THERE’S MORE THAN ONE WAY to pet a cat—and there’s more than one way to shoot a music video. In addition to the different methods of shooting the video, there are combinations of those methods. I would say that the number of ways to shoot the video are limited only by your imagination, but that would sound like a cliché. So I won’t say that.

The options you have for shooting your music video come under two main headings. One deals with the technical aspects, including the number of cameras you’re using and the different ways in which you can record the audio. The other over-arching category has to do with style of video you want to create. Will it be a live video of a live performance? Will it be a dramatic story, intercutting between lip-synced performances and cut-away or B-roll footage? Chapter 6, “Choosing a Video Style,” goes into detail about choosing a video style in terms of genre and the look, feel, and identity you want to portray. This chapter discusses style as it relates to the options you might choose for shooting the video and recording the audio, depending on the type of video you are creating.

Probably the easiest way to shoot a music video is to literally shoot a video of your band— or of your act—performing live and then call it a day. One camera. One band. One song, beginning to end. As you can see, there is one potential drawback, and that is boredom.

Now, if the band is the Rolling Stones or an artist of that caliber and fame, then maybe this idea will fly. But for us up-and-comers, the song (and performance) would not only have to be extremely good, it would also need some buzz around it. You see, before the Rolling Stones were the Rolling Stones, most people didn’t give them a second glance. The “here’s my band performing at the Long Beach Battle of the Bands last year” type of video is more like a home movie than a music video, and you know how those home movies can be.

Now, before you send in those cards and letters telling me how crazy I am and how much nerve I have saying something like this, please stop. First of all, I’m talking in general terms about most cases. And second of all, I am one never to say “never.” You’ll see that thread of belief tied together throughout this book. If your music video is simply one live take of your act performing a song from beginning to end, and people love it, more power to you. Still, there are some things to keep in mind even when creating this kind of music video, especially if it is recorded at a concert or other type of live event. (I introduce the topic of recording live events here, and then go into more detail in Chapter 8, “The Video Process: Pre-Production and the Shoot,” where I discuss the live multi-camera shoot and recording live audio.)

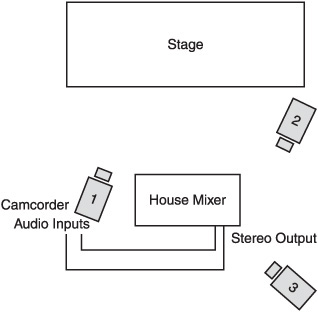

One important point to keep in mind is that you need to feed your camcorder a direct recording of the audio, usually from the output of the house mixer, and not from the microphone. Using the camcorder’s built-in microphone is not a good idea, that is, unless you want poor quality audio. Record the audio separately the best way you can and, if necessary, sync it up later. And when I say not to use the microphone input of the camcorder, I’m saying avoid using that audio for your final audio. You do, however, want to record the audio through the audio inputs of the camcorder so that, at the very least, you have a reference point for synchronizing everything later, especially if you plan to sync up with a separate recording of the event.

You can improve a live video by at least a notch by shooting with additional cameras and by using more than one angle. You can also add cameras beyond those two, if you want, and include wide shots, close-ups, and audience-reaction shots to create alternative clips that correspond to the same point of time within the song.

Again, you can record the main audio directly into the camcorder inputs, and sync up the clips later at your heart’s content. You can have the second and/or third cameras record “wild”—meaning that you could use their microphone inputs (or better yet, a higher-quality external microphone) to capture applause and other miscellaneous sounds. This type of shoot yields a professional look. In Figure 7.1, you can see how a feed from the house mixer to the audio inputs of the camcorder, along with second and third cameras recording wild audio, can be set up.

Figure 7.1. This diagram shows one possible setup for using three cameras to shoot a live concert for a music video.

Shooting a live performance is akin to shooting a documentary. You are, in essence, documenting the time and place of an event, and not a whole bunch more. As you will see in the discussion of other types of videos (story-driven videos and effect-laden videos), shooting a live performance will take you only so far. More often than not, you will want to add some dressing or frosting to your presentation.

A long, long time ago—in a network television station not so far away (not from my house, anyway)—a young man had an idea for making music more interesting. It was long ago, for it was the 1970s, and the young man was me. I was a big fan of many of the great artists of that era, including Simon and Garfunkel. Every time I heard one of their songs, I could see moving pictures in my mind’s eye. It isn’t difficult to do this with their music, because their music is very “visual.” It lends itself, easily, to a visual presentation.

I was working in the newsroom of CBS Television in Los Angeles. No, I wasn’t a big shot or anything—quite the contrary. It was one of the very first jobs I ever had—I was a “runner” (also known as a “gopher”—go for this, go for that), and yet the job was very exciting for me at the beginning of my working years. I got that job because I knew Joe Landis, a producer at CBS. He got me in the door and proved to me early on that it is a matter of whom you know.

Many of the songs by Simon and Garfunkel could have made great music videos. But for some reason, I was hung up on a song of theirs called “Old Friends” from the album, Bookends (You can still order this great Simon and Garfunkel on Amazon.com, as shown in Figure 7.2). Here are the lyrics of the first verse:

Old friends,

Old friends

Sat on their park bench

Like bookends.

A newspaper blown though the grass

Falls on the round toes

Of the high shoes

Of the old friends.

You could be the worst video director on Planet Earth and still do a good job with those lyrics. It is truly a no-brainer. So, with this song in my head, I created a little presentation of how this could be made into a visual piece. Now, keep in mind there was no MTV at that time. Heck, there weren’t even any videos at that time, except for the videos used in network broadcasting. There were no home videos or video rentals or cable television. (I told you it was a long, long time ago.)

So I made a storyboard type of presentation of “Old Friends,” even though I didn’t know how it might be used—in other words, what the delivery medium would eventually be. Back then I could visualize a regular weekly show, perhaps, with a group of songs presented in this visual style. Yes, I know, we have these now, and they’re called music videos, and they run ‘em around the clock. I could picture it back then.

But my friend, Joe, at CBS couldn’t picture it. He gave me a nice pat on the back and sent me on my way. So, I thought to myself, “How silly…who would want to see songs made into visual stories anyway?” And there you have it, ladies and gentlemen. No, I’m not saying that I was the inventor of the music video before there were music videos. After all, I didn’t do anything about “Old Friends” or anything else for that matter after Joe had passed on it. I could have been an inventor of the music video, but I didn’t pursue the idea. And if you don’t know it by now, perseverance is a requirement in the entertainment business.

Ah, so sweet. So visual. Such story-driven music.

Whether the music comes first or whether an idea that spawns the music and the visuals to go with it comes first, the result is the same: story-driven music. A story-driven music video is a mini-movie of sorts. You can write a song; then later you can write a script and hire the actors, the director, and the production crew to produce a mini-movie that we now call a music video. Or you might conceive the whole package right from the start and create it that way. Regardless, you end up with a three- or four-minute music video.

This section’s title describes the majority of all music videos—a combination of a live studio performance with a scripted, story-driven production. In the majority of videos, you’ll see three or four seconds of a band performing and then see a cut to the band members (or actors) acting out the part that the lyrics are describing. Then you will likely see a cut back to the band performing. The video may stay on these shots for even shorter amounts of time than three or four seconds. It is not uncommon today to see clips that are one second or less, whether they are live performance shots or scripted segments. Actually, many have described the “MTV Generation” as baby boomers who grew up on the quick cuts and rock n’ roll of the seventies and eighties. In a land long ago and far away (say, before 1965), the pace of visuals in a movie or television production was much, much slower—so much so, that many in today’s generation might fall asleep from boredom if subjected to such a show.

If you did your earlier homework assignment (in the sidebar of Chapter 3, “Music Video Cookbook: The Ingredients”) of watching hours of music videos, you may have noticed a variation of the live/scripted video formats. But before you take out your camcorder—even before you start writing your script—keep in mind the variety of live/story-driven videos you can create:

The standard: Videos of this kind begin with the band (or artist), cut to a scripted segment and back to the band, and so on, alternating throughout, as described in the preceding section. Often the intro to the song will be scripted and then cut to the act at the beginning of the vocal.

The standard plus: This type of video is like the preceding one, but with a dozen or so costume changes within the context of the same song. Sometimes the artist will be lip syncing, sometimes not.

The setup: This type of video begins with a story segment as a setup, perhaps 30 seconds to a minute long; then it cuts to the band, and back again.

Animation: Here there are no real video images of the artist, only computer animation or hand-drawn images.

Stop motion: These videos have a variety of sub-flavors—combined with performance, not combined with performance, or blended with several types of formats.

Green screen: These videos have a completely fabricated “set” created by computer animation combined with the act’s video footage.

Motion picture soundtrack: If you’re lucky enough to have a song placed in a movie, you might also be lucky enough to make a music video that intercuts between your song and clips from the film. These soundtracks are usually reserved for major acts, but they aren’t out of the realm of possibility.

The combo: Any combination of the previously mentioned.

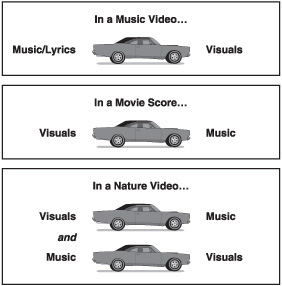

This might be a good time to take a look at the difference between a film score and a music video. It is interesting to note that these two disciplines come from opposite ends of the spectrum. As I’ve been discussing, a live performance and a story-driven music video are based upon one major element—the music. Although I’ve mentioned a few different types of productions, one thing remains the same. The music is the real “driver” of the music video. That’s where it all starts, and that’s where it all ends.

When a composer is scoring a film, the opposite is true. The visual—the story—drives the music. The task here is to make the music fit the visual. The music takes on two primary roles:

To enhance the emotional context of the scene

To help move the story along

In a music video, the emotional context is already there in the form of the music and the lyrics. In a film, there may, in fact, be a story with some emotional context, but when scored effectively, the music really brings the emotional context to new highs (or lows, depending on the scene). Take out the music and two things are likely to happen: You will not have as much depth of emotion in the film, and the movie will plug slowly along, seemingly taking forever to reach the end. The musical score addresses both of these issues very well.

Again, before you send in those cards and letters saying that I’ve lost my mind—yes, there are exceptions. One example can be found in nature-based videos that are typically accompanied by new age or ambient music. In this case, the visuals and music are of equal “weight,” and it would be difficult to call a clear “winner” in terms of who’s driving what (see Figure 7.3 for “driving” directions). These are relaxing, healing videos that are essentially scored—the visuals come first, and the composer sets it all to music. So although there are exceptions, there are generally rules, and sometimes those rules are broken.

What is interesting about the overall comparison is that the audio tool chests of a songwriter (doing a music video) and a composer (creating a film score) are the same. The DAW, the sequencing software; the virtual instruments; and the outboard gear can all be found in either studio. (Recall that DAW stands for Digital Audio Workstation software, as explained in Chapters 1, “The Process,” and 5, “Tools for Do-It-Yourselfers”.) If you fall under the DIY (Do-It-Yourself) classification for the video aspect of the production, the only additions might be the camcorder, the editing software, and other items directly related to video production.