CHAPTER 11

Finding and Seizing Opportunities: From Business Outlook to Marketing Architecture

Piyush Gupta, CEO of the Singapore‐based DBS Bank, saw significant growth opportunities in Asia by leveraging digital technology. He noticed the younger generation is more digitally savvy. Also, Asian consumers lead the industry in adoption rates of smartphones.

DBS Bank, which provides a full range of financial services in institutional banking, consumer banking, and wealth management, designed a new road map. It invested heavily in technology and undertook radical change to “rewire” the entire organization with digital innovation. It conducted a comprehensive study of emerging technology trends, customer behavior, and technological infrastructure. A team at DBS Bank also visited some of the world's foremost technology companies to acquire valuable insights and learn how to implement best practices in the banking industry.

Based on the findings of the study, DBS Bank's tech infrastructure team changed from 85% outsourcing to 85% insourcing to transform more effectively. It developed a digital business model with five critical capabilities: acquiring, transacting, engaging, ecosystems, and data. With these, it drove business objectives in different segments. In Singapore and Hong Kong, it digitalized rapidly to anticipate challenges. In India and Indonesia, it was the new entrant with Digi Bank, offering an innovative fintech solution.

DBS Bank prepared marketing communication as part of its transformation strategy, with a renewed mission to “Make Banking Joyful” and “Live More, Bank Less.” It integrated a perception of simplicity and effortless banking experience with marketing tactics. This campaign encapsulated many factors. DBS Bank intends to enable its customers to live hassle‐free with invisible banking, embedding banking in their customer journey, and creating a bank that is ever present for its customers.1

DBS Bank strengthened its digital channel by investing in DBS Car Marketplace, the largest direct seller‐to‐buyer car market in Singapore. It also created DBS Property Marketplace, which connects homeowners and buyers. DBS also invested in Carousell, a platform for buying and selling new or secondhand products, and collaborating with Carousell to offer financial products and payment services on Carousell's platforms.2

As a result, investment analysts from Seedly Singapore found that shares of DBS Bank rose about 23%, versus the Straits Times Index (STI), which declined by about 2% in 2020. (STI is an index that measures the 30 largest and most liquid companies listed in Singapore.)3 DBS Bank received awards such as the Most Innovative in Digital Banking (2021) and Best Bank in the World (2020).4

From the DBS Bank case, we learn that consistently understanding a good business environment, determining strategic options, and preparing implementable marketing strategies and tactics up to their execution can affect the competitiveness of the company. We are able to objectively and subjectively measure competitiveness based on multiple financial and nonfinancial indicators.

In previous chapters, we observed the vertical and diagonal interrelationships in the omnihouse model. We will now look at them horizontally. We will discuss the entrepreneurial marketing strategy, which will consist of three parts: the preparation of the strategy itself, the omni capabilities needed to carry out the strategy, and the company's financial management to increase its market value over time.

To do this, we will consider the two roofs in the omnihouse model. These essentially explain that dynamics in a business environment are an essential foundation for the development of a marketing architecture. We can build competitiveness by developing a marketing architecture that will consist of nine core marketing elements (9E) with positioning‐differentiation‐brand (PDB triangle) as the anchor for those nine marketing elements (see Figure 11.1).

FIGURE 11.1 The dynamics and competitiveness elements in the omnihouse model

From Outlook to Choices

The “dynamics” component consists of five drivers (5D) and―as explained in Chapter 3―includes technology, political/legal, economic, social/cultural, and markets where they are influenced by each other. We refer to these five drivers collectively as change. Together with three other elements—namely, competitor, customer, and company—they are all part of the 4Cs (see Figure 11.2).

FIGURE 11.2 External and internal sections of the 4C model

In analyzing the 5D elements, we have to see which ones are more likely to occur and possess a high level of importance (or relevance). This also includes looking at the immediacy of impact of the five drivers. We need to know whether they are immediate or incremental and how directly these forces can affect our company.

Change, competitor, and customer are external elements required to further see the threats and opportunities. However, we must see the strengths and weaknesses in the company internally.

Technology

We must see various factors of change originating from the rapid growth of technology, digital advances, and online presence. As mentioned, technological advances are one of the strongest drivers and quickly affect the recent changes in the business environment. Here are ten up‐and‐coming technologies that are on pace to be mainstream by 2030:

- Advanced robotics

- Sensors and the Internet of Things (IoT)

- 3D printing

- Plant‐based and lab‐grown dairy products

- Self‐driving cars

- Web 3.0 (world wide web that's based on blockchain technology)

- Extended reality (virtual reality, augmented reality, mixed reality, and the metaverse)

- Supercomputer

- Advanced drone technology

- Green/environmental technology

Political/Legal

The UN invited all heads of state, along with government and high representatives, to New York in 2015 to support the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), a design blueprint for achieving a better and more sustainable future for all generations. In the future, the political or legal aspects will support SDGs by creating and complying with the sustainable guidelines. For example, banks have started giving out loans based on environmental‐social‐governance (ESG) ratings. Governments give incentives for companies that use renewable or green energy.5

Economy

The rise of the sharing economy (e.g., content creator, driver ridesharing, and online shop seller), opportunities for remote jobs, and a freelance marketplace has led some professionals to leave behind a 9‐to‐5 environment. Instead, they are opting for the flexibility offered through the gig economy. The UK government defines the gig economy “as an exchange of activity and money between individuals or companies via a digital channel which actively facilitates matching between vendors and customers, on a short‐term and payment‐by‐task basis.”6

A gig economy switches the traditional economy of full‐time workers, who often focus on their career development, into contract‐based workers. In 2017, an estimated 55 million Americans in the workforce were part of the gig economy, or 36% of the workforce.7 By 2030, American gig workers are forecasted to make up 50% of the entire workforce.8

Recently, we have noticed the rise of a circular economy that applies three principles: eliminating waste and pollution, circulating products and materials (at their best value), and regenerating nature. This approach will no doubt positively affect business, people, and the environment. It would also solve global challenges related to biodiversity, waste, climate change, and pollution.9

The circular economy will encourage companies to transform their business models as part of their social responsibility to create a better future.10 According to Accenture, this circular economy is expected to generate an additional US$4.5 trillion in economic output by 2030. The International Labor Organization also projects that 18 million new jobs will be created that year.11

Social/Cultural

Activity on social media platforms such as Instagram and TikTok continues to gain traction among users. Virtual reality with the metaverse is the next step in the evolution of social networks and will change how individuals interact. These trends open possibilities for a new culture that has not yet been explored.12

Another social and cultural change lies in plant‐based food. The University of Oxford and London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine reported that surveys from more than 15,000 individuals were analyzed using consumption data from the National Diet and Nutrition Survey 2008–2019. The research found that the proportion of people who reported eating and drinking plant‐based alternatives such as plant‐based milk (e.g., oat, soy, or coconut), vegan sausages, and vegetable burgers almost doubled from 6.7% in 2008–2011 to 13.1% in 2017–2019.13

Market

Amid the fourth industrial revolution, market mechanisms are influenced by technology, global connectivity, and ambitious global goals―such as the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. Some industries are disrupted already and have started designing digital transformation road maps by embracing technology and supporting the SDGs to be adaptive.14 For example:

- The automotive industry has developed autonomous electric vehicles to achieve SDG number seven: affordable and clean energy.

- The hospital industry builds telemedicine to achieve SDG number three: good health, well‐being, and reaching more people.

- The retail and fashion industry started developing renewable or sustainable materials using recycled content to achieve SDG number twelve: responsible consumption and production.15

Changes in the five drivers, which we collectively call change, can cause the value proposition we offer to suddenly become obsolete. Therefore, we often refer to change as a value migrator of our products. It can even devaluate the company.

Competitor

On average, companies spend 7–12% of revenue on marketing. Some players spend more, including those in the electronic industry such as Samsung, Sony, and Apple. Others budget less, such as Xiaomi Corporation, a Chinese electronic company founded in April 2010. Xiaomi reduced costs by selling through its online channel in the beginning.16 Its cost leadership model can create affordable products with high‐quality specs that make customers love their product. In 2022, Xiaomi was in the top three of global smartphone leaders, beating Sony, LG, and Nokia.17

In addition, we have to understand the sources of advantages competitors have, including their resources and capabilities in leveraging those resources. We need to pay attention to the extent to which they have dynamic capabilities, which are the basis for building strong corporate agility. The more unique the resources and capabilities are, the more likely our competitors will form distinctive competencies.

Xiaomi uses unusual marketing in the electronic industry. It creates unique resources called Mi Fans, a huge fan base that engages millions of people worldwide in social media. They invite some fans to watch the new launch of any new product. This strategy gives Xiaomi the dynamic capability to increase sales by relying on advocacy from Mi Fans and keep R&D costs down by getting feedback from customers about bugs and unique ideas.18

The number of players in an industry will also determine the level of competition. This will also be determined by the extent to which our competitors can formulate and effectively execute creative strategies. Competitors provide multiple values in response to changes to meet what customers want. Therefore, we may refer to our competitors as value suppliers. If the proposition they offer is valued higher than what we offer in the market, then our customers will likely shift to one of our competitors.

After Xiaomi was quite successful in the smartphone market, some competitors such as Oppo, Vivo, and Realme joined the competition with a similar value proposition and affordable products with high‐quality specifications. Oppo and Vivo use advertising and a brand ambassador strategy19 with campaigns aggressively about “Best Mobile Photography” to grab Xiaomi's market share. In the end, Xiaomi didn't compete with that campaign but focused on building the MiOT Ecosystem to differentiate from competitors.

Customer

We must continuously pay attention to what is happening with our customers, whether these are new or have been with our company for years. We need to monitor if they switch or defect to other competitors. We also have to measure the level of satisfaction and loyalty from our existing customers.

Generation Z (iGen, or a centennial) is associated with those born between 1997 and 2012. These individuals have been raised with an internet network, social media, and smartphones. They tend to be more financially pragmatic and risk‐averse. Like Gen Y, Gen Z cares about social causes, corporate responsibility, and being environmentally friendly. Moreover, Gen Z has different values from other generations. They have YOLO, FOMO, and JOMO:20

- You only live once (YOLO). The present is the only time for them to live life to the fullest. Gen Z will invest and pursue what they love, such as learning a new language, or backpacking across Europe or Africa. For this generation, we might hear, “Life is short; let's buy the bag!”

- Fear of missing out (FOMO). The fear or regret of not being part of an activity or something that others are experiencing. Gen Z will buy what their friends or circle have, take a picture at some famous places to be part of society, or exit their current job to pursue their dream.

- Joy of missing out (JOMO). They have already experienced FOMO and YOLO. Now they have realized that the answer is JOMO. They do not get involved in certain activities, especially those related to social media or entertainment. They also do not like to compare or compete, and they believe that the source of happiness is from their lives and work.

We must understand how this generation views us. Do they appreciate our value propositions? Do they feel engaged and excited with our various communication efforts? What questions do they often ask, and do they indicate a doubt?

We have to understand the new customer paths in this digital era. In the beginning, customers perhaps will watch advertising on TV or social media ads (“aware” stage). Good advertising will draw the customer's attention to click or explore more information from a website (“appeal” stage). Furthermore, customers can ask friends about their experience or reach out to sales representatives (“ask” stage). If a high value is perceived from the product, they can come to the store and shop or check‐out from e‐commerce (“act” stage). Finally, customers can evaluate their product quality and share their experience through social media or their circle (“advocate” stage).21

Companies must deal with customers looking for better service, personalization, speed, and a streamlined buying process wherever and whenever they want. Among consumers, 71% make purchases online and search their devices to find the best prices, and 77% of digital consumers expect a personalized experience in their digital purchases. Therefore, a company cannot rely on a product‐centric approach anymore; rather, it should become a customer‐centric organization.22

Company

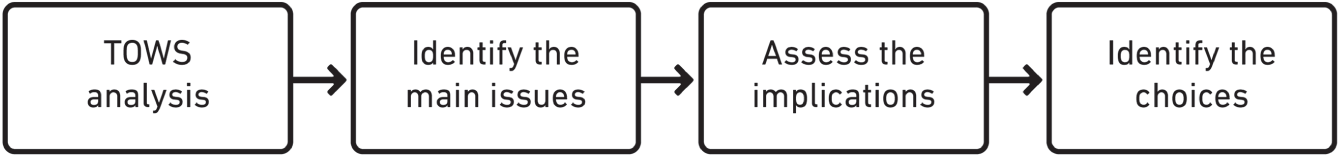

Every company has internal challenges and advantages. These are often analyzed with the external factors to make a strategic choice. External and internal analysis is what we usually know as TOWS analysis.23 (Though it is commonly called a SWOT analysis—strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats—we refer to it here as TOWS to emphasize that the spirit is more outward‐looking or external‐oriented, than inward‐looking or internal‐oriented.)

Regarding this, we must further investigate three factors in our company:

- Existing competencies. What competencies do we have now, and what resources and capabilities can shape these competencies? We have to see if these competencies will remain relevant in the long term. We also have to determine whether these competencies are indeed distinctive. Distinctive competence is defined as a set of unique characteristics that organizations have that enables them to break into desired markets and gain an advantage over winning the competition. A company can develop its distinctive competence in several ways:24

- – Produce a high‐quality product with specific expertise

- – Hire skilled specialists

- – Discover untapped market niches

- – Be innovative or achieve a competitive advantage through sheer management power

- – Excel at technology, research and development, or have a faster product life cycle

- – Have low‐cost production or good customer service

- Stretch possibilities. Is the extent to which we can use competence further than what we have managed to do so far? We must explore various options to leverage the competencies that we already have so as to multiply value‐creation efforts that are not limited to achieving economies of scale but can also increase economies of scope.

FIGURE 11.3 From TOWS analysis to choices

- Risk attitude. What is our perspective in the decision‐making process? We may overestimate the various risks that exist and eventually become risk avoiders. Or we may take risks, provided we have calculated these risks. This strategy is called being a risk‐taker and differs from a risk seeker, who takes risks, even if they are minor, with no calculation.

After we do the 4C analysis, we must identify what the key issues are and will be. These are determined based on the helicopter view of the TOWS analysis that we have done (see Figure 11.3). We should not be forced to solve each of the problems seen in the TOWS analysis one by one. After we have identified the key issues, we must analyze the extent of the implications for our company. Based on the various implications we discover, we determine our choice to go forward or not.

We can have several strategic choices or intent: the option to invest various resources and efforts to be more competitive, no‐go or hold back, harvest, or divest and withdraw or get out of the competition.25 The choice depends on the available resources and our capability to convert those resources into competency to form a competitive advantage. We can further analyze our resources and capabilities using the VRIO analysis approach (VRIO stands for valuable, rare, inimitable, and organization‐wide supported).26 The fewer the resources that meet the VRIO criteria, the weaker the competitive advantage we can form. If we can fulfill some of the VRIO criteria, then we can create a temporary competitive advantage. We will likely build a sustainable competitive advantage if we can satisfy the VRIO criteria completely.27

For example, IKEA offers modular furniture at affordable prices that enables faster assembly, easier maintenance, and improved product longevity over competitors. Customers can replace or add parts through this concept rather than purchase a whole new piece of furniture. If we analyze IKEA using the VRIO framework (see Figure 11.4), we see that this modular design helps IKEA build its competitiveness.28

| Valuable | IKEA provides affordable furniture material enhanced with modular design technology. |

| Rare | While the competitor creates the whole piece of furniture, IKEA creates a modular design for customers to replace and add furniture parts. |

| Inimitable | Competitors can also create modular designs, but the parts will not match IKEA products. Competitors cannot imitate because IKEA has a design law/legal patent. Therefore the customer must purchase replacement or additional parts only from IKEA, which functions as a customer lock‐in mechanism. |

| Organization | Many experienced product designers support IKEA. |

FIGURE 11.4 Simple VRIO analysis of IKEA

Based on this analysis, we see that IKEA has a great opportunity to sustain its competitive advantage. It strongly fulfills the four VRIO criteria. IKEA can be confident with its vision and mission going forward.

However, if we decide to invest, and there is a gap between what we want to achieve and our choice, then we must try to cover the gap. We might do this by collaborating with other parties in a business ecosystem. If necessary, we can even do coopetition with our direct competitors.

Translating Choice into Marketing Architecture

Once the choice to invest has been made, the marketing architecture needs to be set, which we will describe next. We will then look at each of its components: strategies, tactics, and values (see Figure 11.5).

Marketing Strategy

In the mainstream marketing approach, marketing strategy consists of segmentation, targeting, and positioning (STP). We call it strategy because―in the process of segmentation and targeting in particular―after we have succeeded in mapping out a market into several segments, the next step is to decide which segments we will serve and which ones we will not serve.

FIGURE 11.5 From outlook to marketing architecture

In developing this concept of marketing, there have been several shifts. One approach is called new wave marketing. It is related to segmentation, targeting, and positioning as shown here.29

- From Segmentation to Communitization

We can no longer do segmentation by referring to a static approach, namely, seeing customers as individuals when there is the undeniable fact that customers are social creatures. We are familiar with segmentation using geographic, demographic, psychographic, and behavioral variables, but now we have to strengthen it by including the customer's purpose, values, and identity (PVI) in the segmentation process.

We cannot see the relationship between the company and the customer only vertically, where we put the customer as the passive target segment. We should also consider a more horizontal approach in which the customer is an active community member. In addition, we must further strengthen customer mapping based on similarities by assessing the community's potential on cohesiveness and influence.

- From Targeting to Confirmation

Targeting initially considers how the company devotes its resources to several segments. It considers the size of the segment, its growth rate, competitive advantage, and competitive situation. On top of that, we need further confirmation by looking at three additional criteria: relevance, level of activity, and the total number of community networks (NCNs).

Relevance will refer to the extent of the PVI similarities between a community and our brand. In addition, we must pay attention to how actively community members engage with one another. Rather than a list of names, we have to look at the level of participation from community members in various activities. We must also pay attention to NCNs, namely, the extent to which the community network reaches. This is not limited to its community network but includes parties outside the community across other networks.

- From Positioning to Clarification

In line with the rise of customer bargaining power, the effectiveness of the one‐sided positioning approach determined by the company is decreasing. Usually, we will develop a positioning statement containing several main elements: the target market, brand, frame of reference, point of differentiation, and reasons to believe. The positioning statement is generally the basis for developing the tagline. However, this kind of emphasis on the positioning is now insufficient. We need a new approach that will clarify for customers to avoid overpromised but, in fact, under‐delivered phenomenon.

We are shifting from company‐oriented content to customer‐oriented content. Positioning, which used to be an attempt to convey a single message, has now involved multidimensional messages. In addition, we must communicate with more than a one‐way approach; we must use multiple‐way communications.

This marketing strategy is the basis for implementing customer management where we must pay attention to four points related to customers:30

- Get. Actively seek out potential customers and make them become our customers.

- Keep. Build customer loyalty with customer loyalty programs or by creating a solid lock‐in mechanism.

- Grow. Add value through cross‐sell and upsell so that we are not only pursuing economies of scale but also economies of scope.

- Win back. Recapture relevant and significant contributing customers who switched to our competitors.

Marketing Tactic

In the classical marketing concept, tactics consist of three elements: differentiation, marketing mix, and selling. These three elements translate the STP elements into a concrete form. We need to define differentiation in line with positioning, and then translate that differentiation into a marketing mix consisting of product, price, place, and promotion. After that, we must convert what we offer to the market into sales, which are part of our company's selling efforts.

Similar to the STP elements, these three tactical elements have also shifted with today's era of increasingly complex and complicated customers.

- From Differentiation to Codification

The differentiation that has been created so far through content differentiation (what to offer), context differentiation (how to offer), and other enablers (such as aspects of technology, facility, and people) is no longer sufficient. It is limited to only the marketers' point of view. This approach is purely a matter of the marketing department's job. It does not often refer to the organizational culture, which can be the DNA of a brand.

Therefore, the marketing team must be able to codify the company's DNA to be used as brand DNA. This brand DNA―which refers to symbols and styles, system and leadership, and shared values and substance―must be understood, internalized, and thoughtfully applied by all employees.

- From Marketing Mix to New Wave Marketing Mix

The traditional marketing mix elements also experienced a shift: from product to co‐creation, from price to currency, from place to communal activation, and from promotion to the conversation.

A company is often trapped in a company‐centric approach during the new product development stage. From the initial ideation to the realization of a product, the company's role dominates. Customers tend to be passive and can give their opinion only on a product. Now companies must provide opportunities and involve customers in the development of a product. Customers can become co‐creators.

The place element―part of a distribution or marketing channel―is usually a physical platform where people can get products and their supporting services. With the alternative of online distribution, the physical platform becomes unattractive if it only functions for the acquisition of goods or services. Therefore, we must transform this element into a real‐world platform for communities to meet and share ideas or experiences. Physical space is essential for strengthening the relationship of a community. The success of this communal activation depends on how a company can effectively combine online and offline approaches.

- From Selling to Commercialization

The traditional selling approach is still needed, but commercialization must now support it by optimizing social networks to get new customers and retain existing ones. The combination of offline and online approaches provides many conveniences for salespeople to build a strong network. The increasing number of customers who use social media makes them more willing to listen to the opinions of others as part of their decision‐making process. Commercialization is how we can use these social networks effectively and efficiently to support their sales process.

Marketing Value

The last group of marketing values includes brand, service, and process. A brand is the value indicator that requires service as a value enhancer and process as a value enabler.

In the marketing value section, there are also some shifts to be recognized.

- From Brand to Character

As an identity, we need the brand to form a relationship with its customers. It must provide a functional and emotional benefit. However, there is increasing difficulty in creating customer trust in brands as a company requires us to adopt an approach that emphasizes brand‐as‐person identity.31

- From Service to Care

Despite the rapid development of technology, we can see a paradox. Customers are becoming more human. That is why human‐to‐human interactions are still more critical than machine‐to‐human interactions that are technology‐based and tend to be mechanistic. In line with that, we cannot serve customers based on a reactive mechanistic approach but must be proactive and humanistic to show that we care. The era of customer service has long ended and been replaced by customer care.

- From Process to Collaboration

The process is an essential part of value creation in a company, from procurement of raw materials to delivering a product to the customers. Companies must manage various processes in the value chain to ensure that everything runs effectively and efficiently. To do this, three indicators are often used as benchmarks: quality, cost, and delivery.

This marketing value section emphasizes the increasing importance of the brand‐as‐human approach. Therefore, companies must have highly functioning brand management capabilities.

The Positioning‐Differentiation‐Brand Triangle

Three main elements integrate the nine core elements of marketing, namely positioning, differentiation, and the brand. This is called the PDB triangle (see Figure 11.6). Positioning is a promise related to the value that a brand will deliver to its customers and is the core of marketing strategy. Differentiation is an effort by a company to understand aspects of products and services relevant to keeping customers satisfied and loyal. Differentiation is the core of marketing tactics. The brand is the core of marketing value.

As an identity, the brand must have a clear positioning. Positioning, a promise to customers, must be realized through strong differentiation to form brand integrity. If we can consistently maintain this differentiation, it will create a strong brand image.

Circling back to the beginning case about DBS Bank in Asia, we can learn that Gupta, the CEO, analyzes macroeconomics to spot opportunities using digital technology and the potential from focusing on the younger generation. He defines three segments, and each has a different marketing objective. Developing countries (such as Indonesia and India) attract potential users with DigiBank. The rest of the segment reduces cost by implementing technology in its operation. Singapore and Hong Kong's market focus is to self‐disrupt and become defensive from the moves of their competitors.

FIGURE 11.6 The PDB triangle

DBS Bank builds its clear positioning based on simplicity and an effortless banking experience. Technology as the core of differentiation supports the positioning and provides the integrity of the brand promise. DBS Bank builds a positive brand image through marketing communication and making sure to fulfill the brand promise. All three elements of DBS Bank's PDB triangle need to be consistent and support one another.

Based on our discussion, we can observe that the preparation of strategy must be consistent and cover all aspects to take advantage of the existing opportunities and create a competitive advantage. Once we understand the landscape, we can choose if we want to move forward into a marketing architecture that consists of strategy, tactics, and value. Finally, the PDB triangle is an anchor for the nine core marketing elements. We must ensure that each element in the PDB triangle can support and be consistent with one another, so that the brand has a strong identity, integrity, and image.

Key Takeaways

- Analyzing the 5D elements (technology, political/legal, economic, social/cultural, and markets) enables us to see which are most likely to occur and are relevant.

- Looking at change, competitors, customers, and the company itself enables us to see strengths and weaknesses, along with threats and opportunities.

- Marketing strategy is moving from segmentation to communitization, from targeting to confirmation, and from positioning to clarification.

- Changes in the marketing tactic include from differentiation to codification, from marketing mix to new wave marketing‐mix, and from selling to commercialization.

- In marketing value, there are several shifts to recognize: from brand to character, from service to care, and from process to collaboration.

Notes

- 1 https://www.finextra.com/pressarticle/73937/dbs-to-roll-out-live-more-bank-less-rebrand-as-digital-transformation-takes-hold

- 2 https://www.dbs.com/newsroom/DBS_invests_in_mobile_and_online_classifieds_marketplace:Carousell

- 3 https://blog.seedly.sg/dbs-ocbc-uob-valuations/

- 4 https://www.dbs.com/about-us/who-we-are/awards-accolades/2020.page

- 5 https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda

- 6 World Economic Forum, “What Is the Gig Economy and What's the Deal for Gig Workers?” (May 26, 2022). https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/05/what-gig-economy-workers/

- 7 https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/381850

- 8 https://www.northbaybusinessjournal.com/article/opinion/outlook-for-the-gig-economy-freelancers-could-grow-to-50-by-2030/

- 9 https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/topics/circular-economy-introduction/overview

- 10 https://www.dnv.com/power-renewables/publications/podcasts/pc-the-rise-of-the-circular-economy.html

- 11 https://wasteadvantagemag.com/the-rise-of-the-circular-economy-and-what-it-means-for-your-home/#:~:text=The%20Rise%20Of%20The%20Circular%20Economy%20and%20What%20It%20Means%20For%20Your%20Home,‐July%2024%2C%202019&text=According%20to%20research%20by%20Accenture,new%20jobs%20by%20then%20too

- 12 https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesagencycouncil/2021/12/21/what-is-the-metaverse-and-how-will-it-change-the-online-experience/?sh=21a761f52f32

- 13 https://www.newfoodmagazine.com/news/158831/plant-based-consumption-uk/

- 14 https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/09/technology-global-goals-sustainable-development-sdgs/

- 15 https://www.fastcompany.com/1672435/nike-accelerates-10-materials-of-the-future

- 16 https://www.themarcomavenue.com/blog/how-xiaomi-is-dominating-the-global-smartphone-market/

- 17 https://gs.statcounter.com/vendor-market-share/mobile

- 18 https://www.themarcomavenue.com/blog/how-xiaomi-is-dominating-the-global-smartphone-market/

- 19 https://www.quora.com/Why-are-Oppo-and-Vivo-spending-so-much-on-advertising

- 20 https://www.livemint.com/news/business-of-life/yolo-fomo-jomo-why-gens-y-and-z-quit-1567429692504.html

- 21 Philip Kotler, Hermawan Kartajaya, and Iwan Setiawan, Marketing 4.0: Moving from Traditional to Digital (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2017).

- 22 https://egade.tec.mx/en/egade-ideas/research/experience-demanding-customer

- 23 Here we use the abbreviation TOWS instead of SWOT just to show that the spirit is more outward‐looking (external‐oriented) instead of inward‐looking (internal‐oriented).

- 24 https://www.referenceforbusiness.com/encyclopedia/Dev-Eco/Distinctive-Competence.html

- 25 The term strategic intent was first coined out by Gary Hamel and C. K. Prahalad in the late 1980s.

- 26 This VRIO framework was developed by Jay Barney in 1991.

- 27 Refer to Jay B. Barney; https://thinkinsights.net/strategy/vrio-framework/

- 28 https://www.designnews.com/design-hardware-software/what-can-design-engineers-learn-ikea

- 29 Several shifts in marketing concepts (so‐called new wave marketing) are discussed in Philip Kotler, Hermawan Kartajaya, and Den Huan Hooi, Marketing for Competitiveness: Asia to the World! (Singapore: World Scientific, 2017).

- 30 The get, keep, and grow activities (excluding win back) refer to Steve Blank and Bob Dorf, The Start‐Up Manual: The Step‐by‐Step Guide for Building a Great Company (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2020), Figure 3.10 and Table 3.3.

- 31 David A. Aaker, Building Strong Brands (New York, NY: Free Press, 1995).