CHAPTER THIRTEEN

INTRODUCTION

The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) is the dominant organization governing college sports in the United States today. Other organizations, including the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA), have played various roles over the years, but the NCAA has been the most prominent. Thus, this chapter and the ones that follow focus on the most important business issues related to the NCAA.

The key distinction between collegiate sports and the professional sports discussed in earlier chapters is the role of profit. College sports are focused on more than just the bottom line, in theory and in practice in most cases. Collegiate athletics are tied to interests as diverse as student morale, campus public relations, institutional profile, fundraising, and student physical fitness. As a result of this mix, athletic directors and college presidents arguably have a much more complicated juggling act than the professional sports team general manager or team owner, whose focus is much more on the bottom line.

The articles presented in this chapter provide a great deal of information on the NCAA. It is important to note that when the NCAA was originally formed at the turn of the last century it was focused on promoting safety, specifically seeking to end the deaths that had been occurring in collegiate football. The excerpted article by Smith, “A Brief History of the National Collegiate Athletic Association’s Role in Regulating Intercollegiate Athletics,” provides information on the organization’s background, as does the material from Masteralexis, Barr, and Hums, excerpted from Principles and Practice of Sport Management (3rd edition).

What most informal critics miss when contemplating collegiate sports is the actual governing structure of the NCAA. Those who understand college athletics point out that the NCAA is not a monolithic organization that dictates what occurs in the governance of collegiate sports. The NCAA is, in fact, governed by its over 1000 member institutions. The NCAA is divided into three divisions. In 2008–2009, 330 institutions were competing in the three Division I subdivisions: 119 in the Football Bowl Subdivision (formerly Division I-A), 118 in the Football Championship Subdivision (formerly Division I-AA), and 93 in the Division I Without Football Subdivision (formerly Division I-AAA). The Division II level had 282 institutions, and Division III had 422 institutions. It is these member organizations that determine how collegiate sports will operate via the numerous representative paths in the NCAA. Governing rules address issues ranging from eligibility to the operation of championships. The selection from Yasser, McCurdy, Goplerud, and Weston provides a textbook overview of the organization.

The rules of the NCAA are set forth in the organization’s constitution and bylaws, which are available in the NCAA Manual. Governing information may be found at http://www.ncaa.org.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE NATIONAL COLLEGIATE ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION’S ROLE IN REGULATING INTERCOLLEGIATE ATHLETICS

Rodney K. Smith

….

II. A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE NATIONAL COLLEGIATE ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION

A. 1840–1910

The need for regulation of intercollegiate athletics in the United States has existed for at least a century and a half. One of the earliest interschool athletic events was a highbrow regatta between Harvard and Yale Universities, which was commercially sponsored by the then powerful Elkins Railroad Line.5 Harvard University sought to gain an undue advantage over its academic rival Yale by obtaining the services of a coxswain who was not a student.6 Thus, the commercialization and propensity to seek unfair advantages existed virtually from the beginning of organized intercollegiate athletics in the United States. The problem of cheating, which was no doubt compounded by the increasing commercialization of sport, was a matter of concern.7 Initially, these concerns led institutions to move the athletic teams from student control to faculty oversight.8 Nevertheless, by the latter part of the nineteenth century, two leading university presidents were voicing their fears that intercollegiate athletics were out of control.9 President Eliot at Harvard was very concerned about the impact that commercialization of intercollegiate athletics was having, and charged that “lofty gate receipts from college athletics had turned amateur contests into major commercial spectacles.”10 In the same year, President Walker of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology bemoaned the fact that intercollegiate athletics had lost its academic moorings and opined that “[i]f the movement shall continue at the same rate, it will soon be fairly a question whether the letters B.A. stand more for Bachelor of Arts or Bachelor of Athletics.”11 In turn, recognizing the difficulty of overseeing intercollegiate athletics at the institutional level, whether through the faculty or the student governance, conferences were being created both to facilitate the playing of a schedule of games and to provide a modicum of regulation at a broader level.12

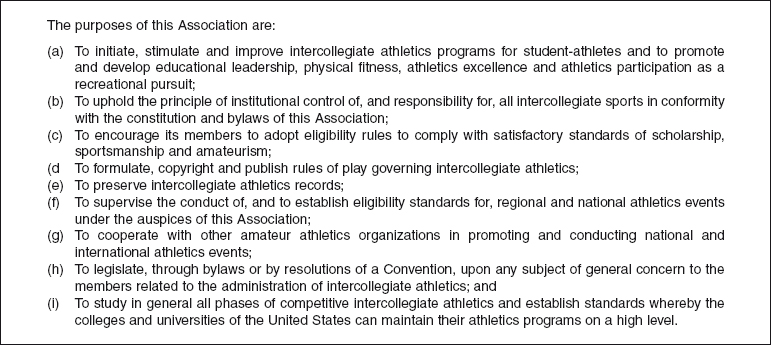

Despite the shift from student control to faculty oversight and some conference regulation, intercollegiate athletics remained under-regulated and a source of substantial concern.13 Rising concerns regarding the need to control the excesses of intercollegiate athletics were compounded by the fact that in 1905 alone, there were over eighteen deaths and one hundred major injuries in intercollegiate football.14 National attention was turned to intercollegiate athletics when President [Theodore] Roosevelt called for a White House conference to review football rules.15 President Roosevelt invited officials from the major football programs to participate.16 Deaths and injuries in football persisted, however, and Chancellor Henry MacCracken of New York University called for a national meeting of representatives of the nation’s major intercollegiate football programs to determine whether football could be regulated or had to be abolished at the intercollegiate level.17 Representatives of many major intercollegiate football programs accepted Chancellor MacCracken’s invitation and ultimately formed a Rules Committee.18 President Roosevelt then sought to have participants in the White House conference meet with the new Rules Committee.19 This combined effort on the part of educators and the White House eventually led to a concerted effort to reform intercollegiate football rules, resulting in the formation of the Intercollegiate Athletic Association (hereinafter IAA), with sixty-two original members.20 In 1910, the IAA was renamed the NCAA.21 Initially, the NCAA was formed to formulate rules that could be applied to the various intercollegiate sports.22 [Ed. Note: The NCAA’s current stated purposes are shown in Figure 1.]

In the years prior to the formation of the NCAA, schools wrestled with the same issues that we face today: the extreme pressure to win, which is compounded by the commercialization of sport, and the need for regulations and a regulatory body to ensure fairness and safety.23 In terms of regulation, between 1840 and 1910, there was a movement from loose student control of athletics to faculty oversight, from faculty oversight to the creation of conferences, and, ultimately, to the development of a national entity for governance purposes.24

B. 1910–1970

In its early years, the NCAA did not play a major role in governing intercollegiate athletics.25 It did begin to stretch beyond merely making rules for football and other games played, to the creation of a national championship event in various sports.26 Indeed, students, with some faculty oversight, continued to be the major force in running intercollegiate athletics.27 By the 1920s, however, intercollegiate athletics were quickly becoming an integral part of higher education in the United States.28 Public interest in sport at the intercollegiate level, which had always been high, continued to increase in intensity, particularly as successful and entertaining programs developed, and also with increasing access to higher education on the part of students from all segments of society.29

Figure 1 NCAA Constitution, Article 1.2: Purposes

Source: 2009–2010 NCAA Division I Manual, p. 1. © National Collegiate Athletic Association. 2008–2010. All rights reserved.

With this growing interest in intercollegiate sports and attendant increases in commercialization, outside attention again focused on governance and related issues.30 In 1929, the highly respected Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Education issued a significant report regarding intercollegiate athletics and made the following finding:

[A] change of values is needed in a field that is sodden with the commercial and the material and the vested interests that these forces have created. Commercialism in college athletics must be diminished and college sport must rise to a point where it is esteemed primarily and sincerely for the opportunities it affords to mature youth.31

The Carnegie Report, echoing themes that appear ever so relevant in the year 2000, concluded that college presidents could reclaim the integrity of sport.32 College administrators “could change the policies permitting commercialized and professionalized athletics that boards of trustees had previously sanctioned.”33

While the NCAA made some minor attempts to restructure rules to increase integrity in the governance of intercollegiate athletics, those efforts were insufficient to keep pace with the growing commercialization of, and interest in, intercollegiate athletics.34 Recruitment of athletes was not new, but the rising desire to win, with all its commercial ramifications, contributed to recruitment being raised to new heights.35 Red Grange, for example, is often given credit for “starting the competition for football talent through … recruiting.”36 Public interest in intercollegiate athletics continued to increase with support from the federal government during the 1930s. The capacity of the NCAA to regulate excesses was not equal to the daunting task presented by the growth of, interest in, and commercialization of sport.37

After World War II, with a dramatic increase in access to higher education on the part of all segments of society, largely through government support for returning military personnel to attend college, public interest expanded even more dramatically than it had in the past.38 Increased interest, not surprisingly, led to even greater commercialization of intercollegiate athletics. With the advent of television, the presence of radios in the vast majority of homes in the United States, and the broadcasting of major sporting events, these pressures further intensified.39 More colleges and universities started athletic programs, while others expanded existing programs, in an effort to respond to increasing interest in intercollegiate athletics. These factors, coupled with a series of gambling scandals and recruiting excesses, caused the NCAA to promulgate additional rules, resulting in an expansion of its governance authority.40

In 1948, the NCAA enacted the so-called “Sanity Code,” which was designed to “alleviate the proliferation of exploitive practices in the recruitment of student-athletes.”41 To enforce the rules in the Sanity Code, the NCAA created the Constitutional Compliance Committee to interpret rules and investigate possible violations.42 Neither the Sanity Code with its rules, nor the Constitutional Compliance Committee with its enforcement responsibility, were successful because their only sanction was expulsion, which was so severe that it rendered the committee impotent and the rules ineffectual.43 Recognizing this, the NCAA repealed the Sanity Code in 1951, replacing the Constitutional Compliance Committee with the Committee on Infractions, which was given broader sanctioning authority.44 Thus, in 1951, the NCAA began to exercise more earnestly the authority which it had been given by its members.45

Two other factors are worth noting in the 1950s: (1) Walter Byers became Executive Director of the NCAA, and contributed to strengthening the NCAA, and its enforcement division, over the coming years to televise intercollegiate football; and (2) the NCAA negotiated its first contract valued in excess of one million dollars, opening the door to increasingly lucrative television contracts in the future.46 The NCAA was entering a new era, in which its enforcement authority had been increased, a strong individual had been hired as executive director, and revenues from television were beginning to provide it with the wherewithal to strengthen its capacity in enforcing the rules that were being promulgated.47 Through the 1950s and 1960s, the NCAA’s enforcement capacity increased annually.48

C. 1971–1983

By 1971, as its enforcement capacity had grown yearly in response to new excesses arising from increased interest and commercialization, the NCAA was beginning to be criticized for alleged unfairness in the exercise of its enhanced enforcement authority.49 Responding to these criticisms, the NCAA formed a committee to study the enforcement process, and ultimately, in 1973, adopted recommendations developed by that committee designed to divide the prosecutorial and investigative roles of the Committee on Infractions.50 In the early 1970s, as well, the membership of the NCAA decided to create divisions, whereby schools would be placed in divisions that would better reflect their competitive capacity.51 Despite these efforts, however, by 1976, when the NCAA was given additional authority to enforce the rules by penalizing schools directly and, as a result, athletes, coaches, and administrators indirectly, criticism of the NCAA’s enforcement authority grew even more widespread.52 Indeed, in 1978, the United States House of Representatives Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigation held hearings to investigate the alleged unfairness of the NCAA’s enforcement processes.53 Once again, the NCAA responded by adopting changes in its rules designed to address many of the criticisms made during the course of the hearings.54 While concerns were somewhat abated, the NCAA’s enforcement processes continued to be the source of substantial criticism through the 1970s and 1980s.55

The NCAA found itself caught between two critiques. On the one hand, it was criticized for responding inadequately to the increased commercialization of intercollegiate athletics, with all its attendant excesses; while on the other hand, it was criticized for unfairly exercising its regulatory authority.56 Another factor began to have a major impact as well. University and college presidents were becoming more directly concerned with the operation of the NCAA for two major reasons: (1) as enrollments were beginning to drop, and expenses were increasing in athletics and elsewhere, presidents began, with some ambivalence, to see athletics as an expense, and as a potential revenue and public relations source; and (2) they personally came to understand that their reputations as presidents were often tied to the success of the athletic program and they were, therefore, becoming even more fearful of the NCAA’s enforcement authority.57

D. 1984–1999

In difficult economic times for higher education in the 1980s, university presidents increasingly found themselves caught between the pressures applied by influential members of boards of trustees and alumni, who often demanded winning athletic programs, and faculty and educators, who feared the rising commercialization of athletics and its impact on academic values.58 Many presidents were determined to take an active, collective role in the governance of the NCAA, so they formed the influential Presidents Commission in response to these pressures.59 In 1984, the Presidents Commission began to assert its authority, and by 1985, it took dramatic action by exercising their authority to call a special convention to be held in June of 1985.60 This quick assertion of power led one sports writer to conclude that “There is no doubt who is running college sports. It’s the college presidents.”61

The presidents initially were involved in a number of efforts to change the rules, particularly in the interest of cost containment.62 These efforts were not all successful.63 Over time, however, the presidents were gaining a better understanding of the workings of the NCAA, and they were beginning to take far more interest in the actual governance of intercollegiate athletics.64 A little over a decade later, the presidents’ involvement grew to the extent that they had changed the very governance structure of the NCAA, with the addition of an Executive Committee and a Board of Directors for the various divisions, both of which are made up of presidents or chief executive officers.65

….

During this time period, there were a number of additional developments that had an impact on the role of the NCAA in fulfilling its enforcement and governance of responsibilities. Even in a short history, like this one, a few of those developments are noteworthy.

As the role of television and the revenue it brings to intercollegiate athletics [have] grown in magnitude, the desire for an increasing share of those dollars has become intense. The first television event in the 1950s was a college football game, and the televising of college football games remained under the NCAA’s control for a number of years.83 In time, however, a group of powerful intercollegiate football programs were determined to challenge the NCAA’s handling of the televising of games involving their schools.84 In NCAA v. Board of Regents,85 the United States Supreme Court held that the NCAA had violated antitrust laws.86 This provided an opening for those schools, and the bowls that would ultimately court them, to directly reap the revenues from the televising of their football games.87 … Because these schools have been able to funnel more television revenues in their direction, which has led to increases in other forms of revenue, they have gained access to resources that have unbalanced the playing field in football and other sports.89

Another matter that has dramatically impacted intercollegiate athletics during the past two decades is Title IX, with its call for gender equity in intercollegiate athletics.90 With some emphasis on proportionality in opportunities and equity in expenditures for coaches and other purposes in women’s sports, new opportunities have been made available for women in intercollegiate athletics.91 The cost of these expanded opportunities has been high, however, particularly given that few institutions have women’s teams that generate sufficient revenue to cover the cost of these added programs.92 This increase in net expenses has placed significant pressure on intercollegiate athletic programs, particularly given that the presidents are cost-containment conscious, desiring that athletic programs be self-sufficient.93 Revenue producing male sports, therefore, have to bear the weight of funding women’s sports.94 This, in turn, raises racial equity concerns because most of the revenue producing male sports are made up predominantly of male student-athletes of color,95 who are expected to deliver a product that will not only produce sufficient revenue to cover its own expenses, but also a substantial portion of the costs of gender equity and male sports that are not revenue producing.96

The gender equity and television issues have been largely economic in their impact, but they do indirectly impact the role of the NCAA in governance. Since football funding has been diverted from the NCAA to the football powerhouses, the NCAA for the most part has had to rely even more heavily on its revenue from the lucrative television contract for the Division I basketball championship.97 Heavy reliance on this funding source raises racial equity issues, since student-athletes of color, particularly African-American athletes, are the source of those revenues.98 Thus, the very governance costs of the NCAA are covered predominantly by the efforts of these student-athletes of color.99 This inequity is exacerbated by the fact that schools and conferences rely heavily on revenues from the basketball tournament to fund their own institutional and conference needs.100

Generally, developments during the past two decades have focused on governance and economic issues.101 There have been some efforts, however, to enhance academic integrity and revitalize the role of faculty and students in overseeing intercollegiate athletics.102 Of particular note in this regard has been the implementation of the certification process for intercollegiate athletic programs.103 The certification process involves faculty, students (particularly student-athletes), and staff from an institution in preparing an in-depth self-study, including substantial institutional data in the form of required appendices.104 The study covers the following areas: Governance and Rules Compliance, Academic Integrity, Fiscal Integrity, and Commitment to Equity.105 This process helps institutions focus on academic values and related issues.106 These efforts also provide the chief executive officers with additional information and a potentially enhanced role in intercollegiate athletics at the campus level.107

The past two decades have been active ones for the NCAA. With meteoric rises in television and related revenues, the commercialization of intercollegiate athletics has continued to grow at a pace that places significant strain on institutions and the NCAA. These commercial pressures, together with increasing costs related to non-revenue producing sports, costly gender equity requirements, and other resource demands (e.g., new facilities), make it challenging to maintain a viable enforcement process and a balanced playing field.

III. THE FUTURE

Over the past 150 years, the desire to win at virtually any cost, combined with the increases in public interest in intercollegiate athletics, in a consumer sense, have led inexorably to a highly commercialized world of intercollegiate athletics.108 These factors have created new incentives for universities and conferences to find new ways to obtain an advantage over their competitors. This desire to gain an unfair competitive advantage has necessarily led to an expansion in rules and regulations. This proliferation of rules and the development of increasingly sophisticated regulatory systems necessary to enforce those rules, together with the importance that attaches to enforcement decisions, both economically and in terms of an institution’s reputation (and derivatively its chief executive officer’s career), places great strain on the capacity of the NCAA to govern intercollegiate athletics. This strain is unlikely to dissipate in the future because the pressures that have created the strain do not appear to be susceptible, in a practical sense, to amelioration. Indeed, the one certainty in the future of the NCAA is the likelihood that big-time intercollegiate athletics will be engaged in the same point–counterpoint that has characterized its history; increased commercialization and public pressure leading to more sophisticated rules and regulatory systems.

As rules and regulatory systems continue along the road of increased sophistication, the NCAA will more closely resemble its industry counterparts. It will develop an enforcement system that is more legalistic in its nature, as regulatory proliferation leads to increasing demands for fairness. In such a milieu, chief executive officers will have to take their responsibilities for intercollegiate athletics even more seriously.109 It can be hoped, as well, that their involvement, and the increased involvement on the part of faculty and staff, through the certification process and otherwise, will lead to a more responsible system in terms of the maintenance of academic values. If the NCAA and those who lead at the institutional and conference levels are unable to maintain academic values in the face of economics and related pressures, the government may be less than a proverbial step away.110

Notes

….

5. These regatta, which were student run for the most part, were among the first intercollegiate athletic events.

6. Rodney K. Smith, The National Collegiate Athletic Association’s Death Penalty: How Educators Punish Themselves and Others, 62 Ind. L.J. 985, 988-89 (1987) [hereinafter Smith, Death Penalty]; Rodney K. Smith, Little Ado About Something: Playing Games With the Reform of Big-Time Athletics, 20 Cap. U. L. Rev. 567, 569–70 (1991) [hereinafter Smith, Little Ado].

7. The commercialization of intercollegiate athletics, with the payment of star athletes, was rather firmly entrenched by the latter part of the 19th Century. For example, it is reported that Hogan, a successful student-athlete at Yale at that time, was compensated with: (1) a suite of rooms in the dorm; (2) free meals at the University club; (3) a one-hundred dollar scholarship; (4) the profits from the sale of programs; (5) an agency arrangement with the American Tobacco Company, under which he received a commission on cigarettes sold in New Haven; and (6) a ten-day paid vacation to Cuba. See Smith, Death Penalty, supra note 6, at 989.

8. Id. at 989–90.

9. Smith, Little Ado, supra note 6, at 570.

10. Id.

11. Id.

12. Smith, Death Penalty, supra note 6, at 990.

13. Id.

14. Id.

15. George W. Schubert et al., Sports Law 1 (1986); Smith, Death Penalty, supra note 6, at 990.

16. Smith, Death Penalty, supra note 6, at 990.

17. Id.

18. Id.

19. Id.

20. Id. at 991; Schubert, supra note 15, at 2.

21. Id.

22. Id.

23. Smith, Little Ado, supra note 6, at 571.

24. Smith, Death Penalty, supra note 6, at 989–91.

25. Id. at 991.

26. Id.

27. Id.

28. Id.

29. Id.

30. Id.

31. Id.

32. Id.

33. Id.

34. Id. at 991–92.

35. Id. at 992.

36. Id. at 992.

37. Id.

38. Id.

39. Id. at 992.

40. Id.

41. Id.

42. Id.

43. Id. at 992–93.

44. Id. at 993.

45. Id.

46. Id.

47. Id.

48. Id.

49. Id. at 992.

50. Id. at 994.

51. Id. at 993.

52. Id. at 994.

53. Id.

54. Id.

55. Id. at 995.

56. Id.

57. Id. at 995–96.

58. Id. at 995; Rodney K. Smith, Reforming Intercollegiate Athletics: A Critique of the Presidents Commission’s Role in the N.C.A.A.’s Sixth Special Convention, 64 N.D. L. Rev. 423, 427 (1988).

59. Smith, Death Penalty, supra note 6, at 996-97.

60. Smith, supra note 58, at 428-30.

61. Smith, Death Penalty, supra note 6, at 997.

62. Smith, supra note 58, at 428.

63. Id.

64. Id.

65. Manual, supra note 4, at 22–23.

….

83. Schubert, supra note 15, at 2.

84. Id.

85. 468 U.S. 85 (1984).

86. Id. at 113, 120.

87. Schubert, supra note 15, at 57–58.

….

89. It is clear that the membership of the College Football Association has been able to use those additional revenues to enhance their entire athletics program, giving them a competitive edge.

90. Rodney K. Smith, When Ignorance is Not Bliss: In Search of Racial and Gender Equity in Intercollegiate Athletics, 61 Mo. L. Rev. 329, 367 (1996).

91. Id. at 355.

92. Id. at 368.

93. Id. at 359-60.

94. Id. at 368.

95. Id. at 369–70.

96. Id. at 370.

97. Id. at 348.

98. Id. at 349.

99. Id.

100. Id. at 369-70.

101. Smith, Little Ado, supra note 6, at 573.

102. Smith, Death Penalty, supra note 6, at 1058.

103. This certification process has been in place for a number of years and is becoming institutionalized. Smith, Little Ado, supra note 6, at 573.

104. Id. at 573-74.

105. Id.

106. Id. at 576.

107. Id.

108. Smith, Death Penalty, supra note 6, at 991.

109. It can be anticipated, as well, that chief executive officers will be held increasingly accountable for rules violations at their institutions.

110. Just as the government (the legislative and judicial branches) became involved at the turn of the century and again in the 1970s, it is likely that similar oversight will occur in the future. With increased formalization of regulatory processes, the judiciary may well become more involved.

STRUCTURE

PRINCIPLES AND PRACTICE OF SPORT MANAGEMENT

Lisa Pike Masteralexis, Carol A. Barr, and Mary A. Hums

INTRODUCTION

Intercollegiate athletics is a major segment of the sport industry. It garners increasingly more television airtime as network and cable companies increase coverage of sporting events, it receives substantial coverage within the sports sections of local and national newspapers, and it attracts attention from corporations seeking potential sponsorship opportunities. Television rights fees have increased dramatically. Sport sponsorship opportunities and coaches’ compensation figures have escalated as well. The business aspect of collegiate athletics has grown immensely as administrators and coaches at all levels have become more involved in budgeting, finding revenue sources, controlling expense items, and participating in fund development activities. The administrative aspects of collegiate athletics have also changed. With more rules and regulations to be followed, there is more paperwork in such areas as recruiting and academics. These changes have led to an increase in the number of personnel and the specialization of positions in collegiate athletic departments. Although the number of athletic administrative jobs has increased across all divisions, jobs can still be hard to come by because the popularity of working in this segment of the sport industry continues to rise.

The international aspect of this sport industry segment has grown tremendously through the participation of student-athletes who are nonresident aliens (a term used by the National Collegiate Athletic Association). Coaches are more aware of international talent when recruiting. The number of nonresident alien student-athletes competing on U.S. college sports teams has grown from an average of 1.7% of the male student-athletes in all divisions in 1999–2000 to 2.6% in 2004–2005. The male sports with the most nonresident alien representation are soccer (4.9% of all male soccer student-athletes), ice hockey (13.8%), and tennis (16.6%) (National Collegiate Athletic Association [NCAA], 2006b). On female sport teams, a similar increase in the number of nonresident alien participation has occurred. In 1999–2000, 1.5% of all female student-athletes were nonresident aliens, a percentage that increased to 2.8% in 2004–2005. The sports showing the largest representation are tennis (11.5%), ice hockey (14.5%), and badminton (17.4%) (NCAA, 2006b). Athletic teams are taking overseas trips for practice and competitions at increasing rates. College athletic games are being shown internationally, and licensed merchandise can be found around the world. It is not unusual to stroll down a street in Munich, Germany, or Montpellier, France, and see a Michigan basketball jersey or a Notre Dame football jersey.

History

On August 3, 1852, on Lake Winnepesaukee in New Hampshire, a crew race between Harvard and Yale was the very first intercollegiate athletic event in the United States (Dealy, 1990). What was unusual about this contest was that Harvard University is located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Yale University is located in New Haven, Connecticut, yet the crew race took place on a lake north of these two cities, in New Hampshire. Why? Because the first intercollegiate athletic contest was sponsored by the Boston, Concord & Montreal Railroad Company, which wanted to host the race in New Hampshire so that both teams, their fans, and other spectators would have to ride the railroad to get to the event (Dealy, 1990). Thus, the first intercollegiate athletic contest involved sponsorship by a company external to sports that used the competition to enhance the company’s business.

The next sport to hold intercollegiate competitions was baseball. The first collegiate baseball contest was held in 1859 between Amherst and Williams (Davenport, 1985), two of today’s more athletically successful Division III institutions. In this game, Amherst defeated Williams by the lopsided score of 73–32 (Rader, 1990). On November 6, 1869, the first intercollegiate football game was held between Rutgers and Princeton (Davenport, 1985). This “football” contest was far from the game of football known today. The competitors were allowed to kick and dribble the ball, similar to soccer, with Rutgers “outdribbling” its opponents and winning the game six goals to four (Rader, 1990).

The initial collegiate athletic contests taking place during the 1800s were student-run events. Students organized the practices and corresponded with their peers at other institutions to arrange competitions. There were no coaches or athletic administrators assisting them. The Ivy League schools became the “power” schools in athletic competition, and football became the premier sport. Fierce rivalries developed, attracting numerous spectators. Thus, collegiate athletics evolved from games being played for student enjoyment and participation to fierce competitions involving bragging rights for individual institutions.

Colleges and universities soon realized that these intercollegiate competitions had grown in popularity and prestige and thus could bring increased publicity, student applications, and alumni donations. As the pressure to win increased, the students began to realize they needed external help. Thus, the first “coach” was hired in 1864 by the Yale crew team to help it win, especially against its rival, Harvard University. This coach, William Wood, a physical therapist by trade, introduced a rigorous training program as well as a training table (Dealy, 1990). College and university administrators also began to take a closer look at intercollegiate athletics competitions. The predominant theme at the time was still nonacceptance of these activities within the educational sphere of the institution. With no governing organization and virtually nonexistent playing and eligibility rules, mayhem often resulted. Once again the students took charge, especially in football, forming the Intercollegiate Football Association in 1876. This association was made up of students from Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and Columbia who agreed on consistent playing and eligibility rules (Dealy, 1990).

The dangerous nature of football pushed faculty and administrators to get involved in governing intercollegiate athletics. In 1881, Princeton University became the first college to form a faculty athletics committee to review football (Dealy, 1990). The committee’s choices were to either make football safer to play or ban the sport altogether. In 1887, Harvard’s Board of Overseers instructed the Harvard Faculty Athletics Committee to ban football. However, aided by many influential alumni, the Faculty Athletics Committee chose to keep the game intact (Dealy, 1990). In 1895, the Intercollegiate Conference of Faculty Representatives, better known as the Big Ten Conference, was formed to create student eligibility rules (Davenport, 1985). By the early 1900s, football on college campuses had become immensely popular, receiving a tremendous amount of attention from the students, alumni, and collegiate administrators. Nevertheless, the number of injuries and deaths occurring in football continued to increase, and it was evident that more legislative action was needed.

In 1905 during a football game involving Union College and New York University, Harold Moore, a halfback for Union College, was crushed to death. Moore was just one of 18 football players who died that year. An additional 149 serious injuries occurred (Yaeger, 1991). The chancellor of New York University, Henry Mitchell MacCracken, witnessed this incident and took it upon himself to do something about it. MacCracken sent a letter of invitation to presidents of other schools to join him for a meeting to discuss the reform or abolition of football. In December 1905, 13 presidents met and declared their intent to reform the game of football. When this group met three weeks later, 62 colleges and universities sent representatives. This group formed the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States (IAAUS) to formulate rules making football safer and more exciting to play. Seven years later, in 1912, this group took the name National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) (Yaeger, 1991).

In the 1920s, college and university administrators began recognizing intercollegiate athletics as a part of higher education and placed athletics under the purview of the physical education department (Davenport, 1985). Coaches were given academic appointments within the physical education department, and schools began to provide institutional funding for athletics. The Carnegie Reports of 1929 painted a bleak picture of intercollegiate athletics, identifying many academic abuses, recruiting abuses, payments to student-athletes, and commercialization of athletics.

The Carnegie Foundation visited 112 colleges and universities. One of the disturbing findings from this study was that although the NCAA “recommended against” both recruiting and subsidization of student-athletes, these practices were widespread among colleges and universities (Lawrence, 1987). The Carnegie Reports stated that the responsibility for control over collegiate athletics rested with the president of the college or university and with the faculty (Savage, 1929). The NCAA was pressured to change from an organization responsible for developing playing rules used in competitions to an organization that would oversee academic standards for student-athletes, monitor recruiting activities of coaches and administrators, and establish principles governing amateurism, thus alleviating the paying of student-athletes by alumni and booster groups (Lawrence, 1987).

Intercollegiate athletics experienced a number of peaks and valleys over the next 60 or so years as budgetary constraints during certain periods, such as the Great Depression and World War II, limited expenditures and growth among athletic departments and sport programs. In looking at the history of intercollegiate athletics, though, the major trends during these years were increased spectator appeal, commercialism, media coverage, alumni involvement, and funding. As these changes occurred, the majority of intercollegiate athletic departments moved from a unit within the physical education department to a recognized, funded department on campus.

Increased commercialism and the potential for monetary gain in collegiate athletics led to increased pressure on coaches to win. As a result, collegiate athletics experienced various problems with rule violations and academic abuses involving student-athletes. As these abuses increased, the public began to perceive that the integrity of higher education was being threatened. In 1989, pollster Louis Harris found that 78% of Americans thought collegiate athletics were out of hand. This same poll found that nearly two-thirds of Americans believed that state or federal legislation was needed to control college sports (Knight Foundation, 1993). In response, on October 19, 1989, the Trustees of the Knight Foundation created the Knight Commission, directing it to propose a reform agenda for intercollegiate athletics (Knight Foundation, 1991). The Knight Commission was composed of university presidents, CEOs and presidents of corporations, and a congressional representative. The reform agenda recommended by the Knight Commission played a major role in supporting legislation to alleviate improper activities and emphasized institutional control in an attempt to restore the integrity of collegiate sports. The Knight Commission’s work and recommendations prompted the NCAA membership to pass numerous rules and regulations regarding recruiting activities, academic standards, and financial practices.

Whether improvements have occurred within college athletics as a result of the Knight Commission reform movement and increased presidential involvement has been debated among various constituencies over the years. Proponents of the NCAA and college athletics cite the skill development, increased health benefits, and positive social elements that participation in college athletics brings. In addition, the entertainment value of games and the improved graduation rates of college athletes (although men’s basketball and football rates are still a focus of concern) in comparison with the student body overall are referenced. Those critical of college athletics, though, cite the continual recruiting violations, academic abuses, and behavioral problems of athletes and coaches. These critics are concerned with the commercialization and exploitation of student-athletes as well….

….

ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE AND GOVERNANCE

The NCAA

The primary rule-making body for college athletics in the United States is the NCAA. Other college athletic organizations include the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA), founded in 1940 for small colleges and universities and having approximately 277 member institutions (National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics, 2006), and the National Junior College Athletic Association (NJCAA), founded in 1937 to promote and supervise a national program of junior college sports and activities and currently having approximately 550 member institutions (National Junior College Athletic Association, 2003).

The NCAA is a voluntary association with more than 1,200 institutions, conferences, organizations, and individual members…. All collegiate athletics teams, conferences, coaches, administrators, and athletes participating in NCAA-sponsored sports must abide by the association’s rules.

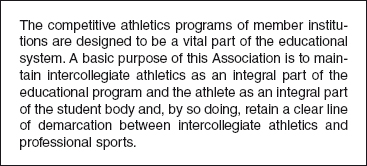

The basic purpose of the NCAA as dictated in its constitution is to “maintain intercollegiate athletics as an integral part of the educational program and the athlete as an integral part of the student body and, by so doing, retain a clear line of demarcation between intercollegiate athletics and professional sports” (NCAA, 2005b, p. 1). Important to this basic purpose are the cornerstones of the NCAA’s philosophy—namely, that college athletics are amateur competitions and that athletics are an important component of the institution’s educational mission. [Ed. Note: The fully stated basic purpose is shown in Figure 2.]

Figure 2 NCAA Constitution, Article 1.3.1: Basic Purpose

Source: 2009–2010 NCAA Division I Manual, p. 1. © National Collegiate Athletic Association. 2008–2010. All rights reserved.

The NCAA has undergone organizational changes throughout its history in an attempt to improve the efficiency of its service to member institutions. In 1956, the NCAA split its membership into a University Division, for larger schools, and a College Division, for smaller schools, in an effort to address competitive inequities. In 1973, the current three-division system, made up of Division I, Division II, and Division III, was created to increase the flexibility of the NCAA in addressing the needs and interests of schools of varying size (“Study: Typical I-A Program,” 1996). This NCAA organizational structure involved all member schools and conferences voting on legislation once every year at the NCAA annual convention. Every member school and conference had one vote, assigned to the institution’s president or CEO, a structure called one-school/one-vote.

In 1995, the NCAA recognized that Divisions I, II, and III still faced “issues and needs unique to its member institutions,” leading the NCAA to pass Proposal 7, “Restructuring,” at the 1996 NCAA convention (Crowley, 1995). The restructuring plan, which took effect in August 1997, gave the NCAA divisions more responsibility for conduct within their division, gave more control to the presidents of member colleges and universities, and eliminated the one-school/one-vote structure. The NCAA annual convention of all member schools still takes place, but the divisions also hold division-specific mini-conventions or meetings. In addition, each division has a governing body called either the Board of Directors or Presidents Council, as well as a Management Council made up of presidents, CEOs, and athletic directors from member schools who meet and dictate policy and legislation within that division. The NCAA Executive Committee, consisting of representatives from each division as well as the NCAA Executive Director and chairs of each divisional Management Council, oversees the Presidential boards and Management Councils for each division.

Under the unique governance structure of the NCAA, the member schools oversee legislation regarding the conduct of intercollegiate athletics. Member institutions and conferences vote on proposed legislation, thus dictating the rules they need to follow. The NCAA National Office, located in Indianapolis, Indiana, enforces the rules the membership passes. Approximately 350 employees work at the NCAA National Office administering the policies, decisions, and legislation passed by the membership, as well as providing administrative services to all NCAA committees, member institutions, and conferences (NCAA, 2004c). The NCAA National Office is organized into departments, including administration, business, championships, communications, compliance, enforcement, educational resources, publishing, legislative services, and visitors center/special projects.

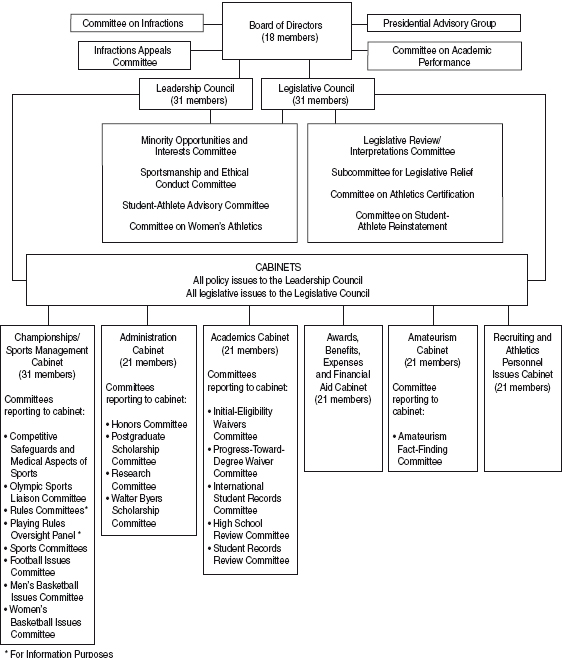

Two of the more prominent areas within the NCAA administrative structure are legislative services and enforcement. These two areas are pivotal because they deal with interpreting new NCAA legislation and enforcing these rules and regulations….

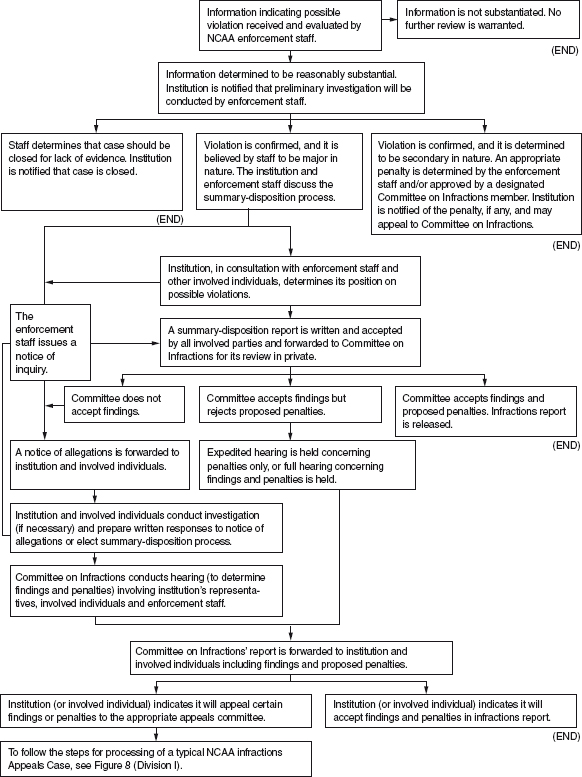

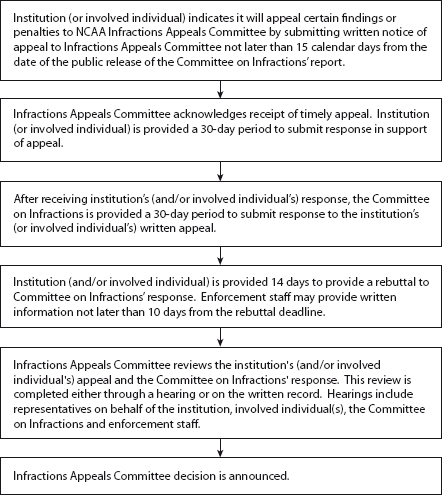

The enforcement area was created in 1952 when the membership decided that such a mechanism was needed to enforce the association’s legislation. The process consists of allegations of rules violations being referred to the association’s investigative staff. The NCAA enforcement staff determines if a potential violation has occurred, with the institution being notified of such finding and the enforcement staff submitting its findings to the Committee on Infractions (NCAA, 2005g). The institution may also conduct its own investigation, reporting its findings to the Committee on Infractions.

If a violation is found, it may be classified as a secondary or a major violation. A secondary violation is defined as “a violation that is isolated or inadvertent in nature, provides or is intended to provide only a minimal recruiting, competitive or other advantage and does not include any significant recruiting inducement or extra benefit” (NCAA, 2005g, p. 343). A major violation is defined as “[A]ll violations other than secondary violations …, specifically those that provide an extensive recruiting or competitive advantage” (NCAA, 2005g, p. 344).

It is important to note that although the NCAA National Office staff members collect information and conduct investigations on possible rule violations, the matter still goes before the Committee on Infractions, a committee of peers (representatives of member institutions), which determines responsibility and assesses penalties. Penalties for secondary violations may include, among others, an athlete sitting out for a period of time, forfeiture of games, an institutional fine, or suspension of a coach for one or more competitions. Major violations carry more severe penalties to an institution, including, among others, bans from postseason play, an institutional fine, scholarship reductions, and recruiting restrictions.

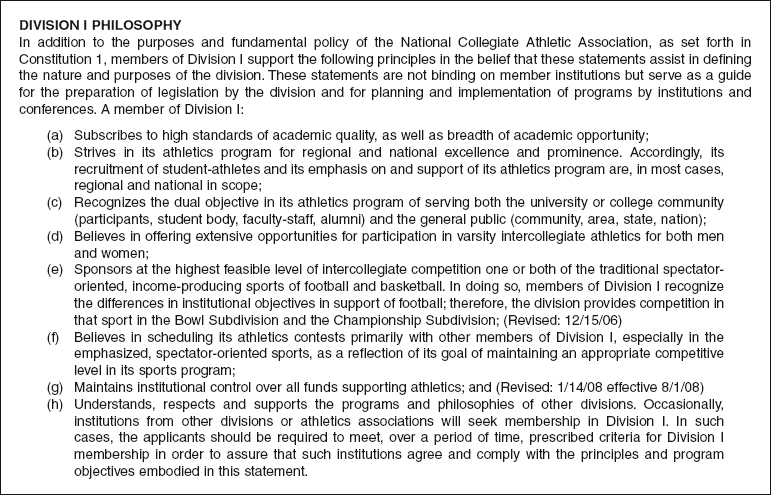

Divisions I, II, and III

The latest NCAA organizational restructuring, which became effective in 1997, called for divisions to take more responsibility and control over their activities. This was due to the recognition of substantial differences among the divisions, both in terms of their philosophies as well as the way they do business. A few of the more prominent differences among divisions are highlighted in this section…. Each institution has its own philosophy regarding the structure and governance of its athletic department. In addition, generalizations regarding divisions are not applicable to all institutions within that division. For example, some Division III institutions, although not offering any athletic scholarships, can be described as following a nationally competitive, revenue-producing philosophy that is more in line with a Division I philosophy…. [Ed. Note: See Figure 3.]

Division I member institutions, in general, support the philosophy of competitiveness, generating revenue through athletics, and national success. This philosophy is reflected in the following principles taken from the Division I Philosophy Statement (NCAA, 2005h):

Figure 3 NCAA Division I Philosophy Statement

Source: 2009–2010 NCAA Division I Manual, p. 308. © National Collegiate Athletic Association. 2008–2010. All rights reserved.

• Strives in its athletics program for regional and national excellence and prominence

• Recognizes the dual objective in its athletics program of serving both the university or college community (participants, student body, faculty-staff, alumni) and the general public (community, area, state, nation)

….

• Strives to finance its athletics program insofar as possible from revenues generated by the program itself

Division I schools that have football are further divided into two subdivisions: Division I-A, Football Bowl Division, is the category for the somewhat larger football-playing schools in Division I, and Division I-AA, Football Championship Division, is the category for institutions playing football at the next level. Division I-A institutions must meet minimum attendance requirements for football, whereas Division I-AA institutions are not held to any attendance requirements. Division I institutions that do not sponsor a football team are often referred to as Division I-AAA.

Division II institutions usually attract student-athletes from the local or in-state area who may receive some athletic scholarship money but usually not a full ride. Division II athletics programs are financed in the institution’s budget like other academic departments on campus. Traditional rivalries with regional institutions dominate schedules (NCAA, 2004d).

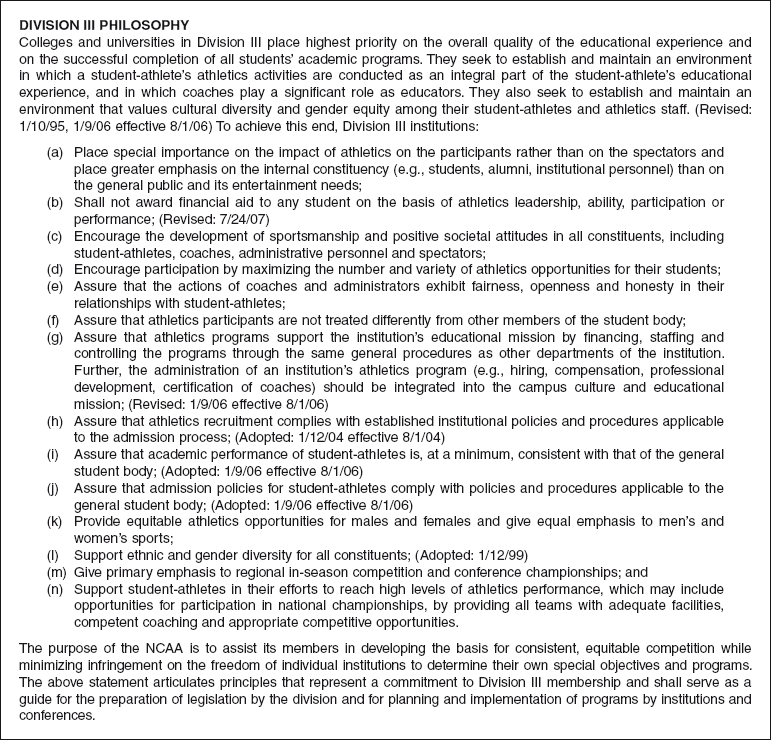

Division III institutions do not allow athletic scholarships and encourage participation by maximizing the number and variety of athletics opportunities available to students. [Ed. Note: See Figure 4.] Division III institutions also emphasize the participant’s experience, rather than the experience of the spectator, and place primary emphasis on regional in-season and conference competition (NCAA, 2004d).

Beyond the different philosophies just discussed, it is important to note some of the other differences that exist among the divisions. Division I athletic departments are usually larger in terms of the number of sport programs sponsored, the number of coaches, and the number of administrators. Division I member institutions have to sponsor at least seven sports of all-male or mixed-gender teams and seven all-female teams, or six sports of all-male or mixed-gender teams and eight all-female teams. Division I-A football-playing institutions must sponsor a minimum of 16 sports, including a minimum of six sports involving all-male or mixed-gender teams and a minimum of eight all-female teams (NCAA, 2005i). Division I athletic departments also have larger budgets due to the number of athletic scholarships allowed, the operational budgets needed for the larger number of sport programs sponsored, and the salary costs associated with the larger number of coaches and administrators. Division II institutions have to sponsor at least four men’s sports and four women’s sports, and allow athletic scholarships but on a more modest basis than Division I. Division III institutions have to sponsor five sports for men and five sports for women and do not allow athletic scholarships.

Figure 4 NCAA Division III Philosophy Statement

Source: 2009–2010 NCAA Division III Manual, p. vii. © National Collegiate Athletic Association. 2008–2010. All rights reserved.

Conferences

The organizational structure of intercollegiate athletics also involves member conferences of the NCAA. Member conferences must have a minimum of six member institutions within a single division to be recognized as a voting member conference of the NCAA (NCAA, 2005c). Conferences provide many benefits and services to their member institutions. For example, conferences have their own compliance director and run seminars regarding NCAA rules and regulations in an effort to better educate member schools’ coaches and administrators. Conferences also have legislative power over their member institutions in the running of championship events and the formulation of conference rules and regulations. Conferences sponsor championships in sports sponsored by the member institutions within the conference. The conference member institutions vote on the conference guidelines to determine the organization of these conference championships. Conferences may also provide a revenue-sharing program to their member institutions in which revenue realized by the conference through NCAA distributions, TV contracts, or participation in football bowl games is shared among all member institutions….

Conferences have their own conference rules. Member institutions of a particular conference must adhere to conference rules in addition to NCAA rules. It is important to note, though, that although a conference rule can never be less restrictive than an NCAA rule, many conferences maintain additional rules that hold member institutions to stricter standards. For example, the Ivy League is a Division I NCAA member conference, but it prohibits its member institutions from providing athletic scholarships to student-athletes. Therefore, the Ivy League schools, although competing against other Division I schools that allow athletic scholarships, do not allow their athletic departments to award athletic scholarships.

Conference realignment is one of the … issues affecting collegiate athletic departments. Over a six-month period from June 2003 through December 2003, about 20 Division I-A schools alone changed conferences (Rosenberg, 2003). Some of the reasons for a school’s wanting to join a conference or change conference affiliation are (1) exposure from television contracts with existing conferences, (2) potential for more revenue from television and corporate sponsorships through conference revenue sharing, (3) the difficulty independent schools experience in scheduling games and generating revenue, and (4) the ability of a conference to hold a championship game in football, which can generate millions of dollars in revenue for the conference schools if the conference possesses at least 12 member institutions.

One of the biggest conference realignments involved the demise of the 80-year-old Southwest Conference. In 1990, the Southwest Conference (SWC) comprised nine member schools (Mott, 1994). In August 1990, the University of Arkansas accepted a bid to leave the Southwest Conference and join the Southeast Conference (SEC). The university stated that the SEC gave it bigger crowds in revenue-producing sports and more national exposure (“Broyles Hopes,” 1990). In 1994, four Southwest Conference schools—Texas, Texas A&M, Baylor, and Texas Tech—announced they were leaving to join the Big Eight Conference (Mott, 1994). In April 1994, three other SWC schools—Rice, Texas Christian University, and Southern Methodist University—joined the Western Athletic Conference (WAC) (“Western Athletic,” 1994). Thus, the Southwest Conference had lost all of its member schools except Houston. This led to the demise of the Southwest Conference because it dropped below the six-member school minimum required by the NCAA for recognition as a member conference. Houston, the sole remaining SWC school, joined Conference USA in 1995.

The demise of the Southwest Conference due to conference realignment has been rivaled recently with the 2003–2004 realignment that has affected six Division I-A conferences. This realignment was initiated by the movement of the University of Miami, Virginia Tech, and Boston College from the Big East Conference to the Atlantic Coast Conference. With three of its eight football-playing schools leaving for the ACC, the Big East invited five schools from Conference USA (Cincinnati, Louisville, South Florida, Marquette, and DePaul) to join it (Lee, 2003). Conference USA also lost two schools, St. Louis and University of North Carolina–Charlotte, to the Atlantic 10 Conference. Conference USA subsequently went looking for schools for its conference, with Marshall and Central Florida from the Mid-American Conference, and Southern Methodist University, Tulsa, Texas–El Paso, and Rice from the Western Athletic Conference accepting the invitation (Watkins, 2004). The Western Athletic Conference added New Mexico State and Utah State from the Sun Belt Conference (Lee, 2003). There is sure to be more conference shuffling among NCAA member institutions as the conferences seek stability.

….

Title IX/Gender Equity

Perhaps no greater issue has affected collegiate athletic departments over the past couple of decades than Title IX or gender equity…. Title IX is a federal law passed in 1972 that prohibits sex discrimination in any educational activity or program receiving federal financial assistance. Early in its history, there was much confusion as to whether Title IX applied to college athletic departments. Title IX gained its enforcement power among college athletic departments with the passage of the 1988 Civil Rights Restoration Act. In 1991, the NCAA released the results of a gender-equity study that found that although the undergraduate enrollment on college campuses was roughly 50% male and 50% female, collegiate athletic departments on average were made up of 70% male and 30% female student-athletes. In addition, this NCAA study found that the male student-athletes were receiving 70% of the athletic scholarship money, 77% of the operational budget, and 83% of the recruiting dollars available (NCAA Gender Equity Task Force, 1991). In response to such statistics, an increase in the number of sex discrimination lawsuits took place, with the courts often ruling in favor of the female student-athletes.

Collegiate athletic administrators started to realize that Title IX would be enforced by the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) and the courts, and as athletic administrators they would be required to provide equity within their athletic departments. The struggle athletic administrators are faced with is how to comply with Title IX given institutional financial limitations, knowing that lack of funding is not an excuse for not complying with Title IX. To bring male and female participation numbers closer to the percentage of undergraduate students by sex at the institution, numerous institutions are choosing to eliminate sport programs for men, thereby reducing the participation and funding on the men’s side. Another method selected by some institutions is capping roster sizes for men’s teams, known as roster management, thus keeping the men’s numbers in check while trying to increase women’s participation. A third, and most appropriate, option under Title IX is increasing participation and funding opportunities for female student-athletes. Of course, in selecting this option, the athletic administrator must be able to raise the funds necessary to add sport programs, hire new coaches, and provide uniforms for the new sport programs.

The debate surrounding Title IX continues, with numerous organizations (e.g., the National Women’s Law Center, Women’s Sports Foundation, and National Organization for Women), as well as advocates within the college athletic setting, arguing the merits of Title IX and that the appropriate enforcement methods are being used. In contrast, though, organizations such as USA Gymnastics and the National Wrestling Coaches Association are concerned about the effects Title IX has had on their sport (men’s teams) and in particular are questioning the appropriateness of certain Title IX compliance standards. About 400 men’s college teams were eliminated during the 1990s, with the sport of men’s wrestling being hit particularly hard. The National Wrestling Coaches Association filed a lawsuit against the Department of Education arguing that the male student-athletes were being discriminated against as a result of the Title IX enforcement standards directly causing a reduction in men’s sports. This lawsuit was dismissed in May 2004, with an appeals court panel ruling that the parties lacked standing to file the lawsuit, which instead should be litigated against individual colleges that eliminated men’s sports (“Appeals Court,” 2004). To date, these types of lawsuits have not been effective for male student-athletes. In May 2004, Myles Brand, [then] president of the NCAA, endorsed Title IX while speaking at a meeting of the National Wrestling Coaches Association, stating that it should not be used as an excuse or a cause for elimination of sport programs. Instead, these are institutional decisions reflected in the statistic that although the number of men’s wrestling and gymnastics teams, among others, has declined over the past two decades (from 363 to 222), the number of football teams over the same time period has increased (from 497 to 619) (“Brand Defends Title IX,” 2004).

A study by The Chronicle of Higher Education in 1995–1996 found that undergraduate enrollment on college campuses was 53% women, yet athletic departments were made up of 63% male student-athletes and 37% female student-athletes, with the women student-athletes receiving 38% of athletic scholarship funding (Naughton, 1997). More recently, the 2003–2004 NCAA Gender Equity Report found undergraduate enrollments at Division I schools to be 53.4% female, while student-athletes were 44% female. In addition, female student-athletes in 2003–2004 were receiving 45% of the athletic scholarship funding (NCAA, 2006c). Although these recent statistics do indicate improvements in gender equity, there is still much work to be done. Collegiate athletic administrators must continue to address this issue and develop strategies within their athletic departments to comply with Title IX and achieve gender equity.

Hiring Practices for Minorities and Women

In December 2003, Sylvester Croom became the first African American head football coach in the 71-year history of the Southeastern Conference (Longman & Glier, 2003). The hiring of Croom was a much needed milestone for the SEC, the last major conference to hire a black football coach. But it signified only a small step in the progress toward improvement that still needs to take place. The hiring of Mario Cristobal at Florida International and Randy Shannon at the University of Miami in December 2006 brought the total number of minority Division I-A head football coaches to 7 out of 119 positions (O’Toole, 2006).

Minority hiring has long been an issue of concern and debate within collegiate athletics. In 1993–1994, the NCAA’s Minority Opportunity and Interests Committee found that African Americans accounted for fewer than 10% of athletic directors and 8% of head coaches, and when predominantly African American institutions were eliminated from the study, the results dropped to 4% representation in both categories (Wieberg, 1994). Not much improvement, if any, has taken place….

The Black Coaches’ Association (BCA) announced in October 2003 the establishment of a “hiring report card” to monitor football hiring practices at major institutions. Grades are based on contact with the BCA during the hiring process, efforts to interview candidates of color, the number of minorities involved in the hiring process, the time frame for each search, and adherence to institutional affirmative action hiring policies (Dufresne, 2003).

Women have also lacked appropriate representation among administrators at the collegiate level…. This issue continues to demand—appropriately so—the attention of college athletic directors, in the hiring of coaches, and of institutional presidents, in the hiring of athletic directors.

Academic Reform

Since the early 1990s and the publication of the Knight Commission reports that criticized the NCAA’s academic legislation and academic preparation of student-athletes, the NCAA has been involved in numerous academic reform measures. The Knight Commission noted that although Proposition 48 was in place (to be eligible to play his or her first year in college, the student-athlete was required to possess a 2.0 minimum grade-point average [GPA] in 11 high school core curriculum courses while also meeting a minimum 700 SAT standard [equates to an 820 score under the “revised” SAT]), student-athlete graduation rates were low. Student-athletes could maintain eligibility to compete in athletics while not adequately progressing toward a degree (Knight Foundation, 1991). Satisfactory progress requirements were added, requiring student-athletes to possess a minimum GPA while taking an appropriate percentage of degree-required courses each year.

In response to concern that the SAT may be biased and in an attempt to increase the graduation rates of student-athletes, Proposition 16 went into effect in 1996–1997. This initial eligibility academic legislation required student-athletes to possess a minimum GPA in 13 core courses, with a corresponding SAT score along a sliding scale. If the student-athlete had a minimum GPA of 2.0, he or she needed a minimum SAT score of 1010. The student-athlete would then need to possess a corresponding GPA and SAT score along a scale to the minimum SAT of 820, which corresponded with a 2.5 GPA requirement. This legislation was changed through Bylaw 14.3, which became effective for all student-athletes entering a collegiate institution on or after August 1, 2005. Bylaw 14.3 requires student-athletes to meet a minimum GPA standard in 14 core courses, with a corresponding SAT score, but the sliding scale was changed to range from a 2.0 GPA with a 1010 SAT minimum to a 3.55 GPA with a minimum 400 SAT (NCAA, 2005f). In addition, satisfactory progress requirements were made more stringent to push student-athletes toward graduating within six years.

The NCAA initiated the latest academic reform proposal, the Academic Progress Rate (APR) or incentive/disincentive plan, in the fall of 2004. The new system collects data on a team’s academic results based on eligibility and retention of student-athletes from the previous academic year. Results are then tied to recruiting opportunities, number of athletic scholarships, postseason eligibility, and NCAA revenue distribution (Alesia, 2004). The academic progress rate is calculated by awarding up to two points per student-athlete per semester or quarter (one point for being enrolled and one point for being on track to graduate). The total points earned are divided by the total possible points. A team can be subject to penalties if its score falls below 925, a figure the NCAA calculates as a predictor of a 60% graduation rate (Timanus, 2006). Penalties, such as a reduction in the maximum number of financial aid counters a sport is permitted to award, began in 2006–2007 and were based on three years of data.

In October 2005, the NCAA Division I Board of Directors approved a plan to spend up to $10 million annually on a program intended to help more college athletes graduate. The NCAA plans to give half of the money ($5 million annually) to institutions whose athletics programs make big improvements in their academic performance over the previous year. An additional $3 million would go to colleges that can demonstrate that they need money for tutors or programs that help athletes do well in the classroom. The rest of the money would reward athletics programs that are already doing well, with individual institutions receiving a maximum of $100,000 each (Wolverton, 2005).

Academic progress, academic preparations, and the graduation rate of student-athletes will continue to be issues of importance as college athletics and the educational mission of colleges and universities continue to coexist.

….

References

….

Alesia, M. (2004, January 10). NCAA thinks new system can aid academics. The Indianapolis Star. Retrieved on January 12, 2004, from http://www.indystar.com/articles/1/110210-4641-P.html

Appeals court: Individual colleges to blame for cuts. (2004, May 14). ESPN.com. Retrieved on May 17, 2004, from http://sports.espn.go.com/epsn/news/story?id;eq1801717

….

Brand defends Title IX. (2004, May 21). LubbockOnline.com. Retrieved on May 21, 2004, from http://www.lubbockonline.com

Broyles hopes a move won’t end Arkansas’ SWC rivalries. (1990, August 1). The NCAA News, p. 20.

Crowley, J. N. (1995, December 18). History demonstrates that change is good. The NCAA News, p. 4.

….

Davenport, J. (1985). From crew to commercialism—the paradox of sport in higher education. In D. Chu, J. O. Segrave, & B. J. Becker (Eds.), Sport and higher education (pp. 5–16). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Dealy, F. X. (1990). Win at any cost. New York: Carol Publishing Group.

Dufresne, C. (2003, October 22). BCA to grade hiring efforts. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved on October 22, 2003, from http://www.latimes.com/sports/la-sp-bca22oct22,1,1607383

….

Knight Foundation Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics. (1991, March). Keeping faith with the student-athlete. Charlotte, NC: Knight Foundation.

Knight Foundation Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics. (1993, March). A new beginning for a new century. Charlotte, NC: Knight Foundation.

….

Lawrence, P. R. (1987). Unsportsmanlike conduct. New York: Praeger Publishers.

Lee, J. (2003, December 8–14). Who pays, who profits in realignment? SportsBusiness Journal, 25–33.

Longman, J., & Glier, R. (2003, December 2). The S.E.C. has its first black football coach. The New York Times. Retrieved on December 2, 2003, from http://www.nytimes.com/2003/12/02/sports/ncaafootball/02CROO.html

….

Mott, R. D. (1994, March 2). Big Eight growth brings a new look to Division I-A. The NCAA News, p. 1.

National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics. (2006). About the NAIA. Retrieved on September 23, 2006, from http://naia.cstv.com/member-services/about/members.htm

….

National Collegiate Athletic Association. (2004c). The history of the NCAA. Retrieved on June 14, 2004, from http://www.ncaa.org/about/history.html

National Collegiate Athletic Association. (2004d). What’s the difference between Division I, II, and III? Retrieved on June 14, 2004, from http://www.ncaa.org/about/div_criteria.html

….

National Collegiate Athletic Association. (2005b). Article 1.3.1: Basic purpose. In 2005–06 NCAA Division I manual. Indianapolis, IN: Author.

National Collegiate Athletic Association. (2005c). Article 3.3.2.2.2.1: Full voting privileges. In 2005–06 NCAA Division I manual. Indianapolis, IN: Author.

….

National Collegiate Athletic Association. (2005f). Article 14.3: Freshman academic requirements. In 2005–06 NCAA Division I manual. Indianapolis, IN: Author.

National Collegiate Athletic Association. (2005g). Article 19.02.2: Types of violations. In 2005–06 NCAA Division I manual. Indianapolis, IN: Author.

National Collegiate Athletic Association. (2005h). Article 20.9: Division I philosophy statement. In 2005–06 NCAA Division I manual. Indianapolis, IN: Author.

National Collegiate Athletic Association. (2005i). Article 20.9.6: Division I-A football requirements. In 2005–06 NCAA Division I manual. Indianapolis, IN: Author.

….

National Collegiate Athletic Association. (2006b). 1999–00-2004–05 NCAA race and ethnicity report. Retrieved on November 1, 2006, from http://www.ncaa.org/library/research/ethnicity_report/index.html

National Collegiate Athletic Association. (2006c). 2003–04 NCAA gender-equity report. Retrieved on February 9, 2007, from http://www.ncaa.org/library/research/gender_equity_study/2003-04/2003-04_gender_equity_report.pdf

….

National Collegiate Athletic Association. (2006g). NCAA enforcement/infractions. Retrieved on October 1, 2006, from http://www.ncaa.org/enforcement

….

National Junior College Athletic Association. (2003). NJCAA history. Retrieved on August 1, 2003, from http://www.njcaa.org/history.cfm

NCAA Gender Equity Task Force. (1991). NCAA gender equity report. Overland Park, KS: National Collegiate Athletic Association.

Naughton, J. (1997, April 11). Women in Division I sport programs: “The glass is half empty and half full.” The Chronicle of Higher Education, pp. A39–A40.

O’Toole, T. (2006, December 20). Division I-A minority coaches grows to seven. USA Today, p. C1.

….

Rader, B. G. (1990). American sports (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Rosenberg, B. (2003, December 8). Domino effect: Division I-A conference realignment has had emotional, structural impact. The NCAA News. Retrieved on June 14, 2004, from http://www.ncaa.org/news/2003/20031208/active/4025n03.html

….

Savage, H. J. (1929). American college athletics. New York: The Carnegie Foundation.

….

Study: Typical I-A program is $1.2 million in the black. (1996, November 18). The NCAA News, p. 1.

Timanus, E. (2006, March 2). Academic sanctions to hit 65 schools. USA Today, p. 1C.

….

Watkins, C. (2004, May 1). UTEP accepts invitation to join C-USA. The Dallas Morning News. Retrieved on May 4, 2004, from http://www.dallasnews.com/cgi-bin/bi/gold_print.cgi

Western Athletic Conference to become biggest in I-A. (1994, April 27). The NCAA News, p. 3.

Wieberg, S. (1994, August 18). Study faults colleges on minority hiring. USA Today, p. 1C.

Wolverton, B. (2005, November 11). NCAA will pay colleges that raise athletes’ academic performance. The Chronicle of Higher Education, p. A39.

Yaeger, D. (1991). Undue process: The NCAA’s injustice for all. Champaign, IL: Sagamore Publishing.

SPORTS LAW: CASES AND MATERIALS

Ray Yasser, James R. McCurdy, C. Peter Goplerud, and Maureen A. Weston

B. NATIONAL COLLEGIATE ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION-AUTHORITY AND RULES

1. Overview of the Association and Its Structure

The NCAA is an unincorporated, voluntary, private association, consisting of nearly one thousand members. Members are predominantly colleges and universities, both public and private. Athletic conferences are also members of the NCAA. Public universities constitute approximately 55 percent of the membership. All member schools and conferences are required to pay dues, the amounts varying depending upon the division in which membership is held. The association is divided into three divisions: Division I, Division II, and Division III. Division I is itself divided into Division I-A, I-AA, and I-AAA. The organization has a large permanent professional staff, with discrete departments for administration, business, championships, communications, compliance services, enforcement, legislative services, and publishing. The association is headquartered in Indianapolis.

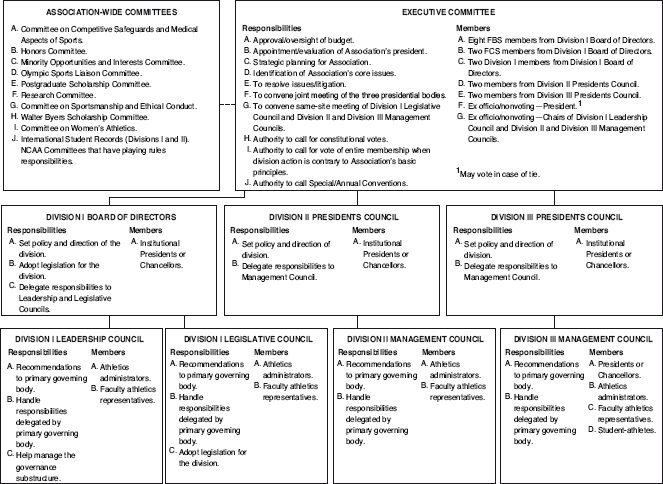

The membership governs the organization, and since 1997, it is essentially a federation system, with each division governing itself on nearly all issues. [Ed. Note: The NCAA governance structure is shown in Figure 5.] There is, however, an Executive Committee which presides over the entire organization. It consists of 20 members. The Executive Director and the chairs of the three divisional Management Councils serve as ex officio nonvoting members. The other sixteen members include 8 Division I-A CEO’s from the Division I Board of Directors, 2 Division I-AA CEO’s from the Board, 2 Division I-AAA CEO’s from the Board, 2 Division II CEO’s from the Division II Presidents Council, and 2 Division III CEO’s from the Division III Presidents Council.

The Executive Committee is to:

(a) Provide final approval and oversight of the Association’s budget;

(b) Employ the Association’s chief executive officer (e.g. executive director), who shall be administratively responsible to the Executive Committee and who shall be authorized to employ such other persons as may be necessary to conduct efficiently the business of the Association;

(c) Provide strategic planning for the Association as a whole;

(d) Identify core issues that affect the Association as a whole;

(e) Act on behalf of the Association to resolve core issues and other Association-wide matters;

(f) Initiate and settle litigation;

(g) Convene at least one combined meeting per year of the divisional presidential governing bodies;

(h) Convene at least one same-site meeting per year of the three divisional Management Councils;

(i) Forward proposed amendments to Constitutions 1 and 2 and other dominant legislation to the entire membership for a vote;

(j) Call for a vote of the entire membership on the action of any division that it determines to be contrary to the basic purposes, fundamental policies, and general principles set forth in the Association’s Constitution. This action may be overridden by the Association’s entire membership by a two-thirds majority vote of those institutions voting; and

(k) Call for an annual or special Convention of the Association.1

Division I is composed of the schools which are the most visible athletic competitors, the so-called “big time programs.” For Division I, the primary rule making body in the new NCAA structure is a Board of Directors, made up of eighteen CEO’s from Division I member institutions. [Ed. Note: The Division I governance structure is shown in Figure 6.] The following eight conferences have one representative each on the Board: Atlantic Coast Conference, Big East, Big 12, Big 10, Pac-10, Southeastern, Western Athletic Conference, and Conference USA. One member must come from either the Big West or Mid-American Conferences. The remaining six members come from Division I-AA and I-AAA (Division I schools which do not play Division I football). Each conference in the latter divisions must be represented on either the Board or the Management Council.