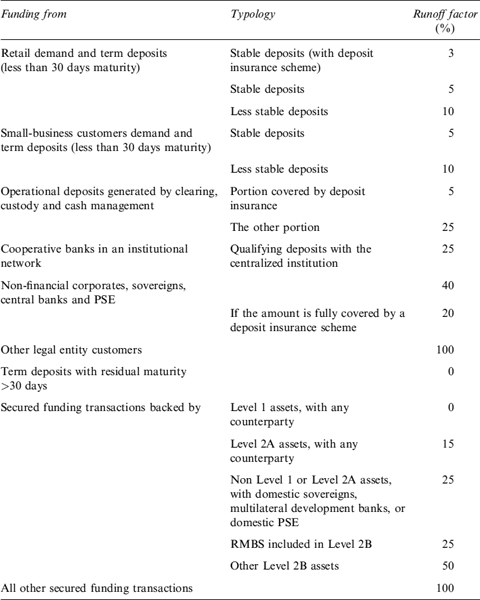

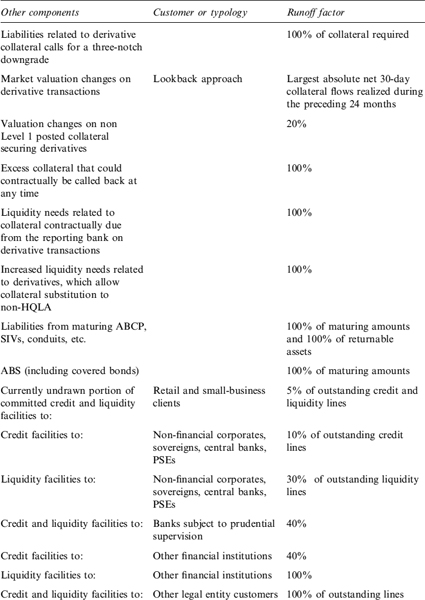

Net cash outflows are defined as “cumulative expected cash outflows minus cumulative expected inflows arising in the specified stress scenario in the time period under consideration.” The liquidity proposal includes very detailed provisions with respect to cash outflows and inflows. The approach is to identify a cash source and then apply a runoff factor to the proportion of this cash source that is expected to be paid out or received in the relevant period. Then, total expected cash outflows are calculated by multiplying the outstanding balances of various categories or types of liabilities and off-balance-sheet commitments by the rates at which they are expected to run off or be drawn down.

Runoff rates are calibrated according to expected stability factors such as government protection, public guarantee schemes, duration of client relationships with the bank, purpose of the account (e.g., transactional or savings account). Accordingly, total expected cash inflows are calculated by multiplying the outstanding balances of various categories of contractual receivables by the rates at which they are expected to flow in under the scenario, up to an aggregate cap of 75% of total expected cash outflows. This means that at least 25% of cash outflows are to be covered by holding a stock of high-quality liquid assets.

The most significant changes introduced by the January 2013 version affecting the modelled liquidity shock are:

- outflow of insured retail deposits reduced by 2% (from 5 to 3%);

- outflow of insured non-retail, non-bank deposits reduced by 20% (from 40 to 20%);

- outflow of uninsured non-retail, non-bank deposits reduced by 35% (from 75 to 40%);

- drawdown rate on unused portion of committed liquidity facilities to non-financial corporates, sovereigns, CBs and PSEs reduced by 70% (from 100 to 30%);

- outflow of interbank liquidity facilities reduced by 60% (from 100 to 40%).

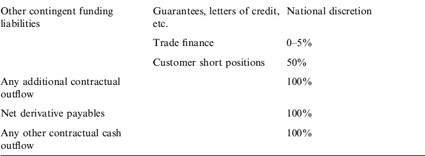

In Tables 4.3 and 4.4 we detail the runoff factors required for any kind of cash outflow.

In Table 4.5 we detail the runoff factors required for any kind of cash inflow.

It is evident that the introduction of a binding LCR has to be fine-tuned with the status of the economic cycle and the evolution of the European crisis, because banks are called to increase their liquidity buffer with uncorrelated assets (low risk and return with negative impacts on profitability figures) and lengthen the term of funding well beyond 30 days (without restoring confidence it is really challenging for European banks to attract stable funding on longer maturities), by scaling back liquidity shock–sensitive assets. The close link between sovereign debt and the banking system has to be previously broken and definitely addressed in order to avoid spillover effects on buffer composition and on market liquidity under stressed conditions.

On the basis of these considerations and on the data collected during the monitoring period already covered, the BCBS decided to delay full implementation of the LCR, previously scheduled for January 2015. The LCR will therefore be introduced as originally planned in January 2015, but the minimum requirement will be set only at 60% (!) and rise in equal annual steps to reach 100% in January 2019. This phase-in approach should ensure that introduction of the LCR will not produce any material disruption to the orderly strengthening of banking systems or the ongoing financing of economic activity.

Table 4.3. First group of runoff factors in the LCR

Table 4.4. Second group of runoff factors in the LCR

Table 4.5. Runoff factors in the LCR for cash inflows

| Cash inflows from | Runoff factors |

| Level 1 assets | 0% |

| Level 2A assets | 15% |

| Eligible RMBS | 25% |

| Other Level 2B assets | 50% |

| Margin lending backed by all other collateral | 50% |

| All other assets | 100% |

| Operational deposits held at other financial institutions | 0% |

| Deposits held at centralized institution of a network of cooperative banks | 0% of qualifying deposits |

| Amounts receivable from retail counterparties | 50% |

| Amounts receivable from non-financial wholesale counterparties, from transactions other than those listed in the inflow categories above | 50% |

| Amounts receivable from financial institutions, from transactions other than those listed in the inflow categories above | 100% |

| Net derivative receivables | 100% |

| Other contractual cash inflows | Treatment determined by supervisors in each jurisdiction |

4.5 INSIDE THE LIQUIDITY COVERAGE RATIO

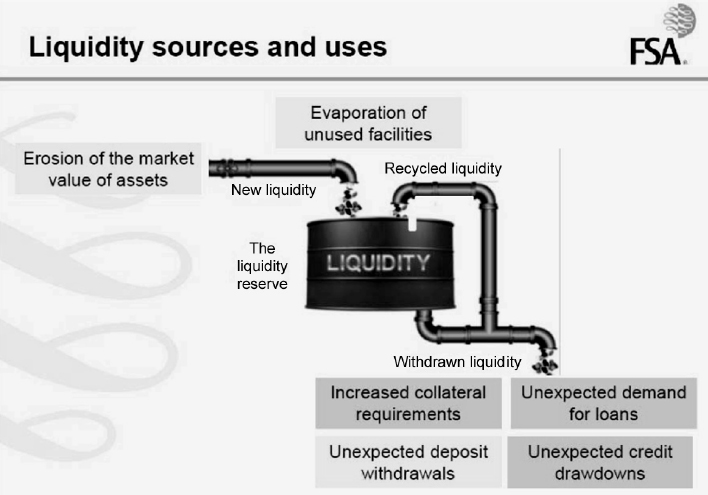

The LCR represents a hybrid combination of the stock-based approach and the maturity mismatch approach, aiming to identify a firm's counterbalancing capacity to react to a liquidity shock in the short term. It aims at building a sort of water tank to be used when liquidity needs increase unexpectedly [104], as represented in Figure 4.1, which was provided by the FSA's introductory presentation to liquidity risk (see [8]).

This technical measure is the answer to CEBS Recommendation 16 in [6], which requires that: “liquidity buffers, composed of cash and other highly liquid unencumbered assets, should be sufficient to enable an institution to weather liquidity stress during its defined ‘survival period’ without requiring adjustments to its business model.” The liquidity buffer should be composed mainly of cash and most reliable liquid uncorrelated assets which banks can monetize on markets by true sales or repos regardless of their own condition without accepting large fire sale discounts. It is recommended to avoid holding a large concentration of single securities and currencies and there be no legal, regulatory or operational impediments to use them. In order to reduce the potential stigma effect banks should be active on a regular basis in each market in which they are holding assets for liquidity purposes and on platforms used to raise funds promptly in emergency cases.

Figure 4.1. Visual representation of the aim of the LCR

Source: FSA's introductory presentation to liquidity risk [8]

The low correlation between a liquid asset and a holder is obviously of the utmost importance to assure the effectiveness of the liquidity buffer. The first version of the international framework for managing liquidity risk was issued after Lehman's collapse when government bonds had represented an actual “cushion” against the shock and recorded an impressive “flight to quality”.

Unfortunately, over the last couple of years European peripheral government bonds have become one of the key issues for the euro crisis and for the soundness of banks' balance sheets, because of the large number of these securities held for trading and liquidity purposes. On February 10, 2011, the president of Banque De France, Christian Noyer, said: “We know by experience now, after the sovereign debt crisis, that the government debt securities market is not necessarily at all moments the most liquid and the safest, so that this concentration may be very risky.”

Up to the present, Spanish and Italian bonds have been traded and funded by repos with good liquidity even in the most acute phases of the stress: therefore, the requirement for their marketability has always been respected. It was different for Portuguese and Greek bonds, which lacked liquidity after the two governments applied for IMF and EC funds. The monetization of these securities, for certain periods of time, has only been assured by ECB refinancing.

This example highlights the importance of properly analysing the link between an asset's monetization and its eligibility for central bank refinancing. For instance, the position of the FSA, strongly endorsed by the Bank of England, is that the buffer should focus on high-quality government bonds. According to the Bank of England it is particularly important that no automatic link be drawn between eligibility in central bank operations and the definition of the regulatory liquid asset buffer. It believes that a regulatory regime that defined liquid assets as those which were central bank eligible, but were not reliably liquid in private markets, would imply a reliance on central banks as liquidity providers or first resort, which is not recommendable to assure financial stability.

According to the CEBS [6], “central bank eligibility plays a role in identifying the liquid assets composing the liquidity buffer, since central bank collateral lists are defined in normal times predominantly around marketability criteria. Furthermore, the reference to central bank eligibility in this paper excludes emergency facilities that may be offered by central banks in stressed times.”

Nevertheless, banks have to clearly understand the terms and conditions under which central banks may provide funding against eligible assets under stressed conditions. They should periodically test whether central banks will effectively provide funding against such assets and should apply appropriate haircuts to reflect the amount of funding that central banks might actually provide under stressed conditions.

From a theoretical point of view, the difference between marketability and central bank (CB) eligibility is clear: for instance, at the moment some equities are clearly marketable but not CB eligible, whereas some ABSs are eligible but they cannot be sold easily on the market under stressed conditions. In practice, the difference becomes narrower. Many securities may be funded through repos because they are included in the so-called “ECB eligible basket”: this means that the market funds some asset classes not by analysing single securities, but simply by checking the possibility of refunding them by means of the CB if needed. In this case, ECB eligibility is a quality check stamp that helps to increase market demand for an asset (if banks believe that they will be able to generate liquidity from the CB and as the CB acts in some ways like a significant additional market participant) and allows refinancing of the security through the repo market; but this market behaviour is based on the mistaken belief that ECB eligibility means automatic marketability (because some CBs use marketability as the key criterion for determining their own eligibility list), with some dangerous procyclical impacts in case the ECB decides to no longer accept some securities as eligible collateral.

It is important for banks to demonstrate adequate diversification in the total composition of the buffer so as to guarantee to supervisors that they are not relying too heavily on access to central bank facilities as their main source of liquidity. On the other hand, regular participation in open market operations should not, per se, be interpreted as close dependence on central banks: as shown in Chapter 2, without CB liquidity banks would not be able to make their payment obligations at all.

The liquidity buffer represents the excess liquidity available outright to be used in liquidity stress situations within a given short-term period. Its size should be determined according to the funding gap under stressed conditions over some defined time horizon (the “survival period”), which represents just the time period during which any institution can continue operating without needing to generate additional funds and still meet all its payments due under the stress scenarios assumed: this topic, as well as the relation between the liquidity buffer and counterbalancing capacity, will be analysed in detail in the second part of the book. Both the liquidity buffer and survival periods should not represent exhaustive tools to manage liquidity risk: they should not supersede or replace other measures taken to manage the net funding gap and funding sources, as the institution's focus should be on surviving well beyond the stress period.

In order to define the severity of stress and the time horizon, the Basel Committee has defined another two dimensions of the analysis: a period of one month as the time horizon, by accepting the suggestion of the CEBS (“A survival period of at least one month should be applied to determine the overall size of the liquidity buffer under the chosen stress scenarios. Within this period, a shorter time horizon of at least one week should be also considered to reflect the need for a higher degree of confidence over the very short term,” according to Guideline 3 on liquidity buffers [6]) and the characteristics of the assets to be eligible as a liquidity buffer.

Runoff factors are the drivers defined to implement the stress scenario for balance sheet items. In a very simplified approach they allow a static simulation to be run over assets and liabilities items in order to provide, as output, a synthetic ratio that combines features of both the stock-based and cash flow–based approaches. Fortunately, some questionable provisions of the previous version of the document have been properly amended in the recent draft [86]: for instance, the assumptions about the drawdown of credit and liquidity lines have been modulated according to the different types of borrowers and some severe percentages have been scaled back.

However, uncommitted lines should not be assumed to be drawn down as a matter of fact, but subject to an evaluation of the related reputational risk. As for secured lending (e.g., reverse repos), the approach still appears too binary: for high-quality liquid assets the haircuts are small, for other assets it is supposed there is no rollover at all. They are either fully liquid and part of the liquidity buffer or completely illiquid (in which case there are no cash inflows). This is at odds with actual experience, where things are not black and white, but often grey. In some cases the asymmetrical treatment of items is questionable: an owned liquidity line should not be denied and given the same drawdown assumption as a sold liquidity line.

Last but not least, inflows accepted for the LCR calculation have to be “contractual” for Italian banks (i.e., with a specific maturity agreed in the contract): therefore, so-called “sight assets”, or assets on demand, are excluded from the calculation of inflows in the LCR as they do not have a defined contractual maturity. This obviously penalizes some jurisdictions, like the Italian one, where sight assets are the traditional instrument used by banks to finance their corporate customers. Actually, sight assets are not different from loans with a contractual maturity of less than 30 days and the probability that both are actually repaid is virtually the same, since the right to request payment with such terms contractually defined applies to the first ones as well.

4.6 THE OTHER METRICS

The net stable funding ratio is defined as the ratio of the bank's “available amount of stable funding” divided by its “required amount of stable funding”. The standard requires that the ratio be no lower than 100%. It is designed to ensure that investment banking inventories, off-balance-sheet exposures, securitization pipelines and other assets and activities are funded with at least a minimum amount of stable liabilities in relation to their liquidity risk profiles, in order to limit overreliance on short-term wholesale funding during times of buoyant market liquidity.

The ultimate goal is to reduce the aggressive maturity transformation of the banking sector by creating an incentive to have a matched funding of assets at a higher level than in the past: this longer term structural liquidity ratio is therefore intended to deal with longer term structural liquidity mismatches by establishing a minimum acceptable amount of stable funding based on the liquidity characteristics of a firm's assets and activities over a one-year horizon. Ultimately, it represents a cap on liabilities/assets turnover.

Generally, the numerator in the ratio is calculated by applying to designated items on the right-hand side of the balance sheet (the liabilities side) an ASF (available stable funding) factor, ranging from 100% to 0% depending on the particular equity or liability component, with the factor reflecting the stability of funding. Similarly, the denominator in the ratio is calculated by applying to each asset on the left-hand side of the balance sheet (the assets side) and certain off-balance-sheet commitments a specified required stable funding (RSF) factor, reflecting the amount of the particular item that supervisors believe should be supported with stable funding. More specifically, with respect to the numerator in the ratio:

- available stable funding is defined as the total amount of a bank's capital (Tier 1 and 2 capital after deductions), plus preferred stock with a maturity of one year or more, plus liabilities with effective maturities of one year or more, plus that portion of stable non-maturity deposits and/or term deposits with maturities of less than one year which would be expected to stay with the bank for an extended period in an idiosyncratic stress event;

- ASF factors range from 100% to 0%, with more stable funding sources having higher ASF factors and, accordingly, contributing more to meeting the minimum 100% requirement. For example, Tier 1 and 2 capital are assigned 100% factors, stable retail deposits 85%, less stable retail deposits 70%, certain wholesale funding and deposits from non-financial corporate customers 50%, and other liabilities and equity categories 0%.

With respect to the denominator in the ratio:

- the required amount of stable funding is calculated as the sum of the value of assets held, after converting certain off-balance-sheet exposures to asset equivalents, multiplied by a specified RSF factor;

- RSF factors range from 0% to 100%, with less stable funding sources having lower RSF factors and, accordingly, contributing more to meeting the minimum 100% requirement. For example, cash and money market instruments are assigned a 0% factor, unencumbered marketable securities with maturities of one year or more and representing claims on sovereigns a 5% factor, unencumbered AA corporate bonds with maturity of one year or more 20%, gold 50%, loans to retail clients having a maturity of less than one year 85%, and all other assets 100%.

The introduction of a binding NSFR is likely to produce significant impacts on the real economy, because the ratio represents an actual limit to the maturity transformation performed by banks. They are requested to work according to the “matched funding” criterion, which is likely to lead to a general review of current liquidity pricing policies, with loans more expensive for corporate and private customers. Moreover, it tends to discourage securitization activities, through which banks transform their illiquid assets into more liquid instruments.

As the ABSs resulting from the securitization process are likely to be non-marketable instruments, all holdings of these ABSs with a weighted average life exceeding one year are 100% accounted for in the determination of required stable funding and must be watched with medium/long-term funding. From the perspective of a bank willing to grant medium/long-term credit to its customers in the form of mortgages, credit card loans, personal loans, etc. the NSFR states that loans with maturities exceeding one year must be funded with medium/long-term funding up to percentages that depend on loan credit quality and are completely independent of the possibility of being securitized. As a result, lending banks cannot draw any benefits in terms of treasury from securitizations.

The BCBS agreed that the NSFR will move to a minimum standard by January 1, 2018, in order to avoid any unintended consequences on the functioning of the funding market. Similarly, as pointed out earlier about the LCR, it will be very challenging for the financial sector to support the real economy without the normal functioning of capital markets, whereas banks are focused on lengthening the longer term of funding and reducing maturity mismatch by scaling back activities vulnerable to stress tests. The EBA, based on reporting required by regulation, will evaluate how a stable funding requirement should be designed. On the basis on this evaluation, the Commission should report to the Council and the European Parliament together with any appropriate proposals in order to introduce such a requirement by 2018. Although the last version of the BCBS document about liquidity ratios confirmed January 1, 2018 as the start date for the NSFR, the phase-in period defined for the LCR obviously suggests that a similar approach could be introduced in the near future for the NSFR as well.

Last but not least, the liquidity proposal outlines four monitoring tools, or metrics, to accompany the two ratios with the intention of providing “the cornerstone of information which aids supervisors in assessing the liquidity risk of a bank.”. The metrics aim to address contractual maturity mismatch, concentration of funding, available unencumbered assets and market-related monitoring tools.

Contractual maturity mismatch collects all contractual cash and security inflows and outflows, from all on and off-balance-sheet items, which have been mapped to define time bands based on their respective maturities. The precise time buckets are to be defined by national supervisors.

Concentration of funding is measured by the following data: the ratio of funding liabilities sourced from each significant counterparty to the “balance sheet total” (total liabilities plus shareholders' equity), the ratio of funding liabilities sourced from each significant product/instrument to the bank's balance sheet total, as well as a list of asset and liability amounts by each significant currency. Each metric should be reported separately for time horizons.

Box 4.5. What does “significant” stand for in the preceding paragraph?

A “significant counterparty is defined as a single counterparty or group of affected or affiliated counterparties accounting in aggregate for more than 1% of a bank's total liabilities. Similarly, a “significant instrument/product” is defined as a single instrument/product or group of similar instruments/products which in aggregate amount to more than 1% of the bank's total liabilities, and a “significant currency” is defined as liabilities denominated in a single currency, which in aggregate amount to more than 1% of the bank's total liabilities.

Diversifying the number of counterparty names is a very common strategy, but it is not always effective, because wholesale fund providers are often cynical arbiters of credit quality. They may take some days longer than others before refusing to extend credit, but the end result is the same: during a liquidity crisis it hardly represents a stable funding source.

A far cleverer approach is to diversify the type of counterparty, instead of the name. Actually, all institutional fund givers set their own counterparty limits restricting the amount they can provide to any single borrower, no matter the form of the borrowing.

Some concentration in counterparty type does not always represent a negative factor: let us think about retail deposits, which are actually stickier than other types. This is a case of concentration that almost certainly reduces risk. Diversification by counterparty type should focus on assuring that, among the most volatile funding sources, there is no significant concentration for a single counterparty, for a group of similar counterparties or for single markets.

As already noted, since retail deposits tend to be more stable even during crises while wholesale funding tends to be more volatile and to dry up more quickly, it is crucial to analyse the degree of diversification of the funding. Oddly, although the connection between diversification and liquidity risk is well known, in the past many firms have failed to grasp how the relationship can contribute to liquidity shortage.

Northern Rock is a good example: it maintained a low level of diversification from the perspective of both assets (business segment specialization) and liabilities (retail deposit base) and, on the verge of collapse, was saved by the Bank of England in August 2007. Ironically, only two months before, it had stated that calculations of capital requirements showed an excess of capital, allowing the bank to initiate a capital repatriation program: when performing these calculations, the bank obviously failed to take into account all factors that could affect its liquidity position even in the very short term, like the dangerous concentration of its balance sheet.

The aim of the two other tools is only informational. Available unencumbered assets are defined as “unencumbered assets that are marketable as collateral in secondary markets and/or eligible for central banks' standing facilities.” For an asset to be counted in this metric, the bank must have already put in place operational procedures needed to monetize it. Market-related monitoring tools are early-warning indicators of potential liquidity difficulties at banks. They include market-wide information, financial sector–related and bank-specific data.

Although monitoring tools used to be downplayed by academics and practitioners who prefer to focus on ratios, stress scenarios and contingency funding plans, they are of the utmost importance in filling the gap of information asymmetries between financial actors and regulators. By gathering exhaustive and granular data from covered entities, regulators can remove one structural issue that represents one of the root causes of liquidity risk—asymmetric information—which does prevent distinguishing between illiquid and insolvent banks and blurs interbank peer-monitoring among financial players.

4.7 INTRADAY LIQUIDITY RISK

For the largest banks, deeply involved in settlement and payment systems, another crucial risk to monitor is represented by intraday liquidity risk. It is related to intraday liquidity, which can be defined as [101] “funds which can be accessed during the business day, usually to enable financial institutions to make payments in real-time.”

This topic has received little attention by regulators until recently. It was only in July 2012 that it gained momentum with the consultative document Monitoring Indicators for Intraday Liquidity Management issued by the BCBS.

Surprisingly, this document lacks a clear definition of intraday liquidity risk and focuses only on intraday liquidity management (i.e., the measurement and mitigation of this risk in order to ensure the reasonable continuation of payment flows and the smooth functioning of payment and settlement systems).

Intraday liquidity risk is related to cases in which banks are not able to actively manage their intraday liquidity positions to meet payment and settlement obligations on a timely basis under both normal and stressed conditions: for direct participants to payment systems, because outgoing payment flows can precede compensating incoming payment flows and sources, including collateral transformation, overdrafts and extraordinary sources; for indirect participants, because the correspondent bank can be under liquidity or operational stress. Such relevant elements as intraday liquidity profiles can therefore differ between banks depending on whether they access payment and settlement systems directly or indirectly, or whether or not they provide correspondent banking services and intraday credit facilities to other banks.

Box 4.6. BCBS Principle 8

The BCBS refers to intraday liquidity risk in [99], Principle 8, which suggests, interalia, that a bank

- should have the capacity to measure expected daily gross liquidity inflows and outflows, anticipate the intraday timing of these flows where possible and forecast the range of potential net funding shortfalls that might arise at different points during the day;

- have the capacity to monitor intraday liquidity positions against expected activities and available resources (balances, remaining intraday credit facility and available collateral);

- arrange to acquire sufficient intraday funding to meet its intraday objectives;

- have the ability to manage and mobilize collateral as necessary to obtain intraday funds;

- have a robust capability to manage the timing of its liquidity outflows in line with its intraday objectives.

In its consultative document [101], the BCBS seeks feedback from the financial industry about some indicators designed to enable banking supervisors to monitor a bank's intraday liquidity risk management and to gain (i) a better understanding of payment and settlement behaviour and (ii) the management of intraday liquidity risk by banks.

It has been stressed [102] that the proposed indicators are for monitoring purposes only and do not represent the introduction of new standards around intraday liquidity management. Nevertheless, there is a concern that these requirements could represent the first step toward defining new binding indicators, with potential overlapping with the LCR. Bank data demonstrating insufficient liquidity over specific time intervals, or operation very close to the bone with its daily liquidity flows, will be scrutinized by supervisors: this could drive banks to slow the pace of scheduled payments so that their results appear stronger on both absolute and relative bases, with an increase in systemic risk. Moreover, if banks decide to withhold scheduled payments, gridlock across and between multiple payments systems may ensue. This scenario could become procyclical during periods of systemic stress, when many correspondent banks increase prefunding requirements. It is crucial that the final release gives greater prominence and clarifies beyond any doubt that these indicators are simple monitoring tools.

Some concern is related to the monitoring and reporting requirements for indirect payment system participants. First, many banks are direct participants in some systems and indirect participants in others, with needs to aggregate data for different purposes. Second, indirect participants lose control of their payments once they submit instructions to the correspondent bank, because payments are made at the correspondent bank's discretion: this inability to control when payments are actually made or to receive in many cases intraday liquidity data could obviously affect the reporting of indirect participants. Finally, for all banks collecting intraday liquidity data will represent a very challenging task, with significant issues of capacity in gathering and storing thousands upon thousands of data points every month for all used payment systems across all legal entities, all significant overseas branches and all currencies [103].

Box 4.7. The proposed set of indicators for intraday liquidity risk

The list of indicators proposed by the BCBS [101] is:

- Daily maximum liquidity requirement: this is the bank's largest negative net cumulative position (difference between the value of payments received and the value of payments made at any point in the day) calculated on actual settlement times during the day. The actual use of liquidity instead of what is required to fulfil payment obligations in a timely manner is counterintuitive, because in several systems payments are released earlier than required to ensure smooth flows: measuring actual use could discourage such beneficial timing decisions and increase payments hoarding. Moreover, because payments are a zero-sum game, at the same time there will be at least one bank in a positive position and one in a negative situation. This requires good management and continuous judgement to properly address not only the activity of a single bank but also to avoid gridlock in the system and operational risk for the banking system.

- Available intraday liquidity: this is the amount of intraday liquidity available at the start of each business day and the lowest amount of available intraday liquidity by value on a daily basis throughout the reporting period. All forms of liquidity buffers and reserves potentially represent intraday liquidity and should be considered, because the stress scenarios analysed by this consultative document are exactly those for which the LCR buffer is held.

- Total payments: these are the total value of the gross daily payments made and received in payment and settlement systems.

- Time-specific and other critical obligations: these are obligations which must be settled at a specific time within the day or have an expected intraday settlement deadline. Unfortunately, for a large bank cutoff times are actually scheduled at least at every hour during the day. Banks should report the volume and value of obligations and the same figures for obligations missed during the report period.

- Value of customer payments made on behalf of financial institution customers: this is the gross value of daily payments made on behalf of all financial institution customers, with the value for the largest five financial institution customers given in greater detail.

- Intraday credit lines extended to financial institution customers: this is the total sum of intraday credit lines extended to all financial institution customers, with the value of secured and unsecured credit as well as of committed and uncommitted lines for the largest five financial institution customers given in greater detail.

- Timing of intraday payments: this is the average time of a bank's daily payment settlements over a reporting period.

- Intraday throughput: this is the proportion, by value, of a bank's outgoing payments that settle by specific times during the day (i.e., 9.00 AM, 10.00 AM, etc.)

Banks would be obliged to report these indicators once a month, along with the average level, the highest and lowest value for each indicator, under normal times and four stress scenarios (own financial stress, counterparty stress, customer stress, market-wide credit or liquidity stress). In addition, they have to report the 5th percentile value for available intraday liquidity, and the 95th percentile value for the other six quantitative indicators.

4.8 BEYOND THE RATIOS

The aim of the regulator was clearly to define some effective measures to be implemented by all covered entities, from the more complex financial group to the smallest bank. This represents a kind of simplified standard approach that gives the international financial industry a common “level playing field” on liquidity risk.

One of the most obvious criticisms of these measures is related to this one-size-fits-all approach. These ratios are calculated with predefined standard aggregations and stress assumptions, but these assumptions should differ across banks according to their different sizes and business models, such that the operating processes prevailing in different countries are also considered.

The “one-size-fits-all” assumption sets for both ratios cannot properly fit the differences in the funding processes of different economies: for instance, within the eurozone, households' savings are different in amounts and structures, notably due to tax incentives (e.g., the Netherlands, France); corporate behaviour regarding deposits is not standardized and strongly depends on all outstanding relations with the bank (e.g., Italy).

To the extent that funding requirements would not be consistent with what funding providers (i.e., households at the end of the day) can deliver in balance or terms, or with the required rates to attract those funds compared with the acceptable rates for funding needs (i.e., households, corporates and governments), the impacts would be detrimental to the economy as a whole. These effects would be more significant on the European economy, as it is bank-intermediated much more than the US economy in the funding process.

Both ratios treat assets and liabilities in many cases in an asymmetric way: inflows and liabilities are always subject to time decay, whereas in some cases outflows and assets are required to be mapped as constant maturity products. This leads banks to overfund the actual need of the investment and to reinvest liquidity excess in shorter term or in highly liquid assets.

Focussing on the LCR, one of the most widespread criticisms across the financial community relates to the use of liquidity buffers during phases of stress. Since the prudential stressed scenario defined by runoff factors, as above explained, represents de facto a situation with already severe liquidity strains, common sense would suggest that buffers, or at least some of them, should be used in cases of crisis, acting as anticyclical factors that can be replenished as soon as market conditions allow. Disallowing this would mean no longer discussing liquidity buffers, but some form of unavailable collateral instead, pledged to cover unspecified risks that could occur after the likely liquidity crisis of the bank.

Obviously, regulators have to face a challenging tradeoff between easing the tough requirement of LCR above 100% in any state of the world and risking allowing banks to use and evaporate the main line of defence against liquidity shocks before the crisis moves toward the most acute phase of stress. The January 2013 draft addresses this issue in a general way, by stating that “during a period of financial stress, however, banks may use their stock of HQLA, thereby falling below 100%, as maintaining the LCR at 100% under such circumstances could produce undue negative effects on the bank and other market participants. Supervisors will subsequently assess this situation and will adjust their response flexibly according to the circumstances”. While stressing the opportunity of accounting not only for the prevailing macrofinancial conditions, but also the forward-looking assessments of macroeconomic and financial conditions, the BCBS provides a list of potential factors that supervisors should consider in their assessment in order to avoid some procyclical effects:

- the reason the LCR fell below 100% (i.e., using the stock of HQLA, an inability to roll over secured funding or large unexpected draws on contingent obligations, general conditions of credit and funding markets);

- the extent to which the reported decline in the LCR is due to firm-specific or market-related shock;

- a bank's overall health and risk profile;

- the magnitude, duration and frequency of the reported decline in HQLA;

- the potential for contagion of the financial system and additional restricted flow of credit or reduced market liquidity due to actions to maintain an LCR at 100%;

- the availability of other sources of contingent funding such as CB funding.

The observation period of the LCR is clearly standardized, but for a bank involved in correspondent banking, clearing and settlement activities, even a 30-day timeline could be too long. As for the application, ongoing monitoring is required and reported at least monthly, with any delay less than 2 weeks. Even if a higher reporting frequency is required during stressful times, non-continuous monitoring could turn out to be suboptimal because it could easily be behind the curve. Both ratios look at the liquidity gap over some predefined time horizons: no information is provided about liquidity exposures over other periods of time.

Let us turn to the role played by capital in both ratios: it is eligible for the NSFR as a stable funding source, whereas it is taken into account for the LCR only to the extent it is invested in eligible liquid assets. The basic idea put forward by the Basel Committee is that banks should first raise some amount of new capital, and then invest it to build a liquid asset buffer that is compliant with liquidity requirements.

On the question of derivatives, the BCBS requires consideration be given to the largest absolute net (based on both realized outflows and inflows) 30-day collateral flow realized during the preceding 24 months as an outflow for the LCR. This requirement should aim to capture banks' potential and substantial liquidity risk exposure to changes in mark-to-market evaluation of derivatives transactions, under collateral agreements, that can lead to additional collateral posting in case of adverse market movements. Unfortunately, it would have been better to adopt an approach based on the actual exposure of the derivative portfolio to market parameters, instead of measuring this potential outflow on the basis of a lookback approach. Indeed, the current requirement, although very easily implemented by all covered entities, could fail to capture the actual liquidity risk in case of increased market risk exposures compared with those of the past.

The need to increase the size of the liquid asset buffer (for the LCR) and to raise medium/long-term liquidity (for the NSFR) is likely to impact financial markets. So, the decision to fix different timelines for the ratios is welcome: an observation period until 2015 for the LCR and 2018 for the NSFR. Nevertheless, the ratios' requirements are likely to generate some distorting effects on bond markets, as already seen in recent years with the increasing demand for government bonds. In fact, additional shifts in demand towards assets eligible for inclusion in the liquidity buffer are to be expected.