CHAPTER FOURTEEN

The NCAA and Conference Affiliation

INTRODUCTION

Intercollegiate athletics have been infused with a degree of commercialization since the earliest days of student competition. What is not as readily apparent, however, is the size of the college sports industry. This chapter and the one that follows explain the business of intercollegiate athletics from the perspective of the NCAA as a collective, its member conferences, and its individual member institutions.

This business of college sports, other than some international student participants, is an American phenomenon. The initial selection in this chapter by Noll provides a comprehensive overview of the financial aspects of intercollegiate athletics. A subsequent excerpt by the late Myles Brand, a university president turned NCAA president, highlights the concerns and challenges brought on by commercialization of intercollegiate athletics. As shown in Table 1, the primary asset of the NCAA is the Division I men’s basketball tournament. The NCAA budget was $661 million in the 2008–2009 season. Nearly 90%, or $590 million, of this amount was generated by the NCAA’s previous 11-year, $6.2 billion contract with CBS to broadcast what has become widely known as “March Madness,” as well as the NCAA’s marketing rights. The NCAA replaced the last 3 years of this deal with a 14-year, $10.8 billion contract with CBS and Turner (via its TBS, TNT, and truTV networks) through 2024, which will provide the NCAA with an average of $771 million per year. The NCAA cedes it marketing rights to CBS, which sells the sponsorships. Top-level NCAA sponsors (known as ‘corporate champions’) pay a reported $35 million annually, with second-tier sponsors paying a reported $10 to $12 million annually. Another 6%, or $41.8 million, was earned in ticket sales for this tournament. The organization’s remaining revenues (5%) were the result of gate receipts from all of its other tournaments across all three divisions ($18.6 million combined), as well as licensing efforts and other investments, sales, fees, and services ($9.8 million).

It is important to note that the NCAA does not control the revenues associated with the Division I-A football post-season, despite the fact that its revenue potential is seemingly much greater than that of basketball. Thus, individual conferences and schools (namely, Notre Dame) negotiate separate broadcast agreements for regular-season football; a separate coalition of top conferences and Notre Dame control the postseason through the Bowl Championship Series (BCS). All other postseason games are controlled by the promoters of the various independent bowl games that have entered into individual agreements with broadcast networks and cable channels to televise their contests. These bowls typically have arrangements with conferences to send predetermined place teams to play in the games. The article by Copeland explains the history of the NCAA’s hands-off approach to college football, which is a result of the Supreme Court’s 1984 decision in Board of Regents v. NCAA. The NCAA distributes the majority of its revenues to the members of Division I through various mechanisms. These distributions totaled $387.2 million, or 59% of the NCAA’s expenses in 2008–2009. (The details of these distributions are provided in the NCAA’s 2008–09 Revenue Distribution Plan later in this chapter.) Another $49.9 million, or 7.5%, of the NCAA’s revenues was distributed to the members of Divisions II and III, as is mandated by the NCAA constitution. The NCAA pays for all of the game and travel expenses for the schools participating in its 88 postseason tournaments in 23 sports, totaling nearly $64 million in 2008–2009, or 10% of its budgeted expenses. The NCAA also provides a number of programs and services for its members and athletes and spent $107.5 million in a wide range of areas in 2008–2009, or 16% of its budget. Finally, the NCAA’s expenditures on attorney’s fees, lobbyists, its internal governance and committees, staff salaries, and general and administrative services totaled over $27.9 million, or 4% of its budget, in 2008–2009.

Table 1 The National Collegiate Athletic Association Revised Budget for Fiscal Year Ended August 31, 2009

| REVENUE | 2008–09 Budget | Perecentage of Total Operating Revenue and Expenses |

Television and Marketing Rights Fees | 590,730,000 | 89.37% |

Championships Revenue | 60,430,000 | 9.14% |

TOTAL CHAMPIONSHIPS REVENUE | 651,160,000 | 98.51% |

Investments, Fees, and Services | 8,830,000 | 1.34% |

Membership Dues | 1,010,000 | 0.15% |

TOTAL NCAA OPERATING REVENUE | 661,000,000 | 100.00% |

| DIVISION SPECIFIC EXPENSES | ||

Total Distribution to Division I members | 387,227,000 | 58.58% |

Total Division I championships and programs | 64,046,775 | 9.69% |

TOTAL DIVISION I EXPENSE AND ALLOCATION | 451,273,775 | 68.27% |

TOTAL DIVISION II EXPENSE AND ALLOCATION | 28,886,000 | 4.37% |

TOTAL DIVISION III EXPENSE AND ALLOCATION | 21,020,000 | 3.18% |

TOTAL DIVISION SPECIFIC EXPENSES AND ALLOCATIONS | 501,179,775 | 75.82% |

| ASSOCIATION-WIDE EXPENSE-PROGRAMS AND SERVICES | ||

Total Student-Athlete Welfare and Youth Programs and Services | 22,785,800 | 3.45% |

Total Membership Programs and Services | 84,682,801 | 12.81% |

TOTAL PROGRAM AND SERVICES | 107,468,601 | 16.26% |

TOTAL ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICES | 27,899,525 | 4.22% |

Division II and III Championships and Program Support | (2,014,571) | –0.30% |

TOTAL ASSOCIATION-WIDE EXPENSES | 133,353,555 | 20.17% |

TOTAL NCAA OPERATING EXPENSES | 634,533,330 | 96.00% |

Contingencies and Reserves | 24,400,170 | 3.69% |

Collegiate Sports, LLC | 2,066,500 | 0.31% |

TOTAL CONTINGENCIES AND RESERVES | 26,466,670 | 4.00% |

TOTAL | 661,000,000 | 100% |

Source: National Collegiate Athletic Association. © National Collegiate Athletic Association. 2008–2010. All rights reserved.

Although there are 31 conferences in Division I, it is not surprising that the NCAA’s revenue-sharing system favors the members of the so-called BCS conferences—the “Big Six” athletic conferences that dominate Division I—the ACC, Big East, Big Ten, Big 12, Pac-10, and SEC. The NCAA’s distribution to athletic programs is based on three factors. First, the number of NCAA sports that the institution offers affects the amount of money that it receives from the association. With the distributed funds being directly proportionate to the number of teams fielded, the more comprehensive athletic programs receive larger amounts of NCAA monies. Only the Ivy League received more money than the Big Ten, ACC, and Big East in 2008–2009. Second, the number of athletic scholarships that a school offers to its students impacts its receipt of NCAA funds; the more athletic scholarships offered, the greater the amount of money received. The BCS conferences occupied the top six spots on this distribution list in 2008–2009. The third distribution is based on each conference’s performance in the men’s basketball tournament over the previous 6 years. Each of the BCS conferences received more from this distribution than any other conference. This should be expected given the depth and strength of these conferences and their dominance of college basketball. No school from outside of this power base has won a national championship in the sport since 1990. The dominance of these conferences is not limited to basketball. Overall, institutions from BCS conferences won 32 of the 35 Division I NCAA championships in which they competed in 2008–2009.

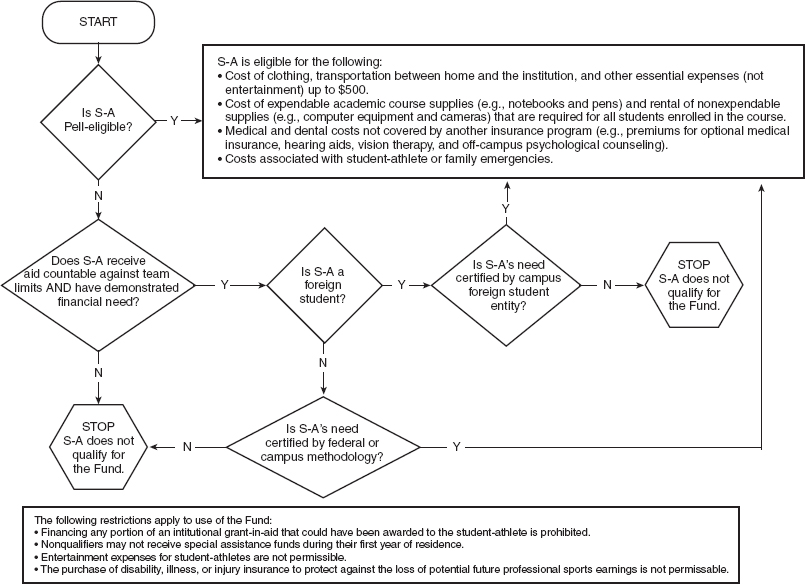

Though the other distributions to Division I institutions are divided far more equitably via the academic-enhancement fund, the special assistance fund for student-athletes, the student-athlete opportunity fund, and conference grants, they represent a much smaller amount of money—approximately one-quarter of the amount that is dispersed through the aforementioned athletic scholarships, sports sponsorship, and basketball funds. The chapter concludes with the NCAA’s 2008–2009 revenue distribution plan, which provides the exact details of its methodology, while the accompanying NCAA budgets and audited financial statements add color.

Although the ACC, Big East, Big Ten, Big 12, Pac-10, and SEC receive favorable NCAA distributions, a far greater advantage is gained from the revenue sources that the NCAA does not control: the negotiation of television agreements by these elite conferences for regular season and postseason conference basketball and football contests, ticket sales to the postseason conference basketball tournaments and conference football championship games, and the participation in postseason BCS bowl games by members of these conferences. The pursuit of increased revenues has led to periodic, dramatic shifts in the conference landscape, with some conferences strategically adding institutions in an effort to increase their long-term media revenues by adding geographic reach, to gain the ability to play a conference championship game in football by reaching the 12 schools required by NCAA rules, and to increase their dominance within their regional footprint. Other conferences then realign in an effort to preserve their existence. Indeed, yet another round of realignment was occurring in mid-2010 as this book was going to press, with several institutions switching membership among BCS and non-BCS conferences.

College conferences operate quite similarly to professional sports leagues in the negotiation of television agreements for football and basketball. Each conference pools certain rights of its member schools and enters into its own conference-wide broadcasting agreement, with the revenues typically divided equally among the member institutions. These contracts are lucrative. In addition, the ability of conferences either to launch or to contemplate launching their own networks to complement their existing national media contracts (a topic discussed in the context of professional sports in Chapter 8), has enabled them to dramatically increase their media-related revenues in their most recent agreements.

The Mountain West launched its own network (The Mtn.) in partnership with Comcast in 2006, which set the groundwork for the Big Ten to launch its own network (the Big Ten Network) the following year. The Big Ten Network is a 25-year deal with Fox Sports Network (a subsidiary of News Corp.) in which the conference owns 51% and Fox owns 49%. News Corp. has indicated in filings that the conference could receive $2.8 billion over those 25 years, an average annual value of $112 million. In addition, the Big Ten has a 10-year football and basketball agreement with ABC/ESPN, worth a projected $1 billion, that runs from 2008–2017 and a 10-year, $20 million football and basketball deal with CBS that runs from 2009–2018. The Big Ten’s media deals compare to those of the SEC. The SEC eschewed the possibility of launching its own network in favor of signing a pair of 15-year contracts with ESPN and CBS that run from 2009–2023 that provide the conference with a total of $2.25 billion from ESPN and $825 million from CBS, an average annual value of $205 million. This is a testament to the popularity of the conference both in its own regional footprint and on a national basis, as well as its dominance in college football.

The Big 12 conference signed a more traditional rights fee agreement with ABC/ESPN—an 8-year, $480 million deal (an average annual value of $60 million) through 2015–2016 for football, basketball, and Olympic sports. It complements this deal with a 4-year, $78 million contract with Fox Sports Net running through 2011 to air football games.

The Pac-10 conference has a 5-year, $125 million deal with ABC/ESPN through 2011; a 5-year, $97 million deal with Fox Sports Net through 2011 for football; and a 6-year, $52.5 million deal with Fox Sports Net through 2011–2012 for basketball. This last agreement is a multifaceted outsourcing deal that gives the cable outlet the exclusive right to sell, among other things, all Pac-10 basketball tournament sponsorship packages.

The ACC has a 12-year, $1.86 billion contract with ABC/ESPN through 2022–23, a deal that replaced a 7-year, $258 million deal with ABC/ESPN through 2010 for football and its 10-year, $300 million deal with Raycom Sports through 2010–2011 for basketball. The 130% increase in the annual average value of the deal (from an average of $66.9 million per year to an average of $155 million annually) was a product of a bidding war for the rights between Fox and ABC/ESPN. The Big East conference has proven to be quite strong at basketball and much weaker at football. This is reflected in its relatively small football/basketball media deal among the BCS conferences—a 6-year, $200 million deal with ESPN through 2012–2013 for basketball and through 2013 for football.

In 2009–2010, the BCS conferences of the Big Ten, SEC, ACC, Big 12, Pac-10, and Big East received television revenues of $242 million, $205 million, $78 million, $67 million, $58 million, and $33 million, respectively. The non-BCS conferences in Division I-A—the Mountain West, Conference USA, Western Athletic, Mid-American, and Sun Belt—earned $12 million, $11.3 million (including media/marketing revenues), $4 million, $1.4 million, and $1 million, respectively. These contracts indicate the popularity of big-time college football and basketball. Table 2 shows the various revenues and expenses of the SEC, ACC and Big Ten in recent years.

In addition, each of these conferences stages a profit-generating postseason basketball tournament, with revenues ranging from $2.8 million (SEC) to $7.3 million (ACC) in 2007–2008. Further, the Big 10, SEC, and ACC each have 12 schools, which allow these conferences to hold a post-season championship football game, as per current NCAA rules. These games generated $13.7 million for the SEC and approximately $5 million for the ACC in 2007–2008.

Table 2 Select Recent BCS Conference Financial Snapshots

| SEC Conference Revenues, 2009–2010 | |

| Source | Amount |

Football television | $109.5 million |

Bowl games | 26.5 million |

NCAA championships (all sports) | 23.5million |

SEC football championship game | 14.5 million |

Basketball television | 30.0 million |

SEC men’s basketball tournament | 5.0 million |

Total revenues | $209.0 million* |

*Each school received $17.3 million. This total does not include $14.3 million retained by institutions participating in bowls or $780,000 from the NCAA Academic Enhancement Fund.

Source: SEC.

| ACC Conference, 2007–2008 | |

| Source | Amount |

Revenues | |

Football television | $40.58 million |

Basketball television | 34.70 million |

Bowl games | 29.21 million |

NCAA basketball tournament | 15.07 million |

Other football revenue | 10.15 million |

ACC men’s basketball tournament | 6.50 million |

ACC football championship | 4.14 million |

Other basketball revenue | 3.73 million |

XM Satellite Radio fees | 1.50 million |

New member entry fee | 500,000 |

ACC women’s basketball tournament | 330,216 |

Total revenues | $162.76 million |

Expenses | |

Compensation/salary/wages/benefits | 4.16 million |

ACC basketball tournament | 1.88 million |

ACC football championship | 981,848 |

Bowl expenses | 659,204 |

Media relations | 394,580 |

Total expenses | $152.09 million* |

*Includes distribution of approximately $141.45 million to members.

Source: IRS Form 990.

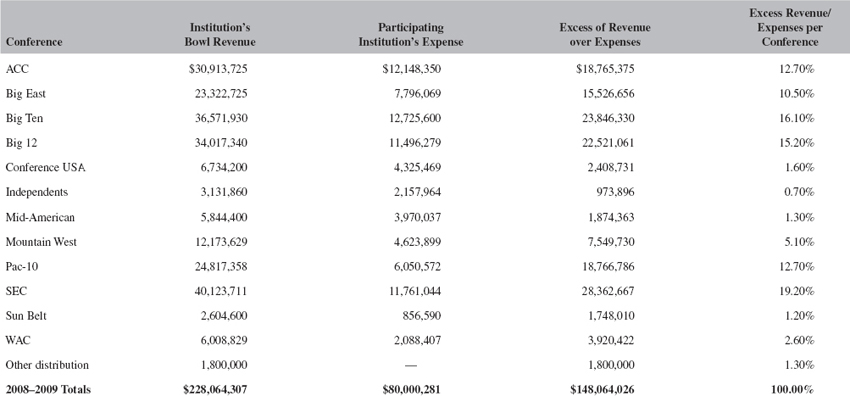

Football is the most important source of revenue for the elite conferences. Beyond the aforementioned television contracts and championship games, membership in a BCS conference (aside from Notre Dame) is nearly a prerequisite for participation in the Bowl Championship Series. The BCS is a coalition of the Fiesta, Orange, Rose, and Sugar Bowls and the BCS National Championship Game, which doled out over $125.5 million to the BCS conferences in 2008–2009. The five other Division I-A conferences, combined, shared approximately $19.3 million. There were 29 other, non-BCS bowl games in 2008–2009 that played host to a collection of lesser teams, most of which still came from the BCS conferences. The non-BCS bowl games distributed $79.9 million in 2008–2009, approximately three-quarters of which went to the elite conferences. Thus, while none of the BCS conferences earned total bowl revenues of less than the Big East’s $23.3 million, no other Division I-A conference earned bowl revenues greater than $12.2 million (Mountain West). Overall, the BCS conferences collected $189.8 million from bowl games played in 2008–2009, and the other five conferences reaped $36.5 million.

| Big 10 Conference, 2007–2008 | |

| Source | Amount |

Revenues | |

Sports Revenue | $206.77 million |

Operating revenue | 7.91 million |

Licensing program royalties | 1.33 million |

Championship events | 754,566 |

Membership Dues and Assessments | 935,000 |

Total revenues | $217.7 million |

Expenses |

|

Officiating Expenses | 551,599 |

Conference Office Programs | 1.44 million |

Distributions to member schools | 206.77 million |

Allen & Co. | 3.5 million |

Compensation of current officers, directors, key employees | 2.13 million |

Mayer Brown LLP | 690,148 |

Championship events | 822,890 |

Total expenses | $219.4 million |

Source: IRS Form 990.

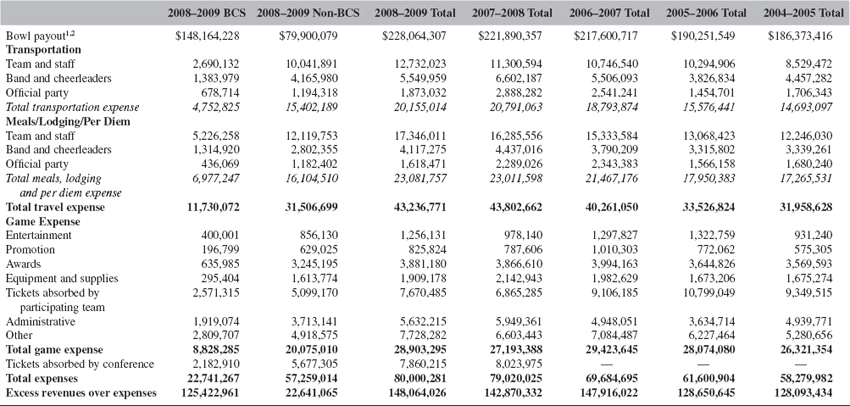

In addition to the substantial amount of revenue that is generated by participation in bowl games, there is also a significant expense associated with playing in these contests. Each institution must pay for the transportation, meals, housing, entertainment, awards, and per diem allowances for its team and coaching staff, marching band, cheerleaders, and official traveling party, many of whom arrive in the host city several days prior to the game. The participating schools also must sell an allotment of tickets to the game and are responsible for the cost of any unsold tickets. These expenses are much higher for the BCS bowls than the non-BCS ones. However, the expenses are more than offset by the revenues generated in the BCS games. The net distribution to conferences and institutions in the five BCS bowls was $125.4 million in 2008–2009. The 29 non-BCS bowls are quite different; their lower revenues resulted in a net distribution of $22.6 million in 2008–2009. Thus, the profit margin for BCS bowls was 85%, while it was only 28% for the non-BCS bowls in 2008–2009.

Each conference has a different formula for sharing the revenues that its institutions receive from bowl games and NCAA tournaments. Similar to professional sports leagues, a revenue sharing system that gives participating teams a disproportionate amount of the monies creates profit-maximizing behavior, including cheating, whereas one that is too generous to nonparticipating schools encourages free-riding among lesser teams and creates a disincentive for self-improvement. The key for each conference is to find the appropriate level of revenue sharing.

Although the BCS conferences generate substantial revenues, an existence in Division I outside of these conferences is much more difficult. At present, 25 other conferences play Division I basketball; 5 of these conferences play Division I-A football and 11 additional conferences play Division I-AA football; the remaining 9 conferences are in Division I-AAA and do not offer football. These “have-not” conferences generally struggle both competitively on the field and financially off of it. The 25 other Division I basketball conferences lag in total NCAA distributed revenues, with only two conferences (Conference USA and the Mid-American) receiving even half of what was received by any of the Big Six conferences in 2007–2008 and 16 receiving less than one-quarter. For the five other conferences participating in Division I-A football (Conference USA, Mid-American, Mountain West, Sun Belt, and Western Athletic), the situation is even more daunting. The problem facing these football programs is that they have a cost structure that is similar to the BCS conference programs (athletic scholarships, coaching staff, facility costs, etc.), but lack the popularity—the fan demand for tickets and television—to generate comparable revenues during the regular season. In addition, these schools receive a fraction of the revenues from bowl games that are earned by the BCS conferences, as previously noted. Finally, the eight conferences that participate in Division I-AA football are financially troubled. Though the cost structure is lower than it is in Division I-A because of the lower scholarship total (63) and smaller coaching staffs and infrastructure, it remains quite high in comparison to the paltry revenues generated. With its small attendance, little television coverage, and a largely ignored NCAA playoff in lieu of bowl games, Division I-AA football conferences have little hope for profitability.

FINANCIAL OVERVIEW

THE BUSINESS OF COLLEGE SPORTS AND THE HIGH COST OF WINNING

Roger C. Noll

Intercollegiate athletics is a strange business—one whose profits end up in the most unlikely pockets. But I’m getting ahead of the story.

For some 50 colleges and universities, football and men’s basketball are modest enterprises that generate enough revenues to cover full scholarships for about 100 athletes—and, in a good year, to yield a profit of a few million dollars. At a few universities, women’s basketball is also profitable, and baseball is more or less a break-even operation. For all other sports, and for major sports outside the top group of colleges, intercollegiate athletics is a financial drain. Yet almost all American colleges and universities field an impressive array of men’s and women’s teams across a variety of sports that have few players and virtually no spectators.

What’s more, intercollegiate sports chronically generate serious controversy that leaves college administrators cringing behind their desks. The media regularly report scandals about drug use, criminal activity, excessive financial aid, and poor academic performance punctuated by low graduation rates. No less important, big-time sports cause friction among faculty and university administrators. Some see sports as diverting resources and attention to an unimportant—even frivolous—non-academic activity. Explicit favoritism to athletics also is controversial. If coaches are paid more than Nobel Prize winners, if athletes have larger scholarships and better dorms than academic superstars, are colleges transmitting the wrong lessons to students and society at large? And if college sports cast so dark a shadow, why do they endure?

WHY AMERICAN UNIVERSITIES SUPPORT SPORTS

To the rest of the world, American intercollegiate athletics seem like pagan rituals. Universities rarely sponsor athletics teams—let alone encourage them to play before thousands or to appear on television.

The popularity of intercollegiate sports in the United States is not driven by Americans’ greater interest in sports….

Nor are intercollegiate sports popular because more Americans follow sports that first interested them as students. Intercollegiate athletics in the United States has been a popular entertainment since the beginning of the century, when the fraction of Americans who had gone to college was far lower than the proportion of college-educated Europeans and Japanese today.

Finally, the special prominence of American intercollegiate athletics is not explained by television exposure. College sports were popular before radio and long before television. Moreover, since Europe has liberalized broadcasting by allowing cable television, sports on cable has proliferated—but not intercollegiate sports.

So why do American colleges devote so much effort to sports? Primarily, because their students demand it as athletes, not as spectators. Public enthusiasm focuses on the so-called revenue sports—basketball and football. But the vast majority of college athletes play other, minor sports, for which no significant demand exists other than from the athletes themselves. The inescapable conclusion: universities have comprehensive varsity athletics programs largely because students want to be athletes. And they compete to enable students to follow their interests, whether in physics or field hockey, linguistics or lacrosse.

THE FINANCIAL STAKES IN SPORTS

Colleges and universities follow diverse policies regarding intercollegiate athletics. The vast majority sponsor teams with no expectation of generating revenues. Indeed, the typical intercollegiate sports program is based on the traditional amateur model.

But focusing on the typical ignores the big-time sports schools with multimilliondollar profit centers in basketball and football, and the many other schools that dabble in the so-called revenue sports. The NCAA divides colleges and universities into three divisions according to the depth of their financial commitment. The top group, Division I, is further subdivided into I-A and I-AA for football. And even this categorization understates the extent of diversity.

In Divisions II and III, sports are relatively low-cost activities. Most schools use part-time coaches, play only nearby competitors and give few athletic scholarships…. This sum is not large compared to a university budget. But a small liberal arts college with 1000 students may end up spending 5 to 10 percent of tuition on a comprehensive sports program.

At the top of the heap are about three dozen Division I-A schools that compete for national championships in several sports including football and both men’s and women’s basketball. Just below are another dozen mostly small, Catholic colleges that have the same ambitions in all but football. At these schools, game attendance for the trophy sports approaches the numbers for professional sports. They expect to be in the NCAA championship basketball tournament and, if they play Division I football, in a postseason bowl.

PUNTING ON FOOTBALL

The financial returns from football can be very large for top teams. Typically, they play six or seven games at home, bribing weaker schools to be cannon fodder against far superior opponents in front of large crowds….

The top teams also expect to appear on television almost every week … although in most conferences the money must be shared with other conference members. Notre Dame does even better since it sells national television rights to all its home games and does not belong to a conference.

In addition, bowl games guarantee a payoff … per team. For teams picked for a top bowl game … the payoff is several million dollars—although, for most schools, bowl income, too, must be shared with conference members…. [Ed. Note: Tables 3, 4, 5, and 6 show revenues generated by bowl games.]

For the rest of the Division I-A football teams and all of the ones in Division I-AA, television exposure is unusual … Thus, these teams must get by on revenues about one-tenth that of their superpower brethren—a reality that explains why most jump at the chance to earn a few hundred thousand dollars to be drubbed by Penn State or Michigan.

Football team operating costs are driven by the school’s business strategy. Does it try to field a ranked team that will go to a major bowl? If so, the team must play interregional foes, running up travel costs of hundreds of thousands per trip….

Management costs typically are attributed to something other than salary—endorsements, in-kind payments (e.g., a mansion, a Cadillac)—in order to keep compensation in line with that of top faculty. But this practice is mainly a public-relations device: competition for top coaches insures that, one way or another, they are paid according to their ability to generate revenue. By contrast, a team that does not aspire to national ranking can minimize travel costs and rely on mediocre veterans for coaching. Stadium operation costs are roughly proportional to attendance….

The major source of differences among teams’ financial aid budgets is tuition. Tuition depends on the quality, reputation, and scope of activities of the school as well as whether it is public or private. All athletic scholarships include about $12,000 for room and board so that 85 scholarships (the Division I-A ceiling for football) cost about $1 million plus tuition….

Scholarship costs explain why two-thirds of Division I basketball schools do not play in Division I-A football. Athletics departments at private schools need to dish out two or three times more in aid to play Division I-A football as do most public schools. Thus for nearly all private schools in Division I, football revenues can’t come close to covering the costs of scholarships, coaches, travel, equipment, and stadium operations. So very few opt in.

1Average expense allowance for BCS participating institutions is $1,713,406, and average expenses are $2,108,645.

2Average expense allowance for non-BCS participating institutions is $876,198, and average expenses are $987,224.

Source: National Collegiate Athletic Association, April 10, 2009. © National Collegiate Athletic Association. 2008–2010. All rights reserved.

Table 4 Distribution of BCS Revenue, 2008–2009

| Conference | Distribution of Revenue |

Big Ten | $23,172,725 |

Southeastern | 23,172,725 |

Big 12 | 23,172,725 |

Pacific 10 | 18,672,743 |

Atlantic Coast | 18,672,725 |

Big East | 18,672,725 |

Mountain West | 9,788,800 |

Western Athletic | 3,224,000 |

Conference USA | 2,659,200 |

Mid-American | 2,094,400 |

Sun Belt | 1,529,600 |

Notre Dame | 1,331,860 |

Big Sky | 225,000 |

Atlantic 10 | 225,000 |

Mid-Eastern | 225,000 |

Gateway | 225,000 |

Ohio Valley | 225,000 |

Southwestern Athletic | 225,000 |

Southland | 225,000 |

Southern | 225,000 |

U.S. Military Academy | 100,000 |

U.S. Naval Academy | 100,000 |

Total BCS Distribution | $148,164,228 |

Source: National Collegiate Athletic Association, April 10, 2009. © National Collegiate Athletic Association. 2008–2010. All rights reserved.

Table 5 Postseason Bowl Average Information,2008–2009

| Non-BCS Bowl | BCS Bowl | |

Average bowl payout | $2,755,175 | $29,632,858 |

Average expenses | 1,974,449 | 4,546,253 |

Average net to conferences and institutions | 780,726 | 25,086,605 |

Source: National Collegiate Athletic Association, April 10, 2009. © National Collegiate Athletic Association. 2008–2010. All rights reserved.

Tuition does not necessarily reflect actual costs to the university. A key consideration is whether the school is at its enrollment ceiling. At highly rated academic schools—California, Duke, Michigan, Northwestern, Stanford, U.C.L.A., Wisconsin—many applicants are rejected who would be willing to pay all of the university’s charges. So the decision to subsidize another athlete is a decision not to admit someone who might pay full tuition.

But where an extra athlete does not displace a tuition-payer, the cost of admitting 85 football players is very small compared to the average cost of providing the education. Thus, if an under-enrolled private school can generate enough revenue from football to pay the tuition of its players, the tuition payments are gravy for the university.

Capital facilities are a very important cost of football. In theory, a university could go into debt to build a stadium, and then cover the debt from its operating budget. But, in practice, capital investments are covered by special fundraising drives or, for public universities, by separate appropriations. The reason is simple: no university generates a large enough surplus to justify the capital expenditures necessary to field a football team.

….

March Madness

Basketball operates on a smaller gross, but with disproportionately lower costs. Like football, the best basketball schools play more home games than the worst, with cash changing hands to arrange unbalanced schedules. A dozen Division I men’s teams have a home attendance of around 300,000 per season, while some 50 draw more than 100,000.

Colleges ration student attendance to sell more tickets at higher prices. The best men’s basketball teams have game revenues … plus television revenues…. A few top women’s teams take in over $1 million. But most of the 50 or so schools that try to field a ranked team and usually make the NCAA championship tournament have revenues below this.

The NCAA has a complex formula, based on past success, for dividing the profits from the NCAA tournament. Nearly all payments go to conferences that share revenues, so a school’s tournament revenue depends more on the success of its conference than its own record. [Ed. Note: Tables 7 and 8 show distribution amounts to Division I conferences.]

….

Over 300 schools play Division I basketball, compared to over 100 in Division I-A football and about 80 more in Division I-AA….

Basketball is far less expensive than football because teams need pay only 15 scholarships and travel with fewer than 15 players. Coaches are paid about the same as in football, but staffs are smaller….

As in football, the cost of a scholarship to the athletics department can run from $12,000 to over $30,000. But even in the latter case, the total team cost is under $500,000. Thus revenue … is more than sufficient to pay the out-of-pocket costs of a team at a private school, and half that can do the job at an inexpensive public school….

WHAT’S IN IT FOR SPORTS U?

Schools not well known outside their home region can benefit indirectly from a successful Division I team by increasing applications for admission. Whether this actually helps the school, though, depends upon its circumstances. A school at its enrollment ceiling will gain only to the extent that it can be more selective in admissions. But a private school that has trouble filling its dorms can admit more students and collect more tuition. Even an extra 100 students at $20,000 each represents a serious piece of change for the average university.

Source: National Collegiate Athletic Association, April 10, 2009. © National Collegiate Athletic Association. 2008–2010. All rights reserved.

Table 7 2007–2008 NCAA Total Distribution to Members

| Conference | Amount |

America East | $6,686,913 |

Atlantic 10 | 11,416,499 |

Atlantic Coast | 29,422,225 |

Atlantic Sun | 3,584,429 |

Big 12 | 28,381,052 |

Big East | 29,949,918 |

Big Sky | 4,961,818 |

Big South | 4,629,776 |

Big Ten | 31,215,888 |

Big West | 5,191,129 |

Colonial Athletic | 9,884,737 |

Conference USA | 18,272,537 |

Horizon League | 6,219,609 |

Independents | 381,402 |

Ivy Group | 6,784,213 |

Metro Atlantic | 4,504,154 |

Mid-American | 12,894,716 |

Mid Eastern | 5,615,508 |

Missouri Valley | 9,531,408 |

Mountain West | 12,448,714 |

Northeast | 6,156,454 |

Ohio Valley | 6,180,611 |

Pacific-10 | 25,390,458 |

Southeastern | 27,662,076 |

Southern | 5,671,294 |

Southland | 5,792,809 |

Southwestern | 5,142,029 |

Sun Belt | 9,397,222 |

The Patriot League | 6,226,305 |

The Summit League | 3,648,105 |

West Coast | 4,623,771 |

Western | 10,434,348 |

Total | $358,302,127 |

Source: National Collegiate Athletic Association. © National Collegiate Athletic Association. 2008–2010. All rights reserved.

Some claim that big-time sports can increase donations to academic programs. But several studies have concluded that athletics has essentially no effect on contributions to the school outside the athletics programs. The only plausible source of an indirect financial benefit is through the enrollment effect: if more and better students attend, the university might receive more alumni gifts a few decades later.

The vast majority of departments of athletics do not make a profit, even from the two revenue sports. Indeed, a majority of Division I schools lose substantial amounts on football and, at best, break even on basketball. Thus, for all schools outside (and most in) Division I, intercollegiate athletics is a financial drain—commonly hundreds of dollars annually per student enrolled.

Table 8 2007–2008 Division I Basketball Fund Distribution

| Conference | Amount |

America East | $1,337,093 |

Atlantic 10 | 4,393,307 |

Atlantic Coast | 15,090,053 |

Atlantic Sun | 1,146,080 |

Big 12 | 15,663,093 |

Big East | 16,618,160 |

Big Sky | 1,337,093 |

Big South | 1,337,093 |

Big Ten | 13,561,946 |

Big West | 1,719,120 |

Colonial Athletic | 2,674,187 |

Conference USA | 8,213,573 |

Horizon League | 2,865,200 |

Independents | 0 |

Ivy Group | 1,146,080 |

Metro Atlantic | 1,337,093 |

Mid-American | 1,910,133 |

Mid Eastern | 1,146,080 |

Missouri Valley | 4,775,333 |

Mountain West | 4,011,280 |

Northeast | 1,146,080 |

Ohio Valley | 1,146,080 |

Pacific-10 | 12,606,880 |

Patriot League | 1,528,107 |

Southeastern | 14,708,026 |

Southern | 1,146,080 |

Southland | 1,337,093 |

Southwestern | 1,146,080 |

The Summit League | 1,146,080 |

Sun Belt | 1,146,080 |

West Coast | 2,674,187 |

Western | 3,247,227 |

Total | $143,259,997 |

Source: National Collegiate Athletic Association. © National Collegiate Athletic Association. 2008–2010. All rights reserved.

For the top schools that do profit from their revenue sports, the profits are significant. But the money rarely accrues to the academic side of the university. Competition is fierce for high-end coaches—as well as for people who can run big-time athletics departments efficiently. Thus, much of the surplus from revenue sports is spent on salaries.

What’s more, universities are inclined to spend anything left on unremunerative sports. This phenomenon has been boosted by the requirement for gender equality in varsity athletics. Women have no counterpart to football with its 85 scholarships. So in the wake of legal requirements to balance gender participation in varsity sports, football schools have been forced either to drop some men’s sports or to add women’s. Schools that make a lot of money on football pursue the second strategy. After all—returning to the earlier theme—men and women students alike want more women’s sports, not fewer men’s sports.

“CHEATING” AND THE ROLE OF THE NCAA

Athletics scandals typically arise from violations of the NCAA’s rules, and thus are commonly labeled as “cheating” to emphasize the idea that the offending institutions are attempting to gain advantages unfairly. These scandals fall into three categories. The first is excessive financial assistance to student-athletes—under-the-table payments or no-show jobs. The second is toleration of antisocial behavior that does not directly affect athletic performance—drug use, theft, violence, or simply low academic performance that would not be tolerated for nonathletes. The third is toleration of performance-enhancing drugs or training regimes that consume most of a student’s time. All of these rules violations follow from the financial incentives facing universities and, especially, coaches.

… To obtain a job at one of the 30 or so universities that aspire to the first tier in revenue sports, a coach must first win consistently at a lower level. Then, to keep a plum job or move on to the pros, a coach must win consistently against quality opponents. At the very top schools, winning seasons without major bowl victories in football or a shot at the quarterfinals in [the] NCAA basketball tournament will lead to dismissal.

The basic principle behind the NCAA’s rules regarding competition for athletes is that it must be limited to two dimensions: the overall college environment and the skills of the coach. Many highly skilled athletes are in college to prepare for professional sports careers. They seek scholarships for one purpose: to obtain experience and training needed to advance to the pros with the least possible disruption to what they do off the playing field. And like other adolescents, some athletes cut class, take drugs, beat up other students and, on occasion, knock off a liquor store if they think they can get away with it.

For a coach, success assures a decades-long career with a salary of hundreds of thousands of dollars. And with few exceptions, coaches have no alternative employment opportunities anywhere near as lucrative. Consequently, a coach facing an athlete who wants extra money (or a free pass on school rules) has compelling reasons to succumb.

Persistent rule breaking by coaches is not likely to go unnoticed by vigilant university administrators. But the incentive to cheat spills over if they regard athletic performance as a way of attracting students or encouraging the generosity of alumni and state legislators. All that is needed to let cheating persist is inattention.

The cheating label is a device for generating adverse publicity that might pressure universities to adhere to the NCAA’s rules. But looking behind the public relations, much of what the NCAA and the press call cheating is not ethically questionable.

The NCAA’s financial rules are incredibly detailed, frequently picayune, and vigorously enforced. Isolated minor infractions usually lead to minor penalties: While at Stanford, Tiger Woods regained eligibility when he reimbursed Arnold Palmer for dinner. But repeated minor violations are interpreted as a sign of laxity in a university’s enforcement efforts. When U.C.L.A. was placed on probation in basketball, the documented crimes were repeated gifts of T-shirts and Thanksgiving dinners.

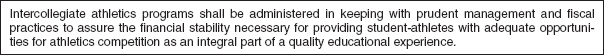

THE NCAA CARTEL

Economists who have studied intercollegiate sports unanimously agree that the NCAA is the harshest price-fixing cartel in all athletics, amateur or professional. Recall that an athletic scholarship actually covers only about $10,000 in basic living costs. The rest goes for tuition, books, and other fees. For an athlete who has no interest in the educational aspects of being a college athlete, the part of a scholarship that covers academics has no value. If attending college were regarded as more or less a full-time job, the student-athlete could do better working an equivalent number of hours at a fast-food restaurant. The problem from the athlete’s perspective is that McDonalds does not field a football team. [Ed. Note: See Figure 1 for the stated economic policy of the NCAA.]

Financial cheating arises because an athlete is worth more to a university and its fans than the NCAA scholarship limit. If five good players can increase the revenue of a men’s basketball team from $1 million to $3 million—still a modest amount—these players are worth $400,000 each. Thus if schools were to bid competitively for these athletes, the winning bids would be ten times more than the list price of a year at Stanford.

Where would this money come from? Some, presumably, from subsidies now going to minor sports. Some would come from coaches’ salaries, because recruiting superstar athletes would no longer be as profitable. And for a handful of top sports schools, some would come out of profits now used to cover academic expenditures.

Figure 1 NCAA Constitution Article 2.16

Source: 2008–2009 NCAA Division I Manual, p. 5. © National Collegiate Athletic Association. 2008–2010. All rights reserved

The beneficiaries of the NCAA scholarship rules are thus athletes in other sports, the very best coaches, and, in rare cases, academic programs. For the most part, these beneficiaries are either highly paid or from families with above-average incomes. By contrast, NCAA financial rules harm the star athletes in football, men’s basketball, and, to a lesser degree, women’s basketball—athletes who disproportionately come from lower-income families. Thus, the NCAA financial rules are primarily a means of redistributing income regressively.

The overall impact of the financial rules varies enormously among schools and students. For a minority of college athletes, including some in minor sports, the main benefit of intercollegiate athletics is preparation for a professional sports career. For those who do become pros, the payoffs are very large and college life is a far more pleasant way to gain experience and acquire training than playing in minor leagues. In this sense, college athletes are not exploited because their alternatives are less attractive.

Nevertheless, the prospects for a pro career are poor in every sport. Each year, about 1500 men receive Division I basketball scholarships, while 2000 receive Division I-A football scholarships. Of these, about 150 will ever play an N.B.A. game, and about 250 will ever play in the N.F.L. Moreover, most of the athletes who succeed as pros will come from the elite athletics programs….

For scholarship athletes who never become pros, intercollegiate sports can provide two other benefits. One benefit—competition itself—is frequently overlooked because of the focus on preparing athletes for pro careers. Nevertheless, this benefit is not trivial.

Then, too, a college degree has a big effect on lifetime income. The return to the investment in college is very high and has increased sharply in the last two decades. Thus for a serious student, a free education at a private university is worth not just the $100,000-plus scholarship, but another $200,000 in the “present value” of the extra income the student will earn over a lifetime.

At the other end of the spectrum, if a school has no academic standards or graduates few athletes, restrictions on scholarships are just an instrument for taking advantage of the NCAA price-fixing cartel. In the trophy sports, many scholarship athletes do not take academics seriously and very few graduate, so that they do not enjoy the postgraduation benefits of higher education.

For these, the majority of Division I scholarship athletes, college is nothing more than an opportunity to play organized sports for a few more years before facing the reality of adulthood. The nub of the issue about the place of sports on campus is whether these athletes, numbering a few thousand in all sports combined, are better off in college than out. For the most part, they enjoy their college experiences—but not for anything having to do with academics.

PLAYING BY THE RULES

On paper, the NCAA’s rules seem to say that college is for athletes ready to benefit from the academic side of school. For the most part, however, the NCAA’s rules [that are] unrelated to money or the games themselves are minimal and rarely enforced. The NCAA does maintain eligibility rules for both admissions and grades. But these requirements are actually very low—well below the formal admissions requirements for universities and colleges with well-regarded academic programs, including many schools that compete in Division I athletics. Indeed, in the trophy sports only a small fraction of athletes who could play regularly for a top team satisfy the normal admissions requirements of the academically oriented colleges.

To maintain eligibility, the NCAA insists that athletes be registered as full-time students, remain in good academic standing, and make normal progress toward a degree. But since schools are extremely heterogeneous in their academic standards, these requirements boil down to very little. Good standing means whatever the university decides. Normal progress toward a degree means almost nothing, since progress is not judged retrospectively by actual graduation results. Most schools graduate a third or fewer of scholarship athletes in the trophy sports and some graduate none.

With respect to antisocial behavior, the NCAA’s basic rule is that athletes should be treated like other students. As a result, if a school does not expel other students for felonies, they need not expel athletes. In most cases, universities’ disciplinary actions are taken on a case-by-case basis. And some schools are perfectly happy to field a team of alleged perpetrators who, when they behave the same way in the pros, are suspended.

In theory, the NCAA also limits the time athletes can spend on sports. But these rules have no bite. If coaches and universities want a longer season, the NCAA accepts extended time limits. And for some sports, the “season” is the academic year.

The hours-per-week limit is more an accounting formality than a strict constraint. The norm is to practice far more than the limits allow, so that each athlete “voluntarily” decides to commit extra time to training in order to compete effectively against others who devote extra time to training.

By contrast, the prohibition against performance-enhancing drugs is rigidly enforced. Student-athletes sometimes are declared ineligible to compete in NCAA events after taking prescription drugs for an illness. While athletes often protest the NCAA’s testing protocols, the strict rules against steroids, painkillers, and stimulants definitely serve their long-term interests.

THE TRUE IMPACT OF THE NCAA CARTEL

Step back, and the picture is clear: the NCAA is mostly a device for “cartelizing” universities while doing little to enforce standards of academic performance and social behavior among student-athletes. With the exception of the prohibition against performance enhancing drugs, the only rules that are both strict and vigorously enforced pertain to limiting financial aid. Thus, to judge solely by cause and effect, the NCAA is mostly interested in suppressing payments to athletes in a way that benefits coaches and the athletes who play minor sports.

The NCAA’s inclinations are also revealed by its other business activities. Until the mid-1980s, the organization required all colleges and universities to give the NCAA a monopoly in television rights for daytime Saturday football games. The practice ended only after the rule was declared a violation of antitrust law. This court decision led to the proliferation of football telecasts on cable channels, which reduced the total fees collected by colleges, increased the disparity in television revenues among colleges (favoring the strongest football programs) and substantially increased the total number of Saturday games available to viewers.

….

The NCAA’s rules on the number of games go far beyond what is necessary to limit the demands on athletes. That objective could be achieved by a much simpler rule …. This cynical conclusion is not intuitively obvious, and to some seems to deny the organization’s history. Early in the [last] century, football came very close to being banned because it had become so violent and dangerous. The NCAA rewrote the rules of play to solve this problem, and hardly anyone would dispute the legitimacy of this role.

A few decades later, as intercollegiate football became more important many schools abandoned the principle of a student-athlete, and became professional operations. The NCAA’s present limits on the number and value of scholarships and its academic requirements arose to combat this professionalization.

But the NCAA’s rules do not prevent professionalization among universities that seek to pursue it. Indeed, by making certain that coaches and schools—not athletes—are the main beneficiaries, the NCAA makes the problem worse by giving them a reason to abandon academic values in pursuit of athletic glory.

ARE INTERCOLLEGIATE SPORTS A DESTRUCTIVE INFLUENCE?

Perhaps 50 colleges and universities participate in trophy sports to generate revenues, with the benefits going in part to coaches and athletic administrators, in part to other sports, and, in a few cases, to academic programs. For all other sports, and even for trophy sports at all but the top programs, intercollegiate sports exist not to make money but to please important constituencies—primarily students. If all universities collectively banned intercollegiate sports or athletic scholarships, higher education as a whole probably would be stronger financially than it is.

But this is far from the complete story. Most colleges and universities also would be better off financially if they agreed to eliminate comparative literature and advanced mathematics. The difficult question is whether varsity sports bring enough value to universities to offset their costs. And part of the answer revolves around the scandals that surround athletics.

Scandals embarrass universities and undermine their moral authority as transmitters of social values. But scandals are not intrinsic to intercollegiate sports. Intercollegiate athletics create scandals only in schools that are powers in trophy sports—or seek to become powers.

The incentive of coaches to win is a necessary component of the incentive to break the rules. And much of this is created by the cartel aspects of the NCAA’s rules, which limit the cost of all programs and substantially increases the profitability of trophy sports at top schools.

If the NCAA behaved less like a cartel, the financial benefit of on-field success would be smaller. In turn, salaries for top coaches would fall, and schools would have less reason to recruit athletes who seek only a pro career and not an education. Moreover, relaxed rules would lead to fewer violations and fewer scandals. Cutting to the chase, if colleges had to pay something closer to market value for top athletes, they would admit fewer of them and be less interested in athletes who are likely to be behavioral problems.

The economics of intercollegiate athletics is not a story of administrators willfully perverting academic values for the fast buck. Such things do happen, but this is not an accurate characterization of the vast majority of intercollegiate sports programs. The more fundamental force driving college sports is the intense interest that so many students and alums have in sports. And the idea that colleges would abandon something as universally popular as intercollegiate athletics is a fantasy.

But things could be far better. Higher education and society at large would be better served if the NCAA did not limit scholarships or set the price for postseason events in trophy sports.

OPTIONS

Breaking up the NCAA cartel is probably as unrealistic a goal as banning intercollegiate athletics. Any effort to eliminate the cartel aspect of the NCAA would probably lead many Division I schools to set up a rival organization that adopted the practices the NCAA now follows. If the schools that value athletics most highly all joined the new cartel, reforming the NCAA would have little effect.

So what, if anything, can be done? Perhaps, not much.

Too many people currently involved in sports, from coaches to athletes in non-trophy sports to the commercial interests that cohabit with [the] best college sports programs, would fight hard to preserve the business as usual. Moreover, as the demand for revenue sports rises along with affluence and leisure time in America, the financial incentives to do well in trophy sports will only grow. The future is likely to be a larger version of the past.

But for optimists in the crowd, there are a couple of plausible routes to reform. The first is to attack the NCAA through antitrust laws. The NCAA has already lost its television monopoly this way. And an unrelated antitrust suit forced a consortium of elite universities to abandon collusion on need-based financial aid. But an antitrust suit would be slow and expensive. And it would probably require the active involvement of the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice, which is notably uninterested.

The Justice Department’s reluctance is understandable: The Federal Trade Commission was barred from attacking the NCAA on the ground that it is only allowed to enforce competition in for-profit markets. Moreover, unlike the television case in which some universities had financial incentives to break the NCAA’s control, private parties are unlikely to pursue the antitrust route on scholarships or postseason play.

Another way to castrate the cartel would be to alter the existing rules in ways that change the universities’ incentives.

….

The key to change in all these proposals parallels the general drift of economic policy reform in the past three decades: rely more on incentives and less on rules. The practical way to make the values of intercollegiate sports more closely parallel the academic values of universities is to give universities less incentive to abandon academic values.

UNBOUND: HOW A SUPREME COURT DECISION TORE APART FOOTBALL TELEVISION AND RIPPLED THROUGH 25 YEARS OF COLLEGE SPORTS

Jack Copeland

Twenty-five years ago this summer, the thread that leads to today’s NCAA began unspooling from the chambers of the U.S. Supreme Court. That was when Justice John Paul Stevens wrote that the Association’s control of football games on television violated antitrust law. Six of his colleagues signed on in agreement.

The 7–2 decision on June 27, 1984, resulted from a legal challenge filed nearly three years earlier by the Universities of Georgia and Oklahoma. The schools argued the NCAA’s Football Television Plan, through which the Association controlled broadcasts of weekly national and regional games on TV and cable networks, illegally blocked them from striking their own deals.

Just two weeks later, the Association grappled during a special meeting in Chicago with a future in which members no longer would share in football-television revenues that had topped $260 million under the voided plan. There, representatives of 111 schools argued over whether the NCAA should attempt to salvage the plan with a new agreement that would address antitrust concerns, then essentially voted to leave members free to pursue their own contracts.

The Division I Men’s Basketball Committee also gathered about that same time in Colorado, and Richard Schultz, then director of athletics at Virginia, was attending his first meeting as a new member. He remembers the group taking a break so that he and others could fly to Chicago for the football discussion.

“There were a lot of tensions out there as the lawsuit was coming together … and there was some tension once (the decision) came down,” Schultz recalled. “Where I was, the tension was mainly, what’s going to happen, how’s this going to impact financially, and so forth.”

Schultz returned to Colorado, and the basketball committee resumed planning to implement an expansion to 64 teams in 1986—a move that just seemed like a natural step at the time but that soon sparked an explosion in the tournament’s popularity and value.

Then, everyone—the administrators who struggled through that postmortem in Chicago, and Schultz and the other stewards of the basketball tournament that now was the NCAA’s most prized possession—went home. So did members of the newly formed NCAA Presidents Commission, which had gathered in Chicago for a scheduled organizational meeting just three days after the court ruling and whose agenda included a request from the NCAA Council for presidents to consider the idea of a major-college football playoff.

All returned home from those meetings and began picking up that thread unspooling from the Supreme Court.

That thread soon would lead Schultz into leadership of the NCAA, ultimately put presidents in charge of decision-making for the organization and lead to an array of once-unimagined challenges as it pulled the Association into the future.

Five years ago, journalist Keith Dunnavant wrote about the 1984 decision in his book titled “The 50-Year Seduction,” calling NCAA vs. University of Oklahoma Board of Regents an “earthquake.” The book detailed “how television manipulated college football, from the birth of the modern NCAA to the creation of the BCS,” as the subtitle put it.

If what happened in 1984 was an earthquake, there now have been 25 years of aftershocks.

“The Board of Regents decision fundamentally shaped the future of college athletics, and college football in particular, because it created a future denominated by the chase for TV sets,” Dunnavant explained….

“You can draw a line from the Board of Regents decision to the expansion of the SEC to the death of the Southwest Conference to the birth of the Big 12 to the emergence of the Atlantic Coast Conference. Also, without the decision—and how it affected what I call a civil war political climate within big-time college football—you would not have the Bowl Championship Series today,” he said.

“It is the absolute common denominator to the modern era of the sport that we see today.”

The decision’s impact on college football, that “civil war political climate” and a lengthy struggle to capitalize on the newly opened TV marketplace is well-documented in books written by Dunnavant and others, including one by the NCAA’s executive director at the time of the ruling, Walter Byers.

By the time he published “Unsportsmanlike Conduct” in 1995, Byers had come to believe the organization—which he had nurtured from the establishment of a national headquarters in the 1950s through the achievement of rules-enforcement authority, financial security and new championship opportunities for both men and women—had lost its way in serving the students playing the sports.

He argued the NCAA should not limit the term or value of athletics scholarships, should not prevent athletes from holding a job or otherwise restrict outside income, should repeal restrictions on transfers and should permit consultation with agents in making decisions about sport careers. He also said if the NCAA does not take these steps unilaterally, it should be forced to do so by legislative action.

Byers looked at those contentious days around the Board of Regents case from that perspective and judged the focus on football as too narrow. He suggested that Oklahoma, Georgia and other schools that joined forces through the College Football Association could have dismantled the NCAA for the sake of reform but instead “missed a politically propitious moment to restructure control of college athletics, dazzled instead by TV glamour and the prospect of network dollars.” As a result, rather than destroying the Association, the Board of Regents case prompted the NCAA to regroup and reassess—whether through day-to-day business like that basketball committee meeting in Colorado or decisions by the NCAA Executive Committee and Council and at annual Conventions.

“Organizations, like the people who inhabit them, generally need time to absorb and operationalize major changes,” wrote Joseph Crowley, a former NCAA membership president, in his history of the Association in 2006, “In the Arena: The NCAA’s First Century.”

“Refinements are often necessary. Midcourse corrections often occur. Leaders have the responsibility of monitoring the pace of change and maintaining a protective balance between reform and organizational stability. Hard choices have to be made in the process. Tall orders may take a while.”

Perhaps those words best describe the thread that the NCAA followed through the quarter century after Justice Stevens’ opinion.

During the NCAA’s 2006 Convention, three of the Association’s four chief executives (Schultz, Cedric Dempsey and Myles Brand) and a stand-in for Byers (retired Big Ten Conference Commissioner Wayne Duke, who had worked beside Byers after establishment of the national office in Kansas City) participated in a panel discussion celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Association’s founding.

Schultz, Dempsey and Brand each stressed the importance of the Board of Regents decision, as did Duke, who recalled Justice Byron White’s dissenting opinion in the case, which argued that the NCAA television plan should be preserved because it “fosters the goal of amateurism by spreading revenues among various schools and reducing the financial incentives toward professionalism.”

Yet, even as the foursome agreed that the decision was a key milestone in the NCAA’s history, Brand provocatively suggested that it merely altered the course that history followed—not the outcome.

“I’m of the opinion that if that case had gone the other way, we still might be exactly where we are now,” he said then. “The names might have changed and some of the contractual arrangements would be different, but I’m not sure there would be anything different in the end.”

It’s an interesting question: Would the NCAA be different today if it had won, rather than lost, that 1984 antitrust case?

Brand’s predecessor, Dempsey, largely agrees today with Brand, though he thinks some of the most difficult issues he faced during his tenure leading the NCAA from 1994 to 2003 stemmed directly from the 1984 ruling.

“It created a vulnerability that the NCAA had never had before to legal actions, an area in which it had tremendous success before that time,” he said…. “It unfortunately, I think, began to separate out the major programs in the country, by giving them a feeling of—and in actuality—greater control. Had it not been for ’84, we might not have had the same kind of restructuring approach in Division I that occurred 12 years later.

“It had a tremendous impact upon the current structure and certainly the philosophy of intercollegiate sports.”

Schultz agrees that a fundamental frustration expressed via the Board of Regents case—that a relatively small number of schools were producing revenue for the Association but had limited say in how it was distributed—lingered as the newly expanded 64-team basketball tournament exploded in popularity. Eventually, it won a $1 billion television contract for the NCAA with CBS in 1989.

“I had one or two athletics directors at various times say, ‘Well, we might just pull out of basketball and go out on our own.’ And I said, well, fine, go ahead and do that,” Schultz recalled. “I said, ‘You’ve got a great model in front of you in football. You saw what happened to football television when you went out.’”

What happened is that football television revenue plummeted as conferences and schools began competing for the best deals from the relatively small number of media outlets available at the time to carry games. What had been a seller’s market suddenly was a buyer’s market, as The NCAA News reported three weeks after the Supreme Court decision, and just a week after that Chicago meeting.

“It was many, many, many years before the (football) rights fees on a per-game basis began to approach what they were at the end of the NCAA program,” said Tom Hansen, the recently retired commissioner of the Pacific-10 Conference….

Dempsey observed the same dissatisfaction among the membership tier that contributed most to the Association’s wealth, and perhaps felt it even more acutely than Schultz.

“From ‘84 to ‘96, there were always different things that would come up, and there would always be that veiled threat, well, if you don’t do this, we’re going to get out,” he recalled.

That dissatisfaction flowered as Schultz was leaving office in 1993 and Dempsey assumed the post at the 1994 NCAA Convention. A group of Division I-A commissioners circulated a restructuring proposal at that Convention calling for creation of a 15-member “board of trustees” consisting of institutional presidents and dominated by what it termed “equity” conferences to replace the Council and Presidents Commission, as well as an end to one-institution, one-vote rulemaking at the Convention.

“Most of it had to do with revenue-sharing and determining their own destiny, and not having it be determined by people who didn’t have the same kind of challenges that they had with their programs,” Schultz said.

Three years later, the NCAA membership essentially adopted the plan proposed by the commissioners, after hammering out provisions designed to maintain links between the three membership divisions even as it reorganized into a “federated” structure meant to give each division authority over its own affairs. (Divisions II and III retained the one-institution, one-vote approach to deciding issues.)

“I think that had to take place, and it would have taken place with or without the Board of Regents decision,” Schultz said. “In fact, the decision to do that may have come sooner (if the NCAA had won the case).”

Dempsey agrees federation was inevitable, but worries about whether the Association got it right in the details of governance.

“Out of that, we lost a lot,” he suggested. “Those institutions still could have maintained control in the way they wanted without throwing out the baby with the bath water, if you will.

“As I go to campuses, people just don’t feel part of the Association any longer. And all of the benefits that used to accrue from going to the Convention—and I know there were a lot of negatives, having to sit and listen to the other two (divisions), though I think those were handled by federation—it could have been handled much differently.”

Even so, restructuring brought peace organizationally that the Association had not experienced since before the College Football Association formed in the late 1970s.

For several years after the Board of Regents decision, NCAA members struggled within the Association’s structure to determine who would call the shots for the organization, while vying outside that structure—sometimes in something resembling hand-to-hand combat—to capitalize on the freedom provided by the Supreme Court to sell the appeal of college sports for media consumption.

The “civil war” Dunnavant referred to essentially was a rivalry pitting the College Football Association against the Big Ten and Pacific-10 Conferences. The conflict often did resemble a series of battles, as the sides skirmished in courtrooms and schools deserted longtime conference affiliations to boost the television appeal of a rival league. One key player, Notre Dame, struck a separate peace of sorts by breaking ranks with the CFA and negotiating its own network television contract.

But just as those “equity” conferences found a way to co-exist in a shared authority over the Division I governance structure within the NCAA, they also found a way through what has come to be known as the Bowl Championship Series to work together on the problem of football television.

The Board of Regents decision led directly to a dramatic increase in the number of games aired not only by the old-line networks such as CBS, NBC and ABC, but also by then fledgling cable outlets such as ESPN and the Turner Broadcasting System. It may have driven down the amount that schools earned per game for a television appearance, but over time it opened up many more opportunities for teams to appear on TV—though leagues with less negotiating clout ended up playing on Tuesday or Wednesday or Thursday night.

“I find it ironic that today, each of the (Division I Football Bowl Subdivision, formerly Division I-A) conferences has just about the same resources committed to football television that the NCAA did to run the entire country back in those days,” the Pacific-10’s Hansen said. “We all have multiple staff members involved in telecasting football, and in most cases, basketball also.”

Those institutions may have wrestled authority over football television away from the NCAA on antitrust grounds, but that didn’t exempt those institutions from antitrust scrutiny themselves—a problem that frustrated efforts to group the most attractive games into one television package. But a breakthrough of sorts came as the conferences dealt with complaints from many quarters—ranging from broadcast partners to fans—over the traditional football bowl system’s inability to satisfy the American desire to determine a national champion.

“The creation of the BCS was the symbolic reunification of big-time college football, because it effectively was what amounted to the old CFA schools coming together to create a better postseason structure, but that would not have been possible but for the inclusion of the Big Ten and the Pac-10 coalition,” Dunnavant said.

“The breakdown of that resistance really placed a period at the end of a very divisive era.”

The collaboration may or may not ultimately produce a football playoff (Dunnavant suspects it will), but regardless of the outcome, it’s interesting to ask that question again: Would things have turned out differently if the NCAA had prevailed in the Supreme Court in 1984?

“I think there’s a good possibility that we might have a limited football playoff in (the former) Division I-A if the NCAA still had control,” Schultz said. “We came very close to it when I was there.”

Schultz said that at one point in his administration, Division I-A presidents in the governance structure were ready to support a playoff but backed off in the face of criticism from colleagues in another division. Then, not long before his departure, Schultz unsuccessfully proposed a two-week playoff to Division I-A conference commissioners that he argued would bring schools three to four times more revenue than they were collecting from existing bowl games, while retaining those games.

Attractive as those revenues might be, it would have required the conferences to give up at least a measure of control over the playoff—and perhaps in those pre-federation days, control over who would receive the proceeds.

So, is the NCAA different today than it would have been if the Supreme Court had been persuaded to follow Justice White’s lead, rather than Justice Stevens?

It lost revenue from football television, but quickly replaced it with revenue from the basketball tournament, which Schultz believes exploded in popularity and value after expansion to 64 teams because “every community, every state, that had a team with 17 or 18 wins or close to 20 wins by the time the selection process came around thought their team was going to be in the tournament for the very first time.”

It afforded Schultz and the membership an opportunity to share revenues without requiring recipients to make what he has called “the $350,000 free throw” to advance deeper into the tournament, while supporting programs ranging from catastrophic-injury coverage to various initiatives directly serving student-athlete development and well-being.

“It probably satisfied some of those schools that were getting football revenue when it was controlled and then lost that football revenue afterwards, and were able to pick up the additional revenue in basketball,” Schultz said. “From a financial standpoint, that eased a lot of fears.”

The NCAA has changed structurally, but perhaps the Supreme Court’s decision better equipped the Association to work collaboratively to address issues.

“It’s still alive and, overall, well,” Dempsey says. “The NCAA has adjusted to the will of the membership pretty well, and will continue to do so. It will make the changes that are necessary, from time to time, as issues come up.”

Those issues are many. Can the expense of operating large athletics programs be controlled? Will the Association achieve its ambitious efforts to improve the academic performance of athletes? Should it take greater advantage of commercial opportunities to generate more revenue if doing so directly benefits students at member schools?

It likely will require another spool of thread to find those answers.

THE 2009 NCAA STATE OF THE ASSOCIATION SPEECH, AS DELIVERED BY WALLACE I. RENFRO, NCAA VICE PRESIDENT AND SENIOR ADVISOR TO PRESIDENT MYLES BRAND, JANUARY 15, 2009

Myles Brand

….

This paper and speech is the result of significant thought, discussion and writing that Dr. Brand has given to the relationship of commercialism to sports, a relationship that exists because sports is a significant part of the human experience.

It is present in our lives from children’s play to the most elite professional contests.

Our language is filled with sports metaphors, and we ease into deeper conversations by finding neutral ground in sports talk.

The relevance of sports to our global culture was made evident when China used the attention of the Olympics for two weeks in August to announce that it is moving back onto the world stage. In America, we have developed a rich tradition for both participation and consumption.

There are a variety of professional sports leagues in America from lacrosse to ice hockey, from soccer to football, from golf to basketball.

Indeed, there are more than two dozen professional leagues.

But, as pervasive as professional sports has become in this country, college sports occupies a central place in the American culture.

It has become integral to many of our universities and colleges, institutions which are the guardians of our traditions and histories and the harbingers of our futures. College sports generates a significant economic impact in communities all across the country.

The estimated annual budget for all of intercollegiate athletics is $6 billion.

A large number.

But to help put that number in perspective, it should be noted that the total spent by athletics departments in America each year would not fully fund even two of this nation’s largest public universities for a year, where annual budgets for a single comprehensive public research university range from $3 to $4 billion.

Unlike professional sports, however, the bottom line in the collegiate model is not the bottom line.

It is not creating profits for owners and shareholders.

The reason America’s colleges and universities sponsor athletics—for more than a century and a half now—is the positive effect participation has on the lives of young men and women.

We should feel good in knowing college sports empowers these young people to become contributing members of their communities and country.

College sports rely on the hard and good work of many, and we should praise those who coach and administer intercollegiate athletics.

Indeed, we could easily spend our time today citing the successes of intercollegiate athletics.

There are innumerable and wonderful stories that need to be told.

Make no mistake: sports in college are very, very good.

We should all be unabashed advocates. Nonetheless, intercollegiate athletics is faced with issues it must resolve.