CHAPTER THREE

Managing People

Holistic Engagement of Employees

NONE OF THE INDIAN BUSINESS leaders we interviewed claimed that their company succeeded based on his or her own cleverness or even on the efforts of a top team. Almost without exception, Indian business leaders—and the industry analysts and business journalists who follow their companies—described the source of comparative advantage as coming from deep inside the company, from new and better ideas, superior execution, and the process of jugaad that gets things done. And these outcomes, in turn, were traced to the positive attitudes and behaviors of employees. The obvious conclusion: the source of the distinctiveness of the India Way and the ability to focus the business on solving hard problems rests heavily on the management of people, on the holistic engagement with employees.

Motivated and committed employees hammer away at problems and persist until they find creative solutions and workarounds that solve tough problems. That seems straightforward. But what makes them want to do that? As noted in chapter 1, having a sense of mission and social goal for the organization helps employees see a purpose in their work that goes beyond their immediate self-interest, beyond the achievements of the firm and its owners. Typically, that sense of mission extends to helping India and its citizens. The Indian firms included in our research motivated employees at least in part by connecting their work to these broader social goals—improving phone service for rural customers, expanding access to health care by lowering its cost, enhancing the competitiveness of the overall Indian economy. This sense of mission tapped into what organizational psychologists call task significance, seeing the link between the sometimes small tasks they perform and the bigger goal. President Lyndon Johnson loved to tell the story about asking a truck driver working at NASA in the 1960s what his job was. The driver’s response: “I’m helping to put a man on the moon.” That’s task significance.

Beyond the sense of mission lies the management of employees. Indian companies, we found, built employee commitment by creating a sense of reciprocity with the workforce, looking after their interests and those of their families, and implicitly asking employees to look after the firm’s interests in return. To translate commitment into action, the business leaders went to extraordinary lengths to empower employees in a way that often conflicted with historical norms, giving them the freedom to plunge into problems that they encounter and create their own solutions. Then they devoted a great deal of executive attention and resources to the practices that support this approach, such as finding the right people to hire, developing them internally, and improving morale. Business leaders directed their attention to building organizational culture, which shows employees how to perform, and to demonstrating the connection between employee competencies and business strategies.

This is the inside picture of the India Way. In addition to instilling a sense of mission, management practices help produce the engagement and motivation that allows the organizations to be persistent and innovative. While the companies we studied all focused intensely on hiring, they did not try to compete simply by winning a “war for talent” by hiring “stars” from the labor market. Instead, they leveraged existing human resources through extensive investments in the competencies of employees and in developing them for careers inside the firm.

It would be a mistake to assume that these Indian companies have relied solely on “soft” practices like culture and commitment. Our research revealed that they are sophisticated about other human resource practices as well. Extensive diversity programs, for example, were common as a means to reach a broader labor market. We also found more sophisticated systems of workforce planning and of performance management than are common in the United States. We can see these differences in part with comparative data and by comparing similar companies in the two countries. Where American companies focused their human resource attention more on cost reduction, Indian companies saw their employees more as capital investments that should be supported and managed.

Engaging Employees at HCL

To see the connection between how employees are managed and how Indian companies compete, consider the case of IT services giant HCL Technologies. With fifty-five thousand employees spread across eighteen nations and a broad array of international clients including Boeing, Cisco, and Merck, HCL nurtures its basic DNA by tying long-term business approaches to principles for managing employees. HCL was founded as a computer hardware company in a garage in 1976 and flourished in the early 1990s when the Indian government was still restricting access of multinational competitors to the domestic hardware market. Thus protected, HCL was among the early leaders in Indian IT, offering the highest salaries to attract the best talent. Whether the company would have been able to compete with multinationals, however, was not yet obvious.

Vineet Nayar, a young HCL engineer, was thinking about leaving for a more entrepreneurial environment when he was offered the chance to be an “intrapreneur” in the information networks area. The Comnet subsidiary that he helped create soon became the tail that wagged the dog as HCL moved from the hardware business to software. The division’s distinctive approach to its market, its business strategy, was to empower each individual employee to meet customer needs. To achieve that, Comnet combined an entrepreneurial business environment with extensive investments in employee development and training. Without really knowing it at the time, Nayar was incubating the personnel strategy he would later apply to the entire company.

Employee First, Customer Second

Nayar became CEO of the overall HCL company in 2005 and confronted a market that had become global just seven years earlier, when the government lifted its protections for Indian hardware companies. The growing end of the IT industry was clearly in IT services and software-driven solutions, not hardware. The biggest players in the international marketplace were competing based on scale, using classic “scientific management” and engineering approaches where the same employees delivered the same solutions and where projects were broken down so that cheaper, lower-skilled employees could do the easy parts in order to drive down costs. HCL decided to go a different route. The company opted to move away from the low-cost, high-volume business and instead ascend the value chain by getting closer to existing customers and better meeting their unique needs, another example of the innovativeness and adaptability that are part and parcel of the India Way approach to business strategy.

Nayar began by pulling together groups of younger employees to work on a theme that would reenergize the company and signal both a new way of operating in the product market and a new way of managing internally. The motto they created for their mission—“Employee First, Customer Second”—was meant to shock people and get their attention, but it also reflected the basic alignment between employee management and business strategy that we see across Indian companies. The idea was to give the employees whatever they needed, including autonomy, so that they could meet the unique needs of customers in the field (see “Employee First at HCL”).

An Inverted Pyramid

The corporate pyramid, broad at the base and slender at the summit, with decision-making authority concentrated at the top, has long been the very definition of company organization. Virtually all organizational charts place a CEO box at the top, with everwidening layers arrayed below. A select few reach the highest offices, and their job is to hold the lower levels accountable for results. But HCL Technologies, metaphorically speaking, sought to invert that pyramid by making, as Vineet Nayar told us, “our managers accountable to our employees.”

One tactic was to encourage employees to submit electronic “tickets” on what needed to be changed or fixed, even the very personal, which ranged from “I have a problem with my bonus” to “My boss sucks.” Employees posted comments and questions on a “U and I” Web page, with Nayar himself publicly answering some fifty questions a month. An even more unusual tactic was to require 360-degree feedback on the fifteen hundred most senior company managers worldwide, including the chief executive himself. Employees had the option of evaluating not just their boss but also their boss’s boss and three other managers. And the 360-degree feedback, including the CEO’s, was posted on an intranet Web site within several weeks—for all employees to see, all of it, the good and the bad. Nayar led the way, and soon all the executives posted their own 360-degree feedback assessments by others online as well. As he told us, “Our competitive differentiation should be the fact that we are more transparent than anybody else in our industry, and therefore the customer likes us because of transparency, employees like us because there are no hidden secrets. So we built transparency.” The idea of performance improvement became more broadly acceptable, and the heightened personal transparency at the top served to reduce the sense of vertical separation.

Employee First at HCL

Vineet Nayar, HCL’s CEO, told us that “people are a very important component of an Indian CEO strategy,” which is based on “people development and long-term engagement of people.” He outlined an approach at the company where serving the customer starts by taking care of the employees who service those customers. Here’s what the company says about this approach:

Employee First: The service industry, from fast food to business consulting, has long lived by the mantra that serving the customer is the only thing that matters. As a result, customer need is placed above all others—often at the sacrifice of employees, managers and administrators. HCL Technologies, one of India’s fastest growing IT services companies, has embraced a new strategy—Employee First—that places the needs of employees before the needs of customers. This seemingly counterintuitive strategy has provoked a sea-change at the company and, believe it or not, greater customer loyalty, better engagements, and higher revenues.

The main point, Nayar said, is “if you are willing to be accountable to your employees, then the way the employee behaves with the customer is with a high degree of ownership.” At HCL, Nayar contended, “command and control” is giving way to “collaborative management.” To that end, he has pushed for ever “smaller units of decision makers for faster speed and higher accuracy in decisions” to provide HCL’s customers with more timely and customized service.

Given the pace of industry growth and its dependency on headcount, attracting, retaining, and motivating talent is the top challenge for the industry. The traditional approach viewed employees as commodities and placed emphasis on deploying entry-level talent and a factorylike approach for project execution. There were no unique engagement strategies centered on the employee ...

To make the Employee First concept work, HCL launched a variety of internal initiatives designed to both give employees more personal responsibility for the company’s service offerings and a voice with upper management. HCL’s enlightened approach to employee development focuses on giving people whatever they need to succeed: be it a virtual assistant or talent transformation sabbaticals, expert guidance or fast track growth, inner peace or democratic empowerment. At HCL, what we have is Five Fold Path to Individual Enlightenment. This ensures they are given Support, Knowledge, Recognition, Empowerment, and Transformation.a

Vineet Nayar had worked his way to the top of HCL Technologies after twenty-one years, and after his one-year anniversary as company president, he wrote all employees, “I am here as long as I have your support and confidence.”1 As much as half of his time has been spent in town hall meetings with all the company’s employees, communicating this vision for the company and managing the corporate culture. He made it a personal goal to shake the hand of every employee every year, and when asked what he would like to be his greatest legacy to the company in five years, Nayar responded without missing a beat: “They would say that I have destroyed the office of the CEO.” Pressed to explain, he said he sought so much “transparency” and “empowerment” in the company that “decisions would be made at the points where the decisions should be made”—that is, where the company meets the client. Ideally, the “organization would be inverted, where the top is accountable to the bottom, and therefore the CEO’s office will become irrelevant.” His public blogs on the company Web site included a posting in 2008 entitled “Destroying the office of the CEO.”2

As HCL’s chief executive, Nayar warned, “Don’t believe that you are God’s gift to mankind. I do believe that the rest of [our] people are smarter and greater [and] better than you. So as long as you go to sleep assuming that you have 48,000 smart people, you will sleep well. The day you start believing that you are the smartest, I think you will get it wrong.” In 2006, Fortune magazine dubbed the executive team at HCL Technologies the “world’s most modern management.”

Trust Pay

One of the most interesting and perhaps controversial aspects of HCL’s people management practices was to move away from the traditional practice in IT companies of having 30 percent of an employee’s pay at risk, based on the achievement of “stretch goals” for individuals or their groups. In practice, these stretch goals are rarely achieved, at least completely, which means that the employees end up earning less than their full salary. HCL referred to its new arrangement as trust pay, which reinforced the idea of reciprocity: we’ll pay you the full salary, and we expect you to do your utmost at all times to meet your goals. To help model this new approach, HCL created an elite Multi-Service Delivery Unit, a separate organization to tackle the most important client assignments. Competition for election into this unit was intense and involved assessments based on personality as well as business and technical capability.3

Human Resource Priorities

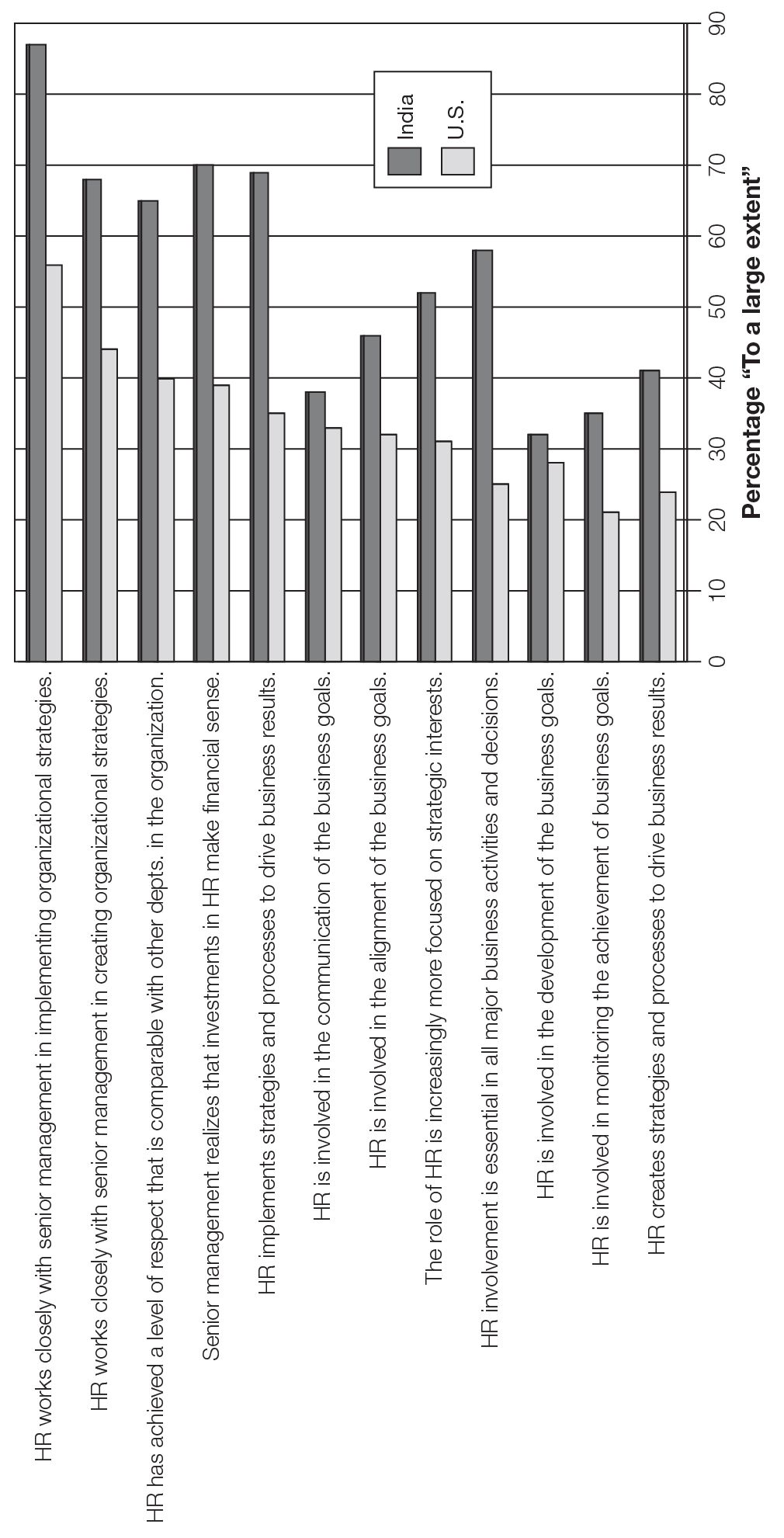

HCL focused so much attention on managing employees because its business strategy centered on their behavior. That might seem axiomatic for most companies—Indian and American—but our survey of top human resource executives found that Indian firms were far more likely than their American counterparts to closely intertwine HR management and business strategy. Indeed, as shown in figure 3-1, on every one of the twelve dimensions of engagement in organizational strategy, Indian company HR roles outstripped U.S. company ones, in the majority of cases substantially so.

Sixty-eight percent of the Indian human resource executives reported that they were closely involved in creating strategy with the other top leaders in their companies versus 44 percent in U.S. companies. In terms of implementing strategies, virtually all Indian HR heads—87 percent—said that they worked closely with the top management team, as compared with 56 percent in the United States. Particularly striking was the relatively large percentage of those in the United States who reported that they were not at all involved in these decisions, ranging from 6 to 30 percent on the twelve practices, compared with 0 to 10 percent among the Indian companies.

The Indian business executives were overwhelmingly of the view that competitiveness derived from people, not just for their own businesses but for India as a whole. As Mukesh Ambani of Reliance Industries observed, “The strength of India is really in the depth of talent that we have.” Anand Mahindra of Mahindra & Mahindra noted, “It’s not the lowest cost per unit of output or service that India is known for. It should be known for the lowest cost per unit of innovation because it is people plus our ability to innovate that is India’s strength, and I would want our companies and our businesses to embody that.” And as S. Ramadorai of Tata Consultancy Services concluded about his company’s success, “It’s all human capital at the end of the day.”

Extent of human resource’s involvement in the organization

Sources: Survey of Indian companies, and Society for Human Resource Management, Strategic HR Management Survey Report (McLean, VA: Society for Human Resource Management, 2006).

This view extended to the leaders of all the companies. When we asked the Indian business leaders the details about their priorities for human resources in their companies, the results were consistent with an employee-centric view. Our question was open ended—executives could say anything they wanted—yet with remarkable consistency, the responses centered around four themes:

- Managing and developing talent

- Shaping employee attitudes

- Managing organizational culture

- Internationalization

Far and away the overwhelming majority of responses fell into the first of those categories: managing and developing talent. The single most commonly used phrase in this context was “employee retention,” followed by “recruiting” and “developing talent” internally, the core issues in talent management. Indian business leaders by and large saw no trade-off between recruiting and development, and they expected their firms to pay attention to both.

The second most common response reflected the concern with employee attitudes. The company executives wanted their human resource functions to manage employee engagement, one of the key pillars on which the India Way operates. Managing organizational culture, a third priority, might seem at odds with the high priority executives set for themselves on shaping culture, but the clear conclusion is that they are not delegating the task to the human resource function. They embrace culture management as their priority, to be supported by human resources.

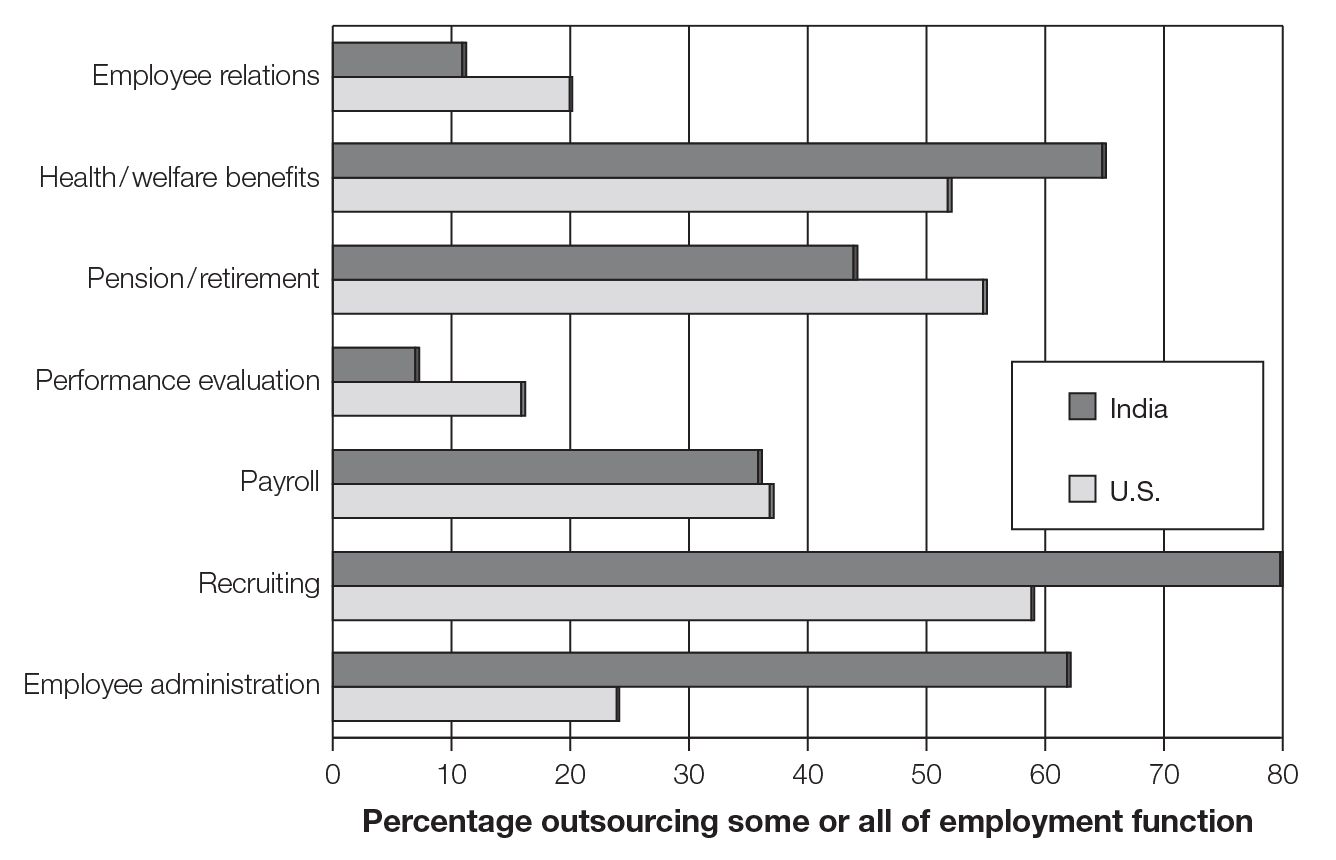

Compared with the United States, the most interesting finding in this area was what the business executives did not say. Among American firms, the human resource function has been continuously pressed to lower costs, to find savings in all areas of operations through outsourcing, squeezing health care savings, and the like. Indian company leaders never mentioned cost reduction as a priority for human resources. A cynic might argue that labor costs were already lower for Indian companies than for their competitors, but the costs were rising far faster in India than elsewhere, and these firms were increasingly competing with each other. Another possible explanation might be that Indian firms do not have the cost-cutting outsourcing possibilities that existed in the United States—a longtime preoccupation for American human resource executives. But that proved not to be true, either. As we see in figure 3-2, Indian companies actually outsourced the human resource operations on a par with those in the United States. When it came to recruiting, payroll, pension and retirement, and health and welfare benefits, more than a third of the companies in both countries outsourced their operations.

Company outsourcing of employment function

Sources: Survey of Indian companies, and Society for Human Resource Management, HR Outsourcing Survey Report (McLean, VA: Society for Human Resource Management, 2004).

Another explanation for the Indian CEOs’ lack of focus on employment costs might be that there was something like a natural evolution of practices with respect to managing people: as employers get more sophisticated and advanced, perhaps they become better able to measure outcomes so that they can focus on “hard” outcomes like costs. The well-known phenomenon that “what gets measured gets managed” is certainly true. Without the ability to measure factors like costs, it is difficult to manage them. But what gets measured also reflects the priorities of the organization: virtually anything can be measured if one is willing to put the effort into it.

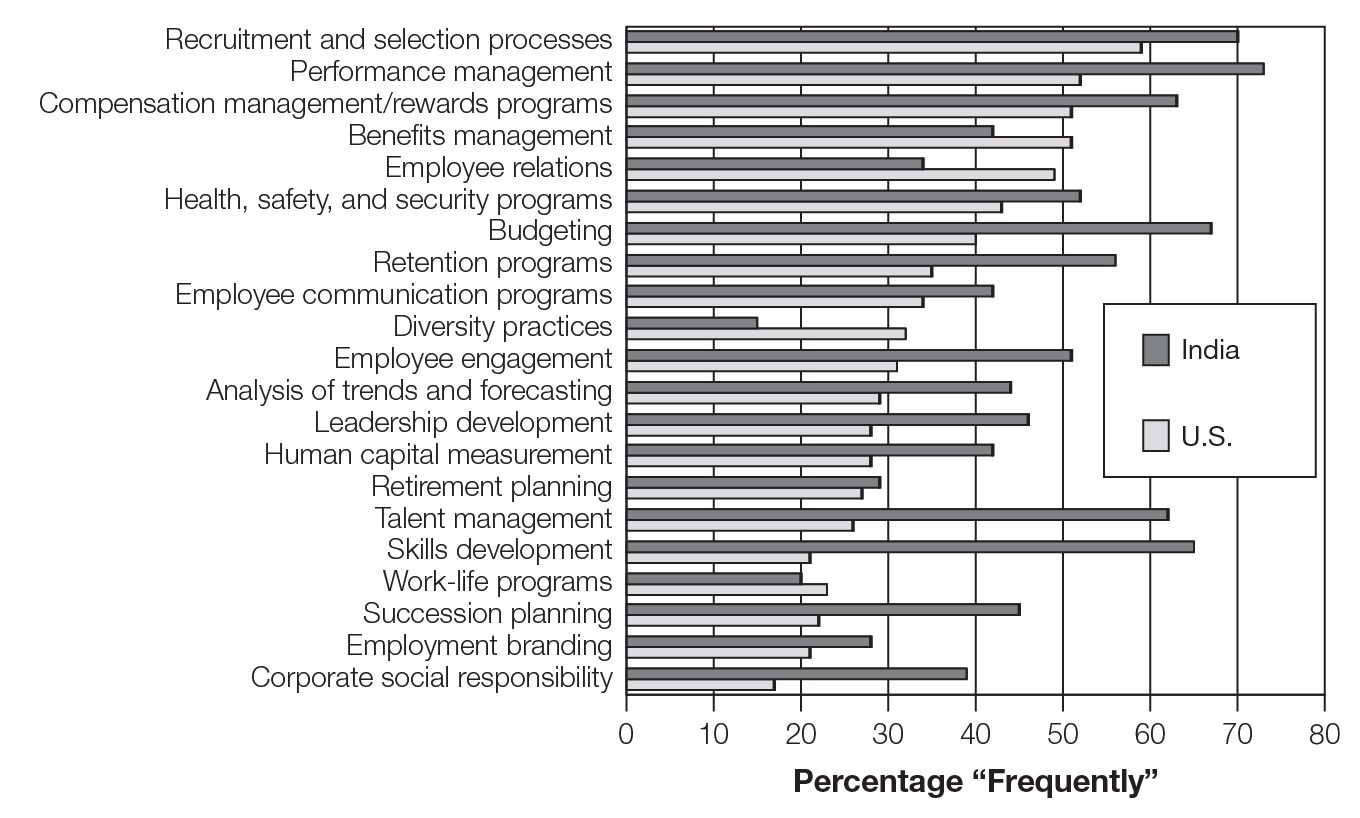

To get at this issue, we asked Indian companies about the metrics they used to assess the performance of employees and aspects of human resources. In the United States, metrics are often seen as a measure of the sophistication of an HR function. The results in figure 3-3 suggest that the Indian firms were more likely to measure and track human resource outcomes than were U.S. firms, suggesting that, in fact, HR functions in India were often more sophisticated than those in the United States and more able to focus attention on cost reduction. They just chose not to.

Company use of human resource metrics

Sources: Survey of Indian companies, and Society for Human Resource Management, Strategic HR Management Survey Report (McLean, VA: Society for Human Resource Management, 2006).

What gets measured also tells us a great deal about the priorities within companies. In this case, the differences in metrics used in the Indian and the American companies reflected the much greater interest and efforts that Indian companies placed on developing talent. With respect to simply getting and keeping the best employees, Indian companies were much more likely to track human resource performance. Regarding the recruitment and selection of employees, 70 percent of the Indian companies confirmed that they measure their performance, compared with 59 percent in the United States; regarding retention, 56 percent did so among Indian firms, but just 35 percent among the American firms.

But the biggest differences had to do with internal development: 62 percent of the Indian firms frequently tracked progress in overall talent management, compared with only 26 percent in the United States; 65 percent frequently measured the development of skills of employees versus only 21 percent in the United States; 45 percent frequently tracked the ability to promote from within through succession versus 21 percent in the United States; and 46 percent frequently used metrics to assess the development of leaders versus 28 percent in the United States. By these measures, American companies were simply less interested in employee issues altogether than their Indian counterparts—and especially less interested in developing their own talent. This reflected a much greater “hire and fire” strategy in the United States, a more arm’s-length overall approach to the management of people.

Indian CEOs were not insensitive to labor cost issues, but they did not see their immediate or even long-term competitiveness as being based on labor costs. Instead, they viewed competitiveness and firm goals as moving up the value chain and doing so based on innovation and superior execution. Those outcomes were closely tied to superior talent, motivated employees, and organizational cultures that encouraged individuals to act in the interests of the company. (For a successful example of India Way human resource priorities put into practice, see “Putting People First Makes the Best Restaurant in Asia.”)

A different measure of the priorities held by India Way companies comes from what they tell shareholders and the broader community about their operations. One interesting study of the annual reports in the Indian information technology industry found that the most common mention of any human resource issue—so common, in fact, that it happened on average more than once in each report—was to thank employees for their contributions. The second most common HR mention was to highlight individual employees, typically for their special contributions or sometimes for their life experiences. That was followed in frequency by mentions of employee capabilities and efforts to train and develop employees. And the fourth most common mention was to discuss contributions employees were making to the broader community, outside of their work tasks.

Equally interesting is what was not presented. Despite the fact that labor accounts for far and away the biggest component of operating expenses, human resource costs were never mentioned in these reports.4 By contrast, the annual reports of the leading U.S. information technology companies contained nary a mention of the employees.5

Building Employee Capabilities

We know that India Way companies pay more attention to employee management than their U.S. counterparts, and we also know that their leaders focus on a very different set of priorities for their employees. The people management approach in these Indian companies—holistic engagement with employees and capability building, one of the four primary features defining the India Way—boils down to three distinct sets of practices. The first has to do with investments in the employees, both for current jobs and for internal promotions. The second, as we saw in the HCL case, centers on empowering employees, giving them the authority and autonomy to make decisions and solve problems on their own. And the third, where the business leaders are most personally involved, is to create and manage a culture that pushes employees to act in the interests of the organization.

Putting People First Makes the Best Restaurant in Asia

Bukhara is routinely voted as the best restaurant in India, the best Indian restaurant in the world, and one of the top fifty restaurants of any cuisine in the world. And there are a lot of restaurants in that competition. Vladimir Putin is said to have wanted to eat here three times a day when he was in Delhi, and Bill Clinton, another big fan, got to make bread in the restaurant’s tandoor oven and now even has a dish named after him.

The restaurant did not get its top rating because of fancy decor. The style might be described as rustic: log benches and rough wooden tables. Diners eat with their hands—no silverware. Long bibs protect the clothes of messy eaters. Bukhara takes no reservations, and crowds regularly queue up in the lounge, waiting to get in.

Nor has this restaurant achieved its distinction through innovation, offering the latest new ideas in dishes. The menu has not changed in thirty-seven years. There are many different kinds of Indian cuisines, some with sophisticated sauces, for example, that represent complex blends of unique spices. That is not Bukhara, either. It offers a decidedly simple and straightforward cuisine from the northern frontier that features mainly meats and breads, few sauces and fewer vegetables. The dishes would not surprise anyone familiar with Indian food: shrimp, chicken, and lamb marinated in yogurt and spices and cooked in a hot tandoor oven.

Where Bukhara excels is with execution. Even though the dishes it turns out are similar to what one could get elsewhere, Bukhara’s are just better. Some part of this is through choosing the very best ingredients. But most of it comes from the skill of the cooks. The head chefs at Bukhara have been with the restaurant for more than twenty-five years. The kitchen is organized around an apprenticeship model where beginning employees slowly learn the craft associated with Bukhara’s menu and then spend a lifetime working in the restaurant. How much could there be to learning how to prepare this straightforward menu? The answer, apparently, is a lot, because the dishes are unmatched by the competition anywhere.

The kitchen has another interesting management practice. In most restaurants, staff members cook their own meals, often grabbing them whenever they can between shifts. At Bukhara, the head chefs are the ones who do the cooking for the rest of the staff, as clear an example of acting as a guide for your employees—or “servant leadership”—as you’ll ever find.

The restaurant staff works ultimately for the giant ITC corporation, but the company is smart enough to do what is necessary in terms of salaries and practices to keep the kitchen together and avoid imposing corporatewide policies that would not fit the unique context of this restaurant. There are no commissions or bonus payments for the staff for being the best restaurant in India. Instead, pride in a job well done is the key.

Anil Sharma, vice president for human resources for the ITC hotel and hospitality company, says that the company is not worried about competitors trying to copy Bukhara, despite the simplicity of its concept. Even if one of the head chefs left to start up another restaurant, taking all that knowledge with him, the system and practices in the kitchen that support the execution of the dishes would not be there, and the competitor would not be as good.

What’s the lesson here? The entire business strategy of the top Indian restaurant in the world rests on the ability to perfect and then execute what is otherwise a very simple and straightforward product, something that would appear to be extremely easy to copy. And the ability to perfect and execute, in turn, is based on human resource practices that create the kind of stability and morale in the workplace that makes it possible to learn best practices, standardize them, and then pass them along.

Investments in Employees Begin with Recruiting

Consistent with the India Way’s heavy emphasis on developing talent and making investments in employees, the firms we studied spent a great deal of time and energy making sure that they start out with the right kind of talent. Candidates who lacked the ability to make use of the training and education programs would be a poor fit. But equally important, candidates who did not have the character to respond to broader missions and who would not respond to empowerment were considered bad matches.

Because of its spectacular growth, Infosys was one of the first of the important Indian companies to take on the challenge of recruitment and selection in a sophisticated and rigorous way. Infosys expected to hire almost 10 percent of all the incoming IT recruits in India, so it had the scale to do things right. Somnath Baishya, head of entry-level hiring for Infosys, described the company’s goal: “Recruit the best talent and create a professionally competent, socially conscious, happy, and prosperous team.”6 Like ICICI, Infosys early on established close ties with the schools where it wanted to recruit. When it found deficits in the quality of the recruits, it worked with the schools to improve their programs. Through Campus Connect—a program Infosys runs with three hundred engineering schools across the country—faculty members trained in part by Infosys helped teach a curriculum created by Infosys and supported by courseware the company had placed online.

The recruiting goal at Infosys was not only to find the best talent but to build the “HR” brand of the company, to create the sense that Infosys was the most desirable place to work in India. To do that, the company also targeted the parents and family of potential applicants, marketing the company and the job to them on the theory that close relatives shape the views of potential applicants in important ways. The goal was to get parents to want their kids to work at Infosys.

Looking (and Training) Outside the Box

What did the company look for? Beyond the technical skills of specific engineering recruits, Infosys valued general academic ability—what we might think of as measured by IQ. This was what it tested applicants on, not subject matter knowledge. Because the company hired only 1 percent of applicants, it needed a very large pool of quality applicants. So it began recruiting in fields beyond IT to find better problem-solving skills from a deeper pool of talent. Its Project Genesis reached out to students in smaller towns that had less access to the best education services, to offer career guidance for jobs in the IT industry as well as training to help them get there. In 2007, Infosys drew 1.3 million applications for employment.

The selection process did not stop with hiring. Once hired, new recruits moved to the largest corporate training facility in the world, just short of 300 acres outside of Mysore. The facility could handle six thousand trainees at a time, with plans to quintuple in size. The training center was designed to feel like a college campus; and indeed, when we visited, we were struck by how much the training-session rooms resembled typical college classrooms, a similarity that makes the transition from college to the company as smooth as possible. The fourteen-week training regimen included regular “exams” and assessments that the new hires must pass to continue in the program. Candidates hired from outside India received even longer training, six months, to help them adapt to the Indian and Infosys cultures. Company managers were assessed based on the percentage of new hires in their group who achieved an A grade on these tests, the number who achieved various competency certifications, and the percentage of outside or lateral hires who were rated as “good” in their first review. More senior managers were assessed based on the job satisfaction of their employees and the percentage of leadership positions that had an identified internal successor. Holding supervisors similarly responsible for the achievements of their subordinates was quite common in the United States before the mid-1980s but is now extremely rare.7

Working at Infosys is no picnic, however, as it also demands performance. The company maintains a forced ranking system where the appraisals are scored not only on employees’ task-based performance but also on the extent to which they are keeping their own skills current. The India Way companies as a group take performance management seriously, but perhaps because of greater investments in employees or a more family-oriented culture, they also seem much more focused on improving future performance as opposed to accounting for past outcomes. Consider this description of the performance assessment and review process at the India-based global pharmaceutical manufacturer Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories: “We believe a great supervisor is actually an excellent coach, not just a boss. Our performance management process, ‘PerfECT’, gets our managers to do just that—COACH. It is all about inspiring breakthrough thinking. It is about challenging your limits. It is about an empowering environment to get you to be at your best—ALWAYS.”8 India Way companies were also more engaged in improving and updating their performance management systems, with 81 percent reporting that they had revised their performance management and performance review programs this past year; 58 percent of U.S. companies reported a similar effort.

Hiring and Training at Yes Bank

Hiring talent is clearly a critical component of the India Way, but it is not a substitute for nurturing and developing the talent already in-house. Consider the example of Yes Bank, where employees are also considered key to the business strategy. Incorporated in 2003, Yes Bank grew at a remarkable 150 percent per year through 2007. Not only was the bank ranked number one in India in growth; it also led in efficiency and safety of deposits.

The company’s operating principles are another textbook example of “strategic” human resources. Yes Bank’s competitive advantage as a late entrant into a crowded marketplace was a distinctive, high-quality customer experience. Because frontline employees deliver that experience, the bank worked hard to shape their attitudes and behaviors—shape them but not automate them. The problems customers bring to the branches of the bank are so unique that “scripting” all the appropriate responses is simply not practical. It is equally impossible for anyone but professional actors to project an engaging and friendly persona if they do not feel it, or for the management to stand over the employees and ensure that they act the right way.

All that is largely obvious, but how do you get the employees to create that right customer experience? Doing so at Yes Bank began with getting the right employees, and that started by creating a unique employee value proposition—a set of practices, programs, and organizational culture that attracts the right kind of employees with the right attributes. As a start-up, Yes Bank had no choice but to hire from the outside. It attracted the best and the brightest banking stars by paying top dollar and then by offering far more opportunity and responsibility than one could get at a bigger, more established bank.

Yes Bank kept an intense focus on recruiting, partnering with the best professionals in the field to find experienced hires and spot potential stars among the graduates of the leading schools. Part of the goal was also to hire for the kind of workplace diversity that mirrors the broader society and the bank’s customer base, not just on ethnicity and region but on gender and age as well.

Yes Bank also built strong relations with a select group of universities to help spot the best students and begin growing talent from within. It engaged students in internships, which led to full-time jobs, before the candidates even got to the job market. Then it offered extensive training and development programs, including job rotation to build cross-functional skills. By themselves, these investments are not unusual, but programs of internal development are very atypical among companies that rely so heavily on outside hiring. 9 The success of Yes Bank offers compelling evidence that you can do both.

Training and Development Follows

Once they get the right candidates, Indian companies pour on the training. One study of practices in India found that the IT industry provided new hires with more than sixty days of formal training—about twelve weeks. Some companies did even more: Tata Consultancy Services, for example, had a seven-month training program for science graduates who were being converted into business consultant roles, and everyone in the company got fourteen days of formal training each year. MindTree Consulting, another IT company, extended its orientation period for new hires to eight weeks, combining classroom training, mentoring, and peerbased learning communities. Even relatively low-skill industries like business process outsourcing and call centers provided something like thirty days of training, and retail companies required about twenty days. Systematic data on training among U.S. companies is hard to come by, but the available statistics suggested that 23 percent of new hires received no training of any kind from their employer in the first two years of employment, while the average amount of training received for those with two years or less of tenure was just thirteen hours within a six-month period.10

Satyam is now embroiled in financial malfeasance, but the story of how it went from nothing to a giant business based on the skills of its employees is instructive. Now-disgraced founder and chairman of Satyam B. Ramalinga Raju told us how: “In the past fifteen years, we have seen enormous change take place [in outsourcing], and we have had to reinvent ourselves half a dozen times. Customers are no longer satisfied with the services they can access from the global systems integrators. This means adopting business models that are conducive to distributing leadership and empowering the people who are interfacing with the stakeholders.” To that end, the company embarked on extensive programs to develop the skills of its employees with a model it called full lifecycle leadership, enabling employees to solve customer problems on the ground.11 Satyam received the American Society for Training & Development’s 2007 award for the best company at training developing talent based on this model.

After the Second World War, U.S. companies also had pioneered extensive training programs. Back then, American companies could be confident that they would harvest most of the skills they developed: the job market was tight, so companies had to train to get what they needed. But turnover was kept relatively low through union-based seniority systems and other practices. Indian companies today have much the same motivation—a shortage of specific skills for a rapidly changing world—but they cannot be nearly as certain they will benefit from the specific talent they develop: estimates put employee turnover in the Indian corporate sector at close to 30 percent. While American employers today face far more modest turnover rates, they have largely abandoned investments of all kinds in employees, especially managerial development, for fear that such investments will simply be lost if employees leave. The fact that Indian companies have opted for the longer-term strategy of investing in employees despite the high turnover rates says a great deal about the commitment to employees in the India Way (see “Pantaloon Versus Wal-Mart” for one example).

Developing Leaders and Building Capabilities

Training is designed to help employees perform better in their current job. Development is the far more risky process of helping prepare candidates for new and more challenging duties, particularly management and executive roles. The Indian business leaders we talked with were interested to a person in developing their employees into executives and potential leaders for the firm. Indeed, all the companies examined in this study had extensive programs for promoting internal candidates to the executive ranks. Most all had development centers at least equivalent to virtual corporate universities. In terms of metrics, 46 percent of the Indian companies tracked leadership development using formal measures versus 28 percent among U.S. firms.

Pantaloon Versus Wal-Mart

Comparing India’s biggest and fastest-growing retailer, Pantaloon Retail (India) Ltd., and Wal-Mart, the largest retailer in the United States and, indeed, the world, provides a useful window into the different choices that businesses make about training employees and how those choices affect business strategy. New recruits at Pantaloon for frontline jobs received six weeks of training, including five and one-half days in residence at a company training center followed by five weeks of on-the-job training directed by local store managers. As Kishore Biyani, Pantaloon’s chief executive, told us, “We run a program in the organization which everyone has to go through, called ‘design management,’ which basically trains people to use both sides of the brain,” both “the visual and esthetic side and the logical rational.” After that, store staff received a week of new training each year.b Training is one way the company develops a shopping experience more suited to customers.

Wal-Mart’s store employees had an orientation program; and cashier positions, the most challenging of frontline jobs, had eight days of training. Other employees received substantially less. Training thereafter was rare, typically limited to dealing with new technology or initiatives when they are introduced. Little surprise, then, that Wal-Mart competes based on cost, in part through the use of technology but also by keeping labor costs as low as possible, while Pantaloon competes at least in part on customer service.

Wipro’s detailed and sophisticated executive development program covered roughly a thousand managers and executives, each of whom were assessed against twelve leadership measures and then compared with the overall scores in the firm. Every leader was placed into one of three performance/potential categories based on those comparative scores: A (top), B (middle), or C (bottom). The top three hundred leaders were then reviewed with the company chairman in a process that extended over five days. From those reviews, the company created a developmental plan for each candidate that included coaching, training, and rotational assignments. The process created a pool of candidates designed to meet anticipated vacancies in the next few years.

On the surface, this might sound no different from what one would see in the largest and oldest U.S. corporations (although precious few companies still do this), but Wipro added another feature that was quite distinctive. It tracked candidates outside the firm, those they would like to attract at some point, keeping up with their development elsewhere and planning for the point where vacancies inside Wipro would create an opportunity to recruit them.

Development programs like these were not limited to entry-level candidates. Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories put all its outside hires, including those with substantial experience, through a one-year training program that included ten weeks of assignments abroad as well as a culminating cross-functional project presented to the top executives.

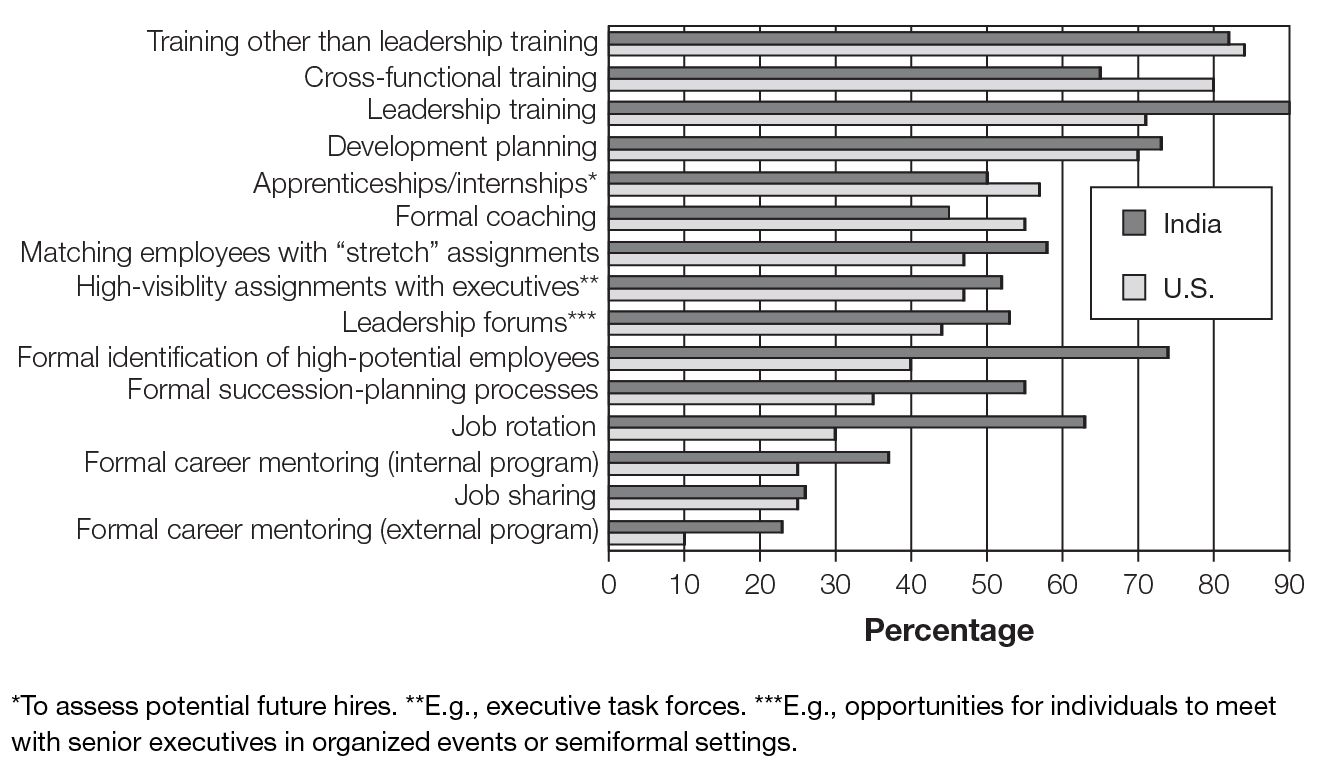

Figure 3-4 reports on the employee development programs of Indian and American companies. While companies in both countries reported reasonably high incidences of various development initiatives, the Indian group in most cases reported more extensive use. This was particularly so for leadership training (90 percent in India versus 71 percent in the United States), identification of high-potential candidates (74 percent in India versus 40 percent in the United States), and job rotational assignments to build cross-functional skills (63 percent in India versus 30 percent in the United States). These were all initiatives that embody significant commitments of executive time and company money—powerful indicators of the priority that Indian companies gave to developing talent from within the company.

Employee development methods

Sources: Survey of Indian companies, and Society for Human Resource Management, SHRM/Catalyst Employee Development Survey Report (McLean, VA: Society for Human Resource Management, 2007).

Further evidence of exactly where the link between employees and strategy plays out came from another survey question that asked about the importance of employee learning—training and development broadly defined—and how it is useful to the business. The results are displayed in figure 3-5.

By far the most important purpose of employee learning in the Indian companies was in building capabilities for the organization—that is, building the basic attributes that the business uses to compete, such as the innovation and customer problem solving at HCL Technologies or the superior customer service experience at Yes Bank. Four in five Indian human resource executives reported that capability building was an important purpose for employee learning, while a meager 4 percent of their American counterparts said the same thing. In fact, capability building ranked next to the bottom on the list of U.S. outcomes, a stunning difference.

How the learning function provides stategic value to the organization

Sources: Survey of Indian companies, and American Society for Training & Development, C-Level Perceptions of the Strategic Value of Learning (Alexandria, VA: American Society for Training & Development, 2006).

In general, the American executives rarely saw learning as serving strategic-level goals for the organization. The outcome that American executives reported most frequently as the purpose of employee learning was to better execute existing strategies: “learning,” in short, really was mostly training, designed to improve performance on existing tasks. Even then it was only embraced by 14 percent of respondents.

The Indian business leaders were aware that building a competitive edge through employee competencies was not guaranteed or an easy thing to pull off. As Deepak Parekh of Housing Development Finance Corporation Ltd. (HDFC) said, “Unless people in organizations are mobilized and energized on a sustained basis in support of business priorities, success can be elusive.” Yet the very difficulty of this central task might explain the generally greater esteem in which the whole area of managing people is held in India. Overall, 65 percent of the Indian HR heads said that their function had the same level of respect in the company as other functional areas like finance and marketing versus only 40 percent in the United States (see figure 3-1). Some of the executives went further. “If you ask me,” said Ravi Uppal of L&T Power, “the CEOs of companies today should be the HR managers.”

Culture and Commitment: We Are Family

When asked about their overall priorities as the top executive, the business leaders we surveyed obviously had a lot of items they could list. It might not be a huge surprise to find that their number one priority was setting strategy, but number two on the list is something of a shock: keeper of organizational culture. And number three is even more surprising: acting as a role model or teacher for the employees.

The number two and three priorities together are efforts to harness the norms and values inside the organization—culture—that shape the attitudes and behaviors of the employees. Especially in the absence of formal rules and direct supervision, culture tells people how they should act and respond to new circumstances, especially when no one is watching. The business leaders saw the need for culture to extend their personal leadership and convey their company strategy far beyond their own individual presence. They viewed culture as a magnetic force that would align even the most remote of their managers’ needles. Many of the business leaders stressed the powerful importance of an organizationwide mindset that valued performance, focused on customers, and identified with the firm’s mission.

Here again, the lack of legacy burdens helped the executives execute this aspect of the India Way. Many of the business leaders whom we interviewed had virtually clean slates on which to write. Bharti Airtel, India’s largest mobile telephone carrier, had been operating for a little more than a decade, and as CEO and joint managing director Manoj Kohli saw it, it was now the critical time to confirm the culture. As “parents we know that when a child is ten, it is the time to build character, build values, build the core values of a child—or of a company.” If “we don’t inculcate deep-rooted values now,” he concluded, “the character of this child will never be built for the long term.”

Role Modeling

Employees learn about organizational culture by seeing what gets rewarded, noting priorities when strategic choices have to be made, and observing how company leaders behave. Managing culture therefore cannot be a staff function; it has to come from the top. And it is impossible to manage the culture of an organization unless the top leaders recognize that they are being watched carefully and are of necessity teaching through example. Psychologists refer to this as role modeling, where individuals consciously or subconsciously copy the behavior of those they look up to. And what makes for an effective role model? Someone who is attractive in having positions of influence, especially power over individuals; someone who seems to have come from a similar set of experiences, such as manager who has advanced in one’s own company.

The business leaders in our study implicitly understood the power of modeling behavior. Why else would they have placed such a high emphasis on being a guide or teacher for employees, ahead even of being a representative of shareholder interests? It is hard to imagine American executives saying that they thought serving as a personal guide or teacher for employees was more important than serving shareholder concerns.

When asked why “keeper of organizational culture” was his number one priority, Azim Premji of Wipro responded, “because any company, which is growing at 30 percent plus, is highly people intensive. In trying to localize more and more to the various geographies, we need a common face with the customer. Maintaining that culture or building that culture is an absolutely key priority of a CEO. He must walk the talk.” In Premji’s view, a strong, common set of values and norms is the glue that keeps employees operating in a consistent fashion, even when the company itself is large and geographically dispersed.

Subodh Bhargava, chairman of Tata Communications, offered a similar account. Amid all the course corrections, even strategic changes, of the last twenty-five years, values and vision, he said, always served as the “first anchor” to keep the company operating in a consistent direction. Proshanto Banerjee, former chairman and managing director of Gas Authority of India Ltd., spoke for many when he said that he had worked hard to ensure that his employees could “see the larger picture in which they were operating, understand the importance of the company that they were working for, and feel strongly about its purpose and develop a certain amount of pride.”

While each company represented a unique blend of cultural facets, virtually every business leader whom we interviewed said culture was rooted in commonly shared values of how the company should operate and the goals for which it should strive, and extended from shop-floor conversation to executive-suite decision making. Among those shared values, two particularly stood out during our interviews with Indian chief executives: a relishing of risk and a fervent customer focus. Narayana Murthy offered a succinct description of the culture he wanted at Infosys: creating an environment where people are tired when they leave work but come back with enthusiasm the next morning.

Culture As Family

The norms and values that form the culture of most of the India Way companies envelop the entire workforce into a sense of family with requisite obligations. In one sense, this is reminiscent of the “organization man” approach common to American corporations in the 1950s, an explicit exchange of loyalty and commitment for job and economic security, but this is not a bartered arrangement to placate unions or other stakeholders.12 It arises instead from a genuine sense of obligation to the employees on the part of the employer.

The executives that we interviewed saw serving their own workers as an important mission for their company. Narayana Murthy of Infosys Technologies spoke for many: “Indian business leaders bring a sense of family, a sense of closeness to the office. In other words, they relate to their people in a much more familiar manner—a much more affectionate and closer way than I have seen” in the United States.

When we asked the Indian business leaders about their personal legacies as leaders, one of the first responses was about transforming their organizations, but a second theme revolved around obligations to employees: empowering them, creating development opportunities, and enriching their lives. B. Muthuraman of Tata Steel put it in simple and straightforward terms: “To make people happy. That’s it!”

The important advantage of this approach is that it creates a sense of reciprocity with the employees: if the executives and the company care about you and look after your interests, you should look after the interests of the company, tapping into the aspects of commitment that create high levels of performance and citizenship by employees. (Think of citizenship as how they behave when no one is monitoring them.) In keeping with this sense of commitment, India’s major companies are much more likely than their American counterparts to offer workers a range of benefits that can evoke a strong sense of paternalism: on-site health-care and wellness programs, for example, plus family days and programs for balancing work and career.

Family As a Double-Edged Sword

As admirable as the culture of family and the emphasis on personal relationships that permeate Indian business life can be, it also creates challenges, especially at the management level. Vice-chairman and managing director K. Ramachandran of Philips Electronics India noted that in Indian businesses, as opposed to Western firms, “relationships play a much larger role than black-and-white, pure objectives.” With a lingering overlay of caste traditions and a concomitant deference to status and authority, the persistence of personal over professional relations sometimes shaded into a deference toward leaders per se.

Gurcharan Das—former chief executive of Procter & Gamble India—argued that some of this focus on keeping business relations within a tight community (traditionally caste, religion, and family) came about during the license raj, when businesspeople always had to break some law in order to adjust and survive under extant government regulations. For that reason, they wanted people around them who could keep secrets, people who were bound to them through other relationships. 13 This predilection to keep business relationships within existing social communities represented a challenge that Indian businesses had to address after the 1991 economic reforms, especially with their need to develop a diverse workforce commensurate with the diversity of their customer base.

The stress on personal relationships creates problems in assessing talent as well. As Subodh Bhargava explained, “One of our biggest weaknesses is that we are unable to reach scientific, reasonable assessments of white-collar productivity. [When] it comes to judging people and their capabilities and expectations, we tend to be poor judges.” Bharti Airtel’s Manoj Kohli added, “Emotionality is still higher than rationality,” among Indian business leaders, “which is bad news because the rationality has to overtake emotionality” for companies to prosper.

Another set of dispositions that had to be overturned with the emerging India Way is the notion that superiors lead and subordinates follow, even when the former are faltering. Subodh Bhargava of Tata Communications noted that “in India we tend to be hierarchical, not just in administrative and management structure hierarchy. We are very conscious of personal hierarchy in our position. In fact, many companies have fallen by the wayside because they couldn’t shed their hierarchical mind-sets.”

Empowering Employees

Creating a sense of commitment through these mutual obligations would be almost cruel if the employees could not act on it for cultural, hierarchal, or other reasons. Perhaps that is why, in the past, empowerment in Indian firms was rare. Gurcharan Das remembered one business leader confessing, “In the past, I was extravagantly wasteful of talent or myopic in believing that I could do it all myself.”14 In recent years, though, the Indian business leaders we studied have worked hard to turn the theory about the advantages of empowering employees into practice. HCL went out of its way to enable individuals to solve customer problems, and Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, India’s second-largest pharmaceutical company, made teamwork one of its five core values, along with a supporting value of respect for individuals regardless of hierarchy.

Jagdish Khattar, formerly of Maruti Udyog (now Maruti Suzuki) offered advice to his fellow business leaders from his own experience with empowerment. “Don’t come with your own fixed views,” he urged. “People within the company: throw issues to them, let them examine and come back to you with solutions. I have done it again and again. Eighty-five percent of their solutions would be what you have in mind, maybe 90 percent,” but let “them go back with the impression that 100 percent of the solution is theirs. The implementation would be quick and smooth. And they will feel very proud of it, but it serves your purpose.”

From “All Minds Meet” to “Single Status”

Empowerment produces not only better ideas but stronger commitment to their execution. The software company MindTree adopted a host of innovative methods for fostering ideas and execution, beginning with an entire menu of ways for the employees to give feedback to executives. Among the arrangements: monthly updates called snapshots that described the competitive environment and the state of the company; “All Minds Meet,” a regular open house with the company’s leadership where all questions were tackled on the spot; the “People Net” intranet, where grievances were addressed; and “Petals,” a blogging site.15 But the most unusual aspect of the MindTree approach, both in transparency and role modeling, could be found in the company’s integrity policy. MindTree posted on its Web site accounts of ethical failures and violations of company policies, and the lessons the firm had learned from each.16 The idea is that by acknowledging mistakes, especially those made by leaders, the company encourages others to admit theirs and to follow its lead in making changes.

The high-water mark for a culture of openness and flat hierarchy probably goes to Sasken Communication Technologies, which Rajiv Mody started in Silicon Valley and moved back to his home in Bangalore in 1991. The company’s “single-status” policy meant that all employees, from entry level to Mody himself, were treated identically—same offices, same travel policies (coach class), same criteria for compensation (no separate executive compensation policies). While the company is known for being cheap in the area of compensation, it is otherwise extremely employee friendly, with policies that provide extensive programs for leaves, including a six-week sabbatical after four years of employment.17

Blowing It Up

In addition to programs of communication and feedback, most of the companies we studied had regular programs to survey and assess employee attitudes. And many openly shared the results with employees. Some went further with arrangements for addressing specific employee complaints and grievances. Tata Consultancy Services, for example, has an online system where employees submit grievances about how they have been mistreated by management.

Comparing the extent to which the Indian and the American companies track initiatives designed to enhance employee engagement provides a useful index of how seriously businesses and their leaders in both nations take the concept. In our surveying, 51 percent of the Indian firms frequently tracked these initiatives, while only 31 percent of the U.S. firms did so.18 Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw of Biocon spoke for many in describing how her company moved empowerment into the team arena: “We have created very focused . . . groups to think strategically. The way you do that is to handpick all these people—and it has to be cross-functional groups—and get them to work in teams. It all sounds like motherhood statements, but getting people to work as cross-functional teams is very important.” The final word on the importance of empowerment comes from Anand Mahindra of Mahindra & Mahindra, who offered this advice to an eventual successor: “If you do not continue to empower people as I have been doing, you are going to blow this thing up.”

Summing Up

Perhaps the main conclusion about the India Way’s approach to managing people is that it is integral to the way the companies compete, to their business strategies. In these companies, strategy is based on internal competencies, which ultimately come from the actions and efforts of employees. The fact that Indian CEOs give so much attention to employee issues, therefore, is not just because they want to be generous to their employees. It is because it drives the competitiveness of their businesses.

The focus on employees can go too far, some argue, especially where that focus gets confused with personal relationships. Vice-chairman and managing director K. Ramachandran of Philips Electronics India warned about the downsides of personal ties in Indian companies. They might dominate professional relations, for example, in dealing with poor-performing family members in promoter-led companies. Tata Communication’s Subodh Bhargava observed, “One of our biggest weaknesses” in India “is that we are unable to reach scientific, reasonable assessments of white-collar productivity.” When it comes to “judging people and their capabilities and expectations, we tend to be poor judges.” Managing director G. R. Gopinath of Deccan Aviation contrasted India and the United States: While “there is a ruthless insensitivity to anything other than financial performance” in the United States, he observed, “the danger in India sometimes is, people are not performance oriented enough. When your personal relationships get sometimes mixed up, you tend to take a soft approach.”

More generally, some worry about the paternalism of Indian firms. Jet Airways’ executive director Saroj K. Datta saw paternalism as a major difference between Indian leaders and their peers in the Western world. The concern about paternalism is that it may mutate into a kind of mutual dependency, with a company remaining loyal to employees and employees to the company in ways that restrict change.

Such concerns come down to taking a good thing too far. At least at present, the India Way companies seem to be striking the right balance in their holistic engagement of employees.