CHAPTER SIXTEEN

INTRODUCTION

One of the major issues that intercollegiate athletic directors must factor into their operations is the elements that enable an institution to attain gender equity. The key issue for managers in this area is compliance. Gender equity is often accomplished by means of Title IX, the federal law that requires equal opportunity in school-related athletics. Title IX, enacted in 1972, establishes that: “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” The articles and documents contained in this chapter explain what gender equity means, highlight the difficulties managers encounter in achieving it, and discuss the issues the athletics administrator must confront in order to comply. The articles also provide insight on how one sector of insiders can view the effectiveness of these policies.

Title IX is “Exhibit A” for the unique issues that collegiate administrators must grapple with that draw them away from the traditional professional sports and business goals of focusing on the bottom line or even exclusively on winning. Federal law mandates that gender equity be an essential element of the operational equation. This priority can have short- and long-term monetary impacts, particularly during transitional phases as an institution expands through NCAA divisions.

The chapter opens with an excerpt that provides a broad overview of the law related to Title IX in Rosner’s “The Growth of NCAA Women’s Rowing: A Financial, Ethical and Legal Analysis.” Rosner also provides the specifics of the applicability of Title IX in relation to rowing. Rowing is referred to by some as the equivalent of football in terms of the numbers of athletes that participate and the difficulty that it causes in efforts to ensure equality.

The next three documents provide the U.S. government’s interpretation of the law. Insight is gained by looking at various letters interpreting the rules as issued by the United States Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR), the federal administrative agency responsible for the oversight of Title IX. Arguably, these documents are the first step in attempting to understand the complexities of Title IX. The federal courts evaluating the merits of Title IX litigation have shown them great deference. The first is “Clarification of Intercollegiate Athletics Policy Guidance: The Three-Part Test.” It is this three-part test that determines whether an academic institution is in compliance with Title IX. The OCR later issued additional clarification related to financial aid in a document referred to as the “Letter Clarifying Apportionment of Financial Aid in Intercollegiate Athletics.” The next OCR-produced document is a letter that was designed to provide “Further Clarification of Intercollegiate Athletics Policy Guidance Regarding Title IX Compliance.” This provides the most recent “final word” and guidance to the athletics administrator for Title IX. This letter was issued following contemplation of a report titled “Open to All: Title IX at Thirty,” which was issued by a special commission created by the Secretary of Education to study Title IX 30 years after its passage. The Secretary’s Commission on Opportunities in Athletics was charged to investigate and report back with “recommendations on how to improve the application of the current standards for measuring equal opportunity to participate in athletics under Title IX.” The report was issued in early 2003. The letter included in this chapter from U.S. Assistant Secretary of Education for Civil Rights Gerald A. Reynolds essentially calls for no radical changes. However, it is clear that the guidelines and requirements—although now much more clearly defined—continue to evolve.

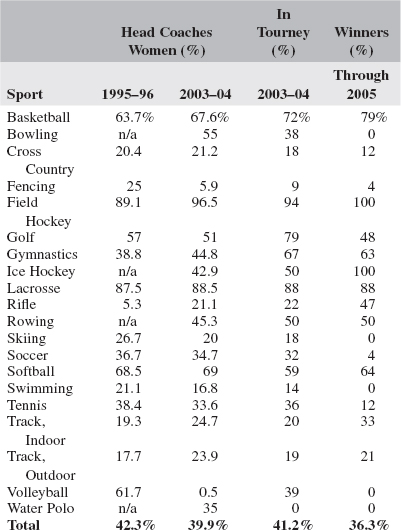

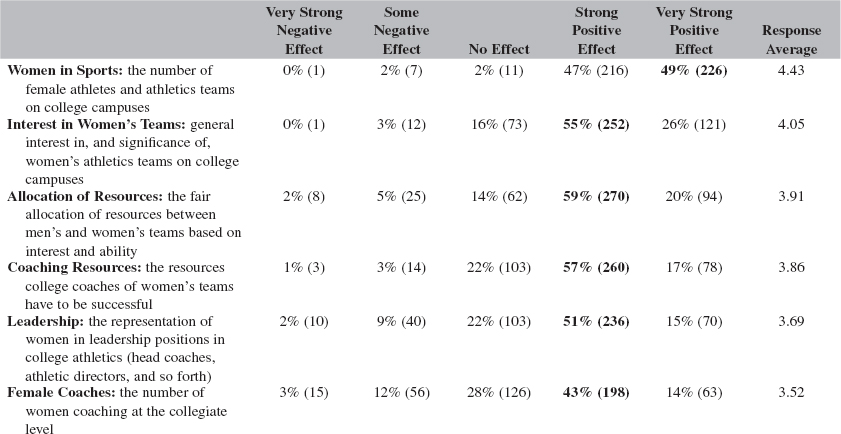

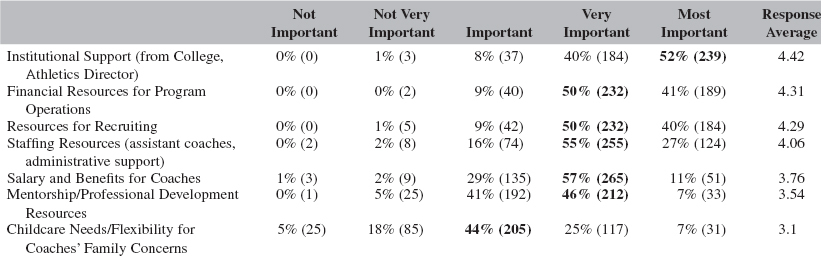

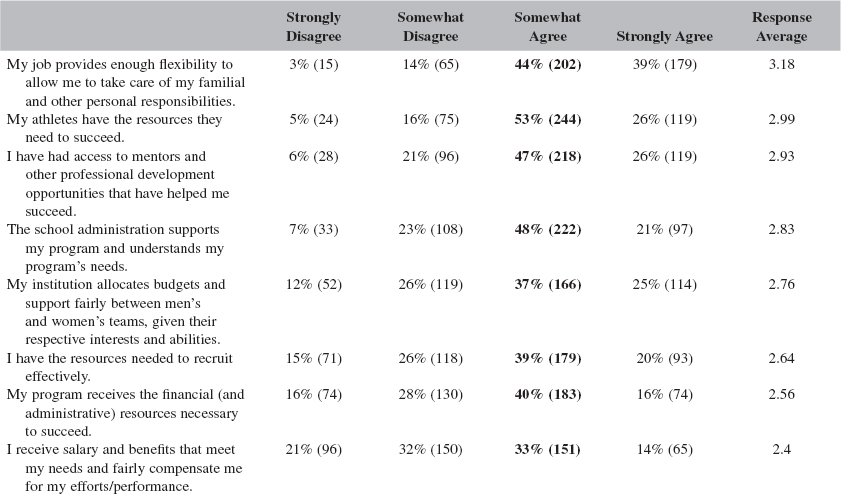

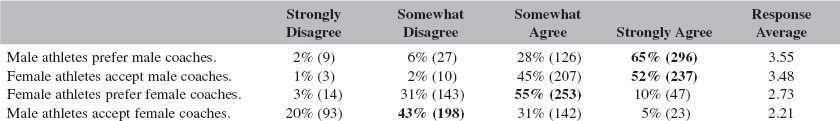

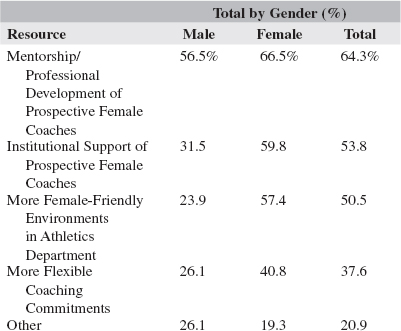

The final excerpt, from Rhode and Walker’s article “Gender Equity in College Athletics: Women Coaches as a Case Study,” provides a clear look at the impact of Title IX after 35 years via the results of an extensive survey of 450 coaches of women’s intercollegiate sports.

OPERATIONAL ISSUES

THE GROWTH OF NCAA WOMEN’S ROWING: A FINANCIAL, ETHICAL, AND LEGAL ANALYSIS

Scott R. Rosner

….

III. LEGAL ASPECTS

A History of Title IX

Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 is a federal law prohibiting sex discrimination in education programs and activities receiving or benefiting from federal funding.70 While not specifically mentioned in the law itself, athletics are covered by Title IX.71 Consequently, this law has been the primary method by which women have achieved equal opportunity in high school and college athletics, and it has played a vital role in opening competition to female athletes.72 Though signed into law on June 23, 1972,73 the Department of Health, Education and Welfare’s final Title IX regulations74 did not go into effect until July 21, 1975, and were not enforced until the three-year compliance period expired in 1978.75 In order to clarify the requirements of Title IX and to provide schools with guidance on their obligations under the law, the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) issued its final Policy Interpretation on December 11, 1979.76 This outlines a detailed set of standards to be adhered to in three separate areas: student interests and abilities, athletic benefits and opportunities, and athletic financial assistance.77

Though the Policy Interpretation is not a rule of law, it has been given substantial deference by courts determining the rights of female athletes.78 After the period of enforcement that followed the issuance of the Policy Interpretation, female athletes suffered a setback when athletic programs were removed from coverage under Title IX by Grove City v. Bell.79 As a result of this judicial setback, OCR immediately cancelled all forty of its ongoing Title IX athletics investigations and ignored any new complaints regarding athletics.80 Congress acted rather quickly to correct the narrowing of Title IX that Grove City had accomplished and enacted the Civil Rights Restoration Act in 1988,81 overriding a veto by President Reagan.82 The Act served the purpose of reversing the Supreme Court’s decision in Grove City by stipulating that Title IX applies to all programs of an educational institution that receive any federal financial assistance.83 The revitalization of Title IX was fortified by the Supreme Court’s decision in Franklin v. Gwinnett County Public Schools,84 which allowed private plaintiffs to receive monetary damages and attorney fees for an intentional violation of Title IX.85

In addition to these agency regulations and legislative and judicial statements, Title IX has been shaped by three other policy documents issued by OCR:86 the Title IX Investigator’s Manual;87 the Clarification of Intercollegiate Athletics Policy Guidance: The Three-Part Test;88 and a letter offering guidance regarding the issuance of athletics scholarships.89 … [Ed. Note: See these two latter documents beginning on p. 622.]

B. Analysis and Application of Title IX to Women’s Rowing

1. Student Interests and Abilities

As previously mentioned, compliance with Title IX is measured in three separate areas: student interests and abilities, athletic benefits and opportunities, and athletic financial assistance.90 Under Title IX, the athletic interests and abilities of male and female students must be equally and effectively accommodated.91 OCR will assess whether an institution is in compliance with this aspect of Title IX through the application of the following three-part test:

(1) Whether intercollegiate level participation opportunities for male and female students are provided in numbers substantially proportionate to their respective enrollments; or

(2) Where the members of one sex have been and are underrepresented among intercollegiate athletes, whether the institution can show a history and continuing practice of program expansion which is demonstrably responsive to the developing interest and abilities of the members of that sex; or

(3) Where the members of one sex are underrepresented among intercollegiate athletes, and the institution cannot show a continuing practice of program expansion such as that cited above, whether it can be demonstrated that the interests and abilities of the members of that sex have been fully and effectively accommodated by the present program.92

An institution may choose any one of the three benchmarks established by this test in order to satisfy the accommodation requirement.93 OCR also considers the quality of competition available to members of both sexes,94 but it is this three-part test that has been the most litigated aspect of Title IX in determining whether the interests and abilities of an institution’s students are effectively accommodated.95

Under part one of the three-part test, OCR looks at whether an institution’s participation opportunities for its male and female students are substantially proportionate to their full-time undergraduate enrollments.96 Although OCR will find that an institution with a closely mirrored image between these two figures is effectively accommodating the interests and abilities of its students, very few institutions have been able to take advantage of this “safe harbor.”97 In 1997, only fifty-one institutions in NCAA Division I were within even five percentage points of achieving substantial proportionality.98 For many institutions, this is due to the presence of football. The number of participation opportunities in football is unmatched by any other sport.99 An institution would typically have to sponsor at least three women’s teams in order to match the number of athletes on a football team.100 Thus, it becomes extremely difficult for an institution sponsoring a Division I-A football team to comply with the first benchmark.101

The growth of women’s rowing in the NCAA is primarily attributable to its positive impact on institutions attempting to comply with the interests and abilities aspect of Title IX via the substantial proportionality test.102 The large roster size of a women’s rowing team has made it an extremely attractive alternative for athletic administrators looking to increase the number of participation opportunities afforded to an institution’s female students.103 The average roster size of a women’s rowing team is the largest of any NCAA women’s sport—nearly twice that of outdoor track and field, which has the second largest roster of any women’s sport.104 It is not uncommon for a crew to have 100 rowers.105 Therefore, rowing is “women’s football” in terms of roster size. It is a “quick fix” for institutions looking to offer substantially proportionate athletic opportunities to its female students.

While the first benchmark has been the focus of both litigants and courts, the dearth of institutions satisfying this test requires that attention be given to part two of the three-part test of Title IX compliance—whether an institution has a history and continuing practice of program expansion for the underrepresented sex. OCR reviews an institution’s previous and ongoing remedial efforts to determine its compliance with this benchmark.106 Of primary importance is ascertaining whether an institution has expanded its program over time in a manner that is demonstrably responsive to the developing interests of the underrepresented sex.107 To do so, OCR will review if the school has added or elevated women’s teams to intercollegiate status, added participation opportunities for female athletes, and its responses to female students’ requests to add or elevate sports.108 In determining whether an institution has a continuing practice of program expansion that is demonstrably responsive to the developing interests of the underrepresented sex, OCR looks to whether the institution has effectively communicated to students a procedure for requesting the addition or upgrading of a sport.109 In addition, the current implementation of an institution’s plan to expand an underrepresented program is viewed favorably by OCR.110 In Boucher v. Syracuse University,111 the court held that the institution’s addition of women’s lacrosse, soccer, and softball between 1996 and 1999 was evidence that it had a history and continuing practice of program expansion for its female athletes.112 Syracuse University is the first … institution to successfully rely on this benchmark in proving its compliance with Title IX.113

Women’s rowing is beneficial to those institutions choosing to comply with the second benchmark. The tremendous growth of the sport at the intercollegiate level allows those schools that have recently begun to sponsor it to claim a history of program expansion.114 The addition or elevation of a women’s rowing team, and the numerous participation opportunities added for female athletes via the sport, will be evaluated positively by OCR.115 At those institutions that have added or elevated the sport upon the request of its students, the affirmative response will receive similar approval from OCR.116 The large number of NCAA institutions that are able to make these claims because of women’s rowing is reflected in the sport becoming the first to move from Emerging to Championship status.117 In addition, there are several institutions that have announced plans to add or elevate a women’s rowing team in the near future.118 These institutions may claim a continuing practice of program expansion through their implementation of a plan to add the sport.

In part three of the three-part test, an institution may claim that it is fully and effectively accommodating the interests and abilities of its female students even though it has neither achieved substantial proportionality nor demonstrated a history and continuing practice of program expansion.119 In reviewing this claim, OCR evaluates whether there is unmet interest in a particular sport, sufficient ability to sustain a team in the sport, and a reasonable expectation of competition for a team.120 First, OCR looks at several indicators to determine whether there is unmet interest in a particular sport at an institution.121 These indicators include whether the institution has been requested to add or elevate a particular sport by its current or admitted students; participation in a particular club or intramural sport at the institution; participation in certain interscholastic sports by admitted students; and sports participation rates in the high schools, amateur athletic groups, and community sports leagues in the areas from which an institution draws most of its students.122 Second, OCR looks at the potential ability of either an existing club team or interested students to evaluate if there exists a sufficient ability to sustain an intercollegiate team in the sport.123 Third, OCR reviews if there is a reasonable expectation of intercollegiate competition available for a team in both the institution’s conference and surrounding geographic area.124 If there is unmet interest in a particular sport, sufficient ability to sustain a team in the sport, and a reasonable expectation of competition for a team, then the institution has not fully and effectively accommodated the interests and abilities of its female students.125

Women’s rowing may or may not help an institution satisfy the third benchmark of Title IX compliance. There are many strong club teams at the college level.126 If one of them requests elevation to the intercollegiate level, and the institution is located in an area with a high participation rate at both the high school and intercollegiate levels, then the institution could not refuse to elevate the women’s rowing team and still claim that it is fully and effectively accommodating the interests and abilities of its female students.127 This is due to the fact that all three compliance requirements would have been met by the women’s rowing team.128 However, there are several potential problems with this analysis that may allow an institution faced with a request to add a women’s rowing team to refuse to do so with no Title IX impunity. There is likely to be a paucity of feeder rowing programs in many institutions’ normal recruiting area, as there are so few club and high school programs throughout the country.129 Depending on the geographic location of the institution and its conference affiliation, there may not be a reasonable expectation of intercollegiate competition in the institution’s vicinity.130 Thus, there would be no unmet interest or reasonable expectation of competition. Under these circumstances, the institution could claim that it is fully and effectively accommodating the interests and abilities of its female students without adding a rowing team.

2. Athletic Benefits and Opportunities

The second area of concern for Title IX compliance is the parity of athletic benefits and opportunities between male and female students.131 Though only one court has issued a decision addressing these requirements at the intercollegiate level thus far, they are an important aspect of Title IX compliance that are likely to be the future focus of the courts.132 In addition to looking at student interests and abilities, the law specifies that OCR examine other factors in determining whether there is equal opportunity in athletics.133 The Policy Interpretation requires the following factors to be considered in determining whether an institution is providing equality in athletic benefits and opportunities: provision and maintenance of equipment and supplies; scheduling of games and practice times; travel and per diem expenses; opportunity to receive coaching and academic tutoring; assignment and compensation of coaches and tutors; provision of locker rooms and practice and competitive facilities; provision of medical and training services and facilities; provision of housing and dining services and facilities; publicity; provision of support services; and recruitment of student athletes.134 Each of these factors is evaluated by comparing an institution’s entire male and female athletic program with respect to the availability, quality and kinds of benefits, opportunities, and treatment afforded.135 While identical benefits, opportunities and treatments are not required, the effects of any differences must be negligible.136

The impact of women’s rowing on any one particular aspect of this area of Title IX compliance is relatively small. However, any inequity in the women’s rowing program is magnified because of the large number of participation opportunities provided by the sport.137 Because a significant percentage of the female athletes at an institution may be rowers, the impact of women’s rowing on this area may be considerable.138 Of primary concern is the effect of women’s rowing on the provision and maintenance of equipment and supplies, scheduling of games, and the construction of practice and competitive facilities.139

Perhaps the most compelling of these components are equipment and supplies.140 The quality of equipment offered to both male and female athletes must be similar.141 However, the cost of the equipment used in women’s rowing is quite high.142 As a result, many institutions opt to purchase used equipment to lower their expenses, especially when beginning a program.143 If a women’s rowing program is using inferior equipment for a sustained period of time, the institution may encounter difficulty establishing compliance with this component. The amount of equipment provided to male and female athletes also must be similar.144 It seems logical to expect that there should be enough equipment to ensure that all members of a team will be able to practice at the same time. Providing enough boats for the entire team to be on the water at the same time becomes an expensive proposition for a rowing team. Due to this expense, many institutions have opted not to purchase a sufficient number of rowing shells; the rowers must “take turns” on the water.145 Institutions engaging in this practice may find it similarly difficult to prove compliance with this component.

One of the ways in which the maintenance of equipment and supplies is measured is by how equipment is repaired.146 Men’s and women’s teams should have their equipment repaired in the same manner.147 If there is a professional equipment manager, repairs should be done for a similar number of men’s and women’s teams.148 The specialized nature of rowing requires a trained individual to repair and maintain the equipment.149 While some institutions employ either a part-time or full-time rigger, in many cases these repair duties are the responsibility of the coach. This may be a compliance problem for an institution, because its equipment repair policy may result in inequality between the men’s and women’s teams. Replacement of equipment typically must be done on the same schedule for men’s and women’s teams unless there is a difference justified by the nature of the sport.150 While rowing may be of a sufficiently unique nature to justify a different replacement schedule, this difference must not cause an inequity between male and female athletes if the institution wishes to remain in compliance with Title IX.151 The expense of purchasing new rowing equipment is likely to make it tempting for athletic administrators to delay this transaction. Nevertheless, administrators must not shy away from replacing old rowing equipment because of the expense involved if it results in inequitable treatment of female athletes.

Compliance with Title IX also implicates the procedures adopted by an institution for scheduling games and practice time for the women’s rowing team.152 The time of day during which competitive events and practices are scheduled should be equally convenient for the men’s and women’s teams.153 Since most regattas are scheduled on weekends, the women’s rowing team facilitates an institution’s compliance with this component.

Women’s rowing impacts upon the provision of practice and competitive facilities as well.154 Practice and competitive facilities must be of equivalent quality and availability.155 The assignment of a women’s team to a poorer quality facility is a common compliance problem.156 This is manifested in the sport of women’s rowing by the type of boathouse facility used by many crews. Construction or renovation of a boathouse is a very expensive proposition.157 Instead of engaging in such a project when adding or elevating a women’s rowing team, many institutions choose to look at alternatives to incurring these large capital expenses. The institution may enter into a rental agreement with an existing boathouse or utilize an older boathouse that was previously used by the institution’s men’s or women’s club rowing team. If these options prove unattractive, the institution may store equipment in a semi-trailer in close proximity to the practice water158 or simply transport equipment to and from the institution to the practice water on boat trailers every day.159 Engaging in these practices may make it extremely difficult for an institution to comply with this component; the poor quality of many of these facilities likely creates an inequity between male and female athletes. The availability of practice facilities involves the scheduling and location of these facilities. The location of the practice facility is of concern if the facility for a team of one sex is off campus and in an inconvenient location.160 Most boathouses fit this description, as they tend to be located some distance from campus.161 While the nature of the sport may justify some inconvenience in the availability of the practice facility, the institution should attempt to minimize this burden as much as possible so as to reduce any inequities between male and female athletes.

3. Athletic Financial Assistance

The final area of concern for Title IX compliance is athletic financial assistance.162 Though only 46 institutions are in compliance,163 this area has also received little judicial attention.164 None of the three courts that have reviewed cases involving athletic financial assistance has found a violation of Title IX.165 OCR presumes compliance in this area if the total amount of athletic scholarship dollars awarded to male and female athletes is within one percent of their respective participation rates in intercollegiate athletics at the institution.166 Women’s rowing may play an important role in an institution’s compliance with this standard due to the large number of athletic scholarships that can be awarded. The NCAA allows for the equivalent of twenty full athletic scholarships to be awarded in women’s rowing.167 This is the largest of any women’s sport.168 When all sports are taken into consideration, only football offers more scholarships.169 Thus, the presence of a women’s rowing team is the single greatest ally to an institution hoping to comply with the athletic financial assistance standard established by OCR.

Notes

….

70. 20 U.S.C. 1681 provides in relevant part that “no person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance….”

71. See 34 C.F.R. 106.41 (1975).

72. Masteralexis, supra note 16, at 184.

73. History of Title IX Legislation, Regulation and Policy Interpretation, at bailiwick.lib.uiowa.edu/ge/history.html (last visited May 24, 1999).

74. 34 C.F.R. 106.41 (1975).

75. Id.

76. The Office for Civil Rights within the U.S. Department of Education is responsible for the enforcement of Title IX. Letter from Dr. Mary Francis O’Shea, National Coordinator for Title IX Athletics, Office for Civil Rights, to Nancy Foster, General Counsel, Bowling Green State University (July 23, 1998), available at bailiwick.lib.uiowa.edu/ge/.

77. 44 Fed. Reg. 71413 (1979). See also Requirements Under Title IX, supra note 12. These requirements will be discussed further in Part III.B infra.

78. See Robert D’Augustine, A Loosely Laced Buskin?: The Department of Education’s Policy Interpretation For Applying Title IX To Intercollegiate Athletics, 6 Seton Hall J. Sport L. 469, 473-80 (1996).

79. 465 U.S. 555 (1984). The Supreme Court limited the application of Title IX to programs or activities that received direct federal financial assistance. See id. As most athletic departments do not receive such direct funding, they were removed from coverage under Title IX.

80. History of Title IX Legislation, Regulation and Policy Interpretation, supra note 73.

81. Pub. L. No. 100-259, 102 Stat. 28 (1988) (codified at 20 U.S.C. 1687).

82. History of Title IX Legislation, Regulation and Policy Interpretation, supra note 73.

83. Id.

84. 503 U.S. 60 (1992).

85. Id.

86. Valerie Bonnette, Title IX Basics, available at www.ncaa.org/library/general/achieving_gender_equity/ (n.d.).

87. Valerie Bonnette and Lamar Daniel, Office for Civil Rights, Title IX Investigator’s Manual (1990).

88. Office for Civil Rights, Clarification of Intercollegiate Athletics Policy Guidance: The Three-Part Test, January 16, 1996, available at www.ncaa.org/library/general/achieving_gender_equity/ [hereinafter 1996 Clarification Letter].

89. 1998 Guidance Letter, supra note 76.

90. 44 Fed. Reg. 71413 (1979), See also Requirements Under Title IX, supra note 12.

91. Requirements Under Title IX, supra note 12.

92. 44 Fed. Reg. 71418 (1979).

93. 1996 Clarification Letter, supra note 88, at II-25.

94. Id.

95. See e.g., Cohen v. Brown Univ., 991 F.2d 888 (1st Cir. 1993); Boucher v. Syracuse Univ., 164 F.3d 113 (2d Cir. 1999); Pederson v. La. State Univ., 201 F.3d 388 (5th Cir. 2000).

96. 1996 Clarification Letter, supra note 88, at II-26. In doing so, OCR considers only the actual number of participants in intercollegiate athletics, including the walk-ons who make a squad and practice but do not compete. Id. OCR excludes intramural sports and any unfilled roster slots from this calculation. Id. An individual who quits after two weeks of practice is not counted as a participant. Bonnette, supra note 86. Women’s rowing has a high attrition rate because of the demanding nature of the sport. See Brett Johnson, A Look at the University of Louisville’s First Year (Part II), USRowing, June 2000, at 21-23 [hereinafter Johnson (Part II)]. A large number of individuals who attend practices in the preseason quit the sport before the competitive schedule begins; these individuals are not counted as participants. See id. Thus, the number of participation opportunities provided by women’s rowing is somewhat limited because of its difficulty.

97. See Gender Equity Creative Solutions; A Case Study of What Education Institutions Can Do In Order To Comply With The Regulations of Title IX, at www.womenssportsfoundation.org (last visited May 12, 2000). Less than 9% of Division I institutions are able to do so. Id. An example is often helpful in understanding this aspect of the law. An institution with 10,000 full-time undergraduate students - 5200 women and 4800 men - must offer 52% of its participation opportunities in intercollegiate athletics to women to be in strict compliance with part one. See 1996 Clarification Letter, supra note 88. OCR makes the determination of whether an institution is in compliance with part-one on a case-by-case basis, as there is no strict statistical cut-off for a finding of substantial proportionality. See id.

98. Chronicle of Higher Education, Participation: Proportion of Female Students on Athletic Teams, athttp://www.chronicle.com/search97cgi/s97_cgi (last visited Jan. 19, 2001).

99. See NCAA, 1998–99 Participation Study—Men’s Sports (2000), available at http://www.ncaa.org/participation_rates/1998-99_m_partrates.pdf (last visited May 16, 2000). The average roster size for football is 113.4 in Division I-A and 92.7 in Division I-AA. Id.

100. Brewington, supra note 1.

101. See Chronicle of Higher Education, Participation: Proportion of Female Students on Athletic Teams, supra note 98. Only 18 institutions in Division I-A and 20 institutions in Division I-AA were within five percentage points of achieving substantial proportionality. Id.

102. Carton, supra note 59.

103. Brewington, supra note 1.

104. 1998-99 Participation Study, supra note 10.

105. Wallace, supra note 9.

106. 1996 Clarification Letter, supra note 88, at II-27. An institution cannot meet the requirements of part two simply by cutting men’s teams or participation opportunities. Id. Nor can a school cut women’s teams or participation opportunities without replacing them with additional teams or opportunities. Id. “Part two considers an institution’s good-faith remedial efforts through actual program expansion.” Id.

107. See supra note 92 and accompanying text.

108. 1996 Clarification Letter, supra note 88, at II-28. While no definitive time frame is mentioned by OCR, it is clear that the addition or elevation must be relatively recent. See id.

109. 1996 Clarification Letter, supra note 88, at II-28.

110. Id. Mere promises to expand the program do not suffice. Id.

111. 164 F.3d 113 (2d Cir. 1999).

112. Id. at 119.

113. Carol Barr, Still Afloat, Athletic Business, Oct. 1999, at 26-28.

114. This takes the form of an addition of a women’s team at those institutions where there was no club team prior to the formation of an intercollegiate women’s rowing team; at institutions that upgrade a club team to the intercollegiate level, the decision is considered an elevation. See 1996 Clarification Letter, supra note 88, at II-28.

115. See 1996 Clarification Letter, supra note 88, at II-28.

116. Id. Any institution doing so may also be able to claim that it has a continuing practice of program expansion if it had a policy or procedure in place for requesting the addition or upgrading of sports that was effectively communicated to students. Id.

117. See supra note 42 and accompanying text.

118. Jeff Metcalfe, ASU Wet Behind Ears But Aims to be Water Power, The Arizona Republic, Sept. 8, 1999, at C1. Arizona State University will add a rowing team in 2001–02. Id.

119. 1996 Clarification Letter, supra note 88, at II-29. This includes students who have been accepted but are not yet enrolled at the institution. Id.

120. 1996 Clarification Letter, supra note 88, at II-29. An institution that has recently eliminated a viable intercollegiate women’s team is highly unlikely to satisfy part three. Id.

121. Id.

122. Id.

123. Id.

124. 1996 Clarification Letter, supra note 88, II-30-31.

125. Id. at II-30.

126. American Rower’s Almanac, supra note 3, at 489-94.

127. See Bonnette, supra note 86.

128. See id. “Compliance with this third method is unlikely if there is a sport not currently offered to the underrepresented sex for which there is sufficient competition in the institution’s normal competitive regions and; a club team; and/or significant participation at high schools in the institution’s normal recruitment area; and/or substantial intramural participation.” Id.

129. See supra note 3 and accompanying text.

130. See supra notes 53-54 and accompanying text.

131. 44 Fed. Reg. 71413 (1979).

132. See Cook v. Colgate Univ., 802 F. Supp. 737 (N.D.N.Y. 1992), vacated as moot, 992 F.2d 17 (2d Cir. 1993) (College women’s hockey team established a prima facie Title IX violation by coming forth with evidence that the university had provided significantly superior funding and equipment to the men’s team).

133. 44 Fed. Reg. 71413 (1979).

134. Id.

135. Id.

136. Id.

137. See supra notes 103-05 and accompanying text. This is especially important given that the analysis of compliance with Title IX often focuses on whether the equivalent quality and quantities of benefits and services are provided to equivalent percentages of female and male athletes. See Bonnette, supra note 86. Many athletic administrators focus on comparing similar sports with each other for the purpose of this area of analysis, as they find that it is the easiest method by which to ensure compliance. See id. at II-2. Football creates a problem for these administrators because it is usually afforded better benefits than any other sport, yet does not have a similar women’s sport to provide a basis for comparison. See id. at II-3. Thus, the administrators must provide “football-like” benefits to several sports in order to be in compliance with this area. See id. Although the sports are dissimilar in nature, football and women’s rowing are similar in the number of participation opportunities that they provide; this allows for an easier comparison between men’s and women’s athletics and, therefore, facilitates compliance with this area of Title IX. See generally id. at II-9-24. Even this comparison is not flawless; it is likely that football will still receive greater benefits in areas such as compensation of coaches, medical and training services, publicity, recruitment, and support services. However, the institution has available numerous justifications for the differences in the provisions of these services. See generally, Bonnette, supra note 86, at II-9-24.

138. See supra notes 103-05 and accompanying text.

139. See 44 Fed. Reg. 71414 (1979). See also Fed. Reg. 71416 (1979).

140. See 44 Fed. Reg. 71414 (1979). “Compliance will be assessed by examining, among other factors, the equivalence for men and women of: (1) the quality of equipment and supplies; (2) the amount of equipment and supplies; (3) the suitability of equipment and supplies; (4) the maintenance and replacement of the equipment and supplies; and (5) the availability of equipment and supplies.” Id.

141. See id.

142. The specific equipment costs are discussed at length…

143. See infra…

144. See 44 Fed. Reg. 71414 (1979).

145. See Hale, supra note 52.

146. See 44 Fed. Reg. 71414 (1979).

147. Bonnette, supra note 86, at II-10.

148. Id.

149. Sue Rochman, Journey Towards Equity, Athletic Management, June/July 1998, at 23. This individual is referred to as a rigger. Id.

150. Bonnette, supra note 86, at II-10.

151. See id.

152. See 44 Fed. Reg. 71416 (1979). “Compliance will be assessed by examining, among other factors, the equivalence for men and women of: (1) the number of competitive events per sport; (2) the number and length of practice opportunities; (3) the time of day competitive events are scheduled; (4) the time of day practice opportunities are scheduled; and (5) the opportunities to engage in available pre-season and post-season competition.” Id.

153. See Valerie Bonnette, Title IX Basics, available at www.neaa.org/library/general/achieving_gender_equity/ (n.d.) at II-11.

154. See 44 Fed. Reg. 71417 (1979). “Compliance will be assessed by examining, among other factors, the equivalence for men and women of: (1) quality and availability of the facilities provided for practice and competitive events; (2) exclusivity of use of facilities provided for practice and competitive events; (3) availability of locker rooms; (4) quality of locker rooms; (5) maintenance of practice and competitive facilities; and (6) preparation of facilities for practice and competitive events.” Id.

155. Id. There is some flexibility in evaluating this standard depending on the nature of the facility used. See Bonnette, supra note 86, at II-16.

156. Id.

157. The specific construction costs are discussed at length…

158. United States Rowing Ass’n, Women’s Rowing 2 (1995).

159. Telephone interview with Rob Catloth, Head Women’s Rowing Coach, University of Kansas (June 2, 1999).

160. Bonnette, supra note 86, at II-17. The scheduling of the boathouse will not be of concern unless there are rental terms that stipulate that the facility only be used by the institution at times that are inconvenient for the athletes. Id.

161. Johnson (Part II), supra note 96. Louisville’s team travels 43 miles to practice. Id. The rowing team at Robert Morris College practices at a boathouse eighteen miles from campus. Rochman, supra note 149, at 26.

162. 44 Fed. Reg. 71414 (1979) requires that the amounts spent on scholarships be offered on a “substantially proportional basis to the number of male and female participants in the institution’s athletic programs.” Id.

163. Chronicle of Higher Education, Participation: Proportion of Female Students on Athletic Teams, at http://www.chronicle.com/search97cgi/s97_cgi (last visited Jan. 19, 2001).

164. See Judith Jurin Semo and John F. Bartos, A Guide to Recent Developments in Title IX Litigation - February 15, 2000, Achieving Gender Equity at III-2, at http://www.ncaa.org/library/general/achieving_gender_equity/ (n.d.) (discussing Gonyo v. Drake Univ., 837 F. Supp. 989 (S.D. Iowa 1993); Beasley v. Ala. State Univ., 3 F. Supp.2d 1325 (M.D. Ala. 1998); Boucher v. Syracuse Univ., 164 F.3d 113 (2d Cir. 1999)).

165. Id.

166. 1998 Guidance Letter, supra note 76. Therefore, if females constitute 55 percent of the athletes at an institution, then they must receive between 54 and 56 percent of the athletic scholarship dollars awarded by institution. Id. OCR allows variations of larger than one percent under several circumstances, including during the phase-in period for scholarships that are awarded by a new team. Id.

167. NCAA Manual, supra note 11, 15.5.3.1.2. The NCAA classifies sports into two categories for the purpose of athletic scholarships. Head count sports are those sports in which only full athletic scholarships may be awarded if they are awarded at all. Id. at 15.5.2, 15.5.4, 15.5.5. In Division I, football, men’s basketball, and women’s basketball, gymnastics, tennis, and volleyball are head count sports. Equivalency sports are sports in which partial athletic scholarships may be awarded. All other NCAA sports are equivalency sports. Id. at 15.5.3.

168. Id.

169. NCAA Manual, supra note 11, 15.5.5.1, 15.5.5.2. A football team in Division I-A may award 85 scholarships, while a team in Division I-AA may offer the equivalent of 63 scholarships to 85 individuals. Id.

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

CLARIFICATION OF INTERCOLLEGIATE ATHLETICS POLICY GUIDANCE: THE THREE-PART TEST (JANUARY 16, 1996)

United States Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights

The Office for Civil Rights (OCR) enforces Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, 20 U.S.C. § 1681 et seq. (Title IX), which prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex in education programs and activities by recipients of federal funds. The regulation implementing Title IX, at 34 C.F.R. Part 106, effective July 21, 1975, contains specific provisions governing athletic programs, at 34 C.F.R. § 106.41, and the awarding of athletic scholarships, at 34 C.F.R. § 106.37(c). Further clarification of the Title IX regulatory requirements is provided by the Intercollegiate Athletics Policy Interpretation, issued December 11, 1979 (44 Fed. Reg. 71413 et seq. (1979)).*

The Title IX regulation provides that if an institution sponsors an athletic program it must provide equal athletic opportunities for members of both sexes. Among other factors, the regulation requires that an institution must effectively accommodate the athletic interests and abilities of students of both sexes to the extent necessary to provide equal athletic opportunity.

The 1979 Policy Interpretation provides that as part of this determination OCR will apply the following three-part test to assess whether an institution is providing nondiscriminatory participation opportunities for individuals of both sexes:

1. Whether intercollegiate level participation opportunities for male and female students are provided in numbers substantially proportionate to their respective enrollments; or

2. Where the members of one sex have been and are underrepresented among intercollegiate athletes, whether the institution can show a history and continuing practice of program expansion which is demonstrably responsive to the developing interests and abilities of the members of that sex; or

3. Where the members of one sex are underrepresented among intercollegiate athletes, and the institution cannot show a history and continuing practice of program expansion, as described above, whether it can be demonstrated that the interests and abilities of the members of that sex have been fully and effectively accommodated by the present program.

Thus, the three-part test furnishes an institution with three individual avenues to choose from when determining how it will provide individuals of each sex with nondiscriminatory opportunities to participate in intercollegiate athletics. If an institution has met any part of the three-part test, OCR will determine that the institution is meeting this requirement.

It is important to note that under the Policy Interpretation the requirement to provide nondiscriminatory participation opportunities is only one of many factors that OCR examines to determine if an institution is in compliance with the athletics provision of Title IX. OCR also considers the quality of competition offered to members of both sexes in order to determine whether an institution effectively accommodates the interests and abilities of its students.

In addition, when an “overall determination of compliance” is made by OCR, 44 Fed. Reg. 71417, 71418, OCR examines the institution’s program as a whole. Thus, OCR considers the effective accommodation of interests and abilities in conjunction with equivalence in the availability, quality, and kinds of other athletic benefits and opportunities provided male and female athletes to determine whether an institution provides equal athletic opportunity as required by Title IX. These other benefits include coaching, equipment, practice and competitive facilities, recruitment, scheduling of games, and publicity, among others. An institution’s failure to provide nondiscriminatory participation opportunities usually amounts to a denial of equal athletic opportunity because these opportunities provide access to all other athletic benefits, treatment, and services.

This Clarification provides specific factors that guide an analysis of each part of the three-part test. In addition, it provides examples to demonstrate, in concrete terms, how these factors will be considered. These examples are intended to be illustrative, and the conclusions drawn in each example are based solely on the facts included in the example.

THREE-PART TEST—PART ONE: ARE PARTICIPATION OPPORTUNITIES SUBSTANTIALLY PROPORTIONATE TO ENROLLMENT?

Under part one of the three-part test (part one), where an institution provides intercollegiate level athletic participation opportunities for male and female students in numbers substantially proportionate to their respective full-time undergraduate enrollments, OCR will find that the institution is providing nondiscriminatory participation opportunities for individuals of both sexes.

OCR’s analysis begins with a determination of the number of participation opportunities afforded to male and female athletes in the intercollegiate athletic program. The Policy Interpretation defines participants as those athletes:

a. Who are receiving the institutionally-sponsored support normally provided to athletes competing at the institution involved, e.g., coaching, equipment, medical and training room services, on a regular basis during a sport’s season; and

b. Who are participating in organized practice sessions and other team meetings and activities on a regular basis during a sport’s season; and

c. Who are listed on the eligibility or squad lists maintained for each sport, or

d. Who, because of injury, cannot meet a, b, or c above but continue to receive financial aid on the basis of athletic ability.

OCR uses this definition of a participant to determine the number of participation opportunities provided by an institution for purposes of the three-part test.

Under this definition, OCR considers a sport’s season to commence on the date of a team’s first intercollegiate competitive event and to conclude on the date of the team’s final intercollegiate competitive event. As a general rule, all athletes who are listed on a team’s squad or eligibility list and are on the team as of the team’s first competitive event are counted as participants by OCR. In determining the number of participation opportunities for the purposes of the interests and abilities analysis, an athlete who participates in more than one sport will be counted as a participant in each sport in which he or she participates.

In determining participation opportunities, OCR includes, among others, those athletes who do not receive scholarships (e.g., walk-ons), those athletes who compete on teams sponsored by the institution even though the team may be required to raise some or all of its operating funds, and those athletes who practice but may not compete. OCR’s investigations reveal that these athletes receive numerous benefits and services, such as training and practice time, coaching, tutoring services, locker room facilities, and equipment, as well as important non-tangible benefits derived from being a member of an intercollegiate athletic team. Because these are significant benefits, and because receipt of these benefits does not depend on their cost to the institution [or] whether the athlete competes, it is necessary to count all athletes who receive such benefits when determining the number of athletic opportunities provided to men and women.

OCR’s analysis next determines whether athletic opportunities are substantially proportionate. The Title IX regulation allows institutions to operate separate athletic programs for men and women. Accordingly, the regulation allows an institution to control the respective number of participation opportunities offered men and women. Thus, it could be argued that to satisfy part one there should be no difference between the participation rate in an institution’s intercollegiate athletic program and its full-time undergraduate student enrollment.

However, because in some circumstances it may be unreasonable to expect an institution to achieve exact proportionality—for instance, because of natural fluctuations in enrollment and participation rates or because it would be unreasonable to expect an institution to add athletic opportunities in light of the small number of students that would have to be accommodated to achieve exact proportionality—the Policy Interpretation examines whether participation opportunities are “substantially” proportionate to enrollment rates. Because this determination depends on the institution’s specific circumstances and the size of its athletic program, OCR makes this determination on a case-by-case basis, rather than through use of a statistical test.

As an example of a determination under part one: If an institution’s enrollment is 52 percent male and 48 percent female and 52 percent of the participants in the athletic program are male and 48 percent female, then the institution would clearly satisfy part one. However OCR recognizes that natural fluctuations in an institution’s enrollment and/or participation rates may affect the percentages in a subsequent year. For instance, if the institution’s admissions the following year resulted in an enrollment rate of 51 percent males and 49 percent females, while the participation rates of males and females in the athletic program remained constant the institution would continue to satisfy part one because it would be unreasonable to expect the institution to fine tune its program in response to this change in enrollment.

As another example, over the past five years an institution has had a consistent enrollment rate for women of 50 percent. During this time period, it has been expanding its program for women in order to reach proportionality. In the year that the institution reaches its goal—i.e., 50 percent of the participants in its athletic program are female—its enrollment rate for women increases to 52 percent. Under these circumstances, the institution would satisfy part one.

OCR would also consider opportunities to be substantially proportionate when the number of opportunities that would be required to achieve proportionality would not be sufficient to sustain a viable team, i.e., a team for which there is a sufficient number of interested and able students and enough available competition to sustain an intercollegiate team. As a frame of reference in assessing this situation, OCR may consider the average size of teams offered for the under-represented sex, a number which would vary by institution.

For instance, Institution A is a university with a total of 600 athletes. While women make up 52 percent of the university’s enrollment, they only represent 47 percent of its athletes. If the university provided women with 52 percent of athletic opportunities, approximately 62 additional women would be able to participate. Because this is a significant number of unaccommodated women, it is likely that a viable sport could be added. If so, Institution A has not met part one.

As another example, at Institution B women also make up 52 percent of the university’s enrollment and represent 47 percent of Institution B’s athletes. Institution B’s athletic program consists of only 60 participants. If the University provided women with 52 percent of athletic opportunities, approximately 6 additional women would be able to participate. Since 6 participants are unlikely to support a viable team, Institution B would meet part one.

THREE-PART TEST—PART TWO: IS THERE A HISTORY AND CONTINUING PRACTICE OF PROGRAM EXPANSION FOR THE UNDERREPRESENTED SEX?

Under part two of the three-part test (part two), an institution can show that it has a history and continuing practice of program expansion which is demonstrably responsive to the developing interests and abilities of the underrepresented sex. In effect, part two looks at an institution’s past and continuing remedial efforts to provide nondiscriminatory participation opportunities through program expansion.*

____________

*Part two focuses on whether an institution has expanded the number of intercollegiate participation opportunities provided to the underrepresented sex. Improvements in the quality of competition, and of other athletic benefits provided to women athletes, while not considered under the three-part test, can be considered by OCR in making an overall determination of compliance with the athletics provision of Title IX.

OCR will review the entire history of the athletic program, focusing on the participation opportunities provided for the underrepresented sex. First, OCR will assess whether past actions of the institution have expanded participation opportunities for the underrepresented sex in a manner that was demonstrably responsive to their developing interests and abilities. Developing interests include interests that already exist at the institution.† There are no fixed intervals of time within which an institution must have added participation opportunities. Neither is a particular number of sports dispositive. Rather, the focus is on whether the program expansion was responsive to developing interests and abilities of the underrepresented sex. In addition, the institution must demonstrate a continuing (i.e., present) practice of program expansion as warranted by developing interests and abilities.

____________

†However, under this part of the test an institution is not required, as it is under part three, to accommodate all interests and abilities of the underrepresented sex. Moreover, under part two an institution has flexibility in choosing which teams it adds for the underrepresented sex, as long as it can show overall history and continuing practice of program expansion for members of that sex.

OCR will consider the following factors, among others, as evidence that may indicate a history of program expansion that is demonstrably responsive to the developing interests and abilities of the underrepresented sex.

• An institution’s record of adding intercollegiate teams, or upgrading teams to intercollegiate status, for the underrepresented sex;

• An institution’s record of increasing the numbers of participants in intercollegiate athletics who are members of the underrepresented sex; and

• An institution’s affirmative responses to requests by students or others for addition or elevation of sports.

OCR will consider the following factors, among others, as evidence that may indicate a continuing practice of program expansion that is demonstrably responsive to the developing interests and abilities of the underrepresented sex:

• An institution’s current implementation of a nondiscriminatory policy or procedure for requesting the addition of sports (including the elevation of club or intramural teams) and the effective communication of the policy or procedure to students; and

• An institution’s current implementation of a plan of program expansion that is responsive to developing interests and abilities.

OCR would also find persuasive an institution’s efforts to monitor developing interests and abilities of the underrepresented sex, for example, by conducting periodic nondiscriminatory assessments of developing interests and abilities and taking timely actions in response to the results.

In the event that an institution eliminated any team for the underrepresented sex, OCR would evaluate the circumstances surrounding this action in assessing whether the institution could satisfy part two of the test. However, OCR will not find a history and continuing practice of program expansion where an institution increases the proportional participation opportunities for the underrepresented sex by reducing opportunities for the overrepresented sex alone or by reducing participation opportunities for the overrepresented sex to a proportionately greater degree than for the underrepresented sex. This is because part two considers an institution’s good faith remedial efforts through actual program expansion. It is only necessary to examine part two if one sex is overrepresented in the athletic program. Cuts in the program for the underrepresented sex, even when coupled with cuts in the program for the overrepresented sex, cannot be considered remedial because they burden members of the sex already disadvantaged by the present program. However, an institution that has eliminated some participation opportunities for the underrepresented sex can still meet part two if, overall, it can show a history and continuing practice of program expansion for that sex.

In addition, OCR will not find that an institution satisfies part two where it established teams for the under-represented sex only at the initiation of its program for the underrepresented sex or where it merely promises to expand its program for the underrepresented sex at some time in the future.

The following examples are intended to illustrate the principles discussed above. At the inception of its women’s program in the mid-1970s, Institution C established seven teams for women. In 1984 it added a women’s varsity team at the request of students and coaches. In 1990 it upgraded a women’s club sport to varsity team status based on a request by the club members and an NCAA survey that showed a significant increase in girls high school participation in that sport. Institution C is currently implementing a plan to add a varsity women’s team in the spring of 1996 that has been identified by a regional study as an emerging women’s sport in the region. The addition of these teams resulted in an increased percentage of women participating in varsity athletics at the institution. Based on these facts, OCR would find Institution C in compliance with part two because it has a history of program expansion and is continuing to expand its program for women in response to their developing interests and abilities.

By 1980, Institution D established seven teams for women. Institution D added a women’s varsity team in 1983 based on the requests of students and coaches. In 1991 it added a women’s varsity team after an NCAA survey showed a significant increase in girls’ high school participation in that sport. In 1993 Institution D eliminated a viable women’s team and a viable men’s team in an effort to reduce its athletic budget. It has taken no action relating to the underrepresented sex since 1993. Based on these facts, OCR would not find Institution D in compliance with part two. Institution D cannot show a continuing practice of program expansion that is responsive to the developing interests and abilities of the underrepresented sex where its only action since 1991 with regard to the underrepresented sex was to eliminate a team for which there was interest, ability, and available competition.

In the mid-1970s, Institution E established five teams for women. In 1979 it added a women’s varsity team. In 1984 it upgraded a women’s club sport with twenty-five participants to varsity team status. At that time it eliminated a women’s varsity team that had eight members. In 1987 and 1989 Institution E added women’s varsity teams that were identified by a significant number of its enrolled and incoming female students when surveyed regarding their athletic interests and abilities. During this time it also increased the size of an existing women’s team to provide opportunities for women who expressed interest in playing that sport. Within the past year, it added a women’s varsity team based on a nationwide survey of the most popular girls high school teams. Based on the addition of these teams, the percentage of women participating in varsity athletics at the institution has increased. Based on these facts, OCR would find Institution E in compliance with part two because it has a history of program expansion and the elimination of the team in 1984 took place within the context of continuing program expansion for the underrepresented sex that is responsive to their developing interests.

Institution F started its women’s program in the early 1970s with four teams. It did not add to its women’s program until 1987 when, based on requests of students and coaches, it upgraded a women’s club sport to varsity team status and expanded the size of several existing women’s teams to accommodate significant expressed interest by students. In 1990 it surveyed its enrolled and incoming female students; based on that survey and a survey of the most popular sports played by women in the region, Institution F agreed to add three new women’s teams by 1997. It added a women’s team by 1991 and 1994. Institution F is implementing a plan to add a women’s team by the spring of 1997. Based on these facts, OCR would find Institution F in compliance with part two. Institution F’s program history since 1987 shows that it is committed to program expansion for the underrepresented sex and it is continuing to expand its women’s program in light of women’s developing interests and abilities.

THREE-PART TEST—PART THREE: IS THE INSTITUTION FULLY AND EFFECTIVELY ACCOMMODATING THE INTERESTS AND ABILITIES OF THE UNDERREPRESENTED SEX?

Under part three of the three-part test (part three) OCR determines whether an institution is fully and effectively accommodating the interests and abilities of its students who are members of the underrepresented sex—including students who are admitted to the institution though not yet enrolled. Title IX provides that a recipient must provide equal athletic opportunity to its students. Accordingly, the Policy Interpretation does not require an institution to accommodate the interests and abilities of potential students.*

*However, OCR does examine an institution’s recruitment practices under another part of the Policy Interpretation. See 44 Fed. Reg. 71417. Accordingly, where an institution recruits potential student athletes for its men’s teams, it must ensure that women’s teams are provided with substantially equal opportunities to recruit potential student athletes.

While disproportionately high athletic participation rates by an institution’s students of the overrepresented sex (as compared to their enrollment rates) may indicate that an institution is not providing equal athletic opportunities to its students of the underrepresented sex, an institution can satisfy part three where there is evidence that the imbalance does not reflect discrimination, i.e., where it can be demonstrated that, notwithstanding disproportionately low participation rates by the institution’s students of the underrepresented sex, the interests and abilities of these students are, in fact, being fully and effectively accommodated.

In making this determination, OCR will consider whether there is (a) unmet interest in a particular sport; (b) sufficient ability to sustain a team in the sport; and (c) a reasonable expectation of competition for the team. If all three conditions are present OCR will find that an institution has not fully and effectively accommodated the interests and abilities of the underrepresented sex.

If an institution has recently eliminated a viable team from the intercollegiate program, OCR will find that there is sufficient interest, ability, and available competition to sustain an intercollegiate team in that sport unless an institution can provide strong evidence that interest, ability, or available competition no longer exists.

a) Is there sufficient unmet interest to support an intercollegiate team?

[First,] OCR will determine whether there is sufficient unmet interest among the institution’s students who are members of the underrepresented sex to sustain an intercollegiate team. OCR will look for interest by the underrepresented sex as expressed through the following indicators, among others:

• Requests by students and admitted students that a particular sport be added;

• Requests that an existing club sport be elevated to intercollegiate team status;

• Participation in particular club or intramural sports;

• Interviews with students, admitted students, coaches, administrators, and others regarding interest in particular sports;

• Results of questionnaires of students and admitted students regarding interests in particular sports; and

• Participation in particular interscholastic sports by admitted students.

In addition, OCR will look at participation rates in sports in high schools, amateur athletic associations, and community sports leagues that operate in areas from which the institution draws its students in order to ascertain likely interest and ability of its students and admitted students in particular sport(s).* For example, where OCR’s investigation finds that a substantial number of high schools from the relevant region offer a particular sport which the institution does not offer for the underrepresented sex, OCR will ask the institution to provide a basis for any assertion that its students and admitted students are not interested in playing that sport. OCR may also interview students, admitted students, coaches, and others regarding interest in that sport.

_______________

*While these indications of interest may be helpful to OCR in ascertaining likely interest on campus, particularly in the absence of more direct indications, the institution is expected to meet the actual interests and abilities of its students.

An institution may evaluate its athletic program to assess the athletic interest of its students of the underrepresented sex using nondiscriminatory methods of its choosing. Accordingly, institutions have flexibility in choosing a nondiscriminatory method of determining athletic interests and abilities provided they meet certain requirements. These assessments may use straightforward and inexpensive techniques, such as a student questionnaire or an open forum, to identify students’ interests and abilities. Thus, while OCR expects that an institution’s assessment should reach a wide audience of students and should be open-ended regarding the sports students can express interest in, OCR does not require elaborate scientific validation of assessment.

An institution’s evaluation of interest should be done periodically so that the institution can identify in a timely and responsive manner any developing interests and abilities of the underrepresented sex. The evaluation should also take into account sports played in the high schools and communities from which the institution draws its students both as an indication of possible interest on campus and to permit the institution to plan to meet the interests of admitted students of the underrepresented sex.

b) Is there sufficient ability to sustain an intercollegiate team?

Second, OCR will determine whether there is sufficient ability among interested students of the underrepresented sex to sustain an intercollegiate team. OCR will examine indications of ability such as:

• The athletic experience and accomplishments—in interscholastic, club, or intramural competition—of students and admitted students interested in playing the sport;

• Opinions of coaches, administrators, and athletes at the institution regarding whether interested students and admitted students have the potential to sustain a varsity team; and

• If the team has previously competed at the club or intramural level, whether the competitive experience of the team indicates that it has the potential to sustain an intercollegiate team.

Neither a poor competitive record nor the inability of interested students or admitted students to play at the same level of competition engaged in by the institution’s other athletes is conclusive evidence of lack of ability. It is sufficient that interested students and admitted students have the potential to sustain an intercollegiate team.

c) Is there a reasonable expectation of competition for the team?

Finally, OCR determines whether there is a reasonable expectation of intercollegiate competition for a particular sport in the institution’s normal competitive region. In evaluating available competition, OCR will look at available competitive opportunities in the geographic area in which the institution’s athletes primarily compete, including:

• Competitive opportunities offered by other schools against which the institution competes; and

• Competitive opportunities offered by other schools in the institution’s geographic area, including those offered by schools against which the institution does not now compete.

Under the Policy Interpretation, the institution may also be required to actively encourage the development of intercollegiate competition for a sport for members of the underrepresented sex when overall athletic opportunities within its competitive region have been historically limited for members of that sex.

CONCLUSION

This discussion clarifies that institutions have three distinct ways to provide individuals of each sex with nondiscriminatory participation opportunities. The three-part test gives institutions flexibility and control over their athletics programs. For instance, the test allows institutions to respond to different levels of the interest by its male and female students. Moreover, nothing in the three-part test requires an institution to eliminate participation opportunities for men.

At the same time, this flexibility must be used by institutions consistent with Title IX’s requirement that they not discriminate on the basis of sex. OCR recognizes that institutions face challenges in providing nondiscriminatory participation opportunities for their students and will continue to assist institutions in finding ways to meet these challenges.

LETTER CLARIFYING APPORTIONMENT OF FINANCIAL AID IN INTERCOLLEGIATE ATHLETICS PROGRAMS (JULY 23, 1998)

United States Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights

Ms. Nancy S. Footer

General Counsel

Bowling Green State University

308 McFall Center

Bowling Green, Ohio 43403-0010

Dear Ms. Footer:

This is in response to your letter requesting guidance in meeting the requirements of Title IX specifically as it relates to the equitable apportionment of athletic financial aid. Please accept my apology for the delay in responding. As you know, the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) enforces Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, 20 U.S.C. § 1682, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex in education programs and activities. The regulation implementing Title IX and the Department’s Intercollegiate Athletics Policy Interpretation published in 1979—both of which followed publication for notice and the receipt, review, and consideration of extensive comments—specifically address intercollegiate athletics. You have asked us to provide clarification regarding how educational institutions can provide intercollegiate athletes with nondiscriminatory opportunities to receive athletic financial aid. Under the Policy Interpretation, the equitable apportioning of a college’s intercollegiate athletics scholarship fund for the separate budgets of its men’s and women’s programs—which Title IX permits to be segregated—requires that the total amounts of scholarship aid made available to the two budgets are “substantially proportionate” to the participation rates of male and female athletes. 44 Fed. Reg. 71413, 71415 (1979).

In responding, I wish (1) to clarify the coverage of Title IX and its regulations as they apply to both academic and athletic programs, and (2) to provide specific guidance about the existing standards that have guided the enforcement of Title IX in the area of athletic financial aid, particularly the Policy Interpretation’s “substantially proportionate” provision as it relates to a college’s funding of the athletic scholarships budgets for its men’s and women’s teams. At the outset, I want to clarify that, wholly apart from any obligation with respect to scholarships, an institution with an intercollegiate athletics program has an independent Title IX obligation to provide its students with nondiscriminatory athletic participation opportunities. The scope of that separate obligation is not addressed in this letter, but was addressed in a Clarification issued on January 16, 1996.

TITLE IX COVERAGE: ATHLETICS VERSUS ACADEMIC PROGRAMS

Title IX is an anti-discrimination statute that prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex in any education program or activity receiving federal financial assistance, including athletic programs. Thus, in both academics and athletics, Title IX guarantees that all students, regardless of gender, have equitable opportunities to participate in the education program. This guarantee does not impose quotas based on gender, either in classrooms or in athletic programs. Indeed, the imposition of any such strict numerical requirement concerning students would be inconsistent with Title IX itself, which is designed to protect the rights of all students and to provide equitable opportunities for all students.

Additionally, Title IX recognizes the uniqueness of intercollegiate athletics by permitting a college or university to have separate athletic programs, and teams, for men and women. This allows colleges and universities to allocate athletic opportunities and benefits on the basis of sex. Because of this unique circumstance, arguments that OCR’s athletics compliance standards create quotas are misplaced. In contrast to other antidiscriminatory statutes, Title IX compliance cannot be determined simply on the basis of whether an institution makes sex-specific decisions, because invariably they do. Accordingly, the statute instead requires institutions to provide equitable opportunities to both male and female athletes in all aspects of its two separate athletic programs. As the court in the Brown University case stated, “[i]n this unique context Title IX operates to ensure that the gender-segregated allocation of athletic opportunities does not disadvantage either gender. Rather than create a quota or preference, this unavoidable gender-conscious comparison merely provides for the allocation of athletic resources and participation opportunities between the sexes in a nondiscriminatory manner.” Cohen v. Brown University, 101 F.3d 155, 177 (1st Cir. 1996), cert. denied, 117 S. Ct. 1469 (1997). The remainder of this letter addresses the application of Title IX only to athletic scholarships.

Athletics: Scholarship Requirements

With regard to athletic financial assistance, the regulations promulgated under Title IX provide that, when a college or university awards athletic scholarships, these scholarship awards must be granted to “members of each sex in proportion to the number of students of each sex participating in … intercollegiate athletics.” Since 1979, OCR has interpreted this regulation in conformity with its published “Policy Interpretation: Title IX and Intercollegiate Athletics.” The Policy Interpretation does not require colleges to grant the same number of scholarships to men and women, nor does it require that individual scholarships be of equal value. What it does require is that, at a particular college or university, “the total amount of scholarship aid made available to men and women must be substantially proportionate to their [overall] participation rates” at that institution. It is important to note that the Policy Interpretation only applies to teams that regularly compete in varsity competition.

Under the Policy Interpretation, OCR conducts a “financial comparison to determine whether proportionately equal amounts of financial assistance (scholarship aid) are available to men’s and women’s athletic programs.” The Policy Interpretation goes on to state that “[i]nstitutions may be found in compliance if this comparison results in substantially equal amounts or if a disparity can be explained by adjustments to take into account legitimate nondiscriminatory factors.”

A “disparity” in awarding athletic, financial assistance refers to the difference between the aggregate amount of money athletes of one sex received in one year, and the amount they would have received if their share of the entire annual budget for athletic scholarships had been awarded in proportion to their participation rates. Thus, for example, if men account for 60% of a school’s intercollegiate athletes, the Policy Interpretation presumes that—absent legitimate nondiscriminating factors that may cause a disparity—the men’s athletic program will receive approximately 60% of the entire annual scholarship budget, and the women’s athletic program will receive approximately 40% of those funds. This presumption reflects the fact that colleges typically allocate scholarship funds among their athletic teams, and that such teams are expressly segregated by sex. Colleges’ allocation of the scholarship budget among teams, therefore, is invariably sex-based, in the sense that an allocation to a particular team necessarily benefits one sex to the exclusion of the other. Where, as here, disparate treatment is inevitable and a college’s allocation of scholarship funds is “at the discretion of the institution,” the statute’s nondiscrimination requirements obliges colleges to ensure that men’s and women’s separate activities receive equitable treatment.