CHAPTER EIGHT

INTRODUCTION

In most industries, a revenue stream periodically appears that ultimately leads to a fundamental change in the way that the industry conducts its business. The sports industry is no exception. Revenue sources for sports franchises have evolved over time, with owners continuously searching for new ways to profit from their investments. In sports, the sea change was fueled by television. Sports teams found that they were able to generate significant amounts of revenue from the sale of the rights to televise their games to broadcasters. Broadcasters found that sports could attract an audience with significant buying power that was otherwise hard to reach in large numbers because of its inconsistent viewing habits—young male viewers in their 20s and 30s. This demographically strong audience was quite attractive to companies searching for an effective medium through which they could advertise their products to their intended buyers. With this demographic in place, broadcasters were able to sell advertising spots on sports programs for a higher rate than on other programs. Thus was born the symbiotic relationship between sports, television, and advertisers that endures to this day. Although the relationships among these stakeholders have become increasingly complex with the passage of time and the introduction of both new broadcasting mediums and methods of distribution, today nearly all sports’ business models include television as a main financial driver. Whether a single pay-per-view event or a multiyear broadcasting contract, few structural decisions are made without first considering the impact on broadcast revenues.

However, this was not always the case. When television emerged as a role player in sports in the 1950s, the initial concern was the negative impact broadcasting an event would have on live attendance at the gate. The logic of the owners of the day made sense. Why would fans pay to see a game in person when television would allow them to see the game for free? Those concerns were short-lived, because the experiment with television proved to be both a financial engine and a fan-base builder. Rather than causing declines in attendance, television led to the creation of new fans who ultimately attended the games. In the 1960s, television started to become the financial engine that it is today. Many of the early concerns about the effect of television on gate attendance were addressed by establishing home game local broadcast and blackout rules. With the evolution of cable, satellite, pay-per-view, and the Internet, the effect of television on the local gate has become even less of a concern to many teams. However, there is a growing concern that the home viewing experience has become so comfortable and robust that fans will increasingly choose to watch games from the convenience of their own living rooms on large flat-screen televisions rather than attend games.

Broadcasting of league games occurs at both the national and regional levels. All sports leagues collectively pool and sell their television rights on a league-wide level, with the resulting rights fee divided equally among all of the teams. These national television contracts are considered to be essential for the long-term success of a sports league, because they provide the league with the broad exposure that is necessary to build spectator interest in the sport as well as the revenues that are required for survival.

Traditionally, national television contracts have been executed with networks that are available on free television nationwide. Until the 1990s, there were only three bona fide networks in the United States; today there are five: ABC, CBS, NBC, Fox, and the relative newcomer CW. In addition to the free networks, approximately 85% of U.S. homes currently pay a monthly fee to subscribe to cable or satellite television. Technological innovations have led to the creation of hundreds of channels that are broadcast on cable television. Beginning with the advent of ESPN in 1979, a number of these cable channels broadcast sports programming, because of its aforementioned appeal. In 2009, approximately 43,700 hours of sports programming was broadcast in the United States.

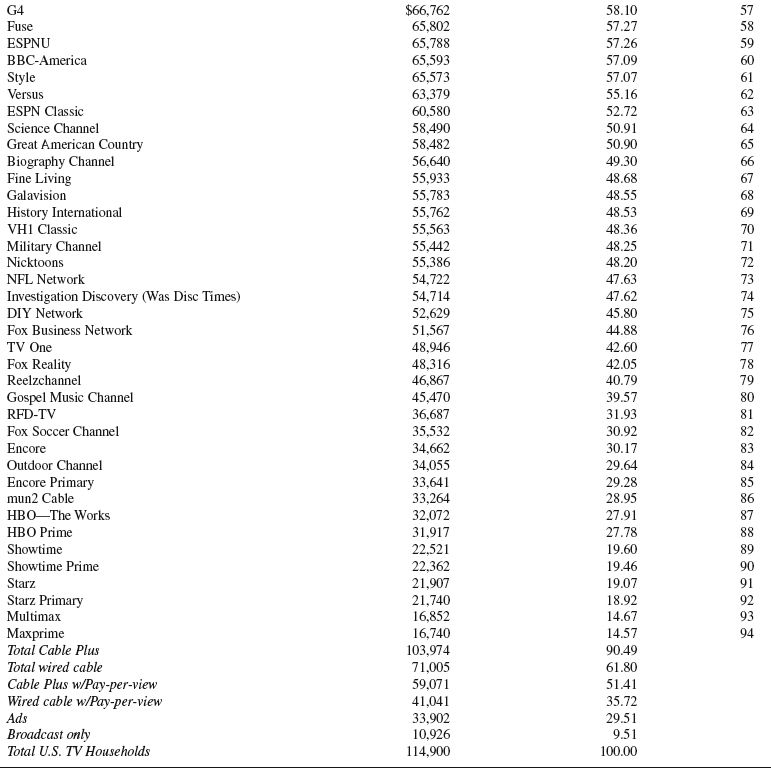

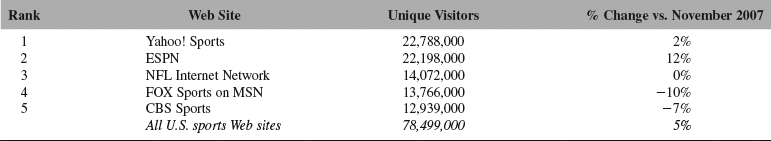

Skyrocketing rights fees have increased the threshold requirement for profitability for the networks. (See Table 1 for recent television rights deals for the major North American sports leagues and Table 2 for information on the NFL’s television rights fees from 1962–2013.) The networks need to increase their advertising revenues in order to recoup this increased investment. Because advertising rates are based on program ratings, the networks had hoped that increased ratings would lead to increased advertising dollars. However, the days of ratings increases for networks are all but over. Prime time ratings for CBS, ABC, NBC, and Fox fell a combined 29% from 1996–1997 to 2006–2007, from a combined 37 ratings points to 26.4. This drop in ratings is likely attributable to the technological innovations that have led to the development and ubiquity of the Internet and digital cable, both of which compete with broadcast networks for the individual’s attention. People—especially younger demographics—are spending more time online and less time watching television than in the past.

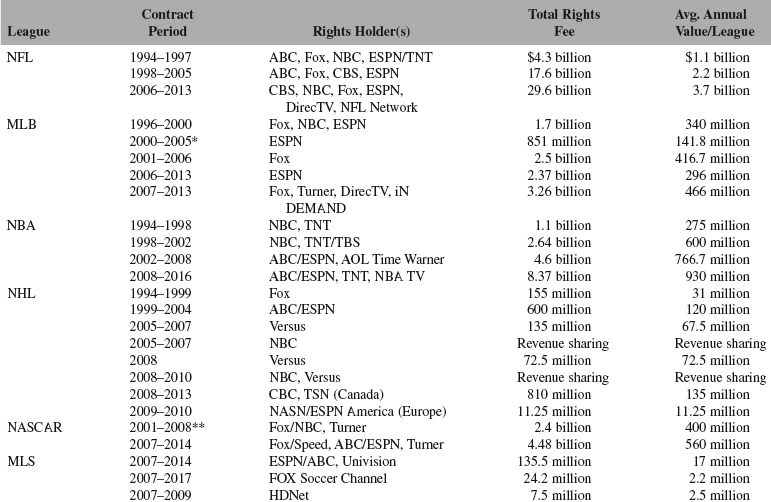

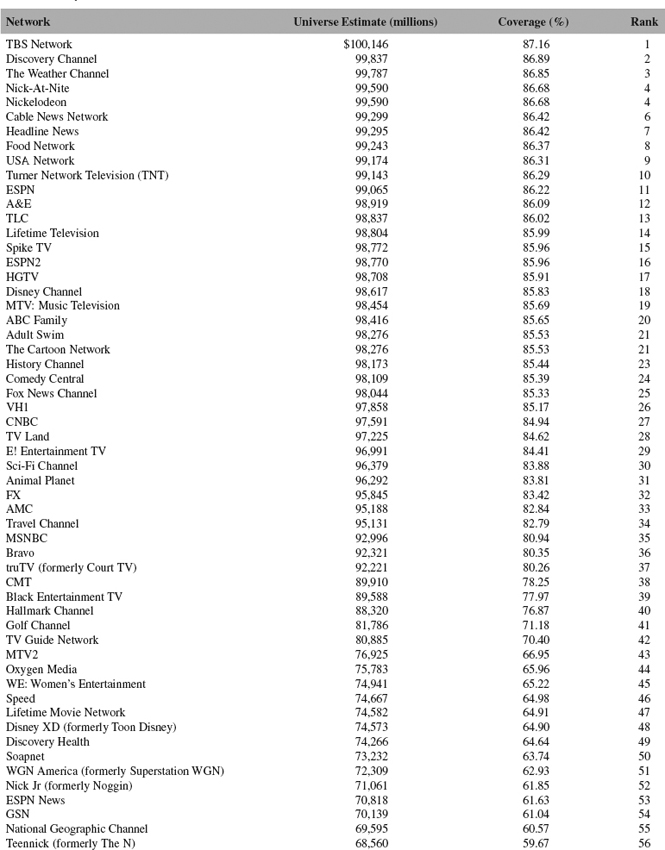

The advent of digital cable has led to a proliferation of cable networks serving a variety of general and sports-related programming niches (see Tables 3 and 4). There seems to be a channel for every interest. This proliferation of programming outlets has led to fragmentation of the viewing audience. All is not lost for sports programming, however. Fragmentation has led to the increased importance of coveted demographic groups who no longer watch any one type of programming in the same numbers as in the past—specifically the 18- to 34-year-old males that sports programming attracts.

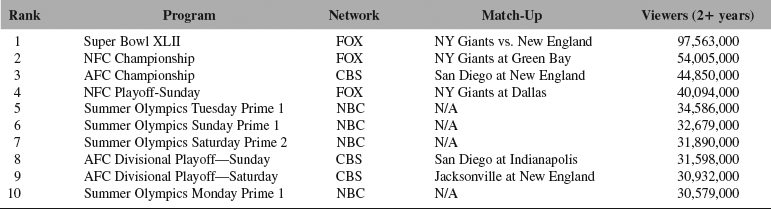

Sports ratings vary based on the teams or athletes involved, the existence of any compelling storylines, the presence of certain superstar athletes, the broadcast window in which the game is shown, the programming that airs immediately before and after an event, and the competitiveness of the event. Consider the following sporting events that occurred in 2008 (see also Table 5):

Table 1 Recent Television Rights Deals

*Terms of the deal replaced the terms of the previous MLB deal for ESPN for the 2000 season.

**Represents a 6-year, $2.4 billion deal, plus 2 additional years for Fox. Under the terms of NASCAR’s previous television contract, individual tracks made their own TV deals and Winston Cup races were spread across CBS, ABC, ESPN, TNN, TBS, and NBC for about $100 million in total rights fees paid.

Sources: Street & Smith’s SportsBusiness Journal research, Gould Media, NFLPA.

Table 2 NFL National Television Rights Fees, 1962–2013

Source: Data on file from authors.

• The most-watched Super Bowl ever was an incredibly close game between the large-market New York Giants and the New England Patriots, a team attempting to complete a perfect season.

• The most-watched cable broadcast ever was a Monday Night Football divisional rivalry game between the very popular Dallas Cowboys and the large-market Philadelphia Eagles.

• The most-watched cable golf event ever was a Monday afternoon playoff in the U.S. Open involving Tiger Woods, the transcendent athlete of his generation, competing with a severely injured knee against a journeyman golfer, Rocco Mediate, who was easy to identify with.

• The most-watched Wimbledon final in 8 years featured an amazing five-set match between the world’s two best players, Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal. Some have called it the greatest tennis match of all time.

• The most-watched NBA and NHL Finals in 5 years included a matchup between two historic rivals and leading brands, the Los Angeles Lakers and Boston Celtics, and the latter a matchup of a historically strong franchise and a team featuring young stars.

Ratings for televised sports are relatively strong in comparison to general entertainment programming. In addition, sports programming is considered to be advertising-friendly because it is “DVR proof”; that is, it is still primarily consumed in real time, unlike other programming that is increasingly being recorded and watched at a later time, with the viewer presumably skipping through the commercials instead of watching them.

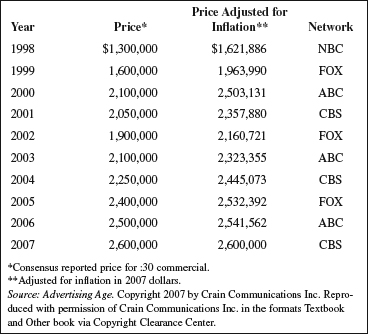

Nonetheless, networks have lost significant amounts of money on their sports programming due to the enormous rights fees that they have paid and their inability to recoup their investment through advertising sales. Morgan Stanley estimated that total losses from sports broadcasting from 2000–2006 were over $6.6 billion.1 Despite this, the networks are still interested in sports programming because of the ancillary benefits that it provides, namely, the promotional opportunities that it offers to its other, non-sports shows, and the larger branding opportunity. Leslie Moonves, the president of CBS Television, stated, “Broadcast networks must look at sports as a piece of a much larger puzzle and not focus on the specific profits and losses of sports divisions. You can’t remove sports from the other parts of the networks. If you did, it would look as bad as some others make it out to be.”2 Though the evidence of such benefits appears to be anecdotal in nature, it is driving many network decisions. The promotion of a network’s prime-time lineup during its sports programming exposes this programming to an audience that would not otherwise be as likely to be aware of it. If this increased awareness leads some of the sports audience to watch these other offerings, then the network could see a ratings increase in its other programming and allow it to reap additional advertising revenues as a result. In this way, sports could be seen as an overall ratings driver for the network. In addition, the network’s ability to promote its other programming during its sports lineup allows the network to save on the promotional budgets for this programming, because it can reduce the amount of money it spends on promoting these shows in other mediums. For example, NBC received 5 minutes of promotional opportunities during its Super Bowl broadcast in 2009. At the listed advertising rate of $3 million per 30 seconds, NBC received $30 million of free promotions for its prime-time lineup during the game. In theory, then, this allowed the network to spend considerably less in its promotion of these shows via other mediums. (See Figure 1 for a list of advertising costs for the Super Bowl.)

Table 3 Types of Sports-Related Cable Networks

Category | Networks |

General with sports programming | TNT, TBS, etc. |

General sports networks | ESPN, ESPN2, ESPN Classic, ESPN News, Versus, etc. |

Sport-specific networks | Golf Channel, Tennis Channel, Fuse, ESPN U, CBS College Sports Network (CTV), Fox Soccer Channel, etc. |

Media-owned regional sports networks (RSNs) | Fox Regional Cable Sports Nets, Comcast SportsNet (Philadelphia, Chicago, Baltimore-Washington D.C., Sacramento, etc.), Cox Channel 4 (San Diego), etc. |

Team-owned RSNs | NESN, YES, SNY, etc. |

League-owned networks | NBA TV (1999), NFL Network (2003), The MTN. (2006), Big Ten (2007), NHL Network (2007), MLB Network (2009) |

Source: Data on file from authors

Table 4 Top Cable Network Universes (12/09) (# Households)

Source: The Nielsen Company. Copyrighted information of The Nielsen Company, licensed for use herein.

Table 5 2008 Top Rated TV Sports Events

Source: The Nielsen Company. Used with permission.

Figure 1 Super Bowl Ad Rates

To a certain degree, networks are willing to view sports programming as a loss leader, because the programming also offers them significant branding opportunities. Fox established itself as a legitimate network when it acquired the broadcasting rights to the NFL and NHL in 1994. The network was able to use its acquisitions to add a number of affiliates in NFL markets that previously had balked at the opportunity to associate themselves with the fledgling network. With the leagues in tow, Fox had instant credibility. Recently, NBC has focused its efforts on key programming, such as the Summer and Winter Olympics and NFL football on Sunday evenings, and then entered into more conservative deals for Notre Dame football and an array of niche sports.

It is likely that each broadcast network will consider certain sports properties to be cornerstones of its programming lineup. They will continue to be willing to pay dramatic rights fee increases in order to retain these “tent pole” properties. However, for other sports properties, the network will take a more conservative approach and only pay rights fees that make financial sense. For example, in addition to the aforementioned approach by NBC, CBS will continue to focus its efforts on four properties—the NCAA men’s basketball tournament, SEC football, NFL football and the Masters.

Cable television is likely to increasingly dominate the national broadcasting agreements entered into by major sports properties. As leagues seek out rights fee increases, cable television networks are most able to bear the additional costs of doing so. This is a function of a cable network’s revenue model. Major cable system operators, such as Comcast, Time Warner, Cox, Charter, and Cablevision, and satellite operators, such as DirecTV and Dish Network, pay monthly per-subscriber carriage fees to cable networks for the right to distribute their channels to their customers. Thus, whereas broadcast networks receive revenues primarily from advertising, cable television networks have dual revenue streams—advertising revenue and negotiated subscriber fees. This dual-revenue stream will enable cable networks to better afford the high cost of sports programming.

In order to afford the ever-increasing rights fees sought by sports properties, sports programmers are constantly attempting to increase the subscriber fees that it receives from the cable system operator. Although typically the most expensive programming for cable system operators, sports programming is important for them because of subscriber demand for the programming and the need to differentiate themselves from their competitors, including direct-satellite subscription providers such as DirecTV. Sports programming, especially the regional sports networks that carry the majority of the home teams’ games, is must-have content for cable system operators, a fact well-known to both the cable networks and the cable system operators. Tables 6 and 7 provide monthly fees per subscriber for sports and nonsports networks, respectively.

Some cable system operators have negotiated fiercely with cable networks over proposed increases in subscriber fees. They feel that the cable networks must absorb some of the increase rather than pass all of it along to the cable system operator’s subscribers, many of whom have no interest in sports and do not want to pay higher cable bills in order to pay for the networks that carry this programming. This has led some cable systems to attempt to place many national and regional sports networks on a pay-tier where subscribers have to pay an additional monthly sum for access to the network instead of on an expanded basic cable package, where all subscribers have access to the channel. However, the sports-tier strategy has seen limited success and is unlikely to endure, especially for established national cable networks such as ESPN and TNT and more popular niche networks

Table 6 Monthly Cable Sports Networks Subscriber Fees (January 2009)

Network | Monthly Fees per Subscriber |

ESPN | $3.65 |

YES | 2.15 |

Comcast Philadelphia | 1.97 |

Comcast Mid-Atlantic | 1.95 |

NESN | 1.95 |

FOX Sports West | 1.93 |

Comcast Chicago | 1.90 |

FOX Sports Florida | 1.90 |

MSG | 1.85 |

FOX Sports New York | 1.80 |

SportsNet N.Y. | 1.80 |

FOX Sports North | 1.67 |

Big Ten Network | 1.10 |

NFL Network | 0.83 |

ESPN2 | 0.52 |

NBA TV | 0.35 |

MLB Network | 0.35 |

Versus | 0.27 |

Golf Channel | 0.25 |

NHL Network | 0.21 |

Speed | 0.19 |

ESPN Classic | 0.17 |

Source: Media Daily News and authors.

Table 7 Monthly Cable Major Nonsports Network Subscriber Fees (January 2009)

Network | Monthly Fees per Subscriber |

TNT | $0.93 |

USA | 0.52 |

CNN | 0.47 |

TBS | 0.46 |

Nickelodeon | 0.45 |

FOX News Channel | 0.42 |

FX | 0.37 |

MTV | 0.32 |

CNBC | 0.27 |

Discovery Channel | 0.26 |

Lifetime Television | 0.25 |

A&E | 0.25 |

AMC | 0.23 |

History Channel | 0.21 |

MSNBC | 0.15 |

VH1 | 0.14 |

The Weather Channel | 0.11 |

Source: Wayne Friedman, “Cable Sports Nets Pay More To Play,” February 27, 2009, Media Daily News.

Despite a difference in penetration between network and cable television of approximately 15% (representing 20 million households) as of January 2009,3 the line between the two broadcasting universes is becoming increasingly blurred. Popular cable programming garners ratings that are competitive with network shows. Cross-ownership of network and cable broadcasters, such as Disney’s ownership and shared production of ABC and ESPN and News Corporation’s ownership of Fox and Fox Sports Net, has made the distinction between cable and network even less important. Thus, cable is likely to be the new national rights model for sports programming. This is evidenced by ESPN landing the exclusive rights to the British Open beginning in 2010 and the entire slate of Bowl Championship Series games beginning in 2011, as well as CBS and Turner jointly sharing the NCAA men’s basketball tournament from 2011–2024.

Unless they see a significant increase in the amount of the retransmission fees that the broadcast networks receive from cable companies (which are analogous to the aforementioned subscriber fees), it is also fair to consider whether the broadcast network model will be able continue to compete against the cable model in landing sports properties. This raises a significant transitional issue confronting sports leagues today, as they consider whether they should move away from the original network model and to what degree. The NBA led the way in this thinking by entering into a 6-year, $4.6 billion deal with ESPN, TNT, and ABC in 2002, and continued with its current 8-year, $7.4 billion deal with the same partners. Most analysts have concluded that it is still too early to tell whether this route is more beneficial to the relevant stakeholders than the league’s single-network model, but a few differences are clear. Although there are fewer viewers, there is an opportunity for the sports property to receive an increase in its rights fees. The NBA is earning more money over the length of these agreements than in its previous broadcasting contracts with NBC and TNT, but these cable outlets only reach 85% of the households that network television reaches. The remaining 15% is problematic, in that people living in these households are unable to watch most of the league’s programming.

In addition to the league-wide national agreements in place with network and cable broadcasters and the emergence of league-owned networks in the major North American professional leagues, sports franchises in the NBA, NHL, and MLB have individual deals in place with broadcasters in their home territories. These deals can be quite important, because the vast majority of each team’s games are broadcast on this basis. (Note that in the NFL the rights to all regular and postseason games are controlled by the national broadcast partners, with only preseason games shown on a local basis.) The value of the local broadcasting agreement varies according to a number of factors, the most important being the size of the team’s market and the team’s popularity within this market. Prior to the advent of cable television, most of the local broadcasting agreements were with independent, over-the-air stations that had limited geographic reach. Cable television created the opportunity for teams to expand their presence on a more regional basis.

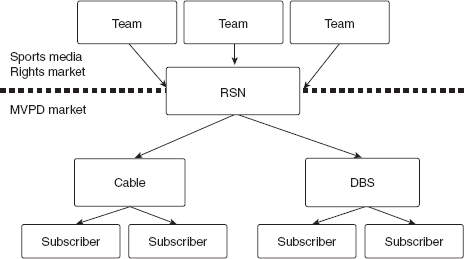

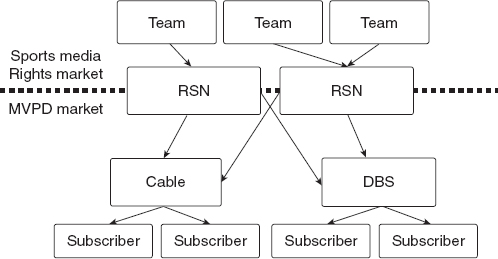

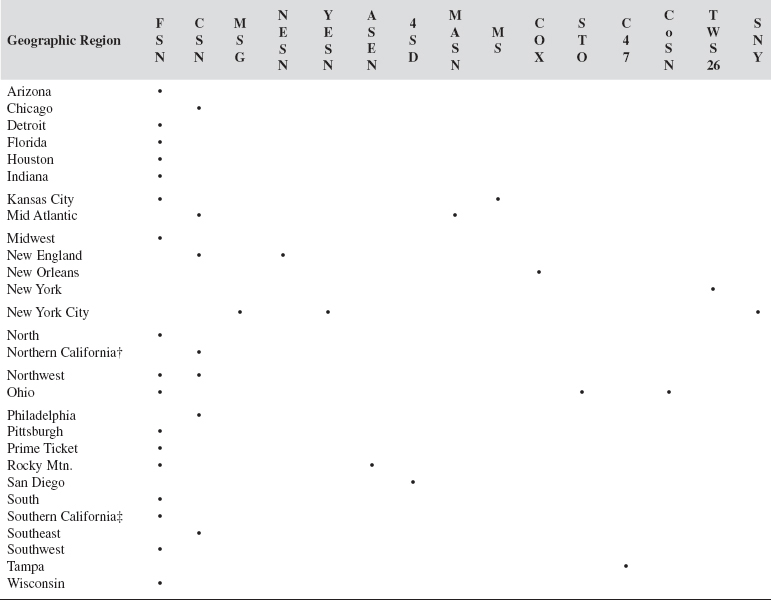

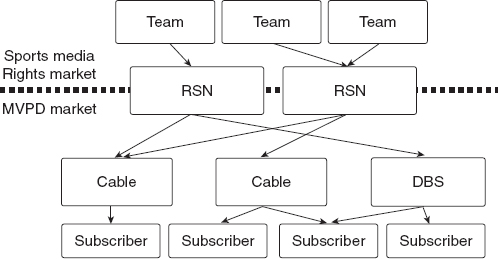

The aforementioned proliferation of cable networks included a number of distinct regional sports networks (RSNs) whose programming was built around the home teams. Ultimately, there was a consolidation of many of these RSNs, and Fox Sports Net emerged as the dominant player in the marketplace with its ownership of 19 RSNs nationwide and an affiliation with 5 others. The majority of NBA, NHL, and MLB teams are broadcast partners with Fox Sports Net. Comcast has emerged as another major participant in RSNs, with a hand in 11 of the networks across the country. The ratings for sports programming on RSNs are still strong, reflecting fans’ continued interest in their home teams. RSNs capitalize on the much greater appetite that local fans have for their teams than a national audience would have. Recognizing an opportunity to exploit its revenue potential, cable system operators, media companies, individual teams, and leagues have started their own RSNs. In addition, a number of niche channels focusing on a single sport such as soccer, tennis, golf, action sports, auto racing, skiing, and nonrevenue college sports have been launched.

While the programming content on the RSN must be attractive to viewers, the distribution of the RSN to a large number of subscribers at an appropriate monthly subscriber fee is a key to its success. Enough people must have access to the channel for the advertising rates and subscription fees to sustain the RSN. Thus, it is vital for the RSN to be carried by a large number of cable systems in the local market. Without sufficient carriage, the RSN will fail. In addition, the RSN must have sufficient financing to support the substantial startup costs and initial operating losses, as well as an experienced management team that has the ability to negotiate the aforementioned affiliate agreements and rights fee deals.

The RSN concept is still evolving, and thus far has been met with varying degrees of success across the country. It clearly has not been the answer for every team. The Portland Trail Blazers, Charlotte Bobcats, and Minnesota Twins all unsuccessfully attempted to launch a RSN. Notably, Trail Blazers owner and Microsoft cofounder Paul Allen’s Action Sports Network lost a reported $25 million when the RSN failed after it could not get sufficient distribution in the Pacific Northwest. Then-Charlotte Bobcats owner and BET founder Bob Johnson’s Carolina Sports Entertainment Television (C-SET) shuttered after only one season, because its distribution deals left most of the team’s home market without the network. These failures embody the significant risk that teams face when attempting to launch an RSN. Although the potential payoff to sports teams that own their own RSN is huge, it is very difficult to successfully launch an RSN. Carriage and distribution are difficult obstacles to overcome, especially for sports teams that are newcomers to this aspect of the television business. Even Disney was unsuccessful in its attempt to launch ESPNWest, a proposed RSN that would have carried the games of both the Disney-owned Anaheim Angels and Mighty Ducks. This should send a cautionary note to any team attempting to launch its own RSN. It may be that the team is better off using the possibility of starting its own RSN as leverage in negotiating new rights fees deals with the already existing local RSN.

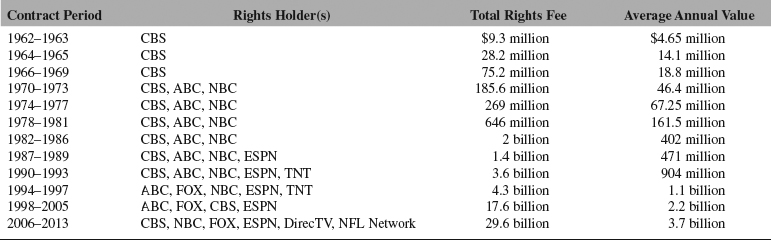

The discussion of media now transcends television and must include the multiplatform world of broadcast, cable, broadband, mobile, online, and print outlets. In October 2008 alone, 75 million people visited sports Web sites. (See Table 8 for the top five U.S. sports Web sites.) Similar to what has transpired with the advent of “disruptive” technologies such as radio, over-the-air television, and cable and satellite television in previous eras, the creation and continued expansion of the digital world has provided the sports industry with a vibrant revenue opportunity. Sports programming is highly valuable content in the digital world as well, as sports fans clamor for more information and interaction with their favorite athletes, teams and leagues. Internet use continues to increase; according to U.S. Census data from 2007, over 60% of U.S. households have broadband access. Mobile phones are nearing ubiquity—nearly 85% of U.S. households have them, and a growing number of people are living in wireless-only homes.

Source: The Nielsen Company. Used with permission.

Although the business model continues to evolve, sports properties have thus far monetized the digital world via two somewhat distinct strategies: a subscription-based model where individuals pay a fee to view the content and an advertising-supported model where the viewership is free and advertising is sold on the site. Although each strategy has its advocates, it is likely that content that appeals to a smaller but dedicated core audience is better suited for a subscription-based model; the advertising dollars that the content can generate is relatively small due to the limited number of unique visitors to the site, but the fan base’s loyalty is high enough that it will be willing to pay to view the content. An example of this is the ATP World Tour and Sony Ericsson WTA Tour’s streaming of 37 of its 2009 tournaments via TennisTV.com, the official video Web site of each tour. Individuals could subscribe to a variety of packages ranging in price from $130 for annual access to $20 for a single tournament. At the league level, the NBA, NHL, and MLB offer their subscription-based out-of-market packages via broadband as well as on television.

An advertising-supported model works best for content that is attractive to a mass audience; here the audience size is large enough to command significant advertising fees. The most successful example of this model to-date has been CBSSports.com’s March Madness on Demand (MMOD) product, the online streaming video of the NCAA Division I Men’s basketball tournament. MMOD operated on a subscription basis, costing an average of $15 from its launch in 2003 through 2005, when approximately 20,000 users bought it. It converted to a free, advertising-supported model in 2006, and over 1.3 million viewed it; this model endures and the product has seen tremendous growth. The 63-game event drew over 7.5 million unique visitors to the MMOD video player in 2009 (58% higher than in 2008), with 8.6 million total hours watched (a 75% increase from 2008).4 In 2009, CBSSports.com generated over $30 million in advertising revenues from MMOD. Other examples of successful live-streaming on a free, ad-supported basis include CBSSports.com’s showing of the 2008 U.S. Open men’s tennis final between Roger Federer and Andy Murray, which reached 300,000 unique visitors who watched a combined 243,000 hours (an average of 49 minutes per user), and NBCOlympics.com’s live-streaming of 2,000 hours during the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Although the technology exists to allow teams to stream their games live in their home territories, in-market streaming has a number of operational and financial obstacles that must be overcome. However, the revenue potential of in-market streaming to mobile devices makes it inevitable; there is simply too much money to be made for a reasonable solution not to appear.

In 2009, MLBAM, the digital arm of MLB and a long-time leader in the digital space, began offering a mobile version of its MLB.TV Premium subscription-based outof-market broadband video package to subscribers of its $9.99 MLB.com at Bat application on the iPhone and iPod Touch. It is likely that the other leagues will follow in due course, giving fans near-constant access to their favorite sports, teams, and athletes. Today’s blogs, message boards, and social networking applications enable sports properties to deepen their relationship with their fans. Tomorrow’s technologies will allow for even more of the same. Although exactly how sports and digital media will intersect going forward is unknown, the passion and loyalty of sports fans and their seemingly insatiable appetite for content related to the object of these desires should allow the industry to monetize this opportunity.

In the first article, “Panel I: The Future of Sports Television,” a panel of sports experts discuss the future of sports television in a wide-ranging conversation, providing a good starting point for the analysis that follows. In the second selection, John Fortunato examines the business of one league’s television programming—the highly rated NFL. Although ratings for NHL programming are low in the United States, hockey games are quite popular among Canadian television viewers, a topic that is examined by O’Reilly and Rahinel in the third selection. In the fourth selection, Diana Moss details the business of RSNs.

Sports properties have exerted considerable efforts to find other revenue streams beyond television. The “new media” certainly encompasses analog and digital cable, satellite, high definition television (HDTV), and other broadcast vehicles. The largest focus in this new media realm, however, has been the Internet. There is not a sector in the sports business that has not dabbled in some way in cyberspace seeking to find a way to add the Internet to its business model. Thus, the chapter concludes with predictions about the future of sports media in an article by Rein, Kotler and Shields.

Notes

1. Andy Bernstein, “Moonves: Sports Worth More Than Money,” The Sports Business Journal, March 17, 2003.

2. Alan Miles, “Digital TV Transition: 2009,” Barclays Capital Equity Research, December 12, 2008.

3. Richard K. Miller and Associates, “Sports Television Broadcasting,” The 2006 Sports Business Marketing Research Yearbook, July 2005.

4. “Final 2009 NCAA March Madness On Demand Traffic Figures Show All-Time Record,” April 10, 2009. Available at: http://www.reuters.com/article/pressRelease/idUS92989+10-Apr-2009+PRN20090410.

OVERVIEW

PANEL I: THE FUTURE OF SPORTS TELEVISION

Ronald A. Cass, Mark Abbott, Irwin Kishner, Brad Ruskin, and Alan Vickery

MR. ABBOTT: … I wanted to speak this morning a little bit about the impact that new technologies have had on the television business for sports…. Most of what I will talk about are things that I have had direct experience with in the last twelve months….

To de-glamorize sports, which has to be done sometimes, it’s about the basic allocation of rights. When you take a look at what we as lawyers in the sports business do, it is often refereeing the fights over how those rights have been allocated. Whether it’s an issue between a league and a team over an allocation of a right or between various broadcast partners, a lot of what we have to do is think through how we want to allocate those rights which we have to maximize the overall value for our sports league. We’ll talk about that in a moment.

But I wanted to talk, first, about the impact that several new technologies have had on the sports business. I think everybody is generally aware… of the great move away from the three broadcast networks to cable and to satellite television and all that that entails.3

I think there are really four trends that I’ve seen, and that we’ve all seen in the last couple of years, that have really come to the forefront and dramatically changed the business, more so than the previous twenty years had done so.

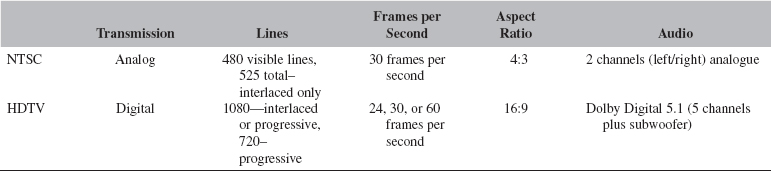

The first is the growth of digital television. Digital television (“DTV”), if you’re not familiar, is the digital transmission rather than through analog. This is done through either a satellite, like DirecTV or Dish Network, or now digital cable which is starting to roll out across the country.4

There is no more room for analog channels…. The bandwidth is already used up.5 And so any new channels that you see are digital. That means they can only be broadcast over satellite or broadcast in an area that has digital cable.

This has presented a great opportunity but also a limitation. The new niche channels that you see rising up that people are talking about—NBA TV,6 or the National Football League (“NFL”) … channel7—they rely upon the rollout of this digital platform.

It has gone a little bit slower than people had anticipated that it might go. It really relies upon cable systems adopting the digital platform for its distribution in order to get your channel distribution.8 So a lot of these channels have an opportunity to be distributed because there is now bandwidth….

That presents a lot of opportunities for sports leagues. We see it really in two ways that I think have already been alluded to. The first is the single-sports channels which have come up. The second is something which is very popular—what are called out-of-market packages.9 We have one called MLS Shootout. NFL Sunday Ticket and Major League Baseball Extra Innings are the types of packages that we are talking about,10 which have become very popular as a result of satellite.

It’s a way for a league and teams to more directly connect with its fans all throughout the country, because no longer do you need to have just a national broadcast to reach everybody. If somebody is willing to pay the fees, which are relatively modest actually, to get one of these packages, you can have access to all the games from all the local markets. That is quite a lot of benefit to the fans and it is a great opportunity for professional sports leagues.

The second trend that is really starting to hit right now is high-definition television (“HD” or “HDTV”).11 There has been a lot of talk about high-definition television over the last few years and there has been a lot of talk about the requirements of broadcasters to broadcast in high-definition, but it is really starting to break out now.12 That is driven by a few things.

One is the development of more content being broadcast in high-definition, which is causing more people to buy high-definition television. High-definition televisions are coming down lower in price.

….

The third trend in technology that is impacting all of television but is a benefit for sports is TiVo and digital video recorders.16 I think you’re probably all familiar with what TiVo is. Basically it’s a hard drive that allows you to simply record things off of television. It’s much easier to use than a VCR. It’s much higher quality. It allows you to very quickly fast-forward through commercials.17

….

People in the sports business tend to think that of all broadcast properties, sports is among the most TiVo-proof, and that is because you incorporate with more frequency now broadcast sponsorship and commercial elements within the game itself. So, the classic example is on the sidelines of an NFL game you will see the Gatorade container or the Motorola headset. That is not just there because the team chose they like Motorola. It is there because Motorola paid millions and millions of dollars for that to get that exposure.20 And you cannot TiVo through that. It is on. When they shoot the coach, you are not TiVo’ing through that. And so TiVo presents sports a really unique opportunity to offer advertisers a way to reach fans that they cannot avoid. I think that is a very important trend and very important for the value of sports broadcast rights going forward.

The fourth trend, which has been going on for a long time—in fact, it had both a boom and bust in the last five years—is obviously new media, and that’s the Internet.

….

No one doubts that the Internet is a transformational medium. I saw a very interesting article the other day that compared it to the airline industry, the point of which was that both the airline industry and the Internet have done more to transform the economy than any other industries. That is, by virtue of being able to fly around the country, it has grown our economy, and the Internet allows communication to happen much quicker and access information much quicker. And so it has transformed the economy in very profound ways, yet you cannot make money at either of them.

I think that is one of the debates that is going on in the Internet. There are those who come to speak to sports professionals and say that the economic model is no different than that of the public library; it is just an information access device. I think most people in the sports business vehemently disagree with that and feel that the Internet is a way to more closely connect your product with the fan. It is all about providing the fan access to information that they want in a way that they want to receive it, and people are starting to find ways to monetize that.

When there was a lot of crazy money and it reached a fever pitch, just as the NASDAQ reached a fever pitch in March of 2000,21 people had raised money from the public markets and the capital markets and were throwing a lot of money at sports rights because, just as sports rights had been used, for example, in Europe by satellite providers to reach homes and to get subscribers, and just as it had been used here by cable companies to get subscribers, the Internet companies were going to use sports content to get eyeballs. The problem was nobody figured out how to monetize those eyeballs once they had them.

There is now a move to subscription-based services, and you will see a lot of this coming. It has happened already, and it is going to come even more this year. People have found that a model that works reasonably well on the Internet is to offer fans—for $9.95 a month—the ability, for example, in baseball to get all the audio broadcasts of all the games nationwide, or to get a package of highlights customized for the teams that you want.22

So, I think the story is still not told entirely on where the Internet is going exactly with respect to sports, but there is no question that it is transformational and that sports leagues are all grappling with the best way to deal with it. I think that you are going to see the fan benefit from that as there are going to be more opportunities to follow your favorite team and learn more about it.

That is a brief overview of the impact that technology has. There is a lot more to say about that, but those are the trends that I think are the most currently being discussed in sports leagues and sports teams.

….

MR. KISHNER: …. Today I am going to talk about the future of sports television and the emergence of what I term the vertically integrated model, or the regional sports network as it has been called in the press in recent days.26

I am going to start off by just giving you a background of what the TV/media rights world looks like today, talk about some of the components that go into it and some of the considerations of forming and organizing a vertically integrated network, and where I see it in the future emerging and in which particular markets.

Television programming of sports events has increased tremendously, almost geometrically, from decade to decade. From 1980 to 1990 television and cable networks went from an average of approximately 4,600 hours of programming to 7,500 hours of sports broadcasting, and from 1990 to 2000 that 7,500 hours increased to over 14,000 hours of sports broadcasts.27

The big four broadcasting networks spend over a billion dollars each on sports programming annually. Gross revenues generated by professional and collegiate athletic contests amounted to a $194 billion business in 2001.28 So clearly there is a tremendous amount of money here, a tremendous amount of value here.

What the regional sports network, with a vertically integrated model, does is it takes one plus one. In other words, combining a sporting event with those broadcasting rights, thereby equaling a greater synergy, greater than one plus one.

The revenue stream from a media contract is one of the primary assets of any sports franchise. It is the means by which a team is able to put product on the field. For example—and I will get to this later—when the Texas Rangers were able to pay $25 million per year for Alex Rodriguez, or $250 million,29 the reason by which that contract was able to be generated was as a result of Tom Hicks and his creating this regional sports network which was ultimately sold to Fox Sports Net for $500 million,30 but the point being that this is a tremendous creation of value.

As an aside, while the TV contract is primarily the main generator of revenue for the team, there are other forms of media which also generate revenue, not the least of which is the radio contract. On the TV contract you are talking in the $50-million-plus area on the high side, to—well, for the Expos it was just under a million. But on the radio side you are talking, call it $8, $9, or $10 million a year potentially for the rights.31

In forming these vertically integrated models, one of the considerations that you need to take into account are the league rules, because ultimately every league has a different set of rules which you need to navigate through.32 Ultimately, these deals all need to be blessed by the league and you need to know what the discrepancies are.

Just to cull out one or two of these, there are territorial restrictions. For example, in the National Basketball Association you have the concept of an inner market where each team has by right an ability to broadcast its signal, and you have an external market which you can buy.33 Actually, by paying to the NBA money, you can broadcast your signal to what is called the outer market.34

There are differences in the leagues between a television market and a radio market. Indeed, in Major League Baseball, just to point out one of the anomalies, every TV deal has to have a provision in it which states that if the broadcast signal is put out to in excess of 200,000 households outside of your territory, then you can terminate that contract as a matter of right, if directed by the commissioner.35 So that is just one of the considerations.

Another consideration is that each league has its own national rights agreement with TV producers, TV companies, and almost always the national rights agreement will preempt the local rights agreement.36 This is one form, in my opinion, of revenue-sharing. I mean, here you have a league that is taking broadcast opportunity from the individual teams and packaging that. But that is another consideration.

Lastly, one of the major considerations, as Mark had alluded to earlier, is the effect of the Internet on all this. As of today, it still has not been a major issue, but clearly as time evolves, that is something that we are going to need to consider.

The new vertically integrated model can be said to have its basis in other derivative models. What I mean by that is there are definitely vertically integrated media companies today. For example, Cablevision owns the Knicks and the Rangers … and there are a couple of other examples.

Actually, you could trace the roots of the vertically integrated model back to CBS, with its purchase of the New York Yankees in the 1960s, although that did not work out too well for CBS at the time….

But in any event, all these models were based on existing media companies trying to find new product to put on the airwaves. The vertically integrated model is different, because here it is ownership of the sports team, either by itself or in alliance with others, creating this new company, if you will, and by doing so creating additional revenue streams as well as creating enhanced value for the company and the franchise—enhanced value, in the sense that for the franchise, because you now have a combined company which, in theory at least, will expand the universe of potential buyers for that product.

Attempts to execute this strategy have met with a fair degree of success. Sometimes it has failed, but most of the models that I have been seeing really have been fairly successful.

As I alluded to earlier, Tom Hicks, the owner of the Dallas Stars and the Texas Rangers, was planning to start a competitive sports network.42 After doing the initial leg-work, he sold the rights for that network for $500 million.43 Again, he created much more value than he would have had through the traditional means.

Paul Allen, the chairman of Charter Communications, created a regional sports network built around his team, the Portland Trail Blazers.44 Although that effort ultimately failed, in the end, I believe, he garnered more dollars for his team or for himself than he would have normally.

Also, another good example is the recent sale of the Boston Red Sox, in which an ownership group led by John Henry purchased the Red Sox for $700 million.45 The reason why that deal was so highly valued was that as part of that deal, the team’s stake in the New England Sports Network was included.46 That $700 million valuation for the sale of the Red Sox shattered the previously high sale of the Cleveland Indians, which was $323 million.47

In forming a regional sports network or this vertically integrated model, there are seven major components that everybody needs to consider before you can even begin to undertake the analysis. I just want to hit those before going into what I see as the future of this.

First off, you need year-round programming, or at least marquee programming. That marquee programming is obviously found by the sporting broadcast of the team or teams that you are going to have the rights to. Therefore, if you want year-round programming, you will need to combine baseball and basketball, or baseball and hockey.

Another component is you need filler programming: historical interest stories or human interest stories. You can accomplish this by purchasing a library of rights from others.

Another factor: you need the correct demographics. You need to have the people who can pay and a sufficient population base to support the emergence of the network.

You need the proper economics…. That turns out to be based on whether YES should be carried as a basic package product or a premium package product.48 That translates into the revenue stream that ultimately winds up into the network.

You need to have financing lined up because the startup costs here are fairly substantial, and to weather the storm through that start-up it is very advisable to have financing in place.

Solid management. You need to have a management team that is able to cut your affiliation agreements in such a way as to know what the market is, what the rights fee should be, etc.

Another very key element in the emergence of these regional sports networks (“RSNs”) or the vertically integrated model is that the existing media deal for these teams needs to be expiring or about to expire, because otherwise there are no rights which you can sell.

….

The bottom line on all this is that this model has many uses way beyond just big-market teams. Indeed, I foresee in the not-too-distant future the emergence of specialty sports networks beyond just the major four leagues. For example, NASCAR racing would be ripe for forming a network; championship wrestling; Major League Soccer—all these arenas are ripe for the emergence of this new model.

….

MR. RUSKIN: … The two themes that I want to touch upon today are: (1) the special strength and value that sports has, and will continue to have, in the television marketplace; and (2) the extent of migration of sports to various non-broadcast options.

Now, on the one hand… sports faces tremendous challenges in the marketplace today. There is certainly a level of pressure on rights fees, on what broadcasters will commit in the first instance to leagues, that I think is greater than it has been probably at any other time over the past decade. There is certainly among telecasters an increasing desire for low-cost programming. The advertising market is extremely tight, and has been tight for a period of time.

And the market is plagued by, or at least marked by, fragmentation—fragmentation meaning the ever-increasing number of broadcast outlets, of channels—which has the effect of each individual channel being less significant in the marketplace. Now, that trend has been ongoing for many years, but the trend when one looks at it today leads, across all television programming, to ratings for any type of television program that are markedly less than ratings for similar programs five year ago, certainly ten years ago or twenty years ago.

All that said, sports remain special, and they remain special in the marketplace for a number of reasons. The first really goes to the very special nature of sports. What many telecasters are looking for is destination viewing, a common term today. They want programming that viewers will want to make an appointment to see. I think NBC called it “appointment television,” the first one to coin it.56 They want programming that viewers are going to see as somehow special, necessary, and that they will actually at ten o’clock want to be in front of their television set.

Mark mentioned before that sports is viewed as either TiVo-proof or more TiVo-proof than most other forms of content. That is true. He explained one of those reasons, which is the ability to continue to provide advertiser or sponsor message during the content of the sport, be it on ice, be it through showing signage, be it through other forms that he described.57

The other reason that it is TiVo-proof, or somewhat TiVo-proof, is that people care about seeing the event live. One of the joys of sports is that you do not know what the outcome is going to be and you want to watch it when you still do not know what the outcome is going to be… But nevertheless, and for the joys of ESPN Classic,58 the fact is sports has that. Very little else does.

I would have said nothing else does. But, interestingly, I think that one of the things that now does is reality television. On the one hand, it is the telecaster’s dream because it is low-cost programming….

But it also has the element that people want to see it live. You know, when they’re in the office at the water fountain the next day…

And so reality television has some of those elements. In fact, as you can see, it has been, and is continuing to be, dominant in the television landscape, and certainly in the over-the-air broadcast landscape.60 That said, sports is still the dominant flow of content that has that special quality and that allows it to be of great interest to telecasters.

Sports also has a different element, and I think it is an element that is sort of interesting as we face a time of possible war and other things that we face in our lives. Sports creates, probably as much as anything, the ability for a shared common experience. The fact is that sports allows us to connect with people whom we do not otherwise know. I mean, how quickly when one is abroad and meets another American does your conversation somewhere along the way turn to sports as an immediate bond that you know things and your life has been touched in a similar way? I think that shared common experience, for obvious reasons, is always important but becomes ever more important.

It is also why—and I will come to this in a moment—certain big events will always remain on broadcast network, events like the Super Bowl, because those events have an ability to reach a number of people that few things do. That experience remains important, I think, as part of, the American psyche if you will.

So for all those reasons sports have a lot of very special qualities.

You can look at how important sports is, how important it is to television, through many prisms. Looking at ESPN and its growth is extremely telling.61 As a few people have mentioned, there is a great proliferation of various networks on cable television today. But if you were to ask a question to a cable operator: “You only get one, you only get to pick one network; what’s the most important network that you must have?” The answer invariably is ESPN. Not surprisingly, this is why ESPN is able to charge more per subscriber than any other national or cable network.62 But the fact is it is ESPN that stands tallest among all of the various cable networks.

….

With respect to ratings, while it is true that ratings have moved down across programming, I think it is probably also so that they have gone down less across sports programming than many other forms of programming. I think in the sports world there is a lot of wringing of the hands: “How can it be Major League Baseball used to get a sixteen and now it’s getting a four or a five?”64 You can look at it in a lot of different areas and a lot of different sports. But the fact is “All in the Family” used to get a twenty-seven;65 today the leading shows are getting approximately half that.66 It is all the way across television programming that the fragmentation has had its impact.

But sports stays strong, amid many of those decreasing effects. And, if you were to look from 1980 to 1990, it was true that for virtually every sport, there was a significant decrease in its average rating of any of its events, across regular season or across average playoffs, that was market.67 If you look over the last three or four years, it is much more of an up and down.68 There has been some flattening out there, and for many of the sports they have been increased on a year-to-year basis. It is really more sport-to-sport and the particular match-ups that they might have over the course of a period of time.

The other thing that makes sports special is technology. Mark was addressing some of the aspects of technology and some of the trends.69 But what is interesting is the extent to which sports is such a leader in the development of technology as it affects the broader viewing experience.

Again, anyone who watches sports can think among the things that you have seen that have enhanced your viewing experience… And we quickly go from being amazed by it to it being an essential part of our viewing.

It was less than ten years ago that Fox created the Fox Box, which in the upper-left-hand corner told you the score and told you how much time was left.71 It seems like such an essential element of your viewing; it’s almost annoying if it isn’t there and you tune in and you want the information. Again, a technology developed through sports.

….

You know, think about it. At what other forms of television do you see that level of technology? If you think about sitcoms or dramas, they increase in certain ways, but they do not bring technology to us in those ways to enhance the experience.

I think HDTV will do more of that. It is really a form of distribution. As Mark said, there are real questions as to where the money gets made. Other than that, it will become an essential way of viewing. And for many sports, the promise of HDTV, both because of its clearer picture and also because of the shape that it will bring you, is viewed as a wonderful promise. Hockey, for example, suffers on television because the shape of the rink is different than the shape of your television set. The ability to expand that, to be able to see a greater amount of action, and to be able to see plays forming should be wonderful to the viewing experience. And again, for all those reasons television is special and sports is special on television.

Interactivity is another area. Again, it is difficult to know all the ways in which the Internet will emerge and evolve, but what is certain is that it provides additional opportunities for information exchange, which is a part of sports that brings the fan and the viewer closer to the sport—whether or not people will be watching streaming video in their office, whether or not it is an ability for them to exchange information with people while they are watching something to call the play, try to make decisions, or create their own camera angles in the way that they want to see it….

The other thing I wanted to touch upon is the area of migration. This is a 1994 report by the Federal Communications Commission (“FCC”), a decade ago, commissioned by Congress in 1992, titled “The Inquiry into Sports Programming Migration.”75 Interestingly, as part of the 1992 Cable Act,76 Congress instructed the FCC to conduct an examination of the carriage of local, national, and regional sports programming by broadcast stations, by cable programmers, and what they described as pay-per-view services, and at that time to analyze the economic causes and the economic and social consequences of migration trends, and to submit legislative or regulatory recommendations.77

They defined sports programming migration as “the movement of sports programming from broadcast television to a subscription medium (i.e., one for which viewers pay a fee).”78 They looked at the period from 1980 through 1994. They concluded at that time, interestingly, that there had not been significant migration of sports programming from broadcast to subscription television. Now, there are a number of things that I find interesting in this.

The first thing that is interesting is the very fact that Congress would commission such a study. It really highlights the uniqueness of sports and how we look at sports in our life.

….

Sports is different in that way. The fact is that with respect to migration, there has been an evolution, not a revolution, but it shows the power of evolution, because the fact is, what was unthinkable not that long ago is now commonplace. The fact is that when one looks at the cable and satellite landscape today, it dominates the sports world. It is really only the NFL that is able to make broadcast television its primary method of distribution.79 As to each of the other major sports and as to every other sport, cable and satellite is their major mode of distribution, and that means playoff games—something that would have been unthinkable at one point in time.80 And again, that has happened as cable TV has grown, and it has become really a part of our life in most every way.

The effect of that, I think, has been, on balance, wonderful for the fan, because at the end of the day it has created more opportunity for viewing, it has created the kind of packages that leagues have created, some of which Mark referred to—the satellite packages, or those available on cable through on-demand, and allow super-fans to obtain as many games or obtain every game, if that is what they want. It allows other fans to have all kinds of viewing available to them on cable, and the like.81

The ultimate point, the reason that this has happened is that cable creates a dual-income stream, and that dual-income stream—the ability to get money both through advertising and through subscriber bases—is what is attractive and what allows leagues and property owners to ultimately get the value to which they are entitled out of the rights of their product.

So, all that said, the bottom line is sports remains strong, sports remains attractive, and it will continue to exist in a highly competitive world, but sports will continue to be critical to the future of television.

….

MR. VICKERY: …. There are two points that I want to address today…. One is the whole question of the struggle between vertically integrated cable companies and sports teams for the ownership and the right to exploit the television rights that go with putting on a sports event. The other issue is the future of sports broadcasting in what is called advanced basic, or expanded basic, compared to paying a separate premium price for sports on a tier.83

Let me start, first, with the question of the struggle over the right to control. The way in which … sports broadcasting has worked in recent years is through vertical integration between the ownership of the teams and the broadcasting of the games to the media. There are really three levels of integration, and he touched on all three: one is the actual ownership of the team that puts on the event; the second is the ownership of the network that programs and packages the sporting events; and then the third level of integration is the distribution, either over-the-air, traditional broadcasting, or through cable distribution, or now through satellite distribution.84 And I suppose the Internet is yet an additional one, although that has not caught on as much thus far.

The Cablevision model … is one in which, at least a number of years ago, Cablevision controlled the distribution to a very large segment of the New York area through its ownership of cable companies. And it integrated into the programming level through Madison Square Garden and Fox Sports New York, in effect, to ensure a supply of programming for its cable distribution.85 That is particularly important to a cable company, or at least the FCC concluded a number of years ago in its report on the cable industry that sports programming is deemed critical to the success of a cable company in a particular area.86 Now, that may be a question that is, at least with respect to regional or local sports, up in the air at this juncture, but that is the traditional wisdom.

Cablevision then took it a step further by integrating all the way to the team level, so that by acquiring Madison Square Garden LP, it acquired the Knicks and the Rangers as well as the forum in which they put on the games.87 So they were integrated at all levels. And for a time, Madison Square Garden Network and Fox Sports New York were the only regional sports networks in the New York area and carried the Yankees under a long-term licensing agreement, the Nets, the Knicks, the Rangers, the Devils, etc.88 And, in a very true sense, their advertising slogan, “New York is our town,” was accurate.89

Now, when the long-term rights agreement—I think it was a ten- or twelve-year agreement—between the Yankees and Madison Square Garden came up for renewal, there was a contentious fight and litigation over the continuation of those rights.90 The licensing agreement, like many sports licensing agreements, had a “right to match” provision in it.91 What at least the owners of the Yankees recognized was that the middleman—that is, the programming network level—was a new line of business that was potentially quite lucrative. And why should they give it up to somebody else?

So the Yankees and the Nets got together and formed YankeeNets,92 and they then, in turn, after litigation—there was litigation which resulted in a settlement that allowed the Yankees, in effect, to get back their broadcast rights and then re-market them free of any matching provision.93 What they did was they ended up joining with other partners to create the YES Network.94

YES Network was an independent programming network. It was not affiliated with a cable company or a national media company, which was a new model.95 But, instead, it was affiliated with the actual teams that were being broadcast. So, in effect, the benefit of the broadcast was now being fully exploited by the owners of the teams rather than by deferring to the cable companies.

It has led to a fight between the cable companies and the owners of the teams because there are some thirty-one regional sports networks across the country,96 and traditionally they have been controlled by cable companies or other giant media companies, and now the future model seems to be the teams taking over their rights and trying to do the programming themselves.

….

Traditionally, there has been an interdependence between the regionals’ programming and the distribution. You can’t have a successful regional programming network unless you get to the customers in that region because, in effect, what regional sports programming networks capitalize on is the much greater appetite that local fans have for their teams than a national audience would have. Therefore, there may be twelve major Yankees games broadcast by Major League Baseball over national network television, but there are 150 or 160 games that are broadcast over the local regional sports network to the people in New York who would like to see a lot more games and follow the team much more closely. The traditional model was that the cable company wanted to ensure that it had the control of all those games so that it could guarantee delivery. Now the teams are controlling it, and yet the teams cannot do it without access to the distribution.

….

One of the examples mentioned earlier was Paul Allen’s venture out on the West Coast.105 As I understand it, it did not succeed, and the reason it did not succeed … is that they did not have the key piece, that is, the access to the distribution channel, because the cable companies refused to do a deal with them. And so that highlights the power that refusal to carry by the cable company has in determining the success of a regional sports network.

Let me turn to the second point that I wanted to raise, which is an outgrowth of the first, and that is whether the future of sports broadcasting is going to be in broadcast basic or expanded basic, which is what most people pay for when they sign up for either a satellite product or a cable company.106 In effect, what you do is pay about $40 or $50 a month, and the satellite company or the cable company decides what comes with that price. You typically get CNN, the History Channel, the network broadcast signals, ESPN, and then…you get the local regional sports networks.107

As the … fight between YES and Cablevision108 illustrates, Madison Square Garden Network and Fox Sports New York, with some exceptions that I will not get into because it is just too complicated to take up the time right now, are carried in Cablevision’s advanced basic offering. Cablevision requires all other cable companies in the area to offer it that way. And that is the way in which regional sports program networks are offered throughout the country.

One of the things that Cablevision is saying—and this again is in the papers—is that YES is too expensive, that subscribers to Cablevision should not be forced to bear the cost of YES if they do not happen to be Yankees fans.109 Well, what they are saying is a challenge to the entire way in which the cable industry has developed. Everybody who subscribes to cable probably has some channels that they never watch, yet they are still paying for. That is always the problem with bundling. In some sense, it is like a newspaper—you buy the New York Times, you might never read the editorial page, or conversely you might not ever reach the sports page, but you are still paying for it. Expanded basic is essentially the same idea. You’ve got the Travel Channel, History Channel, cooking channels, sports, news, and you are not asked to pick which ones you want to include in the package.110

Now, the idea of picking is what is referred to as “á la carte,” and there may be a future in which when you sign up for your cable company, you agree to pay a price, such as $40 a month, and you pick from a Chinese menu of programs, and you get to select ten or fifteen. The problem with that is that it completely redistributes the way in which the revenues and costs would flow, and it is unclear whether a lot of channels would survive, such as the History Channel or a lot of specialties. The sports networks, interestingly enough, would probably be the most vigorous under that model.

But again, the problem in the … Cablevision proposal is that trying to do it with just one network isolates it in a way that it would be economically infeasible. And so if the industry is going to move to a model of “á la carte” or “tiering,” it has to be done on a broad basis, such as putting all sports, including national sports, on a tier, or putting at least all regional sports on a tier.

….

I will conclude by saying that the outcome of this debate goes well beyond the sports world, but the most obvious effect that it would have in the sports world is if the cable companies prevail and they are able to keep regional sports networks off the air if the price is not what they want to pay, then there is going to be a lot less money for regional sports networks; and if there is a lot less money for regional sports networks, that means a lot less money to pay for the broadcast rights from the local teams. And if there is less money for the broadcast rights, that means there is less money to pay salaries of players.

So, the outcome of the current fight between the cable companies and the teams and the fight between independent regional sports programmers and the cable companies for control will have wide ramifications not only for the immediate companies involved but for ultimately the teams themselves….

Notes

3. See, e.g., J.R. Ball, Can TFN Find Its Niche?, GREATER BATON ROUGE BUS. REP., Aug. 5, 2003, at http://www.businessreport.com/pub/21_24/cover/3636-1.html.

4. Digital Television (“DTV”) is a type of broadcasting technology by which broadcast television stations and cable providers send their signals out to viewers digitally. See Fed. Communications Comm’n [FCC], Strategic Goals: Media, Digital Television, at http://www.fcc.gov/dtv/ (last modified Sept. 10, 2003); Digital Television, What Is Digital Television? Consumer Information Page, at http://www.digitaltelevision.com/consumer/what.shtml (last visited Feb. 6, 2004).

5. According to the FCC, bandwidth, the range of frequencies over which analog television is broadcast, is scarce. See FCC, Strategic Goals: Spectrum, at http://www.fcc.gov/spectrum/ (last modified Oct. 6, 2003) (“Because there is a finite amount of spectrum and a growing demand for it, effectively managing the available spectrum is a strategic issue….”). Alternative broadcasting methods, such as digital television, are more efficient and will make the broadcast spectrum available for other uses. Cf. KAET-DT, Glossary of Terms, at http://www.kaet.asu.edu/dtv/glossary.htm (last visited Feb. 6, 2004) (“Analog television receives one continuous electronic signal. In contrast, DTV works on the same principle as a computer or a digitally recorded compact disk. It uses binary code, a series of ones and zeros, rather than a continuous signal.”).

6. NBA TV allows viewers to purchase television packages of live National Basketball Association (“NBA”) games on cable, satellite, and digital cable. See NBA, NBA TV, at http://www.nba.com/video/nbacom_tv.html (last visited Feb. 6, 2004).

7. See Ball, supra note 3.

8. For the FCC’s discussion of the conversion of analog cable systems to digital television, see FCC, FCC Acts to Expedite DTV Transition and Clarify DTV Build-Out Rules, at http://www.fcc.gov/Bureaus/Mass_Media/News_Releases/2001/nrmm0114.html (Nov. 8, 2001).

9. Out-of-market packages allow viewers across the country to purchase subscriptions to watch games of a particular sport that take place outside of their local area. See, e.g., DIRECTV Sports, Subscriptions, at http://directvsports.com/Subscriptions/ (last visited Feb. 6, 2004).

10. See id.

11. See Gary Brown, How HDTV Works, HowStuffWorks, at http://electronics.howstuffworks.com/hdtv.htm (last visited Feb. 6, 2004). High definition is also referred to as “hi-def” or “HD.”

12. See Gary Merson, High Definition All the Time: The HDTV Insider Talks With HD Net Founder Mark Cuban, HDTV INSIDER NEWS-LETTER (Jan. 2002), at http://hdtvinsider.com/sample.html; see also Comcast Adds ESPN Programming to Local HDTV Service, PUGET SOUND BUS. J. (SEATTLE), July 31, 2003, available at http://www.bizjournals.com/seattle/stories/2003/07/28/daily40.html (last visited Feb. 6, 2004).

….

16. TiVo is a service that can be programmed to find and digitally record a user’s choice of shows. See TiVo, The TiVo Story, at http://www.tivo.com/5.1.asp (last visited Feb. 6, 2004).

17. See id.

….

20. Motorola is the official wireless communications sponsor of the National Football League (“NFL”). See Terry Lefton, Motorola Renews with NFL for $105M: League Bags a Big One as Sideline Sponsor Returns for 5 Years and Plans to Do Additional Promotions, STREET & SMITH’S SPORTSBUSINESS J., Nov. 12–18, 2001, at p1.

21. The NASDAQ reached its all-time high on March 10, 2000 when the index closed at 5048.62. See K.C. Swanson, Lessons From the Folly: Opening the March 10, 2000, Time Capsule, THESTREET.COM (Mar. 8, 2001), at http://www.thestreet.com/pf/funds/investing/1335205.html.

22. For an overview of Major League Baseball’s subscription services, see Major League Baseball, Subscriptions, at http://mlb.mlb.com/NASApp/mlb/mlb/subscriptions/index.jsp (last visited Feb. 6, 2004).

….

26. See, e.g., David Barron, Rockets to Begin Network: Astros to Be Joint Owner If FSN Can’t Equal Offer, HOUSTON CHRON., Mar. 1, 2003, at Sports 1 (discussing the proposed Houston Regional Sports Network), available at http://www.chron.com/cs/CDA/ssistory.mpl/sports/bk/bkn/rox/1800212 (last visited Feb. 6, 2004).

27. According to a 1997 poll, cable television provided over 14,000 hours of sports each year, with the four major networks contributing an additional 2,100 hours of televised sports. See Soonhwan Lee & Hyosung Chun, Economic Values of Professional Sport Fran -chises in the United States, SPORT J., at http://www.thesportjournal.org/2002Journal/Vol5-No3/econimic-values.htm (last visited Feb. 6, 2004).

28. In 2002, the sports industry grossed over $212.53 billion annually. See Tim Kroeger, “Sporting” New Technology, at http://komar.cs.stthomas.edu/qm425/03s/Kroeger1.htm (last visited Feb. 6, 2004).

29. See USAToday.com, Baseball, Inside Alex Rodriguez’s Record Deal, at http://www.usatoday.com/sports/baseball/mlbfs41.htm (last updated Dec. 20, 2000).

30. The actual purchase price was $550 million. See Barry Horn, FSN Adds Rangers, Stars over-Air TV Rights, DALLAS MORNING NEWS, Mar. 23, 2000, at 8B.

31. In 2001, the New York Yankees received over $56 million in combined television and radio contracts, while the Montreal Expos received $536,000. See Doug Pappas, The Numbers (Part Two): Local Media Revenues, at www.baseballprospectus.com/news/20011212pappas.html (Dec. 12, 2001).

32. For the regional sports networks’ blackout regulations of individual sports leagues, see Dishnet, Sports Blackout Information, at http://www.dishnet.com/images/multisports/blackout.html (last visited Feb. 6, 2004).

33. See Staci Kramer, Sports Nets Get Closer to Home, CABLEWORLD, Jan. 6, 2003, available at http://www.kagan.com/archive/cable-world/2003/01/06/cwd03010607.shtml (last visited Feb. 10, 2004).

34. Cf. Comcast SportsNet, FAQ, at http://midatlantic.comcastsportsnet.com/faq/faq.asp (last visited Feb. 6, 2004) (“If you live outside of Comcast SportsNet’s broadcast territory you may get Comcast SportsNet’s Orioles, Wizards and Capitals broadcasts via DirecTV).by ordering the MLB Extra Innings package, the NHL Center Ice package or NBA League Pass or through an outer-market package which your cable system may offer.”).

35. See generally Jeff Friedman, The Impact of Major League Baseball’s Local Television Contracts, 10 SPORTS LAW. J. 1, 3–9 (2003

36. See, e.g., FindLaw, Corporate Counsel Center, Purchase of NBC TV Advertising Inventory, at http://contracts.corporate.findlaw.com/agreements/net2phone/nbc.ad.1999.06.25.html (last visited Feb. 8, 2004).

….

42. See supra note 30 and accompanying text.

43. See id.

44. Paul Allen, owner of the Portland Trailblazers, launched the Action Sports Cable Network in July 2001. See Andrew Seligman, Commentary: ASCN Folds, and That’s a Good Thing for Trail Blazers, COLUMBIAN (VANCOUVER, WASH.), Nov. 8, 2002, at b1. The network went out of business in the fall of 2002. See id.

45. See Done Deal: Red Sox Sold to Henry Group; Duquette’s Days Numbered, SI.com, at http://www.cnnsi.com/baseball/news/2002/02/27/redsox_sold_ap/ (Feb. 27, 2002). The reported value of the deal was $660 million. See id.

46. See id.

47. See id.

48. See Len Maniace, YES-Cablevision Dispute Settled, JOURNAL NEWS (WHITE PLAINS, N.Y.), Mar. 13, 2003, available at http://www.thejournalnews.com/print_newsroom/031303/a01p13yes.html (last visited Feb. 10, 2004).

….

56. See NBC Cable Networks, NBC Olympics & Clear Channel Advantage in Joint Marketing Alliance, at http://www.nbccableinfo.com/insidenbccable/networks/Olympics/resources/inthenews/081303.htm (last visited Feb. 8, 2004).

57. See supra note 20 and accompanying text.

58. ESPN Classic, which launched in May 1995, “is a 24-hour, all-sports network featuring the greatest games, stories, heroes and memories in the history of sports.” See ESPN ABC Sports, Customer Marketing and Sales, at http://www.espnabcsportscms.com/adsales/portfolio/index.jsp?content=general_portfolio_expanded.html#classic (last visited Feb. 8, 2004).

….

60. See Nadine Sack, Reality Programs Dominate TV, Red & Black, Feb. 28, 2003, available at http://www.redandblack.com/vnews/display.v/ART/2003/02/28/3e5f8e32bc-590?in_archive=1 (last visited Feb. 10, 2004).

61. ESPN/ABC Sports currently operates several media outlets, including ESPN, ESPN2, ESPN Classic, ESPN Radio, ESPN News, and ESPN.com. See ESPN ABC Sports, Customer Marketing and Sales, The ESPN ABC Sports Media Mix, at http://www.espnabcsportscms.com/adsales/portfolio/index.jsp?contentportfolio.jsp?category=PORTFOLIO (last visited Feb. 10, 2004).

62. See Jon Lafayette, ESPN Sweetens Bitter Pill of Next Rate Hike: Execs Say Extreme Sports SVOD-broadcast Service Adds Value, CABLEWORLD, Apr. 29, 2002 (noting that ESPN is the most expensive national basic cable service at $2 per subscriber), available at http://www.kagan.com/archive/cableworld/2002/04/29/cwd141722.shtml (last visited Feb. 10, 2004).

….

64. See generally Charles P. Pierce, The Decline (and Fall) of Baseball, BOSTON GLOBE MAG., June 23, 2002, at 12 (discussing the problems facing baseball, including its declining popularity).