CHAPTER 8

Creativity and the Balance Sheet: Securing Funding for Imaginative Capabilities

If a company has a powerful creative ability and can produce innovations that lead to profitability, or at least has the potential to generate profits in the future, it will attract investors. The word investment means that investors will contribute their money to the company and expect a return. These investors automatically become shareholders in the company. As implied, investors are not loan providers.

If the intention is to provide loans, one will see only the company's ability to pay interest on loans and return the loan principal within a certain period. The party lending the money does not care about various creative ideas or processes in a company. It is interested in knowing that the company can repay the principal loan plus the agreed‐on interest rate. In a default situation, the borrower will submit a request to bankrupt the company. The lender will have the right to take existing assets to replace the loan provided.

Given this, we can relate creative capabilities to what happens in the company's balance sheet depending on how one party appreciates creativity and whether creativity is indeed a primary consideration.

Lender Perspective

Lenders or debtholders will be concerned only about the company's revenue because, from that amount, the company will pay the principal and interest of the loan. Sometimes, companies sell some of their shares to generate cash, which can also be used to pay off their debts.

Evergrande―the biggest China property company―expanded its business aggressively and borrowed more than US $300 billion from international lenders. When the pandemic hit, their real estate business slowed down. This situation affected the company's capability to pay back what they owed. In December 2021, Fitch―an agency that rates the financial risk of companies―declared Evergrande in default. Evergrande went beyond the due date to pay their debts of US$1.2 billion to the international lenders and had to sell some of its assets to pay its debts.1

Investor Perspective

On the one hand, if a party is willing to invest their money in a company, then that party fully believes in the proposal of the creative ideas submitted by the company, although the company may first have to suffer losses in the first few years. The party who invests the capital is referred to as an investor and they own a portion of the company's shares. In the balance sheet, we will see an increase in equity. Investors will monitor the productivity of their invested capital by looking at the calculation of return on equity and return on assets.

Investors will also monitor the company's market value movement, be it below or above the book value. Suppose the market value increases rapidly. This indicates that the company's various intangible assets or nonfinancial assets―including creativity, which is actually very valuable but is often hidden and not recorded as assets in the balance sheet―are genuinely appreciated by the market. Furthermore, investors may wait for the right time to sell their shares at a higher price (see Figure 8.1).

The Essence of Creativity

After we understand the importance of creativity for a company and relate it to the balance sheet, we need to further identify the essence of a creative process. The starting point has to do with the various dynamic conditions triggered by multiple change drivers. These consist of four elements from the macro environment: science/technology, political/legal, economy/business, and social/cultural. They include one element of the microenvironment: industry/market. The industry/market also functions as a bridge to the other two elements of the microenvironment, namely, competitors and customers.

FIGURE 8.1 Lender and investor perspectives

The company must constantly observe these five change drivers and the two elements they influence. To generate creative ideas, there are two essential parts. We'll look at each one.

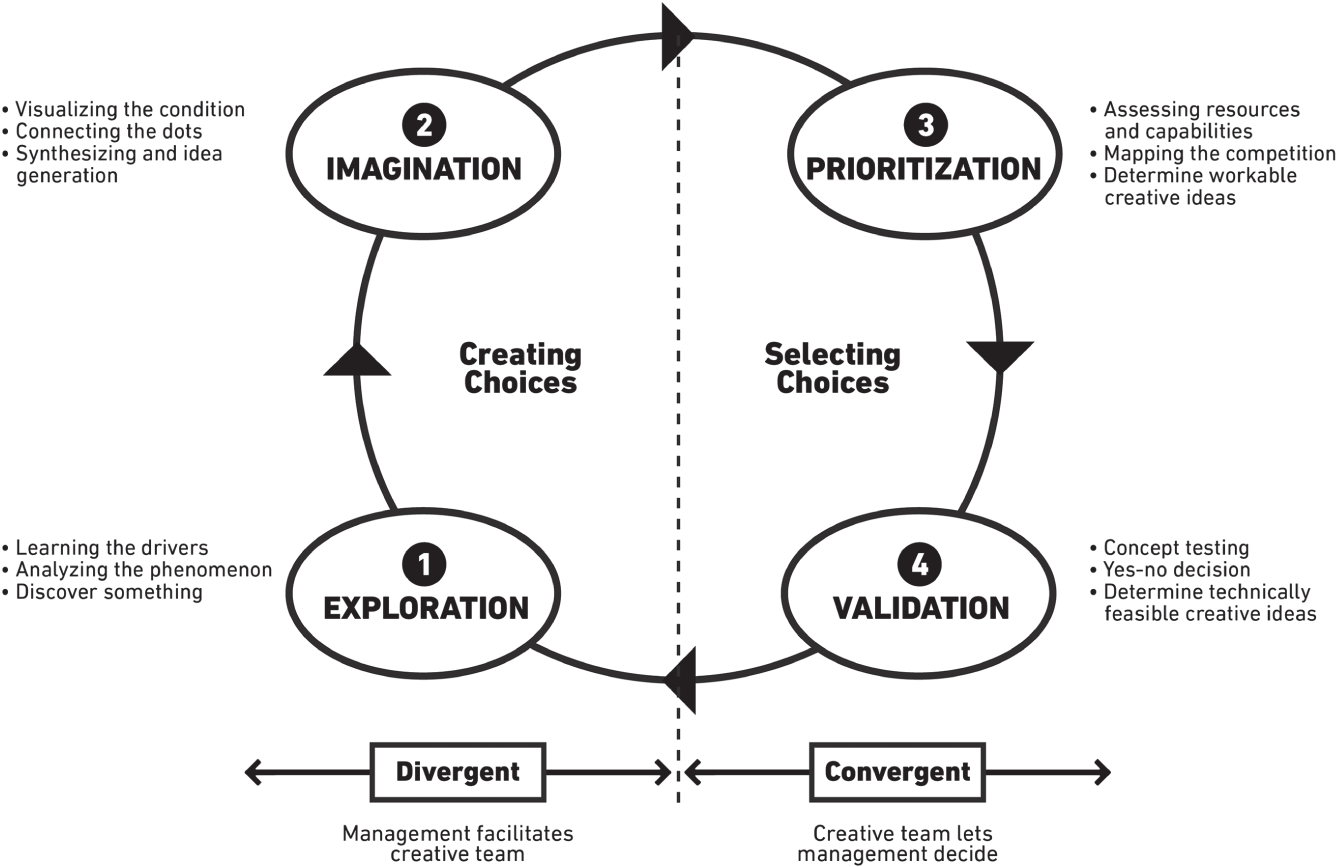

Creating Choices

It starts with an exploration of the five change drivers and then an analysis. This results in a discovery. In the next stage, we employ our imagination to visualize hypothetical conditions, connect the dots to look for multiple possibilities, and synthesize to produce ideas for further consideration.

In creating choices, the company will become a home that facilitates the efforts of people who use their human abilities to explore and imagine. This imagination process will trigger the emergence of many creative ideas that can function as the basis for developing solutions. We must follow a divergent approach to provide optimal flexibility for exploration and imagination.

Selecting Choices

We then prioritize through an assessment process from the available options. A company will want to determine if it has the resources and capabilities to realize these creative ideas. The company also conducts mapping to know the extent of its competitive advantages relative to some significant players or other close competitors.

After prioritization, the next stage is validation through concept testing, followed by the company's decision to either carry out or cancel the options. The company will need to decide which creative ideas are technically feasible. The testing will present insight regarding which ones can be implemented. Hence, we must follow the convergence approach (see Figure 8.2).

After generating technically feasible creative ideas, the cycle of this creative process will turn once more to the initial stage. These ready‐to‐adapt ideas typically will positively affect the company's balance sheet. Funding for them could come from the company itself, lenders, or investors, as explained previously.

FIGURE 8.2 Divergent and convergent approach in the creative process

Measuring the Productivity of Creativity

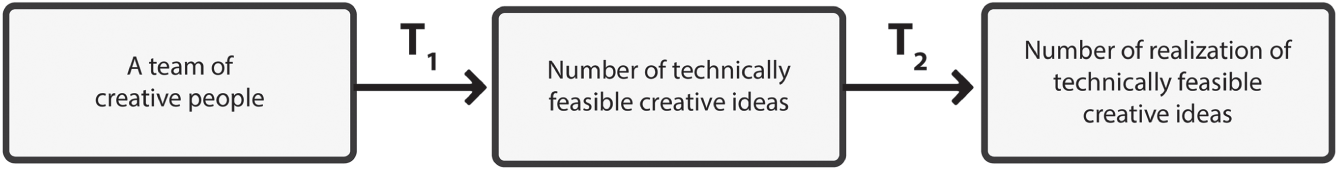

Though measuring creativity in terms of productivity is not easy, we can agree first on one point. Productivity combines effectiveness and efficiency that we borrow from a financial approach. Conceptually, the creative team, as an asset of a company, should produce technically feasible creative ideas within a specific deadline (T1). From these technically feasible creative ideas, the company must decide which ideas―in part or whole―they will develop into actual products within a specific time limit (T2) (see Figure 8.3).

FIGURE 8.3 People, creative ideas, and realization of creative ideas

Effectiveness of Creativity

Hypothetically, we can calculate the effectiveness of creativity (CEffectiveness) by dividing the total number of technically feasible creative ideas (I) by the number of people involved in the creative team (P). This gives us the total number of technically feasible ideas per headcount. We can write the formula as:

By replacing the number of people with the amount of the budget (B) devoted to financing the creative process, we can determine the total number of technically feasible ideas per one unit of money spent. This formula is:

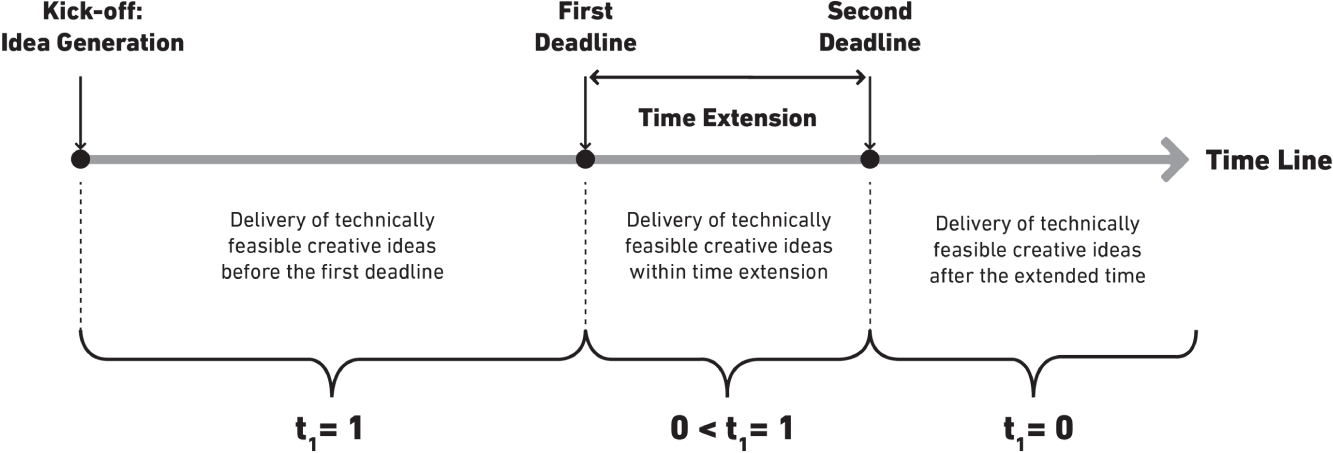

After encountering a problem from potential customers that needs to be solved, a company might set a deadline for several technically feasible creative ideas. If the creative team misses the deadline, then the company might lose its momentum to market timing, and the novelty of those creative ideas begins degrading. After the deadline passes, the company might provide some extra time in certain conditions. It now solely depends on whether the creative team can come up with any, or several, creative ideas before this spare time runs out. Thus, we can add a coefficient (t1) whose magnitude is between 0 and 1 to the earlier effectiveness of the creativity formula with the conditions shown in Table 8.1.

TABLE 8.1 The Value of Coefficient t1

| Coefficient | Conditions |

|---|---|

| t1 = 1 | The creative team can deliver a specified number of technically feasible creative ideas sooner or according to the stipulated deadline. |

| 0 < t1 < 1 | The creative team can deliver a specified number of technically feasible creative ideas within the stipulated time extension. The closer the delivery to the deadline, the lower the value of t1. |

| t1 = 0 | The creative team cannot deliver a specified number of technically feasible creative ideas within the stipulated time extension. Or the creative team can deliver those technically feasible creative ideas―all of them, partly, or even none at all―after the stipulated time extension. |

Figure 8.4 can illustrate those conditions as follows:

FIGURE 8.4 The value of coefficient t1 in a timeline

The two formulas to calculate the effectiveness of creativity can be modified as follows:

or

Efficiency of Creativity

We can hypothetically calculate the efficiency of creativity (CEfficiency) by dividing the total number of realized creative ideas in the form of concrete products that can prove to be solutions for customers and are ready for commercialization (R) by the total number of technically feasible creative ideas (I). The formula is:

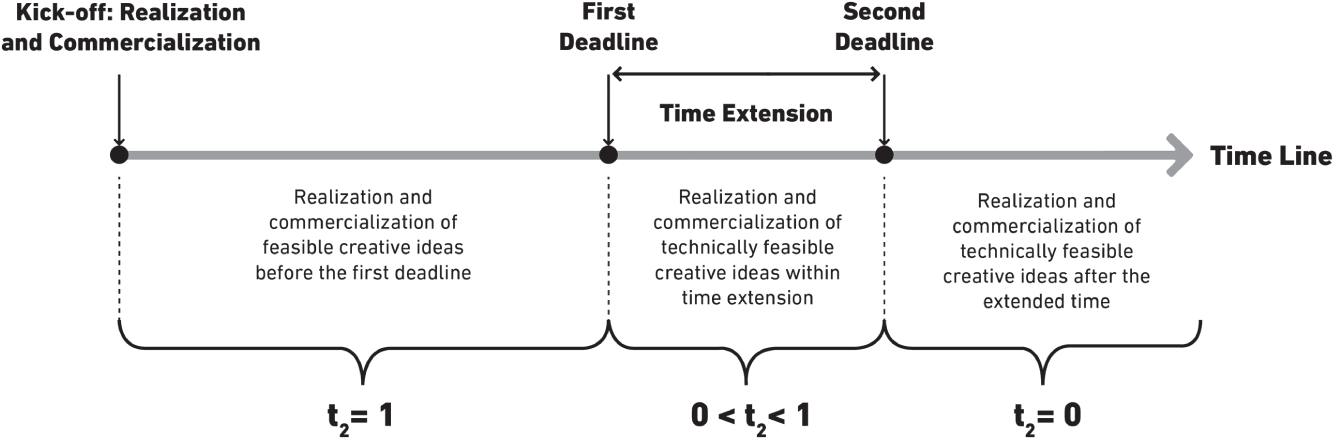

Similar to the calculation for effectiveness, when calculating this efficiency, the company sets a deadline for realizing the various technically feasible creative ideas. If the creative team exceeds the given deadline and the extended deadline, then the realization and commercialization efforts will be too late and will be futile to continue. Therefore, we can add a coefficient (t2) whose magnitude is between 0 and 1 in the efficiency formula with the conditions shown in Table 8.2.

TABLE 8.2 The Value of Coefficient t2

| Coefficient | Conditions |

|---|---|

| t2 = 1 | The company can realize the specified number of technically feasible creative ideas and is ready for commercialization sooner or according to the stipulated deadline. |

| 0 < t2 < 1 | The company can realize the specified number of technically feasible creative ideas and is ready for commercialization within the stipulated time extension. The closer the readiness for commercialization to the deadline, the lower the value of t2. |

| t2 = 0 | The company cannot realize specified numbers of technically feasible creative ideas and is ready for commercialization within the stipulated time extension. Or the company can realize those technically feasible creative ideas―all of them, partly, or even none at all―and is ready for commercialization after the stipulated time extension. |

Figure 8.5 can illustrate those conditions as follows:

FIGURE 8.5 The value of coefficient t2 in a timeline

Thus, the two formulas to calculate the efficiency of creativity can be modified as follows:

Productivity of Creativity

By combining the two formulas, namely, effectiveness and efficiency of creativity, we can hypothetically measure the productivity of creativity (CProductivity). This can be done non financially based on people as assets (that is, the productivity of creativity per headcount) or financially based on the budget amount allocated to the people (that is, the productivity of creativity per unit money spent). The formula then is:

or

Of course, the formula for measuring the productivity of creativity is loaded with simplification. It ignores many other factors (e.g., originality of creative ideas, level of difficulty to imitate, pressure on creative teams) and various changes (e.g., sudden changes in the business environment) that may take place during the creative process. All of these can affect the formulation. However, we can use those formulas for indicative purposes.

Creativity for Productive Capital

In this context, capital is referring to the value of assets used by companies to support creativity, which produces commodities available for sale and generates earnings. Therefore, companies need to understand how much capital they should allocate to support creativity for optimal results. For simplicity, we will link the capital allocated to support creativity to the number of technically feasible creative ideas generated. Each increase in the allocation to support creativity will increase the number of technically feasible creative ideas at different rates. At one point, there will be a decrease in technically feasible creative ideas. There are four conditions for seeing the relationship between capital employed or invested in the support of creativity with technically feasible creative ideas. Let's look at each one.

Underinvestment Range

If there is an additional investment, there will be an increase in the number of technically feasible creative ideas with an increasing rate pattern. This condition shows that the capacity of the creative team is still not fully used, and the investment to support them is still very low to moderate. Therefore, companies need to allocate additional capital to support creativity, and the number of technically feasible creative ideas will increase. The creative team's motivation is usually very high in this range, yet the pressure is still low.

The short‐video social network Snapchat was invented by Evan Spiegel, Reggie Brown, and Bobby Murphy, Stanford University students, in 2011. It began when Spiegel presented an app to share funny moments with friends for 24 hours during product design class. The moments would then be deleted. During Snapchat's development, the team's motivation was still high to achieve its mission to communicate with the full range of human emotion―not just what appears to be aesthetic or perfect.2 At that time, they were all students in college, not thinking too commercially, so there was no investment in developing Snapchat, even though Snapchat's potential was very promising.

Near‐Optimum Investment Range

This pertains to circumstances in which every additional investment, up to a certain amount, causes an increase in the number of technically feasible creative ideas, but at a decreasing rate. This condition indicates that the creative team has begun reaching its maximum capacity. The company has two options: first, add more people involved in the creative team and increase its investment to enhance creativity; second, invest more but maintain the same number of people until they reach their capacity limit to deliver new technically feasible creative ideas. The creative team's motivation is still high in this range, and the pressure is between moderate to high.

Capital A Berhad is the new holding of the AirAsia Group that was announced on January 28, 2022, in Kuala Lumpur. This holding reflects the new core business strategy from the airlines industry toward the synergistic travel and lifestyle business. During the COVID‐19 pandemic, the revenue of AirAsia dropped significantly, and it was immensely challenging to bring back the revenue they had before the pandemic. Therefore, Capital A added more people to diversify business with a financial product, BigPay, education technology, and the grocery business. This transformation got positive feedback from South Korean conglomerate SK Group, which funded US$100 million to develop BigPay in Asia. CEO of Capital A, Tony Fernandes, said that it's not just a new logo but a significant milestone that marks a new era since the group has gone beyond being an airline.3 Here we see that increasing the scope of business (because of pivoting) requires additional investment and additional people so that the installed capacity is in line with high business demands.

Optimum Investment Point

If the company decides not to increase the number of people in its creative team in near‐optimum conditions, the creative team will soon peak its capacity. At this point, the creative team's work pressure has become very high. The work situation grows uncomfortable and less conducive for creativity. The company then reaches the optimum point regarding the investment allocated to support creativity. The company can create a second curve of creativity for productive capital, one of which is to increase the capacity of the creative team by increasing the number of people. At this point, the creative team experiences very high pressure, and their motivations become very vulnerable.

Working in Silicon Valley might at first seem like a dream job for some tech workers. Companies in that space often offer free lunches and competitive salaries to attract top talent. However, top‐performing workers are often under loads of pressure to make innovative products and grow the company's revenue.

Being at a “dream company” does not guarantee high working motivation and loyalty to the company. That is why many Americans quit their jobs during the Great Resignation, which coincided partly with the pandemic. Some were looking for new perks, like working remotely, flexible working hours, and more time for more meaningful tasks.4 We can see that not everyone is suitable for working where the job is very demanding—even if the pay is high.

Overinvestment Range

We will see a decrease in technically feasible creative ideas within this range on every additional amount of capital. The company must immediately stop investing and think about the steps necessary to ensure a rise in the curve (see Figure 8.6). If the company decides not to increase the number of people in its creative team at the optimum point but continues to expand its investment and demands that the creative team still produce more technically feasible creative ideas, the results will be counterproductive. Excessive workload makes the pressure on the creative team exceptionally high, and in turn, will make them demotivated. Consequently, we can see a decrease in technically feasible creative ideas.

FIGURE 8.6 Ranges of investments in creativity

Quincy Apparel is a company that designs, manufactures, and sells working apparel that offers the fit and feel of a high‐end brand at a lower price for young professional women. To increase market penetration, they pitched to some investors. However, it turned out to be the other way around because investors only worsened Quincy's conditions. The founders were disappointed with their guidance from those venture capitalists, who pressured them to grow at full tilt―like the technology start‐ups the investors were more familiar with. Doing so forced Quincy to build inventory and burn through cash before it had resolved its production problems. This made the pressure on the founder extremely high.5

We can see a need for an excellent managerial capability to allocate capital, especially those given for activities related to creativity. Management must also know when to increase, slow down, and stop their investment. In addition, the management team will need to convince investors that the creative capability in the company is indeed valuable. They want to show that it will be able to create strong differentiation and is indeed feasible to be realized commercially at a later stage.

In addition, an increase in investment is directly proportional to the rise in the workload of the creative team, which will increase their work pressure. Therefore, management will want to maintain the motivation of creative team members in order to ensure that they can continue to perform at their best. Strategies to avoid brain fatigue and demotivation, which lead to decreased productivity, are key.

Not all companies are suited for implementing the crunch culture, and not all creative teams can be productive in the work culture that is often the case in some highly competitive industries. Work pressure that is too high to meet tight deadlines can make a person demotivated and unable to be creative optimally. Therefore, the role of talent management becomes very decisive. Equally creative people can show different performances in the same work environment because each person or talent has unique characteristics or psychographic profiles. Hence, the compatibility between talent and the workplace becomes increasingly essential for competitiveness.

In the omnihouse model, there are alternating arrows between creativity and productivity, which means that we must always balance these two aspects. Small‐ and medium‐sized companies that are very strong in terms of creativity need to start considering the importance of calculating the productivity of various capitals used, especially those related to supporting creativity. However, already established companies that sometimes feel trapped in complex calculations related to productivity must re‐present and strengthen their weakened creative abilities.

Understanding the essence of converging creativity and productivity will enable us maximize results—not only output—and also provide us with better judgment in reviewing the productivity of our capital employed for boosting the creative capability of our company.

Key Takeaways

- Lenders typically look first and foremost at whether a loan can be repaid and place a lower value on creativity.

- Investors chip in their money for various creative ideas that can provide returns and increase market value. There is a time to sell their shares for a gain.

- Creativity can be measured for its effectiveness, efficiency, and productivity levels.

- Companies need to invest the right amount of capital for optimal creativity results.

Notes

- 1 https://www.bbc.com/news/business-58579833; https://www.investopedia.com/terms/v/venturecapital.asp; https://www.investopedia.com/terms/p/privateequity.asp

- 2 https://www.topuniversities.com/student-info/careers-advice/7-most-successful-student-businesses-started-university

- 3 https://newsroom.airasia.com/news/airasia-group-is-now-capital-a

- 4 https://www.wired.com/story/great-resignation-tech-workers-great-reconsideration/

- 5 https://hbr.org/2021/05/why-start-ups-fail