3.3 Divine Mathematics

When later philosophers describe the early Greek attempts at a scientific explanation of the world, they distinguish between two schools of thought. On the one hand there is the Ionian school that we have discussed. They sometimes call it atheistic, as it relied only on material causes. The other school is a religious one, arising in greater Greece in the west. In Plato's account, the Ionian school does not recognize any form of intentional creation in Nature. It claims that only the human mind creates intentionally and it, too, arises from material causes. The religious school, by contrast, claims that purpose and thought precede the properties of matter. Nature is ruled by reason [2].

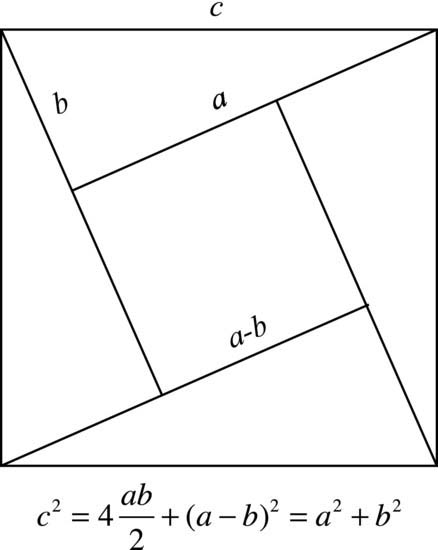

This religious tradition begins with Pythagoras, who is known to most school children through his famous theorem. Figure 3.1 gives a simple geometric proof of it. He was originally from the island Samos, just a stone's throw off the coast from Miletus, but he moved to Croton in southern Italy where he founded a religious community. They practiced asceticism and taught that it was, for some reason, sinful to eat beans. They also spent time contemplating mathematics, where they saw the key to understanding the world.

Figure 3.1 A simple, geometric proof of Pythagoras’ theorem. Calculating the area of the large square by adding the areas of the four right-angled triangles and the small square, it directly follows that c2 = a2 + b2. It is not known if Pythagoras himself could prove the theorem.

Scientifically, the Pythagoreans were highly successful in number theory and it is really the mathematicians that are their true inheritors today. But the Pythagorean idea that the world can be understood using mathematics has had a profound influence on the development of natural science – a fact that can be verified by anyone who has looked in a physics textbook. Still, their variety of science constituted a break with the Ionian tradition. It based itself more on abstract ideas than on information provided by the senses. Philosophy had been practical but with the Pythagoreans it became a detached contemplation of the world [2].

The Pythagorean cosmology seems odd to modern eyes. For them, mathematics was more than a means to describe the world. They literally believed that the world consisted of numbers. Their points had size and could be added to lines. Lines had width and could be added to surfaces, and so forth. To them, number theory was physics. But mathematics also had a moral quality. For example, since the celestial bodies were thought to be divine the Pythagoreans declared that they had to be perfect spheres, moving in perfect circles. Nothing else would be suitable in the heavens. This thought would have a tremendous impact on later thinkers and obstruct real advances in astronomy for two millennia [1].

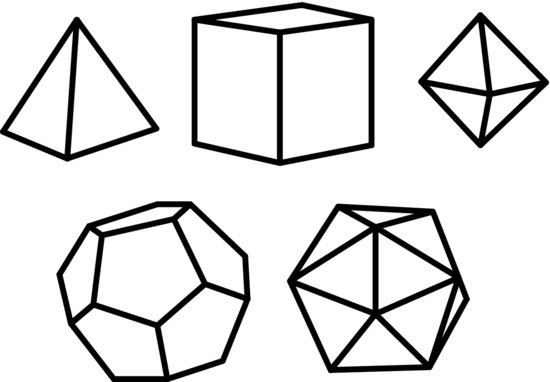

The Pythagoreans discovered the simple numerical relationships that are known as musical intervals. When the string of an instrument was shortened to half its length its sound was raised by an octave. Other fractions of the length produced other intervals. The fact that they could describe the sounds of a string mathematically is probably the origin of their belief that there is a mathematical structure in the universe [2]. They were also fascinated by regular solids, which are bodies where all sides consist of identical regular polygons. There are only five such solids and they are shown in Figure 3.2. For some reason, the Pythagoreans thought that knowledge about one of them, the dodecahedron, was too dangerous to be revealed to people outside their community. The four other regular bodies were connected with the four elements that were believed to make up this world. They thought that the fifth must be connected with a fifth element, existing only in the heavens [3].

Figure 3.2 The five Pythagorean solids.

A crisis occurred within the order when it became clear that the diagonal of a square could not be expressed as a ratio of two numbers. According to the Pythagorean worldview a line consisted of a finite number of points and the finding showed that this idea was incorrect. It is especially ironic that the discovery was made using the Pythagorean theorem [3]. Their immediate reaction was to forbid spreading the discovery. The story goes that one of the disciples was drowned at sea for divulging the secret [2].

The mathematical worldview would also give rise to the theory of ideas. This theory would have a great influence on Plato, who will be introduced below. When talking about a triangle, for instance, they did not mean a triangle drawn on paper. Such triangles are always imperfect due to practical reasons. Lines can never be drawn quite straight with pen and paper, and so on. For this reason, the laws of geometry only fully apply to a perfect triangle, or the idea of a triangle, which exists only in the mind. In other words, they thought that the world of ideas contained pure, perfect things, whereas the real world could only produce second-rate representations of them. This line of thinking would later develop into the notion that only the mind could access the perfect, real, and eternal. The sensible was apparent, defective, and transient [2].

Parts of the Pythagorean heritage were to inspire the development of modern science and still have relevance today. The Pythagorean's were the first to use the word cosmos for the world, which means order. The development of physics owes much to their idea of a mathematical structure in the cosmos. But in other ways their departure from the Ionian tradition was to obstruct the sprouting seeds of science. Observation and experience became subordinate to abstract thinking. They based their science on gentlemanly speculation and were reluctant to experiment. From one perspective, turning your attention away from the material world probably seemed right in a society where the abhorrence for physical labor increased at the same rate as the slavery. But, when trying to understand the world, it is not a fruitful approach to ignore the facts and work solely with preconceived ideas. Furthermore, keeping inconvenient truths secret from the rest of the scientific community does not promote the growth of knowledge.

The religious tradition of the Pythagoreans was continued by two of the most famous philosophers of all time, Plato and his student Aristotle. Their ideas, in turn, have had a tremendous impact on western thinking. One important reason for this is that a large portion of their works has survived. We only know the work of earlier philosophers by fragments of manuscripts and references by other authors, but in Plato's case we have the complete works [4]. Another important reason may be that Aristotle was the private teacher of Alexander the Great, who was to spread Greek culture widely over the world. Although they are important as philosophers, they are often considered to be less interesting as scientists. This is especially true of Plato, who maintained that contemplation of the abstract is a safer way to knowledge than actual observation. He believed that the physical world was riddled with imperfections, whereas the world of ideas was perfect.

Some parts of Aristotle's work were influenced by this view but in other parts he clearly recognized the value of observation. He made great progress in biology, mainly by describing and categorizing information obtained by observational studies. His physics, on the other hand, was not rooted in observations of the real world. In summary he thought that different substances strive toward different layers in the universe to find their “natural places”. Earth falls because earth should somehow be at the center of the universe and fire rises because its natural place is outside the other elements. He also taught that force is needed for motion and that the velocity of a falling object is directly proportional to its weight. In Koestler's words, he organized the Platonic theory of ideas into a two-storey universe, where the earth and the region below the moon were seen as corrupt and defective, plagued with eternal change, and the heavens were of another substance, immutable from creation to eternity. Any change visible in the heavens could thereby only be apparent. The astronomer's job was to describe, on paper, the apparent motions of the planets and not to offer real explanations. The job was to “save the appearances”, for what was there to explain when nothing changed? Ptolemy elaborated the Aristotelian cosmology by adding deferents and epicycles to the heavens to force the planets to move in circular, uniform, “perfect” orbits. This cosmology would maintain its stranglehold on the progress of astronomy through the middle ages and, scientifically, this period would be less than spectacular [4]. Therefore, we will now quickly leap nearly two millennia forward.