THE IMPACT OF COLLEGE SPORTS SUCCESS ON THE QUANTITY AND QUALITY OF STUDENT APPLICATIONS

Devin G. Pope and Jaren C. Pope

1. INTRODUCTION

Since the beginning of intercollegiate sports, the role of athletics within higher education has been a topic of heated debate.1 Whether to invest funds into building a new football stadium or to improve a school’s library can cause major disagreements. Lately the debate has become especially contentious as a result of widely publicized scandals involving student athletes and coaches and because of the increasing amount of resources schools must invest to remain competitive in today’s intercollegiate athletic environment. Congress has recently begun to question the National Collegiate Athletic Association’s (NCAA) role in higher education and its tax-exempt status. Representative Bill Thomas asked the president of the NCAA, Dr. Myles Brand, in 2006: “How does playing major college football or men’s basketball in a highly commercialized, profit-seeking, entertainment environment further the educational purpose of your member institutions?”2

Some analysts would answer Representative Thomas’s question by suggesting that sports does not further the academic objectives of higher education. They would argue that intercollegiate athletics is akin to an “arms race” because of the rank-dependent nature of sports, and that the money spent on athletic programs should be used to directly influence the academic mission of the school instead. However, others suggest that because schools receive a variety of indirect benefits generated by athletic programs, such as student body unity, increased student body diversity, increased alumni donations, and increased applications, athletics may act more as a complement to a school’s academic mission than a substitute for it. Until recently, evidence for the indirect benefits of the exposure provided by successful athletic programs was based more on anecdote than empirical research.3 Early work by Coughlin and Erekson (1984) looked at athletics and contributions but also raised interesting questions about the role of athletics in higher education. Another seminal paper (McCormick and Tinsley 1987) hypothesized that schools with athletic success may receive more applications, thereby allowing the schools to be more selective in the quality of students they admit. They used data on average SAT scores and in-conference football winning percentages for 44 schools in “major” athletic conferences for the years 1981–1984 and found some evidence that football success can increase average incoming student quality.4 Subsequent research has further tested the increased applications (quantity effect) and increased selectivity (quality effect) hypotheses of McCormick and Tinsley but has produced mixed results.5 The inconsistent results in the literature are likely the product of (1) different indicators of athletic success, (2) a limited number of observations across time and across schools, which has typically necessitated a cross-sectional analysis, and (3) different econometric specifications.

This study extends the literature on the indirect benefits of sports success by addressing some of the data limitations and methodological difficulties of previous work. To do this we constructed a comprehensive data set of school applications, SAT scores, control variables, and athletic success indicators. Our data set is a panel of all (approximately 330) NCAA Division I schools from 1983 to 2002. Our analysis uses plausible indicators for both football and basketball success, which are estimated jointly in a fixed effects framework. This allows a more comprehensive examination of the impact of sports success on the quantity and quality of incoming students. Using this identification strategy and data, we find evidence that both football and basketball success can have sizeable impacts on the number of applications received by a school (in the range of 2–15%, depending on the sport, level of success, and type of school), and modest impacts on average student quality, as measured by SAT scores.

Because of concerns with the reliability of the self-reported SAT scores in our primary data set, we also acquired a unique administrative data set that reports the SAT scores of high school students preparing for college to further understand the average “quality” of the student that sports success attracts. These individual-level data are aggregated to the school level and allow us to analyze the impact of sports success on the number of SAT-takers (by SAT score) who sent their SAT scores to Division I schools. Again, the panel nature of the data allows us to estimate a fixed effects model to control for unobserved school-level variables. The results of this analysis show that sports success has an impact on where students send their SAT scores. This analysis confirms and expands the results from the application data set. Furthermore, this data makes it clear that students with both low and high SAT scores are influenced by athletic events.6

Besides increasing the quality of enrolled students, schools have other ways to exploit an increased number of applications due to sports success: through increased enrollments or increased tuition. Some schools that offer automatic admission to students who reach certain quality thresholds may be forced to enroll more students when the demand for education at their school goes up. Using the same athletic success indicators and fixed effects framework, we find that schools with basketball success tend to exploit an increase in applications by being more selective in the students they enroll. Schools with football success, on the other hand, tend to increase enrollments.

Throughout our analysis, we illustrate how the average effects that we find differ between public and private schools. We find that this differentiation is often of significance. Specifically, we show that private schools see increases in application rates after sports successes that are two to four times higher than seen by public schools. Furthermore, we show that the increases in enrollment that take place after football success are mainly driven by public schools. We also find some evidence that private schools exploit an increase in applications due to basketball success by increasing tuition rates.

We think that our results significantly extend the existing literature and provide important insights about the impact of sports success on college choice. As Siegfried and Getz (2006) recently pointed out, students often choose a college or university based on limited information about reputation. Athletics is one instrument that institutions of higher education have at their disposal that can be used to directly affect reputation and the prominence of their schools.7 Our results suggest that sports success can affect the number of incoming applications and, through a school’s selectivity, the quality of the incoming class. Whether or not the expenditures required to receive these indirect benefits promote efficiency in education is certainly not determined in the present analysis. Nonetheless, with the large and detailed data sets we acquired, combined with the fixed effect specification that included both college basketball and football success variables, while controlling for unobserved school-specific effects, it is our view that the range of estimates showing the sensitivity of applications to college sports performance can aid university administrators and faculty in better understanding how athletic programs relate to recruitment for their respective institutions.

Section 2 of this article provides a brief literature review of previous work that has investigated the relationship between a school’s sports success and the quantity and quality of students that apply to that school. Section 3 describes the data used in the analysis. Section 4 presents the empirical strategy for identifying school-level effects due to athletic success. Section 5 describes the results from the empirical analysis. Section 6 concludes the study.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

Athletics is a prominent part of higher education. Yet the empirical work on the impact of sports success on the quantity and quality of incoming students is surprisingly limited. Since the seminal work by McCormick and Tinsley (1987), there have been a small number of studies that have attempted to provide empirical evidence on this topic. In this section we review these studies to motivate the present analysis.

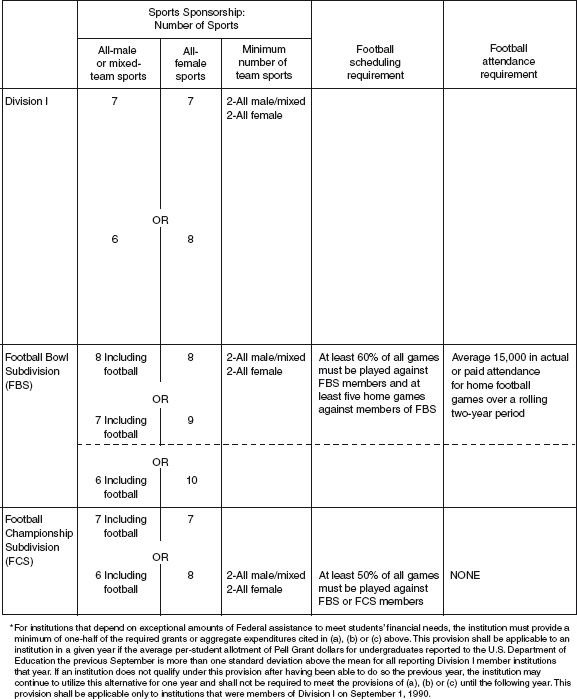

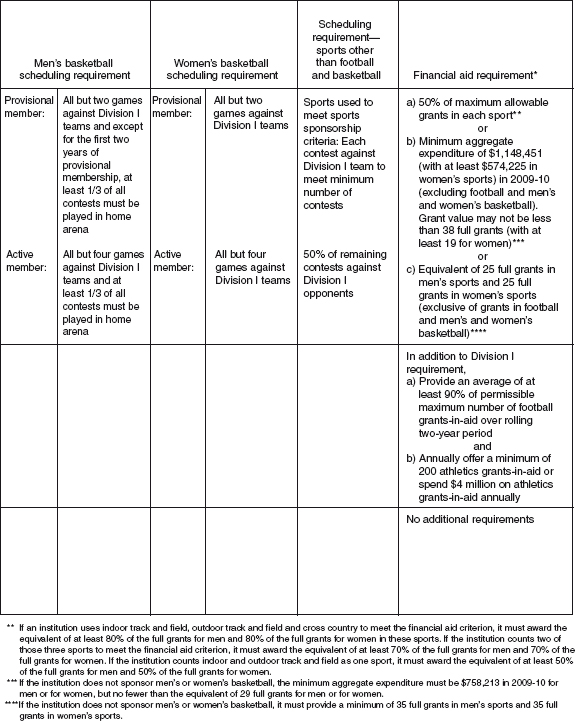

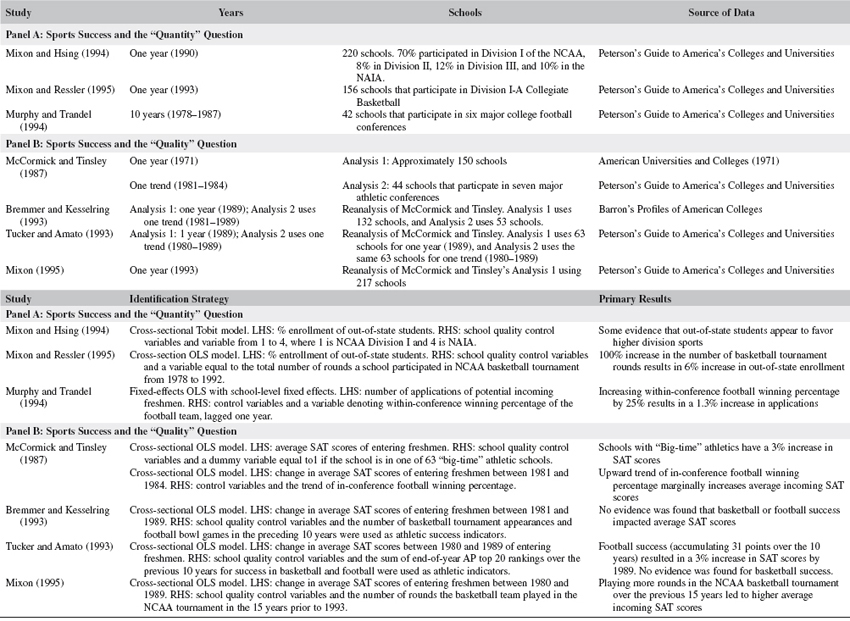

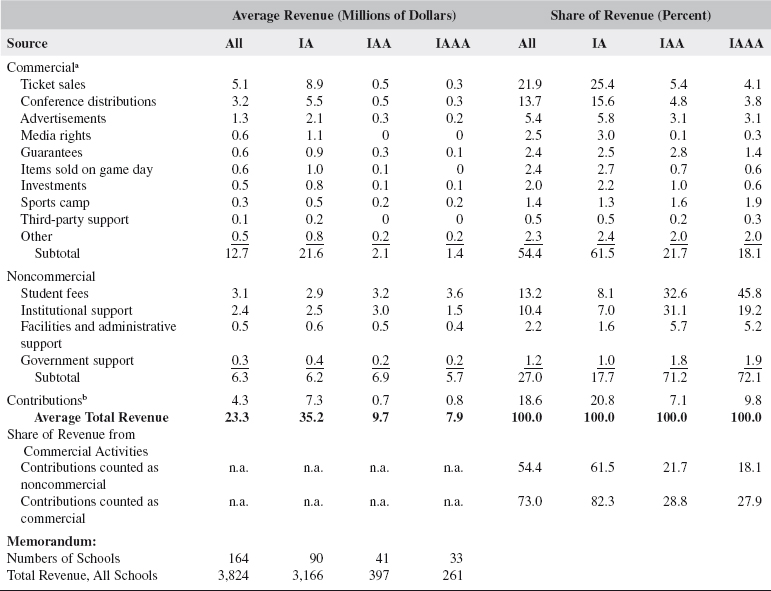

Table 13 provides a summary of the previous literature.8 The table is divided into two panels. Panel A describes the studies that have directly or indirectly looked at the relationship between sports success and the quantity of incoming applications. These studies have found some evidence that basketball and football success can increase applications or out-of-state enrollments. Panel B describes the studies that have looked at the relationship between sports success and the quality of incoming applications. These studies all reanalyze the work of McCormick and Tinsley (1987) using different data and control variables. The results of these studies are mixed. Some of these analyses find evidence for football and basketball success affecting incoming average SAT scores; whereas, others do not.

Differences in how the studies measured sports success make it difficult to compare the primary results of these studies. For example, Mixon and Hsing (1994) and McCormick and Tinsley (1987) use the broad measures of being in either various NCAA and National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) athletic divisions or “big-time” athletic conferences to proxy prominent and exciting athletic events at a university. Basketball success was modeled by Bremmer and Kesselring (1993) as being the number of NCAA basketball tournament appearances prior to the year the analysis was conducted. Mixon (1995) and Mixon and Ressler (1995), on the other hand, use the number of rounds a basketball team played in the NCAA basketball tournament. Football success was measured by Murphy and Trandel (1994) and McCormick and Tinsley as within-conference winning percentage. Bremmer and Kesselring used the number of football bowl games in the preceding 10 years. Finally, Tucker and Amato (1993) used the Associated Press’s end-of-year rankings of football teams. While capturing some measures of historical athletic success, many of these variables may fail to capture the shorter-term episodic success that is an important feature of college sports.

Perhaps more important to the reliability of the results of these studies than the differences in how sports success was measured are the data limitations they faced and the resulting identification strategies employed. All of the analyses except for that of Murphy and Trandel (1994) use a single year of school information for a limited set of schools.9 For example, Mixon and Ressler (1995) collected data from Peterson’s Guide for one year and 156 schools that participate in Division I-A collegiate basketball. The lack of temporal variation in these data necessitates a cross-sectional identification strategy. A major concern with cross-sectional analyses of this type is the possibility that there is unobserved school-specific information, correlated with sports success, that may bias estimates. In fact, much of the debate surrounding differences in estimates in these cross-sectional analyses hinges on arguments about the “proper” school quality controls to include in the regressions. Another concern is the college guide data typically used. It is widely known that the self-reported data (especially data on SAT scores) from sources such as U.S. News & World Report and Peterson’s can have inaccuracies or problems with institutions not reporting data.10

….

Table 13 Summary of Previous Literature

LHS = left-hand side; RHS = right-hand side.

Source: Southern Economic Journal. Used with permission.

3. PRIMARY DATA SOURCES

… Athletic success likely has two primary components that affect college choice decisions: historic athletic strength and episodic athletic strength. The data sets we use allow us to control for historic athletic strength and analyze episodic athletic strength.

We use three primary data sets to conduct our empirical analysis. Each of these data sets is compiled so that the unit of observation is an institution of higher education that participates in Division I basketball or Division I-A football. The first data set is a compilation of sports rankings, which are used to measure athletic success. The second data set provides school characteristics, including the number of applications, average SAT scores, and the enrollment size for each year’s incoming class of students. The third data set provides the number of SAT scores sent to each institution of higher education. The main features of these three data sets are discussed in more detail below.

Football and Basketball Success Indicators

Our indicator of football success is the Associated Press’s college football poll….

It is widely agreed that the greatest media exposure and indicator of success for a men’s college basketball team (particularly on a national level) comes from the NCAA college basketball tournament. “March Madness,” as it is often called, takes place at the end of the college basketball season during March and the beginning of April. It is a single elimination tournament that determines who wins the college basketball championship. Before 1985, 48–53 teams were invited to the tournament each year. Since 1985, 64 teams have been invited to play each year.13 We collected information on all college basketball teams that were invited to the tournament between 1980 and 2003. From these data we created dummy variables that indicate the furthest round in which a team played. In our analysis, we use the rounds of 64, 16, 4, and champion. A team’s progress in the NCAA tournament provides a good proxy of a basketball team’s success in any given year during the time frame of the data.

….

College Data

As discussed in Section 2, a weakness of earlier studies on the impacts of athletic success was the limited number of observations across time and across schools. In an attempt to rectify this shortcoming, we purchased access to a licensed data set from the Thomson Corporation that contains detailed college-level data. Thomson Corporation is the company that publishes the well-known “Peterson’s Guide to Four Year Colleges.” … We restrict the data set to the 332 schools that participated in NCAA Division I basketball or Division I-A football between 1983 and 2002.

….

SAT Test-Takers Database

The third data set that we use is derived from the College Board’s Test-Takers Database (referred to as SAT database in the remainder of the paper).15 ….

After completing the test and questionnaire, students may indicate up to four colleges where their test scores will be sent for free. Students may also send their scores to additional schools at a cost of $6.50 per school. The data set identifies up to 20 schools to which a student has requested his scores be sent.18 ….

The SAT data set will allow us to further explore how college applicants with different SAT exam scores are affected by football and basketball success. Unlike the self-reported data from sources such as Peterson’s Guide, all the data in the SAT database are reported, and inaccuracies are almost nonexistent. These data also allow us to better analyze the impact of sports success on the SAT score sending of students with high, middle, and low SAT scores. By aggregating these high-quality individual-level data to the school level, the impact of sports success on the quality of incoming SAT scores that a school receives can be analyzed. These results will complement the analysis conducted with the applications database.20

4. EMPIRICAL STRATEGY

Many school characteristics cannot be observed by the econometrician, yet these unobservables are likely correlated with both indicators of sports success and the number of applications received by a school. The unobservable component is likely to include information about scholastic and athletic tradition, geographic advantages, and other information on the true quality of the school. Without adequately controlling for these unobservables, they would likely confound the ability to detect the impact of athletic success on the quantity and quality of incoming students. The nature of the data we have compiled allows us to plausibly control for the unobservables associated with each school.

Even after including school fixed effects and linear trends for each school, it is always worrisome that schools that perform well in sports in a given year are schools that have recently improved academically as well. If this is the case, the effects of sports success on application rates and student quality may be spurious. To try and deal with this issue, we include one-year lead sports dummy variables in our regression to estimate the effect that having sports success next year has on this year’s applications. If the results suggest that future sports success does not predict current admission figures, this would lend credibility to our empirical strategy.

….

Timing of the Impact of Athletic Success

….

The NCAA Division I-A football season finishes at the beginning of January. The NCAA basketball tournament finishes at the end of March or beginning of April. Therefore, if these sports influence the number of applicants a school receives, we would expect an effect on the current year variables. This means that a successful football team that finishes in January or a successful basketball team that finishes in March will affect application decisions for students enrolling that fall. However, given the timing of when applications were likely prepared and submitted, and the football and basketball seasons, one would possibly expect an equally large impact of football and basketball to be on the first lag of an athletic success variable (especially for basketball, which ends three months after football). The second and third lags will give an indication of the persistence of the athletic success which occurred two to four years earlier.

5. RESULTS

Results Using Peterson’s Data

… For basketball, the results suggest that being one of the 64 teams in the NCAA tournament yields approximately a 1% increase in applications the following year, making it to the “Sweet 16” yields a 3% increase, the “Final Four” a 4–5% increase, and winning the tournament a 7–8% increase. The impact of the athletic lags is as we expected. Although there is an effect of winning on the current year’s applications, the largest effect comes in the first lag. By the third lag, the effect has usually diminished substantially…. For football, the results suggest that ending the season ranked in the top 20 in football yields approximately a 2.5% increase in applications the following year, ending in the top 10 yields a 3% increase, and winning the football championship a 7–8% increase. The largest effect is on the current football sports variable, along with a small effect on the first lag…. The results from these regressions suggest that for basketball private schools receive two to four times as many additional applications than public schools as they advance through the NCAA tournament, while the results for football are less conclusive. Furthermore, the application impact for private schools appears to be more persistent. For example, when a private school advances to the Sweet 16, it enjoys an 8–14% increase in applications for the next four years; whereas, a public school sees only a 4% increase for the next three years.

Besides being more selective, schools might react to increased applications by increasing their enrollment or tuition levels…. The results indicate that teams that have basketball success do not enroll more students the following year. However, schools that perform well on the football field in a given year do increase enrollment that year. Teams that finish in the top 20, top 10, and champion in football on average enroll 3.4%, 4.4%, and 10.1% more students, respectively. These results are all significant … this is largely driven by public schools. This increased enrollment could come from the fact that many public schools give guaranteed admission for certain students. For example, a school that guarantees admission for in-state students with a certain class rank or test score may be required to enroll many more students if demand suddenly spikes. Another possible reason for the increased enrollment is that more of the students that a university admitted decide to actually attend that year (higher matriculation rate), which would increase enrollment.

…. The results suggest that private schools increase tuition following trips to the Final Four (results are also suggestive for tuition increases by private schools after winning the basketball championship) but not for football success. There is no consistent evidence that public schools adjust tuition because of sports success. However, this is likely because many public schools have political constraints on increasing tuition.

…. [S]chools that do well in basketball are able to recruit an incoming class with 1–4% more students scoring above 500 on the math and verbal portions of the SAT. Similarly, these schools could also expect 1–4% more of their incoming students to score above 600 on the math and verbal portions of the SAT…. [H]owever, to examine the effect of sports success on SAT score categories in the Peterson’s data set, approximately 1600 observations of the 5335 are dropped due to missing SAT data. Therefore it is important to further examine the “quality” effect using the SAT data set.

Results Using SAT Database

…. The results indicate that sports success increases SAT-sending rates for all three SAT subgroups. However, the lower SAT scoring students (less than 900) respond to sports success about twice as much as the higher SAT scoring students. For example, schools that win the NCAA basketball tournament see an 18% increase a year later in sent SAT scores less than 900, a 12% increase in scores between 900 and 1100, and an 8% increase in scores over 1100. Also, private schools tend to see a larger increase in sent SAT scores after sports success than for public schools (although this does not appear to be true for the basketball championship and high SAT scores). For example, it can be seen that when a private school reaches the Sweet 16 in the NCAA basketball tournament, they have two to three times as many SAT scores sent to them as the public schools in the first and second periods after the basketball success. Furthermore, the effect tends to persist longer for the private schools than the public schools, as can be seen on lags 2 and 3…. A similar difference between public and private schools can be seen for football. The championship round cannot be compared, as there were no private schools that won the football championship during this time period.

Overall, these results suggest that schools that have athletic success are not receiving extra SAT scores solely from low performing students. The results also greatly strengthen the SAT results derived from the Peterson’s data. It appears that athletic success does indeed present an opportunity to schools to be either more selective in their admission standards or enroll more students while keeping a fixed level of student quality.

….

6. CONCLUSION AND FUTURE RESEARCH

“How does playing major college football or men’s basketball in a highly commercialized, profit-seeking, entertainment environment further the educational purpose of your member institutions?” Fully answering Representative Thomas’s question that he posed to the president of the NCAA is beyond the scope of this study. However, the analysis presented above does provide a set of estimates about the impact of sports success on the quantity and quality of student applications at schools participating in the premier divisions of NCAA basketball and football. These estimates reflect several indirect benefits from these high-profile college sports.

Using two unique and comprehensive data sets in conjunction with an econometric design that controls for the unobservable features of schools, we find that football and basketball success increases the quantity of applications to a school after that school achieves sports success, with estimates ranging from 2% to 8% for the top 20 football schools and the top 16 basketball schools each year.24 We also provide evidence that the extra applications are composed of students with both low and high SAT scores. Additional evidence suggests that schools use these extra applications to increase both student quality and enrollment size. There is some evidence that private schools adjust tuition levels in response to receiving extra applications from basketball success.

A related paper (Pope and Pope 2007) shows that sports success has a heterogeneous impact on various subgroups of the incoming student population. For example, we found that males, blacks, and students that played sports in high school are more likely to be influenced by sports success than their peers. This finding, combined with the results of this paper, provides a much broader picture of the impact of sports success on the composition of the incoming student body. These results significantly extend the existing literature and provide important insights about the impact of sports success on college choice. Using identification strategies that exploit the temporal variation in our data sets and that control for unobserved school heterogeneity, it is increasingly clear that sports success does have an impact on the incoming freshman classes. It is also clear that this impact is often short lived, and that it differs by student type. This may reflect differences in the ability of various student subgroups to acquire quality information that would affect school choice, or it may simply reflect preferences for high-quality athletics.

Whether or not the expenditures required to receive these short-run indirect benefits promote efficiency in higher education was not determined in the present analysis. Indeed, the raw summary data … would suggest that athletically successful schools actually saw slightly slower long-run growth in applications and enrollments. Future work directed at understanding the arms-race nature of athletics within higher education and its relation to economic efficiency would certainly be valuable. Nonetheless, the results presented in this paper should be important to college administrators. Athletics is one instrument that institutions of higher education have at their disposal that can be used to directly affect reputation and the prominence of their schools. It is hoped that these results provide information that can aid administrators in making decisions about athletic programs and help them to further understand the role of athletics within higher education.

….

References

Avery, C., and C. Hoxby. 2004. Do and should financial aid decisions affect students’ college choices? In College choices: The new economics of choosing, attending, and completing college, edited by Caroline Hoxby. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 239–299.

Bremmer, D., and R. Kesselring. 1993. The advertising effect of university athletic success—A reappraisal of the evidence. Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 33:40–21.

Card, D., and A. Krueger. 2004. Would the elimination of affirmative action affect highly qualified minority applicants? Evidence from California and Texas. NBER Working Paper No. 10366.

Chapman, D. 1981. A model of student college choice. Journal of Higher Education 52:490–503.

Coughlin, C., and O. Erekson. 1984. An examination of contributions to support intercollegiate athletics. Southern Economic Journal 51:180–95.

Curs, B., and L. D. Singell. 2002. An analysis of the application and enrollment process for in-state and out-of-state students at a large public university. Economics of Education Review 21:111–24.

Fuller, W., C. Manski, and D. Wise. 1982. New evidence on the economic determinants of post secondary schooling choices. Journal of Human Resources 17:477–95.

Goidel, R., and J. Hamilton. 2006. Strengthening higher education through gridiron success? Public perceptions of the impact of national football championships on academic quality. Social Science Quarterly 87:851–62.

McCormick, R., and M. Tinsley. 1987. Athletics versus academics? Evidence from SAT scores. Journal of Political Economy 95:1103–16.

McEvoy, C. 2006. The impact of elite individual athletic performance on university applicants for admission in NCAA Division I-A football. The Sport Journal 9(1).

Mixon, F. 1995. Athletics versus academics? Rejoining the evidence from SAT scores. Education Economics 3:277–83.

Mixon, F., and Y. Hsing. 1994. The determinants of out-of-state enrollments in higher education: A Tobit analysis. Economics of Education Review 13:329–35.

Mixon, F., and R. Ressler. 1995. An empirical note on the impact of college athletics on tuition revenues. Applied Economics Letters 2:383–7.

Mixon, F., and L. Trevino. 2005. From kickoff to commencement: The positive role of intercollegiate athletics in higher education. Economics of Education Review 24:97–102.

Mixon, F., L. Trevino, and T. Minto. 2004. Touchdowns and test scores: Exploring the relationship between athletics and academics. Applied Economics Letters 11:421–4.

Murphy, R., and G. Trandel. 1994. The relation between a university’s football record and the size of its applicant pool. Economics of Education Review 13:265–70.

Pope, D., and J. Pope. 2007. Consideration set formation in the college choice process. Unpublished paper, The Wharton School and Virginia Tech.

Savoca, E. 1990. Another look at the demand for higher education: Measuring the price sensitivity of the decision to apply to college. Economics of Education Review 9:123–34.

Siegfried, J., and M. Getz. 2006. Where do the children of professors attend college? Economics of Education Review 25:201–10.

Tucker, I. 2004. A reexamination of the effect of big-time football and basketball success on graduation rates and alumni giving rates. Economics of Education Review 23:655–61.

Tucker, I. 2005. Big-time pigskin success. Journal of Sports Economics 6:222–9.

Tucker, I., and L. Amato. 1993. Does big-time success in football or basketball affect SAT scores? Economics of Education Review 12: 177–81.

Tucker, I., and L. Amato. 2006. A reinvestigation of the relationship between big-time basketball success and average SAT scores. Journal of Sports Economics 7:428–40.

Zimbalist, A. 1999. Unpaid professionals: Commercialism and conflict in big-time college sports. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Notes

1. For example, a history of the NCAA provided on the NCAA’s official web site states, “The 1905 college football season produced 18 deaths and 149 serious injuries, leading those in higher education to question the game’s place on their campuses” (http://www.ncaa.org/wps/portal). The 1905 season led to the establishment of the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States (IAAUS), which eventually became the NCAA in 1910.

2. Bill Thomas is a Republican congressman from California and previous chairman of the tax-writing House Ways and Means Committee. The full letter was printed in an article entitled “Congress’ Letter to the NCAA” on October 5, 2006, in USA Today.

3. A leading example of the anecdotal evidence has been dubbed “the Flutie effect,” named after the Boston College quarterback Doug Flutie, whose exciting football play and subsequent winning of the Heisman Trophy in 1984 allegedly increased applications at Boston College by 30% the following year. Furthermore, Zimbalist (1999) notes that Northwestern University’s applications jumped by 30% after they played in the 1995 Rose Bowl, and George Washington University’s applications rose by 23% after its basketball team advanced to the Sweet 16 in the 1993 NCAA basketball tournament.

4. The ACC, SEC, SWC, Big Ten, Big Eight, and PAC Ten conferences were typically considered the “major” conferences in college basketball and football at that time. Today the ACC, SEC, Big Ten, Big Twelve, Big East, PAC Ten, and independent Notre Dame are considered the major conferences/teams.

5. More detail about this literature is provided in the next section.

6. In Pope and Pope (2007), we use these data to also show that sports success has a differentiated impact on various demographic subgroups of students and to illustrate the limited awareness that high school students may have with regards to the utility of attending different colleges.

7. Reputation can be thought of as either academic reputation or as social/recreational reputation.

8. Other papers in this literature (as pointed out by a referee) include Mixon, Trevino, and Minto (2004), Tucker (2004, 2005), Mixon and Trevino (2005), Goidel and Hamilton (2006), McEvoy (2006), and Tucker and Amato (2006). These papers adopt similar identification strategies for estimating the quantity and quality effects as those described in Table 13.

9. Temporal variation typically enters the regression via a variable that reflects the aggregate sports success over the 10–15 years prior to the year of the school data.

10. See, for example, Steve Stecklow’s April 5, 1995, article in the Wall Street Journal entitled “Cheat Sheets: Colleges Inflate SATs and Graduation Rates in Popular Guidebooks.”

….

13. Forty-eight teams were invited in 1980, 1981, and 1982. In 1983, 52 teams were invited. In 1984, 53 teams were invited. Currently 65 teams are invited, but one of two teams is required to win an additional game before entering the round of 64.

….

15. We thank David Card, Alan Krueger, the Andrew Mellon Foundation, and the College Board for help in gaining access to this data set.

….

18. Less than 1% of students sent their scores to more than 14 schools.

….

20. Sending an SAT score to a school is not the same as applying to that school. However, it may be a good proxy. Card and Krueger (using the same SAT test-takers data set) tested the validity of using sent SAT scores as a proxy for applications. They compared the number of SAT scores that students of different ethnicities sent with admissions records from California and Texas and administrative data on the number of applications received by ethnicity. They conclude that “trends in the number of applicants to a particular campus are closely mirrored by trends in the number of students who send their SAT scores to that campus, and that use of the probability of sending SAT scores to a particular institution as a measure of the probability of applying to that institution would lead to relatively little attenuation bias” (2004, p. 18).

….

24. To put this quantity effect into perspective, the application elasticity of changes in the price of attending college found in the literature typically range from –.25 on the low end to –1.0 on the high end (see, e.g., Savoca 1990; Curs and Singell 2002). These elasticities suggest that tuition/financial aid would have to be adjusted somewhere in the range of 2–24% to obtain a similar increase in applications.

SCOREBOARDS VS. MORTARBOARDS: MAJOR DONOR BEHAVIOR AND INTERCOLLEGIATE ATHLETICS

Jeffrey L. Stinson and Dennis R. Howard

INTRODUCTION

A recent NCAA report indicated that charitable contributions to athletic departments at Division IA schools have more than doubled over the past decade … Despite the substantial growth, a number of fundamental questions regarding charitable contributions to athletic programs remain relatively unexplored:

1. Who gives to educational institutions in support of academic and/or athletic programs? Is it primarily non-alumni who contribute to intercollegiate athletics programs? Is it primarily alumni who contribute to academic programs?

2. Does the improved performance of intercollegiate athletic teams, specifically high profile sports including football and/or men’s and women’s basketball, affect both types of giving to the educational institution?

3. Does increased giving to athletics by alumni and non-alumni have a negative impact on charitable giving to educational programs at the same institution?

This study is based on an in-depth analysis of donor behavior at a major public university whose athletic teams compete at the Division IA level. The institution under study offers a unique window of opportunity for examining the extent to which improved team performance may impact both athletic and academic fund raising. Over the past decade, the university’s athletic teams, in particular football and men’s and women’s basketball, have achieved unparalleled success, moving from perennial middle of the pack status to regularly contending for conference and, occasionally, national championships.

A review of the literature suggests that formal hypothesis development regarding the basic questions addressed in this study is premature. Many of the assertions concerning donor behavior found in the literature lack credible empirical support, and others offer contradictory findings. The current study seeks to offer an empirical foundation for future hypothesis development and testing.

Research Question 1: Do Alumni Donors Give Primarily to Academics and Non-Alumni Donors Give Primarily to Athletics?

At Big-time U’s, a small percentage, usually in single digits, of alumni contribute to the school’s intercollegiate athletics program (a similarly low percentage donates to its educational programs). However, often the main contributors to athletic departments are boosters—rabid sports fans who, unlike alumni, never attended the institution and whose interest in it focuses almost exclusively on its college sports teams (Sperber 2000, p. 258).

In two books discussing the impact of “big-time intercollegiate athletics” on colleges and universities, Sperber (1990, 2000) commented extensively on donor behavior toward both academics and athletics. Sperber (1990) asserted that fewer than 2% of alumni contribute to their alma mater’s athletics program; the majority instead focused their giving on their school’s academic programs. Non-alumni, on the other hand, donated almost exclusively to the intercollegiate athletic program.

This distinction in giving behavior assumes alumni are less susceptible to fluctuations in giving with changes in athletic success, as “alumni giving is independent of college sports success or failure” (Sperber 2000, p. 256). Instead, alumni giving is driven by their academic relationship to the institution. Graduates are assumed to be proud of their degrees, and wish to repay the institution through their donations. Sperber argued that schools located at or near the top of U.S. News & World Report’s annual ranking of alumni giving at American colleges and Universities (as a percentage of alumni making a gift in the previous year) rankings tend to be known for their educational reputation as opposed to their athletic reputation. In contrast, schools with top college sports teams (Wisconsin, Michigan, and UCLA are cited), all have far lower rankings on the alumni-giving list.

The Identity Salience Model of Nonprofit Relationship Marketing Success offers one plausible explanation for this giving discrepancy (Arnett, German, & Hunt, 2003). Identity salience, a measure of the importance of an identity to self, is proposed to mediate the relationship between relationship-inducing factors and donating behavior. In the case of alumni donors, to the extent that such relationship-inducing factors as participation and organizational prestige are centered around the academic mission of the institution, as Sperber argues is the case with the U.S. News and World Report top schools, one would expect a more salient donor identity with academics and more charitable giving directed at academic programs.

A recent study offered empirical support for the notion that alumni giving is more heavily influenced by academic-related factors than athletic success. Rhoads and Gerking’s (2000) 10-year study of 87 NCAA Division IA institutions found that academic tradition and status had a far greater impact on alumni giving than the performance of athletic teams. Carnegie level I institutions, which represent the highest level of research institution in the Carnegie Foundation’s classification system, were found to receive 41% more support per student than other institutions. Additionally, a 100-point increase in incoming student average SAT scores correlated with 51% more alumni support per student.

Brown (1991) in a study of Ball State University alumni found that the academic reputation of the institution was a primary determinant of donor behavior. A substantial majority (61%) of the alumni donors equated the university’s reputation with the quality of its faculty and educational programs. Intercollegiate athletics were insignificant in determining the donor behavior of this group.

Although some evidence supports Sperber’s view that alumni donations are driven by academics rather than athletics, available literature (Rhoads & Gerking 2000, Brown 1991) does not substantiate his assertion that non-alumni (sometimes referred to as boosters) give exclusively to athletics. No empirical evidence was found to support this claim. In addition, research on institutional giving to date has not recognized that alumni and non-alumni can direct a portion of their institutional gifts to both academics and athletics. It is conceivable that the pattern of institutional giving may be more complex than the simple either/or differentiation suggested in previous studies. Therefore, this research will examine the donor behavior of both alumni and non-alumni, and the extent to which each of these donor groups split their annual donations across athletics and academics.

Research Question 2: Does Winning Have a Significant Impact on Alumni Giving?

Of the three research questions examined in this study, the relationship between winning and alumni giving has received the most attention. Despite this, there is still no clear answer to how athletic success impacts alumni academic giving. The many studies conducted on this topic often contradict each other and taken together produce equivocal results as to whether successful intercollegiate athletic teams influence alumni to donate more to their alma maters.

The aforementioned Rhoads and Gerking (2000) study also examined the impact of year-to-year changes in athletic success on total giving by alumni. Significant increases in alumni donations were associated with increased athletic success. Contributions were measured as dollars per student currently enrolled to control for institution size. A football bowl game win was found to raise alumni contributions per student by 7.3%, while alumni contributions fell 13.6% when a basketball team was placed on probation.

Grimes and Chressanthis (1994) also offered support for the positive impact of athletic success. The authors studied the giving patterns of Mississippi State University alumni from 1962-1991, and found that total contributions were positively related to the overall winning percentage of major (basketball, football, and baseball) intercollegiate athletic teams. The researchers found that each one percent increase in overall winning percentage of the three teams was correlated with a substantial, significant increase in total giving to the institution.

In contrast, several studies have concluded that no significant relationship exists between athletic success and giving to the institution. As part of a comprehensive study of higher education, Shulman and Bowen (2001) examined giving data from eight private, academically selective colleges and universities that compete athletically at the NCAA Division IA level. Athletic success was found to be an insignificant factor in alumni giving. However, it is quite possible that the findings were a function of the elite academic nature of the schools included in Shulman and Bowen’s study. All eight schools were among the most prestigious higher education institutions in the U.S., including several Ivy League schools, Stanford, and Northwestern. Each of these schools has higher levels of academic than athletics prestige. Some of the schools offer only academic scholarships. Consistent with the Arnett et al.’s (2003) Identity Salience Model, we expect donor behavior to follow the institutional focus on academics at these institutions and donors to direct their dollars to maintain the academic prestige of the university.

Two earlier studies also support the general lack of relationship between athletic success and charitable behavior among alumni. In a study of the annual campaigns of 135 schools, Sigelman and Carter (1979) found no relationship between athletic success and increased alumni giving. Gaski and Etzel (1984) examined 99 NCAA Division I institutions for donor behavior by alumni status (alumni vs. non-alumni) and fund type (annual fund vs. other), concluding that there was no evidence of the impact of athletic success on overall giving. While the influence of winning on alumni donor behavior is not clear, Gaski and Etzel (1984) remains the only study to date that has examined athletic team performance on the donor behavior of non-alumni.

The current study provides an empirical basis for examining whether winning has a differential influence on alumni and non-alumni and how such differences manifest themselves in the giving behavior of the two groups. Are non-alums, with few or no academic ties to the university, more sensitive to the fortunes of the institution’s athletic teams? Does winning encourage greater overall financial support to just the institution’s athletic program or does athletic success also spur more giving to academic programs? The intent of this study is to examine these questions and provide a deeper understanding of the relationship between intercollegiate athletic success and donor behavior.

Research Question 3: Does Athletics Giving Undermine Giving to Academics?

Sperber (2000) asserted that athletic departments “actively undermine efforts to raise money from alumni for educational programs” (p. 259). Labeling this the “college-sports-equals-alumni-giving myth,” he noted an increasing focus by athletic departments on wealthy alumni to support larger programs and facilities. He contended that after securing a major gift for a new athletic facility from a particular alumnus it would be unlikely for that same individual to donate a major gift to an academic unit of the institution.

Additionally, Sperber (2000) suggested that the highly publicized athletic programs of most Division IA institutions could result in alumni cutting their gifts in times of negative publicity. He offered the case of Southern Methodist University where alumni giving to academics dropped following the football team receiving the death penalty—the severest of NCAA sanctions that completely shuts down a program for a period of time—in the 1980s. Furthermore, during the pre-scandal winning years, alumni giving to academics did not increase.

The opposite side of the spectrum is offered by Shulman and Bowen (2001), who write, “There is certainly no indication in the data we have collected that private giving to athletics today is so substantial (in either the number of donors or the size of the average gift) that it is likely to detract in any substantial way from fundraising for broader educational purposes” (Shulman & Bowen, 2001, p. 215).

As the quote indicates, Shulman and Bowen (2001) found no significant impact of giving to athletic programs on giving to academic programs at the eight Division IA schools included in their sample. The authors classified alumni gifts as either athletic or academic. There was no significant reduction in giving to academics associated with giving to athletics; thus, the authors concluded that no relationship between the two types of giving exists.

However, their findings might be a function of the very narrow range of schools in the sample. All eight schools included in their analysis are heavily endowed, academically elite, private institutions, leading the authors to note “the practices and leading issues in the Division IA schools are qualitatively different from those of the other institutions [in this study]” (p. xxiv). If the assumption that alumni donors give predominantly to academic programs is true, the schools in this sample may be less susceptible to any decline in academic giving as athletic contributions rise. It remains untested whether such a situation would hold at a public institution with much lower levels of alumni support. Yet these factors seem to contribute to the authors conclusion that “[i]t would be comforting to assume that the apparent lack of competition for gifts between athletics and other institutional purposes would continue into the future. Unfortunately, we do not think such confidence is warranted” (Shulman & Bowen, 2001, pg. 38).

Finally, one earlier study by McCormick and Tinsley (1990) found that giving to athletics had a positive impact on academic giving, estimating that a 10% increase in giving to athletics was associated with a 5% increase in academic giving. The authors examined alumni giving data at Clemson University, in South Carolina, for the time period 1979–1983.

As with the impact of athletic success on donor behavior, the limited empirical evidence considering the impact of donations to athletics on academic giving is less than clear. The current study seeks to directly examine the relationship between the two types of giving for both alumni and non-alumni.

AN EXAMINATION OF UNIVERSITY OF OREGON DONORS

The sample for this study includes all donors making gifts of $1000 or more between 1994 and 2002 to the Annual Giving Program at the University of Oregon. The university conducted a capital campaign ending in 1998. However, large, non-recurrent capital gifts (both athletic and academic) donated as part of the campaign were not classified as annual gifts and, therefore, not included as part of the database used in this study.

A minimum $1000 gift to the Annual Giving Program entitles the donor to membership in the President’s Club and represents the first category of major donation at the University of Oregon. The number of major donors has grown from 779 in 1994 to 2,309 in 2002. In addition, major donors were found not only to give more but to also give more consistently than those making smaller annual contributions. Major donors had a significantly greater propensity to make recurrent annual gifts than minor donors, making this subset of donors a more relevant sample for examining the research questions under consideration in this study. Furthermore, while major donors constitute only 4.3% of the total number making gifts to the University, these donors contribute 72% of the total charitable revenues.

The entire giving history of each donor making an annual gift of $1000 or more during the selected time frame was extracted from the University’s Benefactor database, compiled and managed by the University of Oregon Foundation, which is the academic fundraising body at the university. Each gift was subsequently coded as made by an alumnus or non-alumnus, and donations were divided into three giving areas.

• Athletic gifts represent gifts directed towards the athletic department, including all gifts made to the athletic fundraising entity, the Duck Athletic Fund.

• Academic gifts represent all gifts directed towards an academic program or unit, as well as all undirected gifts that may be used at the discretion of the university president.

• Other gifts are those donations directed at a non-academic, non-athletic unit of the University. Examples include the university theatre, the art museum and the Oregon Bach Festival.

Fiscal year 1994 was selected as the starting point for analysis as it represented the first year for which reliable giving data on all donors to the University of Oregon Foundation was available.

The University of Oregon is a mid-size public research institution that sponsors 15 National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I varsity athletic programs. Oregon offers a unique and interesting opportunity to examine the relationship between athletic success, athletic fundraising, and academic fundraising. The combination of unprecedented athletic success and major athletic fundraising efforts during the sampling period provides a rare window in which to examine the research questions of interest. No major changes in the university’s academic program (i.e., change in Carnegie classification) occurred during the time period considered in this study, creating an unintended natural experimental condition in which to examine the potential influence of athletic-related success on academic fundraising.

The 1994 season began an unprecedented run of success for the Oregon football program. The team played in the Rose Bowl for the first time in 40 years in 1995. Over the next seven seasons, the Oregon football team compiled a 69 and 27 record, winning two conference championships and playing in five bowl games. In 2001, the Oregon football team compiled an 11 and 1 record and ended the season ranked #2 in the nation. In 2002, the athletic department completed a $90-million expansion of Autzen Stadium. In the ten years prior to 1994, the Oregon football team had only four winning seasons, compiling a record of 58 wins and 57 losses. In 1995, the men’s basketball team advanced to the NCAA Championship tournament for the first time in 34 years. From 1995–96 through 2001–02, the Oregon basketball team played in four post-season tournaments, advancing to the National Invitational Tournament Final Four in 1999 and to the NCAA Elite Eight in 2002. A campaign to fund construction of a new basketball arena was announced in early 2003.

The fortunate circumstance of having detailed donor records available at the onset of the athletic teams’ run of success provided a unique opportunity for directly examining the relationship between team performance and donor behavior related to both academic and athletic giving. As noted by Grimes and Chressanthis (1994) and Brooker and Klastorin (1981), while the focus on a single institution may result in the loss of reliability in generalizing the results, universities that share many common characteristics are more likely to experience similar patterns in the receipt of charitable donations. Stake (1983) argued that when there is a need to generalize only to similar cases as opposed to a population of cases, a single-institution study is an acceptable form of inquiry. The University of Oregon shares many characteristics with other public research institutions supporting NCAA Division I athletic programs, and while future research should include additional institutions, only the data from one school were considered in this study. Therefore, while the specific results of this study may not be generalizable to other institutions, similar findings at similar institutions would not be surprising.

Research Question 1

… [T]he data indicate that both alumni and non-alumni give to both academics and athletics, though, clearly, there are significant differences in the giving behavior of the two groups. In all but two years (1994, 1996), alumni made significantly higher gifts to academics than non-alumni, and in every year since 1994, alumni allocated a significantly larger portion of their total gift to academics than non-alumni. On the other hand, non-alumni allocated a significantly higher percentage of their total gift to athletics every sample year. However, in terms of actual average gift amount, non-alums only made a significantly higher gift to athletics in the final year of the sample (2002). Thus, the assumption that alumni give primarily to academic programs while non-alumni give primarily to intercollegiate athletic programs partially holds. Alumni do give predominantly more to academics, but they also donate large amounts, both in terms of average gift amount and percent of total gift, to intercollegiate athletics.

Further analysis shows that in the most recent year, 38.7% of alumni allocated their entire gift to the athletics program and 69.5% of alumni allocated at least a portion of their gift to athletics, suggesting higher alumni participation in athletic fundraising at Oregon than the 2% asserted by Sperber (2000). Over 36% of non-alumni in 2002 allocated at least a portion of their gift to a non-athletic program. Together, these results clearly demonstrate that both alumni and non-alumni give to both academics and athletic programs, and that a simple alumni/non-alumni dichotomy is not an adequate explanation of donor behavior.

The data were then analyzed by allocation groups …: a group allocating their entire gift to academics, a group allocating their entire gift to athletics, and a group making a split gift (both athletic and academic). No statistical differences were found between alumni and non-alumni allocating their entire gift to athletics or academics. It appears that only in the case of split gifts is the alumni/non-alumni distinction significant in donor behavior.

Research Question 2

In this era of increasing athletic success at the University of Oregon, more alumni give more to athletics, suggesting that alumni giving may indeed be influenced by athletic success. In 1994, 58.5% of alumni donors in the sample allocated at least a portion of their gift to the intercollegiate athletics program. This percentage has risen steadily to the 69.5% of alumni donors in the sample making a gift to athletics in 2002. In terms of real donors, 297 alumni donors donated to athletics in 1994; 962 alumni made a gift to athletics in 2002. This was in a time period where growth in total alumni donors making annual gifts of $1000 or more increased by 877 donors, suggesting that virtually every new alumni donor at this level allocated at least a portion of their gift to athletics, in addition to some previous donors who began allocating some of their gift to athletics. Finally, the average donation to athletics by this group grew from $1010.11 in 1994 to $1773.55 in 2002. In almost every way, alumni giving to athletics has increased with an associated increase in success by the high profile intercollegiate athletic teams at the University of Oregon.

While more subtle, athletic success may also be influencing academic giving by alumni…. The percentage of alumni donors making an academic gift has fallen from 73.2% to 61.3% since 1994. The number of alumni donors making gifts of $1,000 or more to academics has increased during the time period from 372 to 863, an increase of 491. However, this lags far behind the increase of 666 alumni donors making a major gift to the athletic department during the same time period. Still, in terms of average academic gift amount, alumni have been relatively stable, with average gifts ranging from $1427.27 to $1710.00. These data suggest a possible neutral to negative influence of athletic success on academic giving by alumni. Either way, it is clear athletic success has not had a strong positive impact on alumni giving to academic programs.

Research Question 3

Thus, we turn to an examination of the relationship between giving to athletic programs and giving to academic programs. The data … provide strong support for the assumption that giving to athletics undermines giving to academics, particularly for non-alumni. Over the time period considered, the average academic gift by non-alumni has fallen significantly, while the average gift to athletics has significantly increased. Since 1994, the average academic gift by a non-alum has fallen $671.35, while the average non-alum gift to athletics has increased $962.88. While the effects of winning athletic seasons on alumni donations are not quite as dramatic, the trends suggest that amounts donated to athletics are negatively associated with alumni decisions related to academic giving. There has been no significant change in alumni giving to academics in terms of total dollars donated. However, alumni have significantly increased their giving to athletics, and now donate a significantly larger percentage of their gift to the athletic department. In 1994, 40.4% of the average alum gift was targeted to intercollegiate athletics. By 2002, alums donated 56.7% of their gift to athletics.

It is clear that proportional giving by alums increasingly favors athletics …. Fiscal year 2002 saw an increase in total dollars donated by alumni of over $840,000. Over 81% of this incremental revenue was directed toward the intercollegiate athletic department. This resembles the allocation of incremental revenue by non-alumni, who allocated 83.9% of their additional giving to athletics. For every $100 of new revenue raised from major donors by the University of Oregon, over 80% is being directed to the athletic department.

Even with the large increases in numbers of total donors since 1994, academic giving struggles to remain stable while donations to athletics experience huge growth. In three out of the past five years (1998, 2000, 2001), the total dollars donated to academics by non-alumni has fallen despite annual increases in the number of non-alumni donors. Total dollars donated to academics by alumni fell in only one year (2000), again despite an increase in the total number of donors. This suggests new donors are not making academic gifts, and current donors are shifting dollars from academic giving to donations directed to the athletic program. Additionally, as discussed above, proportional giving by alumni is predominantly directed to the athletic program. If these trends continue, total academic giving will fall for both alumni and non-alumni despite continued increases in the total numbers of both types of donors.

Further analysis examined the number of donors allocating their entire gift to either intercollegiate athletics or academics …. Since 1994, the percentage of alumni donors allocating their entire gift to athletics has increased from 26.8% to 38.7%. During that same time period, the percentage of alumni allocating their entire gift to academics has fallen from 41.5% to 30.5%. Together, these findings are most likely the result of one or both of the following effects: some alumni are reducing or eliminating gifts to academics while increasing gifts to athletics, and/or some previous academic donors have stopped contributing and new alumni donors are making more gifts to athletics than academics. The pattern is similar for non-alumni, where the percentage allocating their entire gift to athletics has risen from 42.1% to 63.5%, and the corresponding percentage of non-alumni donors allocating their entire gift to academics has fallen from 26.6% to 12.8%. Increased giving to athletics is negatively associated with the academic giving of both alumni and non-alumni at the University of Oregon.

Again, the data were further analyzed by reducing donors to a group donating their entire gift to athletics, a group donating their entire gift to academics and a group splitting their gift. As discussed above, for both alumni and non-alumni the percentage of donors allocating their entire gift to athletics has increased while the percentage allocating their entire gift to academics has decreased. The percentage of alumni split-gift donors has remained relatively stable. However, the percentage of non-alumni split-gift donors has fallen to less than 25%, suggesting that non-alumni donors making a first gift to athletics are not subsequently making gifts to academics.

Furthermore, alumni split-gift donors are favoring athletics in the allocation of their split gift …. The percentage of gift allocated by alumni split-gift donors to athletics has risen from 38.1% to 52.9% of the total gift, while the percentage allocated to academics has fallen from 55.4% to 31.7%. In terms of actual dollars, alumni split-gift donors made an average gift to athletics of $1183.33 in 1994. That amount rose to an average gift of $2237.66 in 2002. Academic gifts, on the other hand, fell from $1721.89 in 1994 to $1340.98 in 2002. Again, the data show an increase in giving to athletics associated with reduced academic giving—even by alumni.

The overwhelming conclusion that can be drawn from this data is, at least at the University of Oregon, the increasing success of athletics-related fundraising has been and is associated with reduced giving to the academic mission of the institution. Perhaps most troubling is the possible negative influence on alumni giving. While lagging behind the significant changes in non-alumni donor behavior, all of the trends suggest that alumni giving behavior is moving in a similar direction—toward athletics.

With respect to the three research questions, the following conclusions are offered:

• Both alumni and non-alumni make gifts to both athletic and academic programs. Nearly 70% of alumni donors examined made a gift to the intercollegiate athletic department, casting doubt on the assertion that only a small percentage of alumni make athletics related gifts.

• At least contextually, there is evidence that a winning program may significantly influence the giving behavior of alumni. Alumni appear to give significantly more to the athletics program as program success increases. Alumni academic giving may not be influenced as strongly, though there are some indications that athletic success may encourage a reallocation of donors’ institutional contributions with a discernable shift toward athletics.

• Both alumni and non-alumni show an increasing preference toward directing their gifts to the intercollegiate athletics department - at the expense of the donations to academic programs. Sperber’s (2000) assertion that giving to athletics undermines academic giving is strongly supported.

IMPLICATIONS

The current study yields several important implications for future research. Issues surrounding donor motivations and institutional cultivation strategies will be critical to both a conceptual and practical understanding of institutional fundraising.

Most studies investigating the motives of donors to athletic programs have found at least some component of tangible benefit to the donor as a main determinant of the donor’s behavior. Most recently, Mahony, Gladden, and Funk (2003) and Gladden, Mahony, and Apostolopoulou (2003) identify priority seating for football and basketball as the most important motive for an athletic department contribution, overwhelming any social motives. Earlier research on the Athletics Contributions Questionnaire Revised Edition II (Staurowsky, Parkhouse, & Sachs, 1996) and the Motivation of Athletics Donors (Verner, Hecht, & Fansler, 1998) both revealed a social motive for giving, defined by Staurowsky, Parkhouse, and Sachs as “the social interaction that occurs for people who follow teams and attend games” (pg. 270). However, both studies included one or more factors that could be considered tangible in nature. The availability of tangible benefit to the potential donor may in fact be pulling donors to make gifts to athletics instead of academics, where tangible benefit often requires more significant giving. A focus on tangible benefits offers one possible explanation for our findings. In exchange for a $1000 gift to the University of Oregon athletic department, a donor receives access to preferential seating at athletic events, preferred parking, and invitations to athletics-related social events. On the other hand, a $1000 gift to an academic unit, while entitling the donor to recognition as a member of the President’s Club is accompanied by little if any tangible benefit. Therefore, the exchange, from the donor’s perspective, may be seen as more valuable for a gift to athletics than to academics. Interestingly, athletic donors in the Gladden et al. (2003) study listed both a desire to help student-athletes in the form of scholarships and educational opportunity, and supporting the university as a whole in the top five reasons for making a donation. Future research should examine both whether donors are aware of any separation in athletic versus academic giving, and if donor behavior would change if such distinctions were more salient. It is quite plausible that donors view a donation to the athletic department as the best of both worlds: the donor is helping students and the university while at the same time receiving significant personal benefit. Such a view would help explain the shifts to athletic donations observed at the University of Oregon.

Furthermore, it is possible that our results begin to offer clarification to the model of individual donor behavior proposed by Brady et al. (2002). The authors propose a joint effects model of donor behavior to higher education institutions, whereby donors use both a services model focused on service value and satisfaction, and a philanthropic effects model centered on organizational identification, perceived need, and philanthropic predisposition in forming intent to give. However, no clarification of when their services model or philanthropic effects model would predominate over the other in explaining donor behavior was offered. It seems plausible, if not likely, that donations made in exchange for tangible donor benefit would be more subject to the services model than to the philanthropic effects model. Such reasoning would be consistent with our results of increased athletic giving associated with increased athletic winning, and with earlier studies indicating a positive relationship between winning and giving (Rhoads & Gerking, 2000; Grimes & Chressanthis, 1994). Academic giving, on the other hand, appears to be more dominated by the philanthropic effects model, suggesting these donations may be less susceptible to the fluctuations in athletic success. Again, this argument would be consistent with the alumni academic giving at the University of Oregon.

In an environment of heavy competition for donors and their gifts (Greenfield, 2002), the ability of athletic departments to offer a valuable tangible benefit in exchange for a gift may attract donors who would otherwise make an academic gift. This suggests that the organizational structure of the institution’s development department may be an important factor. Where athletic and academic development officers have differing reporting structures, competition may more easily ensue, allowing athletics to capitalize on the more valuable tangible benefits typically available to athletics donors than to academic donors. Where both athletics and academic fundraisers report through the same lines, more cooperation would be expected, perhaps minimizing the negative impact to academic giving, either by offering similar tangible benefit for academic gifts, or by controlling the extent to which tangible benefits are offered for athletics gifts.

Consistent with the above argument is a need to better understand the role of athletics fundraising in recruiting donors to the institution. Two commonly prevailing views of the benefit of athletic fundraising are that it brings new donors to the institution, and that it captures funds that would not have been donated to the institution through other mechanisms (i.e., academic giving). The evidence at the University of Oregon suggests that while athletics-based fundraising has been successful at recruiting new institutional donors, such recruitment is coming at a price to academic giving. Our data suggest the institution is not successfully transitioning new donors from athletics only into split donors (academics and athletics). Future research needs to more clearly examine if, when and how this transition takes place, both from a donor decision-making view, and from an institutional cultivation view. The literature on social identification and identity salience may be relevant, with a key question being: Is it possible to move from a state of identification with a specific team or department, to a broader relationship with the institution as a whole? To the extent that organizational identification and identity salience drive donor behavior (Arnett et al, 2003; Mael & Ashforth, 1992), the nature and direction of identification may be crucial determinants in cultivating athletic donors to also support the academic mission of the institution.

CONCLUSION

While the data considered in this study came from only one institution, and therefore lack generalizability, we would expect to identify similar trends at other, similar institutions across the U.S. The results of this single-institution study indicate the need for future research that includes a broader cross-section of NCAA IA institutions to clarify the impact of intercollegiate athletics and athletics-related giving on academic giving to the sponsoring institution.

Future work needs to focus on the differing decision processes and motives for giving by alumni and non-alumni, as well as differences between athletic, academic, and split-gift donors. The data considered in this study are entirely historical, and while valuable in identifying trends in giving behavior, they provide little insight into donor decision processes and motivations. Additionally, this work should be expanded and included in research on the impact of successful intercollegiate athletic teams on donor behavior. The role of athletic success in influencing giving behavior needs to be further clarified, considering the susceptibility of different groups to changing gift patterns based on athletic team success. Finally, this research only included donors making annual gifts of $1,000 more. Future research should investigate whether lower level donors exhibit similar or different giving behaviors.

References

Arnett, D. B., German, S. D., & Hunt, S. D. (2003). The identity salience model of relationship marketing success: The case of nonprofit marketing. Journal of Marketing, 67, 89–105.

Brady, M. K., Noble, C. H., Utter, D. J., & Smith, G. E. (2002). How to give and receive: An exploratory study of charitable hybrids. Psychology & Marketing, 19, 919–944.

Brooker, G., & Klastorin, T. D. (1981). To the victors belong the spoils? College athletics and alumni giving. Social Science Quarteriy, 62, 744–50.

Brown, I. D. (1991). Targeting university alumni segments that donate for non-athletic reasons. Journal of Professional Service Marketing, 7, 89–97.

Fulks, D. L. (2000). Revenues and expenses of Division I and II intercollegiate athletics programs: Financial trends and relationships—1999, Overland Park, KS: The National Collegiate Athletic Association.

Gaski, I. E., Etzel, M. J. (1984). Collegiate athletic success and alumni generosity: Dispelling the myth. Social Behavior and Personality, 12, 29–38.

Gladden, J. M., Mahony, D. F., & Apostolopoulou, A. (2003). Toward a better understanding of college athletic donors: What are the primary motives? Unpublished manuscript.

Greenfield, I. M. (2002). The nonprofit handbook: Fundraising, 3rd Edition, New York: Wiley.

Grimes, P. W., & Chressanthis, G.A. (1994). Alumni contributions to academics: The role of intercollegiate sports and NCAA sanctions. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 53, 27–41.

Mael, F., & Ashforth, B. E. (1992). Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13, 103–123.

Mahony, D. F., Gladden, J. M., & Funk, D. C. (2003). Examining athletic donors at NCAA Division I institutions. International Sports Journal, 7(1), 9–27.

McCormick, R. E., & Tinsley, M. (1990). Athletics and academics: A model of university contributions. In B.L. Goff & R.D. Tollison (Eds.), Sportometics (pp. 193–206). College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press.

Rhoads, T. A., & Gerking, S. (2000). Educational contributions, academic quality and athletic success. Contemporary Economic Policy, 18, 248–59.

Shulman, J. L., & Bowen, W. G. (2001). The game of life. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Shulman, J. L., & Bowen, W. G. (2001). The misfortunes of collegiate athletics. Case Currents, (27), 34–41.

Sigelman, L., & Carter, R. (1979). Win one for the giver? Alumni giving and big-time college sports. Social Science Quarterly, 60, 284–94.

Sperber, M. (1990). College sports inc. New York: Henry Holt.

Sperber, M. (2000). Beer and circus: The impact of big-time college sports on undergraduate education. New York: Henry Holt.

Stake, R.E. (1983). The case study method in social inquiry. In G.F. Madaus, M. Scriven, & D.L. Stuffelbeam (Eds.), Evaluation Models (pp. 279–286). Boston: Kluwer-Nijhoff Publishing.

Staurowsky, E. J., Parkhouse, B., & Sachs, M. (1996). Developing an instrument to measure athletic donor behavior and motivation. Journal of Sport Management, 10, 262–277.

Verner, M. E., Hecht, J. B., & Fransler, A. G. (1998). Validating an instrument to assess the motivation of athletic donors. Journal of Sport Management, 12, 123–137.

EMPHASIS ON INTERCOLLEGIATE ATHLETICS

THE IMPACT OF RECLASSIFICATION FROM DIVISION II TO I-AA AND FROM DIVISION I-AA TO I-A ON NCAA MEMBER INSTITUTIONS FROM 1993 TO 2003

INTRODUCTION

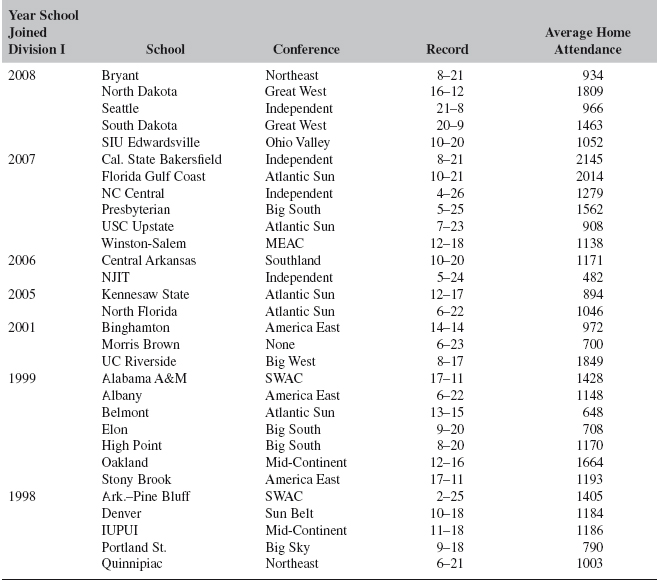

Purpose of Study