Incorporating web-based engagement and participatory interaction into your courses

Abstract:

This chapter presents ideas for delivering online course content and communication in ways that will increase student participation and engagement. Diane Rasmussen Neal discusses options for using social media such as discussion forums, synchronous chat, social networking, and collaborative workspaces to reach students online in exciting ways. Additionally, she outlines advantages and disadvantages of using these tools in class. Maureen Henninger presents a case study of social media use in the forms of (1) providing a mentoring space for incoming students, and (2) embedding social media tools in courses.

Online engagement and interaction: what does it mean?

As university instructors, we are all at least somewhat skilled in engaging with our students when we are in front of a class. Whether you use humour to keep a class of 500 undergraduates awake in English 101 (with varying degrees of success), or you pose thought-provoking questions to your doctoral students over coffee, we are all passionate enough about our fields to pass them down to our students.

But, the equation changes when we start teaching online. I (Diane) have been teaching online since 2004, and I enjoy it, but it’s just different. Personal connections can feel less tangible. You might not ever meet your students in person, and they don’t show up during office hours because they are sending you emails at 2 a.m. instead, in expectation of your response by 6 a.m. You feel overwhelmed by all the communication, and despite the amount of typing you do to keep in touch with your online students you never feel like you’re teaching a class, but rather serving as a robotic secretary at the other end of the Internet. You want to be able to connect with your students, and you want them to develop those peer relationships that are so important in college/university, but you just do not see how that’s possible. Does this sound like you – or like it could be you if you had to teach online?

If so, please do not worry. Based on my conversations with faculty colleagues over the years, these frustrations are quite common. Institutions vary in their levels of support for online courses. Ideally, we would have instructional designers at our disposal, content creation advisers, and teaching assistants to maintain all the conversations and all the grading. But typically, reality sets in – and we’re on our own! Students and colleagues have told me stories about their negative experiences with online courses: the instructor only communicated with students via email; the instructor only sent out a syllabus and told students to get to work; the instructor never responded to messages; the list continues. So what can we do? We call up social media and related engagement techniques.

If you recall my discussion in the introductory chapter, Web 2.0 philosophy encourages participatory conversation, and it somewhat levels the playing field for those involved. As the instructor, it is your job to provide a consistent, reliable springboard of tools and environments for students to explore the material, but they can take it from there. This does mean that your comfortable ‘Lord of the classroom’ approach to teaching changes somewhat, but it is still up to you to lead the engagement. When the materials and the tools are there for students to participate in a conversation as they co-create their own learning experience – individually and collectively – amazing things can happen. Some ways to do this are outlined below.

Lead the conversation, but not too much

In Akin and Neal (2007) we introduced a model of presenting discussion questions in online courses. With each topic, it can be useful to present questions that encourage students to engage with the material and with each other, in a format such as an online discussion forum. However, just like a good research question, a good discussion question has several elements; writing them in appropriate ways encourages discussion in the right direction. We provide tips for designing the following elements: ‘the cognitive nature of the question, the reading basis, any experiential possibility, style and type of question, and finally ways to structure a good question’ (ibid., para. 1). We also suggest that while it is important for the instructor to be ‘present’ in the discussion, an overbearing presence can decrease the chances that students will participate. It is up to you to set this tone.

Keep it fresh but manageable

Today’s students are used to our ‘always-on’ world. Texting, Facebooking, and tweeting is second nature. If you don’t believe me, just observe them walking across campus; they usually do not even look up from their phones as they cross the street! Examining their reality, in which five minutes between texts is an eternity, not providing content to your students on a frequent basis will make them lose interest. Make a social contract with them at the beginning of the semester: they will be expected to report in to class at least once a day, and you will be expected to provide discussion questions, links to relevant websites and other useful items as frequently as possible.

That said, you can’t post links at 3 a.m. To maintain a semblance of a life and to help your students know what to expect from you, I would like to suggest creating a ‘communication policy’ for your syllabus. For example, my communication policy states that I may or may not be available on weekends, holidays, or after 5 p.m. on weekdays. But, I also promise responses within 24 hours, or as soon as possible. Some online faculty hold ‘online office hours’ when they will be available via instant messaging software. Even if students do not choose to contact you, that extra availability can comfort them – and, if they don’t ‘show up’, you can get some writing done while you’re logged in! Email is also a consideration for your communication policy. Students appreciate the ‘instructor immediacy’ (Akin and Neal, 2007) associated with email, and it’s generally reliable, safe and rapid if we respond as quickly as possible. On the other hand, our email inboxes are already clogged with correspondence related to our research and service duties. This is a personal choice, but I encourage students to post course-related questions to the course discussion forum area (in whatever form that might take). When they do that, not only can the entire class benefit from one consistent answer, but sometimes another student will answer the question before I even see it, which increases peer engagement (and saves me time)! If they have a confidential question, I ask that they send me a private message through the learning management system. With this approach, their questions will not clog my inbox and my student communications are naturally organized in time and space.

Make it count

Many of us give participation points for in-person classes, and online classes should not be any different. In fact, I believe that participation should count even more online than in face-to-face classes. Set out your expectations at the beginning of the class, and hold them to these standards. For example, you might expect them to post related links, comment on discussion questions, blog once a week, and log in to weekly chat sessions for 20 per cent of their final grade. The problem with this kind of participation, of course, is that it can be difficult to measure qualitatively, and strict quantitative measures can feel draconian. At the same time, we have similar issues when measuring face-to-face participation. As the instructor, it is your responsibility to set whatever online participation activities you feel are necessary for your subject matter and appropriate for your personal style. The students’ job is to meet those expectations.

Once, a very conscientious student contacted me to ask me whether she was participating ‘enough’. She was one of the most frequent contributors in class, so I told her not to worry. The ones you need to worry about are the ones who never participate; you may have to send them a reality check a few weeks into the class to remind them that an online class is not a ‘do a little bit whenever you feel like it’ kind of course; in fact, it is the opposite. Online learning requires substantial personal motivation, but you can ease this if you provide the tools, content and infrastructure that will make students feel less isolated. As one of my efforts in this direction, I post weekly ‘lessons’. For example, students might be expected to complete the activities and discussions for the previous week’s lesson by Monday evening, and I post the new lesson on Tuesday morning. This routine provides structure in an otherwise relatively unstructured learning environment.

Choose the right tools for the job

From a nuts-and-bolts perspective, there are many tools that help you build opportunities for participatory engagement into your online courses. The options you choose may depend to some extent on your subject matter, the number of students on your course and your available technical support. Let’s explore a few possibilities. Let’s explore a few needs, and a few options.

Giving lectures

At some point, whether online or face-to-face, professors have to lecture; it’s what we do! When I first started teaching online, I wrote PowerPoints and posted them online. Some faculty create PowerPoints with voiceovers for each slide. While these can be familiar and effective, they are ‘one-way’ and don’t promote discussion. You could still present slides and talk about them, if that is what you are comfortable with. But, instead, you could record the activities on your computer screen (the slides, demonstrations, etc.) with a screen recording tool such as Camtasia (http://www.techsmith.com/camtasia.html), upload the video to YouTube or Vimeo and open it up for comments from your students. These could take the form of a podcast or vodcast. This approach would allow your students to access them via RSS feed (see Chapter 1 for more about RSS), download your files to their laptop, iPhone or other compatible device, and listen to them in the time and place that their preferences dictate.

If you are able to meet with your students synchronously (meaning that everyone is together online at the same time and place), you could give lectures via a tool such as Skype (http://www.skype.com), which allows people to hold text chats and group audio calls for free. With Skype, you can add your students as contacts, and then add the students to a ‘group’. You can then ‘call’ or ‘chat’ with the group as a whole – and give your lecture virtually. A nice feature is that Skype also keeps a record of text chats, so students can refer to them later.

An emerging wave of streaming tools, such as http://www.twitch.tv, allows you to broadcast your screen and sound to viewers. You simply download a tool, provide the link to your viewers and lecture away! For a lecture on video games in my social media class, some gamer librarian friends and I provided my students with a live demonstration and narration while playing World of Warcraft. We were able to demonstrate the basics of the game (character creation, completing your first quest), some advanced play (rated battlegrounds) and lead a discussion at the end of the chat. It was a fun, productive session for everyone, and it encouraged students to think critically about video games and how they could play a role in library settings.

Lynne Williams, a co-author of Chapter 6 and the author of Chapter 10, uses Adobe Connect (http://www.adobe.com/products/adobeconnect.html) and Elluminate Live (http://www.elluminate.com/services/training/elluminate_live!/?id=418) to give lectures and hold synchronous discussion, respectively. I do not have personal experience with these tools, but she reports:

Adobe Connect … has a good interface, so you can run your lecture in the center of the screen while keeping an eye on the chat to the left of the screen … we also have … the Elluminate Live platform, which is good for drawing one or two students aside and answering questions ‘live,’ along with slides or demos via watching you walk through actions on your desktop. The good thing about Adobe Connect and Elluminate is that all sessions can be recorded, then stashed as recorded webinars for later viewing by students who may have similar questions.

Blogging is another excellent option for providing lectures. In a blog, you can write your thoughts, link to online readings, embed videos or screencasts, and allow students to comment on your posts. I like to use course blogs as my main method for providing lessons, because every type of material I include can be linked from a weekly blog post. Also, if there are issues that come up during the course – if something proves more difficult than you expected, or you want to provide blanket feedback on an assignment – you can write a special blog post.

Infrastructure options for student engagement and participation

Asking students to create blogs that document their experiences and thoughts during the course can be beneficial. In Neal and Xiao (2011) we explored students’ experiences of blogging for my social media course; you can read a first-hand student view of this particular course in Chapter 12. I used only social media tools to teach social media, but the class was still organized and maintained a predictable structure. The Neal and Xiao paper noted that the unfolding of their learning trajectories could be viewed in their weekly posts. This student’s quote from a different semester of my social media course demonstrates why I find this method of engagement so encouraging:

As I think back on this semester, I remember myself engaging with content in a way that I hadn’t before … I was introduced to a number of tools that I now feel comfortable using … I have enjoyed our weekly Skype chats. It was important for me to ‘hear’ my classmate’s [sic] opinions and ideas about social media in libraries so that I can build on my own thoughts.

(tiredstarlingsocial, 2011, paras 1, 3 and 4)

Utilizing popular social networking and microblogging services is another way to increase active student participation. You could, for example, create a Facebook group, a Twitter hashtag or a Google + hangout. This not only goes where your students already are, but social interaction is naturally built into the tools. With this option, however, you have privacy and identity issues to consider: do you want your students to see your personal profiles and updates, or should you make separate accounts for class purposes? (See Chapter 10 for more on this issue.) Additionally, students may have their own privacy concerns: they may not want their professor to see their social conversations on these networks, and may not want to create separate accounts to keep their identities separate. I will leave this deliberation for you to consider.

Collaborative work tools such as wikis and Google Docs can be a practical option for class projects. Students can use them for group work; this is an important feature in an online classroom setting because students are frequently geographically dispersed. Such tools probably improve the quality of student–student interaction because they give them a shared workspace and they are not subjected to the version control frustrations of sending email attachments. See the section, ‘Wikis in the classroom’, below, for more on this teaching and learning tactic. Collaborative tools and social media sites are also fun options for class activity collaboration; the possibilities are only limited to your pedagogical creativity. Wikis are not the only way to accomplish this. For example, Hoffman and Polkinghorne (2008), within an academic library instructional context, described their use of collaborative Flickr photograph tagging to demonstrate the differences between user-provided tags and library-provided index terms in describing and searching for photographs.

Putting it all together: learning management systems

Along with the use of all these tools comes a quandary: is it too much? With all the places a class can convene, post and comment, will the instructor and students forget which channels of communication are available? One solution to this problem is the use of a learning management system (LMS), which organizes all elements of an online course in one place. Examples of currently popular LMS options include Blackboard (http://www.blackboard.com/), Moodle (http://moodle.org/) and Sakai (http://sakaiproject.org/). They feature options such as the ability for the instructor to post course content, receive and grade assignments, manage student lists, create discussion forums, and so on. As Dalsgaard (2006) notes, integrating social media tools within the structure that an LMS provides is advantageous because LMSs do not provide a social constructivist approach to learning. Frequently, universities require that professors use a particular LMS for online course delivery.

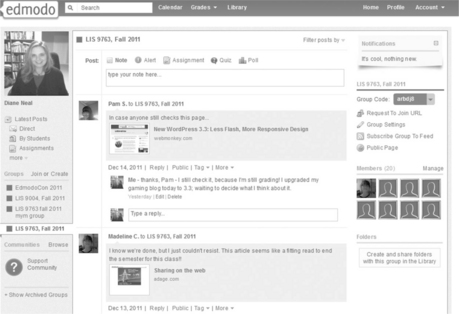

At the time of writing, my university, The University of Western Ontario, uses WebCT (a product that merged with Blackboard), and is moving to Sakai soon. These are institutionally sanctioned systems, and the campus supports the technologies, but faculty are not required to use them for e-learning out of respect for academic freedom. I am fortunate to use Edmodo (http://www.edmodo.com), a ‘social’ LMS. It provides many LMS features such as assignment submission and a grade book, but it also operates very much like a Facebook wall or group. You can create a ‘group’ for each class, and students access it via a code that you provide to the class. Best of all, it’s free and it’s cloud-based, so no campus IT support is required! Figure 8.1 shows an Edmodo group for one of my courses.

I’ve focused on the use of social media for online course delivery but there are many other uses for social media in student engagement. In the remainder of this chapter, Maureen Henninger presents case studies of social media tools at play in her local setting for the purposes of embedding social media tools in courses as well as new student mentoring. The uses of these tools are wonderful, and I especially hope that Maureen’s mentoring case study helps you think creatively about the currently unrealized potential of utilizing these tools in the academy.

Social networking services in the classroom: a case study

Concerns for student apprehension and uncertainty in a new and seemingly chaotic environment and the potential for significant attrition rates led an initiative to set up a mentoring space for the incoming undergraduates in the BA in Communication (Information and Media) programme at the University of Technology, Sydney (UTS). The ubiquity of Facebook (according to Socialbakers, during the week of 24 October 2011, 10,659,580 Australians logged into Facebook)1 makes it an obvious social networking service choice for high-school leavers (Millennials) entering university. The UTS initiative, however, was about more than simply providing a platform for student informal chat and information sharing. It was about building a community of first-year students and providing a platform for mentoring services.

This was done in two steps. Firstly, a small cohort of final-year students was identified, and the students were asked to be mentors to the incoming students, with the aim of having one mentor for 8–10 students. An email was sent out – Do you want to be a mentor? – with the message: ‘it can be as much or as little work as you wish to make it. We will be setting up a Facebook group for the mentors and their “mentorees” so that they can ask questions, share stories, etc., and we would ask you to introduce yourselves to your group of new students.’ Every one of those contacted agreed; in fact, they were very enthusiastic, saying that they would have liked to have had such support when they were ‘newbies’.

Once we had our mentors, Doodle was used to schedule the first (and only) meeting between the academics and mentors. At the same time, the Facebook group was set up, and within 48 hours over 50 per cent of the incoming students had joined. By the middle of the semester, 95 per cent of new students were part of the community (see Figure 8.2). The mentoring programme was then advertised with a post by an academic and the mentors introduced themselves to the community:

Academic: Hey everyone we are setting up a mentoring program – Connie & Sarah are 2 of 9 mentors – more about this program in the next couple of days.

Mentor: Hey guys! I’m Ryan, a 3rd year Info and Media Student with Media as my sub major. I’m also the temp Digital Preservation Officer over at UTS eScholarship for the next few months. It’s great to see you all doing Information and Media as your major. If you have any problems, or just want to have a yarn, feel free to drop me a line.

Mentor: Hey guys! I’m Joanne and I’m currently in my third year of info & media and am also doing a law degree. Feel free to drop by if you have any questions or any trouble – or even if you want to vent about your frustrations :) looking forward to working with you!!

In the first week of the programme, each mentor set up a face-to-face meeting with their mentees in which they chatted and swapped email addresses and phone numbers in case they wanted to ask or discuss a situation of a more sensitive nature. In the first week of the semester, the mentors were very active in monitoring and answering fairly routine coursework and ‘how to’ questions posted on Facebook.

Student: hi everyone, i couldnt come into uni today because i’m sick and i was wondering if anyone has notes from the Creative Information Design lecture that they could email me?

Mentor: Hey Guys. Generally you can find the lecture slides and tutorial notes on UTSOnline in the folder for that week.

Questions of a more personal nature were not posted on Facebook. According to the mentors, these questions were emailed or discussed face-to-face over coffee or a beer.

It was envisaged that there would be little input from the academics but by the middle of the semester it became obvious that Facebook was the preferred method for asking questions of tutors and lecturers. In spite of advertising the fact that the Blackboard discussion boards were the Faculty’s preferred vehicle for questions and answers about classes, Blackboard was rarely used for communication purposes. In fact, over the three core subjects in the major (Information and Media), there were only two questions, one of which was from a student who did not join the Facebook group.

Although no formal survey was carried out to evaluate the mentoring programme, the mentors reported informally on a few instances of ‘tears’ and personal questions, for the most part via email. Anecdotally, the students reported that they found the idea of having a mentor ‘very welcoming’, and that it ‘made some of the settling-in stages much easier’. At the end of the first semester, the attrition rate was 3.9 per cent, a big improvement on the year before, and we would like to think that the Facebook mentoring programme may have played some part in this.

Wikis in the classroom

Most academic institutions now use online learning environments such as the proprietary Blackboard or the open source systems such as Sakai and Moodle. The following three case studies show ways in which social media tools can be embedded in coursework, using the wiki space of Blackboard in order to build collaboration and participatory interaction. At UTS, this is done within both the postgraduate and undergraduate degrees, and the following case studies are from the Information and Knowledge Management programme: two from postgraduate subjects and the third from an undergraduate subject. The postgraduate degrees at UTS can be completed either part time or full time, and indeed many of the students attend class in the evening as they are employed and often have work commitments which interrupt their studies. As Diane noted, this situation can pose difficulties for students’ group work and assignment presentation. Here are two case studies which, using online spaces (wikis), enable students to fully participate in the subject in a flexible manner not bounded by time or space. Both involve group work. The first demonstrates the creation of a body of new knowledge; the second, an online presentation and peer evaluation of a group assignment.

Case study 1

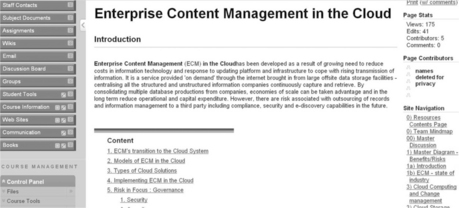

There are two subjects in the Information and Knowledge Management degrees that revolve around the use and management of information objects and knowledge: Knowledge Management in the Organization and Enterprise Content Management. Embedded in both is the notion of sharing information and knowledge; in particular, the concept of communities of practice. In order to emulate and give a reality to online communities of practice, there is a group assignment in which members of the group share ideas and build content in a wiki environment over a period of several weeks. One of the criteria against which the students are assessed is to ‘work collaboratively in a group to design content by writing and contributing ideas and research uses’.

Figure 8.3 shows an example of a resource on cloud enterprise content management (ECM). The wiki provided the facilities for uploading diagrammatic documentation (mind and concept maps), group contract agreements and textual content, which was easily edited.

The comments area within the Blackboard wiki was used for editorial and planning processes, and the group noted that for the most part this was successful. Other comments highlighted the well-known challenges of virtual collaboration: ‘our face-to-face team meeting was really interesting and valuable but not recorded; it was a challenge to bring the same energy into our wiki based discussions’, and ‘understanding the balance between the neutral voice needed for the master wiki and the opinion allowed in the discussions [sic]’.2 Overall, across all the groups in these subjects, the wiki environment enabled the collaborative, at times innovative, creation of new information resources without the constraints of time and location.

Case study 2

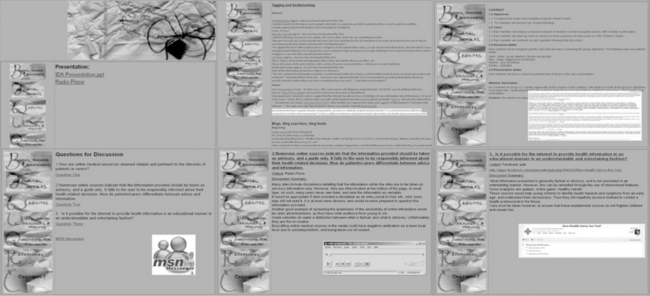

In a subject, Investigative Research in the Digital Environment, students, in pairs, have to deconstruct an information product (an environmental scan, a briefing report, for example) in order to tease out the research processes and data sources. Once done, this has to be presented to the class. Again, because of work and time constraints the work is done collaboratively in a wiki. The final work, generally a PowerPoint presentation, is made public to the entire class three days before the assignment is due. At this time, all students must go through the presentations and make evaluative comments in the wiki (see Figure 8.4).

In face-to-face presentations, students are often reticent to offer critical comments, and, particularly at night when they are tired, often don’t want to take the time to do so. However, in the online environment, several interesting things happen. As the time frame is three days, students have the time to really examine the presentations in order to make considered comments. Not only do they make good critical comments, they tend to ask questions, such as ‘How did you do that?’ and ‘What was your thinking behind the validation of that dataset?’, thus setting up a conversation not only with the original presenters, but with the rest of the class who offer further insights and suggestions. Finally, the students have all commented in the subject feedback that they find this method very satisfying because of the ability to have a conversation in which not only do they get good feedback, but they also get tips and strategies for the research processes – the sharing of information and knowledge.

Tools for virtual conferences: a case study

First-year undergraduate students in a BA in Communication (Information and Media) programme had a final assignment that required them, in groups of three, to collaborate in creating a digital poster which critically examined a theme or issue associated with information discovery and access. A digital poster was deemed to be any type of digital presentation, and they were encouraged to be creative and to use any tool or technique they considered effective to ‘get the message across’. The week before the conference each group had to post three questions concerning their poster topic for a three-day online discussion by the class (the virtual conference). This discussion was then synthesized and incorporated into the group’s final poster presentation, which was uploaded to the class wiki for further discussion.

Students were allowed to use any collaboration tool for discussing and designing the poster as well as sharing their research. Blackboard collaborative spaces, wikis, discussion boards and synchronous chat were made available and all three were used; in addition, students used email and set up Facebook groups. Unfortunately, no statistics were kept on this part of the communication process.

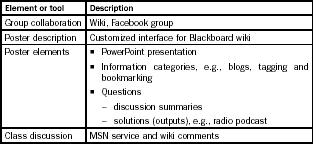

The following is an example of one digital poster on the topic of ‘Access to online health information by patients and carers: risks and benefits’. The group who created this poster made extensive use of social media tools (see Table 8.1) and, coincidently, much of the online health information for their annotated bibliography came from social networking sites (SNSs) as well as from traditional scholarly and/or authoritative resources.

Table 8.1

List of elements and tools incorporated into a digital poster presentation at a virtual conference

The group used Facebook to get started on the project, but soon moved over to the Blackboard wiki space for composing and editing content – the traditional use of a wiki – and commenting on and discussing the content and the project. They conceived their poster as a wiki (built inside the Blackboard wiki space) that had a customized interface with the following elements and content:

![]() navigation by resource types (blogs, tagging and bookmarking services, journal articles, websites, and wiki and SNSs);

navigation by resource types (blogs, tagging and bookmarking services, journal articles, websites, and wiki and SNSs);

![]() discussion questions posted in the wiki, but class discussion done via MSN Messenger service;

discussion questions posted in the wiki, but class discussion done via MSN Messenger service;

![]() a summary of the class discussion of each question, done by an analysis of the MSN logs;

a summary of the class discussion of each question, done by an analysis of the MSN logs;

![]() three creative solutions (outputs) for dissemination of health information to patients and carers; and

three creative solutions (outputs) for dissemination of health information to patients and carers; and

![]() an overview of the poster in the form of a PowerPoint presentation.

an overview of the poster in the form of a PowerPoint presentation.

Of particular interest is the innovative ‘output’ for two of the questions:

![]() Numerous online sources indicate that the information provided should be taken as advisory and a guide only. It falls to the user to be responsibly informed about their health-related decisions. How do patients/carers differentiate between advice and information?

Numerous online sources indicate that the information provided should be taken as advisory and a guide only. It falls to the user to be responsibly informed about their health-related decisions. How do patients/carers differentiate between advice and information?

![]() Is it possible for the Internet to provide health information in an educational manner in an understandable and entertaining fashion?

Is it possible for the Internet to provide health information in an educational manner in an understandable and entertaining fashion?

The group analysed the logs of the MSN class discussion of these two questions and decided that, in the first case, a radio podcast would be an appropriate resource and, in the second, an online health survey would be appropriate. The group wrote, recorded and embedded a podcast, and, using the Facebook application, QuizCreate, designed and embedded the survey, both of which can be seen in the collage of the poster elements (see Figure 8.5). It should be noted that the output for the first question was a series of well-designed postcards.

Overall, this case study provides a striking demonstration of Millennials’ familiarity and ease with social media services, and, even more impressively, their ability to use them in a creative and innovative way to communicate serious ideas and issues.

Conclusions

This chapter has reviewed a suite of choices for providing online engagement and participatory tools to your students. A point to reiterate: while some of the tools discussed (such as certain learning management systems) require your institution’s financial and technical support, many of these tools are free and cloud based, which means you can start using them immediately, with minimal start-up time and expense required. It is a satisfying feeling to know that your students are working with emerging technologies in their educational journeys; technologies that matter to their generation and to society. You are also providing them with new forms of digital literacy that they may not possess yet. While they might text and Facebook and tweet all day, this does not necessarily mean that they know which tool to use for the work task at hand, or how to use them appropriately. You can provide a safe environment for them to develop these types of critical thinking skills as you provide the infrastructure and support for them to learn these essential 21st century abilities. This might sound cliched but for your students, and their eventual employers, the future is now.

References

Akin, L., Neal, D., CREST + model: writing effective online discussion questions. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching. 2007;3(2). Retrieved from. http://jolt.merlot.org/vol3no2/akin.htm

Dalsgaard, C. Social software: e-learning beyond learning management systems. 2006 Retrieved from. http://www.eurodl.org/materials/contrib/2006/Christian_Dalsgaard.htm

Hoffman, C., Polkinghorne, S. Sparking Flickrs of insight into controlled vocabularies and subject searching. In: Godwin P., Parker J., eds. Information Literacy Meets Library 2.0. London: Facet Publishing; 2008:117–123.

Neal, D., Xiao, L., The use of weblogs in LIS online courses: a case studyHuvila I., Holberg K., Kronqvist-Berg Maria, eds. Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Science and Social Media 2011 (ISSOME 2011). Åbo/Turku, Finland: Åbo Akademi University:, 2011:107–116 Retrieved from. http://issome2011.library2pointoh.fi/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/ISSOME2011-proceedings.pdf

tiredstarlingsocial tiredstarlingsocial. 2011 Retrieved from. http://tiredstarling.social.wordpress.com/

1For social media statistics, including weekly updates of Facebook statistics, see Socialbakers http://www.socialbakers.com/.

2This facebook group is a closed group and can not be accessed by the public (http://www.facebook.com/#!/groups/202528896423886/members/).