Chapter SEVENTEEN

INTRODUCTION

At the heart of the push for reforming collegiate sports is changing views of amateurism. As the readings that follow highlight, for most of the time that organized collegiate sports have existed, Americans have believed that there should be a class of athletes that participate in sports for the glory of the games alone. Even as the Olympic Games have moved away from this view, collegiate sports, under the governance of the NCAA, continue to hold fast, as the readings in this chapter highlight.

The excerpt from Kenneth L. Shropshire’s “Legislation for the Glory of Sport: Amateurism and Compensation” provides a historic overview of amateurism and the mythology and misconceptions associated with its lofty status. The article briefly traces the history that provides the foundation for the lingering beliefs of the righteousness of what are arguably outdated concepts of amateurism. Once the reality of amateurism is grasped, the important question becomes whether any reforms recognizing this reality will improve college sports.

The next excerpt, from Peter Goplerud III, provides an examination of the possibilities of “pay for play”; that is, paying student-athletes based on their athletic abilities. Christopher A. Callanan’s “Advice for the Next Jeremy Bloom: An Elite Athlete’s Guide to NCAA Amateurism Regulations” discusses the issue of athlete compensation by examining the case of a unique two-sport athlete.

The chapter concludes with three selections focused on reform in collegiate sports. The first is an excerpt from James L. Shulman and William G. Bowen’s The Game of Life. The piece focuses on the findings of their extensive study of the role of athletics in America’s colleges and universities and, particularly, insight on the participating athletes. The next selection is part of a report from The Knight Foundation Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics entitled “A Call to Action: Reconnecting College Sports and Higher Education.” This document, published in June 2001, is probably the best-known effort focused on the reform of collegiate sports. Many individuals believe that the Knight Commission’s ongoing efforts led to college presidents taking greater control of their athletic programs. The final excerpt is the Executive Summary from a 2009 Knight Commission report. The focus of this excerpt is on cost containment by university presidents in the Football Bowl Subdivision.

LEGISLATION FOR THE GLORY OF SPORT: AMATEURISM AND COMPENSATION

Kenneth L. Shropshire

….

B. ORIGIN OF THE RULES AGAINST COMPENSATION

1. Ancient Greeks

A common misconception held by many people today is that the foundation of collegiate amateurism had its genesis in the Olympic model of the ancient Greeks…. The “myth” of ancient amateurism held that there was some society, presumably the Greeks, that took part in sport solely for the associated glory while receiving no compensation for either participating or winning.10 In his book, The Olympic Myth of Greek Amateur Athletics,11 classicist David C. Young reported finding “no mention of amateurism in Greek sources, no reference to amateur athletes, and no evidence that the concept of ‘amateurism’ was even known in antiquity. The truth is that ‘amateur’ is one thing for which the ancient Greeks never even had a word.”12 Young further traces the various levels of compensation that were awarded in these ancient times including a monstrous prize in one event that was the equivalent of ten years worth of wages.13

The absence of compensation was not an essential element of Greek athletics.14 Specifically, the ancient Greeks “had no known restrictions on granting awards to athletes.”15 Many athletes were generously rewarded. Professor Young asserts that the only real disagreement among classical scholars is not whether payments were made to the athletes but only when such payments began.

The myth concerning ancient Greek athletics was apparently developed and perpetuated by the very same individuals that would ultimately benefit from the implementation of such a system.16 The scholars most often cited for espousing these views of Greek amateurism were those who sought to promote an athletic system they supported as being derived from ancient precedent.17 In his work, Professor Young systematically proves these theories false by countering with direct evidence and an analysis of the motivation for presenting inaccurate information. Similar faults by other scholars led to the inevitable development of fallacious cross-citations with each relying upon the other for authority.18 One scholar is believed to have actually created a detailed account of an ancient Greek athlete which Professor Young concluded was a “sham” and “outright historical fiction.”19 The reasoning behind such deliberate falsehoods was apparently designed to serve as “a moral lesson to modern man.”20

In simplest terms, these scholars were part of a justification process for an elite British athletic system destined to find its way into American collegiate athletics. “They represent examples of a far-flung and amazingly successful deception, a kind of historical hoax, in which scholar[s] joined hands with sportsm[e]n and administrator[s] so as to mislead the public and influence modern sporting life.”21 With amateurism widely proclaimed by the scholars of the day, the natural tendency was for non-scholars to join in and heed the cry as well.

The leading voice in the United States espousing the strict segregation of pay and amateurism was Avery Brundage, former President of both the United States Olympic Committee (USOC) and the International Olympic Committee (IOC).22 Brundage believed that the ancient Olympic Games, which for centuries blossomed as amateur competition, eventually degenerated as excesses and abuses developed attributable to professionalism.23 “What was originally fun, recreation, a diversion, and a pastime became a business…. The Games … lost their purity and high idealism, and were finally abolished…. Sport must be for sport’s sake.”24 Brundage was firmly against amateurs receiving any remuneration, justifying his belief upon the Greek amateur athletic fallacy. Brundage took extraordinary action during his tenure as president of the USOC and the IOC to ensure such a prohibition….

Professor Young and other like-minded scholars contend that the development of the present day system of collegiate amateurism is not modeled after the ancient Greeks. Rather, today’s amateurism is a direct descendant of the Avery Brundages of the world and is actually much more reflective of the practices developed in Victorian England than those originated in ancient Greece.

2. England

In 1866, the Amateur Athletic Club of England published a definition of the term “amateur.”26 Although the term had been in use for many years, this was, perhaps, the first official definition of the word. The definition which was provided by that particular sports organization required an amateur to be one who had never engaged in open competition for money or prizes, never taught athletics as a profession, and one who was not a “mechanic, artisan or laborer.”27

The Amateur Athletic Club of England was established to give English gentlemen the opportunity to compete against each other without having to involve and compete against professionals.28 However, the term “professional” in Victorian England did not merely connote one who engaged in athletics for profit, but was primarily indicative of one’s social class.29 It was the dominant view in the latter half of the nineteenth century that not only were those who competed for money basically inferior in nature, but that they were “also a person of questionable character.”30 The social distinction of amateurism, attributable to the prevailing aristocratic attitude at the time, provided the incentive for victory. “When an amateur lost a contest to a working man he lost more than the race… He lost his identity… His life’s premise disappeared; namely that he was innately superior to the working man in all ways.”31 Thus, concepts of British amateurism developed along class lines, and were reinforced by the “mechanics clauses” that existed in amateur definitions. These clauses typically prevented mechanics, artisans, and laborers from participation in amateur sport. The reasoning behind the “mechanics clause” was the belief that the use of muscles as part of one’s employment offered an unfair competitive advantage.32 Eventually, under the guise of bringing order to athletic competition, private athletic clubs were formed that effectively restricted competition “on the basis of ability and social position” and not on the basis of money.33 Over the years this distinction has been used to identify those athletes who are ineligible for amateur competition, because their ability to support themselves based solely on their athletic prowess has given them a special competitive advantage.34 It is from these antiquated rules that the modern eligibility rules of the NCAA evolved. Any remaining negative connotations regarding professionalism owe their continued existence to these distinctions.

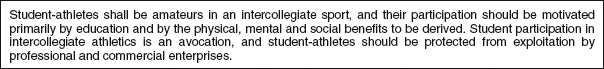

Figure 1 NCAA Constitution, Article 2.9—The Principle of Amateurism

Source: 2009–2010 NCAA Division I Manual, p. 4. © National Collegiate Athletic Association. 2008–2010. All rights reserved.

![]()

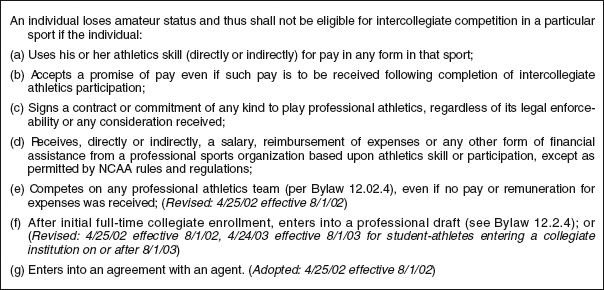

Figure 2 NCAA Bylaw 12.01.1—Eligibility for Intercollegiate Athletics

Source: 2009–2010 NCAA Division I Manual, p. 61. © National Collegiate Athletic Association. 2008–2010. All rights reserved.

The amateur/professional dilemma confronting today’s American universities is based on the presumption that if a college competes at a purely amateur level it will lose prestige and revenue, as it loses contests. However, open acknowledgement of the adoption of professional athleticism would result in a loss of respectability for the university as a bastion of academia. The present solution to this dilemma has been for collegiate athletic departments to “claim amateurism to the world, while in fact accepting a professional mode of operation.”35

Two sports, baseball and rowing, were the first to entertain the questions of professionalism versus amateurism in the United States. Initially, the norm for organized sports in this country was professionalism. Baseball was played at semiprofessional levels as early as 1860, and the first professional team, the Cincinnati Red Stockings, was formed in 1868.36 The first amateur organization, the New York Athletic Club, was established in the United States in 1868.37

In 1909, the NCAA (which had successfully evolved from the Intercollegiate Athletic Association, established in 1905) recommended the creation of particular amateur/professional distinctions.38 With the subsequent adoption of these proposals, England’s Victorian amateur and professional delineations were incorporated into American intercollegiate athletics. [Ed. Note: See Figures 1 and 2.]

Prior to the adoption of the NCAA proposals, “professionalism” abounded. For example, in the 1850s Harvard University students rowed in a meet offering a $100 first prize purse, and a decade later they raced for as much as $500.39 Amateurism, at least as historically conceived, was largely absent from college sports in the beginning of the twentieth century. Competition for cash and prizes, collection of gate revenue, provisions for recruiting, training, and tutoring of athletes, as well as the payment of athletes and hiring of professional coaches had invaded the arena of intercollegiate athletics.40 … The sheer number of competing American educational institutions was, in itself, a major reason that athletics in the United States developed far beyond the amateurism still displayed [by their] learned British counterparts. In England, an upper level education meant one of two places, either Oxford or Cambridge. With each institution policing the other, the odds of breaching the established standards of amateurism were not high. In the United States, while the Ivy League schools competed strongly amongst themselves, there was also the rapid emergence of many fine public colleges and universities.42 Freedom of opportunity, a pervasive factor in the genesis of American collegiate athletics, made it increasingly more difficult for the Harvards and Yales to maintain themselves as both the athletic and the intellectual elite within the United States.43

According to some scholars, the English system of amateurism, “loosely” derived from the Greeks, simply did not have a chance of success in the United States. As noted above, one factor contributing to its demise was increased competition among a larger number of institutions. Another was the difference in egalitarian beliefs between the two nations:

![]()

Figure 3 NCAA Bylaw 12.01.2—Clear Line of Demarcation

Source: 2009–2010 NCAA Division I Manual, p. 61. © National Collegiate Athletic Association. 2008–2010. All rights reserved.

The English amateur system, based upon participation by the social and economic elite … would never gain a foothold in American college athletics. There was too much competition, too strong a belief in merit over heredity, too abundant an ideology of freedom of opportunity for the amateur ideal to succeed…. It may be that amateur athletics at a high level of expertise can only exist in a society dominated by upper-class elitists.44

In spite of the ideological conflicts, the early post-formative years of the NCAA were spent attempting to enforce the various amateur standards. The first eligibility code sought only to insure that those who participated in collegiate athletics were actually full-time registered students who were not being paid for their participation.45 This initial set of amateur guidelines was largely ignored by the NCAA member institutions. After establishing this initial code, the NCAA sought on numerous occasions to further define its views on amateurism. An intermediate step was the formal adoption of the Amateur Code into the NCAA constitution.46 The impetus behind the adoption was “to enunciate more clearly the NCAA’s purpose; to incorporate the amateur definition and principles of amateur spirit; and to widen the scope of government.”47 As the monetary resources of the NCAA grew, so too did its enforcement power. The prime targets of those enhanced enforcement powers were the principles of amateurism as incorporated into the NCAA constitution. [Ed. Note: See Figure 3.]

The motivation to cheat existed even in the formative years of collegiate sports. Winning athletic programs had the potential to return high revenues to the institution. In its early years as a national football power, Yale University made $105,000 from its successful 1903 football program.48 Thus, the financial incentive to succeed existed even then, and has continued to serve as a strong incentive for many schools to break the rules in order to obtain the best talent.

[Ed. Note: The author’s discussion of the Sanity Code is omitted. See discussion of the Sanity Code in Chapter 13.]

….

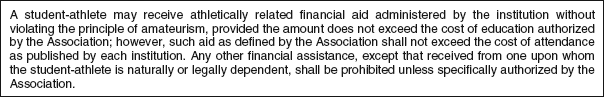

The NCAA was an organization formed to promote safety in collegiate sports. It later adopted the prevailing views of amateurism and is currently the largest sports organization to prohibit member athletes from receiving compensation. [Ed. Note: See Figures 4 and 5.] The lack of compensation for the student participant permeates virtually all decisions in collegiate athletics today. Although the NCAA does not deliberately promote or associate itself with the tales of Greek amateurism, nothing has been done to correct popular misconceptions.

Notes

….

10. David C. Young, The Olympic Myth of Greek Amateur Athletics 7 Ares Publishers (1985).

11. Id.

12. Id.

Figure 4 NCAA Bylaw 12.1.2—Amateur Status

Source: 2009–2010 NCAA Division I Manual, pp. 62–63. © National Collegiate Athletic Association. 2008–2010. All rights reserved.

Figure 5 NCAA Constitution, Article 2.13—The Principle Governing Financial Aid

Source: 2009–2010 NCAA Division I Manual, p. 5. © National Collegiate Athletic Association. 2008–2010. All rights reserved.

13. Id. He notes later that in a single running event the winner received enough money to buy six or seven slaves, 100 sheep or three houses. Id. at 127.

14. Id. at 7.

15. Eugene Glader, Amateurism and Athletics 54 Human Kinetics (1978).

16. Young, supra note 10, at 8.

17. Professor Young cites an article written by classical scholar, Paul Shorey, in The Forum as an example of one of the first misstatements of the actual history:

And here lies the chief, if somewhat obvious, lesson that our modern athletes have to learn from Olympia …. They must strive … only for the complete development of their manhood, and their sole prizes must be the conscious delight in the exercise … and some simple symbol of honor. They must not prostitute the vigor of their youth for gold, directly or indirectly…. [T]he commercial spirit … is fatal, as the Greeks learned …. Where money is the stake, men will inevitably tend to rate the end above the means, or rather to misconceive the true end … the professional will usurp the place of the amateur …. [emphasis in original]. Id. at 9.

Shorey’s article was written prior to the first modern Olympiad held in Athens in 1896 and it was directed at the potential Olympians. Id. at 9. Young maintains further that this was not, in fact, the first revival of the Olympics. Id. He writes that as early as 1870 a modern Olympiad took place in Athens in which cash prizes were awarded. Id. at 31.

18. Id. at 12.

19. Young at 12, 13. See Harold Harris, Greek Athletes and Athletics Greenwood (1964).

20. Young, supra note 10, at 13. The lesson is apparently somewhat self-serving and designed to present in a favorable light the values of the gentlemen amateur athletes of Victorian England. Id.

21. Id. at 14.

22. Id. at 85. Brundage was in strong opposition to Jim Thorpe recovering his forfeited Olympic medals. The irony behind his losing the medals is evident in Thorpe’s own statements referring to the semi-professional baseball games in which he participated. “I did not play for the money … but because I liked to play ball.” Id. While other athletes participated in the same games under a variety of aliases, Thorpe did not even realize he was jeopardizing his amateur and Olympic eligibility. See Pachter, Champions of American Sport 195 (1981).

23. Avery Brundage, USOC Report of the Games of the XIV Olympiad (1948).

24. Id.

….

26. Glader, Amateurism and Athletics 100 (1978).

27. Id. at 100. See also H. Hewitt Griffin, Athletics 13–14 (1891); H.F. Wilkinson, Modern Athletics 16 (1868).

28. Young, supra note 10, at 19.

29. Id.

30. Glader, supra note 26, at 15. The title “amateur” became a badge for upper class gentlemen seeking to evidence their good social standing. Young, supra note 10, at 18.

31. Young, supra note 10, at 18 n. 17.

32. Glader, supra note 26 at 17. See also Ronald A. Smith, Sports & Freedom: The Rise of Big Time College Athletics 166, Oxford University Press (1998) (stating that the eligibility rules of the British Amateur Rowing Assoc. in 1870 contained a similar clause).

33. Glader, supra note 26, at 17. The laborer was classified as a professional due to his unfair physical advantage. Id.

34. Id.

35. Smith, supra note 32, at 166. Although the reference is made to a “professional mode of operation,” university scholarship athletes are not allowed to receive compensation above what amounts to tuition, room, board, and educational fees. Id.

36. H. Savage, American College Athletics (1929), at 36.

37. Young, supra note 10, at 22.

38. Savage, supra note 36, at 42. Specifically:

1. An amateur in athletics is one who enters and takes part in athletic contests purely in obedience to the play impulses or for the satisfaction of purely play motives and for the exercise, training, and social pleasure derived. The natural or primary attitude of mind in play determines amateurism.

2. A professional in athletics is one who enters or takes part in any athletic contest for any other motive than the satisfaction of pure play impulses, or for the exercise, training or social pleasures derived, or one who desires and secures from his skill or who accepts of spectators, partisans or other interests, any material or economic advantage or reward. Id.

39. Smith, supra note 32, at 169 (citing Alexander Agassiz, Rowing Fifty Years Ago, Harv. Graduates Mag., Vol. XV, at 458 (March 1907)); see also Charles W. Eliot, In Praise of Rowing, Harv. Graduates Mag., Vol. XV, at 532 (March 1907); B. W. Crowninshield, Boating, F.O. Vaille; H.A. Clark, The Harvard Book 263 (1875).

40. Smith, supra note 32, at 171.

….

42. Id. at 173.

43. Id. Refusal to compete against other athletically developing schools would have caused Harvard and Yale to lose their athletic “esteem and prestige.” Id.

44. Id. at 174.

45. NCAA Constitution, art. VII, Eligibility Rules (1906). The first NCAA Eligibility Code is set forth below:

The following rules … are suggested as a minimum:

1. No student shall represent a college or university in any intercollegiate game or contest, who is not taking a full schedule of work as prescribed in the catalogue of the institution.

2. No student shall represent a college or university … who has at any time received, either directly or indirectly, money, or any other consideration, to play on any team, or … who has competed for a money prize or portion of gate money in any contest, or who has competed for any prize against a professional.

3. No student shall represent a college or university … who is paid or received, directly or indirectly, any money, or financial concession, or emolument as past or present compensation for, or as prior consideration or inducement to play in, or enter any athletic contest, whether the said remuneration be received from, or paid by, or at the instance of any organization, committee or faculty of such college or university, or any individual whatever.

4. No student shall represent a college or university … who has participated in intercollegiate games or contests during four previous years.

5. No student who has been registered as a member of any other college or university shall participate in any intercollegiate game or contest until he shall have been a student of the institution which he represents for at least one college year.

6. Candidates for positions on athletic teams shall be required to fill out cards, which shall be placed on file, giving a full statement of their previous athletic records. Id.

46. Paul Lawrence, Unsportsmanlike Conduct: The National Collegiate Athletic Association and the Business of College Football 24, Praeger (1987).

47. Id. (citing 1922 NCAA Proceedings at 10.)

48. Benjamin G. Rader, American Sports from the Age of Folk Games to the Age of Spectators 268–269, Prentice-Hall (1983).

REFORM

SYMPOSIUM: SPORTS LAW AS A REFLECTION OF SOCIETY’S LAWS AND VALUES: PAY FOR PLAY FOR COLLEGE ATHLETES: NOW, MORE THAN EVER

Peter Goplerud III

I. INTRODUCTION

Imagine a large group of employees in a company working long hours, some of them far from home, going to school full-time, and helping bring in millions of dollars to their employer. Does this sound like a sweat shop … ? Actually, this describes the typical athlete in a revenue producing sport at a National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) member institution.

Approximately one year ago this author wrote an article advocating a change in the Constitution and Bylaws of the NCAA to provide for the payment of stipends to some athletes at some of its member institutions.1 Specifically, the article proposed the payment of $150 per month to scholarship athletes in the revenue-producing sports of football and men’s basketball and to a comparable number of scholarship athletes in women’s sports. The stipend rule would have applied only to Division I member schools. An underlying premise of the article was that the concept of amateurism, a cornerstone of the NCAA, is essentially a sham due to the commercial nature of the end product. The athletes are used, abused, and then thrown out, while the schools make millions on television money, gate receipts, and sales of licensed products, many directly tied to particular players. The article suggested several legal, political, and financial hurdles that must be considered prior to implementing a policy of providing stipends for players. Included were legal concerns associated with employees, which the athletes would become under the proposal; among these would be workers’ compensation, labor, taxation, antitrust, and gender equity issues. The article also noted the internal politics of the NCAA would be an obstacle, but also opined that the new restructuring might facilitate movement towards the concept of paying players. It also attempted to calculate the costs of providing stipends to approximately 200 athletes at each Division I school. Finally, sources of revenue to pay for the proposal were suggested, notably corporate sponsors and the possibility of a Division I football playoff.

In the intervening time numerous other voices have been heard on the subject and the NCAA itself has considered several alternatives and even adopted what its membership believes to be a compromise between the status quo and the instant proposal.2 However, no substantial or significant progress has been made to this point. The purpose of this article is to renew the call for a change in the rules. At this point, however, a slightly different proposal will be presented. Since this author now believes the current structure and the former proposal both present serious antitrust issues, the proposal will focus on a market-based approach to awarding stipends. It will still be limited to those athletes in revenue-producing sports and proportionate numbers of women athletes.

While there was much talk on the subject of athletes’ rights and the creation of a special task force during the remainder of 1996, the NCAA did very little at the recently completed final convention prior to restructuring. Only a modest change and an arguably ill-conceived concession to costs of attendance was approved with regard to restrictions on work during the school year by athletes on scholarship.3

It thus becomes relevant … to revisit the issue…. The basic premise will remain the same as before: the athletes at Division I schools, particularly those in revenue-producing sports, are exploited on a regular basis and must be compensated beyond the scholarship and beyond the cost of attendance.

II. INTERCOLLEGIATE ATHLETICS AND COMMERCIALISM

[Ed. Note: The author’s discussion of NCAA regulations and commercialism is omitted.]

….

C. The Proposal

It is time to give more serious consideration than ever before to stipends for collegiate athletes. As noted above, the proposal developed a year ago has flaws, mostly legal, which require modification. A market component must be inserted in the stipend, but the proposal must also provide for a certain amount of restraint and competitive balance in keeping with the NCAA’s long-standing concerns for both factors within collegiate athletics. Therefore, the NCAA should develop legislation providing for stipends for athletes in major revenue-producing sports at the Division I level. The stipends should be available to men in football and basketball, and women in basketball, volleyball, and other sports in sufficient numbers to satisfy gender equity requirements. The exact amount of the stipend to an individual athlete would be within the discretion of the individual school. However, the schools should have a limit on the total amount of money allocated to student-athletes. This “salary cap” would be set at an average of $300 per month per scholarship athlete, with half of the money going into a trust fund to be paid to those athletes receiving degrees within five years of matriculation. Those schools with football programs would calculate their football amounts separately with the total amount varying depending upon whether a school is Division I-A or I-AA. These athletes would also be able to work, as under the new rule, with the stipend not counting against the cost of attendance. Schools may, of course, spend less than the cap or may choose not to pay the stipend to any athletes. In addition, scholarship athletes in the non-revenue sports would be allowed to be employed during the school year, even in campus settings, and would have no cap on their earnings. The only stipulation would be that the jobs must be available to non-athlete students as well as athletes.

III. LEGAL ISSUES WHICH ARISE FROM THE PROPOSAL

A. Antitrust Questions

An issue which could arise should the association choose to enact legislation allowing for the payment of players would be a question of price-fixing. The proposal made a year ago is flawed in this respect. It is quite believable that an athlete in a revenue-producing sport would become disgruntled with only receiving $150 per month while competing, and find a resourceful attorney willing to bring an action under the antitrust laws. For reasons discussed below, it is likely that such an action would be successful. Thus, the more prudent legislative action would be the salary cap approach which allows for individual decision-making based upon market determinations developed by the member institutions.

The NCAA has found itself as a defendant in antitrust actions on numerous occasions, with mixed results. Section 1 of the Sherman Antitrust Act provides that: “every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, is hereby declared to be illegal.”31 The Supreme Court has long held that only unreasonable restraints of trade are proscribed by the act.32 Some restraints on economic activity are viewed by the Court as so inherently anti-competitive that they are deemed per se illegal. Examples of this type of conduct would be group boycotts, market divisions, tying arrangements, and price-fixing.33

It is arguable that most of the regulatory activity in which the NCAA engages is per se illegal. Actions such as the establishment of limits on the type and amount of financial aid appear to be price-fixing. Certainly a fixed stipend such as proposed previously appears to be price-fixing. However, in the context of intercollegiate athletics the Supreme Court has recognized that certain types of restrictive activity by the NCAA may, under appropriate circumstances, be allowed under the act.34 The very nature of competitive sports is such that in order to promote competition, some actions which would normally be viewed as restraints will be allowed to exist. The Court has said that “what the NCAA and its member institutions market … is competition itself—contests between competing institutions” and thus, it is “an industry in which horizontal restraints on competition are essential if the product is to be available at all.”35 Any number of rules relating to the size of playing fields, squad size, length of seasons, number of scholarships, academic standards, and the like must be agreed upon in order to market a product, collegiate sports, which might not otherwise be available. The Court, therefore, in reviewing a challenge to the NCAA’s actions in entering into a television contract for football, did not apply the per se rule, instead choosing to use a “rule of reason” analysis. The rule of reason analysis has been utilized in all recent antitrust cases involving the NCAA as well.36

The rule of reason analysis requires the court to determine if the harm from the restraint on competition outweighs the restraint’s pro-competitive impact.37 The plaintiff bears the initial burden of showing the restraint causes significant anti-competitive effects in a relevant market.38 If this burden is met, the defendant must then produce evidence of the restraint’s pro-competitive effects.39 If this is done, the plaintiff must finally show that any legitimate objectives of the restraint can be met through less restrictive means.40

To date, the courts have also been consistent in upholding, against antitrust challenge, every regulatory action of the NCAA which has directly impacted athletes.41 The Supreme Court has, on the one occasion noted above, ruled against the NCAA in an antitrust action involving its proprietary action in entering into contracts for the televising of football games.42 There is, perhaps, reason to believe that even some of the NCAA’s regulatory activities may now be suspect under the Sherman Act.

[Ed. Note: The author’s analysis of Law v. NCAA is omitted.]

….

The NCAA’s limitations on scholarships, in so far as they prohibit stipends, are part of its regulatory program. The association would no doubt contend that these are noncommercial and, therefore, out of the purview of the Sherman Act. One jurist has labeled a similar assertion in regard to the NCAA’s rules on eligibility and the professional football draft “incredulous.”57 It is quite clear that the rules act as a restraint on a relevant market, the labor market for collegiate athletes. They are obviously an attempt to perpetuate the amateur nature of collegiate athletics. But, this overlooks the key to the NCAA and collegiate athletics:

Intercollegiate athletics programs shall be maintained as a vital component of the educational program, and student-athletes shall be an integral part of the student body. The admission, academic standing and academic progress of student-athletes shall be consistent with the policies and standards adopted by the institution for the student body in general.58

Amateurism has certainly been a significant part of the NCAA’s programs, but there have been and continue to be exceptions to this requirement. As recently as the 1960s, the NCAA allowed schools to provide athletes on scholarship with “laundry money.”59 And, the NCAA has long allowed athletes who are clearly professionals, to continue to compete in collegiate athletics in other sports. The only restriction is that they may not receive financial aid from the school.60 Collegiate athletics could survive if stipends were paid to the athletes. The strong allegiances to individual schools and traditions would survive if the athletes in certain sports received a stipend in addition to their tuition and room and board. The athletes would still be required to be full-time students. The stipend would not change the competition on the field, only the nature of the competition for players.

The present system is clearly a restraint. Many athletes do not have the funds to buy clothing, cannot fly home without going to the special assistance fund (except in an emergency), and often struggle to meet ordinary financial requirements of life.61 The restrictions are not necessary to maintain collegiate athletics; as noted there is already precedent for chipping away at the amateur nature of the venture. And, a stipend, coupled with a “salary cap,” is a less restrictive means of promoting collegiate athletics and maintaining competitive balance. It would not be possible under this proposal for a school to offer unlimited amounts of money and, in effect, act like a professional sports team during free agent signing periods.

B. Workers’ Compensation Issues

If the proposal is adopted, even in some modified form, by the NCAA, it is likely that in most jurisdictions the athletes receiving stipends would then be covered by the workers’ compensation laws of those states. Coverage brings with it legal and financial considerations for the athletic departments impacted.62

Workers’ compensation laws are state statutes enacted to compensate workers or their estates for job-related injuries or death, regardless of fault. The underlying premise of this legislation is that accidents in the workplace are inevitable, particularly in the industrial setting, and the burden of injuries caused by such accidents should be borne by the industries that benefit from the labor rather than the employees who are injured.63 This philosophy is implemented by providing an employee with a guaranteed remedy of benefits and medical care in the event of an injury occurring in the course of employment. Employers are generally required to self-insure, contract with a private insurance carrier, or pay into the state workers’ compensation fund.64 Under these statutes, each state has developed its own jurisprudence, and the determination of coverage under particular circumstances would necessitate analysis of the particular statute relevant to a particular circumstance.

[Ed. Note: The author’s analysis of various state provisions is omitted.]

….

Under most state statutes, if the NCAA adopts a stipend provision the athletes on scholarship would probably fall within existing definitions of “employee.” The stipend appears to be a wage paid for services rendered. Intent would, of course, be an issue in that a court would look to whether the stipend was any more tied to services rendered than the rest of the scholarship package. The analysis in Rensing focused on the amateur nature of collegiate athletics and the NCAA’s prohibition on payment of players.95 Such reasoning would no longer be available to a court…. As noted, collegiate athletics is big business. If additional money is paid to players, it is likely that the school will attempt to exercise more control over them. Control, of course, is a factor used in determining whether an employment relationship exists. Arguably, a college scholarship which includes a stipend begins to look more like a professional sports contract that happens to include tuition, fees, room, board, and books as well as a cash component. Under most definitions a recipient of this type of “scholarship” would be an employee.96

The best comparison would be to graduate assistants or teaching assistants on college campuses. The comparison is a valid one in that a graduate assistant in an English department or engineering college will often receive a tuition scholarship plus a stipend. The stipend and the scholarship are awarded in exchange for the student’s serving as a teacher for a set number of classes or laboratory sessions. In the athletic setting, the scholarship and the proposed stipend would be awarded in exchange for the student’s participation in the school’s athletic program. This would include all practice sessions, team meetings, games, and off-season conditioning programs. Failure to participate would, of course, be cause for loss of the scholarship, as would failure to maintain a certain level of competence.97 At the University of Oklahoma, and perhaps many other universities, graduate assistants are treated as any other person on the payroll.98 In other words, the university includes them within its workers’ compensation coverage.99 It is difficult to understand how collegiate athletes would be treated any differently.

C. Other Legal Issues Arising from the Proposal

1. Gender Equity.

Gender equity measures must be taken into account when adopting the proposal. Title IX requires not only equal opportunities for participation, but equal treatment and benefits for athletes with intercollegiate programs.100 Violations of the law will produce actions for injunctive relief and even for monetary damages. It is quite clear that schools providing stipends under the proposal would have to provide the stipends for a proportionate number of women athletes. Any disparities will wave red flags and likely subject the school to sanctions under the law.

2. Labor Law Issues.

Another question which arises in the context of consideration of stipends for collegiate athletes is whether the athletes would then be employees for purposes of the National Labor Relations Act.101 The act essentially gives employees of businesses engaging in interstate commerce the right to organize and engage in concerted activity for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid.102 The act further defines “employee” to mean any employee unless otherwise excluded by the act.103 The courts have construed the act to give the National Labor Relations Board great latitude in determining who is an employee under the act.104 In analyzing the question with regard to collegiate athletes receiving stipends along with their scholarships, one would have to look at the conditions of that scholarship.

Scholarships for collegiate athletes typically require enrollment as a full-time student, compliance with NCAA rules, compliance with athletic department rules, and requirements established by the coaches of the particular sport. The athlete does receive some benefits similar to those of a traditional employee. If the local definition of “employee” required additional benefits to be paid to an athlete, the stipend proposed would be added support for the determination that the athlete is an employee for federal labor law purposes. Certainly the “tools of the trade” are supplied by the athletic department and the university provides the place and time of work. No athlete could be viewed as an independent contractor. The only issue is whether this stipend is for services rendered or simply a part of the scholarship. Consistent with the position taken above, the stipend must be viewed as being paid for services rendered, just as would be the case for a traditional employee. The athlete in a Division I revenue-producing sport is at her institution to participate in sports, and, oh, by the way, get an education. Again, the comparison to a graduate assistant in an academic department is instructive. The stipend paid to the graduate assistant appears to trigger tax consequences and workers’ compensation consequences similar to a traditional employee. It should also trigger labor law consequences, should the athletes desire to take advantage of them.105

It is not hard to imagine the reaction throughout the world of collegiate sports should a court determine that college athletes have the right to form unions. What would be the bargaining unit? Would the linebackers be a separate unit or would they have to organize with the rest of the defensive squad? Again, one would expect significant efforts to influence Congress with regard to specific exclusions for intercollegiate athletics.

3. Taxation Issues.

Currently, athletic scholarships are not taxable to the athlete. Based upon experience with graduate assistants, it is clear that if the stipend is added, at least that portion of the scholarship would constitute taxable income to the athlete.106 This would also add the burden of withholding for income tax as well as for social security and Medicare. It might further provide fuel for those who advocate the general removal of the tax-exempt status of collegiate athletics. Providing the stipend could have an impact on evaluations of unrelated business income for NCAA member institutions.

IV. PRACTICAL FINANCIAL CONCERNS AND WHY IT WON’T HAPPEN OVERNIGHT

Assume for the moment that the legal issues raised above do not deter the membership’s consideration of the proposal. There are nonetheless several serious political and practical concerns. The history and culture of the NCAA have for decades revolved around the concept of amateurism and the notion of the “student-athlete.” Athletics are an integral part of the educational experience. Further professionalizing the programs, the argument goes, destroys this concept. The purists argue that any denigration of the amateurism concept is a giant step towards the destruction of intercollegiate athletics. The former president of the association, Joseph Crowley, said, “the day our members decide it’s time to pay players will be the day my institution stops playing.”107 Even some people who favor increased attention to athletes’ welfare believe that paying athletes is not a good idea.108

There are, however, some very respected coaches who believe it is time to support the concept of paying stipends to athletes. Tom Osborne of the University of Nebraska has argued for many years that players should be able to receive money for living expenses.109 … However, even many who conceptually support the proposal acknowledge the enormous practical and financial difficulties presented….

There are sources of revenue or ideas for revenue redistribution which could support the proposal. As noted, the NCAA budget is $239 million for 1996–97.111 That figure will go up in the coming years. [Ed. Note: The NCAA budget for 2009–2010 was $710 million.] The bowl games following the 1996 college season paid out over $100 million to participating schools and their conferences.112 Estimates are that licensed products generate over $2 billion annually in sales, providing generous royalties for colleges and universities. Corporate sponsorship agreements with individual schools provide additional funds. The NCAA Basketball Championship generates in excess of $50 million annually for the member schools; and, if the NCAA ever approves a national football championship playoff system, an additional $100 million or more will be available for distribution to the schools. Finally, there are television contracts and gate receipts that add to the revenues of most of the Division I schools.

The other side of the equation begins with the reality that many of the Division I schools lose money on their athletic programs.113 Even those making money argue they have very little flexibility in their budgets, particularly those with gender equity pressures.114 The proposal as structured above would cost approximately $29 million annually, with the impact as high as $400,000 for Division I-A football schools.115

While there is no doubt that absorbing these costs would be difficult for most schools, there are sources of revenue which could support the proposal. It will require athletic administrators to be creative and to look for ways to cut costs in existing programs without cutting quality and equality. It is arguable that many, if not most, Division I athletic programs have unnecessary extravagance and duplication. It may also be time to suggest to the professional sports leagues that direct subsidies are due their “minor leagues,” the college athletic programs. Corporate sponsors such as McDonald’s or Nike should be considered as potential benefactors of this program. For the present, however, these outside sources are not available in any meaningful way. Therefore, existing funding would have to be utilized to implement the proposal for stipends for athletes.

The cost of the stipend is not the only cost presented. If the athlete is viewed as an employee in a given state for workers’ compensation purposes, the schools may have to purchase insurance coverage. There may also be additional insurance or fringe benefit costs associated with a determination of employee status. If the program begins to look more professional than amateur, there may be tax consequences to the schools with very significant price tags. If athletes had success with either the potential claims under the Sherman Act or those under Title IX, costs would escalate. Then there is the possibility of added leverage through unionization and collective bargaining. This too would have additional costs.

It is difficult to be sympathetic to concerns for the loss of amateurism in collegiate sports as a result of consideration for stipends. When a school makes an estimated $4 million in revenues directly traceable to the participation of one basketball player, concerns over the loss of amateurism are difficult to swallow.116 Intercollegiate athletics revolves around big money. Winning brings more money to programs and, thus, coaches are under pressure to produce. Those who do produce at the Division I level can expect six and seven figure annual incomes. Athletes spend twelve months a year playing, practicing, and training for their particular sport. For approximately eight months per year they are also students. The athletes are primarily responsible for the generation of the revenues used to pay the aforementioned coaches and programs. In return, they receive, relatively speaking, incredibly poor compensation. The days of sports at the collegiate level, at least in Division I programs, being “just a game” are long gone.117 Sports have a way of putting educational institutions on the map. How many people would know of the College of Charleston without basketball?

Finally, it is suggested that amateurism in and of itself is not the reason most fans watch collegiate sports.118 Loyalties to educational institutions and to tradition are very important. Ticket prices for collegiate events are more affordable than for professional events, and a modest stipend for athletes will not alter that situation. Rivalries and the national championships sanctioned by the NCAA are a natural attraction. A retreat from pure amateurism will not detract from this attraction.

More attention must be paid to athletes’ welfare. The relaxation of the work restrictions is well-intentioned, but is misdirected. It is counter to the association’s own concerns over the amount of time the athletes have in a day for sports, school, and life. It throws one more factor into the mix, which is a mistake. There are, of course, natural concerns over athletes having jobs under this rule which pay good wages for little or no work. Policing will be a nightmare.

It is time for collegiate athletes to receive monthly stipends as part of their scholarship package. Even Walter Byers, former longtime Executive Director of the NCAA, now calls for fair treatment of athletes, including relaxation of restrictions on compensation and outside income.119 We are no longer in an age of innocence where there is no commercialism in college athletics. It is big business and those most responsible for the product put on the field, the players, should be compensated.

Notes

1. C. Peter Goplerud, Stipends for Collegiate Athletes: A Philosophical Spin on a Controversial Proposal, 5 Kan. J.L. & Pub. Pol’y 125, 127 (1996).

2. See Steve Wulf, Tote That Ball, Lift That Revenue; Why Not Pay College Athletes, Who Put in Long Hours to Fill Stadiums—and Coffers?, Time, Oct. 21, 1996, at 94 (recognizing that the colleges and coaches make money at the athletes’ expense); see also Ray Yasser, Essay: A Comprehensive Blueprint for the Reform of intercollegiate Athletics, 3 Marq. Sports L.J. 123 (1993) (examining the NCAA and proposing reform).

3. See Jack L. Copeland, Delegates OK Key Athlete-Welfare Legislation, NCAA News, Jan. 20, 1997, at 1.

….

31. Sherman Act, 15 U.S.C. 1 (1990).

32. See Standard Oil Co. v. United States, 221 U.S. 1, 56 (1911).

33. See White Motor Co. v. United States, 372 U.S. 253, 259-260 (1963).

34. See NCAA v. Board of Regents of the Univ. of Okla., 468 U.S. 85, 119 (1984).

35. NCAA v. Board of Regents of the Univ. of Okla., 468 U.S. 85, 101 (1984).

36. See Banks v. NCAA, 977 F.2d 1081, 1086 (7th Cir. 1992); McCormack v. NCAA, 845 F.2d 1338, 1344 (5th Cir. 1988); Law v. NCAA, 902 F. Supp. 1394, 1403 (D. Kan. 1995); Gaines v. NCAA, 746 F. Supp. 738, 746 (M.D. Tenn. 1990).

37. See Hairston v. Pacific 10 Conference, 101 F.3d 1315, 1319 (9th Cir. 1996).

38. See id.

39. See id.

40. See id.

41. See, e.g., Banks, 977 F.2d at 1094; McCormack, 845 F.2d at 1345; Justice v. NCAA, 577 F. Supp. 356, 383 (D. Ariz. 1983).

42. See Board of Regents of the Univ. of Okla., 468 U.S. at 88.

….

57. Banks v. NCAA, 977 F.2d 1081, 1098 (7th Cir. 1992). (Flaum, J., concurring in part and dissenting in part).

58. 1996–1997 NCAA Manual (1996), at 2.5.

59. Steve Wulf, Tote That Ball, Lift That Revenue; Why Not Pay College Athletes Who Put in Long Hours to Fill Stadiums and Coffers? Time, Oct. 21, 1996, at 94.

60. See NCAA Manual, supra note 58, at 12.1.2.

61. See, e.g., Brian Carnell, Another View: Free the Athletes and Scrap the NCAA, Detroit News, Jan. 23, 1997, at A15 (arguing that the players do most of the work and assume all of the risk, yet are prevented from sharing in the results of their labor); Ron Maly, Hawk-eyes’ Verba: Players Feeling Cheated, Des Moines Reg., Jul. 28, 1996, at Big Peach 4 (describing the financial struggles of scholarship athletes); Michael Costello, Some Cheating: Sharing the Booty with Athletes, Lewiston Morning Trib., Mar. 16, 1996, at A12 (stating that students “grind their bones into dust for next to nothing”).

62. See generally Goplerud, supra note 1, at 127-128 (discussing workers’ compensation as it would relate to student athletes on a stipend). Much of the following discussion appeared initially in the Kansas article and is used here with permission of the journal.

63. See generally Richard A. Epstein, The Historical Origins and Economic Structure of Workers’ Compensation Law, 16 Ga. L. Rev. 775 (1982) (commenting upon the central features of the history and of the debate that workers’ compensation law has generated); Ray Yasser, Are Scholarship Athletes At Big-Time Programs Really University Employees?—You Bet They Are!, 9 Black L.J. 66 (1984) (exploring how courts treat the relationship between athletes and educational institutions when the student-athlete is injured and tries to recover against the school under local workers’ compensation laws); Sean Alan Roberts, Comment, College Athletes, Universities, and Workers’ Compensation: Placing the Relationship in the Proper Context by Recognizing Scholarship Athletes as Employees, 35 S. Tex. L. Rev. 1315 (1996) (focusing on the applicability of the Texas workers’ compensation statute to scholarship athletes).

64. See Arthur Larson, Workers’ Compensation Law: Cases, Materials, and Text 795 (1992).

….

95. Rensing v. Indiana State Univ. Bd. of Trustees, 444 N.E.2d 1170 (Ind. 1983) at 1172–73.

96. See generally Alan Roberts, Comment, College Athletes, Universities, and Workers’ Compensation: Placing the Relationship in the Proper Context by Recognizing Scholarship Athletes as Employees, 35 S. Tex. L. Rev. 1315 (1996), at 1341 (noting Texas’ liberal definition of employee on a quid pro quo basis); Ray Yasser, Essay: A Comprehensive Blueprint for the Reform of Intercollegiate Athletics, 3 Marq. Sports L.J. 123 (1993), at 137 (calling an athletic scholarship an oxymoron and comparing it more to a one-year renewable contract).

97. Today, scholarships are one-year awards. During the typical recruitment process the athlete is promised a four- or five-year scholarship. This is actually delivered on a year-to-year basis and there are some schools or coaches that do not renew scholarships to certain players. This can be done under current rules so long as there is notice and some opportunity to discuss the non-renewal of the scholarship.

98. See Telephone Interview with Sandy Pruett, Administrative Assistant to the Director of Personnel, University of Oklahoma (Feb. 28, 1996).

99. See id.

100. See Cohen v. Brown Univ., 101 F.3d 155, 166-67 (1st Cir. 1996).

101. 29 U.S.C. § 151 (1994).

102. See id. § 157. It is assumed no one will argue that the NCAA is not engaged in interstate commerce.

103. See id. § 152.

104. See generally NLRB v. O’Hare-Midway Limousine Serv., Inc., 924 F.2d 692 (7th Cir. 1991) (holding that whether an individual is an employee is a factual matter focusing on the employer’s ability to control the purported employee and analyzing characteristics of an employer-employee relationship, including how payment for services is determined; whether the employer provides benefits; who provides tools or other materials to perform the work; who designated where the work is done, and whether the relationship is temporary or permanent).

105. Periodically, there are calls for college athletes to strike over some issue. Indeed, Bob Knight, the legendary Indiana University basketball coach has recently suggested such a move to respond to mistreatment of athletes by the NCAA. See Fish, supra note 56, at E6. Application of the labor laws to athletes receiving a stipend would likely allow the athletes to organize and, under appropriate circumstances, strike.

106. See 26 U.S.C. § 117 (1994).

107. Curry Kirkpatrick, The Hoops Are Made of Gold, Newsweek, Apr. 3, 1995, at 62.

108. See John Eisenberg, NCAA On The Right Track With New Part-Time Job Rule, Baltimore Sun, Jan. 20, 1997, at C1.

109. See Paying College Athletes a Bad Idea: Scholarship Rules Could Be Fairer, Omaha World Herald, Jan. 18, 1995, at 18.

….

111. See Fish, supra note 56, at E6.

112. See id.

113. See Maly, supra note 61, at Big Peach 4; Ed Graney, Scheduling Changes Hit Aztecs in Pocketbook, San Diego Union-Trib., Oct. 8, 1996, at D1; John Williams, Mounting Defeat Threatens UH Sports Programs, Hous. Chron., June 27, 1996, at A1.

114. David Nakamura, Equity Leaves Its Mark on Male Athletes; Some Schools Make Cuts to Add Women’s Sports, Wash. Post, Jul. 7, 1997, at A1.

115. See Bob Hurt, Paying College Athletes Has Major Obstacles, Ariz. Republic, May 5, 1995, at E2.

116. See W. D. Murray, NCAA’s Top Product Faces Big Challenge—Top Players Leave for More Compensation, Seattle Times, Mar. 30, 1997, at D2.

117. At least one judge has clearly noticed the change:

The NCAA would have us believe that intercollegiate athletic contests are about spirit, competition, camaraderie, sportsmanship, hard work … and nothing else…. Players play for the fun of it, colleges get a kick out of entertaining the student body and alumni, but the relationship between players and colleges is positively noncommercial…. The NCAA continues to purvey, even in this case, an outmoded image of intercollegiate sports that no longer jibes with reality. The times have changed. College football is a terrific American institution that generates abundant nonpecuniary benefits for players and fans, but it is also a vast commercial venture that yields substantial profits for colleges, … both on and off the field. Banks v. NCAA, 977 F.2d 1081, 1098-99 (7th Cir. 1992) (Flaum, J., concurring in part and dissenting in part).

118. See generally Mitten, supra note 56 (arguing that limitations on scholarships currently a part of the NCAA rules are violative of antitrust laws). Professor Mitten notes

It is unlikely that the tremendous popularity of intercollegiate sports is a result of the amateur status of college athletes. Other factors seem to be more significant in accounting for the strong national public interest in college sports. For example, alumni pride and loyalty, tradition, long-standing rivalries, national rankings, conference and national championship tournament competition, and exciting play probably contribute to the public obsession with college sports more than the “amateur” status of college athletes.

Id. at 78.

119. See Walter Byers, Unsportsmanlike Conduct: Exploiting College Athletes (University of Michigan Press 1995).

ADVICE FOR THE NEXT JEREMY BLOOM: AN ELITE ATHLETE’S GUIDE TO NCAA AMATEURISM REGULATIONS

Christopher A. Callanan

INTRODUCTION

Jeremy Bloom presented a unique challenge to the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) regulations on amateurism because, as a world-class freestyle moguls skier and Division I football player, he was a marketable athlete.1 By declaring Bloom ineligible to compete as an NCAA football player in the event he accepted the customary financial benefits of professional skiing, the NCAA created myriad issues for similarly situated athletes. Although Bloom was among the first athletes to raise the issue, he will be by no means the last. Emerging nontraditional sports, particularly action sports, attract younger athletes. These sports are aggressively marketed to young audiences through the endorsement of young athletes. Thus, more and more athletes at younger ages receive opportunities to participate in activities that, without careful consideration, can jeopardize present and future athletic eligibility at the scholastic and collegiate level.

As a result of Jeremy Bloom’s case (Bloom v. National Collegiate Athletic Association), individual sport, Olympic, and action sport athletes as well as other talents who also compete (or hope to compete) in scholastic and NCAA sports must exercise particular caution. Given the detail of NCAA Bylaws, it is impossible to cover every scenario or exception here. Instead, the following is intended to introduce athletes and their families to common issues that arise and to suggest strategies for informed decision-making in light of the Bloom decision.

KNOW THE RULES: THEY APPLY SOONER THAN YOU THINK

Any athlete who is or hopes to be eligible to participate in collegiate athletics is bound by the NCAA Bylaws.2 Conduct before and during NCAA participation can jeopardize eligibility.3 In addition, each state regulates scholastic eligibility. Most states follow the NCAA Bylaws as they relate to amateurism, so this discussion focuses on NCAA regulation. However, every pre-high school and high school athlete must consider both state regulations and the NCAA Bylaws.

AGENTS AND LAWYERS: WHAT ADVICE IS PERMITTED?

Bylaws 12.1.1(g)4 and 12.35 declare an athlete ineligible if he or she enters into an agreement with an agent to market his or her reputation or ability in that sport. An agreement that does not limit itself to a particular sport makes an athlete ineligible in all sports.6 An athlete may secure advice from a lawyer concerning a proposed professional sport, contract, so long as the lawyer does not also represent the athlete in negotiations for that contract.7

“SALARIED” PROFESSIONAL ATHLETES: PROHIBITIONS AND EXCEPTIONS

Bylaw 12.1.18 characterizes the activities that destroy amateur status required for NCAA eligibility. Using skill in a sport for pay (12.1.1.(a)), accepting a promise of pay (12.1.1.(b)), signing a professional contract (12.1.1.(c)), and agreeing with an agent (12.1.1.(g)), are among the activities that destroy athletic eligibility. A specific exception to this rule permits many athletes to play minor league baseball while retaining eligibility to play college football.9 Several well-known athletes have used this exception to their advantage, such as Chris Weinke, Cedric Benson, Drew Henson, and Ricky Williams. Bylaw 12.1.2 permits a professional athlete in one sport to retain eligibility in another sport.10 However, the athlete cannot receive financial aid in the eligible sport if he or she is still involved with professional athletics, receives any pay from any professional sports organization, or has any active contractual relationship.11

NAVIGATING THE MURKY WATERS OF ENDORSEMENT AND PROMOTIONAL INCOME: JEREMY BLOOM’S CHALLENGE TO THE NCAA

Jeremy Bloom argues that the 12.1.2 exception for “professional athletes in another sport” should permit him to accept the customary income for professional skiing—product endorsements and marketing activities—without jeopardizing his eligibility to play NCAA Division I football.12 Bloom compared the salary paid to a minor league baseball player to the endorsement and marketing income customarily earned by a professional skier.13 Both are customary forms of payment in the respective professional sports. In rejecting his claim, the NCAA cited two regulations dealing with commercial activity to distinguish permissible salary income from prohibited marketing income.

Bylaw 12.5.2.1(a) prohibits a college athlete, subsequent to enrollment from accepting pay for or permitting the use of his or her name or picture “to advertise, recommend or promote directly the sale or use of a commercial product.”14 Bylaw 12.5.2.1(b) prohibits receiving pay for endorsing a commercial product or service through the athlete’s use of the product or service.15 These bylaws prohibit any college athlete from endorsing a product or service by using the product or service or lending the athletes’ name, image, or likeness to promote the product or service.16

Bylaw 12.4.1.1, the “Athletics Reputation” rule17 prohibits a student-athlete from receiving compensation from anyone (not just an advertiser or marketer) in exchange for the value that the student-athlete provides to the employer for the athlete’s “publicity, reputation, fame or personal following” obtained because of athletic ability.18 This rule prohibits commercial activity by a student-athlete even if it does no[t] involve promotion, endorsement, or product use, but exists in part as a result of the athlete’s goodwill as an NCAA athlete.

Through these bylaws, the NCAA distinguishes salary income in a sport like baseball or football from endorsement, promotional, or reputation income.19 In deciding the Bloom case, the Colorado Court of Appeals noted that the NCAA Bylaws consistently prohibit student-athletes from engaging in any form of paid endorsement or media activity.20 The court enforced the bylaws as written because, despite their disproportionate impact on athletes of different sports, the Bylaws are unambiguous and consistent in prohibiting any form of commercial activity by any athlete.21

The Bloom decision suggests that the NCAA and courts asked to interpret NCAA Bylaws will continue to strictly interpret amateurism regulations to forbid marketing, endorsement, or media-related income (or activity) by student-athletes regardless of the circumstance. The continued prevalence of endorsement and media activity in popular culture is unlikely to generate change in the NCAA system. It will only increase the number of athletes who knowingly or inadvertently face the consequences of strictly interpreted bylaws.

One practical difficulty in likening endorsement income to salary income is that it is impossible to determine the degree to which an athlete’s marketability derives from his or her simultaneous status as an NCAA athlete. In his case, Bloom could not show that none of his marketability resulted from his Colorado football career. As a result, he was unable to convince the court that his proposed activity complied with otherwise unambiguous bylaws prohibiting any kind of commercial activity by student-athletes.

Even if the NCAA could measure the source of an athlete’s marketability or if it decided to undertake the effort to distinguish permissible kinds of income to be fairer to skiers and other similar athletes, it has no financial incentive to do so. Allowing student-athletes to accept paid endorsement or media income provides marketers an alternative (and likely cheaper) way to associate with the goodwill of college sports. Given the present system’s great financial reward to the NCAA and its institutions, neither is likely to voluntarily change the present system. These realities create great risk for athletes who participate in sports (or other similar activities) where endorsement and media income are customary.

BEWARE THE BREADTH OF COMMERCIAL ACTIVITY

Aaron Adair’s story demonstrates the breadth of commercial activity as interpreted by the NCAA.22 Adair was a Texas high school baseball star and highly touted professional prospect when he was diagnosed with brain cancer.23 After a successful treatment, rehabilitation and arduous comeback, Adair worked his way back to competitive baseball.24 He ultimately accepted a scholarship to play Division I baseball at the University of Oklahoma.25 While he was in college, Adair lost his father to leukemia.26 Adair authored a book, You Don’t Know Where I’ve Been, chronicling his own struggle to overcome cancer and to deal with the loss of his father.27 While promoting the book throughout Texas and Oklahoma, the University, through its NCAA compliance officer, informed Adair that he was engaging in prohibited commercial activity—the promotion and sale of his book.28 Adair’s book ended his NCAA eligibility and baseball career.

Athletes involved in the performing arts must also be vigilant. Many of the arguments raised by Jeremy Bloom were originally made by Northwestern University football player Darnell Autry. Autry successfully overcame the NCAA’s objection to his participation in a feature film, The Thirteenth Angel.29 Autry, a theatre major, obtained an injunction permitting him to act by showing that the opportunity was relevant to his studies and anticipated career, did not result from or relate to his athletic reputation, and would not result in payment beyond expense reimbursement.30 Addressing similar issues, bylaw 12.5.1.3 permits an athlete to continue modeling activities unrelated to athletic activity that the athlete participated in prior to enrollment under specific conditions.31 Similar issues have arisen with athletes who publish local restaurant reviews and participate in music videos. Although each circumstance is different, the degree to which each opportunity relates to athletic ability or to one’s student-athlete status is always an important factor in determining permissibility. As athletes continue to participate in various activities that generate commercial and media attention, challenges to traditional definitions of amateurism will continue.

….

Notes

1. Bloom v. NCAA, 93 P.3d 621 (Colo. Ct. App. 2004). For instructive discussion of the Bloom litigation and controversy, see Christian Dennie, Amateurism Stifles a Student-Athlete’s Dream, 12 SPORTS LAW. J. 221 (2005); Alain Lapter, Bloom v. NCAA: A Procedural Due Process Analysis and the Need for Reform, 12 SPORTS LAW. J. 255 (2005); Gordon E. Gouveia, Making a Mountain Out of a Mogul: Jeremy Bloom v. NCAA and Unjustified Denial of Compensation Under NCAA Amateurism Rules, 6 VAND. J. ENT. L. & PRAC. 22 (2003).

2. NCAA BYLAWS, reprinted in NAT’L COLLEGIATE ATHLETIC ASS’N, 2005-2006 NCAA DIVISION I MANUAL (2005), available at http://www.ncaa.org/library/membership/division_i_manual/2005-06/2005-06_d1_manual.pdf [hereinafter NCAA MANUAL].

3. “Amateurism” states that: “A student-athlete shall not be eligible for participation in an intercollegiate sport if the individual takes or has taken pay, or has accepted the promise of pay in any form, for participation in that sport or if the individual has violated any of the other regulations related to amateurism set forth in Bylaw 12.” Id. § 14.01.3.1 (emphasis added). Bylaw 12.01.3 states that “NCAA amateur status may be lost as a result of activities prior to enrollment in college.” Id. § 12.01.3.

4. Id. § 12.1.1(g).

5. Id. § 12.3.

6. Id. § 12.3.1.

7. Id. § 12.3.2.

8. Id. § 12.1.1.

9. Id. § 12.1.2.

10. Id.

11. Id.

12. Bloom v. NCAA, 93 P.3d 621, 625 (Colo. Ct. App. 2004).

13. Id. at 625.

14. NCAA BYLAWS § 12.5.2.1(a), reprinted in NCAA MANUAL, supra note 2.

15. Id. § 12.5.2.1(b).

16. Id.

17. Id. § 12.4.1.1.

18. Id.

19. Bloom v. NCAA, 93 P.3d 621, 625-26 (Colo. Ct. App. 2004).

20. Id. at 626.

21. Id.

22. See Aaron Adair Website, http://www.aaronadair.com (last visited Apr. 23, 2006) (providing an account of Mr. Adair’s story); see also Dennie, supra note 1.

23. Aaron Adair Website, supra note 22.

24. Id.

25. Id.

26. Id.

27. Id.; see also AARON ADAIR, YOU DON’T KNOW WHERE I’VE BEEN (2003); Description and Reviews of You Don’t Know Where I’ve Been, http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/1553955145/qid=1145890634/sr=1-1/ref=sr_1_1/103-2448975-0787006?s=books&v=glance&n=283155 (last visited May 10, 2006).

28. Dennie, supra note 1, at 236-37.

29. Description of The Thirteenth Angel, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0119055/ (last visited May 10, 2006).

30. Dennie, supra note 1, at 233.

31. NCAA BYLAWS § 12.5.1.3, reprinted in NCAA MANUAL, supra note 2.

THE GAME OF LIFE

James L. Shulman and William G. Bowen

KEY EMPIRICAL FINDINGS

… We have used the extensive institutional records of the 30 academically selective institutions in the study to learn about the pre-collegiate preparation of athletes and other students in the 1951, 1976, and 1989 entering cohorts and their subsequent performance in college. We have also followed the approach suggested more than a century ago by the Walter Camp Commission on College Football and analyzed the experiences and views of both former athletes and other students who attended these schools. In seeking to move the debate over intercollegiate athletics beyond highly charged assertions and strongly held opinions, we use this chapter to summarize the principal empirical findings that we believe deserve the attention of all those who share an interest in understanding what has been happening over the course of the past half century.

….

Scale: Numbers of Athletes and Athletic Recruitment

1. Athletes competing on intercollegiate teams constitute a sizable share of the undergraduate student population at many selective colleges and universities, and especially at coed liberal arts colleges and Ivy League universities. In 1989, intercollegiate athletes accounted for nearly one-third of the men and approximately one-fifth of the women who entered the coed liberal arts colleges participating in this study; male and female athletes accounted for much smaller percentages of the entering classes in the Division I-A scholarship schools, which of course have far larger enrollments; the Ivies are intermediate in the relative number of athletes enrolled, with approximately one-quarter of the men and 15 percent of the women playing on intercollegiate teams. Some of the much larger Division I-A schools, public and private, enrolled a smaller absolute number of athletes than either the more athletically oriented coed liberal arts colleges or the Ivies—primarily because a number of the Division I-A schools sponsor fewer teams.

2. The relative number of male athletes in a class has not changed dramatically over the past 40 years, but athletes in recent classes have been far more intensely recruited than used to be the case. This statement holds for the coed liberal arts colleges as well as the universities. In 1989, roughly 90 percent of the men who played the High Profile sports of football, basketball, and hockey said that they had been recruited (the range was from 97 percent in the Division I-A public universities to 83 percent in the Division III coed liberal arts colleges), and roughly two-thirds of the men who competed in other sports such as tennis, soccer, and swimming said that they too had been recruited. In the ’76 cohort, these percentages were much lower; there were many more “walk-ons” in 1976 than in 1989, and there were surely fewer still in the most recent entering classes.

3. Only tiny numbers of women athletes in the ’76 entering cohort reported having been recruited, but that situation had changed markedly by the time of the ’89 entering cohort; recruitment of women athletes at these schools has moved rapidly in the direction of the men’s model. Roughly half of the women in the ’89 cohort who played intercollegiate sports in the Ivies and the Division I-A universities reported that having been recruited by the athletic department played a significant role in their having chosen the schools they attended. The comparable percentages in the coed colleges and the women’s colleges were much lower in ’89, but women athletes at those schools are now also being actively recruited.

Admissions Advantages, Academic Qualifications, and Other “Selection” Effects

1. Athletes who are recruited, and who end up on the carefully winnowed lists of desired candidates submitted by coaches to the admissions office, now enjoy a very substantial statistical “advantage” in the admissions process—a much greater advantage than that enjoyed by other targeted groups such as underrepresented minority students, alumni children, and other legacies; this statement is true for both male and female athletes. At a representative non-scholarship school for which we have complete data on all applicants, recruited male athletes applying for admission to the ’99 entering cohort had a 48 percent greater chance of being admitted than did male students at large, after taking differences in SAT scores into account; the corresponding admissions advantage enjoyed by recruited women athletes in ’99 was 53 percent. The admissions advantages enjoyed by minority students and legacies were in the range of 18 to 24 percent.

2. The admissions advantage enjoyed by men and women athletes at this school, which there is reason to believe is reasonably typical of schools of its type, was much greater in ’99 than in ’89, and it was greater in ’89 than in ’76. The trend—the directional signal—is unmistakably clear.

3. One obvious consequence of assigning such a high priority to admitting recruited athletes is that they enter these colleges and universities with considerably lower SAT scores than their classmates. This pattern holds for both men and women athletes and is highly consistent by type of school. The SAT “deficit” is most pronounced for men and women who play sports at the Division I-A schools, least pronounced for women at the liberal arts colleges (especially the women’s colleges), and middling at the Ivies. Among the men at every type of school, the SAT deficits are largest for those who play the High Profile sports of football, basketball, and hockey.