CHAPTER FIVE

Revenue Sharing and Competitive Balance

INTRODUCTION

No matter the structure, all professional sports leagues are deeply concerned about the same two basic issues: competitive balance and revenue sharing. With an understanding of the background and structure of leagues provided in the previous chapters, the reader can now give greater attention to revenue sharing policies and competitive balance issues. One way of thinking about revenue sharing is to define it as the amount of revenues earned by members of a professional sports league that are shared by all league teams, regardless of the teams’ contributions to the generation of these revenues. Another way to consider revenue sharing is to focus on the amount of money that teams pay each other for the right to play each other.

The history of revenue sharing is interesting. The equalizing of television revenues was first proposed at the MLB owners meetings in 1952 by Bill Veeck (then the owner of the small-revenue St. Louis Browns): “It is my contention that the Browns provide half the cast in every game they play. Therefore, we’re entitled to our cut of the TV fees the home club receives for televising our games. Morally, I know I am right, and I plan to fight this thing to the end.”1 To this, Brooklyn Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley responded: “You’re a damned communist.”2 Veeck’s retort was telling:

Under this system they want to continue the rich clubs get richer and the poor clubs continue poor. With all that television money they’re getting the Yanks can continue to keep outbidding us for talent. They’ve signed $500,000 worth of bonus players in the last couple of years, paying for ’em out of the TV money we help provide. We poorer clubs are helping cut our own throats. None of us is ever going to catch up with the Yankees at that rate.3

Ultimately, Veeck lost this argument, and his proposed 50-50 split of television revenues was voted down by the MLB owners. Nonetheless, an important seed was planted in the mind of baseball executive Branch Rickey that would prove important when he became one of the entrepreneurs behind the contemplated Continental League later in the decade. Rickey proposed using a 33% team–67% league split of television revenues. His guiding philosophy that provided the rationale for revenue sharing was that: “any rule or regulation that removes or tends to remove the power of money to make the difference in playing strength is a good rule.”4

Although the Continental League was never launched, it, too, was influential in the evolution of revenue sharing, because it provided the basis for sports entrepreneur Lamar Hunt’s proposal for the pooling and equal sharing of television revenues in his newly formed American Football League.5 The AFL ultimately adopted this proposal and sold its pooled television rights in 1960 for $8.5 million over 5 years, which provided each of the 10 teams in the league with $170,000 annually. Comparatively, the television rights in the established, rival NFL were sold by the teams on an individual basis. In 1960, the Baltimore Colts had a $600,000 per year contract with NBC and 9 of the 12 NFL teams had contracts with CBS. The teams acted as competitors in the television marketplace rather than as a unified entity. The New York Giants received $175,000 and the Green Bay Packers only $75,000 from CBS for their broadcasting rights. This is especially relevant given what the startup AFL teams were receiving. This led NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle to adopt the “League Think” philosophy that became a hallmark of his longtime tenure as commissioner. He successfully persuaded even the largest NFL teams to sacrifice their short-term revenues for long-term growth. This required some teams to forsake—at least in the short-term—hundreds of thousands of dollars in television revenues. He was able to convince them that the strength of the league as a collective entity was more important than the strength of any one team. When legal precedent prevented the NFL from entering into the league-wide television contract that Rozelle envisioned, he successfully lobbied Congress for the passage of the Sports Broadcasting Act of 1961, which allowed for the pooled sale of national television rights by sports leagues. The NFL then entered a 2-year contract with CBS that paid $4.65 million per annum, or $387,500 per team.

The leagues vary in the degree of revenue sharing that they engage in. Further, it is safe to say that there is a fair amount of dispute within each league as to the appropriate level of revenue sharing. The central issues in revenue sharing tend to be the composition of the revenue pool that is shared; that is, which revenues are considered central (paid directly to league) as opposed to local (paid directly to clubs); the local revenue streams that are shared (if any); the amount of sharing (if any) of these local revenues; and the allocation rules used to distribute the shared revenues. This last issue has several alternatives: providing a larger allocation to the teams that have lower local-revenue-generating capabilities; giving an equal allocation to all teams in the league; and making a larger allocation to teams with the highest revenues or the most wins. The latter alternative approaches raw capitalism and is used by the English Premier League, which allocates its national television revenues via a formula that gives the better-performing teams on the field the highest allocations, which increases the absolute revenue differences between clubs. This is a good example of the balance of seeking to equalize revenues while encouraging competition.

Revenue sharing gives rise to moral hazard opportunities. Revenue sharing should reduce opportunistic behavior among profit-maximizing teams by making clubs dependent on each other. However, franchises are not entirely intradependent (even in the NFL), and differing owner motivations means that some are profit maximizing, whereas others are more interested in winning, prestige, ego, and so on. This diversity of owner interests mitigates the effectiveness of revenue sharing in curbing opportunistic behavior by league owners. This opportunistic owner behavior occurs in the form of both “sharking” and “shirking.”6 Sharking is seen in the independent owner action that is initiated to increase the wealth of the individual club at the expense of the overall league welfare. A prime example of this behavior is the undermining of league-wide marketing contracts by teams negotiating their own lucrative marketing agreements, putting compliant teams at a competitive disadvantage. Shirking occurs because revenue sharing creates incentives for a lack of effort among teams, who can free ride the efforts of other teams. Some owners may field uncompetitive teams and undermonetize those club revenues that are shared with other teams. It is difficult to successfully address either form of this opportunistic owner behavior. Getting offending teams to voluntarily accept the league’s governance mechanisms is unlikely, litigation is suboptimal, and increasing the amount of revenue sharing only creates additional shirking opportunities.7 Leagues have taken divergent paths in attempting to do so.

The NFL has the most aggressive revenue sharing system, a product of historical necessity and the aforementioned foresight and leadership of longtime commissioner Pete Rozelle. The NHL has the least amount of revenue sharing and, at present, the largest number of struggling franchises of any of the leagues. Over the years, various proposals to increase the level of revenue sharing in the NHL have been met derisively by the owners, with the typical response beginning with an owner standing up and saying, “Comrades!” This is in reference to the highly socialistic nature of revenue sharing. Perhaps this underscores the notion that sports leagues are simply different than other types of businesses. Revenue sharing in the NBA and MLB falls between these two extremes, although it is hardly any less controversial. The owners in the NBA and NFL determine the league revenue sharing policy unilaterally, whereas MLB and NHL owners must collectively bargain with the players’ union over the terms of their revenue sharing. This is another peculiarity of these sports leagues—the employees have a say in how their employers divide up their revenues. This is because revenue sharing impacts player salaries. All leagues equally divide national media, sponsorship, and licensing revenues among the teams. See Table 1 for MLB team financial data and Table 2 for NFL team financial data.

Sharing of gate receipts varies by league. The percentages allocated among the home and visiting teams and league offices have fluctuated over time as well. In the NFL, 66% of gate receipts are retained by the home team and 34% is pooled and shared among the visiting teams. The NBA and NHL are far more capitalistic in their policies, with NBA home teams retaining 94% of the gate receipts (the other 6% is given to the league office) and NHL home teams keeping all of the gate receipts. MLB adopted a radically different revenue sharing system for its local revenues in its 2002 collective bargaining agreement and continued it in its extension covering the 2007–2011 seasons. This is particularly noteworthy given that more than 75% of MLB revenues are local in nature. MLB teams pool 31% of their local revenues after deducting for their stadium-related expenses, including debt service and rent. These net local revenues are then redistributed equally among all 30 teams. This accounts for roughly 65% of the revenue sharing funds. The remaining 35% of the revenue sharing funds is generated by creating a baseline revenue figure for each team that is based on the average of a team’s net local revenues in the prior seasons and its projected net local revenues in the future seasons. This is used to create a fixed revenue component for each team that cannot increase or decrease unless a team moves into a new stadium. The team then contributes revenue to the pool based on this figure. This system incentivizes teams to increase their local revenues. Overall, MLB has redistributed between $325 and $450 million each season as a result of its revamped revenue sharing plan.

According to former MLBPA Executive Director Don Fehr, “Revenue sharing in MLB is designed to solve competitive imbalance that could result if it did not occur due to revenue imbalances amongst the clubs.”8 MLB owners and executives believe that the plan has increased the league’s competitive balance. After the 2006 Detroit Tigers made the playoffs for the first time since 1987, MLB Commissioner Bud Selig remarked, “I believe that the Tigers are the perfect manifestation of our improved economic climate. I have no doubt that this would not have been attainable a decade ago without our system of revenue sharing.”9

In MLB, revenue sharing is designed to affect salaries and wages by transferring revenues from wealthy teams that could otherwise be spent on player salaries to poorer teams so as to allow them to increase their spending on player salaries. However, no mechanism is in place to ensure that the latter occurs. Thus, it is believed that several teams use their revenue sharing receipts to engage in profit-taking rather than to improve the club on the field. It also creates perverse incentives, because some clubs will not engage in risk-taking and entrepreneurial behaviors.

Revenue sharing of local revenues besides gate receipts is practiced differently in the NBA, NFL, and NHL than it is in MLB. Local revenue streams such as luxury box premiums, local media contracts, local advertising and sponsorship/signage revenues, and naming rights are generally not shared in these leagues. The home team keeps 100% of these revenue streams. This policy is currently being reviewed by both the NFL and NBA.

A larger amount of revenue sharing was adopted in the NHL as part of the collective bargaining agreement that ended the 2004–2005 lockout. The NHL needed to create a pool of revenue from the largest-grossing clubs and some playoff revenues in order to afford some smaller-revenue teams the ability to spend within the payroll range. The philosophy underlying the NHL’s revenue sharing plan is best explained by Deputy Commissioner Bill Daly, who stated, “Our view on revenue sharing has always been that you only need revenue sharing to allow all clubs to afford representative and competitive payrolls, and that’s what this revenue sharing does…. The idea is to subsidize clubs on a revenue basis to get them to the point where they can afford to be a quarter of the way up the payroll range. That would be a minimum commitment on revenue sharing.”10 A club in the bottom half in revenue can spend any amount on payroll and still be eligible for partial revenue sharing, but any club spending over the midpoint is not eligible for the entire amount of revenue sharing available to them.

The revenue sharing plan is funded by league-wide revenue, playoff gate receipts, escrow funds, and the top-grossing clubs. This creates an interesting method of maintaining competitive and economic balance. The revenue sharing also is designed to make sure all clubs maximize local revenue. Mindful of the moral hazard opportunities discussed earlier (read: shirking), Deputy Commissioner Daly remarked, “You don’t want a revenue sharing program that doesn’t incentivize performance.”11 A team must meet a number of qualifiers in order to receive revenue sharing funds. Clubs such as Chicago, Anaheim, and the New York Islanders that are located in markets with 2.5 million or more television households are ineligible to receive revenue sharing funds, even if they fall in the lower-revenue bracket. Since the completion of the third year of the collective bargaining agreement in 2007–2008, clubs also have to grow revenues faster than the league average and have attendance of 75% of capacity to receive their full revenue sharing allotment. As of the 2008–2009 season, they have to be up to 80% of capacity. Teams not meeting revenue sharing marks receive 25% less the first time that they fail to do so, 40% the second time it occurs, and 50% the third. This qualifier led to the Columbus Blue Jackets being penalized $2.25 million for having flat revenue growth versus the league’s 7% growth in 2007–2008. The recipients of the revenue sharing funds tend to be located in the nontraditional hockey markets in the United States. Illustrative of this, the Nashville Predators received a league-high $12 million in revenue sharing in 2008, with contributions from (among others) teams located in hockey-mad Canadian markets: Toronto ($12.0 million), Montreal ($11.5 million), Vancouver ($10.0 million), Calgary ($6.0 million), Ottawa ($1.0 million), and Edmonton ($0.8 million).

Revenue sharing in the NBA is guided by a somewhat different principle. Here, the philosophical question underlying revenue sharing is: “Are there well-managed teams that cannot make a profit due to market factors?” If so, then revenue sharing money should be distributed to them; the revenue sharing pool is funded by part of the escrow and luxury tax payments and in part by teams based on the amount of local revenue generated. In other words, the focus is on profitability rather than revenues and on the limitations faced by some markets in which NBA teams are located. The NBA utilizes a multivariate regression model that determines each team’s optimal team business performance levels. Teams that are underperforming their market’s potential cannot receive funds. It should be noted that the revenue sharing system is not based on market size; rather, it is based on market performance. The NBA redistributes $49 million to teams (no more than $6 million to any team in 2008–2009 and up to $6.6 million in 2010–2011) that are performing above market potential but are still deemed to be disadvantaged (i.e., losing money). This is an increase from previous seasons, as it distributed $14.8 million in 2005–2006 and $30 million in 2007–2008.

Revenue sharing in the NFL has been particularly challenging for the owners. Given that there is no proven correlation between high revenue teams and winning percentage or between high payroll teams and winning percentage, it is fair to ask whether the revenue sharing system in the NFL is suboptimal. The answer depends on who one is talking to—an owner from previous generations or the new generation, or an owner from a smaller-revenue club or a larger-revenue club. When asked if it was problematic, Dan Rooney, the legendary owner of the Pittsburgh Steelers, replied, “We’re not there yet. Any team can win and does win. But we might reach a point somewhere down the line where that’s not the case anymore.”12 Although the NFL considered a number of different options to varying degrees in the prelude to the 2006 collective bargaining negotiations, including sharing all team revenues equally, forcing teams to cover the full labor cost impact of their own local deals, and expanding the local revenue shared to encompass more revenue streams beyond gate receipts, it ultimately chose what many observers contend is a temporary solution—increasing the supplemental revenue sharing pool in March 2007. The owners replaced the previous supplemental pool of $30 to $40 million per year with a system that requires the 15 highest revenue generating teams to create a pool of $430 million from the 2006–2009 seasons to subsidize the 15 lowest revenue generating clubs. The agreement redistributed $100 million in 2006 and $110 million per year for 2007–2009. The owners also established qualifiers that a team must meet in order to receive these supplemental funds: actual player costs higher than 65% of team revenues, gate receipts of at least 90% of the league average (or it faces a deduction off of their share), and ineligibility after a move into a new or renovated stadium costing more than $150 million and for any new owners. This temporary agreement is certainly suboptimal and is largely a product of the league’s politics. Any revenue sharing plan must be approved by three-quarters of the league owners. In other words, a bloc of nine owners can reject any plan that they deem unsuitable. With significant differences between league owners based on the longevity of their ownership and the markets in which their teams are located, it is not difficult for a voting bloc of nine to emerge and unite against any one revenue sharing plan.

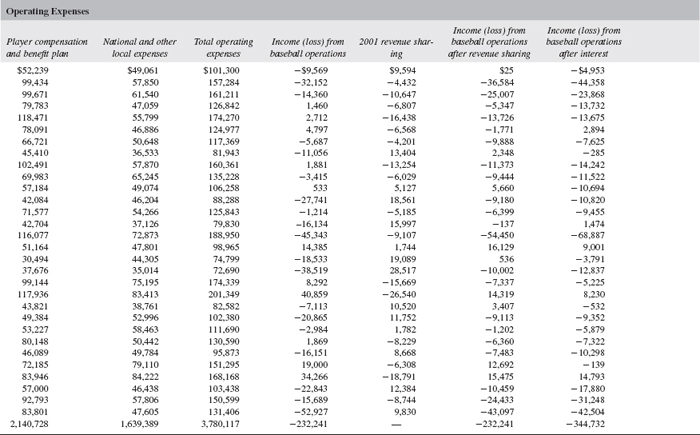

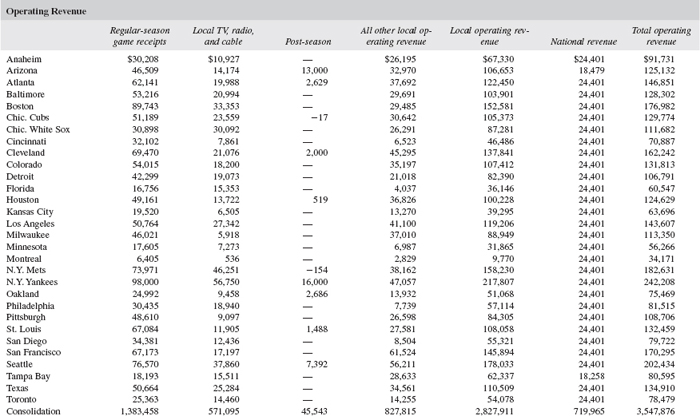

Table 1 MLB 2001 Team-by-Team Revenues and Expenses Forecast (in Thousands)

Source: MLB Updated Supplement to The Report of the Independent Members of the Commissioner’s Blue Ribbon Panel.

Note: Player compensation includes 40-man roster costs and termination pay.

The consolidated loss, when $174,234,000 of nonoperational charges such as amortization of debt are added in, comes to $518,966

Table 2 2009 NFL Operating Income by Team

| Bank/NFL Team | Operating Income (in Millions) |

1. Washington Redskins | 90.3 |

2. New England Patriots | 70.9 |

3. Tampa Bay Buccaneers | 68.9 |

4. Indianapolis Colts | 55.9 |

5. Kansas City Chiefs | 52.4 |

6. Philadelphia Eagles | 48.8 |

7. Baltimore Ravens | 44.3 |

8. Chicago Bears | 41.6 |

9. San Diego Chargers | 41.6 |

10. Houston Texans | 41.5 |

11. Denver Broncos | 39.9 |

12. Buffalo Bills | 39.5 |

13. Cincinnati Bengals | 34.9 |

14. New Orleans Saints | 30.7 |

15. Atlanta Falcons | 28.2 |

16. Jacksonville Jaguars | 26.9 |

17. Miami Dolphins | 26.6 |

18. New York Giants | 26.1 |

19. Tennessee Titans | 24.4 |

20. New York Jets | 24.3 |

21. Arizona Cardinals | 23.9 |

22. Carolina Panthers | 22.9 |

23. St. Louis Rams | 22.3 |

24. San Francisco 49ers | 20.8 |

25. Cleveland Browns | 20.2 |

26. Green Bay Packers | 20.1 |

27. Detroit Lions | 18.5 |

28. Pittsburgh Steelers | 17.8 |

29. Dallas Cowboys | 9.2 |

30. Minnesota Vikings | 8.2 |

31. Seattle Seahawks | –2.4 |

32. Oakland Raiders | –5.7 |

Source: Forbes 2009 NFL Team Valuations.

The issue of competitive balance is similarly vexing to sports leagues.13 Perhaps the best way to think about competitive balance is in its alternative—competitive imbalance. Competitive imbalance can take several different forms, all of which are arguably bad for the league as a collective. The first is if one team dominates the top position in a league over an extended period of time (i.e., dynasties).14 This is bad for the league, because although casual fans may be drawn to the league because of the excellence of the one team, this interest will wane over time because there is little uncertainty of outcome. In addition, fans of the other teams in the league may unite for a period of time to rally against the dynasty, but their interest will wane if their team does not have a realistic chance of winning a championship over a prolonged period of time. A predictable league ultimately becomes of little interest to its followers.

Closely related to this is the second form of competitive imbalance: domination of the top of a league by the same teams over an extended period.15 For example, Celtic or Rangers have won the Scottish Premier League title every year since 1986. Again, there is little uncertainty of outcome, and fans of other teams will ultimately lose interest.

A final form of competitive imbalance is the domination of the bottom of a league by the same teams over an extended period.16 This is bad for a league, because fans of those teams will lose interest in the team and sport, and bringing them back into the fold will require a substantial on-field improvement; that is, contending for a championship. Habitually losing teams also impose costs on the rest of the teams in the league in that their contests against the weaker teams are less attractive and thus typically prevent them from maximizing their revenues in these games.

Leagues use a number of mechanisms to promote competitive balance, including a reverse-order draft in which the worst teams are given an increased opportunity to select the best incoming talent in the league’s entry draft; salary caps and floors, which are designed to compress the range of team spending on playing talent such that all teams are spending relatively close to one another on their athletes; luxury taxes, which penalize teams that spend beyond a proscribed threshold on player salaries in an effort to rein in teams inclined to spend excessively; relegation and promotion, which incentivize teams to win championships so that they may be promoted to a higher level of competition and reap the financial rewards and disincentivize losing contests to prevent the financial harms associated with demotion to a lower level of competition; and revenue sharing, which theoretically provides teams with an increased ability to spend more on player salaries and thus remain more competitive than they would be in the absence of the receipt of these revenues.17

In the first selection, Richard Sheehan examines the revenue sharing practices that have been adopted by professional sports leagues, as well as the economic principles upon which these profit-maximizing endeavors are based. The author proposes a two-part tax on a franchise’s costs and its win–loss record to enhance the effectiveness of these revenue sharing models.

After Sheehan’s passage, the competitive balance issues facing sports leagues are addressed by economists Allen Sanderson and John Siegfried. In their article, “Thinking About Competitive Balance,” they consider various aspects of this often thorny topic. Next, the broad revenue sharing model adopted by the NFL is considered by Clay Moorhead. The development of the NFL’s revenue sharing system is instructive for current sports business leaders because, as previously noted, the league’s revenue sharing plan is considered a significant part of why the NFL is currently considered to be the most successful of the professional sports leagues. Despite this success, problems remain in the system, including threats posed by opportunistic owner behavior. In recent years, there have been increasing complaints by owners in some markets complaining that the revenue sharing model is not as successful as it used to be and should be revamped. This is often raised in the context of collective bargaining and the need for greater revenues to be retained and shared by the owners rather than passed on to the players.

Finally, Stefan Kesenne investigates the intersection of revenue sharing and competitive balance in his aptly titled article, “Competitive Balance in Team Sports and the Impact of Revenue Sharing.”

Notes

1. Michael MacCambridge (quoting Branch Rickey), “A Light Bulb Came On,” America’s Game, Anchor.

2. Michael MacCambridge (quoting Walter O’Malley), “A Light Bulb Came On,” America’s Game, Anchor.

3. Michael MacCambridge (quoting Bill Veeck), “A Light Bulb Came On,” America’s Game, Anchor.

4. Id.

5. Id.

6. Daniel S. Mason, Revenue Sharing and Agency Problems in Professional Team Sport: The Case of the National Football League. Journal of Sport Management, Volume 11, Issue 3 (July 1997).

7. Id.

8. Don Fehr, Remarks at the Executive Directors’ Panel at the 2005 Annual Conference of the Sports Lawyers Association, May 21, 2005.

9. Eric Fisher (quoting Bud Selig), “A Difficult March into a Golden Era,” Sports Business Journal, October 4, 2006.

10. Andy Bernstein, Inside the Complex NHL Deal, Sports Business Journal, August 1, 2005, at p. 01, http://www.sportsbusinessjournal.com/article/46287.

11. Id.

12. Mark Maske and Thomas Heath (quoting Dan Rooney), “NFL’s Economic Model Shows Signs of Strain,” The Washington Post, January 8, 2005.

13. Id.

14. George Foster, Stephen A. Greyser & Bill Walsh, The Business of Sports: Cases and Text on Strategy and Management. South-Western College Pub 29 (2005).

15. Id.

16. Id.

17. Id. at 30–32.

INTRADEPENDENCE: REVENUE SHARING AMONG CLUBS

KEEPING SCORE: THE ECONOMICS OF BIG-TIME SPORTS

Richard G. Sheehan

First, all four leagues on average have been and remain very profitable. The average return to major league professional franchises has been greater than the average return to stocks. Second, profits are not evenly distributed. In each league, some franchises earn substantial profits while other franchises barely break even or lose money…. Third, owners have different motives for buying and owning a professional sports franchise. Some are in it primarily for the money while others are in it primarily for wins or ego or civic pride. And fourth, not all major league franchises are competently managed. Some franchises … have not been well run, assuming that the objective is to make money or to win games.

The conclusions that each league makes a substantial profit but that the profit is unevenly distributed suggests that some revenue sharing may be appropriate. When a league has an average profit rate over 15 percent but some teams are losing money, there might be a problem in the distribution of league profits, and some mechanism to share league revenues might be appropriate. In fact, each league already has some revenue sharing. For example, all leagues equally divide national television revenues, regardless of a team’s number of TV appearances, record, or drawing power. Another example is a league’s centralization of the licensing process…

This chapter considers three questions on revenue sharing. First, how much revenue has been shared in each league. Second, why should any revenue be shared? That is, is there an economic justification underlying revenue sharing and how can the problems associated with revenue sharing be overcome? And third, is there a specific proposal for revenue sharing that begins to address two of the most important problems facing professional sports: (1) How can revenues be split between rich franchises and poor without destroying the incentives for the rich to keep generating prolific revenues? (2) And how can anyone reconcile the split among owners where some focus primarily on the bottom line and others focus primarily on winning? …

CURRENT-REVENUE SHARING ARRANGEMENTS

What revenues currently are shared? For all leagues, the ground rules are strikingly alike. National media money is shared while local media money generally is not; licensing money accrues to the league and is shared while any local advertising money is not; sharing of gate receipts varies by league while luxury box income generally is not shared. NFL gate receipts are split 60-40, with the home team receiving a greater amount justified on the basis of the costs of putting on the game. At the other extreme, the NHL home team retains the entire gate. In the NBA the home team keeps 94 percent of the gate while the league receives the other 6 percent.

….

In terms of total revenue generated per franchise, the NFL leads all leagues … Major League Baseball (MLB) is second in revenues…. Gate receipts are the largest component of MLB receipts … followed by other revenues (primarily stadium revenues) … and local media…. The NBA’s two largest income sources are gate revenues … and national media…. The NHL relies most heavily on gate revenues … and other revenues (again, primarily stadium revenues) ….

Comparing the leagues, the advantage of the NFL clearly lies in its television contracts…. Based on national media revenues, MLB is no longer the national pastime and is not even number two. The NBA now has that honor…. Where baseball is still the most popular is in terms of attendance and gate receipts, where it easily outdistances all other leagues. Perhaps the surprises here are that the NHL has the second highest gate receipts, surpassing the NBA, and that the NFL with so few games still has close to the same gate receipts as other leagues.

In the NFL, the two largest revenue categories, TV money and gate receipts, are split relatively equally. Thus, the NFL has the greatest degree of revenue sharing…. In contrast, the NHL has the smallest national media revenues, the smallest licensing revenues, and no split of gate revenues. Thus NHL revenue sharing was the lowest … MLB and the NBA fall between these two extremes…. In the NBA, the percentage sharing of the gate is relatively small, but national media money is shared and is relatively more important for NBA franchises than for MLB franchises.

Another perspective on the distribution of revenues is given by the range of revenues in a league. How do the revenues of the richest and poorest franchises compare? … The results indicate a wide range for all four leagues, smallest in the NFL…. Given the importance of TV money to the NFL, this result should not be a surprise. Regardless of how a franchise is run, TV money gives all NFL teams a solid revenue base.

….

What may be most noteworthy about the maximum and minimum revenue numbers is the observation that New York City teams lead in all leagues except the NFL, the league with the most revenue sharing. New York City teams have natural revenue advantages over … Buffalo and Salt Lake City. However … this revenue advantage has not led to more victories and has led to only marginally greater financial success. New York City teams have both higher revenues and higher costs…. Market size may play a minor role, but it is a long way from the whole explanation of profits, wins, or anything else. Whether a team wins and whether it is well run both contribute more to financial success.

THE ECONOMIC LOGIC UNDERLYING REVENUE SHARING

Should there be revenue sharing? Is there any economic justification underlying revenue sharing? For an economist the answer is simple. In MLB, for example, the Yankees and the Brewers take the field to play a game. They create a win, a loss, and entertainment. It is a classic example of a joint product. The fans and the media pay for the entertainment while one of the teams ends up with a win and the other gets a loss. The product obviously is shared, and since the Yankees and Brewers must cooperate to produce it—in terms of agreeing on ground rules—the financial rewards are appropriately shared. But how are the Yankees and Brewers to split the revenues?

Three issues underlie this apparently simple question. First, you have a set of accounting issues: do you split gross revenues or net and how do you define the revenues to be shared? …

Second, there are equity concerns. What is a “fair” split of the revenues between the Yankees and the Brewers? … Efficiency arguments made below weigh heavily against an equal split of local revenues. Before considering efficiency, however, there is an equity argument against equally splitting local revenues. In any league we should expect the first franchises to be located in the most profitable cities. New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles have franchises in all leagues (temporarily except the NFL) and sometimes multiple franchises. Detroit, Boston, Philadelphia, and San Francisco also have franchises in all leagues. When you buy an expansion franchise, you should know that it is unlikely to generate the revenue stream of many “old guard” franchises. Thus, it would be disingenuous in MLB for expansion franchises in Colorado or Florida to argue that they deserve a share of Yankees’ or Dodgers’ revenues when the new owners should have known at the outset that they would be among the marginal franchises in the league….

Third and most importantly, how can you undertake revenue sharing while not destroying economic incentives? How can you undertake revenue sharing and give owners or potential owners a greater incentive to pursue profits, victories, and the long-run economic health of the league? From an economic perspective, the interesting question about revenue sharing is its efficiency implications. The simplest way of viewing revenue sharing is to think of it as a tax. The general rule in economics is that any tax will distort economic incentives. In this case, we can put the distorting effects of taxes to an advantage. Many things could be taxed, for example, total costs, total revenues, player payrolls (the owners’ favorite), or even wins and losses. What is taxed will effect how owners will react to the tax and will impact how owners, players, and fans will fare.

….

There are fixed costs associated with running a franchise. For example, a MLB franchise has a minimum payroll of $2.5 million [Ed. Note: the 2010 minimum was $10.0 million] given the roster size and the minimum salary. Taxing this amount or any fixed cost has no impact on a franchise’s operations and is incompatible with revenue sharing. A tax on anything other than incremental costs or revenues is simply bad economics as far as changing incentives is concerned.

A second example of how not to tax has been proposed by some small-market MLB owners. This tax would split all local media money equally among all franchises…. More problematic is the question of incentives. What would happen the next time the New York Yankees’ media contract is up for renegotiations? How much incentive do the Yankees have to bargain aggressively for a higher fee …? The moral: equally splitting local revenues would likely have devastating long-run impacts on those revenues. Thus this tax also is bad economics.

ECONOMICALLY JUSTIFIED TAXES TO IMPLEMENT REVENUE SHARING

So how can we set a tax that would be good economics? Let me state the requirements for a good tax system, given the problems facing all leagues. (1) Profits are healthy but are unevenly distributed. Implication: some revenue sharing is necessary, and a tax must fall more heavily on profitable franchises. (2) Owners have different goals; some focus more on wins and others on profits. Implication: two types of taxes are necessary, one on those seeking victory and another on those seeking profits. (3) Taxing revenue will make owners reluctant to take steps to “grow” revenues coming into the league. Implication: avoid taxing revenues; where possible, tax costs instead. (4) Taxes should allow markets to operate without introducing additional distortions. Implication: when players’ salaries are determined in a competitive market, there is no need to separately tax this component of costs.

With these suggestions, let us consider a two-part tax, on a franchise’s total costs and on its win–loss record. First, consider the “cost” tax and three fundamental questions. Why tax costs rather than revenues? What costs should be taxed? And how high a tax rate is appropriate?

Revenue sharing could be undertaken either by taxing a franchise’s revenues or its costs. To date, revenue sharing in all leagues has been done by taxing revenues…. Taxing a franchise’s revenues ultimately depresses the league’s revenues and both owners and players suffer in the long run. In contrast, taxing costs strengthens owners’ existing desires to control costs and to increase profitability. Owners will be better off even if players are not.

What costs should be taxed? Any tax would appear appropriately levied with respect to all costs and not just player salaries, assuming owners are serious about getting a handle on costs and are not simply out to break a union…. While the focus is on all costs, the tax itself should be levied only on incremental costs. For example, if the average costs in a league were $50 million, it would make sense to tax a franchise only on its costs in excess of $50 million, or on its incremental or marginal costs. The goal of the tax is to provide an incentive to keep expenditures below some level.

Now the focus on incremental costs requires some additional explanation, and that explanation is related to how high the tax rate should be and what is the need for revenue sharing in the first place. The tax rate cannot be too high or it will have ugly incentive effects. With a high enough tax rate we could have all franchises fielding a whole new team of rookies each year. But we do not need a tax rate all that high to obtain the desired effect of restricting costs. The main point underlying revenue sharing is that a game creates both a win and a loss and the winner receives more revenues than the loser. Thus, the winner imposes an economic cost on the loser. What is that cost? The answer varies by sport and even by team within [a] sport….

There is some question on what costs should be taxed. The argument made earlier emphasized placing the tax on all costs rather than just on players’ salaries. There remains a question of whether this tax should be placed only on costs above some threshold, a so-called “luxury tax” or whether it should be placed on all costs…. For simplicity assume all clubs spend the same amount and are equally com petitive. Then one owner attempted to buy a championship by increasing spending. His additional expenditures make his team more competitive and presumably cost other owners money. Those incremental expenditures should be subject to a tax. There is no reason why only expenditures, say, 30 percent above the average impose costs on other franchises.

…. Two numbers are important. First, how much does it cost to win one more game? … Second, how much revenue does a franchise lose when the team loses one more game? … The appropriate tax rate is simply the ratio of the revenue sacrificed with one additional loss divided by the cost of winning one more game, or how much one owner’s incremental expenditures cost another in lost revenues.

….

Perhaps the most important feature of this type of tax is that it begins to address one of the major problems underlying much economic strife in sports: the problem of differing owner desires. Some owners primarily want profits and some victories. How does this tax address that? Owners that want victories and championships will still choose to spend more…. As they spend more and perhaps win more they also impose costs on other owners that place a higher value on profits. Presumably the money from the tax on costs will be used to reimburse those owners who choose not to increase spending and who end up losing more frequently. Owners that want championships can still attempt to buy them if they wish, but only to the extent that they compensate other owners for the costs of losing.

Now this “cost” tax by itself is not the entire solution. Of course, all owners want both wins and profits, but the relative importance placed on each may differ dramatically. The tax above is on those that want to win and are spending freely to do it. They have to pay a penalty for the costs they are imposing on those that want profits. Those who want to win can still spend as freely as they want, but they must internalize the costs they impose on other owners. But owners who primarily want profits also impose costs on other owners. Why? They have little incentive to field a competitive team unless profits are at stake….

League revenues will be higher in the long run when the games and the races are tight, although any one team might be able to reduce short-term expenditures and lose games but gain profits. What can be done to reduce this incentive? One suggestion: tax less-successful franchises. Give owners who focus only on profits a greater incentive to win. In some cases, franchises have effectively stopped trying to field a competitive team…. Taxing their losses would likely stimulate more interest in winning and may increase league profitability.

The first tax takes the Steinbrenners … and taxes them for their free-spending ways. The second takes the Bill Bidwells (owner of the Arizona Cardinals) and Tom Werners (Chairman of the Boston Red Sox and former owner of the Padres) and says field a competitive team or pay a price. The former says of the win-at-all-cost owners pay attention to those concerned with profits. The second says of the only-profits-count owners that you must also be concerned with the on-the-field competition. Thus both sets of owners must move closer to a common middle ground that explicitly gives weight to both controlling costs and fielding a competitive team. Both types of owners may continue with their original focus, but the economic incentives push them toward a compromise. Furthermore, a compromise between the owners is a prerequisite for an agreement with the players.

….

What is to be done with this revenue? Given that all leagues face a problem not of insufficient profits but of an unequal distribution of profits, it would seem reasonable to take the revenue raised and return it to franchises with revenue below the league average. What mechanism you employ should not seriously weaken poorer franchises’ incentives to generate their own revenues. Consider a mechanism that returns taxes proportionately to all franchises with revenues less than the league average…. These franchises have experienced real financial difficulties. This system of taxes and revenue sharing would help them all. It would not guarantee them profits, however.

….

The nature of these taxes is to subsidize teams that are well run and yet still have difficulty making ends meet…. This tax system, with low tax rates and a carefully selected base, cannot bail out a club … that is awash in red ink. It can do two things, however. It can and does reward those clubs that are “doing things right” or fielding a competitive team at a relatively low cost. It also provides an even greater incentive for owners to be financially prudent and exercise appropriate oversight over fielding competitive teams. In a word, this set of taxes cannot give all owners the same set of incentives. However, it does bridge the current chasm between those in the league primarily as a business and those in it primarily as a hobby.

…

Virtually all NFL franchises have been quite profitable. One can make the argument that the NFL’s success is rooted in their revenue sharing, even as different owners appear to have very different objectives. With the NFL’s current revenue sharing arrangements, there is little reason or justification for additional revenue sharing. There is, however, a strong case against allowing owners like Jerry Jones to cut their own deals with whomever they choose. Ultimately, Jones’ deals with Nike and Pepsi, for example, reduce the value of the league’s deals with Reebok and Coke. When the league’s deals through its marketing arm, NFL Properties, come up for renewal they will be negotiated downward and total league revenue may fall.

….

Jerry Jones quite likely can make more money marketing the Cowboys on his own than he will receive from the Cowboys’ share of NFL Properties income. Jones may well have the panache to run NFL Properties substantially better than it currently is being run. Jones, however, is totally off base when he says that the average franchise is better off doing its own marketing than going through NFL Properties. With 32 franchises each doing its own marketing, the competition for deals with prime sponsors like Nike will likely drive the value of those deals down for most teams. Teams like the Cowboys and 49ers may be better off but most teams will lose, and many smaller-market teams could lose dramatically. Is the average NFL owner better off with a marketing monopoly and shared profits or with 32 marketing competitors? With apologies to Ben Franklin, NFL owners had better hang together or else competitive markets will hang them all separately.

CONCLUSIONS

What is the bottom line on revenue sharing? Revenue sharing can be simply an out-and-out attempt by small-market franchises to expropriate the wealth of richer teams…. If that is the case, for most of us it may be interesting theater but it is not interesting from either a finance or a sports perspective.

Revenue sharing does have a strong economic justification based upon the cooperation required between teams to generate league revenues. Since the game is a joint effort, economic theory can be employed to suggest how revenues can be split to provide positive rather than negative incentives….

The system of taxes and revenue sharing presented here addresses a fundamental problem of sports: that owners are in it both as a business and as a hobby and the weights that different owners place on these two goals sometimes differ dramatically. Taxing both excess costs and excess losses should move owners to roughly the same page in the playbook and should reduce losses at competently managed small-market franchises. This system of taxes also has the potential to reduce tensions between players and owners. Owners would have an incentive to more carefully monitor all costs, including player payroll, because of the cost tax. But owners also would have an incentive to make sure they field a competitive team because of the loss tax.

COMPETITIVE BALANCE

THINKING ABOUT COMPETITIVE BALANCE

Allen R. Sanderson and John J. Siegfried

In an era in which inequalities of wealth and opportunity are constantly at the forefront of public policy discussions in the United States, in the world of professional sports, many high-profile economic events also seem to turn on issues of inequality: between owners and players over the distribution of economic rents; among owners over the distribution of gate receipts, broadcast revenues, and talent; and among mayors, taxpayers, owners, and league officials over figurative level playing fields with regard to the provision of state-of-the-art venues.

….

Simon Rottenberg (1956) long ago noted that “the nature of the industry is such that competitors must be of approximately equal ‘size’ if any are to be successful; this seems to be a unique attribute of professional competitive sports” (p. 242; see also Rottenberg, 2000). Although the absolute quality of play influences demand and absolute investments in training are socially efficient (Lazear & Rosen, 1981), the relative aspects of demand and quality of competition also loom large in sports. In cases when consumer demand depends, to a large extent, on interteam competition and rivalry, the necessary interactions across “firms” (i.e., teams) define the special nature of sports. Contests between poorly matched competitors would eventually cause fan interest to wane and industry revenues to fall. But potential arms races—or rat races—are possible and maybe even inevitable (Akerlof, 1976; see also Whitney, 1993).

In the 1990s and early 21st century, while some social scientists wrung their hands over apparent widening inequality of income in the United States and between developed and third-world nations, sports economists, commentators, fans, and owners (at least among the also-rans) lamented the perceived widening inequality of wealth and championships among teams, especially the large-market, high-revenue, and/or high-payroll teams versus their country-cousin kin in baseball.1 The distribution of playing talent, team revenues and salary expenditures, and competitive balance dominate sports and sports-business conversations whenever a team with the highest payroll (or an owner with the deepest pockets or a decidedly different utility function) wins a championship, whenever a franchise extracts a new publicly funded ballpark from its community on the threat of relocating, or whenever an apparent dynasty emerges…

….

Also in 1999, Baseball Commissioner Allan H. “Bud” Selig convened a panel of well-known individuals to study the impact of revenue disparities on competitive balance. It produced a lengthy report, “The Commissioner’s Blue Ribbon Report on Baseball Economics” (BRR) (Levin, Mitchell, Volcker, & Will, 2000), that noted large and growing revenue disparities, which, in turn, affected balance.5 In addition to more quantitative theoretical and empirical measures of competitive balance (see below), the Blue Ribbon panel also defined competitive balance qualitatively: In the context of baseball, proper competitive balance should be understood to exist when there are no clubs chronically weak because of MLB’s financial structural features. Proper competitive balance will not exist until every well-run club has a regularly recurring hope of reaching postseason play. (Levin et al., 2000, p. 5)

Broadcaster Bob Costas (2000) chimed in with similar laments. MLB conducted a national poll of 1,000 fans in late 2001 that purported to indicate that competitive imbalance was a serious problem in the minds of 75% of respondents; 42% of them indicated they would lose interest in the game were more teams not to have a realistic chance of winning. Summarizing the results, Sandy Alderson, MLB’s executive vice president, said, “We have a competitive-balance problem. This is something the average fan cares about. They don’t care if owners are losing money. They do care if it translates into negative consequences for their teams” (Rogers, 2001, p. 1).

Although certainly not unique to this particular period or sport, the complaint of woeful imbalance has become more common in the last few years with the lack of significant revenue sharing or a firm payroll cap in MLB relative to the National Football League (NFL), identified as the culprit. Increased player freedom, through which an owner could hire the best players and, at least in the short run, buy a championship, is seen as an accomplice. Apart from the obvious owners’ interest in limiting bidding for players and the equally obvious interest among players in that not being allowed to occur, payroll caps, salary caps, luxury taxes, increased revenue sharing, and restructured draft systems are touted as ways to constrain competition and thus improve competitive balance among teams.6 League restrictions on both the geographical relocations of teams and the mobility of players across teams, in addition to having more self-serving purposes, also affect balance….

In the sections below we attempt to lay out what one might mean by competitive balance, review the theoretical and empirical scholarship and popular contributions with regard to its various dimensions, and describe the natural forces and considerations as well as institutional rules and regulations that contribute to observed distributions of playing performances. We also compare, at various junctures, the situation in baseball versus other sports leagues including college athletics and individual sports.

COMPETITIVE BALANCE IN THEORY AND PRACTICE

Every sport and sports league has had to confront the fundamental issue of relative strengths among competitors. There has not been a uniform, one-size-fits-all approach or set of rules to resolve this problem. Inasmuch as uncertainty of outcome is a key component of fan demand, wide disparities in inputs and, thus, in likely outcomes are seen as inimical to the long-term health and financial viability of the individual enterprise. How to handle weak teams or inferior opponents—to prevent lower quality competitors from free-riding on higher quality rivals—can be as much or more of a problem as dealing with perennially strong ones, because there is at least some interest in seeing the very best individual performers and teams.7

Boxing segments fighters into weight classes and employs rankings and ladders to create bouts with equally matched opponents. Auto racing, track competitions, and swimming use qualifying times to ensure competitive fields. Tennis produces seedings based on previous performances in the expectation that the strong will play the strong in later round matches. Claiming races in thoroughbred racing is a mechanism designed to have horses of approximately equal ability entered into the same event. Except for the occasional novelty or promotion, women do not compete against men. Periodic structural changes or modifications in the rules of play, such as elimination of the center-jump and adoption of a shot clock in basketball and altering the height of the mound or changing the effective strike zone in baseball, have been used to tilt the playing field to achieve a certain objective and to prevent some competitors from exploiting particular advantages or decreasing fan interest in the contests. Another example is restrictions on athletes’ use of performance-enhancing substances.

….

For English soccer, Szymanski (2001) has shown that the growing financial disparity between clubs has had no impact on imbalance. How closely payroll and market size correlate with winning—including, of course, the determination of the causal relationship—is arguably one of the most important questions about competitive balance. It is also essential to evaluate the relationship between market size and team payroll, which is often inaccurately assumed to be tight.

….

THE NATURAL DEMAND FOR AND SUPPLY OF BALANCE (AND IMBALANCE)

Apart from the constraints leagues place on competition to ensure balance (factors discussed later), which may have the complementary effect of increasing and/or redistributing revenues, there are also natural forces that influence the distribution of outcomes. One obstacle to reducing inequality in sports leagues could be, paraphrasing Pogo, that we may not only be content with the current imbalance but also actually prefer it to the alternatives. Or, at a minimum, we are conflicted and willing to let natural (and unnatural) forces and inertia, rather than explicit interventions, determine outcomes. In economic and sporting walks of life, we have a preference for a positive correlation between effort and reward. To reward the statistically better individual or team for its prior achievements, we tip some balances in its favor—playing more games at home, higher seeds or a better lane, an extended playoff series rather than a single winner-take-all contest. The more evenly matched two opponents are, the higher the probability that a random element—a poor call by an official, a bad bounce, a key injury, or pure luck—will determine the outcome.12 Thus, the premise that the demand for games is greater, ceteris paribus, the greater the degree of uncertainty conflicts with our sense of justice that the better team win. Luck is the way we account for the success of people and teams we do not like, but it is not a factor that we generally want to determine our income distributions in society or our champions in sporting contests.

On the other hand, we have strong identifications with and sympathies for the true underdog. We want David to knock off Goliath, at least on occasion (unless, of course, Goliath plays for us—Chicago was quite content with the Bulls’s domination in the 1990s, and Yankee fans have few quibbles with the alleged imbalance in baseball). Nowhere is this better exemplified than in popular sports movies that feed off imbalance. Films such as Rocky, Hoosiers, The Mighty Ducks, and Major League cater to these instincts. (And, after all, the play was called Damn Yankees, not Damn Cubs.) As much as one may loathe a bully, selling tickets to an event in which he has some chance of being upset is marketable. Dynasties and storied franchises, such as the Yankees, Celtics, Packers, and Red Wings, are not without their advantages in terms of fan interest.

The world is replete with examples of healthy inequality more extreme than the current levels in baseball. State lotteries are popular despite daunting odds. Although just 25 of the nation’s 400 graduate schools grant a third of all new Ph.D.s each year, the industry maintains diversity and vitality while competing implicitly head to head. Other comparable concentrations and inequalities abound: Live theater, world-class symphonies, and first-rate art museums are not evenly distributed across the landscape.

In sports, virtually all teams win at least a fourth of their games and few win more than two thirds of the time. Victories—and losses—are not inevitable. In leagues with 30 teams, the probability of winning the ultimate prize—a World Series or Super Bowl—with equal distributions of talent in any given year is .033; thus, a team or city could expect to garner a championship about once a generation. The difference between that periodicity and a dynasty can be as little as a factor of three in that, in the latter instance, a team may win a championship once a decade instead of once per generation.

Sports fans’ memories are selective and the rate at which they fade appears to be small. That a team last won a Super Bowl or World Series more than a decade ago may seem like yesterday. (Many Chicago fans think of the Bears as a championship team, even though their only Super Bowl win occurred in 1986.) Stadiums and arenas are replete with banners from past conquests—in most cases many years removed. Fans don sweatshirts and caps that evoke past memories as much as current realities. That, coupled with our basic hope-springs-eternal (or wait-until-next-year) spirit, fueled with optimism about the most recent draft choice or free agent acquisition, buoys the soul—and ticket sales. Scully’s (1995) empirical validation of serial correlation in sports and his admonition that fans should be patient reinforces our natural instincts and outlooks. In a society that confronts substantial inequality in its daily experiences, the current level of imbalance in baseball may not be intolerable.

In addition to these many factors contributing to the observed inequality of outcomes, whatever the metric, there are several other possible explanations for competitive team imbalance. The following examples are but a few such considerations.

Differences in Population and Preferences

The demand for beachwear in Ft. Lauderdale dramatically exceeds the demand for swimsuits in Buffalo and also in St. Augustine, yet no one seems to worry about bikini imbalances. Indeed, we would probably be puzzled if such sales in Ft. Lauderdale did not exceed combined receipts in Buffalo and St. Augustine by a large margin. Although the populations of Buffalo and Ft. Lauderdale are similar, the per capita demand for bathing suits is greater in Florida than in upstate New York presumably because of greater utility in use. And, although St. Augustine and Ft. Lauderdale share the same climate and accessibility to beaches, the population of Ft. Lauderdale is many times larger than that of St. Augustine. Geographic differences and preferences exist with regard to types of foodstuffs consumed, automobiles driven, and television programs watched.

So, too, is this true for winning sporting contests. Residents in some locations may be willing to pay more to have a more successful local team (e.g., per capita willingness and ability to support a winning ice hockey team is undoubtedly greater in Ontario than in Florida), especially if there are few other recreational, entertainment, and/or cultural amenities close at hand. Population disparities between areas hosting teams can create differences in aggregate willingness and ability to pay even when individual customers in the various host cities have identical tastes.

These differences could be equalized if teams in sports leagues were free to move to areas where the marginal revenue per win is higher than in their initial location. The resulting competition between teams in the same league within a metropolitan area would dilute the incremental revenues earned by the original incumbent and reduce financial disparities among the teams. The collection of Australian rules football teams in Melbourne, the concentration of baseball teams in Tokyo, and the density of premier-league soccer teams in London illustrates the possibility.

Team movements that would help to equalize marginal revenues do not occur, however, because each of the professional men’s team sports leagues in North America exercises a form of collective control over member team movements. Incumbents in the larger cities or those cities where fans are willing to pay more for winning are loath to share their revenues with immigrants from smaller communities or from locations where success on the playing field is less important to the residents. They are protected from incursions either by league constitutional provisions protecting their home territory or by their ability to form coalitions sufficient to prevent other teams from moving into their host community. In short, the competitive imbalance that emanates from the monopoly control of home territories by incumbents arises from the conduct of the leagues’ member teams themselves, because they are unwilling or unable to introduce competition into areas where favored incumbent teams earn considerable economic rents….

These disparities, and even the large market versus small market distinction, would disappear if expansion occurred within an existing cartel league, a rival league formed, and/or some judicial action broke up the cartel (as the resulting smaller leagues, in search of new markets, spawned new franchises).14 New York City is considered a large market and Kansas City a small one, in part, because the ratio of teams to population is so dissimilar. Migration of existing franchises and/or the creation of new ones located in larger metropolitan areas would equalize these ratios in sports leagues much as retail establishments and other social amenities equalize in more traditional, competitive markets, such as fast-food outlets and swimsuit retailing.

Willingness to Act on Differences in Fan Tastes

In addition to different preferences for winning, fans who live in different areas may differ in their willingness to act on those preferences (Porter, 1992). The more fickle are fans, the more their willingness to buy tickets depends on the local team’s on-field success, the greater is the marginal revenue from the local team’s winning additional contests, and the greater is the incentive for a team to expend resources to secure more highly skilled players. A profit-maximizing league could exploit fickleness by strengthening teams located where fans are less loyal and, in turn, weakening teams where fans will turn out regardless of the success of the local franchise. This would not bode well for the Cubs and Steelers. If a league did this, however, the distribution of playing talent could be inefficient because it is configured in response to fans’ willingness to act on their preferences rather than on the basis of the preferences themselves.

Moreover, in addition to caring about the on-field success of the home team, fans often have preferences regarding dominance that are independent of which team dominates. That is, the competitive balance distribution itself is a public good. Everyone must live with the same overall distribution, and individuals may have strong preferences about the shape of that distribution. Some may prefer imbalance—even sufficient to create dynasties whether they love them or love to hate them. Others may prefer a league in which almost all teams win about half of their contests.

Although fans may have views on what the general distribution of competitive balance should look like, these views may fluctuate over time. As the real income levels of sports consumers have risen over the second half of the 20th century (Siegfried & Peterson, 2000) and the typical fan has moved further up an increasingly dispersive income distribution, fan preferences toward the overall distribution of competitive balance could migrate toward more imbalance in game outcomes, as well.

Differences in Player Tastes

Differences in team playing skills can arise even if there are no differences in the population base of team territories, in fan fickleness, or in fan preferences toward home-team winning or dynasties, because players also have preferences. Players may have a preference for living in certain areas (e.g., Florida or Southern California) and may be willing to sacrifice part of their salary to do so. Or they may see more lucrative endorsement opportunities in areas with relatively stronger media markets….

Network economies can also affect the distribution of playing talent. Players may accept a lower salary to be on a team with greater odds of winning a championship thereby further enhancing the talent of the contender….

Consider, in the extreme, how players might distribute themselves across teams if their salaries were zero. Would they join teams to balance playing talent? College football and basketball may provide some guidance as to what might happen because players’ compensation is relatively constant across universities. There, the attractive new prospects gravitate toward perennial winners to enjoy greater prospects for on-field success, to play with more talented teammates, and to gain more media exposure.

The Trade-Off Between Winning and Uncertainty

Competitive balance is thought to affect attendance of fans through its influence on winning and fans’ response to winning. It is well established that home attendance rises when a team wins more games or matches and declines when it loses.16 Winning teams also attract more fans when they play on the road. The Yankees attract a crowd when they visit other American League cities whether it is because fans love to hate a winner, wish to see marquee players, or the Yankees have a following in other locations. As the mobility of our population has increased in the post-World War II years, fans of particular teams more frequently reside outside their home territory. Similarly, superstation broadcasts have created national Braves and Cubs fans. Although that phenomenon does not affect home attendance much, it can affect away attendance and television ratings. The extent to which owners of stronger teams take these factors into account depends on league rules for sharing gate and television revenues. The Detroit Red Wings draw huge crowds on the road because they are an elite team of established (read: older), talented players and because former residents of Detroit maintain their affinity for the team and attend games that the Red Wings play on the road. This generates incremental revenue for other National Hockey League (NHL) teams but does not affect incentives facing the Red Wings management, because, in the NHL, visiting teams do not share in gate receipts and there is little national television revenue.

Competitive balance may also affect attendance negatively at games of teams that are relatively weak, because fans view them as out of the running for a championship (as opposed to any individual contest on any given day). If this occurs when the revenue sharing rules are confined largely to home and visiting teams, the owners of the higher revenue teams may ignore the external impact of imbalance on the league’s overall revenues until it reaches the point where the integrity of the overall competition is called into question and fans abandon the sport altogether. The addition of wild-card teams and smaller divisions or conferences, which both increase the number of teams eligible for the playoffs, are innovations designed to retain fans across more cities longer in the regular season by increasing the uncertainty of ultimate outcomes.

Character of the Events Themselves

In the 1980s and 1990s, responding to fan demand driven in part by higher incomes, professional sports franchises repositioned their product by increasing the emphasis on complementary noncontest services and amenities to blur further the distinction between sports and entertainment. (The short-lived Xtreme Football League [XFL] may have overshot that moving target.) Although the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders predate the 1980s, they are a vivid representation of the movement. New stadiums that include upscale restaurants, batting cages and other amusements for children, museums, Jumbotron scoreboards with instant replay and promotions, fireworks, and even a swimming pool (in Phoenix) reduce the relative importance of the game in the overall recreational package. Intermission entertainment at basketball, ice hockey, and football games is now standard fare including contests for fans, minishows by well-known musical artists, trampoline groups, and scoreboard video clips…. Luxury boxes and exclusive access areas increase the value of being seen at the game relative to seeing the game.

As the relative importance of the game itself diminishes in the entertainment package, competitive balance becomes a less important determinant of demand. So long as the tendency to broaden the entertainment experience is similar across locations of differing revenue potential, however, this phenomenon, like revenue sharing, should not have more than a modest effect on competitive balance.

Complementary Economic Theory

Traditional economic arguments for what prevents one owner from amassing an all-star line-up in an effort to win every contest and the championship turn on notions of self-interest and the inevitable diminishing marginal returns to, and the increasing marginal cost of, victories. Hence, some natural mechanisms constrain the extent of imbalance in most leagues. That assumes, however, that there are both effective ways to blunt possible negative externalities and that owners, deep down, are profit maximizers.

Common practices within sports leagues to ensure some semblance of a level playing field with regard to the distribution of talent across teams—reverse-order draft systems, various attempts to constrain players’ salaries, revenue sharing—are also at odds with how economic theory generally views peer effects and the optimal sorting of workers. Where spillovers are significant, high-ability workers are more valuable to other high-quality workers, and workers should be more homogeneously sorted.17 The assignment problem involves how to sort heterogeneous units into groups so that output is maximized (see Becker, 1973; Guryan, 2001; Koopmans & Beckman, 1957; Kremer, 1993; Saint-Paul, 2001). Whether in general production processes, law firms, or marriages, higher ability workers, colleagues, or spouses are more productive when grouped with other high-ability people. Because similar quality workers are more productive when sorted into the same firm, a firm with higher quality workers may not be willing to employ lower quality workers even if those workers would work for less pay.

The general application of this sorting principle in sports implies, for example, that an all-star shortstop’s productivity is higher if he is paired with an all-star second baseman. Moreover, on-the-field traits carry over into the clubhouse and social settings where discipline, motivation, attitude, and joint monitoring can be important, as well. If this proposition is true, when practiced in sports, it should lead to inequality in the distribution of talent—some teams should have good players, other teams poor ones, and competitive imbalance should emerge. (Within baseball organizations, the farm system may serve as a sorting mechanism, and across-team trades and free-agent signings may represent, in part, attempts to capture potential peer-effect gains.) In some sense, then, sports leagues may be fighting an uphill battle in trying to stem the tide of nature and market forces pushing toward imbalance.

INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS AND COMPETITIVE BALANCE

Many institutions or off-the-field rules of the game are negotiated every time a collective bargaining agreement (CBA) is renewed. These changes may affect the degree of competitive balance in any professional sports league.

Payroll Caps and Luxury Taxes

Payroll caps and so-called luxury taxes on payrolls create an incentive for owners of teams in higher revenue locations to hire less talent than they would in the absence of these constraints. In the extreme, a binding ceiling on total payroll limits the amount of talent a high-revenue team can accumulate. As a by-product, a firm payroll cap also increases the profits of high-revenue teams. Its impact on competitive balance depends on the extent to which the cap is below the free-market payroll level of the highest payroll team that also dominates on the field (read: Yankees).

One danger of payroll caps is that they may be porous (e.g., the NBA cap that includes a well-known loophole—the Larry Bird exemption—designed to preserve team unity, or the NFL, in which, for 2002, accounting conventions permitted virtually every team in the league to be over the cap), and they create a temptation for violating the rules (e.g., the Minnesota Timberwolves paid a large fine for paying Joe Smith off the books in excess of the cap). A system in which cheaters are more successful than those who play by the rules may be even less inviting than one in which teams fortunate enough to own rights to high-revenue areas are more successful. Moreover, payroll (and salary) caps do not extend to complementary inputs, so successful coaches … can command a sizable sum for managing a team on which the total payroll, and even individual salaries, may be frozen.

A less drastic version of the payroll cap is what has come to be known in professional sports as a luxury tax on payrolls…. The rationale is that fielding a highly paid team is a luxury for one owner that imposes negative externalities on other franchises. This makes sense if the tax becomes effective at the point where incremental talent on the high-revenue team creates a league-wide net negative impact that might be ignored by the owner of the high-revenue team, because, under league revenue sharing rules, he or she bears little of the cost of an over accumulation of talent. If the tax rate accurately reflects this internal externality, it creates an incentive for the high-revenue team owner to balance his or her gain against the cost to third parties. The trick, of course, is to impose the tax rate at the proper payroll level and to fix the rate such that it internalizes the externality.

To be accepted as fair, luxury tax revenues usually compensate those who bear the burden of the externality. This tax in MLB is, indeed, structured properly to achieve these goals, although no one knows whether the threshold payroll, the tax rate, and the beneficiaries of the redistribution are properly identified.

Salary Caps

The NBA [Ed. Note: and the NHL as well] is the only U.S. men’s professional sports league currently using individual player salary caps to control team expenditures. Maximum salaries are based on seniority in the league. Salary caps emerged from the NBA’s collective bargaining with the players’ union in 1998 and early 1999 at least partly in reaction to the league’s leaky team payroll cap.

Individual salary caps limit a team’s payroll to the product of the roster size times the cap for the most senior players—not a significant constraint. Individual salary caps based on seniority are unlikely to have much of an impact on competitive balance because a high-revenue team can sign a complete team at the highest allowed salary thereby accumulating an entire team of the most desirable players in the league. This is not likely to happen, however, because the most expensive team one can buy is also an old team. A team can assemble a more competitive roster paying less than the maximum.

If league rules constrain salaries, free agent players’ choices of which team to join will turn more on their personal preferences including desirable places to live and prospects for endorsements and a championship. Individual salary caps are likely to increase competitive imbalance because they encourage players to rely more on their preference for joining a winning team than on differences between salary offers. Salary caps will, however, limit the payroll of the high revenue teams, because they are the teams that would have bid above-cap salaries to acquire the more talented players. Individual player salary caps probably help the highest revenue teams increase both their profits and their playing talent.

Revenue sharing (see Marburger, 1997) reduces the financial incentive of each franchise to acquire more talent, because the payoff to winning is constrained by the share paid to other franchises. Sharing revenues that are sensitive to playing success blunts the incentive to win for all franchises—those in low-revenue potential locations as well as those in New York.