10.2 Experiment 1: Visual Orientation in a Beetle

Scarabaeus zambesianus, an African dung beetle, flies off at sunset to forage for fresh dung. Once it finds some, it quickly forms a ball of dung with its front legs and head and rolls it away in a straight line – the most efficient path for escaping aggressive competitors for food in the dung pile. Apart from its peculiar eating habits, it also has an interesting ability to orient itself using the pattern of polarized light that forms in the sky at sunset. As shown in Figure 10.2, a dung beetle pushes the balls backwards with its hind legs. Despite being unable to see in the direction that it is moving, it maintains its departure bearing over a long distance. The beetle does this by using specialized photoreceptors in its compound eyes that sense the direction of polarization in the sky.

Figure 10.2 Dung beetle pushing a ball away from the dung pile using its hind legs. © Marie Dacke.

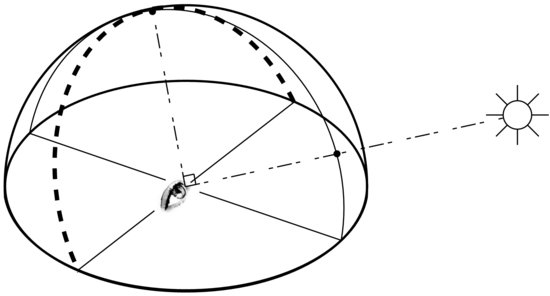

The reason that the sky has a polarization pattern is that sunlight is scattered off molecules in the air. This process is known as Rayleigh scattering and is also the reason why the daytime sky is not pitch black but has a soft blue glow. For the reasons explained in Box 10.1, the degree of polarization varies across the sky in relation to the direction of the sun. A band of highly polarized light stretches across the zenith at sunset, with the degree of polarization decreasing gradually in the directions towards and away from the setting sun. The location of the band is shown schematically in Figure 10.3, where the dashed semicircle represents the dominant direction of polarization. Though invisible to us, this pattern gives the dung beetle a very palpable sense of direction.

- Light can be seen as an electromagnetic wave. The polarization describes how the electric field is oriented in the wave.

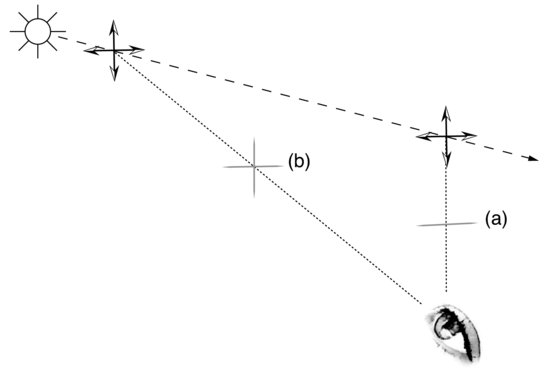

- The dashed line in Figure 10.4 represents a sunray. It has one horizontal and one vertical polarization component, as indicated by the crossed arrows on the line. Since there is no dominant direction of polarization, this light is defined as unpolarized.

- The polarization is always perpendicular to the direction in which the wave propagates. It cannot be parallel to this direction.

- For this reason, light scattered at right angles from the sunray (a) only contains one polarization component. The vertical polarization component cannot be scattered in the vertical direction. Since (a) has a dominant direction of polarization, this light is defined as polarized.

- Light scattered along the direction of the sunray (b) contains both polarization components. Both components are scattered because none of them is parallel to the direction of the wave. This light is therefore unpolarized, just as the sunlight.

By monitoring the beetles’ movements under the nighttime sky Marie Dacke and coworkers found that, on moonlit nights, the beetles rolled their balls radially in straight lines from the dung, but on nights without a moon they entered on a more or less random walk about the pile. This made them wonder if the beetles were able to use also the polarization of scattered moonlight for orientation. This light being about a million times fainter than that from the sunlit sky, it was by no means obvious that it could be used for orientation. To confirm that the beetles used the polarization and not the moon itself, they hid the moon from view and put a polarizing filter over a dung-rolling beetle. Such a filter transmits one polarization component of the skylight and blocks the other. When the filter's direction of polarization was perpendicular to that of the sky's polarization, the beetles turned close to 90 degrees when entering under the filter. If the filter was oriented in parallel with the sky's polarization, the beetles maintained their bearing under the filter [1]. This was the first demonstration of an animal using the polarization pattern in the moonlit sky as a nocturnal compass. This ability is obviously advantageous as it allows the beetle to extend its foraging time well after sunset. The method is useful also under partly cloudy conditions when the moon itself may be hidden behind a cloud.

This was clearly an important finding, so it was with mixed emotions that Dacke discovered on a later occasion that, suddenly, the beetles could orient themselves also on nights without a moon. How was this possible? She started toying with various hypotheses. It was already clear that the beetles could use several cues for orientation, such as the sun, the moon, and polarization patterns in the sky. If one cue were missing, it would use another. In the laboratory she had shown that the beetles could orient to light bulbs. If one bulb was switched off and another switched on, the beetle would change direction. Leaving the bulb on the beetle would proceed in a curved path around the bulb, probably in an attempt to keep the light source centered in a region of its compound eye. As the moon and sun are infinitely far away this method would result in a straight path in the field.

Was it possible that they used the stars for orientation? Larger animals had been shown to do so, but since a small compound eye can only collect a comparably small amount of light, most stars would not be visible to the beetle. On the other hand, seeing only a few of the brightest stars would be sufficient for orientation. The Milky Way was another possibility. It had been low in the sky during her first experiment but was almost at the zenith now. But to test whether the beetles used bright stars or the Milky Way for orientation she would have to switch parts of the night sky on and off, which of course would be impossible. Or would it? At this point, Dacke decided to call the planetarium in Johannesburg with a singularly odd request.

She wanted to bring her beetles – and fresh dung – into the planetarium to see how they reacted to different cues in the night sky that, in a planetarium, could be projected onto the domed screen at will. This would make it possible to investigate how the beetles reacted to various subsets of the brightest stars or to the Milky Way. Rather unexpectedly, the management of the planetarium agreed that this was an excellent way to use their facility.

The research team would also set up a specially designed, two-meter wide wooden arena in the dome. They did not want to monitor the beetles using a camera, as the legs of the camera stand could work as landmarks for orientation. The arena was designed so that nothing but the planetarium dome would be visible to the beetles, which were placed at its center through a trap door from underneath. A number of collection troughs were mounted around the perimeter of the arena for receiving the ball when it was pushed over the edge. The straightness of the path was measured by monitoring the time between placing a beetle at the center and the audible bump of the ball falling into the trough. Previous results had shown that a random walk could take more than five minutes while a straight path to the edge would only take about 20 seconds.

The planetarium experiment resulted in another unique discovery. It showed that S. zambesianus could, in fact, orient to the Milky Way, adding another method of orientation to its already impressive repertoire. This was the first convincing demonstration of using of the Milky Way for orientation in the animal kingdom, as well as the first evidence of star orientation in any insect [2].