Anthony Scott’s inspiration for wanting to learn about stop-motion came from watching King Kong and Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer as a child. Anthony (see Figure 8.1) grew up studying art and filmmaking before moving to California to start his animation career. His first job as a stop-motion animator was on the 1987 New Adventures of Gumby series, and then on MTV and Pillsbury spots under director Henry Selick. This led to his first feature film animation job on The Nightmare Before Christmas, followed by James and the Giant Peach and MonkeyBone. Anthony has also worked as a computer animator on Pixar’s Toy Story 2 and A Bug’s Life and Evolution at Tippett Studios. He worked as animation director for the WB’s TV series Phantom Investigators and Clokey Productions’ Davey & Goliath’s Snowboard Christmas. Most recently, Anthony was the animation supervisor on the production of Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride in London, England. I have admired Anthony’s work and visited his Web site for many years, so I contacted him to contribute to this book, and was pleased to learn he was originally a Michigan native like myself!

KEN: Anthony, after having worked on many of the most famous stop-motion animation productions, what are you working on now?

ANTHONY: Right now I’m in between projects, taking some time off after working in London on Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride. I recently visited my family in Michigan and my oldest niece wanted to be the Corpse Bride for Halloween, so I helped her make a costume. [laughs] During this time, I’ve also been able to work on a personal film project I’ve been trying to do for years. It’s a little early to say much about it, but I’ve been working on the story, storyboarding, and sculpting maquettes. What it all comes down to is you’ve got to get the story right before you move forward, and I’ve gotten it to a place where I’m pretty happy with it. I like to sculpt, paint, and get my hands dirty, so I’d like to do as much of it by myself as possible, but when it comes time to shoot it, I might need some help with building puppets and sets. It’s a simple film though, so the next time I have some time off I’ll move on to the next step.

KEN: Will you be shooting the film in your own space or at a studio?

ANTHONY: Hard to say at this point. It would be nice to have a studio space so I can have different kinds of equipment at my disposal. It will become obvious where I need to shoot it depending on where I’m living and what my resources are. Stop-motion is a funny business, because there aren’t too many studios that exist on their own. Most of the projects I’ve worked on come together and exist for a while, but once the project is over, everyone packs up and leaves. I think Skellington Productions was the only studio that I’ve been a part of that lasted for more than one project, and that was Nightmare and James. There was about a year between those two projects when a few animators were shooting their own films inside the studio. Tim Hittle shot Canhead during that time; Mike Johnson did The Devil Went Down to Georgia; also Justin Kohn and Trey Thomas made films during that time since they had the space and equipment to do so.

KEN: Which shots did you work on in Nightmare ?

ANTHONY: It’s hard to remember every single one, since I worked on so many little shots throughout the film. I worked on some of the “Making Christmas” song sequence, a few shots with Sally, and many shots with Jack. The biggest sequence, and the one I’m most proud of, was the entire “Poor Jack” song bit. That occurred about a year after I was on the show, so I had a lot of time to get accustomed to the puppet and the style of the animation. It definitely took me a couple of months to get into it, because it was my first feature film, and I was used to working on TV shows and commercials. A lot of the commercials were shot in the same style and quality as Nightmare, but working on a feature was much more involved, because it’s a story, not just a little 30-second spot. So after a year I was really getting into the head of Jack Skellington. I had a good time working on that sequence, because I had time to plan it out, work on it with the director, and it was a part of the film I felt very strongly about. It was a great moment of transformation for Jack, when he realized he had to stop this idea of taking over Christmas and accept who he was. It was definitely my favorite scene to work on, and also the most challenging.

KEN: Yes, that is actually one of my favorite scenes as well. There’s so much emotion and soul that comes through in the animation. There’s one particular moment I love right before he jumps off the angel statue, where the animation is so smooth and flowing.

ANTHONY: Yeah, that was a tough shot to do. Normally we animate on tabletops, but with that shot, to avoid getting the stage ceiling in the frame, we had to put the camera right on the floor, along with the angel statue. I was animating on my knees on a concrete floor. I had knee pads on, but when you’re crawling like that for three days, it’s still pretty painful. [laughs] Pain is definitely something that comes with stop-motion animation.

KEN: Yes, I can certainly relate to that, too. How was the transition from those working methods to computer animation while working at Pixar?

ANTHONY: At first it was tremendous excitement, because I was very curious about computer animation. The first Toy Story came about 6 months before James did, and it impressed the entire world, including myself. So there was a great curiosity from people who had been doing stop-motion, to figure out how they did it and if we would like the process. I didn’t know much about computers, but at that time they needed people who knew how to animate, and they were willing to train us on their software. In many ways it was like relearning animation, because the process is completely different. Pixar was a great place to learn. They know what they’re doing; they care about story and characters, so it was quite an education, that’s for sure.

KEN: What are the biggest differences in working on feature films versus working on commercials or TV series? Do you have a preference for one or the other?

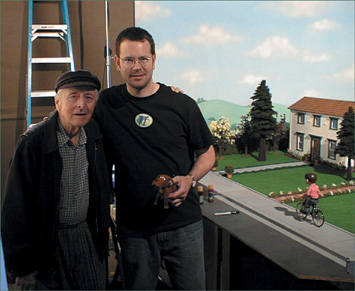

ANTHONY: That’s interesting. You would think that I would prefer to work on features, which tend to have more money, but they’re also more ambitious, with lengthy production schedules, so I guess the best answer I can think of is, I prefer shows that have a schedule that fits what we’re trying to do. I like features because we really try to push stop-motion far. When I first heard of the Corpse Bride project years ago, I thought, Wow, they want to animate a flowing dress and veil in stop-motion? Good luck! [laughs] So that was my greatest challenge working on that film, figuring out how to make that work, and it’s great when you have the time to try things like that. But sometimes it’s also fun to throw yourself at something like the Davey and Goliath special (see Figure 8.2), which I had a great time working on. I got to storyboard, I got to animate, and figure out a shooting schedule so we could get it done on time. So it was great wearing several different hats on that one, and getting to use the skills I’d developed over the years. My first animation jobs were in television production, so it’s always nice to return to that and learn more. Everything is rewarding in its own way.

Figure 8.2. Anthony Scott with Gumby/Davey and Goliath creator Art Clokey in 2002. (Courtesy of Premavision/Clokey Productions.)

KEN: What are your preferred methods for planning out an animation shot?

ANTHONY: When you’re given a shot, you’re given an exposure sheet that breaks it down into frames, and also the dialogue, if there is any, so I use that as a guide to plan it out, as far as where I want to hit certain poses, and things like that. I’ll take the sheet and the audio recording and act out the shot a few times with my body if it’s a human-type character. Sometimes I’ll use a stopwatch to plan the timing and make notes on the exposure sheet. On a feature, I’ll typically do a rough animation test, shot on fives or tens, just to give the director an idea of what I’m thinking, to make sure the poses are readable, the lighting’s good, and the camera move is working. So between the tests, notes on the X sheets, and meetings in editorial, eventually the director is comfortable to launch me onto the shot. Television is usually a different process, since there’s not enough time to test anything, but I still have a sheet to work from.

KEN: What are the biggest changes you’ve seen in stop-motion animation over almost 20 years of working in it?

ANTHONY: Well, we didn’t have frame grabbers when I started on Gumby. The first time I used one was on a commercial for Colossal Pictures, where you could view two stored frames and your live frame, but not the whole sequence of frames. That was enough to make the animation smoother and also relieve some stress because you didn’t have to worry about your shot as much overnight. Years later, when you could review the whole sequence, it was even better.

You didn’t have to think about the shot as much over the weekend; just resume on Monday by reviewing it on the frame grabber to get back into the rhythm and continue. Before that, you had to take very careful notes, and it was pretty tedious. The computer, of course, has changed things and continues to do so. We shot Corpse Bride digitally, which was great and really sped things up in regards to post-work, removing rigs, and so forth, since it was already in digital format. Computers have really helped stop-motion, allowing people to use things like webcams and shoot their own animation at home. A frame grabber used to be something you had to pay thousands of dollars for, but now anyone with a computer can buy animation software off the Internet, which is great. It’s neat to see on my Web site (www.stopmotionanimation.com) that there are kids and other people trying it (see Figure 8.3).

KEN: Tell me more about your Web site and the inspiration behind starting it.

ANTHONY: I was just finishing up at Pixar when I started the site, and I wanted there to be a Web site about stop-motion that wasn’t just about movies or stuff that I had done, but more of an online community for learning more about it. The whole point of it was to be a resource for people, mainly beginners in stop-motion, to give them the opportunity to learn, share, and ask questions to those who had been working in the field for years. The first thing I included was a stop-motion handbook, and the site has since evolved to the point where the message board is really the center of the whole thing. The site is something I watch mostly from a distance now, since I’m usually so busy, but it’s taken off in a big way, and I’m really happy about that.

KEN: What advice would you have for someone who wanted to be a stop-motion animator?

ANTHONY: Well, the best advice would be to get on www.stopmotionanimation.com, of course....[laughs] But really, the best thing is to figure out what it is you want to do, first of all. If you want to specialize in animation, then focus on that. If you want to get into the business, that’s usually how you’re hired. You’re not hired to make a puppet, build a set, and animate it. I know stop-motion tends to be a medium where you do everything, which is kind of cool, but I also know that people get really into building their puppets, which takes a long time, so by the time they animate a puppet, they don’t tend to put the time they should into the animation. So if you want to animate, maybe use a simple puppet or get someone else to build the puppet for you, so you can focus on the animation. It’s good to know what you want to do, because if you get the opportunity to apply for a job, that’s the first thing they will want to know. They only want to hire the best.

KEN: Do you think there is more room for stop-motion programs in schools?

ANTHONY: I think if there were more stop-motion jobs, there would be more stop-motion classes in schools. It’s just one of those things that’s out there on the fringe. It’s something I always knew I wanted to do, but I was never sure if there would be enough work. When I left Michigan and came to California (at that time it was 1983 or ’84), there was no stop-motion going on, other than Tom St. Amand and Phil Tippett doing some effects at ILM (Industrial Light and Magic). So at the time I was trying to get into something similar to stop-motion, which was special effects make-up, because I like to sculpt, so I had taken the Dick Smith make-up course. I was pursuing that around the time the Gumby series came along (see Figure 8.4). I submitted a demo reel of my student films from LCC (Lansing Community College), which is what got me the job. I was just in the right place at the right time.

Figure 8.4. Anthony Scott on set for an ABC spot in 2001, the first time animating Gumby since 1988. (Courtesy of Premavision/Clokey Productions.)

KEN: What with all the resources and technological breakthroughs offered by the computer, what do you see for the future of the stop-motion medium?

ANTHONY: I don’t see it changing too much. It’s always been this strange animation art form and not the most popular, but somehow it keeps breathing and people are still interested in it, so people will continue making stop-motion films. It’s just another way to do it, really. Some people like to act on stage, and some like to act in film; people have different preferences, and a little variety is always good. It’s like a wave, too. For a while it seems like nothing’s happening, and then, next thing you know, two stop-motion features come out in the same month (Wallace & Gromit and Corpse Bride were released 2 weeks apart)! When I was a kid, Disney would put out a film only every couple of years. Now there’s so much more animation in production.

KEN: Yes, I remember before the days when every Disney film was available on video, it was like a major event when an old feature would be reissued, or even a new one. It seems stop-motion features are still like that, where every few years another one will come out, so it’s more of an “event.”

ANTHONY: Especially The Nightmare Before Christmas, which still has a life in theaters. It’s amazing! I can’t think of too many other movies that still have so much merchandising being created for it after so many years. It’s great to have been a part of something with that special appeal to it; it was a great film to work on. Even at that time, we knew we were working on something that hadn’t really been made before. There weren’t any CG features being made, so it was a cool time.