Games for action ask people to adopt specific behaviors. Games for learning are designed to teach players something about the world. But persuasive games go a step further than either of these and try to convince people that they should adopt a different point of view. There’s an unavoidable overlap among these three—the intended result of persuasion is often some action, and persuasion will always involve some degree of education—but persuasive games are distinct in that they are designed with the intent to effect meaningful change in players’ beliefs.

I’m guessing that, for many readers, the idea that games should be used as instruments of persuasion will be the most challenging assertion that I make in this book. Are games really suited to the job of influencing people to vote for a particular candidate, eat healthier foods, or use public transportation? Isn’t persuasion serious business?

Games have the ability to command high levels of engagement, and the best opportunities to get a message across come when people are really paying close attention. If UX designers close themselves off to the possibility of using games to persuade, we might miss the chance to get a message across at the very time when people would be most receptive to it.

But even if the opportunity is there, do games really have the potential to capitalize on it? This chapter will describe why, because of their unique qualities, games may actually be an ideal way to persuade.

The notion of persuasive games actually isn’t new at all. Game makers have long recognized that their products could serve as powerful instruments of persuasion.

In the 19th century, many games were designed to promote moral messages. Some of these titles remain familiar today.

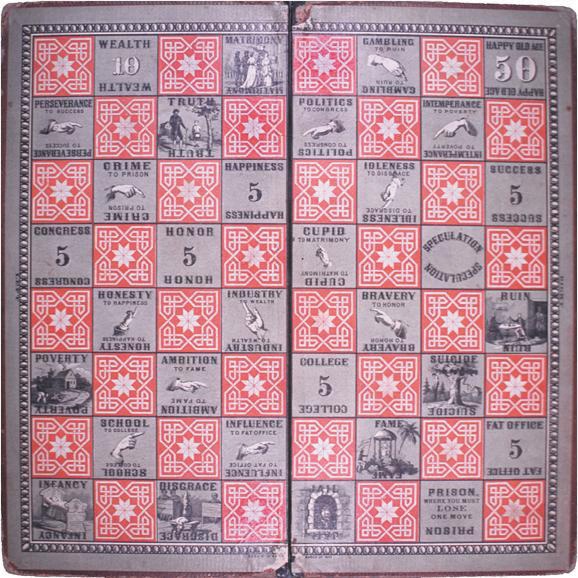

The first game that Milton Bradley (the man himself) ever published was intended to teach children the connections between life choices and their consequences (Figure 13-1). In The Checkered Game of Life, players move around a board and encounter virtues such as honesty, industry, and bravery, as well as vices such as gambling, intemperance, and idleness. These in turn move the player either to positive life outcomes such as happiness, honor, and wealth, or to ruin, disgrace, and suicide (children’s games could be a bit grim in 1860). The modern-day Game of Life has changed substantially but retains some traits of the original, such as the spinner used in place of dice, which at the time were associated with the vice of gambling.[52]

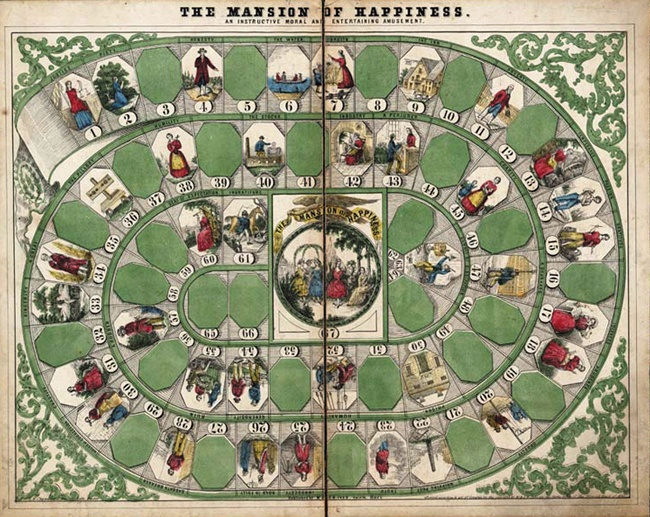

Similar games popular in the 19th century, such as The Mansion of Happiness (Figure 13-2), promoted Christian moral values; other titles, such as the Game of the District Messenger Boy, advanced capitalist ideals.

More recently, growing attention has been paid to how video games can make a positive difference in the world. The annual Games for Change conference hosts a festival of games intended to help combat a broad variety of social concerns, including poverty, human rights, and global conflict.

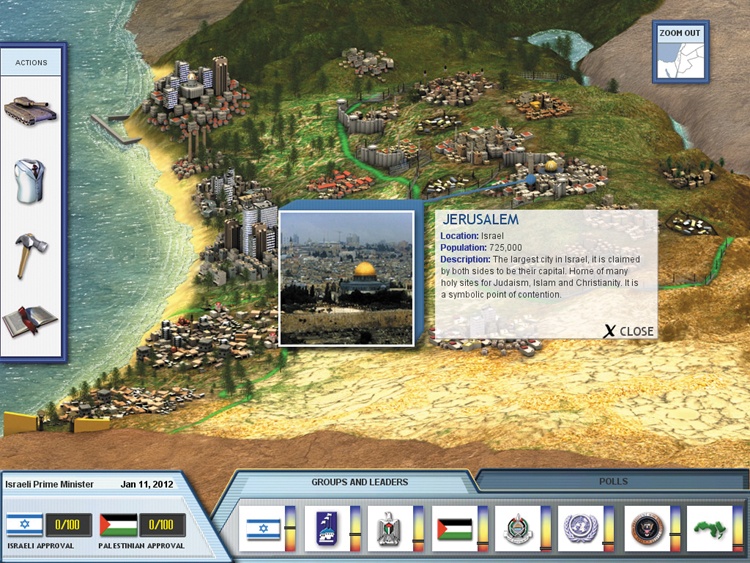

Among the games that have been featured at the festival is PeaceMaker, which was designed to underscore the complexities of politics in the Middle East (Figure 13-3). Players take on the role of either the Israeli prime minister or the Palestinian president and make decisions in reaction to real events. Each decision prompts reactions from the public on each side, their leaders, and the international community. Meeting your goals while keeping the region from deteriorating into conflict is a key challenge of the game.

Figure 13-3. Painting a complex picture of conflict, Asi Burak’s PeaceMaker was designed to persuade players that simple resolutions don’t exist.

Asi Burak, the lead designer, intended PeaceMaker to persuade players that peace in the Middle East is possible, if very challenging. In an interview he said, “We wanted to take one of the most serious problems in the world, and show that video games can put it in context for people more successfully than traditional media.”[53] By allowing players to assume the role of either side, the game encourages them to empathize with the pragmatic difficulties their respective leaders face in trying to effect an equitable resolution.

Federal agencies of the US government have also taken notice of game design and begun issuing grants and other incentives to foster the growth of persuasive games with positive social objectives. In 2010, the Apps for Healthy Kids contest, sponsored by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) and Michelle Obama’s “Let’s Move!” campaign, challenged game makers to find ways to persuade children to eat healthier. The contest produced 63 unique entries.

Although the persuasive-game sector is tiny in comparison to the entertainment game industry, it has nonetheless emerged as an important subfield and generated serious interest.

Game theorist Ian Bogost uses the term “procedural rhetoric” to describe how games influence people. He argues that games are a form of communication and, as with public oratory, written language, and visual media, they can be used to communicate persuasively.[54] But Bogost further argues that the ability of computers to execute rules—what he calls their “procedurality”—makes them unique as a communications medium. In this regard, they are distinct from books, TV, and stone tablets (especially stone tablets), which express their meaning overtly. In a procedural medium, meaning is communicated through participation. It is through the process of interacting with a computer program that people activate and perceive the procedural rhetoric.

There are also noncomputerized ways to express an idea procedurally. In 1999, the Kansas State Board of Education voted to remove the theory of evolution from the state’s science standards. Faced with hostility toward teaching evolution overtly in the classroom, high school biology teacher Al Frisby took to teaching it procedurally instead, through a game.

Frisby had his students, acting like predators, hunt through grass to find different-colored toothpicks, and then pick them up using either forks or spoons. Through this game, he persuaded his students that green toothpicks had a higher likelihood of survival than red toothpicks, and that the predator students outfitted with spoons were more likely to be able to catch their prey than those carrying forks. This exercise allowed students to discover the core tenets of natural selection through gameplay. That’s procedural rhetoric.[55]

To be effective at persuading people, games must be able to contain and impart meaning to their players. We often don’t think about games in this way, but in fact meaning is communicated in every game. Understanding the game’s meaning is a part of understanding how to play the game. If play weren’t meaningful, we wouldn’t be terribly interested in it in the first place.[56] Meaning gives play a purpose and makes procedural rhetoric possible.

But just because games have meaning doesn’t necessarily mean they have ambitions to persuade us about anything in particular. In the vast majority of games, the messages communicated through play are simply about the game itself, especially about what you need to do to win. We can find such self-referential messages scattered throughout games that are familiar to all of us.

Parker Brothers’ Monopoly is a game rich with meaning, conveying a number of messages to its players. None of these are written in the instruction manual or explicitly stated in any of the game’s materials. Instead, they are communicated through the process of playing the game. The game’s messages include:

Own a lot of a few things and a little of many things. Players get the best return on their investment by building houses on a small number of properties. However, owning several individual properties from the many other colors on the board keeps other players from obtaining their own monopolies and pursuing the same strategy.

Be willing to make big sacrifices to obtain the things you need the most. It’s often worth mortgaging or selling every property you own if it allows you to afford a single property that you need to execute your strategy.

Owning all the railroads provides the most reliable source of income. The railroads are the only properties with four spaces on the board, so opponents are more likely to land on them and pay you rent. You also don’t need to build houses on the railroads to yield greater returns. They consistently pay good dividends.

Especially as you become a skilled player, these messages become increasingly apparent as they lead again and again to winning. People playing the game independently of one another will eventually come to the same conclusions, so these are real and consistent communications.

In the modern form of the game, these messages are about the Monopoly game itself and not anything broader. That’s especially clear in the railroad strategy; you wouldn’t take Monopoly’s lesson about railroads as sound financial advice, because there’s no expectation that it holds true in the real world. The first two messages might happen to be true of other things in life, but if they are, then it’s only by coincidence. Today’s game of Monopoly has no agenda to sway people’s opinions about anything beyond how to win at Monopoly.

Few games are designed to resemble real life so much as The Sims. Its virtual people eat, sleep, work, play, cry, laugh, fight, and get it on just like the rest of us.

The Sims also communicates abundant messages that, on the surface, sound like plausible life lessons, including:

All people need to spend the most time doing the things that really make them happy.

Time spent expanding your life skills pays off.

People should find mates with whom they share the most compatible personality traits.

The right material possessions can help people enjoy life more.

Neglecting others will damage relationships that you’ve worked hard to develop.

But at the same time, the game isn’t meant to effect any real change in the way its players live. The Sims comments on the way life is, but it has no agenda to suggest how life should be. It was designed to entertain us, not to transform us.

The fact that the messages in most games pertain only to the games themselves is a matter of choice. Designers may instead simply choose to make real-world affairs the subjects of their games, and to incorporate into the rules of play an explicit agenda to change how people think about these issues.

Earlier I made the case that the modern game of Monopoly has no agenda to influence its players’ thinking or actions. This is true enough of the version of the game sitting in your closet, which Parker Brothers brought to market in 1936. But Monopoly was derived from an earlier title called The Landlord’s Game, which was designed for the specific purpose of persuading its players.

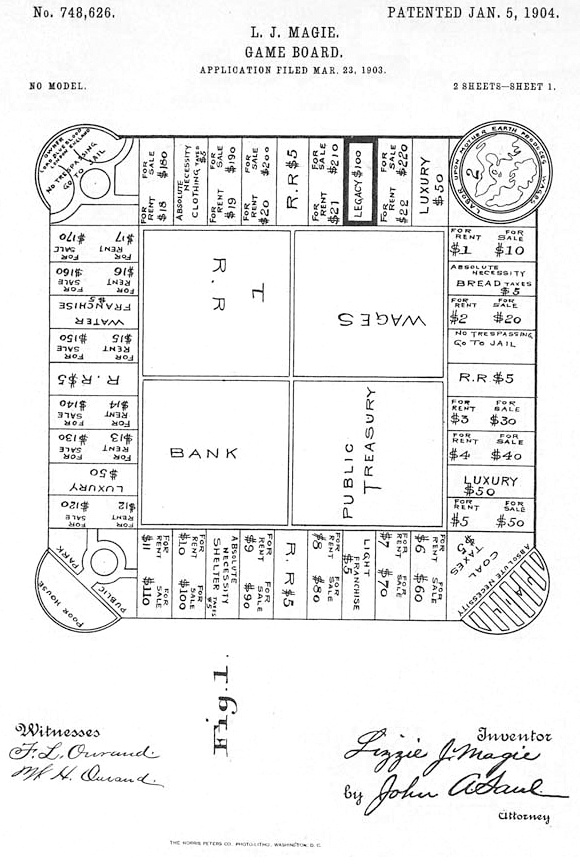

Lizzie Magie invented The Landlord’s Game around 1903 to demonstrate how rents paid on land generate disproportionate unearned wealth for property owners to the detriment of their tenants (Figure 13-4). She used the game format to promote the (now arcane) theories of economist Henry George, who advocated a single tax on land ownership to replace other forms of taxation.

Figure 13-4. It’s easy to see the modern game of Monopoly in Lizzie Magie’s 1904 patent for The Landlord Game, although its persuasive message has been removed.

The ideological mission of The Landlord’s Game is laid out plainly in Magie’s 1924 patent renewal, where she writes:

The object of the game is not only to afford amusement to the players, but to illustrate to them how under the present or prevailing system of land tenure, the landlord has an advantage over other enterprises and also how the single tax would discourage land speculation.[57]

This purpose is lost in the commercial version of the game we know today as Monopoly, which modified the rules, objectives, and game board substantially to strip out its original meaning.

The Landlord’s Game was in fact a model of a persuasive game: it used the gameplay itself to argue its point, and it was intended to convince people to think differently in the real world. This is the same basic method that UX designers can exploit today to build persuasive games that, in the right applications, can be more effective and compelling than the traditional means of argumentation we might otherwise rely on.

How can we best take advantage of the capacity of games to change people’s minds? I propose a few guidelines that will help you capture the key characteristics of effective persuasive games.

You need to know what you want your game to say, and what you want its players to do or to believe. Examining these questions is the first and most important step toward integrating a persuasive message into your game.

Starting from this point focuses the design so that you can select game elements for their ability to directly support that argument. A well-defined message also helps control the scope of the design by allowing you to recognize digressive game mechanics. These can become a real problem both by muddying the message and by tying up your design and development resources. Dropping problematic elements of the design will allow the game to communicate its core message more efficiently, while keeping your costs down.

Because this step is so important, it’s worth making sure you do it the right way. Observe a few best practices when defining your core message.

You will need to refer back to the message frequently to keep the design disciplined and to remind yourself of what you want to achieve. If the message isn’t written down, it will be easy to forget what you’re trying to accomplish and let the design drift. So if your team is going to work in a dedicated space, post the message on the wall so that everyone always knows where it is and can easily refer to it to stay on track.

Author your message using the most precise language available. A vaguely defined message will lead to an uninteresting and unconvincing game experience.

Suppose, for example, that you’re designing a game intended to persuade people to invest in mutual funds. If your message is defined as just “Investing money is a good thing,” the resulting game mechanic might simply have players adding money to an account that delivers a fixed rate of return. Players will learn little new information about the way the world really works, and they’ll have little basis to reflect on their own investment habits.

If instead your message says, “You should invest in mutual funds instead of individual stocks because they can provide reliable returns over the long term without exposing you to too much risk,” you can build a much more interesting game with a greater capacity to change people’s minds.

If you’re working with a team of designers or creating the game for a client, now is the time to make sure everyone is committed to the approach. Because the game will be built around the precise phrasing of the core message, this is the best opportunity to orient the entire project in the right direction. If significant changes were to be made to the message at a later point, they could require a radical shift in the design or put the entire project at risk. So shop the message with the other people involved in the project, and modify it as needed to gain consensus. If key decision makers hold the purse strings, get them to sign off on the core message.

As tempting as it may be, don’t jump too far into the fine details of design until the core message is done. Resisting the urge to flesh out the design can be hard, because you might feel as if you’re not moving forward. Often we have a picture in our heads of what the experience will be, and we are enthusiastic about turning it into reality. But there’s a real danger of overcommitting yourself to the wrong design by taking off before you know where you’re headed. And the process of finalizing the core message really won’t take that long. So sit back, chillax, and take satisfaction in the fact that you’re starting out on the right foot.

The competitive dynamic of games drives players to find the most efficient ways to win. If the best strategies that the players can adopt are directly tied to the core message, then players’ behavior will tend toward the logical conclusion you want them to draw.

The process of playing the game, then, serves an argument for the truthfulness of its message. Rather than directly asserting that the message is true, a game can require players to adopt the core message as a working hypothesis and use the gameplay to prove to themselves that it’s true. To succeed, the players need to buy into the game’s point of view. By allowing players to participate in the argument, you can build a more effective rhetoric.

Suppose your game carried a message about fire safety and was meant to convince people to position fire alarms and extinguishers at key places in the home. You would then arrange the dynamics of the game so that buying sufficient home safety equipment and installing it in those particular places resulted in the best possible outcome, whereas worse positioning resulted in progressively poorer outcomes. In executing the game’s simulation, winning players would inevitably move toward the ideal installation.

Imagine that a racing game offers players the choice of two cars: a fast one and a slow one. Aside from their speed, the two cars are exactly the same. Which one would you pick? Winning this game would feel distinctly unfulfilling because there are no decisions to weigh. Players would simply pick the unambiguously better car.

Games with these kinds of simplistic choices create no opportunities for players to learn. Ian Bogost writes that for people to be persuaded, they “must have had the opportunity to deliberate about an action or belief that they have chosen to perform or adopt.”[58] This deliberative process allows people to form a rationale for why they should or shouldn’t do something.

To change people’s thinking, persuasive games need to give players meaningful choices. It sounds weird, but there has to be some advantage to making the wrong choice, just as there are advantages to the right choice. Suppose that, in the preceding example, the fast car takes greater damage than the slow car. Depending on the number of opportunities the player has to take damage in the game, the slow car could actually be the better choice. This design could become the basis for a game that would promote both the physical safety of cars and more cautious driving habits.

One of the greatest persuasive assets of computer games is their capacity to mimic the conditions of the real world. Their “procedurality,” to use Bogost’s term, allows games to run complex simulations efficiently. Although simulations must always be approximations of reality, they can be sufficiently realistic to give the game’s embedded arguments credibility.

For example, a game could easily be built to simulate the environmental effects of invasive species. Real ecosystems are far too complex for any computer to fully replicate, but the essential relationships among a few key plants, animals, and their rough ecological conditions can be demonstrated with enough fidelity for people to accept them as credible.

It’s important, however, that the game adhere to reality in every way that really counts, and that it not make unrealistic leaps of logic. If zebra mussels kill sea otters by crowding out their native food source, the game will be believable. If they kill the otters by shooting them with laser blasters, it won’t. Mistakes like this sacrifice a key advantage of working in a procedural medium in the first place.

Games give designers the opportunity to convince people by allowing players to discover things on their own. Discovery is an especially potent way to persuade through games because it gives players a feeling of ownership of the insight they’ve uncovered. By giving players the space to experiment with many different ways of doing things, you can invite them to think critically about the relative merits of those different choices, and reflect creatively on how things could be done better.

Suppose you want to design a game that promotes a deeper understanding of the advantages and drawbacks of different energy sources. You might run it as a city simulation, in which players need to build a metropolis and construct power plants that can keep pace with the demands of its growing population. To enable self-directed discovery, players may be able to invest in a variety of energy sources—coal, natural gas, solar, wind, hydroelectric, and nuclear. The differentiating attributes of each would include setup costs, maintenance costs, output, reliability, consumption of fossil fuels, and pollution. By experimenting with several different energy sources in the game, players can build an individual assessment of the merits of each.

Fitter Critters, a game created by my team at Megazoid Games for the Apps for Healthy Kids contest, was designed from the ground up to serve as a persuasive game. The contest was intended to produce games that would help solve the problem of childhood obesity by transforming kids’ attitudes toward nutrition. This is a very tough nut to crack, because eating habits are deeply rooted in culture. We had to create something that stood as a credible game experience, but that was also persuasive enough to change the choices players make about their diets in the real world.

When we sat down to design Fitter Critters, we had a vague sense that we wanted to create a virtual-pet game, but we didn’t really know how it should work. We lacked direction, and the design was sputtering and formless. We needed a core message that could serve as the foundation for the game’s structure, integrate the contest’s objective into the game’s design, and get our creative energies flowing.

So we took some time to write down what we wanted the game to say (Figure 13-5), and came up with a two-point message:

Eating a varied diet rich in vegetables, fruit, and whole grains leads to a better quality of life.

Eating junk food may have short-term advantages, but in the long run it’s not worth the negative health consequences.

Figure 13-5. An early paper prototype of Fitter Critters. Many elements changed, but the core message (shown here at upper left) remained constant throughout.

Now that we had something to work with, the basic game mechanics quickly snapped into place:

Players need to shop for their virtual pets’ food and feed them on a daily basis.

A set of scales shows a pet’s progress toward daily nutritional needs such as vegetables and whole grains, as well as limits on fats and added sugar (Figure 13-6).

If players consistently make better nutritional choices, their pets will be healthier.

Healthy pets will enjoy the benefits of a strong body and lead more prosperous lives.

Figure 13-6. Every day players need to select foods that will fill all of the green bars (representing positive nutritional attributes) without filling either of their red bars (representing fat and added sugar).

Having a clearly articulated core message also helped us decide which proposed gameplay ideas to drop. For example, one of our early ideas had the game tracking the pet’s fullness. Players could feed the pet until its fullness bar reached its maximum, at which point it would reject any more food for a few hours. It seemed like a logical design choice because it would make the game more realistic. But the concept had no rhetorical punch. The fact that you were full had nothing to do with whether you’d eaten healthy food or junk food. You were just full. By dropping fullness, we ended up with a more focused design and saved ourselves valuable development time.

We built a direct relationship between the core message and the ideal strategy that players had to adopt to succeed in the game. If a player’s pet is consistently served more nutritious foods, then it will realize a number of positive outcomes:

It will make more money at work. Each day the pet goes off to work while the player isn’t using the game. Its earning potential is determined by both its energy level and its overall health, so keeping the critter fitter nets the player more money.

It will win more games. Players can enter their critters into sports competitions (Figure 13-7). The probability of winning and gaining a $50 prize is determined by the critter’s health and total body fat.

It will get sick less often. Each day the server decides whether the pet will fall ill, using an algorithm that decreases the likelihood of illness with increasing health. Sick pets can’t go to work and can’t play sports.

It will live large. Money earned from work and sports prizes can be used not only to buy more food but to decorate the pet’s house, introducing collection and customization dynamics into the game.

Figure 13-7. Players are more likely to win sports competitions if they’ve been feeding their critter well. Players earn game money for winning, which enables additional rewards.

This design constitutes a laddered reward system, where one type of success leads to another. A lavish pet lifestyle comes from healthier living, and healthier living comes from choices about food—positioning the contest’s objective as the inescapable foundation of success. This message is never stated explicitly anywhere in the game, but emerges from the process of playing.

If healthy food offered only benefits and junk food only drawbacks, then the game would present no real choice at all. Players would always pick the healthy food because there would be no reason to consider anything else.

In Fitter Critters, there are two built-in advantages to consuming high-calorie foods. First, your pet needs to have a certain minimum level of energy to participate in the sports games. Calorie-rich foods fill up your pet’s energy bar quickly, giving it immediate energy. Second, a higher energy level also allows the critter to earn more money from working each day (although this benefit caps at 2,000 calories). That bacon double cheeseburger offers a fast track to higher energy levels.

Of course, unhealthy food choices also have important consequences. Exceeding daily limits on calories, fat, or sugar lowers the critter’s health over time. The critter will also develop a taste for junk food and start to reject healthier choices, making it harder to get it back to a healthy lifestyle.

Fitter Critters’ design gives players a meaningful choice. It also supports the second part of the game’s core message: the short-term advantages of eating junk food are outweighed by the damage done to health and quality of life.

All of the nutrition data for the 675 food items in Fitter Critters comes from a data set maintained by the USDA. Moreover, the minimum number of servings the pet needs to meet and its daily limits on fat, sugar, and calories are based on the consumption guidelines set by the USDA for children in the players’ age group.

For example, the number of slices of whole wheat bread the player has to feed the pet to fill its whole-grains bar is the same number of slices a child would need to consume on a daily basis in the real world. The amount of healthy foods needed can be surprisingly large, especially for children accustomed to poor eating habits. Managing intake for their pets on a daily basis gives players some sense of the proper proportions of vegetables, whole grains, proteins, dairy, and other foods they should be eating, as well as practice in selecting them.

More broadly, the game’s observance of actual food data and nutrition requirements lends its arguments credibility. If eating a single apple magically gave the pet super strength, the game would fail to impart a lesson that players could generalize to their own lives.

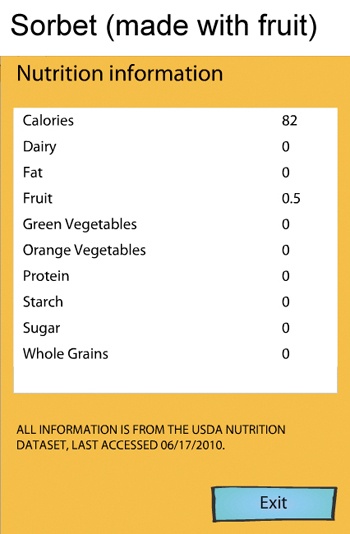

Fitter Critters creates multiple opportunities for players to learn lessons themselves. One of the key challenges in the game is to use nutrition labels to sift through the multitude of options at the grocery store to discover the foods that will most quickly fill the nutrition requirements while keeping fat and sugar as low as possible. In so doing, players efficiently learn the true nutritional merits and liabilities of different foods. For example, players can discover that sorbets are among the best dessert choices available, since they’re free of fat and added sugar and actually provide valuable servings of fruit (Figure 13-8).

Figure 13-8. Players need to learn to appraise the nutritional qualities of different foods in order to succeed in the game.

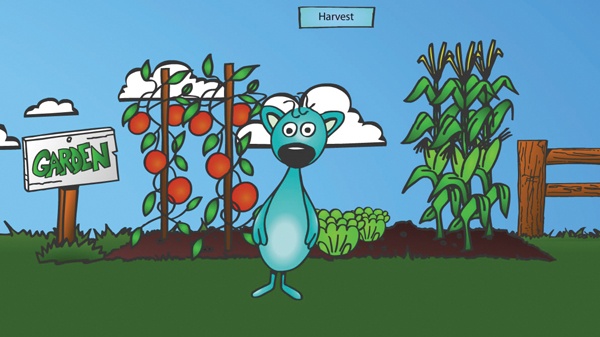

Players also discover the advantages of maintaining a garden and using it as a source of food (Figure 13-9). Harvesting food from the garden allows players to save money for other things (as in real life). Creating an optional resource like this that offers players an advantage if they choose to avail themselves of it is a great way to enable persuasion through discovery.

Figure 13-9. Players can discover the benefits of growing a garden to harvest their own fresh vegetables.

Finally, Fitter Critters lets players cook meals using the food in their refrigerator. A meal can be sold for up to a 500 percent profit, depending on the healthfulness of its ingredients. Although the reward isn’t realistic, it encourages players to think creatively about how nutritious foods could be combined and enjoyed together, while giving tangible value to their combined nutritional attributes.

All of these discovery opportunities were designed to persuade children to think critically about dietary choices and, through their newly gained familiarity with nutrition, apply it in the real world.

Every medium has been exploited for its rhetorical capacity to persuade its audience. Public oratory, pamphlets, books, radio, TV, film, billboards, bumper stickers, and websites have all served as channels for popular movements, entreaties, political campaigns, and propaganda. Each also offers unique strengths that can be applied to change people’s minds.

Games are no different, and UX designers can develop effective persuasive games by playing to the strengths of the format. Through their procedural structure, games are especially adept at demonstrating truths about complex systems and involving people in the process of persuading themselves.

[52] Lepore, J. (2007, May 21). The meaning of life. New Yorker, p. 38.

[53] Phone interview with the author, December 10, 2010.

[54] Bogost, I. (2007). Persuasive games. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, p. 3.

[55] Belluck, P. (2000, August 3). Evolution foes dealt a defeat in Kansas vote. New York Times.

[56] Salen, K., & Zimmerman, E. (2004). The rules of play: Game design fundamentals. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, p. 462.

[57] US Patent Office. (1924, September 23). Elizabeth Magie Phillips, of Washington, District of Columbia. Game board. Google Docs. Retrieved from www.google.com/patents/US1509312?printsec=abstract#v=onepage&q&f=false.

[58] Bogost, I. (2010, March 3). Persuasive games: Schell games. Gamasutra.com.