CHAPTER TWELVE

INTRODUCTION

Whereas the professional sports discussed in previous chapters are all about business and the bottom line, at least in a relative sense, a greater sense of pageantry, politics, and global goodwill are associated with global events such as the Olympic Games and the FIFA World Cup. These added elements do not necessarily mesh with the goals of an enterprise striving for black ink.

The Olympic Games serve as a vivid model for the concerns that businesspeople have in bidding for global events, whether it be soccer, rugby, gymnastics or any other event with participants from around the globe. The entity in the Olympic alphabet stew that has the clearest charge to reach for financial success is the organizations for a given Olympiad. An equivalent body exists for any major global sporting event. These entities are the on-the-ground enterprises that must actually make the event happen and have financial success.

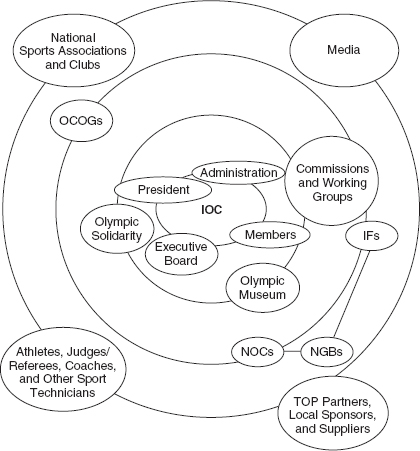

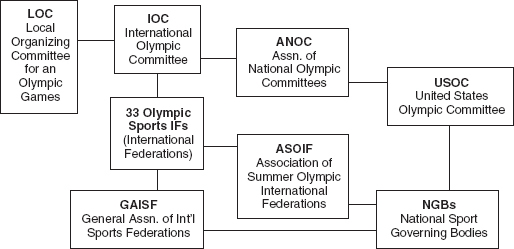

The Organizing Committee for the Olympic Games (OCOG) will be the primary focus of this chapter. However, before that focus, this introduction will describe the positioning of the various organizations in the overall Olympic world. The business of the Olympics is a combination of organizations, referred to in the industry by their abbreviations. This is the same with regard to global events for individual sports as well; for example, FIFA holds the power regarding global football. The various bodies wield a certain degree of power, and all must, sometimes with difficulty, work together to stage the Olympics in both their winter and summer forms. Figures 1 and 2 depict the organizational structure of the Olympics.

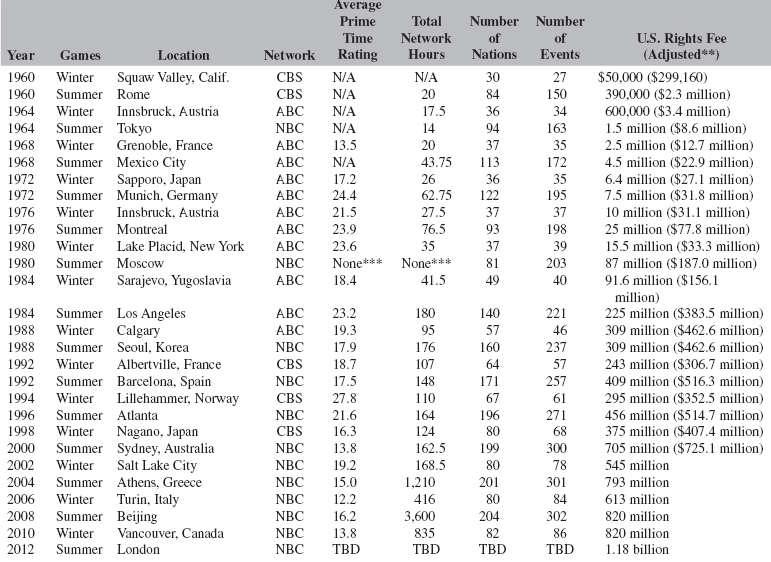

The rights to the Olympic Games and all of the intellectual property associated with them—including the five rings, their colors, the flag, and the words Olympics, Olympiad, and Olympic Games—are held by the International Olympic Committee (IOC), which is based in Lausanne, Switzerland. The primary sources of revenue for the IOC are broadcast rights, sponsorships, ticket sales, and licensing-related revenues. The financial driver for the Olympics, just as with professional sports, is television (see Table 1). The numbers are truly staggering in this arena. The sale of worldwide broadcast rights from 2005 to 2008 provided the IOC with $2.568 billion—over half of its total revenues. The IOC relies heavily on the United States broadcast networks, with nearly 60% of these revenues coming from NBC, 23% from Europe, and the remainder from the rest of the world. This situation is unlikely to change in the near future, with NBC paying $2.201 billion for U.S. broadcast rights for the Olympic Games of 2010 in Vancouver and 2012 in London. The IOC distributes 51% of the broadcast rights fees of each Olympics to the OCOG responsible for the respective Olympic Games and 49% to the Olympic Movement. A broader discussion of television and the business of sports appears in Chapter 8.

Sponsorships established by the IOC sponsorship program, formally called The Olympic Program (TOP), are a vital source of revenue for the IOC, accounting for 34% of its revenues from 2005 to 2008. Composed of 12 global companies that receive broad category exclusivity, the TOP program generated $1.866 billion during the past quadrennial, from 2005 to 2008. Although less so than in the past, the IOC is heavily dependent on the United States for its sponsorships, with six TOP sponsors based in this country. (From 2009 to 2012, the TOP program will be composed of nine global sponsors, four of which are from the United States.) Ticket sales to Olympic opening and closing ceremonies and events provided $238.5 million for the IOC, or 11% of its revenues. The sale of Olympic-related licensed products, coins, and stamps completes the IOC financial picture, generating $122 million (or 2%) of the organization’s revenues.

The IOC distributes over 90% of its revenues to OCOGs, National Olympic Committees (NOCs) and International Federations (IFs). For example, the Turin Organizing Committee (TOROC) received $406 million in broadcast rights and $139 million from the TOP program. This $545 million represented 35% of TOROC’s operating budget. The IOC provided the Athens Organizing Committee (ATHOC) with $960 million, or 60% of its operating budget, for the 2004 Games. In addition, the IOC distributed a combined $4.41 billion to the Turin Organizing Committee, the Beijing Organizing Committee, the NOCs that sent teams to the 2006 and 2008 Olympic Games, the 28 summer sport IFs for the 2008 Olympics, and the 7 winter sports IFs for the 2006 Olympic Games. The IOC retains 8% of its revenues to pay its administrative and operating expenses.

Figure 1 Structure of the Olympic Movement

Source: International Olympic Committee. Used with permission.

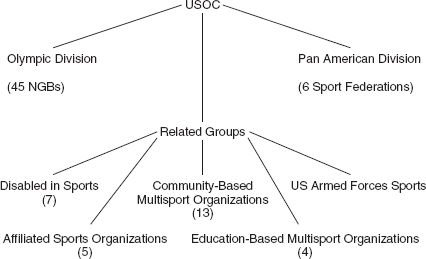

Each of the 205 countries that are a part of the Olympic family has its own NOC. A country’s NOC is responsible for fielding its Olympic team. The United States Olympic Committee (USOC) shoulders this responsibility in the United States. Figure 3 depicts the organization of the U.S. Olympic Movement. Empowered by the Amateur Sports Act, the USOC derives much of its revenue from the IOC. The USOC receives royalty payments from the IOC and broadcast networks for the U.S. Olympic broadcast rights; 12.75% of the IOC’s American broadcast revenues ultimately are delivered to the USOC as part of a 21-year-old deal with NBC, providing the USOC with $673 million for the Olympic Games from 2000 to 2012. This bounty is not limited to television. The USOC also receives 20% of the IOC’s global marketing revenues—more than all of the other 204 NOCs combined. The USOC also generates significant revenues from its own domestic sponsorships, joint ventures, and fundraising and licensing efforts. In 2008, the USOC generated $280.6 million in total revenue.

Figure 2 International Sports Organizational Relationships*

Source: United States Olympic Committee. Used with permission.

Table 1 The Games on TV: Network Ratings, Rights Fees, and Related Information Since the Olympics Were First Televised

*Total hours listed for the Winter Olympics from 1960 to 1984 are for prime time only.

**Fee converted to 2001 value using U.S. Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics formula. Figure represents 2001 buying power.

***The United States boycotted the 1980 Summer Games; NBC’s coverage was limited to highlights and two anthology-style specials after the Games were completed, though the network still paid the full rights fee.

Sources: Guardian, NBC, Nielsen Media Research, Street & Smith’s Sports Business Journal research.

Note: For the 2008 Summer Games in Beijing, an additional 2,200 hours of live coverage were aired on NBCOlympics.com.

NA: Not available; no television ratings system was in place at the time.

TBD: To be determined.

Despite its nonprofit status, the USOC has struggled to avoid red ink in recent years. The USOC has a staggering amount of overhead expenses and also provides American athletes and various National Governing Bodies (NGBs) with over $70 million of financial support each year. However, it should be noted that, unlike almost every other country’s NOC, the USOC does not receive any direct government support. The fact that the IOC and USOC are so mutually dependent is thought to have generated significant resentment of the United States in the European-controlled IOC.

Figure 3 Organization of the U.S. Olympic Movement*

Source: United States Olympic Committee. Used with permission.

The next layer of governance is among the individual sports. This is where entities like FIFA come into play. Each sport is governed at its highest level by an international sports federation. Many host championships or tournaments, such as the FIFA World Cup, that are independent of the Olympic Games. There are 26 IFs involved in the 2012 Summer Olympics and 7 in the Winter Olympics. For example, the International Amateur Athletics Federation governs “athletics,” popularly referred to as track and field. This organization sets the rules and holds the rights to various championships and other competitions around the globe. Each country that has athletes involved in that sport at the international level has a domestic national governing body. In the United States, the NGB for athletics is USA Track & Field (USATF). Overall, there are 45 recognized Olympic NGBs in the United States.

All of these various enterprises are permanent and often extremely political. The perks for leadership within these organizations include global travel, gifts, and important political and business relationships.

The OCOGs are the most unique of the Olympic-related organizations. In the United States, the OCOGs that people are most familiar with are the Los Angeles Olympic Organizing Committee (LAOOC), which planned and operated the 1984 Olympics, and the more recent OCOGs for Atlanta in 1996 (ACOG) and Salt Lake City in 2002 (SLOC). The uniqueness of the OCOGs comes primarily from the fact that they are disbanded once the games are completed. The OCOGs are heavily dependent on the IOC, which provides the OCOG with revenues from its broadcasting and sponsorship rights. An OCOG generates its own revenues through the sale of local sponsorships, tickets, and licensed products. For example, SLOC earned $575 million in sponsorship revenues, $180 million in ticket sales, and an additional $25 million in sales of licensed products. The OCOG retains 95% of its local sponsorship, ticketing, and licensing revenues and gives 5% to the IOC.

A number of other chapters are of interest in conjunction with the readings on the Olympics and other global sporting events. Certainly the chapter on ethics (Chapter 20) has relevance, given the number of scandals associated with global sporting events. With regards to the Olympics, those issues range from the votes of judges to the influencing of IOC members in their site selections for the Olympic Games. The chapter on amateurism (Chapter 18) highlights the thinking behind the creation of a class of athletes characterized as “amateur.” Ironically, although the concept is most often associated with the Olympic Games, there are essentially no longer any “pure” amateurs participating. Many, including members of the U.S. Olympic basketball squads, are professionals in their sports. Many others receive payment from their countries, with the highest rewards given for gold medals or the breaking of world records.

In the first reading, “Management of the Olympic Games: The Lessons of Sydney,” Chappelet focuses on the key management elements of running an Olympics: time, money, human resources, and information. In the second selection, “The Financing and Economic Impact of the Olympic Games,” Brad Humphreys and Andrew Zimbalist focus on the economic aspects of the Games. The final article, Giannoulakis and Stotlar’s “Olympic Sponsorship: Evolution, Challenges and Impact on the Olympic Movement,” offers more depth on the financing issue, addressing Olympic sponsorships.

ORGANIZING COMMITTEE MANAGEMENT

MANAGEMENT OF THE OLYMPIC GAMES: THE LESSONS OF SYDNEY

Jean-Loup Chappelet

… We shall define management as the optimization of the resources available to managers. These resources can be divided into four main categories: time, money, human resources, and information. The main features of the management of each of these resources for the Sydney Games will be examined below. Comments will then be made on the organizational structures put in place to manage these resources.

TIME

Time is the rarest resource of any major event-type project as, by definition, such an event cannot be postponed, even by a single day. The Games of the new millennium were scheduled to open on 15 September 2000, and this date had been virtually carved in stone over six years earlier. For an OCOG, every additional day is a day less… In this respect it is important to note that SOCOG [Sydney Organizing Committee for the Olympic Games] was very quickly set up by virtue of a law enacted by the Parliament of New South Wales on 12 November 1993, less than two months after the IOC’s decision to award the Games to Australia’s biggest city. A new record for diligence had been set!

One and a half years later the OCA (Olympic Coordination Authority) was created, with the principal task of building most of the sports facilities that were required, including the Olympic Park in Homebush, which would host fifteen of the twenty-eight sports on the program. All of the sports venues for the Sydney Games were thus ready around one year before the Games, except for the temporary beach volleyball stadium on Bondi Beach. This meant that test events could be organized well in advance, and provided the opportunity to correct in situ all manner of unanticipated organizational problems.

These dress rehearsals undoubtedly contributed to the success of the sports management of the Games. They did away with the need for last-minute fixes, which are a source of stress and additional expense. In Atlanta, the Olympic stadium was opened just three months before the Games, and work began on fitting out the Main Press Centre just three days before the Games opened. The contrast is striking: The time spent on preparation in Sydney in a sense resulted in time saved during the Games. The daily coordination meetings with the IOC each morning became progressively shorter. One was even canceled.

MONEY

Although it is still too early to draw any definitive conclusions, initial figures suggest that SOCOG’s budget will balance at around A$ 2.5 billion. (In September 2000, the exchange rates were approximately A$ 1 = CHF 0.97, US$ 0.56.) This certainly owes something to the limitations placed on operating expenditure, but also and above all to the optimization of the Games revenues themselves.

After the disappointment—an understatement—that greeted the announcement of the total figure negotiated by the IOC for television rights to the Games in the United States (which were sold to NBC rather than Fox Network), SOCOG turned to other possible sources of revenue, mainly sponsoring and the sale of tickets for the competitions.

Nearly A$ 700 million were obtained from the 24 Team Millennium sponsors (including the 11 partners of the IOC’s TOP program), the 19 Sydney 2000 Supporters, and the 60 official providers (including 23 sports equipment companies).

To this sum was added some A$ 70 million in royalties from the three thousand or so products manufactured with SOCOG’s emblems by around a hundred licensed businesses. This licensing program remained within the bounds of good taste and was a considerable success. Even during the Games, long queues formed outside various “Olympic Stores” set up specially to sell these products.

A total of A$ 770 million in revenue was therefore attributable to commercialization in the strict sense of the word, compared with the A$ 1,039 million SOCOG received for the television rights. This represents approximately A$ 40 for each inhabitant of Australia, or thirteen times more than the commercial revenue from Atlanta, in terms of population. As far as tickets were concerned, SOCOG beat the sales records set by previous OCOGs despite the major difficulties caused by a multi-tiered distribution program that proved to be needlessly complicated. While over two million tickets remained unsold three months out from the Games, an average of 50,000 tickets were sold each day during the Games. For the first time in Olympic history, SOCOG’s Internet site was also made to pay its way, through sales of tickets as well as licensed merchandise. The sight of the 110,000-seat Olympic stadium being filled almost to capacity during the athletics heats was particularly impressive. Approximately 87% of the Olympic tickets were finally sold, almost meeting the budgetary objective of A$ 566 million. The tickets for the cultural program also sold well.

The success of the commercial program, built up over the years of preparation and boosted towards the end by the ticketing program, enabled SOCOG to avoid digging too deeply into the A$ 140 million reserve allocated in June 2000 by the government of New South Wales to enable SOCOG to balance its budget. This reserve also undoubtedly had a psychological effect. It helped to avoid a situation in the final months where SOCOG had to base its operational decisions solely on financial criteria, as was the case in Atlanta in 1996. We now know that, in order to avoid the slightest hint of a deficit, the organizers of the Centennial Games economized as much as possible during the final year leading up to the Games, to the point of jeopardizing the transport and information systems.

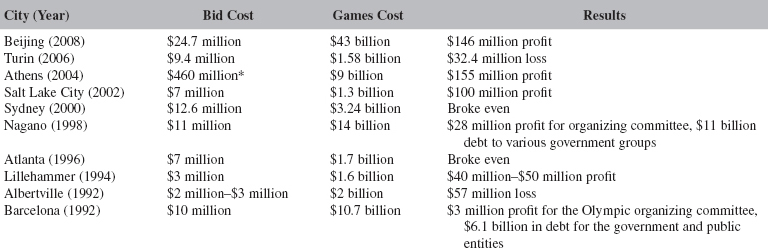

The icing on the cake in terms of optimizing financial resources came when SOCOG had the good fortune of seeing the Australian dollar decline sharply against the U.S. dollar as the Games approached, contrary to the historical tendency of host country currencies to appreciate during the Olympic year. Although the television rights negotiated in U.S. dollars had been prudently hedged against exchange rate fluctuations, this stroke of luck nevertheless provided additional revenues of the order of A$ 50 million. [Ed. Note: Table 2 shows the cost of the Sydney Olympic Games and others.]

HUMAN RESOURCES

Preparations for the Games require putting in place an organization that in six years grows from a handful of personnel to several thousand (2,500 in Sydney), only to drop one month after the Closing Ceremony to a few hundred staff, who virtually all disappear in the year following the Games. During the Olympic period, the core staff is augmented by an army of volunteers (47,000 in Sydney). It is not difficult to imagine the enormous challenge of managing the human resources of such a business, which has virtually no past, and no future at all as soon as the Games are over.

SOCOG encountered major difficulties in this area. It went through two presidents before the appointment, after the Atlanta Games, of Michael Knight, who was already the Olympics Minister for New South Wales. The controversial management style of the last president led over the years to the voluntary and involuntary departure of several staff members, including one chief executive. Evidently, however, SOCOG’s second chief executive, Sandy Hollway, was able to maintain the motivation of the majority of his troops right up to the end. This was to the detriment of his relationship with the president, who withdrew a large part of his prerogatives one month before the Games and sought to limit public recognition of the man he had appointed as his “number two.”

In contrast, the volunteer program was perfectly conducted, and most certainly contributed to the success of the Games. Word quickly spread among the Olympic family, the media, and the spectators about the spontaneous friendliness of the thousands of young and less young Australians (and foreign nationals) who had volunteered their services. The volunteers were the shop window of the Games, and the main point of contact between the organization and its “clients.”

Planning began almost three years before the Opening Ceremony (compared with 18 months before in Atlanta), and volunteers were recruited through a national campaign in October 1998. A complete training program was set up by the public training agency TAFE NSW, based on manuals, videos, and an Internet site. The program began in June 2000 and enabled Sydney’s volunteers to fill the majority of posts during the Games, unlike in Atlanta, where the volunteers had often not been trained for the tasks they were performing. Some of the drivers even used their own leisure time to familiarize themselves with the Olympic routes. The volunteer leaders, often volunteers themselves, were also given leadership courses.

Table 2 Olympic Costs

Sources:Street & Smith’s Sports Business Journal research, International Olympic Committee, USA Today, Associated Press, Snow Country Magazine, China Daily, Los Angeles Times, Turin Olympic Committee, Sports Business News, BBC, CNN.

*Note: $460 million represents the alleged amount misappropriated for the Athens Olympic bid.

The low drop-out rate for volunteers during the Games, far lower than in Atlanta, is an indication that this fundamental human resource was well managed. Although it was not announced in advance, most of the volunteers were compensated with tickets for sports competitions or rehearsals for the Opening Ceremony. Five thousand of them were also able to attend the Closing Ceremony free of charge. They also had free use of public transport. One of Sydney’s daily newspapers even published all of their names, from Naseem Aadil to Warren Zylstra, in a special section entitled: “47,000 heroes.”

INFORMATION

Information is still all too seldom identified as a managerial resource on a par with human and financial resources. And yet it is a vital resource in today’s post-industrial society, which is a service society whose main raw material is information. It is such information, in the broad sense, which the media broadcast during the Games in the form of text, images, and sound, and, which, after the Games, constitutes the only tangible trace of the Games apart from the Olympic facilities.

Information management proved particularly disastrous at the beginning of the Centennial Games: the results sent out to the Olympic Family and the media by the information system were full of errors, which meant that the press agencies were obliged to re-enter them manually for transmission around the world. Unsatisfactory transport and accommodation conditions for the journalists only increased their recriminations which, in a few short days, irretrievably damaged the reputation of Atlanta and its Games. Rightly or wrongly, IBM was held responsible. Not wishing to see a repeat of the fiasco, IBM proposed to SOCOG that it would take charge of systems integration, a role that had been filled in Atlanta by the OCOG itself.

The information system for the Sydney Games comprised four sub-systems: 1) for generating the competition results; 2) for broadcasting information on the Games to the Internet; 3) for communication within the Olympic Family through two thousand “INFO” terminals; 4) for management of SOCOG services (accreditation, accommodation, ticketing, transport, recruitment, etc.). These systems included some systems provided by other technology partners, such as Xerox for data printouts, Swatch Timing for competition timekeeping, Kodak for 200,000 accreditation photographs, and Panasonic for broadcasting text and images on giant screens. Overall, the information system for SOCOG and the Games was implemented through the efforts of 850 experts, and was accessed by nearly seven thousand networked personal computers.

We should not omit to mention the great success of the official Sydney 2000 website, managed for SOCOG by IBM (www.olympics.com). The site welcomed some 8.7 million visitors from the day before the opening until the Closing Ceremony of the Games, most of them from the United States (38%), Australia (17%), Canada (7%), Great Britain (5%), Japan (3%), and 136 further countries. These visitors—the great majority of them women—spent an average of 17 minutes on the site, and downloaded a total of 230 million pageviews. Fans from 199 countries sent 371,654 emails to the participating athletes, over four thousand of whom created a personal page on the computers available in the Olympic Village.

The site of the TV network NBC (www.nbcolympics.com), the only site, along with Australia’s Channel 7, authorized to webcast short video sequences of the Games, attracted 2.2 million Americans during the Olympic fortnight. In comparison, 59 million people saw NBC’s recorded coverage of the competitions. (Television viewing figures were lower than usual because of the time difference.) These statistics are particularly impressive considering that the first Internet browser became available the same year that the Games were awarded to Sydney. Thanks to the Internet, results, sound, still and moving images of the Olympic festival undoubtedly constitute a mine of new rights to be exploited by the IOC and the OCOGs, while respecting the public’s right to information.

This very brief overview of information management by SOCOG would not be complete without a mention of the TOK program (Transfer of Olympic Knowledge), which was launched one year before the Games to synthesize the bulk of information essential to their organization. This work, in the form of around 100 manuals drafted during the year 2000 by SOCOG’s managers, was financed by the IOC, and will be used by the OCOGs of Athens and Turin before being updated and passed on to future OCOGs. These TOK manuals will provide a useful supplement to the official report of the Sydney Games, work on which was begun very intelligently well in advance. For the first time, all of the organizational information, all of the tacit knowledge of a complete edition of the Games, will be turned into formalized knowledge for the following Games, in line with the new theories of knowledge management.

ORGANIZATION

This overview of the management of the Sydney Games would not be complete without a brief comment on their structural organization, that is, the political and administrative arrangement of the various bodies involved in organizing the Games. In addition to SOCOG, these were mainly: the OCA (Olympic Coordination Authority), responsible for building most of the sports facilities since 1995; SOBO (Sydney Olympic Broadcast Organization), founded in 1996 and responsible for producing the sound and image signal for the Games (host broadcaster); ORTA (Olympic Roads & Transport Authority), created in 1997; and the OSCC (Olympic Security Command Center), set up in 1998.

Like SOCOG, the OCA, ORTA, and OSCC were agencies belonging to the state of New South Wales. SOBO was officially a commission of SOCOG’s board of directors. Apart from the OSCC, which was chaired by the state police commissioner, all of these bodies were chaired by Michael Knight, who was also New South Wales Minister for the Olympics and president of the DHA (Darling Harbour Authority), which manages the area where six of the Olympic sports were held.

The Sydney Games thus benefited from a highly decentralized structure, unlike that of Atlanta. Every organization mentioned above was responsible for one of the essential organizational tasks: general operations (SOCOG), construction and management of the facilities (OCA), production of televised images of the Games (SOBO), road and rail transport (ORTA), and public security (OSCC). It is perhaps surprising to see how, over the years of preparation, SOCOG was little by little divested of major responsibilities. Although for operational reasons the minister/president felt the need, a few months before the Games, to bring together the various bodies he chaired under a single central decision-making structure called “Sydney 2000,” it is highly likely that their original autonomy—which guaranteed that they were completely focused on their mission—contributed greatly to the ultimate success of the Games.

Moreover, one can see to what extent the organizing of the Games in Sydney was state-controlled, from both a legal point of view and a personnel point of view, since the main leaders were senior government officials and civil servants. This is particularly striking as the Atlanta OCOG was entirely private (though a non-profit organization). The lack of coordination with the authorities of the state capital and the state of Georgia contributed to the various problems, particularly in terms of sponsorship, traffic, and security. These problems were naturally resolved in Sydney thanks to the active participation of elected government officials and the local and regional administrations concerned, which ended up spending over A$ 2 billion on the Games, over and above SOCOG’s budget. Added to this was the coordinated contribution of some thirty agencies of the Australian Federal Government, estimated at A$ 484 million, including, for the record, the first “official poet” of the Games since Pindar.

Is Sydney’s managerial model preferable to that of Atlanta? Yes, probably, because the Games have become an event that affects an entire country. Whatever their legal status, the OCOGs have to work very closely with the public authorities, with whom they have to share their goals of public service, and the harmonious development of the managerial objective should no longer be to stage bigger Games, because “gigantism” is an ever-present threat, but to stage Games that are unique and special, that leave a lasting mark in the collective history of the nation and the human race.

ORGANIZING COMMITTEE REVENUE SOURCES

THE FINANCING AND ECONOMIC IMPACT OF THE OLYMPIC GAMES

Brad R. Humphreys and Andrew Zimbalist

![]()

Table 3 Olympic Movement Revenue (in Millions)

![]()

Source: Adapted from IOC, 2006 Olympic Marketing Fact File, http://www.olympic.org, p. 16. Reproduced with permission of ABC-CLIO, LLC.

![]()

Table 4 Past Broadcast Revenue (in Millions)

![]()

Source: Adapted from IOC, 2006 Marketing Fact File, p. 46. Reproduced with permission of ABC-CLIO, LLC.

![]()

Table 5 Ticket Sales and Revenues (1,000,000s of Tickets and Current US$)

![]()

NB: Ninety-five percent of ticketing revenue stays with the local OCOG; 5 percent goes to the IOC.

![]()

![]()

Table 6 Estimated Economic Impacts and Visitors from Promotional Studies

![]()

Source: Compiled from various media sources, authors’ calculations. Reproduced with permission of ABC-CLIO, LLC. [Ed. Note: Total Estimated Impact was not calculated for Tokyo, Munich, Montreal, Moscow, Calgary, Albertville, or Lillehammer.]

![]()

EVOLUTION OF OLYMPIC SPONSORSHIP AND ITS IMPACT ON THE OLYMPIC MOVEMENT

Chrysostomos Giannoulakis and David Stotlar

Over the past Olympiads, the International Olympic Committee (IOC), Olympic Organizing Committees (OCOGs), National Olympic Committees (NOCs), and in general the Olympic Movement have become increasingly dependent upon the significant financial support provided by corporate sponsors. The increased dependency of the Olympic Movement on corporate sponsorship is seen in the fact that 30% of the IOC’s budget and 40% of the United States Olympic Committee’s (USOC) funds are derived from sponsorship and licensing income.1 Olympic sponsorship involves not only financial support of the revenue, but provides products and services, technologies, expertise, and personnel to help in the organization of the Games.2 Sponsorship revenue for the 2002 Salt Lake Winter Olympic Games accounted for 54% of all income.3 In addition, the Athens 2004 sponsorship program, with the combined support from domestic sponsors and The Olympic Partners (TOP), was the second largest source of revenue for the staging of the Olympic Games, providing approximately 23% of the Organizing Committee’s budget. As a result, in Greece, a nation of fewer than 11 million people, Athens 2004 sponsorship provided the highest-ever capital support of any domestic program in the history of the Olympic Games.4 The abovementioned figures illustrate clearly the significant financial contribution of corporate sponsorship to the viability of the Olympic Movement and the continuation of the Olympic Games. The aim of this paper is to present financial data on the mutual beneficial relationship between the Olympic Movement and corporate sponsorship, as well as to discuss factors that may influence the nature of the Olympic Games due to their increased dependency on corporate sponsors. This discussion is conducted within the context of the IOC’s marketing framework and the growing literature devoted to Olympic sponsorship. Marketing strategies of Olympic sponsors at the 2006 Torino and 2008 Beijing Olympic Games will be also discussed. Of particular concern is the way sponsors have attempted to capitalize on the elements of the Olympic Movement and what precautionary measures the IOC has implemented to maintain the spirit and true value of the Olympic Games intact.

HISTORY OF OLYMPIC SPONSORSHIP

The Olympic Games and sponsorship have had a long relationship, which was initiated with the ancient Olympic Games. Starting as an ancient Greek religious festival, where athletes competed in honor of Zeus, the Olympics have become one of the most celebrated and profitable media events in the world. In ancient Greece, cities would sponsor participant athletes by providing athletic facilities, equipment, and trainers. Although winners were only awarded a crown of wild olive leaves, they and their sponsor towns won huge renown.5 At the first modern Olympic Games, which were revived in Athens in 1896 as athletic Games, two thirds of the funds came from private donations. Interestingly, the largest expense of the Games, the refurbishment of the Panathinaiko Stadium, was fulfilled due to the financial contribution of a single benefactor. However, “revenue was also received from private companies, including Kodak, which bought advertising in a souvenir program.”6 It was not until the Stockholm Olympic Games in 1912 that companies would purchase official rights from the International Olympic Committee, such as rights to secure pictures and sell memorabilia. At the Amsterdam Games in 1928 the Organizing Committee granted the right for concessions to operate restaurants within the Olympic stadium, and precautionary measures were implemented to restrict program advertising and to ban advertising in and around the stadium.7

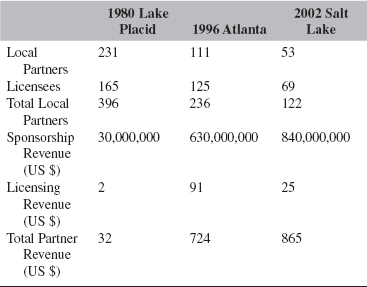

The first financial surplus for an Olympic Organizing Committee was achieved at the 1932 Los Angeles Olympic Games…. Interestingly, the number of sponsors continued to grow in the following Olympiads, with 46 companies participating at the 1960 Rome Games and 250 companies at the 1964 Olympic Games in Tokyo. The participating number of corporate sponsors reached its highest peak at the 1976 Montreal Olympic Games with 628 sponsors and suppliers. Despite the extended number of corporate sponsors, the Games were a financial disaster for the Organizing Committee and the city of Montréal. The 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games were the signature Games in regards to a financial surplus and commercialization of the Games, as they marked a turning point in Olympic sponsorship. The first privately financed Games produced a surplus of $232.5 million in Los Angeles and introduced the concept of protecting the local population from cost overruns associated with a sporting event.9 The marketing program included 34 sponsors, 64 suppliers, and 65 licensees and sponsor hospitality centers were introduced for the first time.10 Through its marketing program the Organizing Committee provided the opportunity for corporate sponsors to strongly affiliate themselves with the Olympic Movement in a number of different ways….

THE OLYMPIC PARTNERS (TOP)

Since the unexpected financial success of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) realized that corporate sponsors provided the Olympic Movement with substantial profits and sponsorship became an integral part of the Movement. Simultaneously, the interconnection and interdependence between Olympic Games and sponsorship was strongly enhanced.12

The financial success of the Los Angeles Games was accompanied by major issues concerning over-commercialization and ambush marketing. One of the most important ambush marketing matters arose when Kodak ambushed Fuji film. Although Fuji was the official sponsor of the 1984 Games, many people were convinced that it was Kodak that was the official sponsor. Kodak was able to secure maximum media and on-site exposure by obtaining sponsorships with the United States Olympic Committee and buying numerous television advertisements during the Olympic Games. By utilizing this effective promotional strategy Kodak successfully created the perception that the company was the official sponsor of the Games.13

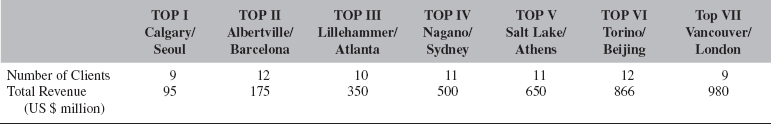

Due to the over-commercialization and the extended ambush or “parasite” marketing at the 1984 Los Angeles Games, the IOC introduced The Olympic Program (TOP) in 1985. Namely, the IOC established a marketing initiative “whereby a limited number of sponsors would receive special treatment and benefits on a worldwide basis while achieving product category exclusivity and protection for their Olympic sponsorship activities.”14 The original name of the program was changed to The Olympic Partners (TOP) in 1995…. [T]he change of the name reflected the nature of the relationship desired by the IOC between itself and the small number of multinational companies who are partners.15 Sponsorship has been defined as a business relationship between a provider of funds, resources or services, and an event or organization that offers in return some rights and an association that may be used for commercial advantage.16 Therefore, the IOC attempted through the TOP program to secure a stable and controlled revenue base, in order to maintain a successful and healthy relationship with its major corporate sponsors. In addition, the TOP program was one of the steps towards the implementation of a modernized funding process of the Olympic Movement. With the initiation of the TOP program, there was a dramatic increase in revenue throughout the five quadrenniums (Table 7).

The TOP program is the only sport-related marketing program in the world that provides complete category exclusivity worldwide while encompassing sponsorship of the event, the organizing body, and all participating teams.17 By initiating the product exclusivity for its partners the IOC was able to significantly reduce the overall number of sponsors by implementing quality over quantity of sponsors while increasing the revenues for the Olympic Movement (Table 8). A reduction in the number of corporate sponsors was considered as the one of the most important mechanisms for the IOC to restrict ambush marketing and to control the commercial aspects of the Olympic Games. The current TOP VI partners contributed an average of $80 million each in order to secure their four year exclusive rights to two Olympic Games, both winter and summer, as well as rights to sponsor Organizing Committees and all participating National Olympic Committees.

Table 7 Evolution of TOP Olympic Sponsors

Source: IOC, 2006 Marketing Fact File (Lausanne: IOC, 2006). Reproduced from Eighth International Symposium for Olympic Research. Used with permission.

… the IOC stated in the 2002 Marketing Report:

The Olympic Family strives to ensure and enhance the value of Olympic sponsorship by diligently managing the partnership program, protecting the Olympic image and the rights of Olympic partners, and recognizing and communicating to a global audience the vital support that Olympic sponsors provide to the Movement, the Games, the athletes. Olympic partners have become fully integrated into the Olympic Movement, creating innovative programs that help to achieve corporate business objectives while supporting the Olympic Games and the Olympic athletes.18

[Ed. Note: Discussion of corporate sponsor contributions at 2002 Salt Lake City and 2004 Athens Olympic Games omitted.]

….

OLYMPIC SPONSORSHIP AT THE 2006 TORINO AND 2008 BEIJING OLYMPIC GAMES

Current estimates of spending by TOP VI sponsors (Torino & Beijing) are $866 million with approximately 33% going to the Beijing Organizing Committee for the Olympic Games (BOCOG) and 17% to the Torino Organizing Committee (TOROC).26 The sponsorship approach of major corporations at the Winter Olympic Games in Italy seemed to vary based on the formidable challenges the 2006 Games presented. The first challenge was the time zones and delayed TV coverage to the United States market. Consequently, the United States TV ratings for the 2006 Torino Winter Olympic Games were the lowest in 20 years. With the continuing dynamics in media preference many Olympic faithful chose to access the Olympic coverage through alternative media. The 2006 Torino Opening Ceremonies attracted 244,575 visitors to the web site. This figure represented a 95% increase over the 2004 Summer Games in Athens. A record number of daily hits to the 2006 Olympic web site occurred on February 16th with over 50 million page views.27 While this falls short of the projected TV audience of 2 billion, the trend may signal a change for Olympic sponsors to extend their placement to additional sites.

Table 8 Sponsorship Presence at US Olympic Games

Source: IOC, Marketing Matters, 2/1 (June 2002). Reproduced from Eighth International Symposium for Olympic Research. Used with permission.

During previous Olympic Games TV coverage produced superstars for a lifetime, yet with the fragmented media access points the Olympians of today may well prove to be very short-term stars. The Games have also encountered increasingly negative publicity as evidenced by various doping scandals among Olympic athletes. Specifically, during the 2006 Winter Games, the Austrian cross-country coach was suspended and an out-of-competition testing done on the Austrian team where blood-doping paraphernalia was found in the team residence at the Games. The much-touted US skier Bode Miller, who commented at a press conference that he skied better when he was intoxicated, subsequently failed to win a single Olympic medal. As a result, many Olympic sponsors prefer to focus their marketing dollars on the platforms created by the IOC and Games Organizing Committees instead of forming alliances with individual Olympic athletes.

As fees for Olympic sponsors continue to rise dramatically, namely $80 to $100 million for a four-year sponsorship agreement with the IOC, corporations are becoming even more strategic in how they market their brands through the Olympics in first place. By integrating Olympic sponsorships into their global marketing strategy, corporations are able to ensure greater benefit from their investment.

….

IMPACT OF OLYMPIC SPONSORSHIP

It is evident that protecting the Olympic image and the value of sponsorship for the Olympic partners are major concerns for the International Olympic Committee. As a result, the IOC’s marketing department has introduced a series of public relations campaigns with the main focus on raising awareness regarding the significant contribution of corporate sponsorship to the Olympic Movement. In addition to the public relations campaigns, the IOC has undertaken several market research studies in order to strengthen and promote the Olympic image and to understand attitudes and opinions towards the relationship between Olympic Games and corporate sponsorship. In the Barcelona 1992 Olympic Games, 79% of people in the United States, England, and Spain stated that the Olympic Games would not be viable without sponsorship. Furthermore, 86% stated that they were in favor of the Games being sponsored. Similar studies in 1996 found that one third of the respondents in a nine-country study suggested that their opinion of the sponsoring company was raised as a result of their Olympic sponsorship.39 In Sydney 2000, 34% of the spectators stated “sponsorship makes a valuable contribution to the Olympics and makes me feel proud about sponsors.”40

In the recent Winter Olympic Games in 2002, the IOC commissioned Sport Marketing Surveys (SMS) to conduct market research on-site with spectators, corporate guest, and media. According to the results of the study, “research results clearly illustrate that unprompted awareness of the Olympic sponsors was very high among Olympic spectators and media, and that all possessed a strong understanding of the importance of sponsorship to the Olympic Movement and the staging of the Games.”41 The results showed that 92% of the spectators agreed that “sponsors contribute greatly to the success of the Games,” 76% of the media agreed that they “welcome sponsorship support if the Games continue to be staged,” and 45% of spectators stated that they would be more likely to buy a company’s product or service as a result of them being an Olympic sponsor. Similar research studies in Athens 2004 Olympic Games depicted the positive attitude of spectators and media towards the support of corporate sponsorship to the Olympic Movement. In Sydney 2000, 34% of the spectators indicated “Sponsorship makes a valuable contribution to the Olympics and makes me feel proud about sponsors.”42

In 2000, the International Olympic Committee conducted a research study in collaboration with a major Olympic sponsor and the Australian Tourist Commission (ATC). The IOC evaluated the attitudes of guests towards the Olympic brand. The sponsor evaluated the level of satisfaction expressed by its guests. Finally, the ATC examined pre- and post-Games travel patterns and the possibility for international visitors to return to Australia. Inevitably, the majority of the guests surveyed expressed a very high level of satisfaction in regards to hospitality issues and the organization of the Games. Most of the participants stated that sponsorship activities significantly affected their perception towards their Olympic experience in Sydney.

OLYMPIC SPONSORSHIP BEYOND BEIJING

The IOC has awarded the Olympic Games through 2012. The Vancouver Organizing Committee (VANOC) secured the rights to the 2010 Winter Games while London will host the 2012 Summer Olympic Games. Sponsors, both domestic and TOP VII partners, are beginning to line up. Five of the current TOP sponsors have extended through 2012 and Coca-Cola has renewed its sponsorship status through 2020. Bell-Canada bid $200 million to become the official telecommunications sponsor and RBC Financial paid $110 for the banking services rights. At this early stage it is interesting to note that VANOC’s 2003 bid documents only projected a total of $200 million from all sources.43 The 2012 London Organizing Committee is projecting revenues of $750 million from TOP sponsors and $600 million from domestic partners. While the allure of 1.3 billion Chinese fades into Olympic history, Vancouver and London are positioned to attract tourists and their economic impact to comfortable and secure destinations. In Olympic tradition, leaders of these economies will attempt to lure business development through their day on the Olympic stage.

CONCLUSION

It is evident that the complicated marketing policies and management structures of the International Olympic Committee have evolved into one of the best-managed global brand marketing association programs in the world, characterized by sophisticated and effective marketing structures. Olympic Games have become one of the most large-scale and profitable global media events. Events associated with the Olympic Games have not only become great entertainment, occupation, and lifestyle, but solid business as well.44 The history of Olympic sponsorship has demonstrated the increased financial dependency of the Olympic Movement on corporate sponsors. Arguments have been raised about the escalating price for the TOP level sponsorships. An online 2005 poll with Marketing Magazine found that 67% of respondents thought that Olympic sponsorship was out of proportion to its marketing value. However, the authors believe that the best indicator is to watch where marketers put their money. Clearly, the pace of Olympic marketing and sponsorship has not slowed. However, a lingering question is whether the nature of the Games will be influenced and altered in the near future due to commercialization and the increased financial dependency of the Olympic Movement on sponsors. IOC President Jacques Rogge appears steadfast in his commitment to keep sponsor images off the field of play. Yet as the price increases so may the demands of the corporate sponsors.

Research studies conducted by the IOC have illustrated the significant impact of Olympic sponsorship on the spectators’ perceptions of the Games. However, most of the studies were conducted with Olympic sponsors’ guests as the primary participants of the studies. It is inevitable that these studies would project a highly positive perception of participants in regards to the value of Olympic sponsors to the viability of the Olympic Movement, since the results are published in the IOC’s official marketing reports.

Are the Olympic Games transforming into the biggest financial opportunity for sponsors to showcase their products and services through global media exposure instead of being the biggest celebration of humanity and sportsmanship? Critics have always charged that the Olympic Games are more about marketing and less about sport. Previous Summer Olympics, such as the 1996 Atlanta Games, have been criticized for over-the-top marketing and a carnival-like atmosphere as well as for being another advertising medium deluging Olympic fans. The reality is that sponsorship has become an integral part of the Olympic Movement, which involves an ongoing commitment by Olympic partners who need to find new ways to gain the maximum returns for their investment. Olympic sponsorship has indeed a dynamic nature, since sponsors significantly support the viability of the Olympic Movement and the continuation of the Olympic Games. The question is whether the organization and staging of a mega event as the Olympic Games would be feasible without the financial contribution of corporate sponsors. The answer is that the Games would not be feasible, since the cost of staging the Games has increased dramatically over the past decade. It is clear that the current situation favors a long-term relationship between the IOC and a small number of sponsors. As Brown noted, “The IOC is placing more emphasis on promotion of the roles played by sponsors and on initiatives to ensure that sponsor exclusivity is preserved.”45 Unarguably, the IOC has achieved over the past decade, especially after the 1996 Atlanta Olympic Games, control of the commercial aspect of the Games by incorporating quality over quantity of corporate clients to the Olympic sponsorship program. However, the threat of ambush marketing and corruption scandals is always present. It would be interesting to see whether the IOC will continue to maintain its marketing and commercial control over Olympic partners based on the increased financial dependency of the Olympic Movement on corporate sponsorship. It is indeed a formidable challenge for the IOC to preserve the true essence of the Olympic Games by balancing terms such as sponsorship, return on investment, brand awareness, and benefits with Olympic ideals such as sportsmanship, human scale, noble competition, and solidarity. In a recent interview conducted by Sports Business Journal, Jacques Rogge was asked how he balances the Olympic ideals with commercialization. 46 Rogge replied:

First, let me remind you that the games are the sole organization where there is no billboarding in the venues. There is no advertising on the bib or equipment or clothing of the athletes. That gives a kind of commercial-free environment. The second issue is that we say and we think that the support of the corporate world has led to the democratization of sport.

Olympic sponsors will continue to seek new ways to leverage benefits for their investment in the Olympics. It is the IOC’s critical role to continue affiliating with sponsors that do not simply create “noise,” but with those sponsors who create “meaning” and add true value to the overall Olympic experience. According to Kronick and Dome “Olympic sponsorship is a marathon, not a sprint.”47 Building relationships, whether with the 1.3 billion people in China or with corporations and consumers in the developed economies of North America or Europe, epitomizes the objectives of Olympic Movement sponsors. The impact of Olympic sponsorship extends far beyond the IOC and a relative limited number of corporate sponsors and Olympic partners.

Considerable discussion has occurred within the IOC about changing the process by which the Games are awarded. Pundits at the IOC proclaim that awarding the Games (without a bidding process) to countries that are less economically developed will expand the Olympic ideals to a more global audience. However, one would be naïve to think that the corporations that grease the wheels of the Olympic machine would not have significant influence in those decisions. Previously noted statements from Coca-Cola about the Chinese market and the implied efforts of Volkswagen to secure automobile production and sales in China indicate that Olympic sponsorship appears to be more about the market than the Olympic Games. This could lead to a situation where the IOC would become a prisoner of its own success due to the increased dependency on the revenues from corporate partners. At what point do the Olympic Games become a traveling trade show to the world’s most lucrative markets where the entertainers are paid in medallions of gold, silver, and bronze?

The trend can already be seen in ticketing for the Games. For Torino, tickets to the Opening ceremony ranged from $250–850 US making it increasingly difficult for the average citizen to obtain Olympic Tickets. True there is an array of lower priced tickets, which have historically been available for less attractive sports. Unfortunately, tickets to more attractive sports are often secured by Olympic sponsors for use in corporate hospitality. Furthermore, the tickets frequently go unused as evidenced by the empty seats in lower tiers seen on the TV broadcasts of figure skating in the 2006 Games. Many true Olympic fans were left literally out in the cold. The Olympic Games are apparently following other marketing trends moving from Business-to-Consumer (B-2-C) marketing strategies to Business-to-Business (B-2-B). However the IOC needs to carefully balance the needs of corporate sponsors with the passion for the Games residing in Olympic fans around the globe. A stated goal of the IOC is “To ensure the independent financial stability of the Olympic Movement and thereby to assist in the worldwide promotion of Olympism.”48 If the IOC does not attend to this balance, Citius, Altius, Fortius may well become the motto of the Olympic sponsors rather than that of the Olympic athletes.

Notes

1. D. K. Stotlar, Developing Successful Sport Sponsorship Plans, 2nd ed. (Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology, 2005).

2. J. Lee, “Marketing and Promotion of the Olympic Games,” Sport Marketing Quarterly, Vol. 8, No. 3, 2005.

3. Stotlar, Developing Successful Sport Sponsorship Plans, 2005.

4. IOC, Athens 2004 Marketing Report (Lausanne: IOC, 2004).

5. P. Badinou, “Sports ethics in the ancient Games. Olympic Review, August September, 2001, pp. 59–61.

6. G. Brown, “Emerging issues in Olympic sponsorship; Implications for Host Cities,” Sport Management Review, 2000, Vol. 3, No 1, pp. 71–92.

7. Ibid.

….

9. R. Burton, “Olympic Games Host City Marketing: An Exploration of Expectations and Outcomes,” Sport Marketing Quarterly, 2003, Vol. 12, No.1, pp. 37–47.

10. Brown, “Emerging issues in Olympic sponsorship; Implications for host cities,” 2000.

….

12. For the whole question of Olympic sponsorship and the TOP program, see R.K. Barney, S.R. Wenn, S.G. Martyn, Selling the Five Rings: The IOC and the Rise of Olympic Commercialism (The University of Utah Press: Salt Lake City 2004).

13. Stotlar, Developing Successful Sport Sponsorship Plans, 2005.

14. Ibid.

15. Brown, “Emerging Issues in Olympic Sponsorship; Implications for Host Cities,” 2000.

16. S. Sleight, Sponsorship: What It Is and How To Use It, (London: McGraw-Hill, 1989).

17. Salt Lake City 2002 Marketing Report (Lausanne: IOC, 2002).

18. Ibid.

….

26. IOC, 2006 Marketing Fact File (Lausanne: IOC, 2006).

27. Ibid.

….

39. Brown, “Emerging Issues in Olympic Sponsorship: Implications for Host Cities,” 2000.

40. “At the Olympics, Less May Be More,” http://www.performanceresearch.com/index.htm, Accessed 17 February 2006.

41. IOC, “Salt Lake 2002 Overview,” Olympic Marketing Matters, Vol. 21, pp. 1–8.

42. “At the Olympics, Less May Be More,” http://www.performanceresearch.com/index.htm, accessed 17 February 2006.

43. E. Lazarus, “Creative Games Management,” Marketing Magazine, 110/17 (2005).

44. J. Lee, “Marketing and Promotion of the Olympic Games,” Sport Marketing Quarterly, 8/3 (2005.)

45. Brown, “Emerging Issues in Olympic Sponsorship: Implications for Host Cities,” 2000.

46. J. Genzale, “Keeper of the flame,” Sports Business Journal, 8/99, pp. 21–23.

47. S. Kronick, & D. Dome, “Going for an Olympic Marketing Gold Beijing 2008,” 2006.

48. IOC, 2006 Marketing Fact File.

Discussion Questions

1. What is the major revenue source for the Olympics?

2. What entity is charged with running the Olympic Games?

3. What strategies might an OCOG use to make a given Olympiad more profitable?

4. What role do volunteers play in putting on the Olympic Games?

5. How are the different expenditures related to an Olympiad categorized for the determination of profit?

6. Why do corporations, such as Coca-Cola, pay such large sums for sponsorship rights?

7. What problems do people perceive with the commercialization of the Olympic Games?

8. What are the positive aspects of Olympic commercialization?

9. What is the most equitable division of IOC revenues between the various stakeholders (IOC, OCOG, IF, NOC)?

10. How has the IOC’s reliance on the television networks and those contracts that are formed with these networks changed over time?

11. What city had the most substantial Olympic surplus? What is that surplus attributable to?

12. What is the true economic impact of hosting an Olympic Games?

13. How are the facilities that are built with the purpose of follow-up usage different than those that are built without any purpose of follow-up usage?

14. Whose leadership brought the Games into this era of relative financial stability? How was this done?

*This illustration may not accurately reflect the current organization of the USOC and is intended to provide the reader with an understanding of the USOC’s complex reporting structure.

*This illustration may not accurately reflect the current organization of the USOC and is intended to provide the reader with an understanding of the USOC’s complex reporting structure.