CHAPTER THREE

INTRODUCTION

This chapter takes a brief look at sports leagues based outside of the United States as well as further introducing the reader to concepts of interaction related to leagues based in different countries. Many of the issues related to ownership and leagues discussed in Chapters 1, 2 and 5 are relevant here. In fact, apart from variations in scale, the broad concepts relating to the importance of issues such as centralized governance, revenue sharing, integrity, and agents are very similar. It is the unique product and delivery distinctions that must be examined in order to understand the best business practices for leagues around the globe.

The first article, “Local Heroes,” provides an overview of sports labor markets around the globe. It takes an introductory look at how the various sports leagues are becoming more assertive in finding labor for their teams, no matter the country of origin of the athlete. In the United States, this is seen most clearly with the increased number of foreign-born players playing in MLB, the NHL and the NBA. There is certainly an increasing number, although still quite modest, in the NFL as well. Globally, in soccer the use of foreign players has long been present, with South American powerhouses Brazil and Argentina being a major provider for European-based clubs. Over the past decade or so, the African continent has been a provider of global soccer talent as well.

The next two articles look at the sport of cricket. “Cricket in India: Moving into a League of Its Own,” examines the origins of the Indian Premier League and the commercialization of the game in that country, which in some ways has mimicked the commercialization of sports taking place around the globe. The inaugural season was played in India to largely positive reviews as an entertaining version of the sport. The article examines the thinking and buildup behind that first season. A business decision was made to play the 2009 season in South Africa due to security concerns after the terrorist attack in Mumbai. That season, too, received positive reviews, and the entity has returned to India. This is an interesting example of a sports enterprise seeking success on multiple continents, albeit not necessarily by choice.

That second article on cricket, “Twenty20 Cricket: An Examination of the Critical Success Factors in the Development of Competition,” examines an even more dramatic development related to this classic sport. Twenty20 cricket is essentially a shorter, faster, and potentially more commercially viable version of the game. The article provides valuable insights in contemplating revisions to sports to seek a broader audience. It takes a close look at various marketing studies on the changes made to cricket and the success achieved.

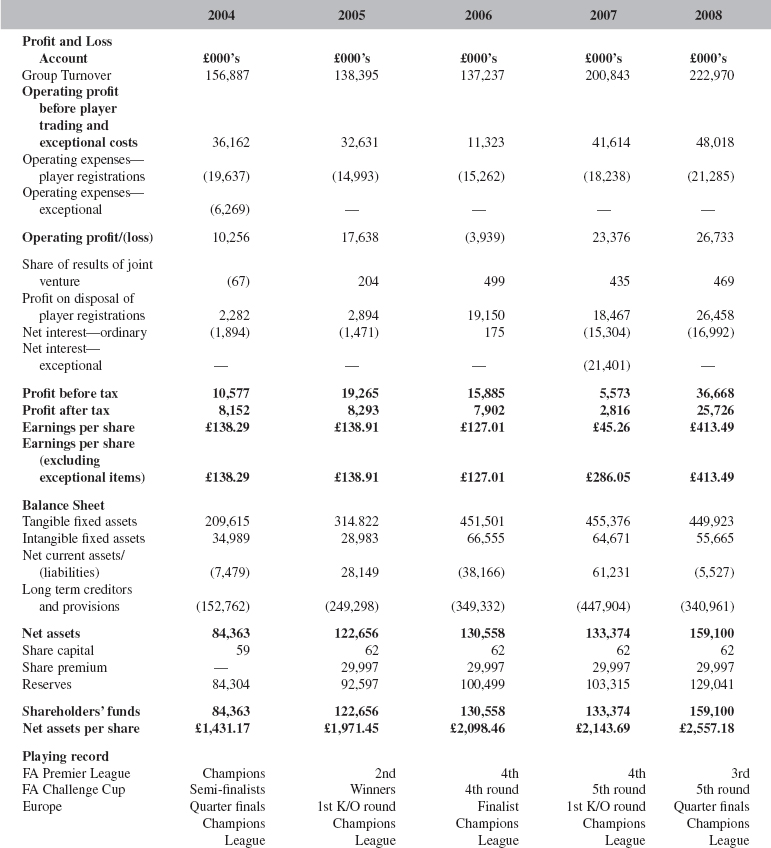

The next excerpt is from Arsenal Football Club’s 2008 Annual Report. It provides a “micro” look at the global side of sports by looking at the finances of one of the top clubs in what is widely recognized as the best soccer league in the world, the English Premier League (EPL). According to Deloitte’s “Annual Review of Football Finance,” covering the 2007–2008 season, the EPL’s 20 clubs generated revenues of EUR 2.4 billion in 2007–2008, while its closest European competitors—Spain’s La Liga and the Germany’s Bundesliga—generated EUR 1.4 billion each, followed by Italy’s Serie A, with just under EUR 1.4 billion, and France’s Ligue 1, with EUR 1.1 billion. EPL revenues can be segregated into three categories: broadcasting of EPL and Champions League matches (accounting for 48% of the total revenues); match-day revenues, such as gate receipts and concessions (29%); and commercial revenues, including advertising and sponsorships (23%). Like their U.S. counterparts, the European leagues’ biggest expense is player salaries, accounting for 62% of EPL revenues in 2007–2008. The highlights of Arsenal’s Annual Report presented here provide the reader with a good overview of the finances of most of the leading global soccer clubs and delivers a good introduction to, and comparison of, a European team’s revenues with North American–based franchises. The 2009 Annual Report was published too late to be included in this book, but it does provide additional insight into the impact of the global recession on a high profile club. For a broader “macro” picture of soccer finances, the reader might examine additional highlights from Deloitte’s “Annual Review of Football Finance,” which is available at http://www.deloitte.com/assets/DcomUnitedKingdom/Local%20Assets/Documents/Industries/UK_SBG_ARFF2009_Highlights.pdf.

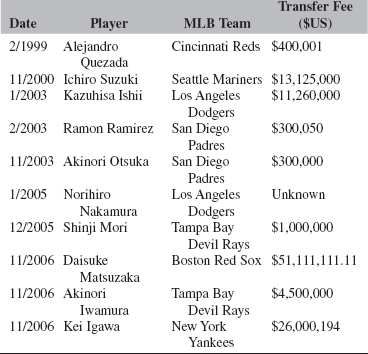

The final article in this chapter, “The Impact of the Flat World on Player Transfers in Major League Baseball,” looks more deeply at the global labor market, with a focus on the interactions of the player markets in the United States and Japan. It also looks at player transfer rules in other sports, as well as how the rules used in baseball might be improved. In reading this article, it is important to reflect on the rules of interaction that leagues around the globe must develop as the labor market flattens out for the players and they more readily view globally competing leagues as options.

OVERVIEW

LOCAL HEROES

Sporting Labour Markets Are Becoming Global. But What About Sports Themselves?

The Economist

The weather is perfect, with just enough breeze to freshen a warm June [2008] evening. Shea Stadium is bubbling this Friday night, with fans and food vendors, music and pregame presentations. On the big screen the New York Mets introduce themselves: Jose Reyes, shortstop, from the Dominican Republic… Carlos Beltran, centre fielder, Puerto Rico… Endy Chavez, right fielder, Venezuela… Oliver Perez, pitcher, Mexico. Mets fans have had a frustrating season, with rather fewer wins than losses. By Tuesday, the team’s manager will have been fired. But tonight they leave Shea unusually content. The Mets beat the Texas Rangers 7-1. Mr. Perez pitches solidly and bats in two runs. Mr. Beltran and Mr. Chavez both score one and bat one in. The speedy Mr. Reyes scores two and steals his 24th base of the year.

What is not unusual is the Mets’ cosmopolitan makeup: six of the nine starters were born outside the United States. The Mets are a prime example of the globalisation that has swept through sport’s labour markets in recent years. Now many sports are trying to pull off a more difficult trick: globalising their product markets too.

Start, though, with labour—and with baseball. In recent seasons, the proportion of players in the major leagues who were born outside America has been nearly 30%, up from 20% ten years ago. Dominicans are the biggest group, followed by Venezuelans. There are several Japanese players, and New York’s other team, the Yankees, has a star Taiwanese pitcher.

In the minor leagues the proportion is even higher: close to half. Among the legionnaires is Loek van Mil, a Dutch pitcher who stands 2.16 metres (7′ 1′) tall. If he fails on the mound, he might want to join Mr. Yao playing basketball: in recent years foreigners have accounted for around 80 of the 430-odd players on the NBA’s rosters. In ice hockey, North Americans no longer think Europeans too weak, with sticks or fists, for the NHL. Over 30% of NHL players come from outside America and Canada. This year’s [2008] Stanley Cup winners, the Detroit Red Wings, were captained by Nicklas Lidstrom, a Swede and one of 13 Europeans in a 28-man roster.

In other sports a global labour market may seem less of a novelty. English cricket has long relied on the old empire. In football, the Italian and Spanish leagues were graced by several fine foreign players in the 1950s and early 1960s. Both countries then banned foreigners in the hope of helping their national teams. Spain’s ban was lifted in 1974 and Italy’s in 1980.

Thirty years ago, when Tottenham Hotspur, a London football club, signed two members of Argentina’s World-Cup-winning squad, English fans marvelled at such boldness. Now imports are so common that FIFA and UEFA, the governing body in Europe, would like to cap them, but under European Union labour law players must be able to move freely between member states. The transformation in England, with the richest television contracts in the sport, has been remarkable. More than half the players in the Premier League are from outside Britain, up from one-quarter ten years ago. English clubs employed almost one-eighth of the players in the Euro 2008 tournament this June, even though the national team failed to qualify. Only German clubs were better represented.

The supply side of football’s labour market has shifted too. Brazil has long been a big exporter. Most of the clubs in this year’s Asian Champions League, for instance, have at least one Brazilian. Over the past decade or so there has been a scramble for Africans. French and Belgian clubs had been using Africa as a cheap source of talent for years, but lately the English have been keen buyers, often via Belgium or France, of such talents as Ghana’s Michael Essien and Togo’s Emmanuel Adebayor.

Ten years ago just under half the players at the African national championships played in their own leagues and two-fifths were with clubs in Europe. Of the 146 men involved, 41 worked in France and only three in England. At this January’s [2008] tournament, less than one-third were with domestic teams, mainly in North Africa. Well over half were working in Europe: 202 in all, 57 of them in France and 41 in England.

Virtuous Circle

It is not surprising that sport’s labour markets are globalising. The most talented people are gravitating towards the richest employers, whose ability to pay has been enhanced further by juicy television contracts. In turn, the best players make the sport more enjoyable to watch, bringing in more fans and more revenue.

The television money and fan base attract capital too. The globalisation of sport’s capital markets may not have gone as far as that of its labour markets, but it is under way. Several English football clubs are owned by foreigners, among them owners of American baseball and football franchises. In cricket, one franchise in the Indian Premier League has owners based in Australia and Britain.

Now several sports—and sports leagues in particular—are trying to expand their product markets beyond their borders as well, by staging games abroad. This is easier said than done. Sport, says Andrew Zimbalist, an economist at Smith College in Massachusetts, is different from other industries: “You can’t produce your product in one country and sell it in another. You can do it with laptop computers, but you can’t do it with a game.”

It is possible to export sport indirectly, by selling media rights. Most globalising leagues hope to make their money from fans in front of television sets rather than inside stadiums, and games abroad are one way of building a brand. But it may not work, because local loyalties matter. “It’s hard to get people interested in a baseball team on the other side of the world,” Mr Zimbalist says. “It’s an emotional thing.”

There are other potential obstacles. American football, for example, is not played much outside America and requires a lot of explaining. Soccer needs no introduction, but any league wanting to expand abroad faces another problem. Under FIFA rules it needs the permission of the national association of its host country. That association may well want to protect its own league from imports.

None of this is putting off prospective exporters. “US sports are rushing to get first into globalisation,” says David Stern, commissioner of the NBA. All of them, he explains, try to make money in roughly the same ways: by staging events, including games; by building television audiences; through digital media; through marketing partnerships; and by selling merchandise. European football and its top clubs are doing much the same thing, with the English to the fore.

Would-be globalisers have a success story to ponder: F1 motor racing, which has been stretching from its old haunts in western Europe, the Americas and Japan towards the fast-growing economies of the Middle East and Asia. This year the United States Grand Prix (GP) was dropped from the calendar. One race is scarcely enough to compete with NASCAR, and other countries have been eager to get their own GPs.

A Malaysian GP was added in 1999; races have been held in Bahrain and China since 2004 and in Turkey since 2005. In September the first Singapore GP—and the first F1 race at night—is due to take place. India, which already has an F1 team, is due to stage its first GP in 2010. According to Bernie Ecclestone, F1’s boss, races in Russia and South Korea may follow.

“We go where the markets for the manufacturers are,” Mr. Ecclestone noted last year, “where they are going to sell their cars in the future.” The sponsors whose logos festoon the cars and drivers’ firesuits are doubtless pleased to see the sport spreading around the world. And there are no protective local federations to worry about. On the contrary, more countries seem to want the glamour of their own GPs than can be fitted into the calendar.

On the face of it, American football has much in common with F1. It already has dedicated fans in its main target market (Europe, and chiefly Britain). It is seen as an upmarket sport. The NFL faces no protected competitors abroad, and its product is scarce. The NFL’s 32 teams play only 16 regular-season games each; those that reach the Super Bowl play a further three or four. Almost all games sell out. Ten teams have a 25-year waiting list for season tickets.

HOW TO GO GLOBAL

One big difference, though, is that F1 is already a global sport, whereas American football is not, and past efforts at exporting it have stuttered. Lots of exhibition matches have been played. In the 1990s the NFL set up a European league, which is now defunct. It has decided that there is no point in offering second-rate fare. “It’s got to be the NFL,” says Mark Waller, the Briton who oversees the NFL’s international operations. “It can’t be the European league.”

So last October [2007] the NFL went to Wembley Stadium in London, where the New York Giants (eventual winners of the Super Bowl) beat the Miami Dolphins 13-10. This year [2008] it will bring the New Orleans Saints and the San Diego Chargers to Wembley. Last year’s game was a sell-out. When tickets went on sale this May, 40,000 were snapped up within 90 minutes.

Though a great treat for Londoners, the NFL’s jaunts abroad are less fun for fans of the “home” team (the Dolphins last year, the Saints this time). Unless they can afford a foreign trip, they must forgo one of only eight regular-season home games. Mr. Waller admits this is a problem. “We’ve got to find a way to get more games,” he says. His preference would be to add an extra game for everyone, to be played on neutral ground. That would be fair on all the teams, and there would be 16 games to be spread around: perhaps in Toronto (where the Buffalo Bills are already due to play once a season), Mexico City (where a game was staged in 2005) or American cities without an NFL team, as well as London. New venues might see four games a year.

Meeting pent-up demand in America may prove easier than generating new interest abroad. Still, the test for the NFL is whether live games bring in more British enthusiasts who will stay with the sport. To fans, the game’s technicalities are part of the attraction. The problem is to get newcomers hooked. The NFL has always used television inventively, and Mr Waller thinks that high-definition television, in combination with its website, can help to explain the game to newcomers by getting them close to the stratagems and the sweat. “The only way you could do that before was to get on a field. You can do that all digitally,” he says.

MLB and the NHL may be luckier, in that they have more games to spare and are preaching to the converted. The NHL plans four regular-season games in Prague and Stockholm at the start of next season. MLB first went abroad in 1999, to Mexico. This season began with a series between the Boston Red Sox and the Oakland Athletics in Tokyo. Next year [2009] will see the second World Baseball Classic, a sort of baseball world cup, in which many MLB players take part.

Mr. Stern’s NBA played regular-season games in Japan 18 years ago. Now, all its foreign games are friendlies. Yet it may be best placed of all the ball-playing organisations to build a business abroad—notably in China. Basketball is already popular, roughly on a par with football, according to CSM Media Research in Beijing. It is also simple to play, and the Chinese government has a five-year plan to put a basketball court (and a table-tennis set) in every village. The Olympic baseball stadiums in Beijing are only temporary structures. The nearby basketball arena is anything but.

HOME-GROWN ATTRACTIONS

Better still, in Mr. Yao the NBA has a local hero who draws in viewers by the million. It also has another Chinese star in Yi Jianlian, now of the New Jersey Nets. Its games are shown on CCTV’s main free sports channel and it has another 50 television deals in the country. Not everything is predictable: during the three-day mourning period for the Sichuan earthquake, CCTV took the NBA playoffs, along with other forms of entertainment, off the air and resumed coverage only slowly afterwards—albeit in time for the finals. Earlier this year the NBA sold 11% of its Chinese subsidiary to a group of five investors, including ESPN, for $253m. Eventually, thinks Mr. Stern, there may be potential for the NBA to form a partnership with a Chinese enterprise to launch an NBA-affiliated league. Expansion to Europe is also on the horizon.

Of all the leagues with grand globalisation plans, the Premier League has probably caused the most fuss. Its Asia Trophy has been staged every other year since 2003. Now it is wondering how to expand its activities abroad. Earlier this year Richard Scudamore, the league’s chief executive, floated the idea of an “international round”, to be played in the middle of the season, in which all 20 teams would play an extra league match abroad with points at stake. This caused uproar.

One reason was that English fans cherish the symmetry of their football leagues: every team plays every other one twice, once at home and once away. The international round would upset that symmetry. (American sports leagues, by contrast, typically have unbalanced schedules.) Secondly, the Premier League has to deal with foreign football associations. Perhaps taking umbrage at the lack of warning, the Asian Football Confederation (AFC)—a potential host—said it did not like the idea of the English inviting themselves over. However, it has since softened its tone, saying that the Premier League would be welcome after all.

Mr. Scudamore explains that things are still up in the air. “All the clubs agreed to take a look at this over a long period,” he says. “The clubs are still keen to see us developing some kind of international strategic play. I sit here not knowing in what variant it will come back, but it will come back.” One selling point for some of them may be that foreign games will help financially to even up a lopsided league in which the top four are entrenched. Unlike domestic television revenues, foreign fees are shared evenly among the clubs.

In China, potentially the biggest market, the Premier League lacks the draw of a local star. Zheng Zhi, captain of the Chinese national team, does play in England—but his club, Charlton Athletic, was relegated from the league in 2007. The only Chinese player in the Premier League last season, Sun Jihai of Manchester City, started a mere seven games. He has just moved to Sheffield United, one level below.

Some have also questioned the wisdom of selling television rights for the three seasons to 2009–10 to WinTV, a pay-television company. Mr. Scudamore says that WinTV won a tender fair and square, and that it is “doing well from a low base”. WinTV says that since it started to show English football its subscriber base has increased “significantly”, to nearly 2.5m (some buying its channels singly, others as part of a package). It expects the number to double in 2008–09. People also mocked the sale of domestic rights to BSkyB when the league started, Mr. Scudamore says—and look how that turned out.

“If they are going to be interested in sport,” Mr. Scudamore says of potential fans in emerging economies, “we hope they’ll be interested in our sport. If they’re going to be interested in our sport, we hope they’ll be interested in us.” Most would-be exporters of sporting spectacles would no doubt say the same. They offer sport of the highest quality, whereas the standard of play in local leagues is often pretty ropy. But quite possibly, those fans, just like those in America and Europe, will eventually prefer to see their own local teams—the more so as standards improve.

Already, notes Seamus O’Brien, chief executive of World Sport Group, a sports-marketing firm based in Singapore, games involving national football teams draw far bigger audiences in Asia than do matches beamed from Europe “in the middle of the night”. Mr. O’Brien, who counts the AFC among his clients, thinks Asian football associations should treat the game at club level as an infant industry. They should shell out cash on bringing in foreign players—as Western sports have been doing for years, and as Major League Soccer did to bring Mr. Beckham to America. He proposes that South-East Asian countries pool resources to form their own regional super-league, which would be stronger than national competitions. There is money to pay for this: the second-placed bids for Premier League football rights in Asia, he says, amounted to $600m.

Eventually, believes Mr. O’Brien, “Chinese football will be bigger in England than English football is in China,” because the number of Chinese expatriates wanting to watch games from back home will outnumber their English counterparts. That may be some time off. But in the sports business developed countries no longer call all the shots. The strongest evidence for that comes not from baseball, basketball or football, but from another of the world’s great games: cricket.

CRICKET

CRICKET IN INDIA: MOVING INTO A LEAGUE OF ITS OWN

India Knowledge@Wharton

Corporate cricket in India has never been of a particularly high standard. At the bottom end of the leagues, companies form makeshift teams from their own ranks. Anyone who has ever wielded a bat is enlisted to play. You bat a bit, bowl a bit and then disband for beer. (The demon bowler who could mess up the proceedings by being too “professional” is given beer before the match, not after.) “Save for Mumbai teams … inter-corporate matches in India have never been very serious,” says Sandeep Bamzai, the author of Guts and Glory: The Bombay Cricket Story.

Come April 18 [2008], it will be a different ballgame. Eight companies are vying for top honors in the Indian Premier League (IPL). They include Mukesh Ambani’s Reliance Industries, Vijay Mallya’s UB Group, India Cements, GMR Holdings, filmstar Shah Rukh Khan’s Red Chillies Entertainment, and some makeshift alliances such as actor Preity Zinta and Ness Wadia, joint managing director of Bombay Dyeing, a leading textile manufacturer. These companies and combines have bid for and won franchises for eight major Indian cities. The tournament, to be played over 44 days in a 20-overs-a-side (Twenty20) format, will pit these eight teams against one another.

The marketers have already swung into action. The Bangalore team—owned by Mallya—has been named Royal Challengers, after one of the liquor baron’s popular whisky brands. Khan has called his Kolkata (formerly Calcutta) team the Knight Riders, “inspired by the phrase knight in shining armor.” The Chennai team, owned by India Cements, will be known as the Super Kings. (India Cements has brands such as Coromandel King.) Others, too, are rolling out elaborate plans.

They need to do that. By Indian standards, they have already paid large sums for these teams. The franchises for the eight cities were auctioned by the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI). The auction took place in an extravaganza worthy of a Twenty20 match. Against a floor price of $50 million, Ambani won Mumbai with a bid of $111.9 million. Other winners included Mallya (Bangalore; $111.6 million), Hyderabad (Deccan Chronicle; $107.01 million), Chennai (India Cements; $91 million), Delhi (GMR; $84 million), Mohali (Preity Zinta and Ness Wadia; $76 million), Kolkata (Shah Rukh Khan; $75.09 million), and Jaipur (Emerging Media; $67 million). Incidentally, one of the losing bidders has offered to pay $130 million for a team if any of the franchisees is willing to sell. [The IPL added two teams in 2010, with expansion fees of $370 million for a team based in the city of Pune and $333 million for a team based in Kochi.]

GOING, GOING…

The payment for the teams was just the beginning. That auction was followed by bidding for the players. The best cricket players from all over the world were up for grabs. The top bid was for India’s Twenty20 and one-day cricket captain, Mahendra Singh Dhoni, who went to Chennai for $1.5 million. Andrew Symonds of Australia was bagged by Hyderabad for $1.35 million. Other rounds of bidding are still on.

With each team needing 16 men (11 players, a 12th man and four reserves), the price tag will keep climbing. Team Hyderabad, for instance, has already paid some $6 million for 11 players and will need to fork over more for the rest. The bids would have been higher, but for the fact that some iconic players—former India captains Sachin Tendulkar, Sourav Ganguly and Rahul Dravid—weren’t available. They are captains of the cities they are associated with (Mumbai, Kolkata and Bangalore, respectively) and will be paid 15% more than the highest-paid player in their teams.

These fees for players are hardly unusual by international standards. For example, Forbes magazine estimates golfer Tiger Woods’ annual income at $100 million. But for cricket—and not just in India—this is big money. Australian Ricky Ponting, the highest-paid cricketer in the highest-rated country team, takes home only $800,000 a year. Sponsorships bring this up to $4 million.

These large deals are already attracting criticism. Left-wing political parties have demanded an investigation into the “sources of hundreds of crores of black money spent on the auction” and why the government has condoned such “outrageous gambling.” Not to be outdone, the right-wing Shiv Sena party has described the auction as the “gambling of industrialists.”

The auctions, though, are a small part of the money machine. The BCCI had earlier sold the 10-year television rights to Sony Entertainment, the Indian subsidiary of Japan’s Sony, and World Sports Group (WSG), an Asia-focused sports marketing and management agency, for more than $1 billion. Together with the other takings, IPL is already a $2 billion business. As Lalit Modi, BCCI vice-president and chairman and match commissioner of the IPL, says: “IPL is the best thing that has happened to cricket. Corporate India is convinced about the product and the revenue model and has shown the appetite and passion for cricket.”

MONETIZING THE GAME

Modi, scion of a business family that owns tobacco-maker Godfrey Phillips, is the new face of the Indian cricket establishment. He studied marketing at Duke University in North Carolina, where he learned about the major U.S. sports leagues. “We have succeeded in monetizing the game,” he says.

“Yes, priorities have changed for a segment of the population,” says Sridhar Samu, professor of marketing at the Indian School of Business (ISB), Hyderabad. Adds Bamzai: “Cricket today is a metaphor for change.” According to Ashish Kaul, executive vice-president of the Indian Cricket League (ICL), a rival to IPL: “We as a country have reached a stage where entertainment is a basic necessity and not a leisure activity. Cricket is the lowest common denominator of this country and perhaps the largest entertainer.”

Corporate India—in the form of the new cricket leagues—will give the fans all the change they want. The game in its Twenty20 format has metamorphosed a great deal from its traditional five-day test match version. The first innovation—the 50-over-a-side, one-day variety—offended the purist; Twenty20, for them, is sheer slam-bam. But so what? “People anyway watch only the last 20 overs of a one-day match,” says Modi. “We are giving them concentrated cricket, concentrated entertainment.”

The franchisees are working overtime to ensure that the new format works. In Hyderabad, Deccan Chronicle is talking about hiring special trains to bring in fans from the hinterland. The train ride will be an experience in itself, with marketing men salivating at the thought of such a focused and captive audience, which also has time on its hands during the journey. In Kolkata, Shah Rukh Khan is planning a special women’s stand, while he makes the occasional guest appearance. Meanwhile, the Delhi team has hired an Indian Institute of Management (Ahmedabad) alumnus, a 45-year-old former colonel in the Indian Army, as assistant vice-president (operations). Corporatization and professionalization are clearly the watchwords of the day.

The key question is: Will the IPL benefit all stakeholders? The cricketers certainly stand to gain; they are seeing the sort of money they could only dream about earlier. This is particularly true of countries outside the Indian subcontinent where cricket has not been such a passion. Elsewhere, cricketers have to compete with stars in football, rugby and so on. In India, for all practical purposes, there is money only in cricket.

There could also be casualties, such as English county cricket. Which players would want to spend a season there when there is so much more money in the IPL? “County cricket is a page in the history books,” says Bamzai. And, though the BCCI says it will fix IPL schedules in consultation with the International Cricket Council (ICC), there have already been fears that money may have changed power equations. Indian cricket today earns as much as the rest of the cricketing world put together.

….

WHY EYEBALLS MATTER

BCCI’s Modi is confident that people are bored with soaps and that IPL will be a huge draw. Not everybody is so sure. “This will only work if you get the eyeballs,” says Bamzai. “I am not too sure if IPL will.”

Kaul of ICL is another skeptic. (ICL was started by the Zee Group, a television major, and IPL is actually the official response from BCCI.) “Perhaps BCCI and IPL may not lose anything as they are just selling a commodity,” he says. “But will the market be able to afford the rates? IPL is just an inter-corporate tournament—in a way, Mukesh Ambani vs. Vijay Mallya with 1,500 seconds (of advertising time) to be sold.” By his calculations, Sony and WSG could lose almost $10 million in the first year.

The bigger question around getting the necessary eyeballs—and thus being able to charge high ad rates—is whether Indian audiences will develop loyalty towards city-based teams. State-level cricket matches in India draw no audiences and are largely ignored by television. Will audiences be passionate in their support for Mumbai, except while local hero Tendulkar is batting? Or is the whole IPL extravaganza a marketing exercise that will fizzle out after a few matches?

Modi argues that city-level cricket can succeed in India for several reasons. “The league has been designed to provide opportunities to upcoming cricket stars to showcase their talents while sharing a platform with some of the world’s best cricketers,” he says. “It will be the first time we have a Twenty20 format for our fans and the first time the game will pit a city against another city. It also marks the first time international players of the stature of Shane Warne, Sanath Jayasuriya and Ricky Ponting will participate in a domestic Indian league. Indian corporations and Bollywood actors will be involved. The cricket matches will be covered globally.”

“Marketing muscle and money will play a role,” agrees Krishnamachar of WSG. “But eventually, the real maturity will come from the television viewers who turn around and say that they want to watch the best cricket and that it doesn’t matter if it is India vs. Australia or something else.”

“It is not just marketing hype,” says Samu of ISB. “There is significant substance with top players in the teams. It is a good product which is now getting marketing support. Indian cricket is certainly headed in the same direction as football in the UK and baseball in the U.S.” He agrees, however, that it will be a challenge to get audiences to watch city teams, since they have ignored state-level cricket.

Samu disagrees with the politicians who have been complaining about the large sums being spent on cricket. “One should not think in terms of too much money going to cricket being detrimental for other sports,” he says. “In fact, it may work to the advantage of other sports. Cricket is now moving to a different league and the other sports could learn from it and follow in its footsteps. They could look at adapting the same formats.”

Former test cricketer Syed Kirmani has a suggestion. “Other sports should be taken care of,” he says. “If one sport is overflowing with money, it should distribute some to other sports.” BCCI is, in fact, doing just that. It has just announced that it will set aside $25 million for the development of other sports.

As D-day approaches, the excitement is building up. It is not just among fans. “There are already enquiries from private equity players to team-owners asking them if they would be willing to sell a share of the pie,” says Krishnamachar of WSG. Srinivasan of India Cements is talking about an initial public offer (IPO) and listing his team. “It’s going to be a great carnival,” says Kirmani.

TWENTY20 CRICKET: AN EXAMINATION OF THE CRITICAL SUCCESS FACTORS IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF COMPETITION

Christopher Hyde and Adrian Pritchard

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The Twenty20 cricket competition is a shortened, faster version of traditional four-day and one-day cricket. It was launched in England and Wales in 2003 in an attempt to reverse dwindling interest in the sport. Games were to be completed in three hours and were augmented with off-field entertainment.

The study reviews literature concerning the launch of new sporting products and services, and investigates the critical success factors behind successful launches and also factors that led to failures. Most of the research conducted has been in American and Australian sport, with academic models developed in these countries, particularly America. The authors believe the models to be useful, but felt there were likely to be differences in England and Wales because of the sporting culture and calendar.

Attendance figures were gathered from a number of sources to quantify the success of the competition in terms of spectator numbers. These clearly show that crowds are a lot higher for this form of cricket. A short open-ended questionnaire was developed from the literature review in order to investigate the likely critical success factors. This was then sent to the marketing departments of the 18 counties who participate in the competition.

The secondary research and the comments received from respondents identify a number of factors that were attributed to being critical to the success of the competition. These include the use of market research and the application of marketing techniques, media coverage, a reputation for being fast and entertaining, and the length of the game. These factors lie within the three strategic factors affecting the diffusion rate model.

However, the model excludes two important factors that are contextual to cricket: competition timing and the weather. There are two elements that respondents felt were important in the competition’s timing: that the games are at a convenient time for spectators to attend, and that they avoid competition from other sports, particularly football. The implementation of this timing strategy might have helped gain increased audience interest. Other contextual factors that were identified as impacting on diffusion and requiring further investigation are saturation, in terms of length of the competition, and crowd involvement.

The research was qualitative, and only industry experts from counties’ marketing departments were interviewed. The primary research did not take account of spectators’ opinions, and further research is recommended to obtain their views on the competition and the factors that motivate them to attend matches.

INTRODUCTION

The authors investigated the issues involved in making a new sport successful. What factors determine whether people are likely to attend a new sporting event and become interested in it? Compared to other forms of cricket, the competition appears to have been successful at bringing in spectators, but what have been the critical factors in this success?

BACKGROUND TO TWENTY20

Cricket in England and Wales is governed by the England and Wales Cricket Board (ECB). The 18 domestic counties receive income from the ECB, which generates its revenue from international cricket via the sale of tickets, merchandise and television rights. ECB turnover in 2004 was £75.12 million, up from £73.5 million in 2003. Cricket is highly dependent on broadcasting revenue, which represents 80% of ECB income. The counties are subsidised by the ECB, with some earning up to 75% of their income from the source. The size of the cricket market is considerably smaller than football, where in 2005/6 six English football teams alone had a turnover greater than £85 million, Manchester United being the biggest at £167.8 million.

The English county cricket season begins in mid-April and concludes in September. Before 2003 it consisted of one-day championship games (lasting up to eight hours per day) and one-day games (lasting between six and eight hours) depending on the competition played….

A proposal to improve interest in the game through the new Twenty20 competition format was put to the first-class counties forum in 1998. The idea of a reduced version of the game was snubbed, but in 2001 problems in the domestic game were still apparent (The Economist 2003) and attendances were falling (English 2003). A £200,000 survey was undertaken by the ECB in 2001 in an attempt to collate information as to how to satisfy customers, gain interest from a younger market and help the game as a whole. This was undertaken in three key phases. First, there was a complete examination of statistics throughout cricket, which were analysed to identify trends and patterns. This was followed by interviews with a wide cross-section of demographic groups. A mixture of current and potential spectators was involved in the process to gain a greater depth and knowledge of the target audience. The final part of the strategy involved a large random quantitative survey. A programme of 4,000 15-minute face-to-face interviews revealed that about two-thirds of the population either disliked or had no interest in cricket. Prominent among the rejectors were children, young people aged 16–34, women, ethnic minorities and members of the lower social strata.

The first-class counties agreed to a shorter form of the game, with the aim of attracting these rejectors. ECB marketing manager Stuart Robertson was responsible for the creation of the competition and the research programme. He believed it should be launched with the primary aim being that the competition is market-driven. It was therefore necessary to apply basic marketing techniques to cricket. The rules were not intended to be radically different, because it was hoped that it would be a stepping stone for people to watch the longer versions of cricket (Twenty20 official site).

Twenty20 was launched on 13 June 2003, and played by the 18 first-class counties in England and Wales. The counties were split into regional groups, with the winners of each group progressing to a finals day in July. In 2004, an additional quarter-final stage was added to increase the number of games.

The games were designed to last for approximately 2 hours 45 minutes, thus creating a shortened, fast paced version of the traditional one-day game. It was deliberately staged in the middle of June, the hottest month of the year and also the period with the longest daylight hours. Most games started at 5.30pm, the aim being to become a major summer social attraction targeting a younger post-work crowd and offering a great family evening out. Additional entertainment was featured in the form of music and interactive crowd events; £250,000 was spent on marketing but no sponsor was found. However, pay-TV operator Sky screened the competition on satellite television, and terrestrial broadcaster Channel 4 covered cricket in general with a half-hour Saturday morning programme throughout June and a live game on 14 June.

LITERATURE REVIEW

New product development is generally agreed to be risky for a variety of different reasons, and the majority of new products/services fail. Also, the degree of novelty in new products and services tends to vary. Booz et al (1982) classify new developments into four categories: product replacements, additions to existing lines, new product lines, and products that are new to the world. Twenty20 would probably be classified by the model as an ‘addition to the existing lines’ of four-day and one-day cricket. Others might classify it as a ‘new to the world product’ if it is viewed as a new sports activity (Harness & Harness 2007).

Rogers (1983) examined the speed of adoption of products and services citing the five characteristics: differential advantage, compatibility with customer values, complexity in terms of ease of understanding, divisibility in terms of ease of trying the product/service and communicability of the benefits. Though the model is a generic one, it can, to some extent, be applied to Twenty20 cricket. Differential advantage is in the form of the speed of the game, with the shorter duration being compatible with consumer values and easier to trial. The limited changes to the rules means that it is not complex (Twenty20 official site 2003). Bridgewater (2007) claims that the complex rules of cricket make it difficult to expand its appeal, and one-day cricket is not suited to trial because of the length of the game. Higgins and Martin (1996) considered diffusion in a sports context and formulated a model to assess the diffusion rates of sporting innovations. They claim that there are three components that affect the rate of acceptance:

• The characteristic of the innovation as discussed above (Rogers, 1983)

• The perceived newness of the innovation, be it a change in rules, location of the event or a combination of both

• Sources of influence used to communicate the idea (Mahajan et al, 1990a; Mahajan et al, 1990b). The authors did not comment on the extent to which changes in rules or location impact on likely success. However, Papadimitriou et al (2004) evaluated perceived fit in sports brand extensions in Greece. Their research provided support for the hypothesis that perceived fit is higher for sports-related extensions and results in a more positive evaluation and higher intention to purchase.

Twenty20 has been televised live by Sky on a subscription channel. The second day of the competition was also covered live on Channel 4 on free-to-air terrestrial television. The importance of television coverage in terms of finance, commercial rationale and organisational skills is generally accepted within the literature.

Garland et al (1999) investigated the marketing of cricket in New Zealand in the 1990s and the adoption of marketing techniques to meet customer requirements. New Zealand Cricket Inc conducted telephone interview research in 1991 to discuss the barriers to cricket. These were identified as ‘a boring game that takes too long to finish, with rules that are difficult to understand and in which New Zealand did not perform well’. Further problems identified were poor facilities, unruly behaviour at grounds, and a preference for television coverage. The research also made it clear that the barriers could be ‘circumvented’ by marketing strategies that made use of:

• The atmosphere of one-day internationals

• The more serene atmosphere of test matches

• The success of New Zealand teams

• The excitement of watching live sport

• National pride

• The quality of teams and individual performances.

After three years, the New Zealand Cricket Council was able to see increases in attendance, television ratings, media coverage and revenue. The authors claim that research shows there is a clear distinction in the customer profile in New Zealand between test match and one-day international supporters, though they offered no empirical evidence.

The authors went on to look at the launch of Cricket Max, a version of the traditional game—mainly intended for pay-TV audiences—that was launched by Martin Crowe, a former New Zealand captain, in 1996. Crowe’s rationale (Cricinfo, 1996) was to provide a game that was short, very colourful, kept some old traditions and highlighted the best skills in the game in three hours of cricket. It was launched with live satellite coverage and sponsorship from Pepsi Max and BNZ [Bank of New Zealand]. McConnell (2004) noted that it did not compete against the country’s number one sport, Rugby Union. In comparing factors in different hemispheres, he stated that the longer twilight conditions in England offered advantages that could only be matched in the South Island of New Zealand.

Cricket Max has not been played since 2001, although there has never been an official announcement as to why not. Some of the ideas of Cricket Max were borrowed by Twenty20, the three-hour time slot being probably the most significant.

Haigh (2007) argues that the most successful variations of the traditional game have been those that looked more traditional and kept rule changes to a minimum. Cricket Max made changes in numbers of players and scoring; Twenty20 has not. He argues that the promotion of Twenty20 as ‘being for those who do not like cricket’ is for this reason misleading.

Paton and Cooke (2005) used attendance figures to investigate spectator numbers at domestic one-day and four-day games in England and Wales. The findings demonstrate that attendances were higher for games that didn’t clash with internationals, when games were played in the evening under floodlights, and when the games were played at festival grounds (those that are not the county headquarters, where most fixtures were played).

Funk et al (2001) devised the Sport Interest Inventory (SII) to measure the motivation for spectators to attend sporting events. It was originally applied to women’s professional soccer in the US (Funk et al, 2002). The model has also been applied in the context of Japanese and Australian sport (Neale, 2006). However, the authors have pointed out the need to survey consumers in a specific situation before using motives to develop marketing strategy.

The models of Higgins and Martin (2006) and Funk et al (2001) were both developed in the context of American sport. The SII was not used by the authors, as the research is of an exploratory nature and is not a quantitative study. An amended version could, however, be applied in the next stage of research when spectators are interviewed.

English sports have a different calendar, culture and spectator tastes from American sports, and the authors believe that the factors of timing and weather might impact upon a decision to attend an event. Further research was needed to find out if they are vital factors in the success of Twenty20. The aim of the research was to investigate these factors. The authors felt that timing was a factor in the success of the launch, as there were no other major sporting events in the summer of 2003, such as an Olympics or World Cup. A comparison can be drawn here with Rugby League. In 1996 the sport introduced an innovation with the creation of the Super League. The changed timing of the event, from a winter to a summer calendar, proved successful, as evidenced by a 19% rise in attendances when launched (Mintel, 2003).

The model for the research was developed by adapting the Higgins and Martin (1996) ‘three strategic factors affecting the diffusion rate’ model. The perceived newness component is re-titled ‘perceived newness of sport’ for reasons of clarification. A fourth component is added to include contextual factors. In the case of cricket it was thought that weather and timing would be important in determining the likely success of the innovation, though there may be additional factors that emerge from respondents’ comments. An example of the impact of contextual factors, and the benefits to marketers of exploiting them, can be seen in the positive impact of the World Cup in 2002 on attendances in the Japanese football J League (Funk et al, 2006).

Objectives

• To measure the success of the competition in terms of attendances

• To identify the critical success factors of the competition

• To examine how the critical success factors identified in Twenty20 sit alongside the three strategic factors affecting the diffusion rate model of Higgins and Martin (1996)

Methodology

A two-stage approach was adopted. Details of attendances were gathered from secondary information sources to compare attendances across competitions (Mintel, 2006; Wisden, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007).

The authors also approached industry experts for their views on the competition. Because the research was of an introductory nature, an open-ended questionnaire was mailed to the marketing departments of the 18 first-class county cricket clubs in March 2005. Six questions were asked, the first two covering the areas of competition timing and the influence of weather, as discussed above. Respondents were also asked a further four questions regarding critical success factors to date, future critical success factors, the competition’s impact on finances, and whether the format had attracted a new audience. A final question allowed respondents to make further comments. Responses were received from seven of the counties. The respondent counties were all located in the middle and south of England. There was a noticeable absence from the northern counties.

….

QUESTIONNAIRE RESPONSES

Timing

All the respondents believed that the timing of the event was critical to the competition’s current success. Indeed timing was identified as crucial in different ways. The date range was selected because it would theoretically coincide with optimal weather conditions. The time of day was also a factor. A key objective was to make the event accessible to target markets, and the 5.30pm start enabled school children and the majority of workers to attend without encroaching on work time. Two respondents pointed out that the combination of these factors allowed families to attend. It was also felt that without other major sporting events occurring simultaneously, Twenty20 received more media coverage.

Weather

Respondents believed that the weather had an impact on initial success, although one pointed out that weather is crucial to all cricket competitions. However, the weather had not been as good in 2004 as in 2003. One respondent claimed that despite this, attendances increased in 2004 mainly through excitement. Another felt that good weather attracted a new audience in addition to established cricket fans.

Critical Success Factors

Respondents listed a number of factors here. Five mentioned the good entertainment provided by the competition. One respondent described the competition as having a reputation for fast and lively cricket. Satellite television and media coverage were mentioned four times, and the length of the game three times. Also mentioned were:

• The use of extensive market research

• Family orientation

• No other competition at the same time

• Early evening timing

• A result is gained

• Word-of-mouth advertising

• Attraction to women and children

• Extra activities leading to crowd involvement.

Future Critical Success Factors

Media interest was mentioned by five respondents in terms of maintaining satellite coverage and keeping the media interested. Five respondents also pointed out the problem of over-exposure of the format and the need to avoid saturation by having too many games. Two respondents mentioned the need to maintain the current format and keep it to a sensible calendar window slot.

Other factors highlighted were the competition from international Twenty20 cricket, which started in 2005 (Coward, 2007), weather, the need for counties to invest in marketing activities to sustain success, and the moving of games away from headquarters to other areas of the county.

Finances

All seven respondents agreed that the Twenty20 competition has made all the counties’ finances healthier, and some have come to rely on it to boost their income. For some counties, Twenty20 fixtures are the only games to sell out, and they bring in a big percentage of revenue. One respondent also pointed out that revenue was boosted not only by ticket sales and satellite coverage, but by secondary spending in catering outlets, beer sales, soft drinks etc. Another mentioned corporate hospitality as a good source of revenue.

New Audience

All respondents felt the competition has attracted a new audience: women and children (cited twice) families, non-county members, corporates, young people, people turned off by one-day cricket, 18-35 year olds, and sports fans in general.

Further Comments

One respondent attributed some of the success to crowd interaction, stating that it added to the atmosphere and general overall enjoyment. Another pointed out that Twenty20 led to more people attending other formats of the game, particularly floodlit matches.

CONCLUSIONS

The competition has proved to be a success in its first four years. The reasons for this can be seen in aspects of the three strategic factors affecting the diffusion rate model. In particular the characteristics of a shortened, three-hour version of the game were compatible with consumer needs, and sources of influence were gained through the media.

The timing and weather are not included as factors in the model. However, the findings from the primary and secondary data suggest strongly that these contextual issues need to be added to the model. There appear to be two aspects of timing that contributed to the success of the competition. First, that the competition is played at a time that is convenient for people to attend, and second, that it avoids competition with other sports, particularly football.

Further issues were mentioned and require more research, most notably the level of interaction of the sport. Some of the interaction is caused by events that are part of the match entertainment but not directly part of the game (Economist, 2003; Pryor 2004), but do these events contribute to the motive for attending?

FURTHER RESEARCH AND LIMITATIONS

The survey included only the county marketing teams. Research needs to be conducted among those who have attended games to investigate the issues discussed in the models, and in particular their motivation for going to matches. The SII model could be applied, but it needs to be adapted to take account of the contextual issues of timing in terms of convenience of attending, competing sports and the weather. The issue of crowd involvement in entertainment activities that are not part of the main game also requires investigation.

Further research is also needed to monitor the success of the competition following the introduction of international games in 2005. A World Cup was held in South Africa in 2007, but this did not coincide with English and Welsh domestic competition. Research is also required into the area of saturation. At what point is the game likely to reach saturation level, and what is the optimum number of games per season?

References

Booz, Allen & Hamilton (1982) New Product Management for the 1980s, New York: Booz, Allen and Hamilton, Inc.

Bridgewater, S. (2007) ‘International Marketing Mix’ in Beech, J. & Chadwick, S. (eds), The Marketing of Sport, FT-Prentice Hall.

Coward, M. (2007) ‘Traditionalists man the barricades’, The Australian, 7 November.

Cricinfo (1996) Cricket Max—The Game Invented By Martin Crowe, available from: http://content-eap.cricinfo.com/ci/content/story/67577.html [20 November 2007]

England and Wales Cricket Board (2005). About ECB and Twenty20, available from: http://www.ecb.co.uk/ecb/about/about-ecb.html [10 November 2004]

English, P. (2003) ‘Attention all non-cricket lovers’ Wisden Cricket Monthly, 17 June.

Funk, D.C., Mahony, D.F., Nakazawa, M. & Hirakawa, S. (2001) Development of the Sport Interest Inventory (SII): implications for measuring unique consumer motives at sporting events, International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship 3(3), 291–316.

Funk, D.C., Mahony, D.F. & Ridinger, L.L. (2002). ‘Characterizing consumer motivation as individual difference factors: augmenting the Sport Interest Inventory (SII) to explain specific sport interest’, Sport Marketing Quarterly 11, 1, 33–43.

Funk, D.C., Nakazawa, M., Mahony, D.F. & Thrasher, R. (2006) The impact of the national sports lottery and the FIFA World Cup on attendance, spectator motives and J. League marketing strategies, International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship 7(3) 267–285.

Garland, R., Inkson, K. & McDermott, P. (1999) ‘Sports Marketing’ in Sport Business Management in New Zealand in Trenberth, L. & Collins, C. Palmerson North: The Dunmore Press.

Haigh, G. (2007) ‘Shorter, simpler, sillier’. Available from: http://content-eap.cricinfo.com/ci/content/story/309625.xhtml?wrappertype=print [22 December 2007].

Harness, D. & Harness, T. (2007) ‘Managing sports products and services’ in Beech, J. & Chadwick, S. (eds) The Marketing of Sport. FT-Prentice Hall.

Higgins, S.H. & Martin, J.H. (1996) ‘Managing sport innovations: A diffusion theory perspective, Sport Marketing Quarterly 5(1), 43–48. Mahajan, V., Muller, E. & Bass, F.M. (1990) New product diffusion models in marketing: a review and directions for research, Journal of Marketing 54, 1–26.

Mahajan, V., Muller, E. & Srivastava, R.K. (1990) Determination of adopter categories by using innovation diffusion models, Journal of Marketing Research 27, 37–50.

McConnell, L. (2004) ‘Twenty20 in the land of Super Max’. Available from: http://content-eap.cricinfo.com/ci/content/story/135060html?wrappertype=print [22 December 2007].

Mintel (2003) UK Spectator Sport—April, available from http://academic.mintel.com, Mintel International Group Ltd, London.

Mintel (2006) Cricket and Rugby-UK—February. Available from: http://academic.mintel.com, Mintel International Group Ltd, London.

Neale, L. (2006) Investigating motivation, attitudinal loyalty and attendance behaviour with fans of Australian football, International Journal of Sports Marketing & Sponsorship 7(4), 307–17.

Papadimitriou, D., Apostolopoulou, A. & Loukas, I. (2004) The role of perceived fit in fans’ evaluation of sports brand extension, International Journal of Sports Marketing & Sponsorship 6(1), 31–48.

Paton, D. & Cooke, A. (2005) Attendance at county cricket: an economic analysis, Journal of Sports Economics, 6(1), 24–45.

Pryor, M. (2004) ‘Swift love affair that knows no boundaries’, The Times, 2 July, p.87.

Rogers, E.M. (1983) Diffusion of Innovations (3rd Edn). New York: Free Press.

The Economist (2003) ‘Adapt or die’, 21 June, p.33.

Twenty20 Cup Official Site, (2003) ‘Robertson wary of Twenty20 buzz’. Available from: http://www.thetwenty20cup.co.uk/news/newsitem.asp?NewsID=172 [2 April 2005].

Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack, (2004) 141st Edn, Edited by Engel, M. John Wisden, 833–42.

Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack, (2005) 142nd Edn, Edited by Engel, M. John Wisden, 887–98.

Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack, (2006) 143rd Edn, Edited by Engel, M. John Wisden, 890–96.

Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack, (2007) 144th Edn, Edited by Engel, M. John Wisden, 922–44.

Wisden Cricketer Monthly, (2003) July (71). Wisden Cricket Magazines.

SOCCER

ARSENAL FC ANNUAL REPORT, 2008

Chairman’s Report

P. D. Hill-Wood, Chairman, 18 September 2008

I am pleased to report another year of satisfactory progress against our key objectives of delivering long-term stability and success through the operation of the Club as a business which is self-sustaining. The annual accounts, which show a pre-tax profit of £36.7 million (2007—£5.6 million), clearly confirm the strength of the Group’s financial position following the move to Emirates Stadium. Your Board strongly believes this financial strength establishes the best possible foundation from which the Club can achieve footballing success long into the future.

During the 2007/08 season, the team played some highly entertaining and stylish football. The Club made a strong challenge for the Barclays Premier League title but eventually finished the season, just four points behind the winners, in a respectable third place. In addition, the Club reached the quarter-final stage of the UEFA Champions League and the semi-final stage of the Carling Cup.

… Our successful leverage of Emirates Stadium’s facilities is providing opportunities for the Group over and above those derived from the core business of staging the Club’s competitive fixtures. There is no doubt that Emirates Stadium has become a serious contender for the staging of major nonfootball events…. The stadium’s standing as a first class venue was further enhanced in March when it played host to a summit between Gordon Brown and French President Nicolas Sarkozy; the two political leaders held a joint press conference with the world’s media in attendance.

At the end of May music legend Bruce Springsteen played to two nights of sell-out audiences immediately establishing a reputation for Emirates Stadium as a nonfootball entertainment venue. Although the window between the end of the playing season and the start of work on renovating the pitch for the new season is relatively short, the staging of music events is certainly something we will consider again for the future. We have now successfully staged two Emirates Cups, in pre-season 2007 and 2008, and in March 2008 we played host to a third international friendly—Brazil v Sweden. We hope to continue with both the Emirates Cup and high quality non-Arsenal fixtures as regular features in the Emirates Stadium calendar.

We recognise that the Club’s operations have an impact on the local, national and global environment and during the year we have introduced a number of initiatives in order to try and operate as a more environmentally friendly organisation. We now have a dedicated recycling area in the stadium’s underground car park and on average we are recycling 10 tonnes per month of glass, cardboard and plastic which would previously have been sent to landfill. Other new initiatives in the year included progression of our supporter Contact Centre project. This brings together box office, home shopping, tours, travel and Junior Gunners operations for both telephone and e-mail handling and is designed to ensure an enhanced level of service is available to all of our supporters. The initial responses to the roll-out of this project have been encouraging.

I am delighted to confirm that E. Stanley Kroenke has accepted the Board’s invitation to become a non-executive director of Arsenal. Mr. Kroenke fully supports the approach the Board has taken in setting the direction of the Club and we believe his experience in sports team commercial management, sports marketing, media and new media rights as well as real estate development will be of great value. Mr. Kroenke is not a party to the “lock-down” arrangement entered into by the other members of the Board.

Mr. Kroenke is the shareholder in Kroenke Sports Enterprises (KSE), the leading live sports and entertainment group based in Denver, Colorado. In April this year KSE acquired from ITV plc a 50% share in Arsenal Broadband Limited and at the same time entered into a strategic partnership with the Club through Colorado Rapids, the KSE franchise.

….

ON THE FIELD

A look back at the first team’s 2007/08 season elicits mixed emotions. There is no doubt that the football played by Arsène Wenger’s side was often at a truly exceptional level, however, despite winning many plaudits, trophies were again to prove elusive.

The Premier League campaign yielded 83 points, some 15 points more than the previous season, and only three defeats yet only a third-placed finish. A fine ‘double’ over Tottenham Hotspur and an emphatic away win against Everton were particular highlights.

International call-ups and injuries—not least that which was suffered by our Croatian forward Eduardo at, perhaps, a pivotal point of his debut season—depleted the squad in the new year and this proved telling in the months of February and March when four consecutive draws considerably hampered the title challenge. Despite taking the lead in both games, the team then slipped to narrow defeats at Stamford Bridge and Old Trafford, which confirmed that the championship would not be heading to Emirates Stadium.

In the UEFA Champions League, a relatively straightforward Group Stage was followed by the glamour of a tie with reigning holders AC Milan. The excitement and pride felt by everybody connected with the Club following a famous 2-0 win at the San Siro, which secured progress to the quarter-finals, was considerable. However, domestic rivals Liverpool put an end to the European campaign on a dramatic night at Anfield in which a late Emmanuel Adebayor goal seemed to have earned us a place in the last four, only for two further strikes by the hosts to decide otherwise.

There were mixed fortunes in the domestic cups. Another fine Carling Cup run emphasized again the quality and depth of young talent which the Club is developing. The semi-finals were reached in some style although Tottenham Hotspur then prevailed through to the final. Early FA Cup successes against Burnley and Newcastle United were offset when a weakened side was beaten at Old Trafford in the fifth round of the competition.

Despite the disappointment felt at a season without winning a trophy, there can be no denying that progress was made in 2007/08. It is notable that Emirates Stadium is proving to be a significant factor in the team’s success—we remained unbeaten in all the 28 home matches played last season and, in fact, only one competitive game has been lost of the 58 played at our new home.

….

COMMERCIAL PARTNERS

Arsenal has continued to develop its commercial partner programme over the 2007/08 season. From a sponsorship perspective we are fortunate to be in a position where we are working closely with many high profile brands. During the year, Ebel joined our partner programme as official timing partner and we are also delighted to welcome Citroën, as the Club’s official car partner, for the start of the 2008/09 season.

We delivered our most successful merchandise figures ever during the 2007/08 season on the back of new second and third choice Nike kits and continuing excellence in own brand apparel, gifts and souvenirs delivered by S’porter, our retail partner. These results were assisted by a temporary store established in Enfield for the period ahead of Christmas 2007. A major overhaul of our Finsbury Park shop has been undertaken and a new store has recently been opened in St Albans. Further off-site stores are planned for the future.

Internationally, our merchandise business is also growing. Our Thai partner BEC Tero now has fourteen retail outlets for Arsenal merchandise, including a new flagship store in Phuket, Thailand. More distribution partnerships will be established for official club merchandise in other territories in the coming financial year.

Arsenal has been involved in other international activity which both improves the profile of the Club and drives revenues. Tiger Beer will continue to be Arsenal’s Official Beer in South East Asia for another three years. In Vietnam, the Club has secured sponsorship with Vinamilk, Gree Electrics and ICP, which will positively impact on the Club’s local profile. Financial service partnerships have been secured in Indonesia and Nigeria with Bank Danamon and UBA respectively. Local language official Arsenal websites in China, Korea, and Thailand continue to be used by over 300,000 local fans each month.

The international Arsenal Soccer Schools programme continues to advance. High quality facilities have opened in Bangkok, Thailand and Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam and represent further grassroots investment. Arsenal now has sixteen affiliated Soccer Schools abroad. The Club has made its first major entry into India with a high profile Arsenal football roadshow supported by Tata Tea.

Closer to home, Emirates Stadium has hosted a wide range of organisations for a variety of conference, banqueting and meeting events. The stadium provides a flexible and unique venue and along with our catering partner Delaware North we have become expert in hosting high quality functions. In addition, Emirates Stadium welcomed over 80,000 visitors on a variety of stadium tours during the 2007/08 season.

Emirates Stadium also hosts the production facility and studio used to broadcast Arsenal TV, which was successfully launched in January. The channel is part of the Setanta Sports package of channels and is also available through Virgin Media reaching approximately 5 million homes in the UK and Eire. We are extremely pleased with the quality of the programming and presentation, with much credit going to our production partner Input Media. Feedback from fans has been positive and consequently broadcasting hours have been increased for the 2008/09 season.

Our joint venture partner in the Arsenal.com website business changed, following ITV’s sale of their 50% shareholding to KSE, and we now look forward to further developing this already successful website operation alongside KSE.

During the year we also ended our own commercial relationship with ITV. All commercial development, including the Arsenal licensing programme, is now undertaken in house. We would like to thank ITV for all the hard work expended on the Club’s commercial programme and their contribution to our commercial success over the last few years.

CHARITY OF THE SEASON

Treehouse, the national charity for autism education, became Arsenal’s nominated charity for season 2007/08 taking over from The Willow Foundation. Treehouse was established in 1997 by a group of parents of autistic children and it aims to transform the lives of all children with autism and the lives of their families, by increasing the quantity and quality of autism education. The Club’s partnership with Treehouse … was a great success raising a record breaking £519,000 for the charity.

PROSPECTS

The property side of the business will inevitably be of considerable significance to the Group over the next year, with a large number of apartment sales scheduled to complete at Highbury Square and progression of the redevelopment plans for Queensland Road. We will be closely monitoring all stages of the sales completion process. Over 2008/09 the proceeds of Highbury Square sales will largely be used for the repayment of the related bank loans, consequently reducing the Group’s net debt from its current peak level. The two sides of the Group’s business are financed independently of each other and both the property and football business segments start the year from very sound financial bases.

On the field the new season has got off to a promising start. We have successfully negotiated the qualification round of the 2008/09 UEFA Champions League to ensure participation in the Group Stage and this is important to the Club both in competitive and financial terms.

This Club is ambitious for success and as always, at the start of the season, our expectations are high. We look forward to supporting the team, as it challenges for trophies, throughout the course of the season.

In closing, I would like to pay tribute to my fellow directors, our management team and our entire staff for all of their hard work and dedication over the last year. I would also like to thank our Highbury Square project team and all of our other professional advisers for the support they have provided.

Finally thank you for the fantastic support given to the Club by all of our shareholders, supporters, sponsors and commercial partners. I look forward to welcoming you all again to Emirates Stadium over the course of the new season.

FINANCIAL REVIEW

K. J. Friar, Managing Director, 18 September 2008

The results for the year show a very satisfactory outcome and provide a further confirmation of the strong financial position which the Group occupies following its move to Emirates Stadium.

Overall the Group increased its turnover from £200.8 million to £223.0 million and recorded a profit before taxation for the year of £36.7 million compared with £5.6 million (stated after exceptional charges of £21.4 million) in the previous year (see Tables 1 and 4).

Continued growth in revenue and profit in our core football business, including the benefit of the new Premier League TV contracts for season 2007/08, was balanced by a year of lower sales activity and a break-even operating return in the Group’s property development business. The results of the football and property development segments will be considered in more detail later in this review.

In terms of the Group’s balance sheet, the most significant change reflects the progress made toward completion of the Highbury Square residential development and the investment in this project was the main reason that the carrying value of development property stocks increased during the year to £188.0 million (2007 – £100.1 million).

| 2008 £m | 2007 £m | |

Group turnover | 223.0 | 200.8 |

Operating profit before depreciation and player trading | 59.6 | 51.2 |

Player trading | 5.2 | 0.2 |

Depreciation | (11.6) | (9.6) |

Joint venture | 0.5 | 0.4 |

Ordinary finance charges | (17.0) | (15.3) |

Profit before tax and exceptional items | 36.7 | 26.9 |

Profit before tax after exceptional items | 36.7 | 5.6 |

Source: Arsenal Football Club. Used with permission.

The Group’s overall net debt position rose to £318.1 million (2007 – £268.2 million). This increase in debt, which was anticipated both in last year’s annual report and this year’s interim statement, reflects the loans drawn down in funding the Highbury Square construction works. This level of net debt is expected to represent a peak for the Group with the level diminishing throughout 2008/09 as sale completions occur at Highbury Square.

The Highbury Square bank loan is included, on the basis of its projected repayment profile from receipts of sale completions, as part of creditors falling due within one year although the actual term date for the repayment of this loan facility extends to April 2010 (see Table 2).

Football Segment

The football business increased its turnover to £207.7 million (2007 – £177.0 million). This increase was mainly driven by the new Premier League domestic and overseas TV deals. The uplift in the value of these contracts, together with the levels of live coverage associated with our prominent challenge for the title and favourable exchange rates on £:_conversion of UEFA Champions League distributions to the quarter final stage, meant that total broadcasting revenues rose by some £24 million to in excess of £68 million. The main component of our turnover continues to be gate and match day revenue which at £94.6 million (2007 – £90.6 million) represents some 45% of total football revenues and 42% of the Group’s total revenues. There were 28 first team home fixtures in season 2007/08 which is one more than in the previous year and the average attendance was 59,720 (2007 – 59,850). We have been very successful in generating event income from our new home outside of the competitive first team fixture list; during the year Emirates Stadium hosted the inaugural Emirates Cup pre-season tournament which generated more than £4 million of ticket sales over two days, an international friendly fixture between Brazil and Sweden and two Bruce Springsteen concerts.

The continued growth in our retail turnover to £13.1 million (2007 – £12.1 million) and commercial revenues to £31.3 million (2007 – £29.5 million) has been referred to in the Commercial Partners section of the Chairman’s Report.

We remain firmly committed to sustained investment in the development of the playing squad in a market-place where the income from the new Premier League TV contracts has inevitably created a significant upward pressure on both transfer prices and players’ wage expectations. During the year we have improved and extended the contract terms of a large number of first team players and, of course, of Arsène Wenger himself. As a result, for the first time, the Group’s wage bill has exceeded nine figures at £101.3 million (2007 – £89.7 million). The wage/turnover ratio for the year, on a football segment basis, remained broadly stable at 48.8% (2007 – 50.6%) and continues to fall within our target range.

Table 2 Segmental Operating Results

| 2008 (£m) | 2007 (£m) | |

| Football | ||

Turnover | 207.7 | 177.0 |

Operating profit* | 59.6 | 42.2 |

Profit before tax and exceptional items | 39.7 | 20.8 |

| Property development | ||

Turnover | 15.3 | 23.8 |

Operating profit* | — | 9.0 |

(Loss)/profit before tax and exceptional items | (3.0) | 6.1 |

| Group | ||

Turnover | 223.0 | 200.8 |

Operating profit* | 59.6 | 51.2 |

Profit before tax and exceptional items | 36.7 | 26.9 |

*Operating profit before depreciation and player trading costs.

Source: Arsenal Football Club. Used with permission.