Chapter EIGHTEEN

INTRODUCTION

Sports business leaders, who face greater public exposure and scrutiny than executives in other industries, have long been confronted with pressure to ensure that their industry is diverse. The diversity emphasis has been focused primarily on race and gender. In recent years, a global diversity element has come into play as well. In general, sports has attained a leadership position for its on-field diversity, but has long lagged in diversity in the front office and ownership.

Well before Jackie Robinson integrated Major League Baseball in 1947, municipalities, led by New York City, often raised racial discrimination issues. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People made a number of pronouncements as well. Questions of policy were raised, including why publicly financed facilities should be used by enterprises that discriminate.

Even as far back as the search to find a “Great White Hope” to battle the first black heavyweight champion, Jack Johnson, race has been an ever-present part of the business of sports. Early in the last century, the race of the boxers in a bout was used to sell tickets and inspire interest. The race-baiting formula has been used over and over again, including, notably, the Larry Holmes–Gerry Cooney heavyweight championship bout decades later. Race sells in the marketing of a sporting contest.

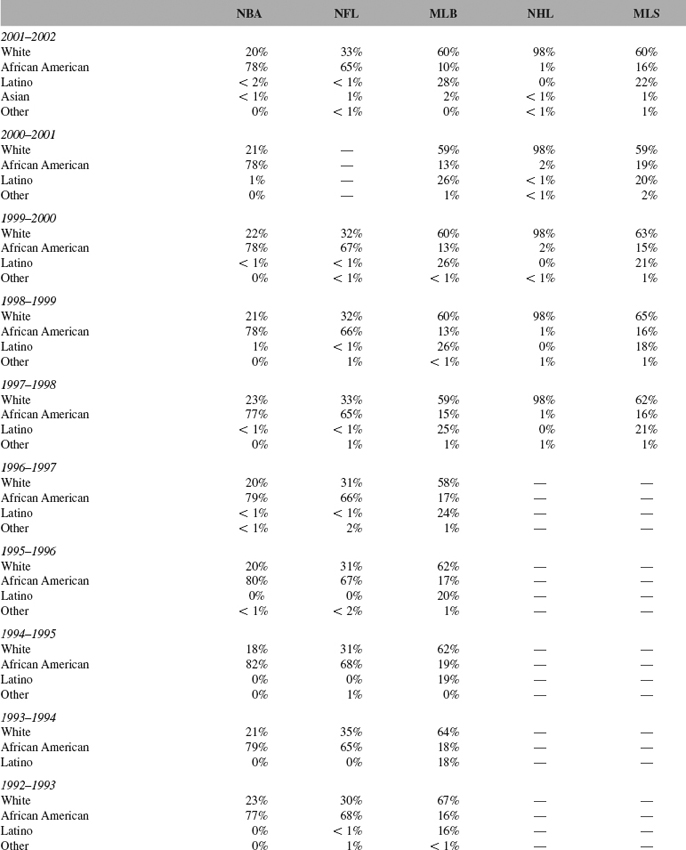

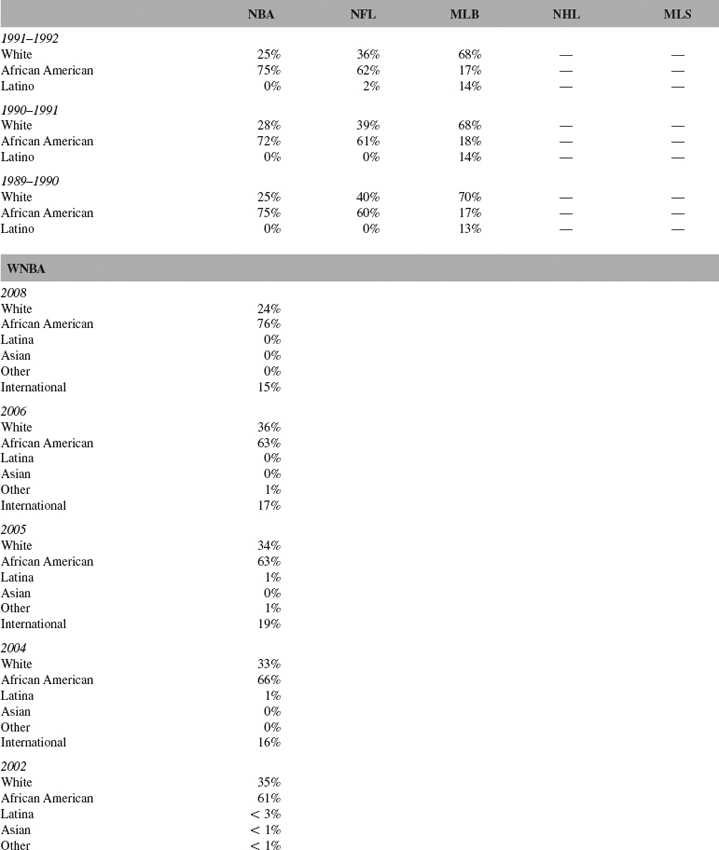

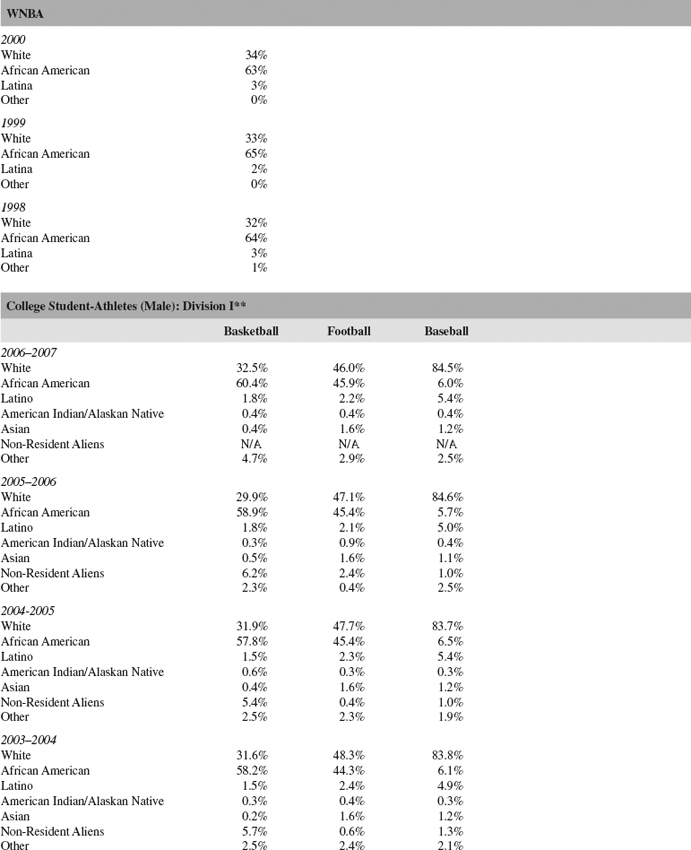

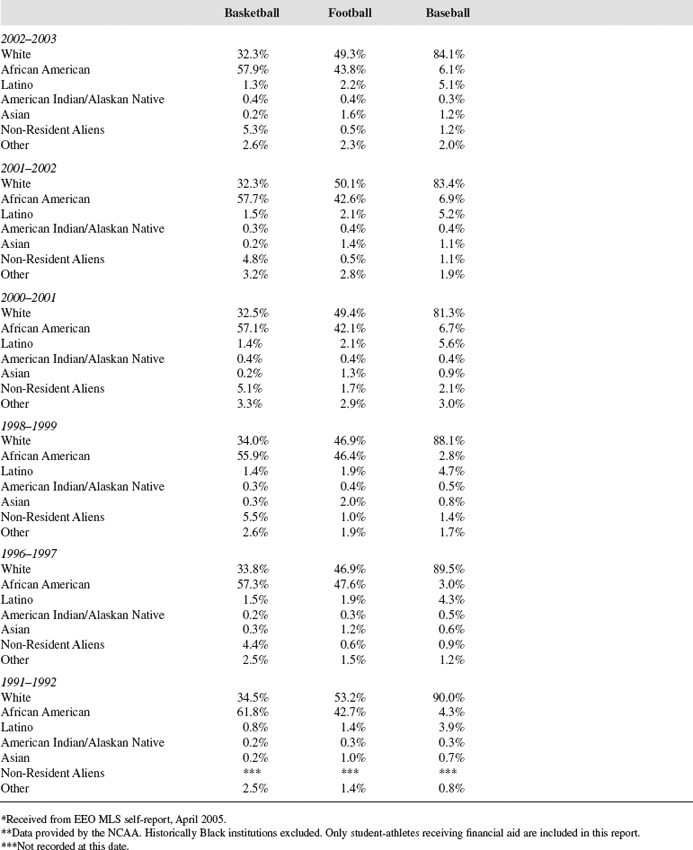

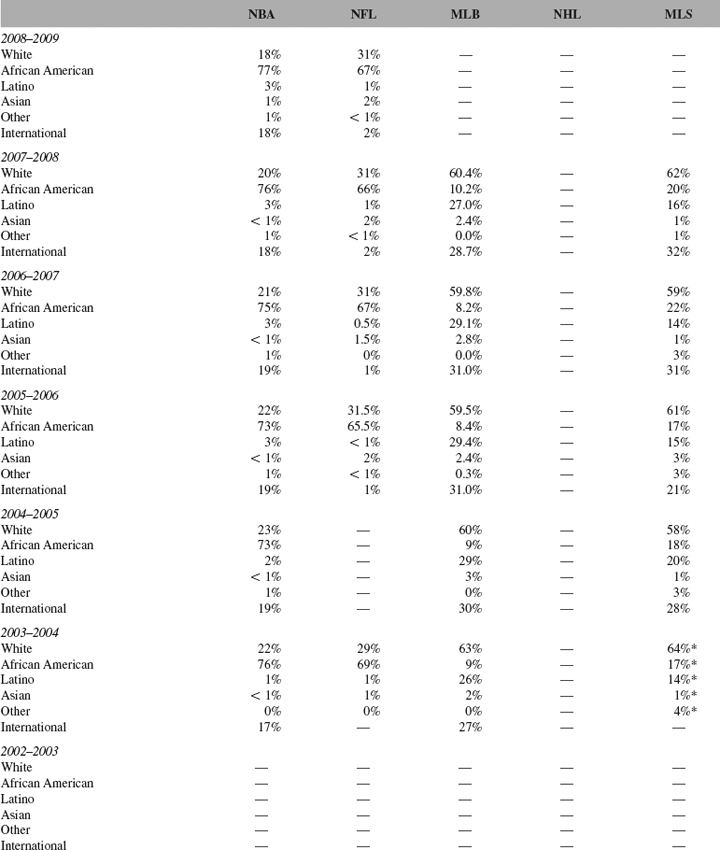

In the United States, the elimination of racial discrimination in sports largely occurred for practical reasons, not from any dramatic evolution of society’s hearts and minds. In post–World War II baseball, part of the motivation to recruit ballplayers from the Negro Leagues was simply to fill the need for more talent. Eventually it became the desire to expand the talent pool, as owners came to realize that much of the best talent was black. Ironically, this led to the demise of the Negro Leagues. That realization of the value of black talent ultimately occurred in other leagues as well. Table 1 shows the racial composition of players among leagues and in intercollegiate athletics in recent years.

The issue of racial diversity has evolved from players to management and ownership. In recent years, the NFL has shown dramatic success in the hiring of African American head coaches. This success has largely been attributed to the so-called “Rooney Rule.” This league-imposed rule requires that whenever a position for a head coach occurs at least one minority candidate must be interviewed for the job. Since the implementation of the rule in 2002, the number of African American head coaches has grown from a low of two to a high of seven. In 2009, the rule was expanded to apply to general manager positions as well.

When the ownership barrier in major league sports was knocked down by Bob Johnson in the NBA and Arte Moreno in Major League Baseball, it was done with little ceremony. Once those barriers were broken it became clear that, for the most part, the only color barrier to ownership in the new millennium was green—economics. That barrier is obviously not one that exclusively impacts sports.

Diversity has become a global issue as well. Soccer has formed a number of organizations, including Football Against Racism in Europe (FARE), to battle racism, which permeates many of its venues, particularly on game days. Similar to American sports, coaches and managers of color have been underrepresented in soccer as well.

Non-race-related diversity issues have evolved over time as well. The 1973 Billie Jean King–Bobby Riggs “Battle of the Sexes” tennis match held in the then-novel Houston Astrodome is symbolic of some of the barriers that have been overcome in these other areas. That spectacle revealed to many that the potential of women’s sports could extend beyond the moral obligation to promote gender equality to the realization of profit. This certainly led to a number of women’s sports leagues. Many of these are discussed in Chapter 4, “Emerging and Niche Leagues.” Other important issues related to women and diversity are discussed in Chapter 16, “Gender Equity.”

Table 1 Racial Composition of Players in Major Sports Leagues

Source: Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport, Racial and Gender Report Card.

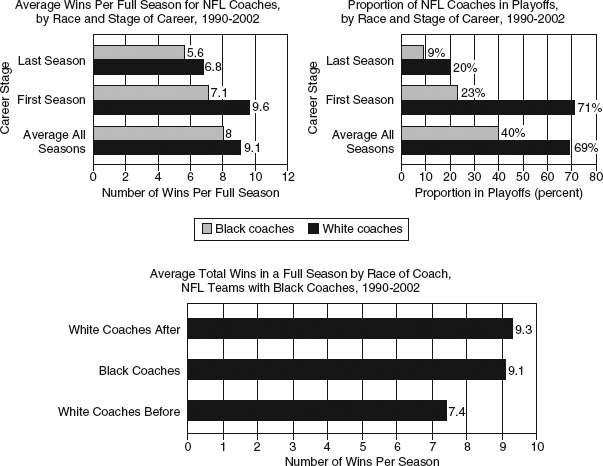

The first selection in this chapter, Edward Rimer’s “Discrimination in Major League Baseball: Hiring Standards for Major League Managers, 1975–1994,” illustrates some of the history of disparate standards used in managerial hiring decisions. At the time of its publication, it delivered a clear message to managers to beware of applying disparate standards in hiring. A more recent study by Janice Madden examines the issue in the NFL, focusing on the baseball manager equivalent, the head coach. The Madden study, and updates, may be viewed at http://www.findjustice.com/UserFiles/File/Report_-_Superior_Performance_Inferior_Opportunities.pdf. That research is described further in the article by Jeremi Duru which appears in this chapter. Since the publication of that earlier research, Madden has conducted a follow-up study to determine the impact of the Rooney Rule. Her conclusion is that the statistical bias that was found earlier against the hiring of African American head coaches no longer exists. This success must, in part, be attributed to the Rooney Rule. See Figure 1 for a snapshot of those original findings.

The readings in this chapter provide the sports business leader with a broad swipe at these issues as well as some of the approaches used to address them. Duru’s article, “The Fritz Pollard Alliance, The Rooney Rule, and the Quest to ‘Level the Playing Field’ in the National Football League,” provides insight into the Rooney Rule. The excerpt from Shropshire, “Diversity, Racism, and Professional Sports Franchise Ownership: Change Must Come from Within,” focuses on ownership. The discussion in this selection highlights the limitations of the law in bringing about change. The piece was written before Bob Johnson (and now Michael Jordan) and Arte Moreno obtained their respective ownership interests. However, no other African Americans or Latinos have yet acquired a controlling ownership interest in a major North American team sport. The excerpt from Kahn, “The Sports Business as a Labor Market Laboratory,” focuses on salary discrimination and contract termination issues. The selection provides an overview of the research available on the issue of differences in pay to players based on race. Race and sports is a global issue, too. The article by Ryan, “The European Union and Fan Racism in European Soccer Stadiums: The Time Has Come for Action” examines the race issue in European soccer. The lessons from all of these excerpts are applicable to broader diversity issues as well.

MANAGERS AND COACHES

DISCRIMINATION IN MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL: HIRING STANDARDS FOR MAJOR LEAGUE MANAGERS, 1975-1994

Edward Rimer

In 1975, the Cleveland Indians hired Frank Robinson to be their manager, the first Black to hold such a position in Major League Baseball. This occurred 28 years after Jackie Robinson had successfully integrated professional baseball. As befalls most managers, Frank Robinson was fired and, subsequently, was rehired by two other teams [Ed. Note: now three]. Although other Blacks have become managers and there have been several Hispanic managers, there remains a belief that minorities are not given an equal opportunity to assume administrative and managerial positions in the major leagues. [Ed. Note: See Figure 1 for racial comparisons of coaches in the NFL.]

The purpose of this article is twofold. First, I analyze the backgrounds of those individuals who were managers during the past 20 years (1975–1994) to ascertain what were the implicit standards, if any, that the owners used in making their hiring decisions. Second, having identified such standards, I compare the backgrounds of Black, White, and Hispanic managers to determine whether the standards were applied equally to all managers.

This study differs from previous work in that it seeks to determine what were the standards used to hire managers and whether such standards were applied equally to Blacks, Hispanics, and Whites. The focus is on the hiring actions of the teams, and on whether the qualifications were applied uniformly to all who became managers, rather than on the behaviors of individuals seeking managerial positions.

Historically, employers have used two methods to screen out and discriminate against applicants for certain positions. Applicants [first] may be asked to possess some non-job-related attributes. Courts have continually ruled that employers must demonstrate that the requirements for a job must be essential for its successful completion.

Second, these job-related requirements must be applied equally to all applicants. Personnel management law is replete with edicts that standards must be applied equally in diverse areas such as hiring, firing, compensation, and benefits. In fact, current human resource management theory posits that other functions, such as performance appraisal, also suffer when dissimilar standards are used to evaluate employees. Employers have been able to defend their personnel actions when they have been able to demonstrate that the qualifications are job related and applied equally to all applicants.

Figure 1 Black vs. White Coaching Success in NFL

Source: Journal of Sport and Social Issues. Used with permission.

… This study attempts to determine whether the job-related requirements were applied equally to all who became managers between 1975 and 1994. In this manner, we would have some indication as to how the courts might rule should an individual seek legal remedies against a team alleging discriminatory hiring/promotion practices.

This is accomplished by comparing the prior jobrelated work experiences of Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics who were managers during the past 20 years, 1975–1994. The purpose of this study is to ascertain whether White, Black, and Hispanic professional baseball players had to possess different attributes to be hired as major league managers. Further, I discuss the extent to which these different hiring standards may preclude or facilitate future success as a manager.

Managerial Skills, Knowledge, and Abilities

Managers need to possess a knowledge of baseball so that they can make strategic decisions as the game progresses. This normally involves setting the starting lineup, determining the starting pitching rotation, and determining when to pinch hit, remove the pitcher, and numerous other options (steal, hit-and-run, etc.) that may occur during a game. Whereas the average fan may have some rudimentary understanding of these aspects of the game, the manager is expected to make these decisions while being cognizant of his team’s abilities as well as what the opposition will do to counter his actions. This knowledge of the game can be gained by anybody playing the game. It is not limited to those who play for specific teams or at certain positions.

Managers also serve as teachers, assisting their players in some of the finer points of the game. Aspects of hitting, fielding, and pitching are all within the purview of the manager. It is common to hear players give credit to their managers and to see photographs in the newspapers (particularly during spring training) of a manager holding a bat and demonstrating a swing or gripping a bat while a circle of players is gathered around him. Managers must also possess leadership abilities. Although their specific styles may differ, managers must be able to instill in their players the confidence and loyalty to perform at their peak performance levels. The ability to teach and be an effective leader is not limited to certain types of players. The literature on both teaching and leadership indicates that there is more than one effective style, and a cursory review of baseball history indicates that infielders, outfielders, pitchers, and catchers have been effective managers.

Whereas knowledge of the job, knowledge of the jobs of those they supervise (the players), and the ability to lead are quite similar to the case of generic management, baseball is unique in that the prior job-related experiences of managers (as players and/or coaches) are readily available and easily quantifiable. The ability to quantify performance has been an essential part of the studies on salary discrimination. Here, however, prior records are evaluated in terms of qualifications for the job as manager. Three distinct prior job-related experiences are analyzed. Specifically, I compare the records of the managers as players, focusing on longevity and several career performance statistics to measure their knowledge of Major League Baseball and potential ability to be major league managers.

Longevity provides the individual with a greater opportunity to learn about the game, leadership techniques, and the like. Managerial experience at the minor league level is used to assess previous opportunities to exercise leadership, and major league coaching background is used as a measure of their teaching and instructional expertise.

The Managerial Pool, 1975–1994

Between 1975 and 1994, 140 different individuals held the position of manager of a Major League Baseball team. Of these 140, 39 had managed prior to 1975; Frank Robinson was the only new manager to begin the 1975 season. In 1975, there were 24 teams. Two teams were added to the American League in 1977, and two teams were added to the National League in 1993. During this 20-year time period, major league teams changed managers 210 times, creating an average of more than 10 opportunities per year for major league teams to hire new managers. Of the 24 managers who started the 1975 season, none was managing the same team at the conclusion of the 1994 season. Of the original 24 managers in 1975, 20 were subsequently rehired by other teams after being terminated. There was a constant turnover of managers, thus providing ample opportunity for the hiring of Black and Hispanic managers.

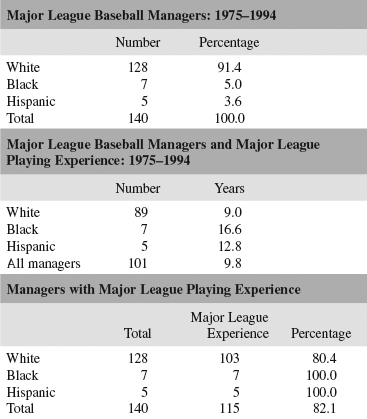

Of the 140 managers, there were 7 Black managers (Don Baylor, Dusty Baker, Larry Doby, Cito Gaston, Hal McRae, Frank Robinson, and Maury Wills) and 5 foreign-born Hispanic managers (Felipe Alou, Preston Gomez, Marty Martinez, Tony Perez, and Cookie Rojas). [See Table 2.] In addition, 12 individuals managed fewer than 42 games or 25% of a full season. Marty Martinez, who managed 1 game with Seattle in 1986, is the only Black or Hispanic who managed fewer than 42 games. Many of these individuals who managed a limited number of games were hired on an interim basis. This is taken into account when I compare their managerial experiences.

Table 2 Racial Differences in Managerial Selection

Source: Journal of Sport and Social Issues. Used with permission.

RESULTS

Managers as Major League Players

The most notable prerequisite to being a major league manager is to have played in the major leagues. By performing at the major league level, players demonstrate their abilities under the most repetitive conditions and gain firsthand knowledge of how the game is played and the performance required to succeed at the highest level.

Of the 140 managers, 25 never played at the major league level. Of the remaining 115, 6 were pitchers. Consistent with earlier findings, most played second base or shortstop (47), followed by catcher (25)…. All 25 who did not have major league experience as players were White. All 6 managers who were pitchers in the major leagues were White.

A comparison of the experience of White, Black, and Hispanic managers as major league players reveals that the Black and Hispanic managers have had more extensive and productive careers than have their White counterparts. This is true even after eliminating from the comparison all of the White managers who never played at the major league level….

Even after excluding White managers who never played at the major league level and therefore raising the mean experience for Whites, Black managers have approximately twice as much major league experience as do White managers (i.e., 84% longer, 136% more games, and 159% more at bats). The major league careers of Hispanic managers are 42% longer, having played in 72% more games and with 82% more plate appearances.

Because there is a limited number of Black and Hispanic managers compared to White managers, and because the analysis includes the entire population, no test for statistical significance was performed. I did calculate the standard deviation of each mean to reveal the extent to which there is variation within the White, Black, and Hispanic managers. The greatest variance is among the Hispanic managers, whereas the least is among the Black managers.

As with career longevity, Black and Hispanic managers outperformed the White managers in all offensive categories [as major league players]. Blacks, on average, scored more than twice as many runs and had l76% more hits, 406% more home runs, 249% more runs batted in, and a batting average 7% higher than did White managers. Hispanics also outperformed White managers, but not to the same extent as did the Black managers: 88% more runs, 91% more hits, l63% more home runs, 120% more runs batted in, and a batting average 5% higher than those of White managers. Interestingly, there is less variance among White managers regarding the performance criteria, with Hispanics showing the greatest variance.

Minor League Managerial Experience

In addition to being a player, managing at the minor league level is often considered a prerequisite for obtaining a major league managerial job. It is as a manager that the individual gains experience in game strategy, leadership, and interactions with team administration. Of the 140 managers, almost 70% had managed at the minor league level….

Felipe Alou, Frank Robinson, and Preston Gomez are the only minority major league managers with prior experience as minor league managers….

Whereas the length of experience and performance appears similar, the percentage of Blacks and Hispanics with minor league managerial experience is less than the percentage of Whites with minor league managerial experience. The variance between those who have managed at the minor league level is also similar.

….

DISCUSSION

Standard employment practices compel employers to demonstrate that requirements for a position are job related and that such job requirements are applied equally to all candidates for the position. Baseball managers need to have a knowledge of the game, the ability to teach, and the ability to lead. I identified three prior job-related experiences that are likely to provide the individual with these necessary skills, knowledge, and abilities: major league playing experience, minor league managerial experience, and major league coaching experience.

All but one of the men who managed between 1975 and 1994 had some experience as either a major league player, a minor league manager, or a coach of a major league team. The lone exception, Atlanta Braves owner Ted Turner, managed for one game in 1977. It thus appears that these three conditions are used by teams as part of the hiring process and are considered to be job-related prerequisites for employment as a manager. It is also evident from the analysis that these three qualifications are not considered to be an absolute requirement. Only 55 of the 140 managers (39%) had experience in all three areas studied. Some combination of playing experience, minor league managerial experience, and major league coaching experience is deemed appropriate to be hired as a manager.

The requirement that a manager have major league playing experience was not applied equally to all who were managers between 1975 and 1994. All Black and Hispanic managers had to have played at the major league level and had to have had longer and more productive careers as players than was the case with White managers. This is true even after eliminating from consideration the 25 White managers who never played major league baseball. Only 80% of the White managers had major league playing experience, whereas 100% of the minority managers had performed at the major league level. The data reveal that heightened expectations regarding length of time in the major leagues were applied consistently to all Black managers.

Previous studies would lead one to conclude that this difference in the performance standards is attributable to position segregation. Seven of the minority managers were primarily outfielders (58% of all minority managers as compared to only 9% of White managers were outfielders), and outfielders have consistently had to be more productive in terms of offensive performance. The data reveal, however, that minority outfielders who became managers had longer and more productive careers than did White outfielders who became managers.

….

Between 1975 and 1994, only 18 outfielders became managers. This is consistent with previous research regarding position centrality. However, the total playing, coaching, and minor league managerial experience of minority and White outfielders is different. The minority outfielder/managers spent an average of 23 years as player, coach, and minor league manager; whereas the average was 17 years for the White outfielders with major league playing experience who became managers. There were several White managers who were outfielders but had not played at the major league level.

Minority outfielders who became managers were coaches for an average of 4 years, whereas the White outfielder/managers were coaches for an average of 2 years. Only 28% of the minority outfielder/managers had minor league managerial experience, whereas 55% of the White outfielder/managers managed at the minor league level. The average number of years of managing in the minor leagues was almost equal: 1.8 for the minority outfielders and 2.7 for the White outfielders. The limited number of Black or Hispanic managers who played positions other than outfielder precludes any meaningful comparison to the White managers.

The data show that no marginal Black players, either those who did not make it to the major leagues or those who had limited major league careers, were ever selected to be major league managers during the past 20 years. Although it is not known with any certainty who may have applied for these positions, there are several Blacks with limited playing careers who became coaches but never became managers (e.g., Tommie Aaron, Gene Baker, Curt Motton, and, most recently, Tom Reynolds).

A cursory look at the White managers who did not play at the major league level indicates that a lengthy playing career cannot be considered an essential prerequisite for superior performance as a manager. Two of the more successful managers in the past and present, Earl Weaver and Jim Leyland, are among the 25 who never played Major League Baseball. This leads one to consider the impact on the effectiveness of minority managers who, it appears, are required to possess certain characteristics that are not necessarily correlated with success as a manager. Further analysis of the relationship between a manager’s playing career and managerial record is necessary.

The situation is somewhat reversed when we examine managerial experience in the minor leagues. Although it is the weakest of the three elements (only 69% of all managers had minor league managerial experience), the majority of Black and Hispanic managers did not have an opportunity to manage in the minor leagues. The length and performance of those who did are similar for Blacks, Whites, and Hispanics.

Star players may be hesitant to spend time in the minor leagues, even if it is as the manager of the team. Data on player performance at the major league level indicate that most of the minority managers could be considered star players. Offers to coach at the major league level may appeal to both the player and team, as the player is more visible to the fans. It should be noted that there are numerous star White players who became managers without first obtaining managerial experience in the minor leagues. Yogi Berra, Alvin Dark, Toby Harrah, and Pete Rose are some of the more prominent to follow this career path. Further study is needed to determine the extent to which being a minor league manager provides invaluable experience that is not obtained by either playing or coaching.

….

The large variance in the means for player longevity, performance categories, and years and games managed in the minor leagues indicates the absence of precise prerequisite criteria. A total of 65 managers (46%) had experience in two of the three categories. In addition, 20 were players and minor league managers, 30 were players and had prior coaching experience, and 15 had managed minor league teams and coached. Previous studies of managerial performance have taken into account the abilities of the players managed and the teams’ won–lost records (Horowitz, 1994; Jacobs & Singell, 1993; Kahn, 1993; Porter & Scully, 1982), and neglected to include the backgrounds of the individual managers. Porter and Scully’s evaluation of managers with 5 or more years of experience between 1961 and 1980 determined that Earl Weaver, Sparky Anderson, and Walter Alston were the most efficient. Horowitz’s methodology also concluded that Weaver and Alston were among the best major league managers. Given that these three had limited, if any, major league experience as players (Alston, 1 at bat; Anderson, 1 year with 477 at bats; Weaver, no major league playing experience), we should be cautious before assuming that playing can substitute for minor league [managing] or coaching experience. To the extent that Blacks and Hispanics have longer playing careers and limited coaching and previous managerial experience, they may be at a disadvantage in terms of the training and background necessary to succeed as a manager. Further study is needed to determine what combination of the three job-related activities is most closely related to superior performance as a manager. Additionally, further study is needed to determine whether and to what extent the position played at the major league or minor league level affects the number of years considered appropriate experience and, therefore, the need to be a minor league manager or major league coach before becoming a major league manager.

This study examined the background of all major league managers from 1975 through 1994. Specifically, it compared the playing records, minor league managerial experience, and coaching experience of all those who managed during the past 20 years. All but one (Ted Turner, a team owner) had some combination of the specified job-related experiences. We can thus conclude that these criteria are considered by owners when they hire managers. The amount of experience required as a player, minor league manager, or coach was different for Black, White, and Hispanic managers. Blacks and Hispanics had longer and more productive careers as players than did their White counterparts. Further, there were differences between the minority and White outfielders who became managers. A comparison of the playing careers of the minority and White outfielders who became managers revealed that the minority outfielder/managers outperformed the Whites in all offensive categories and had nearly an identical batting average. Minority managers tended to be outfielders, a position in which they are overrep-resented but a position that has produced a limited number of managers. Black and Hispanic managers had less minor league managerial experience than did White managers and had similar experience as major league coaches. It would appear that major league baseball teams, although using appropriate job-related criteria in the hiring of managers, did not apply these criteria in an equitable manner.

References

Horowitz, I. (1994). Pythagoras, Tommy Lasorda, and me: On evaluating baseball managers. Social Science Quarterly, 75, 187–194.

Jacobs, D., & Singell, L. (1993). Leadership and organizational performance: Isolating links between managers and collective success. Social Science Research, 22, 165–189.

Kahn, L. (1993). Managerial quality, team success, and individual player performance in major league baseball. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 46, 531–547.

Porter, P., & Scully, G. (1982). Measuring managerial efficiency: The case of baseball. Southern Economic Journal, 49, 642–650.

THE FRITZ POLLARD ALLIANCE, THE ROONEY RULE, AND THE QUEST TO “LEVEL THE PLAYING FIELD” IN THE NATIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE

N. Jeremi Duru

INTRODUCTION

The National Football League (the “NFL” or the “League”), like the National Basketball Association (“NBA”) and Major League Baseball (“MLB”), has a long history of racial exclusion.1 And like these other long-standing American professional sport leagues, desegregation among players preceded desegregation among coaches.2 As slowly increasing numbers of minorities assumed NBA head coaching positions and MLB managing positions toward the end of the twentieth century, however, minority coaches were less likely to receive head coaching opportunities than their basketball and baseball counterparts.3 Indeed, as of 2002, only two minorities held head coaching positions in the thirty-two team NFL, and only five, including those two, had held head coaching positions during the League’s modern era.4 Four years later, however, the NFL had more than tripled its number of minority head coaches and shone as a model for other athletic institutions seeking to provide head coaching candidates equal employment opportunities.5

This article seeks to explore the history of racial exclusion in the NFL, the particular barriers minority coaches seeking NFL head coaching positions have faced, and the effort to level the playing field for such coaches…. Part II explores the travails of the NFL’s first three post-rein-tegration coaches of color as well as statistical evidence revealing that, as of 2002, NFL coaches of color generally suffered inferior opportunities despite exhibiting outstanding performance. Part III examines the campaign launched by attorneys Cyrus Mehri and Johnnie L. Cochran, Jr. to alter NFL teams’ hiring practices, the creation of the Rooney Rule (the “Rule”), and the birth of the Fritz Pollard Alliance of minority coaches, scouts, and front office personnel in the NFL. Finally, Part IV traces the Rooney Rule’s success in creating equal opportunity for coaches of color in the NFL.

[Ed. Note: The author’s discussion of the history of racial exclusion in the NFL is omitted.]

….

In 2002, civil rights attorneys Johnnie L. Cochran, Jr.50 and Cyrus Mehri51 commissioned University of Pennsylvania economist Dr. Janice Madden to analyze the performance of NFL head coaches during the fifteen years between 1986 and 2001 and to compare the success of the five black head coaches who coached during that period against the success of the eighty-six white head coaches who coached during the same period.52 Dr. Madden concluded that, by any standard, the black head coaches outperformed the white head coaches: “No matter how we look at success, black coaches are performing better. These data are consistent with blacks having to be better coaches than the whites in order to get a job as head coach in the NFL.”53

Indeed, in every category Dr. Madden studied, black coaches outperformed white coaches.54 In terms of total wins per season—the primary category upon which a head coach’s performance is assessed—55 black coaches averaged over nine wins, while white coaches averaged eight wins.56 While the 1.1 win differential might, at first blush, seem a minor matter, considering that NFL teams play only sixteen games during each regular season, one additional win is extremely significant.57 Further, no win is more significant than the ninth, as, during the fifteen years studied, sixty percent (60%) of teams winning nine games advanced to the playoffs while only ten percent (10%) of teams winning eight games advanced to the playoffs.58

The disparity in success is even more pronounced when considering coaches’ success in their first seasons with a team.59 In their first seasons, black coaches averaged 2.7 more wins than did white coaches in their first seasons and, accordingly, were far more likely to advance their teams to the playoffs than were white coaches.60

In addition, in their last seasons before being fired, black coaches outperformed their white counterparts.61 Black coaches won an average of 1.3 more games in their terminal years than white coaches, and while twenty percent (20%) of the black coaches who were fired led their teams to the playoffs in the year of their firing, only eight percent (8%) of white coaches did the same.62

III. THE CAMPAIGN TO CHANGE THE NFL

Based on Dr. Madden’s results, Cochran and Mehri authored a report titled, Black Coaches in the National Football League: Superior Performances, Inferior Opportunities. They concluded, based on Dr. Madden’s results, that black head coaches faced more exacting standards than white head coaches and were often dismissed under circumstances that would not have resulted in white head coaches’ dismissals.63 As stark as Madden’s results were, Mehri and Cochran, of course, did not conclude black head coaches were somehow inherently better than white head coaches. Rather, they concluded that because barriers to entry facing black coaches seeking head coaching positions were more formidable than those facing white coaches, the black coaches able to surmount those barriers were exceedingly well equipped to succeed as head coaches. And, of course, as a consequence of those exceedingly high barriers, they argued, many black assistant coaches never received serious consideration for head coaching jobs.64 Cochran and Mehri’s report ultimately concluded that despite statistically “superior performance,” black coaches have received “inferior opportunities”: “In case after case, NFL owners have shown more interest in—and patience with—white coaches who don’t win than black coaches who do.”65

Armed with this conclusion and statistically significant analyses to support it, Cochran and Mehri possessed critical information in confronting employment discrimination: persuasive evidence that the discrimination actually exists. Over forty years after Congress issued broad-based antidiscriminatory legislative edicts, Americans are reluctant to acknowledge discrimination existing in their organizations.66 Racial bias and discrimination in America is now more subtle than overt, and, according to some scholars, often sub-conscious.67 Consequently, the suggestion of racial discrimination’s existence may, and often does, strike institutions’ executives as inaccurate and offensive, prompting fierce denials and dampening the possibility of sincere and meaningful settlement negotiations.68

Statistically significant evidence of systemic discrimination buttressed by anecdotal evidence of that discrimination’s impact—as opposed to anecdotal evidence alone—is often crucial in prompting institutions to honestly confront the existence of discrimination. Cochran and Mehri had just that, which was sufficient to convince the NFL, which had to its credit previously expressed concern as to the lack of diversity among its head coaches,69 that some level of cooperation, as opposed to confrontation, was in order. And, indeed, shortly after the report’s publication, the NFL displayed leadership by creating a committee dedicated to increasing equal employment opportunity for NFL coaching candidates.70 Consisting of the owners of several of the League’s teams and chaired by Pittsburgh Steelers owner Dan Rooney, the Workplace Diversity Committee set out to consider the remedial recommendations Cochran and Mehri proffered.71

A. Crafting the Rooney Rule

The most notable of Cochran and Mehri’s recommendations was the mandatory interview rule. Arguing that racial bias, whether conscious or unconscious, was steering teams away from head coaching candidates of color, Cochran and Mehri contended NFL teams should be made to do what few had theretofore done—grant candidates of color meaningful head coach job interviews.72 Given the opportunities, they believed, coaching candidates of color would exhibit preparedness for head coaching jobs; the coaches of color simply needed the opportunities to compete for positions.73 Cochran and Mehri, therefore, suggested that each NFL team searching for a head coach be required to interview at least one minority candidate before making its hire.74 Crucial to the suggestion was that the interview be meaningful—that it be an in-person interview and that the interviewers be among the team’s primary decision-makers.75

After some deliberation, the Workplace Diversity Committee recommended the Rule to the broader group of NFL team owners, and the owners agreed by acclamation to implement the suggested rule.76 All parties agreed the rule should require nothing beyond a meaningful interview, and that if after the interview the interviewing team chose to hire a non-minority coach, the choice was its to make.77 In December of 2002, the NFL announced its mandatory interview rule, which would come to be known as the Rooney Rule in honor of the Workplace Diversity Committee’s chairman, Dan Rooney,78 and which would prove to fundamentally change the NFL.79

From the start, the Rooney Rule met with significant skepticism.80 Indeed, criticism rained down from all quarters. NFL insiders questioned the League’s decision to take its lead in pursuing diversity from two lawyers previously unaffiliated with the League and its internal mechanisms. If anyone should guide the League on these issues, they argued, he or she should be from the football community—from a group of NFL alums or from the League’s, or one of its team’s, front offices. Others, recognizing the Rule contained no accompanying penalty mechanism, wondered whether teams would bother to heed the rule, and if they didn’t, whether the League would do anything about their failures to do so.81 Still others argued that even assuming teams followed the Rule, because the interviewing team had no obligation to hire a minority coach, the interview would prove merely ornamental.82 Burdened with these criticisms, the Rooney Rule’s early life was shaky.

B. The Birth of an Alliance

Those questioning the propriety of the NFL’s reliance on outsiders with no connection to the NFL community to guide its equal employment opportunity efforts would soon be silenced.

Shortly after Cochran and Mehri issued their report, Floyd Keith, the Executive Director of the Black Coaches Association (“BCA”), an advocacy organization of black collegiate coaches,83 suggested the lawyers consult with John Wooten, a former NFL All-Pro offensive lineman well-known throughout the League for his tenacity and intellectual acuity both on and off the field.84 While Wooten was a remarkable player, he made his most lasting impact in NFL front offices, where he worked in various high-level capacities with the Dallas Cowboys, the Philadelphia Eagles, and the Baltimore Ravens over the course of almost thirty years.85 More impressive than Wooten’s success as a player or front office executive, however, was his unwavering and expressed commitment to racial equality in the NFL. For years, Wooten decried the almost entirely homogenous composition of the NFL’s head coaching ranks. Having played with and against scores of fellow black players whom he knew would, if given the opportunity, excel as NFL head coaches, Wooten was incensed at their exclusion.

Cochran and Mehri’s report offered quantitative support for what Wooten knew: with a fair chance to take the reins of an NFL team, black head coaches would perform as well, if not better than, white head coaches. Wooten also knew that many black coaches in the League who had consistently been passed over for head coaching positions were anxious to meaningfully compete for those positions and would support the lawyers’ efforts. Wooten committed to assisting Cochran and Mehri’s work in any way he could and suggested they travel to Indianapolis, Indiana, in February of 2003 to meet with the NFL’s black coaches during the NFL Scouting Combine. The Combine, which serves as a nearly week-long tryout for collegiate players seeking NFL jobs,86 is the one occasion on which all of the League’s teams and their staffs can be counted on to be in one place and, therefore, presented the perfect opportunity for Cochran and Mehri to meet and share ideas with the individuals they were hoping to help. The lawyers recognized that in order to initiate true reform in the NFL, the primary stakeholders would have to engage in the battle, and they hoped a meeting at the Combine would galvanize their interest in organizing as a unit.

Although Cochran was unable to attend, Mehri represented them both at the Combine. What Mehri imagined would be a gathering of a few dozen black coaches turned out to be a meeting of over one hundred black coaches, scouts, and front office personnel, all deeply concerned about equity in the NFL. The group, though, was not a monolith. Some in the room expressed reluctance to push the NFL and its teams too vociferously for fear of backlash. Others, exceedingly frustrated with lack of opportunity, felt no push could be hard enough. Still others staked out middle ground positions. Overwhelmingly, however, those in the room supported increased organization among them. They wanted to maintain a connection in order that there be a forum in which to engage issues that they, as black coaches, scouts, and front office personnel in the NFL, shared. And they did so, forming an organization and naming it in honor of the individual who preceded and inspired them all. They became the Fritz Pollard Alliance (“FPA”), an affinity group dedicated to equal opportunity of employment in the coaching, scouting, and front office ranks of the NFL.87

There was little doubt Wooten would serve as the fledging organization’s chairman, guiding its vision and maintaining a strong relationship with the NFL, where he previously worked and maintained many close contacts and personnel friendships. And when Wooten considered who might effectively manage the organization’s affairs and serve as its public face, a few individuals came to mind, but none more compelling than Kellen Winslow, Sr.

Winslow, one of the NFL’s all time great players, was a tight end with the League’s San Diego Chargers from 1979–1987, during which time he set numerous League records and revolutionized the position.88 Whereas tight ends before Winslow were primarily utilized as blockers and rarely called upon to catch anything other than short passes, Winslow combined superior blocking skill with speed and pass-catching ability to rival even the best wide receivers.89 Along with his physical abilities, Winslow mixed intelligence, dogged persistence, and compelling leadership ability to become a Hall of Fame player;90 the type of player capable of willing his team to win.91 Because of these characteristics and his tremendous success as a player, Winslow naturally presumed he would, upon retirement, have opportunities to work in the NFL or in major conference collegiate football.92 Retirement, however, brought with it a crushing realization when the opportunities he envisioned did not materialize. As Winslow described in his foreword to In Black and White: Race and Sports in America, Kenneth Shropshire’s incisive investigation of the intersection of race and sport:

As long as I was on the field of play I was treated and viewed differently than most African-American men in this country. Because of my physical abilities, society accepted and even catered to me. Race was not an issue. Then reality came calling. After a nine-year career in the National Football League, I stepped into the real world and realized … I was just another nigger … the images and stereotypes that applied to African-American men in this country attached to me.93

Winslow’s revelation led him to channel his talents toward exposing inequity in the sports industry, and when he agreed to serve as the FPA’s Executive Director, he carried that passion with him….

As a consequent of the FPA’s support, the Rule, which was just a few months earlier decried as the brainchild of outside agitators, suddenly enjoyed endorsement from a body representing coaches, scouts, and front office personnel of color throughout the League. The Rooney Rule had gained instant credibility.

Credibility, however, offered no guarantee of efficacy, and if the Rule were to be effective, it would need teeth. Detroit Lions’ General Manager Matt Millen’s approach to hiring a new head coach in 2003 would ensure that it had them. In January of that year, the Lions fired their head coach Marty Mornhinweg, after the team suffered through a lackluster season during which they lost thirteen games and won only three.95 Three weeks earlier, the San Francisco 49ers had fired their longtime head coach, Steve Mariucci.96 Millen wanted Mariucci to lead the Lions and he expressed little interest in maintaining an open mind to other potential candidates. In his single-minded pursuit of Mariucci, Millen hired Mariucci without interviewing any candidates of color.97 While such a hiring process would have been unobjectionable just a few months earlier, under the Rooney Rule it was facially non-compliant.

The NFL’s then-Commissioner, Paul Tagliabue, had his test case, and his response would determine the Rule’s fate. If Tagliabue responded with inaction or an empty condemnation, the Rule would be rendered useless as a change agent. It would exist as little more than a symbolic gesture, creating the impression of a League dedicated to equal employment opportunity for coaches of color in the NFL, but having no actual impact. If, on the other hand, Tagliabue substantially punished the Lions, he would, in doing so, signal the NFL’s commitment to the Rooney Rule and to the equity Cochran, Mehri, and the FPA sought to achieve.

Tagliabue’s decision shocked even those hoping for a stout punishment. Explaining that Millen “did not take sufficient steps to satisfy the commitment that [the Lions] made” regarding the Rooney Rule, Tagliabue fined Millen $200,000, and explicated that Millen, not the team for which he worked, would have to pay the fine.98 With the fine, Tagliabue made clear that as the Lions’ principal decision-maker, Millen was responsible for following the League’s mandatory interview guidelines, and he would have to pay account.

Notably, Tagliabue did not stop at issuing the fine. He went further still, moving away from the facts of the Lions’ inadherence and issuing broad-based notice as to the League’s unwavering commitment to the Rule. The next principle decision-maker to flout the Rule would, Tagliabue promised, suffer a $500,000 fine.99

While the FPA celebrated Tagliabue’s response to the Lions’ head coach hiring process as revealing that the “‘Rooney Rule’ ha[d] finally arrived,”100 Tagliabue’s actions sparked outrage among Rooney Rule opponents and others who felt it was excessive.101 After all, it did not appear Millen was seeking to exclude from consideration minority candidates to the benefit of a group of Caucasian candidates. He was, rather, committed to hiring a particular person—Steve Mariucci—and was uninterested in considering any other candidate, regardless of race.102 If the Rule applied in this circumstance, they argued, future decision-makers interested in a particular candidate would offer an interview to a minority candidate simply to fulfill the Rule and for no other reason.103 And, indeed, this criticism exposed an obvious potential weakness in the Rule. While the Rule requires a team to grant a minority candidate a meaningful interview, in that the Rule is incapable of directing state of mind, it cannot require that a team grant a candidate meaningful consideration. Thus, the Rule is powerless to prevent the inconsequential interview—the interview with all the trappings of meaningfulness but whose outcome is predetermined.

The Rule’s critics cited this reality as evidence the Rule would be ultimately ineffectual.104 However, many commentators believe that, more often than one might initially intuit, a face-to-face, in-person, interview with an organization’s primary decision-makers begets meaningful consideration—that sitting down together and discussing at length a common interest potentially melts away conscious or subconscious preconceptions and stereotypes that might otherwise color decision-makers’ judgments.105 As such, they argued that despite being a process-oriented rule with no hiring mandate, the Rooney Rule carried the power to markedly increase diversity among NFL head coaches.106

The proponents’ belief was borne out. Indeed, over the course of the several years following its implementation, the Rule has markedly increased diversity among NFL head coaches.107 As of the Rule’s implementation in 2002, two minorities held NFL head coaching positions.108 Four years later, during the 2006 season, minority head coaches led seven of the NFL’s thirty-two teams.109 [Ed. Note: There were six minority head coaches at the start of the 2010 season.] While this progress may not be entirely attributable to the Rule, the Rule has undoubtedly made a major impact, and at least a portion of that impact has occurred under circumstances Rooney Rule critics insisted would reveal the Rule as ineffectual—circumstances suggesting a “meaningful” interview would not spark truly meaningful consideration.

Consider the Cincinnati Bengals’ 2003 search for a head coach. Prior to that year, the Bengals had never in franchise history hired a person of color for its head coach position.110 In fact, during that period, the Bengals had never interviewed a person of color for its offensive coordinator or defensive coordinator positions, the two positions directly under the head coach in the football coaching hierarchy.111 Under the Rooney Rule, therefore, the Bengals were obligated to do something they had never done nor indicated desire in doing—they were obligated to interview a minority candidate for their head coaching vacancy. With the opportunity to convince the Bengals of his merit, an opportunity history suggests would not have arisen absent the Rooney Rule, Marvin Lewis, a renowned defensive strategist and the then Washington Redskins defensive coordinator, interviewed for the position and became the Bengals’ head coach.112 And, in the year after his hire, Lewis transformed the Bengals, who were for years the NFL’s worst team, into a playoff contender,113 a feat for which he narrowly missed receiving the NFL’s American Football Conference Coach of the Year Award.114

Although Lewis has not yet guided his team to the NFL’s Super Bowl game—in which the American Football Conference Champion plays the League’s National Football Conference Champion for the NFL title—another Rooney Rule beneficiary has. In 2004, the Chicago Bears hired Lovie Smith, formerly the St. Louis Rams’ defensive coordinator, as the Bears’ new head coach.115 Smith inherited a weak team, which had, in the previous year, won only 7 games and lost 9.116 In two seasons, however, Smith transformed the Bears’ defense into arguably the best defensive unit in the NFL, and in January of 2007, Smith led his team to a victory in the National Football Conference Championship game and to a consequent Super Bowl berth.117 The 2007 Super Bowl would prove an historic one, as Smith would join Tony Dungy, coach of the Indianapolis Colts team the Bears’ would play on Super Bowl Sunday, as the first African American head coaches in Super Bowl history.118

By his own admission, without the opportunity the Rooney Rule produced, Smith may not have ascended to the NFL head coaching ranks.119 Given an equal opportunity, however, he did so ascend and proceeded to establish himself among the NFL head coaching elite.

CONCLUSION

Five years after the Rooney Rule’s emergence, the Rule is an established feature of the National Football League’s teams’ hiring processes. Indeed, recognizing the Rule’s value, NFL teams have displayed commitment to interviewing candidates of color for their highest level front office positions despite no penalty adhering if they fail to do so.120 And, just as diversity has increased among the League’s head coaches, it has increased in the League’s teams’ front offices.121

In short, the Rooney Rule has succeeded. No team has flouted the Rule since Millen did so in 2003, the Rule has produced increased diversity throughout the League, and the Rule’s beneficiaries have met with substantial success. As such, the Rule is enjoying greater buy-in than ever before—both among those affiliated with the NFL and NFL outsiders committed to ensuring equal employment opportunity in other contexts. Most notably, in October of 2007, the NCAA’s Division I Athletic Directors’ Association, concerned that minorities are disproportionately scarce among the nation’s Division I head football coaching positions, have turned to a form of the Rooney Rule in hopes of increasing equal employment opportunity among minority head coaching candidates.122 The organization’s members have committed to including candidates of color among the interviewees for their universities’ head football coaching vacancies.123 Whether the athletic directors’ commitment will translate into greater diversity among Division I head coaches is untold, but if the NFL’s experience with the Rooney Rule is any indicator, prospects are bright.

As Cyrus Mehri and Johnnie L. Cochran, Jr. pressed the NFL to adopt the Rooney Rule, they insisted they had “provided the basis for meaningful change” and that it was the “obligation of the National Football League to see that change happen[ed].”124 They were correct, and the League has, indeed, changed. Once an embarrassment among its peer leagues regarding equal employment opportunity for minority coaches, the NFL now stands as a model for other organizations seeking the change it has enjoyed.

Notes

1. See KENNETH L. SHROPSHIRE, IN BLACK AND WHITE: RACE AND SPORTS IN AMERICA 29-31 (1996) (discussing history of discrimination in all three sports). The NHL, America’s fourth premier sports league, has had a discriminatory history as well, but in that athletes of color have historically played little hockey, discrimination in hockey has been rooted in national origin, dividing “French-Canadian and European players from their American and Anglo-Canadian counterparts.” Kenneth L. Shropshire, Minority Issues in Contemporary Sports, 15 STAN L. & POL’Y REV. 189, 191 n.9 (2004) (citing Lawrence M. Kahn, Discrimination in Professional Sports: A Survey of the Literature, 44 INDUS. & LAB. REL. REV. 395 (1991)).

2. See JOHNNIE L. COCHRAN, JR. & CYRUS MEHRI, BLACK COACHES IN THE NATIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE: SUPERIOR PERFORMANCE, INFERIOR OPPORTUNITIES 1 (2002), http://www.findjustice.com/files/Report_-_Superior_Performance_Inferior_Opportunities.pdf. (noting as of 2002, only 1.5% of the 400 coaches in NFL history were African American).

3. See Brian W. Collins, Tackling Unconscious Bias in Hiring Practices: The Plight of the Rooney Rule, 82 N.Y.U. L. REV. 870, 877-884 (2007) (discussing coaching opportunities for African Americans in the NBA and NFL); Shropshire, supra note 1, at 203-05 (noting baseball was “impetus” for diversity initiatives creating opportunities for African Americans in managerial and coaching positions).

4. Tony Dungy and Herman Edwards were the NFL’s only head coaches of color in 2002. Chris Myers, Sunday Morning QB: Black Coaches Try to Get in the Game, N.Y. DAILY NEWS, Oct. 6, 2006, at 70. Art Shell, Dennis Green, and Ray Rhodes join them as the only people of color to have held NFL head coaching positions in the League’s modern era. Id.

5. Steve Wieberg, Division I-A Tackles Minority Hiring: Unlike NFL’s Rooney Rule, ADs’ Directive Will Only Encourage, Not Require, Action, USA TODAY, Oct. 3, 2007, at 1C. Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1109176.

….

50. Johnnie L. Cochran, Jr.—Biography, available at http://www.cochranfirm.com/pdf/CochranBrochure.pdf, at 2.

51. Cyrus Mehri—Biography, available at http://www.findjustice.com/about/attorneys/mehri/.

52. COCHRAN, JR. & MEHRI, supra note 2, at i-ii.

53. Id. Exhibit B at 3.

54. See id. Exhibit B at 1 (“Find[ing] that, by any measure used, black coaches were more successful than white coaches”).

55. See id. at ii (noting wins and losses are “the currency of football and all team sports”).

56. Id. at 2.

57. See id. (recognizing a one-win difference often determines whether a team is successful in reaching the playoffs).

58. Id.

59. Id. at 3.

60. Id.

61. Id. at 4.

62. Id.

63. See id. at i-ii.

64. See id. at 8-10.

65. Id. at ii.

66. See KENNETH SHROPSHIRE, IN BLACK AND WHITE: RACE AND SPORTS IN AMERICA 10 (1996) (discussing various methods individuals use to underplay their discriminatory hiring practices).

67. Charles R. Lawrence III, The Id, the Ego, and Equal Protection: Reckoning with Unconscious Racism, 39 STAN. L. REV. 317, 323 (1987); R.A. Lenhardt, Understanding the Mark: Race, Stigma, and Equality in Context, 79 N.Y.U L. REV. 803, 829 (2004).

68. See William L. Kandel, Practicing Law Institute: Litigation and Administrative Practice Course Handbook Series, 682 PRACTICAL L. INST. 469, 483 (2006) (explaining that attacking the character of executives in negotiations as racist often hampers the ability to reach meaningful solutions).

69. See Collins, supra note 3, at 884 (noting ex-NFL commissioner Paul Tagliabue’s efforts to increase minority hiring before the Rooney Rule’s inception).

70. Id. at 886.

71. Id.

72. See COCHRAN & MEHRI, supra note 2, at 15.

73. See id. at 14.

74. See id. at 15.

75. See Collins supra note 71 at 901-04 (discussing problem of “sham” interviews with the Rooney Rule and difficulty of measuring franchises’ good faith efforts in interviewing minority candidates during hiring process).

76. See id. at 886 (noting that the NFL Committee on Workplace Diversity’s suggestions were adopted by all thirty-two NFL owners).

77. Id.

78. Greg Garber, Thanks to the Rooney Rule, Doors Opened, ESPN.COM, Feb. 9, 2007, http://sports.espn.go.com/nfl/playoffs06/news/story?id=2750645

79. See id. (discussing the effect of the Rooney Rule on the NFL).

80. E.g. Jay Nordinger, Color in Coaching, NATIONAL REVIEW, Sept. 1, 2003, available at http://www.nationalreview.com/flashback/nordlinger200504200048.asp.

81. See Collins supra note 71, at 871 (noting that the Rooney Rule appeared “vague and inefficient” at first).

82. Id. at 902.

83. In 2007, the Black Coaches Association changed its name to the Black Coaches and Administrators, and now encompasses black collegiate sports administrators as well. Erika P. Thompson, Black Coaches Association Announces Name Change, BLACK COACHES & ADMINISTRATORS, Jul. 6, 2007, http://bcasports.cstv.com/genrel/072007aaa.html. (last visited January 15, 2008).

84. See Fritz Pollard Alliance John Wooten Biography, http://www.fpal.org/wooten.php (last visited November 27, 2007) (noting Wooten’s various work as a football player and front office executive).

85. Id.

86. NFL Scouting Combine, http://www.nflcombine.net/ (last visited November 27, 2007).

87. Collins, supra note 71, at 887.

88. See Jay Paris, Browns’ Winslow is the Mouth that Roars, NORTH COUNTY TIMES, Nov. 2, 2006 (claiming that Kellen Winslow revolutionized the tight end position).

89. See NFL 1980 League Leaders, http://www.pro-football-reference.com/years/leaders1980.htm (last visited Nov. 27, 2007) (showing Winslow second in the league in receiving yards).

90. The Pro Football Hall of Fame inducted Winslow in 1995. Pro Football Hall of Fame Kellen Winslow Biography, http://www.profootballhof.com/hof/member.jsp?player_id=233 (last visited Nov. 27, 2007).

91. Winslow’s capability in this regard is perhaps best illustrated by his performance in a 1982 Chargers playoff victory over the Miami Dolphins, a performance ranking among the greatest individual performances in NFL history. See PAGE 2 STAFF, The List: Best NFL Playoff Performances, ESPN, http://espn.go.com/page2/s/list/NFLplayoffperform.html (last visited Nov. 30, 2007) (ranking Winslow’s performance the second greatest playoff performance of all time). During that game, Winslow refused to allow his team to lose. Despite being treated throughout the game for severe cramps, dehydration, a pinched nerve in his shoulder, and a gash in his lower lip requiring stitches, Winslow caught 13 passes for 166 yards, scored a touchdown, and blocked a Miami Dolphin field goal that would have given the Dolphins the victory. Dan Ralph, The Reluctant Superstar, NFL CANADA, Oct. 16, 2007, http://www.nflcanada.com/News/FeatureWriters/Ralph_Dan/2007/archive.html.

92. SHROPSHIRE, supra note 1, at xii.

93. Id. at xi.

….

95. ESPN 2002 NFL Standings, http://sports.espn.go.com/nfl/standings?season=2002&breakdown=3&split=0 (last visited November 28, 2007).

96. CBC SPORTS, Lions Hire Mariucci as Head Coach, CANADIAN BROADCASTING CENTRE, Feb. 5, 2003, http://www.cbc.ca/sports/story/2003/02/03/mariucci030203.html.

97. Collins, supra note 71, at 900-01. Ironically, Mariucci, the coach Millen pursued with such myopia, performed quite poorly as the Lions head coach. During his two-plus seasons with the team, Mariucci amassed a record of fifteen wins and twenty-eight losses and was ultimately terminated in the middle of the 2005 season. Skip Wood, After Digesting Turkey Day Debacle, Lions Fire Mariucci, USA TODAY, Nov. 28, 2005.

98. Bram A. Maravent, Is the Rooney Rule Affirmative Action?: Analyzing the NFL’s Mandate to its Clubs Regarding Coaching and Front Office Hires, 13 SPORTS LAW J. 233, 243 (2006).

99. ASSOCIATED PRESS, Millen Fined for not Interviewing Minority Candidates, ESPN, July 5, 2003, http://espn.go.com/nfl/news/2003/0725/1585560.html.

100. SPORTSLINE.COM WIRE REPORTS, Millen Fined $200K for not Interviewing Minority Candidates, CBS SPORTS, July 5, 2003, http://cbs.sportsline.com/nfl/story/6498949.

101. Curt Sylvester, Detroit Lions Owner Lashes Out at NFL in Response to Diversity Fine, DETROIT FREE PRESS, July 29, 2003.

102. Indeed, it merits noting that Millen did invite candidates of color to interview for the Lions’ head coaching position, but recognizing that Millen had already decided to hire Mariucci and that the interviews to which they were being invited would be pro forma, and thus not meaningful, none of the invitees accepted. Collins, supra note 71, at 901.

103. See id. at 902 (discussing the possibility of “sham” interviews for minority coaching candidates).

104. Nordlinger, supra note 82.

105. See SHROPSHIRE, supra note 1, at 37-38 (discussing positive effect of Carol Moseley Braun’s election to the United States Senate on the sensitivity to issues affecting minorities).

106. See COCHRAN, JR. & MEHRI, supra note 2, at 17 (noting that their proposal for changes in NFL’s hiring process had the capability to promote “meaningful change”).

107. See Collins, supra note 71, at 907-11 (discussing statistical effect of Rooney Rule).

108. Maravent, supra note 101, at 245.

109. Collins, supra note 71, at 907.

110. Geoff Hobson, The Torch Has Been Passed, CINCINNATI BENGALS, http://www.bengals.com/team/coach.asp?coach_id=7 (last visited Nov. 28, 2007).

111. Mark Curnutte, Coughlin, Lewis Come to Town, CINCINNATI ENQUIRER, Jan. 10, 2003, 1C.

112. Damon Hack, Bengals Draw Praise for Hiring of Lewis, N.Y. TIMES, Jan. 17, 2003.

113. See Jim Corbett, Lewis Confident in Untested Palmer, USA TODAY, May 29, 2004.

114. Cincinnati Bengals Marvin Lewis Biography, http://www.bengals.com/team/coach.asp?coach_id=7 (last visited November, 28. 2007).

115. ASSOCIATED PRESS, Bears Hire Smith to be Head Coach, USA TODAY, Jan. 14, 2004.

116. ESPN 2003 NFL Standings, http://sports.espn.go.com/nfl/standings?season=2003&breakdown=3&split=0.

117. John Mullin, Super Bowl Bound, CHICAGO TRIBUNE, Jan. 21, 2007, available at http://www.chicagotribune.com/sports/football/bears/cs-070121bearsgamer,0,188867.story?coll=chihomepagepromo440-fea.

118. Jarrett Bell, Coaches Chasing Super Bowl—And History, USA TODAY, Jan. 17, 2007.

119. Clifton Brown, NFL Roundup: Bears Hope Takeaways Lead Them to Title, N.Y. TIMES, Jan. 30, 2007.

120. Although the NFL has strongly encouraged its member teams to interview candidates of color for front office positions, it has stopped short of requiring such interviews. Mark Maske, Expansion of ‘Rooney Rule’ Meets Resistance, WASH. POST, Apr. 13, 2006, at D1. Indeed, the League’s commitment to the Rooney Rule and its underlying principles is so complete that the League committed to interviewing candidates of color when seeking a replacement for former League Commissioner Tagliabue. See Scott Brown, Rooney Rule Helping Minority Coaching Candidates, PITTSBURGH TRIBUNE-REVIEW, Jan. 11, 2007, http://www.pittsburghlive.com/x/pittsburghtrib/sports/steelers/s_488048.html (noting that minority candidate, Fred Nance, was among the five finalists considered to replace Tagliabue) (last visited January 15, 2008).

121. See Maske, supra note 120, at D1 (noting “the Rooney Rule, or the spirit of it, has led to more opportunities for minorities in NFL front offices”).

122. Steve Wieberg, Major-College ADs Tackle Minority Hiring, USA TODAY, Oct. 2, 2007.

123. Id.

124. COCHRAN, JR. & MEHRI, supra note 2, at 17.

OWNERS

DIVERSITY, RACISM, AND PROFESSIONAL SPORTS FRANCHISE OWNERSHIP: CHANGE MUST COME FROM WITHIN

Kenneth L. Shropshire

One possible path for decreasing actual or perceived racism against African Americans in any business setting is to increase African American ownership. The broad assumption underlying the advocacy of this remedy is that increased diversity in the ownership of an industry will decrease occurrences of discrimination.

….

II. IDEAL STATE: VALUE OF DIVERSITY IN OWNERSHIP

A. General Benefit

What would be the primary benefits of greater African American ownership in professional sports? Two of the major benefits would be (1) the social value of diversity and (2) the financial value of diversity. The social value of diversity consists of both the actual value that diversity can bring to an enterprise through the presentation of different points of view and the perceived value that diversity may have in improving the image of an almost all white ownership. The financial value of diversity includes allowing minorities access to a piece of the lucrative sports ownership pie and front office employment, expanding the individual franchise revenues by attracting more fan support and attendance from minorities, and bringing about equity in player salaries without regard to race.

[Ed. Note: The author’s discussion of the actual and perceived values of diversity is omitted.]

….

C. Ownership Glass Ceilings and Differential Racism

Glass ceilings are present in much of American society. Part of the reason for the existence of such ceilings is the discomfort that many white Americans feel with African Americans in positions of power. African Americans may not be treated dramatically differently by whites in the business setting until they seek a position of power—until they seek to break through the glass ceiling. This has been referred to as a form of “differential racism.”

….

Just as this glass ceiling, or differential racism, may be the reason for an absence of African Americans in top-level positions on the field in sports, in politics, in corporate America, and in the entertainment industry, glass ceilings that keep African Americans from acquiring ownership interests in sports franchises probably exist as well.

III. LEGAL RECOURSE: CAN THE LAW COMPEL DIVERSITY?

…. One may question whether existing law provides any possible causes of action or remedies by which to increase diversity and African American ownership of professional sports franchises. The conclusion is that present law can only play a limited role in bringing about increased African American ownership in professional sports.

[Ed. Note: The author’s discussion of affirmative action and other applicable laws is omitted.]

….

It cannot be disputed that trust and confidence among fellow owners of a sports league is desirable for the efficiency and success of the league. A bad choice can doom the partnership. There are thirty [now 32] or fewer franchises in each of the professional leagues. Consequently, individuals who enter into a partnership or who expand their partnerships are very selective of whom they permit to join, and the courts are aware of this selectivity. The necessary trust and confidence will not exist if the partnership is compelled by force of law to admit an individual whom the partnership does not want. There will just be too much bad blood and distrust. Once a legal action is brought, the possibility that the petitioner and the partners could work together harmoniously is minimal. Moreover, such legal action could jeopardize the partnership. This is why reinstatement is a disfavored remedy for high-level employees, both in the employment and partnership contexts, and why a judicial mandate of minority sports franchise ownership is even more unlikely.

Thus, antidiscrimination law provides only limited protections to minorities seeking to own professional sports franchises. Title VII does not apply directly, because there will normally not be an existing employer–employee relationship at stake, and Section 1981 only prevents owners from flagrantly discriminating on the basis of race in choosing their co-owners.

….

As it currently stands, the law is clear that the owners in a given league may sell or grant franchises to whomever they choose, and, provided nothing in their decision-making process violates any … laws …, no legal action can force the existing owners to sell to a particular group. The plaintiffs in … two cases based their actions on antitrust laws, arguing against the anti-competitive nature of a league not accepting them as franchise owners. Neither bidder was African American, and neither was successful.

In both the existing franchise purchase and expansion areas, the choice as to which potential owners to bring on board is that of the respective league owners. Just as in any other business, courts are reluctant to compel business owners to take on new partners. So long as the reason for rejection is not illegal, courts are not likely to intervene.

[Ed. Note: The author’s discussion of the impact of litigation and litigation threats is omitted.]

….

IV. WILL IT HAPPEN? NEED FOR VOLUNTARY EFFORTS

As the previous section indicates, courts are not likely to interpret existing law as a mandate to compel existing professional club owners to admit minority ownership into their league memberships without flagrant racism…. What is likely to be much more effective—at least in the short term—is increased commitment from existing owners and players to recognize the important benefits that diverse ownership in sports can bring about.

V. CONCLUSION

There are many difficulties in breaking African Americans into the ownership ranks of professional sports. The greatest obstacles are not financial but structural. The owners themselves must somehow be compelled to desire change; however, they likely suffer from the same levels of conscious and unconscious racism as the rest of society. Indeed, the issues discussed in this article are applicable to businesses beyond sports.

The key barrier to change is the legally protected club-biness of the owners. They have the nearly exclusive right to select their co-owners. There is no requirement, unless self-imposed, that the owners accept the best financial offer. As a group, the owners of any league certainly could mandate that any multiowner group seeking a franchise must include African American investors….

It will be difficult to use legal pressure to compel greater African American ownership. No current legislation on either the state or federal level regulates sports franchise ownership. Given the constitutional problems that would arise if such legislation were implemented and the recent public backlash against affirmative action in general, it does not appear that the lack of diversity in franchise ownership will be addressed by statute. In addition, although Section 1981 offers protection from flagrant discrimination, it is ineffective to put any real pressure on the owners to diversify their group.

The burden is thus on league leaders and the athletes to bring about such change.

SALARIES

THE SPORTS BUSINESS AS A LABOR MARKET LABORATORY

Lawrence M. Kahn

Among the forms of discrimination in sports, salary discrimination is the most studied issue. The typical research design—similar to much work in this area in labor economics—is a regression in which log salary is the dependent variable, and the independent variables include performance indicators, team characteristics, and market characteristics, with a dummy variable for white race. If the coefficient on the white indicator is positive and significant, then this potentially offers evidence of discrimination. Alternatively, some researchers have used separate regressions for white and nonwhite players, testing the possibility that performance is rewarded differently by race.

A major difficulty for all labor market research on discrimination is the problem of unobserved or mismeasured variables, such as the quality of schooling among workers in general. However, such problems must surely be less severe in sports than elsewhere. For example, the Baseball Encyclopedia and other baseball data sources allow one to control for very detailed performance indicators like batting average, stolen bases, home runs, career length, team success, and many more. “Occupation” in baseball is one’s position, a far more detailed indicator than, say, “machine operative.” The accuracy of the compensation data in sports, in many cases supplied by the relevant players’ union that keeps copies of the actual player contracts, is very high.

The sport where regression analyses have produced the most evidence of salary discrimination is professional basketball. In the mid-1980s, several studies found statistically significant black salary shortfalls of 11–25 percent after controlling for a variety of performance and market-related statistics (for example, Kahn and Sherer, 1988; Koch and Vander Hill, 1988; Wallace, 1988; Brown, Spiro, and Keenan, 1991).* However, by the mid-1990s, there were no longer any overall significant racial salary differentials in the NBA, holding performance constant (Hamilton, 1997; Dey, 1997; Bodvarsson and Brastow, 1998). One caveat to this finding is seen in Hamilton’s (1997) results from quantile regressions, which estimate the extent of discrimination at different points of the salary distribution, conditional on productivity. He did not find evidence of discrimination at the 10th, 25th, and 50th salary percentiles, but there was a significant white salary premium of about 20 percent, other things equal, at the 75th percentile of the salary distribution and above.†

Customer preferences may have something to do with the racial pay gap observed in basketball in the 1980s. For example, Kahn and Sherer (1988) found that, all else equal, during the 1980–86 period each white player generated 5,700 to 13,000 additional fans per year. The dollar value of this extra attendance more than made up for the white salary premium, a finding consistent with the existence of monopsony. Other researchers found a close match between the racial makeup of NBA teams in the 1980s and of the areas where they were located, again suggesting the importance of customer preferences (Brown, Spiro, and Keenan, 1991; Burdekin and Idson, 1991; Hoang and Rascher, 1999). However, by the 1990s, customer preferences for white players were less evident. Dey (1997), for example, found that all else equal, white players added a statistically insignificant 60 fans apiece per season during the 1987–93 period. This evidence is consistent with the decline in the NBA’s overall unexplained white salary premium from the 1980s to the 1990s, although Hamilton’s (1997) results suggest that it is possible that white stars add fans even if the average white player does not.

If NBA fans do have preferences for white players, having white benchwarmers may be a cheap way for teams to satisfy such demands. While early research found that white benchwarmers had longer careers than black benchwarmers (Johnson and Marple, 1973), more recent work does not find that benchwarmers are disproportionately white (Scott, Long, and Somppi, 1985).

In contrast to these findings in basketball, similar regression analyses of salaries in baseball and football have not found much evidence of racial salary discrimination against minorities. For example, in baseball, these kinds of analyses never seem to find a significantly positive salary premium for white players. Among nonpitchers, some studies actually have found significantly negative effects of being white in the late 1970s and 1980s (Christiano, 1986, 1988; Irani, 1996); however, my own reanalysis of the same data used in one of these studies found that these differentials disappeared when a longer list of productivity variables was added (Kahn, 1993). In football in 1989, Kahn (1992) found only very small salary premia (discrimination coefficients) in favor of whites of only 1–4 percent, and these differences were usually not statistically significant. However, nonwhite NFL players earned more in areas with a larger relative nonwhite population than nonwhites elsewhere, and whites earned more in more white metropolitan areas than whites elsewhere. These findings suggest the influence of customers, but they did not add up to large overall racial salary differences in the NFL.††