CHAPTER 7

Information Governance for Business Units

When looking at the Information Governance Reference Model (previously presented), note that there are five key areas of impact: business units, legal, records and information management (RIM), information technology (IT), and privacy and security. In this section of the book we cover how each of these major areas is impacted by, and participates in, an IG program.

Business units generate profit, and this is where IG programs can have their greatest impact. Rather than focusing on “soft cost” justifications such as productivity increases or process improvements, hard-dollar savings and revenue generation can be achieved through successful IG programs targeted in business units.

Supporting functions, including legal, RIM, IT, and privacy and security must work in a cross-functional, collaborative way to reduce information risks and costs, leverage information as an asset, and support business units to increase profitability.

Start with Business Objective Alignment

IG program planning begins with developing business objectives for the program itself. Those business objectives must be aligned with and support the accomplishment of overall organizational business objectives. This alignment is key to winning executive support and funding for an IG program. If executives can see a clearly aligned path and that the IG program is synchronized with other organizational initiatives, then they are more likely to back the IG program.

If, for instance, one corporate objective is:

- Grow the company by making acquisitions and folding them into existing operations and systems.

Then we know that existing operations and systems must be standardized so that the acquired companies can be more easily incorporated into operations. To do this, we can form some objectives for the IG program, such as:

- Improve and standardize document and records search and retrieval functions.

- Develop or update access rights policies.

- Train all employees and new employees on new search and access capabilities and restrictions.

Some key metrics that may be used to measure progress may be:

- Implement a standardized functional taxonomy for classifying documents and records within 180 days.

- Implement standardized metadata schema for organizing documents and records within 180 days.

- Implement auto-categorization analytics software by year end.

- Train employees and newly acquired business units on search tools to improve productivity and access restrictions to improve security by year-end.

These IG program objectives and metrics all align to support the higher-level corporate objectives, and should win executive support, as well as support from key stakeholder groups.

If, for instance, other corporate objectives are:

- Reduce information risk and the likelihood and impact of breaches.

- Preserve and protect brand equity.

Then we know that cybersecurity measures must be implemented and employee training must take place. To do this, we can form some objectives for the IG program, such as:

- Reduce information risk by implementing new security measures.

- Reduce information risk by training employees on new and emerging cybersecurity threats.

Some key metrics that may be used to measure progress may be:

- Conduct an assessment of IT security practices using the CIS Top 20 (more detail is in Chapter 11) within 90 days.

- Implement new cybersecurity recommendations within 180 days.

- Train 100 percent of home office knowledge workers with new security awareness training (SAT) program by year-end.

In both of the above examples, the IG program objectives flow up to support the accomplishment of organizational business objectives, and time-delimited metrics are in place to measure progress.

Which Business Units Are the Best Candidates to Pilot an IG Program?

When evaluating possible starting places for an IG program, look for business units that:

- Have a high litigation profile. Since IG programs reduce e-discovery collection and review costs by better organizing information, and reducing the information footprint by disposing of information that has met its lifecycle requirements, business units that have a high level of litigation can show significant benefits by implementing IG programs.

- Have excessive compliance risks and costs. When employees have difficulty producing documentation in a timely manner for regulators, or cannot find the documentation, and the organization is fined or sanctioned excessively, those business units are good candidates for IG program pilots. IG programs can have a significant impact by improving search and retrieval functions as a result of standardizing taxonomy and metadata approaches.

- Have opportunities to monetize or leverage information value. By applying infonomics principles and formulas, information can be measured and monetized to add new value to the organization.

What Is Infonomics?

Following is an excerpt from Doug Laney's groundbreaking book Infonomics (Bibliomotion/Taylor & Francis, 2018). Used with permission.

Infonomics is the theory, study, and discipline of asserting economic significance to information. It provides the framework for businesses to monetize, manage, and measure information as an actual asset. Infonomics endeavors to apply both economic and asset management principles and practices to the valuation, handling, and deployment of information assets.

As a business, information, or information technology (IT) leader, chances are that you regularly talk about information as one of your most valuable assets. Do you value or manage our organization's information like an actual asset? Consider your company's well-honed supply chain and asset management practices for physical assets or your financial management and reporting discipline. Do you have similar accounting and asset management practices in place for your “information assets”? Most organizations do not.

When considering how to put information to work for your organization, it's essential to go beyond thinking and talking about information as an asset to actually valuing and treating it as one. The discipline of infonomics provides organizations with a foundation and methods for quantifying information asset value and formal information asset management practices.

Infonomics posits that information should be considered a new asset class in that it has measurable economic value and other properties that qualify it to be accounted for and administered as any other recognized type of asset—and that there are significant strategic, operational, and financial reasons for doing so. Infonomics provides the framework businesses and governments need to value information, manage it, and wield it as a real asset.

How to Begin an IG Program

Your organization needs a starting point, one that is measured and defined so that you can measure and track your progress from that point. So, typically an IG assessment must take place. That assessment will provide information as to where problems lie, and smoke out some issues that might not be readily apparent. An IG assessment will measure, in objective terms, the level of maturity of existing IG efforts, and lay out a roadmap with metrics or key performance indicators (KPIs) for IG improvement.

Several assessment methodologies are available. Perhaps the most comprehensive one is the IG Process Maturity Model (IGPMM) from the Compliance, Governance and Oversight Council (CGOC). The IGPMM measures the maturity of 22 specific processes for the five key impact areas depicted in the IG Reference Model: lines of business, legal, RIM, IT, and privacy and security. The IGPMM heavily emphasizes the role of legal functions, and privacy and security, and shows that RIM plays a smaller but important role in the overall implementation of IG programs.

The model was created in 2012, and updated in 2017. Processes were revised and new ones added in line with marketplace and technology developments. New processes include data security, including cloud security considerations; data quality; and privacy and data protection processes that consider the impact of the European Union General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).1

Other assessment tools and methodologies also exist. It is important to note that all assessment tools have some inherent bias, depending on the agenda of the organization that created them. For instance, the Information Governance Maturity Model (IGMM) from ARMA International is based on the Generally Accepted Recordkeeping Principles®, so it is best suited not for holistic IG assessments, but for assessments of the maturity of recordkeeping processes. It is possible to utilize this model to evaluate RIM functions, while also utilizing the IGPMM from CGOC for broader and more relevant IG processes. Other assessment tools have been developed for specific industries such as healthcare (for details on IG programs in this vertical market, refer to Information Governance for Healthcare Professionals (HIMSS/CRC Press, 2018), by Robert F. Smallwood.

Business Considerations for an IG Program

By Barclay T. Blair

The business case for information governance (IG) programs has historically been difficult to justify. It is hard to apply a strict, short-term return on investment (ROI) calculation. A lot of time, effort, and expense is involved before true economic benefits can be realized. Therefore, a commitment to the long view and an understanding of the many areas where an organization will improve as a result of a successful IG program are needed. But the bottom line is that reducing exposure to business risk, improving the quality and security of data and e-documents, cutting out unneeded stored information, and streamlining information technology (IT) development while focusing on business results add up to better organizational health and viability and, ultimately, an improved bottom line.

Let us take a step back and examine the major issues affecting information costing and calculating the real cost of holding information, consider Big Data and e-discovery ramifications, and introduce some new concepts that may help frame information costing issues differently for business managers. Getting a good handle on the true cost of information is essential to governing it properly, shifting resources to higher-value information, and discarding information that has no discernible business value and carries inherent, avoidable risks.

Changing Information Environment

The information environment is changing. Data volumes are growing, but unstructured information (such as e-mail, word processing documents, social media posts) is growing faster than our ability to manage it. Some unstructured information has more structure than others, containing some identifiable metadata (e.g. e-mail messages all have a header, subject line, time/date stamp, and message body). Some call this semistructured information, but for the purposes of this book, we use the term “unstructured information” to include semistructured information as well.

The volume of unstructured information is growing dramatically. Analysts estimate that, from 2017 to 2025, the amount of worldwide data will grow tenfold, to 163ZB (1 zettabyte = 1 trillion gigabytes).2 However, the volume of unstructured information will actually grow approximately 50 percent faster than structured data. Analysts also estimate that fully 90 percent of unstructured information will require formal governance and management by 2020. In other words, the problem of unstructured IG is growing faster than the problem of data volume itself.

What makes unstructured information so challenging? There are several factors, including:

- Horizontal versus vertical. Unstructured information is typically not clearly attached to a department or a business function. Unlike the vertical focus of an enterprise resource planning (ERP) database, for example, an e-mail system serves multiple business functions—from employee communication to filing with regulators—for all parts of the business. Unstructured information is much more horizontal, making it difficult to develop and apply business rules.

- Formality. The tools and applications used to create unstructured information often engender informality and the sharing of opinions that can be problematic in litigation, investigations, and audits—as has been repeatedly demonstrated in front-page stories over the past decade. This problem is not likely to get any easier as social media technologies and mobile devices become more common in the enterprise.

- Management location. Unstructured information does not have a single, obvious home. Although e-mail systems rely on central messaging servers, e-mail is just as likely to be found on a file share, mobile device, or laptop hard drive. This makes the application of management rules more difficult than the application of the same rules in structured systems, where there is a close marriage between the application and the database.

- “Ownership” issues. Employees do not think that they “own” data in an accounts receivable system like they “own” their e-mail or documents stored on their hard drive. Although such information generally has a single owner (i.e., the organization itself), this nonownership mindset can make the imposition of management rules for unstructured information more challenging than for structured data.

- Classification. The business purpose of a database is generally determined prior to its design. Unlike structured information, the business purpose of unstructured information is difficult to infer from the application that created or stores the information. A word processing file stored in a collaboration environment could be a multimillion-dollar contract or a lunch menu. As such, classification of unstructured content is more complex and expensive than structured information.

Taken together, these factors reveal a simple truth: Managing unstructured information is a separate and distinct discipline from managing databases. It requires different methods and tools. Moreover, determining the costs and benefits of owning and managing unstructured information is a unique—but critical—challenge.

The governance of unstructured information creates enormous complexity and risk for business managers to consider while making it difficult for organizations to generate real value from all this information. Despite the looming crisis, most organizations have limited ability to quantify the real cost of owning and managing unstructured information. Determining the total cost of owning unstructured information is an essential precursor to managing and monetizing that information while cutting information costs—key steps in driving profit for the enterprise.

Storing things is cheap … I've tended to take the attitude, “Don't throw electronic things away.”

—Data scientist quoted in Anne Eisenberg, “What 23 Years of E-Mail May Say About You,” New York Times, April 7, 2012

The company spent $900,000 to produce an amount of data that would consume less than one-quarter of the available capacity of an ordinary DVD.

—Nicholas M. Pace and Laura Zakaras, “Where the Money Goes: Understanding Litigant Expenditures for Producing Electronic Discovery,” RAND Institute for Civil Justice, 2012

Calculating Information Costs

We are not very good at figuring out what information costs—truly costs. Many organizations act as if storage is an infinitely renewable resource and the only cost of information. But, somehow, enterprise storage spending rises each year and IT support costs rise, even as the root commodity (disk drives) grows ever cheaper and denser. Obviously, they are not considering labor and overhead costs incurred with managing information, and the additional knowledge worker time wasted sifting through mountains of information to find what they need.

Some of this myopic focus on disk storage cost is simple ignorance. The executive who concludes that a terabyte costs less than a nice meal at a restaurant after browsing storage drives on the shelves of a favorite big-box retailer on the weekend is of little help.

Rising information storage costs cannot be dismissed. Each year the billions that organizations worldwide spend on storage grows, even though the cost of a hard drive is less than 1 percent of what it was about a decade ago. We have treated storage as a resource that has no cost to the organization outside of the initial capital outlay and basic operational costs. This is shortsighted and outdated.

Some of the reason that managers and executives have difficulty comprehending the true cost of information is old-fashioned miscommunication. IT departments do not see (or pay for) the full cost of e-discovery and litigation. Even when IT “partners” with litigators, what IT learn rarely drives strategic IT decisions. Conversely, law departments (and outside firms) rarely own and pay for the IT consequences of their litigation strategies. It is as if when the litigation fire needs to be put out, nobody calculates the cost of gas for the fire trucks.

But calculating the cost of information—especially information that does not sit neatly in the rows and columns of enterprise database “systems of record”—is complex. It is more art than science. And it is more politics than art. There is no Aristotelian Golden Mean for information.

The true cost of mismanaging information is much more profound than simply calculating storage unit costs. It is the cost of opportunity lost—the lost benefit of information that is disorganized, created and then forgotten, cast aside, and left to rot. It is the cost of information that cannot be brought to market. Organizations that realize this, and invest in managing and leveraging their unstructured information, will be the winners of the next decade.

Most organizations own vast pools of information that is effectively “dark”: They do not know what it is, where it is, who is responsible for managing it, or whether it is an asset or a liability. It is not classified, indexed, or managed according to the organization's own policies. It sits in shared drives, mobile devices, abandoned content systems, single-purpose cloud repositories, legacy systems, and outdated archives.

And when the light is finally flicked on for the first time by an intensive hunt for information during e-discovery, this dark information can turn out to be a liability. An e-mail message about “paying off fat people who are a little afraid of some silly lung problem” might seem innocent—until it is placed in front of a jury as evidence that a drug company did not care that its diet drug was allegedly killing people.3

The importance of understanding the total cost of owning unstructured information is growing. We are at the beginning of a “seismic economic shift” in the information landscape, one that promises to not only “reinvent society,” (according to an MIT data scientist) but also to create “the new oil … a new asset class touching all aspects of society.”4

Smart leaders across industries will see using big data for what it is: a management revolution.

—Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson, “Big Data: The Management Revolution,” Harvard Business Review (October 2012)

Big Data Opportunities and Challenges

We are entering the epoch of Big Data—an era of Internet-scale enterprise infrastructure, powerful analytical tools, and massive data sets from which we can potentially wring profound new insights about business, society, and ourselves. It is an epoch that, according to the consulting firm McKinsey, promises to save the European Union public sector billions of euros, increase retailer margins by 60 percent, reduce US national healthcare spending by 8 percent, while creating hundreds of thousands of jobs.5 Sounds great, right?

However, the early days of this epoch are unfolding in almost total ignorance of the true cost of information. In the near nirvana contemplated by some Big Data proponents, all data is good, and more data is better. Yet it would be an exaggeration to say that there is no awareness of potential Big Data downsides. A recent study by the Pew Research Center was positive overall but did note concerns about privacy, social control, misinformation, civil rights abuses, and the possibility of simply being overwhelmed by the deluge of information.6

But the real-world burdens of managing, protecting, searching, classifying, retaining, producing, and migrating unstructured information are foreign to many Big Data cheerleaders. This may be because the Big Data hype cycle7 is not yet in the “trough of disillusionment” where the reality of corporate culture and complex legal requirements sets in. But set in it will, and when it does, the demand for intelligent analysis of costs and benefits will be high.

IG professionals must be ready for these new challenges and opportunities—ready with new models for thinking about unstructured information. Models that calculate the risks of keeping too much of the wrong information as well as the benefits of clean, reliable, and accessible pools of the right information. Models that drive desirable behavior in the enterprise, and position organizations to succeed on the “next frontier for innovation, competition, and productivity.”8

Full Cost Accounting for Information

It is difficult for organizations to make educated decisions about unstructured information without knowing its full cost. Models like total cost of ownership (TCO) and ROI are designed for this purpose and have much in common with full cost accounting (FCA) models. FCA seeks to create a complete picture of costs that includes past, future, direct, and indirect costs rather than direct cash outlays alone.

FCA has been used for many purposes, including the decidedly earthbound task of determining what it costs to take out the garbage and the loftier task of calculating how much the International Space Station really costs. A closely related concept often called triple bottom line has gained traction in the world of environmental accounting, positing that organizations must take into account societal and environmental costs as well as monetary costs.

The US Environmental Protection Agency promotes the use of FCA for municipal waste management, and several states have adopted laws requiring its use. It is fascinating—and no accident—that this accounting model has been widely used to calculate the full cost of managing an unwanted by-product of modern life. The analogy to outdated, duplicate, and unmanaged unstructured information is clear.

Applying the principles of FCA to information can increase cost transparency and drive better management decisions. In municipal garbage systems where citizens do not see a separate bill for taking out the garbage, it is more difficult to get new spending on waste management approved.9 Without visibility into the true cost, how can citizens—or CEOs—make informed decisions?

Responsible, innovative managers and executives should investigate FCA models for calculating the total cost of owning unstructured information. Consider costs such as:

- General and administrative costs, such as cost of IT operations and personnel, facilities, and technical support.

- Productivity gains or losses related to the information.

- Legal and e-discovery costs associated with the information and information systems.

- Indirect costs, such as the accounting, billing, clerical support, contract management, insurance, payroll, purchasing, and so on.

- Up-front costs, such as the acquisition of the system, integration and configuration, and training. This should include the depreciation of capital outlays.

- Future costs, such as maintenance, migration, and decommissioning of information systems. Future outlays should be amortized.

Calculating the Cost of Owning Unstructured Information

Any system designed to calculate the cost or benefit of a business strategy is inherently political. That is, it is an argument designed to convince an audience. Well-known models like TCO and ROI are primarily decision tools designed to help organizations predict the economic consequences of a decision. While there are certainly objective truths about the information environment, human decision making is a complex and imperfect process. There are plenty of excellent guides on how to create a standard TCO or ROI. That is not our purpose here. Rather, we want to inspire creative thinking about how to calculate the cost of owning unstructured information and help organizations minimize the risk—and maximize the value—of unstructured information.

Any economic model for calculating the cost of unstructured information depends on reliable facts. But facts can be hard to come by. A client recently went in search of an accurate number for the annual cost per terabyte of Tier 1 storage in her company. The company's storage environment was completely outsourced, leading her to believe that the number would be transparent and easy to find. However, after days spent poring over the massive contract, she was no closer to the truth. Although there was a line item for storage costs, the true costs were buried in “complexity fees” and other opaque terms.

Organizations need tools that help them establish facts about their unstructured information environment. The business case for better management depends on these facts. Look for tools that can help you:

- Find unstructured information wherever it resides across the enterprise, including e-mail systems, shared network drives, legacy content management systems, and archives.

- Enable fast and intuitive access to basic metrics, such as size, date of last access, and file type.

- Provide sophisticated analysis of the nature of the content itself to drive classification and information life cycle decisions.

- Deliver visibility into the environment through dashboards that are easy to for nonspecialists to configure and use.

Sources of Cost

Unstructured information is ubiquitous. It is typically not the product of a single-purpose business application. It often has no clearly defined owner. It is endlessly duplicated and transmitted across the organization. Determining where and how unstructured information generates cost is difficult.

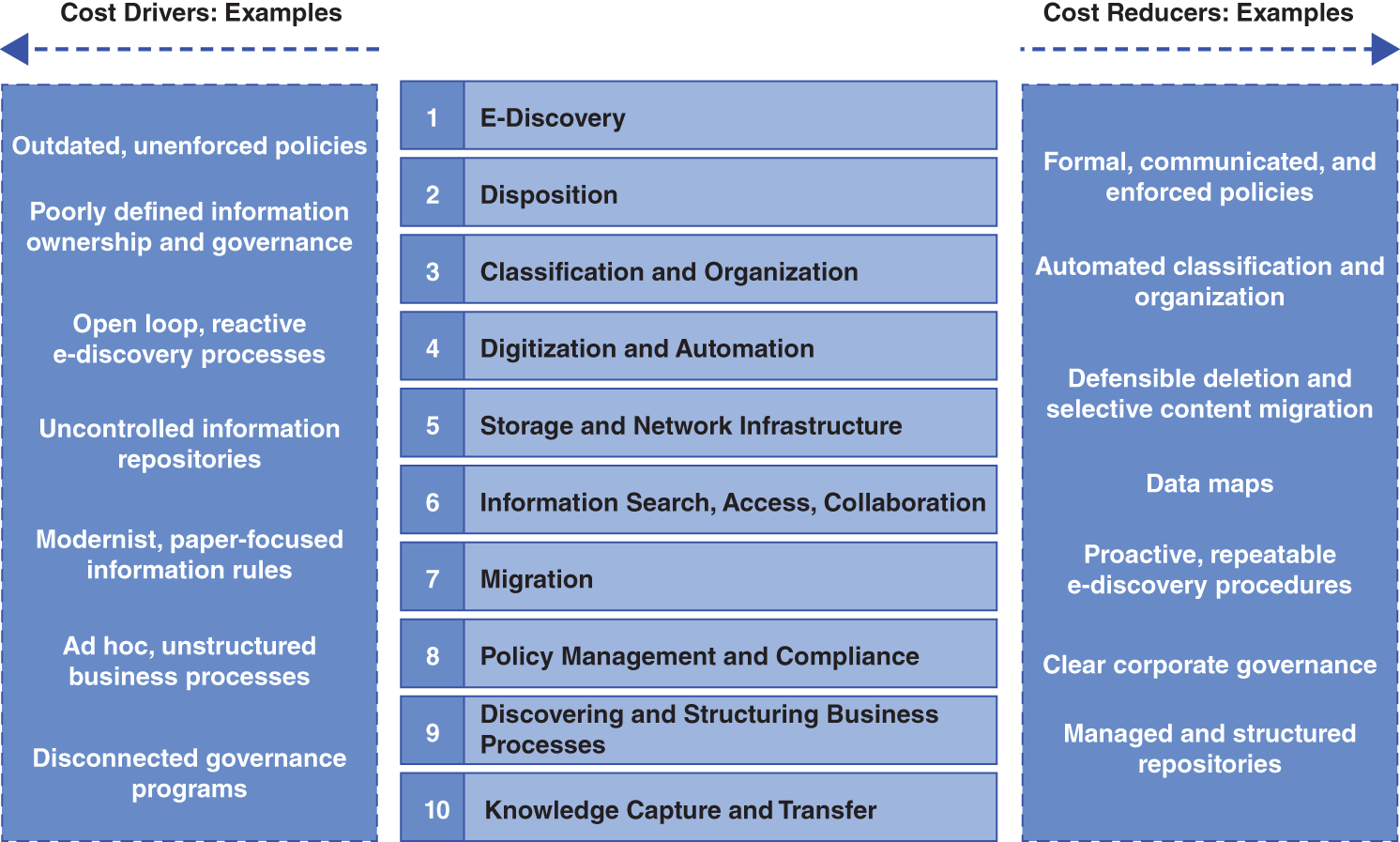

However, doing so is possible. Our research shows that at least 10 key factors drive the total cost of owning unstructured information. These 10 factors identify where organizations typically spend money throughout the life cycle of managing unstructured information. These factors are listed in Figure 7.1, along with examples of elements that typically increase cost (“Cost Drivers,” on the left side) and elements that typically reduce costs (“Cost Reducers,” on the right side).

- E-discovery: Finding, processing, and producing information to support lawsuits, investigations, and audits. Unstructured information is typically the most common target in e-discovery, and a poorly managed information environment can add millions of dollars in cost to large lawsuits. Simply reviewing a gigabyte of information for litigation can cost $14,000.10

Figure 7.1 Key Factors Driving Cost

Source: Barclay T. Blair.

- Disposition: Getting rid of information that no longer has value because it is duplicate, out of date, or has no value to the business. In poorly managed information environments, separating the wheat from the chaff can cost large organizations millions of dollars. For enterprises with frequent litigation, the risk of throwing away the wrong piece of information only increases risk and cost. Better management and smart IG tools drive costs down.

- Classification and organization: Keeping unstructured information organized so that employees can use it. It also is necessary so management rules supporting privacy, privilege, confidentiality, retention, and other requirements can be applied.

- Digitization and automation. Many business processes continue to be a combination of digital, automated steps and paper-based, manual steps. Automating and digitizing these processes requires investment but also can drive significant returns. For example, studies have shown that automating accounts payable “can reduce invoice processing costs by 90 percent.”11

- Storage and network infrastructure: The cost of the devices, networks, software, and labor required to store unstructured information. Although the cost of the baseline commodity (i.e. a gigabyte of storage space) continues to fall, for most organizations overall volume growth and complexity means that storage budgets go up each year. For example, between 2000 and 2010, organizations more than doubled the amount they spent on storage-related software even though the cost of raw hard drive space dropped by almost 100 times.12

- Information search, access, and collaboration: The cost of hardware, software, and services designed to ensure that information is available to those who need it, when they need it. This typically includes enterprise content management systems, enterprise search, case management, and the infrastructure necessary to support employee access and use of these systems.

- Migration: The cost of moving unstructured information from outdated systems to current systems. In poorly managed information environments, the cost of migration can be very high—so high that some organizations maintain legacy systems long after they are no longer supported by the vendor just to avoid (more likely, simply to defer) the migration cost and complexity.

- Policy management and compliance: The cost of developing, implementing, enforcing, and maintaining IG policies on unstructured information. Good policies, consistently enforced, will drive down the total cost of owning unstructured information.

- Discovering and structuring business processes: The cost of identifying, improving, and systematizing or “routinizing” business processes that are currently ad hoc and disorganized. Typical examples include contract management and accounts receivable as well as revenue-related activities, such as sales and customer support. Moving from informal, e-mail, and document-based processes to fixed workflows drives down cost.

- Knowledge capture and transfer: The cost of capturing critical business knowledge held at the department and employee level and putting that information in a form that enables other employees and parts of the organization to benefit from it. Examples include intranets and their more contemporary cousins such as wikis, blogs, and enterprise social media platforms.

The Path to Information Value

At the peak of World War II, 70,000 people went to work every day at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The site was once America's premier shipbuilding facility, building the steam-powered Ohio in 1820 and the aircraft carrier USS Independence in the 1950s. But the site fell apart after it was decommissioned in the 1960s. Today, the “Admiral's Row” of Second Empire–style mansions once occupied by naval officers is an extraordinary sight, with gnarled oak trees pushing through the rotting mansard roofs.13

Seventy percent of managers and executives say data are “extremely important” for creating competitive advantage. “The key, of course, is knowing which data matter, who within a company needs them, and finding ways to get that data into users’ hands.”

—The Economist Intelligence Unit, “Levelling the Playing Field: How Companies Use Data to Create Advantage” (January 2011)

However, after decades of decay, the Navy Yard is being reborn as the home of hundreds of businesses—from major movie studios to artisanal whisky makers—taking advantage of abundant space and a desirable location. There were three phases in the yard's rebirth:

- Clean. Survey the site to determine what had value and what did not. Dispose of toxic waste and rotting buildings, and modernize the infrastructure.

- Build and maintain. Implement a plan to continuously improve, upgrade, and maintain the facility.

- Monetize. Lease the space.

Most organizations face a similar problem. However, our Navy yards are the vast piles of unstructured information that were created with little thought to how and when the pile might go away. They are records management programs built for a different era—like an automobile with a metal dashboard, six ashtrays, and no seat belts. Our Navy yards are information environments no longer fit for purpose in the Big Data era, overwhelmed by volume and complexity.

We are doing a bad job at managing information. McKinsey estimates that in some circumstances, companies are using up to 80% of their infrastructure to store duplicate data.14 Nearly half of respondents in a survey ViaLumina recently conducted said that at least 50% of the information in their organization is duplicate, outdated, or unnecessary.15 We can do better.

Phase 1. Clean

We should put the Navy Yard's blueprint to work, by first identifying our piles of rotting unstructured information. Duplicate information. Information that has not been accessed in years. Information that no longer supports a business process and has little value. Information that we have no legal obligation to keep. The economics of such “defensible deletion” projects can be compelling simply on the basis of recovering the storage space and thus reallocating capital that would have been spent on the annual storage purchase.

Step 2. Build and Maintain

Cleaning up the Navy Yard is only the first step. We cannot repeat the past mistakes. We avoid this by building and maintaining an IG program that establishes our information constitution (why), laws (what), and regulations (how). We need a corporate governance, compliance, and audit plan that gives the program teeth, and a technology infrastructure that makes it real. It must be a defensible program to ensure we comply with the law and manage regulatory risk.

Phase 3. Monetize

IG is a means to an end, and that end is value creation. IG also mitigates risk and drives down cost. But extracting value is the key. Although monetization and value creation often are associated with structured data, new tools and techniques create exciting new opportunities for value creation from unstructured information.

For example, what if an organization could use sophisticated analytics on the e-mail account of their top salesperson (the more years of e-mail the better), look for markers of success, then train and hire salespeople based on that template? What is the pattern of a salesperson's communications with customers and prospects in her territory? What is the substance of the communications? What is the tone? When do successful salespeople communicate? How are the patterns different between successful deals and failed deals? What knowledge and insight resides in the thousands of messages and gigabytes of content? The tools and techniques of Big Data applied to e-mail can bring powerful business insights. However, we have to know what questions to ask. According to Computerworld, “the hardest part of using big data is trying to get business people to sit down and define what they want out of the huge amount of unstructured and semi-structured data that is available to enterprises these days.”16

The analytics challenges of Big Data create opportunities. For example, McKinsey predicts that demand for “deep analytical talent in the United States could be 50 to 60 percent greater than its projected supply by 2018.” A chief reason for this gap is that “this type of talent is difficult to produce, taking years of training in the case of someone with intrinsic mathematical abilities.” However, the more profound opportunity is for the “1.5 million extra additional managers and analysts in the United States who can ask the right questions and consume the results of the analysis of big data effectively.”17

Table 7.1 Key Steps in the IG Process

Source: Barclay T. Blair.

| Phase 1. Clean | Phase 2. Build and Maintain | Phase 3. Monetize |

| Information inventory Defensible deletion Records retention and legal hold |

IG policies and procedures Corporate governance, compliance and audit Technology |

Create value through information, e.g. drive sales and improve customer satisfaction Business insights Increase margins |

Some companies are using analytics to set prices. For example, the largest distributor of heating oil in the United States sets prices on the fly, based on commodity prices and customer retention risks.18 In a case that caught the attention of morning news shows, with breathless headlines like “Are Mac Users Paying More?” an online travel company revealed that “Mac users are 40 percent more likely to book four or five-star hotels … compared to PC users.”19 Despite the headlines, the company was not charging Mac users more. Rather, computer brand was a variable used to determine which products were highlighted.

The path to information value is not necessarily linear. Different parts of your business may achieve maturity at different rates, driven by the unique risks and opportunities of the information they possess.

Challenging the Culture

The best models for calculating the total cost of owning unstructured are those that information professionals can use to challenge and change organizational culture. Much of the unstructured information that represents the greatest cost and risk to organizations is created, communicated, and managed directly by employees—that is, by human beings. As such, better IG relies in part on improving the way those human beings use and manage information.

New Information Models

The information calorie and information cap-and-trade models, explored next, are two new models designed to help with the challenge of governing information.

There's not a person in a business anywhere who gets up in the morning and says, “Gee, I want to race into the office to follow some regulation.” On the other hand, if you say, “There's an upside potential here, you're going to make money,” people do get up early and do drive hard around the possibility of finding themselves winners on this.

—Dan Etsy, environmental policy professor at Yale University, quoted in Richard Conniff, “The Political History of Cap and Trade,” Smithsonian Magazine (August 2009)

Consider a cap-and-trade system for information. Do not limit the creation and storage of useful information—that defeats the purpose of investing in IT in the first place. Rather, design a cap-and-trade system that controls the amount of information pollution and rewards innovation and management discipline.

While there is no objective “right amount” of information for every organization or department, we can certainly do better than “as much as you want, junk or not.” After all, “nearly all sectors in the US economy had at least an average of 200 terabytes of stored data … and many sectors had more than 1 petabyte in mean stored data per company.”20 Moreover, up to 50% of that information is easily identifiable as data pollution.21 So, we have a reasonable starting point.

Here are some tips for creating an information cap-and-trade system:

- Baseline the desired amount of information per system, department, and/or type of user. How much information do you currently have? How much has value? How much should you have? These are not easy questions to answer, but even rough calculations can make a big difference.

- Create information volume targets or quotas, and allocate them by business unit, system, or user. This is the “cap” part of the system.

- Calculate the fully loaded cost of a unit of information, and adopt it as a baseline metric for the “trade” part of the system. Consider whether annual e-discovery costs can be allocated to this unit in a reasonable way.

- Create an internal accounting system for tracking and trading information units, or credits within the organization. Innovative departments will be rewarded, laggards will be motivated.

- Get creative in what the credits can purchase. New revenue-generating software? Headcount?

Future State: What Will the IG-Enabled Organization Look Like?

When an organization is IG enabled, or “IG mature”—meaning IG is “baked in” or infused into operations throughout the enterprise and coordinated on an organization-wide level—it will look significantly different from most organizations today. Not only will the organization routinely execute business processes with inherent privacy and security considerations, but also it will have a solid handle on the total cost of information; not only will it have shifted resources to capitalize on the opportunities of Big Data; not only will it be managing the deluge in a systematic, business-oriented way by cutting out data debris and leveraging information value; it will also look significantly different in key operational areas including legal, privacy and security, and IT.

The organization will have an embedded, robust, and ongoing security awareness training (SAT) program, and will adhere to standards such as ISO 27001 and guidance from the Cloud Security Alliance to keep data secure. It will also deploy and utilize advanced tools such as data loss prevention (DLP) and information rights management (IRM). Concerning privacy matters, the organization will have an ongoing privacy awareness training (PAT) program, and be able to routinely meet the requirements of new regulations, such as GDPR, or the California Consumer Privacy Act.

In legal matters, the mature IG-enabled organization will be better suited to address litigation in a more efficient way through a standardized legal hold notification (LHN) process. Legal risk is reduced through improved IG, which will manage information privacy in accordance with applicable laws and regulations. During litigation, your legal team will be able to sort through information more rapidly and efficiently, improving your legal posture, cutting e-discovery costs, and allowing for attorney time to be focused on strategy and to zero in on key issues. This means attorneys should have the tools to be more effective. Adherence to retention schedules means that records and documents can be discarded at the earliest possible time, which reduces the chances that some information could pose a legal risk, while also reducing the storage footprint. Hard costs can be saved by eliminating the approximately 69% of stored information that no longer has business value. That cost savings may be the primary rationale for the initial IG program effort. By leveraging advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), analytics, and forms of these, such as predictive coding, the organization can reduce the costs of e-discovery and better utilize attorney time.

RIM functions will operate with more efficiency and in compliance with laws and regulations. Appropriate retention periods will be applied and enforced, and authentic, original copies of business records will be readily identifiable, so that managers are using current and accurate information on which to base their decisions. Over the long term, valuable information from projects, product development, marketing programs, and strategic initiatives will be retained in corporate memory, reducing the impact of turnover and providing distilled information and knowledge to contribute to a knowledge management (KM) program. KM programs can facilitate innovation in organizations, as a knowledge base is built, retained, expanded, and leveraged.

In your IT operations, a focus on how IT can contribute to business objectives will bring about a new perspective. Using more of a business lens to view IT projects will help IT to contribute toward the achievement of business objectives. IT will be working more closely with privacy, security, legal, RIM, risk, and other business units, which should help these groups to have their needs and issues better addressed by IT solutions. Having a standardized data governance program in place means cleaning up corrupted or duplicated data and providing users with clean, accurate data as a basis for line-of-business software applications and for decision support in business intelligence (BI) and analytics applications. Better data is the basis for improved insights, which can be gained by leveraging analytics, and will improve management decision-making capabilities and help to provide better customer service, which can impact customer retention. It costs a lot more to gain a new customer than to retain an existing one, and with better data quality, the opportunities to cross-sell and upsell customers will be improved. This can provide a sustainable competitive advantage. Standardizing the use of business terms will facilitate improved communications between IT and other business units, which should lead to improved software applications that address user needs. Adhering to information life cycle management principles will help the organization to apply the proper level of IT resources to its high-value information while decreasing costs by managing information of declining value appropriately. IT effectiveness and efficiency will be improved by using IT frameworks and standards, such as COBIT 2019 and ISO/IEC 38500:2008, the international standard that provides high-level principles and guidance for senior executives and directors, and those advising them, for the effective and efficient governance of IT.22 Implementing a master data management (MDM) program will help larger organizations with complex IT operations to ensure that they are working with consistent, accurate, and up-to-date data from a single source. Improved database security through data masking, database activity monitoring, database auditing, and other tools will help guard the organization's critical databases against the risk of rogue attacks by hackers. Deploying document life cycle security tools such as data loss prevention and information rights management will help secure your confidential information assets and keep them from prying eyes. This helps to secure the organization's competitive position and protect its valuable intellectual property.

By securing your electronic documents and data, not only within the organization but also for mobile use, and by monitoring and complying with applicable privacy laws, your confidential information assets will be safeguarded, your brand will be better protected, and your employees will be able to be productive without sacrificing the security of your information assets.

Moving Forward

We are not very good at figuring out what unstructured information costs. The Big Data deluge is upon us. If we hope to manage—and, more important, to monetize—this deluge, we must form cross-functional teams and challenge the way our organizations think about unstructured information. The first and most important step is developing the ability to convincingly calculate what unstructured information really costs and then to discover ways we can recoup those costs and drive value. These are foundational skills for information professionals in the new era of Big Data and infonomics. In this era, information is currency—but a currency that has value only when IG professionals drive innovation and management rigor in the unstructured information environment. Shaping up unstructured information by standardizing and inserting metadata (by using file analysis/content analysis tools) can help an organization harvest value from the majority of its information, which has largely been untapped.

Notes

- 1. “2017 CGOC Information Governance Process Maturity Model,” https://www.cgoc.com/updated-ig-process-maturity-model-reflects-todays-data-realities-2/ (accessed December 19, 2018).

- 2. Nick Ismail, “The Value of Data: Forecast to Grow 10-fold by 2025,” Information Age, April 5, 2017, https://www.information-age.com/data-forecast-grow-10-fold-2025-123465538/.

- 3. Richard B. Schmidt, “The Cyber Suit: How Computers Aided Lawyers in Diet-Pill Case,” Wall Street Journal, October 8, 1999, http://webreprints.djreprints.com/00000000000000000012559001.html.

- 4. Nick Bilton, “At Davos, Discussions of a Global Data Deluge,” New York Times, January 25, 2012, http://bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/01/25/at-davos-discussions-of-a-global-data-deluge/; Alex Pentland, quoted by Edge.org in “Reinventing Society in the Wake of Big Data,” August 30, 2012, www.edge.org/conversation/reinventing-society-in-the-wake-of-big-data; World Economic Forum, “Personal Data: The Emergence of a New Asset Class” (January 2011), http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_ITTC_PersonalDataNewAsset_Report_2011.pdf.

- 5. James Manyika et al., “Big Data: The Next Frontier for Innovation, Competitions, and Productivity,” McKinsey Global Institute (May 2011), https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/digital-mckinsey/our-insights/big-data-the-next-frontier-for-innovation.

- 6. Janna Quitney Anderson and Lee Ranie, “Future of the Internet: Big Data,” Pew Internet and American Life Project, July 20, 2012. www.pewinternet.org/2011/12/13/future-of-the-internet-role-of-the-web-and-new-media-in-the-public-sector/.

- 7. Louis Columbus, “Roundup of Big Data Forecasts and Market Estimates, 2012,” Forbes, August 16, 2012, https://www.forbes.com/sites/louiscolumbus/2012/08/16/roundup-of-big-data-forecasts-and-market-estimates-2012/#1c8022903cdf.

- 8. McKinsey Global Institute, “Big Data: The Next Frontier for Innovation, Competitions, and Productivity” (May 2011).

- 9. U.S. EPA, “Making Solid Waste Decisions with Full Cost Accounting,” n.d., https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyNET.exe/9100MNXP.TXT?ZyActionD=ZyDocument&Client=EPA&Index=1995+Thru+1999&Docs=&Query=&Time=&EndTime=&SearchMethod=1&TocRestrict=n&Toc=&TocEntry=&QField=&QFieldYear=&QFieldMonth=&QFieldDay=&IntQFieldOp=0&ExtQFieldOp=0&XmlQuery=&File=D%3A%5Czyfiles%5CIndex%20Data%5C95thru99%5CTxt%5C00000027%5C9100MNXP.txt&User=ANONYMOUS&Password=anonymous&SortMethod=h%7C-&MaximumDocuments=1&FuzzyDegree=0&ImageQuality=r75g8/r75g8/x150y150g16/i425&Display=hpfr&DefSeekPage=x&SearchBack=ZyActionL&Back=ZyActionS&BackDesc=Results%20page&MaximumPages=1&ZyEntry=1&SeekPage=x&ZyPURL (accessed December 19, 2018).

- 10. Nicholas M. Pace and Laura Zakaras, “Where the Money Goes: Understanding Litigant Expenditures for Producing Electronic Discovery,” RAND Institute for Civil Justice, 2012, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/monographs/2012/RAND_MG1208.pdf (accessed December 19, 2018).

- 11. Accounts Payable Network, “A Detailed Guide to Imaging and Workflow ROI,” 2010.

- 12. Various sources. See, for example: Barclay T. Blair, “Today's PowerPoint Slide: The Origins of Information Governance by the Numbers,” October 28, 2010, http://barclaytblair.com/origins-of-information-governance-powerpoint/.

- 13. Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corporation, “The History of Brooklyn Navy Yard,” http://www.brooklynnavyyard.org/history.html (accessed December 19, 2018).

- 14. Manyika et al., “Big Data.”

- 15. Barclay Blair and Barry Murphy, “Defining Information Governance: Theory or Action? Results of the 2011 Information Governance Survey,” eDiscovery Journal (September 2011). eDJ.com.

- 16. Jaikumar Vijayan, “Finding the Business Value in Big Data Is a Big Problem,” Computerworld, September 12, 2012, www.computerworld.com/s/article/9231224/Finding_the_business_value_in_big_data_is_a_big_problem.

- 17. Manyika et al., “Big Data.”

- 18. Economist Intelligence Unit, “Levelling the Playing Field: How Companies Use Data to Create Advantage” (January 2011), https://eiuperspectives.economist.com/technology-innovation/levelling-playing-field.

- 19. Genevieve Shaw Brown, “Mac Users May See Pricier Options on Orbitz,” ABC Good Morning America, June 25, 2012, http://abcnews.go.com/Travel/mac-users-higher-hotel-prices-orbitz/story?id=16650014#.UDlkVBqe7oV.

- 20. Manyika et al., “Big Data.”

- 21. Blair and Murphy, “Defining Information Governance.”

- 22. International Organization for Standardization, ISO/IEC 8500:2008, Corporate Governance of Information Technology, https://www.iso.org/standard/51639.html (accessed December 19, 2018).