Why do people play games? It feels a little ridiculous to even ask this question, because the answer seems obvious: people play games to have fun. Do we really need a grand explanation beyond that? Well, if your interest in games doesn’t extend beyond playing them, I’ll grant you that the simple answer is probably enough. But for a game designer, there are at least two problems with such a basic explanation of player motivation.

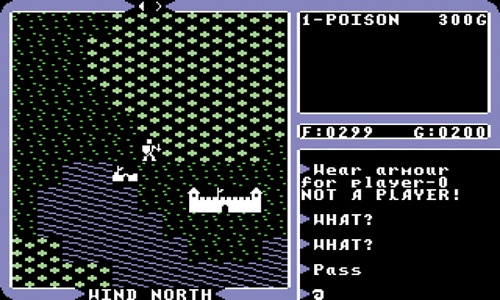

For one thing, it doesn’t account for the nearly masochistic things people are willing to do when playing a game. Many of the most popular role-playing games, for example, require players to fight the same enemies over and over again (and then again and again) to get the experience and loot they need to advance in the game (Figure 4-1). Players may spend dozens of hours in thousands of battles. So many games involve these kinds of endless repetitive actions that the gaming community has given it a name: grinding. This term is related to how we describe work we really don’t enjoy—as “a grind.” So why do people pay good money to subject themselves to something that’s as unpleasant as the work an employer would pay them to do? This is a really big problem if your only explanation for why people play games is to have fun.

Figure 4-1. Role-playing games like Final Fantasy XIII involve countless battles against similar enemies.

Second, there isn’t a clear definition of what we mean when we say “fun.” Different people experience fun differently. A lot of people love riding roller coasters, but when I get on one I hope only for a swift death. Some people have a blast at work, while others would be tortured by the same job. There are even some people who don’t have any fun at all playing video games. Because the concept of fun is so slippery, it can’t help inform design decisions. You can’t build a game to satisfy a need you can’t define.

So, then, why are people so drawn to video games? What do they expect the experience of playing a game to provide? Human psychology provides a lot of insight into these questions.

Getting a handle on players’ motivations is extremely important because it tells you what your game needs to accomplish to fulfill their expectations, and that in turn helps to inform design. It’s very easy to fall into the trap of thinking that people will play a game just because it’s a game and, well, people like games. If you approach game design with that mind-set, you run the risk of putting in a lot of effort to build something that no one will want to play. Any game experience is much more likely to be successful when its design is rooted in an understanding of why people would want to play it.

Unfortunately, there is no single universal reason why people play games, and a variety of (often competing) models have been proposed to describe player motivation. Part of the appeal of video games is that they can satisfy many different kinds of human needs and desires, which often overlap with few clear divisions to distinguish them. What follows is a partial list of common motivations that explain the appeal of many games. In each case I suggest some ways that games can be designed to satisfy that motivation. When creating a design, it’s worth setting aside some time to think about which motivations your game will fulfill.

Every dedicated gamer knows the experience of being deeply immersed in a video game. You’re doing pretty well and really enjoying yourself, when you discover that hours have passed in what felt like minutes. Then you notice a terrible burning sensation in your eyes. You realize you’ve unconsciously stopped blinking, setting aside a real physical need to minimize the risk that something terrible might happen to your game self while you weren’t looking. This kind of experience demonstrates the powerful capacity of video games to immerse people in an alternate universe where the concerns of everyday life disappear.

Under ideal circumstances, a deep experience of immersion in a game can lead to what psychology theorist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi calls “flow,” a state of heightened focus and engagement in an activity.[18] Flow may occur when you’re running a marathon, mowing the lawn, or playing the piano. It’s characterized by feelings of contentment and well-being, even euphoria. Players need to be reasonably skilled with a game before flow can set in. It won’t happen when a player is new to a game, because new players are spending too much time just figuring out how to operate it. Once players are able to concentrate on the challenges of gameplay instead of the interface, they’re primed for a state of flow.[19]

Psychologist Jamie Madigan proposes that designers can deepen the experience of immersion in a game by maximizing the richness and consistency of the game environment.[20] “Richness” refers to robust detail and depth in the game world, as well as the presence of challenges that are cognitively demanding. These qualities pull a person further into the experience. “Consistency” means that nothing breaks the illusion. Everything should abide by the rules of the game world, and behave as you would expect it to if you really lived in that world. Glitches in the programming, incongruous dialog, or gratuitous in-game advertising risks pulling players out of the game experience.

Many modern video games, like Grand Theft Auto, go to elaborate lengths to construct worlds of staggering richness and consistency (Figure 4-2).

Figure 4-2. The urban setting in Grand Theft Auto IV is built to a remarkable level of detail, inviting the impression of a real living city.

You don’t necessarily have to spend zillions to achieve a similar effect. Designers always depend on the player to enable the experience of immersion, because no game world is exactly like life as we know it. Players who desire to be immersed in an alternate reality are willing to suspend their disbelief and fill in the gaps.

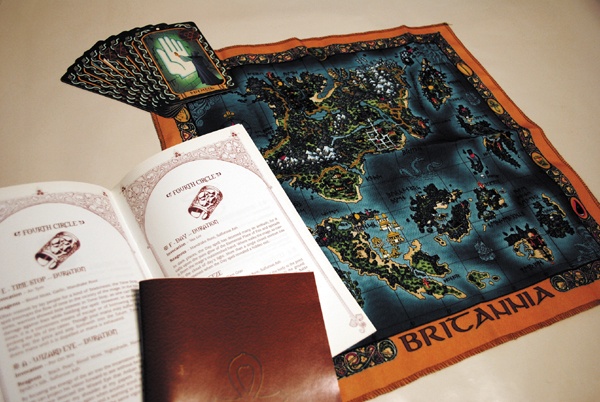

Ultima, a series of open-world role-playing games from the 1980s, was very committed to creating a rich and consistent alternate reality, despite its very rudimentary graphics (Figure 4-3). Each edition in the series was set in an enormous world full of cities, towns, and dungeons containing large numbers of characters the player could talk to, befriend, or fight. The games came with physical maps, books, and trinkets lifted from its elaborate mythology (Figure 4-4). Parts of the game were even written in a fictitious alphabet the player needed to learn. Despite the limitations of the technology, Ultima invited players to escape into a parallel universe and lent support to those who were willing to take the leap.

Some players enjoy games that offer them the freedom to exercise control over their own actions as they see fit. Real life can be very structured, with a regular daily routine and little room for rule breaking. It can be refreshing to play a game in which few formal rules apply, and the degree of autonomy that such a game gives its players is very strongly related to how much people enjoy playing it.[21]

The Grand Theft Auto games, for example, give players tremendous autonomy, allowing them to do whatever they want, whenever they want, in a game world that has few boundaries. Players can choose from a broad variety of missions, quests, and minigames that are available at all times. They can also decide just to hop in a car, cruise around the city, and flip through radio stations as they watch the sunrise. If and when they feel like it, players can go shopping for clothing, invest in real estate, gamble at a casino, go on a date, pick up taxi fares, rescue people in an ambulance, go on a murderous rampage, or deliver pizzas. The game has very little to say about what players should do, while ensuring that they can do nearly anything. Which action to take is left to the players’ own discretion.

Contrast this design with games that offer players little freedom, like Dragon’s Lair. This arcade game from 1983 invited the impression that players would be controlling the actions of a cartoon character—that players would have a great deal of autonomy in the experience (Figure 4-5). Instead, the gameplay consisted of a predetermined set of joystick movements that the player needed to execute at precise times to keep the prerendered video running. The game actually offered no control over how the events unfolded at all—a disappointment, considering that control of the experience is one of the greatest strengths video games have over other entertainment media.

Figure 4-5. Dragon’s Lair gave the false impression that players could control the actions of a cartoon character.

Games built to appeal to autonomy as a motivation will impose the fewest possible restrictions on the player’s freedom. Players should be, in a sense, on their own to determine what they do in the game, and not pushed along by the designer’s hand. They should have the latitude to pursue multiple different objectives, explore the game world at their own pace, and employ multiple strategies to solve problems. Players may be able to assume different personas for their characters, as villains or heroes, fighters or healers. It’s helpful, too, if players can skip elements of the game that don’t interest them, and focus on the portions that they find most compelling.

Most people have experienced the joy of a job well done. It can come in ways both large and small, from launching an exceptional user interface to perfectly executing parallel parking. There’s an intrinsic pleasure in the feeling of being really good at something. The satisfaction we get from conquering these challenges only grows more acute with greater levels of difficulty.

Psychologist Carol Dweck argues that people are sometimes driven by the desire to feel that they’re competent actors within an activity, which she calls a “mastery orientation.”[22] People with a mastery orientation care about developing their skills and abilities, and take a genuine interest in activities for their own sake.

Games that offer players a feeling of competence may become very difficult indeed, although excessive difficulty can also diminish the appeal of a game to casual players and limit its potential audience. A common strategy for avoiding this problem is to allow players to select the level of difficulty that they want for a session of play. Another effective tactic is to award players special capabilities, items, or features when they complete optional difficult goals as a means of acknowledging their superior skill, cunning, or dedication.

Games that cater to the need for competence can also benefit by offering opportunities to learn and practice in a low-stakes environment inside the game, giving all players the chance to acquire the skills they need to operate competently in the game. This setup is common in fighting games like Tekken and Virtua Fighter, which coach the player through the elaborate key presses required to execute different martial-arts attacks and defenses.

The drive to hit, kick, blow up, demolish, destroy, and dominate underlies many modern blockbuster games. While it may not be our most attractive side, the consensus among psychologists is that we humans are by nature an aggressive lot.[23] The stresses of everyday life can heighten our aggressive impulses, and video games can offer cathartic relief from these pent-up tensions through scenarios that aren’t available in the real world. The conflict in a game can serve as a surrogate for the common struggles of living.

There are entire genres that allow game players to explore different flavors of catharsis, such as fighting games, shooters, and vehicular combat (cars with guns on them—yeah!). It’s worth cautioning that these games tend to have much larger male than female audiences, and that violent themes can be very alienating to many people.

But games that satisfy the desire for catharsis don’t necessarily need to be centered on bloodlust. Games can instead provide catharsis in more abstract ways. For example, defeating someone in a chess match is exercising a form of aggression toward an opponent, which is all the more pronounced by the gradual and humiliating attrition of the losing player’s pieces. Ruthlessness is a great quality in a chess player.

Games designed to provide cathartic experiences should have a clear sense of winning and losing. Winning players shouldn’t be denied the opportunity to gloat just because it’s uncouth. Many games also give players access to a broad variety of powers that expand with time, inviting the feeling that they’re growing stronger through their experience with the game. The Mark of Kri, for example, builds tension throughout the game by giving players access to weapons that each have distinct strengths and drawbacks in their range, power, or agility. In the final act players earn a hefty battle-axe that has all three advantages and no drawbacks, granting players the cathartic pleasure of dispatching scores of enemies as though they were cutting through butter (Figure 4-6).

Many people dream of doing great things in life but find themselves constrained by circumstances. Only a small number of people will be recruited into the NFL, make a great film, or fly into space. To pursue a dream seriously, people often need to take great personal risks. Abraham Maslow posited that we pursue such goals only after our basic physical needs are met,[24] but this is not always true. Some people are willing to give up steady work to start their own business or move to an expensive city to seek stardom. The real peril in these situations is that the person taking such an enormous risk might not succeed. Failure, then, not only robs people of their dreams, but can also diminish their basic quality of life. Some people embrace such risks, but for many more they are an impassable barrier to trying. People can, however, still crave the experience of personal glory.

Games can offer people great accomplishment while putting them at no real personal risk. A key to the appeal of such games is that players know it’s at least possible to succeed (though it may be extremely difficult). Everyone has the potential to achieve greatness. Furthermore, people have the prospect of succeeding without taking on the kinds of risks that could cost them their basic sense of security.

Games that indulge people’s need for accomplishment offer grand fantasies and great peril: saving the world, medaling at the Olympics, or rescuing the president from the deadly cyborg ninjas. They also celebrate the moment of victory, showing the player standing atop an Olympic rostrum or being awarded the Medal of Honor. Some games allow players to record and save their winning runs so they can later replay them and relive their moment of glory.

Earlier, I briefly mentioned Carol Dweck’s theory of motivation driven by a mastery orientation. This is only half of what she had to say on the subject. The other part of the theory holds that some people have a “performance orientation”: they do something because they want others to have a favorable impression of them. This might mean that you want people to see you as smart, capable, or cool. People with a performance orientation are concerned with preserving or improving their social image.

This is often an important reason why children play games, and why they select the same titles their friends are playing. Pokémon allows players to differentiate themselves from one another by the monsters they’ve captured. Players can then pit their monsters against one another in battles, offering a kind of social preeminence to skilled players. For many kids, these games can become entangled with their feelings of self-esteem.

Although most grown-ups don’t take games quite so seriously, social image is nonetheless an important motivator for many people, and there are common patterns of design that cater to that drive. Massively multiplayer online games like World of Warcraft allow players to compare themselves to one another by level, and friends playing FarmVille can visit one another’s estates to see how many items they’ve been able to acquire. Such devices allow players to show off their skill, dedication, or seniority.

For players to feel that the social currency is meaningful, other people must have a sufficiently active interest in the game. So the game itself needs to be popular, preferably among people the player knows. Catering to the motivation of social image may be easier with games designed specifically for groups of people who know each other, such as coworkers or families, than in games designed for a general audience.

Most games are played with other people. Monopoly, baseball, and poker were all designed as games that require more than one person to play. But video games can provide artificial competition, allowing players to experience these pastimes without the involvement of other human beings.

For many people, though, the social experience of Monopoly, baseball, and poker has always been an enormous part of their appeal.[25] Indeed, socializing with other people is often the point, while the game itself is just a pretext that gives people an excuse to get together. Single-player video games can indulge a human fascination with gameplay itself, but for some people that misses the rationale for playing in the first place.

Game designers aren’t blind to all this, and they’ve devised many ways to build social interaction into the video game experience. Since as far back as 1972, home game consoles have been built to accommodate multiple controllers, allowing players to play side by side in real time. This living-room experience remains an important way to play video games today, as demonstrated by games like Rock Band. Online multiplayer games like World of Warcraft have allowed people to forge friendships online, interacting in real time but disconnected space. Social networking games like FarmVille and Mafia Wars have created new ways for friends to interact and maintain their relationships, even though they’re disconnected from one another in both space and time. The game world serves as the common place of convergence.

Games can better appeal to the human need for social interaction when players have a stronger sense of one another’s presence. Avatars help people visualize one another. In-game chat allows them to speak to one another. Guilds and friend lists help them stay connected.

Note, however, that you should be cautious when facilitating free-form interaction between people in online games, because it can become an avenue for offensive behavior or exploitation. Especially in games designed specifically for children, consider protections such as allowing players to chat only by choosing from a list of predetermined phrases.

Although many games have themes of destruction, many others appeal to the human desire to create. Some games provide players with no objective other than to showcase their creativity and imagination.

Simulation games like SimCity appeal to the innate delight in constructing things by letting players build their own living societies from the ground up. The Sims allows players to create their own people, build houses for them to occupy, and spin stories around their lives. Games like LittleBigPlanet and ModNation Racers give players tools to build their own games and then post them online for other people to play (Figure 4-7).

Games appealing to creative instincts benefit by giving players a broad palette from which to design. Players should have enough latitude to create things that are recognizably distinct from other people’s work. This flexibility needs to be balanced against ease of use, because creative people want to create, not get bogged down in negotiating the user interface.

Figure 4-7. An intuitive user interface allows players to easily build their own racecourses and share them online in ModNation Racers.

These games also benefit by giving players ways to showcase their creative work. Many games allow players to post their games to an online gallery, where other people can visit their creations and even play through the game environments they’ve built. Other games provide a way for players to snap “photographs” from the game, so that they can build memories of the things they’ve created and carry keepsakes of the experience with them into the future.

Play is a highly individual experience. There are some universal reasons why people play video games, but there are many more idiosyncratic motivations than anyone can fully account for. I’ve played various games because I think they have artistic merit, because I have a nostalgic connection to a series, or because I’m writing a book about them. For every motivation, there’s a design opportunity. To create a successful experience, a designer needs to begin by asking, “Why would someone want to play this game?”

Designers who want to build games or game-like experiences need to have a more robust understanding of why people play games other than simply to have some fun. That rationale is too vague to help us make better decisions about how to design games that people will be more likely to enjoy. Understanding the specific motivations that drive people to drop everything, sit down, and spend valuable time playing a game makes it more likely that designers will create an experience that players will describe as fun and worthwhile.

[18] Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1998). Flow: The psychology of everyday experience. London, England: Harper Perennial, pp. 39–42.

[19] Chen, J. (2007). Flow in games (and everything else). Communications of the ACM, 50(4), 31–34.

[20] Madigan, J. (2010, July 27). The psychology of immersion in video games [Web log post]. Retrieved from www.psychologyofgames.com/2010/07/27/the-psychology-of-immersion-in-video-games.

[21] Ryan, R., Rigby, C. S., & Przybylski, A. (2006). The motivational pull of video games: A self-determination theory approach. Motivation and Emotion, 30, 347–363.

[22] Dweck, C. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. American Psychologist, 41, 1040–1048.

[23] Gleitman, H., Gross, J., & Reisberg, D. (2011). Psychology (8th ed.). New York, NY: W. W. Norton, pp. 473–478.

[24] Maslow, A. (1954). Motivation and personality. New York, NY: Harper.

[25] Salen, K., & Zimmerman, E. (2004). The rules of play: Game design fundamentals. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, p. 462.