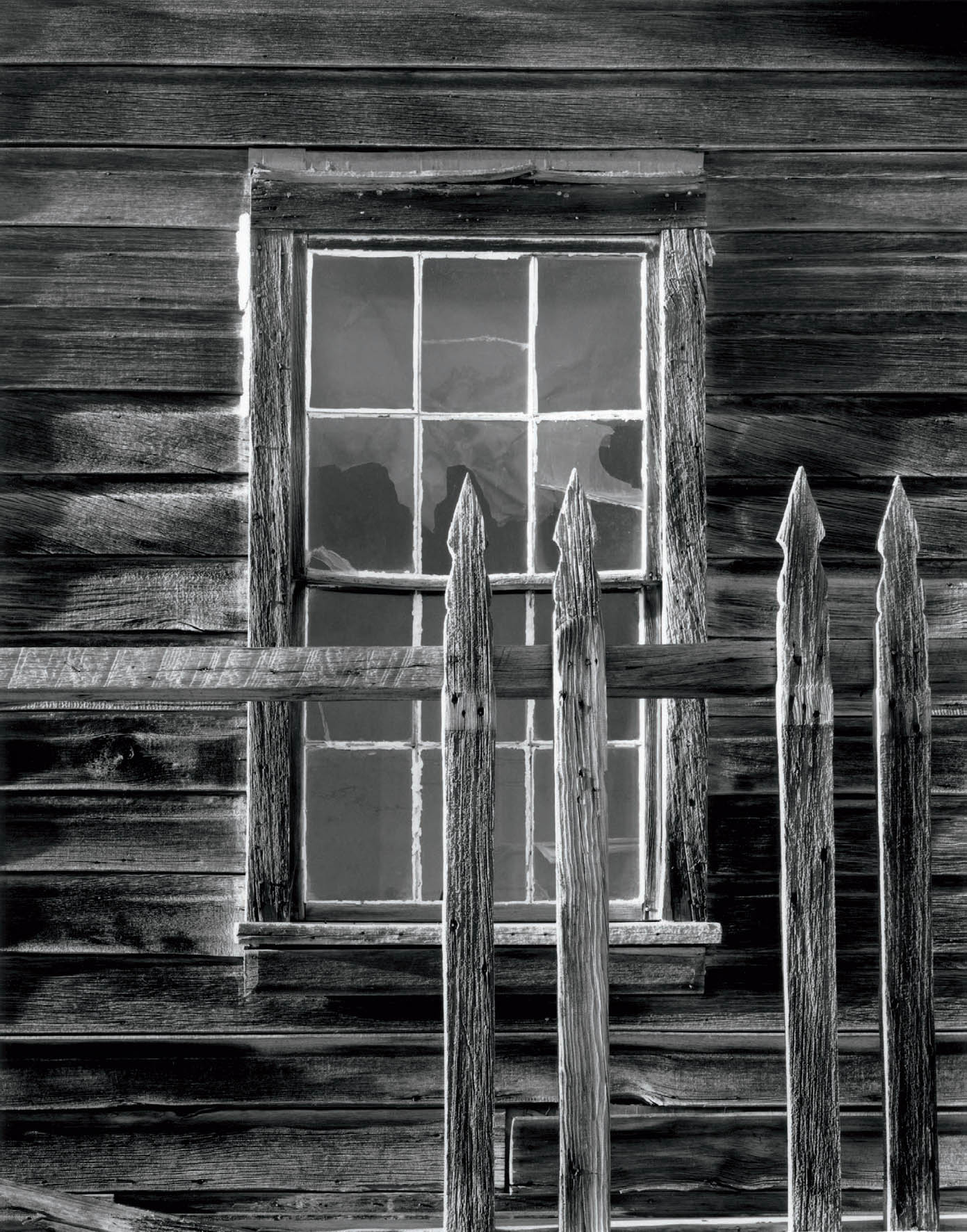

Figure 16-1: Picket Fence and Window, Bodie

This is the only image from a decade of photographing Bodie (1975–1985) that I felt had real lasting value. It’s a study of balanced asymmetry and meticulous camera placement. The window is slightly left of center to balance the pickets on the right, while the bright plaster patch at the upper left of the window completes the balance. The tip of the left picket is cradled within the dark portion of the window. The rectangular window spaces vary in size and tonality. Late afternoon sun from the left gives a tangible feeling of light hitting the rail, the pickets, and the house wall.

CHAPTER 16

Photographic Realism, Abstraction, and Art

![]()

IN THE LATE 1870S, BODIE, CALIFORNIA WAS A MINING TOWN of considerable importance, producing millions of dollars in gold and silver ore at the prices of its day. It was infamous for its bitter weather, brawls, and shootings. Its fortunes declined during the early 1880s as the mines were depleted. The last occupants moved away in 1940, eight years after a devastating fire destroyed most of the town. Today, Bodie is a California State Historical Monument with a cluster of remaining buildings spread over a square mile area.

I first visited Bodie in 1975 on a field trip during a photography workshop. I was immediately drawn to the weathered wood; decaying interiors with peeling, stained cloth wallpaper; and warped windows. I returned often, each time photographing details of wood and windows, portions of interiors, and other bits of the formerly occupied houses. The photographs were well composed and nicely printed. They had wonderful textures, strong lines and forms, good balance and contrast, and rich tonalities (figure 16-1).

But over time, I lost interest in these images. I couldn’t explain it; I just knew that they no longer meant much to me.

For years I questioned why my interest in those photographs disappeared. The photographs were design-oriented, emphasizing many of the elements of composition discussed in chapter 3. They weren’t truly abstract, but they weren’t straight realism, either. They fell into a category that Ansel Adams called “extractions,” a term he used in place of “abstractions” for small bits or pieces taken from the whole. I realized that wherever they were on the reality/abstraction spectrum was of little consequence. What was lacking was something I’ve previously called “inner conviction.” I was photographing details because I liked their contrasts, textures, lines, forms, balances, etc., but not because the subjects meant very much to me. I didn’t regard them as remnants of a rich or colorful history, or as anything else that could have imparted deeper meaning to them, but solely as present-day objects with interesting compositional attributes.

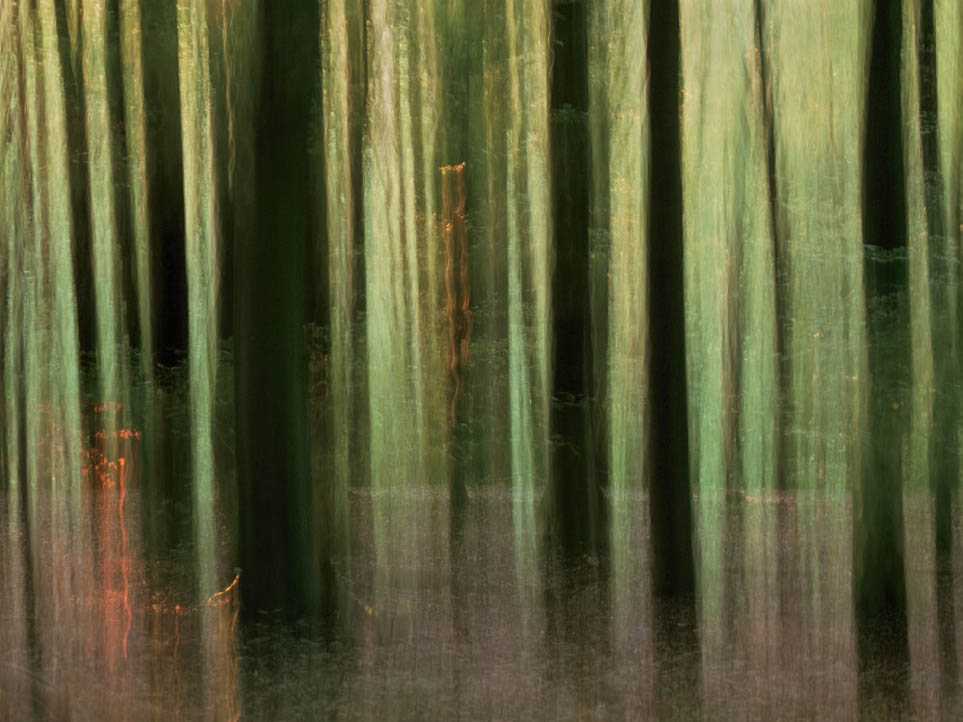

Figure 16-2: Forest at Sunset

Walking in a forest near Frankfurt, Germany in the early autumn as the sun was setting, I noticed a cluster of red leaves on a bush, with hints of other red and orange leaves close by. Holding my camera for a 1-second exposure, while gently turning it upward during the exposure, created a shower-curtain effect that pleased me far more than the straight image with no movement. Somehow, it seemed to say more to me about the forest, about the mysteries of the forest, and perhaps about the mysteries of life in general. Is it realism or abstraction or neither? More importantly does it move you, or say anything to you?

Yet, my questioning led me to thoughts about realism, abstraction, and art in general, and I know that my thoughts are still evolving today, and will continue to change as time goes by. Before delving into those thoughts, I’d like to define each of the terms contained in the chapter title: realism, abstraction, and art. The act of defining these terms is not only difficult, but also fraught with controversy. Just as chapter 2 started out with a definition of “composition,” I feel this chapter requires definitions in order to make the thoughts understandable (though not necessarily noncontroversial).

Realism is defined in my dictionary as an artistic representation felt to be visually accurate. It also is defined as an inclination toward literal truth and pragmatism.

Abstraction seems a bit more difficult to define. The dictionary refers to it as the act or process of separating the inherent qualities or properties of something from the actual physical object or concept to which they belong. Furthermore, the term abstract has several definitions. One states that it is a genre of art whose content depends solely on intrinsic form. Another states that something abstract is not easily understood or recognizable.

Surely there is a clear difference between realism and abstraction that emerges from these definitions. Realism deals with concrete objects in a recognizable, straightforward manner, whereas abstraction deals with the form or qualities of the object in a manner that may not be recognizable or understood (figures 16-2 and 16-3).

My photographs from Bodie were recognizably wood, window reflections, peeling wallpaper, etc., so they couldn’t be defined as abstract. They were visually accurate representations of the subjects, so they were close to realism, but they presented only bits of the scene, so they might have been slightly separated from pure realism. I was striving for something that went beyond reality, and for a while I believed I had achieved it. Slowly I came to recognize that an extraction of reality was not an abstraction, nor was it necessarily art. (I should also mention that I disagree with Ansel’s use of the word extract in place of abstract, for every photograph is an extract. There’s always more! You choose the part you want because you feel it’s cohesive, not because it’s “complete” in any real sense.)

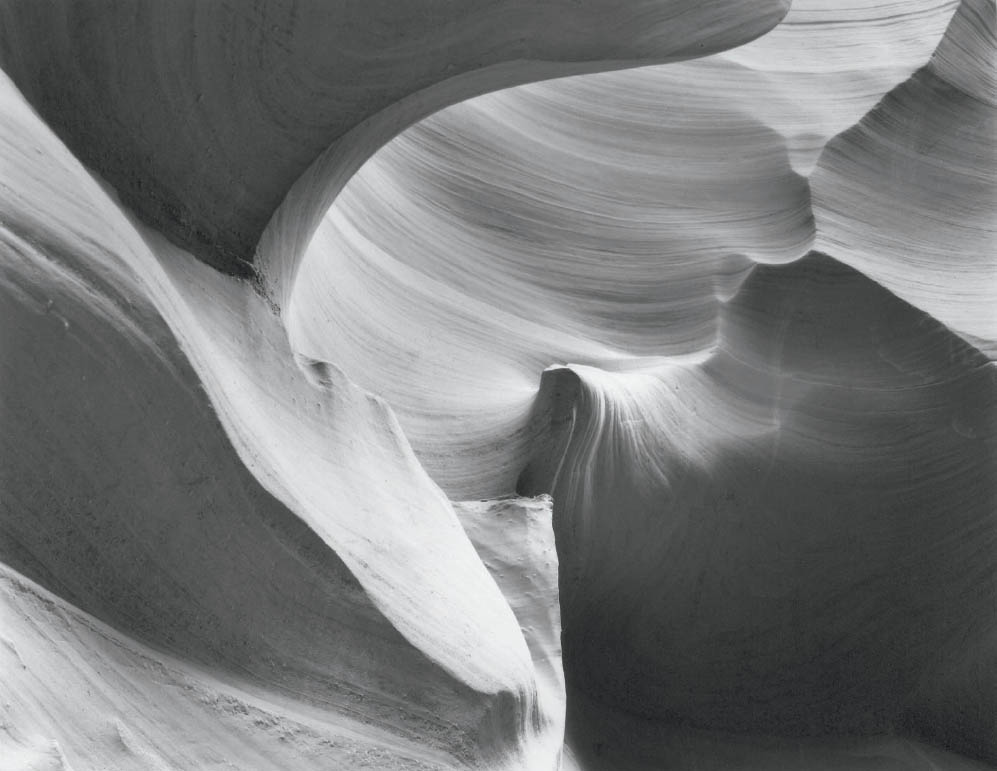

Figure 16-3: The Pinwheel, Spooky Gulch

Cosmologists tell us that planetary systems, such as our own solar system, are accretion disks of gases, dust, and rocks surrounding a star that coalesce over millions of years into planets and other smaller bodies that revolve around the star in fixed orbits. This photograph is my vision of a several-million-year time-lapse image as that swirling mass of unconsolidated debris becomes planets, moons, stars, and even whole galaxies.

Art is almost impossible to define, and any definition is controversial. Perhaps it’s akin to defining love. And perhaps the best thoughts about defining love (which apply equally to art) were penned by Oscar Hammerstein in the words to “Some Enchanted Evening” from the musical South Pacific:

Who can explain it?

Who can tell you why?

Fools give you reasons,

Wise men never try.

Undaunted by such sage advice, let’s try. Most definitions of art are either too broad or too narrow. Furthermore, we all have our own definitions that further complicate the process. The dictionary I consulted has a number of definitions that distill the word “art” down to the following: the conscious production of, or arrangement of, sounds, colors, forms, movements, or other elements in a manner that affects the sense of beauty. Or, alternately, the human creation of something that has form and beauty.

The dictionaries I referred to all used the word “beauty” several times in their definitions of art. I agree, for the most part, though I wonder if Picasso’s painting Guernica could be considered beautiful, though it surely is fine art to my way of thinking. I do feel that beauty is a part of art—a major part—and even Guernica has many touches of beauty, though its message is one of overwhelming terror, anguish, and pain. In contrast to Guernica, much so-called “art” produced today appears to be based purely on shock value, bearing few meaningful thoughts and fewer concessions to beauty. For me, whether a photograph I produce is realistic or abstract, I seek beauty in my images, primarily because I cannot imagine spending hours in the darkroom or computer in order to ultimately say, “Ahhh, now it finally looks like hell!”

Perhaps we could broadly call art an exploration or inquiry into our world, our emotions, and our fantasies. We could call it the creation of forms that express human feelings. Beauty is not central to these definitions, nor is it even required, but it certainly can be part of the mix . . . and I feel it’s a necessary component. These attempts at defining art allow each person to set his or her own limits.

We can begin with these definitions to see where photography fits into the world of art, and to explore some starting points for producing photographs that are worthy of the title “fine art.” Of course, the preceding chapters have all been devoted to this pursuit: We began by looking into ourselves to see what interests us and how we want to present those interests to others. Then we looked into the concept of composition, the elements of composition, and ways of composing a photograph to strengthen its message. Then we delved into the photographic controls that make compositional choices possible.

Photography as Fine Art

Had I spent more time analyzing my Bodie photographs from the perspective of the initial thoughts in the book (i.e., what they meant to me, and how I wanted to convey my thoughts), I would have had a clue to their shortcomings, for the truth was that I had little interest in Bodie beyond its superficial textures, lines, and forms. In other words, Bodie didn’t mean very much to me. I was never much interested in its tawdry history, nor did I see deep meaning in its textures and forms. Instead, I was photographing Bodie and analyzing my images purely from the compositional aspect, and they seemed pleasing from that point of view.

Alone or together, good composition and technical prowess don’t imply fine art. A great number of photographers can produce exquisite photographs that say nothing and inspire nobody. There is an abundance of photographs that are technically perfect but devoid of meaning. The painter Robert Henri said to his students, “I do not want to see how skillful you are—I am not interested in your skill. What do you get out of nature? Why did you paint this subject? What is life to you? What reasons and what principles have you found? What are your deductions? What projections have you made? What excitement, what pleasure do you get out of it? Your skill is the thing that least interests me.”

Although photography can stand on its own merits as an art form, let’s consider it not in isolation, but in relation to other arts. Each art form is unique both in the message it presents and in its manner of presentation. Each art form exerts influence on the others. In particular, photography has had an immense—almost traumatic—influence on painting, but the repercussions of this influence have also been hard on photography. These repercussions have been almost entirely overlooked or ignored by art and photography historians alike. I feel they are crucially important, and I shall delve into them.

Photography and Painting—Their Mutual Influence

Until photography came into widespread visibility in the mid-1800s, painting was largely representational—realistic, to use the definition above. Most fine paintings depicted people or scenes that were either realistic or idealistic, which means that real people were made to appear heroic for purposes of enhanced stature, or scenes were aggrandized beyond reality for much the same reason. Yet even those subjects were meant to be clearly identifiable, albeit exaggerated. Furthermore, even when subject matter was aggrandized or romanticized, the result was basically representational.

But with the spread of photography during the 1850s and 1860s, all that changed. Photography did a better job of depicting reality than painting did; it was simply more accurate. Only the quality of the lens limited its accuracy. Painting, as it evolved over thousands of years, was traumatized. By the 1870s, photography was making a huge impact on the world. Painting responded to this challenge by going through a sequence of well-known movements. Impressionism, postimpressionism, pointillism, fauvism, dadaism, surrealism, cubism, and others all followed one another (or occurred simultaneously) in an effort to anchor painting as an art once again. This effort has continued with other movements like modernism, abstract expressionism, post-modernism, Campbell’s soup-canism, pop art, op art, and perhaps in the future, mom-and-pop art.

But as painting changed drastically, primarily in response to photography, criticism changed along with it, and so did the definition of art. Each of the well-known movements in painting was roundly disparaged at its inception, but then was quickly incorporated into the fabric of art. As time went on, representational painting began to lose its significance as an art form. We can compare Gilbert Stuart’s portrait of George Washington, which has always been considered a work of reasonable artistic merit, with any painting of a recent president that is nothing more than another in a series of presidential paintings. It seems apparent that the great portraits of the masters—Rembrandt, Goya, Gainsborough, Reynolds, etc.—would be dismissed if done today because they are too representational, too real. By the same token, photography’s greatest asset, its visual accuracy—its innate realism—is also hard hit by this critical consensus. As photography forced painting to change, painting and criticism have forced the art world to change, and photography must respond to that change or be excluded from the world of art.

The inherent realism of photography is, in fact, somewhat of an obstacle to its acceptance as an art form in today’s milieu, even though that aspect makes its message so powerful. A compounding factor to this problem is the universal usage of photography: everybody has a camera (even the telephone in everyone’s pocket), therefore everybody is a photographer, but surely everybody is not an artist. There is the widespread feeling that photography is easy, as in Kodak’s original advertising slogan: “You snap the shutter, we do the rest.”

The preceding chapters indicate that expressive photography is not that easy after all. It requires immense effort—physical, emotional, and mental. But for all that effort, if the final image is to qualify as art, it must go beyond documentary realism. Even if a photograph stays within the realm of realism, it can have artistic merit if it’s endowed with a leap of imagination on the part of the photographer.

The image must have something that carries it beyond pure documentation. Perhaps there’s a heightened sensitivity—something deeply felt and revealed that offers the viewer deeper insights and understanding. Perhaps there’s a quality of mystery—something left unanswered that requires the viewer to investigate the print and think about it further. Or maybe there’s a surprise—something unexpected that leaves the viewer in wonder and amazement. Perhaps there’s a heightened sense of drama or grandeur or calm. Whatever the quality, it must be more than a scene, a person, or a thing

Some Personal Examples

Allow me to discuss several of my photographic pursuits over 45 years to illustrate the point I am trying to make.

My Bodie photographs from the mid-1970s into the 1980s failed because they were photographs of things—weathered wood, peeling wallpaper, partially collapsed structures, bubbled windows, etc. They were well executed, but they had no leap of imagination. Though I was drawn to Bodie, my interest was superficial and my photographs had no real base from which to leap. I should note that beginning in 2000, I began revisiting Bodie and producing new images that I feel are far more interesting and insightful than those produced earlier. Perhaps I started to see and feel Bodie differently.

The photographs I produced in the English cathedrals in 1980 and 1981 are different from my Bodie efforts. They, too, are pure realism: they are visually accurate (perhaps with slight aggrandizement through lens choices, choice of camera position, and camera movements), and they were created with a conscious attempt to avoid any form of abstraction. In cathedral after cathedral, I was struck by three aspects of the architecture: the musical interaction of light and forms; the mathematical feeling of infinity created by repeated columns, vaults, and arches; and the overwhelming grandeur. As my gaze ran up the columns into the arches and vaulting overhead, I saw music unfolding before my eyes. I felt awed and uplifted by the magnificent forms. They struck me as examples of what humanity can accomplish at its best. I attempted to depict these aspects through my photography (see figures 1-7, 3-1, 9-4, 14-4, and 14-10). I felt something beyond just an appreciation for good architecture and wonderful craftsmanship. Those elements added up to more in my mind; Bodie’s elements never did.

Another way for photography to reach the realm of art is through abstraction. Abstraction, as stated in the definition, immediately removes a photograph from the realm of documentary realism. Good photographic abstraction requires tremendous insight to be effective. Anybody can photograph small portions of things to produce an unrecognizable image, but only when the image has both compositional strength and that almost indefinable commodity known as internal conviction does it prove to be a work of art.

Abstraction implies imagery in which the inherent qualities of the subject matter are separate from the physical object. The Bodie photographs lacked this characteristic. By contrast, I feel my slit canyon photographs possess that quality. I often saw their swirling lines and forms as the paths traced by dust particles and gases that coalesce into planets, stars, or whole galaxies, and at other times as the heavenly bodies themselves, or as the forces that move these objects about. I attempted to strengthen that vision by eliminating any references to place, or to documentation of the canyons (figure 16-3).

The slit canyon photographs are virtually devoid of scale. Few people can tell with any certainty whether the area photographed is large or small, and most people who have expressed their perception of size to me have been woefully wrong. The uncertainty of scale is intentional on my part. I want the viewer to become involved in the flow of forms and forces, and in the cosmic aspect that I feel in the imagery—not to become involved in thoughts about the canyons themselves. I have consciously removed scale from the images by using lenses that distort scale and by excluding objects that would indicate size. In much the same way, few of the images have an easily identifiable orientation. It’s hard to say with certainty whether the view is straight ahead, up, or down (see figures 1-6, 3-6, and 3-12). In 1992, I started exploring the concept of combining two separate negatives to create a single, realistic-looking landscape. A foreground from one location could be combined with a background from another, with the negatives produced many years apart, and from different parts of the globe. I called them “ideal landscapes,” for the simple reason that if I had ever encountered the created landscape I would have photographed it. These cannot be considered realism because the resultant image doesn’t exist anywhere on earth (instead it exists in two separate places), nor can it be considered abstract because, in most cases, the images look quite realistic (figure 16-4). Are these images simply lies?

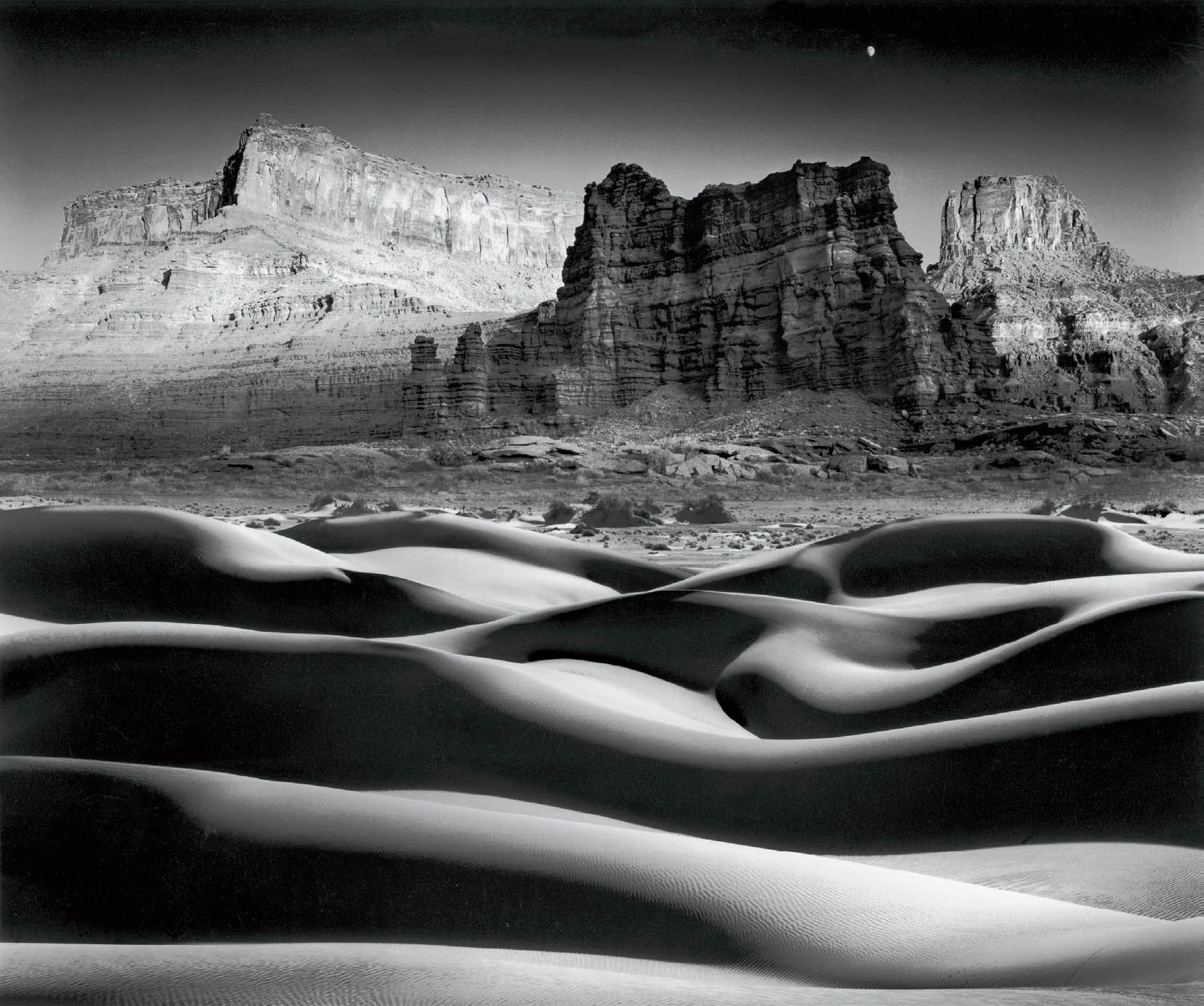

Figure 16-4: Moonrise Over Cliffs and Dunes

This was the first of my “ideal landscapes,” i.e., fictional landscapes derived from more than one negative. Neither of the component images—the dune image in Death Valley (exposed in 1976) nor the cliffs and butte in Utah (exposed in 1991)—was fully satisfying to me. Putting the components together made good artistic sense but initially drew extreme displeasure from viewers outraged by the “falseness” or “trickery” of it. Some still refuse to accept it; most have changed their minds and accept it as artistically valid.

When I first displayed these composite images, some viewers objected strenuously, claiming they were, indeed, lies. Interestingly most objectors had no qualms about the work of photographer Jerry Uelsmann, who creates surrealistic images made by combining many negatives. Apparently, the obvious surreal character of Uelsmann’s work contrasted with the apparent realism of mine. This difference immediately creates difficult questions about truth or deception in the mind of many viewers. But is a painting of any landscape realistic or a lie? What would be the reason to call a landscape photograph made from two separate negatives or two separate RAW files a lie when a landscape painting made with the easel set up in front of a magnificent landscape or in a studio is never considered a lie? It’s always looked upon as the imagination of the painter. My “ideal landscapes” were created in my mind and darkroom. What is the difference? Uelsmann’s surrealistic images are neither realism nor abstraction. They surely are surreal.

This blurs the line between realism and abstraction. But is it art? Ultimately, this is the critical question. To my mind, it is art because it has been intentionally created, with thought and planning that went into it, and my intent was to draw viewers into the images and create an emotional reaction. However a final image may be created—from one or two or more negatives or RAW files—is immaterial. To my mind, the real questions are as follows:

- Does the image display a good sense of light?

- Does the image possess a good compositional feel?

- Does the image seem to convey an underlying message?

- How do you respond to the image?

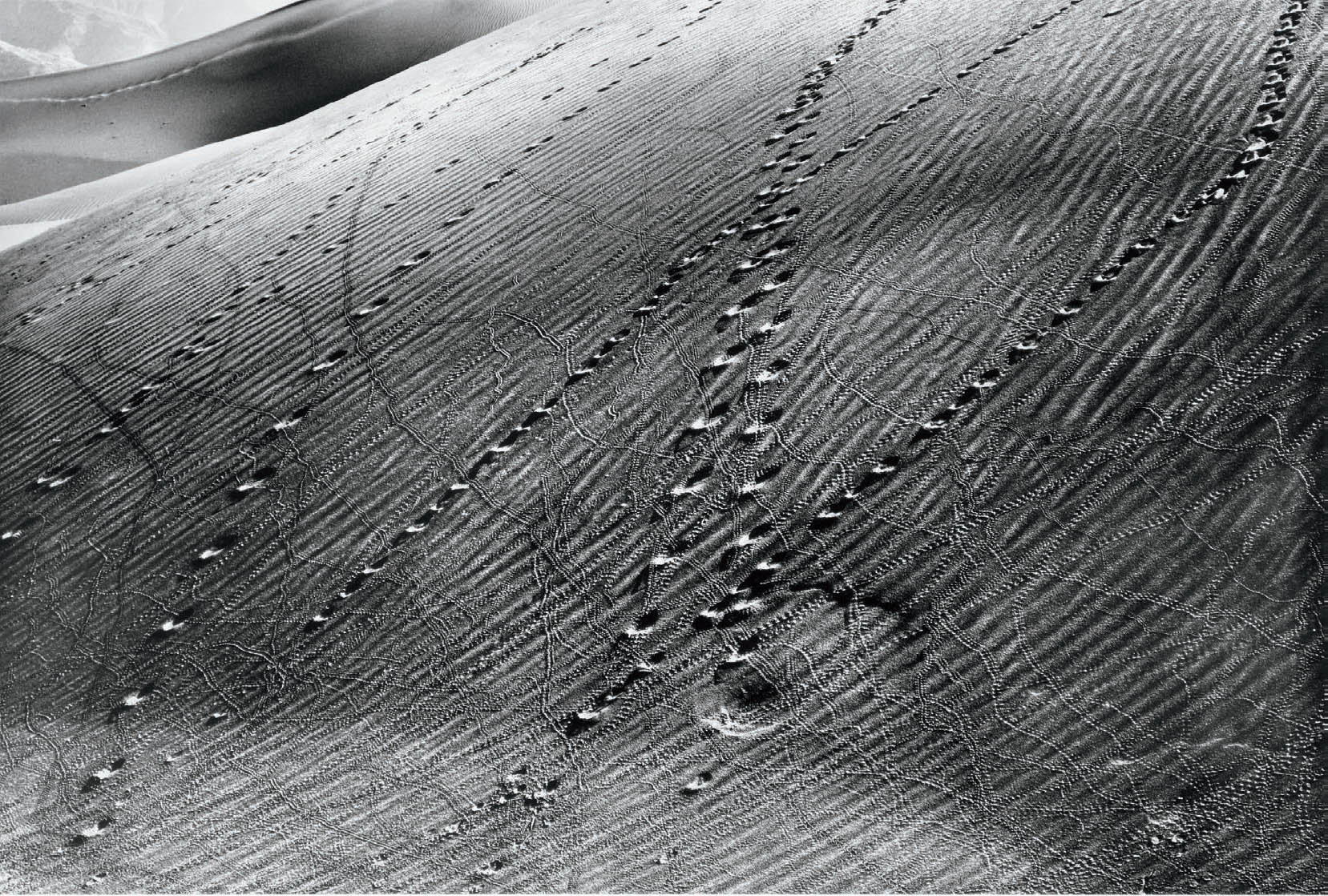

Let’s consider another example. In the year 2000 I began photographing the sand dunes in Death Valley. (I have earlier photographs of the Mesquite Dunes in Death Valley from 1976, but chose to concentrate on other things for the next quarter century.) Something intrigued me immensely at the turn of our current century, which I recognized immediately: the patterns on those dunes and the undulating flow from one hill to the next provided a study of pure design that was astounding. But then they quickly took on meaning beyond just design. I soon recognized that being on them was an intensely quiet, lonely (in a very good sense), uplifting feeling, and I saw around me a “purity” that cannot be described in words. Year after year I visited those dunes, realizing along the way that I could never be in the same place twice. It was always changing. The light, the sand patterns, the whole ambiance was always different, always magical. What began as a pure design study in 2000 remained a pure design study, but it also became so much more (figure 16-5, Dune Necklaces, Death Valley). I also realized that the photographic possibilities were infinite. I have photographed the dunes before and after sunrise, in the midday hours, and at sunset. Opportunities exist throughout each day.

I have pursued my dune studies for the past 16 years, always finding more. The imagery is a mix of realism and abstraction, and I surely believe it falls into the realm of art. It is not quite abstraction (to my mind) because it is easily and quickly recognizable as sand, but it is not quite in the realm of pure realism because of its design orientation and it often lacks a sense of scale. Sometimes it’s hard to tell what the lighting conditions were when the negative was exposed . . . sunny? . . . cloudy? . . . midday light? . . . sunrise or sunset? I find that ambiguity intriguing, thereby posing a question to the viewer of what conditions the image was made under. But whether the lighting is obvious or not, I am trying to create an image that captivates the viewer, gluing him to the photograph. I also realize that the dunes, unlike the slit canyons, was subject matter that had been photographed extensively before I turned my attention to them. So I realized from the start that I had a challenge to produce imagery derived from time-honored subject matter that is somehow different. And I must add beauty to my definition of art: I view art as the creation of something beautiful, with a quote from the great impressionist painter, Pierre Auguste Renoir in mind: “For me a picture is something likable, joyous, and pretty . . . yes pretty. There are enough ugly things in life for us not to add to them.”

Figure 16-5: Dune Necklaces, Death Valley

The dunes are alive with activity, but most of it takes place at night, so they seem largely barren and devoid of life during the day. But the evidence is there that whole communities occupy the dunes, as the many footprints attest. They cleverly adapted to the intense heat of the day by confining their activities to the night.

What attracts you? What aspect of it do you find compelling? How do you want to convey your feelings to others through the photographic vehicles of light, color, and composition? Those are your creative tools, just as sounds, rhythms, timbres, and melodies are the creative tools of the music composer. These creative tools have to be used wisely, and melded with the technical tools of the trade to convey your thoughts in the most articulate manner. Finally, and perhaps most important, are you enjoying your photography? And are you trying to communicate something of importance to you?

The Strength of Abstraction

Allow me to return to my images of the slit canyons once more. By seeing the canyons as analogies of the universe, from the subatomic to the cosmic, I photographed them in a particular way—a way that I would not have considered otherwise. They had a further meaning—surely a deeper meaning—to me. Minor White’s great comment that “You photograph something for two reasons: for what it is, and for what else it is” is always worth considering. I photographed the slit canyons specifically for what else they were. Because they are abstractions, other people see things in them that I never saw or could have imagined. One man thought they were wood details. One woman, a marine biologist by training, was reminded of underwater life forms she had studied. I’ve been amazed at the variety of responses, and I’m pleased by the spread of interpretations that the images afford. Each viewer brings his or her own background and imagination to the interpretation, thereby enriching me with alternative insights and interpretations.

![]() I doubt that photographs can unlock emotion in the viewer if there is none within the photographer.

I doubt that photographs can unlock emotion in the viewer if there is none within the photographer.

It’s been my observation in dealing with workshop students over a period of more than 30 years that beginners tend to shy away from abstraction in photography because they feel it lacks emotional value, or they feel it doesn’t “tell the story.” They may be thinking in terms of cold design constructions, for it’s simply not true. Photographic abstraction can be rich with emotion and questions (if not answers). The best way to explain this is by analogy. Surely music is the ultimate abstraction. It’s nothing more than sounds and rhythms. Yet it’s so much more. Who can listen to Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony without being filled with awe; to Gottschalk’s piano pieces without a feeling of delight; to Grieg’s lyric suites without feelings of joy and serenity? Music of all types fills us with emotion, but where does the emotion come from? Perhaps it is within us, and the music simply unlocks it. I believe that photography can do much the same. Abstract photography may be able to do it as well—or better—than realistic photography for it may be subject to wider interpretation.

I doubt that photographs can unlock emotion in the viewer if there is no emotion within the photographer—either in the initial seeing or in the ongoing process toward the final print. It is this inherent feeling within the photographer that I referred to earlier as “internal conviction.” I can’t go out and photograph an arbitrary section of something as an abstraction, then expect anyone else to respond to it intellectually or emotionally if I had no internal response to it myself.

That was my problem with the Bodie images. I was dealing with textures, tonalities, lines, forms, balances, and other aspects of composition, but not with real emotion. For several years, I thought I had strong feelings about them, but in time I realized I didn’t. (Most likely I was just pleased that they were different from my other photographs.) Internal conviction is like love at first sight: It always seems perfect when you’re in the midst of it, but as time goes by you may see it differently. Whether the canyon and cathedral photographs qualify as art is not for me, but for others, to decide. But I can say this: They are honest and they are deeply meaningful to me. They depict the essence of the two subjects as I see and feel them. To me, that’s the most important thing.

What about my multiple negative composites: Are they honest? I think so. They depict whole landscapes I would love to see. In other words, they convey my imagination or vision of the way I would like to see the world. Isn’t that the essence of literature? Is a Brahms string quartet honest? Does it depict reality? Foolish questions, aren’t they? In my composite images I’ve created landscapes that elicit a response in me, as a Brahms quartet surely elicits a response in me. If they also elicit a response in the viewer, so much the better.

It’s interesting to note that while the majority of painting today has long since departed from realism, the work of a realist like Andrew Wyeth is highly valued. The revelation in 1986 of his Helga paintings further enhanced his artistic stature with the general public. Yet critics find it hard to assess his work. One of the problems critics face is that they must make immediate assessments without the perspective that history affords. All we have to do is look at the initial critical response to the impressionists, pointillists, surrealists, etc., to see how wrong immediate assessments can be! Still, it’s my contention that most critics can’t deal with Wyeth’s work because they seek to label it, and the only applicable label is pre-20th century representationalism. They can’t come to grips with the fact that realism can be fine art if it shows heightened insight and sensitivity. Wyeth’s work has that innate quality; most critics do not.

The key difference between Wyeth’s art and the presidential portraits referred to earlier is that Wyeth’s work shows character and feeling, whereas most presidential portraits show a face and nothing more. But then again, considering some of our presidents, one wonders if there is more!

Inwardly and Outwardly Directed Questions

In viewing and responding to photographs, most people miss the point, just as the critics do with Wyeth. All too often, several questions arise that seek information about the making of the photograph.

The first such question is: Where is it? This question applies to a realistic photograph in which things are recognizable. More often than not, the viewer who asks where the scene is located has little genuine interest in the location. However, this is not a meaningful question from an artistic point of view. What does it matter where the photograph was made? The mere fact that this question is asked implies that the photograph is not regarded as a work of art, but rather as a travel inducement.

I’ve never been to Greenland or Baffin Island, adjacent to it. But I’ve flown over both, six miles above them on commercial jets, and have made photographs of each that have excited me immensely, simply because the landscape I saw miles below me—and was able to see under fantastic atmospheric conditions—made the land even more extraordinary and mysterious. The images, of course, are handheld digital images. I had no choice of where to stand or place a tripod (I had no influence over the route of travel and no tripod was used or allowed on the commercial jetliner), and I had to shoot through the plane’s window (they never allow passengers to open the window at 33,000 feet). The image was exposed just about noon, local time. But I had two major choices: whether to make the exposure, and whether to show the result. My answers were emphatically YES to both (figure 16-6). While people surely may ask, “Where is this?” I do not see it as a travel inducement, but as an expressive image of a magnificent section of our planet.

A somewhat different aerial photograph made well after sunset of Mt. Shasta, in Northern California, displays a decidedly impressionistic feel, due to the instability of handholding the camera over a 1-second exposure (figure 16-7). Although attempting to be perfectly steady, it was impossible for that length of exposure and with the plane’s vibration. But I liked the result, and decided instantly to go with it.

The second question people often ask about a photograph is: “What is it?” This question indicates an abstract image where viewers want to be told what they’re seeing. Does it really matter? Would that question be asked of an abstract painting? Surely not! But because a photograph is real—it is “of something”—people almost always ask what it is.

The final question most often asked is: “How was it done?” This concerns itself with the technical aspect and is the most pertinent of the three questions, but it still misses the point of artistic value. Each of the questions indicates a superficial interest in the photograph and a lack of real interest in its artistic merits. I feel that each of those questions are outwardly directed. They seek information about the making of the photograph.

Figure 16-6: Baffin Island Fantasy

Stiletto-sharp summits jab through clouds on Baffin Island, Canada, as seen from 33,000-feet in the air. It was like looking down on a dreamlike fantasy landscape that appears unearthly in so many ways. The maneuverability of a handheld digital camera has opened up photographic possibilities that I had never previously experienced, extending my expressive and interpretive reach in new and exciting ways. As such, my digital camera is the best “second camera” I have ever used.

From an artistic point of view, inwardly directed questions are far more pertinent. One such question is: What do I see in the photograph? This could apply to photographic realism, abstraction, or whatever. It asks how you, the viewer, interpret the work of art. A second such question is: How do I respond to it? Again, this applies to both realism and abstraction. You may respond positively or negatively; you may be confused, amused, angered, or depressed. You may experience any number of other emotional reactions. These questions are independent of the photograph’s location, the subject matter, and the method of production.

![]() When viewers ask inwardly directed questions, they are truly looking at photography as art. When photographers ask these questions of their own work, they are likely to be at the brink of producing fine art.

When viewers ask inwardly directed questions, they are truly looking at photography as art. When photographers ask these questions of their own work, they are likely to be at the brink of producing fine art.

I feel that when viewers ask inwardly directed questions, they are truly looking at photography as art. When photographers ask these questions of their own work, they are likely to be at the brink of producing fine art.

The outwardly directed questions appear to be unique to photography. They are rarely, if ever, asked of a painting. I doubt that such questions are ever asked of other art forms. Nobody would ask what Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony is, but most people surely would ponder how they are affected by it!

It’s important to remember that the finest art always elicits an emotional response. The response doesn’t come from a print that simply has a good white and a good black, but rather from one that has good content, good composition, and personal meaning. When these three ingredients are made clear through good printing, the photograph will find an appreciative audience.

Figure 16-7: Mt. Shasta, Impressionism—Dusk

Not all images have to be sharp. This one isn’t. But it works for me in a different way. It has an impressionistic feel, and I liked it when I first saw it on my monitor, and liked it more as time passed.

The Power of Photography

In the first chapter, I discussed my feeling that photography’s inherent realism makes it the most powerful art form in the world today. People generally view a photograph as a literal depiction of reality, even when the image is highly manipulated or overtly abstract. This gives the photographer the power to alter reality greatly and still present it as reality, which is a power that no other art form possesses.

For example, most viewers feel that Ansel Adams’s Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico, 1941 is a literal depiction of the scene under extraordinary conditions. Great numbers of people roam about with their cameras waiting for similar conditions so they can duplicate the drama of that image, and they have no realization that the conditions never existed, but that the photograph was heavily manipulated to achieve the effect. They feel that Ansel was fortunate to come upon such spectacular conditions. They feel that he was simply in the right place at the right time. They view the conditions as realistic without recognizing that he greatly aggrandized nature by his method of printing. A painter could hardly hope to have an aggrandized landscape accepted as reality.

Although the perception of a photograph as reality appears to apply solely to realism, that perception also enhances the impact of abstraction. Again, I refer to my slit canyon images. An abstract painting of the canyons would automatically be viewed as artistic imagination, but an abstract photograph imbues the scene with reality—and therefore with heightened meaning and importance. And it goes beyond that. One of my images, Phantom Arch, Lower Antelope Canyon (figure 16-8), is a double print of a single negative. It’s printed back-to-back to create the impression of a stone arch within the canyon. Because of the printing method, the image is impossibly symmetrical from a natural point of view. Yet because it’s a photograph, people instinctively respond to it as reality. Most just shake their heads in amazement at the astonishing natural phenomenon! Again, only photography could do this.

Consider another aspect of photography: its universal language. Like music and the other visual arts, it needs no translation. Its message can be felt by anyone worldwide. Photography, like all other visual arts, transcends language and reaches across international boundaries. The work of André Kertesz, Ansel Adams, Joseph Sudek, Mary Ellen Mark, Sabastiao Salgado, Manuel Alvarez Bravo, Brett Weston, and others speaks to the world because the visual language is universal. It would be shortsighted and foolish to underestimate the power of that communication.

In conclusion, it must be said that photography is a very powerful art form. It’s a powerful form of communication. For an individual photograph to achieve the level of art, it must go beyond literal representation. Both realism and abstraction offer avenues toward achieving photographic art, but each must possess the integrity of artistic conviction. Because we are so inundated with photographs in newspapers, magazines, billboards, catalogs, and dozens of other everyday items, the task of the photographer is even greater than that of artists in other media. However, when the level of art is attained, photography becomes the most powerful art form of all. To me, that makes the greater effort worth it.

Figures 16-8a and 16-8b: Phantom Arch, Lower Antelope Canyon

My eye was attracted to a dark swirl of rock surrounded by an apparent outward spiraling of forms. But the resulting image had no appeal to me. I was so displeased with myself that I vowed to do something about it before moving on to any other negative! I’ve never been able to reconstruct how I came upon the idea of double printing the single negative, resulting in the final image. Turning the negative 90 degrees to the right, I exposed 95 percent of it while dodging out the right edge, then turned the enlarging paper 180 degrees in the easel and made a second identical exposure. The dark form at the top merges with itself, creating the illusion of an arch within the canyon. It is complete fiction (hence the name “Phantom Arch”) and one that preceded my multiple negative images by eight years.