29 Disaster risk reduction informing climate change adaptation

Social capital in Agüita de la Perdiz

Introduction

Climate change is a major issue that human societies are facing in the twenty-first century. The Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change (IPCC) presents evidence of changes in climate-related hazards and extreme events, as well as for future projections in terms of frequency, magnitude and duration (IPCC, 2007; IPCC, 2012). Even if ambitious mitigation efforts were undertaken, it is expected that societies will face significant and changing risks, and more uncertainty (Reilly et al., 1994; Sterr, 2000). Therefore, adaptation has emerged as critical when responding to climate change and climate-related hazards events (Debels et al., 2009).

Multiple links between climate change adaptation (CCA) and disaster risk reduction (DRR) have been reported in the literature (Thomalla et al., 2006; Aldunce et al., 2008; O’Brien et al., 2008; Adger et al., 2009a; Pelling and Schipper, 2009). One of the most salient of these links is that CCA could be enhanced by DRR research, experience, and practice (Pelling and Schipper, 2009). The local level is an area in which the DRR community has a long history and a large amount of experience (O’Brien et al., 2008). It has also been stressed that the local level is where DRR has been most effective and where the links to adaptation are most apparent (Pelling and Schipper, 2009). Further, it is becoming increasingly apparent that adaptation efforts need to be implemented at the local level. Therefore, there is much to gain from the work of the DRR community at the local level. What has been especially instructive are studies that focus on enabling conditions and barriers for an effective response to climate-related disasters.

This chapter presents a local case study from Agüitas de la Perdiz Sur, a community in Chile that in 2005 was affected by a destructive and extreme rainfall event that had no precedent in 145 years.

Contrary to what was expected for such a severe hazard that was coupled with extremely vulnerable conditions, no deaths and only a few injuries were reported. Therefore, we were curious to explore what enabled this community to overcome the multiple barriers to an effective response. Information gathered in the field reveals that social capital was the decisive element that helped the community to protect their lives and to cope with a disaster of such magnitude. How this happened and how social capital was useful for them to overcome those barriers is discussed in this chapter. We argue that there are important lessons to be learned from this case to inform CCA.

First, the chapter examines the links between DRR and CCA that are reported in the literature. Second, the methodological framework is presented, as well as the case study in terms of geographical and socio-economic characteristics. Third, the discussion focuses on social capital, and aspects related to it, as this is the most relevant enabler for overcoming the barriers for an effective response presented in the case study. Fourth, some reflections are presented.

Linking disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation

The patterns of some climate-related hazards are acknowledged as changing (IPCC, 2012), and this partially explains the increase in hydro-meteorological disasters over the last two decades (UN/ISDR, 2004; CRED, 2009; Peduzzi et al., 2009), with rising damage costs of extreme hydro-meteorological events (Okuyama and Chang, 2004; Pielke et al., 2008). Nevertheless, changes in hazards should not be considered as the only driver for increasing disastrous events (Gaillard, 2010; Lavell, 2011). There are multiple stressors and drivers that generate vulnerability (Eriksen et al., 2011; Lavell, 2011) and changes in climatic conditions tend to disproportionately affect more severely vulnerable populations and developing countries (Haddad, 2005; Roberts and Parks, 2006), as their vulnerability is determined by physical, social, economic and environmental factors (Wisner et al., 2004; Leichenko and O’Brien, 2008). This changing risk picture and the uncertainty that comes with it complicate the decision making processes. Additionally, in many countries where extreme events occur so frequently, coping capacities are already overwhelmed and this has negative effects on long-term development (Thomalla et al., 2006).

At the start of the century the disaster risk reduction and the climate change adaptation communities worked in isolation (Thomalla et al., 2006), but recently more efforts have aimed to link these two fields (see for example Schipper and Pelling, 2006; Venton and La Trobe, 2008; O’Brien et al., 2008; Pelling and Schipper, 2009). The special report of the IPCC “Managing the risk of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation” (IPCC 2012) is a good example of such collaboration, where more than one hundred researchers and stakeholders were brought together to assess the current knowledge and experience on responses to changing risks in a changing climate.

There are multiple ways, in both theory and practice, in which CCA and DRR are linked. First, some authors consider that adaptation is a matter of risk management; it is about the future possibilities of the occurrence of a threat and its consequences and impacts (Pelling and Schipper, 2009; Birkmann et al., 2010). Second, disasters open a window of opportunity for change. Individuals and organizations tend to be more open to changing behaviors after a disaster, and this is an opportunity to learn and adapt, and to include climate change considerations (Pelling and Schipper, 2009). Third, using lessons learned by the DRR community can enhance CCA policy and practice. The DRR community has a long history of responding and adapting to climate-related hazards (O’Brien et al., 2008) and many studies have focused on lessons learned from disasters (see for example McEntire, 2002; Lavell, 2009; Moore et al., 2009; Birkmann et al., 2010). These studies can be useful in examining and informing literature and praxis about enablers and barriers for CCA (Adger et al., 2009b). By using these experiences, the CCA community can draw on some existing mechanisms, institutions and organizations created for DRR, avoiding re-inventing the wheel, wasting time, and creating overlaps (Pelling and Schipper, 2009). Following the recognition that CCA could be enhanced by DRR experiences, we discuss a case study that focuses on examining enablers and barriers for DRR in the next sections.

Background and methodology

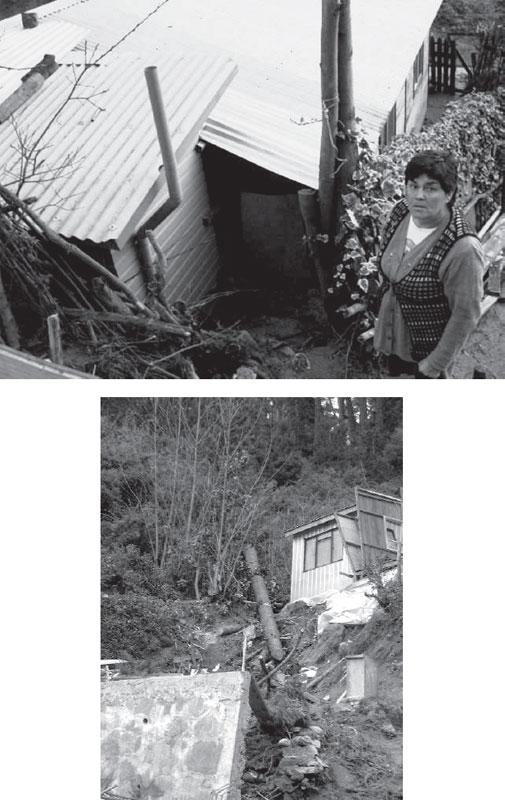

The methodology is a case study conducted in the community of Agüita de la Perdiz Sur, located in downtown Concepción, the second largest city in Chile with a population of 848,023 habitants (INE, 2005). On June 26, 2005, an above-normal precipitation event of 162.2 mm in 24 hours took place, representing a record in 142 years. In this area the normal precipitation for the month of June is 218 mm, and in June 2005 it was 511 mm. The event affected the population and infrastructure. Among the 282 houses in the community, almost 100 houses were completely or partially destroyed by landslides (see Figure 29.1) (DMC, 2005; ONEMI, 2005).

The rationale for selecting Agüita de la Perdiz Sur as a case study is based on the following arguments. Climate change will exacerbate the inequity and poverty conditions of the most vulnerable population in developing countries (Barnett, 2003), and as in the case of Agüita de la Perdiz, many of these populations are already experiencing frequent disasters that are overwhelming their coping capacities (Thomalla et al., 2006). Agüita de la Perdiz Sur is an example where people not only live in a risky area, but are also exposed to multiple stressors and barriers for an effective response.

Houses in this area are built on the high sloped Caracol hill (see Figure 29.2), classified as a high landslide risk area (Mardones and Vidal, 2001; Hauser, 2005). Nonetheless, as in many other places in the developing world, the area has been colonized by illegal settlers searching for a place to live (Tribuna del Biobío, 2005). The population of this community is also socially vulnerable because of poverty, inadequate living conditions and low educational levels. With a hazard of this magnitude that developed mostly during the night and affected a population living in a risky area, it is remarkable that only a few injuries and no deaths were reported (ONEMI, 2005). Therefore, this case study is an opportunity to learn about enablers and barriers for DRR.

A multilevel analysis was carried out with emphasis on the local context. The methods consisted of a document review; data base analysis; walks on the site; and semi-structured in-depth interviews with the affected population and government personnel involved in DRR.

Social capital as an enabler and barrier in Agüita de la Perdiz

The case of Agüita de la Perdiz Sur illustrates well some enabling conditions for DRR. The research findings show that the most relevant enabler that helped people to respond to the June 26 disaster is undoubtedly social capital. There are multiple definitions of this contested concept (see for example Loury, 1977; Coleman, 1988; Putnam, 1993). We used Bourdieu’s (1985: 248) definition of social capital, understood as the aggregate of the actual or potential resources which are linked to a durable network of relationships. In the context of disasters, three key dimensions of social capital are sense of community, place attachment, and citizen participation (for definition of theses concepts see Tartaglia, 2006; Norris et al., 2008). Interviewees expressed arguments that are related to each of these three dimensions.

Sense of community and place attachment

Sense of community and place attachment has a strong presence within Agüita de la Perdiz Sur and we consider them mainly as enablers. However, they have also contributed to create barriers, as discussed below. Most respondents expressed that they feel part of and integrated into the community, and many also explained that they have close relationships with other members of the community as family or friends. Something that emerged strongly is how the physical characteristics of the place, in which this community lives, have shaped and contributed to a sense of belonging. On the one hand, interviewees stressed that they share living in a risky place, and consequently they all share being exposed to disasters and need each other in order to survive. On the other hand, they explained that because the place is surrounded by hills and because the only way to enter is through two main streets, this has created a sense of living in a small village, where everybody knows each other, even though they are in the downtown area of a big city. Having this sense of belonging has resulted in a proactive community that takes care of each other and that has established strong networks within the community. For example, during the June landsides community members organized a shelter in the local school and in some houses to gather affected neighbors. The community helped evacuate older people, and in general was effective in self-responding in a timely manner. Not having to wait for external help was crucial during this disaster as the city was in chaos and the emergency services were overwhelmed.

These results can also be found in the literature. A sense of belonging decreases people’s vulnerability and improves their effectiveness in responding to disasters (Paton and Johnston, 2001; Pearce, 2003). This is achieved by increasing access and utilization of social networks, and by facilitating community involvement in disaster prevention, mitigation, and responses (Paton and Johnston, 2001; Norris et al., 2008).

Undoubtedly, sense of community has had positive outcomes in the case study. Nevertheless, it has also had a negative implication as it has constrained the relocation of the community to less risky areas; we consider this implication as a barrier to effective responses. As stated in the literature, poverty conditions force people to use marginal and risky terrains for housing and other needs (Osti, 2004). This is the case for people in the community of Agüita de la Perdiz, as they have illegally occupied terrains that are classified as high risk for landslides. In the 1970s and 1980s, several attempts were made by the government to move people from Agüita de la Perdiz Sur and give them houses outside the city. However, people returned to their homelands, mainly for two reasons. First, they wanted to be closer to downtown Concepción to search for work opportunities and to decrease costs such as transportation. Second, being part of the social networks in the Agüita de la Perdiz community is part of their coping strategies against poverty. The implication of these results concur with what has been stated in the literature; that people living in risky areas frequently return to disaster prone areas (Pelling and Schipper, 2009), as in many cases the strong sense of belonging and levels of poverty result in decisions to live in places at risk (Christoplos et al., 2009).

Citizen participation

Citizen participation is a key element to decrease people’s vulnerability and to improve DRR by means of improving problem identification and problem-solving strategies within local communities (Pearce, 2003; Osti, 2004). On-site verification shows that community participation exists in Agüita de la Perdiz Sur, that people in the community self-organize in the face of disasters, and that a number of different members of the community play a meaningful role. Therefore, based on this case study, we consider citizen participation as an enabler for DRR. A critical factor that underpins citizen participation in the study area is the presence of strong leaders within the community. Results of our research concur with what has been described elsewhere (Norris et al., 2008) in the sense that these leaders have a strong place attachment.

Leadership not only emerged as an important enabler for DRR in the case study, but also has helped to overcome one of the most salient barriers presented; the insufficient consideration and inclusion of the community by government agencies in charge of disaster management. Even though a formal institution that supports community participation exists, the Civil Protection National Plan (CPNP) (the CPNP replaced the former “Emergency National Plan”), local people have not been sufficiently included in the managerial system. The CPNP states that “participation should constitute a process by itself, starting at the local level and led by the county, because this is the administrative level that is closest to the local people” (República de Chile, 2002: 10).

Interviewees mentioned the importance of different members of the community taking a lead in the responses during and after the disaster. For example, community leaders organized the emergency brigade that was constituted by local people and ensured that all affected neighbors received adequate and timely aid and support. We find, as elsewhere in the literature, that when civilians are insufficiently included in formal institutions, as in the case of Agüita de la Perdiz, informal leaders have an even more important role to play (Moser and Ekstrom, 2010). The presence of community leaders has also been reported as one important enabling condition for adaptation to climate change (Moser and Ekstrom, 2010).

Even though the presence of leaders within the case study community has been an important enabler, this should not be used as a justification to not invest greater efforts into improving formal participation by the community. Arguments that underpin this are first, that DRR is best facilitated when government initiatives include working in partnership with civil society at different levels (Pelling and Schipper, 2009). For example, a critical aspect in achieving effective DDR is that community members, participating in formal committees, have the opportunity for their opinions and point of view to be considered (Newport and Jawahar, 2003). Second, in Agüita de la Perdiz Sur the link between community and public agencies has been weak, mainly because public agencies do not effectively engage the community in DRR decision making and actions. CCA literature also points out that in order to scale-up local efforts and successes, it is necessary to have supporting institutions at the local and national level (Pelling and Schipper, 2009).

Third, participation and cooperation during disasters should also be framed as an opportunity to build relationships, and to dispel mistrust and hostility between public organizations and also within the community (Trim, 2004). For the successful involvement of the local community in disaster risk reduction, roles, responsibility and coordination needs to be clearly defined and agreed upon (Newport and Jawahar, 2003). In Chile, the CPNP proposes a way of organizing tasks that includes definition of roles, as well as political, legal, technical and operational responsibilities. Nevertheless, different stakeholders working on DRR in Agüita de la Perdiz Sur have not always followed what the CPNP states, and we observed also that cooperation and coordination between different stakeholders does not always exist. Lack of both coordination and collaboration hamper the planning and the management of disasters.

Local knowledge

Another pattern that strongly emerged from the interviews is the role of local knowledge as an enabler for DRR. Over time people from Agüita de la Perdiz Sur have developed different ways of coping with disasters based on knowledge and understanding of the environment that surrounds them. For example, interviewees explained that the experience gained from having faced several landslides during past winters, has contributed to accumulate knowledge in regards to which places are more susceptible to landslides, and who are the most vulnerable within the community. This knowledge served them well during the extreme rainfall in 2005, as people were able to prioritize the evacuation starting with those most vulnerable or living in the most exposed places within the area. People also stressed that, based on the experience of living in the place, they realized during the first hours of the event that this was outside anything they had experienced before. This allowed them to act in a timely manner by alerting others and organizing the response, avoiding a situation that could easily end in complete chaos, especially as the event happened during the night. These results concur with what has been stated in the disaster management literature, that knowledge gained by experiencing recurring disasters can result in positive outcomes (Paton et al., 2000; Pearce, 2003). In a similar way, local knowledge based on observations of the physical environment has been described as a fundamental condition for adaptation (Olsson and Folke, 2001; Berkes, 2007; Eriksen et al., 2011).

Final remarks

The case Agüita de la Perdiz Sur presented in this chapter offers a concrete example in which enabling conditions for and barriers to disaster risk reduction (DRR) can be extrapolated to climate change adaptation (CCA). It shows that social capital manifested through a sense of community, place attachment and citizen participation play a key role for enabling DRR. Additionally, local knowledge is found to be an important enabler for DRR in the study area. This local knowledge, based on the experience of living in a disaster-prone area and on observing the local physical environment, is a fundamental condition for DRR and is useful in informing CCA.

Even though a sense of community and place attachment are crucial enablers for DRR in this case study, they can also become barriers. Both sense of community and place attachment underpin the decisions made to live in and return to a risky place and thus ignoring the options of relocation offered by government agencies. Another important barrier is that existing governance arrangements have been unsuccessful in sufficiently engaging the affected population.

To improve DRR in this area further efforts are needed. The most urgent one is to foster engagement of citizens in formal institutions. We argue that efforts to tackle this should recognize the special characteristics of this community such as the presence of natural and informal leaders, strong social capital, a sense of community, and local knowledge.

The case study presented here is an example of how a self-organized community that has developed social capital can be successful in decreasing their vulnerability. However, this should never be used as an excuse to delay further efforts towards sustainable adaptation; including aspects of poverty reduction, social justice, and environmental integrity. There is an urgent need to overcome these barriers not only due to the high vulnerability, but also because future vulnerability is expected to increase due to climate change.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thanks the participants from the case study, for their generosity and willingness to participate. This publication received the support of and is a contribution to FONDAP #1511009.

Adger, W., Lorenzoni, I. and O’Brien, K. (2009a) Adapting to Climate Change: Thresholds, Values, Governance, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Adger, W.N., Dessai, S., Goulden, M., Hulme, M., Lorenzoni, I., Nelson, D.R., Naess, L.O., Wolf, J. and Wreford, A. (2009b) ‘Are there social limits to adaptation to climate change?’, Climatic Change, 93: 335–354.

Aldunce, P., Neri, C. and Debels, A. (2008) ‘Aplicación del índice de utilidad de prácticas de adaptación en la evaluación de dos casos de estudio en América Latina’, in Aldunce, P., Neri, C. and Szlafsztein, C. (eds) Hacia la evaluación de prácticas de adaptación ante la variabilidad y el cambio climático, Belem: NUMA/UFPA.

Barnett, J. (2003) ‘Security and climate change’, Global Environmental Change-Human and Policy Dimensions, 13: 7–17.

Berkes, F. (2007) ‘Understanding uncertainty and reducing vulnerability: Lessons from resilience thinking’, Natural Hazards, 41: 283–295.

Birkmann, J., Buckle, P., Jaeger, J., Pelling, M., Setiadi, N., Garschagen, M., Fernando, N. and Kropp, J. (2010) ‘Extreme events and disasters: A window of opportunity for change? Analysis of organizational, institutional and political changes, formal and informal responses after mega-disasters’, Natural Hazards, 55: 637–655.

Bourdieu, P. (1985) ‘The forms of capital’, in J. Richardson (ed.) Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, New York: Greenwood.

Chistoplos, I., Anderson, S., Arnold, M., Galaz, V., Hedger, M., Klein, R. and Le Goulven, K. (2009) The Human Dimension of Climate Change: The Importance of Local and Institutional Issues, Stockholm: Commission on Climate Change and Development.

Coleman, J. (1988) ‘Social capital in the creation of human capital’, American Journal of Sociology, 94: 95–120.

CRED (2009) Estimated damages (US$ billion) caused by reported natural disasters 1900–2009, Center for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters, EM-DAT The International Disaster Database.

Debels, P., Szlafsztein, C., Aldunce, P., Neri, C., Carvajal, Y., Quintero-Angel, M., Celis, A., Bezanilla, A. and Martinez, D. (2009) ‘IUPA: a tool for the evaluation of the general usefulness of practices for adaptation to climate change and variability’, Natural Hazards, 50: 211–233.

DMC Dirección Meteorologica de Chile (2005) ‘Boletín climatológico’, in G. Torres (ed.) Volumen XXI N°6 Junio de 2005, Santiago: Dirección Meteorológica de Chile.

Eriksen, S., Aldunce, P., Bahinipati, C.S., D’Almeida, R., Molefe, J. I., Nhemachena, C., O’Brien, K., Olorrunnfemi, F., Park, J., Sygna, L. and Ulsrud, K. (2011) ‘When not every response to climate change is a good one: Identifying principles for sustainable adaptation’, Climate and Development, 3: 7–20.

Gaillard, J.C. (2010) ‘Vulnerability, capacity and resilience: Perspectives for climate and development policy’, Journal of International Development, 22: 218–232.

Haddad, B. (2005) ‘Ranking the adaptive capacity of nations to climate change when socio-political goals are explicit’, Global Environmental Change, 15: 165–176.

Hauser, A. (2005) Informe geológico geotécnico, preliminar: sectores Agüita de la Perdiz y Cerro La Pólvora, Concepción, VIII Región. Santiago, Chile: SERNAGEOMIN.

INE (2005) Censo 2002: ciudades, pueblos y aldeas, Santiago de Chile: Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas de Chile.

IPCC (2007) Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis, Contribution of Working Group I to the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, in S. Solomon, D. Qin, M. Manning, A. Chen, M. Marquis, K. Averyt, M. Tignor and H. Miller (eds), Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

IPCC (2012) Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation, A special report of Working Groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lavell, A. (2009) Local Disaster Risk Reduction: Lessons from the Andes, Lima: Secretaría General de la Comunidad Andina, Proyecto PREDECAN.

Lavell, A. (2011) Desempacando la adaptación al cambio climático y la gestión del riesgo: buscando las relaciones y diferencia, una crítica y construcción conceptual y epistomológica, Secreataria General de la FLASCO y La Red para el Estudio Social de la Prevención de Desastres en América Latina.

Leichenko, R. and O’Brien, K. (2008) Environmental Change and Globalization: Double Exposure, New York: Oxford University Press.

Loury, G.C. (1977) ‘A dynamic theory of racial income differences’, in P.A. Wallace and A.M. La Mond (eds) Women, Minorities and Employment Discrimination, Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Mardones, M. and Vidal, C. (2001) ‘La zonificación y evaluación de los riesgos naturales de tipo geomorfológico: Un instrumento para la planificación urbana en la ciudad de Concepción’, EURE, 27: 97–122.

McEntire, D. (2002) ‘Coordinating multi-organisational responses to disasters: Lessons from the March 28, 2000, Fort Worth Tornado’, Disaster Prevention and Management, 11: 369–379.

Moore, M., Trujillo, H.R., Stearns, B.K., Basurto-Davila, R. and Evans, D.K. (2009) ‘Learning from exemplary practices in international disaster management: A fresh avenue to inform US policy?’, Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, 6: Article 35.

Moser, S.C. and Ekstrom, J.A. (2010) ‘A framework to diagnose barriers to climate change adaptation’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107: 22026–22031.

Newport, J. and Jawahar, G. (2003) ‘Community participation and public awareness in disaster mitigation’, Disaster Prevention and Management, 12: 33–36.

Norris, F.H., Stevens, S.P., Pfefferbaum, B., Wyche, K.F. and Pfefferbaum, R.L. (2008) ‘Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness’, American Journal of Community Psychology, 41: 127–150.

O’Brien, K., Sygna, L., Leichenko, R., Adger, N., Barnett, J., Mitchell, T., Schipper, L., Tanner, T., Vogel, C. and Montreux, C. (2008) Disaster Risk Reduction, Climate Change Adaptation and Human Security, A Commissioned Report for the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Oslo: University of Oslo.

Okuyama, Y. and Chang, S. (2004) Modeling Spatial and Economic Impacts of Disasters, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer.

Olsson, P. and Folke, C. (2001) ‘Local ecological knowledge and institutional dynamics for ecosystem management: A study of Lake Racken Watershed, Sweden’, Ecosystems, 4: 85–104.

ONEMI (2005) Informe consolidado. Sistemas frontales sucesivos: 10 mayo–15 julio 2005, Santiago, Chile: Oficina Nacional de Emergencia, Ministerio del Interior.

Osti, R. (2004) ‘Forms of community participation and agencies’ role for the implementation of water-induced disaster management: protecting and enhancing the poor’, Disaster Prevention and Management, 13: 6–12.

Paton, D. and Johnston, D. (2001) ‘Disasters and communities: vulnerability, resilience and preparedness’, Disaster Prevention and Management, 10: 270–277.

Paton, D., Smith, L. and Violanti, J. (2000) ‘Disaster response: risk, vulnerability and resilience’, Disaster Prevention and Management, 9: 173–179.

Pearce, L. (2003) ‘Disaster management and community planning, and public participation: How to achieve sustainable hazard mitigation’, Natural Hazards, 28: 211–228.

Peduzzi, P., Dao, H., Herold, C. and Mouton, F. (2009) ‘Assessing global exposure and vulnerability towards natural hazards: The Disaster Risk Index’, Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 9: 1149–1159.

Pelling, M. and Schipper, L. (2009) ‘Climate adaptation as risk management: Limits and lessons from disaster risk reduction’, IHDP Update, 2: 29–34.

Pielke, R., Gatz, J., Landsea, C., Collind, D., Saunders, M. and Musulin, R. (2008) ‘Normalized hurricane damage in the United States: 1900–2005’, Natural Hazards Review, 9: 29–42.

Putnam, R.D. (1993) Making Democracy Work: Civic Transition in Modern Italy, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Reilly, J., Hohmann, N. and Kane, S. (1994) ‘Climate-change and agricultural trade – who benefits, who loses’, Global Environmental Change-Human and Policy Dimensions, 4: 24–36.

República de Chile (2002) Plan nacional de protección civil, Santiago de Chile: Ministerio del Interior.

Roberts, J. and Parks, B. (2006) A Climate of Injustice: Global Inequality, North-South Politics, and Climate Policy, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Schipper, L. and Pelling, M. (2006) ‘Disaster risk, climate change and international development: Scope for, and challenges to, integration’, Disasters, 30: 19–38.

Sterr, H. (2000) ‘Implications of climate change on sea level’, in J. Lozan, H. Grassl and P. Hupfer (eds) Climate of the 21st Century: Changes and Risks, Hamburg: Wissenschaftliche Auswertungen.

Tartaglia, S. (2006) ‘A preliminary study for a new model of sense of community’, Journal of Community Psychology, 34: 25–36.

Thomalla, F., Downing, T., Spanger-Siegfried, E., Han, G.Y. and Rockstrom, J. (2006) ‘Reducing hazard vulnerability: towards a common approach between disaster risk reduction and climate adaptation’, Disasters, 30: 39–48.

Tribuna del Biobío (2005) ‘Agüita de la Perdiz: lo que puede hacer la comunidad organizada’, Concepción, Tribuna del Biobío. Online. Available HTTP: http://www.tribunadelbiobio.cl/one_news.asp?IDNews=543&NewsEditions=19 (accessed 14 September 2006).

Trim, P. (2004) ‘An integrative approach to disaster management and planning’, Disaster Prevention and Management, 13: 218–225.

UN/ISDR (2004) Living with Risk: A Global Review of Disaster Reduction Initiatives, Geneva: United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction.

Venton, P. and La Trobe, S. (2008) Linking Climate Change Adaptation and Disaster Risk Reduction, Teddington: Tearfund.

Wisner, B., Blaikie, P., Cannon, T. and Davis. I. (2004) At Risk: Natural Hazards, People’s Vulnerability and Disasters (2nd ed), London and New York: Routledge.