The organization is one of mankind’s all-time great inventions. An organization is intended to operate as one unit, with all its parts in efficient coordination. But, too often, it does not. The parts operate at disparate levels of efficiency, or they overlap, or they work against one another’s best interests—therefore against the best interests of the organization as a whole. There is misunderstanding and miscommunication …. Things get done, progress is made. But not enough of the right things get done as well as they should. Progress … does not meet expectations.

—Kepner and Tregoe (1997, p. 1)

Introduction

In the quotation above, Kepner and Tregoe (1997) point out the difficulty of performing work within organizations. Organizations divide work among people because they can solve more complex problems this way. Yet at the same time as an organization divides the work so that it is suitable for specialized functions to do the work, the specializations that allow the organization to address complex problems hobbles the organization because of these specializations’ inability to efficiently coordinate itself.

While organizations thrive around the world because they provide a structure that allows for more efficient production of goods and services, organizations also bring their own set of problems as pointed out above. These problems need to be solved for the organization to become and continue to be successful.

Coordination problems create organizational conflict and reduce organizational efficiency and effectiveness. Multiple methods have evolved over the history of organizations to solve these coordination problems in organizations. All of these methods provide valuable insights to the manager about organizational problems. For example, Kepner and Tregoe (1997) created their own approach to developing teamwork in a company. Their approach focuses organization members on four basic thinking patterns. This is achieved by having members continually answer four types of questions:

- What’s going on?

- Why did this happen?

- Which course of action should we take?

- What lies ahead?

Other companies have taken different approaches to addressing their coordination problems. A generic approach to solving problems at an organization level has been Total Quality Management (TQM).

… even when quality has been defined precisely, programs have lacked competitive impact. Many programs have been narrowly focused on the factory floor or have relied primarily on traditional methods of quality control. Little attention has been paid to the underlying sources of superior quality: the relative contributions of product design, vendor selection and management, and production and work force management. Tools and techniques have dominated instead, with short-term improvement projects often pursued at the expense of long-term quality planning. Links to competitive strategy have been few and far between. (Garvin 1988, pp. xi–xii)

TQM Background

In the quotations above we have the reasons why programs such as TQM were developed. TQM and other quality programs, such as Six Sigma, are organizational programs which seek to involve everyone in solving the organization’s problems. In essence, they are programs to help organizations learn. They attempt to improve business processes at all levels of the business hierarchy, so that efforts across departments and business units are coordinated and directed at accomplishing organizational objectives.

The total in TQM refers to involving all of the departments and the individuals in the departments in the efforts to improve performance. Total means that we have to involve everyone. Involving everyone necessarily means that we need to determine how to involve all employees in the effort. The question is how to meaningfully involve everyone, while still meeting production goals and being able to change directions as necessary to remain competitive in the market. Garvin (1988) talks about an essential characteristic of TQM programs, which makes them successful in Japan, in the quote below:

Japanese companies provide an instructive contrast. Their quality performance has been enviable, with dramatic improvements since World War II. Today the quality and reliability of Japanese products are sources of great competitive advantage. Moreover, progress has been achieved through a carefully orchestrated campaign of micro and macro policies, top management involvement and shop-floor activities. Little has been left to chance. An overriding philosophy has encouraged a holistic approach rather than a focus on technique. Short-term projects have therefore meshed neatly with long-term objectives, lending a strategic character to Japanese quality programs. (Garvin 1988, p. xii)

To understand the structure of TQM programs and to create a work design that involves everyone in improving the organization, it is important to recognize that TQM programs are about much more than improving one process. They are a program designed to ensure that improvements are made across the company in a coordinated fashion so that these improvements help the company as a whole—not individual subprocesses—to achieve its goals.

TQM evolved in Japan after World War II to address the organizational coordination issues discussed above. TQM centered around improving quality to obtain a strategic advantage. Many Japanese firms recognized that for their quality improvement efforts to be successful the entire organization had to adopt the quality improvement methods. By creating a program and a structure to manage that program, managers were able to create institutional focus on improving quality.

Regardless of whether a company decides to use a TQM or Six Sigma or Lean Six Sigma program, the company must ensure that the program provides a structure to organize the change. “Structure” means that the program must direct the actions of the managers, so that their combined improvements direct the company toward its goals.

Many of the tools in the various quality improvement programs (Lean Six Sigma and Six Sigma) are the same. There is a standard set of TQM tools, but when an individual company adopts a program it may modify the program to fit its unique characteristics. For example, companies may adapt particular tools to fit a unique characteristic of their need. A hotel chain may choose to focus on service quality instead of product quality and may emphasize the use of tools that help it to measure service quality better.

Often individual managers look at the set of tools used in a typical TQM program or Six Sigma program and decide that tools that simple cannot provide the change the managers want. Or, after implementing a program for a while, managers become frustrated with what they view as limited improvement and discontinue the program. It is therefore important to stress that TQM programs that are not well managed by using the same feedback techniques and management tools taught within the program will not be successful. For example, Izumi Nonaka (1995) reported on a series of lectures that J.M. Juran provided during 1954 to Japanese executives about quality management programs in 39 U.S. companies after World War II. In these lectures, Juran reported that more than 50 percent of the quality management programs in the United States had stalled or failed because they did not have one or more characteristic:

… clarity of program definition, adherence to objectives, managerial competence of the program leaders, and the level of shop participation. (Nonaka 1995, p. 545)

The question then for the executive implementing a program such as TQM or Six Sigma is how to provide this clarity and then ensure adherence, leadership competence, and total participation.

Quality Improvement Infrastructure

Long-term success in any program requires an infrastructure to support those efforts that generate success. When companies are not competitive in the market, they can initially make fast progress with little investment in either training or creating an infrastructure for short-term efforts. But to improve beyond a very basic level, companies must have a short- and long-term plan to succeed. It does not matter if the program to improve is called TQM or Six Sigma or Lean Six Sigma. First of all, the improvement program needs a plan to reach out to all departments, all managers, and all employees, in order to give the company the performance the company needs.

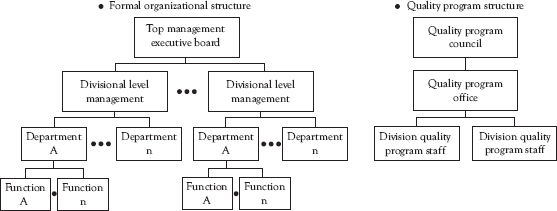

To be able to adhere to a plan, which by definition should be a plan to succeed, the quality program needs an infrastructure to support it. The first infrastructure element to have in place is an organization structure. A generic structure that may be included in the plan is shown in Figure 8.1.

The left side shows a generic organizational structure, with an Executive Board, Division officers, who have departments reporting to them and functions that are within the departments. The right hand side shows the quality program structure.

The Quality Program Council consists of the members of the Top Management Executive Board. The Quality Program Council does not do the day-to-day management. Rather the council sets policy and evaluates performance. The council should serve as champions of the changes that are required throughout the organization.

The Quality Program Office often consists of a Director or Manager with support staff. The responsibility of this office is to work with the Divisional Level Management staff to implement the program in their divisions. They do this in part by establishing goals and targets and, most importantly, the means of sharing these goals and targets throughout the organization. The first step in the sharing is to have the goals and targets adopted by the Quality Program Council and the Executive Board. The Quality Program Office does not have direct authority. Instead, it provides training programs for managers and provides mentoring on the application of changes.

Figure 8.1 Quality improvement program structure

The Division Quality Program staff report to the Quality Program Office, but they work in the various divisions to implement the changes required for the quality program to succeed. They provide training, facilitation, and coaching. They do not supervise the employees in the functions, rather they help middle managers implement the changes and help coach the employee teams seeking to improve. Garvin observed this in operation in Japanese plants he studied. He found that:

… all plants set formal quality goals, using a process that normally proceeded from high general to highly specific targets. From the corporate level came vague policy pronouncements …, which were further defined by division heads … and by vice presidents of quality or manufacturing …. Actual quantitative goals … were set by middle managers, or else by foremen or workers operating through quality control circles. (Garvin 1988, p. 203)

By doing this process of propagating or deploying of goals, these plants initiated the process of achieving higher quality by having everyone commit to higher quality on their own. Every department and function in a department then has a quality target to work to achieve. A responsibility of the quality program office is to measure their progress toward the quality improvement target and to provide training and help to achieve those targets. In this way the assistance from the quality program office is “pulled” from the rest of the employees in the line functions as they need it.

Training Infrastructure

Training differs from education. Training is directed at the skills the individuals need to do their current jobs. Education is more concerned with why things are the way they are. Both are necessary. Deming argued that training continues until workers know all that they can, but education goes on forever (Dobyns and Crawford-Mason 1991).

A common tool to organize training is a matrix as shown in Table 8.1, which shows the positions (or functions) and the training needs for each position.

Depending on the type of skill that is to be taught, different methods of training can be used. A frequently used approach is Training Within Industry (TWI). This approach was formalized by the U.S. Defense Department during World War II. It was later exported and refined within Japanese Industry. TWI efforts in Japan start at the individual level by looking at the way the individual employee does their work. This means identifying and eliminating wasted movements within the work sequence. TWI breaks this process into three modules: job instruction, job methods, and job relations.

The job instruction method is described in four steps, referred to as the JI-4 step method (see Table 8.2).

Before conducting a training session, the manager who is going to do the training prepares to follow this four-step method:

Table 8.1 Matrix of position and training needs for each position

Position |

Skills required |

Priority |

Teaching method |

Goal/Target |

Employee |

Skill 1 |

1 |

|

|

|

Skill 2 |

2 |

|

|

Table 8.2 JI-4 Job instruction method

Step |

Content |

1. Prepare the worker |

Find what the individual knows and interest them in learning. |

2. Present the operation |

Tell, show, and illustrate one important step at a time. (Repeat) |

3. Try-out performance |

The individual does the job and explains the steps. |

4. Follow up |

After individuals start independently, follow up and de-brief. |

- To prepare for step 1, the manager would think about what the individuals are to be trained in and prepare to ask them questions about how the training can affect them.

- To prepare for step 2, the manager must list and sequence the steps that are required and understand what is important about each step that the worker is to perform.

- To prepare for step 3, the managers have to prepare themselves to step back once they have shown the worker the steps to do the task and allow the worker to do them while explaining what they are doing out loud. The manager may correct mistakes if the worker makes them, but should support what the individual does correctly.

- To prepare for step 4, the manager has to arrange a time when he or she will come back and observe the worker and follow up and de-brief them on their progress. This can provide important feedback to the manager about how to improve further training.

Leadership Infrastructure

When management insists on conformance to requirements and provides the participation necessary for prevention to happen, it becomes a different world. All the quality awareness procedures ever developed can’t make that happen. It won’t occur until the employees of the company have a common language of quality and understand what management wants. (Crosby 1984, p. 57)

Leaders are essential to the achievement of quality in any organization. It is the leadership that establishes the strategic direction of the company and it is the leadership which must communicate these goals to the members of the organization. As we discussed above in terms of the Quality Program Structure, it is the leaders who create this framework and use it for improvement. It is only through the leaders’ efforts that everyone can be included in the creation of new ways of working. Finally, it is the leaders who uphold the values during the daily process of performing work. It is the leaders who must ensure that everyone practices the values of the company.

Leadership means more than telling others what to do. Leadership is more than giving a speech. Leadership occurs daily by repeating actions over and over that demonstrate that the leader supports what they say and actually does what they are asking others to do. For example, if the company motto is “Zero Defects,” what is the leader doing to have zero defects in their own work? How do they support others in achieving zero defects? What systems do they have in place to measure defects and take action to eliminate defects?

Managers with the potential to create the conditions for permanent growth need more than charisma. Charismatic leaders tend to see themselves as heroes and assume that a leader needs to compensate for the fact that ordinary people are powerless. …. One cannot expect permanent growth from leaders who have this view of employees—the people who carry the organization. (Hino 2006, pp. 41–42)

Good leaders need to have discipline and they need to encourage discipline in others. The leader must have discipline to promote technological innovation, while avoiding fads by carefully selecting those technologies that can drive performance improvements. For example, Toyota does this by having the discipline to document their decisions and the steps taken in reaching those decisions. Toyota can then examine the results of their decisions so that managers can continuously learn from their decisions and those of others. This documentation allows Toyota to accumulate knowledge. It also allows management to measure whether all employees are responding to Toyota’s values and whether the employee’s thinking is embedded in the Toyota’s philosophy and policies. This allows Toyota to monitor the degree to which these policies have penetrated the organization.

By involving everyone in achieving the organization goals, everyone is seeking zero defects in every action they take. On the other hand, inspection cannot achieve world class quality.

Team Infrastructure

Actually there is serious doubt whether the successful business ever used the one-man concept. Practically every case of business growth is the achievement of at least two, and often three, men working together. At its inception a company is often the “ lengthened shadow of one man.” But it will not grow and survive unless the one-man is converted into a team. (Drucker 1954, p. 173)

Issues of team formation and function involve management as well as operational employees. …. “The hardest task in redesigning our processes,” explained the managing director of a European office products company, “was to get our senior managers to work as a team. They had to take off their functional hats and put on their company hats in order to think cross-functionally. A couple of managers never made the transition and they had to leave.” …. “To function effectively as a cross-functional team, a senior management group must be willing and able to look beyond functional allegiances, …” … In fact, if improvement is to become part of the fabric of work in a team-oriented work environment, team structures are the right unit for streamlining o[u]r quality efforts. (Davenport 1993, p. 100)

… high performance teams have both a clear understanding of the goal to be achieved and a belief that the goal embodies a worthwhile or important result. (Larson and LaFasto 1989, p. 27)

Teams have long been recognized as critical to management success and to continuous improvement as illustrated by the above quotations. Teams are used to structure improvement efforts. Quality improvement teams can be cross-functional or can be formed from team members within a functional unit. Both Deming and Juran credited Ishikawa with creating a facilitating structure to use teams of workers to make quality improvements. Ishikawa used quality circles that involved line workers volunteering their time to work on solving problems. His work on quality circles in quality improvement is well documented and used by many.

The role of teams in lean operations is to use the talents and brain power of everyone in the organization. To do this, the team leader has an important function. They must ensure that the goal is clearly understood by all team members and that they are committed to accomplishing the team goal. It is their responsibility to keep the team focused, to involve all of the team members, and resolve performance issues of team members. The team members also have to make a commitment to using objective facts in their decision making and to collaborate with other team members.

To accomplish this, teams are often given or develop charters and their work is facilitated by managers whose responsibility it is to ensure the team is:

- Working on well-defined problems;

- Using standard methods; and

- Addressing issues that are important to the company.

This is often done by giving responsibility for the direction of a team to a champion, who is a high level executive in the company and whose responsibility it is to ensure that the team is focused on accomplishing strategic objectives.

Teams can be used for many tasks. They are used in product development and root cause problem solving. But they can also be used to benchmark a firm’s performance against other firms and to implement best practices within a company. Teams can also be used on a much more local level for continuous improvement. Kaizen is the Japanese word for continuous improvement. This word was popularized in the United States by Imai (1986). Kaizen is often implemented as a series of structured events that occur over a period of a day to a week. As part of kaizen, there is detailed advance planning followed by a rapid implementation of the plan. Kaizen typically focuses on a large change in the process, while the worker’s continuous improvement is concerned with a more limited change in (or portion of) the process.

Kaizen Events or Rapid Improvement Events

Kaizen strategy is the single most important concept in Japanese management—the key to Japanese competitive success. Kaizen means improvement. … Kaizen means ongoing improvement involving everyone—top management, managers, and workers. In Japan, many systems have been developed to make management and workers KAIZEN-conscious. (Imai 1986, p. xxix)

Much of what we have discussed earlier, such as organizing cross-functional teams to make improvements are part of the kaizen structure that Imai discusses. Continuous improvement can occur along multiple paths. As discussed previously, it can occur as the solution to small problems by teams and team members during their regular work week, or as solutions to problems while implementing improvement programs such as 5S. In addition, improvement can occur because of special kaizen days or kaizen projects, which are events organized and conducted by special project teams established for just that event. These were first highlighted as a unique structure by Imai in the book containing the quotation above.

Rapid improvement events (RIE) or kaizens are typically oneweek focused efforts that are facilitated and conducted by Lean Experts of Black Belts to enable Lean teams to analyze the value streams and quickly develop or implement solutions in a short time-frame. (Juran and DeFeo 2010, p. 336)

The structure used by kaizen teams for the operation of kaizen events can vary slightly from company to company. But, all of them have in common a standard structure that can be roughly summarized as follows:

- The process in its baseline state is studied (As-Is) to determine what is occurring in terms of for example, quality, cost, and delivery in the process.

- The team then sets goals for the improvement and creates a detailed plan of how to achieve those targeted goals.

- The team trains its members on the tasks to be performed during the kaizen events.

- The operations of the process are suspended for 1 to 7 days while the team makes the improvements.

- After the event, the team monitors the process to ensure the changes stay in place and then it returns control to the process operators.

Crosby, P.B. 1984. Quality Without Tears: The Art of Hassle-Free Management. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc.

Davenport, T. 1993. Process Innovation–Reengineering Work Through Information Technology. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Dobyns, L., and C. Crawford-Mason. 1991. Quality or Else: The Revolution in World Business. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Drucker, P.F. 1954. The Practice of Management, New York, NY: Harper.

Garvin, D.A. 1988. Managing Quality: The Strategic and Competitive Edge. New York: The Free Press, A Division of Macmillan, Inc.

Hino, S. 2006. Inside the Mind of Toyota: Management Principles for Enduring Growth. New York: Productivity Press.

Imai, M. 1986. Kaizen: The Key to Japan’s Competitive Success. New York: McGraw-Hill Publishing Company.

Juran, J.M., and J.A. DeFeo. 2010. Juran’s Quality Handbook: The Complete Guide to Performance Excellence. 6th ed. New York: McGraw Hill.

Kepner, C.H., and B.B. Tregoe. 1997. The New Rational Manager: An Updated Edition for a New World. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Research Press.

Larson, C.E., and F.M.J. LaFasto. 1989. Teamwork: What Must Go Right/What Can Go Wrong. Vol. 10, Sage Series in Interpersonal Communication. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications Inc.

Nonaka, I. 1995. “Chapter 16, The Recent History of Managing for Quality in Japan.” In A History of Managing for Quality: The Evolution, Trends, and Future Directions of Managing for Quality, ed. J.M. Juran. Milwaukee, WI: ASQC Quality Press.