CHAPTER SEVEN

Learning from the India Way

Redefining Business Leadership

THE IDEAS BEHIND the India Way are compelling. Finding novel solutions to the hard problems of long-term customers and relying on improvisation and adaptability to do so are sensible and powerful techniques for competing. The most powerful ideas in the India Way, especially for those in the broader society, come from the fact that Indian corporations have been able to succeed in the marketplace while pursuing a social mission and taking care of their employees. Social responsibility, our fifth and final area of company focus—along with people management, executive leadership, competitive strategy, and company governance, which have been the focus of our prior chapters—is an integral feature of the India Way, a direct product of its axial emphasis on broad mission and purpose.

The India Way’s focus on mission and purpose with its stress on personal values, expansive thinking, and public purpose, we have found, is one element of a four-part formulation. Indian executives also place a high value on holistic engagement with their employees, seeing them as assets to be developed and celebrated. Business leaders stress improvisation and adaptability, creativity and resilience, jugaad and adjust. And they search for creative value propositions that speak to the needs of millions of customers with modest means. These ideas are especially timely as they represent an important alternative, indeed a challenge, to accepted ways of operating businesses.

Contrast with the U.S. Model for Leadership

The success of the India Way is important in its own right, of course, as it is crucial to the economic and social health of what will soon be the world’s most populous country. It may turn out to be just as important as a model for countries elsewhere, not just those struggling to modernize but also those that are already economically developed. Can India provide an example for these countries? More pointedly, will it challenge what has been the dominant model for business in many parts of the world, that of the United States? Answering that question requires some background on the evolving practices of the U.S. model.

After World War II, when the rest of the industrial world was in tatters, American ideas about how to organize business and the economy were transferred abroad in part by the U.S. government, in part by U.S. multinationals, but also through the power of example. 1 Important lessons included the corporate model of ownership and organization, in contrast to family-owned and smaller-scale operations that were more typical especially in Europe; mass-production principles; open markets and informal oligopolies, in contrast to more formal cartels; organizational structures relying on hierarchies and complex, M-form or multidivisional models, in contrast to informal organizational forms associated with smaller, familybased businesses; and workplace organization based on collective bargaining with trade unions whose goals were explicitly practical rather than political.2 Many, if not most, of these practices were adopted by the world’s industrialized countries.

After the OPEC oil price shocks of the 1970s, the success of Japanese business coincided with the poor performance of the U.S. economy in the early 1980s to make Japan arguably the most important source of management ideas. But the U.S. model was soon to reinvent itself around a more open-market framework and stage a substantial comeback in the 1990s.

The resurgent U.S. model drew heavily on old values. Alexis de Tocqueville, the nineteenth-century French chronicler of U.S. ways, observed in Democracy in America that Americans “are fond of explaining almost all the actions of their lives by the principle of self-interest rightly understood,” and America’s culture of individual achievement has long placed a premium on being clear minded about the pursuit of one’s private purpose.3 Unbridled capitalism, American-style, held “that the common good is best served by the uninhibited pursuit of self-interest,” in the words of hedge-fund manager and social critic George Soros.4 The 1980s and ’90s applications of these ideas asserted that the best way for economies to develop was to reduce the role of government—lower taxes, fewer subsidies, less regulation—and encourage private ownership and self-interest. These views were crystallized into a model for economic development and became known as the “Washington Consensus,” reflecting the fact that these principles for stimulating economic growth were shared by the U.S. government and the international institutions over which it had great influence, especially the International Monetary Fund.5

Alan Greenspan, then chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, articulated the idea that the rest of the world was moving toward this U.S. model in his statement to Congress during the 1998 Asian financial crisis: “My sense is that one consequence of this Asian crisis is an increasing awareness in the region that market capitalism, as practiced in the West, especially in the United States, is the superior model.” He went on to emphasize the importance of “greater reliance on market forces, reduced government controls, scaling back of government-directed investment, and embracing greater transparency” as being central to the U.S. approach .6

The U.S. business community also argued vociferously that the key to its competitiveness was the ability to restructure quickly when operations proved uncompetitive and, in turn, to be able to start up quickly in a different direction. As a practical matter, that meant having greater ability to lay off workers, close facilities, and move on. Long-term obligations to employees and efforts to protect their interests were seen as obstacles to competitiveness.7 The apparent success of Silicon Valley and its model based on constant restructuring with job cuts and outside hiring seemed especially compelling.8

The central aspect of the Washington Consensus was arguably the focus on shareholders and their interest in profit maximization as the primary goal for business. An earlier generation of U.S. executives would have been perfectly comfortable with the India Way’s need for executives to balance the often competing interests of “stakeholders” in the business, especially employees, the community, and shareholders. The assertion that shareholders’ interests were absolutely primary was something new and became known as financialization because of the emphasis on financial goals and shareholder value.9 Sociologist Ronald Dore credited this development in large part to the growing influence of an intermediating financial industry that essentially governed business by relying on free-market pricing of equity assets to reward or punish companies based on their profit performance.10 This financial industry includes private-sector agencies that rate and evaluate companies based on the assumption of transparent financial information, as well as traders who themselves profit from the buying and selling of equities and speculation in them.

The most obvious influence of financialization was arguably the rise of financial incentives to encourage executives to operate their businesses to maximize shareholder interests in profit. In the early 1990s, less than 10 percent of total executive compensation at publicly held U.S. firms was accounted for by pay that was contingent on stock prices, but by 2003, that figure was almost 70 percent.11 Evidence suggested that aligning the interests of executives to those of shareholders across countries led to better corporate performance, although that was perhaps not surprising given the lack of any prior systems for managing executives in many countries. 12

Dissenting voices in the United States had long questioned the notion that profit maximization was the only goal for business, holding that the role of the executives should be more about balancing the claims of competing stakeholders and less about optimizing private wealth. But such concerns had remained those of a dissident minority and in recent years more or less disappeared. De Tocqueville’s reference to America’s penchant for self-interest “rightly understood”—what we often reference today as “enlightened” self-interest that includes the concerns of the broader community—had become a quaint relic of the past.

Can the India Way compete with financialization as a model for operating businesses? If not compelling enough on its own merits, the India Way benefits from the fact that the U.S. model has suffered a series of self-inflicted injuries, the most important of which is the unending (as of the time of writing) stream of corporate financial scandals that began in the mid-1990s. The common theme across all these scandals has been financial fraud in various forms driven by executives who attempted to manipulate financial results in order to improve share prices and enrich themselves. The most prominent examples were based on malfeasance on such a monumental scale that it literally brought the company down, as at Enron, WorldCom, Adelphia, and Global Crossing. But the list of companies where financial malfeasance was not quite bad enough to force the failure of the company is much longer, including Sunbeam, Waste Management, Tyco, and HealthSouth. A marker for financial irregularities is earnings restatements, in which companies revise earnings that had previously been presented as accurate, representing serious accounting errors. The General Accounting Office calculated that these restatements, once quite rare, grew by 145 percent from 1997 to 2001, with some 10 percent of all publicly traded companies restating earnings during that period.13 Further, all the major accounting firms were involved in cases of audit failure, in which the firms were found not to have followed standard audit procedures. The fact that these scandals were so common in the United States and so much less so in other countries suggested that something about the financialization practices in the U.S. might be to blame, and the compensation systems that reward U.S. executives for improving share prices were a leading candidate.14

The festering financial scandals had less influence on world attitudes than the 2008–2009 financial crisis, triggered by American investment banks that had heavily incentivized their executives with stock options to optimize shareholder value but not to adequately manage enterprise risk or foresee societal damage. Poor decision making at Wall Street investment banks (Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers, and Merrill Lynch) quickly spread to the banking sector and from there to financial institutions around the world, and led to a global recession, the worst in the United States since 1982–1983.15 By early 2009, the extent to which much of the rest of the world blamed U.S. business practices and government policies for the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent world recession was palpable at international gatherings. 16 The crisis rekindled a simmering debate about the proper role of personal gain and shareholder value in business affairs. 17

As a result, much of the world is ready to look past the U.S. for business models. The National Intelligence Council of the U.S. government develops probable scenarios for world events. It argues that the fastest-growing economies in the near future will likely rebuff the U.S. model. 18 Where will they turn? “State capitalism” as expressed in the Chinese model is thought to be the leading contender, where government intervenes directly and frequently in business affairs. Yet systems where government has the ability to intervene in this manner have generally not had a good track record elsewhere either in terms of economic success (exceptions include Singapore and the United Arab Emirates) or especially in terms of liberty—a deep concern for countries with “liberal” democratic orientations.

In this context, the India Way represents an especially compelling alternative. It preserves the logic of free markets and real entrepreneurship within the context of democratic institutions. In essence, it preserves the heart of the capitalist model. As the same time, it appears to avoid some of the apparent rapaciousness and excesses of the American model that are redressed at best imperfectly via government regulation. Companies following the India Way go well beyond not doing harm to the social fabric to actually pursue social improvements, in some contexts more efficiently than the government might. Consider the examples of Bharti Airtel, Tata Motors, and Hindustan Unilever, where company leaders were determined to build their company’s capacity to provide inexpensive mobile services, automobiles, and consumer goods to millions of traditionally underserved people of modest means.

Of course, self-interest is not far from the surface. For B. Muthuraman, managing director of Tata Steel, social responsibility includes a reputational asset. “Our history in corporate social responsibility,” he affirmed, has “enhanced the group brand.” And for some, acting responsibly in the eyes of the regulators may be a matter of necessity. Obtaining industrial licenses and environmental clearance in the U.S. can be a straightforward, if technical, process, while in India it can also be dependent on a reputation for public responsibility.

But the commitment goes well beyond a private calculus. Rakesh Mehrotra, managing director of Container Corporation of India, put forward what is essentially an Indian version of the “stakeholder” model of corporate governance, where business decisions strike a balance between the interests of those who are affected by the company. Indian business leaders, Mehrotra asserts, were not driven by “solely profit motives,” as were so many of their American counterparts. Rather, they carried a self-conscious commitment to give back to society. “The three p’s of the Indian style of management,” he said, “are people, planet, and prosperity.” His own company set up a major transportation center near New Delhi, simultaneously investing in a host of social services, including schools, social centers, and health-care facilities to give nearby residents “a feeling that we are not there only to earn profits and run our business but also to care for the community at large.”

Our interviews found that the country’s business leaders had comfortably embraced a values-based approach to running companies centered on this concern for multiple stakeholders and their needs, not just the narrower needs of shareholders. To the obligatory role of monitoring management, Indian company directors added the role of guiding top executives, and doing so on behalf of more than one constituency. That dual-purpose service could be seen in the kinds of directors that the companies recruited to their boards, evident at Infosys and Mahindra & Mahindra, and in the ways that directors served as strategic partners, not just shareholder monitors. The multiple-constituency ideology also appeared as a driving commitment in a range of other business practices, from competitive strategy to company culture, and from talent management to personal leadership.

An important advantage of the India Way as model for business, at least for society, is in this area of governance. Keeping the activities of companies from damaging the societies in which they operate is a major challenge. Businesses that follow the financialization model and see profit maximization as their overwhelming goal always are tempted to act in ways that increase profits at the expense of the community (e.g., pollution, which can lower company costs but damage the community). To counter these incentives, governments typically impose elaborate systems of regulations and monitoring. But regulations are imperfect instruments, and both the monitoring they require and the constraints they impose on business are costly. When businesses begin with the broader interests of society as part of their goals, as happened so often among the companies we studied, they sharply diminish the need for regulation and monitoring. (See “Will the India Way Persist?”)

Will the India Way Persist?

The practices behind the India Way have a long and clear intellectual lineage. Motivating through a sense of mission, for example, empowering employees, and staying close to customers have proven records. And the India Way companies are already succeeding against the best in world competition. Skeptics might argue, though, that while the India Way has succeeded so far, it is just a phase along a path of economic development. That the mission-driven approach of Indian companies and the focus on employees in particular is fostered by the values of company founders and their families, and won’t last when the founders leave and professional managers take over. We know from countries with much older corporations, however, that the initial cultures of companies persist well past the departure of founders. More generally, cultures continue as long as they are perceived as being useful.

A related objection to the long-term viability of the India Way is the argument that it persists only because Indian business has been insulated from the demands of the international investment community for short-term profits. Yet Indian businesses are already subject to those pressures. Many are listed on international stock exchanges, most raise funds in international markets, and virtually all are measured and rated by international investors. Companies ultimately control how much they are willing to bend to the interests of the international financial community, and so far, the India Way directors and leaders have chosen not to pursue the interests of the investment community as their own objective. The assumption that they will eventually have to, that all businesses will eventually conform to the U.S. model, has been a hotly debated topic about which there has been no consensus.c But those who believe in convergence on U.S. terms have had their case considerably weakened as a result of the 2008–2009 financial crisis.

It is also possible that India’s well-performing companies will simply lose steam, as many high-flying companies do in most contexts.d Some of the successful companies featured by Thomas Peters and Robert Waterman in In Search of Excellence, for instance, regressed during the ensuing decades toward middling performance.e While we have highlighted the views of Indian leaders on the distinctive practices they consider most vital for explaining their growth, time will tell whether their companies can stay on top.

Yet a different question is whether Indian voters and politicians will lose patience with the India Way. Despite the extraordinary success of Indian corporations, the bulk of India’s people remain mired in grinding poverty, with more than 300 million still living on less than one dollar per day. Infant mortality has stayed high, with fifty-seven deaths per one thousand live births, compared with seven in the United States. India’s mushrooming middle class is increasingly estranged from the village life of the vast countryside, creating new divisions. Further, corruption in government but also in the business community has remained commonplace in India. Drawing on 2007–2008 surveys, Transparency International ranked Denmark, New Zealand, and Sweden as the world’s least corrupt countries. Of 180 countries, it judged the United States as eighteenth, but it placed India at eighty-fifth.f While a return to the socialist past is unlikely, whether regulations and restrictions will be imposed on businesses and the economy that alter the India Way is an open question.

Contrasting Stockholder-centric Management with Stakeholder Management

The stakeholder-based orientation of the India Way suggests the notion of compromise and mediation between goals, in particular backing off from actions that might make the most money for the business in order to pursue some other goal, such as protecting the community or helping employees. This approach would always appear to do worse in terms of financial performance than the financialization model described earlier. What could be better for profits than focusing on financial performance as the overriding goal?

Yet, as we have seen, there are many problems with the way the financialization model has played out. The notion that companies ought to operate for the benefit of shareholders does not require that companies manage toward quarterly profit targets the way many do now, for example, nor does it require that they ignore the interests of other stakeholders. It is not obvious that this approach even maximizes long-term financial outcomes for shareholders, as its short-term orientation misses both opportunities and potential landmines along the way.19

Even if we ignore the problems of the financialization approach, compelling reasons exist for believing that the India Way can not only compete with the U.S. model in terms of financial performance but might even beat it. One reason, described in detail in chapter 3, is that the India Way has a big advantage in motivating and engaging the efforts of employees. Exciting employees about making shareholders rich is an ongoing challenge. While it is possible to tie pay to shareholder value, it is extremely expensive to pay the average employee enough in share-based incentives to get them to focus on shareholder value. And as the financial scandals in the United States continue to illustrate, linking the pay of executives to financial performance entails substantial governance risks. It is much easier to get frontline employees animated about a social purpose, and it is easier to keep them engaged around an organization that has a sense of mission. A recent study of employee turnover in India found, for example, that the perception of a company’s social responsibility is one of the main factors in retaining talent .20

A second factor giving the India Way an advantage in performance has to do with customers. Individuals have long memories, and doing good things for people when they have no money and are not customers for your products can redound to a company’s advantage when those individuals do have money and are in the market for your products. We also know that consumers care about the values of the companies with which they do business—witness the current rush of companies touting their “green” environmental practices. At least some substantial share of customers would rather do business with companies that do good things for the community.

A third important factor that favors the India Way concerns the holistic engagement Indian companies typically have with their employees. This often translates into a concern for the employees as whole persons, not just as individuals with whom the company enters into instrumental exchange relationships. While pressure from competition in the labor market threatens to erode that mindset, concern for the human system still describes the management practices of many Indian firms. This approach can create greater identification for employees with their companies, increase their motivation to put in efforts beyond role requirements, and create a supportive, high-performance culture. While this view of employees as members of one large family is anchored in Indian culture, one of its roots ironically lies in U.S. management theories from the 1950s and 1960s and management practices during the 1960s and 1970s that emphasized the human equation. There is a notable parallel to the emphasis on quality control, which originated in the United States during the 1950s through the advocacy of W. Edwards Deming and Joseph M. Juran, that found its fullest expression not in the United States but in Japan, eventually becoming a central pillar of Japanese manufacturing management practice.

Can the India Way Translate Elsewhere?

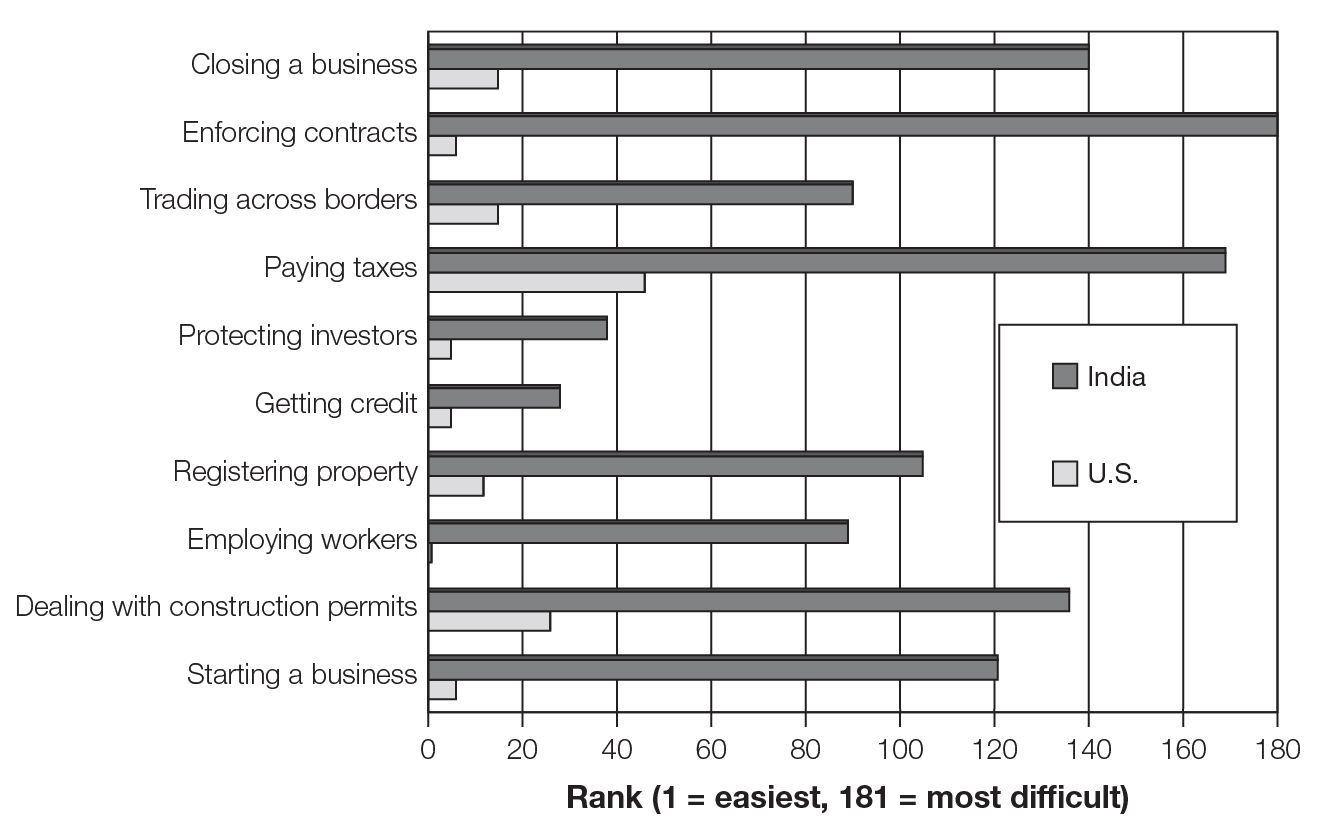

How adaptable is the India Way model to other cultures and economies, and how much is it the product of the unique context of Indian business and life? There is no question that the Indian context is different. Consider a World Bank assessment of the ease of doing business in 181 national economies, ranging from Australia to Tajikistan. The ranking took into account the challenges in ten stages of a company’s development, ranging from founding the firm and securing credit to obtaining permits, protecting investors, and enforcing contracts. In 2008, Singapore stood first, followed by New Zealand and the United States. China ranked near the middle at 83, but India fell among the lowest third, ranked at 122. On all ten criteria, Indian firms faced more challenging conditions than companies in the United States, as seen in figure 7-1.

Rank of the challenges of doing business in India and the U.S., 2008

Source: World Bank, Doing Business 2009 (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2009), http://www.doingbusiness.org/.

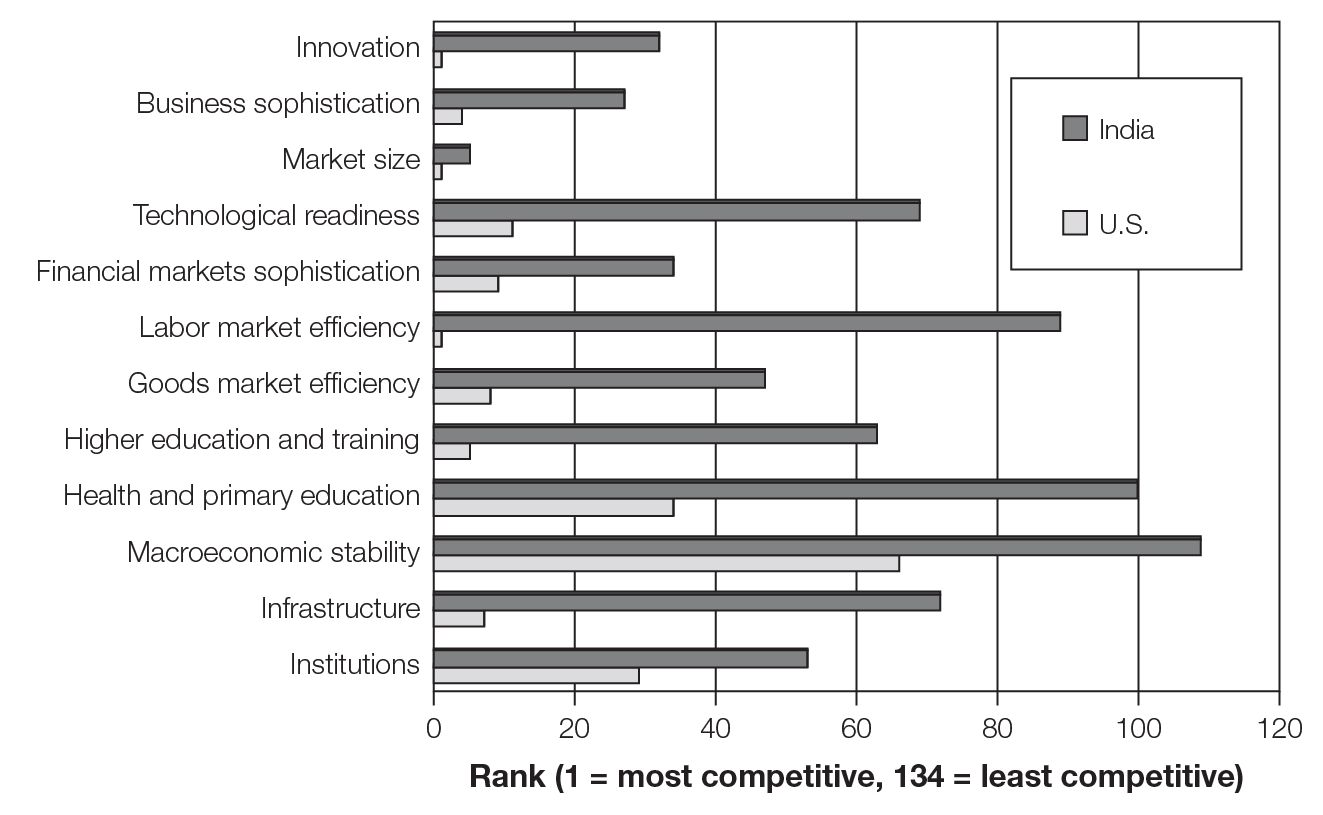

The relative competitiveness of the Indian and American economies also displayed the same wide disparities. The World Economic Forum annually assesses country competitiveness, defined as the presence of institutions, policies, and related factors that determine a nation’s productivity. The forum took twelve factors into account, and, as seen in figure 7-2, it ranked India far below the United States on all twelve. Overall, the United States placed first, followed by Switzerland and Denmark, while India finished fiftieth among 134 nations.

Moreover, the relative competitiveness of the Indian economy on these dimensions had shown no marked improvement over the past decade, at least as gauged by the World Economic Forum. For the ten years from 1999 to 2008, the Indian economy bounced around in the competitiveness ranking, from 43 to 57. When business leaders were surveyed in 2008 as part of the forum’s analysis, Indian executives said that the most problematic factors for doing business in their country were inadequate supply of infrastructure, inefficient government bureaucracy, and corruption.21 India Way companies take on more community responsibilities perhaps because they need to in order to get business done. They have to spend more time and resources training employees, for example, because the schools and private training institutions are not up to the job. They work to improve the infrastructure of their communities because it is difficult to get business done in them otherwise. Whether the investments in employees and in the communities would be as useful in countries where the infrastructure is better is an open question.

Rank of country competitiveness for India and the U.S., 2008

Source: Michael E. Porter and Klaus Schwab, The Global Competitiveness Report 2008–2009 (Geneva, Switzerland: World Economic Forum, 2008).

All countries face challenges in the public realm, of course, and it is hard to argue with the idea that societies are better off if the business community is actively engaged in helping address those challenges. In prereform years, business leaders were “shunned and treated with disdain,” recalled Emcure Pharmaceuticals’ Humayun Dhanrajgir. In the wake of the 1991 reforms, Indian companies came to play a more prominent role in addressing India’s enormous social ills. Many in India’s government came to recognize not just the private sector’s ability to generate surplus but its strongly felt obligation to help alleviate India’s deep-rooted social ills. Now, business leaders were warmly welcomed into the corridors of power, serving on a host of advisory bodies and consultative boards. Instead of treating companies as little more than license supplicants, government officials came to see them as policy allies, turning to them for help in addressing the problems of infrastructure, poverty, and beyond. Witness how Prime Minister Manmohan Singh asked Anil Ambani to remain in the country to help calm the nation in the wake of the 2008 terrorist attack on Mumbai. A U.S. analogy might be found in the frequently misinterpreted comment by General Motors’ chief executive Charles Wilson on how he focused his company on the war effort during World War II: “For years I thought what was good for the country was good for General Motors and vice versa.” But more recent parallels do not come to mind.22

In fact, Indian business leaders did not wait for government to come asking for assistance. Indian executives openly thrust themselves into public dialogue over societal goals and the future of the Indian economy. Mukesh Ambani, for instance, used a business-law conference in 2009 to urge the audience to focus not on business or legal matters but on the fact that at a time when the world’s population was aging, India’s was actually becoming younger, with more than 400 million people below the age of nineteen. If properly trained and employed, he said, India’s young could become a source-country, not just a company, advantage.23

Bill Gates recently called for a new approach to business, a new form of capitalism where business aims to solve social problems and not just make money, an approach that sounds remarkably like the India Way. At least so far, there have been few takers in the United States. Few business leaders stepped forward to help guide America through the economic crisis of 2008–2009, standing in sharp contrast, for example, to the role, albeit a controversial one, played by banker J. Pierpont Morgan in reversing a financial crisis a century earlier .24

But the India Way is more than simply social responsibility. It is an approach to business strategy, to the pursuit of competitive advantage. Social responsibility fits into that approach, but it is only part of the model. And as we described in chapter 2, while the India Way is not a direct transference of Indian values and norms, it is rooted in a legal, cultural, and economic context. How much of the India Way can translate to other contexts? More to the point, if you are a business leader in another society, where the infrastructure and values are different, what aspects of the India Way can be applied to your operations?

The India Way As a Guide for Individual Leaders

The question about what translates is most pressing for leaders of publicly held companies in the United States—the big enterprises—as they operate in a business environment where the pressure to manage in ways that maximize shareholder value is intense. They cannot be expected to drop the focus on shareholder value and operate like Indian companies. What we argue, though, is that even publicly held U.S. companies need to push back against at least the extreme versions of the shareholder-value approach, the idea that the company ought to be managed in order to produce high and predictable profit levels every quarter. Instead, they need to create at least enough space from the short-term pressures of quarterly profits to be able to operate and execute business strategy.

The problem with the short-term approach to maximizing quarterly profits is that it ends up having everything about the business operate backward: rather than setting out a strategy for competing, making investments to execute it, and then earning a return, this extreme version starts with a target rate of return and then adjusts everything about the way the business runs to achieve that return each quarter. Investments, programs, even strategies end up changing quarter-by-quarter in order to hit the target. This approach makes it almost impossible for a company to sustain any serious business strategies as the company itself has to constantly adjust to accommodate the variations and uncertainties that come from the markets.

Being able to sustain any kind of competitive strategy requires taking a longer-term perspective, and here again we find an advantage for the India Way. The most fundamental attribute of the India Way is that it offers a distinctive model of business strategy, a way to compete and succeed in the marketplace, and a different way of thinking about strategy than we see in most U.S. businesses. As we described in detail in chapter 5, leading Indian companies look for the source of competitive advantage internally, developing competencies that make them capable of solving the hard challenges presented by their customers. U.S. companies tend to be focused more outside the firm, looking for value in mergers and acquisitions, chasing new customers, or exploring new markets. Researchers in the field of business strategy talk about the distinction between spending resources on exploration versus exploitation, on seeking new opportunities versus pursuing them in depth.25 India Way firms focus on the latter, while their U.S. counterparts concentrate on the former.

There are reasons for thinking that exploitation has become more difficult as the economy becomes more global. It is more difficult, for example, to find opportunities where competitors are weak (the classic exploitation strategy) once markets are open to global players. It is also more difficult to move operations around in search of cheaper labor given that so many competitors have already done that, bidding up local labor costs. Because of this, researchers who study strategy have come to see the sources of competitiveness as more often being inside the company, as with the India Way companies, with competencies that allow them to do things that their competitors cannot.

In focusing on their internal competencies—on their employees and their skills—Indian executives can do things their competitors cannot. They can direct strategy at the core needs of long-term customers and execute strategy through persistence and adaptability. They can see their task as knitting these components together, focusing on aspects like articulating a social mission and building organizational culture as part of the glue that makes an internally focused strategy possible.

What does all this mean for business leaders? How can they adapt the India Way approach to business strategy?

The first point to keep in mind is that company leaders have enormous power over what organizations do, perhaps most importantly by directing the attention and energy of their organization. Given that, the place to begin adapting the India Way is for leaders to pay attention to the process of creating strategy, to focus the energy of the business on that task. A simple way to do so is for the leaders to ask this question: what are we better at than our competitors? In businesses that do not have an internal focus on strategy, this is a hard question to answer, and it provokes much soul searching when managers are quizzed by the chief executive. Succeeding with the India Way approach begins by developing a good answer to that question, finding something that your business is better at than its competitors. Then the task of leaders is to keep the focus on that competency: communicating the idea that we are good at this task, and it should be the focus of the way we compete with customers. When the India Way leaders reported that setting strategy was their number one priority, they meant this process of getting the business focused on the competencies that drive its competitive advantage and keeping the organization from wasting time and effort on other priorities.

The focus on internal competencies may seem to raise another question: what creates those competencies? But the answer to that is always the same: it is through people, through hiring the right ones, developing talent internally, and especially engaging the energy of employees with a sense of mission, with empowerment, and with an architecture and a culture that reinforce these outcomes. Certainly, as we found in chapters 3 and 4, that is true of many large Indian companies.

This takes us to a very practical and tangible list of actions that leaders who want to borrow from the India Way should take. These actions help build the capabilities that can drive an internal approach to strategy. An important attribute of these practices is that it is hard to see a downside to them. They are likely to have a positive impact even if pursued separately.

- Establish the sense of mission. The chief executive and the top leadership team are the only ones who can establish a social purpose for businesses: what are the positive effects our business has on the broader community? Not all businesses can come up with an answer to that question, but merely asking it again focuses the attention of the organization. It is easier to engage employees around social mission than around the goal of making a shareholder rich. Some businesses have an easier time creating a sense of mission. Pharmaceutical companies like Amgen and Johnson & Johnson, for example, routinely describe their purpose as saving lives and use that purpose in their recruiting. Even those whose business operations are not focused on a social purpose can create something similar, even if done as an ancillary activity. Home Depot, for example, was widely praised for its support of U.S. Olympic teams and of individual athletes. The company reported positive effects on employee morale as well as on customer reactions.

- Engage employees. This idea begins with recognizing that the motivation and commitment of employees is not something that should be taken for granted. It has to be secured. Ordering employees to do something will certainly get them to do it, but getting their full effort and energy is another matter. The India Way leaders take employee engagement seriously, and their effort begins with communication: explaining the challenge and the need for the solution. As we saw with the example of Bank of Baroda, this process can often be one of persuasion, with the leaders meeting with employees to listen to concerns and answer questions. The last step in the process of engagement is to truly empower employees: letting them come up with solutions and—this is the hard part—trusting those solutions enough to try them out even if the leaders don’t agree.

- Manage the culture. Organizational culture is the implicit norms and values that tell people how to behave. Culture is revealed by looking at how things actually get done. In most companies, it is created unconsciously. The leaders may talk about wanting to change the culture, but they do nothing about it. India Way leaders, in contrast, make it a top priority. They focus attention on having a culture that reinforces the behaviors they want in the organization. Perhaps the most powerful way employees learn about culture is to watch what the leaders do. That is why so many of the India Way leaders said that a priority for them is to act as a role model for employees. No doubt most chief executives think that they are models in terms of the amount of work they do. But are they also role models in terms of the level of perks they enjoy, how much they are paid, and how they deal with others in the organization? Recall the model of Vineet Nayar of HCL, who posted his own 360-degree feedback evaluation on the company’s Web site for all to see. Would other executives be equally willing to do that?

- Focus on alignment. To get the most out of these practices, it is important to think about how they fit together: are the culture and the mission of the organization aligned, and most important, are we managing these aspects in ways that reinforce our competencies as a business? It is possible to have a wonderful strategy, a profound mission, and still have a failing organization because these attributes are not supporting the strategy of the business. The chief executive and the leadership team are in the unique position of being able to see whether the individual practices of the organization align and drive the competencies the organization needs in order to pursue its approach to business, and, if those practices do not align, to fix them.

These practices are not that novel. But when we look at contemporary businesses elsewhere, especially in the United States, we see quite different patterns. American chief executives focus much of their attention outside the operation—dealing with investors and regulators, looking for opportunities for mergers and acquisitions and for new businesses, often delegating strategy to a staff function. U.S. companies rarely have a sense of social mission at their core, and their leaders do not see managing culture and engaging employees as personal responsibilities. The era of charismatic CEOs with personal brands and high profiles in the outside community stands in stark contrast to the India Way leaders, who expect to be role models in their behavior for individual employees. These differences help explain why India Way companies focus on long-term customers because those relationships are at the heart of the organization, why they see themselves as extended families with mutual obligations, and why they bang away at hard, persistent challenges until they crack them. They also explain why U.S. companies see their competitiveness as centering on the opposite of persistence, the ability to change in response to new opportunities with a “free agent” workforce and a leadership team focused on the outside environment.

In Closing

The experience of Indian business—and the roaring success of the Indian economy—points the world toward a different enterprise model. Rather than wholeheartedly embracing American-style “unbridled capitalism,” the India Way seems to have settled voluntarily on a more bridled version. The nation’s leading business figures, we found, were pursuing strategies not strictly tethered to the disciplined pursuit of private profits. Threaded through their accounts was an accent on the long-term benefits not just for their company but also for the country. Asked what they would want to constitute their single most important legacy when they stepped down from their company’s leadership, more often than not these leaders mentioned societal benefits. Meanwhile, the distinctive features of the Western model—the riveting focus on shareholder value to the exclusion of other values, the reliance on financial incentives to entice executives to pursue that goal, and the overall belief that the pursuit of self-interest in this manner will ultimately benefit society, eliminating any need for public oversight—have all come to be questioned by the most mainstream of voices, especially as economies eroded around the globe during the 2008–2009 recession.

We have identified key components that make up the India Way, but arguably its critical aspect is the fact that the separate components are integrated into a coherent model. The tight fit between the way executives lead their employees and the way they pursue business strategy allows them to identify a social purpose and match it to business needs. The ability to perform this integration stems from the leaders, who act as the equivalent of choreographers or conductors, knitting these components together through their ability to articulate missions, communicate them to employees, manage organizational architecture and culture, and more generally set priorities. In this way, the whole of the India Way becomes greater than the sum of its individual practices. Focusing on these challenges inside the organization may be the greatest point of difference as contrasted with Western business leaders.

The most important lesson from the India Way might therefore be the light it shines on the American way, at the moment arguably the dominant model for business. The India Way demonstrates the power of collective calling over private purpose, of transcendent value over shareholder value. These ideas are hardly unknown in the United States and indeed were common a generation ago. In the wake of the greatest collapse of American business confidence in more than seventy-five years, the time may be ripe for U.S. company leaders to move back to the future.