CHAPTER SIX

INTRODUCTION

Hundreds of teams are competing in sports leagues throughout the United States, and thousands more are competing globally. Revenues generated by sports leagues can be divided into two very broad categories: (1) national (and global) revenues that are shared equally by all of the teams in the league and (2) local revenues generated by each individual team that are retained, in large part, by that individual team.

Like franchises in many other industries, professional sports franchises are typically granted an exclusive geographic territory by the league in which they play that is theirs to exploit. These home territories range from a 50-mile radius from the home city in the NHL to a 75-mile radius from the home playing facility in the NFL, NBA, and MLB.

The market in which a team plays obviously has an enormous impact on its local revenue-generating capability. Every city is different, and this is manifested in the team’s ability to monetize the local market. As one travels to various cities across the United States, the differences are readily apparent. New York, Green Bay, San Diego, and Detroit are all very different places, yet their teams compete against one another and they are allowed to generate revenues in their local marketplaces. The size of the market and fan avidity in those marketplaces varies greatly.

Like all businesses, professional sports teams are always attempting to increase their revenues. But the fact that teams come together in the context of a league makes for an interesting dynamic. Teams with a larger revenue-generating potential sacrifice some of their upside for the betterment of the league as a whole. This is effectuated by the presence of league-wide agreements in a variety of areas, from the creation of defined home territories to revenue-sharing programs. Thus, a fundamental tension exists between the teams that try to push the envelope of league rules as far as possible (and sometimes even break them), and the league offices, which attempt to control these aggressive behaviors. The first article by Jack Williams discusses potential revenue streams for professional teams.

These local revenues are extremely important to the financial fortunes of each team. Sports fans are tribal in nature and are passionate about their teams. Fans disproportionately support their hometown teams over outof-market teams, and fan avidity is strongest in the local market. In short, fans “root, root, root for the home team.” Teams monetize this passion in their local market through a number of different means. Local revenues are typically generated through ticket sales; stadium-related revenues, such as luxury and club seating premiums, stadium club fees, and facility naming rights fees; concessions and parking revenues and other revenues derived from the facility on game and nongame days; local media rights deals with local cable and broadcast television outlets and radio stations; local advertising and sponsorship sales; and sales of novelties, programs, and merchandise sold in the stadium and at team-owned stores. National revenues are generated through league-wide media rights deals with national broadcast, cable, satellite, and radio companies; revenues generated by league-owned sports networks; digital media revenues realized through league and team Web sites; league-wide sponsorship deals; consumer products and licensing; league events and the hospitality surrounding them; and all international revenues generated by the league and its teams.

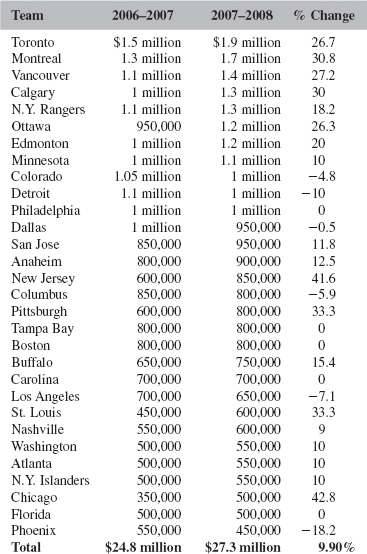

Extrapolating from the Green Bay Packers 2008 annual report, distribution of non-media-related national revenues in the NFL in 2007 totaled nearly $1.1 billion. Distribution of media-related national revenues was $2.8 billion. (See Table 1 for an overview of the Green Bay Packers’ finances.) The importance of each revenue source varies both by league and by team, as does the relative importance of local revenues in the overall league revenue mix. For example, local revenues comprise over three-quarters of MLB revenues due to the large number of games played; at the same time, they comprise less than half of NFL revenues because of the size of the national media contracts held by the league (a consequence of the league’s popularity, the relatively small number of games played, and the fact that all games are broadcast nationally). NHL teams generated a combined $1.12 billion from regular season gate receipts alone in 2007–2008, a season in which the league generated a total of $2.56 billion. Ticket sales are the lifeblood of NHL franchises, because its national revenues, especially those from its national television contracts, are relatively low compared to other leagues. See Table 2 for NHL team ticket revenues in 2006–2007 and 2007–2008. This chapter focuses on the primary revenue opportunities available to each team in the local market, its primary expenses, and the accounting issues faced by professional sports franchises.

Table 1 Green Bay Packers Financials, 2007

| Revenues Source | Amount |

National TV revenue | $87.5 million |

Road-game share | 15.1 million |

Other national NFL revenue | 32.9 million |

Local revenue | 105.8 million |

Total Revenue | $241.3 million |

| Expenses | |

Operating expenses | 219.9 million |

Player Expenses | 124.7 million |

Operating Profit | $21.4 million |

Source: Green Bay Packers 2008 Annual Report.

As noted earlier, gate receipts are a key revenue driver for sports franchises. Team Marketing Report issues a seasonal report for each league that documents ticket prices across the league. According to its most recent reports, the average ticket price in the NFL in 2009 was $74.99, with the average for each team ranging from $160 for the Dallas Cowboys to $51 for the Buffalo Bills. The average ticket price in MLB in 2009 was $26.64, from the high of $73 charged for the average ticket to a New York Yankees game in their new stadium to a low of $14 charged by the Arizona Diamondbacks. In the NBA, the average ticket price was $49.47 in 2008–2009, with a high of $93 for the Los Angeles Lakers to a low of $24 for the Memphis Grizzlies. Finally, the average ticket to an NHL game cost $49.66 in 2008–2009, ranging from $76.15 for Toronto Maple Leafs tickets to $29.94 for the St. Louis Blues.1 This highlights the difference in demand for the tickets for teams even within the same league. It is not surprising that very popular teams in markets where fan avidity is strong, such as New York, Dallas, and Toronto, can charge more for tickets than those less popular teams located in Phoenix, Memphis, and Buffalo. Season tickets are immensely important for teams, because they provide annual upfront revenue that is guaranteed regardless of team performance and a myriad of other factors. Individual game sales and group sales comprise the remaining ticket sales. Demand for tickets to any one game is a function of a number of different factors—the won–loss record of the home team, team tradition, the presence of a superstar player, the quality of the visiting team, promotional giveaways, day of the week, weather, and perceived value. The article by Berri, Schmidt, and Brook examines the impact of star players on gate receipts in the NBA; the excerpt that follows by Lawson, Sheehan, and Stephenson looks specifically at the impact that David Beckham’s arrival had on MLS ticket sales.

In order to drive attendance and increase revenues to lower-demand games, teams began to widely adopt variable ticket pricing schemes in the early 2000s. These pricing policies can be based on any number of different factors, including many of those that have already been noted. Beyond the primary ticket market composed of season, individual, and group sales, teams are attempting in varying degrees to monetize the secondary ticket market. Traditionally the prerogative of ticket scalpers and licensed ticket brokers, technological innovations and entrepreneurial endeavors have led to the creation of more transparent, and thus legitimate, secondary ticket markets. Teams and leagues have established their own secondary ticket markets and have struck marketing deals with established market leaders such as StubHub. In addition, recognizing that they have sacrificed millions of dollars in ticket revenues to suboptimal pricing models, savvy teams have used these secondary markets to gauge the inefficiencies in their pricing models and make the appropriate modifications in their pricing in subsequent seasons. The article by Rascher, McEvoy, Nagel, and Brown takes a deeper look at variable ticket pricing strategies in MLB.

Table 2 NHL Ticket Revenue per Game

Source: Toronto Star graphic from NHL data. Reprinted with permission–Torstar Syndication Services.

Beyond gate receipts, teams can generate substantial revenues from their playing facilities. The recognition of these potential revenues leads to periodic facility-building booms across professional sports, including one that is currently approaching its end. Seeking to fully monetize their home contests, teams have sought to build stadiums and arenas funded as much as possible from public sources. The construction of a new facility is a transformational moment for a professional sports franchise, because it creates a host of new revenue streams. Beyond providing teams with the ability to substantially increase ticket prices, new revenues can be generated from the sale of naming rights to the facility; multiple-season leasing of luxury seating and other premium seating areas; seat licensing fees; the creation of lucrative marketing partnerships; the establishment of new concessions agreements with one of the dominant concessions companies and new parking arrangements with the appropriate body; and the possibility of hosting events at the facility on nongame days. Table 3 examines the local revenues generated by the New Orleans/Oklahoma City Hornets during the 2006–2007 season.

Sports venue concessions in the United States are dominated by a handful of providers. Sports franchises that control the concessions environment in their facility either through ownership or by the terms of their lease typically outsource this function in order to focus on their core competencies. Aramark (31% market share), Levy Restaurants (19%), Centerplate (16%), and SportService (16%) dominate the marketplace, with the remainder divided among a number of smaller firms (9%) and teams that handle concessions in-house (9%).2 Facility operators enter into long-term contracts with concessions companies that are granted the exclusive right to provide their products and services at the venue. The most common types of vendor contracts are profit-and-loss agreements, whereby the concessionaire receives all of the net sales and bears all of the expenses from providing its services at the facility; profit-sharing agreements, whereby the venue is paid a commission based on the concessionaire’s profits at the venue; and management fee agreements, whereby the concessionaire is paid a management fee for its services. In most of these contracts, the concessionaire pays the facility a significant upfront payment and agrees to upgrade the facility’s concessions infrastructure. This can provide the franchise quite a windfall if it controls the concessions at the facility. The excerpt from Coates and Humphreys examines the relationship between the demand for attendance at MLB games and the prices of tickets and concessions.

Table 3 Oklahoma City/New Orleans Hornets Local Revenue, 2006–2007

| Revenue Source | Amount |

Season tickets | $28.7 million |

Single-game and group tickets | 1.5 million |

Sponsorship/advertising | 9.35 million |

Suite sales | 3.9 million |

Club seats | 1.35 million |

Concessions | 921,000 |

Merchandise | 132,000 |

Parking | 198,000 |

Other | 6,000 |

Total Local Revenue | $46.1 million (in OKC, $40.6 m; NO, $5.5 m) |

Source: New Orleans/Oklahoma City Hornets 2006–2007 statement of local revenue.

Note: 35 regular season games and 2 preseason games in Oklahoma City, 6 games in New Orleans.

A recent trend in stadium construction that teams are attempting to monetize whenever possible is to incorporate the facility into a larger real estate opportunity. The modern sports facility is typically part of a larger mixed-use project that incorporates residential housing, hotels, retail stores, restaurants, movie and music theaters, and bars into an entertainment zone that the team will participate in developing. Examples of this include the Staples Center in the AEG Live project in Los Angeles; Gillette Stadium in the Patriot Place development in Foxboro, Massachusetts; and proposed projects in Brooklyn (Atlantic Yards), Philadelphia, and St. Louis. The financing of each new stadium project is idiosyncratic; some locales are willing to provide a substantial amount of the funding for the project, whereas others are unwilling to provide anything beyond infrastructure. If such a thing exists, the typical deal of late involves a public–private partnership, with the project funded by both public and private financing. Chapter 7 explains stadium revenues and funding in great detail.

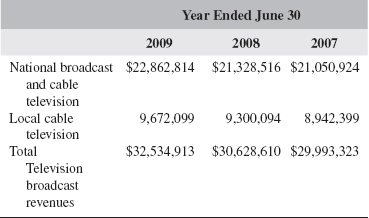

In addition to stadium-related revenues, the national and local sale of broadcast, cable, satellite, radio, and Internet rights can provide teams with vast amounts of revenue. (Chapter 8, which focuses on media, provides a wealth of information on this topic.) In the United States, the sale of national television rights through each league’s current long-term deals provides the NFL with an average of $3.7 billion annually through 2013; the NBA with an average of $930 million per year through 2016; MLB with an annual average of $783 million through 2013; NASCAR with an average of $560 million until 2014; and the NHL with $72.5 million per annum through 2011. Thus, each NFL team receives an average of $115.6 million per year from the current national television deal; each NBA team receives $31 million; each MLB club gets $26.1 million; and each NHL team nets $2.4 million.

The media revenues available at the local level vary by team and league. NFL teams are generally limited in their ability to monetize local media, because the presence of the overarching national media deals leaves them with a limited inventory of local media opportunities, consisting of preseason television rights, regular season radio rights, and shoulder programming, such as pre- and post-game shows, coaches’ shows, and youth-focused shows. MLB teams, in contrast, have substantial local media opportunities. Forbes estimated that in 2008 MLB teams earned a combined $690 million from local cable deals—an average of $23 million per team.3 The revenues are top-heavy, with the top 10 teams generating $379 million. See Table 4 for information on MLB’s largest local media deals.

A number of teams own part or all of their regional sports networks, which offers tremendous revenue potential, because teams can receive part of the advertising dollars and subscriber fees that drive these businesses. For the Boston Red Sox, New York Yankees, Toronto Blue Jays, Cleveland Indians, Chicago Cubs, Chicago White Sox, Washington Nationals, Baltimore Orioles, San Francisco Giants, and New York Mets, this ownership is a windfall. Other teams receive a guaranteed rights fee for the sale of their games, including the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim, who receive an average of $40 million per year as part of their long term deal with FSN West.4 The revenue disparity among MLB clubs in their local media deals is noteworthy, with teams in the lower third of the scale receiving a fraction of those in the top third.

Table 4 Baseball’s 10 Largest Local Cable Deals

| Team | Cable Deal Per Year | Cable Network |

New York Yankees | $80 million | YES |

New York Mets | 52 million | SNY |

Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim | 40 million | FSN West |

Detroit Tigers | 33 million | FSN Detroit |

Los Angeles Dodgers | 31 million | Prime Ticket |

San Francisco Giants | 30 million | CSN Bay Area |

Seattle Mariners | 29 million | FSN Northwest |

Arizona Diamondbacks | 28 million | FSN Arizona |

Baltimore Orioles | 28 million | Mid-Atlantic Sports Network (MASN) |

Washington Nationals | 28 million | Mid-Atlantic Sports Network (MASN) |

Source: Christina Settimi, “Baseball’s Cable Kings,” Forbes, April 22, 2009.

The popularity of NBA and NHL teams allows them to similarly monetize their local media rights, though typically not nearly to the same degree as their MLB brethren. This is a function of the ratings generated (which, in turn, is a function of the popularity of the team in the local market) and there being half as many games played in each league (162 in MLB vs. 82 in the NBA and NHL).

Teams and leagues generate revenue through the sale of sponsorships at both the national and local levels. Sponsoring companies use the association, exposure, and ability to leverage their relationships with the team or league to achieve their marketing goals.5 The sponsorship may entail a number of different elements, including advertising, grassroots marketing, hospitality, cause-related marketing, sales promotion, and public relations.6 With various levels of sponsorships sold by leagues at the national level and by teams at the local level, there is ongoing debate about which categories of sponsorship, if any, should be reserved exclusively for either the teams or the leagues. Another issue is the degree of category exclusivity that should be provided at each level. Broad category exclusivity can be of great value to the sponsor. The NFL example is instructive. The league has a large number of sponsors at the league level, as seen in Table 5. Although the benefits of these deals vary, sponsors typically receive category exclusivity, the ability to use league marks in advertising and promotions, signage at league events, media exposure, and hospitality benefits. The NFL’s sponsorships with Gatorade (isotonic beverage), Motorola (wireless telecommunications equipment), and Reebok (on-field apparel)—all of which appear on the playing field and/or sidelines—are exclusive to the league; that is, no team may sell sponsorships in any of these categories. These deals are quite lucrative: Gatorade pays the league a reported $45 million annually through 2011 for the sponsorship, Reebok pays over $30 million annually through 2012, and Motorola pays $50 million annually through 2011 to showcase a product that it does not even sell at retail—coaches’ headsets! In the other categories, teams may sell sponsorships in their local markets alongside the league’s national deals. In the most lucrative of these nonexclusive league deals, Anheuser-Busch pays a reported $200 million per year (including up to $50 million in cash rights fees and an additional $150 million in marketing, media, and team spending commitments) for its Bud Light brand to be the league’s official beer from 2011–2016. This deal replaces the NFL’s previous beer sponsorship with MillerCoors that paid a reported $100 million annually. At the team level, the sale of sponsorships similarly can be exclusive or nonexclusive. For example, in 2009 the Philadelphia Eagles had beer sponsorships with Miller Lite, Budweiser, and Heineken. Overall, the team had 45 sponsors at multiple levels in a number of different categories.

Table 5 NFL Sponsorships, 2009

| Sponsor | Product or Service | Year Sponsorship Began |

Bank of America | Team identified credit cards, official bank; NFL affinity credit cards | 2007 |

Bridgestone | Automotive tires | 2008 |

Campbell Soup | Soup, canned pasta, tomato food sauces, salsa, chili | 1998 |

Canon USA | Cameras and equipment, binoculars and field glasses, photo printers, camcorders | 1984 |

FedEx | Worldwide package delivery service | 2000 |

Frito-Lay | Salted snacks, popcorn, peanuts and peanut products, salsa, dips | 2000 |

Gatorade | Isotonic beverage | 1983 |

General Motors | Passenger cars, passenger trucks | 2001 |

IBM | Computer hardware and software, IT services | 2003 |

Mars Snackfood | Chocolate and non-chocolate candy products | 2002 |

MillerCoors | Beer | 2002 |

Career services | 2008 | |

Motorola | Wireless telecommunications equipment | 1999 |

National Dairy Council | Milk products | 2003 |

National Guard | NFL High School Player Development | 2009 |

News America | Super Bowl insert | 1979 |

Pepsi | Soft drink | 2002 |

Procter & Gamble (Prilosec OTC) | Over-the-counter heartburn medication, locker room products | 2005 |

Samsung | Televisions, stereo and speaker components, DVD players and recorders | 2005 |

Sprint | Wireless telecommunications services | 2005 |

Ticketmaster | Online ticket exchange provider | 2008 |

Tropicana | Juice | 2002 |

Visa | Payment systems services | 1995 |

Source: “NFL close to IBM renewal; Visa up next,” SportsBusiness Journal, September 14, 2009. Used with permission of the National Football League.

In addition to revenues generated directly from the aforementioned sources, professional sports franchises, leagues, and other sports properties realize significant monies through the sale of officially licensed products bearing their names, logos, and marks. In 2001, the NFL sold $2.5 billion of licensed products. MLB had sales of $2.3 billion, and NASCAR’s sales were $1.2 billion. The NBA generated $1.0 billion, and the NHL sold $900 million of its goods. Collectively, the sale of sports-related products represented 14.9% of all licensed goods sold in the United States in 2001. This figure actually represents a decrease from previous years in the overall sales of sports-related licensed goods, which is likely attributable to both a shift in fashion trends and a downturn in the economy. The fickle nature of fashion can cause revenues to fluctuate, presenting a problem to professional sports leagues and franchises in that the uncertainty in the revenue stream can dissuade the entity from relying on the sale of licensed products in its budgeting process.

Licensees—the manufacturers of these products—typically pay the sports property a royalty fee ranging from 4 to 10% of the wholesale selling price of the goods (depending on the product) in exchange for the right to sell products containing league and team names, logos, and marks. These monies are paid by the licensees to each league’s properties division. The respective properties division then pools the funds and distributes them equally across all league teams, similar to the manner in which revenues generated from the sale of national media rights are apportioned. So, although all teams benefit from the increased royalties generated from an increase in the sales of licensed products, there appears to be little incentive for an individual club to incur a significant amount of the cost of doing so, while reaping little of the benefit in the form of increased revenue. To overcome this obstacle, leagues have carved out exceptions to this general revenue sharing rule and typically allow teams to keep a disproportionate share of the proceeds generated from the sale of their licensed products where they also serve as the retailer, such as when selling in their playing facilities and at team-owned stores or when the sale occurs within a specific mile radius of this facility. See Table 6 for the top-selling NFL player jerseys and Table 7 for the top-selling NBA jerseys.

Despite these efforts, the general sentiment among popular clubs with strong licensed product sales, such as the Dallas Cowboys, is that they should not be forced to share the value of their brands with other, less popular clubs that have lower brand value. Thus, the manner in which revenues from licensed products are allocated is likely to remain a matter of intraleague dispute. Although the net revenues received by each club from the sale of licensed products are approximated to be only several million dollars per year, the resolution of this debate is an important indicator of the future of revenue sharing in each league. (See Tables 8 and 9 for a list of top merchandise sales by team in the NFL and NBA, respectively.)

Table 6 Top-Selling NFL Player Jerseys, 2008

| 2008 Rank | Player |

1 | Jets QB Brett Favre |

2 | Cowboys QB Tony Romo |

3 | Giants QB Eli Manning |

4 | Steelers S Troy Polamalu |

5 | Vikings RB Adrian Peterson |

6 | Colts QB Peyton Manning |

7 | Cowboys RB Marion Barber |

8 | Cowboys TE Jason Witten |

9 | Chargers RB LaDainian Tomlinson |

10 | Steelers QB Ben Roethlisberger |

11 | Eagles RB Brian Westbrook |

12 | Patriots QB Tom Brady |

13 | Cowboys WR Terrell Owens |

14 | Bears LB Brian Urlacher |

15 | Falcons QB Matt Ryan |

16 | Giants RB Brandon Jacobs |

17 | Broncos QB Jay Cutler |

18 | Steelers WR Hines Ward |

19 | Bears WR Devin Hester |

20 | Cowboys LB DeMarcus Ware |

21 | Patriots WR Randy Moss |

22 | Redskins TE Chris Cooley |

23 | Ravens QB Joe Flacco |

24 | Bears RB Matt Forte |

25 | Saints QB Drew Brees |

Source: “Cowboys Rank as Top-Selling NFL Team; Favre Leads in Jersey Sales,” SportsBusiness Daily, January 8, 2009. Used with permission of the National Football League.

On a percentage basis, team expenses are generally consistent across professional sports leagues. Player compensation is the biggest expense for every team in the NFL, NBA, NHL, and MLB. An extensive discussion of athlete compensation is found in Chapter 10. The second largest expense for most teams is staff compensation. Head coaches’ salaries have increased dramatically in the past two decades, as has the compensation (and quantity) of assistant coaches. Front office staffs have grown in size as teams have become much more complex organizations, and, although salaries are still much smaller than those of the coaches and players, they represent a sizable expense for most teams.

Table 7 Top NBA Jersey Sales, 2008–2009

| Rank | Player |

1 | Kobe Bryant (L.A. Lakers) |

2 | LeBron James (Cleveland Cavaliers) |

3 | Chris Paul (New Orleans Hornets) |

4 | Kevin Garnett (Boston Celtics) |

5 | Allen Iverson (Detroit Pistons) |

6 | Dwyane Wade (Miami Heat) |

7 | Paul Pierce (Boston Celtics) |

8 | Nate Robinson (New York Knicks) |

9 | Pau Gasol (L.A. Lakers) |

10 | Dwight Howard (Orlando Magic) |

11 | Derrick Rose (Chicago Bulls) |

12 | Ray Allen (Boston Celtics) |

13 | Steve Nash (Phoenix Suns) |

14 | Shaquille O’Neal (Phoenix Suns) |

15 | Carmelo Anthony (Denver Nuggets) |

Source: NBA.com. Figure used with permission from NBA Properties, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Every franchise has team and game-related expenses; that is, those expenses that are associated with team travel to away games and the cost of putting on home games. And, like every business, sports franchises have general and administrative expenses that arise. Teams also have marketing expenses that arise out of their marketing efforts, including the servicing of their numerous corporate partners.

Similar to many other businesses, sports franchises also have a research and development (R&D) expense. Here, the R&D function is called player development. Teams must scout amateur and professional players and pay for the salaries of the players and coaches in its minor league system. Although college basketball and football programs serve as a no-cost player development system in the NBA and NFL, MLB and NHL teams have farm systems that require them to spend considerable sums on player development annually. NBA teams do subsidize their NBDL affiliates, and most NHL teams have one minor league affiliate (and some have two). However, most MLB teams have six minor league affiliates. MLB teams spend approximately $20 million on player development annually.7

Table 8 Top Selling NFL Team Merchandise, 2008

| 2008 Rank | 2007 Rank | Team |

1 | 1 | Cowboys |

2 | 7 | Giants |

3 | 3 | Steelers |

4 | N/A | Jets |

5 | 4 | Bears |

6 | 2 | Patriots |

7 | 8 | Redskins |

8 | 9 | Eagles |

9 | 5 | Packers |

10 | 6 | Colts |

Source: “Cowboys Rank as Top-Selling NFL Team; Favre Leads in Jersey Sales,” SportsBusiness Daily, January 8, 2009. Used with permission of the National Football League.

Table 9 Top NBA Team Merchandise Sales, 2008–2009

| Rank | Team | |

1 | Los Angeles Lakers | |

2 | Boston Celtics | |

3 | New York Knicks | |

4 | Cleveland Cavaliers | |

5 | Chicago Bulls | |

6 | New Orleans Hornets | |

7 | Phoenix Suns | |

8 | Miami Heat | |

9 | Detroit Pistons | |

10 | San Antonio Spurs |

Source: NBA.com. Figure used with permission from NBA Properties, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Teams also have facility-related expenses. Rent payments, stadium upkeep and renovations, utility bills, and seating reconfigurations can all be part of the team’s responsibility as a tenant. The amount depends entirely on the lease deal that the team has entered into. Teams that paid for part or all of their playing facility must service the debt on the facility, which can be onerous, depending on the amount and terms of the financing. More details on facility financing and expenses can be found in Chapter 7.

Facility construction and the purchase agreement are the two largest sources of debt for professional sports franchises. The acquisition of most teams is financed by debt. In 2008, NFL teams carried a combined $9 billion of debt, and MLB clubs carried over $5 billion in debt obligations. Although leagues have facilitated the debt financing process by establishing credit facilities that teams can borrow from, the leagues are wary of teams being weighed down by this debt. To that end, the leagues have enacted rules that restrict the amount of debt that teams can carry. MLB teams must have a 60–40 debt–value ratio (although there are some exceptions for teams in new stadiums), NBA teams are each limited to $175 million in debt, and NHL teams can carry debt up to 50% of the team’s value. The article by Hill and Vincent takes a deep dive into the business of Manchester United, perhaps the top sports brand globally.

Like many other industries, the operations and financial results of professional sports franchises are highly seasonal in nature. Likewise, sports organizations are entities with inventories, production functions, research and development functions, and very high fixed costs that require significant capital. However, unlike other industries, the accounting practices of professional sports franchises vary significantly.

One common accounting issue for professional sports franchises involves the use of related-party transactions. The ownership of sports franchises by non-sports-related businesses and the nature of the sports industry have created numerous opportunities for these types of transactions. Typically, the presence of the nonsports business is used to lower the apparent profitability of the sports franchise in favor of improving the situation of the other, related businesses. This is problematic in that the tax liability of the sports franchise is lowered, and the team’s financial outlook is distorted. A professional sports franchise with an operating profit may be able to claim a book loss. Paul Beeston, a Toronto Blue Jays executive, summed up how the use of related-party transactions can dramatically affect the book profits of a professional sports franchise: “Anyone who quotes profits of a baseball club is missing the point. Under generally accepted accounting principles, I can turn a $4 million profit into a $2 million loss and get every national accounting firm to agree with me.”8 This distortion has been the cause of much controversy, because the misleading financial picture has been relied upon by professional sports franchises in pursuit of new, publicly funded stadia and by professional sports leagues when negotiating collective bargaining agreements with athletes. Teams and leagues have argued that their dire financial status requires that other stakeholders make significant concessions in negotiations.

Although the use of related-party transactions is not an illegal practice per se, it has created animosity and mistrust and, consequently, has harmed the long-term relationships between the negotiating parties. As a result, the perception among many stakeholders is that the financial statements of sports franchises cannot be relied upon whether related-party transactions are being used or not. Given the recent spate of accounting scandals in the United States that have depleted consumer and investor confidence in big businesses across numerous sectors of the economy, it is imperative that the sports industry avoid a similar fate.

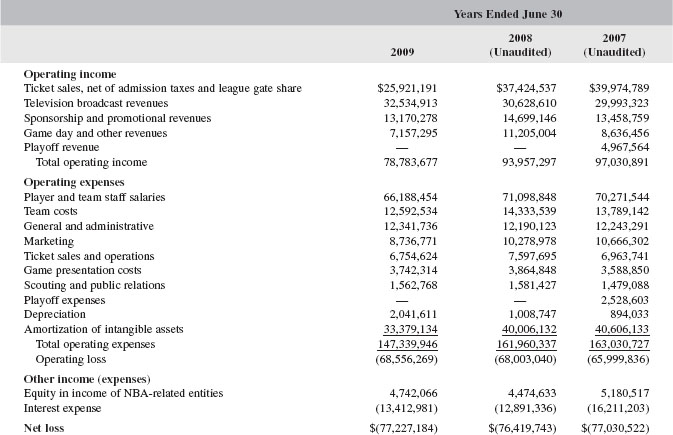

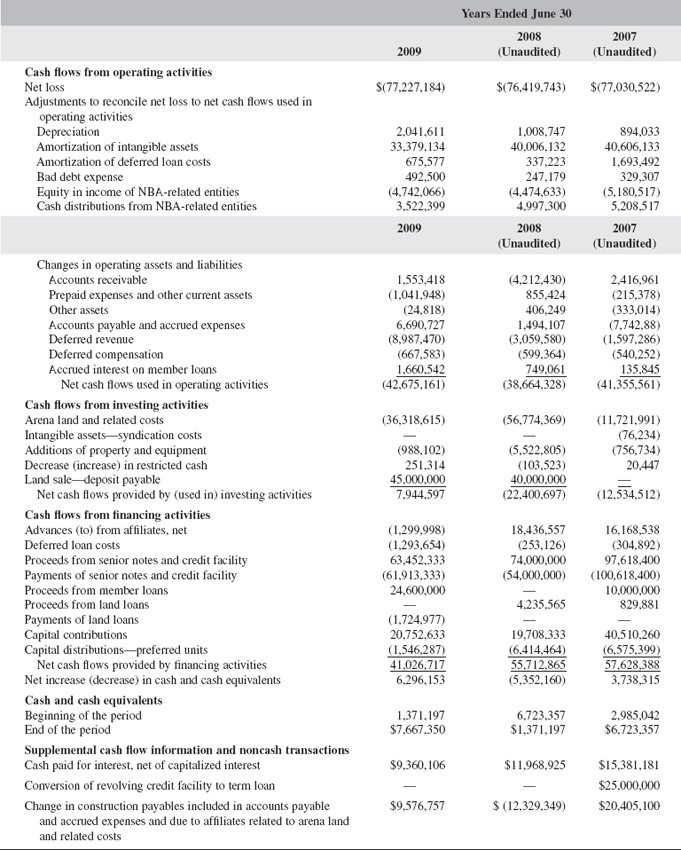

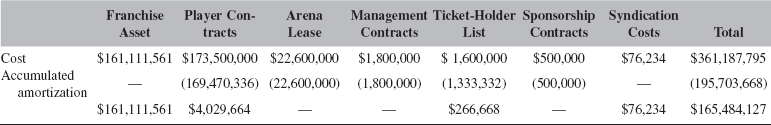

Excerpts from the SEC filing made by the publicly held parent company of the New Jersey Nets upon the announcement of its sale to Russian oligarch Mikhail Prokhorov provide a rare glimpse into the finances of an NBA franchise. The filing indicates a franchise in some financial distress. The Nets’ gross revenues dropped nearly 20% from 2007 to 2009 due to the team’s poor on-court performance and the recession. Although operating expenses also decreased during this period, the team suffered annual operating losses of $68.5 million and $68 million in the two most recent years.

Despite the relative financial strength of the professional sports industry compared to other industries, the financial failures of several franchises and leagues has led those entities to seek financial reorganizations. The Phoenix Coyotes filed for bankruptcy protection under Chapter 11 in 2009 after incurring nearly $270 million in operating losses from 2004 to 2008. (See Table 10 for a list of bankruptcies.) Such reorganization can be done either privately between the franchise and its creditors or publicly through Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code. Although hardly a desirable outcome, it is important for sports industry leaders to understand the process of financial reorganization. In a selection found in the supplementary online materials, Timothy Cedrone gives a comprehensive explanation of this process in both England and the United States.

Table 10 Major Sports Team Bankruptcies Since 1969

| Year | Team | |

2009 | Phoenix Coyotes (Hockey) | |

2003 | Buffalo Sabres (Hockey) | |

2003 | Ottawa Senators (Hockey) | |

1998 | Pittsburgh Penguins (Hockey) | |

1995 | Los Angeles Kings (Hockey) | |

1993 | Baltimore Orioles (Baseball) | |

1975 | Pittsburgh Penguins (Hockey) | |

1970 | Seattle Pilots (Baseball) | |

1969 | Philadelphia Eagles (Football) |

Sources: CNNmoney and East Valley Tribune.

Notes

1. Team Marketing Report, “Fan Cost Index.” Available at http://www.teammarketing.com/fancost/ (accessed June 2009).

2. ESPN The Magazine, July 13, 2009, at 34.

3. Christina Settimi, “Baseball’s Cable Kings,” Forbes, April 22, 2009.

4. Id.

5. Steven M. McKelvey, “Sport Sponsorship,” in Lisa Masteralexis and Carol Barr (eds.), Principles and Practice of Sport Management (3rd ed.). Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett, 2008, at 338.

6. Id.

7. Andrew Zimbalist, “There’s More than Meets the Eye in Determining Players’ Salary Shares,” Sports Business Journal, March 10, 2008, at A4.

8. Larry Millson, Ballpark Figures: The Blue Jays and the Business of Baseball. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1987, at 137.

OVERVIEW

THE COMING REVENUE REVOLUTION IN SPORTS

Jack F. Williams

Along with the U.S. population, [sports’] fanbase has grown enormously in the last half century, as new professional leagues sprouted, media mushroomed, and professional sports became thoroughly assimilated into the entertainment industry. Fans are the geese who have laid the golden eggs for pro athletes, team owners, sports broadcasters. Meanwhile, that same flow of cash has altered the relationship between spectators and the contests. A newfound distance, which can verge on alienation, separates the audience from athletes and teams. Choices made within the sports and political establishments over the next few years may determine whether pro sports’ dizzy growth continues, or if those golden orbs will turn into goose eggs.1

Sports as a business has matured at an accelerating pace in the past two decades.2 During this time period, participants in the business of sports have aggressively pursued alternative sources of revenue in an effort to drive earnings. These new sources are sought both to grow and stabilize revenue.3 In large part, technology has been at the vanguard of the revenue revolution, allowing a level of fan interaction that has changed how we think about sports and the successful sports business plan. Traditionally, the sports market consists of gate revenues for live sporting events; rights fees paid by broadcast and cable television networks and TV stations to cover those events; merchandising, which includes the selling of products with team or player logos; sponsorships, which include naming rights and payments to have a product associated with a team or league; and concessions. Currently, other revenue streams such as internet, satellite, or mobile phone subscriptions to sports events or programming are transforming sports into programming content designed as a means to secure greater revenue. These new sources bring with them a host of legal, financial, and business issues that will challenge our understanding about fundamental aspects of property law, privacy, publicity, and value. This paper will discuss both traditional and non-traditional revenue sources, the legal and business implications they create, and the need for a new business paradigm to address these issues and harness the new synergies the leveraging of existing and future technologies present.

I. STATE OF THE BUSINESS OF SPORTS

Sports is big business.4 Its present structures and attributes are well known.5 … The focus in this article is on the sports entertainment sector. That sector includes professional and amateur sports teams and tournament sports…. The sports entertainment sector is comprised of various firms (i.e., clubs) that join together in leagues to provide similar, well-defined products and services (i.e., some form of competition, media, merchandise, etc.) through similar production methods (i.e., play the game).6

….

II. TRADITIONAL SOURCES OF REVENUE

Traditionally, revenue platforms in the sports sector consist of: (1) gate revenues for live sporting events; (2) rights fees paid by broadcast and cable television networks and TV stations to cover those events; (3) merchandising, which includes the selling of products with team or player logos; (4) sponsorships, which include naming rights and p ayments to have a product associated with a team or league; (5) actual team ownership; and (6) concessions.14 Following is a discussion of how those revenue platforms play out in the context of three professional sports leagues—the National Football League, Major League Baseball, and the National Basketball Association.

A. National Football League (NFL)15

Established in 1920, the National Football League (NFL) has emerged as the most stable of professional sports when it comes to controlled growth, revenue, and financial success.16 …

….

Unlike other industries, sports require the cooperation of all firms through the league and competition on the field of play. Although General Motors Corporation does not need Ford Motor Company to produce automobiles, the Atlanta Falcons need the Dallas Cowboys to produce football games. In an effort to theoretically bring greater competition to the field, the sports entertainment sector has sought various revenue models. The NFL has adopted a sourced approach to revenues: (1) retained revenues and (2) shared revenues.26

Retained revenues are generated and kept by each team; thus, retained revenues are not shared among teams in the NFL…. Retained revenues include the following:

• Sixty percent of the gate receipts from home games,28

• Naming rights,

• Sponsorships,

• Luxury suite revenue,

• Concessions, and

• Local broadcast rights.29

Shared revenues are allocated and shared across the teams in the NFL…. The primary sources of shared revenue include:

NFL Properties, Inc., the marketing arm of the NFL, is also a major revenue source…. Revenue from NFL Properties activities is shared equally among all thirty-two teams, the league office, and NFL Charities.35 Experts, however, have observed that this particular revenue stream may be stabilizing or possibly decreasing because of competition from other sports and consolidation among vendors that deal with NFL Properties.36

Finally, franchise values in the NFL have accelerated at an accelerating rate over the past three decades.

….

B. Major League Baseball (MLB)45

The beginnings of baseball in America are shrouded in some mystery and considerable controversy.46 Although most experts agree that baseball began in the United States in the mid-1800’s, some trace the game back to American Indian stickball and some to the English game of rounders. Many wrongly trace the “invention” of baseball to Abner Doubleday. The legend goes that General Doubleday, Civil War hero, invented baseball in 1839 in Cooperstown, New York. However, in 1839, Doubleday was a cadet at West Point, living a very busy day with hardly the opportunity to play let alone invent a new game. Moreover, General Doubleday never took credit or even mentioned the game of baseball in his many personal journals.47

All early baseball players were amateurs. In 1869, that changed, and with it, the face of the game.48 In that year, the Cincinnati Red Stockings paid its players becoming the first professional baseball team to publicly acknowledge that they actually paid their players, a practice that had existed surreptitiously for some time. By 1876, eight professional teams formed the National League. In 1900, eight teams formed the American League.49 Although the Leagues increased the number of games per season over time, in 1961, the American League increased the number of games played each season by each team from 154 to 162.

….

The attendance at MLB games has steadily increased along with ticket prices…. Each team in MLB generates its operating revenue through several sources.57 These sources include the following:

• Regular season game receipts,

• Local television, radio, and cable contracts,

• Post Season (for those teams that qualify),

• Local operating revenue, and

• National revenue.58

… Presently, MLB teams are participating in a revenue sharing program. In accordance with the program, each team invests thirty-four [now 31%] percent of net local revenues into a pool. The pool is then divided among the teams. Some teams are net contributors, that is, revenue sharing is a net liability, whereas, some teams are net recipients, that is, revenue sharing is a net asset.60

In MLB, when it comes to revenue sources, the gate is still king. Approximately forty percent to fifty percent of total revenue is traced to game receipts.61 When one also considers other local revenues, including concessions, suites, and other game-day in-park revenue, the number increases to as much as sixty percent.62 The gate receipts are shared with approximately eighty to ninety percent retained by the home team and the remaining ten to twenty percent going to the visiting team.63

….

C. National Basketball Association (NBA)68

….

NBA attendance has grown steadily over the past decade….

Unlike the other sports leagues considered in this article, NBA teams keep all home gate receipts and do not share with the visiting teams.77 NBA television contracts also generate substantial revenues.78 …

The NBA has also focused attention on licensing fees.

….

D. Other Revenue Sources

Smart financial and legal minds hover all around sports. Notwithstanding some notable setbacks, failures, and false starts, those folks that toil in these fertile fields have invented and developed several interesting revenue growth models. Most of these models build on traditional revenue sources, using those traditional sources as a platform from which to spring new growth models. The following section explores just a few of these revenue growth models.

1. Architecture

Our first revenue source is a subtle but effective variant of the adage that “gate is king.” Architects have captured something that we fans have known intuitively for some time. If you build a nice stadium, specifically designed and suited for the game at hand, the fan experience is more gratifying. Build a baseball field, construct a football stadium, erect a basketball arena, and watch the fan base grow. Multipurpose sports facilities are out, kind of ugly, and bad for revenue growth. A well-suited facility breeds fan gratification. That gratification translates into more at the gate - both in increased attendance and higher ticket prices.88 What the architects and financial experts have also uncovered, not so intuitive to us fans, is that the smaller the stadium (within reason), the greater the gate.89 The data suggest that the smaller the stadium, the smaller the number of seats; the smaller the number of seats, the more scare tickets become; the more scare tickets become, the more a team can charge for those tickets.90 Under the watchful eye of MLB, architects are working to get the supply-and-demand of stadium design at perfect balance.91 Other sports should also consider this formula; bigger is not always better, at least from a revenue growth perspective.

2. Luxury Suites and Club Seats

Our second revenue source simply seeks to retrofit existing stadiums or incorporate by design in new stadiums a new look and feel to the game that is business and corporate user-friendly. Luxury suites and club seats present a lucrative opportunity for increasing revenues.92 According to some experts, these products represent one of the fastest growing revenue sources in sports.93 New stadiums… are incorporating luxury seats in their design and construction.94 Older stadiums are re-designing and retrofitting their present seats in an effort to convert them to luxury seats.95

Luxury suites, also known as luxury boxes, sky boxes, or executive suites, are private to semi-private rooms that ring the stadium and allow groups to mingle, schmooze, and at least occasionally watch the game either through the large window or balcony or on closed-circuit television. As mentioned these suites are lucrative, allow the team to increase revenue per seat, and hook corporate sponsors.96 Club seats, also referred to as premium seats, do not offer the privacy or most of the amenities of the luxury suite, but are usually more comfortable, often come with service at your seat, and usually have some of the best sight lines in the stadium.97

… It is not unusual for a team to offer several grades of luxury suites based on size, location, and amenities, in order to capture even greater premiums….

3. Pay-Per-View

Professional sports franchises are adding to their revenue through pay-per-view (PPV) contracts with local networks and cable companies.103 Revenues from PPV have increased dramatically from a humble $435 million in 1991 to $3 billion in 2000.104 This is, by all accounts, a virtually untapped revenue resource.

An extension of the PPV platform is to offer the Super Bowl and World Series on PPV in addition to those marquee sports events’ regular network broadcasting. The PPV version could offer different angles, additional content, trivia contests, on-field sound, and the like.

4. Satellite Radio

Professional sports have found a new home on satellite radio. These satellite broadcast providers look to sports to provide content that attracts listeners and advertisers. Fans love satellite broadcast. It allows them the opportunity to follow their home teams even when their employment requires that they change “homes.” This revenue platform is also relatively untapped. Watch for professional sports leagues to enter into the market with a greater presence. Also, watch for the possibility that a professional sports league or combination of leagues explore or consider purchasing their own satellite broadcast company. Imagine the NFL, MLB, and NBA entering into a joint agreement in order to reduce start-up costs and tap an even greater audience with greater league control. Armed with ready-made content, we may witness the revenue race thrusting back to the future when it comes to satellite broadcasts.

5. Personal Seat Licensing

In 1997, personal seat licensing (PSL) was estimated to raise $500,000 in one time fees.105 That number appears to have increased. The PSL is a “cheap” way in which to raise onetime revenue. However, as a revenue generating product, it lacks strategic legs.

6. Media Access Charges

The Media Access Charge (MAC) is a rent based on gross receipts. The MAC operates in a way similar to a percentage rent term between a tenant and a shopping mall. For example, according to the Minnesota Legislature Study on Sources of Revenues, fees from use of the broadcast facility at a stadium, at rates of $10,000 per game for television/cable and $5,000 per game for radio broadcast, would raise an estimated $2.16 million per year from MLB and $215,000 per year from NFL broadcasts.106

7. Naming Rights

…. Although quite cumbersome and the butt of many sports commentators’ jokes, there seems to be no letting up on the name game.

8. Sport as Entertainment

In the arena of sports as entertainment, the NBA is unequivocally “best in show.” Both the NBA and the National Basketball Players Association (NBPA) emphatically recognize that the sports industry, properly understood, is a sector of the entertainment industry. The NBA not only competes with the NFL and MLB, but also competes for the entertainment dollar with movies, recordings, videos, and the like.

The NBA has been aggressive in blurring the distinction between sport and entertainment, exploiting the bleed over of one form of entertainment into the other. Among products that the NBA has developed are the commissioning of a recording that captures the “NBA spirit” and video games that take the video experience to another level of entertainment. For example, the soundtrack for EA sports “NBA Live 2003” was certified a platinum album with over 1 million recordings sold, the first ever video game soundtrack to reach that recording milestone.109

Although both the NFL and MLB have joined the NBA in recognizing that the sports sector is a part of a much bigger picture, the three professional sports leagues have so much unrealized potential that one should not be surprised to see more attempts at exploiting the natural fit between sports and other forms of entertainment. Some may argue that such an alliance is a pact with the devil in that it taints the game, making it too glitzy, too “Hollywood”; that view, however, is quaint and shortsighted.

9. International Expansion

One way in which to increase revenue is to increase the geographic pie. Historically, the NFL, MLB, and the NBA looked exclusively to the United States for their fan base and revenue growth. That has changed. Recognizing that the three professional leagues operate in a mature domestic environment, international expansion is a logical and rational next step to revenue growth. The sports industry is not immune from globalization. For some time, MLB has operated in an international market through exhibition games and the like. It also has successfully discovered and cultivated players from Mexico, the West Indies, Central America, and South America for decades. More recently, player scouting has included other countries like Australia and Canada. In 2006, the World Baseball Classic, a tournament of national teams featuring MLB players on the rosters of the United States and foreign teams, brought baseball to the world in a more formal sense. If not a domestic success, the Classic was certainly an international one. Surprisingly, however, MLB has been slow in moving outside the continental United States.

….

The NBA is also considering international expansion. With the popularity of basketball in Europe, that continent appears to be the likely start for the NBA. The presently existing professional league structure in countries like Italy, France, Spain, and Israel suggests an interesting possibility. Would the NBA consider a merger or alliance with an existing European league? Experts appear to think not; the NBA’s brand is worldwide and already strong in Europe.112 For example, approximately twenty percent of all NBA merchandise (about $430 million) is sold internationally.113 Moreover, over fifteen percent of the $900 million in annual television revenue (excluding local broadcasts) comes from 148 non-U.S. television partners in 212 countries.114 The NBA has also determined that approximately forty percent of its visitors to www.nba.com access the website from locations outside of the United States.115 More promisingly, it appears that almost fifty percent of NBA fans said that the “influx of international players has increased their interest.”116

III. NONTRADITIONAL REVENUE SOURCES

Professional sports leagues are competing in a vicious arena, and one that is not on the playing field. With the heavy competition for the entertainment dollar coming from many different angles, every revenue dollar is precious. However, any professional sports league or organization that sets its eye on the quick buck will someday realize just how much potential revenue slipped through its collective hands.

Professional sports leagues are leaving revenue on the table. Extending existing revenue platforms are necessary but not sufficient in order to maximize revenue. With operating costs increasing, driven largely by player salaries, and with competition being launched from other entertainment sectors that are competing for the same seats and eyes, a new revenue paradigm is necessary….

The key is to find efficient and effective techniques in order to mine such revenue. This emerging revenue paradigm will embrace existing and new technologies. These new technologies will change the fan experience, allowing more interaction and greater fan control over his or her experience. These new technologies will also permit the fan to customize his or her experience, developing a cozy and personalized interface with the game.

Another example may help demonstrate what I am suggesting. NFL future revenue trends necessarily include internet and broadband media rights…. Leveraging the new technologies with these and other relationships is precisely what the NFL must do to compete effectively.

Any revenue paradigm shift would not leave behind existing revenue sources. In fact, a new paradigm would continue to build on and expand such sources. What the new paradigm offers, however, that the old revenue thought experiments did not, is a new perspective. This new perspective is fueled by an understanding that professional sports is not about the game, it is about the way in which we as fans experience the game.

Following are some suggestions for reaping revenue:

1. Housing Related to the Sports Complex

NASCAR has moved into the housing market with luxury suites at the Atlanta Motor Speedway, for example. These houses are selling for more than $1 million. A variety of housing options could be crafted, depending on the venue, to suit a range of budgets. For example, in more rural or suburban areas, a league or team within the league might design and market communities based on their proximity to the venue, with prices descending the farther away one’s home rested.

In urban markets, with land at a premium, it might make more sense to design arenas to incorporate mixed use luxury condo and hotel units into the existing structure. Because major sports complexes frequently host a wide range of activities from massive religious revivals to tractor pulls and from large concerts and conventions to traditional sporting events, the demand for permanent housing to experience the full range of these events might be limited. Nonetheless, hotels allowing customers to self-select the events they wish to see, and rent suites accordingly, might be a viable option.

2. Computers at Your Seat

It is undeniable that every game in every sport faces some down time. Why not offer fans the ability to use a computer while sitting at their seat? Initially, I thought renting a portable device would be the most effective way to go. For example, a Tough Book is a laptop computer designed by Panasonic to take a beating. However, almost immediately, the flaws in this idea become apparent. A laptop is a cumbersome device for someone sitting in cramped stadium seating; if a baseball is flying towards you and you jump up to catch it, your ToughBook is going to go flying. Moreover, because they are portable, the notebook computer would also be easy to steal. Additionally, if you are sitting in an upper deck and you dropped or threw one of those devices, it could kill someone. That is a bad thing.

Yet, still the basic idea has some merit. What if the device was small and folded up, attached to your armrest? It could have a small LCD screen and a place to swipe a credit card. You could order drinks or food from your seat and perhaps check your email. You could allow patrons to surf the web set to your website, of course. Of course, with advances in cell phones and PDAs, it seems unlikely that folks would pay for what they may be able to already do on their own devices. However, beyond ordering food and drinks and surfing the web, what if you offered up the fan the ability to cycle through the various camera signals in the facility. A fan could use the device to access the TV coverage of the game, the camera shots not on the air, and perhaps additional camera feeds (for example, in the locker room, tunnel, dug out, etc.) not available anywhere else. Advertisements could also be mixed in with this programming either in the form of logos appearing on live camera feeds or traditional commercials during breaks.

3. Projected Ads on Field/Court/Ice

Because soccer games do not take commercial breaks, other than at half time, professional soccer was forced to come up with alternative ways of selling advertisements. One revenue source has been to place advertisements around the stadium along the walls surrounding the field. Most professional sports already sell similar advertising. Check out the ads around the ring of a stadium next time you take in a game. Another creative way professional leagues have made up for the lost opportunity for commercials is by selling time for companies to either attach their logo to the bug on the screen or by superimposing their logo directly onto the field of play. When MLB attempted to promote the film Spiderman II by placing the movie’s logo on the bases during one game, MLB was widely criticized for defiling the game.122 Superimposing a logo on the field of play would only be seen by television viewers, and, thus, it might be less controversial. The right to sell those images might be retained by the professional sports teams when negotiating their broadcast licenses.

….

5. Headsets that Would Connect the Fan to the Field

Technology drives new fan experiences. The use of multiple camera angles, helmet cameras, live microphones, sideline interviews, slow motion, instant replay, superimposed first down lines, and the like are designed to bring a new and fresh experience to the fan. A new fan experience that would extend that logic could include headsets that would connect the fan to the field of play by allowing fans to listen to the interaction among coaches or between a coach and his players. Obviously, teams would need to be certain that providing radio content did not violate any exclusivity rights offered to their broadcasters. This could be done either by renting/selling cheap headsets that could pick up a low frequency radio signal or by simply providing the signal and allowing fans to bring their own radios. It is not unusual for fans to watch a game, in person or on TV, with the sound turned down, while simultaneously listening to the play-by-play on the radio. Fans could choose to do this in most arenas already by simply tuning into their local radio station that is broadcasting the game. In addition, what if fans were given access to radio feeds that picked up sideline/on-the-field conversations or picked up signals from up in the booth? This could be offered for free with commercials or offered for a service fee with or without commercials.

….

7. Interactive TV

Interactive Television or iTV is touted as a technology that will change the way a fan interacts with the sports broadcasting. By providing greater access to content including statistics, live games, commentary, and perhaps linking content to a fan’s fantasy team, the iTV promise is to generate greater interaction between a fan and the sport and to retain viewership.125 Additionally, broadcasters could offer viewers the ability to cycle through alternative camera angles for a single game or display multiple games simultaneously.126

8. Broadcast License for Trains and Airlines

Professional sports, assuming this would not violate their contracts with TV broadcasters, might license train and airline companies to provide live coverage of their games or, perhaps, video of past “classic” games. This could be either by pay-per-view with a customer swiping a credit card through the monitor on the seat back in front of him or by a licensing agreement with the carrier.

9. Fan Blogs (with Advertising)

Blogs (Web Logs or journals) are becoming ubiquitous on the internet. Although the bane of some in the sports industries, they have become a fixture in the sports landscape.127 They are a way for fans to express their opinions on a forum of their peers. Presently, various fans may have their own blogs where they can rant about every possible bit of minutia involving their team. Why not channel this by providing fans with the opportunity to post their thoughts on the team’s webpage? It would have to be a relatively open forum allowing fans to be critical of owners, players, and management alike. The owner, manager and players might occasionally post their own thoughts on this blog, thus encouraging fans to frequently check in to see who is saying what. By channeling fans onto the team’s own, free blog, the team could then sell advertisements and merchandise on its blog page.

10. Gaming

Professional sports and gaming present a paradox. On one hand, professional sports benefit indirectly from gaming in that placing wagers on outcomes of games and other events increases brand awareness and fan interest. On the other hand, direct involvement between the leagues and gaming establishments may call into question the integrity of the game, price shaving, throwing a competition, etc. From a revenue generating perspective, however, gaming is the proverbial “elephant in the room.” Gaming must be addressed in a careful, deliberate manner, eschewing hyperbole and “parades of horribles.” There are many ways in which both the integrity of the game may be preserved and revenues from gaming enjoyed by professional sports teams. It really is just a matter of time.

A common approach may be the simple raffle. A team could raffle off choice sideline seating, a court or dugout presence, ride a team flight or bus, or toward an even bolder step, a chance to call a play. To be sure, there would be substantial push back. But there is with any innovation.

….

A professional sports league could run the same program, partnering with a state, an Indian tribe, or the federal government through a national lottery. It could even earmark a large percentage of revenue to its charitable foundations. Thus, there are ways by which a league could limit its operational involvement in the gaming activity. Ultimately, gaming provides new opportunities for revenue growth, expansion of the fan base, content for advertising, and a new way by which fans may experience a game.

[Ed. Note: Author’s discussion of fantasy leagues is omitted.]

….

V. OBSERVATIONS

….

The coming revolution in revenue is like the runners at second and third—ducks on the pond, golden opportunities if one acts thoughtfully and boldly. The real question is whether the leagues pick up the runners. If they execute properly, we can all come out winners; if not, they will continue a revenue slide as other forms of entertainment compete for our dollar. The key is an understanding of two fundamental drivers: (1) content is everything, and (2) technology (including, but not limited to the Internet) delivers content. Those that can develop a revenue model that integrates both drivers will succeed.

Only the most naive would reject the notion that new technologies have changed the game and the way fans experience the game. The Internet, just one ubiquitous example of the new technologies saddling up to the sports industry, has done more than change sports—it has transformed sports. Not only is the Internet a vehicle for online retailing of merchandise and a stage for advertising, it is also one’s own highlight vault and mirror into the experience of professional sports. With the advent of the Internet and its accessibility through the worldwide web, the sports industry has mutated. Sports are no longer sports plus the Internet; they are a whole new industry—“new, interactive sports.” Those business competitors that recognize this seismic shift will be able to position their teams, league, or organization to reap the advantages of the new technologies and the new markets. Those that do not, will fail. Ducks on the pond, indeed.

Notes

1. Craig Lambert, Has Winning on the Field Become Simply a Corporate Triumph?, HARV. MAG., Oct. 2001, available at http://www.harvardmagazine.com/on-line/09014.html.

2. Id. The reader will notice that in this article, the National Hockey League (NHL) has been left out …

3. Sports teams also provide an opportunity for state and local taxing authorities to grow their respective tax bases. For example, in a financial report prepared for the Minnesota State Legislature on sports activity conducted at the Metrodome (NFL Minnesota Vikings, MLB Minnesota Twins, and Big Ten University of Minnesota Gophers football), the following taxes are collected: (1) sales tax on food and alcohol; (2) 10% ticket tax (including complimentary tickets) and 6.5% state sales tax on tickets (in addition to the 10% ticket tax); (3) 6.5% gross receipts tax on merchandise licensed by professional and collegiate sports teams; (4) personal income tax paid by visiting teams; (5) lottery games with a sports theme; and (6) tax on rental vehicles in the Metro area. See Paul Wilson & Mary Jane Hedstrom, Appendix C: Summary of Revenue Sources, Minn. Leg. (January 31, 2002) (on file with author). See also I.R.S., Sports Franchises, Market Segment Specialization Program Training 3123-005 (8-99); TPDS No. 839831 (on file with author).

4. Sports is big business in the United States and internationally. The Sports Industry, Bus. & Econ. Research Advisor (BERA) (2005), http://www.loc.gov/rr/business/BERA/issue3/issue3_main.html.

5. To say that the sector is well known is not to suggest that the sector is static. On the contrary, the sports sector is dynamic. For an excellent book on the evolution of the modern sports industry that includes discussions on sponsorships, franchise relocation, radio and television, stadium issues, and endorsements, see PHIL SCHAAF, SPORTS, INC.: 100 YEARS OF SPORTS BUSINESS (2004). See also THE ECONOMICS OF SPORT VOLUME I (Andrew Zimbalist ed., 2001) (covering many aspects of the business of sports).

6. See generally WILKOFSKEY GRUEN ASSOC., GLOBAL ENTERTAINMENT AND MEDIA OUTLOOK: 2005–2009: FORECASTS AND ANALYSIS OF 14 INDUSTRY SEGMENTS (6th ed. 2005).

….

14. I.R.S., supra note 3.

15. See National Football League website, www.nfl.com (last visited May 31, 2006).

16. The Business of Professional Football, Bus. & Econ. Research Advisor (BERA) (2005), http://www.loc.gov/rr/business/issue3/football.html.

….

26. The Business of Professional Football, supra note 16.

….

28. See Soonhwan Lee & Hyosung Chun, Economic Values of Professional Sports Franchises in the United States, 5 SPORTS JOURNAL (2002), available at http://thesportsjournal.org/2002Journal/Vol5-No3/economic-values.htm.

29. The Business of Professional Football, supra note 16.

….

31. The current agreement with the NFL is an eight-year contract that totals $17.6 billion. Kagan, supra note 25, at 45. About 65% of all revenues of NFL teams are from television rights licensing. Lee & Chun, supra note 28.

32. Lee & Chun, supra note 28.

33. The Business of Professional Football, supra note 16.

….

35. Kagan, supra note 25, at 64.

36. The Business of Professional Football, supra note 16.

….

45. Major League Baseball, www.mlb.com (last visited June 5, 2006).

46. … For interesting treatments of the business of baseball, see Andrew Zimbalist, May the Best Team Win: Baseball Economics and Public Policy (2003); Fred Claire with Steve Springer, My 30 Years in Dodger Blue (2004); Charles P. Korr, The End of Baseball as We Knew It: The Players Union, 1960-81 (2004); Fay Vincent, The Last Commissioner: A Baseball Valentine (2002); Marvin Miller, A Whole Different Ball Game: The Inside Story of the Baseball Revolution (2004); John Helyar, Lords of the Realm (1995); Stefan Szymanski & Andrew Zimbalist, National Pastime: How Americans Play Baseball and the Rest of the World Plays Soccer (2005).

47. Abner Doubleday, BaseballLibrary.com, http://www.baseballlibrary.com/baseballlibrary/ballplayers/D/Doubleday_Abner.stm (last visited July 25, 2006).

48. Reds Timeline History Highlights, http://mlb.mlb.com/NASApp/mlb/cin/history/timeline1.jsp (last visited July 25, 2006).

49. National League, http://www.ringsurf.com/info/Sports/Baseball/National_League/ (last visited July 25, 2006).

….

57. See generally Richard C. Levin et al., THE REPORT OF THE INDEPENDENT MEMBERS OF THE COMMISSIONER’S BLUE RIBBON PANEL ON BASEBALL ECONOMICS (July 2000).

58. Baseball, USA Today Baseball Weekly.com, Dec. 5, 2001, http://www.usatoday.com/sports/baseball/stories/2001-12-05-focusexpenses.htm.

….

60. Tim Reason, Squeeze Play, CFO.com, Apr. 1, 2004, http://www.cfo.com/article.cfm/3012785?f=search Baseball, USA Today Baseball Weekly.com, http://www.usatoday.com/sports/baseball/stories/2001-12-05-focusexpenses.htm.

61. Id.

62. Id.

63. Lee & Chun, supra note 28.

….

68. National Basketball Association, www.nba.com (last visited July 28, 2006).

….

77. Lee & Chun, supra note 28.

78. Kagan, supra note 76, Executive Summary.

….

88. See Reason, supra note 60.

89. Id.

90. Id.

91. Id.

92. For an interesting take on luxury suites, see Lambert, supra note 1.

93. Lee & Chun, supra note 28.

94. Id.

95. Id.

96. Id.

97. Id.

….

103. Lee & Chun, supra note 28.

104. Id.

105. Wilson & Hedstrom, supra note 3.

106. Id.

….

109. Horrow, supra note 81.

….

112. Horrow, supra note 81.

113. Id.

114. Id.

115. Id.

116. Id.

….

122. See Darren Rovell, The Tangled Web of Sports and Advertising, Espn.com, May 6, 2004, http://sports.espn.go.com/espn/sportsbusiness/news/story?id=1795742; Spiderman Bases Shot Down, USAToday.com, May 6, 2004, http://www.usatoday.com/sports/baseball/2004-05-06-spider-man-plan-dropped_x.htm.

….

125. See Interactive TV: The Opportunities for Sport, available at http://www.sportbusinessassociates.com/sports_reports/interactive_tv.htm (last visited June 6, 2006).

126. Global Interactive Sports TV Revenues to Increase, Indiantelevision.com, http://www.indiantelevision.com/headlines/y2k3/mar/mar92.htm (last visited June 6, 2006).

127. See, e.g., Sports Illustrated, Blog Central, http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com (last visited June 6, 2006).

….

IMPACT OF STAR PLAYERS ON GATE RECEIPTS

STARS AT THE GATE: THE IMPACT OF STAR POWER ON NBA GATE REVENUES

David J. Berri, Martin B. Schmidt, and Stacey L. Brook

Competitive balance in professional team sports has been the subject of numerous theoretical and empirical publications. The theoretical literature argues competitive imbalance, or the on-field domination of one or a small number of organizations, reduces the level of uncertainty of outcome and consequently reduces the level of consumer demand.1 The empirical literature, whether examining game day attendance2 or aggregate season attendance,3 has also generally confirmed a relationship between uncertainty of outcome or competitive balance and demand for tickets to sporting events.

Decision makers in the professional sports industry have not needed economists to understand this basic relationship. Virtually from the inception of organized sports in North America, leagues have enacted various institutions to promote competitive balance.4 Such institutions include the reserve clause, the rookie draft, payroll caps, salary caps, revenue sharing, and luxury taxes. Despite the similarity of effort, professional team sports leagues continue to have varying degrees of competitive balance.

The variability of competitive balance across professional team sports was illustrated by Quirk and Fort (1992). One of the findings of this seminal work, extended by Berri and Vicente-Mayoral (2001) and Berri (in press), was the relative lack of competitive balance in the National Basketball Association (NBA). The relative imbalance continued in spite of the NBA’s institution of a rookie draft, payroll caps, revenue sharing, free agency, and, at times, a reserve clause. By virtually any measure, the NBA has been unable to achieve the level of competitive balance observed in the other North American professional sports leagues.

The purpose of this article is not to examine why the NBA is competitively imbalanced but rather to examine the impact competitive imbalance has on consumer demand for the NBA product. The works of Knowles, Sherony, and Haupert (1992) and Rascher (1999) found that Major League Baseball attendance was maximized when the probability of the home team winning was approximately .6.5 These studies suggest that consumers prefer to see the home team win but do not wish to be completely certain this will occur prior to the game being played. For fans of NBA teams located near the bottom of the league rankings, though, the opposite is often true. Not only is their team not likely to win, but often the fan is quite certain of this negative outcome. The question is therefore “How do these NBA teams still maintain demand in the face of the certainty of an unwelcomed outcome?”

One possible strategy is for teams to shift their focus from the promotion of team performance to the promotion of individual stars. Hausman and Leonard (1997) found the presence of stars had a substantial affect on television ratings, even after controlling for team quality. Although this work also considered the effect stars had on team attendance, the inquiry into team attendance was “less formal” (p. 609). In essence, these authors only looked at how attendance changed when a team either added or played one of the stars these authors identified.

An objective of the present work is to extend the work of Hausman and Leonard (1997) in a more comprehensive study of the relationship between team attendance and both team performance and the team’s employment of star players. The structure of the study is as follows: The following section details the empirical model we will utilize to examine the demand for professional basketball. This discussion is followed by a review of the econometric estimation of the aforementioned model. The final section offers concluding observations.

THE DATA TO BE EMPLOYED

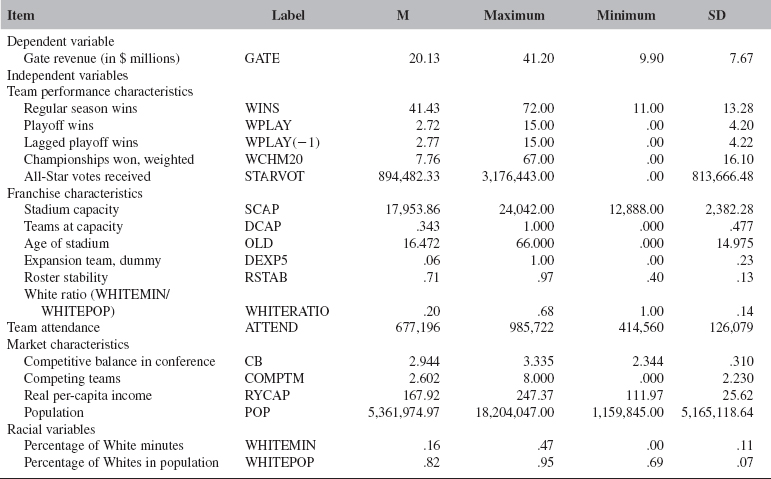

Given rudimentary consumer theory, demand is primarily determined by three factors: team performance, franchise characteristics, and market characteristics. The literature on attendance in professional sports has turned to a variety of factors designed to capture these primary determinants of demand. Table 11 lists our choice of dependent and independent variables. In addition to listing the variables and the nomenclature we employ, we report the hypothesized effect of the independent variables and corresponding descriptive statistics. We follow with a brief review of the theoretical reasoning behind this chosen list of factors.

Consumer Demand

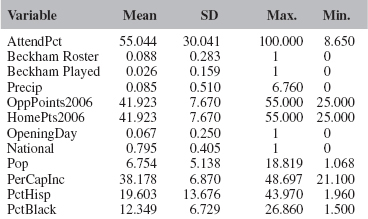

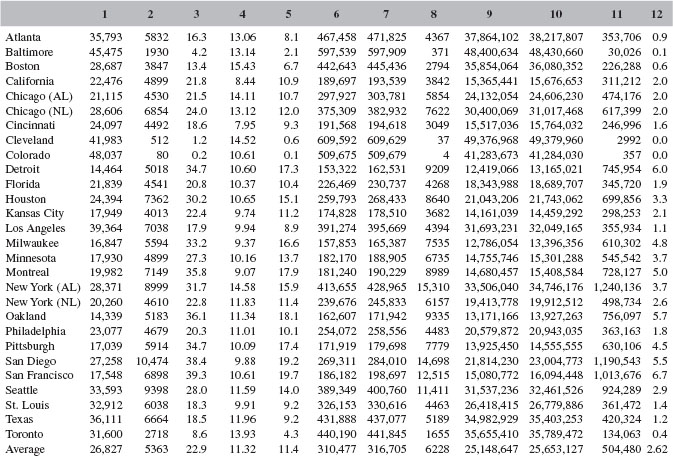

The data utilized to tabulate the variables listed in Table 11 comes from four seasons, beginning with the 1992–1993 campaign and concluding with the 1995–1996 season.6 A common practice within the professional team sports literature is to utilize aggregate attendance data as the dependent variable in a study of consumer demand. Over the period our study highlights, though, such a choice is problematic. Specifically, if one compares the reported attendance figures to the maximum attendance the stadium capacity of these teams would allow, one would note that of the 108 teams considered, 43 teams, or 40%, sold out every single home game. Given the divergence between attendance and demand, we employ gate revenue7 as a proxy for the level of consumer attraction to professional basketball.8 The use of gate revenue incorporates price adjustments and therefore allows for full variation in the dependent variable.9

Team Performance

The most common measure of team performance is regular season wins. Team performance can also be captured via playoff wins, lagged values of both regular season and playoff victories, and past championships won. Following Berri and Brook (1999), the effect of past championships is estimated via… calculation involved assigning a value to a team for each championship won in the past 20 years. This value was 20 if the team captured a championship during the prior season, 19 if the championship was won two seasons past, and so forth.10